Abstract

Background

Achieving and maintaining high levels of medication adherence are required to achieve the full benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART), yet suboptimal adherence among children is common in both developed and developing countries.

Objectives

To conduct a systematic review of the literature of evaluations of interventions for improving paediatric ART adherence.

Search methods

We created a comprehensive search strategy in order to identify all studies relevant to this topic. In July 2010, we searched the following electronic databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, LILACS, Web of Science, Web of Social Science, NLM Gateway (supplemented by a manual search of the most recent abstracts not included in the Gateway database). We searched abstracts from the International AIDS Conference from 2002 to 2010, the International AIDS Society Conference on Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention from 2003 to 2009, and from the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections from 1997 to 2010. We used search strategies determined by the Cochrane Review Group on HIV/AIDS. We also contacted researchers who work in this field and checked reference lists of related systematic reviews and of all included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised and non‐randomised controlled trials of interventions to improve adherence to ART among children and adolescents (age ≤18 years) were included. Studies had to report adherence to ART as an outcome.

Data collection and analysis

After one author performed an initial screening to exclude citations that did not meet the inclusion criteria, two authors did a second screening of those citations that likely met the criteria. For all articles that passed the second screening, full articles were pulled in order to make a final determination. Two authors then extracted data and graded methodological quality independently. Differences were resolved through discussion.

Main results

Four studies met the inclusion criteria. No single intervention was evaluated by more than one trial. Two studies were conducted in low‐income countries. Two studies were randomised controlled trials (RCT), and two were non‐randomised trials. An RCT of a home‐based nursing programme showed a positive effect of the intervention on knowledge and medication refills (p=.002), but no effect on CD4 count and viral load. A second RCT of caregiver medication diaries showed that the intervention group had fewer participants reporting no missed doses compared to the control group (85% vs. 92%, respectively), although this difference was not statistically significant (p=.08). The intervention had no effect on CD4 percentage or viral load. A non‐randomised trial of peer support group therapy for adolescents demonstrated no change in self‐reported adherence, yet the percentage of participants with suppressed viral load increased from 30% to 80% (p=.06). The second non‐randomised trial found that the percentage of children achieving >80% adherence was no different between children on a lopinavir‐ritonavir (LPV/r) regimen compared to children on a non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase regimen (p=.781). However, the proportion of children achieving virological suppression was significantly greater for children on the LPV/r regimen than for children on the NNRTI‐containing regimen (p=.002).

Authors' conclusions

A home‐based nursing intervention has the potential to improve ART adherence, but more evidence is needed. Medication diaries do not appear to have an effect on adherence or disease outcomes. Two interventions, an LPV/r‐containing regimen and peer support therapy for adolescents, did not demonstrate improvements in adherence, yet demonstrated greater viral load suppression compared to control groups, suggesting a different mechanism for improved health outcomes. Well‐designed evaluations of interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART are needed.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Infant; Male; HIV‐1; Medication Adherence; Anti‐HIV Agents; Anti‐HIV Agents/administration & dosage; CD4 Lymphocyte Count; HIV Infections; HIV Infections/drug therapy; HIV Infections/virology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Viral Load

Interventions to improve adherence to ART in children and adolescents

Achieving and maintaining high levels of medication adherence are required to realise the full benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART). We identified four studies that evaluated interventions designed to improve adherence to ART among children and adolescents age 18 years and younger. These studies showed that home‐based nursing, peer support for adolescents and LPV/r‐containing regimens have the potential to improve ART adherence, but more evidence is needed. Medication diaries do not appear to have an effect on adherence. There is a need for well‐designed evaluations of interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART.

Background

Description of the condition

In 2007, there were an estimated 2.5 million children (1.7‐3.4 million) under the age of 15 living with HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS 2010). In addition, an estimated 420,000 children (350,000‐540,000) younger than 15 were newly infected with HIV in 2007, primarily through mother‐to‐child transmission during pregnancy, delivery or breastfeeding. The majority of children infected with HIV live in resource‐limited settings, in particular sub‐Saharan Africa (90%).

Highly active combination antiretroviral treatment (ART) has been shown to markedly improve the health of HIV‐infected children (Eley 2004, Puthanakit 2007). ART leads to a reduction in plasma HIV RNA levels, increased CD4 cell counts, improved immunologic function, decreased incidence of opportunistic infections, improved growth and development, decreased morbidity and mortality and decreased number of hospitalisations (Patel 2008, Resino 2006). However, studies of both adults (Bangsberg 2001, Hogg 2002) and children (Watson 1999, Van Dyke 2002) show that achieving and maintaining high levels of medication adherence are required to realise the full benefits of HAART. Further, maintenance of high levels of adherence reduces the emergence of drug‐resistant virus since the consistent presence of antiretroviral medications suppresses ongoing viral replication (Harrigan 2005).

Suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral medications among children is common (Reddington 2000, Martinez 2000, Murphy 2001). Compared with adults, children and adolescents face additional challenges with ART adherence. First, children, unlike adults, depend on caregivers to administer their medication, who themselves may have HIV/AIDS or may not be a biologic relative. Children's adherence behaviour may be influenced by developmental stages, such as rebellion in the adolescent years. They may not know they are infected with HIV or may not understand the meaning of HIV infection or the importance of taking their medicines. Children also face challenges related to scheduling their medication around school and other activities. Finally, small children may not be able to take pills, and syrup formulations are sometimes unpalatable or difficult to administer.

Description of the intervention

Any intervention or strategy for improving paediatric adherence to antiretroviral regimens.

How the intervention might work

Pathways by which interventions might work to improve paediatric adherence to ART vary depending on the type of intervention. For example, education and behavioural interventions may improve motivation to adhere to medication by increasing knowledge about the treatment regimen and the consequences of non‐adherence. Conversely, directly observed therapy (DOT) interventions require that the patient take medications in the presence of a health worker or other designated individual in order to avoid missing medications.

Why it is important to do this review

ART is becoming increasingly available to clinically eligible children in resource‐limited settings through governments, multilateral and nongovernmental organizations (Havens 2007). As treatment becomes more available to children and adolescents in resource‐limited settings, efforts to ensure high levels of adherence to antiretrovirals are essential for maximal clinical effectiveness and preservation of treatment options.

To our knowledge, only one systematic review, published in 2007, has covered interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART (Simoni 2007). The review identified seven studies, of which only one had a control group; the other studies consisted of pre/post data with no comparison group. The interventions included directly observed therapy (DOT), use of a gastronomy tube and education and behavioural interventions. Another review covered interventions to improve adherence to ART among 13‐24 year olds in the United States of America (Reisner 2009). This review found no studies that used a comparison group; all were pre/post studies. Interventions included DOT, cell phone reminders, youth education and a behavioural intervention based on the stages of change model. The current review differs from these two reviews in that it is more current; it requires included studies to have a control group; and it focuses on a broad range of ages, from infants to age 18 years.

Objectives

To conduct a systematic review of the literature of evaluations of interventions for improving paediatric (age <18) ART adherence.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Study inclusion criteria

Study must evaluate an intervention that aims to improve peadiatric adherence to ART

Randomised controlled trials and non‐randomised trials

Participants must be HIV‐infected children less than or equal to 18 years of age

Study must measure adherence to ART as an outcome

Study exclusion criteria

Letters, editorials, non‐systematic reviews, observational studies, case reports, cross‐sectional study designs or descriptive studies

Studies that did not directly measure adherence

Studies that measured adherence by provider report

Types of participants

HIV‐infected children 18 years of age or younger on ART. We included studies of children as well as adults if at least half of the study population was age 18 or younger. We included studies if at least 75% of the population was on ART.

Types of interventions

All interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART were included, including both behavioural and medical interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Adherence to ART, as measured by child or caregiver report, pill count, volume measurement (for liquid formations), unannounced home visit/pill count or electronic monitoring (e.g., Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) caps).

Secondary outcomes

Clinical or virologic failure

Viral load

CD4 counts

Morbidity

Mortality

Disease progression

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the HIV/AIDS Cochrane Collaborative Review Group search strategy. We formulated a comprehensive and exhaustive search strategy in an attempt to identify all relevant studies regardless of language. Full details of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Review Group methods and the journals hand‐searched are published in The Cochrane Library in the section on Collaborative Review Groups (http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/HIV/frame.html). We combined the search strategy developed by The Cochrane Collaboration and detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) in combination with terms specific to adherence and antiretroviral therapy regimens.

Limits. The searches were performed without limits to language or setting. The searches were limited to human studies published from January 1980 through July 2010. See Appendix 1 for our PubMed search strategy, which was modified as appropriate for use in the other databases.

Electronic searches

Journal and trial databases

MEDLINE

EMBASE

CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

CINAHL

LILACS

Web of Science

Web of Social Science

Conference databases

NLM Gateway (for HIV/AIDS conference abstracts before 2005)

International AIDS Conference (2002 to 2010), IAS Conference on Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention (2003 to 2009), and the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (1997 to 2010).

Ongoing trials

United States National Institutes of Health's clinical trials registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov)

Searching other resources

Manual searches were conducted as follows:

Reference checking: The strategy was iterative, in that references of included studies were searched for additional references. We also checked references of published systematic reviews related to this topic (Ford 2009; Haberer 2009; Hart 2010; Haynes 2008; Reisner 2009; Simoni 2007; Steele 2003; Vreeman 2008).

Communication with authors: Efforts were made to contact experts in order to identify unpublished research, negative findings and trials still underway.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One author performed an initial screen of all identified titles and abstracts, removing all those which clearly did not fit inclusion criteria. Full text articles were obtained of all selected abstracts and an eligibility form was used to determine final study selection. Two authors independently reviewed articles to determine final eligibility. Differences were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers independently extracted and entered data from the full‐text articles onto a detailed and standardised data form. Extracted information included:

Study details: citation, start and end dates, location, study objective, study design and details, randomisation.

Participant details: description of intervention and control groups, study population eligibility (inclusion and exclusion) criteria, ages, population size, ART regimens used, other drug therapies, orphanhood, attrition rate.

Interventions details: type of intervention, intervention description, follow‐up.

Outcome details: measures of adherence, determinants of adherence, cut‐off used for determination of optimal adherence, primary outcomes, secondary outcomes, results, conclusions.

All relevant data were entered into Cochrane's Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Application of Cochrane Collaboration tools for risk of bias for each individual study was done and presented in summary tables. The Cochrane approach assesses risk of bias in individual studies across six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential biases (Higgins 2008).

Sequence generation

Adequate: investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process, such as the use of random number table, coin tossing, card or envelope shuffling.

Inadequate: investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process, such as the use of odd or even date of birth, algorithm based on the day or date of birth, hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of the sequence generation process.

Allocation concealment

Adequate: participants and the investigators enroling participants cannot foresee assignment (e.g., central allocation; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes).

Inadequate: participants and investigators enroling participants can foresee upcoming assignment (e.g., an open random allocation schedule, a list of random numbers), or envelopes were unsealed, non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of the allocation concealment or the method not described.

Blinding

Adequate: blinding of the participants, key study personnel and outcome assessor and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. Not blinding in the situation where non‐blinding is unlikely to introduce bias.

Inadequate: no blinding or incomplete blinding when the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of adequacy or otherwise of the blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Adequate: no missing outcome data, reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome or missing outcome data balanced in number across groups.

Inadequate: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in number across groups or reasons for missing data.

Unclear: insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions.

Selective reporting

Adequate: a protocol is available which clearly states the primary outcome is the same as in the final trial report.

Inadequate: the primary outcome differs between the protocol and final trial report.

Unclear: no trial protocol is available or there is insufficient reporting to determine if selective reporting is present.

Other forms of bias

Adequate: there is no evidence of bias from other sources.

Inadequate: there is potential bias present from other sources (e.g., early stopping of trial, fraudulent activity, extreme baseline imbalance or bias related to specific study design).

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgement of adequacy or otherwise of other forms of bias.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis for all studies was individuals.

Dealing with missing data

Missing data were not analysed. Authors were not contacted for missing data.

Assessment of reporting biases

We minimised the possibility of reporting bias by conducting a broad and comprehensive search strategy, without language limitation.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

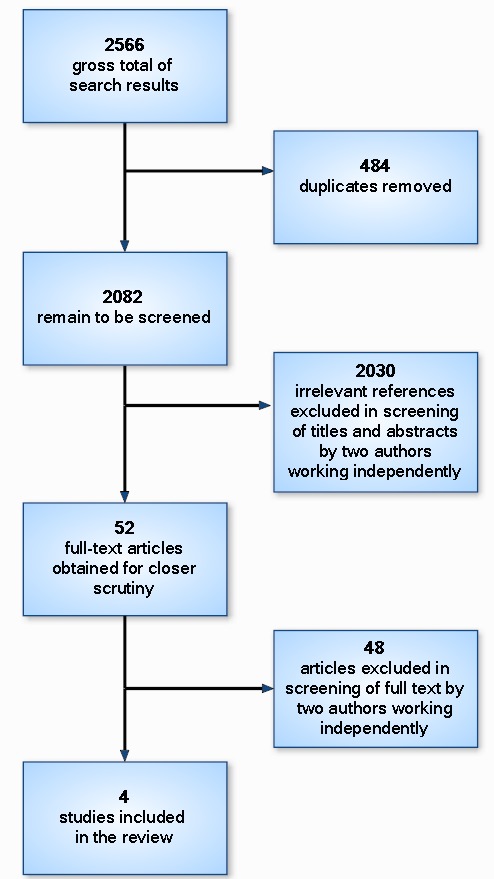

The database search resulted in 2566 citations. After duplicates were removed, 2082 citations remained to be screened. An initial single screening resulted in 2030 studies being excluded. The remaining 52 articles were pulled for double screening. Of these, four met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. See Figure 1 for a flowchart depicting our screening process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting screening process.

Included studies

Randomised trials

Berrien 2004 presents results from a non‐blinded randomised trial of a home‐based intensive nursing intervention, conducted in Hartford, Connecticut, USA, to improve knowledge of HIV, ART and adherence. All HIV‐infected patients at a hospital paediatric HIV programme were invited to participate, and a total of 37 patients and their parents agreed to participate. Participants ranged in age from 1.5 to 20 years, with a mean of 10 years. The intervention consisted of eight structured home visits by a single nurse over three months. The visits began with an emphasis on assessing the knowledge of the patient and caregivers with regard to the HIV disease and medication and assessing problems with adherence. As the relationship developed between the home visit nurse and the family, the visits progressed to HIV education and creating an individualised plan of care and assessing progress. Incentives such as medication boxes, beepers, small toys and diaries were used to help with adherence. The control group received standard medication adherence education in the clinic setting, with a single home visit if the staff determined it was necessary. Adherence was measured by medication refill history and self‐report. Secondary outcomes included viral load and CD4+ T‐cell percentages, assessed immediately after the intervention and at 6‐11 months post‐intervention. The study found that self‐reported adherence improved in the home‐based nursing intervention group compared to the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.07). However, there was a statistically significant difference (p=0.002) in pharmacy refill history. There was no difference between the intervention and control groups with regard to biological outcomes, viral load or CD4 count.

Wamalwa 2009 presents results from a non‐blinded randomised trial of medication diaries for use by caregivers to improve children's adherence to ART. The study was conducted in the paediatric wards and HIV clinic of a national hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. A total of 99 children between the ages of 15 months and 12 years (interquartile range 2.3 to 6.2, median 4.7) was randomised to receive the intervention plus counselling or counselling alone. Caregivers assigned to the intervention were given a medication diary at the time of ART initiation along with verbal instructions on how to use it, putting a tick mark next to each required medication each day. Diaries were checked by staff at each appointment, and caregivers were to use the diaries for a period of nine months. Adherence was measured by caregiver self‐report. Secondary outcomes included CD4 percentage, virologic response, weight‐for‐age, height‐for‐age and weight‐for‐height at three, nine and 15 months after ART initiation. The study found that, based on caregiver report, the control group had higher adherence compared to the intervention group, though the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.08). There was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups with regard to viral load, weight‐for‐age, height‐for‐age or weight‐for‐height. They did find that mean CD4 cells/µl at six months post‐intervention was higher in the control group compared to the diary group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Non‐randomised trials

Funck‐Brentano 2005 presents results from a three‐arm non‐randomised trial of peer support group therapy for adolescents with HIV attending an outpatient clinic in Paris, France. A total of 30 adolescents, ages 12 to 17 years, made up the study population, and they fell equally into three groups: (1) those who chose to participate in group therapy; (2) those who declined; and (3) those who lived too far away to be offered participation. The intervention consisted of open‐ended 90‐minute sessions every six weeks for 26 months led by two therapists. Sessions consisted of themes determined by the participants and aimed to foster cohesiveness, enable members to share experiences and promote change toward individual goals. Outcomes included three psychological areas from the adolescent's perspective: (1) perceptions of the infection/disease (measured by the Perceived Illness Experience Scale), (2) perceptions of treatment (measured by the Perceived Treatment Inventory) and (3) self‐esteem (measured by the Self‐Esteem Inventory). One of the five elements of the Perceived Treatment Inventory was compliance, measured using a five‐point scale where one represents few problems with compliance and five represents high problems with compliance. Medical data were also collected, including clinical condition, CD4 and viral load and patient's adherence as subjectively perceived by the paediatrician. All outcomes were measured two years after the study began. They reported no changes between baseline and follow‐up compliance for any of the three study groups. However, more adolescents in the peer support group therapy intervention group achieved low viral load compared to those in the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.063). There was no statistically significant difference in CD4 cell counts or percentages between intervention and control groups.

Muller 2009 conducted a three‐arm non‐randomised trial of three treatment regimens' effect on adherence and virological suppression among children attending a paediatric HIV clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. Data were obtained for a total of 66 children (mean age 51 months + 24 months), who were on three different regimens: (1) 39 were receiving a ritonavir‐boosted lopinavir (LPV/r)‐containing triple regimen; (2) six were receiving an unboosted protease inhibitor (PI) regimen (ritonavir plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTI]); and (3) 21 were receiving two NRTIs plus a non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI, either nevirapine or efavirenz). Adherence to treatment was measured monthly for three months using MEMS caps, and virological data were collected every six months. They found no difference in adherence between the three groups receiving different medication regimens, yet children receiving PI‐based regimens demonstrated higher rates of virological suppression compared to the children receiving an NNRTI‐based regimen (p=0.002).

Excluded studies

Randomised controlled trials

Naar‐King 2006 describes the results of a pilot study of Healthy Choices, Healthy Choices, a motivational intervention for adolescents infected with HIV designed to reduce risk behaviours. The study was conducted in the U.S.A., and the primary outcome was viral load. The study was excluded because adherence was not directly measured as an outcome.

Naar‐King 2008 is a brief report of a randomised controlled trial of the Healthy Choices intervention, the pilot of which was reported in Naar‐King 2006. The study was excluded because adherence was directly measured as an outcome. Also, fewer than 40% of participants in the study were taking antiretroviral drugs.

Naar‐King 2009 is a full report of the same study reported in Naar‐King 2008. It was excluded because adherence was not measured as an outcome.

Naar‐King 2010 reports on the same study as Naar‐King 2009. This article reported on intermediate outcomes from the 3‐month follow‐up visit. The study was excluded because adherence was not measured as an outcome.

la Porte 2009 is a randomised trial of two regimens to treat HIV‐infected children between the ages of six months and 18 years. The two treatments were either once‐daily LPV/r (460/115 mg/m2) plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) or twice‐daily LPV/r (230/57.5 mg/m2) plus two NRTIs. Patients either received treatment 1 followed by treatment 2 or treatment 2 followed by treatment 1. The study reported plasma concentration as an outcome, and was excluded because adherence was not measured as an outcome.

le Roux 2009 is a randomised controlled trial of two dosing schedules of isoniazid prophylaxis to treat tuberculosis among HIV‐infected children. Because the study did not attempt to improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment, it was excluded from the review.

Non‐randomised trials

Omo‐Igbinomwanhia 2004 reported a non‐randomised trial of directly observed therapy as an intervention to improved adherence to ART among children attending an HIV/AIDS treatment centre in Trinidad and Tobago. A total of 50 children participated in the trial, although age and gender of participants was not reported. This study was excluded because adherence was not directly measured. Outcomes reported included CD4+ count and viral load after two years.

Wilson 2009 reported the results of an intervention of viral load monitoring, patient education materials, and counselling on first‐line ART adherence in Thailand. Patients were classified according to whether they had undetectable, low detectable, or high detectable viral load and were offered education and counselling appopriate to their viral load status. The primary outcome was whether detectable viral load became undetectable. The study was excluded because adherence was not directly measured.

Before‐after studies

Bunupuradah 2006 reports the results of a taste‐masking product to aid children age 1‐10 years in Thailand take ARVs. Children were allowed to select their favorite flavors, then caregivers were instructed to mix the product with medications using a specific procedure specific to that child's formulation and dosing. Thirty children were included in the study, but it was excluded because there was no control group.

Byakika‐Tusiime 2009 reported on the adherence outcomes of a family‐based treatment intervention targeting parents with HIV and their children infected with HIV in Uganda. Participants were attending the "Mother‐to‐Child Transmission Plus" programme. This study was excluded because there was no control group.

Ellis 2006 was an intervention of multi‐systemic therapy for children age 1‐16 years in the USA. The study team evaluated three systems, individual, family and community, for each child, with a goal to identify barriers to adherence. Interventions were then tailored to each participating family, of which there were 18. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Garvie 2007 reported the results of a pill‐swallowing training targeting children and youth age 4 to 21 years with HIV in the USA. The children were training in individual sessions where swallowing techniques were demonstrated by the trainer and then practiced by the child with placebos. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Gaur 2008 was a study of directly observed therapy among 20 adolescents ages 18‐24 years in the USA. Twenty adolescents participated in the intervention, in which DOT was administered each day at a location chosen by the participant. DOT was tapered over time to self‐administered therapy depending on the results of ongoing assessments. The study was excluded because there was not control group.

Gigliotti 2001 reported on an intervention of directly observed therapy for six children age 3‐11 years in the USA. Children were admitted to the hospital for four to eight days of DOT if they had poor responses to ART despite caregiver reporting of adherence to therapy. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Glikman 2007 was a study of directly observed therapy among children on ART in the USA. Nine patients age 7‐17 years were recruited because of suspected non‐adherence with their prescribed treatment regimens. They were observed taking medications during seven days of hospitalization. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Hansudewechakul 2006 reported on an individualised plan for adherence to ART among 110 children with HIV in Thailand. The adherence plan included home visits, hospital visits, a preparation day before ART initiation, and a once‐a‐year Children's Camp. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Lyon 2003 reported the results of 12‐week youth/caregiver support groups and education on adherence to ART among a population of youth infected with HIV in the USA. The education consisted of the dynamics of HIV, the purpose of medications, managing side effects, nutrition and exercise, and communication with providers. Each week, a device such as pillboxes and calendars was introduced to help the youth adhere to medication. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

McKinney 2007 reports the results of a novel once‐daily treatment regimen of antiretroviral drugs to improve adherence among children with HIV. The regimen consisted of a combination of three drugs: emtricitabine, didanosine, and efavirenz. A total of 37 subjects age 3 to 21 years were included in the study. However, it was excluded because there was no control group.

Myung 2007 was a study of directly observed therapy for late‐stage HIV‐infected orphans in Cambodia. Ninety‐five children from infants to 18 years were enrolled for a minimum of six months. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Parsons 2006 was a study of directly observed therapy among a group of children in the USA who had elevated viral loads even though they were on HAART. Nineteen children age infant to 16 years were enrolled in the study. Children were hospitalised and put on DOT. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Puccio 2006 reported the results of a pilot study of cell phone reminders to take HAART for youth ages 16‐24 years in the USA. The pilot included only five youth and included weekly reminders for 12 weeks. The study was excluded because there was no control group. Also, the sample size was small.

Purdy 2008 was a study of directly observed therapy for adolescents age 14‐19 years in the USA. Subjects were recruited if they had vertically acquired HIV, were on a stable HAART regimen, and had either viral load rebound or nonresponse. Five subjects participated and had DOT over a period of at least four days, as well as counselling for the caregiver and child. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Roberts 2004 reported on a stepwise approach to improve adherence among children who had persistently high viral loads despite treatment with ART. A total of six children age 0 to 17 years in the USA were recruited. The approach started with visits by a home nurse. If viral load continued to be high, children were hospitalised for four days and directly observed taking medications. If viral load rebounded after this step, providers initiated reports of medical neglect to the state's department of human services. The study was excluded because there was not control group.

Rogers 2001 was a study of a series of interventions corresponding to participants' stages of change. The study population consisted of 18 HIV‐infected youth ages 13‐22 years in the USA. The stages of change consist of pre‐contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action/maintenance, and relapse. The intervention included booklets, videotapes and audiotapes. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Shingadia 2000 reports the results of a retrospective chart review of 17 paediatric patients for whom gastrostomy tube insertion was used to improve adherence to HAART. The study was conducted in the USA, and it was excluded because there was no control group.

Sophan 2006 was a study of modified directly observed therapy (M‐DOT) among 26 children ages 13 months to 12 years in Cambodia. During the first month of the intervention, a nurse observed the child take one of two daily doses. The observations then tapered each month, with the nurse observing fewer doses per week. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Temple 2001 reported the results of gastrostomy tube insertion among children on HAART in the USA. Six children who had difficulty with adherence to HAARt were enrolled after all other options to improve adherence had been exhausted. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

van Griensven 2008 reported the results of an intervention targeting children with HIV ages 8 months to 15 years in Rwanda. The intervention was nurse‐centered ARV care, including child‐centered approaches, such as counselling about disclosure and ART, designated days for children's clinics, and support groups; and caregiver‐centered approaches, such as discussion groups and counselling. This study was excluded because there was no control group.

Van Winghem 2008 was a study of child‐centered approaches to improving adherence to ART among children from infants to age 14 years in Kenya. The approaches included patient‐related factors, therapy‐related factors, patient‐provider relationship factors, and psycho‐social support. The study was excluded because there was no control group.

Other studies

Baldassari 2002 was a conference abstract describing a multidisciplinary team of providers who help with the process of decision‐making around disclosure of HIV status to children with HIV. The abstract described the process, but the study was excluded because adherence to ART was not reported as an outcome.

Calles 2000 described a videotape to motivate children with HIV starting ART to adhere to their regimens. It is meant to be used along with discussions with the child, caregivers and providers about treating HIV. This conference abstract was excluded because it was an intervention description only; no outcomes were reported.

Chiappetta 2009 reports the development of a taste‐masking product for increasing adherence of paediatric antiretroviral treatment. The product was tested by healthy human volunteers and found to taste acceptable. The study was excluded because it did not have a control group and it did not measure adherence as an outcome.

Davies 2008 was a prospective cohort study reporting determinants of adherence among young children in South Africa. The study was excluded because there was no intervention.

Dunn 1998 reports the development of guidelines for ARV treatment for children with HIV by Cornell University Medical College in the USA. This conference abstract reports how these guidelines decreased mortality and the number of hospitalised days for children with HIV; however the study was excluded because adherence was not reported as an outcome.

Gous 2004 is a conference abstract describing several methods for improving paediatric adherence to ART, as suggested by providers from a hospital in South Africa. However, the abstract was excluded because it was not an actual study, and no outcomes were measured or reported.

Inaka 2002 describes an intervention of counselling for HIV care targeting parents of children at a paediatric clinic in Cote d'Ivoire. The intervention also included a home visit each week and information about adherence. This conference abstract was excluded because no outcomes were reported.

Kammerer 2006 reports the results of a study examining the relationship between cognitive and behavioural functioning and medication adherence among children in a large cohort study. The study was excluded because there was no intervention.

Kraisintu 2004 is a conference abstract describing Thailand's policies and issues related to paediatric formulations of antiretroviral medications. The abstract was excluded because there was no intervention and no outcomes reported.

Marazzi 2006 describes rates of adherence to HAART among participants in the DREAM programme in Mozambique. The study was excluded because there was no intervention.

Miah 2006 describes an intervention in which a psychologist uses a modeling technique to help children on ART with pill swallowing. The study was excluded because it only described the intervention; no outcomes were reported.

Rabkin 2004 describes an intervention of training for multidisciplinary teams of providers in four modules related to adherence to ART for women and families. This conference abstract describes the four modules that have been offered to over 400 provider teams in eight different countries. The study was excluded because it only described the intervention; no outcomes were reported.

Reisner 2009 is a literature review of interventions to improve adherence to ART among 13‐24 year old youth with HIV in the USA. The study was excluded because it was a review and was not original research.

Rivers 1992 is a literature review of aids for compliance to medication therapy. The study was excluded because it was a review and not original research; because it did not focus on children; and because it did not focus on adherence to ART.

Rudy 2009 was a study to determine the effect of short cycle therapy among 32 adolescents and youth infected with HIV. Recruited subjects were required to have good viral suppression. The short cycle therapy consisted of four days on and three days off. The study was excluded because there was not control group.

Schmalb 2004 reports on an intervention called the "Toy's Library" targeting children with HIV in Bahia state, Brazil. The intervention is a special setting containing games, toys, books for children and adolescents, and a team of professionals that facilitate artistic expressions to help children manage their diseases. The study was excluded because it was a qualitative study and did not report on quantitative measures of adherence.

Shah 2007 is a review and commentary on paediatric adherence to ART. The study was excluded because it was a review and was not original research.

Simoni 2003 is a review of the literature on adherence to ART among adults with HIV. The study was excluded because it was a review and not original research, and because it focused on adults and not children.

Simoni 2007 is a literature review of interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART. The study was excluded because it was a review and was not original research.

Ongoing trials

Pediatric Impact is a randomised controlled trial of a family intervention to improve adherence to ART among children ages 5‐12 at three HIV clinics in the U.S.A. The intervention consists of a tailored plan for each family consisting of medication management and swallowing, disclosure, education, behaviour change and referrals to other services. Adherence is measured by self‐report, provider assessment and MEMS caps.

Risk of bias in included studies

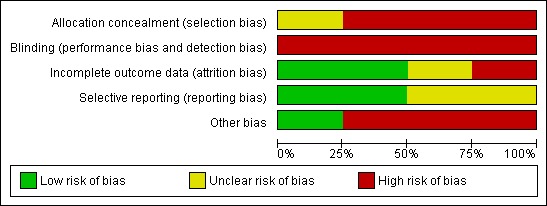

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of the assessment of bias according to the Cochrane Collaboration's assessment of bias tool.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Three of the studies did not conceal allocation, and in the fourth study allocation concealment was unclear. Two of the studies (Funck‐Brentano 2005, Muller 2009) were non‐randomised trials, and so patients either self‐selected into the study arms or were assigned based on other factors. In Berrien 2004, patients were randomised using the Small Table of Random Digits, and so allocation would not have been concealed from investigators. In Wamalwa 2009, computer‐generated block randomisation was used to assign participants to each group, but it is unclear if participants or investigators could have foreseen assignment.

Blinding

None of the studies blinded participants or investigators to allocation to intervention or control groups. For the two non‐randomised trials (Funck‐Brentano 2005, Muller 2009), patients self‐selected or were assigned to study arms based on specific attributes. For Berrien 2004, it was not practical for an independent observer to administer the questionnaires, and so the study nurse conducting home visits did so. For Wamalwa 2009, participants and investigators would know which patients had been assigned to the diary arm versus the control arm.

Incomplete outcome data

In two of the four included studies, incomplete outcome data were addressed. In Berrien 2004, study authors reported deaths and withdrawals from the study and from which study arm they came. They conducted an intent‐to‐treat analysis that included participants lost to follow‐up, assuming they had not change in adherence. Wamalwa 2009 reported loss to follow‐up from each study arm and at each time point in the study, nine months and 15 months, as well as the number of deaths. An intent‐to‐treat analysis was conducted to account for those lost to follow‐up. In the other two studies, incomplete outcome data were not addressed. In Funck‐Brentano 2005, participants lost to follow‐up were excluded from the analysis. No reason is given for the missing data, although the methods section describes that questionnaires missing more than 10% of items were excluded from the analysis. For Muller 2009, data were missing for 12 children for various reasons, but it was not reported in which treatment arm these children were. The final analysis excluded these children.

Selective reporting

Two of the studies (Muller 2009, Wamalwa 2009) appeared to be free of selective reporting. In both cases, all outcomes mentioned in the methods sections were reported in the results sections. In the remaining two studies (Berrien 2004, Funck‐Brentano 2005), it was unclear if they were free of selective reporting. In Berrien 2004, CD4 counts and percentages were listed in the methods section as outcomes measured in the study, but the results of these outcomes were not presented. In Funck‐Brentano 2005, patient's adherence as subjectively perceived by the physician was listed as an outcome, but was only reported at baseline.

Other potential sources of bias

Of the four included studies, only Wamalwa 2009 appeared to be free of other potential sources of bias. The two study arms differed at baseline on CD4 count and proportion of parents who reported prior use of antrietroviral drugs themselves, but these variables were adjusted for in the models. In Berrien 2004, the sample size of the study was small (follow‐up data was available for 34 participants), participants were recruited from only one institution and 33% of those invited to participate refused to do so. Participants self‐selected to participate in the intervention or not in Funck‐Brentano 2005, which introduced selection bias. For Muller 2009, non‐random assignment to study arms, small sample size (n=66) and short duration of follow‐up (three months) may each have introduced bias.

Effects of interventions

Adherence

Only one study demonstrated a positive and statistically significant effect of the intervention on medication adherence (Berrien 2004). This study found that self‐reported adherence improved in the home‐based nursing intervention group compared to the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.07). However, they did detect a statistically significant difference (p=0.002) in pharmacy refill history.

Conversely, three studies found no positive effect of the interventions on adherence. Funck‐Brentano 2005 reported no changes between baseline and follow‐up compliance for any of the three study groups (the peer support group therapy intervention and two control groups). The measure for adherence in this study was self‐reported. Muller 2009 also found no difference in adherence, as measured by a MEMS device, between the three groups receiving different medication regimens. Finally, Wamalwa 2009 found that the control group had higher adherence based on caregiver report compared to the diary intervention group, though the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.08).

Biological outcomes

All four studies evaluated the effect of the interventions on virological outcomes, and two of the studies found a positive effect of the intervention on decreasing viral load. Funck‐Brentano 2005 reported virological outcome as the percentage of participants achieving a viral load of <200 copies/mL. They found that more adolescents in the peer support group therapy intervention group achieved low viral load compared to those in the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.063). Muller 2009 reported virological outcome as the percentage of participants achieving a viral load of <50 copies/mL, and found that children receiving PI‐based regimens demonstrated higher rates of virological suppression compared to the children receiving an NNRTI‐based regimen (p=0.002).

The other two studies (Berrien 2004 and Wamalwa 2009) found no significant difference between the intervention and control groups with regard to viral load.

Only one study (Muller 2009) did not report any information about CD4 cell counts or percentages. Two studies (Berrien 2004 and Funck‐Brentano 2005) stated that there was no statistically significant difference in CD4 cell counts or percentages between intervention and control groups, although they did not report the data. Wamalwa 2009 reported mean CD4 cells/µl at six months post‐intervention and found a higher CD4 count in the control group compared to the diary group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

One study (Wamalwa 2009) evaluated the effect of the intervention on other biological outcomes. They found no significant difference between the diary and control arms on weight‐for‐age, height‐for‐age or weight‐for‐height.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Despite an extensive search strategy, only four studies were identified that reported results of a controlled trial of an intervention to improve paediatric adherence to ART. Each of the studies assessed a different intervention. Two were behavioural interventions: a peer support group therapy intervention for adolescents (Funck‐Brentano 2005) and a medication diary intervention for caregivers (Wamalwa 2009). One was a structural intervention and tested a home‐based nursing intervention (Berrien 2004), The fourth study consisted of a comparison of treatment regimens (Muller 2009). The studies also varied in terms of their target populations, measurement of adherence and length of follow‐up.

Only one of the interventions demonstrated an effect on adherence to ART (Berrien 2004). A home‐based nursing intervention targeting children and youth ages 1.5‐20 years, evaluated by a randomised controlled trial, resulted in improved adherence as measured by self‐report immediately after the intervention, although the difference was not quite statistically significant (p=0.07). However, adherence measured by pharmacy refill history showed significant improvement in the intervention group as compared to the control group (p=0.002). Although the study found an improvement in adherence immediately after the intervention, there were no difference in the changes in viral load between the intervention and control groups, measured between three and eight months after the intervention.

On the other hand, a medication diary intervention for caregivers of children (median age 4.7 years) on ART, also evaluated by a randomised controlled trial, demonstrated no effect on adherence, HIV infection status or child growth (Wamalwa 2009). In fact, caregivers of children in the intervention group were less likely to report no missed doses (85%) compared to those in the control group (92%), although this difference was not quite statistically significant (p=0.08). A possible reason for the lower reported adherence in the intervention group was a greater awareness of missed doses as a result of keeping a medication diary.

The other two interventions were evaluated by non‐randomised trial designs, one of a peer support group for adolescents (Funck‐Brentano 2005) and one comparing ART regimens (Muller 2009). Both studies demonstrated no effect on adherence, yet improvements in viral load suppression, as a result of the intervention. The Muller 2009 study concluded that boosted PI regimens might be more forgiving of poor adherence than an NNRTI‐based regimen. Funck‐Brentano 2005, a two‐year study of peer support group therapy for adolescents with HIV, was not focused on improving adherence to ART. The study examined several outcomes, including perceptions of the disease, perceptions of treatment and self‐esteem; and three of the 30 participants were not on ART. The authors concluded that the intervention can improve participants' emotional well‐being, which in turn can improve medical outcomes. The results suggest that the improvements in suppressing viral load may be a result of other factors and not improvement in adherence to medication.

We identified several interventions in the literature that were evaluated through observational studies, and many of these showed promise for improving adherence to ART. These include: directly observed therapy, cell phone reminders, pill swallowing training and several educational and supportive interventions targeting patients and their caregivers. These interventions need to be evaluated using more rigourous study designs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Each of the studies assessed a different intervention. Because of heterogeneity in the types of interventions, we were unable to pool data for meta‐analysis.

We were unable to demonstrate a relationship between improved adherence and other biological outcomes. For example, Berrien 2004 found an effect of the intervention on adherence but no effect on biological outcomes, whereas Funck‐Brentano 2005 and Muller 2009 found an effect on viral load yet no effect on adherence. Wamalwa 2009 consistently found no statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups on adherence or biological outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

In general, the studies were of low quality. Only two were randomised controlled trials; the other two were non‐randomised trials and therefore introduced selection bias. All of the studies had small sample sizes of fewer than 100 participants.

One other possible source of bias was the variation in measures of adherence across the four studies. Measures of adherence included self‐report (Berrien 2004, Funck‐Brentano 2005 and Wamalwa 2009), pharmacy refill history (Berrien 2004), and MEMS (Muller 2009).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We identified two systematic reviews of interventions to improve adherence to ART among children and youth with HIV (Simoni 2007, Reisner 2009), one of which targeted interventions for 13‐24 year olds in the U.S.A. Only one randomised controlled trial was identified in these reviews, and we have included it in this review (Berrien 2004). The other studies included in the reviews consisted primarily of pre‐post evaluations with no control group. A number of interventions were identified that showed promise, but these interventions need to be evaluated using more rigourous study designs.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence that medication diaries are not effective in improving adherence or other biological outcomes. Only one intervention, a home‐based nursing intervention (Berrien 2004), demonstrated a clear effect on improving adherence. The other interventions evaluated in this review, including peer support groups for adolescents (Funck‐Brentano 2005) and an LPV/r regimen (Muller 2009), demonstrated improved clinical outcomes but no effect on adherence. More research should be conducted on interventions to address paediatric adherence, including the interventions identified here.

There is a clear need for more rigorous research on interventions to improve paediatric adherence to ART. Randomised clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Deanna McLeod and her team at Kaleidoscope Strategic for conducting the initial search and data extraction. We would also like to thank the team at WHO and CDC who guided us in protocol development and data interpretation.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Example of PubMed search strategy

Example of PubMed search strategy, modified as appropriate for use in the other databases.

(HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw]) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR (acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR "sexually transmitted diseases, viral"[MH] OR AIDS)

AND

("Adolescent"[Mesh] OR "Child"[Mesh] OR "Infant"[Mesh] OR “pediatric”[tw] OR ”paediatric”[tw] OR “adolescent”[tw] OR “teen”[tw] OR “infant”[tw])

AND

("Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active"[Mesh] OR "Anti‐Retroviral Agents"[Mesh] OR "antiretroviral"[tw] OR “ART”[tw] OR "medication"[tw])

AND

("Medication Adherence"[Mesh] OR "Guideline Adherence"[Mesh] OR "Patient Compliance"[Mesh] OR “adherence”[tw] OR “compliance”[tw])

Differences between protocol and review

None

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT Setting: Outpatient clinic (Connecticut, USA) Adherence measures: Self‐report by caregiver and/or subject (10 questions for a maximum score of 37) Pharmacy drug refill history (scored 0‐3) 3 points for monthly refill 2 points for somewhat less than monthly refill 1 point for much less often than monthly 0 points for never |

|

| Participants | Children and youth Mean age: 10 years (range 1.5‐20) Female: 55% Hispanic: 50% African American: 35% Caucasian: 15% HIV disclosure to child: 30% |

|

| Interventions | Eight structured home visits over a three month period designed to improve knowledge and understanding of HIV infection, to identify and resolve real and potential barriers to medication adherence and ultimately to improve adherence. Control group received standard medication adherence education, including visual aids, medication boxes, beepers, emotional support and one home visit. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported adherence (maximum 37 points) Intervention group (n=19): Mean pre‐test score 32.2 Mean post‐test score 34.8 Difference 2.7 Control group (n=15): Mean pre‐test score 31.7 Mean post‐test score 31.9 Difference 0.2 p = 0.07 Pharmacy drug refill history (0‐3 points) Intervention group: 2.7 Control group: 1.7 p = 0.002 Viral load Intervention group: 0.45 log decrease Control group: 0.02 log decrease No p‐value reported |

|

| Notes | The study was conducted between April 2000 and April 2001. Partipation was offered to all eligible HIV‐infected patients followed in the paediatric and youth HIV programme. 67% (37/55) agreed to participate. Questionnaires measuring adherence were completed at the first study visit and then at the end of the intervention, a period of three months. HIV infection status was measured pre‐intervention, immediately post‐intervention (three months) and again at a period between six and 11 months after study initiation. The study started with 37 participants, but three dropped out or died (one in the intervention group and two in the control group). Analyses reported above excluded the participants lost to follow‐up, but intent‐to‐treat analyses did not change the results. One patient in the intervention group was naïve to ART and was started on ART and the beginning of the study. All others were receiving a three‐drug regimen, with the exception of one who was taking only two ART medications at the start of the study. This latter patient was put on triple therapy during the time of the study. Subjects in the control groups were more likely to be on public assistance and have parents with less than a high school education. They were likely to have more advanced disease according to CDC clinical classification, but not according to the CDC clinical and immune classifications. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients were randomised 1:1 to either the intervention or control group using the Small Table of Random Digits. The randomisation process was number based, with patient names not identified. The randomisation list was held by the clinical coordinator in a locked file. However, it was unclear if participants or investigators could have foreseen assignment. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It was not practical for an independent observer, different from the study nurse, to administer the questionnaires. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Three patients died or withdrew from the study, one from the intervention group and two from the control group. The participants lost to follow‐up were included in intent‐to‐treat analyses, assuming that those who withdrew had no change in adherence. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcome data described in the Methods section were included in the Results, with the exception of CD4 count and percentages. |

| Other bias | High risk | Sample size was small, participants were recruited from only one institution and 33% of those invited to participate refused. |

| Methods | Non‐randomised, 3‐arm controlled trial Setting: Paediatric university‐tertiary hospital (Paris, France) Adherence measures: Self‐reported problems with compliance: 5‐point perceived compliance area on the Perceived Treatment Inventory (PTI), where 1=low problems with compliance and 5=high problems with compliance Participants were followed for two years after study initiation. |

|

| Participants | Adolescents Mean age: 14.2 years (range 12.0‐17.4 years) Female: 63% Receiving ART: 90% Adherence considered not optimum by the medical team: 11% |

|

| Interventions | Adolescents met for a 90‐minute session once every 6 weeks for 26 months. The format was open‐ended. Participants were invited to determine their own focus themes for each meeting and encouraged to discuss their feelings spontaneously. The group was led by two therapists, a man and a woman, both trained in psychodynamic and family therapy. | |

| Outcomes | Compliance area on PTI Intervention (group 1) Baseline: 1.0 (1‐2) Change at T2: 0 (‐1 to 0) Control, refused to participate (group 2) Baseline: 1.0 (1‐2) Change at T2: 0 (‐1 to 0) Control, not invited to participate (group 3) Baseline: 1.0 (1‐4) Change at T2: 0 (‐2 to 4) Viral load Intervention (group 1) Percent of participants with viral load ≤200 copies/mL at baseline: 30% Percent at T2: 80% (P=0.063) Control (group 2) Percent at baseline: 33% Percent at T2: 56% (not statistically significant) Control (group 3) Percent at baseline: 50% Percent at T2: 50% CD4 cell count: No significant change was observed in any group (data not shown) |

|

| Notes | The main objective of the study was to measure the effect of the intervention on various psychosocial measures, of which compliance to therapy was a small part. Inclusion criteria included: (1) HIV infection either by mother‐to‐child transmission or perinatal transfusion; (2) name of the virus and transmission route known by the patient; (3) evidence of self motivation to participate in a peer support group; (4) no previous participation in a therapy group and (5) adolescent's and guardian's agreement to participate in the study. Of 48 HIV‐infected adolescents being followed in the clinic during the study period, 38 met the inclusion criteria, and 23 were invited to participate. Of those, 10 self‐selected to participate in the intervention (group 1) and 13 declined (group 2). Reasons for declining were not systematically discussed, but the main reason was denial of any problem or needs for group therapy. The remaining 15 were not invited to participate because they lived to far from the clinic to participate in the support groups. They were nevertheless followed up and were included as a comparison group (group 3). Only adolescents who participated at both time points (baseline and 2 years follow‐up) were considered in the analyses; eight adolescents were excluded for this reason. 10% of subjects were not on ART. Details of the regimens were not reported. During the 26 months of the intervention, the number of adolescents fluctuated from one session to the next. Recently referred adolescents fulfilling the selection criteria joined the group after its initiation, and adolescents were allowed to withdraw at any time on the condition that they explain why. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | The groups self‐selected and were not randomised. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Neither participants nor investigators were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Although baseline data were collected for a total of 38 participants, follow‐up data were not available for eight (3 in Group 2 and 5 in Group 3), so these were excluded from the analysis. As reported in Table 3, which included compliance, Group 1 baseline data were available for eight of 10 participants and follow‐up data were available for seven; Group 2 baseline data were available for 10 of 10 participants and follow‐up data were available for nine; Group 3 baseline and follow‐up data were available for all 10. As reported in Table 4, viral load data were available at both time points for 10 (Group 1), nine (Group 2) and 10 (Group 3) participants. No reason is given for the missing data, although the Methods reports that psychological questionnaires missing more than 10% of the items were excluded from analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Patient's adherence as subjectively perceived by the paediatrician was listed as a measure in the Methods section but was only reported at baseline. |

| Other bias | High risk | Selection bias was a clear problem, as participants self‐selected to participate in the intervention or not. |

| Methods | Non‐randomised, 3‐arm trial Setting: paediatric HIV clinic (Cape Town, South Africa) Adherence measures: Treatment adherence measured by MEMS every three months, and measured as >80%, >85%, >90%, and >95% in various analyses. Virological status measured every six months according to local protocols; virological suppression was defined as HIV RNA levels ≤50 copies/mL. Outcomes were measured over a two‐year period. |

|

| Participants | Children under age 10 Mean age: 51 months (standard deviation, 24) (age range not reported) Female: 40% Median time on ART: 28 months (interquartile range, 12‐38) |

|

| Interventions | Children received ART regimens based on several factors, including a history of exposure to nevirapine, receipt of concomitant tuberculosis therapy, age and date they began therapy. The three arms of the study included three different regimens: an LPV/r‐containing triple regimen with zidovudine, lamivudine, stavudine, or abacavir as the NRTI; unboosted ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs; and 2 NRTIs plus either nevirapine or efavirenz as the NNRTI. | |

| Outcomes | Percentage of children who achieved >80% adherence at 3 months: LPV/r‐containing regimen: 64% (25 of 39) Unboosted PI regimen: 100% (6 of 6) NNRTI‐containing regimen: 57% (12 of 21) p=0.781 comparing the LPV‐r‐containing regimen to the NNRTI‐containing regimen Percent of children who achieved viral load ≤50 copies/mL at three months: LPV/r‐containing regimen: 77% (30 of 39) Unboosted PI regimen: not reported NNRTI‐containing regimen: 33% (7 of 21) p=.002 comparing the LPV‐r‐containing regimen to the NNRTI‐containing regimen |

|

| Notes | All eligible patients attending the clinic between February and April 2006 were asked to participate. Inclusion criteria for the study were: children <10 years receiving ART with liquid drug formulations with a monthly amount of not over 600 mL for the MEMS‐monitored drug lamivudine or abacavir, with one identified caregiver responsible for medication administration. Children and caregivers were excluded from the study if the caregiver refused to participate or if the child had multiple caregivers or lived in an orphanage setting. Demographic and other differences between treatment arms at baseline were not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Participants were not randomised; treatment arm was determined by treatment history and age. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Neither the investigators nor the participants were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Of 78 children enrolled in the study, one was transferred to another treatment centre, one had a dysfunctional MEMS device, three reported incorrect MEMS use, and blood samples obtained from nine children were insufficient for virological analysis. (It was not reported which treatment arm these children were in.) The authors report that this leaves 66 in the final analysis, whereas in fact it should have left only 64. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported in the methods section were reported on in the results. |

| Other bias | High risk | The small sample size and short duration of follow‐up (three months) limits the findings, especially with respect to virological outcomes. |

| Methods | RCT Setting: paediatric wards and HIV clinic of a national hospital (Nairobi, Kenya) Adherence measures: Caregiver‐reported adherence, defined as being >95% if the caregiver reported never missing a dose or reporting only one missed dose in the past 30 days Children were followed for a median of 15 months (interquartile range, 2‐21). |

|

| Participants | Children and youth Median age: 4.7 years (interquartile range 2.3‐6.2) Female 52% |

|

| Interventions | Counselling plus medication diaries that were completed daily by caregivers for a period of 9 months. The diary sheets were in tabular form with the name of each medication appearing in a separate row. The caregiver was asked to place a tick mark in an empty box beside the name of the medication to indicate that the child had been given the medicine. | |

| Outcomes | Caregiver‐reported adherence Intervention: 85% reported no missed doses Control: 92% reported no missed doses (p=0.08) Mean weight‐for‐age z score at 9 months Intervention: ‐1.36 Control: ‐1.55 (p=0.407) Mean height‐for‐age z score at 9 months Intervention: ‐3.73 Control: ‐1.84 (p=0.79) Mean weight‐for‐height z score at 9 months Intervention: ‐0.24 Control: ‐0.35 (p=0.88) Mean CD4 cells/ul at 6 months Intervention: 585 Control: 664 (p=0.25) Mean HIV‐1 RNA log10 copies/mL at 6 months Intervention: 2.27 Control: 2.14 (p=0.33) |

|

| Notes | Inclusion criteria included: (1) children between the ages of 15 months and 12 years; (2) antiretroviral drug‐naïve; (3) moderate to severe HIV‐1 disease; (4) caregivers literate; (5) anticipated stay within Nairobi for at least one year post enrolment. Children were initiated on first‐line antiretroviral drug regimens consisting of two NRTI and one NNRTI, as per Kenya national guidelines. All analyses used intention‐to‐treat approach. A total of 115 children was enroled, of whom 99 were randomised. Of the 16 who were not randomised, four died before initiation of treatment, and 12 failed to return prior to randomisation. Only 90 children had any follow‐up information available. At baseline, children and their caregivers in the two study arms had similar characteristics except for parental use of ART and CD4 count and percentage. Children assigned to the diary arm had higher absolute CD4 count and percentage: median CD4 count of 340 cells/µL versus 158 (p=0.02). More parents in the control arm (10, or 22%, of 46 versus one, or 2%, of 53 in the diary arm) had used ART at baseline (p=0.001). |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Computer‐generated block randomisation was used to assign children to the intervention or control group. However, it is unclear if participants or investigators could have foreseen assignment. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analyses were done. Of 53 children randomised to the intervention arm, only 33 completed nine months follow‐up, 26 completed 15 months, 11 were lost to follow‐up, and nine died. Of 46 children randomised to the control arm, 34 completed nine months follow‐up, 29 completed 15 months, five were lost to follow‐up and seven died. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not examined, but all outcomes mentioned in the Methods section were reported in the Results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The two groups differed at baseline on CD4 count and proportion of parents whe reported prior use of ART themselves, but these were adjusted for in models. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baldassari 2002 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

| Bunupuradah 2006 | No control group. |

| Byakika‐Tusiime 2009 | No control group. |

| Calles 2000 | Intervention description only; no outcomes were reported. |

| Chiappetta 2009 | Taste‐masking study; adherence not measured as an outcome. |

| Davies 2008 | Reported determinants of adherence; not an intervention. |

| Dunn 1998 | Reports the development of guidelines; adherence not measured as an outcome. |

| Ellis 2006 | No control group. |

| Garvie 2007 | No control group. |

| Gaur 2008 | No control group. |

| Gigliotti 2001 | No control group. |

| Glikman 2007 | No control group. |

| Gous 2004 | Intervention description only; no outcomes were reported. |

| Hansudewechakul 2006 | No control group. |

| Inaka 2002 | Intervention description only; no outcomes were reported. |

| Kammerer 2006 | There was no intervention; the study examined factors related to adherence. |

| Kraisintu 2004 | There was no intervention; only a discussion of policy and practices. |

| la Porte 2009 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

| le Roux 2009 | The study reported on treatments for tuberculosis among HIV‐infected children, not on ART. |

| Lyon 2003 | No control group. |

| Marazzi 2006 | Reported rates of adherence; not an intervention. |

| McKinney 2007 | No control group. |

| Miah 2006 | Intervention description only; no outcomes were reported. |

| Myung 2007 | No control group. |

| Naar‐King 2006 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

| Naar‐King 2008 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

| Naar‐King 2009 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome; fewer than 40% of participants in the study were taking ART. |

| Naar‐King 2010 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome; fewer than 40% of participants in the study were taking ART. |

| Omo‐Igbinomwanhia 2004 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

| Parsons 2006 | No control group. |

| Puccio 2006 | No control group. |

| Purdy 2008 | No control group. |

| Rabkin 2004 | Intervention description only; no outcomes were reported. |

| Reisner 2009 | Review of literature; not original research. |

| Rivers 1992 | Review of literature; not original research. Also, the review does not focus on children and does not focus on treatment for HIV. |

| Roberts 2004 | No control group. |

| Rogers 2001 | No control group. |

| Rudy 2009 | No control group. |

| Schmalb 2004 | Qualitative data only; no quantitative data on adherence. |

| Shah 2007 | Review of literature; not original research. |

| Shingadia 2000 | No control group. |

| Simoni 2003 | Review of literature; not original research. Also, the review focused on adults and not children. |

| Simoni 2007 | Review of literature; not original research. |

| Sophan 2006 | No control group. |

| Temple 2001 | No control group. |

| van Griensven 2008 | No control group. |

| Van Winghem 2008 | No control group. Also, the article primarily describes the intervention without reporting outcomes. |

| Wilson 2009 | Adherence was not measured as an outcome. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Pediatric Impact |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Children ages 5‐12 years and their caregivers |

| Interventions | A tailored plan for each family consisting of medication management and swallowing, disclosure, education, behaviour change and referrals to other services |

| Outcomes | Adherence is measured by self‐report, provider assessment and MEMS. |

| Starting date | April 2003 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigators: Andrew Wiznia, MD; Tamara Rakusan, MD; Sohail Rana, MD |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00134602. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT00134602 |

Contributions of authors

DB Brickley: designing the review, screening search results, organizing retrieval of papers, screening retrieved papers against eligibility criteria, appraising quality of papers, extracting data from papers, entering data into RevMan, analysis of data, writing the review

LM Butler: designing the review, designing search strategies, writing the protocol, extracting data from papers, appraising quality of papers, analysis of data, performing previous work that was the foundation of the current review

GE Kennedy: coordinating the review, designing the review, providing general advice on the review

GW Rutherford: interpretation of data, providing general advice on the review

Sources of support

Internal sources

Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, USA.

External sources

World Health Organization, Switzerland.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA.

Declarations of interest

None to declare.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

- Berrien VM, Salazar JC, Reynolds E, McKay K. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV‐infected pediatric patients improves with home‐based intensive nursing intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs June 2004;18(6):355‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funck‐Brentano I, Dalban C, Veber F, Quartier P, Hefez S, Costagliola D, Blanche S. Evaluation of a peer support group therapy for HIV‐infected adolescents. AIDS Sept 2005;19(14):1501‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller AD, Myer L, Jaspan H. Virological suppression achieved with suboptimal adherence levels among South African children receiving boosted protease inhibitor‐based antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases Jan 2009;48(1):e3‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamalwa DC, Farquhar C, Obimbo EM, Selig S, Mbori‐Ngacha DA, Richardson BA, Overbaugh J, Egondi T, Inwani I, John‐Stewart G. Medication diaries do not improve outcomes with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Kenyan children: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the International AIDS Society June 2009;12(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review