Abstract

As part of an effort to identify druggable diacylglycerol kinase alpha (DGKα) inhibitors, we used an insilico approach based on chemical homology with the two commercially available DGKα inhibitors R59022 and R59949. Ritanserin and compound AMB639752 emerged from the screening of 127 compounds, showing an inhibitory activity superior to the two commercial inhibitors, being furthermore specific for the alpha isoform of diacylglycerol kinase. Interestingly, AMB639752 was also devoid of serotoninergic activity. The ability of both ritanserin and AMB639752, by inhibiting DGKα in intact cells, to restore restimulation induced cell death (RICD) in SAP deficient lymphocytes was also tested. Both compounds restored RICD at concentrations lower than the two previously available inhibitors, indicating their potential use for the treatment of X-Iinked lymphoproliferative disease 1 (XLP-1), a rare genetic disorder in which DGKα activity is deregulated.

Keywords: Diacylglycerol kinase, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease 1, Lipid second messenger, Signal transduction, In silico screening

1. Introduction

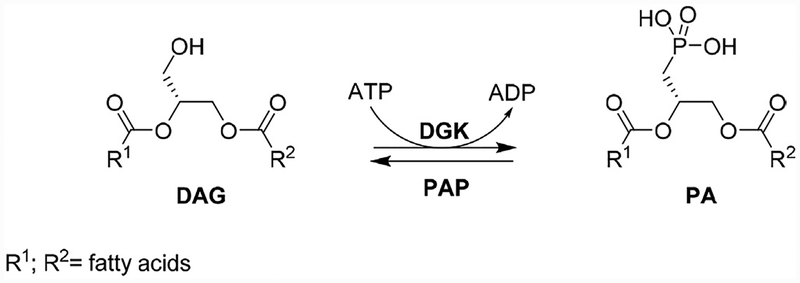

The atypical lipid kinases DGK (diacylglycerol kinases) catalyze the phosphorylation of diacylglycerol (DAG) to phosphatidic acid (PA) (Fig. 1) [1].

Fig. 1.

DAG is phosphorylated by diacylglycerol kinases to phosphatidic acid.

Both these molecules act as second messengers regulating a plethora of biological processes such as cell proliferation and motility, immune responses, glucose metabolism, and cardiovascular responses [2].

DGKs permit to control the cellular concentration of these two bioactive lipids, terminating the DAG signaling and increasing the concentration of PA [3], and it is not surprising that an up- or down-regulation of DGKs has been linked with several pathological conditions such as cancer, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, bipolar disorders, cardiac hypertrophy, type II diabetes, and hypertension [4]. Among the ten human isoforms of DGK (a, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, η, θ ι, and κ) [5], the most studied one is the α isoform which is particularly expressed in the central nervous system, spleen, thymus, T cells, and lungs. Interestingly, it has been shown that the inhibition of the α form can be a valuable strategy for the discovery of novel anti-cancer compounds [6]. Indeed, this enzyme is overexpressed in several malignancies, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma and melanoma cells, showing pro-tumoral and anti-immunogenic properties, and its inhibition damages cancer cells viability, blocks the angiogenetic process and, remarkably, it increases the T cells activation [7,8].

Another disease linked with overactivation of DGKα is the X-linked lymphoproliferative disease type 1 (XLP-1) a primary immunodeficiency of genetic origin characterized by dysgammaglo-bulinaemia and poor CD8+ cytotoxic T cell function, with some patients developing lymphomas of the bowel, peritoneum, and brain [9]. Most importantly, XLP-1 patients face significant morbidity and mortality in response to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, which causes marked lymphoproliferative disease, featuring fulminant infectious mononucleosis (FIM), cytopenia, liver failure, hepatosplenomegaly, and/or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [10]. XLP-1 is due to loss of function mutations of the 128-amino acid signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM)–associated protein (SAP) adaptor molecule. Loss of SAP in XLP-1 patients impairs both adaptive and innate immunity, resulting in several immunologic alterations. Notably, a block in NKT-cell development [11]; decreased NK and CD8+ cytotoxicity, specifically toward EBV-infected B-cell targets [12]; impaired CD4+ T helper function and B cell conjugation, resulting in reduced germinal center formation and ineffective antibody production [13] and resistance to restimulation induced cell death (RICD), a homeostatic mechanism preventing excessive Tcell proliferation [14]. Interestingly, the signaling alterations reported in SAP deficient cells are consistent with a reduced DAG signaling due to increased DGKα activity [15]. Indeed, TCR signaling inhibits DGKα through a signaling pathway that requires PLC activity and calcium but also the expression of SAP [15]. Thus, T cells from XLP-1 patients, which lack functional SAP, feature deregulated DGKα activity, which is a main contributor of the defective lymphocyte responses observed both in XLP-1 patients and in SAP KO mice. Indeed, pharmacolog-ical inhibition of DGKα restores RICD in lymphocytes from XLP-1 patients and prevents the excessive CD8+ T cell expansion and interferon-γ production that occur in SAP-deficient mice after lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus infection [16]. Collectively, these data highlight DGKα as a viable therapeutic target to reverse the life-threatening EBV-associated immunopathology that occurs in XLP-1 patients.

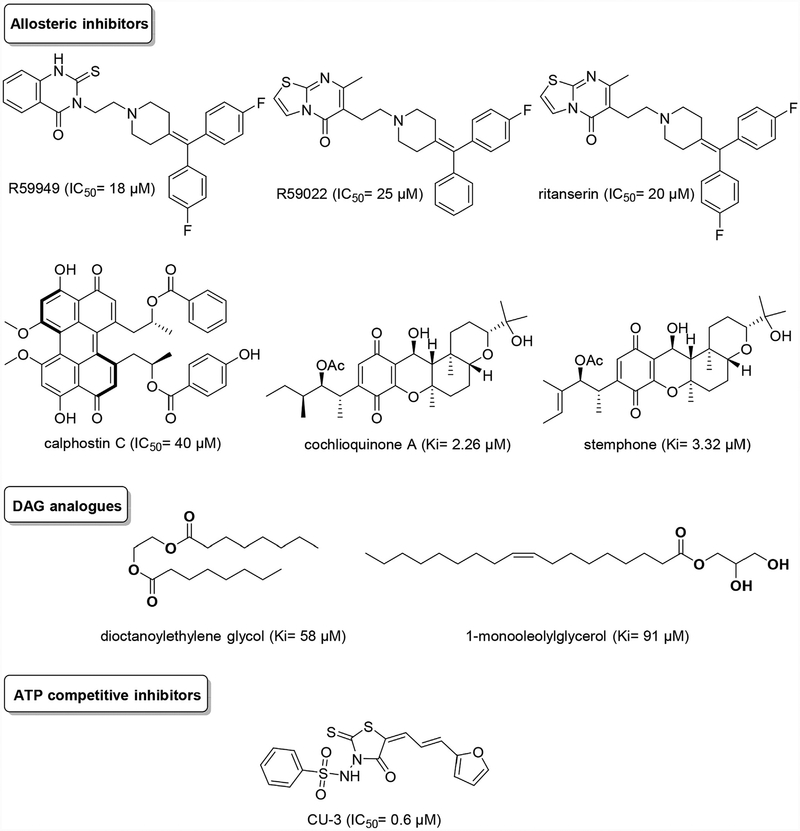

To date, a handful of DGKs inhibitors have been discovered, but some drawbacks are associated with their use as drugs such as low potency, lack of selectivity, off-target effects and poor pharmaco-kinetic properties. In Fig. 2 are reported the best documented DGK inhibitors, which can be gathered in three main groups: i) allosteric inhibitors; ii) DAG analogues and iii) competitive inhibitors at the ATP binding site.

Fig. 2.

DGKs inhibitors: state of the art.

In the class of allosteric inhibitors, the two compounds R59949 and R59022 are the most important discovered to date [17,18], show selectivity for DGKα [19] and they have been important pharmacological tools for studying the role of DGKs in cells. The IC50 values of R59022 and R59949 are dependent by assay conditions: using whole cell lysates of DGKα overexpressing Cos-7 cells in a nonradioactive assay method, the IC50 values of R59022 and R59949 were approximately 25 μM and 18 μM, respectively [19,20]. In the original reports, however, R59022 featured an IC50 of 3.8 μM on erythrocyte ghosts while R59949 displayed an IC50 of 0.3 μM on platelet membranes [17,18]. It has been postulated that R59949 binds to the catalytic domain of DGKα in synergy with Mg-ATP without affecting DAG binding. Putatively R59949 acts by binding in proximity to the Mg-ATP site or promoting a conformational change of the enzyme that exposes both Mg-ATP and R59949 binding sites [20]. However, their use in vivo is severely limited by poor pharmacokinetic properties, and several off-target activities (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/). Despite these drawbacks and its short half-life, R59022 has been used in mice with positive results in glioblastoma models and in XLP-1 [16,21]. Based on structural similarity with R59022, ritanserin was recently characterized as an active non-competitive inhibitor of DGKα with an IC50 around 20 μM [22]. Structural studies support a contiguous ligand-binding site composed of C1, DAGKc, and DAGKa domains in the DGKα active site for this class of inhibitors [23,24]. Both ritanserin, and R59022/R59949 are also antagonists of serotonin receptors. For example, ritanserin was indeed originally described as a selective 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.45 nM) and 5-HT2C receptor (Ki = 0.71 nM) antagonist and underwent clinical trials for the treatment of schizophrenia and other mental diseases [25].

The class of DAG analogues has not produced potent and pharmacologically useful DGK inhibitors to date with dioctanoylethylene glycol (Ki = 58 μM) and 1-monooleolylglycerol (Ki = 91 μM) the two most potent inhibitors found [26,27]. To note that phorbol esters, well-known DAG mimetic on PKC, are active only with the β and γ isoform, while they have no activity on the other eight isoforms [28,29]. Finally, it is important to highlight the problem of identifying ATP competitive inhibitors of DGKs. The reason lays in their different ATP binding pocket compared to serine-tyrosine kinases but also to lipid kinases such as PI3Ks. The different architecture of the ATP binding pocket is exemplified by the total lack of activity of the pan-kinase inhibitor staurosporine on DGKs [28]. Very recently, a compound named CU-3 was identified via high throughput screening. In a non-radioactive assay method, CU-3 was able to inhibit DGKα with an IC50 value of 0.6 μM in DGKα overexpressing Cos-7 cells. Moreover, CU-3 acts as a competitive inhibitor of DGKα that reduces affinity of DGKα for ATP, but not diacylglycerol or phosphatidylserine [30].

The goal of this work was therefore to identify novel druggable inhibitors of DGKα, for the treatment of XLP-1 using a virtual screening approach. As there is no detailed structural information on DGKα catalytic domain, we searched for new inhibitors using R59022 and R59949 as templates to explore the chemical space via 2D/3D virtual screening approaches. Herein, we report that out of 127 compounds tested, ritanserin and AMB639752 were more active than the lead inhibitors R59022 and R59949. We also show that both compounds can restore TCR pro-apoptotic signaling and RICD in SAP-deficient T cells, suggesting their use for treatment of EBV-induced FIM in XLP-1 patients. Moreover, AMB639752 does not perturb serotonin signaling indicating an increased selectivity.

2. Result and discussion

2.1. in silico drug discovery

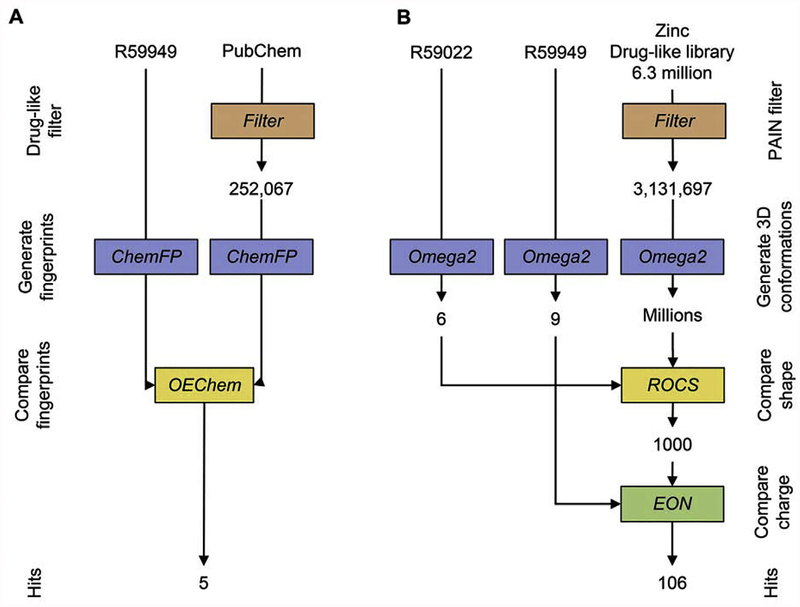

Starting from the structure of R59949 and R59022, we commenced with a fast in-silico molecular comparison method to calculate molecular similarity of target substances to both reference compounds (2D-similarity-based virtual screening). In brief, the 2D fingerprint-based methods encode the structural features of molecules as bit strings, whereby each bit indicates the presence or absence of pre-defined structural patterns such as atom sequences, electronic configurations, atom pairs, and ring systems. We used the PubChem library and selected molecules with a Tanimoto coefficient ≥0.75 in comparison with R59949 (reference compound). Five compounds emerged from this screening (R59022, altanserin, ritanserin, ketanserin, pimozide) (Fig. 3A). As all the identified compounds were already evaluated as serotonin receptor antagonists, we decided to select other 24 serotonin receptor antagonists as negative control for DGKα inhibition (Supplementary Table S1). Of those, only 21 compounds resulted commercially available (R59022, ritanserin, ketanserin, pimozide and 17 negative controls) and were included in the subsequent screen. Subsequently, we used an in-silico 3D approach using R59022 and R59949 as query ligands to identify in the ZINC database24 compounds with similar three-dimensional shape and electrostatic properties compared with the two standards.

Fig. 3.

Virtual screening protocols details. A) Flow chart outlining the protocol used in the 2D-Similarity-based virtual screening. B) Flow chart outlining the protocol used in the 3D-Similarity-based virtual screening.

Of note, our query compounds contain several rotatable single bonds and their bioactive conformations are unknown. Therefore, in our shape-based virtual screening strategy we explored a range of possible conformations of templates by screening against the most stable conformations of both R59022 (9 conformers) and R59949 (6 conformers) generated with Omega [31]. After generation of conformers for each ZINC compound in the “drug-now” subset, the 3D shape comparison between R59s and the molecules in the ZINC library was performed by ROCS [32], in which shape is approximated by atom-centered overlapping Gaussians and calculates the maximal intersection of the volume of two molecules. The top 1000 ‘hits’ were re-ranked for similarity to R59s based on electrostatics with the program EON [33]. Electrostatic rank was based on an electrostatic Tanimoto score, ranging from 0 to 2, where 2 represents an exact match of both shape and functional groups between two molecules. We selected the top 150 compounds and purchased the 106 compounds that were commercially available (Fig. 3B). Full details for these compounds including their structures, Tanimoto ranks and chemical identification numbers are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

2.2. Biological results

To identify the active compounds between those emerged from the two in-silico screenings, all the candidates were dissolved in DMSO and tested at a concentration of 100 μM for the ability to inhibit DGKα using equal amounts of DMSO as control. Assay uses OST-DGKα overexpressing cell lysates in presence of saturating exogenous DAG and ATP [34]. Due to the poor solubility, risperidone and AMB9107756 were not included in this assay, resulting in 127 compounds tested. Each inhibitor was tested in duplicate, and DGKα activity was expressed as percentage of residual DGKα activity compared to DMSO control in the same assay. Out of the 127 compounds, we identified 17 compounds capable of reducing OST-DGKα activity at least by 25% (Table 1). As expected, our reference inhibitors R59022 and R59949 featured 73% and 72% inhibition respectively, confirming the quality of data obtained. Interestingly, ritanserin and above all the new entry AMB639752 inhibited OST-DGKα better than R59022 and R59949, thus representing novel DGKα inhibitors. In order to confirm the structure and purity of AMB639752, NMR structural characterization, mass analysis and elemental analysis were carried out, verifying the correctness of the structure (see “Experimental protocols” section).

Table 1.

Compounds that inhibit DGKα at least by 25%.

| Sl.No | Code | Name | Residual DGKα activity at 100 μM (% of control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Amb639752 | 4 | |

| 2. | R103 | ritanserin | 17 |

| 3. | R59022 | diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor I | 27 |

| 4. | R59949 | diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor II | 28 |

| 5. | Amb3494010 | 39 | |

| 6. | Amb19541048 | 49 | |

| 7. | Amb8223059 | 50 | |

| 8. | Amb11070312 | 57 | |

| 9. | H0972 | haloperidon | 62 |

| 10. | Amb242047 | 64 | |

| 11. | Amb20056316 | 67 | |

| 12. | Amb8244320 | 68 | |

| 13. | Amb110991 | 68 | |

| 14. | E0925 | ebastine | 69 |

| 15. | Amb252835 | 72 | |

| 16. | U0085 | urapidil | 75 |

| 17. | Amb19382197 | 75 |

Surprisingly, in this assay, more than 60% of the compounds stimulated DGKα activity, with some compounds enhancing the enzyme activity by several folds. We can confirm that the most active one, fluoxetine, significantly enhances DGKα activity in vitro (Fig. S1). As reported for the parental compounds, these molecules may enhance affinity for Mg-ATP or promote an active enzyme conformation by inserting in an allosteric pocket [23,24]. However, for the moment, we did not investigate these compounds further.

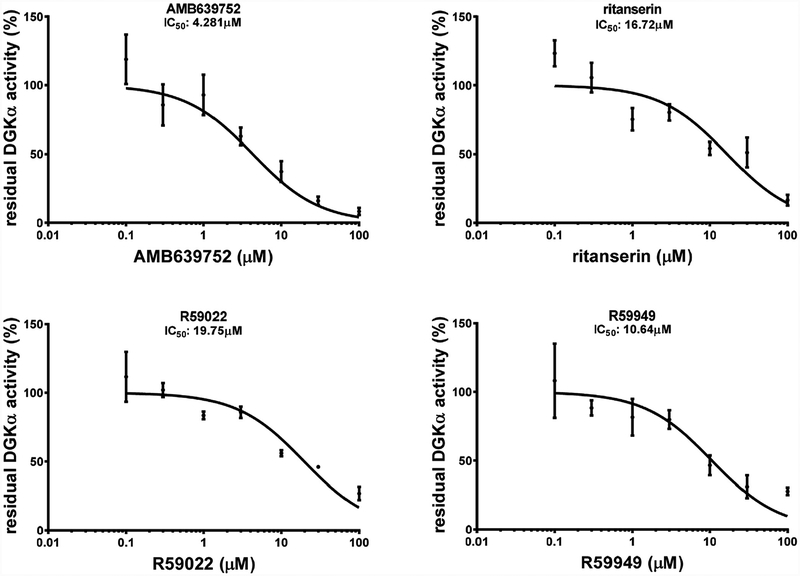

2.3. Potency and isoform specificity of ritanserin and AMB639752

To measure the inhibitor potency, we determined the IC50 values for active compounds by measuring the residual OST-DGKα activity over a dose range of inhibitor concentrations (0.1, 0.3,1.0, 3.0,10.0, 30.0 and 100.0 μM). For R59022 and R59949 we measured IC50 values of 19.7 ± 3.0 μM and 10.6 ± 3.2 μM respectively, comparable to previous reports using similar assay conditions [19,20]. Conversely, we found IC5o values of 16.7 ± 4.6 μM for ritanserin and 4.3 ± 0.6 μM for AMB639752 (Fig. 3). Those results indicate a superior potency of AMB639752 with respect to both ritanserin and the template compounds.

127 molecules were dissolved in DMSO and tested at 100 μM for the capacity to inhibit DGKα in homogenates of OST-DGKα over-expressing MDCK cells. Dose response of the most active compounds along with their IC50 values is shown. Data from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

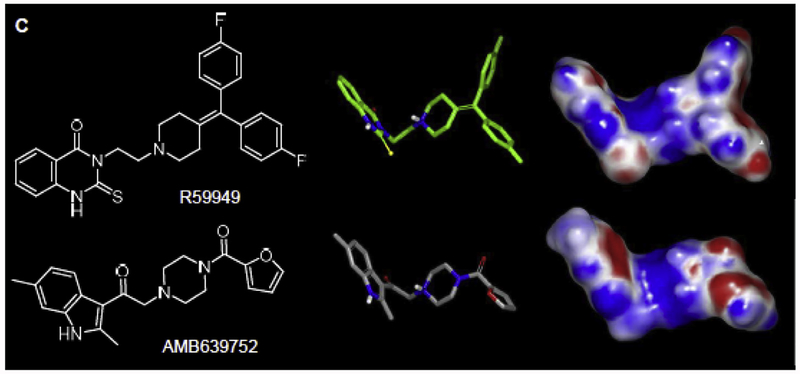

Concerning similarity to R59s, AMB639752 is different with respect to their chemical scaffold, but similar in three-dimensional shape, as demonstrated by their shape Tanimoto’s ranks (0.623, Supplementary Information Table S2). AMB639752 is also electrostatically similar to R59949, with an electrostatic Tanimoto of 0.745 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Biochemical screen for novel DGKα inhibitors.

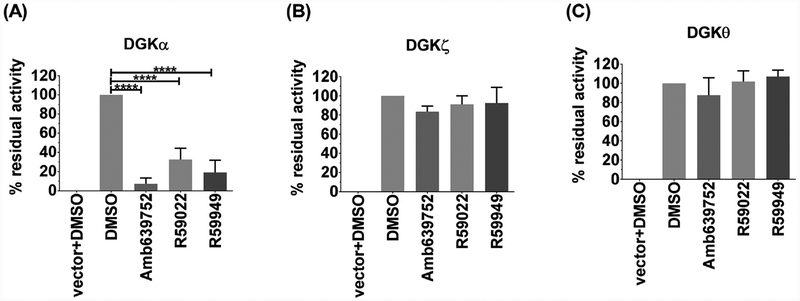

To check the isoform specificity of AMB639752, we tested it along with R59s, for the ability to inhibit DGKα, DGKζ (the other major DGK isoform expressed in lymphocytes), and the more distantly related DGKθ. Also at the highest concentration of 100 μM, R59022, R59949 and AMB639752 are highly specific against DGKα as they completely inhibit DGKα (68%, 81%, 93% respectively, Fig. 5A) while they do not have significant effects on DGKζ (Fig. 5B) and DGKθ (Fig. 5C). Similar results were reported for ritanserin [22] indicating that this class of inhibitors is highly specific for DGKα.

Fig. 5.

2D, 3D and shape of R59949 and Amb639752 chemical structures. Electrostatic surfaces are color coded (red for negative and blue for positive).

2.4. Activity of compounds on serotonin receptors

As R59022, R59949 and ritanserin feature a dual activity as DGKα inhibitors and serotonin receptor antagonists [22], we investigated whether also AMB639752 affects serotonin signaling.

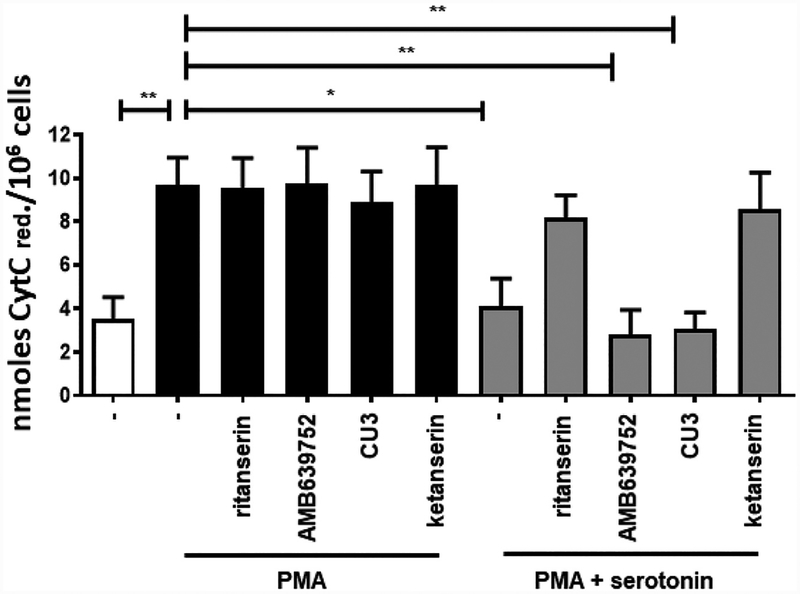

To this purpose, we measured the effect of serotonin on PMA-induced oxidative burst in human monocytes. As previously shown, 1 μM serotonin reverses the oxidative burst to control values [35]. When tested at 10 μM, the known serotonin receptor antagonists ritanserin and ketanserin impaired serotonin action, while pure DGKα inhibitors such as CU-3 had no effect (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

AMB639752 does not affect serotonin signaling. Human monocytes were pre-incubated for 1 h with the indicated drugs (10 μM) in absence or presence of serotonin (1 μM) and then stimulated with PMA 1 μM for 30min (□ control unstimulated cells, ■ PMA treated cells,  PMA and serotonin stimulated cells). Results are expressed as nmoles of reduced cytochrome C/106 cells. Data are means ± S.E.M. of 6 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

PMA and serotonin stimulated cells). Results are expressed as nmoles of reduced cytochrome C/106 cells. Data are means ± S.E.M. of 6 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

These data indicate that this assay is sensitive to perturbations in serotonin signaling independently of activity against DGKα. AMB639752, despite sharing surface similarity with R59949 and ritanserin, did not affect serotonin action demonstrating that it is not a serotonin receptor antagonist. This interesting observation suggests a better pharmacological profile for AMB639752, which inhibits DGKα without off-target effects on serotonin receptors.

2.5. DGKα specific inhibitors restores R¡CD in SAP deficient T cells

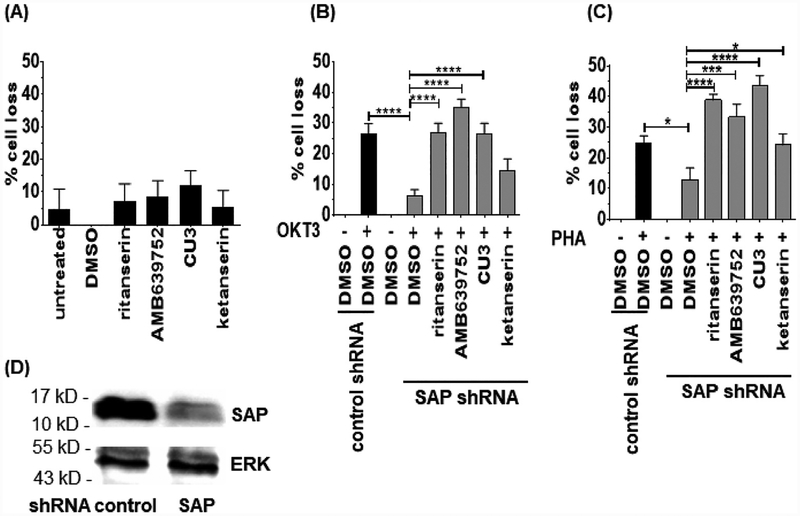

The defective RICD observed in T cells from XLP-1 patients was rescued by silencing DGKα expression or by pre-treatment with DGKα inhibitors R59949 or R59022 at 5–10 μM [16]. Interestingly, R59022 also showed beneficial effects in an in vivo model ofXLP-1, but its poor pharmacological proprieties make its use in human patients unlikely. We therefore tested the effect of ritanserin and AMB639752 on RICD sensitivity of SAP-deficient T cells. As additional controls, we also included ketanserin to evaluate the contribution of serotonin antagonism to the effects observed and CU-3 as representative of a different class of molecules inhibiting DGKα by competing with ATP. To model XLP-1 T cells in vitro, we previously silenced SAP in Jurkat cells [15], a widely used cellular model for RICD mediated by FAS induction [36]. RICD was induced by treatment with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3, 50 μg/ml) or PHA (50 μg/ml) [37]. As expected, SAP-silenced Jurkat cells showed reduced RICD compared to cells transfected with a control siRNA, making this an easy model for testing our inhibitors (Fig. 8B and C). The inhibitors were not overly toxic to Jurkat cells as 24-h treatment at 1 μM doses did not decrease the viability of Jurkat cells, apart for a modest toxicity of CU-3 (Fig. 8A). At this concentration, ritanserin, AMB639752 and CU-3 significantly promoted RICD in SAP-silenced Jurkat cells, restoring death to levels noted in Jurkat control cells after either anti-CD3 (Fig. 8B) or PHA (Fig. 8C) treatment. Conversely, ketanserin only had a modest effect (Fig. 8B and C). These data indicate that the new DGKα inhibitors identified by our screen can restore RICD in this cell model of XLP-1. Furthermore, our results suggest these effects result from inhibiting DGKα independently of eventual activity on serotonin receptors.

Fig. 8.

DGKα inhibitors rescues RICD in SAP deficient Jurkat cells. Jurkat T cells (control shRNA ■ and SAP shRNA  ) were treated with ritanserin, AMB639752, CU-3 or ketanserin (1 μM) and plated on a 96 well flat bottom plate previously coated with nothing (A), anti CD3 (OIKΓ3 50 μg/ml, B) and PHA (50 μg/ml, C). After 24 h of incubation, live cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion assay and expressed as % of cell loss respect to untreated controls. The data are the means of ±SEM of at least five experiments performed in triplicate. D) Western blot confirming the silencing of SAP in SAP shRNA Jurkat cells compared with control shRNA Jurkat cells.

) were treated with ritanserin, AMB639752, CU-3 or ketanserin (1 μM) and plated on a 96 well flat bottom plate previously coated with nothing (A), anti CD3 (OIKΓ3 50 μg/ml, B) and PHA (50 μg/ml, C). After 24 h of incubation, live cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion assay and expressed as % of cell loss respect to untreated controls. The data are the means of ±SEM of at least five experiments performed in triplicate. D) Western blot confirming the silencing of SAP in SAP shRNA Jurkat cells compared with control shRNA Jurkat cells.

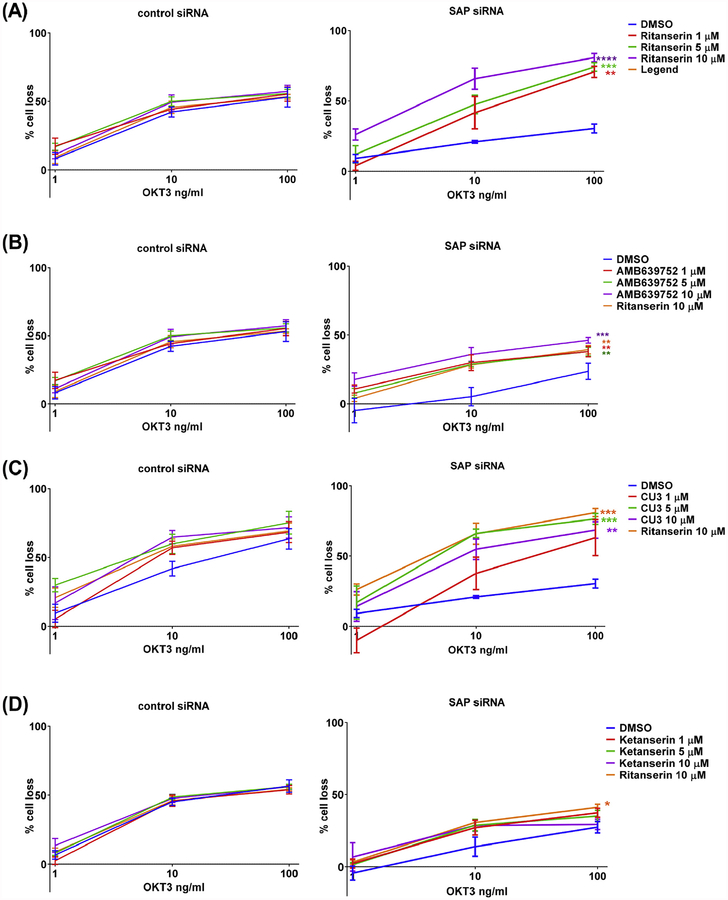

To assess inhibitor efficacy in a more physiological context, we also modelled XLP-1 by silencing SAP in primary peripheral blood T lymphocytes (PBL) and re-stimulating them with increasing doses of anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3 1–100ng/ml, 24 h). In these assay conditions, 30-min pre-treatment with R59949 or R59022 restored RICD sensitivity in SAP silenced cells at concentrations of 5–10 μM [16]. Also in this setting, ritanserin does not influence RICD induced by CD3 triggering in control siRNA-transfected cells, indicating that it is neither affecting TCR signaling nor is cytotoxic to primary cells at concentrations between 1 and 10 μM. Conversely, ritanserin completely rescued the apoptotic defect in SAP-deficient T cells at concentrations as low as 1 μM (Fig. 9A). We used ritanserin 10 μM as reference for further sets of experiments (we always compare controls and SAP silenced lymphocytes from the same donors as there is a large individual variability in RICD sensitivity). AMB639752 demonstrated similar activity, not affecting RICD sensitivity in control lymphocytes, but fully rescuing the RICD defect of SAP-deficient cells also at 1 μM concentration and with a potency equal to 10 μM ritanserin (Fig. 9B). When we tested the ATP competitive DGKα inhibitor CU-3, we observed a modest induction of RICD in control-silenced lymphocytes that is absent in the other molecules tested. In SAP-silenced cells, CU-3 improved RICD sensitivity approaching ritanserin levels when used at concentrations ≥5 μM, (Fig. 9C). These observations suggest that CU-3 has a narrower therapeutic window with some likely cytotoxicity at higher doses. Finally, we tested ketanserin in our RICD assays to verify if serotonin receptor antagonism could contribute to the observed effects. Interestingly, ketanserin had no effect on RICD in control cells, but partially increased RICD in SAP-silenced T cells, although this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 9D). These findings are in line with our Jurkat cell experiments, suggesting that inhibition of DGKα is an efficient strategy to rescue of RICD in XLP-1 models, while serotonin antagonism plays a minor role.

Fig. 9.

DGKα inhibitors rescues RICD in SAP deficient T cells. Lymphocytes from normal subjects were transfected with control or SAP specific siRNA. A, B, C, D) After 4 days, the cells were restimulated with increasing doses of CD3 agonist OKT3 (1,10,100 ng/ml) in presence or absence of (A) ritanserin, (B) AMB639752, (C) CU-3, (D) ketanserin (1,5,10 μM). 24 h later, the % of cell loss was evaluated by PI staining. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

In summary, these data confirm that ritanserin and AMB639752 rescue RICD susceptibility in T cell models of XLP-1. Our observations are consistent with those on DGKα-silenced cells [16], indicating that DGKα is a relevant pharmacologic target for restoring RICD and immune homeostasis in XLP-1 patients.

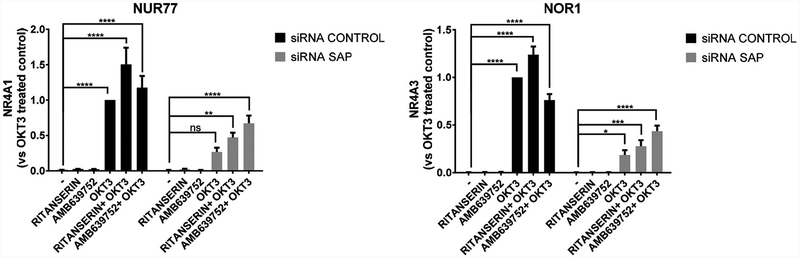

2.6. DGKα specific inhibitors potentiates TCR signaling and induces expression of the pro-apoptotic nuclear receptors Nur77 and Nor1 in SAP deficient T cells

Silencing DGKα expression or pre-treatment with DGKα inhibitors R59949 or R59022 boosts RICD in SAP-deficient T cells by selectively restoring TCR-induced upregulation of the pro-apoptotic orphan nuclear receptors NUR77 (NR4A3) and NOR1 (NR4A1) [16]. To verify if ritanserin and AMB639752 acts through the same mechanism, we measured TCR-dependent induction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 in SAP-silenced activated T cells. Indeed, ritanserin potentiated TCR-induced NR4A1 expression in control cells and to a lesser extent, in SAP silenced cells. In contrast, AMB639752 was more active in rescuing NR4A1 and NR4A3 in SAP-silenced activated T cells (Fig. 9). These observations suggest that both ritanserin and especially AMB639752 restore RICD by promoting the expression and apoptotic activity of NR4A1 and NR4A3 (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

DGKα inhibitors rescues Nur77 and Nor1 expression in SAP deficient T cells. Lymphocytes from normal subjects were transfected with control or SAP specific siRNA. After 4 days, the cells were restimulated with the CD3 agonist OKT3 (10 μg/ml) in presence or absence of ritanserin or AMB639752 at 10 μM concentration. 4h later, the expression of NR4A1 and NR4A3 evaluated by quantitative PCR using GUSB as a reference. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments.

3. Conclusion

Summarizing, the purpose of this project was to discover novel inhibitors against DGKα suitable for future clinical trials in XLP-1 patients. To find potentially drug candidates, we explored in-silico the chemical space of ZINC by using the two commercially available inhibitors (R59022 and R59949) as templates. We assembled a library of 127 compounds using this approach, including both uncharacterized molecules and a series of compounds already in clinical use or development.

By screening this library, we found 17 active inhibitors, with two more active than the lead compounds: the compound AMB639752 and ritanserin. We defined the IC50 values of ritanserin (16.7 ± 4.5 μM) and AMB639752 (4.3 ± 0.6 μM) for inhibiting DGKα. Thus, IC50 value of AMB639752 compares favourably with ritanserin, R59022 (19.7 ± 3.0 μM) and R59949 (10.6 ± 3.2 μM) in the same assay. Interestingly 60% of the compounds in the library acted as activators and not inhibitors of DGKα (see supporting information). These compounds might bind to the same pocket as R59949 and increase affinity for Mg-ATP or stabilize an active conformation. Further studies will explore whether these DGKα activators may offer interesting opportunities for the control of DAG metabolism in pathological settings such as inflammation.

AMB639752 maybe a promising molecule for a drug optimization program, as it potently inhibits DGKα without influencing serotonin signaling on the contrary of ritanserin. AMB639752 was highly active in cell-based assays, with negligible cytotoxicity at concentrations used for the two commercially available DGK inhibitors. Moreover, it did not alter RICD sensitivity of control (SAP-sufficient) lymphocytes. Both ritanserin and AMB639752 restore RICD in SAP-deficient cells at 1, 5 and 10 μM concentration, consistent with DGKα inhibition. At these doses, neither compound displayed toxicity nor impaired TCR signaling. Both drugs restored the induction of key pro-apoptotic molecules NUR77 and NOR1 in SAP-deficient cells, but AMB639752 was far more active. This indicates that similarly to R59s and DGKα silencing, ritanserin and AMB639752 are not simple TCR signal enhancers, but selectively influence SAP-dependent downstream signaling outcomes that promote RICD. Altogether, these observations support our initial hypothesis that excessive DGKα activity contributes to XLP-1 pathogenesis and suggest that we are moving in the right direction to find new compounds for countering life threatening disease complications in this disease (e.g. EBV-induced FIM).

4. Experimental protocols

4.1. Structural confirmation for AMB639752

AMB639752 or 1-(2,5-dimetil-1H-indol-3-yl)-2-(4-(furan-2-carbonil)piperazin-1-yl)etan-1-one: yellowish solid; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.70 (br s, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.13 (s, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.2 Hz), 6.98 (br d, 1H), 6.47 (br d, 1H), 3.92 (br s, 4H), 3.85 (s, 2H), 2,79 (br s, 4H), 2,74 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H); MS (ESI): m/z = 366 [M + H]+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C21H23N3O2: C 69.02, H 6.34, N 11.50: found: C 69.23, H 6.58, N 11,33.

4.2. Cell lines

Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK) stably expressing One Strep Tag DGKα (OST-DGKα) were prepared by infecting MDCK cells with a vector expressing an inducible OST tagged DGKα constructs [38]. MDCK cells infected with empty vector were used as controls. MDCK cells were cultured in MEM (Minimal Essential Medium) with 5% FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. Routinely, cells were split every 3–4 days with Trypsin-EDTA 0.25% in standard 100 mm dishes.

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells (10 cm2 plates) were cultured in RPMI with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Generation of Jurkat shRNA SAP and the Jurkat shRNA control was described in Ref. [15]. Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI-GlutaMAX (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS (Lonza) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies).

4.3. Primary cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy anonymous human buffy coats (provided by the Trans-fusion Service of Ospedale Maggiore della Carità, Novara, Italy) by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation, washed, and resuspended at 2 ×106 cell/ml in RPMI-GlutaMAX containing 10% heat inactivated FCS, 2 mM glutamine, and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. T cells were activated with 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 (clone OIKΓ3) and anti-CD28 (clone CD28.2) antibodies. After 3 days, activated T cells were washed and cultured in medium supplemented with 100 IU/ml rhIL-2 (Peprotech) at 1.2 × 106 cells/mL for ≥7 days by changing media for every 2–3 days.

Human monocytes were isolated from healthy anonymous human buffy coats (provided by the Transfusion Service of Ospedale Maggiore della Carità, Novara, Italy) by the standard technique of dextran sedimentation and Histopaque (density = 1.077 g cm3, Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) gradient centrifugation (400 × g, 30min, room temperature) and recovered by fine suction at the interface, as described previously [35]. Purified monocytes populations were obtained by adhesion (90min, 37 °C, 5% CO2) in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics. Cell viability (trypan blue dye exclusion) was usually >98%.

4.4. Molecular modelling

All molecular modelling studies were performed on a Tesla workstation equipped with two Intel Xeon X5650 2.67 GHz processors and Ubuntu 11.10 (www.ubuntu.com). The protein structures and 3D chemical structures were generated in PyMOL [The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3; Schrödinger LLC: 2010].

2D-Similarity-based virtual screening. The collection of com-pounds was retrieved from PubChem (February 2nd, 2013), this searchable database includes chemical structures available from published literature [39]. The structures were downloaded and filtered using software FILTER [FILTER, version 2.0.2; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM. http://www.eyesopen.com]: molecular weight <500 Da and >150, logP ≤5, number of rotatable bonds ≤7, polar surface area <150, number of hydrogen bond donor ≤5 and number of hydrogen bond acceptor ≤10. Using these criteria 252,067 structures were retrieved. First, the ChemFP Substructure fingerprints were generated for the compounds using chemfp v1.1 [chemfp, version 1.1; Dalke Scientific: Sweden, 2013. http://chemfp.com], with the OEChem [OEChemTK, Python version 1.7.7; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM. http://www.eyesopen.com], was used to select compounds that are similar to R59949 by at least a Tanimoto cutoff of 0.75; 5 compounds were selected (Table 1). In order to qualitatively validate the approach 24 other compounds with similar biological activity, not selected by our method, were used as negative control (Supplementary Table S1).

3D-Similarity-based virtual screening. The collection of com-pounds was retrieved from ZINC (February 19th, 2014), this searchable database includes chemical structures available from vendors [40,41]. The “drug-now” subset, that contains molecules with drug-like properties (molecular weight <500 Da and >150, logP ≤5, number of rotatable bonds ≤7, polar surface area <150, number of hydrogen bond donor ≤5 and number of hydrogen bond acceptor ≤10), was downloaded. Using these criteria, 6,366,032 structures were retrieved. An in-house Perl script was used in order to standardize charges, enumerate ionization states, generate tautomers at physiological pH range and remove PAINS substructures 62 using the FILTER and QUACPAC software from OpenEye (FILTER, version 2.5.1.4; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com; QUACPAC, version 1.6.3.1; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM, http://www.eyesopen.com). 3,131,697 structures were retained. The latter operation was followed by a 3D structure optimization and conformers generation using OMEGA2 software (OMEGA, version 2.4.6; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM. http://www.eyesopen.com) [31,42]. A three dimensional structures of R59022 and R59949 were built: we used OMEGA2 software to generate 9 conformers of R59022 and 6 conformers of R59949. A RMSD cutoff of 0.75 Å was used in this step. Successful candidates were filtered using shape matching. ROCS software was used for 3D shape comparisons (ROCS, version 2.4.1; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM. http://www.eyesopen.com) [32]. The top 1000 structure were considered for electrostatic comparisons, EON was used (EON, version 2.0.1; OpenEye Scientific Software: Santa Fe, NM. http://www.eyesopen.com) [33]. The best compounds were selected based on Tanimo-toCombo values (ShapeTanimoto + ElectrostaticTanimoto). At the end the best 150 compounds were considered, 106 compounds were commercially available and were retrieved from Ambinter vendor (Supplementary Table S2).

All these compounds, including the two known inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mM AMB9107756 remains undissolved and due to solubility problems ebastine (E0925) was dissolved at 5 mM, risperidone (R3030) at 1 mM concentrations respectively.

ATPγ32P is from PerkinElmer, cell culture reagents are from Thermo Fisher, all other chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich. CU-3 is a king gift of F. Sakane (Chiba University, Japan).

4.5. Preparation of DGKα enriched homogenates

Large cultures for enzyme preparation were done by plating 5 × 106 cells in 245 mm2 dishes. Once they reached nearly 70% confluence, cells were treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml, 2 days). After 2 days of treatment, each plate was washed in cold PBS and cells homogenized in 5 ml of homogenate buffer (25 mM Hepes (pH 8), 20% glycerol, 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraaceticacid (EDTA), 1 mM ethylene glycolbis(beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate and protease inhibitor cocktail) for each dish. Cells were collected with a rubber scraper, homogenized by passing them through a 29G-needle syringe 20 times and stored in aliquots at −80 ° C. Presence of OST-DGKα was confirmed by western blotting and enzyme assay, transduced DGKα has an activity >100 folds the endogenous DGK.

4.6. Preparation ofDGKζ and DGKΘ enriched homogenates

293T cells were transiently transfected with indicated DGK isoform plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 3000, Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested and homogenized with a 29G-needle using 500 μl/plate of homogenate buffer for each dish and immediately stored in aliquots at −80 °C. Cells transfected with empty vector were used as controls, over-expressed DGK has an activity >50 folds the endogenous.

4.7. DGK assay

DGK activity was assayed by measuring initial velocities (5minat 27 °C) in presence of saturating substrate concentration. Reaction mixture comprises enzyme (24.5 μl of homogenate), inhibitor or DMSO (0.5 μl), ATP solution (10 μl) and DAG solution (15 μl).

ATP solution contains and 0.25 μCi/μl (9.25 KBq/μl) of γ32P labelled radioactive ATP along with 25 μM normal unlabeled ATP, 50 μm MgCl2, 5 μm sodium orthovanadate and water to make up the final volume.

DAG solution contains 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol (3 μg/μl) and 1 mM EGTA in 25 mM Hepes pH 8. DAG is stored in CH3OH:CHCl3 1:1 solution at 10 μg/ml, the required amount was dried using N2 or vacuum centrifugation and sonicated extensively in ice could buffer.

The reaction was stopped after 5 min by adding 200 μl of freshly prepared 1M HCL and lipid extracted by adding 200 μl of CH3OH:CHCl3 1:1 solution and vortexing for 1 min. The two phases were separated by centrifugation (12000 RCF for 2 min). 25 μl of the lower organic phase was spotted in small drops on silica TLC plates (previously coated with (1.3% potassium oxalate and 5 mM EDTA in methanol and dried). Mobile phase was CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O:25% NH4OH (60:47:11:4).

TLC was run 10 cm and dried before radioactive signals were detected by GS-250 molecular imager and was quantified by quantity one (Bio-Rad) software assuring the absence of saturated spots.

Percentage residual activity was calculated as follows:

4.8. Superoxide anion (O2−) production

All the experiments were performed in triplicate using cells isolated from each single donor.

Monocytes (250.000 cells/well) were treated for 1 h with the indicated drugs (10 μM) with or without serotonin (1 μM). Then, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich) 1 μM for 30 min. PMA is a well-known stimulus that induces a strong and significant respiratory burst via PKC activation [35]. Superoxide anion production was then evaluated by the superoxide dismutase (SOD)-sensitive cytochrome C (CytC) reduction assay and expressed as nmoles cytochrome C reduced/106 cells/30 min, using an extinction coefficient of 21.1 mM. To avoid interference with spectrophotometric recordings, cells were incubated with RPM11640 without phenol red, antibiotics and FBS.

4.9. RICD assay in Jurkat cells

Treatments with inhibitors were done in 96-well flat-bottom plate, pre-coated with anti CD3 (clone OKT3, 50 μg/ml) or phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P Sigma, 50 μg/ml) and incubated for 24 h at 4 °C. To test restimulation induced cell death, the plate is washed with medium and then cells were plated at concentration of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in triplicate in RPMI-GlutaMAX medium in presence or absence of 1 μM inhibitor or equivalent volume of DMSO as a negative control. After 24 h incubation, live cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion method and cell death is expressed as % cell loss and calculated as:

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error mean (SEM) of three or more replicate experiments.

4.10. RICD assay for SAP silenced T cells

Activated human PBLs were transfected with 200 pmol of siRNA oligonucleotides specific for the target protein (Stealth Select siRNA; Life Technologies) or a non-specific control oligo (Life Technologies). Transient transfections were performed using Amaxa nucleofector kits for human T cells (Lonza) and the Amaxa Nucleofector II or 4D systems (programs T-20 or EI-115). Cells were cultured in IL-2 (100 IU/ml) for 4 days to allow target gene knockdown. Knockdown efficiency was periodically evaluated by RT-PCR and Western blotting.

Non-specific Stealth RNAi Negative Control Duplexes (12935–300, Life Technologies) were used as a negative control. Sense strand UGUACUGCCUAUGUGUGCUGUAUCA Antisense strand UGAUACAGCAGACAUAGGCAGUACA.

To test restimulation induced cell death, activated T cells (105 cells/well) were plated in triplicate in 96-well round-bottom plate and treated with anti-CD3 (clone OKT3) (1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 ng/ml) in RPMI-GlutaMAX supplemented with 100 IU/ml rhIL-2 for 24 h. In these assays inhibitors (1, 5,10 μM) were added 30 min before the restimulation with OKT3. 24 h after treatment, cells were stained with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide and collected for a constant time of 30 s per sample on a FACScan flow cytometer (FACScaliber or Accuri C6, BD) or Attune Nxt Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell death is expressed as % cell loss and calculated as:

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error mean (SEM).

4.11. Quantitative real-time PCR

Activated human PBLs were prepared and transfected as described above. The RNA concentration and purity were estimated by a spectrophotometric method using NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific). The RNA was retrotranscribed with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems) and cDNA quantified by real time PCR (ABI7900 Applied Biosystems) using GUSB as normalizer.

TaqMan gene expression assays were from Life Technologies: Hs00939627_m1 (glucuronidasi beta, GUSB), Hs00374226_m1 (NR4A1), Hs00545007_m1 (NR4A3).

4.12. Western blot analysis

To verify the expression of the DGKα in both MDCK cells transfected with OST-Vector and OST-DGKα, and SAP in Jurkat cells transfected with control-shRNA and SAP-shRNA, equal amounts of protein lysates were prepared using 1% NP40 lysis buffer comprising of 25 mM Hepes, 150 mM Nacl, 5mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 1% NP40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM orthovanadate along with protease inhibitors at PH 8.0. Proteins were separated on 12% or 15% SDS–PAGE gels and the resolved proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked by incubating with 3% (w/v) dried BSA for 1 h at room temperature. They were then incubated overnight with respective primary antibodies at 4°C with gentle agitation: for detecting DGKα we used anti-DGKα antibody from Abcam (Cam-bridge, UK) and anti-SAP (SH2D1A-D10G8) from Cell signaling (USA) diluted (1:500) in Tris-buffered saline with detergent Tween 20 (TBST) containing 3% (w/v) BSA. The membranes were then washed 4 times in TBS tween buffer with 15 min time interval. They were then incubated with alkaline HRP-conjugated rabbit or mouse secondary antibody (1:5000) from PerkinElmer (USA) diluted in TBST, for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. After four 15 min washes with TBST, the membranes were developed using the Western Chemiluminescence Substrate (PerkinElmer, USA).

4.13. Quantification and statistical analysis

Data for the screen on OST-DGKα homogenates are the mean of duplicates. The compounds showing inhibitory activity in this assay were tested >4 times and the mean ± SEM is reported.

To calculate IC50 values of active inhibitors, the inhibitor activity was measured at least three times at 0.1, 1.0, 10.0 and 100.0 μM concentration. Data were analysed using [inhibitor] vs. normalized response parameters with least square [ordinary] curve fitting method in GraphPad PRISM 7.0 software mentioning 95% confidence interval and IC50 values always greater than 0.0. Graph shows the mean ± SEM of inhibitor activity at the indicated concentration. In all the experiments the data were normalized with the controls.

Evaluation of in vitro assays across multiple treatments (RICD) were analysed by using one-way ANOVA (Figs. 6–8) and two-way ANOVA (Fig. 9) with multiple comparisons correction using GraphPad PRISM 7.0 software. Error bars are described in figure legends as ± SEM or ± SD where appropriate. A single, double and triple asterisk denotes significance of a p-value ≤0.05, ≤0.01 and ≤ 0.001 respectively in all experiments.

Fig. 6.

AMB639752 is DGKα specific. A, B, C) 293T cells were transfected with different DGK isoforms (A-DGKα, B– DGKζ, C– DGKθ respectively) or empty vectors and homogenized. AMB639752, R59022 and R59949 were tested at 100 μM for their capacity to inhibit the DGK activity of the different homogenates. Data are means ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by: Università del Piemonte Orientale, Fondazione Telethon (GGP16252, 2016), TIPSO grant from Regione Piemonte (PAR FSC 2007–2013 Asse I—Innovazione e transizione produttiva—Linea di azione 3: “Competitività industria e artigianato” linea d—Bando regionale sulle malattie Autoimmuni e Allergiche), Consorzio Interuniversitario di Biotecnologie (CIB).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.12.061.

References

- [1].Shulga YV, Topham MK, Epand RM, Regulation and functions of diacylglycerol kinases, Chem. Rev 111 (2011) 6186–6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mérida I, Avila-Flores A, Merino E, Diacylglycerol kinases: at the hub of cell signaling, Biochem. J 409 (2008) 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cai J, Abramovici H, Gee SH, Topham MK, Diacylglycerol kinases as sources of phosphatidic acid, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791 (2009) 942–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sakane F, Imai S, Kai M, Yasuda S, Kanoh H, Diacylglycerol kinases as emerging potential drug targets for a variety of diseases, Curr. Drug Targets 9 (2008) 626–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sakane F, Imai S, Kai M, Yasuda S, Kanoh H, Diacylglycerol kinases: why so many of them? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771 (2007) 793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bhat KP, Aldape K, Not expecting the unexpected: diacylglycerol kinase alpha as a cancer target, Cancer Discov 3 (2013) 726–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sakane F, Mizuno S, Komenoi S, Diacylglycerol kinases as emerging potential drug targets for a variety of diseases: an update, Front. Cell Dev. Biol 4 (2016) 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Krishna S, Zhong XP, Regulation of lipid signaling by diacylglycerol kinases during T cell development and function, Front. Immunol 4 (2013) 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Filipovich AH, Zhang K, Snow AL, Marsh RA, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndromes: brothers or distant cousins? Blood 116 (2010) 3398–3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Purtilo DT, DeFlorio D, Hutt LM, Bhawan J, Yang JP, Otto R, Edwards W, Variable phenotypic expression of an X-linked recessive lymphoproliferative syndrome, N. Engl. J. Med 297 (1977) 1077–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pasquier B, Yin L, Fondanàche MC, Relouzat F, Bloch-Queyrat C, Lambert N, Fischer A, et al. , Defective NKT cell development in mice and humans lacking the adapter SAP, the X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome gene product, J. Exp. Med 201 (2005) 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dupré L, Andolfi G, Tangye SG, Clementi R, Locatelli F, Aricà M, Aiuti A, et al. , SAP controls the cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells against EBV-infected cells, Blood 105 (2005) 4383–4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ma CS, Hare NJ, Nichols KE, Dupré L, Andolfi G, Roncarolo MG, Adelstein S, et al. , Impaired humoral immunity in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease is associated with defective IL-10 production by CD4+ T cells, J. Clin. Invest 115 (2005) 1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Snow AL, Marsh RA, Krummey SM, Roehrs P, Young LR, Zhang K, van Hoff J, et al. , Restimulation-induced apoptosis of T cells is impaired in patients with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease caused by SAP deficiency, J. Clin. Invest 119 (2009) 2976–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Baldanzi G, Pighini A, Bettio V, Rainero E, Traini S, Chianale F, Porporato PE, et al. , SAP-mediated inhibition of diacylglycerol kinase a regulates TCR-induced diacylglycerol signaling, J. Immunol 187 (2011) 5941–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ruffo E, Malacarne V, Larsen SE, Das R, Patrussi L, Wülfing C, Biskup C, et al. , Inhibition of diacylglycerol kinase a restores restimulation-induced cell death and reduces immunopathology in XLP-1, Sci. Transl. Med 8 (2016), 321ra327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].de Chaffoy de Courcelles DC, Roevens P, Van Belle H, R 59 022, a diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor. Its effect on diacylglycerol and thrombin-induced C kinase activation in the intact platelet, J. Biol. Chem 260 (1985) 15762–15770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Chaffoy de Courcelles D, Roevens P, Van Belle H, Kennis L, Somers Y, De Clerck F, The role of endogenously formed diacylglycerol in the propagation and termination of platelet activation. A biochemical and functional analysis using the novel diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor, R 59 949, J. Biol. Chem 264 (1989) 3274–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sato M, Liu K, Sasaki S, Kunii N, Sakai H, Mizuno H, Saga H, et al. , Evalu-ations of the selectivities of the diacylglycerol kinase inhibitors r59022 and r59949 among diacylglycerol kinase isozymes using a new non-radioactive assay method, Pharmacology 92 (2013) 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jiang Y, Sakane F, Kanoh H, Walsh JP, Selectivity of the diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor 3-[2-(4-[bis-(4-fluorophenyl)methylene]-1-piperidinyl)ethyl]-2,3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)quinazolinone (R59949) among diacylglycerol kinase subtypes, Biochem. Pharmacol 59 (2000) 763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dominguez CL, Floyd DH, Xiao A, Mullins GR, Kefas BA, Xin W, Yacur MN, et al. , Diacylglycerol kinase a is a critical signaling node and novel therapeutic target in glioblastoma and other cancers, Cancer Discov 3 (2013) 782–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Boroda S, Niccum M, Raje V, Purow BW, Harris TE, Dual activities of ritanserin and R59022 as DGKα inhibitors and serotonin receptor antagonists, Biochem. Pharmacol 123 (2017) 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McCloud RL, Franks CE, Campbell ST, Purow BW, Harris TE, Hsu KL, Deconstructing lipid kinase inhibitors by chemical proteomics, Biochemistry 57 (2018) 231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Franks CE, Campbell ST, Purow BW, Harris TE, Hsu KL, The ligand binding landscape of diacylglycerol kinases, Cell Chem. Biol 24 (2017) 870–880, e875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Akhondzadeh S, Malek-Hosseini M, Ghoreishi A, Raznahan M, Rezazadeh SA, Effect of ritanserin, a 5HT2A/2C antagonist, on negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study, Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32 (2008) 1879–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bishop WR, Ganong BR, Bell RM, Attenuation of sn-1,2-diacylglycerol second messengers by diacylglycerol kinase. Inhibition by diacylglycerol analogs in vitro and in human platelets, J. Biol. Chem 261 (1986) 6993–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nasmith P, Grinstein S, Diacylglycerol kinase inhibitors R59022 and dioctanoylethylene glycol potentiate the respiratory burst of neutrophils by raising cytosolic Ca2þ, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 161 (1989) 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Redman C, Lefevre J, MacDonald ML, Inhibition of diacylglycerol kinase by the antitumor agent calphostin C. Evidence for similarity between the active site of diacylglycerol kinase and the regulatory site of protein kinase C, Bio-chem. Pharmacol 50 (1995) 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coloén-Gonzaélez F, Kazanietz MG, C1 domains exposed: from diacylglycerol binding to protein-protein interactions, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761 (2006) 827–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu K, Kunii N, Sakuma M, Yamaki A, Mizuno S, Sato M, Sakai H, et al. , A novel diacylglycerol kinase a-selective inhibitor, CU-3, induces cancer cell apoptosis and enhances immune response, J. Lipid Res 57 (2016) 368–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hawkins PC, Nicholls A, Conformer generation with OMEGA: learning from the data set and the analysis of failures, J. Chem. Inf. Model 52 (2012) 2919–2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hawkins PC, Skillman AG, Nicholls A, Comparison of shape-matching and docking as virtual screening tools, J. Med. Chem 50 (2007) 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Muchmore SW, Souers AJ, Akritopoulou-Zanze I, The use of three-dimensional shape and electrostatic similarity searching in the identification of a melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 1 antagonist, Chem. Biol. Drug Des 67 (2006) 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Baldanzi G, Cutrupi S, Chianale F, Gnocchi V, Rainero E, Porporato P, Filigheddu N, et al. , Diacylglycerol kinase-alpha phosphorylation by Src on Y335 is required for activation, membrane recruitment and Hgf-induced cell motility, Oncogene 27 (2008) 942–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Talmon M, Rossi S, Pastore A, Cattaneo CI, Brunelleschi S, Fresu LG, Vortioxetine exerts anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects on human monocytes/macrophages, Br. J. Pharmacol 175 (2018) 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dhein J, Walczak H, Bäumler C, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Autocrine T-cell suicide mediated by APO-1/(Fas/CD95), Nature 373 (1995) 438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Aoudjit F, Vuori K, Engagement of the alpha2beta1 integrin inhibits Fas ligand expression and activation-induced cell death in T cells in a focal adhesion kinase-dependent manner, Blood 95 (2000) 2044–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rainero E, Cianflone C, Porporato PE, Chianale F, Malacarne V, Bettio V, Ruffo E, et al. , The diacylglycerol kinase a/atypical PKC/β1 integrin pathway in SDF-1a mammary carcinoma invasiveness, PLoS One 9 (2014), e97144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A, Han L, et al. , PubChem substance and compound databases, Nucleic Acids Res 44 (2016) D1202–D1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG, ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology, J. Chem. Inf. Model 52 (2012) 1757–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shoichet Irwin ZINC -a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening, J. Chem. Inf. Model (2005) 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hawkins PC, Skillman AG, Warren GL, Ellingson BA, Stahl MT, Conformer generation with OMEGA: algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database, J. Chem. Inf. Model 50 (2010) 572–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.