Abstract

Background

Antithyroid drugs are widely used in the therapy of hyperthyroidism. There are wide variations in the dose, regimen or duration of treatment used by health professionals.

Objectives

To assess the effects of dose, regimen and duration of antithyroid drug therapy for Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Search methods

We searched seven databases and reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials of antithyroid medication for Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias. Pooling of data for primary outcomes, and select exploratory analyses were undertaken.

Main results

Twenty‐six randomised trials involving 3388 participants were included. Overall the quality of trials, as reported, was poor. None of the studies investigated incidence of hypothyroidism, changes in weight, health‐related quality of life, ophthalmopathy progression or economic outcomes. Four trials examined the effect of duration of therapy on relapse rates, and when using the titration regimen 12 months was superior to six months, but there was no benefit in extending treatment beyond 18 months. Twelve trials examined the effect of block‐replace versus titration block‐regimens. The relapse rates were similar in both groups at 51% in the block‐replace group and 54% in the titration block‐group (OR 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68 to1.08) though adverse effects (rashes (10% versus 6%) and withdrawing due to side effects (16% versus 9%)) were significantly higher in the block‐replace group. Three studies considered the addition of thyroxine with continued low dose antithyroid therapy after initial therapy with antithyroid drugs. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies and the difference between the two groups was not significant (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.05 to 6.21). Four studies considered the addition of thyroxine alone after initial therapy with antithyroid drugs. There was no significant difference in the relapse rates between the groups after 12 months follow‐up (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.67). Two studies considered the addition of immunosuppressive agents. The results which were in favour of the interventions would need to be validated in other populations.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence suggests that the optimal duration of antithyroid drug therapy for the titration regimen is 12 to 18 months. The titration (low dose) regimen had fewer adverse effects than the block‐replace (high dose) regimen and was no less effective. Continued thyroxine treatment following initial antithyroid therapy does not appear to provide any benefit in terms of recurrence of hyperthyroidism. Immunosuppressive therapies need further evaluation.

Plain language summary

Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves' hyperthyroidism

People who have Graves' hyperthyroidism have thyroid glands which are releasing too much thyroid hormone. This can cause goitres (swelling in the neck around the thyroid gland), sweating, bowel or menstrual problems, and other, especially eye symptoms (ophthalmopathy). Treatments include anti‐thyroid drugs, surgery or radiation to reduce thyroid tissue. There are several choices to be made when considering the drug treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism including the choice of drug, dose, duration of therapy, addition of thyroid hormone (thyroxine) and when to discontinue therapy. The antithyroid drugs which were used in the included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comprised carbimazole, propylthiouracil and methimazole.

Twenty‐six RCTs involving 3388 participants were identified. The majority of participants in all the studies were female (83% in the studies reporting sex distribution). The mean age was 40 years. The duration of follow up was between two to five years in eleven trials. In high dose ('block‐replace') versus low dose ('titration') studies the duration of therapy was six months in two studies, 18 months in four studies and 12 months in the remaining trials.

The main outcome was the relapse rate of hyperthyroidism over one year after completion of drug treatment and this was the primary outcome in all the studies assessed. There were no deaths reported in any of the studies. None of the studies detailed incidence of hypothyroidism, changes in weight during the course of therapy, health‐related quality of life, ophthalmopathy progression or economic outcomes. The evidence (based on four studies) suggests that the optimal duration of antithyroid drug therapy for the low dose regimen is 12 to 18 months. The low dose regimen had fewer adverse effects than the high dose regimen and was no less effective in trials (based on 12 trials) of equal duration. Continued thyroxine treatment following initial antithyroid therapy does not appear to provide any benefit in terms of recurrence of hyperthyroidism. Studies using immunosuppressive agents need further validation of safety and efficacy in controlled trials among different populations.

Data regarding side effects and number of participants withdrawn from therapy due to side effects were available in seven studies. The number of participants reporting rashes was significantly higher in the high versus low dose group (10% versus 6%). The number of participants withdrawing due to side effects were also significantly higher in the high versus low dose group (16% versus 9%).

Background

Description of the condition

Hyperthyroidism is a condition in which the thyroid gland produces too much thyroid hormone (thyroxine,T4; triiodothyronine, T3). This is associated with a low thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH or thyrotropin, which is secreted by the pituitary gland and regulates secretion of the thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland) level as too much thyroid hormone will reduce the amount of TSH produced by the pituitary gland. Hyperthyroidism is common and affects approximately 2% of women and 0.2% of men. The most common cause of hyperthyroidism is Graves' disease (Franklyn 1994). Graves' disease results from an interaction between genetic background (heredity), environmental factors and the immune system. For reasons that are not fully understood, the immune system produces an antibody (for example thyroid stimulating hormone (or thyrotropin) receptor antibody) that stimulates the thyroid gland to produce too much thyroid hormone. This is most common in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years, but can occur at any age in either sex. When Graves' disease occurs, the thyroid gland enlarges (called a goitre) and makes more and more thyroid hormone, resulting in symptoms such as weight loss, heat intolerance, irritability, anxiety, palpitations and tremors. Some people also develop eye problems (called Graves' ophthalmopathy), such as dry, irritated, prominent or red eyes, and double vision. Thickening of the skin of the lower legs is noted by some patients (pretibial myxoedema). Thyroid scanning (scintigraphy) with one of the radioisotopes of iodine or technetium‐99m pertechnetate is an additional test which may be done, and, in Graves' hyperthyroidism there is a diffuse increase in the thyroid gland uptake.

Description of the intervention

The large published literature on the management of Graves' hyperthyroidism reflects the persisting controversies regarding best management of this common condition. There are three recognised treatment options for hyperthyroidism: antithyroid drugs, surgery and radioiodine. The use of radioiodine as a first‐line therapy for hyperthyroidism is growing. It is well tolerated, with the only common long‐term complication being the risk of developing radioiodine‐induced hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland). Surgery, either subtotal or near‐total thyroidectomy, has limited but specific roles to play in the treatment of hyperthyroidism: this approach is rarely used in patients with Graves' disease unless patients have declined radioiodine treatment or there is a large goitre causing symptoms of compression in the neck.

Adverse effects of the intervention

Up to 15% of people who take an antithyroid drug have minor side effects including itching, rash, hives, joint pain and swelling, fever, altered taste sensation, nausea, and vomiting. The major side effects like agranulocytosis (fall in white cell blood count), liver damage and vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels) are fortunately very rare. Other medications which have antithyroid activity include lithium and perchlorate but their use is limited in the primary drug treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism due to their toxicity. Non‐specific Immunosuppressive drug treatments have also been tried for the treatment of Graves' disease.

All three treatments for Graves' disease have their advantages and disadvantages. Absolute contraindications for each treatment are few.

How the intervention might work

Methimazole, carbimazole, and propylthiouracil are the mainstays of antithyroid‐drug therapy. These drugs block the synthesis of thyroid hormone by the thyroid gland (Cooper 2005). They may also help control the disease by indirectly affecting the immune system. Propylthiouracil also inhibits the peripheral conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine. Methimazole is the active metabolite of carbimazole, and since the conversion of carbimazole to methimazole in the body is virtually complete, their effects and equivalent doses are thought to be comparable. Antithyroid drug therapy can be given either by the block‐replace regimen (where a higher dose of antithyroid drug is used to block hormone production with a replacement dose of thyroxine) or by a titration block‐regimen (where the antithyroid drug dose is reduced by titrating treatment against serum thyroxine concentrations).

Why it is important to do this review

Several randomised controlled trials of antithyroid therapies have been reviewed by Leech (Leech 1998). This non‐systematic review highlighted the controversies in the management of Graves' disease. The review discussed four prospective randomised controlled trials comparing relapse rates in block‐replace and titration block‐regimes (Edmonds 1994; Jorde 1995; Lucas 1997; Rittmaster 1998) and two prospective randomised controlled trials looking at the duration of antithyroid therapy (Allannic 1990; Weetman 1994). The preferred regimen and duration of therapy remain unresolved with various centres treating from between six to 24 months with either the block‐replace or the titration block‐regimen chosen on variable criteria. There have been no previous systematic reviews performed in this area.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antithyroid drug regimen and duration in the therapy of Graves' hyperthyroidism. We compared antithyroid drug use with the block‐replace and the titration block‐regime and also looked at studies comparing duration of therapy using either of these regimes. In addition we planned to review any studies directly comparing antithyroid drugs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Quasi‐randomised studies were included and also analysed separately in a sensitivity analysis. The minimum duration of the intervention needed to be six months and the minimum duration of follow up needed to be one year from completion of therapy to assess the outcomes of relapse (recurrence of hyperthyroidism) and hypothyroidism.

Types of participants

Groups of study participants included all age groups receiving antithyroid treatment for Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Diagnostic criteria

Graves' disease as the cause of the hyperthyroidism was defined by the presence of diffuse goitre, extrathyroidal signs (ophthalmopathy or pretibial myxoedema), detectable thyroid antibodies or diffuse increased uptake of radioiodine on a thyroid scan. Patients with a nodular thyroid either by palpation or on thyroid scans were excluded, as these patients are unlikely to have Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Interventions were those used in the antithyroid drug therapy (carbimazole, propylthiouracil, methimazole, immunosuppressive therapy) of Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Control

The comparison interventions were: Block‐replace and titration block‐regimes.

In addition the following comparisons were also evaluated:

short‐term (six months) versus long‐term (over 12 months) block‐replace regimen;

short‐term (six months) versus long‐term (over 12 months) titration block‐regimen;

high dose (equivalent to 40 mg carbimazole or more) versus low dose (equivalent to 30 mg carbimazole or less) block‐replace regimen;

carbimazole, methimazole, propylthiouracil, perchlorate or lithium comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

relapse rates (recurrence of hyperthyroidism) at least one year after completion of drug treatment;

incidence of hypothyroidism;

mortality.

Secondary outcomes

course of ophthalmopathy (need for corticosteroids, radiotherapy, visual compromise);

adverse effects (agranulocytosis, drug rash, hepatitis, vasculitis);

symptoms of hyperthyroidism (anxiety, tachycardia, heat intolerance, diarrhoea, oligomenorrhoea);

thyroid antibody status;

weight change;

frequency of outpatient visits and thyroid function tests;

health‐related quality of life;

economic outcomes;

compliance rates (for example by pharmacy prescription calculations, pill counts);

necessity to use alternative treatment methods (surgery or radioiodine).

Timing of outcome measurement

Medium term outcome assessment: less than a year, long‐term outcome assessment: more than a year.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used the following sources for the identification of trials:

The Cochrane Library (issue 1, 2009);

MEDLINE (until April 2009);

EMBASE (until April 2009);

BIOSIS (until April 2009);

CINAHL (until July 2004);

HEALTHSTAR (until June 2002).

In MEDLINE, the first two levels of the standard Cochrane search strategy for randomised and clinical controlled trials, based on that previously described (Dickersin 1994), were combined to identify antithyroid drug use in patients.

Ongoing trials:

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com) National Research Register) and the National Institutes of Health (www.ClinicalTrials.gov).

For a detailed MEDLINE search strategy please see under Appendix 1, the search strategies for the other databases were adapted.

Searching other resources

The references of all retrieved studies and reviews were searched for additional trials. Books relating to thyroid disease were searched. Authors of published trials, colleagues and the British and European Thyroid Associations were contacted.

No language restriction was applied to eligible reports.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently assessed titles and abstracts of studies identified through the searches. Full articles were retrieved for further assessment if the information given suggested that the study:

included patients receiving antithyroid drug treatment for Graves' hyperthyroidism;

graves' hyperthyroidism had been adequately defined;

used random allocation to the comparison groups.

If there was any doubt regarding these criteria from the information given in the title and abstract, the full article was retrieved for clarification. Where differences in opinion existed, they were resolved by a third party (JSB). If resolving disagreement was not possible, the article was added to those 'awaiting assessment' and the authors were contacted for clarification.

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled inclusion criteria, two authors out of a panel of four independently abstracted relevant population and intervention characteristics using standard data extraction templates (for details see Characteristics of included studies) with any disagreements resolved by discussion, or if required by a third party. Any relevant missing information on the trial was sought from the original author(s) of the article, if required.

Two authors out of a panel of four independently extracted the data. Data extraction included:

1. General information: published/unpublished, title, authors, reference/source, contact address, country, urban/rural etc., language of publication, year of publication, duplicate publications, sponsoring, setting. 2. Trial characteristics: design, duration, randomisation (and method), allocation concealment (and method), blinding (patients, people administering treatment, outcome assessors). 3. Intervention(s): placebo included, interventions(s) (dose, route, timing), comparison intervention(s) (dose, route, timing), co‐medication(s) (dose, route, timing). 4. Patients: sampling (random/convenience), exclusion criteria, total number and number in comparison groups, sex, age, diagnostic criteria, duration of hyperthyroidism, similarity of groups at baseline (including any co‐morbidity), assessment of compliance, withdrawals/losses to follow‐up (reasons/description), subgroups. 5. Outcomes: outcomes specified above (also: what was the main outcome assessed in the study?), any other outcomes assessed, other events, length of follow‐up, quality of reporting of outcomes. 6. Results: for outcomes and times of assessment (including a measure of variation), if necessary converted to measures of effect specified below; intention‐to‐treat analysis.

If any data were missing in a published report, trialists were contacted for further information. Six trialists were contacted and four responded.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors out of a panel of four assessed each trial independently. Possible disagreement were resolved by consensus, or with consultation of a third party in case of disagreement. Interrater agreement for key bias indicators (e.g. allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data) were calculated using the kappa statistic (Cohen 1960). In cases of disagreement, the rest of the group was consulted and a judgement was made based on consensus.

Methodological quality was independently assessed by two authors out of a panel of four (PA (assessed all trials), using a subject‐specific modification of the generic evaluation tool used previously by the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group. A sensitivity analysis was carried out based on the quality assessment. The assessment protocol scored each item between 0 and 2 as described below. In addition, risk of pre‐allocation disclosure of assignment was rated A (adequate), B (unclear), C (inadequate) or D (not used). The following aspects of internal and external validity were reported and assessed:

a. Was the assigned treatment adequately concealed prior to allocation? 2 = method did not allow disclosure of assignment (A) 1 = chance of disclosure of assignment or states random but no description (B) 0 = quasi‐randomised (C)

b. Were the outcomes of patients who withdrew included in the analysis (intention‐to‐treat)? 2 = intention‐to‐treat analysis based on all cases randomised possible or carried out 1 = states number and reasons for withdrawal but intention‐to‐treat analysis not possible, e.g. because outcomes were not measured 0 = not mentioned or not possible

c. Were the outcome assessors blinded to treatment status? 2 = action taken to blind assessors, or outcomes such that bias was unlikely 1 = chance of unblinding of assessors 0 = not mentioned

d. Were the treatment and control group comparable at entry? 2 = good comparability of groups, or confounding adjusted for in analysis 1 = confounding possible, mentioned but not adjusted for 0 = large potential for confounding, or not discussed

e. Were care programmes, other than the trial options, identical? 2 = care programmes identical 1 = differences in care programmes but unlikely to influence study outcomes 0 = not mentioned or differences in care programmes likely to influence study outcomes

f. Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined? 2 = clearly defined 1 = inadequately defined 0 = not defined

g. Were the interventions clearly defined? 2 = clearly defined interventions were applied with a standardised protocol 1 = clearly defined interventions were applied but the application protocol was not standardised 0 = intervention and/or application protocol were poorly or not defined

h. Were the participants blind to assignment status following allocation? 2 = effective action taken to blind subjects 1 = small or moderate chance of unblinding subjects 0 = not mentioned (unless double‐blind), or not done

i. Were the treatment providers blind to assignment status? 2 = effective action taken to blind treatment providers 1 = small or moderate chance of unblinding of treatment providers 0 = not mentioned (unless double‐blind), or not done

j. Was follow‐up active and appropriate? 2 = optimal (mortality + relapse + hypothyroidism) 1 = adequate 0 = not defined, or not adequate

k. Was follow‐up active and appropriate? Was the overall duration of surveillance clinically appropriate? 2 = optimal (24 months or more) 1 = adequate (12 to 24 months) 0 = not defined, or not adequate

We took into account the different components of quality assessment (specifically focusing on allocation concealment) in a sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data were expressed as odds ratio, no continuous data were available.

Dealing with missing data

In the case of duplicate publications of the study, we tried to maximise the information yielded and in case of doubt the original publication obtained priority. Authors were contacted to clarify any data queries and to supply missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of the forest plots and quantification of heterogeneity was examined using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003) . I2 demonstrates the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity and values of I2 greater than 50% indicate substantial heterogeneity. Random effects models were used when I2 was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

The authors assessed the publications for any reporting bias. This included checking for reports which have been reported in conference abstracts and not been reported in publications.

Data synthesis

Data were combined for meta‐analysis for dichotomous variables relapse rates and number of patients with complications. For each study Peto odds ratio and 95% confidence limits were calculated, the results were combined using fixed‐effect models and presented with 95% confidence limits (CI).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was planned to be carried out if there would have been a significant effect for one of the main outcome measures.

duration of treatment: over or less than one year;

dose of antithyroid drug: Block‐replace (high) (equivalent of 40 mg dose of carbimazole) or titration block‐(low) dose;

presence or absence of thyroid antibodies;

smoker or non‐smoker;

male or female sex;

size of goitre;

age over or under 15 years (children);

previous antithyroid treatment or no previous antithyroid treatment.

There were sufficient data available to do a subgroup analysis only for the first two subgroups (duration of therapy and dose). None of the studies involved children.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies;

repeating the analysis taking into account of study quality, as specified above;

repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominated the results.

repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other) and country.

Results

Description of studies

The publication dates of the trials span 18 years, Allannic 1990 being the earliest. Trials were conducted in 16 countries. There were two multicenter trials involving more than one country (Benker 1998; Hoermann 2002), with the largest trial being an European Multicentre trial involving six countries (Benker 1998). There were three multicenter studies involving single countries based in Belgium (Glinoer 2001), France (Leclere 1994) and Norway (Nedrebo 2002). There were four studies from the UK (Edmonds 1994; McIver B 1996; Weetman 1994; Wilson 1996), three from Spain (Garcia‐Mayor 1992; Goni Iriarte 1995; Lucas 1997), three from France (Allannic 1990; Leclere 1994; Maugendre 1999), two from Norway (Jorde 1995; Nedrebo 2002) and single trials from Austria (Raber 2000), Belgium (Glinoer 2001), Germany (Pfeilschifter 1997), Greece (Mastorakos 2003) Turkey (Tuncel 2000) and Poland(Huszno 2004). There were six trials outside the European Union, with one from Japan (Hashizume 1991), one from Korea (Cho 1992), one from New Zealand (Grebe 1998), one from Canada (Rittmaster 1998), one from Brazil (Peixoto 2006) and one from China (Chen 2008).

The 26 included studies involved a total of 3388 participants. Details of individual studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies. The majority of participants in all the studies were female (83%, 2320 out of 2807 in the studies reporting sex distribution). The mean age was 40 years.

Studies considering the duration of therapy

Four studies (Allannic 1990; Garcia‐Mayor 1992; Maugendre 1999; Weetman 1994) involving 445 participants looked at the effect of duration of therapy on recurrence of hyperthyroidism. Two of them considered six month therapy versus 12 to 18 month therapy using either the titration block‐regimen (Allannic 1990) or the block‐replace regimen (Weetman 1994). Two of them used the titration block‐regimen but considered even longer durations of therapy of up to 24 months (Garcia‐Mayor 1992) or 42 months (Maugendre 1999).

Studies considering the addition of thyroxine

The addition of thyroxine was approached in a number of different ways in 19 studies involving 2670 participants.

Block‐replace (high dose) versus titration (low dose) regimens

Twelve studies approached this in the block‐replace manner and 12 to 24 month follow up was available in five of them (Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995; McIver B 1996; Wilson 1996). Longer follow up of between two to five years was available in six studies (Benker 1998; Goni Iriarte 1995; Leclere 1994; Lucas 1997; Nedrebo 2002; Rittmaster 1998). All these studies used initial high doses of antithyroid drugs which were titrated down in the titration block‐groups except for Benker 1998 where the low dose group was maintained on methimazole 10 mg per day from the beginning. Thyroxine was added to some patients in the low dose (titration block‐) group to maintain euthyroidism for the duration of treatment. One of the studies (Tuncel 2000) was only reported in abstract form and the dose of antithyroid medication is not clear.

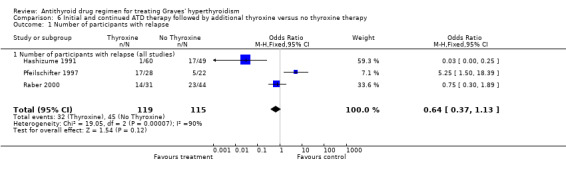

Combined thyroxine and antithyroid drug usage after initial antithyroid therapy

Three studies (Hashizume 1991; Pfeilschifter 1997; Raber 2000) had an initial period (six to nine months) of antithyroid therapy prior to randomisation into groups having low or moderate doses of antithyroid medication with or without additional thyroxine. One of the studies (Hashizume 1991) continued thyroxine for a further three years after methimazole was stopped.

Thyroxine alone after initial antithyroid drug therapy

Three studies (Glinoer 2001; Hoermann 2002; Mastorakos 2003) completed a course of antithyroid medication for 12 to 18 months prior to randomisation into two groups to receive either thyroxine or no therapy. Mastorakos 2003 had a third group on liothyronine. One study (Nedrebo 2002) had a factorial randomisation such that following a period of antithyroid drugs one group continued thyroxine for one year and the second group had no therapy after antithyroid medications.

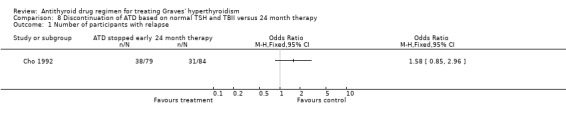

Study considering discontinuation of antithyroid medication based on thyroid function and antibodies

One study (Cho 1992) randomised the participants into two groups with different criteria for discontinuing antithyroid medication, one group used standard titration block‐therapy of antithyroid medication for 24 months while the other group discontinued therapy once the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyrotropin binding inhibitor immunoglobulin (TBII) concentrations were negative on two occasions.

Studies considering immunosuppressive therapies

One study (Huszno 2004) involving 64 participants considered the addition of azathioprine to antithyroid medication. One group used azathioprine 1 to 2 mg/kg per day reduced to a maintenance dose of 12.5 mg/day along with methimazole while the other group was given methimazole alone starting with 60mg/day titrated down to a maintenance of 5 mg/day. A further study from China (Chen 2008) involving 154 participants used a compound antithyroid ointment containing methimazole 12mg and hydrocortisone 0.6mg rubbed over thyroid three times a day until thyroid hormones normalised and then daily maintenance dose at bedtime. The control group had methimazole 37.5 mg daily divided dose three times daily initially until thyroid hormones normalised and then had a maintenance dose given once daily at bedtime.

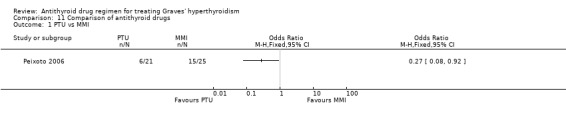

Studies comparing antithyroid drugs

Most of the studies comparing antithyroid drugs (Homsanit 2001; Kallner 1996; Nicholas 1995) looked only at the initial response of the thyrotoxicosis with in the first 3 to 6 months. Only one study (Peixoto 2006) involving 55 participants looked at relapse rates at one year follow up. This study compared the relapse rates in Graves' disease and looked at the side effect profiles.

Results of the search

Of the 5175 study reports initially retrieved by the search strategies, 55 studies were retrieved for further assessment. Twenty one trials were identified by both the MEDLINE and EMBASE search strategies, two further trials were identified each by MEDLINE and EMBASE. One trial's conference abstract (Tuncel 2000) was identified via BIOSIS.

Included studies

Twenty six studies were included in the review (three of these studies were reported in two or more publications and the later reports (Allannic 1990; Benker 1998; Glinoer 2001) were used for data abstraction. Of the 26 included studies, 23 were reported in English and one each in Spanish, French and Polish. Two of the French studies had been reported in English (Allannic 1990; Glinoer 2001) and one of the German trials had also been reported in English (Hoermann 2002) and the English version of these trials were included.

Excluded studies

The reasons for excluding the 26 studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies. The major reasons for exclusion of the studies included short term studies on the initial drug therapy of hyperthyroidism with no assessment of relapse rates or follow up greater than 12 months.

Risk of bias in included studies

Cohen's kappa (Cohen 1960) was calculated to measure interrater agreement with regard to study quality and this was 0.72 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63 to 0.81). Many of the trials failed to report trial methodology in sufficient detail to give top scores on individual items. Overall quality scores ranged from seven to 17 (maximum possible 20), with a mean score of 12. Assigned allocation (ac) categories and quality scores of the included trials are included in Appendix 2.

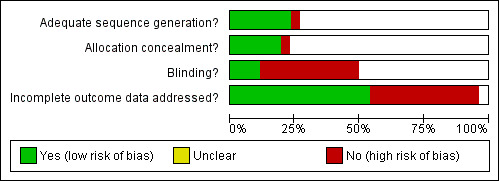

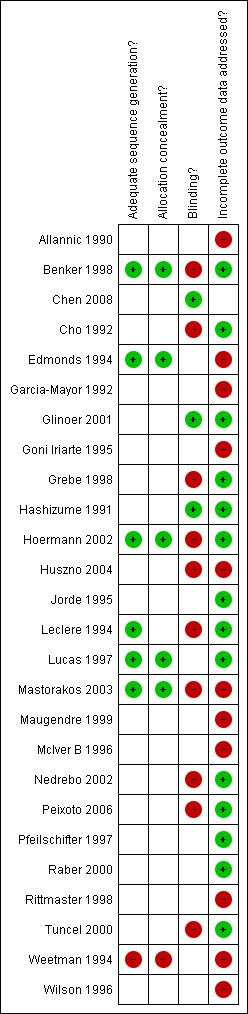

Risk of bias figures using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for risk of bias assessment may be inspected under Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Sealed envelopes were used for concealment of allocation (item a) in three trials (Benker 1998; Edmonds 1994; Lucas 1997) but there were inadequate details to be certain about the concealment. Allocation was unlikely to be concealed in one quasi‐randomised trial (Weetman 1994), where allocation was based on the last digit of the hospital number. Two studies (Hoermann 2002; Mastorakos 2003) used computer aided randomisation. One study (Leclere 1994) used statistical tables for randomisation. One study (Chen 2008) used random numbers table. The remaining trials gave no details of the randomisation process. One of the studies (Tuncel 2000) was a conference abstract with few details on methodological quality.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis was explicitly mentioned and carried out in three trials (Benker 1998; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995) and the reports of a further four trials (Glinoer 2001; Hashizume 1991; Lucas 1997; Raber 2000) suggested that they did not have any participants lost to follow‐up after randomisation. Intention to treat analysis was also possible in seven other trials (Cho 1992; Hoermann 2002; Leclere 1994; Nedrebo 2002; Peixoto 2006; Pfeilschifter 1997; Tuncel 2000)

Blinding

A placebo control was used for thyroxine replacement in three studies (Glinoer 2001; Hashizume 1991; Mastorakos 2003) and patient blinding was not attempted in any other trials. The treatment providers were reported as blinded in only one study (Glinoer 2001).

Incomplete outcome data

There was a large loss to follow‐up (27%) in the 12 trials considering the titration versus the block‐replace regimen. Additional analyses were done considering the possibility of all patients lost to follow‐up as having relapses. The true relapse rates would therefore fall between the reported relapse rates and the relapse rates considering this worst case scenario.

Selective reporting

Outcomes such as hypothyroidism were not reported in the trials. Other outcomes such as complications were not reported in some of the trials and attempts were made to contact the authors to seek additional information.

Other potential sources of bias

Comparability at baseline between the groups was often stated with no further details. In one study (Grebe 1998) goitre size was significantly larger in one of the groups and this was discussed. In two studies (Lucas 1997; Peixoto 2006) one of the groups had significantly more participants with positive thyroid antibodies and this was discussed in the text and analysis.

The care programmes were similar between the study groups. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were often not explicitly stated though the studies gave satisfactory descriptions of the diagnosis of Graves' disease participants included in the study. The interventions used were adequately defined in most of the studies, though there were insufficient details in three trials (Hashizume 1991; Lucas 1997; Rittmaster 1998).

Follow up was adequate in all studies with regard to the primary outcome of relapse of hyperthyroidism. The duration of follow up was between two to five years in eleven trials (Benker 1998; Chen 2008; Cho 1992; Garcia‐Mayor 1992; Hashizume 1991; Huszno 2004; Goni Iriarte 1995; Leclere 1994; Lucas 1997; Nedrebo 2002; Rittmaster 1998). All other trials had follow up of participants for between one to two years.

Effects of interventions

The main outcome as stated previously was the relapse rate of hyperthyroidism over one year after completion of drug treatment and this was the primary outcome in all the studies assessed. None of the studies mentioned incidence of hypothyroidism during the follow up period. There was no deaths reported in any of the studies. Overall study quality scores ranged from five to 17 (maximum possible 20), with a mean score of 13.

The additional outcomes sought were poorly documented in the review, though several of the studies did mention adverse effects of therapy (Benker 1998; Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995; McIver B 1996; Rittmaster 1998; Wilson 1996). None of the studies detailed changes in weight during the course of therapy, health related quality of life or economic outcomes. Compliance rates were discussed only in three studies (Benker 1998; Chen 2008; Peixoto 2006) .

The 26 randomised controlled studies looked at broadly seven slightly different variations in administering antithyroid drugs and these are listed below and the results will be presented according to these groupings: A. Four studies (Allannic 1990; Garcia‐Mayor 1992; Maugendre 1999; Weetman 1994) looked at the effect of duration of therapy on the relapse rates B. Twelve studies (Benker 1998; Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Goni Iriarte 1995; Jorde 1995; Lucas 1997; Leclere 1994; McIver B 1996; Nedrebo 2002; Rittmaster 1998; Tuncel 2000; Wilson 1996) looked at the effect of block‐replace versus the titration block‐regimen on the relapse rates of hyperthyroidism C. Three studies (Hashizume 1991; Pfeilschifter 1997; Raber 2000) used a titration block‐regimen of antithyroid drugs for six to nine months or until euthyroid before randomising into groups with addition of thyroxine to low dose antithyroid medication and in the case of one study (Hashizume 1991) continued thyroxine or placebo for a further three years, after antithyroid medication was stopped. D. Three studies (Glinoer 2001; Hoermann 2002; Mastorakos 2003) gave antithyroid drugs for 12 to 18 months and then randomised into two groups either receiving thyroxine or no treatment. Mastorakos 2003 had a third group on liothyronine. One study (Nedrebo 2002) had a factorial randomisation such that following a period of antithyroid drugs, one group continued thyroxine for one year and the second group had no therapy after antithyroid medications. E. One study (Cho 1992) randomised participants into two groups with different criteria for discontinuing antithyroid medications: 24 months or when thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyrotropin binding inhibitor immunoglobulin (TBII) concentrations normalised on two occasions.

F. Two studies looked at immunosuppressive therapies with one (Huszno 2004) using azathioprine and one study from China (Chen 2008) looking at a compound antithyroid ointment containing methimazole and hydrocortisone.

G. One study (Peixoto 2006) compared propylthiouracil and methimazole in terms of the remission and relapse rates as well as side effects.

The results are presented using relapse rates in participants who completed the study as well as assuming relapse of hyperthyroidism (where possible) in all participants lost to follow‐up.

Studies considering duration of therapy

Less than 12 months therapy

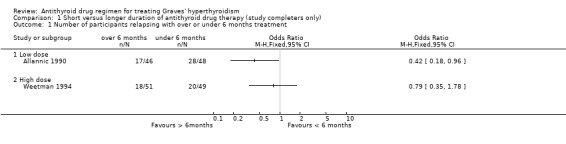

Two studies considered six months therapy versus 12 months (Weetman 1994) or 18 months (Allannic 1990). One of them (Weetman 1994) used the high dose block‐replace regimen using carbimazole 40 mg daily and the other study (Allannic 1990) used carbimazole in a titration block‐regimen. In Allannic 1990, the longer duration therapy (18 months) had significantly fewer relapses (37%; 17/46 vs 58%; 28/48) than the six month therapy (odds ratio (OR) 0.42, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.96). There were nine and 11 losses to follow up in the longer therapy duration and short therapy duration groups respectively and when analysis was carried out assuming relapsed hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs there was again a significant difference between the two groups, with relapse rates of 46% (26/57) in the longer therapy duration group and 68% (39/57) in the short therapy group (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.83). In the Weetman 1994 study, there was no significant difference between the six and 12 month (41%; 20/49 for six months vs 35%; 18/51 for 12 months) arms of the study. This was a quasi‐randomised study and the initial number of participants in the two groups were not available.

Over 12 months therapy

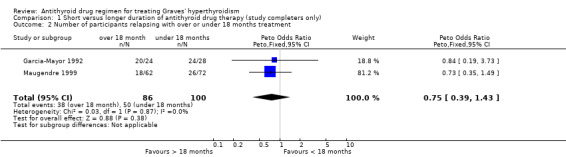

Two other studies used even longer durations of therapy with one study (Garcia‐Mayor 1992) comparing 12 months to 24 months and the other study (Maugendre 1999) comparing 18 months therapy with 42 months. The relapse rates in both studies were not associated with any significant difference between the groups and on combining the data showed a relapse rate of 44% (38/86) for the over 18 month therapy and 50% (50/100) for the under 18 months therapy (Peto OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.43). When the analysis was repeated assuming relapse of hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs the relapse rate was 56% (61/109) for the over 18 month therapy and 59% (72/122) for the under 18 months therapy (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.48).

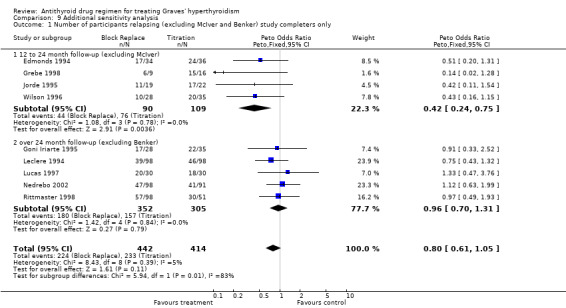

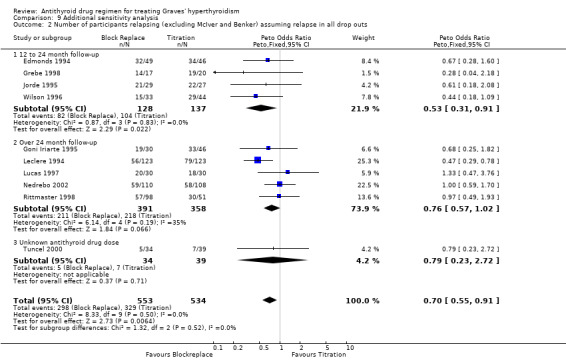

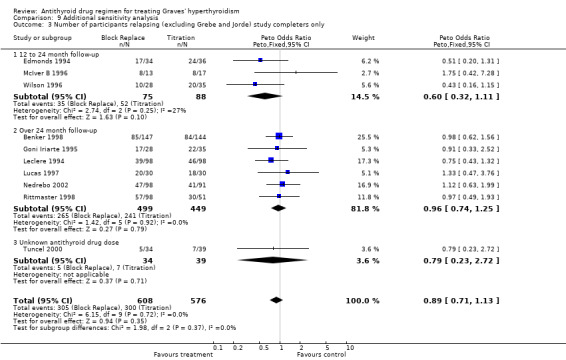

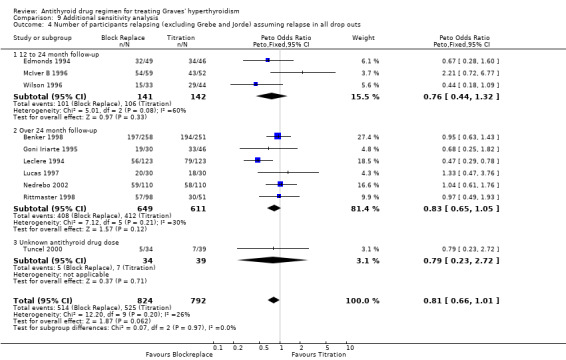

Block‐replace (high dose) versus titration (low dose) regimens

There were 12 studies included in the comparison between block‐replace versus titration block‐regimen in the medical therapy of Graves' hyperthyroidism. There was a total number of 1707 participants (870 in block‐replace, 837 in the titration block‐groups). Four hundred and forty three participants (30%, 443/1478) were lost to follow up (221 from block‐replace, 222 from titration block‐groups). Intention‐to‐treat analysis was explicitly mentioned in only three trials (Benker 1998; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995) but the numbers of participants lost to follow up were available in all but one trial (Rittmaster 1998), and therefore analysis with or without assuming all drop‐outs had relapse of hyperthyroidism was carried out in all the others.

The antithyroid drug used was carbimazole in eight of the studies (Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Goni Iriarte 1995; Lucas 1997; Leclere 1994; McIver B 1996; Nedrebo 2002; Wilson 1996). The dose of carbimazole ranged between 30 to 60 mg per day in the block‐replace arm of all these studies except Grebe 1998, where a dose of carbimazole 100 mg per day was used. Methimazole was used in three studies (Benker 1998; Jorde 1995; Rittmaster 1998) where doses of 30 to 60 mg per day were used in the block‐replace arm of the trials. Tuncel 2000 used either propylthiouracil or methimazole and the dose is uncertain.

The duration of therapy was six months in two studies (Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995), 18 months in four studies (Leclere 1994; Lucas 1997; McIver B 1996; Rittmaster 1998) and 12 months in the remaining trials (duration of therapy by Tuncel 2000 is unknown). A hypothesis generating sensitivity analysis showed that excluding the short duration studies did not have any effect on the overall results. A hypothesis generating sensitivity analysis excluding Tuncel 2000 (as this was unpublished and medication dose and duration was unknown) also did not have any effect on the overall results.

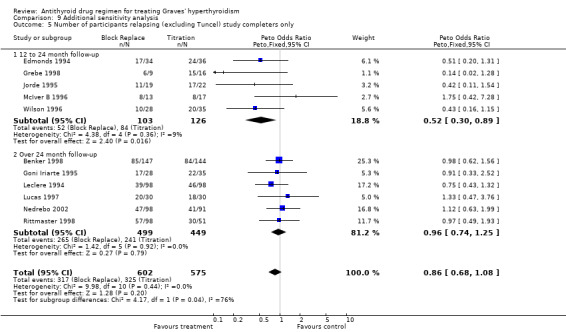

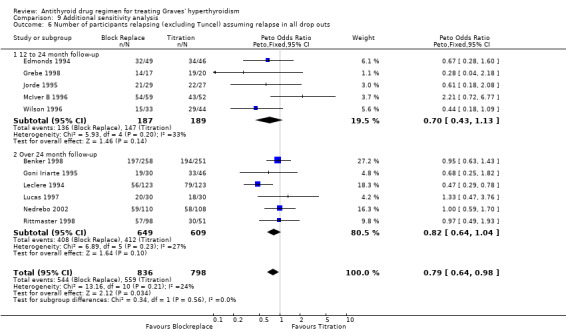

Five of the studies (Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995; McIver B 1996; Wilson 1996) had a 12 to 24 month follow‐up. The relapse rates were significantly better at 50% (52/103) in the block‐replace arm compared to 67% (84/126) in the titration block‐arm (Peto OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.89) when the losses to follow up are not considered. However there were 84 and 63 losses to follow up in the block‐replace and titration block‐groups respectively and when analysis was carried out assuming relapsed hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs the difference between the two groups, 73% (136/187) in the block‐replace group and 78% (147/189) in the titration block‐group was no longer statistically significant (Peto OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.13).

Six studies (Benker 1998; Goni Iriarte 1995; Leclere 1994; Lucas 1997; Nedrebo 2002; Rittmaster 1998) had follow up of between two to five years after completion of antithyroid drug treatment. The relapse rates were similar in both groups at 53% (265/499) in the block‐replace group and 54% (241/449) in the titration block‐group (Peto OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.25) when the losses to follow up are not considered. There were 150 and 160 losses to follow up in the block‐replace and titration block‐groups respectively and when analysis was carried out assuming relapsed hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs there was again no significant difference between the two groups, with relapse rates of 63% (408/649) in the block‐replace group and 68% (412/609) in the titration block‐group (Peto OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.04).

On combining the data of these 11 studies as well as Tuncel 2000 (with unknown dose and duration of therapy), the combined results were not associated with any significant difference between the groups. The relapse rates were similar in both groups at 51% (322/636) in the block‐replace group and 54% (332/614) in the titration block‐group (Peto OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.08) when the losses to follow up are not considered. There were 234 and 223 losses to follow‐up in the block‐replace and titration block‐groups respectively and when analysis was carried out assuming relapsed hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs there was a significant difference between the two groups, with relapse rates of 63% (549/870) in the block‐replace group and 68% (566/837) in the titration block‐group (Peto OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.98). Two of the studies had very large losses to follow up (Benker 1998 with 44% (222 out of 509 participants) and McIver B 1996 with 79% (81 out of 102)). A sensitivity analysis was done with exclusion of these studies (Benker 1998; McIver B 1996) and there was no major statistical effect on the overall results (Peto OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.03).

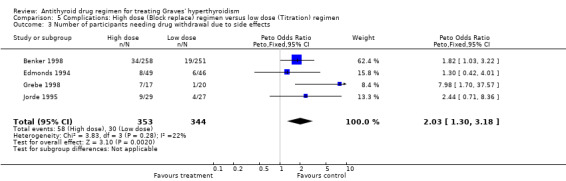

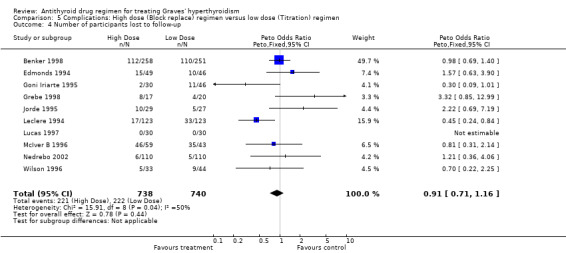

Adverse effects and drug withdrawal

Data regarding side effects and number of participants withdrawn from therapy due to side effects were available in seven studies (Benker 1998; Edmonds 1994; Grebe 1998; Jorde 1995; Leclere 1994; Nedrebo 2002; Wilson 1996). The number of participants reporting rashes was significantly higher in the block‐replace group (9.8%, 61 participants out of 619) as compared to the titration block‐group (5.8%, 36 participants out of 619) (Peto OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.69). This statistically significant difference was achieved even though the large study by Benker 1998 contributing over half of these participants did not show a significant difference in the incidence of drug rashes between the two groups (7%, 18 participants out of 258 in the high dose group and 6%, 15 participants out of 251 in the low dose group reporting a drug rash). The block‐replace group also had more participants with agranulocytosis (nine participants versus three) compared with the titration block‐group but this effect was not statistically significant. There was one report of agranulocytosis by Rittmaster 1998, but the treatment group was not mentioned. The number of participants withdrawing due to side effects were also significantly higher in the block‐replace group (16%, 58/353 participants in the block‐replace group compared to 9%, 30/344 in the titration block‐group; Peto OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.18).These differences are likely to be influenced by the fact that many of the patients may have experienced the side effects while they were on higher drug doses during the early phase of their titration block‐regimen. It is notable that the study by Grebe 1998 using the 100 mg dose of carbimazole had seven out of 17 participants in the block replace withdrawing due to side effects including two cases of agranulocytosis and five participants with rashes.

Combined thyroxine and antithyroid drug usage after initial antithyroid therapy

Three studies (Hashizume 1991; Pfeilschifter 1997; Raber 2000) used antithyroid drugs for six to nine months or until patients' euthyroidism was achieved before randomising to the addition of thyroxine to low dose antithyroid drugs (equivalent of carbimazole 10 mg per day). This combination was continued for six months in the study by Raber 2000, while the other two studies used the combination for 12 months. Hashizume 1991 continued the thyroxine therapy for a further 36 months after antithyroid drugs were stopped, while Pfeilschifter 1997 continued thyroxine for 12 months. On combining the data from these studies, the group with the addition of thyroxine had fewer relapses (27%, 32/119 versus 39%, 45/115). There was significant heterogeneity (P< 0.0001; I2 statistic 90%) among the studies with the result being largely influenced by the study by Hashizume 1991 where the relapses in the thyroxine group were less than 2% (1/60) as compared to 35% (17/49) in the placebo group. When a random‐effects model was used the differences between the two groups were no longer significant (OR 0.58, 95% CII 0.05 to 6.21). A sensitivity analysis with the exclusion of the Hashizume 1991 study also yielded no significant difference in the relapse rate between the thyroxine treated group (52%, 31 out of 59) versus the treatment group (42%, 28 out of 66) (Peto OR 1.55, 95% CI 0.73 to 3.14).

Thyroxine alone after initial antithyroid drug therapy

Three studies (Glinoer 2001; Hoermann 2002; Mastorakos 2003) gave antithyroid drugs for 12 to 18 months and then randomised into two groups either receiving thyroxine or no treatment. Mastorakos 2003 had a third group on liothyronine. One study (Hoermann 2002) randomised the thyroxine group further at the end of the first year into two groups either stopping or continuing thyroxine and only the results of the initial randomisation with results at the end of the first year were considered in the analysis. One study (Nedrebo 2002) had a factorial randomisation such that following a period of antithyroid drugs one group continued thyroxine for one year and the second group had no therapy after antithyroid medications. On combining the results of these four studies for thyroxine there was no statistically significant difference in the relapse rates between the two groups after 12 months of follow‐up with the rates being 31% (88/282) with thyroxine and 29% (82/284) with placebo (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.67). In the study by Mastorakos 2003 liothyronine also had no significant effect on relapse rates.

Discontinuation of antithyroid drugs based on normalised thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyrotropin binding inhibitor immunoglobulin (TBII)

Cho 1992 randomised 163 patients into two groups having different criteria for discontinuation of antithyroid medication; one group (group 1) discontinued therapy when TSH and thyrotropin binding inhibitor immunoglobulin (TBII) were normal on two occasions and the other group (group 2) had therapy for 24 months. Propylthiouracil was used in a titration regimen in both groups and the participants were followed up for a mean (range) period of 28 (18 to 40) months. The relapse rates of the two groups were 48% (38/79) in group 1 and 37% (31/84) in group 2 (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.96. The median duration of therapy in group 1 was 14 months shorter than in group 2 (mean follow up of 28 months).

Studies considering immunosuppressive therapies

Huszno 2004 considered the addition of azathioprine 1 to 2 mg/kg/day reduced to a maintenance dose of 12.5mg per day in addition to methimazole 60 mg day titrated down to 5 mg day. The duration of treatment was 8 to 14 months and the follow up was for up to five years. The relapse rates were 8% (3/36) in the azathioprine group compared to 54% (15/28) in the methimazole group (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.32). Five of the 28 patients in the methimazole group were treated with surgery as compared to one patient in the azathioprine group. The incidence of opthalmopathy was 7 in 28 patients in the methimazole group versus one patient in the azathioprine group. Chen 2008 used a a compound antithyroid ointment (CATO) containing methimazole 12 mg and hydrocortisone 0.6 mg rubbed over the thyroid three times a day until thyroid hormones normalised and then daily maintenance dose at bedtime. The control group had a methimazole 37.5 mg daily divided dose three times daily initially until thyroid hormones normalised and then had a maintenance dose given once daily at bedtime. The duration of treatment was 18 months and follow up was up to 4.5 years. Thyroid functions normalised in 22 (7 to 60) days in the CATO group and in 43 (12 to 150) days in the methimazole group. The relapse rates at two years were 16%(12/72) in the CATO group and 42% (29/69) in the methimazole group (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.60). The compliance rates were 96%. Four patients in the CATO group had topical skin reactions which were managed with local measures and did not require discontinuation.

Studies comparing antithyroid drugs

Most of the studies comparing antithyroid drugs (Homsanit 2001; Kallner 1996; Nicholas 1995) looked only at the initial response of the thyrotoxicosis within the first 3 to 6 months. Only one study (Peixoto 2006) looked at relapse rates at one year follow up. This study compared the remission and relapse rates in Graves' disease and looked at the side effect profiles. Patients were randomised to either propylthiouracil (PTU) 200 to 300 mg twice daily or methimazole (MMI) 40 to 60 mg once daily and the doses were titrated down to a maintenance dose. The duration of therapy was 12 months and relapse rates were assessed one year after treatment withdrawal. In the PTU group the relapse rate was 29% (6/21) while this was 60% (15/25) in the MMI group (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.92). However, there were large difference in the TSH receptor antibody titres and the relapses rates were similar when this was adjusted for in the analysis. There were no major differences in the side effects and the numbers are too small to make any comment on this. The authors conclude that there were no significant differences in relation to relapse rates, side effect profiles or compliance rates between the two drugs.

Discussion

There are several choices to be made when considering the drug treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism including the choice of drug, dose, duration of therapy, addition of thyroxine and factors to consider when discontinuing therapy. This review sought to examine the evidence available for these questions from the randomised controlled trials conducted in this field. The results of the review need to be interpreted with some caution as several of the trials had large losses to follow up. All the trials sought to follow up patients for over one year and the duration of follow up was between two to five years in seven trials. In the block‐replace versus titration regimens, there was a total loss of follow up of 27%.

The antithyroid drugs which were used in these randomised controlled trials included carbimazole, propylthiouracil and methimazole. Carbimazole was used by 1395 participants in 14 trials and methimazole was used by 967 participants in seven trials. Propylthiouracil was used in at least 250 participants in two trials. There were no suitable randomised trials using lithium or perchlorate. No definitive comment can be made on the efficacy or side effect profile of the individual drugs. However, it does appear that carbimazole has a slightly more favourable side effect profile. Among the studies that reported rash, 7% (49/722) participants on carbimazole reported rashes, while there were reports of rashes in 12% (82/714) of participants on methimazole. This has to be interpreted with caution as there were no direct drug comparison studies and the numbers were extracted from several studies. Five cases of agranulocytosis occurred in participants on methimazole and seven cases in participants on carbimazole though it is noted that two of the cases among those on carbimazole were on exceptionally high doses of 100 mg per day.

Duration of therapy

There is some evidence though not statistically significant that a 12 to 18 month duration of therapy is favoured to a shorter duration of therapy. This is stronger with use of the titration regimen (Allannic 1990) than for the block‐replace regimen (Weetman 1994). The 18 month titration regimen was significantly better than the 6 month regimen (Allannic 1990). Twelve months therapy was no less effective than 24 months titration regimen (Garcia‐Mayor 1992). Two of the studies (Garcia‐Mayor 1992; Maugendre 1999) using longer duration of therapy did not show any clear evidence of benefit in extending therapy beyond 18 months though the confidence intervals were wide. In a single quasi‐randomised study the six month block‐replace regimen was no less effective than the 12 month therapy (Weetman 1994). Cho 1992 has suggested that normalisation of TSH and TBII may be a useful marker in determining the length of therapy but this single trial was too small to assess this reliably.

Block‐replace therapy versus titration therapy

Longer term follow up data showed no clear evidence to suggest that the block‐replace therapy reduced relapse rates when compared to the standard titration regimen. There appeared to be a difference when studies with only up to 24 month follow up were considered; suggesting that the relapses occurred later in the block‐replace group. On combining the data from the shorter as well as longer‐term studies, the relapse rates were similar in both groups at 51% (322/636) in the block‐replace group and 54% (332/614) in the titration group when the losses to follow up were not considered. The results were sensitive to the way drop‐outs were handled and when analysis was carried out assuming relapsed hyperthyroidism in all drop‐outs there was a significant difference between the two groups, with relapse rates of 63% (549/870) in the block‐replace group and 68% (566/837) in the titration group. This result will need to be interpreted with caution due to the large number of dropouts (27%; 457/1707) and also take into consideration the higher incidence of side effects in the block‐replace regimen.

None of the studies showed significant differences in the rates of ophthalmopathy progression or looked at any quality of life indicators. There was in fact a significantly higher rate of drug withdrawal due to side effects, a significantly higher incidence of rashes and more episodes of agranulocytosis (no statistically significant difference) in the block‐replace group. The use of higher doses (carbimazole 100 mg such as used in the study by Grebe 1998), led to high rates of side effects, including a 12% (2/17) incidence of agranulocytosis which is a potentially life threatening complication. The largest multicentre trial (Benker 1998) did not use the titration regime but rather maintained the low dose group at methimazole 10 mg per day from the beginning.

Thyroxine supplementation after antithyroid drug therapy

The evidence in favour of thyroxine supplementation after antithyroid drug therapy comes primarily from one study (Hashizume 1991). The other two studies (Pfeilschifter 1997; Raber 2000) using combined antithyroid drugs with thyroxine, with the study by Pfeilschifter 1997, continuing thyroxine after completion of antithyroid drugs did not show any clear difference in relapse rates. A sensitivity analysis, excluding the study by Hashizume 1991, was not associated with a significant difference in the relapse rates following the addition of thyroxine. The discrepant result in the Hashizume 1991 study has been widely discussed considering various possibilities including the iodine intake in Japan and different immunological or genetic factors (Toft 1997). However, there is no wholly satisfactory explanation about this, though it is noted that the trials which have subsequently tried to reproduce the results have all used varying protocols and none of the studies have used the original protocol used by Hashizume 1991 of antithyroid drugs for 18 months followed by thyroxine for 36 months. Four studies (Glinoer 2001; Hoermann 2002; Mastorakos 2003; Nedrebo 2002) using thyroxine or placebo after completion of antithyroid drug therapy also failed to show a difference in relapse rates.

Immunosuppressive therapies

Two randomised controlled trials looked at immunosuppressive therapies. One Polish study (Huszno 2004) looked at the addition of azathioprine to methimazole. The relapse rates were 8% (3/36) in the azathioprine group compared to 54% (15/28) in the methimazole group (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.32). The safety and efficacy would need confirmation in further studies in different populations before the addition of a potentially toxic immunosuppressive agent is considered for the therapy of Graves' hyperthyroidism. One study in the Han Chinese population (Chen 2008) looked at using a compound antithyroid ointment (CATO) containing 12 mg of methimazole and 0.6 g of hydrocortisone and compared this with methimazole alone. The relapse rates at two years were 16%(12/72) in the CATO group and 42% (29/69) in the methimazole group (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.60). This would also need confirmation in different populations before the results can be generalisable. There is no topical preparation of methimazole which has undergone pharmaceutical preparation or testing outside China. There has been more recent interest in possible immunotherapy for Graves' disease. Rituximab, an anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, which causes B cell depletion in the circulation as well as the thyroid has been studied in a few phase 2 clinical trials. This shows some promise in Graves' ophthalmopathy and some benefit in hyperthyroidism but needs further evaluation and confirmation in clinical trials.

Summary of main results

The evidence (based on four studies) suggests that the optimal duration of antithyroid drug therapy for the titration block‐regimen is 12 to 18 months. The six month block‐replace regimen was found to be as effective as the 12 month treatment in one quasi‐randomised study.

The titration block‐(low dose) regimen had fewer adverse effects than the block‐replace (high dose) regimen and was no less effective in trials (based on 12 trials) of equal duration.

Continued thyroxine treatment following initial antithyroid therapy does not appear to provide any benefit in terms of recurrence of hyperthyroidism.

Studies using immunosuppressive agents need further validation of safety and efficacy in controlled trials among different populations.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results should be generalisable as the studies included participants from 16 countries (bearing in mind the limitations noted due to the large participant loss to follow up). The results obtained from trials in different countries were broadly consistent. The notable exception is the study from Japan (Hashizume 1991) and it is uncertain if there are other genetic or immunological factors which could have influenced this. Another exception would be a study (Chen 2008) of compound antithyroid ointment which is unavailable outside China and conducted solely in the Han Chinese population.

Quality of the evidence

Many of the trials failed to report trial methodology. Only five trials had allocation concealment which could be considered as adequate. The majority of trials had poor details of allocation concealment or randomisation and this was considered as unclear. Patient blinding with the use of a placebo was undertaken in three trials. Assigned allocation categories and quality scores of the included trials are included in Appendix 2.

Potential biases in the review process

The major limitation of the review is the large number of participants lost to follow up in the studies. In the block‐replace versus titration regimens, there was a total loss of follow up of 27%. The reasons for the large loss to follow up are unclear and this may include: patients feeling relatively well a few weeks after commencement of therapy and attainment of euthyroidism; relatively young age group of patients likely to have work and other commitments such that once euthyroidism is attained, they fail to comply with therapy and have a variable lag period before a relapse occurs; there may be other motives leading to poor compliance with therapy including maintenance of weight loss in young to middle aged women.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are unaware of other reviews looking at antithyroid drug regimen in the treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence suggests that the duration of antithyroid drug therapy for the titration regimen should be between 12 to 18 months. The six month block‐replace regimen was found to be as effective as the 12 month treatment in one quasi‐randomised study (Weetman 1994). The titration regimen appeared to have fewer side effects than the block‐replace regimen and there was no clear evidence to suggest this was less effective. The incidence of drug rashes and drug withdrawal due to side effects were significantly higher in the block‐replace regimen. There does not appear to be any benefit of continued thyroxine replacement following antithyroid drug therapy with regard to relapse rates of hyperthyroidism though the remarkable results of one study suggesting benefit remain unexplained.

Implications for research.

Large, well designed, adequately powered trials of block‐replace therapy versus titration therapy with monitoring of ophthalmopathy changes are needed to see if the regimens are different in this regard. Attempts should be made to reduce the number of participants lost to follow up. A common reason for considering block‐replace in many centres is to avoid transient periods of hypothyroidism while titrating the antithyroid drug dose. A large well designed study designed to look for quality of life issues and possible effects of transient undetected episodes of hypothyroidism during the initial period of the titration regimen in comparison with the block‐replace regimen would help clarify this aspect of management.

Direct comparisons of the three commonly used drugs should be considered as there seems to be some suggestion that carbimazole may have a more favourable safety profile.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 November 2009 | New search has been performed | In this update we updated our search to April 2009. Three new randomised control trials were added to the review. These studies looked at different interventions from previous studies in the review and were assessed individually. One study looked at the addition of azathioprine to methimazole and this resulted in fewer relapses at follow up. The safety of adding a potentially toxic immunosuppressive agent will need to be assessed before this can have any clinical practice implications. Another study considered the use of a topical preparation of methimazole and hydrocortisone in a Han Chinese population. A pharmaceutical preparation of this ointment is not available outside China and the improved results in this group will need to be confirmed in different populations. The third addition is the first study comparing the effect on relapse rates from using propylthiouracil or methimazole. The results were comparable once the baseline differences in antibody status were considered and the numbers were too small to show any differential effect on side effects. |

| 11 November 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The new studies on immunosuppressive therapies and combining drugs do not form a significant part of the conclusion and key outcomes are unchanged compared to the last update of this review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2002 Review first published: Issue 4, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2006 | New search has been performed | In this minor update we updated our search strategy to July 2006. One new study is awaiting assessment . Clarification on numbers of complications was received from one trialist and the findings of the review are unchanged. |

| 11 November 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The four additional trials influenced the results of the two subgroups reported below. Twelve trials examined the effect of Block‐Replace versus Titration regimen. The relapse rates were similar in both groups at 51% in the Block‐Replace group and 54% in the Titration group (Peto OR = 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.68‐1.08). The number of participants reporting rashes was significantly higher in the Block‐Replace group (10%, 63/616) as compared to the Titration group (5%, 31/622) (OR = 2.62, 95% CI: 1.20‐5.75). The number of participants withdrawing due to side effects was also significantly higher in the Block‐Replace group. (16%, 58/353) compared to 9%, 30/344 in the Titration group (Peto OR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.30‐3.18). Four trials considered the continuation of thyroxine alone after completion of antithyroid medication. There was no significant difference in the relapse rates between the groups after 12 months follow‐up with relapse rates being 31% (88/282) with thyroxine and 29% (82/284) with placebo (Peto OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.79‐1.67). |

Notes

Risk of bias figures were inserted to enable readers to compare authors' version with the one established by means of the official Cochrane Collaboration tool.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs Wendy Watson and Christine Park for their help with data extraction and quality assessment of the trials in the initial version of the Cochrane Review (Abraham 2005). We are grateful for the helpful advice and comments from Professor Adrian Grant and for the advice of Sheila Wallace and Cynthia Fraser on literature searching. We are grateful to Dr Amalia Mayo for translating the Spanish paper, Ms Aurelie Desbois for the French translation and Dr Micheal Sygula for the Polish translation..

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Search terms |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms; MeSH = Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); exp = exploded MeSH; the dollar sign ($) stands for any character(s); the question mark (?) substitutes for one or no characters; tw = text word; pt = publication type; sh = MeSH; adj = adjacent. MEDLINE: 1 Thyroid gland/ [Mesh term ‐any subterms and subtrees included] 2 thyro$ [in abstract or title] 3 Thyroid hormones/ [Mesh term ‐any subterms and subtrees included] 4 thyroid hormon$ [in abstract or title] 5 Graves' disease/ [Mesh term ‐any subterms and subtrees included] 6 grave$ [in abstract or title] 7 exp Hyperthyroidism/ 8 hyperthyr$ [in abstract or title] 9 exp Thyrotoxicosis/ 10 thyrotoxic$ [in abstract or title] 11 Goiter/ [Mesh term ‐any subterms and subtrees included] 12 goit$ [in abstract or title] 13 basedow$ diseas$ [in abstract or title] 14 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 15 Antithyroid agents/ [Mesh term ‐any subterms and subtrees included] 16 (antithyroid adj (agent$ or compound$ or drug$ or substanc$)) [in abstract or title] 17 goitrogen$ agent$ [in abstract or title] 18 (thyreostatic adj (agent$ or drug$ or compound$ or substanc$)) [in abstract or title] 19 (neomercazol$ or neo‐mercazol$ or mercazol$) [in abstract or title] 20 (aroclor or carbimazol$ or lithium carbonat$ or met?imazol$ or methylthiouracil$ or thiouracil$) [in abstract or title] 21 (propylthiouracil$ or tapazol$) [in abstract or title] 22 (22232‐54‐8 or 51‐52‐5 or 60‐56‐0) [in Chemical Abstract Service registry number] 23 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 24 14 and 23 |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias

| Study | a) allocation concealment | b) intention‐to‐treat | c) assesor blinding | d) comparability | e) identical care |

f) in/exclusion criteria |

g) interventions |

h) pariticipants blinding |

i) carers blinding |

j) follow up |

k) duration |

total |

| Allannic 1990 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Benker 1998 | A | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Chen 2008 | B | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Cho 1992 | B | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Edmonds 1994 | A | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Garcia‐Mayor 1992 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Glinoer 2001 | B | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| Goni Iriarte 1995 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| Grebe 1998 | B | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 13 |

| Hashizume 1991 | B | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Hoermann 2002 | A | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Huszno 2004 | B | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| Jorde 1995 | B | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 15 |

| Leclere 1994 | B | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Lucas 1997 | A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Mastorakos 2003 | A | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| Maugendre 1999 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| McIver B 1996 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| Nedrebo 2002 | B | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| Peixoto 2006 | B | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Pfeilschifter 1997 | B | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Raber 2000 | B | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Rittmaster 1998 | B | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Tuncel 2000 | B | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Weetman 1994 | C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Wilson 1996 | B | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (study completers only).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 6 months treatment | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Low dose | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 High dose | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 18 months treatment | 2 | 186 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.39, 1.43] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (study completers only), Outcome 1 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 6 months treatment.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (study completers only), Outcome 2 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 18 months treatment.

Comparison 2. Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (assuming relapse in all drop‐outs).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 6 months treatment | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Low dose | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 18 months treatment | 2 | 231 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.49, 1.48] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (assuming relapse in all drop‐outs), Outcome 1 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 6 months treatment.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Short versus longer duration of antithyroid drug therapy (assuming relapse in all drop‐outs), Outcome 2 Number of participants relapsing with over or under 18 months treatment.

Comparison 3. High dose (Block replace) regimen versus low dose (Titration) regimen (study completers only).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants relapsing | 12 | 1250 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.68, 1.08] |

| 1.1 12 to 24 month follow‐up | 5 | 229 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.30, 0.89] |

| 1.2 Over 24 month follow‐up | 6 | 948 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.74, 1.25] |

| 1.3 Unknown antithyroid drug dose | 1 | 73 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.23, 2.72] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High dose (Block replace) regimen versus low dose (Titration) regimen (study completers only), Outcome 1 Number of participants relapsing.

Comparison 4. High dose (Block replace) versus low dose (Titration) regimen (assuming relapse in all drop‐outs).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants relapsing | 12 | 1707 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.64, 0.98] |

| 1.1 12 to 24 month follow‐up | 5 | 376 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.43, 1.13] |

| 1.2 Over 24 month follow‐up | 6 | 1258 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.64, 1.04] |

| 1.3 Unknown antithyroid drug dose | 1 | 73 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.23, 2.72] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 High dose (Block replace) versus low dose (Titration) regimen (assuming relapse in all drop‐outs), Outcome 1 Number of participants relapsing.

Comparison 5. Complications: High dose (Block replace) regimen versus low dose (Titration) regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants with rash | 7 | 1238 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.17, 2.69] |

| 2 Number of participants with agranulocytosis | 5 | 943 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.84 [0.91, 8.91] |

| 3 Number of participants needing drug withdrawal due to side effects | 4 | 697 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.30, 3.18] |

| 4 Number of participants lost to follow‐up | 10 | 1478 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.71, 1.16] |

| 5 Drug rash either group | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6 Agranulocytosis either group | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7 Drug wthdrawal either group | Other data | No numeric data |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Complications: High dose (Block replace) regimen versus low dose (Titration) regimen, Outcome 1 Number of participants with rash.

5.2. Analysis.