Abstract

Background. Lifestyle medicine has emerged as a transformational force in mainstream health care. Numerous health promotion and wellness programs have been created to facilitate the adoption of increased positive, modifiable health behaviors to prevent and lessen the effects of chronic disease. This article provides a scoping review of available health promotion interventions that focus on healthy adult populations in the past 10 years. Methods. We conducted a scoping review of the literature searching for health promotion interventions in the past 10 years. Interventions were limited to those conducted among healthy adults that offered a face-to-face, group-based format, with positive results on one or more health outcomes. We then developed a new health promotion intervention that draws on multiple components of included interventions. Results. Fifty-eight articles met our inclusion criteria. Physical activity was the primary focus of a majority (N = 47) of articles, followed by diet/nutrition (N = 40) and coping/social support (N = 40). Conclusions. Efficacious health promotion interventions are critical to address the prevention of chronic disease by addressing modifiable risk factors such as exercise, nutrition, stress, and coping. A new intervention, discussed is this article, provides a comprehensive approaches to health behavior change and may be adapted for future research.

Keywords: health promotion, lifestyle interventions, diet, physical activity, health behavior change

‘Numerous health promotion and wellness programs have been created to facilitate the adoption of increased positive, modifiable health behaviors to prevent and lessen the effects of chronic disease.’

Chronic diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes, are a growing epidemic both nationally and internationally. Globally, chronic diseases kill more people annually than all other causes combined.1 Several risk factors are common to most chronic diseases, including unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and tobacco use. According to the World Health Organization, at least 80% of all heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes and more than 40% of all cancers would be prevented if these risk factors were eliminated.1 In addition to the putative roles of larger policy and environmental factors that influence disease risk, morbidity, and mortality, the need for cost-effective, scalable lifestyle interventions delivered at the individual and group levels cannot be understated.

Lifestyle medicine has emerged as a transformational force in mainstream health care. Numerous health promotion and wellness programs have been created to facilitate the adoption of increased positive, modifiable health behaviors to prevent and lessen the effects of chronic disease. In fact, over the past 20 years there have been a myriad of randomized clinical trials to establish the evidence base of lifestyle and health promotion interventions in both healthy and disease-based samples. Due to the sheer heterogeneity of intervention aims, educational components, modes of delivery, and outcomes of interest, it has become challenging to determine what has been helpful and for whom. Scoping reviews, while less common than systematic reviews, can be helpful when surveying a broad topic scope in order to provide an overarching view of the literature, identify gaps, and guide new research questions.2 Scoping reviews can be a particularly useful platform to guide researchers before conducting a more targeted systematic review. Arksey and O’Malley put forth guidelines for conducting scoping reviews, using the following steps: (1) identifying the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.3 The purpose of this article is to (1) provide a scoping review of existing health behavior interventions relevant to lifestyle medicine; (2) synthesize common elements of studies that indicated positive findings with healthy, nondisease samples; and (3) describe how these studies have informed the development of a new evidence informed intervention called “HealthPro.”

Methods

Literature Search and Strategy

The overarching research question guiding this review was, “What techniques, components, and/or approaches have effective randomized clinical trials used to help individuals promote and maintain healthy lifestyles?” We used the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase to identify and extract eligible studies from the past 10 years for this scoping review using the following keywords: “health promotion” OR “lifestyle” OR “wellness” in combination with any of the following keywords: “class” OR “course” OR “intervention” OR “program.” We also filtered results by the following criteria: published in English, between 2006 and 2016, peer-reviewed journal, clinical trial, adults, and human.

Eligibility Criteria

Interventions

We included group-based lifestyle or health promotion intervention studies that consisted of at least 2 or more group meeting sessions. We also limited our inclusion of interventions to only those offered in-person, as previous research has indicated that these are more effective than online and phone-based interventions.4

Study Type

Given the large scope of our search topic, we included only original articles of published randomized controlled trials (including wait-list control designs), as this is the current gold standard for evaluating efficacy and effectiveness of interventions. We excluded observational or nonrandomized studies or published abstracts. We excluded studies that did not specifically aim to improve more than one lifestyle medicine-relevant outcome goal (eg, weight reduction, stress reduction, increased exercise, improved eating habits, etc) and studies that did not have any significant effects on their target outcomes.

Patient Populations and Relevance to Lifestyle Medicine

Given the large volume and variability of health promotion interventions, we limited our studies to only those examining healthy adults; individuals 18+ with no medical diagnoses. We did include studies with pregnant women and “at-risk” populations, such as prediabetes and prehypertension. We excluded studies such as those including patients with cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Results

Literature Search

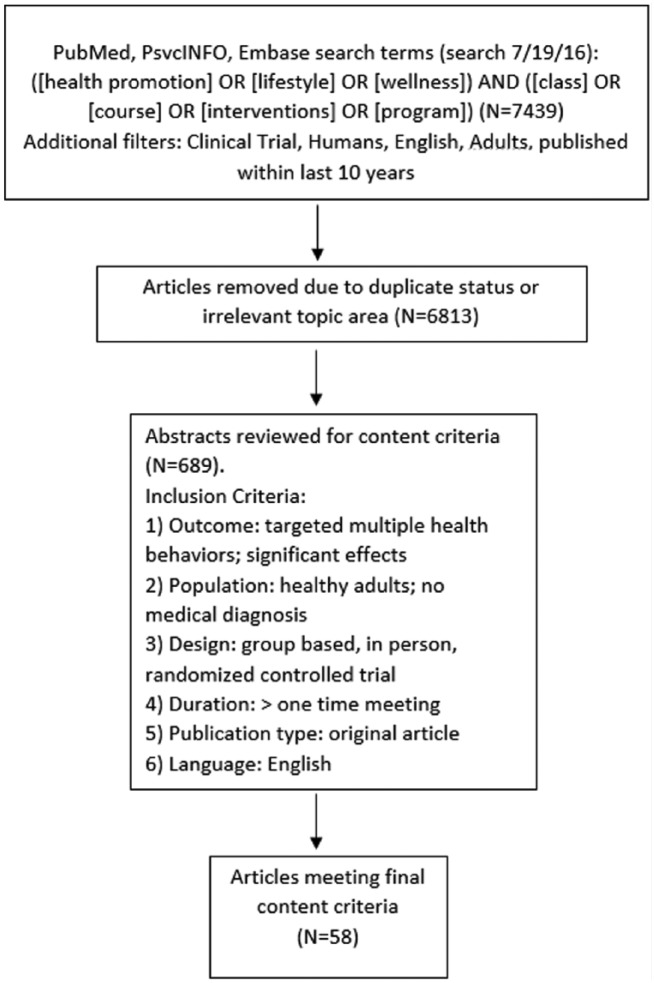

Our initial search yielded 7439 articles, which after reexamination and removal of duplications and nonrelevant articles was reduced to 689 articles for full abstract review. We divided the remaining abstracts among 4 of the authors (SS, EC, KS, DV) and carefully read all for inclusion criteria. Any time a reviewer was uncertain of whether or not to include an article, the first author and senior author reviewed the abstract to determine its inclusion status. Through this process, we eliminated an additional 631 that did not meet all relevant criteria. This led to a final selection of 58 articles for presentation in this scoping review. See Figure 1 for literature search flow chart. Descriptive characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Literature review flow chart.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

| Author | Year | Content | SN | Length | Theoretical Foundation | Delivery Methods | Outcomes Measured | Instructor | Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | Diet/Nutrition | Alcohol and/or Tobacco Reduction | Relaxation and Stress Mngt | Coping and Social Support | Sleep Hygeine | Goal Setting | ≤10 | >10 | <1 Hour | 1-2 Hours | >2 Hours | Social Cognitive Theory | Transtheoretical Model | Social Learning Theory | Cognitive Theory | Motivational Interviewing | Self-Determination Theory | General Health Behavior Theory | Discussion and Lecture | Experiential Exercises | Individual Counseling | Daily Diaries/Self-Monitoring | Infomational Materials | Group Exercise Classes | Physical Activity/Fitness | Fruit and Vegetable Intake/Nutrition | Weight Loss/BMI | Biomarkers (glucose, CRP) | Quality of Life | Alcohol and/or Tobacco Intake | Mobility/Frailty/Bone Density | Psychosocial Well-being/Self-Efficacy | Occupational Functioning | CVD Risk/Blood Pressure | Stress and Negative Affect | Health Care Professional | Peer Educator | Physical Trainor | Other | Elderly | Disadvantaged | “At Risk” CVD/Hypertension/Diabetes | Employees | Overweight | Other | ||

| Ackerman5 | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aira6 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ash7 | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atlantis8 | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Barham9 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bo10 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buman11 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christensen12 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cichocki13 | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clark14 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coffeng15 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critchley16 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cullen17 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dimou18 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edries19 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elliot20 | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eriksson21 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Esch22 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fielding23 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figueira24 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Funk25 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Folta26 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From27 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gesell28 | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goyer29 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guillaumie30 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamman31 | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heideman32 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hinderliter33 | 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hirosaki34 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hui35 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imayama36 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ipsen37 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Islam38 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x* | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Johansen39 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jorna40 | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kaholokula41 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kandula42 | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katzer43 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Keyserling44 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kimura45 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kuller46 | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Limm47 | 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MacKinnon48 | 2010 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marshall49 | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McGrady50 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McGrady51 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Merrill52 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Milani53 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x* | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Millear54 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Olafsdottir55 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opdenacker56 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perry57 | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resnick58 | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x* | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saadat59 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Teri60 | 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x* | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Umanodan61 | 2009 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x* | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weber62 | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x* | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: SN, number of sessions; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Represents outcomes that the intervention positively influenced.

Brief Overview of Studies

The majority of articles focused on increasing physical activity and/or improving dietary behaviors (n = 52). Several studies also incorporated social support, teaching effective coping skills, and goal setting, but exercise and weight loss were the primary outcomes. Most courses were 1 to 2 hours in length, with an intervention period between 6 and 12 weeks, with a median number of sessions of 10.5. Core components of many interventions included discussion and lecture, experiential exercises (eg, group trips to the grocery store, reading food labels), and group exercise classes. Intervention instructors’ training levels varied, but most course facilitators had advanced training as dieticians, personal trainers, or health care professionals; a few courses were peer facilitated, others were taught by on-site staff members and/or research staff. Often articles stated that curriculum content was grounded in one or multiple theories of behavior change, but did not specify a given theory. The most commonly cited theory was social cognitive theory. Participant populations were somewhat evenly distributed between elderly; socioeconomically disadvantaged groups; populations at risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and so on; employees; overweight; and otherwise healthy adults (eg, students, pregnant women).

Literature Review Synthesis and Development of “HealthPro”

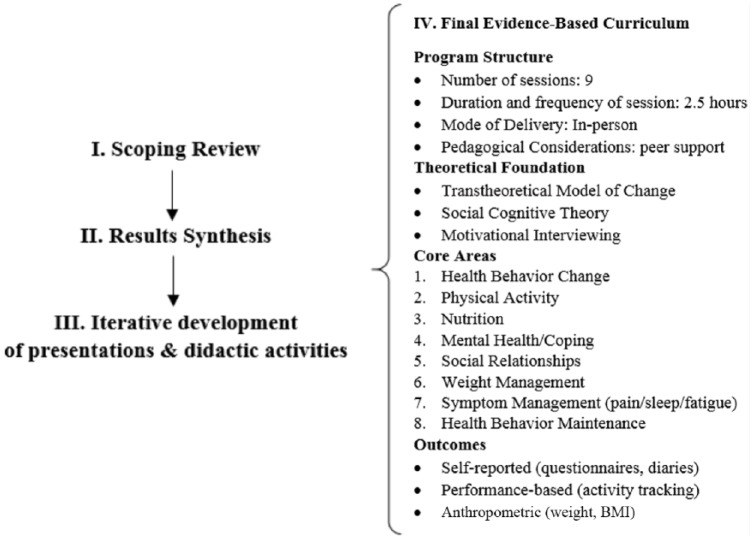

Synthesizing the findings from the scoping review, we set about creating a comprehensive health promotion intervention: “HealthPro.” See Figure 2 for a visual depiction of the development process.

Figure 2.

HealthPro development process.

Program Structure and Delivery

In the studies we reviewed, there was a virtual tie between those that included less than 10 separate sessions (48%) and more than 10 sessions (52%). After considering practical and logistical constraints, we proposed that the HealthPro curriculum comprise 9 consecutive weekly sessions (including orientation), plus an in-person gathering between weeks 6 and 7 to reinforce course teachings. This experience allowed participants to dive deeper into lifestyle medicine topics through viewing selected segments of popular documentary films (Food Inc, Fed Up, and Forks Over Knives) followed by facilitated group discussion. Our review found that the majority of intervention sessions were between 1 and 2 hours in length (55%); therefore, we planned the HealthPro sessions to be roughly 2 to 2.5 hours each. We followed the most frequently used delivery methods, including discussion and lecture (78%), experiential exercises (52%), providing informational materials (45%), engaging in periods of mild stretching (45%), and using daily diaries and self-monitoring throughout (24%). Counseling participants at the individual level (40%) was generally avoided given the group-based nature of this program.

Theoretical Foundation

We used findings from the summarized literature to inform the HealthPro curriculum. Since all reviewed studies reported utilizing a theoretical foundation of health behavior change, we drew from the 3 most commonly used theories and applications, including social cognitive theory63 (24%), the transtheoretical model of change64 (16%), and motivational interviewing65 (14%). Specifically, session 1 of the curriculum educates participants on the importance of being ready to make health behavior changes and provides them with an opportunity to assess their own readiness for change and identify any barriers that may exist. In each class, participants are shown different brief educational videos related to the session topics, which offer modeling opportunities to learn and incorporate new behaviors, akin to principles of social cognitive theory.63 Finally, HealthPro instructors draw from aspects of motivational interviewing when engaging participants about their weekly goals, progress, and challenges.

Curriculum Content

We included the most frequently studied health promotion areas such as physical activity (81%), diet/nutrition (69%), goal setting (60%), coping and social support (69%), and emotional well-being/stress management (40%). While there is general guidance on avoiding tobacco-related products and abstaining from or consumption of alcoholic beverages in moderation, these are not primary curriculum foci given the general health promotion focus of the course. Per recommendations, we also used the scoping review to identify potential gaps in content coverage, and therefore included specific sessions on health behavior change principles and maintenance, weight management, mental health, and symptom management (eg, joint pain/discomfort, sleep hygiene).

Class Components

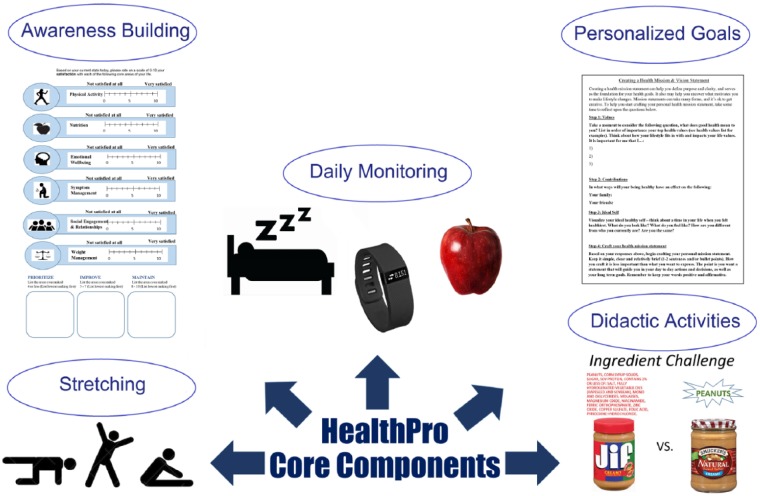

See Figure 3 for examples of HealthPro core components.

Figure 3.

HealthPro core components.

Informational Presentations

Each of the weekly classes includes a 30- to 45-minute informational presentation given by the facilitator to introduce participants to the respective week’s course topic and provide a background of relevant scientific literature.

Goal Setting

Participants are instructed to make personalized goals each week based on the current week’s course topic. Course instructors check in with participants to ensure that goals are specific, measureable, attainable, realistic, and time sensitive and help participants make modifications if necessary. Participants are given a diary to log progress toward their goal during the week. At the beginning of each class, instructors guide participants through group discussion of how their goals went during the previous week, and strategies for maintaining them.

Activity Monitoring and Awareness Building

Participants are given Fitbits to monitor their daily steps and number of hours they sleep each night. Homework for certain weeks also includes tracking behaviors relevant to the course topic: week 3 has a food diary, week 4 has a coping with difficult situations thought calendar, and week 7 has a sleep hygiene log.

Didactic Activities

Didactic worksheets and activities were designed for each course topic to engage participants in the material and to further build awareness of factors influencing their health behaviors. See Table 2 for a description of didactic activities by class.

Table 2.

Didactic Activities by Class.

| Class 1 | Health Mission and Vision Statement: Participants are asked to reflect on what being healthy means to them, what their ideal healthy self looks like, and create a “mission statement” that reflects their core values. |

| Intention Assessment: Participants rate their readiness for change for a variety of health behaviors such as eating less red meat and fewer dairy products, reducing alcohol intake, exercising more, and so on. | |

| Core Areas of Health and Wellness: Participants rate how satisfied they are in the core health areas to be covered in class: physical activity, nutrition, emotional well-being, social engagement and relationships, symptom management, and weight management. | |

| Class 2 | Types of Exercise: Participants describe different examples of exercises as related to the 4 categories of physical activity (incidental, aerobic, resistance, stretching) and identify personal feelings/experience associated with each. |

| Class 3 | Healthy Swap: Participants are asked to come up with one unhealthy item they consistently eat or drink to replace with a healthier alternative, such as swapping soda for water. |

| Food Diary: Participants track their food and beverage consumption every day for a week according to the main food groups. | |

| Class 4 | My Personal Coping Style: Participants reflect on a previous experience and identify their use of problem versus emotion-focused coping and active versus passive coping, and brainstorm new strategies to implement in future situations. |

| Coping with Difficult Situations Calendar: Participants track stressful events, associated automatic thoughts and behavioral responses, and identify adaptive ways of coping. | |

| Class 5 | Myers Briggs (MB) Assessment: Participants take MB self-assessment and read through various ways of communicating and relating to other individuals with similar/different personality traits.66 |

| Different Hats: Participants list different social roles they fill (ie, father/mother, son/daughter, husband/wife, athlete, employee) and identify others in each social network. | |

| Class 6 | BMI and BMR Calculations: Participants calculate their individual body mass index (BMI) and basal metabolic rate (BMR) and reflect on implications for weight management goals. |

| Class 7 | Symptom Inventory: Participants inventory symptoms they experience on a weekly basis (pain, fatigue, etc). |

| Sleep Log: Participants log various components of their sleep hygiene, such as waking time, caffeinated beverages, exercise, and hours slept. | |

| Class 8 | Mission Statement Revisiting: Participants reflect on progress they have made over the course toward their health mission statement and make any revisions they wish to implement for the future based on what they have learned in class. |

| Classes 1-7 homework | Weekly Goal Worksheet: Participants create a goal for the week based on the course topic and identify barriers, resources and strategies related to their goal. |

| Goal Tracking Sheet: Participants log their daily steps, sleep hours, and progress made toward their weekly goal. |

Low-Intensity Physical Activity

Courses are structured to include up to 20 minutes of low-intensity strength training and stretching exercises. However, discussion and didactic activities are given precedence and in-class physical activity may be cut for time purposes. The participant workbook includes instructions for the exercises and participants are instructed to practice these on their own at home.

Outcomes

While individual researchers may choose to evaluate hypothesis-driven outcomes at their own discretion, we anticipate that HealthPro outcomes of interest will be consistent with some of the most frequently studied ones in the literature, including changes in physical activity/fitness-related outcomes (69%), changes in weight/body mass index (64%), decreases in stress and negative affect (48%), increases in fruit and vegetable consumption (41%), increases in self-efficacy (34%), decreases in blood pressure (34%), and increases in quality of life (33%).

Discussion

In this scoping review, we provided an overview of effective health promotion interventions for healthy adults. We then described the development of a comprehensive health promotion intervention, informed by these findings. Our initial search yielded more than 6000 studies, of which 58 met our study inclusion criteria. This reflects the sheer magnitude of behavioral health research interventions that focus on lifestyle change. As the medical field continues to shift toward a focus on prevention, we anticipate these types of studies will continue to grow. As such, it is critical to understand what approaches have been most successful in creating health behavioral change. A recent systematic meta-review by Kristen et al4 put forth a set of recommendations for future health promotion intervention design for optimal efficacy. They suggested that interventions should be behavior oriented, grounded in theoretical frameworks focused on health determinants, and offered in-person to provide opportunities to interact with other participants and the instructor. The HealthPro intervention does just this, drawing on multiple theories of behavior change to create a multidimensional, empirically grounded curriculum that can be used in adults with a variety of health backgrounds.

There are some limitations that should be taken into consideration when examining this review. Primarily, it is important to note that this is a scoping review, not systematic, and therefore it is likely that we did not capture every health promotion intervention in existence, nor were selected studies evaluated using rigorous bias indices. However, the purpose of this review is to provide a general summary of the methodology and curricula current interventions are using, and to apply that information to design an intervention that draws on evidence and frequently used best practices. Additionally, in order to refine the scope of our review, we limited articles to only those implemented with healthy adults. This was done due to the high volume of articles returned in our search. Thus, several health interventions, such as those for individuals with diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and other medical diagnoses, are not mentioned here. A different interpretation of “healthy adults” could have led to the inclusion of a different set of studies. Finally, because HealthPro is in its nascent stage, we are not able to report on the efficacy of the program yet. Currently, the HealthPro program is being tested in a randomized controlled trial, evaluating its effects compared to a matched mindfulness based stress reduction intervention for men with prostate cancer and their spouses.67 Details regarding the design and protocol for this study will be provided in a subsequent publication. The study can be found on clinicaltrials.gov under the ID NCT02871752.

Despite these limitations, the HealthPro curriculum has a number of strengths that set it apart from existing multiweek health promotion programs. Namely, unlike many interventions that have limited their curriculum to diet and exercise, HealthPro covers a wide range of health topics to support a comprehensive approach to wellness, including mental, emotional, social, and physical health. Additionally, whereas many interventions were led by trained health professionals, HealthPro can be led by an individual with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree and is offered in a group format, making it more cost-effective than some alternatives. Furthermore, the format, content, and modular nature of HealthPro lends itself well to subsequent translation into online and digital health applications. Finally, because HealthPro is not catered toward a specific clinical population, it can easily be adapted and tailored for other research needs.

Conclusions

The overwhelming burden of chronic disease calls for the development and dissemination of affordable, theory-based, health promotion and behavioral interventions. HealthPro is a 9-week lifestyle intervention targeting physical, mental, and social well-being that may be applicable to a variety of health and at-risk adult populations. Further investigations may also employ HealthPro among different clinical populations and evaluate its efficacy in initiating and maintaining health behavior change. Course materials for HealthPro can be made available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported in part by the John and Carol Walter Center for Urological Health, NorthShore University Health System; an NIH/NCI training Grant CA193193; and an NIH R01 Grant R01 CA19333102.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Overview—Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/part1/en/index11.html. Accessed December 22, 2016.

- 2. Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. “Scoping the scope” of a Cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33:147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kristen L, Ivarsson A, Parker J, Ziegert K. Future challenges for intervention research in health and lifestyle research: a systematic meta-literature review. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2015;10:27326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ackermann RT, Liss DT, Finch EA, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial for preventing type 2 diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2328-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aira T, Wang W, Riedel M, Witte SS. Reducing risk behaviors linked to noncommunicable diseases in Mongolia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1666-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ash S, Reeves M, Bauer J, et al. A randomised control trial comparing lifestyle groups, individual counselling and written information in the management of weight and health outcomes over 12 months. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1557-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atlantis E, Chow CM, Kirby A, Fiatarone Singh MA. Worksite intervention effects on physical health: a randomized controlled trial. Health Promot Int. 2006;21:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barham K, West S, Trief P, Morrow C, Wade M, Weinstock RS. Diabetes prevention and control in the workplace: a pilot project for county employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bo S, Ciccone G, Guidi S, et al. Diet or exercise: what is more effective in preventing or reducing metabolic alterations? Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:685-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buman MP, Giacobbi PR, Jr, Dzierzewski JM, et al. Peer volunteers improve long-term maintenance of physical activity with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(suppl 2):S257-S266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christensen JR, Faber A, Ekner D, Overgaard K, Holtermann A, Sogaard K. Diet, physical exercise and cognitive behavioral training as a combined workplace based intervention to reduce body weight and increase physical capacity in health care workers: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cichocki M, Quehenberger V, Zeiler M, et al. Effectiveness of a low-threshold physical activity intervention in residential aged care: results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:885-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark F, Jackson J, Carlson M, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:782-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coffeng JK, Hendriksen IJ, Duijts SF, Proper KI, van Mechelen W, Boot CR. The development of the Be Active & Relax “Vitality in Practice” (VIP) project and design of an RCT to reduce the need for recovery in office employees. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Critchley CR, Hardie EA, Moore SM. Examining the psychological pathways to behavior change in a group-based lifestyle program to prevent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:699-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cullen KW, Lara Smalling A, Thompson D, Watson KB, Reed D, Konzelmann K. Creating healthful home food environments: results of a study with participants in the expanded food and nutrition education program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:380-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dimou PA, Bacopoulou F, Darviri C, Chrousos GP. Stress management and sexual health of young adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Andrologia. 2014;46:1022-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edries N, Jelsma J, Maart S. The impact of an employee wellness programme in clothing/textile manufacturing companies: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RK, Pickering MA. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects) firefighter study: outcomes of two models of behavior change. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:204-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eriksson MK, Franks PW, Eliasson M. A 3-year randomized trial of lifestyle intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction in the primary care setting: the Swedish Bjorknas study. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Esch T, Sonntag U, Esch SM, Thees S. Stress management and mind-body medicine: a randomized controlled longitudinal evaluation of students’ health and effects of a behavioral group intervention at a middle-size German university (SM-MESH). Forsch Komplementmed. 2013;20:129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fielding RA, Rejeski WJ, Blair S, et al. The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Study: design and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1226-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Figueira HA, Figueira AA, Cader SA, et al. Effects of a physical activity governmental health programme on the quality of life of elderly people. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:418-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Funk KL, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, et al. PREMIER: a trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control: intervention design and rationale. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9:271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Folta SC, Lichtenstein AH, Seguin RA, Goldberg JP, Kuder JF, Nelson ME. The StrongWomen-Healthy Hearts program: reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors in rural sedentary, overweight, and obese midlife and older women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1271-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. From S, Liira H, Leppavuori J, Remes-Lyly T, Tikkanen H, Pitkala K. Effectiveness of exercise intervention and health promotion on cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men: a protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gesell SB, Katula JA, Strickland C, Vitolins MZ. Feasibility and initial efficacy evaluation of a community-based cognitive-behavioral lifestyle intervention to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy in Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1842-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goyer L, Dufour R, Janelle C, et al. Randomized controlled trial on the long-term efficacy of a multifaceted, interdisciplinary lifestyle intervention in reducing cardiovascular risk and improving lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. J Behav Med. 2013;36:212-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guillaumie L, Godin G, Manderscheid JC, Spitz E, Muller L. The impact of self-efficacy and implementation intentions-based interventions on fruit and vegetable intake among adults. Psychol Health. 2012;27:30-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2102-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heideman WH, Nierkens V, Stronks K, et al. DiAlert: a lifestyle education programme aimed at people with a positive family history of type 2 diabetes and overweight, study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hinderliter AL, Sherwood A, Craighead LW, et al. The long-term effects of lifestyle change on blood pressure: one-year follow-up of the ENCORE study. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:734-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirosaki M, Ohira T, Kajiura M, et al. Effects of a laughter and exercise program on physiological and psychological health among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:152-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hui A, Back L, Ludwig S, et al. Lifestyle intervention on diet and exercise reduced excessive gestational weight gain in pregnant women under a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119:70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Imayama I, Alfano CM, Kong A, et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise interventions effects on quality of life in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ipsen C, Ravesloot C, Arnold N, Seekins T. Working well with a disability: health promotion as a means to employment. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Islam NS, Zanowiak JM, Wyatt LC, et al. A randomized-controlled, pilot intervention on diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyles in the New York City Korean community. J Community Health. 2013;38:1030-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johansen KS, Bjørge B, Hjellset VT, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Råberg M, Wandel M. Changes in food habits and motivation for healthy eating among Pakistani women living in Norway: results from the InnvaDiab-DEPLAN study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:858-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jorna M, Ball K, Salmon J. Effects of a holistic health program on women’s physical activity and mental and spiritual health. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:395-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaholokula JK, Mau MK, Efird JT, et al. A family and community focused lifestyle program prevents weight regain in Pacific Islanders: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:386-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kandula NR, Dave S, De Chavez PJ, et al. Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: the South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study; a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katzer L, Bradshaw AJ, Horwath CC, Gray AR, O’Brien S, Joyce J. Evaluation of a “nondieting” stress reduction program for overweight women: a randomized trial. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:264-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Keyserling TC, Samuel Hodge CD, Jilcott SB, et al. Randomized trial of a clinic-based, community-supported, lifestyle intervention to improve physical activity and diet: the North Carolina enhanced WISEWOMAN project. Preventive Medicine. 2008;46:499-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kimura M, Moriyasu A, Kumagai S, et al. Community-based intervention to improve dietary habits and promote physical activity among older adults: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuller LH, Kriska AM, Kinzel LS, et al. The clinical trial of Women On the Move through Activity and Nutrition (WOMAN) study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:370-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Limm H, Heinmuller M, Gundel H, et al. Effects of a health promotion program based on a train-the-trainer approach on quality of life and mental health of long-term unemployed persons. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:719327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. MacKinnon DP, Elliot DL, Thoemmes F, et al. Long-term effects of a worksite health promotion program for firefighters. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:695-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marshall SJ, Nicaise V, Ji M, et al. Using step cadence goals to increase moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:592-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McGrady A, Brennan J, Lynch D. Effects of wellness programs in family medicine. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McGrady A, Brennan J, Lynch D, Whearty K. A wellness program for first year medical students. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2012;37:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Merrill RM, Aldana SG. Improving overall health status through the CHIP intervention. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Impact of worksite wellness intervention on cardiac risk factors and one-year health care costs. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1389-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Millear P, Liossis P, Shochet IM, Biggs H, Donald M. Being on PAR: outcomes of a pilot trial to improve mental health and wellbeing in the workplace with the Promoting Adult Resilience (PAR) program. Behav Change. 2008;25:215-228. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Olafsdottir AS, Johannsdottir SS, Arngrimsson SA, Johannsson E. Lifestyle intervention at sea changes body composition, metabolic profile and fitness. Public Health. 2012;126:888-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Opdenacker J, Boen F, Coorevits N, Delecluse C. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention and a structured exercise intervention in older adults. Prev Med. 2008;46:518-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Perry CK, Rosenfeld AG, Bennett JA, Potempa K. Heart-to-heart: promoting walking in rural women through motivational interviewing and group support. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Resnick B, Luisi D, Vogel A. Testing the Senior Exercise Self-efficacy Project (SESEP) for use with urban dwelling minority older adults. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25:221-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saadat H, Snow DL, Ottenheimer S, Dai F, Kain ZN. Wellness program for anesthesiology residents: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:1130-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Teri L, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, Buchner DM, Larson EB. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the Seattle Protocol for Activity in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1188-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Umanodan R, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura M, Kitaoka-Higashiguchi K, Kawakami N, Shimazu A. Effects of a worksite stress management training program with six short-hour sessions: a controlled trial among Japanese employees. J Occup Health. 2009;51:294-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Weber MB, Ranjani H, Meyers GC, Mohan V, Narayan KM. A model of translational research for diabetes prevention in low and middle-income countries: the Diabetes Community Lifestyle Improvement Program (D-CLIP) trial. Prim Care Diabetes. 2012;6(1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. In: van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, eds. Handbook of Social Psychological Theories. London, England: Sage; 2011:349-373. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivation Inter-viewing. New York, NY: Guilford; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Myers IB, McCaulley MH. Manual: A Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Brings Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Victorson D, Maletich C, Gutierrez B, et al. Description of a new National Cancer Institute funded randomized controlled trial “REASSURE ME” to support emotion regulation, positive health behaviors, and adherence in a sample of men with prostate cancer on active surveillance and their spouses. Paper presented at: Annual North Central Section Meeting of the American Urological Association; September 7-10, 2016; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]