Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) damages individuals, their children, communities, and the wider economic and social fabric of society. Some governments and professional organisations recommend screening all women for IPV rather than asking only women with symptoms (case‐finding). Here, we examine the evidence for whether screening benefits women and has no deleterious effects.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of screening for IPV conducted within healthcare settings on identification, referral, re‐exposure to violence, and health outcomes for women, and to determine if screening causes any harm.

Search methods

On 17 February 2015, we searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, six other databases, and two trial registers. We also searched the reference lists of included articles and the websites of relevant organisations.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of IPV screening where healthcare professionals either directly screened women face‐to‐face or were informed of the results of screening questionnaires, as compared with usual care (which could include screening that did not involve a healthcare professional).

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the trials and undertook data extraction. For binary outcomes, we calculated a standardised estimation of the odds ratio (OR). For continuous data, either a mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) was calculated. All are presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Main results

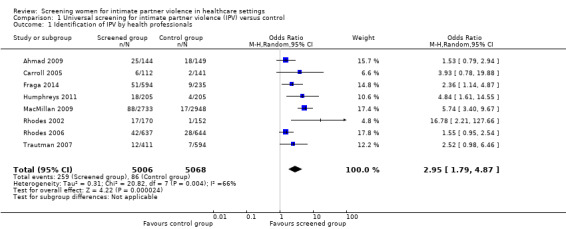

We included 13 trials that recruited 14,959 women from diverse healthcare settings (antenatal clinics, women's health clinics, emergency departments, primary care) predominantly located in high‐income countries and urban settings. The majority of studies minimised selection bias; performance bias was the greatest threat to validity. The overall quality of the body of evidence was low to moderate, mainly due to heterogeneity, risk of bias, and imprecision.

We excluded five of 13 studies from the primary analysis as they either did not report identification data, or the way in which they did was not consistent with clinical identification by healthcare providers. In the remaining eight studies (n = 10,074), screening increased clinical identification of victims/survivors (OR 2.95, 95% CI 1.79 to 4.87, moderate quality evidence).

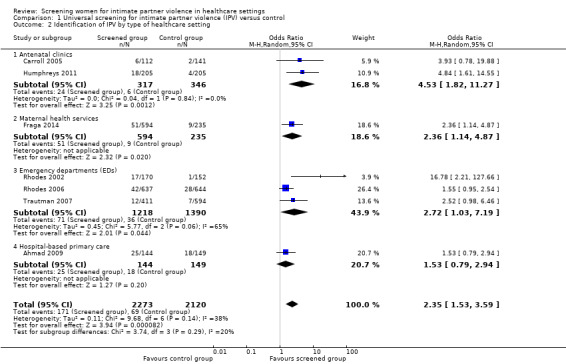

Subgroup analyses suggested increases in identification in antenatal care (OR 4.53, 95% CI 1.82 to 11.27, two studies, n = 663, moderate quality evidence); maternal health services (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.14 to 4.87, one study, n = 829, moderate quality evidence); and emergency departments (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.03 to 7.19, three studies, n = 2608, moderate quality evidence); but not in hospital‐based primary care (OR 1.53, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.94, one study, n = 293, moderate quality evidence).

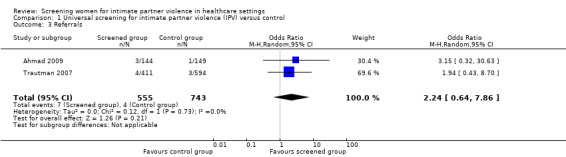

Only two studies (n = 1298) measured referrals to domestic violence support services following clinical identification. We detected no evidence of an effect on referrals (OR 2.24, 95% CI 0.64 to 7.86, low quality evidence).

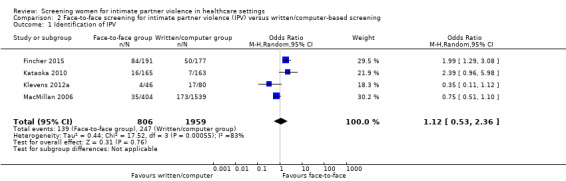

Four of 13 studies (n = 2765) investigated prevalence (excluded from main analysis as rates were not clinically recorded); detection of IPV did not differ between face‐to‐face screening and computer/written‐based assessment (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.36, moderate quality evidence).

Only two studies measured women's experience of violence (three to 18 months after screening) and found no evidence that screening decreased IPV.

Only one study reported on women's health with no differences observable at 18 months.

Although no study reported adverse effects from screening interventions, harm outcomes were only measured immediately afterwards and only one study reported outcomes at three months.

There was insufficient evidence on which to judge whether screening increases uptake of specialist services, and no studies included an economic evaluation.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence shows that screening increases the identification of women experiencing IPV in healthcare settings. Overall, however, rates were low relative to best estimates of prevalence of IPV in women seeking healthcare. Pregnant women in antenatal settings may be more likely to disclose IPV when screened, however, rigorous research is needed to confirm this. There was no evidence of an effect for other outcomes (referral, re‐exposure to violence, health measures, harm arising from screening). Thus, while screening increases identification, there is insufficient evidence to justify screening in healthcare settings. Furthermore, there remains a need for studies comparing universal screening to case‐finding (with or without advocacy or therapeutic interventions) for women's long‐term wellbeing in order to inform IPV identification policies in healthcare settings.

Plain language summary

Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings

Background

We carried out this review to find out if asking (screening) all women attending healthcare settings about their experience of domestic violence from a current or previous partner helps to recognise abused women so that they may be provided with a supportive response and referred on to support services. We were also interested to know if this would reduce further violence in their lives, improve their health, and not cause them any harm compared to women's usual healthcare.

Women who have experienced physical, psychological, or sexual violence from a partner or ex‐partner suffer poor health, problems with pregnancy, and early death. Their children and families can also suffer. Abused women often attend healthcare settings. Some people have argued that healthcare professionals should routinely ask all women about domestic violence. They argue that 'screening' might encourage women who would not otherwise do so, to disclose abuse, or to recognise their own experience as 'abuse'. In turn, this would enable the healthcare professional to provide immediate support or refer them to specialist help, or both. Some governments and health organisations recommend screening all women for domestic violence. Others argue that such screening should be targeted to high‐risk groups, such as pregnant women attending antenatal clinics.

Study characteristics

We examined research up to 17 February 2015. We included research studies that had women over 16 years of age attending any healthcare setting. Our search generated 12,369 studies and we eventually included 13 studies that met the criteria described above. In all, 14,959 women had agreed to be in those studies. Studies were in different healthcare settings (antenatal clinics, women's health/maternity services, emergency departments, and primary care centres). They were conducted in mainly urban settings, in high‐income countries with domestic violence legislation and developed support services to which healthcare professionals could refer. Each of the included studies was funded by an external source. The majority of the funding came from government departments and research councils, with a small number of grants/support coming from trusts and universities.

Key results and quality of the evidence

Eight studies with 10,074 women looked at whether healthcare professionals asked about abuse, discussed it, and/or documented abuse in participating women's records. There was a twofold increase in the number of women identified in this way compared to the comparison group. The quality of this evidence was moderate. We looked at smaller groups within the overall group, and found, for example, that pregnant women were four times as likely to be identified by a screening intervention as pregnant women in a comparison group. We did not see an increase in referral behaviours of healthcare professionals but only two studies measured referrals in the same way and there were some shortcomings to these studies. We could not tell if screening increased uptake of specialist services and no studies examined if it is cost‐effective to screen. We also looked to see if different methods were better at picking up abuse, for example, you might expect that women would be more willing to disclose to a computer, but we did not find one method to be better than another. We found an absence overall of studies examining the recurrence of violence (only two studies looked at this, and saw no effect) and women's health (only one study looked at this, and found no difference 18 months later). Finally, many studies included some short‐term assessment of adverse outcomes, but reported none.

There is a mismatch between the increased numbers of women picked up through screening by healthcare professionals and the high numbers of women attending healthcare settings actually affected by domestic violence. We would need more evidence to show screening actually increases referring and women's engagement with support services, and/or reduces violence and positively impacts on their health and wellbeing. On this basis, we concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend asking all women about abuse in healthcare settings. It may be more effective at this time to train healthcare professionals to ask women who show signs of abuse or those in high‐risk groups, and provide them with a supportive response and information, and plan with them for their safety.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Intimate partner violence (IPV)

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a violation of a person's human rights and is now recognised as a global public health issue. For the purpose of this review, we adopt the definition of IPV (often termed domestic violence) of the World Health Organization (WHO), that is, any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm to those in the relationship (Krug 2002; WHO 2013a). Intimate partner violence often involves a combination of abuse behaviours. These include threats of and actual physical violence, sexual violence, emotionally abusive behaviours, economic restrictions, and other controlling behaviours. Many survivors of IPV report that the physical violence is not the most damaging: it is the relentless psychological abuse that leaves the person with long‐lasting adverse effects (Campbell 2002; WHO 2013b).

Intimate partner violence against men is a social problem with potential adverse outcomes for victims (Coker 2002). Data from the British Crime Survey suggested that 4.4% of men experienced IPV in the 2012/13 period compared to 7.1% of women (Office for National Statistics 2014). In this review, however, we do not include IPV against men because the majority of abuse with serious health and other consequences is that committed by men against their female partners (Coker 2002), with women being three times more likely than men to sustain serious injury and five times more likely to fear for their lives (CCJS 2005), which is why most screening interventions target women (Taft 2001). We also exclude abuse towards women that is perpetrated by other family members such as in‐laws or children. We do include in this review, women who experience violence by female partners, and by ex‐partners given the increased risks of violence associated with separation (Wilson 1993; Campbell 2004; WHO 2013a).

Prevalence of IPV

Abuse of women by their partners or ex‐partners is a common worldwide phenomenon (Garcia‐Moreno 2006). Latest figures from the WHO indicate that one in three women globally experiences physical or sexual violence, or both, by a partner, or non‐partner sexual violence, in their lifetime (WHO 2013a). Based on 48 population‐based surveys across low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries, the 2002 World Report on Violence and Health revealed rates of between 10% and 69% for lifetime physical violence by a partner (Krug 2002). Definitions used in prevalence studies ranged from physical abuse in current relationships to the inclusion of physical, emotional, sexual, or a combination of abuses in past relationships (Hegarty 2006). Estimates of the magnitude of IPV are obtained from community surveys, clinical samples, and public records. Discrepancies in prevalence rates arise from differences in definitions of IPV, sensitivity of tools, modes of data collection, reporting time frames, and risk variation in the populations sampled (WHO 2013a).

Impacts of IPV

Intimate partner violence can have short‐term and long‐term negative health consequences for survivors, even after the abuse has ended (Campbell 2002). World Development reports (World Bank 2006) and statements from the United Nations (Ingram 2005) emphasise that IPV is a significant cause of death and disability on a worldwide scale (Ellsberg 2008), and the WHO highlights violence against women as a priority health issue (WHO 2013a). The high incidence of psychosocial, physical, sexual, and reproductive health problems in women exposed to IPV leads to frequent presentations at health services and the need for wide‐ranging health services (Bonomi 2009). In addition, IPV is associated with enormous economic and social costs, including those related to social, criminal justice, housing and health services, lost productivity, and human suffering (CDC 2003; Walby 2004; EIGE 2014).

Psychosocial health

The most prevalent mental health sequelae of IPV for female victims are depression, anxiety, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use (Golding 1999; Hegarty 2004; Rees 2011; Trevillion 2012; WHO 2013a), and women often suffer from low self esteem and hopelessness (Kirkwood 1993; Campbell 2002). Suicide and attempted suicide are also associated with IPV in both industrialised and non‐industrialised countries (Golding 1999; Ellsberg 2008; WHO 2013a). Moreover, these effects impact detrimentally on women's ability to parent and thus impact on their children (McCosker‐Howard 2006). Exposure to IPV during childhood has been linked with poor emotional, social, and attainment outcomes (Kitzmann 2003), with around six in 10 IPV‐exposed children exhibiting difficulties. Early exposure to interparental violence has also been associated with increased risk of IPV perpetration or victimisation during adolescence and adulthood (Heyman 2002).

Physical health

Abused women often experience many chronic health problems (WHO 2013a), including chronic pain and central nervous system symptoms (Díaz‐Olavarrieta 1999; Campbell 2002), self reported gastrointestinal symptoms, diagnosed functional gastrointestinal disorders (Coker 2000), and self reported cardiac symptoms (Tollestrup 1999). Intimate partner violence is also one of the most common causes of injury in women (Stark 1996; Richardson 2002), including oral‐maxillofacial trauma treated in dental, emergency, and surgical settings (Clark 2014; Ferreira 2014; Wong 2014). Over 50% of all female murders in the UK and USA are committed by partners or ex‐partners (Brock 1999; Shackelford 2005; Home Office 2010). Worldwide, 38% of female homicides are perpetrated by partners (WHO 2013a). In Australia, as elsewhere, a far higher percentage of indigenous compared with non‐indigenous women are murdered by their partners (Mouzos 2003).

Sexual and reproductive health

The most consistent and largest physical health difference between abused and non‐abused women is the experience of gynaecological symptoms (McCauley 1995; Campbell 2002). Women and their fetuses and babies are also at risk, before, during, and after pregnancy (Martin 2001; Silverman 2006). The most serious outcome is the death of the mother or the fetus (Jejeebhoy 1998; Parsons 1999). Violence by a partner is also associated with high rates of pregnancy at a young age (Moore 2010), miscarriage and abortion (Taft 2004; Pallitto 2013), low birth weight (Murphy 2001), and premature birth and fetal injury (Mezey 1997). High rates of symptoms of antenatal and postnatal depression, anxiety, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are also associated with exposure to IPV during adulthood and pregnancy (Howard 2013).

Description of the intervention

Interventions by healthcare practitioners to improve the health consequences for women experiencing IPV

Healthcare services play a central role in abused women's care (García‐Moreno 2014), but the quality of healthcare professionals' responses has been a focus of concern since the 1970s (Stark 1996; Feder 2006). Over the last few decades there has been a concerted effort by women's and justice organisations and the voluntary sector to respond to the needs of women who have experienced IPV. In contrast, the response of health services has been slow (Feder 2009). While most health professionals believe that IPV is a healthcare issue (Richardson 2001), there are a number of barriers to identification and response on the part of practitioners (Hegarty 2001). These include a perceived lack of time and support resources, fear of offending the woman, a lack of knowledge and training about what to do for the woman, and a belief that the woman will not leave the abusive relationship (Waalen 2000). A further barrier is the lack of evidence for effective interventions (García‐Moreno 2014).

Despite these barriers, there has been progress in the overall response of health systems to IPV with many health professional associations around the world publishing guidelines for clinicians on how to identify women who have been abused (Davidson 2000; Family Violence Prevention Fund 2004; Hegarty 2008). Implicit in many of these recommendations is the assumption that screening or asking routinely about abuse will increase identification of women who are experiencing violence, lead to appropriate interventions and support, and ultimately decrease exposure to violence and its detrimental health consequences, both physical and psychological (Taft 2004; WHO 2013b). Screening is predicated on the assumptions that identifying and responding supportively to, and referring on, women experiencing IPV is fulfilling health professionals' duty of care. However, advocacy or ongoing therapy requires appropriate training and time that clinicians may not have in routine care. Further, clinicians are part of a wider system of response and need to be able to identify and refer to domestic violence services that have more time, and have specialist training and connections to other community‐based services such as housing. Training and knowledge of referral services should improve clinicians' motivation to identify when they are not responsible for ongoing domestic violence counselling and advocacy. This review, an update of an earlier review (Taft 2013; O'Doherty 2014a), is focused on screening with a brief response only; it does not include advocacy or psychotherapeutic interventions, which are the topics of separate reviews.

Screening

Screening aims to identify women who have experienced, or are experiencing, IPV from a partner or ex‐partner in order to offer interventions leading to beneficial outcomes. However, within the field of domestic/family violence, both the immediate‐ and longer‐term benefit of screening such women remains unproven (Taket 2004; Spangaro 2009; WHO 2013b), despite some recommendations for screening in particular countries (e.g. USA) (Nelson 2012). Many factors, such as fear or readiness to take action, influence whether or not women choose to disclose their abuse (Chang 2010), and will affect accurate measurement of screening rates. Screening for IPV, therefore, is a problematic concept when traditional screening criteria are applied (Hegarty 2006), as it is a complex social phenomenon rather than a disease. However, it still requires rigorous evidence for its effectiveness if it is to be implemented as policy.

It is important to distinguish between universal screening (the application of a standardised question to all symptom‐free women according to a procedure that does not vary from place to place), selective screening (where high‐risk groups, such as pregnant women or those seeking pregnancy terminations are screened), routine enquiry (when all women are asked but the method or question varies according to the healthcare professional or the woman's situation), and case‐finding (asking questions if certain indicators are present).

For this review, screening is defined as any method that aims for every woman patient in a healthcare setting to be asked about her experiences of IPV, both past and present. Screening may be conducted directly by a healthcare professional or indirectly through a self completed questionnaire (often by computer) with the healthcare professional informed of the questionnaire results. This may include the use of screening tools (Rabin 2009), which vary in their validity and reliability and therefore in their effectiveness to accurately detect abuse. These tools are reviewed in CDC 2007 and Feder 2009. Alternatively, clinicians may ask one or a range of questions related to IPV only at one time point or at several. It is very unlikely that one single question will address the range of women's experiences of IPV. Whether a woman is currently experiencing IPV from a current partner or an ex‐partner (e.g. harassment) or has previously experienced IPV, the goal of screening is the same ‐ to identify her and offer support appropriate to her needs that will prevent any further abuse (e.g. advocacy, legal or police help) and reduce any consequent problems she is experiencing (e.g. offering therapeutic support) or a combination of these.

There has long been debate about the value of screening per se (Taket 2004; Feder 2009), with some arguing that asking questions can raise awareness in women experiencing IPV who are contemplating their situation. Generally, most women are in favour of universal screening, although this varies with abuse status and age (Feder 2009). However, studies have found that women's preferences vary according to the method of screening used (MacMillan 2006; Feder 2009); readers are referred to several studies that have examined this question but were excluded from this review (Furbee 1998; Bair‐Merritt 2006; Chen 2007; Rickert 2009). Bair‐Merritt 2006 found a similar rate of disclosure in audiotaped (11%) compared with written questionnaires (9%) with both methods preferred to direct physician enquiry. Chen 2007 found that there was little difference between self completion and healthcare professional enquiry in terms of participant comfort, time taken, and effectiveness, but that women who had experienced IPV were less comfortable with physician screening. MacMillan and colleagues reported that women found self completion methods easier and more private and confidential (MacMillan 2006). However, women's preferences for how they are asked about IPV needs to be examined in the context of outcomes beyond disclosure. In other words, self interview methods may yield higher disclosure rates, but does this translate into increased awareness about IPV, better uptake of services, reduced re‐exposure to IPV, and improvements in health?

Identifying IPV is only the first step in intervention. Among women receiving care in US primary care clinics, Klevens 2012b tested computer‐assisted screening accompanied by a brief video in which an advocate provided support and information and encouraged women to seek help and referral information versus no screening with referral information only, versus usual care. One year later they found no difference between the three groups in physical or mental health status. Women may have experienced long‐standing abuse or it may have commenced recently; they may be unaware that the behaviour constitutes abuse or be actively seeking support for change, and therefore responses to their needs may need to differ (Chang 2010; Reisenhofer 2013), and may require involvement of a healthcare professional rather than a list of resources.

Two reviews of studies addressing the UK National Screening Committee criteria found that screening by healthcare professionals leads to a modest increase in the number of abused women being identified following screening, but that screening was not acceptable to the majority of health professionals surveyed (Ramsay 2002; Feder 2009). Hegarty 2006 outlines the many clinician barriers (e.g. time, lack of ongoing or effective training and resources) and system barriers (e.g. different health priorities, lack of referral options in the community) that impede effective screening and routine enquiry, and that need to be addressed before clinicians will feel comfortable asking women about their experiences of abuse. In addition, women experience barriers to disclosure, especially during pregnancy, with the presence of abusive partners or monitoring of her attendance at healthcare services where she might disclose. Most reviews to date have concluded that there is no evidence that women experience better outcomes from screening interventions (Ramsay 2002; Wathen 2003; Taft 2013). This lack of evidence has not deterred many governments around the world implementing universal IPV screening, or selective screening in high‐risk populations. Previous US and Canadian Task Forces on Preventive Health Care conducted thorough systematic reviews of the evidence and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for violence against women (Wathen 2003; Nelson 2004); however, the US Preventive Services Task Force revised their decision (Nelson 2012) and now recommend screening based on scant evidence from one effectiveness study (MacMillan 2009). The WHO reviewed the evidence in 2013 and recommended screening women only when they are pregnant (WHO 2013b). In some countries, screening is advocated in the absence of sufficient resources or referral options, and where there is a lack of training and resources, clinicians may undertake screening inappropriately. Some would further argue that it is unethical to implement screening for IPV in the absence of evidence of effectiveness as it may cause harm (Jewkes 2002; Wathen 2012).

How the intervention might work

Universal screening aims for 100% of women to be asked about IPV and those experiencing IPV to disclose it. Universal screening may apply to all women in a healthcare setting, such as a hospital, while selective screening could be applied to those in high‐risk groups such as those in antenatal or abortion clinics or pregnant women attending community‐based family practice clinics. Screening women using face‐to‐face methods implies the clinician is directly asking all women who attend for a given consultation whether they are experiencing or have ever experienced abusive behaviours from their partner or ex‐partner, providing women with the choice to disclose or not. Women who disclose abuse may then be offered a response such as safety assessment and planning, emotional support, referral to specialist services, or information on appropriate local/national resources. Another model might offer all women attending a given health service the option of self completing screening (through written or computer‐based methods) where a woman can choose whether or not to disclose abusive behaviour from a partner or ex‐partner. Positive screen results would then be assessed by the consulting healthcare professional who could exercise their own clinical judgement in how to respond to a positive result. The option of administrative or computerised follow‐up has been explored where the clinician is bypassed, and instead, for example, a print‐out of resources is generated. Klevens and colleagues found no effect of this type of screening intervention on outcomes for women (Klevens 2012b).

Why it is important to do this review

This review was originally published two years ago (Taft 2013). However, the international debate on whether or not screening in healthcare settings is beneficial to women has continued. Given that the evidence presented in the previous review was appraised as low to moderate quality and there were few studies that examined medium‐ and long‐term health and abuse outcomes, it is important to search for and synthesise new research and, where possible, combine studies of similar outcomes in a meta‐analysis. We have incorporated another review 'Domestic violence screening and intervention programmes for adults with dental or facial injury' into this update (Coulthard 2010), please see section on Differences between protocol and review. The reasons for doing this work have not changed since the original review. There is an urgent need to assess and identify health sector screening interventions for IPV (Davidson 2000; Feder 2009), in order to: have clear evidence about what health professionals can do safely and effectively to decrease the impact of IPV on women; determine what is cost‐effective; and inform health professionals and policy‐makers about the cost/benefit of screening interventions. In particular, this systematic review examines the most rigorous evidence around health service screening interventions for IPV to ascertain whether the potential benefits of IPV screening for women's health and wellbeing outweigh any potential for harm.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of screening for IPV conducted within healthcare settings on identification, referral, re‐exposure to violence, and health outcomes for women, and to determine if screening causes any harm.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any study that allocated individual women, or clusters of women, by a random or quasi‐random method (such as alternate allocation, allocation by birth date, etc.) to a screening intervention compared with usual care or to a condition where healthcare professionals were not aware of women's screening results.

Types of participants

Women (aged 16 years and over) attending a healthcare setting. We define a 'healthcare setting' as any health setting where health services are delivered (such as those listed below), and home visits by these services.

General (family) practice

Antenatal and postnatal services

Hospital emergency, inpatient or outpatient services

Private specialists (e.g. obstetrics and gynaecology, psychiatry, ophthalmology)

Community health services

Drug and alcohol services

Mental health services

Dental services

Types of interventions

Any IPV screening in a healthcare setting as listed above. Screening is defined as any of a range of methods (face‐to‐face, survey or other method, specific to IPV or where IPV was included as part of general psychosocial screening) that aims for all women patients in a healthcare setting to be asked about current or past IPV, including the use of screening tools as well as asking one or a range of screening questions related to IPV on one or more occasions. We only included studies where, in one arm of the trial, the treating healthcare professional conducted the screening or was informed of the screening result at the time of the relevant consultation.

We excluded extended interventions that went beyond screening and an immediate response to disclosure, for example, interventions that include clinical follow‐up or offer further counselling or psychological treatment. We made this an exclusion factor as it is rarely feasible for health professionals to deliver intensive treatments due to lack of time and skill. Furthermore, we wanted to isolate the effect of screening in order to provide evidence on the independent contribution of this particular response to IPV.

Screening was compared to usual care, implying no screening in the comparative arm. However, we did include studies where an eligible screening intervention was compared to a condition of 'screening' that involved no healthcare professionals or face‐to‐face interaction.

Types of outcome measures

We did not use outcomes measured by studies as a criterion for inclusion or exclusion.

Primary outcomes

A. Identification of IPV by health professionals (data based on clinical encounter).

Identification was defined as any form of acknowledgement by a healthcare professional during a consultation that the woman had experienced exposure to IPV. Identification therefore assumes communication between healthcare professional and participant that acknowledges the abuse. Studies use different terms such as identification, discussion, and patient disclosure of IPV. We carefully assessed how stated outcomes were operationalised across trials in order to determine if they met our definition of identification. Studies could collect identification data using a variety of methods (e.g. audio‐recordings of encounters, surveying women and healthcare professionals about what was discussed during the encounter, and medical record review). Identification of IPV through face‐to‐face interviews with researchers was dealt with separately on the basis that it did not properly represent the clinical context and may threaten the validity of the primary identification data.

B. Information‐giving and referrals to support agencies by healthcare professionals (including take‐up rates when available).

We included in this category any recording, documentation or organisational validation that women had been given information about, or referral to, support agencies.

Secondary outcomes

C. Intimate partner violence as measured by:

validated instruments (e.g. Composite Abuse Scale (CAS), Index of Spouse Abuse (ISP); and

self reported IPV, even if using a non‐validated scale.

D. Women's perceived and diagnosed physical health outcomes, using measures of:

physical health (e.g. Short‐Form health survey ‐ 36 (SF‐36) physical subscale, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ));

physical injuries, such as fractures and bruises (self reported or documented in medical records); and

chronic health disorders, such as gynaecological problems, chronic pain, and gastrointestinal disorders (self reported or clinical symptoms, or both, documented in medical records).

E. Women's psychosocial health, using measures of:

depression (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D));

post‐traumatic stress (e.g. Impact of Events Scale (IES), Post‐traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL));

anxiety (e.g. Spielberger's State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI));

self efficacy (e.g. Generalized Perceived Self‐Efficacy Scale (GSE), Sherer's Self‐Efficacy Scale (SES));

self esteem (e.g. Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale (SES), Coopersmith Self‐Esteem Inventory (CSEI));

quality of life (e.g. WHO Quality of Life‐Bref)

perceived social support (e.g. Medical Outcomes Scale (MOS), Sarason's Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ)); and

alcohol or drug abuse (e.g. Addiction Severity Index (ASI), Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse (AOD) scale).

F. Occurrence of adverse outcomes such as:

increased deaths, all‐cause or IPV‐related (documented in medical records or routinely collected data);

increase of IPV as measured by any of the above;

increase of physical or psychosocial morbidity as listed above; and

false negatives and false positives of screening tests.

G. Services and resource use:

family/domestic violence services;

police/legal services;

counselling or therapeutic services;

health service use; and

other services.

H. Cost/benefit outcomes, using measures of:

health service use;

days out‐of‐role; and

medication use.

Timing of outcome assessment

We documented the duration of follow‐up in all included studies. For the purposes of this review, we defined short‐term follow‐up as less than six months since baseline or delivery of the screening intervention, medium‐term follow‐up as between six and 12 months, and long‐term follow‐up as more than 12 months.

Selecting outcomes for 'Summary of findings' table

We included the results of outcomes that could be pooled together in a meta‐analysis in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1 and Table 2). These were the primary outcomes of clinical identification of IPV, and referral. We also included an outcome that was not indicated a priori, an alternative identification outcome, which we refer to as non‐clinical identification (these data were not drawn from documentation of abuse; medical records etc. within the clinical context) (see Differences between protocol and review).

for the main comparison.

| Screening for intimate partner violence (IPV) compared with usual care or screening without health professional involvement | ||||||

| Patient or population: women attending healthcare settings for any health‐related reason Settings: healthcare Intervention: face‐to‐face screening or written/computerised screening with result passed to the healthcare professional Comparison: non‐screened women or those whose screening result was not passed on to the healthcare professional or those screened for issues other than IPV | ||||||

| Outcomes | Universal screening for IPV | Control | Effect | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Relative effect (95% CI) | Absolute effect (95% CI) | |||||

| Identification of IPV by health professionals (assessed immediately or up to 1 month) | 259/5006 (5.2%) | 86/5068 (1.7%) | OR 2.95 (1.79 to 4.87) | 31 more per 1000 (from 13 more to 61 more) | 10,074 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 |

| 1.7% | 31 more per 1000 (from 13 more to 60 more) | |||||

| Identification of IPV by type of healthcare setting ‐ Antenatal clinics | 24/317 (7.6%) | 6/346 (1.7%) | OR 4.53 (1.82 to 11.27) | 57 more per 1000 (from 14 more to 149 more) | 663 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 |

| 1.7% | 55 more per 1000 (from 13 more to 145 more) | |||||

| Identification of IPV by type of healthcare setting ‐ Maternal health services | 51/594 (8.6%) | 9/235 (3.8%) | OR 2.36 (1.14 to 4.87) | 48 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 124 more) | 829 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

| 3.8% | 48 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 124 more) | |||||

| Identification of IPV by type of healthcare setting ‐ Emergency departments | 71/1218 (5.8%) | 36/1390 (2.6%) | OR 2.72 (1.03 to 7.19) | 42 more per 1000 (from 1 more to 135 more) | 2608 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 |

| 1.2% | 20 more per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 67 more) | |||||

| Identification of IPV by type of healthcare setting ‐ Hospital‐based primary care | 25/144 (17.4%) | 18/149 (12.1%) | OR 1.53 (0.79 to 2.94) | 53 more per 1000 (from 23 fewer to 167 more) | 293 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

| 12.1% | 53 more per 1000 (from 23 fewer to 167 more) | |||||

| Referrals (assessed immediately) | 7/555 (1.3%) | 4/743 (0.5%) | OR 2.24 (0.64 to 7.86) | 7 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 35 more) | 1298 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 |

| 0.6% | 7 more per 1000 (from 2 fewer to 39 more) | |||||

| CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; IPV: intimate partner violence; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded due to heterogeneity. 2Downgraded due to imprecision. 3Downgraded due to risk of bias. 4Downgraded due to imprecision and risk of bias.

2.

| Face‐to‐face screening compared with written/computer‐based screening for IPV | |||||||

|

Patient or population: women attending healthcare settings for any health‐related reason Settings: healthcare Intervention: face‐to‐face screening for IPV Comparison: written/computer‐based screening | |||||||

| Outcomes | Face‐to‐face screening for IPV | Written/computer‐based screening | Effect | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Relative effect (95% CI) | Absolute effect (95% CI) | ||||||

|

Identification of IPV (non‐clinically based, assessed immediately) |

139/806 (17.2%) | 247/1959 (12.6%) | OR 1.12 (0.53 to 2.36) | 13 more per 1000 (from 55 fewer to 128 more) | 2765 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | |

| 24.8% | 22 more per 1000 (from 99 fewer to 190 more) | ||||||

| CI: Confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; IPV: intimate partner violence; OR: odds ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

1Downgraded due to heterogeneity.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the international literature for peer‐reviewed and non‐peer‐reviewed studies and published and unpublished studies. We did not apply any date or language restrictions to our search strategies. We chose not to use a randomised controlled trial (RCT) filter as we wanted the search to be as inclusive as possible; an initial check of the differences between using and not using a RCT filter uncovered a trial not captured when the RCT filter was applied. Our previous search strategies were not limited to any healthcare setting, and so did not require any revisions as they already captured records relevant to oral and maxillofacial injury clinics. The previous version of this review included studies up to July 2012. The searches for this update cover the period from 2012 to 17 February 2015.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 17 February 2015.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2015, Issue 1), which includes the Specialised Register of the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group (CDPLPG).

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to February Week 2 2015.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In–process and other non‐indexed citations 13 February 2015.

Embase (Ovid) 1980 to 2015 Week 7.

CINAHL PLUS (EBSCOhost) 1937 to current.

PsycINFO (Ovid) 1806 to February Week 2.

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest) 1952 to current.

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science and Humanities (CPCI‐SS&H; Web of Science) 1990 to 17 February 2015.

Database of Abstracts of Reviews for Effectiveness (DARE) 2012, Issue 2, part of the Cochrane Library.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) 2015, Issue 2, part of theCochrane Library.

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (who.int/ictrp/en/).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

The search strategies used for this update are in Appendix 1. Search strategies used for earlier versions of the review are in Appendix 2. The searches were originally run by Joanne Abbott, former Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) of CDPLPG. Subsequent searches were conducted by Margaret Anderson, current TSC of CDPLPG.

We also searched the website of the World Health Organization (WHO) (who.int/topics/violence/en/) and the Violence Against Women (VAW) Online Resources (vaw.umn.edu/).

Searching other resources

Handsearching

Due to insufficient resources, we were unable to undertake planned handsearching of the Journal of Family Violence, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Violence and Victims, Women's Health, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, American Journal of Public Health, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Archives of Internal Medicine, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, and Journal of the American Medical Association. We are confident that any major screening trials involving healthcare professionals would have been identified through our other search strategies, including our electronic searches and searches of trials registers, citation tracking, networks of the review authors, and communication with authors of included studies.

Citation tracking

We examined the reference lists of acquired papers and tracked citations forwards and backwards.

Personal communication with the first authors of all included articles

We emailed the authors of all primary studies included in the review about any omissions (and, in particular omissions of non‐peer‐reviewed studies). We contacted the WHO Violence and Injury Programme to inquire about any screening studies that might fit our inclusion criteria of which we were unaware, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries (García‐Moreno 2015 [pers comm]).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

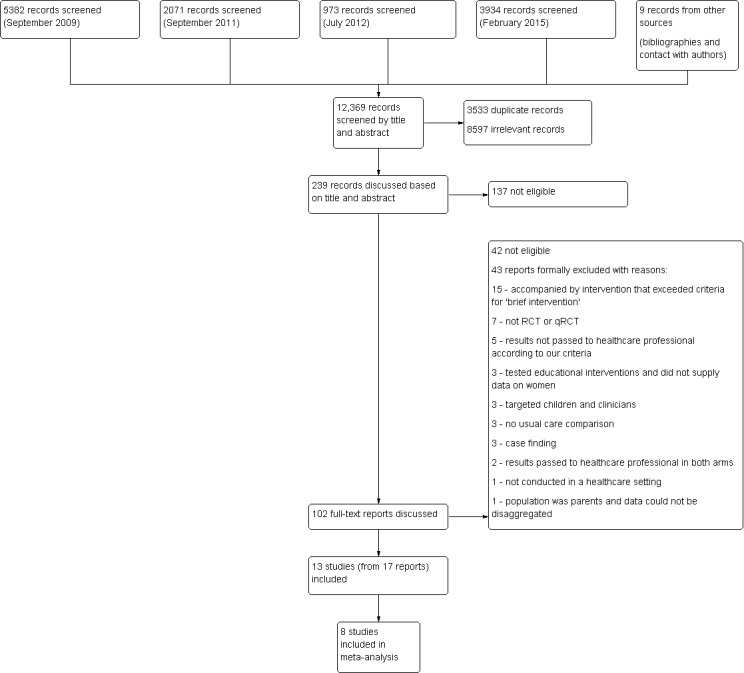

We ran searches four times for this review (September 2009, September 2011, July 2012, and February 2015; see Figure 1). In the original review, two review author pairs (LOD and AT, LOD and KH) independently reviewed abstracts. For this update, TL and EC independently reviewed studies by title and abstract. LOD and AT reviewed studies independently from the point at which full‐text articles had been retrieved (n = 42 in this update).

1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies

Where possible, we resolved disagreement about abstract inclusion between any review authors by reading the full study followed by discussion. When agreement could not be reached, a third review author outside that author pairing (GF, LD, JR or KH) assessed whether or not the study fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Originally, the complex nature of the 'screening' definition required that the entire team met in order to discuss at length and finalise the revised definition of a screening intervention now governing criteria for this review. Two review authors (LOD and AT) independently assessed each study included to this stage against the inclusion criteria with KH also assessing the 42 full‐text articles in the 2015 update. As with the earlier stage of the study review process, we resolved any disagreement by discussing studies in‐depth with other review authors (GF, LD or JR). Where additional information was required to adequately understand the nature of the screening intervention and design, we contacted the first author of the study in question. This led to all outstanding issues being resolved. The reasons behind decisions to exclude otherwise plausible studies are offered in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LOD and AT prior to 2015, or LOD and TL in 2015) independently extracted the data from the included studies and entered data into electronic data collection forms. We requested any missing information or clarification from the first or corresponding authors of papers, and of the nine authors that we contacted, eight replied (Rhodes 2002; Carroll 2005; MacMillan 2009; Koziol‐McLain 2010; Humphreys 2011; Klevens 2012a; Fraga 2014; Fincher 2015). We resolved any disagreements between the two review authors as regards data extraction through discussion; no adjudication by a third review author was necessary. We noted all instances where additional statistical data were provided by study investigators and we distinguished these data as such in the text (Effects of interventions). Once agreed, we entered all relevant data into Review Manager (RevMan) software, Version 5.3 (RevMan 2014).

We recorded the following information in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Method: randomisation or quasi‐randomisation method, intention‐to‐treat analysis, power calculation, and study dates.

Participants: setting, country, inclusion and exclusion criteria, numbers recruited, numbers dropped out, numbers analysed, age, marital status, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and educational background.

Interventions: brief description of intervention, including screening tool and method, and method of usual care.

Outcomes: timing of follow‐up events, outcomes assessed, and scales used.

Notes: further information to aid understanding of the study such as source of funding.

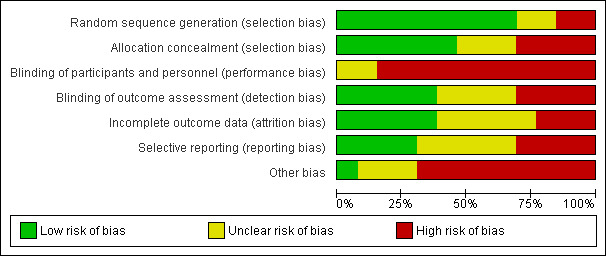

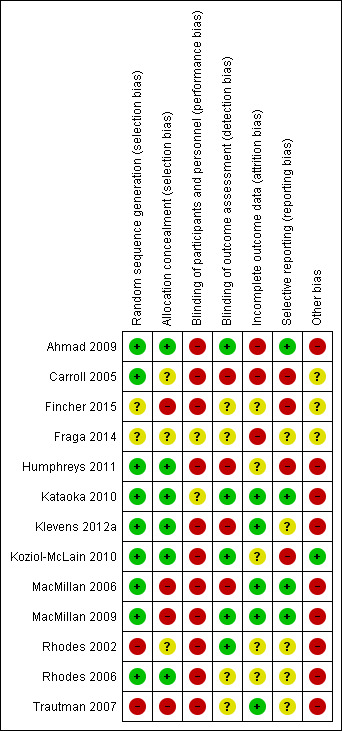

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LOD and AT prior to 2015, or LOD, AT, and TL in 2015) independently assessed the risk of bias of all included studies using the criteria outlined below and cross‐checked in accordance with the updated methodological criteria in Section 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We rated each domain, for each included study, as either 'high', 'low' or 'unclear' risk of bias.

Sequence generation

Description: the method used to generate the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail so as to enable an assessment to be made as to whether it should have produced comparable groups.

Review authors' judgement: was there selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence?

Allocation concealment

Description: the method used to conceal allocation sequences was described in sufficient detail to assess whether intervention schedules could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment.

Review authors' judgement: was there selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment?

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

Description: any measures used to blind healthcare professionals or participants to their randomisation status were described to enable us to know whether the outcomes may have been affected by this knowledge.

Review authors' judgement: was there performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study?

Blinding of outcome assessment

Description: any measures used to blind outcome assessors were described in sufficient detail so as to enable us to assess possible knowledge of which intervention a given participant might have received.

Review authors' judgement: was there detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors?

Incomplete outcome data

Description: the study reported data on attrition and the numbers involved (compared with total randomised) as well as the reasons for attrition or these were obtained from investigators.

Review authors' judgement: was there attrition bias due to the amount, nature, or handling of incomplete outcome data?

Selective outcome reporting

Description: attempts were made to assess the possibility of selective outcome reporting by authors. Where available, we checked protocols and trial databases for prior outcome specification. Where a protocol was not available, we searched the databases of registered trials to check pre‐specified outcome measures. Where neither were available, we were unable to assess this and therefore nominated this as 'uncertain'.

Review authors' judgement: were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias

Description: the study was apparently free of other problems that could put the outcomes at high risk of bias. In common with our associated review on advocacy (Ramsay 2009) ‐ update currently under way and due to be published soon ‐ we specified the following three criteria under this heading.

Baseline measurement of outcome measures

Review authors' judgement: were baseline data (if available) evenly distributed?

Reliability of outcome measures

Review authors' judgement: were outcome measures validated and referenced?

Protection against contamination

Review authors judgement: was there adequate protection against the study being contaminated?

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous outcomes

We analysed continuous data if (i) means and standard deviations (SDs) were available in the report or obtainable from the authors of studies, and (ii) the data were said to be normally distributed. If the second standard was not met then we did not enter such data into RevMan (RevMan 2014) (as it assumes a normal distribution). (More detail on the treatment of continuous data is available in Appendix 3).

Binary outcomes

For binary outcomes (e.g. woman identified/not identified, referred/not referred), we calculated a standard estimation of the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a random‐effects model (Higgins 2011). Where data required to calculate the OR were neither reported nor available from the authors of studies, we did not try to calculate these but have provided the findings as published by the authors.

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipated both individual‐ and cluster‐randomised controlled trials would be identified. With regard to cluster trials, we examined studies to assess whether they had accounted for the effects of clustering using the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) recommendations (Campbell 2012). We have archived methods for re‐analysing cluster trials in future updates of this review (Appendix 3).

We did not use indirect comparisons as all included studies compared the intervention to a suitable comparison condition (usual care or no involvement of healthcare professionals).

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and dropout rates for each of the included studies. If studies were required to impute missing data in published articles, and tables of outcomes with and without imputation were provided, we used the imputed figures. The 'Characteristics of included studies' tables specify the number of women who were included in the final analysis in each group as a proportion of all women randomised in the study. Where available, we provided the reasons given for missing data in the narrative summary along with an assessment of the extent to which the results may have been influenced by missing data. We planned to use sensitivity analysis to deal with missing data. No study conformed to all intention‐to‐treat analysis criteria. We included those in which all completed cases were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised (available case analysis, Higgins 2011, Section 16.2), irrespective of whether or not they received the screening intervention. More detail on the treatment of missing data is available in Appendix 3.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the consistency of results visually and by examining the I² statistic ‐ a quantity that describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2002). Where significant statistical heterogeneity was detected (I² > 50%), we explored differences in clinical characteristics (participants, interventions, outcomes) and methodological characteristics (risk of bias, study design) with modified analyses. We then summarised any differences in the narrative synthesis.

Assessment of reporting biases

There were not enough studies to assess reporting biases. Methods for assessing reporting bias, archived for future updates of this review, are available in Appendix 3.

Data synthesis

We only performed a meta‐analysis where there were sufficient data and it was appropriate to do so. The decision to pool data in this way was determined by the compatibility of populations, denominators, and screening methods (clinical heterogeneity), duration of follow‐up (methodological heterogeneity), and outcomes. As fixed‐effect models ignore heterogeneity, we have used the random‐effects models to take account of the identified heterogeneity of the screening interventions. The Mantel‐Haenszel method, a default program in RevMan (RevMan 2014), can take account of few events or small study sizes and can be used with random‐effects models. Where it was inappropriate to combine the data in a meta‐analysis, we provided a narrative description of the effect sizes as specified in the original study and 95% CIs or SDs for individual outcomes in individual studies. We did not access individual patient data (IPD) as we did not encounter unpublished studies or studies whose data could not be included in our analyses. The main issue with studies included in this review was risk of bias and the IPD approach cannot, generally, help avoid bias associated with study design or conduct (Higgins 2011).

'Summary of findings' table

We used the online Guideline Development Tool (GDT; GRADEpro GDT) to develop 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1 and Table 2). These tables summarise the amount of evidence, typical absolute risks for screened and non‐screened women, estimates of relative effect, and the quality of the body of evidence.

We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to classify the review findings: high quality (further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect); moderate quality (further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and might change it), and low or very low quality (further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change it). The quality of a body of evidence involves considering risk of bias within studies (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates, and the risk of publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses for type of healthcare setting, and analysed data from a subset of studies that measured prevalence (or non‐clinically based identification) rather than clinical identification.

Not enough studies were identified to perform all subgroup analyses planned in the protocol for this review (Taft 2008). Please also see Appendix 3 for subgroup analyses archived for future updates of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We based our primary analyses on available data from all included studies relevant to the comparison of interest. To assess the robustness of conclusions to quality of data and approaches to analysis, we conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

study quality;

differential dropout.

We have archived additional analyses for future updates of this review. Please see Appendix 3.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our searches of the listed electronic databases (see Figure 1) generated 12,369 records (including nine records identified from the reference lists of included studies and from contact with authors) of which 3533 were duplicates; we therefore screened 8836 abstracts. Authors agreed that 8597 abstracts were irrelevant and that 239 required joint review. Following discussions, we excluded a further 137. We subsequently retrieved full‐text papers for 102 records. We determined that 42 were ineligible. A further 43 articles, which appeared as though they could meet inclusion criteria, ultimately did not and we excluded them (reasons for their exclusion are detailed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables). Thirteen studies (that were published in 17 papers) met the inclusion criteria.

Included studies

Study designs

Thirteen randomised controlled trials (Carroll 2005; MacMillan 2006; Rhodes 2006; Ahmad 2009; MacMillan 2009; Kataoka 2010; Koziol‐McLain 2010; Humphreys 2011; Klevens 2012a; Fraga 2014; Fincher 2015), of which, two were quasi‐randomised controlled trials (Rhodes 2002; Trautman 2007), met the criteria for inclusion in this review. All 13 studies were reported in peer‐reviewed journals.

Location

Four studies were conducted in Canada (Carroll 2005; MacMillan 2006; Ahmad 2009; MacMillan 2009), six in the USA (Rhodes 2002, Rhodes 2006; Trautman 2007; Humphreys 2011; Klevens 2012a; Fincher 2015), one in Japan (Kataoka 2010), one in Portugal (Fraga 2014), and one in New Zealand (Koziol‐McLain 2010). Several were cluster‐randomised trials, which accounted for clustering in their analyses, and were conducted in diverse healthcare settings (Carroll 2005; MacMillan 2006; MacMillan 2009). Rhodes 2006 stratified by clinic location (inner urban or suburban) and randomised within location.

Healthcare settings

In three studies, women were recruited from antenatal clinics (Carroll 2005; Kataoka 2010; Humphreys 2011), while Fraga 2014 enrolled women who were one year postpartum at a hospital obstetrics department and MacMillan 2009 included an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic. Four were located in emergency departments (EDs) only (Rhodes 2002; Rhodes 2006; Trautman 2007; Koziol‐McLain 2010). Ahmad 2009 was conducted in a hospital‐affiliated family practice, and both MacMillan 2006 and MacMillan 2009 combined primary and tertiary care sites (family practices, EDs, and women's health services). Klevens 2012a was conducted in assorted women's health clinics in a hospital. Fincher 2015 screened women participating in a Special Supplemental Nutrition Program at a Women, Infants, and Children's (WIC) service. We identified no eligible trials in dental or ophthalmology settings or in maxillofacial injury or fracture clinics.

Characteristics of participants

Both clinicians and their patients participated in all included studies.

Healthcare professionals

In two studies, the first type of participant to be recruited was the clinician (Carroll 2005; Ahmad 2009). They were trained prior to the recruitment of patient participants.

Ahmad 2009 recruited 11/14 eligible family physicians from urban academic hospital‐affiliated family practice clinics. Seven were white female clinicians who had an average age of 46 years and averaged 16 years in practice. Carroll 2005 recruited 48 family physicians, obstetricians, and midwives from four practices diverse in location and populations, which provided antenatal and postpartum care. These different clinicians were paired by age, sex, clinician type, and health service location where possible and then randomised in pairs. Thirty‐six of 48 (75%) were family physicians; the mean age was 42 years and 50% were female. They averaged 13.5 years in practice.

Participants

The 14,959 women recruited to the 13 studies were very diverse in sociodemographic characteristics, and while some studies described the entire screened population, others only described those whose abuse status was identified through screening. The majority of women were Canadian, with over 9000 recruited to MacMillan 2006 and MacMillan 2009.

Pregnant women screened in antenatal settings were aged 30 years or less (Carroll 2005; Kataoka 2010; Humphreys 2011). In Carroll 2005, among the 253 women, 84% were Canadian born; the majority were married with an even income spread and no or minor concerns about their pregnancy. Similarly, although located in an urban Japanese clinic, the 323 women in Kataoka 2010 were overwhelmingly married (over 90%); around 60% were having their first child; and around 80% had post secondary school qualifications, with 42% having college graduate or postgraduate qualifications.

In contrast, Humphreys 2011 described only those 50/410 pregnant women assessed as 'at risk' for IPV at five San Francisco bay antenatal clinics; their profile is consistent with disadvantage. These 50 women were ethnically diverse: 17 were Hispanic, 11 were black or African‐American, 15 were white, and seven were from other backgrounds. Twenty‐three had never married and 29/50 had only high school education or less. The mean age was 28 years and 38 women had been previously pregnant. Women's mean gestational age was 20 weeks and 14 had smoked tobacco in the past 30 days. Forty‐three had been abused in the year before pregnancy and 19 since pregnancy. Twelve had been abused one to three times; four had been abused four to six times; and one more than six times (two had missing data for frequency). Fraga 2014 involved women in a maternity setting who were one year postpartum and had consented to be contacted a year earlier around the time their baby was born. Although they do not provide sociodemographic information for the 915 women in this rapid report, the sample from which women were drawn involved 2660 white women, 9.7% of whom had experienced physical abuse during pregnancy. Women who were abused were more likely to experience preterm birth compared to non‐abused women (21% versus 6.8% respectively), and they were less educated and more likely to be under 20 years of age, not cohabiting, have lower incomes, and have received less antenatal care (Rodrigues 2008).

Klevens 2012a recruited 126 predominantly disadvantaged black women (78.6%) from diverse women's health clinics (obstetric, gynaecological, and family planning) of a Chicago public hospital. The women had a mean age of 35.8 years; either a high school education or less (42.4%) or vocational/college (41.9%); and were uninsured (57.1%) or had Medicaid (37.3%).

Women in emergency settings only were recruited from urban hospitals with ethnically diverse populations (Rhodes 2002; Rhodes 2006; Trautman 2007; Koziol‐McLain 2010). These women tended to be older. In the New Zealand study (Koziol‐McLain 2010), 37.6% of 399 women were Maori and their median age was 40 years. The women's incomes were evenly spread but tended to be in a low‐income bracket; just under half (45.6%) had completed a post‐school qualification other than a university degree (8.3%). About 67.4% currently had partners; and 64.9% were from the main urban area. In a Baltimore Level 1 trauma hospital, the 411 women in Trautman 2007 were overwhelmingly 'non‐white' (83.9%); 41% were aged 35 to 54 years; the majority (50.9%) had children at home; and 34.8% were on Medicaid insurance. While 42.3% were high school graduates, 30.5% had not graduated from high school and 42.4% had an income in the lowest quintile. Around one‐half had physical and mental health summary scores one or two standard deviations (SDs) below norms. The 323 women recruited in Rhodes 2002 had similar characteristics to the urban women in Rhodes 2006. The 1281 women in Rhodes 2006 were very diverse according to whether they were recruited in an urban or suburban ED setting. In the urban ED, 86% of 883 women were African‐American (90% in 2002); had a mean age of 32 years (37 years in 2002); 35% had a high‐school diploma or less and 38% qualifications after high school, but 53% had an income in the lowest quartile; 46% relied on Medicaid (39% in 2002); and 51% were single (59% in 2002). By contrast, in the suburban ED clinic, the median age of the 398 women was 36 years; 80% were white; 71% had post high‐school qualifications; the income spread was more even; 65% had private insurance; and 43% were married with only 31% single.

Ahmad 2009 was the only study to be based solely in a family practice clinic affiliated with an urban academic hospital in Toronto, Canada. The mean age of the 293 women was 44 years; 34.5% of women were born outside Canada; over half were married with 29% having children under 15 years of age living at home. Two‐thirds were employed full‐ or part‐time with an even spread of income, although just under one‐third were in the lowest quintile.

MacMillan 2006 recruited 2461 women from mixed settings: two family practices, two EDs, and two women's health clinics. The women's mean age was 37.1 years; 87% were born in Canada; 55% were married; 46.6% had children at home; 52.2% were educated for more than 14 years; 46.9% were working full‐ or part‐time; and 17.6% had incomes in the lowest quintile.

In the MacMillan 2009 study, 6743 women were also recruited from mixed settings: 12 primary care clinics, 11 EDs, and three obstetric/gynaecology clinics. Characteristics were only described for the 411 women retained and 296 women lost to follow‐up (LTFU) since recruitment, but there was a clear trend to greater abuse and disadvantage among those LTFU compared with those retained. Compared to those LTFU, women retained were more educated, less likely to be single, and had lower scores on the Women Abuse Screen Tool (WAST) and Composite Abuse Scale (CAS).

Fincher 2015 recruited 402 African‐American women, with a mean age of 27 years, who were attending a Women, Infants, Children's (WIC) clinic in Atlanta, Georgia USA. This is an area of high disadvantage with 19% of families living below the federal poverty line and one in four of these families has a child under five years of age. Nearly half of families receive food stamps; the majority are African‐American households. The majority of respondents were single (40%) or in an unmarried relationship (45%). Fourteen per cent of respondents completed some high school education, and 30% had received a high school degree.

Screening intervention

Screening tools

The screening tools applied in these studies as part of the intervention were very heterogeneous. The majority employed an IPV‐specific validated screening instrument, with some studies using more than one tool. Included interventions always consisted of face‐to‐face or healthcare professional‐involved screening. Ideally this was compared to usual care (with no enquiry about IPV). However, there were instances of a screening instrument being applied in the control arm through, for example, computerised or written enquiry, which was tolerated providing those results were not processed by any clinical staff. The tools used in one or more arms of trials were: Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) (MacMillan 2006; MacMillan 2009); Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) (Rhodes 2006; Ahmad 2009; Koziol‐McLain 2010; Humphreys 2011; Fraga 2014); Partner Violence Screen (PVS) (MacMillan 2006; Trautman 2007; Ahmad 2009; Koziol‐McLain 2010; Klevens 2012a); Violence Against Women Screen (VAWS) (Kataoka 2010); and Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) ‐ Short Form (Fincher 2015). Rhodes 2002 adapted questions from the AAS and PVS and others. In several cases, omnibus screening aimed to assess a range of psychosocial problems (e.g. to assess a range of health issues in pregnancy or to diminish stigma around the true purpose of the study), of which IPV was only one (e.g. Ahmad 2009; Humphreys 2011). In Carroll 2005, the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) tool assessed a range of psychosocial issues such as child abuse and depression; the IPV questions contained in the ALPHA are derived from the WAST (Carroll 2005). The validity of these tools is also heterogeneous and thoroughly reviewed in Feder 2009 (p 29). Often, data collected through the screening intervention fed into the primary identification outcome data.

Screening methods and strategies

Studies used different modes of applying the screening tools indicated above in intervention and comparison groups. Five interventions involved a computer‐assisted self completion screening process with positive results being conveyed to providers (Rhodes 2002; Rhodes 2006; Trautman 2007; Ahmad 2009; Humphreys 2011). MacMillan 2009 used written methods in their intervention arm before conveying results to healthcare professionals. Carroll 2005, MacMillan 2006, Kataoka 2010, Koziol‐McLain 2010, and Fraga 2014 included face‐to‐face screening where the healthcare professionals themselves screened the women. Kataoka 2010 selected a written enquiry method as the comparison compared with face‐to‐face screening, but since it was face‐to‐face, this method guaranteed the result was processed by a healthcare professional; in this study we treated face‐to‐face screening as the intervention. Klevens 2012a compared healthcare professional screening with audio computer‐assisted self interviews (A‐CASI) screening. Fraga 2014 had three groups, but we combined the two arms that involved social worker screening (face‐to‐face and telephone) and compared it to a group that received a questionnaire by post. In Fincher 2015, women attending a community health programme (WIC services) received face‐to‐face screening by trained healthcare professional researchers who provided information and resources on issues, including healthy relationships. As this was the only included study that had researchers, as opposed to healthcare professionals, deliver the face‐to‐face screening, we excluded it from our primary analysis as, ultimately, the data were not part of the clinical context.

Comparisons

Six studies compared IPV screening with usual care (Rhodes 2002; Carroll 2005; Rhodes 2006; Ahmad 2009; MacMillan 2009; Koziol‐McLain 2010). Humphreys 2011 compared IPV screening and clinician follow‐up with researcher‐based IPV screening where results were not provided to the clinician. Written self completion was used in one arm of MacMillan 2006 (which we used as a comparison arm) and they used computerised self completion in another (which we also treated as comparison). Trautman 2007 compared screening that included questions about IPV with screening for other issues that did not include IPV, and both sets of results were passed on to clinicians. Kataoka 2010 compared face‐to‐face screening interview by a healthcare professional with a self administered questionnaire and Klevens 2012a compared A‐CASI screening with the same screen administered by the clinician. Fraga 2014 compared screening by social workers to a group that received a questionnaire by post.

We treated groups where women self completed IPV questions but with no follow‐up or involvement of clinicians, and screening for health issues without reference to IPV, as 'usual care' conditions.

Outcomes and outcome measures

Identification (including discussion or detection)

All but one study, Koziol‐McLain 2010, in some way measured the identification of IPV using various screening modes and tools. However, this was not always a form of clinical identification, with some studies gathering what was more akin to prevalence data according to different modes of screening (MacMillan 2006; Kataoka 2010; Fincher 2015), rather than information for use in the clinical domain. There were instances where clinical identification data were recorded but did not lend themselves to meta‐analysis because they were not measured consistently across arms of the trial (Klevens 2012a). Thus, we combined these four studies in a meta‐analysis of non‐clinically based identification based on face‐to‐face screening versus other screening techniques.

Eight studies measured identification such that it could be defined as clinical identification of IPV from screening and we used this in our primary analyses (Rhodes 2002; Carroll 2005; Rhodes 2006; Trautman 2007; Ahmad 2009; MacMillan 2009; Humphreys 2011; Fraga 2014). These data were gathered through providers' and women's self report about what had occurred during the consultation, chart review/clinical documentation, and audio‐recordings of clinical encounters.

Information‐giving, referral, and uptake of services

While most studies included some assessment of the provision of information, referral, and women's service use, measurement of these outcomes varied enormously. First, the provision of information or resources was already linked to the majority of interventions and received by women who took up the intervention. For example, a computer print‐out of resources or information pamphlets commonly occurred as part of the intervention. Thus, it was not appropriate for us to treat it as an outcome of screening interventions. Another example can be found in Rhodes 2006, where provision of services was defined as safety assessment, counselling by the healthcare providers, and provision of information on resources; to measure these would be more in keeping with an assessment of fidelity since these are features of the intervention, rather than outcomes of a screening intervention.

Studies also varied greatly in how they defined referral. For example, Klevens 2012a made reference to three types of 'referral' ‐ healthcare professional, A‐CASI plus provider support, and A‐CASI alone, but this was more about how women in the different arms self referred based on the list of resources provided to them in each trial arm. We were interested to know if screening interventions increased women's formal referral to other internal and external support services, with this information being derived from medical records or self report by participants or even data from services to indicate the number of women referred to them. However, only two studies treated referral in this way and were included in a meta‐analysis (Trautman 2007; Ahmad 2009). Trautman 2007 examined differences in the numbers referred to social work by the treating staff at the ED and Ahmad 2009 used audio‐recordings of consultations to determine if women were referred. Ahmad also checked if any arrangements were made for follow‐up appointments but this was not included in the referral data.

Uptake of services suffered similar difficulties, encompassing different variables for different studies where some looked at specific uptake based on the resources that were flagged (Trautman 2007; Klevens 2012a), and others look at a more general uptake of community services (Koziol‐McLain 2010). Consequently, we were unable to include data on uptake of services in a meta‐analysis.

Intimate partner violence

MacMillan 2009 and Koziol‐McLain 2010 included level of exposure to IPV (using the CAS, Hegarty 2005) as a primary outcome.

Women's health and quality of life

MacMillan 2009 included quality of life as a primary outcome (assessed with the WHO Quality of Life‐Bref), but included in their secondary outcomes: general health (Short Form health survey ‐ 12 (SF‐12)), depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies ‐ Depression Scale (CES‐D)), post‐traumatic stress disorder (Startle, Physiological arousal, Anger, and Numbness (SPAN)), alcohol use or dependency (Tolerance, Worried, Eye‐opener, Amnesia, K/Cut Down (TWEAK), and Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)).

Adverse and other outcomes

Ahmad 2009 included advice for follow‐up and patient comfort with screening, and need to consult with the nurse after screening. Carroll 2005, MacMillan 2006, Kataoka 2010, and Klevens 2012a measured comfort and preference for mode or satisfaction with the screening process.