Anthraquinones, produced by a type II polyketide synthase in Photorhabdus luminescens, are derived from polyketide chain shortening.

Anthraquinones, produced by a type II polyketide synthase in Photorhabdus luminescens, are derived from polyketide chain shortening.

Abstract

Anthraquinones, a widely distributed class of aromatic natural products, are produced by a type II polyketide synthase system in the Gram-negative bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Heterologous expression of the antABCDEFGHI anthraquinone biosynthetic gene cluster in Escherichia coli identified AntI as an unusual lyase, catalysing terminal polyketide shortening prior to formation of the third aromatic ring. Functional in vitro and in vivo analysis of AntI using X-ray crystallography, structure-based mutagenesis, and molecular simulations revealed that AntI converts a defined octaketide to the tricyclic anthraquinone ring via retro-Claisen and Dieckmann reactions. Thus, AntI catalyses a so far unobserved multistep reaction in this PKS system.

Introduction

Polyketide natural products attract significant attention due to their remarkable biological and pharmacological activities. Their structural diversity derives from only a few building blocks assembled by different polyketide synthase systems (PKS):1,2 type I PKS represent elaborate multifunctional enzyme complexes responsible for the synthesis of macrolides including erythromycin and candicin,3 whereas type III PKS catalyse the formation of stilbenes, chalcones, and pyrones.4 On the other hand, type II PKS constitute discrete proteins that act in an iterative manner to synthesise polycyclic aromatic compounds such as anthraquinones (AQs), tetracyclines and doxorubicins.5,6 First, a specific acyl carrier protein (ACP) is loaded with an α-carboxylated precursor, and the activated unit is then transferred onto the corresponding ketosynthase. Next, iterative elongation cycles with malonyl-coenzyme A building blocks form the octaketide framework.1 Subsequently, ketoreductases, cyclases and aromatases convert the unstable and highly reactive octaketide into the corresponding target compounds. Notably, the variability of the natural products can be further increased by tailoring enzymes, which are not part of the gene cluster and therefore can be difficult to identify. Yet, these catalysts are specific and perform only minor modifications such as alkylations, hydroxylations, or oxidations, while preserving the octaketide skeleton.

Type I and type III PKS subclasses are well-known from bacteria, fungi, and plants.1 In contrast, type II PKS have only been characterised in Gram-positive Streptomyces and other actinomycetes.5 We identified a biosynthetic gene cluster encoding a type II PKS in the Gram-negative entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens, an enzyme system that enables the biosynthesis of AQs.7 Notably, along with the antimicrobial aurachins8 and pyxidicyclines9 from myxobacteria, AQs represent another fascinating example of the type II PKS machinery. Here, we have introduced the anthraquinone gene cluster antABCDEFGHI from P. luminescens in E. coli. Surprisingly, the formed AQ-256 product exhibits a heptaketide framework, which is unusual since polyphenolic polyketides derived from bacterial type II PKS systems are generally octaketides.1 Our present study reveals that AntI shortens the octaketide intermediate 1 to the final AQ heptaketide. Although this type of reaction is uncommon, a related mechanism has been described for Ayg1p10 from Aspergillus fumigatus and WdYg1p11 from Wangiella dermatitidis. Both fungal proteins are part of PKS systems involved in the biosynthesis of melanin pigments.

We provide insights into the molecular mechanism of AntI via biochemical, crystallographic, computational, and functional characterisations, and show how this enzyme catalyses an elimination reaction, followed by cyclisation to the anthraquinone ring. Taken together, our combined findings elucidate an interesting type of polyketide shortening mechanism.

Results and discussion

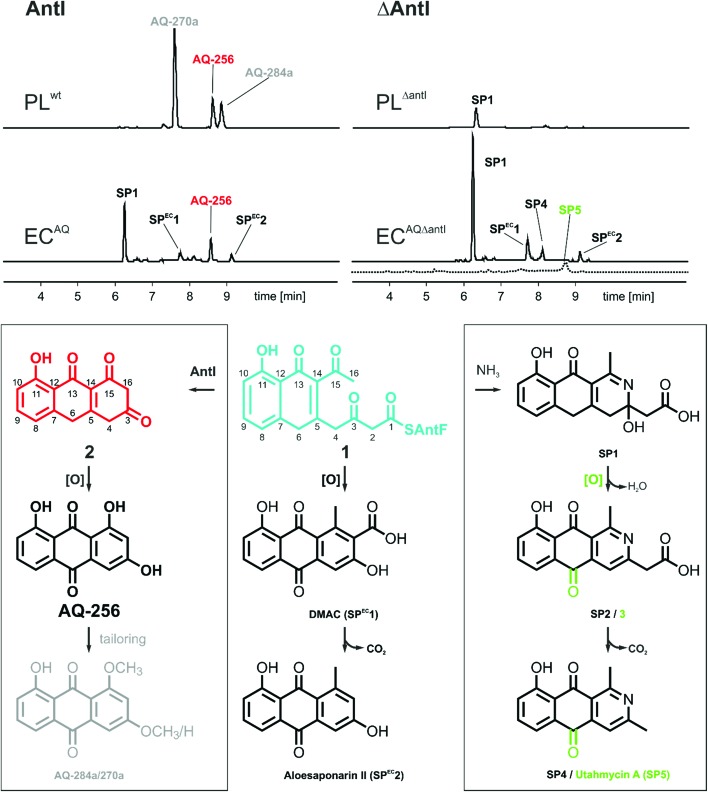

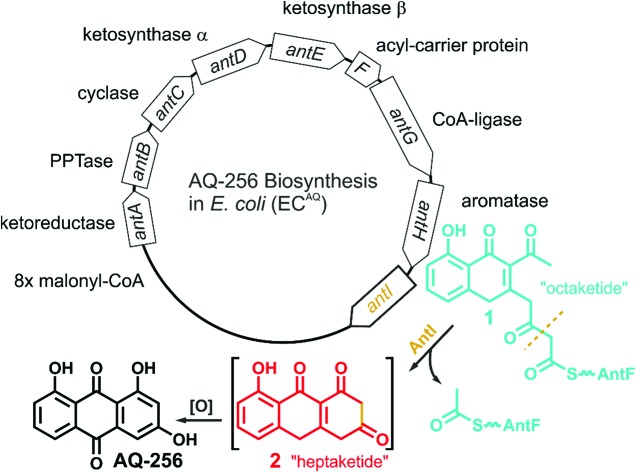

The gene cluster encoding the anthraquinone biosynthetic machinery (antABCDEFGHI) in P. luminescens was heterologously expressed in E. coli (strain ECAQ). This approach allowed detection of the central metabolite 1,3,7-trihydroxyanthracene-9,10-dione (AQ-256), a tricyclic aromatic compound not found in wild-type E. coli (Fig. 1). Yet, methylated derivatives such as AQ-270a (one methyl group) and AQ-284a (two methyl groups) were identified in the natural producer P. luminescens (Fig. 2). As these molecules were not detected in our engineered ECAQ strain, this suggests that the responsible methyltransferases are absent in the ant cluster, and therefore must be located elsewhere in the Photorhabdus genome. Notably, the ECAQ-system is accompanied by several shunt products (SP) such as SP1, SPEC1 and SPEC2 (Fig. 2). One reason for this observation might be that the expression level of the individual genes in the heterologous host is not balanced. Nevertheless, all shunt products could be traced back to the common precursor molecule 1 harboring an octaketide skeleton as its basic structural element, which is covalently bound to the acyl carrier protein AntF via a phosphopantetheine (PPT) prosthetic group (see below). To elucidate the formation of these distinct compounds, we selectively removed individual genes from our ECAQ operon. We focused on classical type II PKS enzymes such as the ketoreductase AntA (C9 carbonyl reduction), aromatase AntH (first cyclisation, C7/C12), and cyclase AntC (second cyclisation, C5/C14). The resulting intermediates were identified by UV-VIS spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (ESI Fig. 1–3, Tables 1–2†). Mutants constructed in P. luminescens (ESI Fig. 4†) and labelling experiments in E. coli (ESI Fig. 3†) allowed assignment of the reaction cascade based on known biosynthetic pathways1,2 (ESI Fig. 5†).

Fig. 1. Overview of the ant biosynthetic gene cluster from Photorhabdus luminescens. The AQ biosynthesis is highlighted with a focus on AntI catalyzed polyketide shortening.

Fig. 2. HPLC/UV (420 nm, solid line) and HPLC/MS (EIC m/z 254 for SP5, dashed line) analysis for polyketide production in the presence and absence of AntI in E. coli (EC) and Photorhabdus luminescens (PL). Identified key metabolites (top) and suggested biosynthesis pathways to these compounds (bottom) are shown.

Most polyphenolic polyketides derived from bacterial type II PKS systems are octaketides.1 In this respect, AQ-256 with its heptaketide framework is exceptional. Moreover, the local alignment search in the NCBI databank revealed that AntI (Uniprot: Q7MZT8) is predominantly found in Photorhabdus species. Thus, AntI is a promising candidate for polyketide shortening, followed by a unique cyclisation of the third aromatic ring in AQ biosynthesis (Fig. 1). In order to confirm our hypothesis, we generated a deletion mutant of antI in P. luminescens (PLΔantI). As expected, the modified strain lost the ability to produce AQ-256 and its methylated derivatives (Fig. 2), and only the nitrogen-containing octaketide derivative SP1 was formed. Next, we removed antI from our engineered E. coli strain (ECAQΔantI) and analysed the resulting product pattern. As expected, AQ-256 is no longer present. However, in contrast to the Photorhabdus ΔantI mutant, which produced only the SP1 metabolite, we now observed several compounds. Via detailed characterisation of the ECAQΔantI lysate, we identified SP1–5, SPEC1, and SPEC2, all of which could unambiguously be shown to derive from molecule 1 (Fig. 2, ESI Fig. 5†). In summary, (i) the dihydropyridine moiety of SP1 results from 1 by assimilation of intracellular NH3; (ii) SP4 is formed from SP1 after dehydration and decarboxylation; (iii) utahmycin A12 (SP5) is an oxidation product of SP4; (iv) 3,8-dihydroxy-1-methyl-anthraquinone-2-carboxylic acid (DMAC, SPEC1) is the oxidized product of an aldol-condensation of 1; and (v) aloesaponarin II (SPEC2) results from the spontaneous decarboxylation of SPEC1. The assignment of these shunt products strongly indicates that AntI orchestrates the cyclisation of the third ring system in the AQ biosynthesis. In this reaction, 4-(3-acetyl-5-hydroxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)-3-oxobutanoic acid (1) bound to AntF via the PPT-prosthetic group possibly acts as the AntI substrate that is converted to 8-hydroxy-1,10-dihydroanthracene-2,3,9(4H)-trione (2, Fig. 1). We thus propose that AntI catalyses the last step in this reaction cascade, whereas formation of the aromatic quinone moiety of AQ-256 occurs in an enzyme-independent manner by keto–enol-tautomerism and spontaneous oxidation.

The rapid turnover of the precursor molecule 1 in combination with the resulting large variety of different shunt products achieved in our modified E. coli system, encouraged us to additionally validate octaketide intermediate 1 as the true AntI substrate. To this end, the biosynthesis of the well-known blue pigment actinorhodin from Streptomyces coelicolor appeared to be ideal, as it transforms 1 into the octaketide 4-dihydro-9-hydroxy-1-methyl-10-oxo-3-H-naphtho-[2,3-c]-pyran-3-(S)-acetate (S-DNPA). In this case, the stereospecific ketoreductase (Red1) acts as a tailoring enzyme by recognising the metabolite and reducing its 3β-keto group to a secondary alcohol.13 This peculiarity led us to extend the ECAQΔantI construct via a codon-optimized actVI ORF1 gene, encoding Red1, which resulted in the ECAQΔantI+red1 strain. In this variant, AQ-256 was no longer produced, but we indeed detected the compound S-DNPA (Fig. 3a), confirming the activity of Red1 in our model system. These results further prove that octaketide 1 is formed, and then subsequently shortened and cyclised by AntI.

Fig. 3. (a) HPLC analyses of E. coli expressing antABCDEFGHI and antABCDEFGH + actVI-ORF1 (encoding Red1). Besides UV traces (420 nm, solid line), EIC for AQ-256 (m/z 255 [M – H]–, dashed line) and S-DNPA (m/z 287 [M + H]+, dotted line) are shown. (b) In HPLC/MS analyses of E. coli expressing antABCDEFGH with the AntI-mutants S245A or H355A, metabolite 1 is no longer detected, but compound SPEC2 (m/z 253 [M – H]–, dashed line) is formed. Mutation of D326 to alanine did not alter catalysis. (c) Conversion of model compounds S1–S4 into S5.

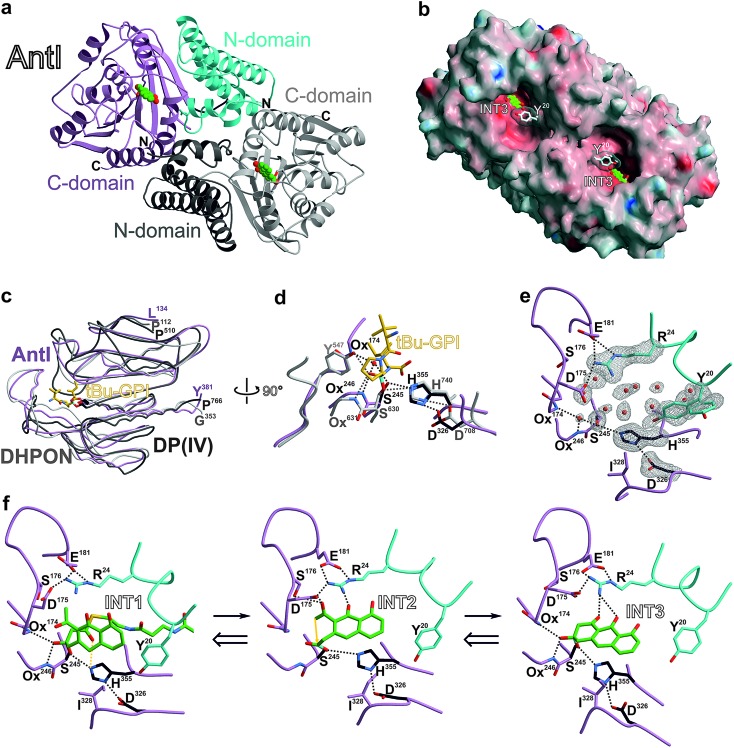

With the identification of AntI's substrate (1), we wanted to obtain a deeper mechanistic insight into the catalytic properties of this fascinating enzyme. AntI was therefore heterologously expressed in E. coli, purified, and crystallised with one subunit in the asymmetric unit. Native diffraction data were collected to 1.85 Å resolution, and the structure was phased by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion using selenomethionine labelling (PDB ID: ; 6HXA, Rfree = 0.209, ESI Table 3†). The structure reveals that AntI functions as a homodimer, with each subunit comprising two domains (Fig. 4a) that are connected by a short linker sequence (residues 130–134). The N-terminal domain (residues 7–130) comprises an α-helix bundle (α1–α5) that orchestrates the arrangement of the two subunits in a back-to-back orientation with a contact area of 2055 Å2. The C-terminal domain (residues 134–381) contains a twisted eight-stranded β-sheet (β1–β8), which is flanked by 7 α-helices (α6–α12) exhibiting an α/β-hydrolase fold (Fig. 4c).14

Fig. 4. Crystal structure of AntI. (a) The homodimer (ribbon plot) is depicted with a modelled intermediate (INT3, balls-and sticks, carbon atoms in green). N- and C-domains of subunit A are coloured in pink and cyan, respectively; subunit B is shown in grey. (b) Surface representation of AntI. The active site of the lyase is solvent exposed. Colours highlight negative and positive electrostatic potentials contoured from –40kBT/e (red) to +40kBT/e (blue). (c) Superposition of the α/β-hydrolase fold of AntI (residues 174–381, pink, PDB ID: ; 6HXA) with domains of 2,6-dihydroxy-pseudo-oxynicotine hydrolase (DHPON, light grey, PDB ID: ; 2JBW)16 and the human dipeptidyl peptidase DP(IV)–tBu-GPI complex (grey, PDB ID: ; 2AJB).17 (d) Structural overlay of AntI with the active site of DP(IV) (C-atoms in grey) covalently bound to the tBu-GPI surrogate. Notably, the tetrahedral coordination fits into the active site of AntI, and identifies its putative oxyanion hole (Ox), which is occupied by a water molecule. In AntI, the main chain atoms of Leu174NH and Phe246NH might form the oxyanion hole, while in DP(IV) Tyr631N and Tyr547OH take over this function. Hydrogen bonds are drawn as dashed lines. (e) Close up view of the active site of AntI showing the 2Fo – Fc electron density map (grey meshes contoured to 1.0 σ) for the catalytic triad, Tyr20 (alternative conformation which might function as the gate keeper) and Arg24. The abundance of well-defined water molecules (red spheres) is a clear indication for the possible substrate binding site. (f) Proposed multistep reaction sequence of AntI including a retro-Claisen reaction and a Dieckmann condensation. The INT1, INT2, and INT3 intermediates were modelled based on the DP(IV)–tBu-GPI complex. The ligand-bound AntI structures remains dynamically stable during the MD simulations (see ESI†). The calculations were performed in the reverse direction from INT3 to INT1.

AntI forms a rod-shaped particle (Fig. 4b) with its N- and C-terminal domains enclosing a conspicuous intramolecular substrate binding cavity with approximate dimensions of 8 × 8 × 20 Å3. A DALI search15 demonstrated similarity of AntI with 2,6-dihydroxy-pseudo-oxynicotine hydrolase (DHPON; PDB ID: ; 2JBW, with a sequence identity of 23%, N-domain: Z-score = 10.6, RMSD = 2.5 Å; C-domain: Z-score = 30.5, RMSD = 1.9 Å),16 a C–C bond cleaving α/β-hydrolase from the Gram-positive bacterium Arthrobacter nicotinovorans that is involved in nicotine degradation (Fig. 4c). The structural comparison of AntI with DHPON reveals the catalytic centre of a serine-type protease composed of Ser245, Asp326, and His355. In the active site, Ser245 is positioned at the tip of a sharp turn between sheet β5 and helix α8, called the nucleophilic elbow,14 and points towards the helix dipole generated at the N-terminus of helix α8 (Fig. 4d). The mutation of Ser245 or His355 to alanine confirmed the catalytic importance of these residues (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the Asp326Ala mutant remains active. Thus, Asp326 polarises His355, but proton transfer from Ser245 to His355 is possible also without the aspartate residue. Inspection of the 2Fo – Fc-electron density map illustrates that the catalytic centre is enclosed by a cluster of bulk solvent molecules, the release of which might facilitate substrate binding (Fig. 4e). Consistent with the asymmetric hydrophilic rim of 1, which is composed of three oxygen atoms, the specificity pocket exhibits an amphiphilic character. The hydrophobic half of this pocket comprises Phe27, Ile244, Ile326, Val356, Leu358, and Ile361, whereas the polar part includes Arg24, Asp175, Ser176, Glu181, and Asp287. The central opening into the chamber is formed by Tyr20, Pro281, and Asp327. Interestingly, the sidechain of Tyr20 is observed in two alternative conformations (Fig. 4e), suggesting a regulatory role for this residue in allowing the substrate to access the active centre.

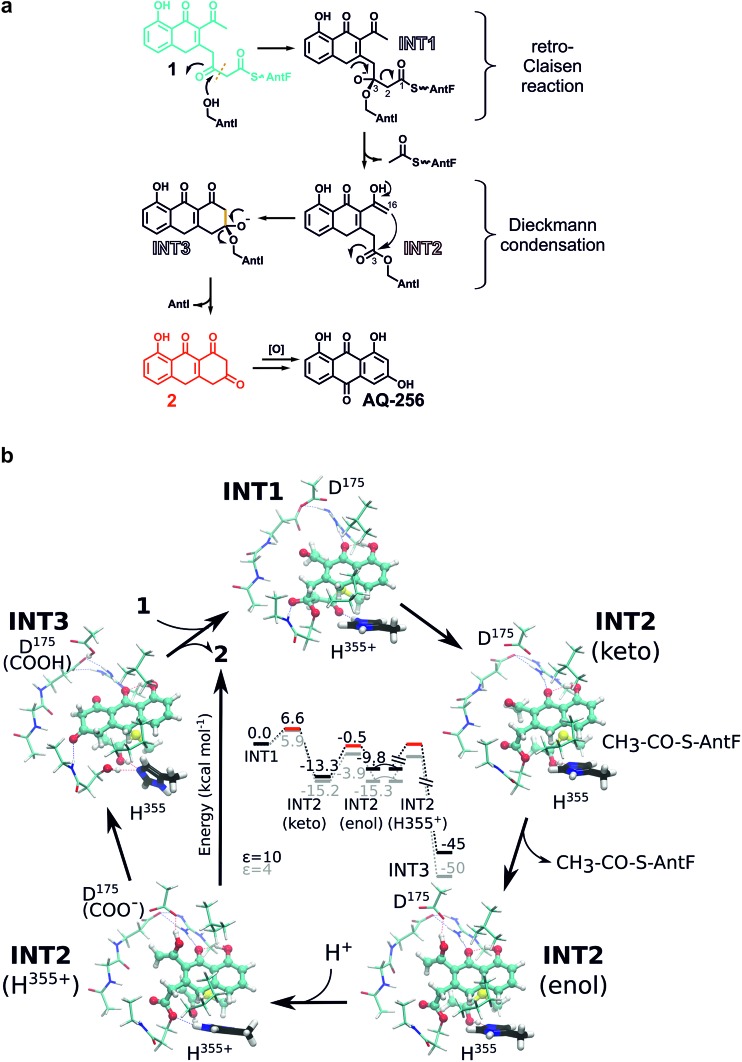

We aimed to obtain detailed insights into the reaction cascade of AntI. While the elimination reaction could clearly be assigned to AntI, the enzyme-dependency of the cyclisation resulting in the anthracene ring system still required experimental validation. We therefore synthesised surrogates S1 and S2 representing non-cyclised derivatives of the heptaketide intermediate (Fig. 3c, ESI Fig. 6†): S1 harbours a free carboxylate moiety, whereas the methoxy group of S2 mimics the sidechain of Ser245. Interestingly, S1 is stable in solution and in the presence of AntI, whereas S2 undergoes rapid ring closure to S5 even without AntI (Fig. 3c). These findings indicate that an oxo-ester with AntI has to be formed, to enable intermolecular cyclization. Hence, AntI is involved in the multistep biosynthetic route by catalyzing polyketide shortening and subsequent ring formation.

The next goal was to confirm the retro-Claisen reaction for shortening the octaketide skeleton to a heptaketide. In contrast to the Dieckmann condensation, this requires a strong nucleophile, which might represent the rate-limiting step in AntI catalysis. To this end, we determine whether AntI works like a tailoring enzyme that uses intermediate 1 as its substrate after hydrolysis from the PPT arm (containing a free carboxylate), or whether 1 is still covalently bound to its ACP AntF. We synthesised 2-carboxymethyl-benzoic acid (surrogate S3), as well as its corresponding methyl ester S4 which mimics metabolite 1. Both molecules remain stable in solution and in the presence of AntI. This observation is in contrast to the spontaneous enzyme-independent aromatisation of ester surrogate S2 (see above). Thus, compared to the Dieckmann condensation, we assume that AntF is mandatory for the retro-Claisen reaction.

To obtain mechanistic insights into the structure and dynamics of these reaction intermediates, we performed molecular simulations based on our experimentally solved structure of AntI. As a starting point for these computations, we used a surrogate pose of the hydrolytic domain of the homologous porcine dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DP(IV), residues 511–766, PDB ID: 2AJB, RMSD of 145 Cα-atoms = 2.7 Å, sequence identity 17%). DP(IV) was solved with the tripeptide tert-butyl-Gly-Pro-Ile (tBu-GPI), a surrogate that covalently binds in a sp3-configuration to the catalytic Ser630Oγ by forming an orthoester.17 Hereby, the alkoxide moiety of the inhibitor is negatively charged due to its strong interaction with the oxyanion hole. The tetrahedral coordination of tBu-GPI resembles the expected transition state structure with the alcoholate stabilised by hydrogen bonds to the backbone of Tyr631NH (3.1 Å) and the sidechain of Tyr547OH (2.9 Å). Intriguingly, superimposing the α/β-hydrolase fold of DP(IV) with AntI reveals an excellent structural overlap of the catalytic residues (Fig. 4c). We observe that in AntI the putative oxyanion hole is occupied by a well-defined water molecule (Fig. 4d) that forms hydrogen-bonds to the backbone of Leu174NH (2.7 Å) and Phe246NH (3.2 Å).

In accordance with the structural similarities of the active site in AntI and DP(IV), we modelled the putative reaction intermediates INT1–INT3 and refined the protein–ligand complexes by classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The procedure was initiated in reverse order, starting from a fully formed anthracene ring system at the same site as the tetrahedral hemiacetal carbon atom of tBu-GPI is bound. Thus, we first modelled the late product state INT3 which adopts a configuration having only one chiral centre out of plane with respect to the surrounding sp2-hybridised atoms. We find that INT3 remains stably positioned at the oxyanion hole, the catalytic centre, and Arg24 during our 100 ns MD simulations. Interestingly, Tyr20, which is located at the entry gate of the substrate binding-pocket, switches between an open and a closed conformation during the MD simulations (ESI Fig. 7†). This finding is consistent with the two alternative positions of this residue in the X-ray structure (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, our simulations suggest that INT3 forms van der Waals contacts with Leu284 and Ile328, as well as hydrogen bonds between the biaryl hydroxyl and keto groups via Arg24. In addition, the aromatic ring system of INT3 is stabilised from both sides by cation–π interactions with Arg24 and by π-stacking with His355 (Fig. 4f, left panel). These insights allowed us to analyse the Dieckmann condensation in more detail.

INT3 was used as the starting pose for modelling the INT2 state by following the enzymatic reaction cycle in reverse order. Thus, we opened the third ring of AQ-256 between C3 and C16, leading to an acetyl group and an ester bond at the nucleophile Ser245Oγ (INT2, Fig. 4f, central panel). The INT2 pose remains stable during the MD simulations, with less than 2 Å fluctuation in the atomic positions of INT2 relative to INT3 (ESI Fig. 7†). However, the INT2 ligand has an increased flexibility that leads to rotation of the acetyl group by 45°. In addition, the carbonyl oxygen coordinates to the sidechain of Ser176, forming close contacts with Asp175 that favour the enol tautomer of the ligand. In accordance with the AntI X-ray structure, the sidechain of Asp175 is in proximity to Asp287 (2.5 Å) and, together with Glu181, forms an ion-pair with Arg24. This conformation facilitates deprotonation of the enol tautomer, via proton transfer to His355. Subsequently, the generated alkoxide might act as the nucleophile, initiating the Dieckmann condensation by intramolecular ring closure (Fig. 5a). The reaction takes place via a Bürgi–Dunitz angle in which the carbon atom in α-position (C16) is perfectly oriented to form a covalent bond with the carbonyl group (C3) of the acyl–AntI complex leading to INT3 (Fig. 4f, right panel). Starting from INT2, this attack is regio-selective from the re-face, while the backside is shielded from the catalytically active centre to exclude saponification that would result in shunt products.

Fig. 5. (a) Proposed reaction scheme for the conversion of 1 into AQ-256 by AntI. (b) Quantum chemical DFT calculations (B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP/ε = 4/10) on a putative mechanism starting from INT1. See main text for detailed description.

We prolonged INT2 by an additional acetyl group, and converted the ester at the active site Ser245 back to sp3-hybridisation (C3) (INT1, Fig. 4f, left panel). In doing this, we expected that the flexible, ca. 20 Å long PPT chain, introduces some structural uncertainty into the model. Intriguingly, the MD simulations of this state suggest that the oxyanion hole is rigid and dynamically stable over time, allowing us to properly refine the orientation of the introduced acyl–thioester moiety in INT1. The steric hindrance from the PPT arm and the adjacent acetyl group at C14 significantly increased in our calculations, relative to the INT2 and INT3 states. The predictions suggest that INT1 may re-orient towards the catalytically active serine residue in a new position induced by the tetrahedral configuration near the oxyanion hole (Fig. 4f, left panel). This conformation directs the carbonyl oxygen of the thioester at C1 towards His355, which might initiate the breakage of the adjacent C2–C3 bond. Due to the anionic charge distribution within the active site, both nitrogens of His355 might be protonated in the late state of INT2. In order to probe the energetics of these putative INT1–INT3 intermediates, we performed quantum chemical density functional theory (DFT) calculations, starting from an active site model system constructed from an MD-relaxed snapshot of INT1 (Fig. 5b). The DFT calculations illustrate that the proton transfer from His355 to the carbonyl oxygen of the thioester group has a barrier of less than 10 kcal mol–1, and is exergonic by 13–15 kcal mol–1, indicating that the reaction is both kinetically and thermodynamically feasible. Hereby hydrolysis of the ester at the nucleophilic Ser245 is supressed, and the subsequent Dieckmann condensation favoured. For the keto–enol tautomerisation forming INT2, we obtain a reaction barrier of ca. 12 kcal mol–1 leading to an energetically degenerate state at ca. –10 kcal mol–1. Proton transfer from the enol-tautomer to the nearby Asp175 increases the nucleophilic character of the enol, hence favouring the ring formation that takes place semi-concertedly. The cyclisation reaction succeeds via a Bürgi–Dunitz angle in which the carbon atom in α-position (C16) is perfectly oriented to form a covalent bond with the carbonyl group (C3) of the acyl–AntI complex leading to INT3. Due to multiple bond formations and cleavage processes, the exact barrier for the INT2 → INT3 reaction could not be determined, but the entire trajectory is energetically strongly exergonic by more than 40 kcal mol–1. Additionally, we find that the process is favoured by re-protonation of the Ser245 nucleophile via His355, which regenerates the active site residue. Taken together, our sampled configurations and putative DFT models manifest that release of an acetyl-AntF induce shortening of the octaketide backbone and as a consequence, forms the third aromatic ring in AQ-256.

Conclusion

Anthraquinone derivatives may contribute to the toxicity of Photorhabdus extracts against other organisms such as insects, fungi and bacteria. In most strains of Photorhabdus18,19 corresponding gene clusters have been identified (ESI Fig. 8†), implying an important function of these natural products from this genus. In such pathways, the lyase AntI is exceptional because it shortens polyketides. The reaction mechanism of the lyase provides a unique route to the formation of the tricyclic aromatic ring (Fig. 5a) – a structural feature typically introduced by dedicated cyclases in type II PKS pathways.1,20 Interestingly, AntI and its homologues are also found in type II PKS-encoding biosynthetic gene clusters of cyanobacteria and other Gram-negative bacteria (ESI Fig. 8†), indicating that polycyclic aromatic polyketides are more abundant than previously thought. Furthermore, the amino acids around the proposed active centre of Ayg1p from Aspergillus fumigatus10 and WdYg1p from Wanganella (Exophiala) dermatitidis11 are identical to AntI (ESI Fig. 9 and 10†), and therefore they can be clearly assigned as lyases. Intriguingly, these two enzymes are produced in pathogenic fungi and play a key role in the biosynthesis of the virulence factor 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene-melanin. Thus, the structural and functional characterisation of AntI described here opens up a hitherto unexplored mechanism for an exciting class of catalysts.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Sebastian Fuchs and Dr Darko Kresovic for MALDI-MS measurements and discussion. The Tsai and Brady labs are acknowledged for polyketide standards and the Ichinose lab for providing original data about S-DNPA. We thank the staff of the beamline X06SA at the Paul Scherrer Institute, SLS, Villigen (Switzerland) for assistance during data collection. This work was supported by the DFG within the SPP 1617 (H.·B.·B.), SFB 749 (M. G.), SFB 1035 (V. R. I.·K.) and the LOEWE program of the state of Hesse as part of the MegaSyn research cluster (H.·B.·B.).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9sc00749k

References

- Hertweck C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:4688–4716. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staunton J., Weissman K. J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla C., Herschlag D., Cane D. E., Walsh C. T. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2875–2883. doi: 10.1021/bi500290t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M. B., Noel J. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003;20:79–110. doi: 10.1039/b100917f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertweck C., Luzhetskyy A., Rebets Y., Bechthold A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:162. doi: 10.1039/b507395m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Pan H.-X., Tang G.-L. F1000Research. 2017;6:172–212. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10466.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann A. O. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1721–1728. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:2712–2716. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter F., Krug D., Baumann S., Müller R. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:4898–4908. doi: 10.1039/c8sc01325j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii I. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44613–44620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler M. H. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008;7:1699–1711. doi: 10.1128/EC.00179-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J. D., King R. W., Brady S. F. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:976–979. doi: 10.1021/np900786s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8181–8188. doi: 10.1021/bi700190p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollis D. L. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 1992;5:197–211. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L., Laakso L. M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W351–W355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleberger C., Sachelaru P., Brandsch R., Schulz G. E. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;367:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel M. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:768–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias N. J. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:1676–1685. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias N. J. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:537. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2862-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi T. ChemBioChem. 2017;18:316–323. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.