Abstract

Background: Vitamin C has been demonstrated to kill BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells selectively. BRAF mutation is the most common genetic alteration in thyroid tumor development and progression; however, the antitumor efficacy of vitamin C in thyroid cancer remains to be explored.

Methods: The effect of vitamin C on thyroid cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis was assessed by the MTT assay and flow cytometry. Xenograft and transgenic mouse models were used to determine its in vivo antitumor activity of vitamin C. Molecular and biochemical methods were used to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of anticancer activity of vitamin C in thyroid cancer.

Results: Pharmaceutical concentration of vitamin C significantly inhibited thyroid cancer cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis regardless of BRAF mutation status. We demonstrated that the elevated level of Vitamin C in the plasma following a high dose of intraperitoneal injection dramatically inhibited the growth of xenograft tumors. Similar results were obtained in the transgenic mouse model. Mechanistically, vitamin C eradicated BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells through ROS-mediated decrease in the activity of EGF/EGFR-MAPK/ERK signaling and an increase in AKT ubiquitination and degradation. On the other hand, vitamin C exerted its antitumor activity in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells by inhibiting the activity of ATP-dependent MAPK/ERK signaling and inducing proteasome degradation of AKT via the ROS-dependent pathway.

Conclusions: Our data demonstrate that vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells by inhibiting MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways via a ROS-dependent mechanism and suggest that pharmaceutical concentration of vitamin C has potential clinical use in thyroid cancer therapy.

Keywords: Vitamin C, thyroid cancer, ROS, BRAF mutation, PI3K/AKT pathway

Introduction

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid or ascorbate), an essential nutrient for humans, has been debated for years because of its controversial role in cancer therapy. Several pioneering studies have demonstrated the efficacy of high-dose vitamin C in improving the survival of patients with advanced cancers 1-3. However, randomized controlled trials failed to replicate the above findings 4,5. It was later revealed that the route of vitamin C administration is important for the therapeutic effect of high-dose vitamin C 6. More recently, it has been shown that vitamin C at pharmacologic plasma concentrations acquired intravenously can selectively kill KRAS or BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells through targeting GAPDH 7. Furthermore, a recent study showed that vitamin C preferentially killed hepatocellular cancer stem cells via SVCT-2, but had little cytotoxic effect on normal cells 8. Importantly, a series of in vivo studies further supported the antitumor efficacy of high-dose vitamin C by parenteral administration 9,10.

BRAF mutations are frequent genetic alterations in human cancers particularly in melanoma, thyroid cancer, and colorectal cancer 11,12. In particular, BRAFV600E mutation accounts for about 90% of all oncogenic BRAF mutations and has been demonstrated to play a critical pathologic role in tumorigenesis 13. Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy, which is histologically classified into papillary thyroid cancer (PTC, 80-85%), follicular thyroid cancer (FTC, 10-15%), medullary thyroid cancer (MTC, 3-5%) and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC, <2%) 14. There is enough in vitro and in vivo evidence demonstrating that BRAFV600E mutation is a driving force for thyroid tumorigenesis and progression particularly in PTC, and has become the most important therapeutic target in thyroid cancer 15,16. We hypothesized that high-dose vitamin C supplement might be a safe and effective strategy for the treatment of thyroid cancer, and help improve the management and quality of life of thyroid cancer patients.

In this study, we demonstrated that vitamin C could effectively kill thyroid cancer cells regardless of BRAF mutation status through a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. Mechanistic studies revealed that vitamin C inhibits the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in BRAF wild-type or mutant thyroid cancer cells through distinct mechanisms via a ROS-dependent pathway, thereby suppressing the malignant progression of thyroid cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human thyroid cancer cell lines 8305C, BCPAP, 8505C, FTC133, and TPC-1 and human immortalized thyroid epithelial cells Hthy-ori3-1 were kindly provided by Dr. Haixia Guan (The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China). C643 was obtained from Dr. Lei Ye (Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, China). The cells were routinely cultured at 37°C in RPMI-1640 or DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). In some experiments, the medium was prepared by adding different amounts of D-Glucose (Gibco, Cat#: 15023-021) to RPMI-1640 medium without glucose (Gibco, Cat#: 11879-020) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Cell viability assay

Cells (3000 to 4000/well) were seeded in 96-well plates. After a 24-h culture, cells were treated with different doses of vitamin C (Sigma, Cat, # A4034) for the indicated times. The MTT assay was then carried out to assess the effect of vitamin C on cell viability, and IC50 values were calculated as described previously 17.

Colony formation assay

Cells (3000 to 4000/well) were seeded in 12-well plates and treated with different doses of vitamin C or vehicle control for 48 h, followed by culturing in RPMI-1640 or DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium with 10% FBS for 6-10 days. Colonies were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS and stained with crystal violet. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells were treated with 2 mM vitamin C or vehicle control for 2 h and then stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Apoptotic cells were measured by flow cytometry. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Cells (5 × 105/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. After culturing for 24 hrs, cells were washed with PBS and incubated in RPMI-1640 containing 2-6 mM glucose and 2 mM vitamin C for 2-4 h. Cells were then washed and re-suspended in serum-free medium containing10 μM of DCFH-DA and kept at 37°C for 60 min in the dark. Next, cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. In some experiments, 2 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Sigma, Cat#: A7250) was added to the medium to eliminate cellular ROS.

Animal studies

To establish a xenograft mouse model, 8305C (6 × 106) and C643 cells (4 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into right armpit region of 5- to 6-week-old female nude mice purchased from SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Mice were then randomly divided into three groups (five mice/group) when tumor volume grew to 50-80 mm3: vehicle control, vitamin C and vitamin C plus NAC. In brief, vitamin C (4 g per kg of body weight; twice a day) or vehicle control was administered by intraperitoneal injection at a total volume of 0.2 mL for 2-3 weeks. To determine the effect of vitamin C-induced ROS on tumor growth, 30 mM NAC was supplemented in drinking water after adjusting pH to 7.0 and freshly prepared every 4 days. Tumor sizes were measured with calipers every other day, and tumor volumes were calculated using the formula: (length × width2 × 0.5). All mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected and weighted 5 h after the final dose of vitamin C.

Transgenic mouse strains TPO-Cre and BrafCA were kindly provided by Drs. Kimura Shioko (National Institutes of Health, USA) and Martin McMahon (University of California, USA), respectively. BrafV600E-driven thyroid cancer of transgenic mice was produced by crossing BrafCA mice with TPO-Cre mice. Six-week-old TPO-Cre; BrafCA mice were randomly divided into three groups (six mice/group), and similarly treated for 30 days and tumors were measured as described above. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Xi'an Jiaotong University Health Science Center.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The IHC staining was carried out as described previously 18. Antibodies used in this study are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Protein expression was quantitated by integral optical density (IOD) using Image-pro plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, USA).

Western blot analysis

The indicated cells (4-5 × 105/well) were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured in RPMI 1640 with 6 mM glucose containing 10% FBS. Cells were then treated with different doses of vitamin C for the indicated times. Subsequently, cells were lysed, and lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. Antibodies used in this study are also presented in Supplementary Table S1. In some experiments, 2 mM NAC was used to eliminate cellular ROS.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) measurement

Relative ATP levels were measured using the ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) as described previously 19. In some experiments, 2 mM ATP (Sigma, Cat#: A6419) was supplemented to the medium to rescue vitamin C-mediated ATP reduction.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cells (3-5×105/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. The medium was then changed to FBS-free RPMI-1640 and cells were subjected to different treatments for 4 h. Subsequently, The EGF levels were measured using the Human EGF ELISA kit (NeoBioscience, ShenZhen, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay

To assess the effect of vitamin C on AKT protein stability, cells were incubated with 200 µg/mL CHX (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) for 2 h to inhibit de novo protein synthesis, and then treated with 2 mM vitamin C. At the indicated time points, cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Following pre-treatment with 25 μM MG132 (Selleck, Cat, S2619), cells were treated with 2 mM vitamin C for 2 h and were then lysed. The concentration of proteins was adjusted to equal incorporation before immunoprecipitation assays. Next, the lysates were incubated with antibodies against AKT or IgG at 4°C for 4-5 h followed by incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Immunoprecipitates were washed and further analyzed by Western blotting.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The protocols of RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR were described previously 18. The mRNA expression was normalized to 18S rRNA. The primer sequences are presented in Supplementary Table S2. Each sample was run in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test were used for comparing the data using SPSS statistical package (16.0, Chicago, IL). The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Vitamin C inhibits cell viability and induces cell apoptosis in thyroid cancer cells regardless of BRAF mutation status

GLUT1, as a major glucose transporter, has been demonstrated to play a key role in inhibiting the growth of KRAS/BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by increased uptake of the oxidized form of vitamin C, dehydroascorbate (DHA) (7). Therefore, we first investigated GLUT1 expression in a panel of thyroid cancer cell lines and an immortalized normal thyroid epithelial cell line Nthy-ori3-1 by Western blot analysis. The results showed that GLUT1 expression was much higher in the majority of thyroid cancer cell lines compared with Nthy-ori3-1 cells (Supplementary Figure S1). This observation was consistent with the previous studies showing that the enhanced glycolysis in thyroid cancer cells required an increased rate of glucose uptake 20,21.

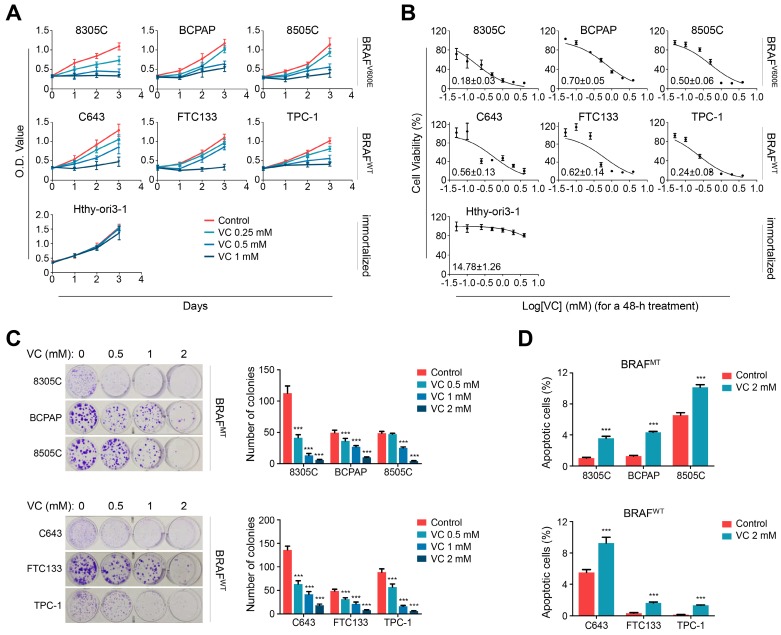

Next, we performed the MTT assay to determine the effect of vitamin C on cell viability in a panel of thyroid cell lines under physiological glucose concentration (6 mM). As shown in Figure 1A and B, vitamin C treatment significantly inhibited cell viability in both BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner but barely affected the viability of Hthy-ori3-1 cells. Consistent with a previous study (7), we found that thyroid cancer cells were more sensitive to vitamin C treatment in a low-glucose medium (2 mM) relative to a high-glucose medium (10 mM) (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). However, different glucose concentrations did not affect the viability of Hthy-ori3-1 cells (Supplementary Figure S2C).

Figure 1.

Vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells regardless of BRAF mutation status. (A) Different thyroid cancer cell lines and immortalized thyroid epithelial cell lines were treated with different doses of vitamin C (VC) for the indicated times, and the MTT assay was performed to evaluate the effect of VC on cell viability. (B) The above cells were treated with different doses of VC for 48 h. Cell viability was then similarly measured by MTT assay, and IC50 values were calculated using the Reed-Muench method. (C) Colony formation assay was used to validate the effect of VC on cell growth when thyroid cancer cells were treat with indicated doses of VC for 48 h. (D) Cell apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometry when the indicated cells were treated with 2 mM VC for 2 h. The data were presented as mean ± SD. ***, P <0.001.

The dose-dependent inhibitory effect of vitamin C treatment on thyroid cancer cells under physiological glucose concentration was also evident by colony-forming assay regardless of the BRAF mutation status (Figure 1C). Figure 1D shows that 2 mM vitamin C treatment induced significant apoptosis of both BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells under physiological glucose concentration. Notably, previous studies have shown that vitamin C concentrations higher than 2 mM are easily achieved in human plasma without significant toxicity 6,22,23, and, as our results have demonstrated here that 2 mM vitamin C was sufficient to kill thyroid cancer cells. Taken together, these observations indicated that vitamin C might be a safe and effective cytotoxic agent against thyroid cancer.

Vitamin C inhibits thyroid cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo through inducing cellular ROS production

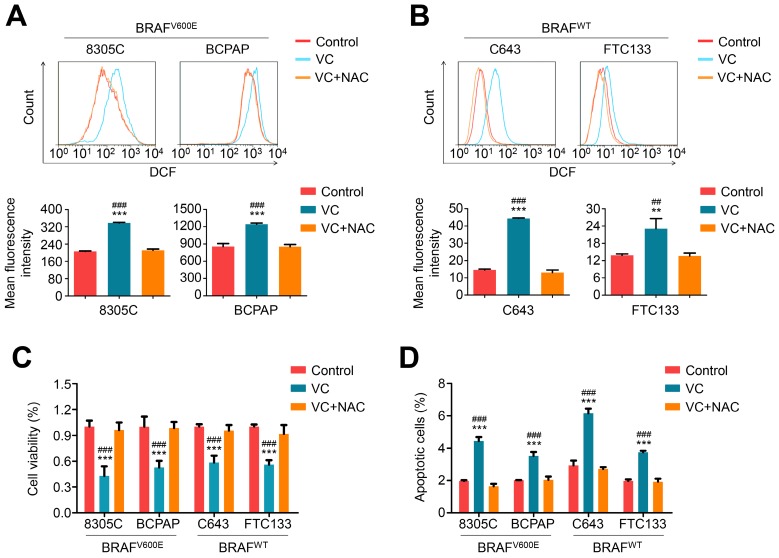

Considering that vitamin C treatment potently kills KRAS/BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing substantially elevated endogenous ROS 7, we measured cellular ROS levels in thyroid cancer cells treated with 2 mM vitamin C for 2-4 h by dichloro-fluorescein (DCF) staining. As expected, vitamin C treatment significantly increased cellular ROS levels in both BRAF mutant and wild-type cells, and this effect could be effectively reversed by 2 mM ROS scavenger NAC treatment (Figure 2 A and B). Also, vitamin C-induced cytotoxicity (including a decrease in cell viability and induction of cell apoptosis) could be completely reversed upon treatment with 2 mM NAC in both BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells (Figure 2 C and D).

Figure 2.

Vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells through inducing cellular ROS production. BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell lines 8305C and BCPAP (A) and BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cell lines C643 and FTC133 (B) were treated with 2 mM vitamin C (VC) alone or in combination with 2 mM NAC for 2-4 h, followed by a 1-h incubation with a ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye DCF-DA. The ROS-positive cells were then measured by flow cytometer (upper panels), and the mean fluorescence intensity of three independent experiments was calculated by Student's t test (lower panels). (C and D) The indicated cells were treated with 2 mM VC alone or in combination with 2 mM NAC for 48 h, and cell viability and apoptosis were then measured by MTT assay and flow cytometry, respectively. Data were presented as mean ± SD. **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001 for comparison with the control; ##, P <0.01; ###, P <0.001 for comparison with a combined treatment of VC and NAC

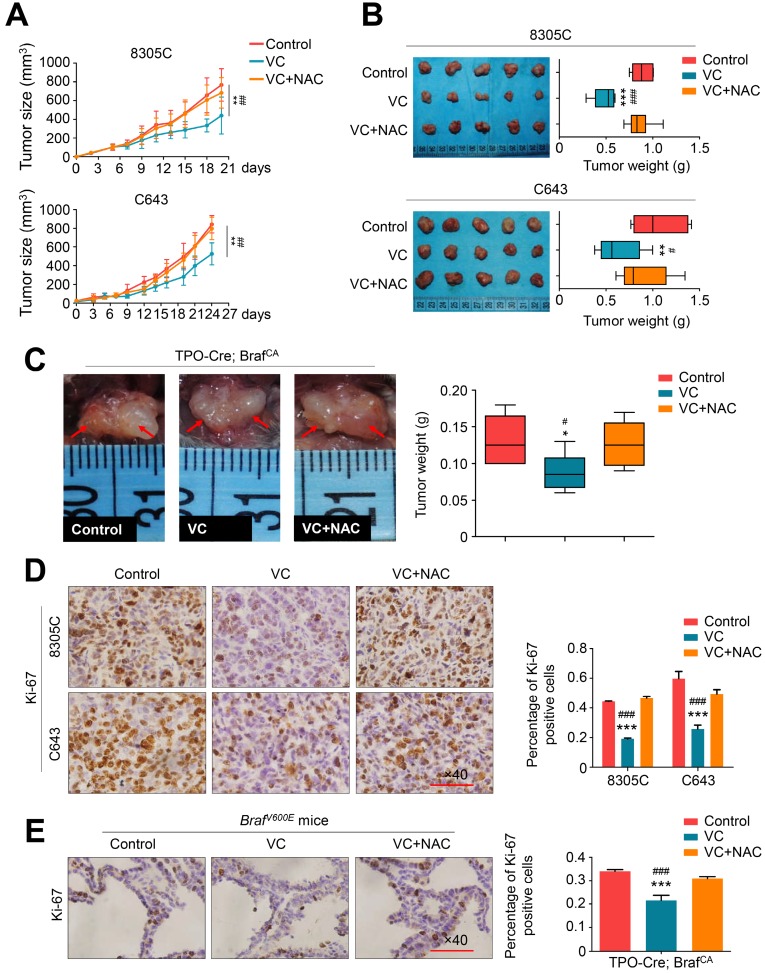

To determine in vivo antitumor activity of vitamin C, nude mice bearing xenograft tumors derived from BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell line 8305C and BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cell line C643 were treated with 4 g/kg vitamin C or PBS (control) twice a day for 2-3 weeks via intraperitoneal injection. This dosage has been proved to achieve pharmacological concentration recommended by a phase I clinical trial and two preclinical studies 23-25. As shown in Figure 3A, regardless of the BRAF mutation status, xenograft tumors progressively grew in the control group, while vitamin C treatment significantly reduced tumor growth. Also, NAC supplement in drinking water throughout vitamin C treatment could abolish the inhibitory effect of vitamin C on the growth of xenograft tumors (Figure 3B). We further tested the antitumor activity of vitamin C in a transgenic model of thyroid cancer driven by BRAFV600E mutation by crossing the BrafCA mice with TPO-Cre mice. The transgenic mice were treated daily with high-dose vitamin C (4 g/kg) or PBS for 30 days via intraperitoneal injection. As displayed in Figure 3C, vitamin C treatment caused a significant reduction in tumor volume and weight in comparison with the controls, while NAC supplement during treatment effectively reversed the antitumor effect of vitamin C (Figure 3C). We also assessed the effect of vitamin C on cell proliferation in tumor tissues from xenograft and transgenic mouse models by performing the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 staining. The results showed that the percentage of Ki-67 positive cells was remarkably decreased in the vitamin C-treated group compared to the control group while NAC treatment could reverse this effect (Figure 3D and E). Collectively, our results further supported the antitumor activity of vitamin C in thyroid cancer.

Figure 3.

Vitamin C inhibits tumor growth in xenograft and transgenic mouse models. (A) Xenografts derived from 8305C or C643 cells were treated with vitamin C (VC, 4 g/kg) twice a day or in combination with 30 mM NAC (in drinking water), and tumor growth was compared among control, VC- and VC+NAC-treated groups. Data were shown as mean ± SD (n =5/group). (B) Photographs of dissected tumors from the indicated groups. Box-whisker plot represents mean tumor weight in different groups. Data were shown as mean ± SD (n = 5/group). (C) TPO-Cre/LSL-Braf V600E mice was grouped and treated with as mentioned above. Representative photographs of thyroid tumors in different groups were shown in left panel. Right panel represents mean tumor weight. Data were shown as mean ± SD (n =6/group). Shown is representative Ki-67 staining in dissected tumors from xenograft (D) and transgenic mouse (E) models with the indicated treatments. Scale bars: 100 μm. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *, P <0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001 for comparison with the control; #, P <0.05; ###, P <0.001 for comparison with a combined treatment of VC and NAC.

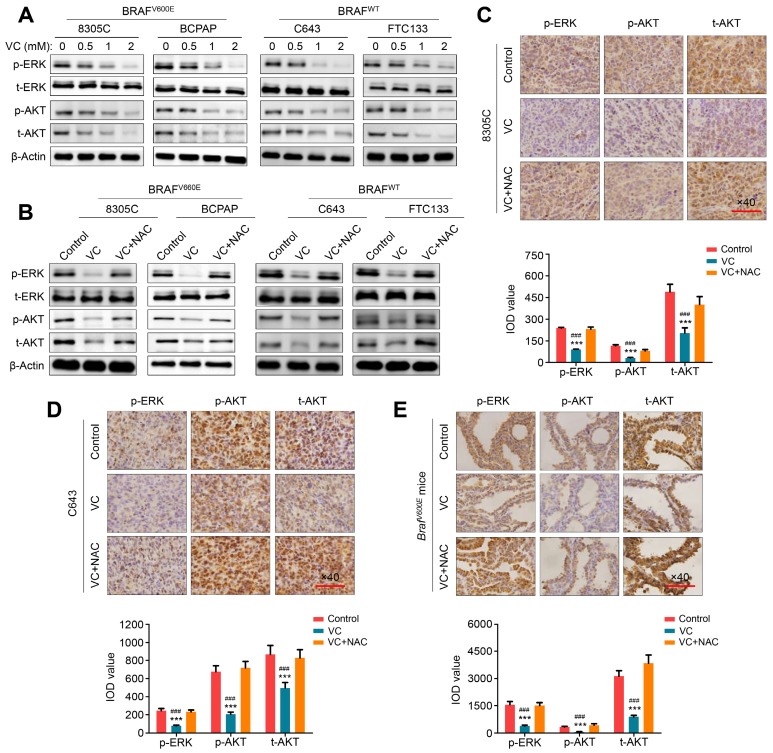

Vitamin C inhibits MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways in thyroid cancer cells in ROS-dependent-manner

MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways play a fundamental role in thyroid tumorigenesis and malignant progression and are major therapeutic targets in thyroid cancer 14. We, therefore, attempted to explore the effect of vitamin C on the activities of these two pathways in thyroid cancer cells. As shown in Figure 4A, regardless of the BRAF mutation status, vitamin C treatment markedly inhibited the activity of MAPK/ERK signaling in thyroid cancer cells characterized by decreased phosphorylation of ERK in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, we found that vitamin C treatment decreased the levels of phosphorylated AKT and total AKT in thyroid cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner, thereby inhibiting the activity of PI3K/AKT signaling (Figure 4A). The inhibitory effect of vitamin C on these pathways could be reversed by NAC treatment (Figure 4B). These findings were further validated by IHC staining in tumor tissues from xenograft and transgenic mouse models (Figure 4C-E). Thus, our data indicated that vitamin C could block MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways in a ROS-dependent fashion.

Figure 4.

ROS-dependent inhibition of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways by vitamin C in thyroid cancer cells. (A) The indicated cells were treated with vehicle control or different doses of vitamin C (VC) for 2-4 h, and cell lysates were then subjected to western blot analysis to determine the effect of VC on the levels of phosphor-ERK (p-ERK), total ERK (t-ERK), phosphor-AKT (p-AKT) and total AKT (t-AKT). (B) Western blot analysis of p-ERK, t-ERK, p-AKT and t-AKT in indicated cells treated with VC or in combination with NAC with β-Actin as a loading control. A comparison of the levels of p-ERK, p-AKT and t-AKT in nude mice (C and D) and transgenic mice (E) with the indicated treatments by IHC staining. Scale bars, 100 μm. The expression levels were calculated with IOD value (lower panels), and data were presented as mean ± SD. ***, P <0.001 for comparison with the control; ###, P <0.001 for comparison with a combined treatment of VC and NAC.

Vitamin C modulates the MAPK/ERK cascade via distinct mechanisms between BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells

Since vitamin C has been shown to selectively kill KRAS/BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH and inhibiting ATP production 7,8, we tested the effect of vitamin C on ATP levels in BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells As displayed in Figure 5A and B, 2 mM vitamin C treatment for 1-2 h significantly decreased ATP levels in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell lines 8305C and BCPAP but had almost no effect on ATP levels in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cell lines C643 and FTC133. Also, 2 mM NAC supplement in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells could completely restore ATP levels, indicating that vitamin C inhibited BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell growth probably by blocking ATP production via a ROS-dependent pathway. The results presented in Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure S3 show that vitamin C-mediated inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis were almost entirely reversed by NAC treatment, but only partially reversed by ATP supplement. However, ATP levels could be restored by adding NAC or ATP to the medium of 8305C and BCPAP cells (Supplementary Figure S4). These results indicated that vitamin C killed BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells only partially by depleting ATP. Considering that ATP is a frequent phosphate donor for different protein kinases 26, we hypothesized that vitamin C modulated the activity of MAPK/ERK signaling in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells by inhibiting ATP production. The results showed that restoring ATP levels in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells (Supplementary Figure S5) significantly attenuated the inhibitory effect of vitamin C on ERK phosphorylation but had almost no effect on AKT levels (Figure 5D). These results indicated that vitamin C regulated the activity of MAPK/ERK signaling in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells partially by inducing ATP depletion.

Figure 5.

Vitamin C ROS-dependently inhibits the activity of MAPK/ERK signaling via distinct mechanisms between BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells. ATP levels were determined in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell lines 8305C and BCPAP (A) and BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cell lines C643 and FTC133 (B) with indicated treatments. The levels of total proteins were used to normalize ATP concentration. (C) 8305C and BCPAP cells were treated with the indicated treatments, and the MTT assay was used to assess cell viability. (D) 8305C and BCPAP cells were treated with the indicated treatments, and western blot analysis was performed to determine the levels of t-AKT, p-ERK and t-ERK. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (E) C643 and FTC133 cells were treated with different doses of vitamin C (VC) for 4 h, and ELISA assay was then performed to measure EGF levels. (F) C643 and FTC133 cells were treated with 2 mM VC alone or in combination with 2 mM NAC, and ELISA assay was similarly performed to determine EGF levels. (G) Western blot analysis of phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK in C643 and FTC133 cells with the indicated treatments. (H) A schematic model of VC inhibiting the activity of MAPK/ERK pathway. Data were shown as mean ± SD. ***, P <0.001 for comparison with the control; ###, P <0.001 for comparison with a combined treatment of VC and NAC.

Thus, we have shown that vitamin C inhibits ERK phosphorylation in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells; however, the underlying molecular mechanism remains to be elucidated. EGF/EGFR signaling as an upstream effector of ERK phosphorylation has been demonstrated to exert a critical role in malignant progression of thyroid cancer 18, 27. There is also evidence indicating that ROS can diminish the release EGF in pancreatic cancer cells 28. Thus, we hypothesized that vitamin C inhibits ERK phosphorylation in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells by inducing ROS production and decreasing EGF release. Indeed, we found that vitamin C significantly reduced the release of EGF in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5E), and NAC treatment effectively reversed this effect in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cell lines C643 and FTC133 (Figure 5F). We also observed that vitamin C markedly decreased EGFR phosphorylation which could be reversed by NAC treatment in these two cell lines (Figure 5G). As predicted, phosphorylated ERK as a downstream effector of EGF/EGFR signaling was inhibited upon vitamin C treatment and could be restored by NAC treatment in these two cell lines (Figure 5G). These findings indicated that vitamin C blocked MAPK/ERK signaling in a ROS-dependent fashion via distinct mechanisms in BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells (Figure 5H).

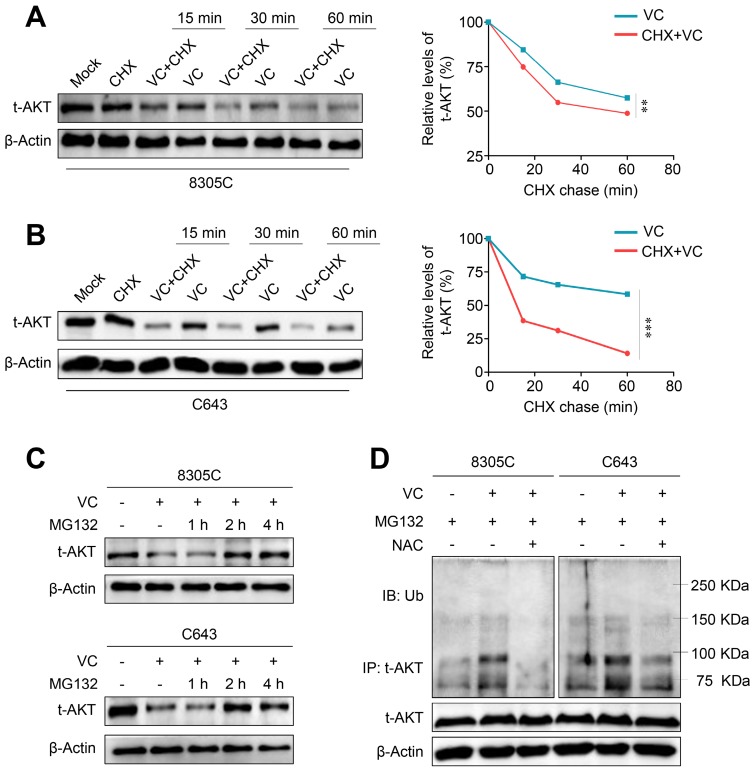

Vitamin C promotes AKT ubiquitination and degradation in thyroid cancer cells by a ROS-dependent pathway

Our data demonstrated the potential regulatory effect of vitamin C on gene transcription and/or protein stability of AKT thereby decreasing AKT protein levels. First, we determined the effect of vitamin C on mRNA expression of three AKT isoforms (AKT1-3) in 8305C and C643 cells by qRT-PCR. The results showed that vitamin C did not affect the transcription of AKT1 but upregulated mRNA expression of AKT2 and 3 in these two cell lines (Supplementary Figure S6) indicating that vitamin C modulated AKT expression at a posttranscriptional level. Next, we treated 8305C and C643 cells with cycloheximide (CHX) to block new protein synthesis to determine the effect of vitamin C on the protein stability of AKT. As shown in Figure 6A and B, the pretreatment of 8305C and C643 cells with CHX significantly increased vitamin C-mediated protein instabilityof AKT compared with the control cells. Thus, we hypothesized that vitamin C-mediated AKT instability might probably be attributed to the ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent degradation pathway. To confirm this, we treated 8305C and C643 cells with 25 μM proteasome inhibitor MG132 for the indicated time points and found that MG132 effectively restored vitamin C-mediated AKT reduction in the AKT level after a 2- or 4-h treatment (Figure 6C). This indicates that vitamin C promotes AKT proteolysis by the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway.

Figure 6.

Induction of AKT ubiquitination and proteasome degradation by vitamin C via a ROS-dependent pathway. Western blot analysis of total AKT in 8305C (A) and C643 (B) cells with vitamin C (VC) and cycloheximide (CHX) treatment alone or in combination for the indicated time points with β-Actin as a loading control. (C) 8305C and C643 cells was treated with 2 mM VC for 2 h after pretreatment of 25 μM MG132 for the indicated time points, and western blot analysis was then used to evaluate AKT expression. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) 8305C and C643 cells was pretreated with 25 μM MG132 for 2 h, and VC was then added for another 2 h before harvesting. Lysates were incubated with anti-AKT antibody for 4 h and then conjugated with agarose. Bounding proteins were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody. Input samples were taken prior to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Data were presented as mean ± SD. **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001.

AKT, as an important survival kinase, can be destroyed by the ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation pathway 29. Thus, we performed Co-IP and Western blotting to examine the effect of vitamin C on AKT ubiquitination in 8305C and C643 cells. The results showed that AKT ubiquitination was elevated upon vitamin C treatment which could be reversed by NAC treatment when these cells were pretreated with 25 μM MG132 (Figure 6D). Also, mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (MUL1) has been shown to be a negative regulator of AKT ubiquitination 30, and another study reported that cellular ROS could increase MUL1 expression 31. We, therefore, speculated that vitamin C upregulates MUL1 expression to promote AKT ubiquitination and degradation via a ROS-dependent pathway. Our data showed that vitamin C significantly increased mRNA expression of MUL1, and this effect could be reversed by NAC treatment in 8305C and C643 cells (Supplementary Figure S7). Collectively, the present study, for the first time, demonstrated that vitamin C could induce ROS-mediated AKT degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Based on the above data, we propose a simple model to illustrate the antitumor efficacy of vitamin C in thyroid cancer cells (Supplementary Figure S8). In brief, cellular uptake of the oxidized form of vitamin C, DHA, via GLUT1 can increase cellular ROS production. By targeting GAPDH, the elevated ROS level results in ATP depletion and inhibits ERK phosphorylation in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells. In BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells, increased ROS inhibits EGF/EGFR-MAPK/ERK signaling by impeding EGF release. Furthermore, increased ROS levels can induce AKT ubiquitination and degradation in both BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells probably through regulating MUL1 expression via a ROS-dependent pathway. Thus, vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells through ROS-dependent blocking of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways.

Discussion

Antitumor efficacy of vitamin C has long been argued since it was first demonstrated that intravenous administration of vitamin C (10 g/day) could effectively prolong the survival of cancer patients 2,3. In this context, a remarkable finding was reported in a recent study that vitamin C could selectively kill KRAS/BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH 7. DHA, the oxidized form of vitamin C, could be taken up by GLUT1 and reduced to vitamin C by using glutathione (GSH) and leading to ROS accumulation. Increased ROS resulted in the loss of GAPDH activity and subsequent ATP depletion by targeting cysteine (C152) in its active site. Given that cancer cells with KRAS/BRAF mutations are greatly dependent on glycolysis for survival and growth, ATP depletion causes an energy crisis in these cells 7. These findings inspired other studies that provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of pharmacologic effects of vitamin C in treating different types of cancers 32. It is well known that BRAF mutation is the most common genetic alteration in thyroid cancer 11,33. Also, it has been shown that thyroid cancer cells can take up vitamin C via a GLUT1-dependent pathway 34 suggesting a potential antitumor activity of vitamin C in thyroid cancer.

In this study, we found that vitamin C could kill thyroid cancer cells in vitro regardless of the BRAF mutation status and vitamin C-induced ROS production was required for this effect. More importantly, in vivo data also demonstrated that vitamin C inhibited tumor growth in the xenograft and transgenic mouse models via a ROS-dependent pathway. Given the central role of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in thyroid tumorigenesis and malignant progression 14, we investigated the effect of vitamin C on these two pathways to elucidate its antitumor mechanisms. The results demonstrated that vitamin C markedly blocked the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways through ROS-dependent decrease in ERK phosphorylation and AKT levels regardless of the BRAF mutation status. Furthermore, we provided evidence for the distinct roles of vitamin C in regulating the activity of MAPK/ERK signaling between BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells. Vitamin C suppressed ATP production in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells via a ROS dependent pathway while virtually did not influence ATP levels in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells. This was consistent with the previous studies that KRAS/BRAF mutant cancer cells excessively relied on glycolysis for energy supply 35,36. Moreover, we found that ATP supplement could significantly reverse the inhibitory effect of vitamin C on ERK phosphorylation but barely affected AKT levels. Taken together, our data showed that vitamin C-mediated depletion of the phosphate donor ATP in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells contributed to the inhibition of MAPK/ERK signaling.

In BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells, our results showed that vitamin C inhibited ERK phosphorylation via an ATP-independent pathway; however, the exact mechanism is unclear. It has been previously reported that ROS can decrease the release of the EGFR ligand, EGF, thereby inhibiting its downstream signaling pathways including MAPK/ERK signaling 28. It is possible that a similar mechanism exists in thyroid cancer. Our data showed that upon vitamin C treatment of BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells, the release of EGF was inhibited in a ROS-dependent fashion. Consequently, EGFR phosphorylation and the levels of its downstream effector phosphorylated ERK were markedly inhibited in these cells via a ROS-dependent pathway. Collectively, our data indicate that vitamin C blocks the MAPK/ERK signaling through a ROS-dependent pathway by distinct mechanisms between BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells.

Besides the MAPK/ERK pathway, the critical role of PI3K/AKT pathway has also been demonstrated in thyroid cancer development and progression both in vitro and in vivo 37,38. In the present study, we observed that vitamin C treatment could significantly decrease AKT levels in both BRAF mutant and wild-type thyroid cancer cells resulting in ROS-dependent inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling. Further studies demonstrated that vitamin C treatment did not significantly affect the mRNA expression of three AKT isoforms but promoted proteasome degradation of AKT proteins via a ROS-dependent pathway. It has been previously reported that ROS could upregulate MUL1 and induce AKT ubiquitination and proteasome degradation in different types of cancers 30,31. MUL1 was first identified as a ubiquitin E3 ligase with a C-terminal RING finger motif and was shown to exert a key role in regulating mitochondrial dynamics 39. Our data strongly supported that MUL1 expression was significantly elevated upon vitamin C treatment in a ROS-dependent manner.

Pharmacokinetic studies have indicated that 4 g of intravenous administration of vitamin C can achieve a plasma concentration of nearly 2 mM 6, which is sufficient to kill thyroid cancer cells as evidenced by our in vitro studies. However, in vitro conditions are unable to sufficiently mimic the in vivo environment with hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and other metabolic changes. Importantly, the present study also demonstrated that high-dose vitamin C (4 g/kg) significantly inhibited tumor growth in xenograft and transgenic mouse models, indicating that vitamin C can be used as a potential adjuvant therapy for thyroid cancer. Several clinical trials have shown that intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C can improve the quality of life and prolong overall survival in patients with advanced cancers 40. Thus, additional clinical trials will be needed to evaluate the clinical use of vitamin C in thyroid cancer therapy and determine its safety and efficacy.

Conclusion

In summary, through a series of in vitro and in vivo studies, we demonstrated ROS-dependent killing of thyroid cancer cells by vitamin C through multiple molecular mechanisms. Vitamin C could induce a ROS-dependent decrease in ATP leading to the inhibition of MAPK/ERK signaling in BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cells. However, in BRAF wild-type thyroid cancer cells, vitamin C inhibits the MAPK/ERK pathway by ROS-dependent blocking of its upstream regulator EGF/EGFR signaling. Also, vitamin C inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway in a ROS-dependent fashion promoting proteasome degradation of AKT in thyroid cancer cells regardless of the BRAF mutation status. Overall, we believe that vitamin C is a safe and effective antitumor agent against thyroid cancer. The cytotoxicity induced by vitamin C in thyroid cancer cells and the underlying molecular mechanisms elucidated in our study provide a rationale for exploring the therapeutic use of vitamin C for thyroid cancer, particularly in combination with other conventional or targeted therapies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Haixia Guan (The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China) and Lei Ye (Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, China) for kindly providing human thyroid cancer cell lines. We also would like to thank Dr. Kimura Shioko (National Institutes of Health, USA) and Prof. Martin McMahon (University of California, USA) for kindly providing transgenic mouse strains TPO-Cre and BrafCA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81572627 and 81770787 to PH; No. 81672645 to MJ), and Innovation Talent Promotion Plan in Shaanxi Province (No. 2018TD-006 to PH).

Authors' contributions

XS, ZS, QY, FS and JP performed all the experimental work. JM and SM participated in data analysis. PH and MJ conceived and participated in the design of the study. The manuscript was written by XS and PH. DY offered assistance for this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- DHA

dehydroascorba11te

- NAC

N-acetyl-cysteine

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

References

- 1.Cameron E, Campbell A. The orthomolecular treatment of cancer. II. Clinical trial of high-dose ascorbic acid supplements in advanced human cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 1974;9:285–315. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(74)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:4538–4542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3685–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creagan ET, Moertel CG, O'Fallon JR, Schutt AJ, O'Connell MJ, Rubin J. et al. Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:687–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197909273011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O'Connell MJ, Ames MM. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:137–141. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A. et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:533–537. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun J, Mullarky E, Lu C, Bosch KN, Kavalier A, Rivera K. et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science. 2015;350:1391–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lv H, Wang C, Fang T, Li T, Lv G, Han Q. et al. Vitamin C preferentially kills cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma via SVCT-2. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1. doi: 10.1038/s41698-017-0044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verrax J, Calderon PB. Pharmacologic concentrations of ascorbate are achieved by parenteral administration and exhibit antitumoral effects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du JA, Martin SM, Levine M, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Wang SH. et al. Mechanisms of Ascorbate-Induced Cytotoxicity in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:509–520. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S. et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnett MJ, Marais R. Guilty as charged: B-RAF is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, Lee S, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Good VM. et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116:855–867. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:184–199. doi: 10.1038/nrc3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xing M. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:245–262. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitsiades CS, Negri J, McMullan C, McMillin DW, Sozopoulos E, Fanourakis G. et al. Targeting BRAFV600E in thyroid carcinoma: therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1070–1078. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Tian Z, Yang Q, Li H, Guan H, Shi B. et al. Sulforaphane inhibits thyroid cancer cell growth and invasiveness through the reactive oxygen species-dependent pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25917–25931. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang YF, Sui F, Ma JJ, Ren XJ, Guan HX, Yang Q. et al. Positive Feedback Loops Between NrCAM and Major Signaling Pathways Contribute to Thyroid Tumorigenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:613–624. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Bai H, Zhang X, Liu J, Cao P, Liao N. et al. Inhibitory effect of oleanolic acid on hepatocellular carcinoma via ERK-p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1323–1330. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bensinger SJ, Christofk HR. New aspects of the Warburg effect in cancer cell biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jozwiak P, Krzeslak A, Pomorski L, Lipinska A. Expression of hypoxia-related glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 in benign, malignant and non-neoplastic thyroid lesions. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:601–606. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson CM, Levin RD, Spector T, Lis CG. Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of high-dose intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:139–146. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2179-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffer LJ, Levine M, Assouline S, Melnychuk D, Padayatty SJ, Rosadiuk K. et al. Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1969–1974. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Pooput C, Kirk KL, Krishna MC. et al. Pharmacologic doses of ascorbate act as a prooxidant and decrease growth of aggressive tumor xenografts in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11105–11109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804226105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espey MG, Chen P, Chalmers B, Drisko J, Sun AY, Levine M. et al. Pharmacologic ascorbate synergizes with gemcitabine in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1610–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaman GJR, Garritsen A, de Boer T, van Boeckel CAA. Fluorescence assays for high-throughput screening of protein kinases. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:313–320. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsiades CS, Kotoula V, Poulaki V, Sozopoulos E, Negri J, Charalambous E. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in human thyroid carcinoma: mutational and functional analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3662–3666. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chio IIC, Jafarnejad SM, Ponz-Sarvise M, Park Y, Rivera K, Palm W. et al. NRF2 Promotes Tumor Maintenance by Modulating mRNA Translation in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:963–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin D, Salinas M, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Cuadrado A. Ceramide and reactive oxygen species generated by H2O2 induce caspase-3-independent degradation of Akt/protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42943–42952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae SH, Kim SY, Jung JH, Yoon YM, Cha HJ, Lee HJ. et al. Akt is negatively regulated by the MULAN E3 ligase. Cell Res. 2012;22:873–885. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY, Kim HJ, Kang SU, Kim YE, Park JK, Shin YS. et al. Non-thermal plasma induces AKT degradation through turn-on the MUL1 E3 ligase in head and neck cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:33382–33396. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaiser J. ONCOLOGY Vitamin C could target some common cancers. Science. 2015;350:619–619. doi: 10.1126/science.350.6261.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159:676–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jozwiak P, Krzeslak A, Wieczorek M, Lipinska A. Effect of Glucose on GLUT1-Dependent Intracellular Ascorbate Accumulation and Viability of Thyroid Cancer Cells. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:1333–1341. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.1078823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, Pagliarini R, Angenendt P, Rajagopalan H. et al. Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science. 2009;325:1555–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.1174229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg SE, Chandel NS. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:9–15. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xing MZ. Genetic Alterations in the Phosphatidylinositol-3 Kinase/Akt Pathway in Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2010;20:697–706. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou P, Liu DX, Shan Y, Hu SY, Studeman K, Condouris S. et al. Genetic alterations and their relationship in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in thyroid cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1161–1170. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A. et al. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Q, Polireddy K, Chen P, Dong R. The unpaved journey of vitamin C in cancer treatment. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;93:1055–1063. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.