Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a biological gasotransmitter that has been employed for the treatment of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Despite its therapeutic value, the implementation of this gaseous molecule for this purpose has required H2S-releasing prodrugs for effective intracellular delivery. The majority of these prodrugs, however, spontaneously release H2S via uncontrolled hydrolysis. Here, we describe a Ru(II) based H2S-releasing agent that can be activated selectively by red light irradiation. This compound operates in living cells, increasing intracellular H2S concentration only upon irradiation with red light. Furthermore, the red light irradiation of this compound protects H9c2 cardiomyoblasts from an in vitro model of ischemia-reperfusion injury. These results validate the use of red light-activated H2S-releasing agents as valuable tools for studying the biology and therapeutic utility of this gasotransmitter.

The biological role of the toxic gas hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as a neuromodulator was first recognized in 1996.1 Since this initial discovery, H2S has received significant attention because of its therapeutic potential for treating inflammation,2 Parkinson’s disease,3 reproductive dysfunction,4 brain injury,5–9 diabetes,10 cancer,11 and ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury.12,13 The therapeutic implementation of H2S in its gaseous state, however, is challenged by difficulties in administering biologically relevant and beneficial concentrations while avoiding problems associated with its known cytotoxicity, volatility, and flammability.14–16 To circumvent this challenge, researchers have developed synthetic donors that release H2S in response to stimuli such as pH,17 external ight,18–25 reactive oxygen species,26 and enzymatic activity,26–32 Among these strategies, light-activated H2S release has been recognized as a promising tool for biomedical and therapeutic applications.18,21 Light-activated prodrugs are exciting therapeutic candidates that allow for localized and noninvasive treatment of serious medical conditions, while circumven-ting toxic side effects that arise from traditional chemotherapy.33–37

The majority of light-activated H2S-releasing agents require UV light, which ineffectively penetrates biological tissue and can give rise to toxic effects.38 Efforts to move photoactivation wavelengths to more biologically useful regions of the visible spectrum have resulted in several systems that can be triggered with visible and near-infrared light.21–23 Except in one case,22these systems require upconverting nanoparticles to mediate the low-energy photoactivation process.21–23 Because red light effectively penetrates biological tissue and is nontoxic, the development ofsmall-molecule red light-activated H2S-releasing agents would be particularly valuable for both studying the biological roles of H2S and leveraging the therapeutic effects of this gasotransmitter.39 In this report, we describe the first prototype of this class of molecules and its implementation to protect against in vitro ischemia-reperfusion injury.

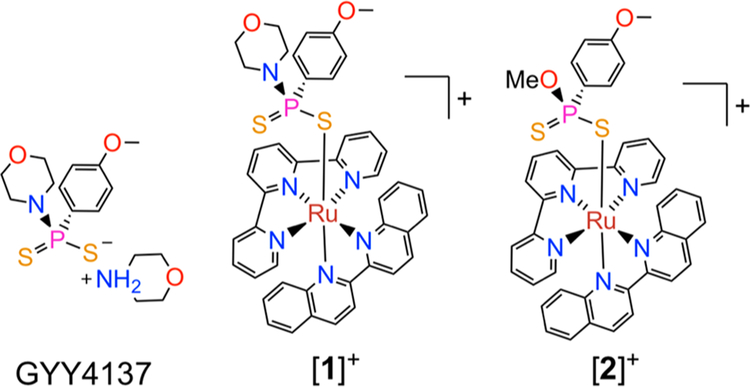

Our strategy to develop such a red light-activated H2S-releasing molecule invoked a combination of the established H2S-releasing compound morpholin-4-ium 4-methoxyphenyl-(morpholino)phosphinodithioate (GYY4137, Chart 1)40,41 and a photolabile ruthenium(II) scaffold [Ru(tpy)(biq)(L)]n+ (tpy = 2,2’:6’−2”-terpyridine; biq = 2,2’-biquinoline, n = 1, 2). Ru(II) compounds of this class possess low energy metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) absorption bands that extend into the red region of the visible spectrum. After population of the 1MLCT state by absorption of red light, efficient intersystem crossing to a dissociative triplet ligand field (3LF) state ejects the monodentate ligand L with high quantum yields.42–45

Chart 1.

GYY4137, and the Compounds [1]+ and [2]+ That Were Explored in This Study

In aqueous or wet organic solvent, GYY4137 releases H2S over a few hours.46 Sustained H2S release from GYY4137 has been used therapeutically to treat inflammation,47 inhibit cancer cell growth,48 and prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury.49,50 The hydrolysis of GYY4137, however, occurs spontaneously in solution, limiting spatiotemporal control of H2S release from this molecule. We hypothesized that coordination of GYY4137 to the photoactive [Ru(tpy)(biq)(L)]n+ scaffold would inhibit its spontaneous hydrolysis until it was released by irradiation with red light. Thus, the complex [Ru(tpy)(biq)(GYY4137)]Cl ([l]Cl) (Chart 1) was developed as the first red light-activated H2S-releasing molecule.

The direct reaction between [Ru(tpy)(biq)Cl]Cl and excess GYY4137 in 50% aqueous acetone gave [l]Cl as the major product in solution. Further purification by silica gel chromatography (90/10 CH3CN/H2O) afforded pure [l]Cl in 24% yield. When [Ru(tpy)(biq)Cl]PF6 was sequentially treated with AgPF6, which removed the inner-sphere chloride as insoluble AgCl, and excess GYY4137 in refluxing methanol, we unexpectedly isolated [Ru(tpy)(biq)(GYYOMe)]Cl ([2]Cl), where GYYOMe is O-methoxy 4-methoxyphenylphosphinodithioate. Over the course of this reaction, the morpholine group of GYY4137 was replaced by the methanol solvent giving rise to the GYYOMe ligand (Chart 1).51

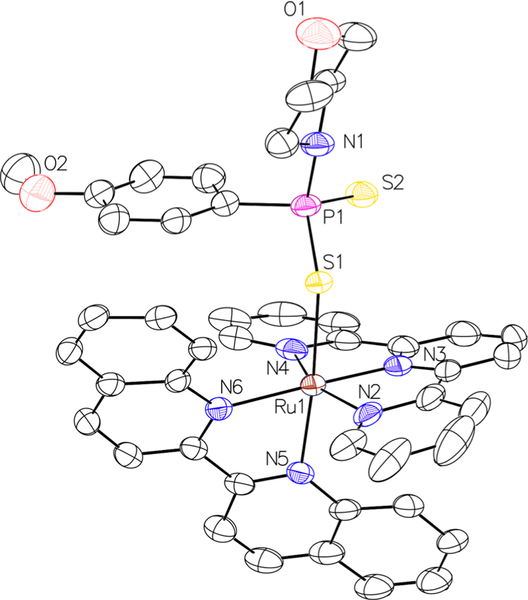

In addition to characterization by standard techniques, such as NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and IR spectroscopy (Figures S1–S12, Supporting Information, SI), [l]PF6 was also characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structure of [l]PF6. Hydrogen atoms and the PF6− counterion are omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level.

Crystallographic parameters and relevant interatomic distances and angles are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the SI. The Ru(II) center of [l]PF6 attains a distorted octahedral geometry with GYY4137 coordinated trans to the biquinoline ligand. The sterically demanding tpy and biq ligands perturb the Ru-ligand bond angles, which range from 77.31° to 99.23°, significantly from the 90° of an ideal octahedron. This steric strain contributes to the efficient photosubstitution reactions of these complexes by lowering the energy of the dissociative 3LF state, allowing for it to be thermally populated from the photogenerated 3MLCT state.52–55 The Ru-S1 distance (2.41 Å) is similar to that found in a related organometallic Ru(II) complex bearing GYY4137 as a ligand (2.403 Å).56

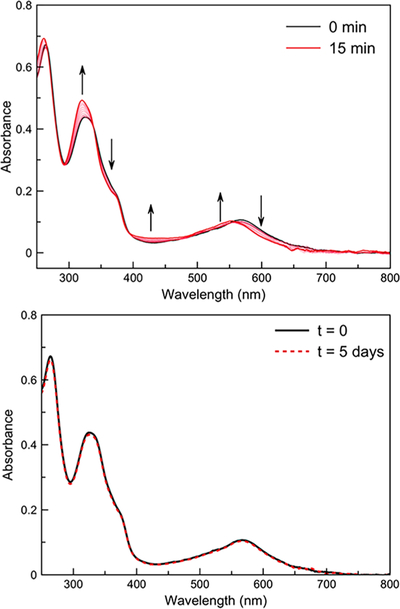

The photophysical properties of [l]Cl and [2]Cl in buffered aqueous solution (3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid; MOPS; pH 7.4) were investigated (Table 1). The complexes exhibit1MLCT absorption bands at λ = 581 nm ([l]Cl) andλ = 568 nm ([2]Cl), which both tail past 650 nm. Upon irradiation of the complexes with 626 nm light (Figures S13 and S14, SI), the UV-vis spectra evolve, resulting in a blue shift of the 1MLCT band to a new maximum at 549 nm, characteristic of the expected photoproduct [Ru(tpy)(biq)(OH2)]2 + (Figures 2 and S15, SI).44,45 The photosubstitution quantum yields (Φ626) at room temperature for [l]Cl and [2]Cl were found to be similar to those measured for related Ru(II) complexes (Table 1)42,44,45

Table 1.

Absorption Maxima (λmax), Molar Extinction Coefficients (ε) at λmax, and Photosubstitution Quantum Yields (Φ626) of [l]Cl and [2]Cl

| Compound | λmax (nm) | ε (M−1 cm−1) | Φ626 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1]Cl | 581 | 4050 ± 140 | 0.85 ± 0.03 |

| [2]C1 | 570 | 4000 ± 200 | 1.02 ± 0.11 |

Figure 2.

Top: Changes in the electronic absorption spectrum of [l]Cl in 100 mM MOPS (pH 7.4) under 626 nm light irradiation (photon flux = 2.01 × 10−8 mol s−1, tirr =15 min, T = 298 K). Bottom: Electronic absorption spectrum of [ 1 ]Cl in 100 mM MOPS in the dark after 5 days (T = 298 K).

The red light-induced photoreaction of [l]Cl was further investigated by1H and31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy in 90/10 D2O/DMSO-d6. Upon irradiation, the characteristic doublet of [l]Cl in the 1H NMR spectrum at 9.97 ppm, which is assigned to the proton in the ortho position of the biq ligand directly adjacent to the coordinated GYY4137, vanished while a new quartet at 8.94 ppm, assigned to [Ru(tpy)(biq)(OH2)]2+, grew in over time. Similarly, peaks originating from [l]Cl at 8.80 and 8.70 ppm were replaced with doublets corresponding to [Ru(tpy)(biq)(OH2)]2+ at 8.63 and 8.59 ppm, (Figure S16, SI). In the31P{1H} NMR spectrum, the singlet arising from the coordinated GYY4137 ligand of [l]Cl was replaced by a peak at 98.93 ppm, which is conclusively assigned to free GYY4137 (Figure S17, SI).

For these light-activated complexes to be valuable as stimuli responsive agents, they must not undergo thermal loss of the phosphinodithioate ligand. As such, the thermal stabilities of these complexes were assessed in aqueous buffer. We found that [2]Cl is unstable in the dark, forming [Ru(tpy)(biq)(OH2)]2+and GYYOMe via a thermal aquation reaction (Figure S18, SI). In contrast, [l]Cl did not show appreciable changes in its absorption spectrum after 5 days in solution (Figure 2), indicating that this compound is sufficiently stable for use as a light-activated H2S-releasing agent. Notably, the GYY4137 ligand did not hydrolyze while coordinated to the Ru(II) center.

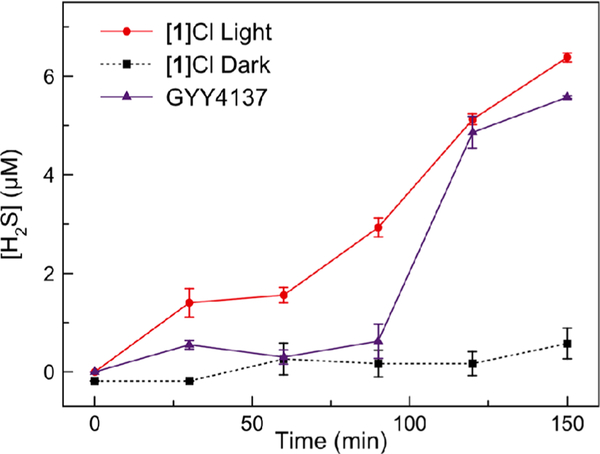

Given the promising thermal stability and efficient photo substitution quantum yield of [l]Cl, we further investigated its H2S-releasing properties. The formation of H2S in aqueous buffer was evaluated using the fluorescent probe 1,5-dansyl azide (DNS-az).57 The azide functional group of this probe is selectively reduced by H2S to elicit a linear, fluorescent turn-on response (Figure S19, SI). Using this probe, we observed negligible release of H2S from [l]Cl in the dark. By contrast, upon irradiation with 626 nm light, a steady time-dependent increase in H2S concentration was detected, comparable to that of free GYY4137 (Figure 3). By coordinating GYY4137 to the ruthenium photocage in complex [l]Cl, we gain temporal control over the otherwise continuous release of H2S from GYY4137.

Figure 3.

H2S release from [l]Cl (200 μM) with red light irradiation (red circles), [l]Cl (200 μM) in the dark (black squares), and GYY4137 (200 μM) (purple triangles) measured by DNS-az fluorescence. Errors bars are the standard error (SE) of three independent trials.

For [l]Cl to be useful as a H2S-releasing biological tool or therapeutic agent, it should not give rise to toxic effects. With short (4 h) incubation times, conditions that are favorable for H2S-releasing applications, [l]Cl is essentially nontoxic to healthy cells (Table S3, Figures S20 and S21, SI). At longer times, [l]Cl does show mild toxicity (Table S4, Figures S22 and S23, SI). The aquated photoproduct [Ru(tpy)(biq)(OH2)]2+ is effectively nontoxic, as indicated by its IC50 value of 97 ± 4 μM, consistent with values that have previously been measured for this compound. These results are significant because related Ru(II) compounds can bind to DNA and induce cytotoxicity.54

As expected, GYY4137 is noncytotoxic (Figures S22 and S23, SI).

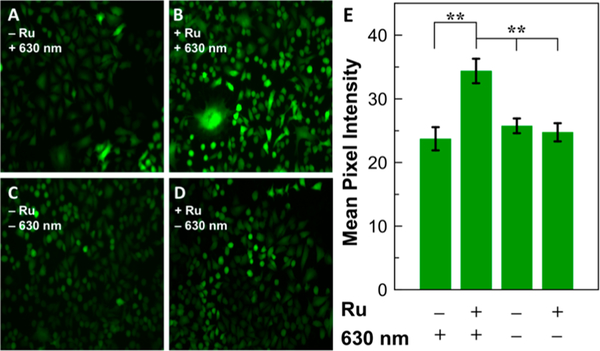

Given the promising toxicity profile of [l]Cl and its photoproducts, the H2S-releasing capabilities of this compound were measured in living cells using the cell-trappable H2S responsive fluorescent probe, SF7-AM.58 Lung cancer (A549) cells were loaded with SF7-AM and treated with the complexes, followed by irradiation with red light for 30 min prior to fluorescence microscopy imaging. Cells that were only treated with [ l ]Cl or exposed to red light showed no significant increase in fluorescence intensity of SF7-AM. In contrast, when both [l] Cl and red light were administered to cells, a significant increase in fluorescence intensity was observed, indicating that both components are critical for the intracellular release of H2S (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Images of H2S release from [l]Cl. A549 cells were incubated with 5 μM SF7-AM for 30 min, washed and then (A) exposed to red light for 30 min; (B) treated with 60 μM [ l]Cl and exposed to red light for 30 min; (C) incubated for 30 min in the dark; (D) treated with 60 μM [l]Cl for 30 min in the dark. (E) Mean pixel intensity of fluorescence images for A549 cells in the experiments described in panels A—D. Error bars are SE of n = 5 or 6 wells from two biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed student’s t test. **p < 0.005.

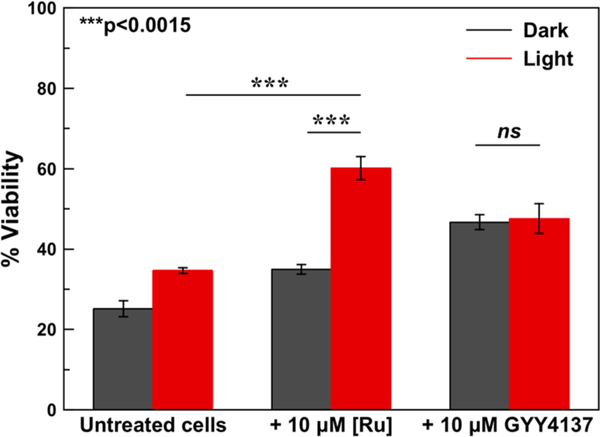

Because H2S can protect against I/R injury,59–65 we investigated the ability of [l]Cl to give rise to cytoprotective effects selectively upon red light irradiation in H9c2 cells subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Cells were incubated in a pH 6.4 ischemia mimetic buffer (see SI for details) in hypoxic conditions, followed by treatment with [l]Cl or GYY4137 in the dark or under red light irradiation for 30 min prior to reoxygenation. Control cells were incubated in normoxic conditions for the duration of the experiment.

The viability of untreated cells, measured by the colorimetric MTT assay,66 subjected to this I/R injury model was decreased by approximately 80%, indicating that this model accurately captures the cytotoxic effects of this condition. When cells were treated with [ l ]Cl in the dark, there was no significant change in cell viability compared to untreated cells. In the presence of red light, however, cells treated with [l]Cl show a 75% increase in viability relative to the untreated control cells. In comparison, the extent of the cytoprotective effect of GYY4137 does not change appreciably when cells are treated either in the light or dark (Figure 5). These results demonstrate that [l]Cl can effectively cage GYY4137 and prevent H2S release until selective red light activation to prevent cell death in a model of I/R injury.

Figure 5.

Protective effects of [l]Cl and GYY4137 (10 μM) in cells subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Error bars are SE of three replicates with n = 6 wells. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed student’s t test. ***p < 0.0015.

In summary, we have developed a novel red light-activated H2S-donating complex. Compared to other light-activated H2S- releasing systems, this compound is the first small molecule that is capable of releasing H2S upon irradiation with red light without the need for a secondary nanoparticle system. We have shown that [l]Cl is stable in the dark and can be activated to release H2S in biological conditions. In addition, [l]Cl is capable of preventing cell death in a model of I/R injury. This work demonstrates the relatively understudied cytoprotective properties of transition metal compounds, and suggests a broader utility for these complexes as innovative drugs for the treatment and prevention of serious medical conditions.

Supplementary Material

■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Cornell University and the National Science Foundation (NSF-GRFP for J.J.W.; award no. DGE 1650441). This work made use of the NMR facility at Cornell University which is funded, in part, bythe NSF (award no. CHE 1531632). This work was additionally supported by the NIH (award no. NIGMS R15GM114792 to A.R.L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b08695.

Complex characterization data, cell viability curves, crystal data tables, UV-vis spectra, NMR data of irradiation (PDF)

Data for[l]PF6 (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

■ REFERENCES

- (1).Abe K; Kimura HJ Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Li M; Li J; Zhang T; Zhao Q; Cheng J; Liu B; Wang Z; Zhao L; Wang C Eur. J. Med. Chem 2017, 138, 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cao X; Cao L; Ding L; Bian J Mol. Neurobiol 2018, 55,3789–3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wang J; Wang W; Li S; Han Y; Zhang P; Meng G; Xiao Y; Xie L; Wang X; Sha J; Chen Q; Moore PK; Wang R; Xiang W; Ji Y Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2018, 28, 1447–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Eto K; Asada T; Arima K; Makifuchi T; Kimura H Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2002, 293, 1485–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Qiao P; Zhao F; Liu M; Gao D; Zhang H; Yan Y Mol. Med. Rep 2017, 16,971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kimura Y; Kimura H FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1165–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lu M; Zhao F-F; Tang J-J; Su C-J; Fan Y; Ding J-H; Bian J-S; Hu G Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2012, 17, 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhang M; Shan H; Wang T; Liu W; Wang Y; Wang L; Zhang L; Chang P; Dong W; Chen X; Tao L Neurochem. Res 2013, 38,714–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Durante W Diabetes 2016, 65, 2832–2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lee ZW; Zhou J; Chen C-S; Zhao Y; Tan C-H; Li L; Moore PK; Deng L-W PLoS One 2011, 6, e21077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Polhemus DJ; Lefer DJ Circ. Res 2014, 114, 730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lefer DJ Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A 2007, 104, 17907–17908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chou S; Ogden JM; Phol HR; Scinicariello F; Ingerman L; Barber L; Citra M Toxicological Profile for Hydrogen Sulfide and Carbonyl Sulfide; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Powell CR; Dillon KM; Matson JB Biochem. Pharmacol 2018, 149, 110–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zheng Y; Yu B; De La Cruz LK; Choudhury MR; Anifowose A; Wang B Med. Res. Rev 2018, 38, 57–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kang J; Li Z; Organ CL; Park C-M; Yang C; Pacheco A; Wang D; Lefer DJ; Xian MJ Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6336–6339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Devarie-Baez NO; Bagdon PE; Peng B; Zhao Y; Park C-M; Xian M Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2786–2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zhao Y; Bolton SG; Pluth MD Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2278–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fukushima N; Ieda N; Kawaguchi M; Sasakura K; Nagano T; Hanaoka K; Miyata N; Nakagawa H Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 25, 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chen W; Chen M; Zang Q; Wang L; Tang F; Han Y; Yang C; Deng L; Liu Y-N Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 9193–9196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yi SY; Moon YK; Kim S; Kim S; Park G; Kim JJ; You Y Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 11830–11833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Sharma AK; Nair M; Chauhan P; Gupta K; Saini DK; Chakrapani H Org. Lett 2017, 19, 4822–4825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fukushima N; Ieda N; Sasakura K; Nagano T; Hanaoka K; Suzuki T; Miyata N; Nakagawa H Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 587–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Xiao Z; Bonnard T; Shakouri-Motlagh A; Wylie RAL; Collins J; White J; Heath DE; Hagemeyer CE; Connal LA Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 11294–11300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhao Y; Pluth MD Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 14638–14642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Steiger AK; Marcatti M; Szabo C; Szczesny B; Pluth MD ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chauhan P; Bora P; Ravikumar G; Jos S; Chakrapani H Org. Lett 2017, 19, 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhao Y; Bhushan S; Yang C; Otsuka H; Stein JD; Pacheco A; Peng B; Devarie-Baez NO; Aguilar HC; Lefer DJ; Xian M ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 1283–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Foster JC; Radzinski SC; Zou X; Finkielstein CV; Matson JB Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 1300–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhao Y; Henthorn HA; Pluth MD J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 16365–16376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zhao Y; Steiger AK; Pluth MD Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 4951–4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bonnet S Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 10330–10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Avci P; Gupta A; Sadasivam M; Vecchio D; Pam Z; Pam N; Hamblin MR Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg 2013, 32, 41–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bonnet S Comments Inorg. Chem 2015, 35, 179–213. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Heilman B; Mascharak PK Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2013, 371, 20120368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Phelps JS; Gandolfi AJ; Brendel K; Dorr RT Toxicoï.Appl Pharmacol. 1987, 90, 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hopkins SL; Siewert B; Askes SHC; Veldhuizen P; Zwier R; Heger M; Bonnet S Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2016,15, 644–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Simpson PV; Schatzschneider U In Inorganic Chemical Biology; Gasser G, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, U. K., 2014; Vol. 54, pp 309–339. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Li L; Whiteman M; Guan YY; Neo KL; Cheng Y; Lee SW; Zhao Y; Baskar R; Tan C-H; Moore PK Circulation 2008, 117, 2351–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Alexander BE; Coles SJ; Fox BC; Khan TF; Maliszewski J; Perry A; Pitak MB; Whiteman M; Wood ME MedChemComm 2015, 6, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bahreman A; Limburg B; Siegler MA; Bouwman E; Bonnet S Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 9456–9469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Li A; Yadav R; White JK; Herroon MK; Callahan BP; Podgorski I; Turro C; Scott EE; Kodanko J Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 3673–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lameijer LN; Ernst D; Hopkins SL; Meijer MS; Askes SHC; Le Dévédec SE; Bonnet S Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 11549–11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sun W; Thiramanas R; Slep LD; Zeng X; Mailänder V; Wu S Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 10832–10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rose P; Dymock BW; Moore PK Methods Enzymol 2015, 554, 143–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Castelblanco M; Lugrin J; Ehirchiou D; Nasi S; Ishii I; So A; Martinon F; Busso NJ Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 2546–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lee Z-W; Teo X-Y; Tay EY-W; Tan C-H; Hagen T; Moore PK; Deng L-W Br. J. Pharmacol 2014, 171, 4322–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Meng G; Wang J; Xiao Y; Bai W; Xie L; Shan L; Moore PK; Ji YJ Biomed. Res 2015, 29, 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Lobb I; Jiang J; Lian D; Liu W; Haig A; Saha MN; Torregrossa R; Wood ME; Whiteman M; Sener A Am. J. Transplant 2017, 17, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Feng W; Teo X-Y; Novera W; Ramanujulu PM; Liang D; Huang D; Moore PK; Deng L-W; Dymock BW J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 6456–6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Knoll JD; Albani BA; Durr CB; Turro CJ Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10603–10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bonnet S; Collin J-P; Sauvage J-P; Schofield E Inorg. Chem 2004, 43, 8346–8354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Wachter E; Heidary DK; Howerton BS; Parkin S; Glazer EC Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 9649–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Mari C; Pierroz V; Ferrari S; Gasser G Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 2660–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Leverrier A; Hilf M; Raynaud F; Deschamps P; Roussel P; Tomas A; Galardon EJ Organomet. Chem 2017, 843, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Peng H; Cheng Y; Dai C; King AL; Predmore BL; Lefer DJ; Wang B Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 9672–9675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Lin VS; Lippert AR; Chang CJ Proc. Natl.Acad. Sci. U. S.A 2013, 110,7131–7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Calvert JW; Jha S; Gundewar S; Elrod JW; Ramachandran A; Pattillo CB; Kevil CG; Lefer D Circ. Res 2009,105, 365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Elrod JW; Calvert JW; Morrison J; Doeller JE; Kraus DW; Tao L; Jiao X; Scalia R; Kiss L; Szabo C; Kimura H; Chow C-W; Lefer DJ Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2007, 104, 15560–15565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Testai L; Marino A; Piano I; Brancaleone V; Tomita K; Di Cesare Mannelli L; Martelli A; Citi V; Breschi MC; Levi R; Gargini C; Bucci M; Cirino G; Ghelardini C; Calderone V Pharmacol. Res 2016, 113, 290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sun X; Wang W; Dai J; Jin S; Huang J; Guo C; Wang C; Pang L; Wang Y Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Snijder PM; de Boer RA; Bos EM; van den Born JC; Ruifrok W-PT; Vreeswijk-Baudoin I; van Dijk MC R F; Hillebrands J-L; Leuvenink HGD; van Goor H. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Donnarumma E; Trivedi RK; Lefer D J. Compr. Physiol 2017, 7, 583–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).DiNicolantonio JJ; OKeefe JH; McCarty MF Open Heart 2017, 4, e000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Freshney RI Culture of Animal Cells, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.