Abstract

The “itch mite” or “mange mite”, Sarcoptes scabiei, causes scabies in humans and sarcoptic mange in domestic and free-ranging animals. This mite has a wide host range due to its ability to adapt to new hosts and has been spread across the globe presumably through human expansion. While disease caused by S. scabiei has been very well-studied in humans and domestic animals, there are still numerous gaps in our understanding of this pathogen in free-ranging wildlife. The literature on sarcoptic mange in North American wildlife is particularly limited, which may be due to the relatively limited number of clinically-affected species and lack of severe population impacts seen in other continents. This review article provides a summary of the current knowledge of mange in wildlife, with a focus on the most common clinically-affected species in North America including red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), gray wolves (Canis lupus), coyotes (Canis latrans), and American black bears (Ursus americanus).

Keywords: Mange, Sarcoptes scabiei, Wildlife, North America

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Sarcoptic mange is an important wildlife disease across the globe.

-

•

There is a lack of field surveys on mange in North American wildlife.

-

•

This review summarizes the natural history of Sarcoptes scabiei.

-

•

There are few reports on methods to control mange in wildlife.

-

•

The known host range in North American wildlife is also addressed.

1. Introduction

Sarcoptic mange is a common, widespread disease of domestic and wild mammals (Currier et al., 2011). The causative agent is Sarcoptes scabiei, a microscopic mite that infests the skin of its host by burrowing into the epidermis (Fuller, 2013). It is an acarid that belongs to the order Sarcoptiformes, which includes other mites of veterinary importance such as Psoroptes, Knemicodoptes, and Notoedres, among others. In humans, S. scabiei causes disease known as scabies, and in animals the disease is referred to as sarcoptic mange (McCarthy et al., 2004). While not proven, one theory suggests that S. scabiei originated as a pathogen of humans with animals serving as aberrant spillover hosts. In this theory, the observed variability in host adaptations of S. scabiei is likely the result of continuous interbreeding of the different strains that affect humans and animals (Fain, 1978, 1991).

In general, the lesions most commonly associated with sarcoptic mange include alopecia, hyperkeratosis, and erythema often accompanied by intense pruritus. Thick skin crusting and fissuring often occur, and many animals die from emaciation or secondary infections with bacteria or yeast (Fischer et al., 2003; Radi, 2004; Oleaga et al., 2008; Nakagawa et al., 2009). Mange epizootics have been reported in a variety of host species worldwide. These events are often associated with high morbidity and mortality in wildlife populations, including Cantabrian chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica parava) in Spain, red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Fennoscandia, and wombats (Lasiorhinus sp. and Vombatus ursinus) in Australia (Fernández-Moran et al., 1997; Pence and Ueckermann, 2002).

Scabies in humans has been recognized since biblical times and was one of the first human diseases with a known etiology. Various treatments in animals, using olive oil, lupine, wine, tar, or grease, were described in Europe and the Middle East between the 1st and 16th centuries. The term scabies may have been first used by the Roman physician Celsus, but this is not widely accepted. The etiology of mange was not determined to be a parasite until the 17th century by Bonomo. He and other colleagues made large advances on the biology of S. scabiei by describing the two sexes and replication by sexual reproduction. Linnaeus was the first to formally describe and name the mite – as Acarus humanus subcutaneous in man and Acarus exulcerans in animals. The rediscovered mite was renamed by Renucci in 1834 to Acarus scabiei from a human in Paris. For additional information, multiple reviews on the history of scabies and mange have been published (Friedman, 1934; Roncalli, 1987; Currier et al., 2011).

Sarcoptic mange is a well-documented and researched disease of wildlife in Europe, Australia, Africa, and Asia (Zumpt and Ledger, 1973; Mӧrner, 1992; Kraabol et al., 2015; Fraser et al., 2016; Old et al., 2018). Although sarcoptic mange is a common cause of disease in select wildlife species in North America, similar published reports or reviews are lacking. Herein, we review the natural history of S. scabiei, including morphology, diagnostics, and research on wildlife species in North America. Research from wildlife outside of North America or in humans is addressed where it can be related to the disease in North American wildlife.

2. Sarcoptes scabiei

2.1. Phylogeny and classification

Sarcoptes scabiei (Linnaeus, 1758) is in the superorder Acariformes and order Sarcoptiformes. It is within the superfamily Sarcoptoidea, and family Sarcoptidae. Sarcoptidae contains three subfamilies including Sarcoptinae which consists of four genera, including Sarcoptes (Desch, 2001; Zhang, 2013). It has been suggested that S. scabiei is a single heterogenous species that exhibits a high degree of host specificity but has some level of cross-infectivity (Stone et al., 1972; Pence et al., 1975; Fain, 1978; Arlian et al., 1984b; Zahler et al., 1999). Traditionally, variant forms of S. scabiei have been identified based on the host species from which they were detected (e.g. Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis, Sarcoptes scabiei var. suis, etc.) and inability to cause pronounced clinical disease in taxonomically distinct hosts (Fain, 1968; Ruiz et al., 1977; Fain, 1978; Arlian et al., 1984b; Arlian et al. 1988b; Arlian et al. 1989). However, few morphological differences are seen among mites found on different host species (Fain, 1968; Fain, 1978). Rather, it is believed that the differences between these variants, which define their host preference, are physiologic and/or genetic (Pence et al., 1975). Other than human variants being distinct from the ‘animal’ clade, genetic studies conducted to date have not been able to consistently distinguish between different host variants using common gene targets for mites including internal transcribed spacer region-2 (ITS-2) and cytochrome oxidase 1 (COI) (Zahler et al., 1999; Berrilli et al., 2002; Skerratt et al., 2002; Gu and Yang, 2008; Gu and Yang, 2009; Peltier et al., 2017).

In contrast, consistent clustering in geographic or host specificity can still be obtained using microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA as markers, which shows uncertainty for the usefulness of ITS-2 as a gene for S. scabiei phylogenetic analyses (Zahler et al., 1999; Walton et al., 2004; Soglia et al., 2007; Alasaad et al., 2009; Rasero et al., 2010; Gakuya et al., 2011). There is potential for microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA to have value, but there is little consistency in which microsatellites or targets are chosen inhibiting the ability to compare large datasets. The Sarcoptes-World Molecular Network was created to improve methods of Sarcoptes detection as well as provide a central location for comparing phylogenetic data (Alasaad et al., 2011). A formal consensus on the taxonomy based on morphological and genetic features has not been made other than to suggest that all Sarcoptes scabiei variants are the same genetically diverse species (Fraser et al., 2016).

2.2. Life cycle

The life cycle of S. scabiei consists of five stages: egg, larva, protonymph, tritonymph, and adult (Fig. 1) (Fain, 1968; Arlian and Vyszenski-Moher, 1988). Adults create tunnels through the superficial layer of host skin in part accomplished by cutting mouthpieces and hooks on the legs (Fig. 2A) (Arlian and Vyszenski-Moher, 1988). Little is known about the secreted substances the mite may use to help aid in this tunneling process (Arlian et al., 1984a). Penetration into the epidermis must be achieved for infestation and disease manifestation to occur (Arlian, 1989). Most tunnels track through the stratum corneum of the epidermis; however, mites can penetrate the stratum granulosum and stratum spinosum in both humans and animals (Video 1) (Morrison et al., 1982; Levi et al., 2012). Mites are able to penetrate the skin within 30 min of contact (Arlian et al., 1984a; Arlian and Vyszenski-Moher, 1988).

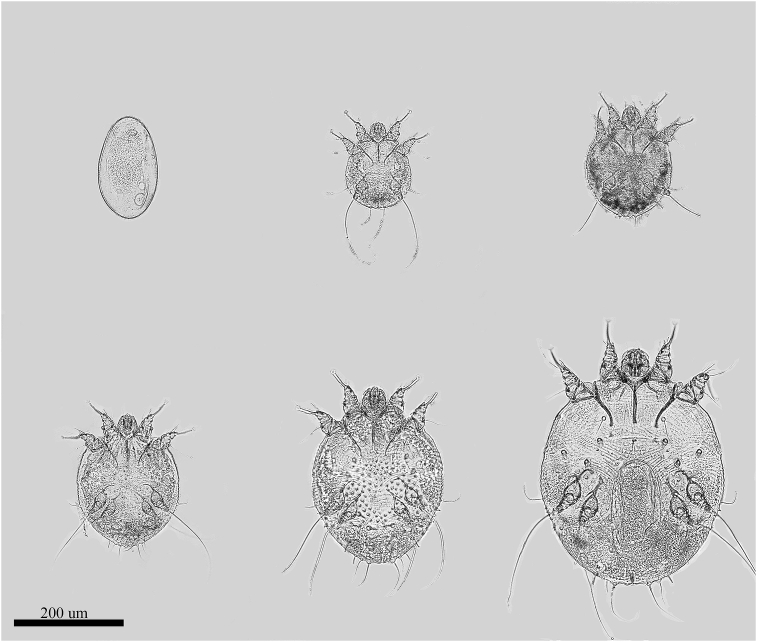

Fig. 1.

Life stages of S. scabiei. Top left: Egg; Top middle: Larva; Top right: Protonymph; Bottom left: Tritonymph; Bottom middle: Adult Male; Bottom right: Adult Female.

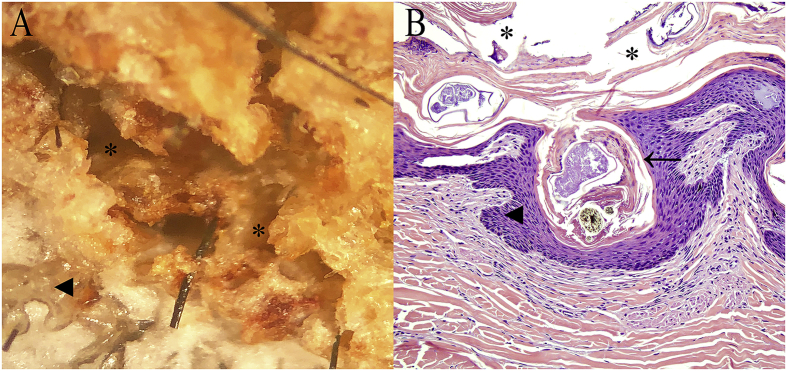

Fig. 2.

Microscopic lesions of a bear with sarcoptic mange. (A) Close-up view of hyperkeratotic and crusted skin showing a mite tunnel. (B) Histological section with cross-section of S. scabiei within the epidermis. (Asterisks: mite tunnels; arrowheads: epidermis; arrow pointing to S. scabiei).

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.06.003.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

videoMultiple life stages of S. scabiei moving within mite tunnels, as well as a cluster of eggs, from the skin of a black bear with sarcoptic mange.

Adult females will lay approximately three to four eggs per day, and it is estimated that one mite can produce over 50 eggs during its four to six week life expectancy (Arlian and Morgan, 2017). Based on studies using a rabbit model, the larvae hatch from eggs between 50 and 53 h, larvae molt to protonymphs 3–4 days later, and protonymphs to tritonymphs and tritonymphs to adult were both 2–3 days thereafter (Arlian and Vyszenski-Moher, 1988). There is likely significant variation in the duration of each life stage based on temperature, humidity, host, and observation methods, but much of this variation and importance of different factors are poorly understood (Arlian and Morgan, 2017). Larvae, nymphs, and adult males can also be found in these tunnels ingesting host cells and lymph. The entire life cycle from egg to adult takes approximately two weeks, and all life stages can be found on the same individual host (Arlian and Vyszenski-Moher, 1988).

2.3. Morphology

Detailed morphological features were initially described by Fain in 1968. Overall, the S. scabiei idiosoma is dorsally convex and ventrally flattened. All four pairs of limbs of the mite are short and stout with the anterior two pairs of limbs extending out beyond the margin of the idiosoma while the posterior two pairs of limbs do not in adults. The tarsi of the anterior two legs have two blade-like claws as well as stalked empodium with distal pads, and the tibiotarsi of the posterior legs have one or two blade-like claws depending on whether the mite is male or female. Extending from the tarsi are long, unsegmented pedicels with bell-like caruncles. These are found on the anterior two pairs of legs in females and on all four pairs of legs in males. Females have long setae extending from their posterior two pairs of legs (Fain, 1968; Pence et al., 1975; Colloff and Spieksma, 1992; Wall and Shearer, 2001).

Cytologically, S. scabiei is identified by its characteristic club-like setae on the posterior end of its dorsal idiosoma and by the tooth-like cuticular denticles/spines of the females in the mid-dorsal region of the idiosoma. Both sexes have claws on the terminal segments of all legs as well as have a terminal anus. Transverse, ridged, dorsal striations are present on the idiosoma. These morphologic characteristics distinguish S. scabiei from other sarcoptiform mites found on select mammalian hosts such as Notoedres spp. (dorsal anus), Psoroptes spp. (smooth body, jointed leg stalks, and teardrop-shaped), Trixacarus caviae (adult females approximately 200 microns shorter in length), Ursicoptes spp. (ovoid to elongated idiosoma), and Chorioptes spp. (short pedicels) (Bornstein et al., 2001; Wall and Shearer, 2001; Yunker et al., 1980). Demodex spp. are another mite group commonly associated with clinical disease in numerous wild and domestic mammals, but they have a distinct ‘cigar-shaped’ morphology (Elston and Elston, 2014).

2.4. Transmission

Transmission of S. scabiei, to any host, occurs via direct and/or indirect contact (i.e. shared environments or fomites) (Smith, 1986; Arlian et al., 1988a; Arlian et al., 1989). The importance of each mechanism of transmission likely varies between hosts based on a variety of factors, including host susceptibility and behavior, mite strain, and environmental conditions. Direct contact transmission is often the primary means of transmission in humans (Otero et al., 2004; Chosidow, 2006). In wildlife, the mechanisms of transmission are likely variable and include both direct transmission in social species as well as indirect transmission in more solitary species, but our understanding of mechanisms of transmission in many wildlife species is lacking (Dominguez et al., 2008; Devenish-Nelson et al., 2014; Almberg et al., 2015; Ezenwa et al., 2016). Vertical transmission between adults and offspring has also been reported and occurs after birth (Cargill and Dobson, 1979a, b; Arends et al., 1990; Fthenakis et al., 2001). Numerous field-based molecular and experimental studies on the transmission of mites between similar and different hosts, including between animals and humans, have suggested that infestivity and severe disease occurred most commonly when mites were shared between similar hosts rather than between distantly related hosts (Smith and Claypool, 1967; Thomsett, 1968; Samuel, 1981; Arlian et al., 1984b; Arlian et al., 1988b; Bornstein, 1991; Mitra et al., 1995).

An important factor influencing the efficiency of indirect transmission is mite survival in the environment. Temperature, humidity, and possibly mite strain are important factors that can affect the ability of mites to survive off of the host, with survival being shortest at temperatures less than 0 °C and above 45 °C and at lower relative humidity (less than 25%); mites survived longest at cool (between 4 and 10 °C) but not freezing temperatures and high (97%) relative humidity (Arlian et al., 1984a; Arlian et al., 1989; Niedringhaus et al., 2019a). In the environment, mites use multiple cues to seek out new hosts, including temperature and odor (Arlian et al., 1984c). Additionally, it was shown that mites are likely only able to penetrate the skin and cause subsequent disease between one half to two thirds of its survival time in the environment (Arlian et al., 1984a; Arlian et al., 1989). Simulation models showed that San Juan Kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis mutica) likely transmit mites indirectly between family groups using dens rather than direct contact (Montecino-Latorre et al., 2019). Additionally, indirect transmission through shared dens is likely the most dominant mechanism of mite transmission among wombats as well as possibly within and between carnivore species in Europe (Kolodziej-Sobocinska et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2019). Evidence of indirect transmission and data showing mite survival off of the live host suggest that scenarios when animals share space, including artificial feeding sites, may contribute to mite transmission (Süld et al., 2014; Niedringhaus et al., 2019a).

3. Sarcoptic mange

3.1. Clinical signs and pathology

The incubation period (i.e. period from exposure to the development of observable signs or lesions) is dependent on host and the quantity of mite exposure. Experimentally, incubation period has ranged from 6 days in domestic dogs to 30 days in other species (Stone et al., 1972; Mӧrner and Christensson, 1984; Bornstein, 1991; Bornstein and Zakrisson, 1993a; Bornstein et al., 1995). The most common clinical signs and gross lesions in all hosts include pruritus, erythema, hyperkeratosis, seborrhea, and alopecia (Bornstein and Zakrisson, 1993a; Bornstein et al., 1995; Leon-Vizcaino et al., 1999; Aujla et al., 2000). However, these signs can result in at least two unique manifestations of mange: ‘ordinary’ mange characterized by predominately alopecia (in haired mammals) with relatively few mites present, and ‘crusted mange’ that results in severe hyperkeratosis and serocelluar crusts and is associated with a large mite burden (Pence and Ueckermann, 2002; Fraser et al., 2018a). These presentations in humans are often known as ‘classical’ scabies and ‘Norwegian’ or ‘crusted’ scabies, respectively (Arlian et al., 2004).

The progression of lesions is largely consistent among experimental infections of dogs, pigs, rabbits, and foxes. The first observable lesions include seborrhea and erythema, followed by crusting and alopecia several days thereafter (Stone et al., 1972; Samuel, 1981; Bornstein et al., 1995; Nimmervoll et al., 2013). The lesions radiate from the site of infection until hyperkeratosis occurs (Little et al., 1998b). As the disease progresses, similar lesions begin to appear on other parts of the body including the limbs (Stone et al., 1972; Pence et al., 1983; Mӧrner and Christensson, 1984; Bornstein et al., 1995). As the immune response progresses, pruritus increases while mite burden decreases. Subsequent chronic lesions include skin thickening, lichenification, loss of nutritional condition, secondary bacterial or yeast infections of the skin, and in some cases the animal may become septic (Bornstein et al., 1995). The intense pruritus results in a dramatic increase in the number and severity of self-inflicted lesions created by the host from licking and scratching at its skin (Samuel, 1981). Thus, many of the lesions seen in later infestations are due to the manifestation of the hypersensitivity response rather than the mites themselves (Pence and Ueckermann, 2002). Nimmervoll et al. (2013) suggested that in foxes, lesions start as focal skin disease and either progress to a severe hyperkeratosis with generalized skin lesions or switch to an alopecic/healing form (Fig. 2B). The end stages of the disease often show animals with reduced appetite, dehydration, and poor physical condition (Bornstein et al., 1995; Samuel, 1981; Martin et al., 2018). Several organisms have been associated with secondary infections in cases of sarcoptic mange including Malassezia pachydermatis and Pelodera strongyloides although their role in lesions present is largely unknown (Salkin et al., 1980; Fitzgerald et al., 2008; Peltier et al., 2018).

Sarcoptes mites produce a variety of antigenic material (e.g. eggshells, molted skins, dead mites, and mite feces) as they penetrate and burrow through the skin of the host (Arlian et al., 1985; Morgan et al., 2016). The type of immune response is largely dependent on the immune status of the host and if the host can induce an appropriate hypersensitivity response (Pence and Ueckermann, 2002). Some highly susceptible species (e.g. red foxes) develop a hypersensitivity response to this material, the most common of which is the Type 1 (i.e. immediate response) (Little et al., 1998b; Tarigan and Huntley, 2005). A Type 4 (i.e. delayed response), where many T-lymphocytes accumulate in the dermis, has been reported in humans, domestic dogs, and pigs and in conjunction with a Type I reaction (Sheahan, 1975; Davis and Moon, 1990; Bornstein and Zakrisson, 1993b; Skerratt, 2003a, Skerratt, 2003b; Elder et al., 2006). The Type I hypersensitivity primarily manifests as hyperplasia of mast cells and eosinophils with associated increases in these cell types on blood cell counts (Little et al., 1998b).

3.2. Diagnostic testing and monitoring

While clinical signs can be suggestive of mange, confirming the disease in individual animals requires one of the following techniques: cytology/histology to identify mites and describe the associated pathology, detection of antibodies in the serum, and/or molecular techniques (Angelone-Alasaad et al., 2015). Sarcoptic mange can grossly appear similar to other skin diseases, and identification of mites, typically by skin scrape or biopsy, is necessary to make an accurate diagnosis in both humans and animals (Hill and Steinberg, 1993; Curtis, 2012). In addition, mange can be caused by different species, even genera, of mites in individual host species so morphologic or molecular identification of mites is important. For example, mange in black bears (Ursus americanus) can be caused by S. scabiei, Ursicoptes americanus, and Demodex ursi (Yunker et al., 1980; Desch, 2009; Peltier et al., 2018). While skin scrapes are the most commonly used method for diagnosing mange, variation in mite burden and host response between species may result in inconsistencies for this diagnostic approach (Little et al., 1998b; Fraser et al., 2018b, Fraser et al., 2018a; Peltier et al., 2018). For example, in canids, the mite burden is generally low even in severely affected animals and consequently cytology may not be effective at detecting mites in these hosts (Samuel, 1981; Hill and Steinberg, 1993). In other species (e.g. pigs, humans, and bears) mite burdens are higher with similar or less severe clinical signs, resulting in higher success of detection of mites via cytology (Davis and Moon, 1990; Walton and Currie, 2007; Peltier et al., 2018).

Characteristic histological lesions, including eosinophilic or lymphocytic dermatitis, acanthosis, and severe parakeratotic hyperkeratosis can help support a diagnosis of mange. While seeing cross-sections of arthropods within the epidermis is often diagnostic for this disease, identifying mite species on histology can be problematic in hosts that may be infested by multiple species (Pence et al., 1983; Nimmervoll et al., 2013; Salvadori et al., 2016; Peltier et al., 2018). Conventional and real-time polymerase chain reaction targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA, rRNA, ITS-2, and/or COI genes, as well as microsatellites, has been successfully utilized to identify S. scabiei DNA from skin scrapings in numerous animal species and humans (Walton et al., 1997; Fukuyama et al., 2010; Angelone-Alasaad et al., 2015; Peltier et al., 2017). To reduce the requirement of capturing wildlife for testing, an assay to detect Notoedres spp. in the feces of bobcats was created, but similar techniques for the detection of S. scabiei in bears was unsuccessful at mite detection (Stephenson et al., 2013; Peltier et al., 2018). PCR may be more a sensitive technique than cytology in cases where there is a low mite burden, such as in dogs and foxes; histology may also provide evidence of infestation but is considered less specific (Nimmervoll et al., 2013; Cypher et al., 2017). More recently, a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay was developed to rapidly diagnose mange (Fraser et al., 2018b).

Several approaches can be used to investigate mange and mite exposure in populations. Serological tests can be useful to determine previous exposure to S. scabiei, but may not differentiate past exposure with current clinical disease. Similarly, its usefulness for individuals can be limited due to unknown time of initial exposure, possible differences in individual immune responses, and unknown applicability for commercially available assays for use in wildlife species. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent serologic assay (ELISA) has been developed for use in dogs and pigs for the detection of antibodies against S. scabiei. This and similar assays have been evaluated in many other wild and domestic animal taxa with variable results (e.g., Bornstein and Zakrisson, 1993a; Bornstein et al., 1996; Bornstein et al., 2006; Haas et al., 2015; Fuchs et al., 2016; Raez-Bravo et al., 2016; Peltier et al., 2018). More recent techniques reported to diagnose sarcoptic mange in wildlife include a dot-ELISA for use in rabbits and has shown to be a simple, quick, and convenient way to accurately diagnose the disease (Zhang et al., 2013). An indirect ELISA, as well as a Western blot assay, has been used on lung extract and pleural fluid from animals that died prior to blood collection, allowing testing to be performed on animals that may not have died as recently or when serum is unavailable (Jakubek et al., 2012). Serology can be complicated by cross-reactivity, particularly in wildlife, due to infestation by closely-related mite species (Arlian et al., 2015; Arlian et al., 2017).

Additional methods to monitor the prevalence, distribution, and consequences of mange in wild populations have been investigated. Detector dogs have been trained to find animals with sarcoptic mange in an attempt to detect cases and control the disease in populations of Alpine chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra rupicapra) and Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) (Alasaad et al., 2012b). Radio-collaring affected animals can show the impacts of mange on multiple individuals, including evidence of a drastic reduction in home-range sizes of affected raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) (Süld et al., 2017). Camera traps have been used to monitor mange distribution in wildlife. This technique has become popular because it likely reduces the bias of clinically-ill animals being more likely to be shot or caught (Carricondo-Sanchez et al., 2017). Camera traps have been used to estimate prevalence of sarcoptic mange in coyotes (Canis latrans), feral swine, and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), but only severe cases of mange were consistently diagnosed, and mild cases often went undetected (Brewster et al., 2017). Camera traps have also been used to monitor mange in raccoon dogs in Japan, wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy and Spain, and bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus) in Australia (Oleaga et al., 2011; Borchard et al., 2012; Galaverni et al., 2012; Saito and Sonoda, 2017). Thermal imaging for tele-diagnosis and physiological consequences of mange in Spanish ibex and gray wolves were also explored (Arenas et al., 2002; Cross et al., 2016). However, imaging techniques are sensitive but lack specificity as this approach cannot distinguish between mange and other causes of skin disease or alopecia nor determine the species of mite potentially involved.

3.3. Management and treatment

There are several approaches that have been used to manage sarcoptic mange in free-ranging wildlife, and each approach has advantages and disadvantages. Wildlife managers can attempt to reduce the likelihood of transmission of S. scabiei between hosts by reducing unnatural contacts between individuals (including minimizing artificial feeding), by maintaining biosecurity when trapping, handling, or transporting diseased wildlife, emphasizing prevention of a novel pathogen introduction, or by treatment and rehabilitation of individual animals (Wobeser, 2002; Sorensen et al., 2014; Van Wick and Hashem, 2019). Additionally, transmission studies show a lack of evidence for density-dependent transmission, although it is likely context-dependent (i.e., more density-dependent in some systems and frequency-dependent in others) (Devenish-Nelson et al., 2014). There is little research on methods and efficacy of managing mange in free-ranging wildlife without treatment. Hunting animals or reducing densities alone may not halt the disease spread because animals may move more into newly-created territories (Lindstrom and Mӧrner, 1985). Dogs able to find carcasses and live animals affected with mange allows removal or treatment of those individuals as means to prevent additional transmission of the parasite and more accurate monitoring of the population effects of mange, but this technique would not be feasible in many susceptible hosts (Alasaad et al., 2012b).

Additionally, one should consider whether attempted management of an endemic disease in a population that is considered healthy from a conservation standpoint should be pursued. If management of sarcoptic mange in wildlife is being considered, the actions should be tailored to the biology of the host affected. For example, if dens or burrows are a significant source of transmission in some canids or wombats, the approach would be different compared to bears where dens are unlikely to be a source of infestation (Martin et al., 2018; Montecino-Latorre et al., 2019; Niedringhaus et al., 2019a).

Managing mange in domestic species typically involves preventive treatments or the use of approved drugs for treatment of clinical cases by a veterinarian. Numerous publications regarding various treatment regimens have been published for sarcoptic mange in livestock and companion domestic animals including cats, goats, dogs, pigs, and alpacas (Ibrahim and Abusamra, 1987; Jacobson et al., 1999; Wagner and Wendlberger, 2000; Curtis, 2004; Malik et al., 2006; Twomey et al., 2009; Becskei et al., 2016; Beugnet et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2016). However, there is limited information regarding the approved use of any of these treatments for use in free-ranging wildlife.

Treatment of mange in free-ranging wildlife is controversial, but has been conducted for a variety of reasons, including animal welfare concerns, threatened or endangered species, or for research purposes. Rowe and others (2019) recently provided a review on treatment of sarcoptic mange in wildlife and noted that most studies have been performed in Australia, Africa, and Europe. Based on their review, ivermectin applied subcutaneously for multiple doses between 200 and 400 μg/kg was the most successful and common treatment approach used in these studies, but fluralaner, amitraz, and phoxim were successfully used in some studies. Overall success of treatment was often influenced by severity of disease and number of dosages with greater number of doses given often associated with treatment success (Leon-Vizcaino et al., 2001; Munang’Andu et al., 2010). Additionally, supportive care with the use of fluids and antibiotics also improved the treatment success in captive raccoon dogs (Kido et al., 2014). Two studies that showed a failure of resolution of clinical signs were from moderately to severely-affected animals as well as from single-application of ivermectin and topical selamectin (Newman et al., 2002; Speight et al., 2017).

The authors of the review (Rowe et al., 2019) also acknowledged the lack of randomized control trials as well as minimal post-treatment monitoring of wildlife species to determine treatment efficacy and possible re-infection. Their broad recommendations included treating only mild to moderately-affected animals and removing severely-affected individuals from the population. When deciding if treatment is appropriate, factors must be considered including possible side effects of the drugs, severity of disease, if multiple doses are required and can be delivered, the ability to provide supportive care, ability to monitor or data suggesting post-treatment success, Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification (AMDUCA) and withdrawal time compliance in animals that may enter the food chain, potential for development of drug resistance, determining if the animal is truly cleared of infection or becomes a subclinical carrier, and if the animal is being translocated to a mange-free area (Currie et al., 2004; Terada et al., 2010; Rowe et al., 2019). In several instances involving species of special concern, studies have shown treatment can lead to population recovery (Mӧrner, 1992; Goltsman et al., 1996; Leon-Vizcaino et al., 2001; Cypher et al., 2017). However in most scenarios, it may be more important to ask the question ‘is treatment warranted’ rather than ‘which treatment is warranted.’

4. Mange in North American wildlife

4.1. Host range

Globally, it is estimated that S. scabiei affects more than 100 species of mammals representing a wide variety of taxa including canids, ungulates, marsupials, felids, suids, rodents, and primates. In North America, the number of free-ranging species reported to develop clinical sarcoptic mange is less than in other continents, and canids are the hosts primarily affected, particularly at the population-level (Fig. 3). Sarcoptic mange in other continents more commonly affects other taxa including cervids, bovids, felids, rodents, and mustelids (Bornstein et al., 2001). For example, in Europe, sarcoptic mange is considered one of the most common causes of mortality in chamois and Spanish ibex, but also affects numerous other bovids, cervids, mustelids, and felids including many species that are also present in North America but have not been reportedwith sarcoptic mange (Mӧrner, 1992; Rossi et al., 1995; Fernandez-Moran et al., 1997; Ryser-Degiorgis et al., 2002; Kolodziej-Sobocinska et al., 2014). A wide variety of species have been reported to develop clinical disease in Africa including giraffes, gorillas, lions, and cheetahs, among many other cervids (Zumpt and Ledger, 1973; Mwanzia et al., 1995; Graczyk et al., 2001; Alasaad et al., 2012a), and Australian wildlife that are affected are primarily wombats, wallabies, and dingoes (Fraser et al., 2016; Skerratt et al., 1998). This contrasts with North America where sarcoptic mange in cervids and bovids is rare, but rather these taxa tend to develop mange due to Chorioptes or Psoroptes while felids develop mange due to Notoedres cati (Bates, 1999; Nemeth et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2016). A summary of the species documented to be infested by S. scabiei in North America is described in Table 1. In some reports, morphological features specific to S. scabiei were not thoroughly described, and there is possibility of mis-identification. Astorga et al. (2018) also provide a map showing the distribution of hosts in North America documented to have sarcoptic mange.

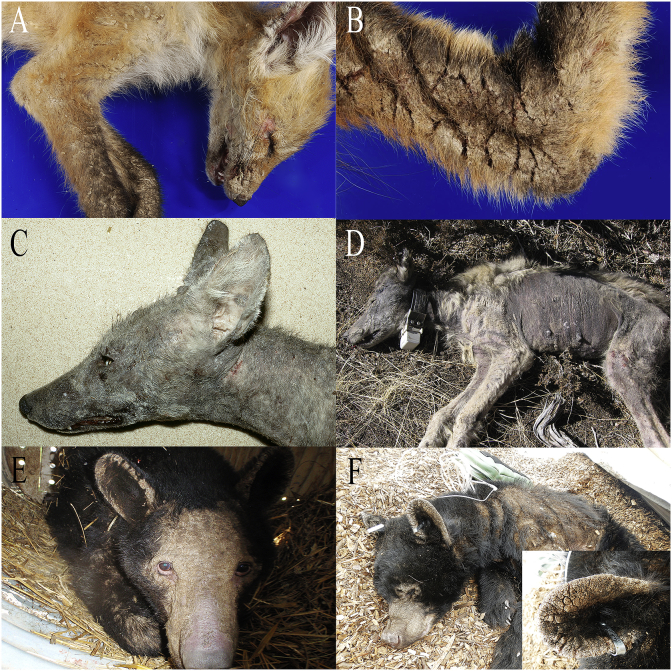

Fig. 3.

North American mammals with clinical sarcoptic mange. (A) Red fox with lesions on the face. (B) The same red fox showing a close up of the hyperkeratosis fissures in the skin. (C) Coyote with alopecia on the head and neck. (D) Gray wolf showing alopecia on the head, flanks, and hind limbs (Photo credit: Yellowstone Wolf Project/National Park Service). (E) Black bear in a culvert trap showing severe alopecia and skin thickening on the face, ears, and forelimb. (F) Black bear showing additional crusting and alopecia on the ears, flank, and muzzle; inset: close-up of hyperkeratotic and crusted skin.

Table 1.

Published host records and selected geographic records for Sarcoptes scabiei in free-ranging North American wildlife.

| Host | State/Province | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Canidae | ||

| Kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica) | California, USA | Cypher et al. (2017) |

| Gray wolf (Canis lupus) | Alberta, Canada | Gunson (1992) |

| Multiple States, USA | Wydeven et al. (1995) | |

| Wisconsin, USA | Wydeven et al. (2003) | |

| Montana/Wyoming, USA | Jimenez et al. (2010) | |

| Multiple States, USA | Almberg et al. (2012) | |

| Alaska, USA | Cross et al. (2016) | |

| Coyote (Canis latrans) | Wisconsin, USA | Trainer and Hale (1969) |

| Alberta, Canada | Todd et al. (1981) | |

| Louisiana/Texas, USA | Pence et al. (1981) | |

| Oklahoma/Wyoming/Kansas, USA | Morrison et al. (1982) | |

| Arizona, USA | Grinder and Krausman (2001) | |

| Kansas, USA | Kamler and Gipson (2002) | |

| South Dakota, USA | Chronert et al. (2007) | |

| Illinois, USA | (Wilson, 2012) | |

| Red wolf (Canis rufus) | Louisiana, USA | Pence et al. (1981) |

| Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) | Arizona, USA | Jimenez et al. (2010) |

| Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) | Ohio, USA | Olive and Riley (1948) |

| Pennsylvania, USA | Pryor (1956) | |

| Wisconsin, USA | Trainer and Hale (1969) | |

| New York | Stone (1974) | |

| Various states, USA | Storm et al. (1976) | |

| New Brunswick/Nova Scotia, Canada | Smith (1978) | |

| Various states, USA | Little et al. (1998a) | |

| Alberta, Canada | Vanderkop and Lowes (1992) | |

| Virginia, USA | Kelly and Sleeman (2003) | |

| Illinois, USA | Gosselink et al. (2007) | |

| Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) | New York, USA | Stone et al. (1982) |

| Pennsylvania, USA | Pryor (1956) | |

| Cervidae | ||

| White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) | Texas, USA | Brewster et al. (2017) |

| Ursidae | ||

| American black bear (Ursus americanus) | Michigan, USA | Schmitt et al. (1987) |

| Pennsylvania, USA | Peltier et al. (2017) | |

| Virginia, USA | Van Wick and Hashem (2019) | |

| Procyonidae | ||

| Raccoon (Procyon lotor) | Michigan, USA | Fitzgerald et al. (2004) |

| Mustelidae | ||

| Fisher (Martes pennanti) | Maine, USA | O'Meara et al. (1960) |

| Suidae | ||

| Feral swine (Sus scrofa) | Various southeastern states, USA | Smith et al. (1982) |

| Erethizontidae | ||

| North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) | Maine, USA | Payne and O'Meara (1958) |

| Pennsylvania, USA | Peltier et al. (2017) | |

| Sciuridae | ||

| Fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) | Michigan, USA | Fitzgerald et al. (2004) |

| Leporidae | ||

| Swamp rabbit (Sylvilagus aquaticus) | North Carolina, USA | Stringer et al. (1969) |

| Muridae | ||

| House mouse (Mus musculus) | New York, USA | Meierhenry and Clausen (1977) |

| Bovidae | ||

| Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis) | Western Canada | Cowan (1951) |

Early reports of epizootics in North American wildlife include outbreaks in red foxes in Ohio and Wisconsin (Olive and Riley, 1948; Trainer and Hale, 1969). The mite was likely introduced into Montana, USA and Alberta, Canada through the intentional use of the mite to control coyote and wolf populations (Knowles, 1909; Pence et al., 1983). In Montana, this ‘experiment’ was sanctioned by the state government and involved the State Veterinarian inoculating 200 wolves and coyotes in various counties in Montana; later, coyotes with suspected mange were reported in Wyoming, but it is unclear if the spread was related to the initial introduction (Knowles, 1909). Since then, mange has been observed in wild canids across the country and is considered endemic in many of these species (Almberg et al., 2012; Bornstein et al., 2001; Chronert et al., 2007; Kamler and Gipson, 2002; Little et al., 1998a).

In North America, populations of red foxes, coyotes, and gray wolves appear to experience epizootics every thirty to forty-five years (Pence and Windberg, 1994). Mild cases of mange have been recently reported in Texas in white-tailed deer but are presumed to not be contributing to morbidity or mortality (Brewster et al., 2017). There are several examples of sarcoptic mange in novel hosts in the North America. The federally endangered kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica) has increased mortality in an urban, high-density population in Bakersfield, California (Cypher et al., 2017; Rudd et al., 2019). The case fatality rate in this population may be as high as 100%.

4.2. Foxes

Red foxes are one of the most widespread canid species globally and are highly susceptible to sarcoptic mange (Little et al., 1998a). The majority of research on mange in red foxes has occurred in Europe, where the disease has affected this species since the late 1600s (Friedman, 1934). The red fox population in Bristol, United Kingdom (UK) is arguably the most studied fox population in the world, largely as a result of ongoing mange dynamics research in this group (Baker et al., 2000; Soulsbury et al., 2007). Several examples of severe red fox population impacts have been reported after the S. scabiei introduction or acute outbreaks, including the likely extinction of red foxes from a Danish island and severe population declines in Bristol, UK (Mӧrner, 1992; Henriksen et al., 1993; Lindstrom et al., 1994).

In North America, reports of mange in red foxes are often sporadic, isolated, and rarely associated with recognized severe population impacts. These reports are primarily limited to the eastern United States (Olive and Riley, 1948; Pryor, 1956; Trainer and Hale, 1969; Storm et al., 1976; Little et al., 1998a; Gosselink et al., 2007). In some of these studies, small declines in red fox numbers were reported after acute mange outbreaks, but there was also evidence of recovery of some affected individuals (Trainer and Hale, 1969; Storm et al., 1976).

Red foxes in urban settings in North America, similar to other continents, were more likely to develop disease and die from mange compared to rural populations, which may be influenced by exposure difference or detection bias (Gosselink et al., 2007; Soulsbury et al., 2007). Behavioral changes were reported in red foxes including a decline in activity, loss of fear of humans, and lower likelihood of dispersal (Trainer and Hale, 1969; Storm et al., 1976). Mortality can occur as quickly as 3–4 months following infection (Stone et al., 1972). Foxes with mange also generally are in worse nutritional condition compared to foxes without mange, and they lose more mass compared to affected coyotes and wolves (Trainer and Hale, 1969; Todd et al., 1981; Pence et al., 1983; Pence and Windberg, 1994; Newman et al., 2002; Davidson et al., 2008). In one study in the UK, foxes with mange survived one fifth as long as foxes without mange (Newman et al., 2002).

There are data to suggest that host-parasite adaptation can occur. Serologic testing of red foxes in Norway showed that the ratio of seropositive-mange negative foxes to seropositive-mange positive foxes increased significantly ten years following the initial outbreak confirming that either the fox or the parasite had adapted and fewer clinical cases were observed as a result (Davidson et al., 2008). This adaptation likely has or is occurring in North American foxes, but no studies have been performed in this continent. Interestingly, clinical sarcoptic mange is extremely rare in gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) despite this species being sympatric with red fox throughout much of the United States (Pryor, 1956; Stone et al., 1982; Davidson et al., 1992a,b). There are no known reports of mange in swift foxes (Vulpes velox), the reason for which is unknown.

4.3. Coyotes

Coyotes with sarcoptic mange have been reported in Alberta, Canada and Montana, USA since the early 1900's, southern Texas in the 1920s, and in the mid-western United States since the 1950's (Trainer and Hale, 1969; Pence et al., 1983; ). The expansion of sarcoptic mange in coyotes is possibly associated with the expanding populations of the host (Hody and Kays, 2018). Most of the recent publications regarding mange in coyotes in North America centered around urban populations in Edmonton, Canada and several outbreaks in southern Texas between 1975 and 1995. However, isolated reports or small epizootics of mange in coyotes have been reported in multiple areas of North America, including up to 25% of coyotes in British Columbia showing signs of mange (Cowan, 1951; Trainer and Hale, 1969; Stone et al., 1972; Grinder and Krausman, 2001; Kamler and Gipson, 2002; Chronert et al., 2007). Mange has likely occurred in most areas where coyotes exist in North America.

Several studies have looked at behavior changes in coyotes with mange. Coyotes with mange showed less avoidance of residential areas, particularly during the day, and preferred resource sites with anthropogenic food and bedding sources compared to individuals without mange (Murray and St Clair, 2017). In one study, coyotes with mange were more likely to use residential habitat prior to mange-induced mortality, particularly in the winter (Wilson, 2012). Coyotes with skin disease presumed to be from mange were more likely to access urban compost piles, had larger home ranges, and were more active during the day compared to clinically normal animals (Murray et al., 2015b; Murray et al., 2016). Other studies have shown that no differences in home range between coyotes with or without mange (Kamler and Gipson, 2002; Chronert et al., 2007). Similarly, coyotes with mange were not observed changing their home ranges between years (Chronert et al., 2007). Urban coyotes were more likely to have mange, be in poor physical condition, and were more likely to show conflict-prone behavior compared to rural coyotes (Murray et al., 2015a). Studies in other areas have shown that coyotes with mange stayed closer to carrion food sources than coyotes without mange, and carrion food sources made up a larger percentage of diet in coyotes with mange (Todd et al., 1981). Severely affected individuals were shown to be listless and lacked appropriate fear of humans (Trainer and Hale, 1969). During mange outbreaks, coyotes were less likely to reproduce compared to years with less mange (Pence et al., 1983).

Pence and Windberg described two epizootics of mange in coyotes in southern Texas (Pence et al., 1983; Pence and Windberg, 1994). At the peak of the epizootic in the early 1980s and 1990s, as many as 60 and 80% of coyotes in southern Texas had mange, respectively, depending on the year (Pence et al., 1983; Pence and Windberg, 1994). Despite over 70% mortality occurring in one study, no long-term population impacts were apparent (Pence and Windberg, 1994). Variation likely occurs however, as the percentage of coyotes with mange at the peak of an epizootic in another study was 32% (Kamler and Gipson, 2002). These studies hypothesized that the outbreaks were cyclical and were caused by a virulent strain of the mites enhanced by a high coyote density and social behaviors, although no genetic analyses were performed on the mites. One study followed a clinically-normal male coyote that mated with a female coyote with mange. The male never developed any signs of mange, suggesting some animals are exposed but do not develop observable disease (Kamler and Gipson, 2002). A study of urban coyotes in Chicago, Illinois (USA) showed that mange was endemic in the population and did not affect annual survival rates (Wilson, 2012).

In multiple studies, the number of cases of healing/resolving mange in coyotes was low suggesting either high mortality in severely affected animals that do not recover or that coyotes are less susceptible to severe disease compared to red foxes (Todd et al., 1981; Pence et al., 1983). However, multiple cases of coyotes with mange that survive have been reported, and mild disease can likely occur in this species (Pence and Windberg, 1994; Chronert et al., 2007). Coyotes could also be exposed to mites without infestation becoming established, further complicating estimations of mortality rate. Mange-specific mortality varied across studies but was as high as 55% in one study in South Dakota (Pence et al., 1983; Chronert et al., 2007). Other studies have suggested that mange in coyotes was highest when population numbers were high and were immediately followed by sharp declines suggesting a density-dependent relationship (Gier et al., 1978; Todd et al., 1981). However, this relationship was not shown by Pence and others (1983). Adult male coyotes appear to be more likely to have mange than other sexes age-sex categories (Todd et al., 1981; Pence et al., 1983).

4.4. Wolves

Mange has been reported in gray wolves, Mexican wolves (C. lupus baileyi), and red wolves (Canis rufus) in North America since as early as 1889 but was likely present before this time (Todd et al., 1981; Jimenez et al., 2010). In Alberta, Canada during the 1970s, mange in gray wolves varied greatly between regions and years, and mange was implicated as limiting population growth during this time period (Gunson, 1992). Additionally, both wolves and coyotes had a higher prevalence of mange than the more commonly and severely affected red foxes. Sarcoptic mange was reported in wolves in the Midwestern USA in the 1990s and in the northern Rocky Mountains in the early 2000s (Jimenez et al., 2010).

Sarcoptic mange was first reported in wolves in Yellowstone National Park (YNP) in January 2007 (Smith and Almberg, 2007). Almberg et al. (2012) reported that mange spread outward following the initial introduction in YNP with highest risk of infection in packs closest to the index pack. Mange was reportedly highest in Yellowstone wolves during the winter months and dipped in the summer (Almberg et al., 2015). Additionally, pack size did not appear to be a risk factor for development of sarcoptic mange (rather, pack size appeared protective), but prevalence within a pack did seem to positively influence risk of transmission. In one study, no support was found for age, sex, or coat color as a risk factor for disease, and being previously infested was not associated with reduced risk of future infestations, which contrasts with data from Iberian wolves (C. lupus signatus) in Spain where yearlings were least likely to be diseased compared to adults and pups (Oleaga et al., 2011; Almberg et al., 2015). In another study, wolf pups had a higher prevalence of mange in years where overall mange in the entire population was reduced (Todd et al., 1981). In Alberta, peaks of sarcoptic mange in wolves followed peaks of mange in coyotes by one year (Todd et al., 1981).

With social species, transmission is thought to occur more frequently within the group rather than between different groups as reported in the Yellowstone National Park wolf packs (Almberg et al., 2012). The overall spatial spread of the disease is consistent with pack to pack spread rather than repeated spillover events from outside of YNP. However, the spread of mange appeared to be highly variable within individual packs with some consistently presenting with low prevalence and severity while others suffered from rapid spread and high severity (Almberg et al., 2012). Coyotes also confirmed to have mange in wolf habitats possibly contributed to spreading the pathogen directly or indirectly (Jimenez et al., 2010).

Changes in wolf behavior have been observed after the development of clinical disease potentially due to the increased metabolic demands associated with infestation and thermoregulation due to hair loss (Shelly and Gehring, 2002). Wolves became weak and withdrew from the pack, stayed in areas of lower elevation and less snow, sought out shelter in rural areas near humans, and scavenged carcasses rather than wasting energy hunting (Jimenez et al., 2010). Gray wolves with sarcoptic mange and subsequent hair loss have been shown to have a reduced ability to maintain appropriate thermoregulation. These physiologic changes result in an increased energy demand in clinically-affected wolves and results in wolves compensating by reducing their movement or only moving during warmer times of the day (Cross et al., 2016). One report of wolves using porcupine dens in Wisconsin suggests that in extreme situations, animals with severe mange will seek out abnormal den sites (Wydeven et al., 2003). Wolves with clinical disease were reportedly more likely to consume carrion than hunt for live prey compared to clinically-normal animals, and wolves being tracked also reduced their movements after severe disease developed (Shelly and Gehring, 2002). Similar to coyotes, wolves had significantly less body fat and kidney fat if affected with mange compared to wolves without mange, although to a lesser extent (Todd et al., 1981). Wolves and coyotes with mange had between 4 and 22% less body mass compared to animals without mange based on the severity of the disease (Todd et al., 1981).

Multiple studies have shown that pup recruitment was significantly reduced when mange was prevalent in a wolf population (Todd et al., 1981; Jimenez et al., 2010). Mange was also implicated as being a potential cause for pack dissolution and negative growth rates in pack size (Almberg et al., 2012). The risk of mortality from mange decreased as the size of the pack increased, particularly if the pack-mates were mange-free, and as the elk-to-wolf ratio increased. Solitary animals with mange were at higher risk of mortality than those in a pack, and that a large pack size resulted in higher survival of wolves with mange (Almberg et al., 2015). The overall mange-associated mortality in North American wolves is unknown but estimates range between 27 and 34% in the midwestern USA but is estimated at 5.6% in Swedish wolves (Jimenez et al., 2010; Fuchs et al., 2016).

It was noted that not all wolves infested died from the disease or its secondary effects impacts, as survivability depended on disease severity and seasonal variation. Though many individual wolves died from mange or mange-related complications, only a few wolf packs in a few specific areas of Wyoming and Montana were impacted (Jimenez et al., 2010). Wolves in Sweden in southern populations are more likely to have antibodies to S. scabiei, which may be related to their smaller territories in southern latitudes, as was observed in YNP in the USA, and the higher densities of red foxes (Almberg et al., 2012; Fuchs et al., 2016). Packs of gray wolves in Sweden show that individual animals with clinical disease are often in contact with clinically-normal animals without antibodies to S. scabiei, which suggests unknown factors contribute to disease development in some individuals or in some packs (Fuchs et al., 2016). However, several packs in close approximation to those with active mange remained mange-free, and similarly packs a larger distance from those with mange ultimately developed the disease, possibly from infested lone dispersers (Almberg et al., 2012). One study also showed that juveniles are more likely to be clinically-affected than older adults similar to other species such as red foxes (Todd et al., 1981; Pence et al., 1983; Newman et al., 2002). Currently the northern mountain range wolf population continues to increase annually despite the spread of mange in the population (Jimenez et al., 2010).

4.5. Bears

Historically, American black bears were not considered a typical host for S. scabiei, and mange was rarely reported in North America (Bornstein et al., 2001). A study describing three bears with sarcoptic mange in Michigan was the first report in 1984, and another isolated case was reported in Michigan in 2008 co-infected with the nematode Pelodera strongyloides (Schmitt et al., 1987; Fitzgerald et al., 2008). Numerous bears in New Mexico were observed to have dermatitis and hair loss but the cause of these lesions was not determined and was not associated with severe morbidity or mortality (Costello et al., 2006). Beginning in the early 1990s, sarcoptic mange began to be more frequently detected in black bears in Pennsylvania (Sommerer, 2014). Since then, the disease has expanded outward into New York, West Virginia, Virginia, and Maryland, and is a regular cause of morbidity and mortality in this region (Niedringhaus et al., 2019b).

The emergence of sarcoptic mange in bears is new relative to other species, and limited research on mange in bears has been performed. While urban areas are often associated with mange in other hosts, particularly canids, there was no association with impervious land cover and the likelihood of clinical mange in black bears (Gosselink et al., 2007; Soulsbury et al., 2007; Sommerer, 2014; Murray et al., 2015b). Genetic studies on the mites from bears in Pennsylvania and surrounding states indicated there are several haplotypes circulating in bears in the affected region, but a unique bear-specific genotype was not identified, although only two gene targets were investigated (Peltier et al., 2017). When diagnosing clinical mange in bears, skin scrapes appeared to be the most sensitive method for mite detection and identification, as previously mentioned, likely due to the high numbers of mites on bears compared to some other hosts (Peltier et al., 2018). Bears, unlike many other mange-susceptible hosts, are not a social species for much of the year, and transmission dynamics and outbreak epidemiology between individual bears are likely different compared to other hosts. Additional research in this system will help our understanding of mite adaptability, transmission, and host susceptibility. There are no known reports of sarcoptic mange in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) or grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) to the authors’ knowledge.

5. Conclusions

The severity of sarcoptic mange on wildlife populations is highly variable but has potential to cause severe impacts in naïve and susceptible populations. Sarcoptes scabiei has an unprecedented ability to cause disease in a wide host range involving taxa from five orders of mammals from North America. The continued expansion of hosts reported to develop this disease warrants continued research to better understand host susceptibility and disease epidemiology. Specifically, advances in modelling techniques that better quantify mange impacts on wildlife populations in North America, similar to what has been suggested for bare-nosed wombats in Australia, can provide valuable data on potential population effects, particularly since the impact on many species is likely under-appreciated due to general lack of surveillance (Beeton et al., 2019). Expanding hosts for S. scabiei could result in a similar expansion of the parasite and potential spillover into aberrant hosts. Additionally, anthropogenic effects on the environment, including climate change, increased contact with humans, domestic animals, and wild animals, and changes in environmental health may all contribute to mange outbreaks and host susceptibility. Decisions regarding mange management in wildlife populations requires a thorough evaluation of the risks and benefits of each management option while considering that taking no action may sometimes be the most appropriate. Factors that should be considered in any potential management decision include individual animal welfare, the conservation status of the species affected, and responsible treatment protocols.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Pennsylvania Game Commission and former diagnosticians at SCWDS for providing the gross and microscopic images. Funding was provided by the sponsorship of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study by the fish and wildlife agencies of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, USA. Support from the states to SCWDS was provided in part by the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Act (50 Stat. 917). Graphical abstract was created by S.G.H. Sapp (Creepy Collie Creative).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.06.003.

Contributor Information

Kevin D. Niedringhaus, Email: kevindn@uga.edu.

Michael J. Yabsley, Email: myabsley@uga.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alasaad S., Ndeereh D., Rossi L., Bornstein S., Permunian R., Soriguer R.C., Gakuya F. The opportunistic Sarcoptes scabiei: a new episode from giraffe in the drought-suffering Kenya. Vet. Parasit. 2012;185:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasaad S., Permunian R., Gakuya F., Mutinda M., Soriguer R.C., Rossi L. Sarcoptic-mange detector dogs used to identify infected animals during outbreaks in wildlife. BMC Vet. Res. 2012;8:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasaad S., Soglia D., Spalenza V., Maione S., Soriguer R.C., Perez J.M., Rasero R., Degiorgis M.P., Nimmervoll H., Zhu X.Q., Rossi L. Is ITS-2 rDNA suitable marker for genetic characterization of Sarcoptes mites from different wild animals in different geographic areas? Vet. Parasitol. 2009;159:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasaad S., Walton S., Rossi L., Bornstein S., Abu-Madi M., Soriguer R.C., Heukelbach J. Sarcoptes-world molecular network (Sarcoptes-WMN): integrating research on scabies. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;15:e294–e297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almberg E.S., Cross P.C., Dobson A.P., Smith D.W., Hudson P.J. Parasite invasion following host reintroduction: a case study of Yellowstone's wolves. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2012;367:2840–2851. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almberg E.S., Cross P.C., Dobson A.P., Smith D.W., Metz M.C., Stahler D.R., Hudson P.J. Social living mitigates the costs of a chronic illness in a cooperative carnivore. Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:660–667. doi: 10.1111/ele.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelone-Alasaad S., Molinar Min A., Pasquetti M., Alagaili A.N., D'Amelio S., Berrilli F., Obanda V., Gebely M.A., Soriguer R.C., Rossi L. Universal conventional and real-time PCR diagnosis tools for Sarcoptes scabiei. Parasit. Vectors. 2015;8:587. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1204-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas A.J., Gomez F., Salas R., Carrasco P., Borge C., Maldonado A., O'Brien D.J., Martinez-Moreno F.J. An evaluation of the application of infrared thermal imaging to the tele-diagnosis of sarcoptic mange in the Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) Vet. Parasitol. 2002;109:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends J.J., Stanislaw C.M., Gerdon D. Effects of sarcoptic mange on lactating swine and growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1990;68:1495–1499. doi: 10.2527/1990.6861495x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Runyan R.A., Achar S., Estes S.A. Survival and infestivity of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis and var. hominis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984;11:210–215. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Runyan R.A., Estes S.A. Cross infestivity of Sarcoptes scabiei. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984;10:979–986. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Runyan R.A., Sorlie L.B., Estes S.A. Host-seeking behavior of Sarcoptes scabiei. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984;11:594–598. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Runyan R.A., Sorlie L.B., Vyszenski-Moher D.L., Estes S.A. Characterization of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis (Acari: Sarcoptidae) antigens and induced antibodies in rabbits. J. Med. Entomol. 1985;22:321–323. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/22.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Vyszenski-Moher D.L. Life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis. J. Parasitol. 1988;74:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Estes S.A., Vyszenski-Moher D.L. Prevalence of Sarcoptes scabiei in the homes and nursing homes of scabietic patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1988;19:806–811. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Vyszenski-Moher D.L., Cordova D. Host specificity of S. scabiei var. canis (Acari: Sarcoptidae) and the role of host odor. J. Med. Entomol. 1988;25:52–56. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/25.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G. Biology, host relations, and epidemiology of Sarcoptes scabiei. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1989;34:139–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.34.010189.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Vyszenski-Moher D.L., Pole M.J. Survival of adults and development stages of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis when off the host. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1989;6:181–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01193978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Morgan M.S., Estes S.A., Walton S.F., Kemp D.J., Currie B.J. Circulating IgE in patients with ordinary and crusted scabies. J. Med. Entomol. 2004;41:74–77. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Feldmeier H., Morgan M.S. The potential for a blood test for scabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlian L.G., Morgan M.S. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:297. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astorga F., Carver S., Almberg E.S., Sousa G.R., Wingfield K., Niedringhaus K.D., Van Wick P., Rossi L., Xie Y., Cross P., Angelone S., Gortazar C., Escobar L.E. International meeting on sarcoptic mange in wildlife, June 2018, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Parasit. Vectors. 2018;11:449. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla R.S., Singla L.D., Juyal P.D., Gupta P.P. Prevalence and pathology of mange- mite infestations in dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;14:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Baker P.J., Funk S.M., Harris S., White P.C.L. Flexible spatial organization of urban foxes, Vulpes vulpes, before and during an outbreak of sarcoptic mange. Anim. Behav. 2000;59:127–146. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates P.G. Inter- and intra-specific variation within the genus Psoroptes (Acari: Psoroptidae) Vet. Parasitol. 1999;83:201–217. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becskei C., De Bock F., Illambas J., Cherni J.A., Fourie J.J., Lane M., Mahabir S.P., Six R.H. Efficacy and safety of a novel oral isoxazoline, sarolaner (Simparica), for the treatment of sarcoptic mange in dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;222:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeton N.J., Carver S., Forbes L.K. A model for the treatment of environmentally transmitted sarcoptic mange in bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus) J. Theor. Biol. 2019;462:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrilli F., D'Amelio S., Rossi L. Ribosomal and mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Sarcoptes mites from different hosts and geographical regions. Parasitol. Res. 2002;88:772–777. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0655-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beugnet F., de Vos C., Liebenberg J., Halos L., Larsen D., Fourie J. Efficacy of afoxolaner in a clinical field study in dogs naturally infested with Sarcoptes scabiei. Parasite. 2016;23:26. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2016026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchard P., Eldridge D.J., Wright I.A. Sarcoptes mange (Sarcoptes scabiei) increases diurnal activity of bare-nosed wombats (Vombatus ursinus) in an agricultural riparian environment. Mamm. Biol. 2012;77:244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S. Experimental infection of dogs with Sarcoptes scabiei derived from naturally infected wild red foxes (Vulpes vulpes): clinial observations. Vet. Dermatol. 1991;2:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Frossling J., Naslund K., Zakrisson G., Mӧrner T. Evaluation of a serological test (indirect ELISA) for the diagnosis of sarcoptic mange in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Vet. Dermatol. 2006;17:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2006.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Mӧrner T., Samuel W.M. Sarcoptes scabiei and sarcoptic mange. In: Samuel W.M., Pybus M.J., Kocan A.A., editors. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Mammals. Iowa State Press; Ames, IA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Thebo P., Zakrisson G. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the serological diagnosis of canine sarcoptic mange. Vet. Dermatol. 1996;7:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.1996.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Zakrisson G. Clinical picture and antibody response in pigs infected by Sarcoptes scabiei var. suis. Vet. Dermatol. 1993;4:123–131. doi: 10.1186/BF03547665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Zakrisson G. Humoral antibody response to experimental Sarcoptes scabiei var. vulpes infection in the dog. Vet. Dermatol. 1993;4:107–110. doi: 10.1186/BF03547665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein S., Zakrisson G., Thebo P. Clinical picture and antibody response to experimental Sarcoptes scabiei var. vulpes infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Acta Vet. Scand. 1995;36:509–519. doi: 10.1186/BF03547665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster K., Henke S.E., Hilton C., Ortega S.A., Jr. Use of remote cameras to monitor the potential prevalence of sarcoptic mange in southern Texas, USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 2017;53:377–381. doi: 10.7589/2016-08-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargill C.F., Dobson K.J. Experimental Sarcoptes scabiei infestation in pigs: (1) pathogenesis. Vet. Rec. 1979;104:11–14. doi: 10.1136/vr.104.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargill C.F., Dobson K.J. Experimental Sarcoptes scabiei infestation in pigs: (2) effects on production. Vet. Rec. 1979;104:33–36. doi: 10.1136/vr.104.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carricondo-Sanchez D., Odden M., Linnell J.D.C., Odden J. The range of the mange: Spatiotemporal patterns of sarcoptic mange in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) as revealed by camera trapping. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosidow O. Scabies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1718–1727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronert J.M., Jenks J.A., Roddy D.E., Wild M.A., Powers J.G. Effects of sarcoptic mange on coyotes at wind cave national Park. J. Wildl. Manag. 2007;71:1987–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Colloff M.J., Spieksma F.T. Pictorial keys for the identification of domestic mites. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1992;22:823–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello C.M., Quigley K.S., Jones D.E., Inman R.M., Inman K.H. Observations of a denning-related dermatitis in American black bears. Ursus. 2006;17:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan I.M. Proceedings of the 5th Annual Game Convention. British Columbia; Victoria: 1951. The diseases and parasites of big game mammals of western Canada; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cross P.C., Almberg E.S., Haase C.G., Hudson P.J., Maloney S.K., Metz M.C., Munn A.J., Nugent P., Putzeys O., Stahler D.R., Stewart A.C., Smith D.W. Energetic costs of mange in wolves estimated from infrared thermography. Ecology. 2016;97:1938–1948. doi: 10.1890/15-1346.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie B.J., Harumal P., McKinnon M. First documentation of in vivo and in vitro ivermectin resistance in Sarcoptes scabiei. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39:E8–E12. doi: 10.1086/421776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier R.W., Walton S.F., Currie B.J. Scabies in animals and humans: history, evolutionary perspectives, and modern clinical management. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1230:E50–E60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C. Canine sarcoptic mange (sarcoptic acariasis, canine scabies) Companion Anim. 2012;17:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C.F. Current trends in the treatment of Sarcoptes, Cheyletiella and Otodectes mite infestations in dogs and cats. Vet. Dermatol. 2004;15:108–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2004.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypher B.L., Rudd J.L., Westall T.L., Woods L.W., Stephenson N., Foley J.E., Richardson D., Clifford D.L. Sarcoptic mange in endangered kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis mutica): case histories, diagnoses, and implications for Conservation. J. Wildl. Dis. 2017;53:46–53. doi: 10.7589/2016-05-098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.K., Bornstein S., Handeland K. Long-term study of Sarcoptes scabiei infection in Norwegian red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) indicating host/parasite adaptation. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;156:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson W.R., Appel M.J., Doster G.L., Baker O.E., Brown J.F. Diseases and parasites of red foxes, gray foxes, and coyotes from commercial sources selling to fox-chasing enclosures. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:581–589. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson W.R., Nettles V.F., Hayes L.E., Howerth E.W., Couvillion C.E. Diseases diagnosed in gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) from the southeastern United States. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:28–33. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D.P., Moon R.D. Dynamics of swine mange - a critical-review of the literature. J. Med. Entomol. 1990;27:727–737. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desch C.E. Acarology Proceedings of the 10th International Congress. 2001. Anatomy and ultrastructure of the female reproductive system of Sarcoptes scabiei (Acari: Sarcoptidae) pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Desch C.E., Jr. A new species of Demodex (Acari: Demodecidae) from the black bear of North America, Ursus americanus pallas, 1780 (Ursidae) Int. J. Acarol. 2009;21:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Devenish-Nelson E.S., Richards S.A., Harris S., Soulsbury C., Stephens P.A. Demonstrating frequency-dependent transmission of sarcoptic mange in red foxes. Biol. Lett. 2014;10:1–5. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez G., Espi A., Prieto J.M., De La Torre J.A. Sarcoptic mange in Iberian wolves (Canis lupus signatus) in northern Spain. Vet. Rec. 2008;162:754–755. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.23.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder B.L., Arlian L.G., Morgan M.S. Sarcoptes scabiei (Acari: Sarcoptidae) mite extract modulates expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules by human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. J. Med. Entomol. 2006;43:910–915. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[910:ssasme]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston C.A., Elston D.M. Demodex mites. Clin. Dermatol. 2014;32:739–743. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa V.O., Ghai R.R., Mckay A.F., Williams A.E. Group living and pathogen infection revisited. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016;12:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fain A. Étude de la variabilité de Sarcoptes scabiei avec une révision des Sarcoptidae. Acta Zool. Pathol. Antverp. 1968;47:1–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fain A. Epidemiological problems of scabies. Int. J. Dermatol. 1978;17:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1978.tb06040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain A. Origin, variability, and adaptability of Sarcoptes scabiei. In: Dusbabek F., Bukva V., editors. Modern Acarology. SPB Academic Publishing, The Hague, and Academia; Prague: 1991. pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Moran J., Gomez S., Ballesteros F., Quiros P., Benito J.L., Feliu C., Nieto J.M. Epizootiology of sarcoptic mange in a population of cantabrian chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica parva) in northwestern Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 1997;73:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K., Holt D.C., Harumal P., Currie B.J., Walton S.F., Kemp D.J. Generation and characterization of cDNA clones from Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis for an expressed sequence tag library: identification of homologues of house dust mite allergens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;68:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald S.D., Cooley T.M., Cosgrove M.K. Sarcoptic mange and pelodera dermatitis in an American black bear (Ursus americanus) J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2008;39:257–259. doi: 10.1638/2007-0071R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald S.D., Cooley T.M., Murphy A., Cosgrove M.K., King B.A. Sarcoptic mange in raccoons in Michigan. J. Wildl. Dis. 2004;40:347–350. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-40.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley J., Serieys L.E.K., Stephenson N., Riley S., Foley C., Jennings M., Wengert G., Vickers W., Boydston E., Lyren L., Moriarty J., Clifford D.L. A synthetic review of notoedres species mites and mange. Parasitology. 2016;143:1847–1861. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T.A., Charleston M., Martin A., Polkinghorne A., Carver S. The emergence of sarcoptic mange in Australian wildlife: an unresolved debate. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1578-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T.A., Martin A., Polkinghorne A., Carver S. Comparative diagnostics reveals PCR assays on skin scrapings is the most reliable method to detect Sarcoptes scabiei infestations. Vet. Parasitol. 2018;251:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser T.A., Carver S., Martin A.M., Mounsey K., Polkinghorne A., Jelocnik M. A Sarcoptes scabiei specific isothermal amplification assay for detection of this important ectoparasite of wombats and other animals. PeerJ. 2018;6 doi: 10.7717/peerj.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R. The story of scabies. Med. Life. 1934;41:381–424. [Google Scholar]

- Fthenakis G.C., Karagiannidis A., Alexopoulos C., Brozos C., Papadopoulos E. Effects of sarcoptic mange on the reproductive performance of ewes and transmission of Sarcoptes scabiei to newborn lambs. Vet. Parasitol. 2001;95:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(00)00417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B., Zimmermann B., Wabakken P., Bornstein S., Mansson J., Evans A.L., Liberg O., Sand H., Kindberg J., Agren E.O., Arnemo J.M. Sarcoptic mange in the Scandinavian wolf Canis lupus population. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0780-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama S., Nishimura T., Yotsumoto H., Gushi A., Tsuji M., Kanekura T., Matsuyama T. Diagnostic usefulness of a nested polymerase chain reaction assay for detecting Sarcoptes scabiei DNA in skin scrapings from clinically suspected scabies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010;163:892–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller L.C. Epidemiology of scabies. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013;26:123–126. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835eb851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakuya F., Rossi L., Ombui J., Maingi N., Muchemi G., Ogara W., Soriguer R.C., Alasaad S. The curse of the prey: sarcoptes mite molecular analysis reveals potential prey-to-predator parasitic infestation in wild animals from Masai Mara, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors. 2011;4:193. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaverni M., Palumbo D., Fabbri E., Caniglia R., Greco C., Randi E. Monitoring wolves (Canis lupus) by non-invasive genetics and camera trapping: a small-scale pilot study. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2012;58:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gier H.T., Kruckenberg S.M., Marler R.J. Parasites and diseases of coyotes. In: Bekoff M., editor. Coyotes, biology, behavior, and management. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 37–71. [Google Scholar]

- Goltsman M., Kruchenkova E.P., Macdonald D.W. The Mednyi Arctic foxes: treating a population imperilled by disease. Oryx. 1996;30:251–258. [Google Scholar]