Significance

Hydrolysis of GTP leads to remodeling of dynamin helical collars and severing of the underlying membrane neck—a critical step in vesicle endocytosis. We use mathematical modeling to explore the mechanisms that regulate oligomer deformation. We find that orientation of dynamin’s pleckstrin homology domain relative to the membrane introduces tilt strain. Relaxation of this strain requires departure of the oligomer from its intrinsic helical shape. Nonuniform accumulation of strain along the length of the dynamin chain results in partial oligomer fragmentation. The results of our model are corroborated experimentally by atomic force microscopy measurements. Our analysis leads to a definition of the tilted helix: a surface curve that maintains a fixed angle between the curve normal and the surface normal.

Keywords: dynamin, lipid membrane, protein oligomerization, tilt

Abstract

Dynamin proteins assemble into characteristic helical structures around necks of clathrin-coated membrane buds. Hydrolysis of dynamin-bound GTP results in both fission of the membrane neck and partial disruption of the dynamin oligomer. Imaging by atomic force microscopy reveals that, on GTP hydrolysis, dynamin oligomers undergo a dynamic remodeling and lose their distinctive helical shape. While breakup of the dynamin helix is a critical stage in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the mechanism for this remodeling of the oligomer has not been resolved. In this paper, we formulate an analytical, elasticity-based model for the reshaping and disassembly of the dynamin scaffold. We predict that the shape of the oligomer is modulated by the orientation of dynamin’s pleckstrin homology (PH) domain relative to the underlying membrane. Our results indicate that tilt of the PH domain drives deformation and fragmentation of the oligomer, in agreement with experimental observations. This model motivated the introduction of the tilted helix: a curve that maintains a fixed angle between its normal and the normal of the embedding surface. Our findings highlight the importance of tilt as a key regulator of size and morphology of membrane-bound oligomers.

The helix is a pervasive geometrical motif of soluble macromolecules, from the renowned double helix of DNA to the helical structures of cytoskeletal filaments. Helices may appear in the superstructures of membrane-bound proteins, a notable example of which is dynamin: an essential protein for the internalization of endocytic vesicles (1). Dimeric subunits of dynamin assemble into a helical structure around the tubular necks of preexisting clathrin-coated membrane buds (2, 3). After a sufficiently long helix has assembled, hydrolysis of GTP by dynamin leads to scission of the membrane neck followed by disassembly of the oligomer (4–6). The assembly and subsequent breakup of the dynamin helix are required stages to complete vesicle endocytosis, a key process of nutrient uptake into the cell, as well as recycling of lipids and proteins from the plasma membrane (7).

Polymerized dynamin forms helical structures in solution, indicating an intrinsic torsion as well as intrinsic curvature of the oligomer chain. Both the torsion and the curvature of the helix have been found to vary with the nucleotide binding state of dynamin; nucleotide-free dynamin forms helices with an inner radius of 10 nm and a pitch of 10 nm (3), while GTP analogs mimicking intermediate stages of hydrolysis result in narrower helices with a larger pitch (8, 9). Although dynamin is a GTPase, it can induce curvature in a lipid membrane in a nucleotide-independent manner: the rigid scaffolds formed by dynamin oligomerization wrap around the membrane and impose on it a tubular shape (3). Nevertheless, dynamin’s membrane fission activity requires input of chemical energy in the form of GTP (10–13). Cycles of GTP hydrolysis in dynamin oligomers have the effect of constricting the membrane neck, consistent with dynamin’s role in promoting fission; yet, the mechanics of this process remain unclear (1, 10, 14–19). The most constricted state of dynamin, observed for a transition state-defective mutant, is associated with apparent tilting of the membrane binding pleckstrin homology (PH) domains (9). In recent years, several structural and theoretical models have proposed that tilting of the PH domains promotes membrane fission by applying torque to the lipid bilayer and therefore, plays a key role in the membrane fission function of dynamin (20–22). Additionally, evidence, such as decrease in the fluorescence of labeled dynamin scaffolds (11), variations in the conductance of dynamin-coated tubes (12), and clustering of dynamin–amphiphysin complexes (23), suggests that GTP hydrolysis results in a partial breakup of the dynamin helix, indicating that the equilibrium length of the constricted oligomer is reduced (24).

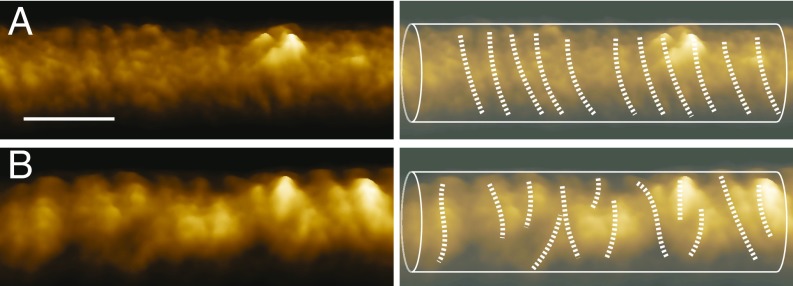

Recently, high-speed atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been utilized to characterize the morphology of the membrane–dynamin system (23, 25). The high spatial and temporal resolutions of these measurements have revealed that GTP hydrolysis results in a dynamic alteration of the oligomer’s shape (25). After GTP addition, the structure of the dynamin oligomers transforms from a long and regular helix to a configuration with nonuniform pitch (Fig. 1). These studies have provided important insights, but the processes that govern the remodeling of the dynamin–membrane system are not fully resolved. Several key questions remain open. How is the chemical energy released by GTP hydrolysis converted to mechanical work of constriction and fission of the membrane? Why does GTP hydrolysis result in a nonhelical shape? Finally, what drives disassembly of the oligomer? The problems of neck constriction and membrane fission have been the subject of extensive theoretical and experimental efforts (1, 10, 14–19, 26–28) and will not be discussed here. In this study, we examine the cause for deviation of the dynamin oligomer from a helical shape and the mechanisms for oligomer fragmentation. As we show below, helical deformation and oligomer fragmentation are inherently connected.

Fig. 1.

Remodeling of the dynamin helical oligomer after GTP hydrolysis. (A, Left) AFM imaging of dynamin on DOPS tubules in the absence of GTP. (A, Right) Tracing of the dynamin rungs from the AFM image in A, Left. (B) Same as A after addition of GTP. (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

Outline of the Approach

We present an elasticity-based theory for the equilibrium shapes of dynamin oligomers and for their remodeling on GTP hydrolysis. Toward this end, we enumerate the various energetic costs that are associated with deformation of the oligomer and the lipid membrane away from their intrinsic shapes. An essential feature of our model is to associate the angle of incidence at which the PH domain of dynamin binds to the membrane surface with a tilt energy term, thereby accounting for the anisotropy of the interaction between the oligomer and the membrane. We hypothesize that GTPase activity in the dynamin oligomer results in tilting of PH domains relative to their relaxed orientations. We show that resistance of the protein–membrane system to PH tilt promotes deviation from the characteristic helical shape of dynamin filaments: to reorient the PH arms to their preferred angle with the membrane surface, the entire shape of the oligomer chain must deform. We demonstrate that the elastic strains associated with such deformations lead to instability of the oligomer beyond a critical size.

Model

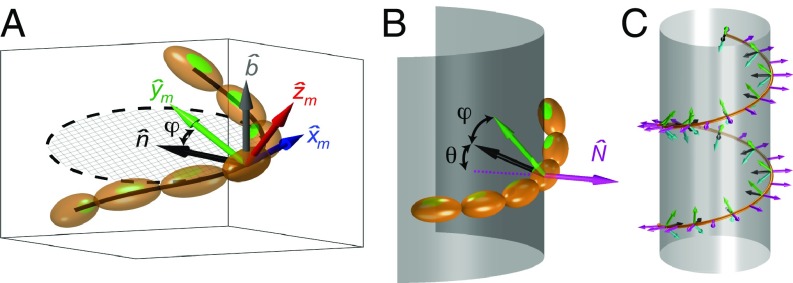

A dynamin oligomer is composed of a linear chain of twofold symmetric dimers. The configuration of the chain may be represented in the continuum limit by a space curve that traces the chain. To describe the full three-dimensional (3D) shape of such an oligomer, we define the moving material frame, , which tracks the orientations of the dimers at each point along the representative curve. We choose the direction to point toward the next dimer in the chain, is along the orientation of the membrane binding domains in the nucleotide-free state (normal to ), and completes the orthonormal set (Fig. 2A). While physical deformations of the oligomer are defined in this material frame, it is convenient to describe the chain in terms of curvature and torsion of the representative curve by using the Frenet frame. The Frenet frame, , is defined by the local tangent, normal, and binormal directions as shown in Fig. 2A. The tangent direction coincides with our definition of , but in general, the curve’s normal and binormal directions can deviate from our choice of and . The transformation between the material and Frenet frames consists of a rotation about by an angle . If the oligomer has a preferred axis of bending, approaches a constant value (SI Appendix has details). In this case, the energy per unit length associated with deforming the chain is composed of bending and twisting contributions:

| [1] |

where and are the rigidities representing resistance of the chain for deformation away from its intrinsic curvature, , and torsion, .

Fig. 2.

Frames of reference. (A) Illustration of the material and Frenet frames for an oligomer chain. The blue arrow points in the tangent direction, common for both frames . The green arrow points in the direction of the membrane binding domain , and the red arrow completes the orthonormal set . The black and gray arrows point in the direction of the Frenet principal normal and binormal , respectively. (B) Illustration of an oligomer chain lying on a membrane surface. The arrows point in the directions of the surface normal (magenta), the Frenet principal normal (black), and the membrane binding domain (green). The two angles comprising the effective tilt angle, (Frenet–Material) and (Frenet–Darboux), are also depicted. (C) Illustration of possible orientation directions of membrane binding domains on an apolar helical oligomer. Membrane binding domains may tilt either up or down, represented by green and cyan arrows, respectively. Untilted domains coincide with the curve normal and are represented by black arrows; the surface normal is shown in magenta.

Next, we consider the geometry of the interaction between the PH domains of the oligomer and the membrane surface. Since the dynamin oligomer adheres to the lipid bilayer, we choose the representative curve of the oligomer to be the membrane–protein contact line. In general, a membrane binding domain of the protein adheres to the bilayer at some angle of incidence. Tilting of this domain away from the membrane normal constrains the surrounding lipid molecules to tilt their orientations correspondingly. Alternatively, rather than inducing a tilt of the lipids, the membrane binding domain may deform from its relaxed orientation to penetrate the bilayer at a right angle. We, therefore, consider tilt as a property of the combined protein–lipid system, taking into account both deformation of the protein and the effect on surrounding lipids. We define the tilt strain as the angle between the orientation of the membrane binding domains and the surface normal, . This tilt angle may be broken down to two contributions: , where is the angle between the curve normal, , and surface normal, (Fig. 2B). The angle has the geometrical significance of representing the transformation between the Frenet frame of the curve, introduced above, and the Darboux frame, a moving frame that is convenient for representation of surface-embedded curves (SI Appendix). In the nucleotide-free state, the relaxed orientations of the PH domains coincide with the curve normal, , while the normal to a helical curve is parallel to the normal of a tubular membrane surface, , resulting in a zero tilt strain. Structural data of a transition state-defective dynamin mutant reveal that one PH domain in each dimer tilts by 45°, while the other retains its orientation parallel to (9). Whereas the tilt angle is predominantly in the plane, we consider only the tilt component due to a rotation of the PH domain about the local chain tangent, , since the tilt component that lies outside the plane cannot be relaxed by any deformation of the chain. The direction of PH tilt varies in different dimers along the oligomer (9). Importantly, the dynamin oligomer has no overall preferred tilt direction (Fig. 2C). While the different tilt preferences may seem to cancel out, the tilt strain in a dynamin oligomer with a helical morphology does not vanish. Rather, tilt strain due to contributions from both “up”- and “down”-tilted PH domains will be accumulated. We represent the twofold tilt symmetry of the dynamin chain by a tilt energy density that has degenerate minima at both negative and positive tilt angles:

| [2] |

Here, represents the combined tilt preference of both tilted and untilted PH domains in each dimer along the oligomer. Since the relative contributions of each of the PH arms to are unknown, we consider possible values ranging from 0° to 45°. We take 20° as a representative value of this range, as is expected to fall well below the upper limit. We define as the effective tilt modulus of the protein–lipid system. According to theoretical estimates, lipid bilayers are quite resistant to tilting deformation, with a bilayer tilt modulus of (29, 30). For and a characteristic length of (the pitch of the dynamin helix), the value arising from bilayer resistance is of the order . However, in order for the PH domains to apply a sufficient torque to deform the membrane (20, 21), the tilt rigidity should be at least .

For tension-free systems, the energetic contribution of the lipid membrane to the system is the cost of membrane bending deformation, expressed by the Helfrich Hamiltonian (31). We assume that the polymerization process proceeds slowly enough for the protein-to-lipid area ratio to remain constant. Consequently, for a given protein area coverage, , the elastic membrane bending energy per unit length of the oligomer is given by

| [3] |

where is the width of the oligomer chain (8), is the bilayer bending rigidity (32), is the total curvature of the membrane surface, and is its spontaneous curvature. Lipid bilayer composed of symmetrical leaflets has a zero spontaneous curvature, whereas shallow insertions by auxiliary BAR domain proteins can disrupt the bilayer symmetry and induce an intrinsic curvature to the membrane (33). While we focus on tubular membrane geometries, in general, the membrane may adopt shapes with nonuniform curvature (34). Such deviations are considered in SI Appendix but do not qualitatively alter our findings.

Finally, the free energy released by incorporation of subunits to the oligomer chain is represented in the continuum limit by an energy length density, . This term includes the energy released by forming interdimer bonds and binding energy with the membrane as well as the entropic cost of joining free subunits to the aggregate. The concluding energetic component of the system is, therefore, .

An oligomer will continue to grow by incorporation of new subunits as long as the free energy released by polymerization exceeds the elastic cost of increasing the chain length. To determine the equilibrium length of the chain, we first find the system morphology that minimizes the total energy for a given length, :

| [4] |

where the minimization is performed over the parameters describing the shape of the curve (see below). The equilibrium length, , then satisfies . Our procedure in the following will be to find the optimal geometry for different intrinsic properties of the oligomer and define the conditions for attaining an equilibrium length in each case.

Results

The Tilted Helix Curve.

A regular (circular) helix is unique not only in having constant curvature and torsion but also, in that the Frenet normal coincides with the surface normal of the cylinder on which it lies; for all helices, . A regular helix may be found so that the curvature and torsion match their intrinsic values, and , but a nonvanishing will result in a strain that cannot be eliminated by any choice of regular helix parameters. It follows that the regular helix is the preferred oligomer geometry when the bending and twisting rigidities are large compared with the tilt rigidity but not when the tilt rigidity dominates. For cases where , a curve with a constant tilt, , is energetically most advantageous. We search for constant tilt curves having the cylindrical parameterization

| [5] |

where is the cylinder radius and is the azimuthal coordinate. We determine the local tilt of the chain, , by noting that the tilt angle of a curve embedded on a surface can be expressed via its geodesic curvature, :

| [6] |

where the geodesic curvature of cylindrical curves can be obtained by the unwrapping of the cylinder to a plane (SI Appendix has details).

To find , we utilize Eq. 6 together with the geodesic and normal curvatures of the cylindrical parameterization of Eq. 5:

| [7] |

The task of finding a constant tilt curve is thereby reduced to solving a straightforward, nonlinear, differential equation. Solving Eqs. 6 and 7 while setting results in the compact parametric form:

| [8] |

where . We refer to the curve given by Eqs. 5 and 8 as a tilted helix. In Fig. 3A, we illustrate portions of the tilted helix for several values of . Most prominently, the pitch of the tilted helix is variable, with a minimum at the point. Away from the origin, the pitch grows along the coordinate, and the curve ultimately approaches a straight line parallel to the tube axis. Near the origin, the curve approaches a circle for any . As , the pitch approaches 0 (i.e., the curve becomes a circle). For negative , the tilted helix flips its polarity but is otherwise equivalent to the positive case. The curvature and torsion of the tilted helix are given by

| [9] |

From the expression for the torsion, it is readily seen that the tilted helix may adopt right- or left-handed chirality, where the handedness changes sign at (Fig. 3A depicts the right-handed portions of the curves, and more details are in SI Appendix). As shown in Fig. 3 B and C, the curvature and torsion peak at different locations along the curve, but both decay exponentially at long chain lengths.

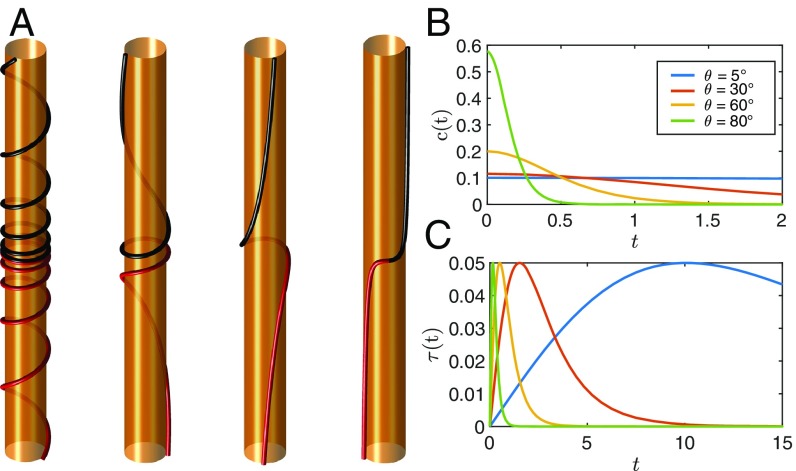

Fig. 3.

The tilted helix curve. (A) An illustration of the tilted helix of Eq. 8 for tube radius of 10 nm and several values of . The portions of the curves with right-handed chirality are shown. Black and red curves represent the different tilted helix solutions for and , respectively. (B) The curvature and (C) the torsion along two cycles of the tilted helix for several values.

Following the same approach, curves of constant tilt may be found for other biologically relevant surface geometries. In SI Appendix, we derive the analog of the tilted helix for a catenoid, the expected shape of a membrane neck with vanishing mean curvature (35). We find that the curvature and torsion of a catenoidal constant tilt curve vary in a similar way to those of the tilted helix (SI Appendix).

Equilibrium Shape of the Oligomer.

From the above findings, the mechanism for dynamin disassembly may be readily understood to be a consequence of a tilt of dynamin’s PH domain. At zero tilt, the optimal morphology of a dynamin oligomer is a regular helix, for which the elastic energy of the chain grows linearly with its length. If the rate of elastic energy buildup is slower than the rate of release of binding energy, , polymerization can proceed indefinitely. Tilting of the PH domains in a helical oligomer will result in a significant tilt strain. If the oligomer would retain its helical shape, the tilt energy density can exceed the polymerization energy and therefore, result in disassembly of the oligomer. However, conformational changes in dynamin that tilt the PH domains will make a helical oligomer shape energetically unfavorable and a tilted helix oligomer preferable. For such a morphology, the decay of torsion and curvature along the oligomer will lead to nonlinear accumulation of elastic strain. The rate of elastic energy accretion will eventually exceed the polymerization energy density, , at some critical length, , leading to break up of the oligomer.

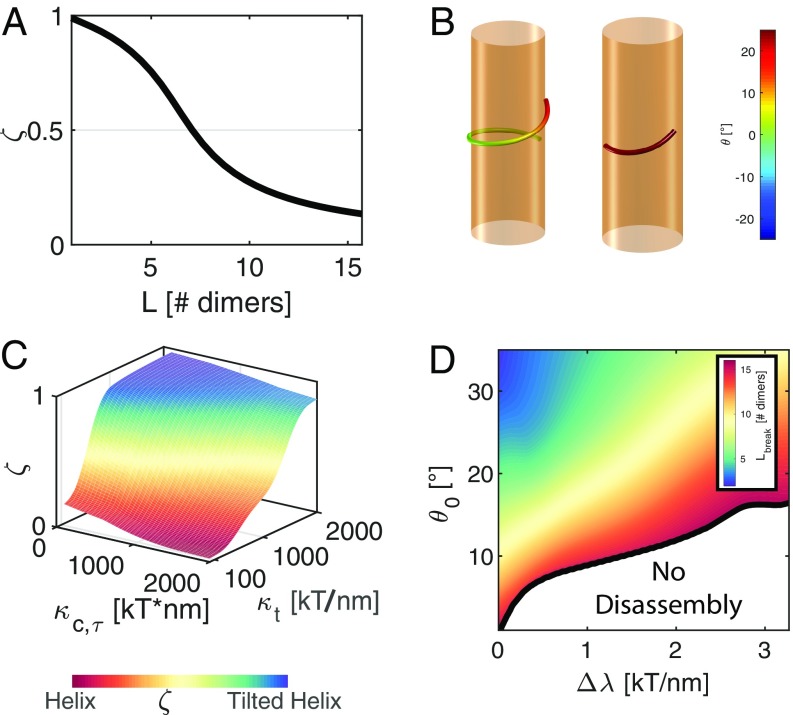

While the tilted helix is the optimal shape in the limit of infinite tilt rigidity, the actual rigidities of the dynamin oligomer are unknown. To explore the general solution of the dynamin oligomer shape, we define a hybrid parameterization that includes both the tilted helix and a regular helix as distinct limits. We characterize the intermediate curves by the normalized average tilt, , ranging from zero to one, corresponding to a pure regular helix and a pure tilted helix, respectively. In such hybrid curves, curvature and torsion as well as tilt change along the oligomer length. The optimal shape is determined by minimization of the total energy over the hybrid curve’s parameters (SI Appendix). We find that, as the chain length increases, the optimal shape approaches a regular helix, where the various strain contributions do not vary greatly along the chain (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, we find that the tilt angle throughout most of the oligomer is close to zero, with a small region of substantial tilt localized at the end of the oligomer chain. These findings indicate that only free ends of long oligomers will rotate relative to the underlying membrane. For shorter oligomers, the tilt strain may be relaxed without incurring prohibitively large bending and twist costs (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, for short oligomers, we find that the optimal shape can include regions with left-handed chirality. This result may be understood by noting that the curve’s torsion can be expressed as , where is the geodesic torsion proportional to the angle that the curve makes with the horizontal plane to the tube. In regions where the derivative of the tilt angle, , is large, the geodesic torsion may assume negative values, while the torsion remains positive. As expected, we find that the optimal shape may adopt either positive or negative tilt angles, since the system is insensitive to the sign of the tilt.

Fig. 4.

The effect of tilting of the PH domain on oligomer shape and size. (A) The shape of a dynamin oligomer characterized by the average tilt, , as a function of the oligomer length. (B) Optimal shape and tilt of oligomers with lengths 10 nm (Right) and 30 nm (Left). Spontaneous curvature and twist values are taken from the constricted configuration of dynamin helix, and (SI Appendix), intrinsic tilt of , and a membrane ground state corresponding to a preconstriction tubule diameter of 20 nm (39). (C) Rigidities phase diagram for the optimal shape of a 14-dimer-long dynamin oligomer on tilting of the PH domain by . (D) The equilibrium length of a dynamin oligomer as a function of the tilt angle, , and , the change in polymerization energy between the tilted and nontilted states. We use the rigidity values: and . In A–D, oligomer shapes represented by the hybrid curve parameterization (SI Appendix).

To characterize the effect of the different elastic rigidities, we calculate the optimal shape for a dynamin oligomer of a physiologically functional length, corresponding to 14 dynamin dimers (5, 6). The resulting range of calculated morphologies is summarized in Fig. 4C. When the tilt resistance is small compared with the bending and twisting resistance of the system, the optimal shape approaches a regular helix. For higher tilt rigidities, the calculated shape represents a compromise between the bend, twist, and tilt strains. As expected, when tilt rigidities are large compared with bending and twist rigidities, we find that the optimal solution approaches the tilted helix curve.

The morphologies described in Fig. 4 A–C are those for which the total elastic energy is minimal yet may be unstable against depolymerization. For each length, a minimal polymerization energy density, , is required to stabilize the oligomer. Since GTPase activity in dynamin results in a constriction of the membrane neck in addition to the putative reorientation of the PH domains, we seek to characterize the contribution of tilting alone to . We, therefore, define as the difference in the required polymerization energy between a state with an intrinsic tilt, , and a ground state with zero tilt. After reorientation of the PH domains, the oligomer will be stable if the available polymerization free energy exceeds the energetic cost due to tilt, . For each combination of and , we may, therefore, find the posthydrolysis equilibrium length of the oligomer, , as shown in Fig. 4D. Low values indicate that the bulk of chemical energy is converted to the mechanical work of constricting the membrane (24). In this limit, we find that even small tilt angles result in a short equilibrium length, corresponding to a disassembly of the dynamin oligomer. As increases, more of the polymerization energy is available to stabilize the oligomer. We consider values of up to the experimentally estimated polymerization energy of ∼5 kT per dimer (36) or ∼2 kT/nm in terms of our representative curve (SI Appendix). For physiologically feasible values, a tilt angle of leads to a partial breakup of the chain into short fragments of 5–10 dimers.

Whereas above, we have considered an intrinsic tilt that is induced uniformly throughout the length of the dynamin oligomer, the tilt of PH domains may be a result of local interactions of GTPase domains between neighboring rungs (20, 37). In SI Appendix, we examine a scenario in which PH tilt is induced only in overlapping regions of an oligomer chain and find that, in such a case as well, PH tilt results in deformation of the chain and can lead to breakup of the oligomer.

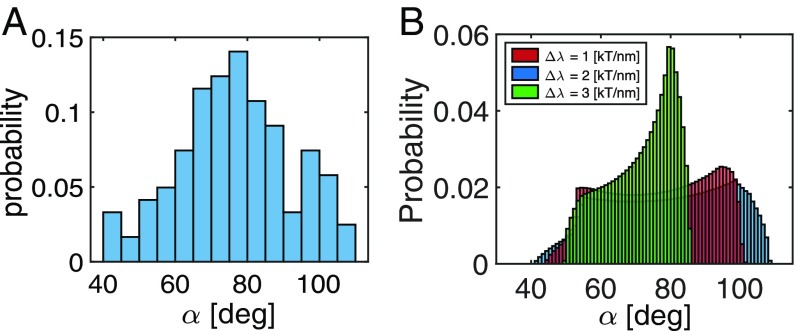

Distribution of Turn Angles.

Since instability of a dynamin oligomer is coupled to its deformation from a regular helix, direct visualization of the morphology is difficult. By utilizing the high temporal and spatial dynamics of AFM measurements, the distribution of dynamin turn angles, both pre- and posthydrolysis, may be quantified (25). Before GTP addition to the system, dynamin oligomers tubulate 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DOPS) membrane liposomes and cover them in a continuous helical oligomer coat. The turn angle of the filament is defined as the angle between the rungs of these structures and the tubule axis. From AFM imaging, we find , while from structural data, the turn angle of the nonconstricted dynamin state is (3). GTP addition to the system results in both constriction of the tubule and a divergence of the measured turn angles. After GTP addition, the average turn angle decreases to 75°, while the distribution of turn angles along the tubule becomes significantly wider, with SD of ∼16° (Fig. 5A), suggesting a nonhelical configuration of the oligomer. We may further compare these results with our model predictions by calculating the probability distribution of turn angles for a thermodynamic ensemble of oligomer fragments with different lengths. The probability to observe a given turn angle, , is then given by

| [10] |

where is the probability to observe along an equilibrium configuration of length and total elastic energy, (SI Appendix has details). The predicted distribution is shown in Fig. 5B for different values. The results recapture the essential features of the experimental system: a wide spread of expected turn angles ranging from to . It is interesting to note that, in agreement with experiments, we find a finite probability for turn angles that exceed (i.e., a switch to left-handed chirality is energetically permissible for short fragments of the oligomer).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of turn angles in posthydrolysis dynamin oligomer. Turn angle is defined as the angle between a rung of the oligomer and the tubule axis. (A) Measurements from AFM images. (B) Predicted distribution of turn angles. Calculations performed for a spontaneous tilt angle, , and rigidity values, and .

Discussion

Coarse-grained theoretical models of lipidic and protein systems, at various levels of detail, have been shown as particularly useful for studying the interplay between morphology and physical forces. Insights and predictions have been gleaned from the most abstract representation of the dynamin collar system: the lipid bilayer modeled as a 2D surface and the polymer chain as 1D space curve. In this work, we expand this picture to account for the orientation-dependent interaction of dynamin with the membrane via the PH domain.

Consideration of the anisotropic nature of the protein–membrane interaction has led to the definition of constant tilt curves: surface curves that maintain a prescribed angle of rotation between their Darboux and Frenet frames. For cylindrical surfaces, we have found a parametric solution to the natural equations of the curve, which we have termed the tilted helix. Multiple classical geometries, such as helices, helicoids, and catenoids, have been predicted and found in subcellular systems (35, 38, 39); remarkably, in this case, the characterization of the tilted helix itself has been motivated by the underlying biology.

The presented theory underlines a pivotal role of tilt in regulating dynamin oligomerization. Our results show that reorientation of the PH domains induces substantial tilt strain in the membrane–dynamin system. This strain may be partially relieved by deforming the characteristic helical shape of dynamin filaments. We find that a constricted dynamin oligomer with tilted PH domains is only stable at relatively short lengths. This result, therefore, represents a solution for the puzzle of dynamin disassembly on GTP hydrolysis: breakup of the oligomer may follow as a mechanical consequence to the PH tilt.

While tilt represents an added level of detail for modeling the dynamin collar, not all of the experimental features of the system are incorporated into the model. Interactions between adjacent rungs of the dynamin oligomer have been proposed to provide the driving force for membrane constriction and for deflection of the PH domains (10, 15, 37). Although interrung contacts that constrict the tube diameter would affect the shape of the oligomer, they are, in fact, insufficient to stabilize the purely helical shape of the oligomer, as a considerable tilt strain would develop in this configuration, promoting depolymerization. Such interactions are, therefore, not expected to change our results qualitatively. Furthermore, it has been suggested that additional hydrophobic regions in the PH domain insert into the outer membrane monolayer when tilted (28). This is expected to increase the effective resistance to tilt and therefore, enhance the described effect of oligomer breakup.

The foremost remaining challenge in deciphering the process of dynamin-mediated endocytosis is a mechanistic understanding of the fission of the membrane neck. Whereas previous analytical models have had limited success in uncovering dynamin’s fission mechanism, recent models that consider the torque applied on the membrane by rotation of the PH domains promise to shed additional light on this problem (20, 21). Although we did not consider membrane fission in this study, our model indicates that the deviation of the optimal oligomer shape from a regular helix is maximal near the end of the chain. This finding suggests a functional role for oligomer fragmentation: breakup of the chain allows the tip of the oligomer to rotate relative to the underlying membrane and thereby, to apply a torque that can promote membrane fission (21). This hypothesis is supported by experimental evidence for localization of membrane fission sites to the ends of dynamin coated regions (13).

Assembly of membrane proteins into linear aggregates is a common strategy used to stabilize tubular membrane morphologies in the cell. Other notable examples, in addition to dynamin, are BAR proteins, the reticulon and Yop1p/DP1 families of ER proteins, and component of the ESCRT complex. The correspondence of these systems to the model presented here is not exact: BAR proteins can form separate dimers (40) as well as long oligomers via direct interactions of their amphipathic helices (41), reticulons assemble into short arcs and not long helices (42), and while some ESCRT scaffolds are internal to the tubular morphology that they promote (43), others are external to it (44). Yet, all such systems can be characterized by the tilt angle between the membrane surface normal and the oligomer chain’s binormal. Protein–membrane tilt is, therefore, a universal attribute of curvature-stabilizing and curvature-sensing oligomers. Consideration of the effect of tilt in such systems may prove essential for understanding their assembly, structure, and shape.

Experimental Methods

Mathematical Model.

The model is described in detail in SI Appendix.

Unilamellar Vesicles.

The data used for this manuscript were taken from Colom et al. (25) and reanalyzed. The sample preparation is explained in the mentioned paper. Briefly, supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) were prepared from vesicles composed with 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC):Biotinyl Cap PE 90:10 (mol:mol). The vesicles used to form dynamin–lipid tubules were composed for DOPS:1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(cap biotinyl) (Biotinyl Cap PE) or 100% DOPS. All lipids were dissolved in chloroform, dried under N2 for 30 min at 30 °C under vacuum, and then, rehydrated with GTPase buffer (5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.4) for 10 min at room temperature (RT), obtaining a final lipid solution concentration of 2.5 mg/mL. To increase the homogeneity of the vesicles, liposome solutions were freeze–thawed three times in liquid nitrogen and a water bath, respectively.

AFM Images.

The details of sample preparation and high-speed AFM (HS-AFM) configuration are explained in ref. 25. Briefly, an HS-AFM sample scanning NEX (Research Institute of Biomolecule Metrology) (45) setup equipped with short cantilever with a resonance frequency of about 600 kHz and a quality factor Q = 1.5 in liquid (Nanoworld) was used. The microscope was operated in amplitude modulation mode, and bare mica or mica covered with SLBs (DPPC:Biotinyl CAP PE 9:1) was used as support. SLBs was coated with 0.1 μM streptavidin. Dynamin–DOPS tubule sample was added and incubated for 30 min at RT. GTP solutions were added directly to the HS-AFM fluid cell during imaging. HS-AFM movies were analyzed in ImageJ and WSxM 5.0 software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improve and clarify this manuscript. T.S. is supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant 921/15.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1903769116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Antonny B., et al. , Membrane fission by dynamin: What we know and what we need to know. EMBO J. 35, 2270–2284 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinshaw J. E., Schmid S. L., Dynamin self-assembles into rings suggesting a mechanism for coated vesicle budding. Nature 374, 190–192 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faelber K., et al. , Crystal structure of nucleotide-free dynamin. Nature 477, 556–560 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks B., et al. , GTPase activity of dynamin and resulting conformation change are essential for endocytosis. Nature 410, 231–235 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassart A., et al. , Actin and dynamin2 dynamics and interplay during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 205, 721–735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocucci E., Gaudin R., Kirchhausen T., Dynamin recruitment and membrane scission at the neck of a clathrin-coated pit. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3595–3609 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty G. J., McMahon H. T., Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 857–902 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang P., Hinshaw J. E., Three-dimensional reconstruction of dynamin in the constricted state. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 922–926 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundborger A. C., et al. , A dynamin mutant defines a superconstricted prefission state. Cell Rep. 8, 734–742 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux A., Uyhazi K., Frost A., De Camilli P., GTP-dependent twisting of dynamin implicates constriction and tension in membrane fission. Nature 441, 528–531 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pucadyil T. J., Schmid S. L., Real-time visualization of dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission and vesicle release. Cell 135, 1263–1275 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashkirov P. V., et al. , GTPase cycle of dynamin is coupled to membrane squeeze and release, leading to spontaneous fission. Cell 135, 1276–1286 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morlot S., et al. , Membrane shape at the edge of the dynamin helix sets location and duration of the fission reaction. Cell 151, 619–629 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chappie J. S., et al. , A pseudoatomic model of the dynamin polymer identifies a hydrolysis-dependent powerstroke. Cell 147, 209–222 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morlot S., Roux A., Mechanics of dynamin-mediated membrane fission. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42, 629–649 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dar S., Pucadyil T. J., The pleckstrin-homology domain of dynamin is dispensable for membrane constriction and fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 152–160 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danino D., Moon K.-H., Hinshaw J. E., Rapid constriction of lipid bilayers by the mechanochemical enzyme dynamin. J. Struct. Biol. 147, 259–267 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warnock D. E., Hinshaw J. E., Schmid S. L., Dynamin self-assembly stimulates its GTPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22310–22314 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenz M., Prost J., Joanny J.-F., Mechanochemical action of the dynamin protein. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 78, 011911 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shnyrova A V., et al. , Geometric catalysis of membrane fission driven by flexible dynamin rings. Science 339, 1433–1436 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pannuzzo M., McDargh Z. A., Deserno M., The role of scaffold reshaping and disassembly in dynamin driven membrane fission. eLife 7, e39441 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehrotra N., Nichols J., Ramachandran R., Alternate pleckstrin homology domain orientations regulate dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 879–890 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda T., et al. , Dynamic clustering of dynamin-amphiphysin helices regulates membrane constriction and fission coupled with GTP hydrolysis. eLife 7, e30246 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galli V., et al. , Uncoupling of dynamin polymerization and GTPase activity revealed by the conformation-specific nanobody dynab. eLife 6, e25197 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colom A., Redondo-Morata L., Chiaruttini N., Roux A., Scheuring S., Dynamic remodeling of the dynamin helix during membrane constriction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 5449–5454 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDargh Z. A., Vázquez-Montejo P., Guven J., Deserno M., Constriction by dynamin: Elasticity versus adhesion. Biophys. J. 111, 2470–2480 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mears J. A., Ray P., Hinshaw J. E., A corkscrew model for dynamin constriction. Structure 15, 1190–1202 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramachandran R., et al. , Membrane insertion of the pleckstrin homology domain variable loop 1 is critical for dynamin-catalyzed vesicle scission. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4630–4639 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May S., Kozlovsky Y., Ben-Shaul A., Kozlov M. M., Tilt modulus of a lipid monolayer. Eur. Phys. J. E. Soft Matter 14, 299–308 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terzi M. M., Deserno M., Novel tilt-curvature coupling in lipid membranes. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 084702 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helfrich W., Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: Theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C 28, 693–703 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutz M., Helfrich W., Unbinding transition of a biological model membrane. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2881–2884 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meinecke M., et al. , Cooperative recruitment of dynamin and BIN/amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain-containing proteins leads to GTP-dependent membrane scission. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6651–6661 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozlov M. M., Fission of biological membranes: Interplay between dynamin and lipids. Traffic 2, 51–65 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kozlovsky Y., Kozlov M. M., Membrane fission: Model for intermediate structures. Biophys. J. 85, 85–96 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roux A., et al. , Membrane curvature controls dynamin polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4141–4146 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong L., et al. , Cryo-EM of the dynamin polymer assembled on lipid membrane. Nature 560, 258–262 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornyshev A. A., Lee D. J., Leikin S., Wynveen A., Structure and interactions of biological helices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 943–996 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terasaki M., et al. , Stacked endoplasmic reticulum sheets are connected by helicoidal membrane motifs. Cell 154, 285–296 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simunovic M., et al. , How curvature-generating proteins build scaffolds on membrane nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11226–11231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mim C., et al. , Structural basis of membrane bending by the N-BAR protein endophilin. Cell 149, 137–145 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shibata Y., et al. , The reticulon and DP1/Yop1p proteins form immobile oligomers in the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18892–18904 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henne W. M., Buchkovich N. J., Emr S. D., The ESCRT pathway. Dev. Cell 21, 77–91 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCullough J., et al. , Structure and membrane remodeling activity of ESCRT-III helical polymers. Science 350, 1548–1551 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ando T., et al. , A high-speed atomic force microscope for studying biological macromolecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12468–12472 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.