Abstract

The sucrose non-fermentation-related protein kinase (SnRK) is a kind of Ser/Thr protein kinase, which plays a crucial role in plant stress response by phosphorylating the target protein to regulate the interconnection of various signaling pathways. However, little is known about the SnRK family in Eucalyptus grandis. Thirty-four putative SnRK sequences were identified in E. grandis and divided into three subgroups (SnRK1, SnRK2 and SnRK3) based on phylogenetic analysis and the type of domain. Chromosome localization showed that SnRK family members are unevenly distributed in the remaining 10 chromosomes, with the notable exception of chromosome 11. Gene structure analysis reveal that 10 of the 24 SnRK3 genes contained no introns. Moreover, conserved motif analyses showed that SnRK sequences belonged to the same subgroup that contained the same motif type of motif. The Ka/Ks ratio of 17 paralogues suggested that the EgrSnRK gene family underwent a purifying selection. The upstream region of EgrSnRK genes enriched with different type and numbers of cis-elements indicated that EgrSnRK genes are likely to play a role in the response to diverse stresses. Quantitative real-time PCR showed that the majority of the SnRK genes were induced by salt treatment. Genome-wide analyses and expression pattern analyses provided further understanding on the function of the SnRK family in the stress response to different environmental salt concentrations.

Keywords: Eucalyptus grandis, SnRK family, bioinformatics analysis, salt stress, Cis-elements

1. Introduction

Plants are confronted with various environmental insults in nature, such as drought, salt, low temperature and pathogen attack. Under these situations, plants are capable of initiating their own defense mechanism to adapt to various potentially stressful damaging challenges. The process of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins represents very important mechanisms for plants to respond to environmental stress signals [1]. Protein kinase is an important regulator in plants, which senses environmental signals through membrane receptor proteins and activates different protein phosphorylation pathways, which regulate the expression of downstream stress-resistant genes, and protect plants or reduce harm to those plants from an adverse external environment [2]. In recent years, various studies have reported on protein kinase genes that are related to resistance, namely the receptor protein kinase (RLK) [3], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [4], calcium dependent protein kinase (CDPK) [5], and sucrose nonfermenting1 (SNF1) kinase families [6].

SnRK is a Ser/Thr protein kinase, which widely exists in plants, including SnRK1, SnRK2 and SnRK3 subfamilies [6,7]. SnRK1 is homologous to yeast and mammals and has a highly conserved terminal catalytic domain, which plays an important role in regulating carbon metabolism and energy status [8]. The SnRK2 and SnRK3 subfamilies are unique to plants, both of which have additional members and are more diverse than their SnRK1 subfamily counterparts. In addition to a highly conserved kinase domain at the N-terminus, SnRK2s also contains a variable adjusting conserved domain at the C-terminus [9]. SnRK3 can bind to calcineurin B-like (CBL) protein to participate in the Ca2+-mediated stress response, and is referred to as the calcineurin B-like protein-interacting protein kinases (CIPK). The N-terminal of CIPK has a conserved kinase domain and the C-terminal has two conserved domains: NAF and PPI [10,11].

The SnRK1 subfamily is primarily involved in metabolic regulation and affects plant development. In addition, the SnRK1 gene has been isolated from many plants [7]. The SnRK1 gene family is a relatively small subfamily. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the SnRK1 gene family contains AtSnRK1.1, AtSnRK1.2 and AtSnRK1.3 [12]. In transgenic barley, expression of antisense SnRK1 protein kinase affects pollen development, resulting in infertility [13]. Furthermore, a decrease of SnRK1 in pea activity by 50 - 70 percent will lead to the increased of sucrose accumulation and the defective of seed maturation [14]. In addition, SnRK1 is similar to yeast SNF-1, which is involved in carbon metabolism [8]. Substantial evidence suggests that SnRK1 is involved in the regulation of various physiological and biochemical processes in plants, and it has been shown to connect stress and metabolism [15].

SnRK2 plays an important role in the ABA signal transduction pathway, osmotic stress and sugar metabolism. In A. thaliana, eight out of ten SnRK2 genes can be induced by hyperosmotic and salt stress, and five are activated by ABA [16]. Specifically, the stomatal closure and ABA mediated gene expression in the process of AtSnRK2.6 involved in ABA regulation [17,18]. Furthermore, an overexpression of AtSnRK2.8 shows higher resistance to drought [19]. At present, this subfamily has been extensively studied in different plants, such as rice [20], corn [21], soybean [22], cotton [23], Brachypodium distachyon [24], and Hevea brasiliensis [25]. All SnRK2 members are induced by one or more abiotic stresses, especially salt and osmotic stress, and includes overexpression of SAPK and NtSnRK2.1 enhanced salt tolerance of transgenic plants [26,27]. PtSnRK2.5 and PtSnRK2.7 positively regulate plant responses to salt stress [28]. The overexpression of TaSnRK2.3, TaSnRK2.4, TaSnRK2.7 and TaSnRK2.8 in A. thaliana was reported to enhance plants tolerance to salt and other stresses [29,30]. Recent studies have shown that TaSnRK2.9 improved salt and drought stress tolerance through detoxification of (reactive oxygen species) ROS [30]. Additionally, overexpression of GhCIPK6 significantly increased the tolerance of transgenic A.thaliana to salt, drought and ABA stress [31]. The ZmSnRK2.8 has a positive regulating effect on the salt stress signal transduction pathway, while the ZmSnRK2.11 is a possible negative regulator in response to the salt and drought stress signal transduction pathways [32]. These findings suggest that members of the SnRK2 subfamily play an important role in salt and other abiotic stresses.

The SnRK3 subfamily also responds to abiotic stress. For example, OsCIPK31 was sensitive to salt and other stressful conditions during germination and seedling growth in rice [33]. A. thaliana CIPK6 was involved in growth and development. Furthermore, atcipk6 reduces auxin transport and tolerance to salt stress [34]. Overexpression of SICIPK24 (SISOS2) enhanced salt tolerance in the tomato [35]. The expression of AtCIPK3 increased the tolerance of A.thaliana to various stress stimuli, including high salt concentrations, wounds, drought, etc. [36]. In addition, AtCIPK21 regulates osmotic and salt stress responses [37]. Further, SnRK3s can interact with CBL, and the CBL-CIPKs complex is a complicated calcium-signaling system that performs a vital function in resistance to various stresses in plants [6,38]. One of the most famous mechanisms of the SOS (salt overly sensitive) system is provided by SOS2/AtCIPK24 (salt overly sensitive 2), which is a member of the SnRK3 subfamily in A.thaliana. As Na+/H+ antiporter, it improves plant salt tolerance by maintaining ionic homeostasis [39,40]. The overexpression of PtSOS2 enhances salt tolerance by mediating osmotic protection and inducing the protective antioxidant enzyme system [41]. Collectively, the above-mentioned studies demonstrated that CIPKs play important roles in the physiological response to salt tolerance in different plants.

Although the SnRK gene family plays an important role in the abiotic stress response, and the ABA signaling pathway and development, there is still a sustained lack of research on understanding the functional import of the SnRK gene in Eucalyptus grandis. E. grandis has tremendous economic, ecological and social value. As an excellent timber forest, it provides a large number of raw materials for both the paper industry and timber industry. Today, it occupies a huge cultivation area. With the rapid development of molecular biology and the publication of the E. grandis genome [42], it is possible for us to analyze the SnKR gene family at the genome-wide level. In this study, the SnRK gene family was systematically studied in E. grandis using bioinformatics. A total of 34 SnRK genes were identified. In addition, their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, protein motifs, chromosomal location and promoter were analyzed. Further, the expression patterns of the SnRK gene family in different tissues were calculated while the differential expression of the SnRK gene was executed under different salt concentrations and salt treatment duration by qRT-PCR. These results will lay the foundation for further study of the molecular mechanisms that account for salt tolerance and molecular breeding in E. grandis.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of SnRK Genes in E. grandis

A total of 34 candidate genes were identified in the E. grandis genome. Based on the subfamily and their physical location (from top to bottom) on the chromosome, EgrSnRK genes were named EgrSnRK1.1~EgrSnRK1.2, EgrSnRK2.1~EgrSnRK2.8, and EgrSnRK3.1~EgrSnRK3.24. The parameters of the gene characteristics including the open reading frame (ORF) length, chromosome location, exons, protein molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) were analyzed and are shown in Table 1. They encode proteins that range from 334 to 550 amino acids (aa) in size, with an average of 427 aa, with a molecular weight that varies from 38.07 kDa (EgrSnRK2.2) to 61.62 kDa (EgrSnRK3.11). Moreover, the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) ranged from 4.73 to 9.52; however, the isoelectric points of the SnRK2 subfamily were distributed from 4.73 to 6.18, and these belong to acidic proteins. The predicted subcellular localization data (Table S1) showed that 82.4 percent of the EgrSnRK genes were predicted to be expressed in the nucleus and cytoskeleton, followed by 73.5 percent in the chloroplast. Additionally, gene expression of only EgrSnRK3.9, EgrSnRK3.11 and EgrSnRK3.14 genes was predicted in peroxisomes. Relevant details are shown in Table S1.

Table 1.

List of SnRK genes that are identified in Eucalyptus grandis.

| Name | Gene Identifier | Chr | Location Coordinates (5’–3’) | ORF Length (bp) | Protein | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (a.a.) | PI | Mol.Wt. (kDa) | Exons | |||||

| EgrSnRK1.1 | Eucgr.B00544.1 | 2 | 5601699–5607791 | 1509 | 502 | 8.6 | 57.22 | 10 |

| EgrSnRK1.2 | Eucgr.J01364.3 | 10 | 15761839–15770736 | 1548 | 515 | 8.51 | 59.06 | 10 |

| EgrSnRK2.1 | Eucgr.D02135.1 | 4 | 34783964–34788536 | 1014 | 337 | 6.18 | 38.09 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.2 | Eucgr.E00345.1 | 5 | 3283351–3287110 | 1005 | 334 | 5.63 | 38.07 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.3 | Eucgr.G00557.1 | 7 | 8288459–8292881 | 1089 | 362 | 5.31 | 41.25 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.4 | Eucgr.G00558.1 | 7 | 8300485–8309815 | 1071 | 356 | 6 | 40.66 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.5 | Eucgr.H04745.1 | 8 | 66440405–66443914 | 1023 | 340 | 5.36 | 38.47 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.6 | Eucgr.I00977.1 | 9 | 20388568–20394557 | 1092 | 363 | 4.73 | 41.19 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.7 | Eucgr.I01180.1 | 9 | 22740915–22744636 | 1092 | 363 | 4.87 | 41.44 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK2.8 | Eucgr.I02742.1 | 9 | 38306416–38310220 | 1122 | 373 | 6.18 | 42.90 | 9 |

| EgrSnRK3.1 | Eucgr.A00690.1 | 1 | 14305972–14307407 | 1374 | 457 | 8.51 | 51.41 | 2 |

| EgrSnRK3.2 | Eucgr.A00691.1 | 1 | 14298350–14300413 | 1320 | 439 | 9.06 | 49.90 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.3 | Eucgr.A00711.1 | 1 | 14006453–14008352 | 1344 | 447 | 5.52 | 49.76 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.4 | Eucgr.A00734.1 | 1 | 13706777–13708090 | 1077 | 358 | 9.52 | 40.60 | 6 |

| EgrSnRK3.5 | Eucgr.A00737.1 | 1 | 13619140–13620568 | 1149 | 382 | 5.92 | 43.19 | 5 |

| EgrSnRK3.6 | Eucgr.B03773.1 | 2 | 57202252–57207754 | 1323 | 440 | 6.66 | 49.91 | 14 |

| EgrSnRK3.7 | Eucgr.B03958.1 | 2 | 5872963–58735460 | 1320 | 439 | 8.15 | 49.29 | 12 |

| EgrSnRK3.8 | Eucgr.B04021.1 | 2 | 59343262–59345126 | 1200 | 399 | 7 | 45.36 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.9 | Eucgr.C00193.1 | 3 | 1473208–1476720 | 1407 | 468 | 6 | 52.51 | 15 |

| EgrSnRK3.10 | Eucgr.C00357.1 | 3 | 5833911–5835857 | 1200 | 399 | 8.81 | 44.92 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.11 | Eucgr.C01333.1 | 3 | 20087289–20093442 | 1656 | 550 | 9.17 | 61.62 | 15 |

| EgrSnRK3.12 | Eucgr.C01944.1 | 3 | 33758197–33760724 | 1392 | 463 | 7.97 | 52.37 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.13 | Eucgr.C02590.1 | 3 | 51530920–51532898 | 1302 | 433 | 9.05 | 48.55 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.14 | Eucgr.C04226.1 | 3 | 79695224–79704623 | 1338 | 445 | 9.1 | 50.09 | 14 |

| EgrSnRK3.15 | Eucgr.D00272.1 | 4 | 4577009–4583478 | 1410 | 469 | 8.94 | 52.69 | 14 |

| EgrSnRK3.16 | Eucgr.D00481.1 | 4 | 8897498–8900910 | 1461 | 486 | 8.46 | 53.90 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.17 | Eucgr.E00017.1 | 5 | 222650–235591 | 1335 | 444 | 8.65 | 50.85 | 13 |

| EgrSnRK3.18 | Eucgr.E02758.1 | 5 | 48871914–48873537 | 1248 | 415 | 8.68 | 46.78 | 2 |

| EgrSnRK3.19 | Eucgr.F00453.1 | 6 | 4226550–4232934 | 1368 | 455 | 6.48 | 51.46 | 14 |

| EgrSnRK3.20 | Eucgr.H00223.1 | 8 | 6265751–6267413 | 1419 | 472 | 9.26 | 50.70 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.21 | Eucgr.H03182.1 | 8 | 45402293–45404868 | 1341 | 446 | 8.59 | 49.24 | 2 |

| EgrSnRK3.22 | Eucgr.J00641.1 | 10 | 7028075–7034476 | 1377 | 458 | 6.5 | 52.77 | 14 |

| EgrSnRK3.23 | Eucgr.J01840.1 | 10 | 23702496–23704068 | 1338 | 445 | 9.39 | 50.84 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.24 | Eucgr.J03116.1 | 10 | 36664597–36666371 | 1347 | 448 | 8.72 | 50.34 | 1 |

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree of SnRK Genes

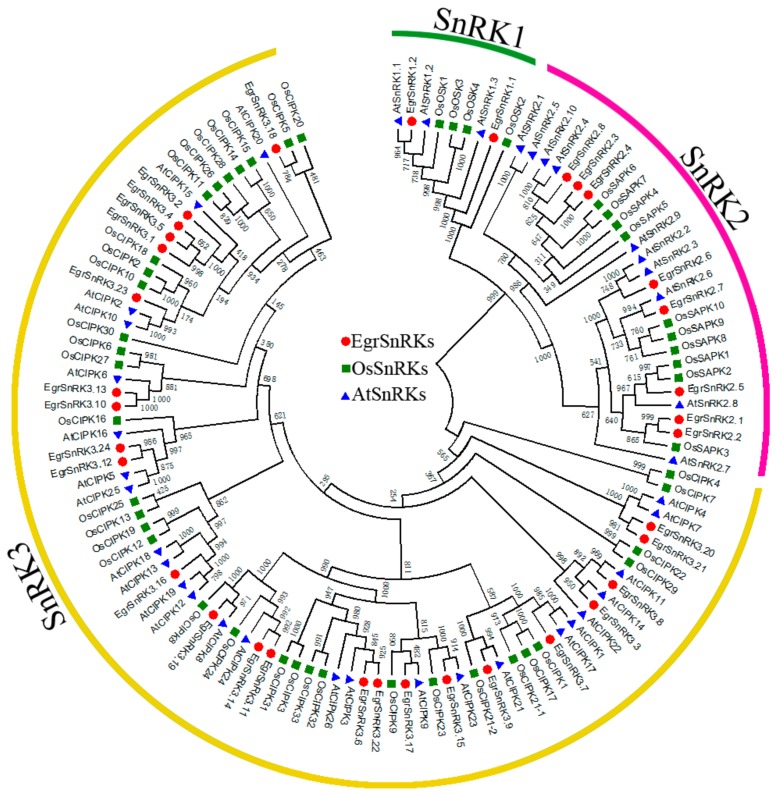

For the purpose of researching the evolutionary relationships of SnRK genes in A. thaliana, rice, grape, poplar and E. grandis, a phylogenetic tree was built with 34, 39, 48, 30 and 45 SnRK protein sequences, respectively, which was constructed using MEGA 7.0 by employing the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) methods with 1000 bootstrap replicates (Figure S1). The accession numbers or locus IDs of the SnRK genes are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2. The phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1) indicated that the SnRK genes could be divided into three groups in combination with an analysis of the Ser/Thr Kinase domain by Pfam, NCBI and SMART. The SnRK3 subfamily has the largest number of members, while the SnRK1 subfamily has the fewest members and includes two to four genes. In addition, the SnRK2 subfamily has eight members. The SnRK genes of each group were evenly distributed, but it was found that the clustering distribution of SnRK genes in rice was obvious, which might be due to the fact that rice is a monocotyledonous plant and the other species are dicotyledonous plants.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of SnRK genes from Eucalyptus grandis, Arabidopsis, and rice. Thirty-four EgrSnRK genes, 39 AtSnRK genes, and 48 OsSnRK genes are clustered into three subgroups (SnRK1, SnRK2 and SnRK3). The SnRK genes from E. grandis, A. thaliana, and rice are denoted by red, blue, and green, respectively. Details of the SnRK genes from all three plant species are listed in Table S2. The tree was generated using Clustal X 2.0 software using the neighbor-joining (N-J) method.

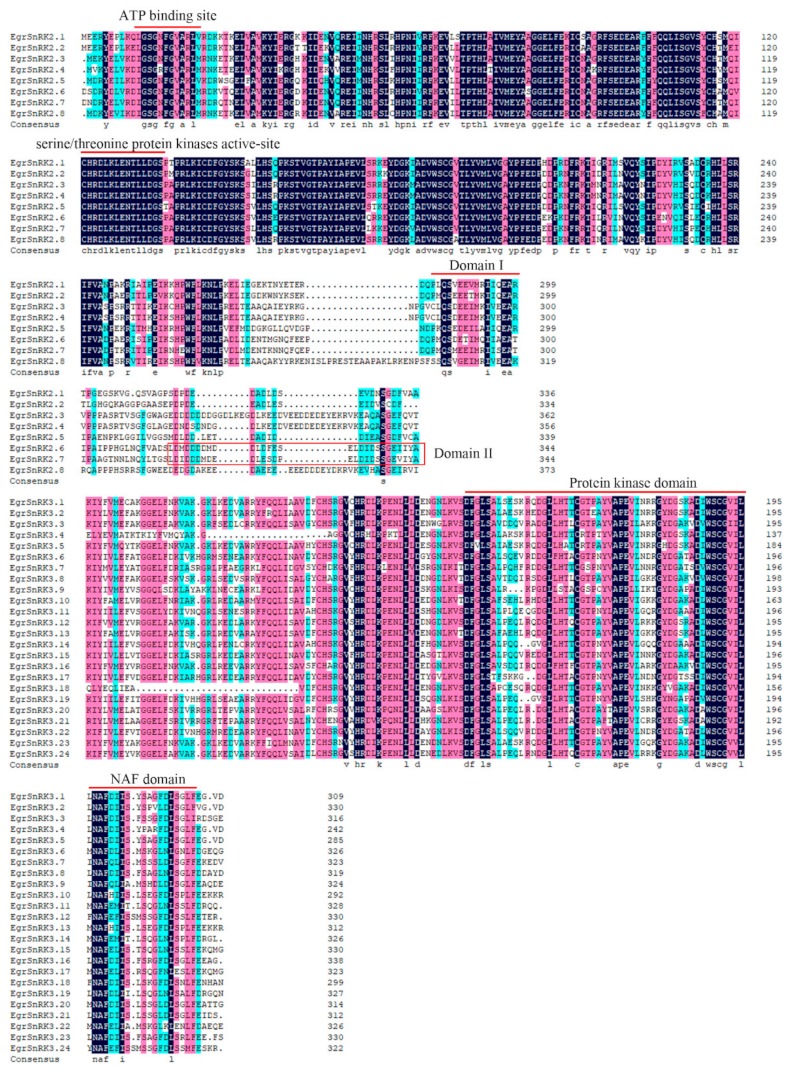

2.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment of the SnRK Gene Family

In order to further explore the structural features of the EgrSnRK family, multiple sequence alignment was performed with 32 amino acid sequences by DNAMAN 8. Results showed that all SnRKs genes could be divided into three subfamilies, in which the EgrSnRK2 subfamily included highly conserved domains at the N- and C terminals, which had divergent domains (Figure 2). All the members of the EgrSnRK2 subfamily had an ATP binding site and the serine/threonine protein kinase active-site in the kinase domains of their N-terminal regions. Moreover, there are two different domains at the C-terminal, of which domain I was necessary for osmotic stress-mediated activation and exists in all members of the EgrSnRK2 subfamily. Domain II was only present in strongly ABA-responsive kinases. Domain II was also observed only in EgrSnRK2.6 and EgrSnRK2.7. Similarly, the SnRK3 subfamily had a protein kinase domain at the N-terminal, while a NAF region was observed at the C-terminal. NAF domains played an important role in interacting with CBLs.

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of SnRK genes in E. grandis. Sequences were aligned using DNAMAN 8 software.

2.4. Motif Composition and Gene Structural Analysis of the SnRK Gene Family in E. grandis

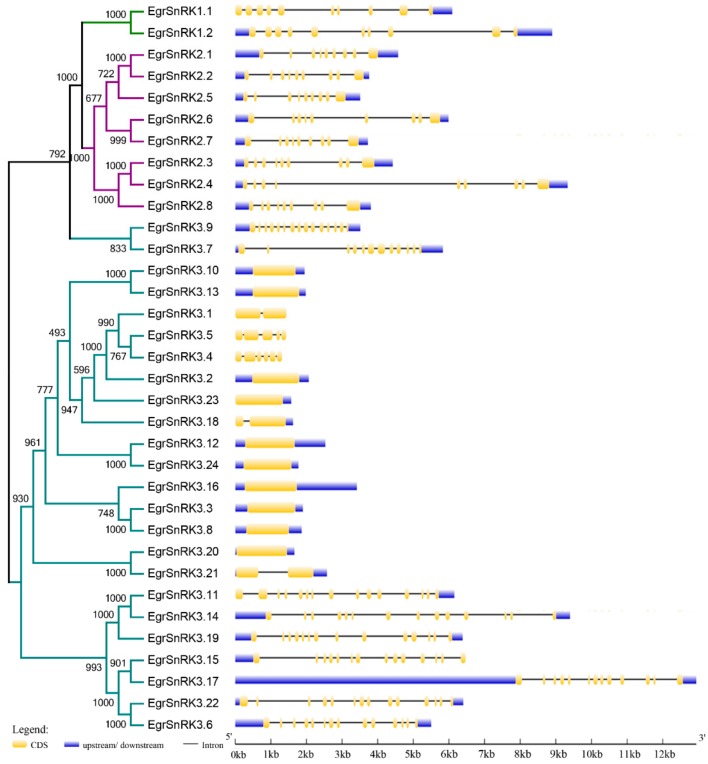

To reveal the intron/exon structure of EgrSnRK family genes, we combined the online Gene Structure Display Server and phylogenetic tree for subsequent analysis (Figure 3). The result showed that members of the same subfamily were similar. The SnRK1 subfamily (EgrSnRK1.1 and EgrSnRK1.2) have 10 exons, and all SnRK2 genes have nine exons, which was similar to cotton, Hevea brasiliensis and Malus prunifolia [25,43]. However, the number of exons present in the SnRK3 subfamily showed obvious differences, which varied from 1 to 15. Furthermore, there were five genes that contained one exon and one gene contained two exons, the remainder of the 18 SnRK3 genes contained multiple extrons ranging from 5 to 15.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships and gene structures of SnRK genes in E. grandis. Left panel shown the phylogenetic tree of EgrSnRK that was constructed by the neighbor-joining method. The SnRK1, SnRK2 and SnRK3 subfamily are marked by different colors. Right panel shown the gene structure of EgrSnRK genes. Exons are indicated by yellow rectangles. Gray lines connecting two exons represent introns.

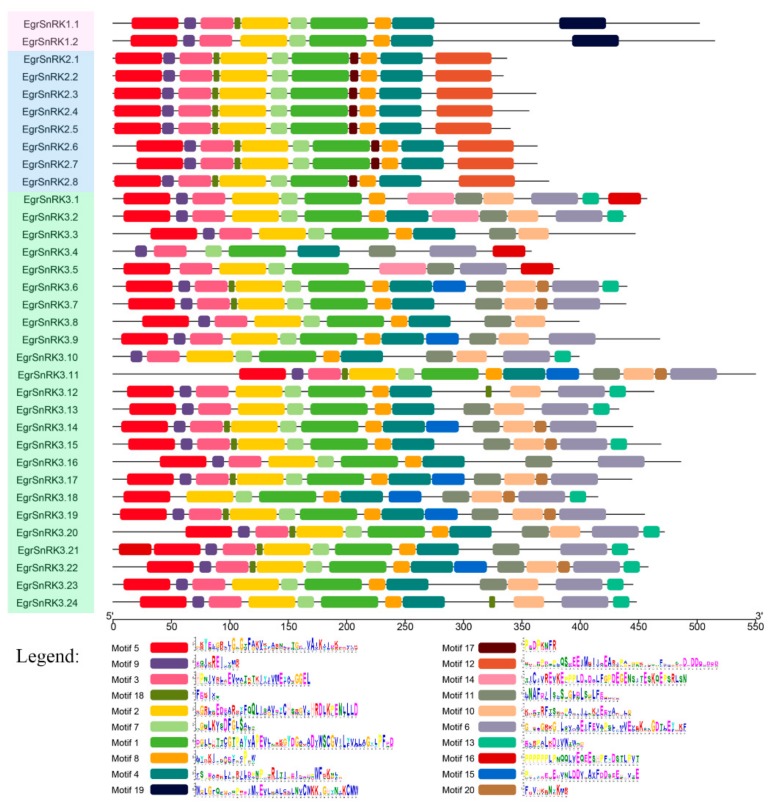

The sequence of the EgrSnRK protein was further analyzed using MEME. Twenty different conserved motifs were acquired from MEME and sequence and length information of the conserved motif are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Each of the putative motifs obtained from MEME was annotated by searching Pfam. Motif 1 and motif 2 encoded a protein kinase domain, while motif 10 and motif 11 encode a NAF domain. As for the other motifs, these do not have a functional annotation. It was interesting to note that all EgrSnRK genes included the same conserved motifs (motif 1/2/3/4/5/7/9/14; Figure 4). Meanwhile, we found that the SnRK1 and SnRK2 subfamily share a common type and position of the conserved motif. Besides, Motif 19 is specific to the SnRK1 subfamily, while Motif 12 and 17 only appear in the SnRK2 subfamily and other motifs were found in the SnRK3 subfamily.

Figure 4.

Conserved motifs of SnRK genes in E. grandis. Distribution of the 20 conserved motifs in the EgrSnRK genes following MEME analysis. The differentially colored boxes represent different motifs and their position in each sequence of EgrSnRKs.

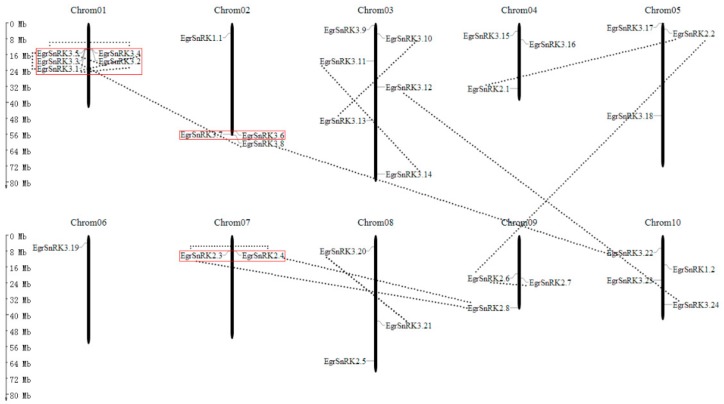

2.5. Chromosomal Location and Gene Pairs Analysis in E. grandis

A chromosome localization map was constructed with the location information of EgrSnRK genes. The results showed that 34 EgrSnRK genes were distributed unevenly on 10 chromosomes (Figure 5), and chromosome 11 contained no genes that belonged to the SnRK family. Moreover, only one EgrSnRK (EgrSnRK3.19) gene was distributed on chromosome 6, while the most SnRK genes (6 genes) were distributed on chromosome 1. We found that the SnRK3 subfamily genes were mainly distributed on chromosome 1, 2, 3 and 10. In addition, clusters are formed on chromosomes 1, 2 and 7. Besides, one gene cluster, namely EgrSnRK3.1/EgrSnRK3.2/EgrSnRK3.3/EgrSnRK 3.4/EgrSnRK3.5, appeared to have evolved from tandem duplication events, which EgrSnRK3.1/EgrSnRK3.2 and EgrSnRK 3.4/EgrSnRK3.5 by tandem duplication (box in Figure 5) according to previous studies [42]. Due to the different types and functions of genes, the rate of evolution varies. Thus, to explore the role of selection pressure in SnRK gene family evolution, Ks values, Ka values, and Ka/Ks ratios of paralogues and orthologues were obtained and from this we built a sliding-window analysis for paralogues genes. Details of paralogues and orthologues are listed in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4. In fact, a Ka/Ks = 1 represents neutral selection, a Ka/Ks>1 shows positive selection and a Ka/Ks>1 is indicative of purifying selection. The Ka/Ks ratio of 17 paralogous gene pairs was less than 1, with the exception of the EgrSnRK3.1/EgrSnRK3.4 (1.035). The result suggested that the EgrSnRK gene family underwent purifying selection.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal location of EgrSnRK genes. The 34 EgrSnRK genes are widely mapped to 10 of the 11 chromosomes. The paralogous pairs of EgrSnRK genes are connected by gray-dotted lines. The red boxes in front of the genes on behalf of these genes belonging to a gene cluster.

Table 2.

Ka/Ks ratios of paralogous genes.

| Paralogues | Ka (JC) | Ks (JC) | Ka/Ks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene 1 | Gene 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK2.2 | EgrSnRK2.1 | 0.0992 | 1.3197 | 0.075 |

| EgrSnRK2.6 | 0.23388 | 1.64249 | 0.142 | |

| EgrSnRK2.3 | EgrSnRK2.4 | 0.03228 | 0.09785 | 0.33 |

| EgrSnRK2.8 | 0.17009 | 1.24632 | 0.136 | |

| EgrSnRK2.4 | EgrSnRK2.8 | 0.13842 | 1.32215 | 0.105 |

| EgrSnRK2.6 | EgrSnRK2.7 | 0.11743 | 2.19481 | 0.054 |

| EgrSnRK3.1 | EgrSnRK3.2 | 0.11413 | 0.14826 | 0.77 |

| EgrSnRK3.4 | 0.54087 | 0.52272 | 1.035 | |

| EgrSnRK3.5 | EgrSnRK3.1 | 0.08151 | 0.18191 | 0.448 |

| EgrSnRK3.2 | 0.06487 | 0.13926 | 0.466 | |

| EgrSnRK3.4 | 0.15223 | 0.15972 | 0.953 | |

| EgrSnRK3.3 | EgrSnRK3.8 | 0.0813 | 1.14857 | 0.071 |

| EgrSnRK3.6 | EgrSnRK3.22 | 0.35042 | 0.77327 | 0.453 |

| EgrSnRK3.10 | EgrSnRK3.13 | 0.10413 | 0.60606 | 0.172 |

| EgrSnRK3.11 | EgrSnRK3.14 | 0.13937 | 1.09741 | 0.127 |

| EgrSnRK3.12 | EgrSnRK3.24 | 0.19932 | 1.39897 | 0.142 |

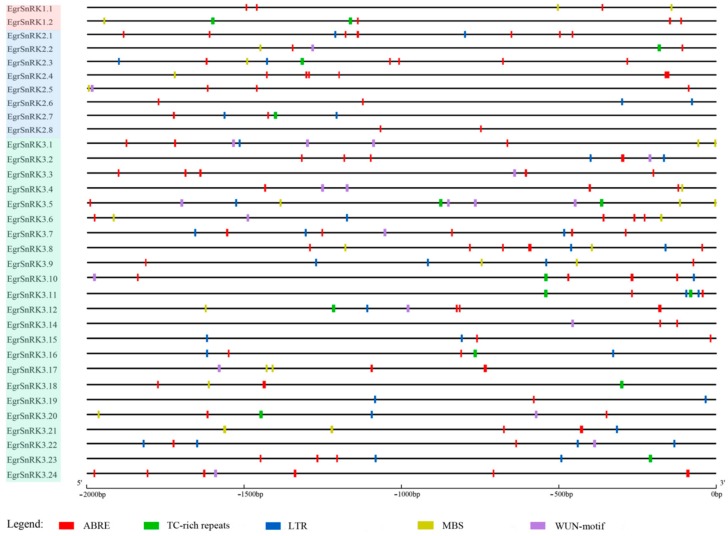

2.6. Promoter Analysis

To better understand the function and regulation of EgrSnRK genes, the promoter sequences of all genes were analyzed by using PlantCARE. A series of cis-elements related to the abiotic stress response, plant hormone response and plant growth and development were identified (Table S5). There are light responsiveness (G-Box, GT1-motif and I-box, etc.) and hormone-responsive elements, including the gibberellin-responsive, MeJA-responsiveness, ethylene-responsive, salicylic acid responsiveness, abscisic acid responsiveness and auxin-responsive, abiotic stresses elements (LTR, MBS and WUN-motif). In addition, some elements are involved in plant growth and development (i.e., CAT-box, HD-Zip 1, GC-motif, etc.). Five categories of cis-acting elements involved in the abscisic acid responsiveness, low-temperature responsiveness, drought-inducibility, wound-responsive and defense and stress responsiveness are shown in Figure 6. In addition, the number of these cis-acting elements in each EgrSnRK gene is shown in the Table 3. It was also found that EgrSnRK genes contained a variety of cis-acting elements of different types and the same element displayed multiple sites in the promoter region of one EgrSnRK gene.

Figure 6.

Cis-acting elements analysis of EgrSnRK genes in the promoter region. Gray lines represent promoter regions. Different color boxes represent different cis-acting elements. The ABRE elements are involved in the abscisic acid response, and TC-rich repeats elements are involved in defense and stress responses, the LTR elements are involved in low-temperature responses, the MBS elements are involved in drought-inducibility and the WUN-motif elements are involved in wound-responsive.

Table 3.

Numbers of each of the ABRE, TC-rich repeats, LTR, MBS and WUN-motif elements are shown.

| Gene Name | ABRE | TC-Rich Repeats | LTR | MBS | WUN-Motif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EgrSnRK1.1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK1.2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK2.1 | 7 | 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK2.2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EgrSnRK2.3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| EgrSnRK2.4 | 10 | 1 | |||

| EgrSnRK2.5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK2.6 | 2 | 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK2.7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK2.8 | 2 | ||||

| EgrSnRK3.1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| EgrSnRK3.2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.3 | 6 | 1 | |||

| EgrSnRK3.4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| EgrSnRK3.6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| EgrSnRK3.7 | 6 | 3 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.9 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.10 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EgrSnRK3.11 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.12 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.13 | |||||

| EgrSnRK3.14 | 2 | 1 | |||

| EgrSnRK3.15 | 2 | 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK3.16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.17 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.18 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.19 | 1 | 2 | |||

| EgrSnRK3.20 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EgrSnRK3.21 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| EgrSnRK3.22 | 3 | 5 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.23 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||

| EgrSnRK3.24 | 7 | 1 |

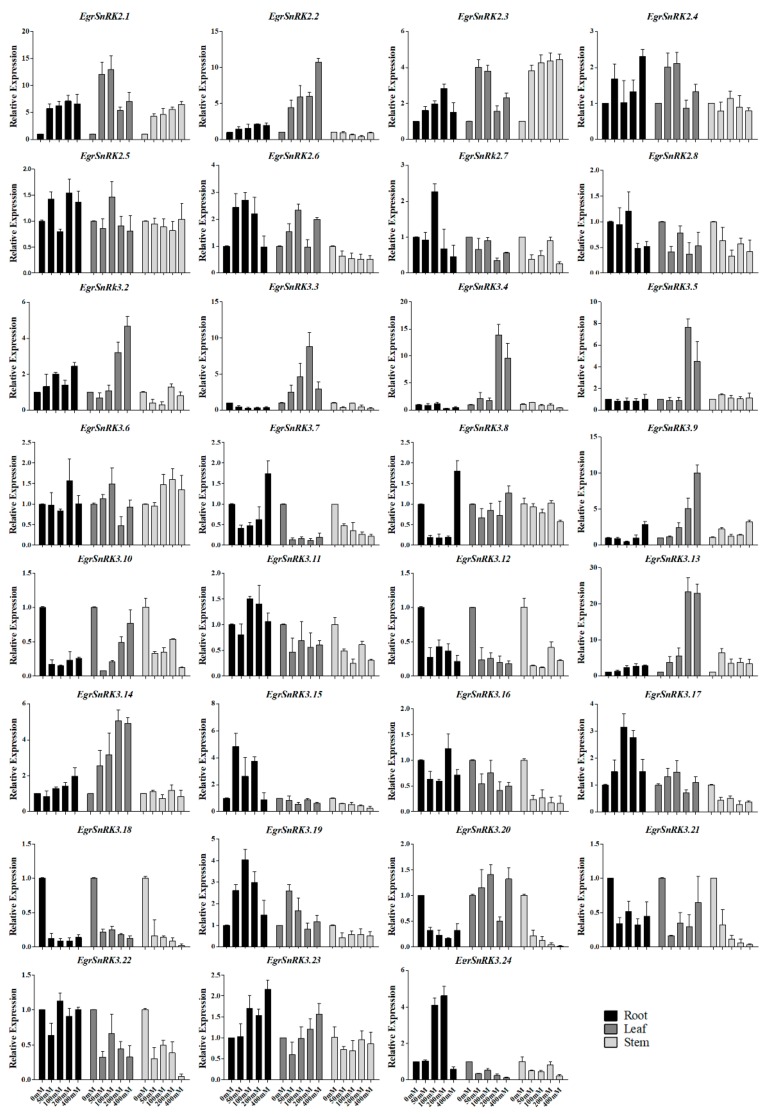

2.7. EgrSnRK Genes Expression under NaCl Treatment

To investigate whether the EgrSnRK2 and EgrSnRK3 genes were responsive to salt stress, the expression of EgrSnRK2s and EgrSnRK3s in different tissues (Root, Stem and leaf) of the E. grandis were detected by qRT-PCR after different concentrations of NaCl were used to treat eucalyptus seedlings for different time point. In addition, the expression of EgrSnRK3.1 was not detected in this experiment.

Figure 7 showed the expression pattern of different concentrations under conditions of a 200mM salt treatment. The expression levels of some genes (i.e., EgrSnRK3.10, EgrSnRK3.12, EgrSnRK3.18, EgrSnRK3.21 and EgrSnRK3.22) decreased to less than half that of CK (untreated seedlings) at different time points. It is clear that the expression levels of the EgrSnRK genes did not change significantly or were inhibited in the stem, while the expression of EgrSnRK2.1, EgrSnRK2.3, EgrSnRK3.9 and EgrSnRK3.13 were up-regulated more than 4-fold. Among the 31 genes in the leaf tissue, 12 of them were up-regulated, among which EgrSnRK2.1 and EgrSnRK2.2, EgrSnRK3.3, EgrSnRK3.4, EgrSnRK3.9 and EgrSnRK3.13 were up-regulated by more than 10-fold higher at certain concentrations. Specifically, the expression of the EgrSnRK3.13 was up-regulated more than 5-fold at low concentrations but reached high expression (more than 20-fold) levels when exposed to a much higher 200-400mM concentration. Additionally, some genes (i.e., EgrSnRK2.4, EgrSnRK3.2, EgrSnRK3.7, EgrSnRK3.8 and EgrSnRK3.9, EgrSnRK3.14 and EgrSnRK3.23) were up-regulated at its maximum value after 400 mM treatment, in which both EgrSnRK3.7 and EgrSnRK3.8 were inhibited at low concentrations and up-regulated at the maximum concentration.

Figure 7.

Expression analysis of 31 EgrSnRK genes following NaCl treatment at different concentrations as determined by qRT-PCR. The Y-axis and X-axis indicates relative expression levels and the time courses of stress treatments, respectively. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were obtained from three biological and three technical replicates. The error bars indicate standard deviation.

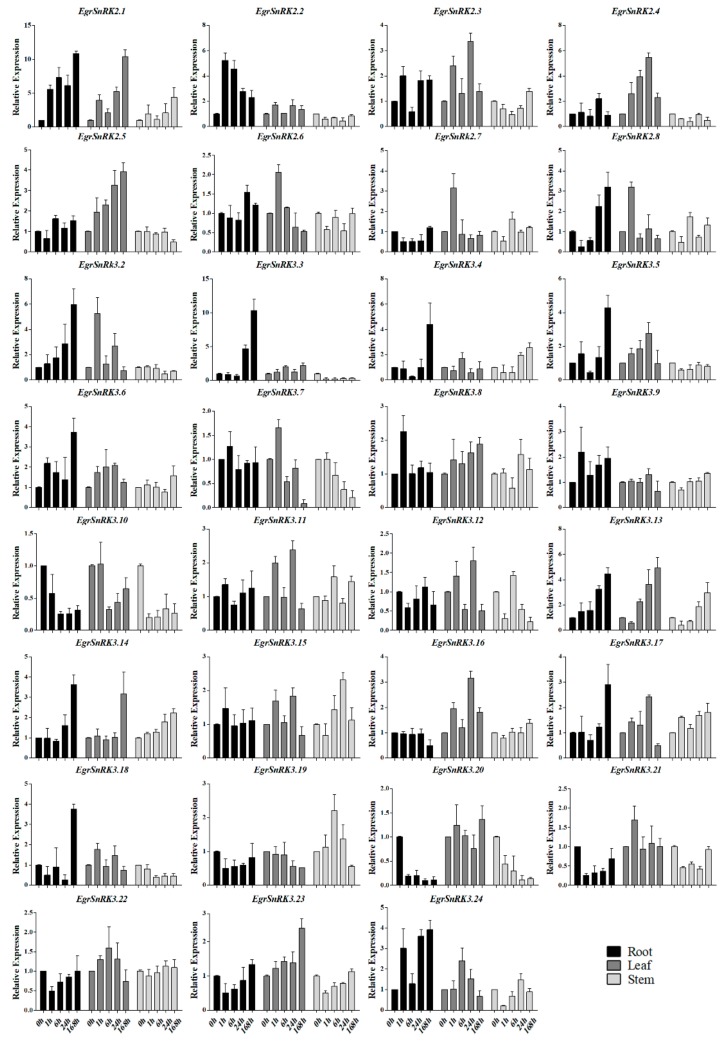

To further investigate whether or not EgrSnRKs were responsive to salt stress, different time periods of salt treatment were used. As shown in Figure 8, Of the 31 EgrSnRK genes, 12 of them (i.e., EgrSnRK2.1, EgrSnRK2.3, EgrSnRK2.8, EgrSnRK3.4, EgrSnRK3.6, EgrSnRK3.8, EgrSnRK3.11, EgrSnRK3.13, EgrSnRK3.14, EgrSnRK3.15, EgrSnRK3.17 and EgrSnRK3.24) were up-regulated at different time points, while only the expression of the EgrSnRK3.10 gene was down-regulated at all time points in different tissues (root, stem and leaf; Figure 7). Interestingly, the expression of the EgrSnRK2.1, EgrSnRK3.13 and EgrSnRK3.10 genes showed similar expression patterns in different tissues. For example, the expression levels of EgrSnRK3.13 increased over time. Some Eucalyptus genes are induced to be expressed more strongly than others. For example, the expression of EgrSnRK2.1, EgrSnRK2.2, EgrSnRK3.2 and EgrSnRK3.3 in the root tissue and expression of EgrSnRK2.1, EgrSnRK2.4, and EgrSnRK3.2 in the stem tissue were all up-regulated by a factor of more than five-fold. Of the 31EgrSnRK genes, 17 genes in the root, 29 genes in the leaf and 11 genes in the stem were up-regulated, respectively.

Figure 8.

Expression analysis of 31 EgrSnRK genes following NaCl treatment at different time periods as determined by qRT-PCR. The Y-axis and X-axis indicates relative expression levels and the time courses of stress treatments, respectively. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were obtained from three biological and three technical replicates. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

3. Discussion

The SnRK family plays an important role in the response to stress. Hence, the SnRK family and subfamily were analyzed in genome-wide studies in many plants, including A. thaliana, rice, distachyon, cotton, Hevea brasiliensis, and Vitis vinifera. However, the SnRK gene family has not been identified in E. grandis.

In this study, we identified 34 SnRK family members including two SnRK1 genes, eight SnRK2 genes and 24 SnRK3 (CIPK) genes in E. grandis. The phylogenetic analysis showed that similar members of the SnRK1 and SnRK2 subfamilies in diverse species, while the members of the SnRK3 subfamilies were the lowest (20) in the grape and the highest in rice (34). When compared with other species, the number of EgrSnRK genes in each subfamily was similar to the grape. Furthermore, many SnRK genes are clustered on the terminal branches of the phylogenetic tree, and the sequence similarity between some gene pairs was very high. Previous studies revealed that different subfamilies of the SnRK gene family had different conserved domains, but all genes had a protein kinase domain at the N-terminus. The gene sequences of genes belonging to the same subfamily were highly conserved and shared the same type of domains, indicating the functional diversity of the SnRK gene family (Figure 2).

Exon-intron structural diversification and motif composition played an important role in the evolution and function of many gene families. The number of exons varied in different subfamilies, and genes; the EgrSnRK1.1 and EgrSnRK1.2 genes had 10 exons, which was the same as that reported for BdSnRK1s [24]. Furthermore, EgrSnRK2s had nine exons, which was the same number as reported for VvSnRK2s and most AtSnRK2s, with the exception of AtSnRK2.6(11), AtSnRK2.4 (8) and AtSnRK2.8 (6) [44]. For the SnRK3 subfamily, in each reported species, we showed that there were either members with more than 10 exons or members with only one. The Figure 3 shows that most paralogous gene pairs contain the same exon number, although some gene pairs have different exon numbers. For instance, EgrSnRK3.14 and EgrSnRK3.20 lost one intron as compared with EgrSnRK3.11 and EgrSnRK3.21. To investigate conserved motifs in more detail, we determined the number and type of conserved motif for all EgrSnRK genes. The results indicated that the types and numbers of the motifs in the same subgroup were the same (EgrSnRK1 and EgrSnRK2; Figure 4), an observation that suggested a close evolutionary relationship within the subgroup. Similar to the results obtained for genetic structure, there were differences in the number and motifs of the members in EgrSnRK subfamily. Gene structure determines its function, and subfamilies of the SnRK gene family were involved in different plant growth stages and response to stresses.

In this study, 17 paralogous gene pairs were identified, two of which were involved in tandem duplication events (Table 2). Moreover, gene clusters were formed on chromosome 1, 2 and 7, respectively (Figure 5). Additionally, we identified 47 orthologous pairs between Eucalyptus and other species (i.e., A. thaliana, rice, poplar and Vitis vinifera). To further probe the selective pressure of EgrSnRK genes in evolution, we performed a sliding-window analysis of 17 paralogues gene pairs (Figure S2), indicating that different sites/encoding regions of gene pairs experienced differential selection pressures. The Ka/Ks ratios of the full-length coding sequences from 12 gene pairs were much lower than one, which indicated that most EgrSnRK genes underwent quite potent purifying selection. Meanwhile, this result showed that the sequence of the EgrSnRK gene family was highly conserved. In addition, we found that Ka/Ks in the domain regions of the encoded protein sequence was far lower than one, while Ka/Ks outside the domain regions was greater than one. Different protein domains in proteins are usually associated with different functions; thus, protein function and importance might exert a key influence on the rate of genetic evolution.

When plants are subjected to stress, through a series of signal transduction events that correspond to the appropriately stimulated transcription factors, those activated transcription factors bind to cis-acting elements of the target gene promoter, thereby activating the coordinated transcriptional expression of stress-resistant genes and creating regulatory responses to external stress signals [45,46]. Promoter analysis (Table S5) showed that some SnRK2s and SnRK3s harbored GCN4_motif cis-regulatory elements that are involved in endosperm expression in their promoters. The result implied that SnRK2s and SnRK3s were likely to play key roles in development. Moreover, the earliest SnRK1 of the plant was cloned from an endosperm cDNA library of the rye (Secale cereale L.) [14]. Moreover, some relatively recent studies had shown that SnRK2 and SnRK3 genes originated from the duplication of SnRK1 subfamily genes, and subsequently underwent rapid differentiation during evolution [15,24]. Most SnRK genes contain different types of cis-acting elements that are involved in plant growth, and various hormone and stress responses. Accumulating evidence suggests that SnRK genes are involved in the response to various abiotic stresses, including heat, drought and low temperatures. For example, GhSnRK2 genes (11/20) from G.hirsutum responded to cold, heat, salt and drought by analyzing data freely available on a publicly available transcriptome database [22]. In Hevea brasiliensis, 7 of 10 HbSnRK2s had relative high levels of transcript abundance by ABA, ET, and JA [25]. Furthermore, eight ZmCIPKs were significantly up-regulated by at least one stress stimuli (salt, cold and heat) based on the public data of the maize found in the GEO database and semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis [47].

To investigate the role of SnRK2s and EgrSnRK3s under salt treatment conditions, the expression levels of 31 SnRK genes were examined in the root, stem and leaf of E. grandis under various NaCl concentrations and time points under salt stress. Under conditions of a 200 mM salt treatment, it was found that 28 genes in the leaves, 20 in the root and 15 in the stem were up-regulated with increasing treatment time (Figure 8). It was worth noting that EgrSnRK2.2, EgrSnRK2.4, EgrSnRK2.5, EgrSnRK3.2, EgrSnRK3.3, EgrSnRK3.5 and EgrSnRK3.18 were strongly up-regulated in the leaves and root, but down-regulated in the stem. Moreover, Some SnRK genes peaked at 24 h or 168 h by salt treatment in different tissues, such as the relative expression level of EgrSnRK3.3 at 24 and 168 h, which was five- and 10-fold that of the root, respectively. It was a similar observation to that that found for the SnRK2 genes reported in cotton, wherein three genes were maximally at 24 h under salt treatment [23]. Both EgrSnRK2.7 and EgrSnRK2.8 were obviously (more than 3-fold) up-regulated after one hour and down-regulated at subsequent time points, where in the expression pattern was similar to that of GmSnRK2.1 and GmSnRk2.9 [22]. In the grapevine, the VvSnRK2.13 and VvSnRK2.7a genes were strongly induced under conditions of salt stress; however, the expression of VvSnRK2.14 was suppressed by exposure to salt stress [44]. Consistently, the VvSnRK2.13 homolog EgrSnRK2.1was up-regulated more than five-fold at 1, 6, and 24 h, and more than 10-fold by 168 h. In addition, EgrSnRK2.1 was up-regulated more than five-fold in different concentrations (Figure 7). EgrSnRK2.6 is the orthologue of VvSnRK2.14, which was slightly induced under different time points and concentrations of salt. According to previous documents, most SnRK2 and SnRK3 genes from A. thaliana, rice, soybean, maize and distachyon, responded to salt treatment—an observation that indicated the important role that the SnRK family plays in response to stress and in enhancing abiotic stress tolerance of plants. Such as overexpression of ZmCIPK21 can increase plant resistance to salt stress, and BdSnRK2.9 improves tolerance to osmotic and salt stresses in transgenic tobacco [24,47]. The expression of GhSnRK2.6 was shown to be up-regulated under salt conditions, and further demonstrated that GhSnRK2.6 improved salt tolerance in transgenic upland cotton and A. thaliana [48]. In addition, TaSnRK2.9 positively regulates the response of transgenic tobacco plants to drought and salt stress [30]. The EgrSnRK2.6 clusters with these gens, but was up-regulated to two-fold with increasing salt concentrations. Interestingly, the paralogous of EgrSnRK2.6 and EgrSnRK2.2 were strongly induced by 400 mM NaCl. Previous research showed that the OsSAPK4 significantly improve salt tolerance in transgenic rice [26]. Moreover, in A. thaliana TaSnRK2.4 enhanced salt tolerance [49]. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, EgrSnRK2.3, EgrSnRK2.4, EgrSnRK2.8, TaSnRK2.4, OsSAPK4 and ZmSnRK2.11 cluster together, while expression of ZmSnRK2.11 was negatively regulated following exposure to salt and drought stress. Both EgrSnRK2.3 and EgrSnRK2.4 were up-regulated by different concentrations of salt; however, EgrSnRK2.8 expression was down-regulated under those conditions. Salt and many other abiotic stresses stimuli inhibits plant growth. Thus, plants have to dispose of these conditions by several mechanisms. One of the mechanisms is through SOS. Three PtSOS2 genes were cloned and transformed into poplar to test its function [41]. Over-expression of PtSOS2 improves salt tolerance by mediating osmotic protection and by inducing the antioxidant enzyme system. EgrSnRK3.13, PtCIPK7 and AtCIPK6 cluster together, and AtCIPK6 is essential for plant growth and development under salt stress [34]. The expression of EgrSnRK3.13 was significantly (more than 20-fold) up-regulated with increasing concentrations in the stem. In addition, AtCIPK21 was reported to regulates osmotic and salt stress [37]. The EgrSnRK3.9, as a homologous pair of AtCIPK21, was up-regulated more than 10-fold at salt concentration of 200mM and 400mM. In summary, these results implied that EgrSnRK2s and EgrSnRK3s might play an essential role in the response to salt stress in E. grandis. This study provides available data for selecting available candidate genes in the EgrSnRK genes family and for further research on salt tolerance mechanism.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sequence Retrieval and Gene Identification

Protein and cDNA sequences of 39 SnRK genes in A. thaliana were downloaded as determined when interrogating the Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). Rice protein and cDNA sequences were obtained from the Rice Annotation Project (RAP) (https://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/). The whole E. grandis, grapevine and p. trichocarpa genome resources of the genome sequences, cDNA sequences and protein sequences, were downloaded from the Phytozome database. Local BLAST (E-value-5) searches were performed and based on the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile of SnRK gene domains from the Pfam database (http://pfam.janelia.org/search/sequence). All candidate sequences of SnRK genes were manually screened to leave only candidate genes containing the known conserved domains, which were further filtered based on the Pfam database [50], the NCBI Conserved Domain database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) [51] and the SMART database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) [52]. Bioinformatics analysis of E. grandis SnRK genes was performed and the number of amino acids, open reading frame (ORF) length, molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point(pI) for each gene was obtained using ExPASy (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/pi_tool.html). The subcellular localizations of the EgrSnRK genes were predicted using WoLP PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

4.2. Multiple Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

The ClustalX 2.11 [53,54] software program was used for multiple sequence alignment of 34 SnRK full-length protein sequences from E. grandis. On the basis of alignment, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the NJ method [53] in MEGA 7.0 and bootstrap analysis was performed using 1000 replicates for each node. An unrooted NJ tree of all SnRK protein sequences from A.thaliana, rice, grapevine, p. trichocarpa, maize and E. grandis was constructed using MEGA 7.0 [55].

4.3. Identification of Conserved Motifs and Analysis of Gene Structure

The online Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS: http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.ch) [56] was performed with CDSs and their corresponding genomic DNA sequences to show the exon-intron organization of SnRK genes. To identify conserved motifs of EgrSnRK proteins, the Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation (MEME) online program [57] (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/itro.html) was used with the following parameters: number of repetition = any, maximum number of motifs = 20; and optimum motif length = 6–200 residues.

4.4. Chromosomal Location

The E. grandis chromosome size information and location information of the SnRK genes were obtained from the Phytozome database. The online Map Gene2 Chrom web v2 (http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0/) was implemented to map the chromosomal positions and relative distances of EgrSnRK genes.

4.5. Ka and Ks Analysis of Homologous Pair

The method for defining paralogues and orthologues according to the method of Blanc and Wolfe [58]. This approach was achieved by BLASTN analysis of all nucleotide sequences in each species [59]. In a species, paired sequences with more than 300 bp alignments and over 80 percent homology were defined as a pair of paralogues. To identify putative orthologues between two different species (A and B), each sequence from species A was searched against all sequences from species B using BLASTN. Meanwhile, each sequence from species B was searched against all sequences from species A. The two sequences were defined as orthologues whose reciprocal best hits were each within ≥300 bp of the two aligned sequences.

The synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitutions per site between duplicated genes pairs were calculated based on the previous research methods. The protein sequences of gene pairs were aligned by MEGA 7.0, and the results were subsequently used to calculate Ks and Ka substitution rates with DnaSP 5 software [60,61].

4.6. Cis-Elements in the Promoter Regions of EgrSnRK Genes

Upstream sequences (2Kb) of each EgrSnRK-coding sequence was downloaded from the Phytozome database. And then PlantCARE software permitted analysis of cis-element distributions (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) in promoter regions [62].

4.7. Plant Materials, Growth Conditions and Salt Treatments

E. grandis GL1 cloned plants were used to measure gene expression, which were cultured by hydroponics for six weeks. The seedlings were grown in the greenhouse under14/10 h cycles of light/dark conditions at 23/27 °C and a humidity of 70 percent (Research Institute of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Guangzhou, China).

For salt treatments, the E. grandis clone GL1 seedlings were cultured with 200 mM NaCl solution instead of nutrient solution. All leaves, roots and stems were harvested at 0, 1, 6, 24 and 168 h after treatment, respectively. Furthermore, after 24 h of treatment with different concentrations of NaCl (0, 50, 100, 200, 400mM), the roots, stems and leaves were collected. All collected samples were wrapped in foil and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for total RNA extraction.

4.8. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was extracted from the leaves, roots and stems by using the Aidlab plant RNA kit (Aidlab Biotech, Beijing, China). The integrity and concentration of the RNA was detected by 1.5 percent agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop™ One/OneC (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Further, the first strand of cDNA was synthesized using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) based on the specification. Specific primers of the EgrSnRK genes were designed by Primer Premier 5.0 and then detected by NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC = BlastHome). In addition, the EgrEF1α was used as a house-keeping control gene [63]. Sequence information of all primers is shown in the attached Supplementary Table S6. QRT-PCR was performed on the Applied Biosystems 7500 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) by using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus; TaKaRa Biotechnology) with a 20μL sample volume. The reaction system was as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 34 s, followed by 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 60s, and 95 °C for 15 s. For each sample, we conducted three biological and three technical replicates. The relative expression levels of each gene were calculated by the standard 2−ΔΔCT [64] approach as compared with untreated control plants that were set as “1”. Processing the data and GraphPad 5 software was used to illustrate all of the data [65].

5. Conclusions

Accumulating documents suggest that the SnRK family plays an important role in plant growth and resistance. In this study, we presented a genome-wide identification of the EgrSnRK family in Eucalyptus grandis, including a phylogenetic tree, the gene structure, and the conserved motif, chromosomal location, and multiple sequence alignment. We identified 34 EgrSnRK genes and divided them into three distinct subgroups (i.e., EgrSnRK1, EgrSnRK2 and EgrSnRK3). Different subfamilies of the SnRK gene family had distinct conserved domains; however, all of the genes had a protein kinase domain at the N-terminal. Moreover, differential expression of EgrSnRK genes in the root, stem and leaf under different NaCl concentrations and duration of treatment were performed. From these studies, EgrSnRK genes showed various responses to salt treatments. In addition, these results laid a theoretical foundation for further study on the function of the EgrSnRK gene family and the differential tolerance of plants to salt.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/11/2786/s1. Table S1. The prediction of subcellular localization of EgrSnRK genes. Table S2. Details of SnRK genes from A. thaliana, rice, grapevine, and Populous trichocarpa. Table S3. Detailed information of the 20 motifs in the SnRK proteins of Eucalyptus grandis. Table S4. Ka/Ks ratios of orthologous gene pairs. Table S5. Promoter analysis of the EgrSnRK gene family. Table S6. List of primer sequences that were used for qRT-PCR analysis of the EgrSnRK genes.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Y.W., C.Z., C.F., and B.Z. Performed the experiments: Y.W. and H.Y. Analyzed the data: Y.W., H.Y., B.H., and Z.Q. Wrote the paper: Y.W. Participated in the design of this study and revised the manuscript: Y.W. and C.F. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Non-profit Research Institution of C.F.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as, or have the appearance of being, a potential conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Materials

The genome sequences of E. grandis, grapevine, Populus trichocarpa, and Arabidopsis were downloaded from Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). Rice protein sequences and cDNA sequences was provided by the Rice Annotation Project (RAP) (https://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/).

References

- 1.Cohen P. Review Lecture: Protein Phosphorylation and Hormone Action. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1988;234:115–144. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter T.J.C. Protein kinases and phosphatases: The yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Trend Biochem Sci. 1995;80:225. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tör M., Lotze M.T., Holton N. Receptor-mediated signalling in plants: Molecular patterns and programmes. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:3645–3654. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wrzaczek M., Hirt H.J.B. Plant MAP kinase pathways: How many and what for? Biol. Cell. 2012;93:81–87. doi: 10.1016/S0248-4900(01)01121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig A.A., Romeis T., Jones J.D. CDPK-mediated signalling pathways: Specificity and cross-talk. J. Exp. Bot. 2004;55:181–188. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hrabak E.M., Chan C.W.M., Michael G., Harper J.F., Choi J.H., Nigel H., Jorg K., Sheng L., Nimmo H.G., Sussman M.R., et al. The Arabidopsis CDPK-SnRK superfamily of protein kinases. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:666–680. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.011999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halford N.G., Hardie D.G. SNF1-related protein kinases: Global regulators of carbon metabolism in plants? Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;37:735–748. doi: 10.1023/A:1006024231305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celenza J.L., Carlson M. A yeast gene that is essential for release from glucose repression encodes a protein kinase. Science. 1986;233:1175–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.3526554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulik A., Wawer I., Krzywińska E., Bucholc M., Dobrowolska G. SnRK2 protein kinases--key regulators of plant response to abiotic stresses. Omics. 2011;15:859. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albrecht V., Ritz O., Linder S., Harter K., Kudla J. The NAF domain defines a novel protein-protein interaction module conserved in Ca2+-regulated kinases. Embo J. 2014;20:1051–1063. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masaru O., Yan G., Ursula H., Jian-Kang Z. A novel domain in the protein kinase SOS2 mediates interaction with the protein phosphatase 2C ABI2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034853100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baena-González E., Rolland F., Thevelein J.M., Sheen J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature. 2007;448:938. doi: 10.1038/nature06069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y.H., Shewry P.H., Barcelo P., Lazzeri P.A., Halford N. Expression of antisense SnRK1 protein kinase sequence causes abnormalpollen development and male sterility in transgenic barley. Plant J. 2001;28:431–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruslana R., Volodymyr R., Winfriede W., Ljudmilla B., Hans W. Repressing the expression of the SUCROSE NONFERMENTING-1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE gene in pea embryo causes pleiotropic defects of maturation similar to an abscisic acid-insensitive phenotype. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:263–278. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halford N.G., Hey S.J. Snf1-related protein kinases (SnRKs) act within an intricate network that links metabolic and stress signalling in plants. Biochem. J. 2009;419:247–259. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marie B., Hélène B.B., Christiane L.J. Identification of nine sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases 2 activated by hyperosmotic and saline stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41758–41766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anna-Chiara M., Sylvain M., Alain V., Francesca F., Giraudat J. Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell. 2002;14:3089–3099. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riichiro Y., Taishi U., Tsuyoshi M., Seiji T., Fuminori T., Kazuo S. The regulatory domain of SRK2E/OST1/SnRK2.6 interacts with ABI1 and integrates abscisic acid (ABA) and osmotic stress signals controlling stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5310–5318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Umezawa T., Yoshida R., Maruyama K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. SRK2C, a SNF1-related protein kinase 2, improves drought tolerance by controlling stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:17306–17311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407758101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Minami H., Kagaya Y., Hattori T. Differential activation of the rice sucrose nonfermenting1-related protein kinase2 family by hyperosmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1163–1177. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huai J., Wang M., He J., Zheng J., Dong Z., Lv H., Zhao J., Wang G. Cloning and characterization of the SnRK2 gene family from Zea mays. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:1861–1868. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao W., Cheng Y.H., Zhang C., Shen X.J., You Q.B., Guo W., Li X., Song X.J., Zhou X.A., Jiao Y.Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of theGmSnRK2Family in Soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1834. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z., Ge X., Yang Z., Zhang C., Zhao G., Chen E., Liu J., Zhang X., Li F. Genome-wide identification and characterization of SnRK2 gene family in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) BMC Genet. 2017;18:54. doi: 10.1186/s12863-017-0517-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L., Hu W., Sun J., Liang X., Yang X., Wei S., Wang X., Zhou Y., Xiao Q., Yang G. Genome-wide analysis of SnRK gene family in Brachypodium distachyon and functional characterization of BdSnRK2.9. Plant Sci. 2015;237:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo D., Li H.L., Zhu J.H., Wang Y., An F., Xie G.S., Peng S. Genomes, Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of SnRK2 family in Hevea brasiliensis. Tree Genet. Genome. 2017;13:86. doi: 10.1007/s11295-017-1168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diédhiou C.J., Popova O.V., Dietz K.J., Golldack D. The SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase SAPK4regulates stress-responsive gene expression in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hongying Z., Hongfang J., Guoshun L., Shengnan Y., Songtao Z., Yongxia Y., Peipei Y., Hong C. Cloning and characterization of SnRK2 subfamily II genes from Nicotiana tabacum. Mol. Biol. Res. 2014;41:5701. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song X., Yu X., Hori C., Demura T., Ohtani M., Zhuge Q. Heterologous overexpression of poplar SnRK2 genes enhanced salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:612. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H., Mao X., Jing R., Chang X., Xie H. Characterization of a common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) TaSnRK2. 7 gene involved in abiotic stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;62:975–988. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng J., Wang L., Wu Y., Luo Q., Zhang Y., Qiu D., Han J., Su P., Xiong Z., Chang J., et al. TaSnRK2. 9, a sucrose non-fermenting 1-related protein kinase gene, positively regulates plant response to drought and salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2018:9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.02003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He L., Yang X., Wang L., Zhu L., Zhou T., Deng J., Zhang X. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel cotton CBL-interacting protein kinase gene (GhCIPK6) reveals its involvement in multiple abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic plants. Biochem. Bioph. Res. 2013;435:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang F., Chen X.-J., Wang J.-H., Zheng J. Overexpression of a maize SNF-related protein kinase gene, ZmSnRK2. 11, reduces salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Agric.. 2015;14:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60872-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piao H.-L., Xuan Y.-H., Park S.H., Je B.I., Park S.J., Park S.H., Kim C.M., Huang J., Wang G.K., Kim M. OsCIPK31, a CBL-interacting protein kinase is involved in germination and seedling growth under abiotic stress conditions in rice plants. Mol. Cell. 2010;30:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripathi V., Parasuraman B., Laxmi A., Chattopadhyay D. CIPK6, a CBL-interacting protein kinase is required for development and salt tolerance in plants. Plant J. 2009;58:778–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huertas R., Olias R., Eljakaoui Z., Gálvez F.J., Li J., de Morales P.A., Belver A., Rodríguez-Rosales M. Overexpression of SlSOS2 (SlCIPK24) confers salt tolerance to transgenic tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1467–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim K.-N., Cheong Y.H., Grant J.J., Pandey G.K., Luan S. CIPK3, a calcium sensor–associated protein kinase that regulates abscisic acid and cold signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online. 2003;15:411–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pandey G.K., Kanwar P., Singh A., Steinhorst L., Pandey A., Yadav A.K., Tokas I., Sanyal S.K., Kim B.-G., Lee S.-C. Calcineurin B-like protein-interacting protein kinase CIPK21 regulates osmotic and salt stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:780–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halfter U., Ishitani M., Zhu J.K. The Arabidopsis SOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein SOS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3735–3740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Y., Xiong L., Song C.P., Gong D., Halfter U., Zhu J.K. A Calcium Sensor and Its Interacting Protein Kinase Are Global Regulators of Abscisic Acid Signaling in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:233–244. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J., Ishitani M., Halfter U., Kim C.S., Zhu J.K. The Arabidopsis thaliana SOS2 gene encodes a protein kinase that is required for salt tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3730–3734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou J., Wang J., Bi Y., Wang L., Tang L., Yu X., Ohtani M., Demura T., Zhuge Q. Overexpression of PtSOS2 enhances salt tolerance in transgenic poplars. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014;32:185–197. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0640-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myburg A.A., Dario G., Tuskan G.A., Uffe H., Hayes R.D., Jane G., Jerry J., Erika L., Hope T., Diane B. The genome of Eucalyptus grandis. Nature. 2014;510:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shao Y., Qin Y., Zou Y., Ma F. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the SnRK2 gene family in Malus prunifolia. Gene. 2014;552:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J.Y., Chen N.N., Cheng Z.M., Xiong J.S. Genome-wide identification, annotation and expression profile analysis of SnRK2 gene family in grapevine. Aust. J. Grape Wine R. 2016;22:478–488. doi: 10.1111/ajgw.12223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali G.M., Komatsu S. Proteomic analysis of rice leaf sheath during drought stress. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:396–403. doi: 10.1021/pr050291g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarda X., Tousch D., Ferrare K., Legrand E., Dupuis J., Casse-Delbart F., Lamaze T. Two TIP-like genes encoding aquaporins are expressed in sunflower guard cells. Plant J. 1997;12:1103–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12051103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X., Gu Z., Xin D., Hao L., Liu C., Huang J., Ma B., Zhang H. Genomics, Identification and characterization of putative CIPK genes in maize. J. Gent. Genom. 2011;38:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jcg.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su Y., Wang Y., Zhen J., Zhang X., Chen Z., Li L., Huang Y., Hua J. SnRK2 Homologs in Gossypium and GhSnRK2.6 Improved Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Upland Cotton and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2017;35:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11105-017-1034-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao X.G., Zhang H.Y., Tian S.J., Chang X.P., Jing R.L. TaSnRK2.4, an SNF1-type serine/threonine protein kinase of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), confers enhanced multistress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:683–696. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finn R.D., Coggill P., Eberhardt R.Y., Eddy S.R., Mistry J., Mitchell A.L., Potter S.C., Punta M., Qureshi M., Sangradorvegas A. The Pfam protein families database: Towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;(Database issue):Database–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J.B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., DeWeese-Scott C., Fong J.H., Geer L.Y., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R., et al. CDD: A Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39(Suppl. 1):D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P. SMART 7: Recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu B., Jin J., Guo A.-Y., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2014;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Suppl. 2):W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blanc G., Wolfe K.H. Widespread paleopolyploidy in model plant species inferred from age distributions of duplicate genes. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1667–1678. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Librado P., Rozas J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rozas J. Bioinformatics for DNA Sequence Analysis. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2009. DNA sequence polymorphism analysis using DnaSP; pp. 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Q., Wang H., Zhang Z., Wu J., Feng Y., Zhu Z. Divergence in function and expression of the NOD26-like intrinsic proteins in plants. BMC Genom. 2009;10:313. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan C., Guo G., Yan H., Qiu Z., Liu Q., Zeng B. Characterization of Brassinazole resistant (BZR) gene family and stress induced expression in Eucalyptus grandis. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2018;24:821–831. doi: 10.1007/s12298-018-0543-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C T method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bryfczynski S. Proceedings of the 47th Annual Southeast Regional Conference. ACM; New York, NY, USA: 2009. GraphPad: A CS2/CS7 tool for graph creation; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences of E. grandis, grapevine, Populus trichocarpa, and Arabidopsis were downloaded from Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). Rice protein sequences and cDNA sequences was provided by the Rice Annotation Project (RAP) (https://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/).