Abstract

Early home visiting is a vital health promotion strategy that is widely associated with positive outcomes for vulnerable families. To expand access to these services, the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program was established under the Affordable Care Act, and over $2 billion have been distributed from the Health Resources and Services Administration to states, territories, and tribal entities to support funding for early home visiting programs serving pregnant women and families with young children (birth to 5 years of age). As of October 2018, 20 programs met Department of Health and Human Services criteria for evidence of effectiveness and were approved to receive MIECHV funding. However, the same few eligible programs receive MIECHV funding in almost all states, likely due to previously established infrastructure prior to establishment of the MIECHV program. Fully capitalizing on this federal investment will require all state policymakers and bureaucrats to reevaluate services currently offered and systematically and transparently develop a menu of home visiting services that will best match the specific needs of the vulnerable families in their communities. Federal incentives and strategies may also improve states’ abilities to successfully implement a comprehensive and diverse menu of home visiting service options. By offering a menu of home visiting program models with varying levels of service delivery, home visitor education backgrounds, and targeted domains for improvement, state agencies serving children and families have an opportunity to expand their reach of services, improve cost-effectiveness, and promote optimal outcomes for vulnerable families. Nurses and nursing organizations can play a key role in advocating for this approach.

Keywords: health promotion, vulnerable populations, health care reform, maternal–child health services, child health

Exposure to adversity in early childhood can set the stage for poor physical, mental, and emotional health throughout the life span (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Thus, the implementation of policies and programs to prevent early adversity and promote healthy development is essential to the foundation of a productive society. One prevention strategy that has increasingly garnered support among health care providers and state and federal policymakers is early home visiting (Adirim & Supplee, 2013; Garner, 2013). Early home visiting is a service delivery strategy intended to improve health, development, and life course outcomes for children and families (Adirim & Supplee, 2013). In the United States, early home visiting programs typically serve pregnant women and families with children from birth to 5 years of age who are considered vulnerable due to risk factors such as low socioeconomic status or young maternal age (Adirim & Supplee, 2013; Sama-Miller et al., 2018). The aims of early home visiting models vary and may include health promotion, parenting education, or child maltreatment prevention. Home visitors may include parent educators, trained lay community members, nurses, social workers, or peer parents, and regular visits may occur over the course of weeks or years (Sama-Miller et al., 2018). A growing body of evidence suggests that early home visiting can be a cost-effective strategy for improving maternal and child health, promoting cognitive and language development, and preventing child maltreatment and toxic stress (Dalziel & Segal, 2012; Olds et al., 2010; Peacock, Konrad, Watson, Nickel, & Muhajarine, 2013). By improving the capacities of caregivers and families, home visiting programs promote safe, stable, and nurturing environments that are more likely to provide a foundation for healthy development and resilience in children (Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012; Garner, 2013). In the long term, this foundation has the potential to widely benefit many aspects of society, including the health care, education, and employment sectors.

The purpose of this article is to advocate for a paradigm shift in the approach to state funding for early home visiting programs. Although many early home visiting program models are available in the United States (Duffee et al., 2017), state agencies use federal funds for only a small handful of evidence-based programs. Optimal outcomes for vulnerable families will only be achieved if state policymakers are willing to set aside political interests; rethink the economics of early home visiting; and fund diverse program models with varying levels of service delivery, home visitor education backgrounds, and targeted domains for improvement. By offering a menu of home visiting program models, states will (a) expand their reach of services to more diverse target populations, (b) improve outcomes by matching specific interventions with family needs, (c) promote a system of coordinated services for maternal–child health, (d) improve cost-effectiveness, and (e) contribute to valuable research on home visiting effectiveness.

Early Home Visiting in the United States

In a 2011 survey, the Pew Center identified at least 119 home visiting program models across all 50 states (The Pew Center on the States, 2011). These home visiting models vary widely based on target population, home visitor qualifications, mode of service delivery, and targeted domains for improvement. Unlike many European countries where home visiting programs are universally provided to new parents, home visiting programs in the United States are typically developed to target specific high-risk or vulnerable groups (Duffee et al., 2017). One of the original evidenced-based home visiting programs in the United States is the Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP) model, which has demonstrated improved maternal and child outcomes for program participants through randomized controlled trials for over 30 years (Olds, 2006; Thompson, Clark, Howland, & Mueller, 2011).

Federal Funding for Early Home Visiting Programs

In an effort to expand home visiting services and improve life course outcomes for vulnerable children and families, the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program was established under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; Adirim & Supplee, 2013). MIECHV is a federal program administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within the Department of Health and Human Services, in partnership with the Administration for Children and Families (ACF; Adirim & Supplee, 2013). NFP policy staff played a key role in crafting legislation that led to MIECHV funding, advocating for the Department of Health and Human Services to fund only evidence-based home visiting models (NFP, 2011; Thompson et al., 2011). Initially funded at $1.5 billion for 5 years (2010–2014), MIECHV supports state funding of home visiting programs for pregnant women and families with children from birth to 5 years of age (Sama-Miller et al., 2018). In 2018, Congress reauthorized funding for MIECHV at $400 million per year over a 5-year period (HRSA, 2018b). This federal investment in early home visiting represents a substantial commitment toward promoting health equity among vulnerable families and preventing the outcomes associated with early childhood adversity.

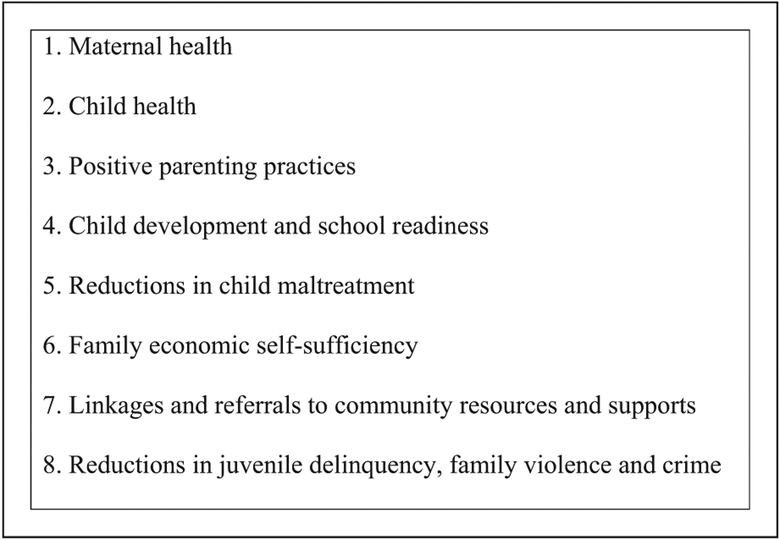

The MIECHV program is innovative in its approach to early childhood investment, as it is one of the first federal policy initiatives to be evidenced based, with funding reserved for only those models that have demonstrated improvement in at least one of the eight designated domains (see Figure 1; Adirim & Supplee, 2013; Sama-Miller et al., 2018). The MIECHV program funding structure is unique, allowing states to choose program models and target families based on the needs of their populations. State agencies apply for federal funds through formula grants and competitive grants. Formula grants are awarded based on the number of children in a state under 5 years of age living below the poverty level, and competitive grants allow states to build infrastructure to support home visiting services or test new innovations within their targeted population (Adirim & Supplee, 2013).

Figure 1.

Eight Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting designated domains for outcome improvement (Sama-Miller et al., 2018).

Agencies responsible for grant management vary from state to state and include departments of public health, human services, and education (HRSA, 2016). Grantees are required to demonstrate measureable improvement in at least four of the six benchmark areas after 3 years of program implementation: (a) improvements in maternal and newborn health, (b) prevention of child maltreatment and reduction of emergency department visits, (c) improvements in school readiness and achievement, (d) reduction in crime or domestic violence, (e) improvements in family economic self-sufficiency, and (f) improvements in the coordination and referrals for other community resources and supports. Grantees who fail to demonstrate improvement receive targeted technical assistance and increased federal monitoring in an effort to improve performance in subsequent years (HRSA, 2016).

Home Visiting Program Models in the United States

The ACA specifies that MIECHV funds be targeted for high-risk populations, including low-income communities; pregnant women under 21 years of age; children with developmental delays; or families with a history of abuse, neglect, or substance abuse (Adirim & Supplee, 2013). To provide guidance for states on home visiting model selection, the ACF Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation conducts an annual systematic review of home visiting research through a project known as Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE). During this review, models are rigorously evaluated for the quality and impact of available research evidence according to each of the eight MIECHV designated domains (see Figure 1). As of the most recent HomVEE review in October 2018, 46 program models were prioritized for evaluation based on the extent of available research evidence, and 20 models were approved for receipt of MIECHV funding (Sama-Miller et al., 2018). However, though the federal process for determining model eligibility is rigorous, the processes by which state agencies evaluate the needs of their communities and subsequently select MIECHV-approved models for implementation are not readily transparent.

Current State Funding for MIECHV Program Models

All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories (Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and Northern Marina Islands) receive funds from the MIECHV program, and states typically fund between one and five home visiting models (M = 2.5 models; HRSA, 2018a). Although 20 program models are currently approved by HomVEE as eligible for MIECHV funding, 4 program models receive funding in the vast majority of states and territories: NFP, Healthy Families America, Parents as Teachers, and Early Head Start-Home Visiting (HRSA, 2018a). As indicated in Table 1, these four programs target similar populations of low-income, pregnant women but differ in terms of home visitor qualifications; mode and length of service delivery; and targeted maternal, child, and family outcomes. These programs are widely disseminated and have a number of well-documented strengths; evidence from the HomVEE review indicates that these programs have demonstrated improvement in many or all of the eight domains (Table 2; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, 2016).

Table 1.

Four Most Commonly Funded Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program Models.

| Program | No. of states/territories | Target population | Home visitor credentials | Mode and length of service delivery | Average annual cost per family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse–Family Partnership | 39 | Low-income pregnant (<28 weeks) women with no previous live births | Baccalaureate prepared registered nurses | Pregnancy—24 months; weekly until 6 weeks of age then every other week until 20 months, then monthly until 24 months | $4,100 (2011 dollars) |

| Healthy Families America | 36 | Prenatal or up to 3 months postnatal; target population selected by local site | Paraprofessionals (74% college graduates or have some college education) | Weekly home visits until 6 months of age; less frequent as indicated until 3–5 years of age | $3,577–$4,473 (2014 dollars) |

| Parents as Teachers | 34 | Eligibility criteria determined by site | Minimum of high school diploma or equivalency certificate and 2 years supervised experience working with young children or parents | Pregnancy to kindergarten entry; at least 12 visits per year, frequency based on family needs; also includes parent education groups | $2,575–$6,000 (2016 dollars) |

| Early Head Start-Home Visiting | 14 | Pregnant women and children under 3 years of age, must be at or below the federal poverty level | Information not available | One visit per week and group socialization activities twice per month; pregnancy or birth to 3 years of age | $9,000–$12,000 (2012 dollars) |

Note. Reported annual costs per most recent HomVEE (2017) data. Additional information received from Olds (2006), Prevent Child Abuse America (2015), Parents as Teachers National Center (2015), and HomVEE (2016).

Table 2.

Favorable Outcomes for Four Most Commonly Funded Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program Models (Sama-Miller et al., 2018).

| Program | Child health | Maternal health | Positive parenting practices | Child development and school readiness | Reductions in child maltreatment | Family economic self-sufficiency | Linkages and referrals | Reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence and crime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse–Family Partnership | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Healthy Families America | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parents as Teachers | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured |

| Early Head Start—Home Visiting | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not measured |

Note. According to HomVEE criteria, favorable outcomes indicate those in which a statistically significant impact has been measured in a direction that is beneficial for children and parents; Not measured indicates that current research evidence has not been collected or does not meet HomVEE standards for the designated domain (HRSA, 2018a).

While 16 other home visiting models are eligible for receipt of MIECHV funding, there is a dramatic disparity in the prevalence of federal funding for these remaining programs. Of these 16 models, 6 receive MIECHV funding in only one or two states/territories and 8 models were not receiving any MIECHV funds at all as of 2018 (HRSA, 2018a).

Compared with the four most commonly funded home visiting models (NFP, Parents as Teachers, Healthy Families American, and Early Head Start Home Visiting), the eight unfunded models represent a more diverse range of services, targeted populations, and home visitor qualifications (see Table 3). For example, the Family Connects program is a universal home visiting program for all families with newborns within a community, regardless of risk or socioeconomic status. Family Connects provides one to three home visits with a registered nurse who screens for potential risk factors and links families with services available in the community, including long-term home visiting programs as necessary. By providing universal services for all families, this model aims to reduce the stigma associated with targeted services while maintaining an ability to identify and intervene with families in need of long-term support (Dodge et al., 2014). In contrast, Minding the Baby® is a home visiting model specifically designed for young, low-income, first-time mothers and provides weekly services by a team of masters-prepared professionals from pregnancy until the child is 2 years of age (Sadler et al., 2013). Minding the Baby® is a tailored intervention that focuses on enhancement of the maternal–child relationship, maternal and child health outcomes, parental reflective functioning, and in-home mental health assessment and treatment for families (Ordway et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013; Slade et al., 2006). Family Connects and Minding the Baby® are offered in multiple communities throughout the United States and represent distinctly different but equally important, approaches to early childhood investment (Family Connects International, 2018; Minding the Baby, 2018). Promoting such diversity in the menu of home visiting services available in each state would provide a valuable opportunity to expand the scope, effectiveness, and efficiency of home visiting services.

Table 3.

Eight Eligible Models Not Currently Receiving Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Funds.

| Program | State where developed | Target population | Home visitor credentials | Mode and length of service delivery | Average cost per family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up Intervention | DE | Caregivers of infants and young children 6- to 24-months-old, including high-risk birth parents, caregivers of children in foster care, kinship care, and adoptive care. | Parent coaches | 10 weekly home visits, approximately 60 minutes each | $2,000 (2016 dollars) |

| Family Connects | NC | Families with newborns ages 2–12 weeks, regardless of income or background | Registered nurses | 1–3RN home visits per family, screens for risk factors and provides referrals and linkages to services as needed | $500–$700 (2016 dollars) per birth |

| Early Intervention Program for Adolescent mothers | CA | Pregnant Latina and African American adolescents | Public health nurses | 17 home visits from midpregnancy until child is 1 year of age | Not available |

| Early Start (New Zealand) | New Zealand | At-risk families with newborns to 5 years of age; three stage eligibility determination process | Screening by community health nurses, home visitor qualifications unspecified | 4 levels of intensity based on family need; may continue to receive services until 5 years of age | $6,750 (New Zealand dollars) per year |

| Healthy Beginnings | Australia | First-time mothers of infants from socially and economically disadvantaged areas | Community nurses | 8 home visits from pregnancy to 24 months, telephone support between visits | $1,309 (Australian dollars) for eight visits over 2 years |

| Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home Visiting Program | Australia | Disadvantaged, pregnant women at risk for adverse maternal or child health and developmental outcomes | Registered nurses | 25 home visits from pregnancy until child is 24 months | $6,000 (2012 dollars) per year |

| Minding the Baby | CT | First-time, low-income mothers aged 14–25 years in second or third trimester of pregnancy | Team consisting of nurse practitioner and licensed clinical social worker | Weekly visits until child is 1 year of age, then every other week until 24 months of age | $10,000 to $13,200 (2016 dollars) per year |

| PALS—Infant | TX | PALS infant curriculum for ages 5–15 months; PALS toddler/preschool curriculum for ages 18 months–4 years | Trained parent coach |

Infant: 11 weekly sessions; toddler/preschool: 13 weekly sessions | $2,500 (2011 dollars) per year |

Note. Reported costs per most recent HomVEE (2017) data. Additional information received from Dodge et al. (2014), Fergusson, Grant, Horwood, and Ridder (2005), Kemp et al. (2011), Koniak-Griffin et al. (2003), Landry, Smith, Swank, and Guttentag (2008), Sadler et al. (2013), and Wen et al. (2012). PALS = Play and Learning Strategies; RN = registered nurse.

Benefits of Funding a Diverse Menu of Home Visiting Services

Enhance Reach and Diversity of Target Populations

In the United States, early home visiting services are generally targeted toward families at high risk for adversity and with limited resources, such as low-income families, young first-time mothers, or families with a history of reported abuse or neglect (Adirim & Supplee, 2013). However, the 2011/2012 National Survey on Children’s Health indicates that 19% of low-income children receive home visiting services, leaving a significant gap in the number of high-risk families that could potentially benefit from early home visiting. According to the survey’s findings, the children most likely to receive services are those (a) in families with annual incomes at 100% of the federal poverty level, (b) receiving public health insurance, (c) born preterm or low birth weight, and (d) with a history of more than two adverse childhood experiences. The study also found that mothers under 20 years of age are 83% more likely to receive home visiting services than older mothers, children without health insurance are 25% less likely to receive home visiting services than children with public health insurance, and families with four or more children are 41% less likely to receive home visiting services than families with one child (Lanier, Maguire-Jack, & Welch, 2015).

Targeting vulnerable populations is an important approach to public health intervention (Frohlich & Potvin, 2008). However, data from the National Survey of Children’s Health indicate that although home visiting services are being appropriately targeted toward vulnerable families, the current approach is also vastly limited (Lanier et al., 2015). NFP, for example, which receives MIECHV funding in 39 states and territories, only provides home visiting services to low-income, first-time mothers who are ideally enrolled prior to 28 weeks gestation (Olds, 2006). While this intervention offers an important service to economically disadvantaged first-time mothers, it excludes other vulnerable families who might also benefit from home visiting services. Specifically, fathers, families with multiple children, and families living at or above the federal poverty level may also significantly benefit from home visiting services, but their needs cannot be met if states only support a limited number of models with inadequate scope. Offering a diverse and expanded menu of home visiting services would improve states’ abilities to reach other disadvantaged groups while still maintaining a targeted approach toward vulnerable families.

Improve Outcomes by Matching Interventions With Family Needs

The heterogeneity of early home visiting services in the United States offers an opportunity to target and tailor home visiting interventions to specific groups who will most benefit from them, but matching families with appropriate services is severely limited in states where home visiting services are homogenous in scope and approach. A recent government-sponsored randomized controlled trial of NFP implementation in the United Kingdom demonstrates the importance of matching interventions with population needs. Because all new mothers in the United Kingdom receive home visits from a community health nurse as a component of usual care, implementation of the more intensive NFP program targeted only mothers less than 20 years of age in a large pragmatic trial (N = 1,645; Robling et al., 2015). However, results indicated that NFP participation did not improve primary study outcomes (prenatal cigarette smoking, rapid subsequent pregnancy, birth weight, and emergency encounters/hospital admissions up to 24 months of age) compared with usual care (Robling et al., 2015), possibly due to an inappropriate fit between the intervention, population, and targeted outcomes (Olds, 2015). In the United States, NFP is specifically geared toward low-income mothers regardless of age, and it is likely that this criterion represents a different type of need than young age alone (Olds, 2006). The U.K. trial also selected two primary outcome measures (birth weight and total emergency/hospital encounters) that NFP does not claim to affect (Olds, 2015; Olds, Hill, O’Brien, Racine, & Moritz, 2003). A better specified target population or evidenced-based choice of outcome measures may have led to more successful implementation of this intensive home visiting service in the United Kingdom.

Appropriate matching of home visiting services with family needs can be accomplished by focusing on each model’s strengths. For example, Family Check-up® is an intervention that integrates a variety of services tailored to family needs, such as home visiting and parent education, and participation is associated with reduced behavioral problems in children and decreased maternal depression (Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). Results from a randomized controlled trial of Minding the Baby® demonstrate that this intervention is particularly effective in enhancing the maternal–child relationship in adolescent mothers (Sadler et al., 2013). Safecare® is a home visiting model designed for families in Child Protective Services for child neglect and is associated with reduced Child Protective Services recidivism. Participation in Safecare® also improves parent–infant interactions in mothers with intellectual disability and is effective and culturally acceptable in American Indian populations (Chaffin, Bard, Bigfoot, & Maher, 2012; Chaffin, Hecht, Bard, Silovsky, & Beasley, 2012; Gaskin, Lutzker, Crimmins, & Robinson, 2012). Matching the needs of individual families with program model strengths, such as those listed above, is likely to lead to greater family engagement in the program and effectiveness in achieving target outcomes.

Appropriate matching of services is especially important for families with mental health needs because supporting maternal and child mental health is foundational to many of the MIECHV domains for outcome improvement (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Three program models with a specific mental health focus include Family Check-up®, Minding the Baby®, and Child FIRST; mental health services have also been integrated into certain NFP sites, such as New Orleans and Cincinnati (Ammerman et al., 2005; Boris et al., 2006). Child FIRST is a home visiting program for children from birth to 5 years of age who screen positive for social–emotional problems or families with high psychosocial risk. Child FIRST clinicians use a relationship-based psychotherapeutic approach to strengthen the parent–child relationship and work closely with the early care or school setting to develop classroom strategies to improve behavior and social–emotional development (Lowell, Carter, Godoy, Paulicin, & Briggs-Gowan, 2011). Innovative mental health-focused models like Child FIRST are essential to addressing the needs of vulnerable families at the highest levels of psychosocial risk.

Improve Coordination of Services in Maternal and Child Health

To optimize the use of a diverse menu of home visiting services, each state will require a coordinated system for screening and referrals which occurs across a continuum from pregnancy though early childhood. According to MIECHV reports, expanded federal funding for home visiting services has led to increased screening for risk factors that are often missed, including developmental delay, intimate partner violence, and maternal depression (HRSA, 2018b). Although challenging to implement, a sophisticated system that allows for coordination among diverse menu options would lead to optimal utilization of services and improved outcomes among vulnerable families in need of various levels of support and could promote early and efficient coordination for many levels of care for parents, children, and families.

Improve Cost-Effectiveness

Economists and other social scientists have documented the economic benefits of investing in early childhood interventions (Doyle, Harmon, Heckman, & Tremblay, 2009; Heckman & Masterov, 2007; Nores & Barnett, 2010). Early childhood investment results in increased earnings, higher educational achievement, and improved physical and mental health, which in turn benefits society through reduced crime, increased tax revenues, and reduced public expenditures (Campbell et al., 2014; Doyle et al., 2009). For example, NFP projects that by 2031, this intervention will have reduced government spending on Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and food stamps by $3.0 billion and prevented the costs associated with 10,000 preterm births, 36,000 incidents of intimate partner violence, 90,000 violent crimes by youth, 36,000 youth arrests, and 594,000 property and public order crimes (Miller, 2015). The economic argument for early childhood investment is especially compelling for children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged environments (Heckman & Masterov, 2007). As children exposed to environments of adversity are at high risk for cognitive, socioemotional, health, and behavioral problems across the life span, the potential for early intervention to mitigate these effects is also high (Garner, 2013; Heckman & Masterov, 2007). Thus, effectively matching programs to specific target populations not only have the potential to utilize resources more effectively, but improving outcomes for the most vulnerable may have important economic implications as well.

Costs of implementing home visiting programs vary widely based on the amount of time and resources used (see Tables 1 and 3), so appropriately matching services with family needs are likely to improve long-term cost-effectiveness (Dalziel & Segal, 2012; McIntosh, Barlow, Davis, & Stewart-Brown, 2009; Olds et al., 2010). For example, in a study comparing outcomes when the NFP model was delivered by paraprofessionals to those when NFP home visitors were nurses, the effect sizes in paraprofessional home visiting programs were approximately half that of those produced by nurses (Olds et al., 2002). In a follow-up study 2 years after program completion, paraprofessional-visited families reported improvements only in maternal mental health, while nurse-visited families reported long-term benefits for both mothers and children in a wide range of health and life course domains (Olds et al., 2004). Thus, while nurses or other professionals may be more costly to hire, they also have the potential to produce more effective results, and thus cost-effectiveness may be optimized by reserving these services for families with the highest level of need. This strategy is also supported by a systematic review of 33 home visiting programs designed to prevent child mal-treatment; the authors found that the most cost-effective programs were comprehensive models that provided a strong match between the program theory, components, and targeted population (Dalziel & Segal, 2012). Thus, although funding only program models with paraprofessional home visitors or less frequent home visits may be less expensive to implement upfront, this may prove less effective over time, particularly for the most vulnerable families. By funding program models at varying levels of intensity and cost, state agencies can distribute resources appropriately and maximize cost-effectiveness over time.

Contribute to Valuable Research on Home Visiting Effectiveness

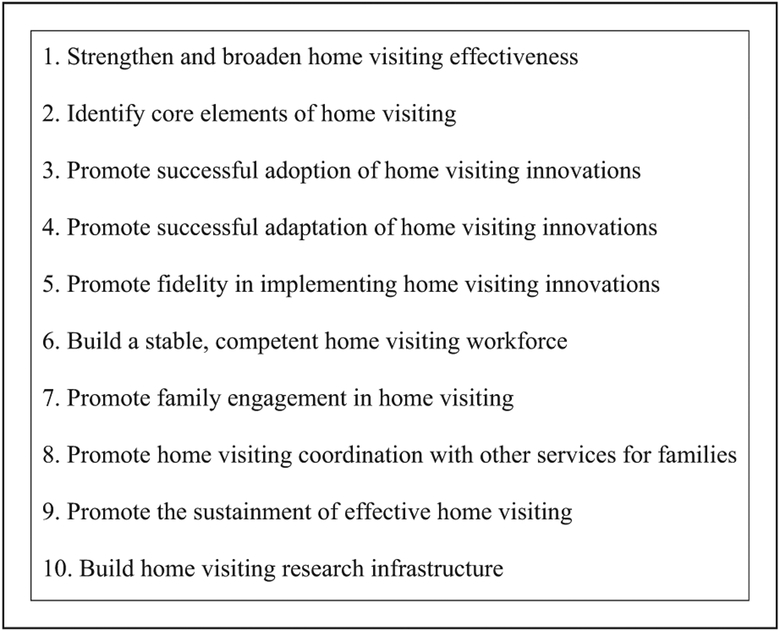

In 2012, the Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative (HARC) was established at Johns Hopkins University with funding from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration to develop a national research agenda to advance the science of home visiting research. Based on priorities suggested by pediatric health care and public health policy stake-holders and public feedback, HARC developed a list of top 10 home visiting research priorities (see Figure 2; HARC, 2018b). HARC’s objectives also include developing a national network of researchers and home visiting stakeholders and advancing the use of innovate methods to address national home visiting priorities (see hvresearch.org for more information).

Figure 2.

Top 10 Home Visiting Research Priorities (HARC, 2018a).

The realization of HARC home visiting research priorities rests on the availability of diverse model implementation in various populations and settings. For example, in comparison to the favorable outcomes demonstrated in almost all domains of the four models most commonly funded by the MIECHV program (see Table 2), the 10 models that do not currently receive MIECHV funding have not measured outcomes in a number of domains, including family economic self-sufficiency; linkages and referrals; and reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime (see Table 4), making it exceedingly difficult to compare outcomes across programs through meta-analyses or other methods. To fill in these research gaps for MIECHV-approved models and other innovative approaches to early home visiting, these programs require a stable funding stream that will allow for longitudinal assessments of family and child outcomes.

Table 4.

Favorable Outcomes for 8 Models not Currently Receiving Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Funds.

| Child health | Maternal health | Positive parenting practices | Child development and school readiness | Reductions in child maltreatment | Family economic self-sufficiency | Linkages and referrals | Reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up Intervention | Yes | NM | Yes | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| Family Connects | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM | NM | NM | Yes | NM |

| Early Intervention Program for Adolescent mothers | Yes | No | No | NM | NM | Yes | NM | NM |

| Early Start (New Zealand) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NM | No |

| Healthy Beginnings | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home Visiting Program | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| Minding the Baby | Yes | Yes | No | NM | No | NM | NM | NM |

| Play and Learning Strategies—Infant | NM | NM | Yes | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM |

Note. According to HomVEE criteria, favorable outcomes indicate those in which a statistically significant impact has been measured in a direction that is beneficial for children and parents. Not measured (NM) indicates that current research evidence has not been collected or does not meet HomVEE standards for the designated domain (HRSA, 2018a); boldface text used to highlight areas in need of further research.

Achieving a Diverse Menu of Home Visiting Services

The MIECHV program represents an unprecedented federal investment in early home visiting. In order for this innovative program to reach its full potential, federal and state funding must be distributed to the full extent of available evidence-based programs. This is a significant challenge, as the federalist model embedded in the MIECHV initiative allows states to select models based on the needs of their population. While this ideally should allow for a conscientious approach to model selection, the homogeneity of MIECHV-funded programs across the United States suggests the opposite. That is, state selection of models is most likely based on the presence of programs with established infrastructure in a given state or the advocacy efforts of widely disseminated models with a depth of available resources. A paradigm shift in states’ approaches to funding for early home visiting will require policymakers to look beyond the four most widely funded home visiting models and consider a variety of models with potential to meet the unique needs of communities within their state.

Implementation of a Paradigm Shift

To successfully develop a comprehensive and diverse menu of home visiting services, policymakers and bureaucrats must consider all available MIECHV-approved programs and be thoughtful and systematic in their approach to identifying needs of their constituents. This will first require the establishment of funding priorities at the state level, including the populations and communities that will be targeted by the selected models. For guidance, ZERO TO THREE has developed an assessment tool for state agencies to evaluate their current home visiting system and prioritize areas for improvement (Schrieber & ZERO TO THREE Policy Center, 2010). Other nonprofit organizations also offer tool kits with recommendations for conducting a home visiting needs assessment at the state level (Johnson-Staub & Schmit, 2012; Mattox, Hunter, Kilburn, & Wiseman, 2013). Once a needs assessment is complete and priorities are established, state agencies should carefully evaluate the target population, home visitor education level, mode of delivery, and targeted outcomes for each model and select programs that will best match population needs. In addition to this systematic process, a transparent approach is required. Clear rationale for selection of models and the families that will benefit in each state will provide valuable information for both policymakers and constituents.

Risk Screening and Coordination of Services

Once a menu of services is selected, another significant challenge will be the development of an effective and valid screening tool for determining family risk and appropriately matching services with eligible families. Given the complexity and fluidity of psychosocial issues that may be experienced by young families, one universal screening tool is unlikely to be useful across communities and populations. Innovative approaches to screening, such as the development of algorithms or shared decision-making models, may be necessary to accurately screen and match families with appropriate services. Determining evidence-based standards for periodic rescreening may also be necessary. However, caution must be used when rescreening families or changing services, and the benefits of doing must be weighed against the cost of disrupting an established home visitor–client relationship.

When matching families with home visiting programs, it is important to avoid pigeonholing families or home visiting models based on a specific risk factor. Home visiting models have various strengths and approaches; families should be evaluated across multiple indicators, including the family’s personal preferences, and receive an individualized referral to find the most appropriate fit. Innovative approaches, such as shared decision-making models or other use of technology, will be instrumental to this process.

In addition to developing evidence-based standards and tools for screening, a sophisticated system for referrals will be required to coordinate provision of services at the state level. Existing programs or infrastructures can be enhanced or adapted to accommodate this task, though additional resources to support additional staff, training, and supervision may be necessary. For example, the home visiting menu can become an integral component of patient centered medical homes, a team-based model designed to provide comprehensive and coordinated primary care services. Within this model, screening and referral to home visiting services can become routine practice during obstetric or pediatric primary care visits with young families (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015). Alternatively, states may choose to conduct screenings and referrals at mental and behavioral health appointments, early childhood education programs, or when providing services such as Special Supplemental Nutrition for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). To coordinate services and evaluate outcomes, some states have established departments that may be prepared to undertake this complex task, such as the Connecticut Office of Early Childhood. Specific strategies for coordinating services are likely to vary widely from state to state, but some type of coordination of funding and resources will be imperative for successful implementation and sustainability of a diverse menu of home visiting services.

Evaluating Cost-Effectiveness and Outcomes

Although the evidence for the economic benefits of investment in early childhood interventions is compelling (Doyle et al., 2009; McIntosh et al., 2009; Miller, 2015), additional research is necessary to determine whether a diverse menu of targeted home visiting services might be more cost-effective. For example, economic risks and benefits to families over time, costs to public and private entities for mobilization of resources, and opportunity costs may preclude state policymakers from funding other early childhood or social services. As the short- and long-term outcomes associated with home visiting interventions continue to be evaluated, so must these important economic questions.

Successful implementation of a diverse menu of early home visiting services will also require ongoing evaluation and reassessment. While the ACA Maternal Infant Early Home Visiting legislation does not require that grantees conduct routine community needs assessments, regular reevaluations will allow policymakers and bureaucrats to identify and address the shifting needs and priorities of vulnerable families within their state. However, caution is required when shifting funds or changing models, as disrupting or terminating current services may be detrimental to communities with MIECHV-funded programs.

In addition to evaluation of community needs, individual program models will require routine evaluation to assess both targeted outcomes and goodness of fit with the families served. However, home visiting models present a particular challenge for program evaluation, as the effectiveness of early childhood interventions may not be fully evident until children reach adolescence or even adulthood. In addition, as home visiting models aim to improve outcomes in a range of complex and interconnected domains (Figure 1), it may be inadequate to evaluate outcomes in one domain without also considering impacts on others. For example, though positive parenting practices and child development may be improved at program completion, long-term impacts may be stymied if family economic self-sufficiency or linkages to community resources are not also improved. Thus, a comprehensive assessment that includes evaluation of both short-term and long-term outcomes in all MIECHV designated domains will be crucial for a complete understanding of a model’s effectiveness within a particular population.

To assess the impacts of MIECHV more broadly, utilizing technology to share data across models and states would also be hugely beneficial at the local, state, and federal levels. Use of large data sets to compare outcomes within and across programs has the potential to contribute valuable research on home visiting effectiveness. However, this will require additional coordination, infrastructure, and standardized assessment tools across all eight MIECHV designated outcome domains (Sama-Miller et al., 2018).

Additional Strategies, Limitations, and Considerations

A paradigm shift in states’ approaches to funding for home visiting services will require effective community, state, and federal advocacy. Incremental steps toward diversification of home visiting models can lay the groundwork for further development of a coordinated system to support multiple models. Aligned with this perspective, the HARC (2018a: 1) has recently advocated for precision home visiting research; following the principles of precision health, this approach “seeks to determine the elements of home visiting that work best for particular families in particular contexts.”

The paradigm shift builds on the tenets established by the ACA and traditional U.S. approaches to home visiting that target specific high-risk or vulnerable groups (Adirim & Supplee, 2013). Alternatively, a case may be made for dedicating funds to a singular program with a goal of universal early home visiting, as is done in some European countries like the United Kingdom (Finello, Terteryan, & Riewerts, 2016). However, given the risks of early childhood adversity and the limited federal and state resources available, the best approach is to target vulnerable populations at highest risk for poor health and developmental outcomes (Garner, 2013; Heckman & Masterov, 2007; Nores & Barnett, 2010). Certain changes at the federal level may help to support state-led initiatives to invest in early home visiting and expand services to vulnerable populations. For example, improved coordination between MIECHV and Medicaid reimbursement processes could increase the number of families with access to home visiting services (Witgert, Giles, & Richardson, 2012). Federal support for the national offices of all MIECHV-approved models will allow the less-disseminated models to establish the systems, infrastructure, and advocacy efforts necessary for implementation in multiple states.

States would also benefit from modification of current regulations that prohibit dual enrollment in MIECHV-funded programs. While this regulation may be seen as an effort to spread MIECHV funds across a greater number of families, allowing lifetime participation in only one MIECHV-funded program prohibits necessary coordination and cooperation among home visiting program models within each state. Removal of this federal regulation will allow families to be referred from one model to another, which may be a better fit, as in the case of newly identified mental health concerns. Allowing families to enroll in more than one program over time could also allow for continuity between services as children age out of one program model and into another.

Finally, state policymakers engaged in maternal–child early infant home visiting programs could identify how the current array of programs is insufficient to meet families’ needs. For example, not all models are equipped to care for pregnant women, despite the evidence that exposure to stress prenatally has profound impacts on neurodevelopment and that inequities in child development stem from this period (Bock, Wainstock, Braun, & Segal, 2015; Walker et al., 2011). Some models may lack the personnel or resources to rapidly expand services and thus may require support at the state or federal level to train additional staff members, coordinate services, and evaluate outcomes. This again highlights the importance of reviewing and assessing MIECHV funding, so that current models can be appropriately supported and new evidence-based models can be approved to meet growing community needs.

Implications for Nursing Policy, Research, and Practice

Nurses can play a critical role in advocating for expanded access to diverse home visiting models on local, state, and national levels. State nursing organizations, in particular, are well poised to understand the needs of families in their communities and effectively advocate for a diverse menu of early home visiting services in their state. National nursing organizations invested in maternal, child, and family health can advocate for necessary infrastructure and funds at the federal level. Nurse researchers with expertise in intervention science are well equipped to answer critical questions regarding program effectiveness and test precision health approaches to home visiting intervention. Finally, by understanding the range of program models available, nurses in primary care, inpatient, and community settings can work to connect vulnerable families with early home visiting programs and advocate for expanded access to diverse home visiting services within their organizations and communities.

Conclusion

Early home visiting represents an important strategy toward promoting health and equity in families at high risk for exposure to adversity. While the federal government has authorized a substantial investment in home visiting services, the potential for long-term success of the MIECHV program will ultimately be hindered by states’ continued selection of homogenous models for receipt of funding. Future approaches to model selection should extend beyond simply choosing models that are currently implemented and instead thoughtfully consider the unique needs of each state population in order to develop a diverse and effective menu of services. Like many interventions and health care delivery models, the strategy advocated for here will require innovative problem-solving and rigorous testing. Despite these challenges, however, evidence suggests that a paradigm shift in states’ approaches to selection and funding of early home visiting programs will ultimately improve outcomes for vulnerable families, strengthen communities, and lead to many societal benefits.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Lois Sadler, Arietta Slade, Lisa Summers, Crista Marchesseault, and Deborah Daro for their thoughtful comments and suggestions in the development of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (F31NR016385 and T32NR008346), the NAPNAP Foundation, the Connecticut Nurses Foundation, the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholars Program, and the Alpha Nu chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International.

Biography

Eileen M. Condon is a postdoctoral fellow at the Yale School of Nursing and a board-certified family nurse practiitoner. Her program of research focuses on promoting strengths and preventing toxic stress among vulnerable, low-income families.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adirim T, & Supplee L (2013). Overview of the federal home visiting program. Pediatrics, 132(Suppl. 2), S59–S64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2015). Defining the PCMH. Retrieved from https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Stevens J, Holleb LJ, Novak AL, & Van Ginkel JB (2005). In-home cognitive-behavior therapy for depression. Best Practices in Mental Health, 1(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Flay BR, Embry DD, & Sandler IN (2012). The critical role of nurturing environments for promoting human well-being. American Psychologist, 67(4), 257–271. doi: 10.1037/a0026796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock J, Wainstock T, Braun K, & Segal M (2015). Stress in utero: Prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biological Psychiatry, 78(5), 315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Larrieu JA, Zeanah PD, Nagle GA, Steier A, & McNeill P (2006). The process and promise of mental health augmentation of nurse home-visiting programs: Data from the Louisiana Nurse–Family Partnership. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 26–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F, Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Pungello E,…, & Pan Y (2014). Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science, 343(6178), 1478–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1248429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Bard D, Bigfoot DS, & Maher EJ (2012). Is a structured, manualized, evidence-based treatment protocol culturally competent and equivalently effective among American Indian parents in child welfare? Child Maltreatment, 17(3), 242–252. doi: 10.1177/1077559512457239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Hecht D, Bard D, Silovsky JF, & Beasley WH (2012). A statewide trial of the SafeCare home-based services model with parents in child protective services. Pediatrics, 129(3), 509–515. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel K, & Segal L (2012). Home visiting programmes for the prevention of child maltreatment: Cost-effectiveness of 33 programmes. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 97(9), 787–798. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Goodman WB, Murphy RA, O’Donnell K, Sato J, & Guptill S (2014). Implementation and randomized controlled trial evaluation of universal postnatal nurse home visiting. American Journal of Public Health, 104(Suppl. 1), S136–S143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle O, Harmon CP, Heckman JJ, & Tremblay RE (2009). Investing in early human development: Timing and economic efficiency. Economics & Human Biology, 7(1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffee JH, Mendelsohn AL, Kuo AA, Legano LA, Earls MF, & Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. (2017). Early childhood home visiting. Pediatrics, 140(3), e20172150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Connects International. (2018). Where we are. Retrieved from http://www.familyconnects.org/other-disse-mination-sites/.

- Fergusson DM, Grant H, Horwood LJ, & Ridder EM (2005). Randomized trial of the early start program of home visitation. Pediatrics, 116(6), e803–e809. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finello KM, Terteryan A, & Riewerts RJ (2016). Home visiting programs: What the primary care clinician should know. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 46(4), 101–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, & Potvin L (2008). Transcending the known in public health practice: The inequality paradox: The population approach and vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health, 98(2), 216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AS (2013). Home visiting and the biology of toxic stress: Opportunities to address early childhood adversity. Pediatrics, 132(Suppl. 2), S65–S73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin EH, Lutzker JR, Crimmins DB, & Robinson L (2012). Using a digital frame and pictorial information to enhance the SafeCare® parent–infant interactions module with a mother with intellectual disabilities: Results of a pilot study. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(2), 187–202. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2012.674871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2016). Demonstrating improvement in the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program: A report to congress. Retrieved from https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/MaternalChildHealthInitiatives/HomeVisiting/pdf/reportcongress-homevisiting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2018a). Home visiting grants & grantees. Retrieved from http://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/homevisiting/grants. [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2018b). Maternal, infant and early childhood home visiting. Retrieved from http://www.mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/homevisiting. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, & Masterov DV (2007). The productivity argument for investing in young children. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 29(3), 446–493. [Google Scholar]

- Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative. (2018a). Introduction to precision home visiting. Retrieved from https://www.hvresearch.org/introduction-to-precision-home-visiting. [Google Scholar]

- Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative. (2018b). Research agenda. Retrieved from https://www.hvresearch.org/precision-home-visiting/research-agenda/. [Google Scholar]

- Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness. (2016). Implementing early head start-home visiting. Retrieved from http://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/Implementation/3/Early-Head-Start-Home-Visiting-EHS-HV-Program-Model-Overview/8. [Google Scholar]

- Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness. (2017). Implementation research. Retrieved from https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/implementations.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson_Staub C, & Schmit S (2012). Home away from home: A toolkit for planning home visiting partnerships with family, friend and neighbor caregivers. Retrieved from http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/files/Home-Away-from-Home.pdf.

- Kemp L, Harris E, McMahon C, Matthey S, Impani GV, Anderson T,…, Zapart S (2011). Child and family outcomes of a long-term nurse home visitation programme: A randomised controlled trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96(6), 533–540. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.196279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D, Verzemnieks IL, Anderson NL, Brecht ML, Lesser J, Kim S,…,Turner-Pluta C (2003). Nurse visitation for adolescent mothers: Two-year infant health and maternal outcomes. Nursing Research, 52(2), 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, & Guttentag C(2008). A responsive parenting intervention: The optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1335–1353. doi: 10.1037/a0013030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, & Welch H (2015). A nationally representative study of early childhood home visiting service use in the US. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(10), 2147–2158. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell DI, Carter AS, Godoy L, Paulicin B, & Briggs-Gowan MJ (2011). A randomized controlled trial of child FIRST: A comprehensive home-based intervention translating research into early childhood practice. Child Development, 82(1), 193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox T, Hunter S, Kilburn R, & Wiseman S (2013). Getting to outcomes for home visiting: How to plan, implement, and evaluate a program in your community to support parents and their young children. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/tools/TL100/TL114/RAND_TL114.pdf.

- McIntosh E, Barlow J, Davis H, & Stewart-Brown S(2009). Economic evaluation of an intensive home visiting programme for vulnerable families: A cost-effectiveness analysis of a public health intervention. Journal of Public Health, 31(3), 423–433. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR (2015). Projected outcomes of nurse-family partnership home visitation during 1996–2013, USA. Prevention Science, 16(6), 765–777. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0572-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minding the Baby. (2018). Child Study Center: Community partnerships. Retrieved from https://medicine.yale.edu/childstudy/communitypartnerships/mtb/.

- Nores M, & Barnett WS (2010). Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) investing in the very young. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse–Family Partnership. (2011). Securing support to serve greater needs. Retrieved from http://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/public-policy/. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. (2016, January). Home visiting programs: Reviewing the evidence of effectiveness (No. 2015–85a). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL (2006). The Nurse–Family Partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 5–25. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL (2015). Building evidence to improve maternal and child health. The Lancet, 387(10014), 105–107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Hill PL, O’Brien R, Racine D, & Moritz P (2003). Taking preventive intervention to scale: The nurse-family partnership. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10(4), 278–290. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80046-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Kitzman HJ, Cole RE, Hanks CA, Arcoleo KJ, Anson EA,…,.Stevenson AJ (2010).Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on maternal life course and government spending: Follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 419–424. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, O’Brien R, Luckey DW, Pettitt LM, Henderson CR Jr., …, Talmi A (2002). Home visitingby paraprofessionals and by nurses: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 110(3), 486–496. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng RK, …, Henderson CR Jr. (2004).Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: Age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 114(6), 1560–1568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Dixon J, Close N, Mayes L, & Slade A (2014). Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(1), 3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parents as Teachers National Center. (2015). Evidence Based Model. Retrieved from http://www.parentsasteachers.org/evidence-based-model/.

- Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, Nickel D, & Muhajarine N (2013). Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevent Child Abuse America. (2015). Healthy families America. Retrieved from http://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org/home/index.shtml.

- Robling M, Bekkers M, Bell K, Butler C, Cannings-John R, Channon S, …, Torgerson D (2015). Effectiveness of a nurse-led intensive home-visitation programme for first-time teenage mothers (building blocks): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 387(10014), 146–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00392-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, Webb DL, Simpson T, Fennie K, …, & Mayes LC (2013). Minding the baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home-visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(5), 391–405. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sama-Miller E, Akers L, Mraz-Esposito A, Zukiewicz M, Avellar S, Paulsell D, …, & Del Grosso P (2018). Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness review: Executive summary. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration of Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schrieber L, & ZERO TO THREE Policy Center. (2010). Key components of a successful early childhood home visitation system: A self-assessment tool for states. Retrieved from http://www.zerotothree.org/public-policy/webinars-conference-calls/home-visitation-tool-june-16-2010.pdf.

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, & Gardner F (2009). Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, …,Wegner LM (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Sadler L, de Dios-Kenn C, Webb D, Currier-Ezepchick J, & Mayes L (2006). Minding the baby: A reflective parenting program. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pew Center on the States. (2011). States and the new federal home visiting initiative: An assessment from the starting line. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DK, Clark MJ, Howland LC, & Mueller M (2011). The patient protection and affordable care act of 2010 (PL 111–148): An analysis of maternal–child health home visitation. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice, 12(3), 175–185. doi: 10.1177/1527154411424616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Wachs TD, Grantham-McGregor S, Black MM, Nelson CA, Huffman SL,…, Lozoff B (2011).Inequality in early childhood: Risk and protective factors for early child development. The Lancet, 378(9799), 1325–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle K, & Flood VM (2012). Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children’s BMI at age 2: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Online), 344(7865), e3732doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witgert K, Giles B, & Richardson A (2012). Medicaid financing of early childhood home visiting programs: Options, opportunities, and challenges. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States and the National Academy for State Healthy Policy. [Google Scholar]