Abstract

The DNA tetrahedron (Td), as one of the novel DNA-based nanoscale biomaterials, has been extensively studied because of its excellent biocompatibility and increased possibilities for decorating precisely. Although the use of Td in laboratories is well established, knowledge surrounding the factors influencing its preparation and storage is lacking. In this research, we investigated the role of the magnesium ions, which greatly affect the structure and stability of DNA. We assembled 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 μM Td in buffers containing different Mg2+ concentrations, demonstrating that 2 and 5 mM Mg2+ is optimal in these conditions, and that yields decrease dramatically once the DNA concentration reaches 20 μM or the Mg2+ concentration is lower than 0.5 mM. We also verified that the Td structure is retained better through freeze-thawing than lyophilization. Furthermore, a lower initial Mg2+ (≤2 mM) benefited the maintenance of Td structure in the process of lyophilization. Hence, our research sheds light on the influence of Mg2+ in the process of preparing and storing Td, and also provides some enlightenment on improving yields of other DNA nanostructures.

Keywords: DNA tetrahedron, self-assembly, biomaterials, nanoparticles, magnesium ions, lyophilization

1. Introduction

Recently, the DNA nanostructure has attracted a lot of attention because of its special properties, such as flexible size and shape, excellent biocompatibility, and increased possibilities for decorating precisely. Stabilized by strong hydrogen bonds, the DNA nanostructure can easily self-assemble into designed shapes, leading to its wide application in diagnosis, imaging or drug delivery [1]. Among these nanoparticles, the DNA tetrahedron (Td), which has a high yield and rigid structure, is widely used [2]. It has been reported that a Td can be internalized by a cell even without transfection reagent [3], based on which scientists have designed various smart systems to deliver CpG motifs [4], siRNA [5] or small molecular drugs [6], and to detect mRNA in living cells [7]. However, there are still many problems that need to be explored for the further development of the Td, including factors influencing a Td’s assembly process and its stability during storage.

Previously published data showed that the types and concentrations of cations in the solution are the key factors affecting the stability of the DNA structure. Compared with monovalent cations, divalent cations, such as Mg2+, have stronger interactions with DNA and a greater influence on DNA structure [8]. There are two types of interactions between DNA and Mg2+: electrostatic force (phosphate groups) and chemical bonds (like hydrogen bonds and coordinate bonds) [9]. In a solvent, Mg2+ has a coordination shell with six water molecules that can bind to the O6 of the DNA to form hydrogen bonds. Also, in some cases, coordinate water molecules are replaced by the N7 and O6 sites of the DNA guanine, forming coordination bonds between the DNA and Mg2+. The effects of magnesium can be considered as ‘protective effects’ of DNA, not only decreasing the intramolecular repulsion in DNA but also making the DNA duplex more rigid [10]. Importantly, it has been confirmed that the quantity of magnesium ions affects DNA structure. DNA is stabilized in the B conformation when Mg2+ is at a modest concentration, but when the concentration is extremely high, the DNA structure exhibits a more compact form [11].

Therefore, the influence of Mg2+ on DNA nanostructure in applicable conditions has been studied. It was reported that a low concentration of Mg2+ (≤1 mM) is detrimental to the stability of DNA nanostructures [12]. However, Keller’s group proposed that high Mg2+ concentrations are not necessary for maintaining stability if an optimal buffer is chosen based on the specific form of the DNA nanostructure [13]. Furthermore, there are other ways to ensure DNA nanostructure integrity against the impacts of Mg2+, such as oligolysine-coated protection [14]. However, the role of Mg2+ in DNA nanostructure preparation and storage (such as freezing-thawing and lyophilization) has not yet been investigated; such studies are important for improving experimental reproducibility or reducing batch variations through the preparation of one batch of Td used in multiple rounds of experiments for a longtime.

In this study, we synthesized Td at different Mg2+ concentrations and clarified the influence of Mg2+ on Td preparation and storage, which provides some enlightenment toward improving yields of other DNA nanostructures.

2. Results

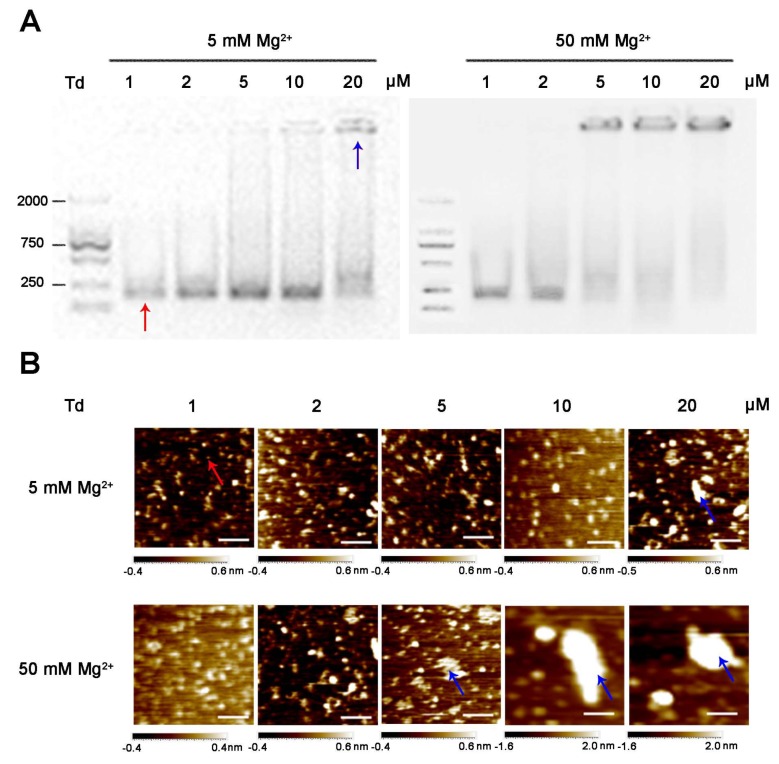

Most previous studies ([4], [15], [16], and [17]) reported that a Td could be constructed in a Tris-Mg buffer (TM buffer) with 5 or 50 mM Mg2+; therefore, we first assembled the Td at varied concentrations (1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μM) in the common TM buffers containing 5 or 50 mM Mg2+. The sequences of the DNA strands are presented in Table S1. The yields and morphologies of the tetrahedrons were identified by electrophoresis and atomic force microscope (AFM), respectively. The results show that in the buffer containing 5 mM Mg2+, Td was successfully assembled at all concentrations except for 20 μM. The band of the 20 μM DNA sample was stagnant in the well of gel, indicating the aggregation of DNA strands under this condition; these results correspond with the images observed by AFM (Figure 1). Nevertheless, under the condition of 50 mM Mg2+, the Td could only be formed in the first two DNA concentrations (1 and 2 μM), while the samples with the other concentrations (5, 10 and 20 μM) exhibited diameters that were much larger than normal (Figure 1). These results indicate that the concentrations of Mg2+ had an influence on the self-assembly process of the Td and that high Mg2+ concentrations may be detrimental to the formation of high-concentration Td.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of tetrahedrons (Tds) (1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 μM) prepared in 5 and 50 mM Mg2+. (A) Agarose gel of DNA products. (B) AFM images of DNA products. Scale bars: 100 nm. Red and blue arrows represent successfully assembled Td and aggregated DNA, respectively.

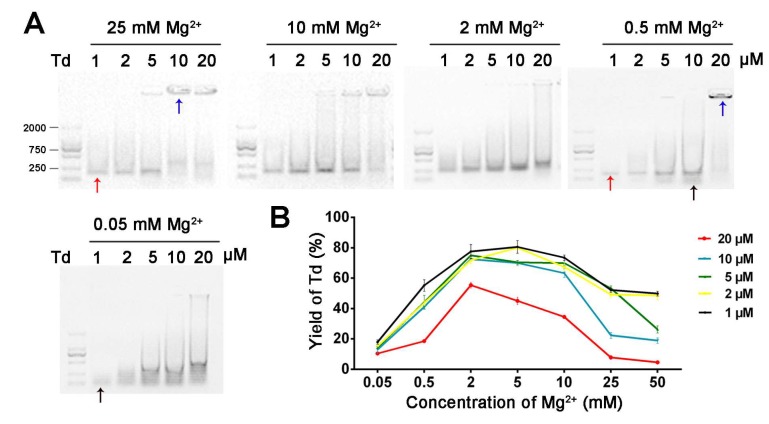

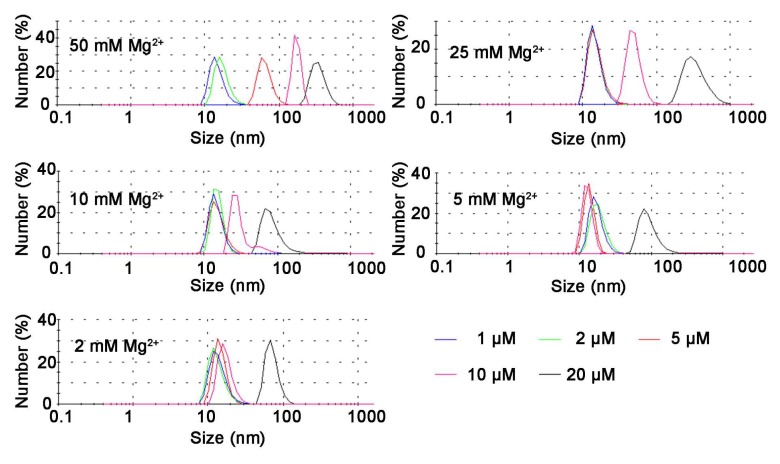

Next, we further clarified the role of Mg2+ in the self-assembly process of Td by synthesizing Td in TM buffers containing diverse Mg2+ concentrations (0.05, 0.5, 2, 10 and 25 mM MgCl2). The electrophoresis results (Figure 2A) show that different concentrations of Td were assembled in 2 mM MgCl2. However, 1, 2 or 5 μM Td could be assembled in 25 mM Mg2+, and aggregation appeared when the concentration of DNA increased to 10 or 20 μM. Nevertheless, the samples of 10 or 20 μM prepared in lower Mg2+ density (0.5 and 0.05 mM) also showed poor yields, and bands with faster mobility were observed in the electrophoresis results, indicating the existence of free DNA strands. The dynamic light scattering (DLS) results further confirm that the successfully prepared Td had a hydrodynamic size of ~12.36 nm, and when aggregation occurred, the particle sizes increased with an increase of Mg2+ concentration (Figure 3). The polydispersity index (PDI) values of products are listed in Table S2, indicating that greater particle heterogeneity as aggregation occurred. (Only particles larger than 3 nm can be measured in this apparatus; therefore, the DLS results of the Td prepared in 0.05 or 0.5 mM Mg2+ were not available.)

Figure 2.

The influence of Mg2+ and Td concentrations on preparing Td in micromolar ranges. (A) Agarose gel of 1, 2, 5, 10 or 20 μM DNA products under various Mg2+ concentrations. (B) Yield curve of Td versus Mg2+ and Td concentrations. Red, blue and black arrows represent successfully assembled Td, aggregated DNA and free DNA strands, respectively.

Figure 3.

The hydrate sizes of Td (1, 2, 5, 10, 20 μM) prepared in different Mg2+ concentrations, analyzed by DLS.

After estimating the yields of Td in various environments by gray scanning (Table S3 and Figure 2B), we found that adequate Mg2+ intensity is the first condition for constructing high-yielding Td; this observation was based on the fact that yields decreased dramatically to less than 20% in 0.05 mM Mg2+, no matter what concentration of DNA nanostructures was prepared. Notably, DNA in higher concentrations is more vulnerable to the change in Mg2+ density. As illustrated in Table S3, when the concentration of Mg2+ changed from 2 mM to 25 mM, the yield of 20 μM Td slumped from 55.4% to 7.8%, while that of the 1 μM sample decreased from 77.53% to 52.22% (Table S3).

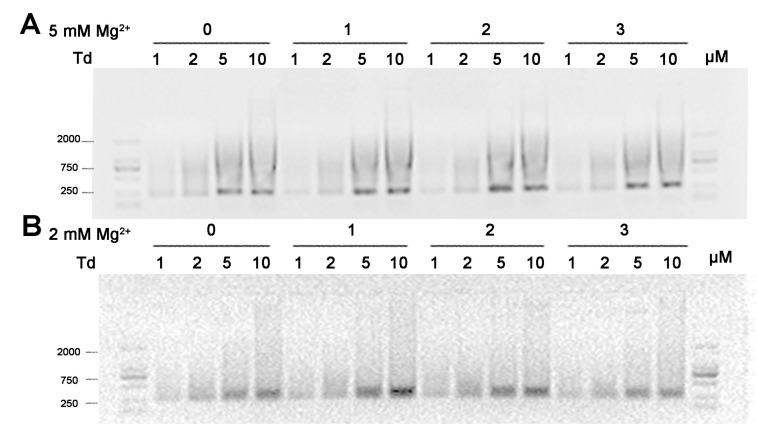

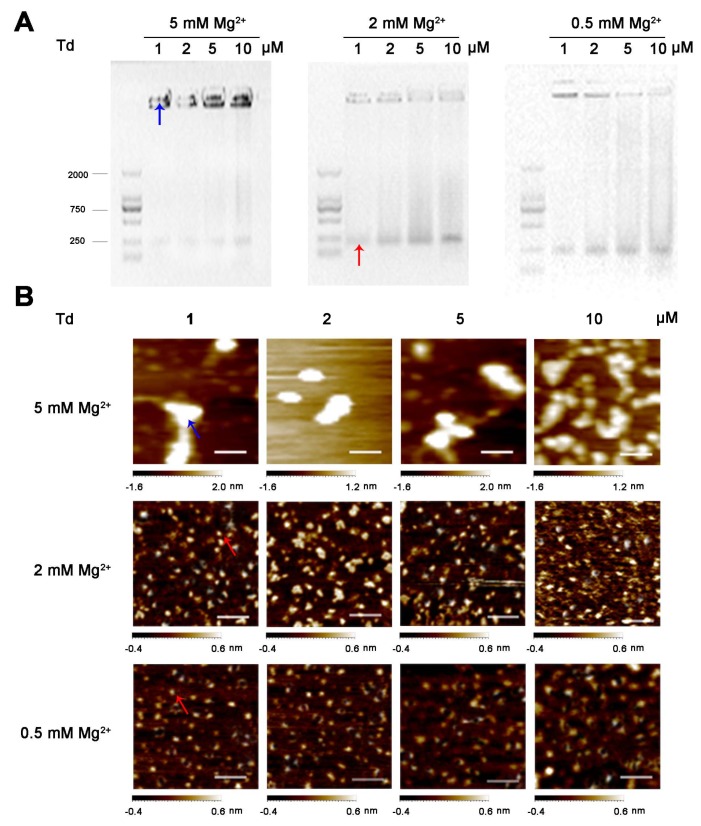

As for the Td storage, we examined the effect of Mg2+ during low-temperature freezing and vacuum drying. In this part, we firstly prepared Td in TM buffer containing 5 or 2 mM Mg2+, and then carried out either the process of freeze-thawing three times or the process of lyophilization treatment. As a result, after freeze-thawing treatment, irrespectively of time, the bands of Td prepared under both 5 and 2 mM Mg2+ conditions had an identical mobile speed, and the gels showed no difference to that of freshly prepared ones (Figure 4). These results indicate that iterative freeze-thawing processing had no influence on the structure of the Td. However, when dissolving the freeze-dried powder of the tetrahedrons in an equivalent volume of deionized water, the tetrahedrons prepared in 5 mM Mg2+ mostly stayed in wells and formed disordered aggregations, as observed on the AFM images. Differently, tetrahedrons at all concentrations prepared in 2 mM Mg2+ mostly maintained their previous structures (Figure 5). These results indicate that the stability of the Td structure was more sensitive to the process of vacuum drying than to that of low-temperature freezing. To further verify the influence of Mg2+ in the process of lyophilization, we decreased its concentration to 0.5 mM during preparation, repeated the experiment, and found that the Td after the freeze-drying in this condition produced little aggregation (Figure 5). All these data imply that lower Mg2+ in the initial prepared buffer benefits the structure stability of the Td in the process of lyophilization.

Figure 4.

The influence of the freezing-thawing step on the stability of Td structure. Agarose gel of 1, 2, 5 or 10 μM Td prepared in buffers containing either 5 mM (A) or 2 mM (B) Mg2+, after repeated freeze-thawing processes. Numbers on the top line indicate the times of freeze-thawing.

Figure 5.

The influence of the lyophilization process on the stability of the Td structure. (A) Agarose gel and (B) AFM images of re-dissolved freeze-drying powders of 1, 2, 5 or 10 μM Td, prepared in buffers containing 5, 2 or 0.5 mM Mg2+. Scale bars: 100 nm. Red and blue arrows represented Td and aggregated DNA, respectively.

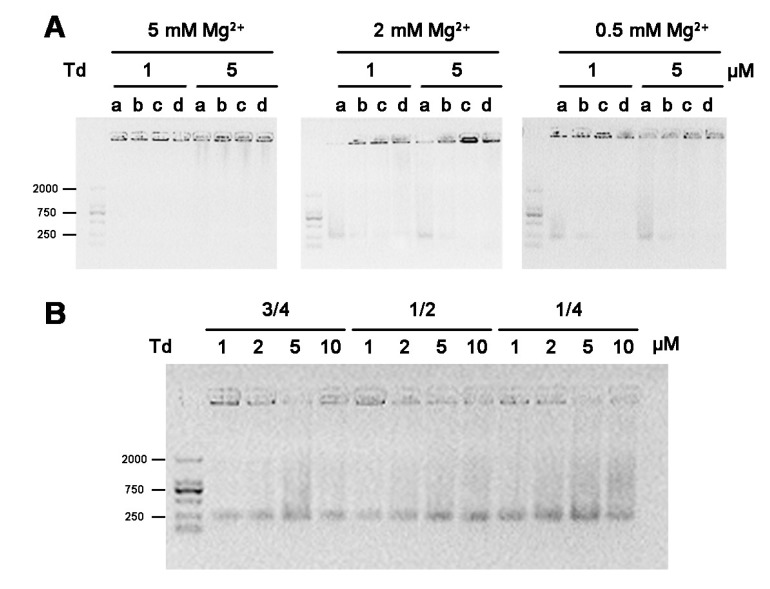

Because PBS, Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) and Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) are commonly-used biological buffers for cellular or bacterial culture, we investigated whether lyophilizated powder of Td could be directly dissolved in these buffers. In this study, freeze-dried powders of 1 or 5 μM Td, prepared in TM buffer containing 5, 2, or 0.5 mM Mg2+, were dissolved in different solutions. We found that aggregation was more pronounced in the samples dissolved in PBS, MHB and DMEM than the sample dissolved in water (Figure 6A). The results indicate that any solvent containing more complex components than water resulted in the aggregation of Td powder after re-dissolving. Furthermore, we investigated the feasibility of concentrating Td (prepared in 2 mM Mg2+) by dissolving its freeze-dried powder in different volumes of deionized water, which were 3/4, 1/2 or 1/4 of the initial volume of prepared buffer. As demonstrated by the electrophoresis results (Figure 6B), the Td powders were successfully re-dissolved and mostly retained their original structures at the above volumes, indicating that it is a practicable way to concentrate Td prepared in an appropriate Mg2+ intensity (2 mM Mg2+).

Figure 6.

The influence of re-dissolving solvents and volumes on the stability of Td structure after freeze-drying. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the re-dissolved 1 and 5 μM Td solutions, which were prepared in buffer containing 5, 2, or 0.5 mM Mg2+. “a, b, c, d” represent different re-dissolving solvents: H2O, PBS, MHB and DMEM, respectively. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 1, 2, 5 or 10 μM Td re-dissolved in water, the volume of which was 3/4, 1/2 or 1/4 of the initial prepared buffer.

3. Discussion

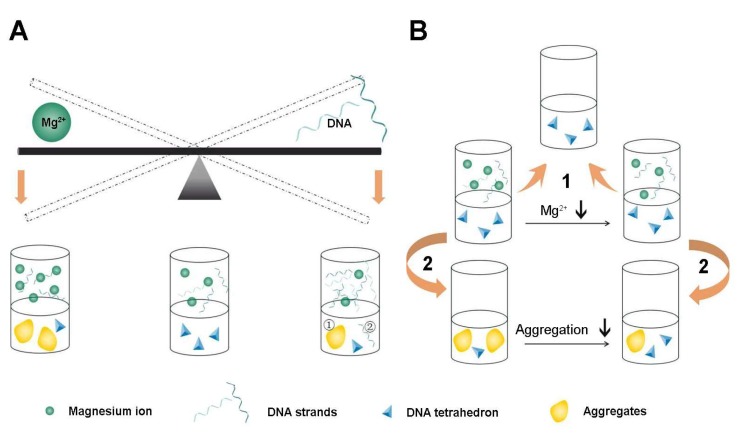

These results imply that Mg2+ concentration plays an important role when synthesizing Td, and that relatively low concentrations of Mg2+ are more helpful in producing Td with a high concentration; however, the formation will not succeed without enough Mg2+. In addition, the yield declined visibly when the Td concentration increased to 20 μM (Figure 7A). The exact quantitative balance of DNA and Mg2+ and the underling mechanism are still unclear. It would be meaningful to research the exact interaction between DNA and Mg2+ in the process of assembling tetrahedrons, which will guide further studies to meet the requirements of diverse DNA nanostructures. Furthermore, we found that vacuum drying exerts a more conspicuous effect on the Td structure than freeze-thawing. Notably, the Mg2+ concentration during Td preparation has a great influence on this process (Figure 7B). In addition, considering the complexity of the lyophilization process and for avoiding the interference of other components, water as a re-dissolving solution is the best choice. It has been reported that high Mg2+ can cause condensation between DNA double helixes by ion-bridging, and this process varies according to different kinds of DNA configuration [18], which may explain our observed results that more Mg2+ tends to result in unexpected aggregation during the preparation and lyophilization. When preparing the Td, the unexpected entanglement between DNA strands is more likely to occur due to high DNA concentration, which may lead to DNA aggregation. However, the prepared Td remains its structure during lyophilization only if the Mg2+ concentration in the prepared buffer is appropriate because hydrogen bonds in the Td are beneficial for maintaining the structure. As for the influence of the buffer when re-dissolving the freeze-dried powder, we speculate that the bond angle is distorted due to the special structure of Td, which is highly vulnerable to complicated elements in PBS, MHB or DMEM when dissolved. Importantly, our results suggest that freeze-dried dissolving is a practicable way to concentrate Td if it is prepared in initial solutions with less than 2 mM Mg2+. Nevertheless, the reaction mechanism during this process is not clear. It would be valuable to further study the relationship between Mg2+ and DNA and to seek the conformations of the crystal structure of the Td during the process.

Figure 7.

Illustrative diagram demonstrating the influence of different concentrations of Mg2+ and DNA on the processes of preparation, freezing-thawing and lyophilization of Td. (A) The balance between concentrations of Mg2+ and DNA strands when preparing Td. There is an appropriate range of Mg2+ concentrations for the successful assembly of Td. A higher concentration of Mg2+ (>10 mM) results in an apparent aggregation of the DNA, while a lower concentration of Mg2+ (<2 mM) leads to an insufficient assembly of Td. Similarly, if the concentration of DNA reaches the upper limit (20 μM), pronounced aggregation also makes the assembly fail. Therefore, successful self-assembly of the Td can only be achieved by maintaining the balance of the two ingredients. (B) Freeze-thawing has no influence on the structure of the formed Td (1), but lyophilization increases the risks of Td aggregation, which would be largely attenuated by reducing the concentration of Mg2+ in the initial prepared buffer (2).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

All the oligonucleotides were obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The 2000 bp DNA marker was bought from Takara (Tokyo, Japan). Magnesium chloride hexahydrate was purchased from Tian Li (Tianjin, China). Trizma base was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Agarose was bought from Lonza (Rockland, ME, USA). PBS, Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) and DMEM were purchased from Boster (Wuhan, China), Land Bridge (Beijing, China) and Life technologies (Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. The water used in all experiments was prepared via a Millipore Milli-Q purification system with a resistivity higher than 18 MΩ cm-1.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Preparation of DNA Tetrahedron

Four DNA strands in equal molar quantities were mixed in TM buffer (12.5 mM Tris, 0.05/0.5/2/5/10/25/50 mM MgCl2, pH = 7.8-8.0), heated to 95 °C for 5 min with MJ MiniTM 48-Well Personal Thermal Cycler, and then rapidly cooled on ice for at least 1 h.

4.2.2. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

One percent (w/v) agarose gel was prepared by adding EtBr. An amount of 5 μL prepared DNA tetrahedron mixed with a loading buffer was loaded and run at 95 V for 35 min in an ice bath.

4.2.3. AFM Imaging

All samples were diluted to 2.5 nM in TM buffer. An amount of 10 μL DNA tetrahedron was dropped onto a freshly cleaved mica and incubated for 5 min to achieve strong absorption onto the surface. Then, the mica was rinsed with filtered deionized water and dried gently with compressed nitrogen. After that, the samples were scanned in the tapping mode on the Agilent 5500 SPM.

4.2.4. Freeze-thawing of DNA Tetrahedron

The DNA tetrahedron was frozen to −80 °C for 12 h and thawed at room temperature, repeatedly. The samples were collected immediately after every circle of freeze-thawing.

4.2.5. Lyophilization of DNA Tetrahedron

The tubes containing DNA tetrahedron were sealed with holey sealing films, and frozen to −80 °C for 2 h. Then, the samples were placed into a FD5-3 Freezer Dryer, which had been cooled to −50 °C ahead of time and maintained a vacuum until the nanoparticles transformed into powder.

4.2.6. Estimation of Td Yield

Using the software ImageJ, the band intensity of Td was compared with the total intensity of the corresponding lane. This ratio was determined as the Td yield, which was obtained from three independent experiments.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we took Td as an example, investigating the role of Mg2+ concentration in Td preparation and storage. Firstly, we assembled the Td in buffers containing different Mg2+ concentrations and we found that 2 or 5 mM Mg2+ to be the optimal condition, and that at higher or lower levels the yields of Td will reduce. Furthermore, we also verified the viability of maintaining the structure of Td by the process of freeze-thawing rather than lyophilization, and confirmed that the concentration of Mg2+ was important for the structural stability of Td during lyophilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Qun Li from State Key Laboratory of Military Stomatology for technological support of AFM.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The sequences of DNA tetrahedrons; Table S2. The polydispersity index (PDI) of DNA particles prepared in different conditions determined by DLS (Data were meanSD, n = 3); Table S3. Yields of DNA tetrahedrons under different conditions (%). (Data were meanSD, n = 3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H., X.L. and X.X.; methodology, Y.H. and Z.C; software, Z.C. and Z.H.; formal analysis, B.M., X.M. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. and X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X. and X.L.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502143, 81673477 and 81471997) and foundation of fourth military medical university (2018JSTS05).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: All the samples are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lee D.S., Qian H., Tay C.Y., Leong D.T. Cellular processing and destinies of artificial DNA nanostructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:4199–4225. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00700C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Y., Chen Z., Zhang H., Li M., Hou Z., Luo X., Xue X. Development of DNA tetrahedron-based drug delivery system. Drug Deliv. 2017;24:1295–1301. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1373166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh A.S., Yin H., Erben C.M., Wood M.J., Turberfield A.J. DNA cage delivery to mammalian cells. Acs Nano. 2011;5:5427–5432. doi: 10.1021/nn2005574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J., Pei H., Zhu B., Liang L., Wei M., He Y., Chen N., Li D., Huang Q., Fan C. Self-assembled multivalent DNA nanostructures for noninvasive intracellular delivery of immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides. Acs Nano. 2011;5:8783–8789. doi: 10.1021/nn202774x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H., Lytton-Jean A.K., Chen Y., Love K.T., Park A.I., Karagiannis E.D., Sehgal A., Querbes W., Zurenko C.S., Jayaraman M., et al. Molecularly self-assembled nucleic acid nanoparticles for targeted in vivo siRNA delivery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim K.R., Kim D.R., Lee T., Yhee J.Y., Kim B.S., Kwon I.C., Ahn D.R. Drug delivery by a self-assembled DNA tetrahedron for overcoming drug resistance in breast cancer cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2013;49:2010–2012. doi: 10.1039/c3cc38693g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie N., Huang J., Yang X., Yang Y., Quan K., Wang H., Ying L., Ou M., Wang K. A DNA tetrahedron-based molecular beacon for tumor-related mRNA detection in living cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2016;52:2346–2349. doi: 10.1039/C5CC09980C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W., Nordenskiold L., Mu Y. Sequence-specific Mg2+-DNA interactions: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chemistry. B. 2011;115:14713–14720. doi: 10.1021/jp2052568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anastassopoulou J., Theophanides T. Magnesium-DNA interactions and the possible relation of magnesium to carcinogenesis. Irradiation and free radicals. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2002;42:79–91. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee S., Bhattacharyya D. Influence of divalent magnesium ion on DNA: Molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2013;31:896–912. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.713780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serec K., Babic S.D., Podgornik R., Tomic S. Effect of magnesium ions on the structure of DNA thin films: An infrared spectroscopy study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:8456–8464. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn J., Wickham S.F., Shih W.M., Perrault S.D. Addressing the instability of DNA nanostructures in tissue culture. Acs Nano. 2014;8:8765–8775. doi: 10.1021/nn503513p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kielar C., Xin Y., Shen B., Kostiainen M.A., Grundmeier G., Linko V., Keller A. On the stability of DNA origami nanostructures in low-magnesium buffers. Angew. Chem. 2018;57:9470–9474. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponnuswamy N., Bastings M.M.C., Nathwani B., Ryu J.H., Chou L.Y.T., Vinther M., Li W.A., Anastassacos F.M., Mooney D.J., Shih W.M. Oligolysine-based coating protects DNA nanostructures from low-salt denaturation and nuclease degradation. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Q.M., Zhu M.J., Zhang T.T., Xu J.J., Chen H.Y. A novel DNA tetrahedron-hairpin probe for in situ “off-on” fluorescence imaging of intracellular telomerase activity. Analyst. 2016;141:2474–2480. doi: 10.1039/C6AN00241B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keum J.W., Ahn J.H., Bermudez H. Design, Assembly, and Activity of Antisense DNA Nanostructures. Small. 2011;7:3529–3535. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun P.C., Zhang N., Tang Y.F., Yang Y.N., Chu X., Zhao Y.X. SL2B aptamer and folic acid dual-targeting DNA nanostructures for synergic biological effect with chemotherapy to combat colorectal cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017;12:2657–2672. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S132929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z.L., Wu Y.Y., Xi K., Sang J.P., Tan Z.J. Divalent Ion-Mediated DNA-DNA Interactions: A Comparative Study of Triplex and Duplex. Biophys. J. 2017;113:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.