Positive-strand RNA viruses produce vast amounts of progeny in very short periods of time via template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms. Template-dependent RNA replication, while efficient, can be disadvantageous due to error-prone viral polymerases. The accumulation of mutations in viral RNA genomes leads to error catastrophe. In this study, we substantiate long-held theories regarding the advantages and disadvantages of asexual and sexual replication strategies among RNA viruses. In particular, we show that picornavirus RNA recombination counteracts the negative consequences of asexual template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms, namely, error catastrophe.

KEYWORDS: RNA polymerases, RNA recombination, asexual RNA replication, error catastrophe, picornavirus, ribavirin, sexual RNA replication

ABSTRACT

Template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms render picornaviruses susceptible to error catastrophe, an overwhelming accumulation of mutations incompatible with viability. Viral RNA recombination, in theory, provides a mechanism for viruses to counteract error catastrophe. We tested this theory by exploiting well-defined mutations in the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP), namely, a G64S mutation and an L420A mutation. Our data reveal two distinct mechanisms by which picornaviral RDRPs influence error catastrophe: fidelity of RNA synthesis and RNA recombination. A G64S mutation increased the fidelity of the viral polymerase and rendered the virus resistant to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe, but only when RNA recombination was at wild-type levels. An L420A mutation in the viral polymerase inhibited RNA recombination and exacerbated ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. Furthermore, when RNA recombination was substantially reduced by an L420A mutation, a high-fidelity G64S polymerase failed to make the virus resistant to ribavirin. These data indicate that viral RNA recombination is required for poliovirus to evade ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. The conserved nature of L420 within RDRPs suggests that RNA recombination is a common mechanism for picornaviruses to counteract and avoid error catastrophe.

IMPORTANCE Positive-strand RNA viruses produce vast amounts of progeny in very short periods of time via template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms. Template-dependent RNA replication, while efficient, can be disadvantageous due to error-prone viral polymerases. The accumulation of mutations in viral RNA genomes leads to error catastrophe. In this study, we substantiate long-held theories regarding the advantages and disadvantages of asexual and sexual replication strategies among RNA viruses. In particular, we show that picornavirus RNA recombination counteracts the negative consequences of asexual template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms, namely, error catastrophe.

INTRODUCTION

RNA viruses are outstanding tools to study the molecular basis of mutation and selection due to their template-dependent replication mechanisms, their error prone polymerases, their ability to produce vast amounts of genetically diverse progeny in very short periods of time, and the strong selection for efficiently replicating progeny (1, 2). Consequences of template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms and error prone polymerases are a loss of fitness after repeated genetic bottlenecks (3) and error catastrophe (4), an overwhelming accumulation of mutations in viral RNA genomes incompatible with viability. Viral RNA recombination, a form of sexual replication (5) wherein progeny are produced from more than one parental genome (6, 7), likely arose to counteract the negative consequences of asexual template-dependent RNA replication mechanisms, namely, error catastrophe (5, 8–10). Viral RNA recombination is advantageous because it can purge deleterious mutations while enriching beneficial mutations in viral genomes (8–10). In this study, we explore the relationship between viral RNA recombination and error catastrophe.

Picornaviruses, along with other RNA viruses, arose before the radiation of eukaryotic supergroups (11, 12). Viral RNA recombination contributed to viral evolution in ancient times and remains important today, where it shapes and maintains picornavirus species groups (13–15). Because viral RNA recombination is a natural aspect of virus replication, we sought to define polymerase features that mediate viral RNA recombination. An L420A mutation in the poliovirus polymerase significantly reduces RNA recombination without any deleterious effects on template-dependent RNA replication or virus production (16). Thus, poliovirus with an L420A mutation has normal asexual RNA replication mechanisms but is defective for sexual RNA replication/recombination. In this study, we examine how this L420A polymerase mutation impacts error catastrophe.

Ribavirin, a mutagenic antiviral drug, restricts poliovirus replication via error catastrophe (17, 18). As a nucleoside analog prodrug, ribavirin is converted into ribavirin triphosphate in cells and used as a substrate by the polymerase during viral RNA replication, where it can be incorporated opposite cytosine or uracil on the template strand (19). The incorporation of ribavirin into viral RNA induces G-to-A and C-to-U transition mutations during subsequent rounds of RNA replication (4). Ribavirin-induced error catastrophe arises when the accumulation of mutations in viral RNA become incompatible with viability. A G64S mutation in poliovirus polymerase mediates ribavirin resistance by increasing viral polymerase fidelity, reducing the number of ribavirin-induced mutations in viral RNA (20). In this study, we assess how a G64S polymerase mutation impacts viral RNA recombination and ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

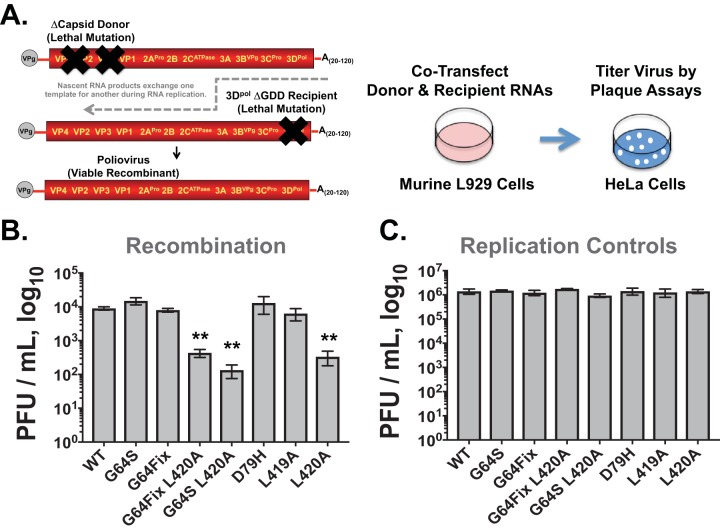

The ability of viral RNA recombination to counteract error catastrophe is theoretically sound (8–10); however, there is conflicting evidence in the literature (Fig. 1). Previously, we found that an L420A mutation in the poliovirus polymerase inhibits RNA recombination while exacerbating ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (16). In contrast, the Andino lab reported that a D79H polymerase mutation inhibits RNA recombination but without impacting ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (10). Due to these conflicting reports, we further investigated the relationship between RNA recombination and ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. Our data indicate that RNA recombination counteracts error catastrophe, substantiating theories regarding the advantages and disadvantages of asexual and sexual RNA replication strategies (2, 5, 8).

FIG 1.

Conflicting evidence regarding viral RNA recombination and error catastrophe. (A) Xiao et al. report that a D79H mutation in poliovirus polymerase inhibits viral RNA recombination but has no effect on ribavirin-induced error catastrophe, whereas Kempf et al. report that an L420A mutation in the poliovirus polymerase inhibits viral RNA recombination and exacerbates ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (10, 16). (B) Locations of D79H and L420A mutations in poliovirus polymerase. Poliovirus polymerase PDB entry 4K4T rendered using the PyMOL molecular graphics system (Schrödinger, LLC). Polymerase is shown in green with D79H (red on left) and L420A (red on right) mutations; the active site GDD residues (fuchsia), template (blue), and product (yellow) RNAs indicated in color.

RESULTS

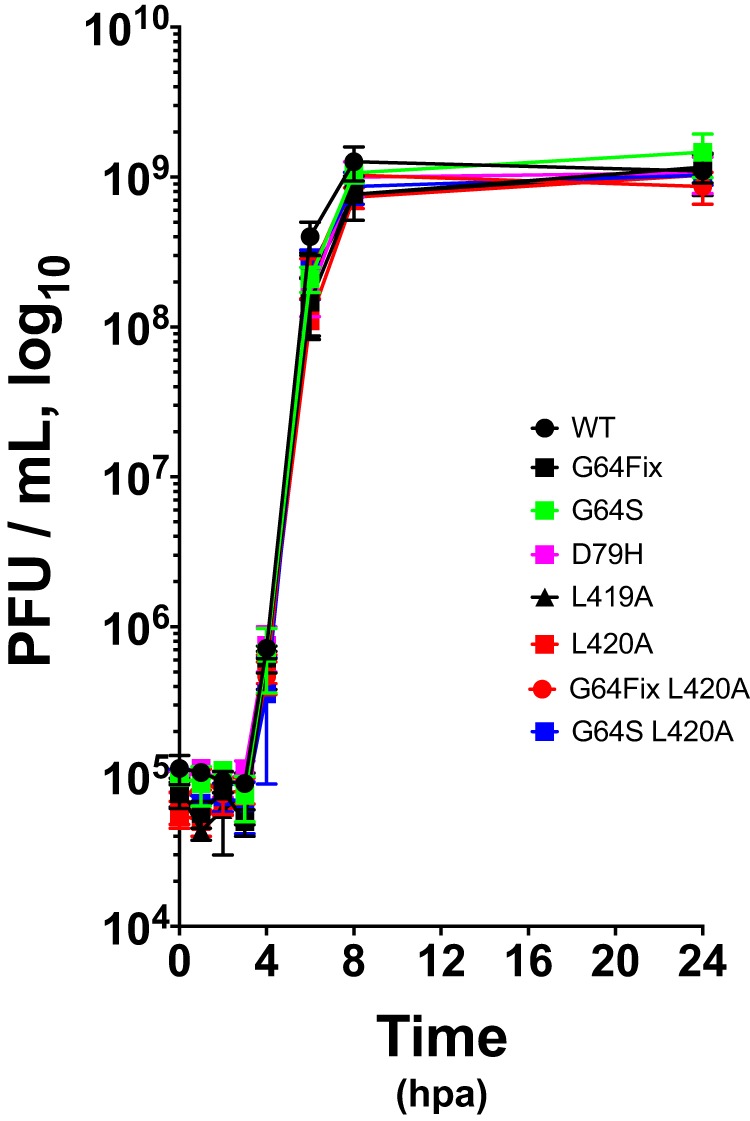

One-step growth of wild-type and mutant viruses.

Before addressing the relationship between viral RNA recombination and error catastrophe, we investigated the one-step growth phenotypes of the wild-type and mutant viruses used in this investigation (Fig. 2). Wild-type (WT) poliovirus, along with seven mutant viruses, were used in the investigation: G64Fix, G64S, D79H, L419A, L420A, G64Fix L420A and G64S L420A. The emergence of the G64S ribavirin resistance mutation typically requires a single transition nucleotide change (GGUGly to AGUSer), and to prevent this, we engineered the G64Fix mutation as a GGG codon that requires two or three point mutations for conversion to serine which is encoded by AGC, AGU, UCA, UCC, UCG, or UCU. Viruses containing G64S, D79H, L419A, and L420A 3Dpol mutations have been reported in the literature (10, 16, 20, 21). For this investigation, we engineered new viruses containing both G64Fix L420A and G64S L420A 3Dpol mutations. All of these mutations were genetically stable in the viruses grown in HeLa cells, as confirmed by cDNA sequencing. Under one-step growth conditions, each of the viruses used in this investigation grew by 4 orders of magnitude between 4 and 8 h postadsorption (hpa), reaching titers ∼109 PFU per ml (Fig. 2). These data indicate that the wild-type and mutant viruses used in this investigation have similar one-step growth phenotypes. Other studies examined viral RNA synthesis by poliovirus containing G64S, L419A, and L420A 3Dpol mutations (21). The 3Dpol mutations used in this investigation are genetically stable within polioviruses and support viral RNA replication at rates and magnitudes comparable to wild-type polymerase.

FIG 2.

One-step growth of wild-type and mutant polioviruses. HeLa cells were infected with wild-type or mutant poliovirus at an MOI of 10 PFU per cell. Virus was harvested at the indicated times by freeze-thawing cells. Titers were determined by plaque assay and plotted versus time. hpa, hours postadsorption.

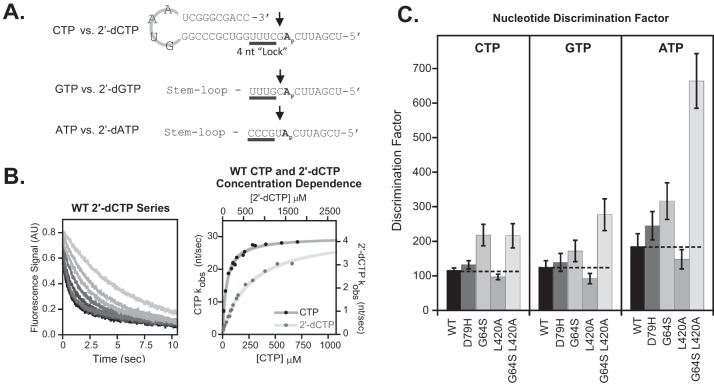

Impact of 3Dpol mutations on viral RNA recombination.

To explore the relationship between viral RNA recombination and error catastrophe, we first examined the impact of 3Dpol mutations on the frequency of viral RNA recombination (Fig. 3). The frequency of viral RNA recombination was measured using murine L929 cells cotransfected with viral RNAs containing lethal mutations in the capsid and 3Dpol genes (Fig. 3A). The ΔCapsid Donor is an RNA replicon with a large in-frame deletion in the capsid genes. When transfected into cells, the ΔCapsid Donor RNA is translated, producing all of the viral proteins needed for viral RNA replication and recombination, including 3Dpol. Furthermore, because the ΔCapsid Donor RNA has all of the cis-active elements needed for viral RNA replication, this viral RNA begins to replicate within cells. Nonetheless, the ΔCapsid Donor RNA is unable to form infectious virus on its own due to the lethal capsid gene deletion. The 3Dpol ΔGDD recipient RNA has a three-amino-acid deletion in the polymerase catalytic domain, preventing the expression of functional 3Dpol. Otherwise, the 3Dpol ΔGDD recipient RNA is intact, containing a full complement of capsid genes and all of the cis-active elements needed for viral RNA replication. When cotransfected into murine cells, nascent RNA products from the ΔCapsid Donor RNA move from one template to another, resuming elongation on the 3Dpol ΔGDD template, leading to the production of recombinant poliovirus (Fig. 3A). Recombinant poliovirus genomes can replicate and form infectious virus within transfected murine cells; however, virus cannot spread from cell to cell because murine cells lack a poliovirus receptor. Infectious virus produced within murine cells was detected by plaque assay in HeLa cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Impact of 3Dpol mutations on viral RNA recombination. (A) Diagram of viral RNA recombination assays. The ΔCapsid “Donor” and ΔGDD “Recipient” RNAs have lethal mutations. When they are cotransfected into murine cells, poliovirus is produced via viral RNA recombination. The titer of virus produced is determined by plaque assays in HeLa cells. (B) Titers of poliovirus produced in cotransfected murine cells. ΔCapsid Donor contained wild-type or mutant polymerases as indicated on the x axis. (C) Replication controls. Titers of poliovirus produced in murine cells transfected with poliovirus RNA containing wild-type or mutant polymerases as indicated on the x axis. **, P values are <0.0001 compared with the wild type.

The impact of 3Dpol mutations on the frequency of viral RNA recombination was determined by engineering 3Dpol mutations into the ΔCapsid Donor RNA (Fig. 3). When the ΔCapsid Donor RNA has a wild-type polymerase, ∼1 × 104 PFU per ml of poliovirus was produced in cotransfected murine cells (Fig. 3B, WT). In contrast, as previously shown (16), an L420A mutation in the ΔCapsid Donor RNA led to substantially less poliovirus (Fig. 3B, L420A). By comparison, mutations other than L420A, i.e., G64S, G64Fix, D79H, and L419A, did not significantly impact the recombination frequency (Fig. 3B). Thus, in our assays, a D79H mutation in 3Dpol had no detectable impact on the frequency of viral RNA recombination, which is inconsistent with the data reported by Xiao et al. (10).

We engineered additional mutations into 3Dpol to further investigate viral RNA recombination and error catastrophe, including a G64Fix codon mutation, a G64Fix codon mutation with L420A, and a G64S L420A double mutant (Fig. 3). The G64S L420A double mutation was engineered to determine how a high-fidelity polymerase mutation (G64S) and a viral RNA recombination disabling mutation (L420A) function together. The L420A mutation inhibited the frequency of viral RNA recombination in both cases (Fig. 3B, G64Fix L420A and G64S L420A). Thus, the L420A 3Dpol mutation inhibited viral RNA recombination in the following three contexts: by itself (L420A), when combined with a G64Fix codon mutation (G64Fix L420A), and when combined with a high-fidelity polymerase mutation (G64S L420A).

Replication controls were performed to determine whether any of the 3Dpol mutations inhibit virus replication in murine cells (Fig. 3C). Poliovirus RNAs encoding either the wild-type or mutant polymerase all produced ∼1 × 106 PFU per ml of poliovirus, showing that the 3Dpol mutations under investigation did not affect the magnitude of poliovirus replication.

Impact of 3Dpol mutations on ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

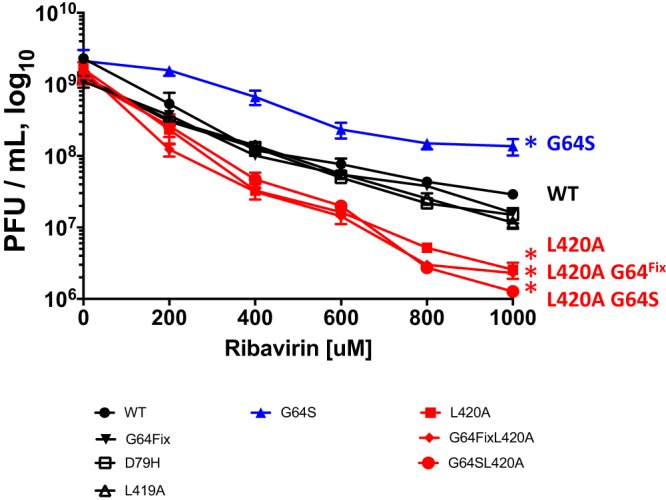

Ribavirin-induced error catastrophe was assayed in poliovirus-infected HeLa cells treated with ribavirin (Fig. 4). The amounts of poliovirus produced within cells decreased as the dose of ribavirin increased from 0 to 1000 μM, consistent with the antiviral mechanism of ribavirin (17). Poliovirus with a wild-type polymerase decreased ∼50-fold from titers ∼109 PFU per ml in the absence of ribavirin to titers of ∼2 × 107 PFU per ml in the presence of 1,000 μM ribavirin (Fig. 4, WT). Poliovirus with a G64S 3Dpol mutation resisted the antiviral activity of ribavirin (Fig. 4, G64S), as previously established (20), and titers decreased ∼10-fold. In contrast, poliovirus with an L420A 3Dpol mutation was substantially more sensitive to inhibition by ribavirin, showing an ∼500-fold decrease in titers (Fig. 4, L420A). Based on these data, we conclude that poliovirus with an L420A mutation is more susceptible than wild-type poliovirus to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

FIG 4.

Impact of 3Dpol mutations on ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. HeLa cells were infected with wild-type or mutant poliovirus at an MOI of 0.1 PFU per cell and incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of ribavirin. Each condition was performed in triplicate. After 3 freeze-thaw cycles, viral titers were determined by plaque assay and plotted versus ribavirin concentration. *, P values are <0.01 compared with the wild type at all concentrations of ribavirin.

Poliovirus with G64Fix, D79H, and L419A 3Dpol mutations exhibited wild-type sensitivity to ribavirin (Fig. 4, WT, G64Fix, D79H, and L419A). Furthermore, it is important to note that adding a high-fidelity G64S mutation to poliovirus with an L420A mutation did not make poliovirus more resistant to ribavirin (Fig. 4, compare WT, G64S, L420A, and G64S L420A; P value was <0.003 for G64S versus G64S L420A at all ribavirin concentrations). Based on these results, we conclude that a G64S mutation can make poliovirus resistant to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe, but only when viral RNA recombination is at near wild-type levels.

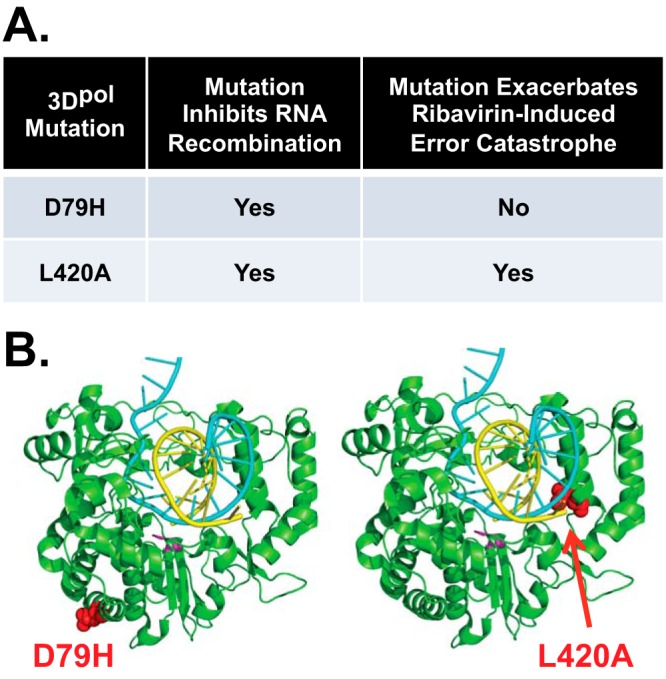

Biochemical characteristics of mutant polymerases.

We examined the biochemical characteristics of purified polymerase to determine the effects of individual mutations on RNA synthesis initiation, elongation complex stability, elongation rates, and fidelity of nucleotide addition, as measured by a discrimination factor reflecting the relative efficiency of rNTP versus 2′-dNTP incorporation (22). By comparison with the wild-type polymerase, the D79H polymerase exhibited wild-type characteristics in all assays (Fig. 5 and Table 1, compare WT and D79H). In contrast, a G64S mutation decreased the processive elongation rate from 22 to 12 nucleotide (nt) per second (Table 1). By slowing the rate of elongation at a precatalytic step of RNA synthesis, the G64S polymerase has more time to discriminate between correct and incorrect nucleotides, leading to an increase in the fidelity of RNA synthesis (23). Accordingly, a G64S polymerase exhibited an increased discrimination factor for both pyrimidines and purines (Fig. 5C). Polymerase with an L420A mutation exhibited slightly slower initiation rates, decreased elongation complex stability, faster elongation rates, and a nucleotide discrimination factor only slightly lower than that of the wild-type polymerase. These data suggest that the faster elongation rates of the L420A polymerase may slightly reduce fidelity, perhaps contributing to increased susceptibility to ribavirin. However, the G64S L420A double mutant exhibited a hybrid biochemical profile with faster elongation rates like the L420A polymerase and a high discrimination factor like the G64S polymerase (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Thus, while L420A polymerase discrimination is slightly reduced compared with that of the wild type, G64S L420A polymerase discrimination is comparable to that of the high-fidelity G64S polymerase (Fig. 5C). From these data, we conclude that the G64S L420A polymerase is a high-fidelity polymerase, like G64S. Notably, the virus containing this high-fidelity G64S L420A polymerase exhibits the high ribavirin sensitivity like virus containing the L420A mutation alone (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data support the conclusion that viral RNA recombination counteracts ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

FIG 5.

Biochemical assays of wild-type and mutant polymerases. (A) RNA hairpin structures used for single nucleotide discrimination assays of CTP, GTP, and ATP. Each hairpin contained an identical stem-loop, shown for the first hairpin only, while four initiation nucleotides (“lock”) and templating bases were varied for each construct. (B) Example 2-aminopurine fluorescence trace and concentration dependence plot from single-nucleotide incorporation stopped-flow assay. The signal change reflects the postcatalysis quenching of 2-aminopurine fluorescence when it is translocated from the +2 pocket into the +1 position in the polymerase active site. (C) NTP versus 2′-dNTP nucleotide discrimination factors for each polymerase, organized by NTP. Dashed lines denote value of wild-type 3Dpol discrimination for each NTP.

TABLE 1.

Biochemical phenotypes of wild-type and mutant polymerasesa

| 3Dpol mutation(s) | RNA initiation (min) | EC stability (min) | Processive elongation (nt/sec) | Processive Km value (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 6 ± 1 | 88 ± 9 | 22 ± 1 | 67 ± 2 |

| D79H | 5 ± 1 | 70 ± 30 | 21 ± 1 | 64 ± 3 |

| G64S | 8 ± 1 | 24 ± 7 | 12 ± 1 | 46 ± 4 |

| L420A | 8 ± 1 | 28 ± 4 | 30 ± 1 | 75 ± 3 |

| G64S and L420A | 6 ± 3 | 40 ± 8 | 26 ± 1 | 84 ± 9 |

Single-nucleotide incorporation and processive elongation were assayed in 75 mM NaCl (pH 7) at 30°C. Values are ± standard errors of parameters from curve fitting. EC, elongation complex.

DISCUSSION

Our data reveal two distinct mechanisms by which picornaviral RDRPs influence error catastrophe, namely, fidelity of RNA synthesis and RNA recombination. A G64S mutation increased viral polymerase fidelity and rendered the virus resistant to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe, but only when RNA recombination was present at wild-type levels. An L420A mutation in the polymerase inhibited RNA recombination and exacerbated ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. Furthermore, the high-fidelity G64S polymerase failed to make virus resistant to ribavirin when RNA recombination was substantially reduced by an L420A mutation. Taken together, these data provide strong evidence to conclude that viral RNA recombination counteracts error catastrophe.

Asexual versus sexual RNA replication mechanisms.

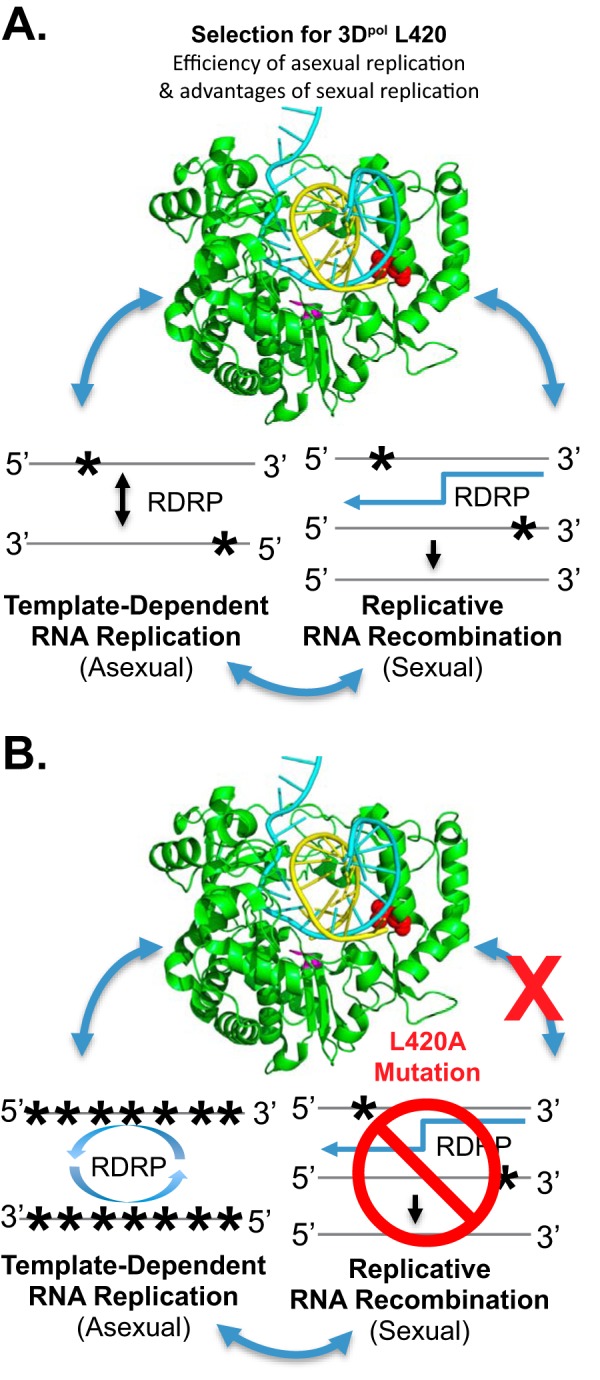

Picornaviruses have asexual and sexual RNA replication mechanisms, both of which are catalyzed by 3Dpol, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Fig. 6A). Template-dependent RNA replication is an efficient form of replication while replicative RNA recombination is used more sparingly to purge mutations from viral RNA. We find that an L420A mutation in 3Dpol reduces viral RNA recombination without inhibiting template-dependent RNA replication. Reiterative cycles of template-dependent RNA replication, in the context of impaired RNA recombination, exacerbates ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (Fig. 4 and 6B).

FIG 6.

Reiterative cycles of template-dependent RNA replication lead to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe when RNA recombination is impaired. (A) 3Dpol is required for both template-dependent RNA replication and replicative RNA recombination. 3Dpol L420 was selected during evolution to mediate replicative RNA recombination. (B) An L420A mutation in 3Dpol disables replicative RNA recombination without impacting template-dependent RNA replication. Reiterative cycles of template-dependent RNA replication, in the context of impaired RNA recombination, lead to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. Mutations in viral RNA indicated with asterisks (*). Poliovirus polymerase PDB entry 4K4T is rendered as in Fig. 1B.

The frequency of viral RNA recombination is controlled in part by the size and shape of membrane-anchored replication complexes that facilitate the colocalization of two or more parental templates (24, 25), and in part by molecular features of 3Dpol. An L420A mutation in 3Dpol reduces RNA recombination-dependent viral titers ∼50-fold without inhibiting template-dependent RNA replication in cells (Fig. 3B and C). It is important to note that an L420A mutation does not completely inhibit viral RNA recombination; residual amounts of replicative RNA recombination remain, and nonreplicative RNA recombination is unaffected by the L420A mutation (16). It is also noteworthy that an L420A mutation failed to render poliovirus susceptible to error catastrophe in the absence of ribavirin (16). Serial genetic bottlenecks can result in error catastrophe (3); however, limiting dilution serial passage of L420A poliovirus in HeLa cells, in the absence of ribavirin, did not lead to an increased accumulation of mutations in poliovirus genomes or to error catastrophe (16). While an L420A mutation does not lead to the extinction of virus populations during limiting dilution serial passage, it does render poliovirus more susceptible to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. This ability to avoid error catastrophe in the absence of ribavirin may be due to residual levels of replicative and nonreplicative RNA recombination or be due to the highly permissive nature of HeLa cells. Error catastrophe is not expected when large virus populations replicate competitively within highly permissive cells.

Asexual template-dependent RNA replication can sustain wild-type magnitudes of virus replication in cells in the absence of mutagenic pressures (Fig. 3C). Wild-type magnitudes of viral RNA recombination, on the other hand, were needed to avoid error catastrophe in the presence of ribavirin (Fig. 4). These data indicate that some viral polymerase features evolved specifically to mediate RNA recombination (5). Based on the protein-RNA interactions found in the structures of 3Dpol-RNA elongation complexes (26, 27), we previously identified poliovirus 3Dpol leucine 420 as an important residue that mediates efficient viral RNA recombination (16). Leu420 is located on a long helix in the polymerase thumb domain that packs into the minor groove of the RNA duplex as it exits the polymerase, and the Leu420 sidechain forms a direct contact with the product-strand ribose that is three bases out from the active site (Fig. 6). Based on these structural insights, we suspect that Leu420 helps to distinguish between homologous and nonhomologous partners in recombination by playing an indirect role in favoring proper Watson-Crick base pairing between template and product strands at the active site. The degree of homology between viral RNA products and partners in recombination ranges from 3 to 30 nucleotides (28). When Leu420 reinforces interactions between homologous partners, three nucleotides from the active site, the polymerase can more efficiently resume elongation and produce recombinant genomes. If the recombination partners are not homologous, then Leu420 will destabilize the binding geometry of the nascent RNA near the active site, reducing or precluding further elongation of the partial genome.

L420A mutation in RDRP disables replicative RNA recombination.

Theory suggests that viral RNA recombination is advantageous because it can en masse purge deleterious mutations that arise during RNA replication (5). The replicative RNA recombination assay that we use requires nascent RNA products to move from one template to another during RNA synthesis to produce infectious virus, as both individual templates have lethal mutations (Fig. 3A). We find that an L420A mutation in the poliovirus polymerase disables RNA recombination ∼50-fold without impacting template-dependent RNA replication (Fig. 3). In contrast, neither G64S nor D79H mutations in the viral polymerase inhibited replicative RNA recombination, contrary to findings reported from other labs (10, 29, 30). Technical differences in the design of recombination assays may be important in this regard. In our recombination assay (16), functional 3Dpol is only expressed from one viral RNA template, the ΔCapsid Donor (Fig. 3A). In contrast, functional 3Dpol is expressed from both RNA templates in the recombination assays from the Evans and Andino labs (10, 29, 30). The expression of functional 3Dpol from both viral RNA templates may confound the recombination assay, increasing the concentrations of the different viral RNAs and allowing for competition between the two replicons, in addition to detecting recombination events. Expressing functional 3Dpol from only one of the recombination partners may alleviate these confounding issues. It is important to note that we have not yet resolved these technical discrepancies and future investigations are required to better understand the basis for quantitative differences in viral RNA recombination associated with D79H and G64S 3Dpol mutations in the two systems.

L420A mutation in RDRP exacerbates ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

One key disadvantage of asexual reproduction is the accumulation of mutations in progeny genomes, which can be detrimental to fitness or viability. Error catastrophe can arise due to repeated genetic bottlenecks (3) or as a consequence of ribavirin’s antiviral effects (4, 17). We used ribavirin to assess the impact of viral RNA recombination on error catastrophe (Fig. 4) and found that the L420A recombination mutation in 3Dpol exacerbated ribavirin-induced error catastrophe. This effect was evident independent of whether a G64S mutation was used to increase the fidelity of RNA synthesis. A G64S mutation increases viral polymerase fidelity and renders an otherwise wild-type virus resistant to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (Fig. 4 and 5; Table 1). However, this was not the case when RNA recombination was disabled by an L420A mutation, showing that viral RNA recombination is required to counteract error catastrophe.

One caveat to these interpretations is the possibility that an L420A polymerase increases the incorporation of ribavirin into viral RNA. This would confound the interpretation that the L420A mutation renders virus susceptible to ribavirin-induced error catastrophe due to its impact on viral RNA recombination. Ribavirin incorporation is expected to increase or decrease coincident with changes in polymerase speed and fidelity (23). Biochemical assays of polymerase nucleotide discrimination partially address this caveat, suggesting that the L420A mutation slightly reduced polymerase fidelity, while polymerase containing both G64S and L420A mutations has a high-fidelity phenotype, like G64S (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Importantly, virus containing the high-fidelity G64S L420A polymerase exhibits increased ribavirin sensitivity like that of virus containing the L420A mutation alone (Fig. 4). These data indicate that a high-fidelity polymerase does not mediate ribavirin resistance when RNA recombination is disabled by an L420A mutation. Biochemical studies of RTP utilization indicate that RTP is a poor substrate for the polymerase, with incorporation rates being 3,000- to 6,000-fold slower than for the cognate ribonucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) (4, 18). We find that ribavirin incorporation into RNA products by purified polymerase is extremely low, precluding (to date) reliable direct comparisons of RTP utilization by wild-type and L420A polymerases. A comprehensive biochemical analysis of the 3Dpol catalytic cycle is ongoing to further explore how the L420A mutation impacts fidelity and ribavirin incorporation. Furthermore, it is possible that mechanisms other than ribavirin-induced error catastrophe (31), such as an inhibition of viral RNA synthesis by ribavirin (32), could influence the replication of viruses containing an L420A polymerase. Future experiments with other mutagens could provide insights in this regard. However, compelling evidence of ribavirin-induced error catastrophe in the literature (4, 17, 18) combined with our experimental data (Fig. 3 to 5) make us conclude that viral RNA recombination is debilitated by an L420A mutation and that viral RNA recombination counteracts ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

3Dpol L420 is conserved across picornavirus species groups.

It is notable that an L420A mutation can disable RNA recombination ∼50-fold (Fig. 3B) without impairing the template-dependent RNA replication that sustains virus replication in cells (Fig. 3C). This suggests that some polymerase features evolved specifically to mediate sexual reproduction, as would be expected (5). There are currently 94 species groups in the Picornaviridae family, and because viral RNA recombination is advantageous, one would expect the viral polymerases across these groups to have evolutionarily conserved features that facilitate recombination. Consistent with this notion, 3Dpol L420 is conserved in sequence and structure across picornavirus species groups (Table 2) (19, 21, 26, 33–37). Based on the sequence and structural conservation, we predict that all picornaviruses have the capacity to use RNA recombination to avoid error catastrophe. Consistent with this, an L421A 3Dpol mutation in EV-A71, analogous to the L420A 3Dpol mutation in poliovirus, inhibits EV-A71 RNA recombination coincident with an increase in sensitivity to ribavirin (38). It is theoretically satisfying that picornaviruses, which evolve into species groups due to frequent RNA recombination in nature (13–15), can avoid error catastrophe via RNA recombination. Viral RNA recombination has the potential to enrich beneficial mutations while purging deleterious mutations (10). Thus, it is not surprising that picornaviral polymerases have conserved elements, including L420, to mediate RNA recombination.

TABLE 2.

Conservation of 3Dpol L420 sequence and structurea

| Species group | Virus | Thumb α-helixb | PDB | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterovirus A | EV-A71 | 410NTQDHVRSLCLLAWHN425 | 4IKA | 33 |

| Enterovirus B | CVB3 | 410NTQDHVRSLCLLAWHN425 | 4K4X | 26 |

| Enterovirus C | Polio | 409NTQDHVRSLCLLAWHN424 | 4K4T | 26 |

| Enterovirus D | EV-D68 | 405NTQDHVRSLCYLAWHN420 | 5XEO | 37 |

| Rhinovirus A | HRV-16 | 408QMQEHVLSLCHLMWHN423 | 4K50 | 26 |

| Rhinovirus B | HRV-14 | 408NTQDHVRSLCMLAWHS423 | 1XR5 | 35 |

| Aphthovirus | FMDV | 419TIQEKLISVAGLAVHS434 | 2E9T | 19 |

| Cardiovirus | EMCV | 411TLSEKLTSITMLAVHS426 | 4NZO | 36 |

Modified from Kempf and Barton (34).

Polio L420, and corresponding residue in other viruses, in bold.

Summary.

Why do RNA viruses recombine (9)? Our data indicate that viral RNA recombination counteracts error catastrophe, substantiating long-held theories regarding the advantages and disadvantages of asexual and sexual RNA replication strategies (2, 5, 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Poliovirus RNAs and cDNA clones.

Poliovirus type 1 (Mahoney) and cDNA clones thereof were used for this study (16, 21, 39, 40). Viral RNAs were produced by T7 transcription of MluI-linearized cDNA clones (Ampliscribe T7 high-yield transcription kit; Cellscript Inc.).

Viral RNA recombination.

L929 cells were cotransfected with a mixture of two viral RNAs, each of which contained a lethal mutation (Fig. 3A, ΔCapsid Donor and 3Dpol ΔGDD Recipient). ΔCapsid Donor is a subgenomic replicon containing an in-frame deletion of VP2 and VP3 capsid gene sequences (Δ nucleotide positions 1175 to 2956) (16, 39). 3Dpol ΔGDD recipient is a full-length poliovirus RNA containing a 9-base deletion in 3Dpol (Δ 6965GGU GAU GAU6973) (16). Deleting three catalytic residues from the viral polymerase (ΔGDD) results in a noninfectious, RNA replication incompetent derivative of poliovirus (Fig. 3, 3Dpol ΔGDD Recipient) (16). Wild-type and mutant derivatives of ΔCapsid Donor RNA were used, with the following 3Dpol substitution mutations: G64S, G64Fix, G64Fix L420A, D79H, L419A, and L420A. Mutations were engineered into ΔCapsid Donor cDNA clones as previously described (16, 21).

L929 cells were plated in 35-mm 6-well dishes ∼24 hours before transfection, with ∼106 cells per well. ΔCapsid Donor and 3Dpol ΔGDD recipient RNAs (1 μg of each) were transfected into each well, in triplicate (i.e., three independent samples for every experimental condition) (TransMessenger transfection reagent; Qiagen). Following transfection, 2 ml of culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg per ml of streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 mM MgCl2) was added to each well and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Virus was harvested at 72 h posttransfection (hpt) and quantified by plaque assay in HeLa cells.

The mean titer from triplicates was plotted with standard deviation (error bars). Statistical significance was determined using the pairwise t test from GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

Replication controls.

L929 cells were transfected with full-length infectious poliovirus RNAs (wild-type and mutant derivatives as noted in Fig. 3C). Wild-type and mutant derivatives of poliovirus RNA were used, with the following 3Dpol substitution mutations: G64S, G64Fix, G64Fix L420A, D79H, L419A, and L420A. Mutations were engineered into infectious cDNA clones as previously described (16, 21).

L929 cells were plated in 35-mm 6-well dishes ∼24 hours before transfection, with ∼106 cells per well. Poliovirus RNA (2 μg) was transfected into each well, in triplicate (i.e., three independent samples for every experimental condition) (Transmessenger transfection reagent; Qiagen). Following transfection, 2 ml of culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg per ml of streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 mM MgCl2) was added to each well and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Virus was harvested at 72 h posttransfection (hpt) and quantified by plaque assay in HeLa cells. The mean titer from triplicates was plotted with standard deviation (error bars).

Wild-type and mutant poliovirus stocks.

Wild-type and mutant derivatives of poliovirus were grown in HeLa cells as previously described (21). Poliovirus stocks with the following 3Dpol genotypes were prepared: wild type, G64S, G64Fix, G64Fix L420A, D79H, L419A, and L420A.

HeLa cells were plated in 35-mm 6-well dishes ∼24 hours before transfection, with ∼106 cells per well. Poliovirus RNA (2 μg) from cDNA clones was transfected into each well (Transmessenger transfection reagent; Qiagen). Following transfection, 2 ml of culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg per ml of streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 mM MgCl2) was added to each well and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. P0 virus was harvested at 72 h posttransfection (hpt), recovered after three rounds of freezing and thawing, cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm, and quantified by plaque assay in HeLa cells. Larger P1 virus stocks were obtained by infecting T150 flasks containing HeLa cell monolayers. Following infections, 20 ml of culture medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg per ml of streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 mM MgCl2) was added to each flask and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 72 h, at which time complete cytopathic effect (CPE) was evident. P1 virus was quantified by plaque assay in HeLa cells. cDNA synthesis and sequencing were used to confirm the stability of 3Dpol mutations in each virus (21).

Ribavirin-induced error catastrophe.

HeLa cells were infected with wild-type or mutant derivatives of poliovirus and incubated in media with escalating concentrations of ribavirin (0 to 1,000 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich), as previously described (10, 17, 18).

HeLa cells were plated in 35-mm 6-well dishes ∼24 h before infection, with ∼106 cells per well. Cells were infected with wild-type and mutant polioviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 PFU per cell. Following 1 hour of virus adsorption, inoculums were removed and cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in 2 ml of medium with or without ribavirin (Sigma-Aldrich). The titers of the viruses were determined by plaque assay.

The mean titer from triplicates was plotted with standard deviation (error bars). Statistical significance was determined using the pairwise t test from GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

3Dpol biochemistry.

Biochemical characteristics of purified 3Dpol were examined as previously described (41, 42). Briefly, initiation experiments were done at room temperature by mixing 5 μM polymerase with 0.5 μM “10 + 1–12 RNA” (41) and 40 μM GTP in reaction buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), and 2 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP). One-microliter samples were removed from the reaction at various times and quenched with 19 μl of quench buffer consisting of 50 mM EDTA, 400 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), and 2 mM TCEP. The amount of +1 product formed as a function of time was determined by gel electrophoresis and mathematically fit to a single exponential equation to obtain an initiation time constant. Elongation complex stability was determined by allowing the initiation reaction to proceed for 15 minutes and then diluting 10 μl of the reaction into 90 μl of high-salt buffer (300 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES [pH 6.5], and 2 mM TCEP) to prevent further RNA binding. The amounts of elongation-competent complexes remaining at various time points up to 4 hours were assayed by mixing 5-μl aliquots of this diluted sample with 80 μM final concentrations of ATP, GTP, and UTP and allowing elongation to take place for 2 minutes before the addition of 10 μl quench buffer and 10 μl gel loading dye. Samples were separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis in 20% polyacrylamide 19:1, 7 M urea, and 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE). RNA was labeled with an IRdye 800RS N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester (LI-COR Biosciences) and detected using a LI-COR Odyssey 9120 infrared imager system.

Kinetic assays were performed using stopped-flow methods to assess processive elongation with a fluorescein 5′-end-labeled RNA (43) and single-nucleotide incorporation and rNTP-vs-2′-dNTP discrimination with an internally 2-aminopurine-labeled RNA (44). For these experiments, stalled polymerase-RNA elongation complexes were formed at room temperature for 15 minutes with 15 μM polymerase, 10 μM RNA, 50 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), 2 mM TCEP, and 60 μM each of ATP and GTP. Samples were then diluted 200-fold to a final RNA concentration of 50 nM in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7), 75 mM NaCl, and 4 mM MgCl2. Elongation reactions were done using a Bio-Logic SFM-4000 titrating stopped-flow instrument with an MOS-500 spectrometer at 30°C. MgCl2 was always present at 4 mM excess over the total NTP concentration, and NTP mixes in the processive elongation experiments contained equal concentrations of all four nucleotides.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI059130 to O.B.P. and AI042189 to D.J.B.).

We thank Russell Riley (University of Colorado RNA Bioscience Initiative intern) for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Domingo E, Holland JJ. 1997. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol 51:151–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake JW, Holland JJ. 1999. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:13910–13913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duarte E, Clarke D, Moya A, Domingo E, Holland J. 1992. Rapid fitness losses in mammalian RNA virus clones due to Muller’s ratchet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:6015–6019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graci JD, Cameron CE. 2002. Quasispecies, error catastrophe, and the antiviral activity of ribavirin. Virology 298:175–180. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao L. 1997. Evolution of sex and the molecular clock in RNA viruses. Gene 205:301–308. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkegaard K, Baltimore D. 1986. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell 47:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagy PD, Simon AE. 1997. New insights into the mechanisms of RNA recombination. Virology 235:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barton NH, Charlesworth B. 1998. Why sex and recombination? Science 281:1986–1990. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon-Loriere E, Holmes EC. 2011. Why do RNA viruses recombine? Nat Rev Microbiol 9:617–626. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Y, Rouzine IM, Bianco S, Acevedo A, Goldstein EF, Farkov M, Brodsky L, Andino R. 2016. RNA recombination enhances adaptability and is required for virus spread and virulence. Cell Host Microbe 19:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koonin EV, Wolf YI, Nagasaki K, Dolja VV. 2008. The Big Bang of picorna-like virus evolution antedates the radiation of eukaryotic supergroups. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:925–939. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi M, Lin XD, Chen X, Tian JH, Chen LJ, Li K, Wang W, Eden JS, Shen JJ, Liu L, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. 2018. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature 556:197–202. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown B, Oberste MS, Maher K, Pallansch MA. 2003. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid coding region. J Virol 77:8973–8984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8973-8984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberste MS, Maher K, Pallansch MA. 2004. Evidence for frequent recombination within species human enterovirus B based on complete genomic sequences of all thirty-seven serotypes. J Virol 78:855–867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.855-867.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmonds P. 2006. Recombination and selection in the evolution of picornaviruses and other Mammalian positive-stranded RNA viruses. J Virol 80:11124–11140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01076-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempf BJ, Peersen OB, Barton DJ. 2016. Poliovirus polymerase Leu420 facilitates RNA recombination and ribavirin resistance. J Virol 90:8410–8421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00078-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty S, Cameron CE, Andino R. 2001. RNA virus error catastrophe: direct molecular test by using ribavirin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:6895–6900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111085598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crotty S, Maag D, Arnold JJ, Zhong W, Lau JY, Hong Z, Andino R, Cameron CE. 2000. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat Med 6:1375–1379. doi: 10.1038/82191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrer-Orta C, Arias A, Pérez-Luque R, Escarmís C, Domingo E, Verdaguer N. 2007. Sequential structures provide insights into the fidelity of RNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:9463–9468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700518104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeiffer JK, Kirkegaard K. 2003. A single mutation in poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confers resistance to mutagenic nucleotide analogs via increased fidelity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:7289–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232294100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kempf BJ, Kelly MM, Springer CL, Peersen OB, Barton DJ. 2013. Structural features of a picornavirus polymerase involved in the polyadenylation of viral RNA. J Virol 87:5629–5644. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02590-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campagnola G, McDonald S, Beaucourt S, Vignuzzi M, Peersen OB. 2015. Structure-function relationships underlying the replication fidelity of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. J Virol 89:275–286. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01574-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold JJ, Vignuzzi M, Stone JK, Andino R, Cameron CE. 2005. Remote site control of an active site fidelity checkpoint in a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 280:25706–25716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503444200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger D, Bienz K. 2002. Recombination of poliovirus RNA proceeds in mixed replication complexes originating from distinct replication start sites. J Virol 76:10960–10971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10960-10971.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Ruiz H, Diaz A, Ahlquist P. 2018. Intermolecular RNA recombination occurs at different frequencies in alternate forms of brome mosaic virus RNA replication compartments. Viruses 10:131. doi: 10.3390/v10030131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong P, Kortus MG, Nix JC, Davis RE, Peersen OB. 2013. Structures of coxsackievirus, rhinovirus, and poliovirus polymerase elongation complexes solved by engineering RNA mediated crystal contacts. PLoS One 8:e60272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong P, Peersen OB. 2010. Structural basis for active site closure by the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:22505–22510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007626107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korotkova E, Laassri M, Zagorodnyaya T, Petrovskaya S, Rodionova E, Cherkasova E, Gmyl A, Ivanova OE, Eremeeva TP, Lipskaya GY, Agol VI, Chumakov K. 2017. Pressure for pattern-specific intertypic recombination between Sabin polioviruses: evolutionary implications. Viruses 9:E353. doi: 10.3390/v9110353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowry K, Woodman A, Cook J, Evans DJ. 2014. Recombination in enteroviruses is a biphasic replicative process involving the generation of greater-than genome length “imprecise” intermediates. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004191. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodman A, Arnold JJ, Cameron CE, Evans DJ. 2016. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the role of the viral polymerase in enterovirus recombination. Nucleic Acids Res 44:6883–6895. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graci JD, Cameron CE. 2006. Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses. Rev Med Virol 16:37–48. doi: 10.1002/rmv.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vo NV, Young KC, Lai MM. 2003. Mutagenic and inhibitory effects of ribavirin on hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 42:10462–10471. doi: 10.1021/bi0344681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Wang Y, Shan C, Sun Y, Xu P, Zhou H, Yang C, Shi PY, Rao Z, Zhang B, Lou Z. 2013. Crystal structure of enterovirus 71 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complexed with its protein primer VPg: implication for a trans mechanism of VPg uridylylation. J Virol 87:5755–5768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02733-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempf BJ, Barton DJ. 2015. Picornavirus RNA polyadenylation by 3D(pol), the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virus Res 206:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Love RA, Maegley KA, Yu X, Ferre RA, Lingardo LK, Diehl W, Parge HE, Dragovich PS, Fuhrman SA. 2004. The crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from human rhinovirus: a dual function target for common cold antiviral therapy. Structure 12:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vives-Adrian L, Lujan C, Oliva B, van der Linden L, Selisko B, Coutard B, Canard B, van Kuppeveld FJ, Ferrer-Orta C, Verdaguer N. 2014. The crystal structure of a cardiovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase reveals an unusual conformation of the polymerase active site. J Virol 88:5595–5607. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03502-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C, Wang C, Li Q, Wang Z, Xie W. 2017. Crystal structure and thermostability characterization of Enterovirus D68 3D(pol). J Virol 91:e00876-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00876-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodman A, Lee KM, Janissen R, Gong YN, Dekker NH, Shih SR, Cameron CE. 2019. Predicting intraserotypic recombination in Enterovirus 71. J Virol 93:e02057-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02057-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collis PS, O'Donnell BJ, Barton DJ, Rogers JA, Flanegan JB. 1992. Replication of poliovirus RNA and subgenomic RNA transcripts in transfected cells. J Virol 66:6480–6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steil BP, Kempf BJ, Barton DJ. 2010. Poly(A) at the 3′ end of positive-strand RNA and VPg-linked poly(U) at the 5′ end of negative-strand RNA are reciprocal templates during replication of poliovirus RNA. J Virol 84:2843–2858. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02620-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hobdey SE, Kempf BJ, Steil BP, Barton DJ, Peersen OB. 2010. Poliovirus polymerase residue 5 plays a critical role in elongation complex stability. J Virol 84:8072–8084. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02147-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kortus MG, Kempf BJ, Haworth KG, Barton DJ, Peersen OB. 2012. A template RNA entry channel in the fingers domain of the poliovirus polymerase. J Mol Biol 417:263–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong P, Campagnola G, Peersen OB. 2009. A quantitative stopped-flow fluorescence assay for measuring polymerase elongation rates. Anal Biochem 391:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald S, Block A, Beaucourt S, Moratorio G, Vignuzzi M, Peersen OB. 2016. Design of a genetically stable high fidelity Coxsackievirus B3 polymerase that attenuates virus growth in vivo. J Biol Chem 291:13999–14011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.726596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]