Abstract

Individuals are becoming more involved in managing their own health. Health self-management technologies have the potential to help older adults remain well by promoting exercise and a good diet. However, older adults may or may not decide to adopt wellness management technologies. Adoption is a process and the intent to adopt may change over time. Sixteen older adults (8 females; Mage=70.06, SD=3.09; range=65–75) used one of two wellness management technologies (the Fitbit One or myfitnesspal.com) over a 28-day period. Initially, all participants were open or neutral to adopting their technologies. After 28 days, 12 participants intended to adopt and 4 participants did not intend to adopt. The diary data revealed that over time, adopters made more positive comments than non-adopters. Both adopters and non-adopters mentioned perceived ease of use praises and complaints, whereas only adopters mentioned praises regarding usefulness. Results are interpreted within the frameworks of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and the diffusion of innovation (Rogers, 2003). Changes in intent to adopt suggest that experience is important in the adoption decision. Adoption of wellness management technologies by older adults may increase if designers attend to the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness factors identified in this study.

INTRODUCTION

Health care is shifting towards a patient-professional partnership (Bodenheimer, Lorig, Holman, & Grumback, 2002; Mitzner, McBride, Barg-Walkow, & Rogers, 2013). Individuals are becoming more involved in managing their own health. Daily decisions have the potential to be made easier with the support of technologies (Albaina, 2008). For example, managing diabetes through mobile phones has resulted in better self-management behaviors and improved health outcomes (Holtz & Lauckner, 2012). Wellness management technologies help users track their health statuses by logging exercise, caloric intake, and other, often customizable, measures (e.g., Fitbit, Striiv, Jawbone Up). Users are able to set goals and receive feedback on how close they are to meeting those goals, often through the wellness management technology’s corresponding website. These technologies can help manage chronic conditions, which older adults are more likely to have than younger adults (Freid, Bernstein, & Bush, 2012).

Disease management is not the only potential use of wellness management technologies. Maintaining healthy habits with respect to exercise and diet, regardless of disease status, is another potential use. Healthy living is associated with an abundance of advantages for older adults. For example, cognitive benefits, physical benefits, and higher quality of life are all associated with exercise (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Elward & Lawson, 1992; Rejeski & Mihalk, 2002). Intervention-based studies with pedometers demonstrate that technologies can increase exercise in older adults (King et al., 2008; Tudor-Locke et al., 2011).

The promise of wellness management technologies for older adults relies on the assumption that older adults will actually adopt these technologies – an assumption that may not necessarily hold. Fox and Duggan (2013) found that 71% of adults over 65 tracked their weight, diet, or exercise but only 2% used a computer program, 1% used an app or mobile tool, and less than 1% used a website or other online tool. Rather, the adults in their study relied on non-technology methods such as keeping track in their heads or on paper. Furthermore, advertisements for devices that depict older adults as users are sparse and older adults are often left out of usability testing altogether (Fisk, Rogers, Charness, Czaja, & Sharit, 2009). There is a need to better understand why older adults may choose to use wellness management technologies.

Fausset and colleagues (2013) examined this question with eight case studies of older adults using wellness management technologies over two weeks. Participants were generally positive about their technologies at the start but by the end of the study only three participants unconditionally planned to continue using the technology in the future. Applying the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003), Fausset et al. considered the role of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness in attitudes about adoption (Davis, 1989). The users’ interview comments suggested perceived usefulness was a key factor driving intention to adopt.

The goal of the present study was to further investigate intentional adoption of wellness management technology by examining the opinions of 16 older adults who used one of two technologies (the Fitbit One or myfitnesspal.com) over a 28-day period. Rogers’ (2003) theory of the diffusion of innovation suggested that technology adoption is an on-going process. Consequently, intentional adoption does not necessarily lead to continued adoption. Our focus here is on how the intent to adopt a wellness management technology may shift over usage.

METHOD

Participants

Sixteen (8 males, 8 females) adults between the ages of 65 and 75 (M= 70.06, SD=3.09) were recruited from the Georgia Tech HomeLab to participate in this study. Participants were compensated $100. Participants all had a working computer in their homes but no previous experience using a wellness management technology. Thirteen participants identified themselves as Caucasian and three participants identified themselves as African American. Seven participants reported earning a Bachelor’s degree or higher. Fifteen participants rated their general health as good or very good. One participant rated his health as between fair and good. myfitnesspal.com and Fitbit One groups did not differ significantly on any of these demographics and background variables.

Design

Participants were assigned to use either myfitnesspal.com or the Fitbit One for 28 days. To avoid disruptions caused by curiosity about a spouse’s different technology, if two spouses were recruited for the study, they were given the same technology. Attitudes about the technologies were assessed at the start, throughout, and at end of the study.

Materials

Technologies.

Myfitnesspal.com and the Fitbit One were selected based on findings from Fausset et al. (2013). Both technologies were associated with participants’ intentions to adopt and both track exercise as well as food consumption. Both technologies also allow users to track their progress towards personal fitness goals. Participants’ synchronizations and log data were captured for analyses.

Myfitnesspal.com (Figure 1a) is a free website on which users can manually enter foods consumed, exercises completed, and body weight. Users can add custom logs and can read and write blogs.

Figure 1a-1c.

Images of the technologies used in the present study.

The Fitbit One (Figure 1b) is a commercially available and wearable technology that automatically counts steps taken, stairs climbed, calories burned, and minutes slept. In addition to a silent alarm feature, the Fitbit One has a corresponding website (Figure 1c) where users can manually enter additional information, including food, weight, mood, heart health, blood pressure, glucose levels, and any custom logs.

Questionnaires.

Six initial questionnaires were administered: (1) Background and Health Information (Czaja et al., 2006); (2) Technology Experience Profile (Barg-Walkow, Mitzner, & Rogers, 2014); (3) Self-Efficacy for Health Management (Becker, Stuifbergen, Oh, & Hall, 1993); (4) Locus of Control for Health (Wallston, Wallston, & DeVellis, 1978); (5) Exercise Motivation (Markland & Ingledew, 1997); and (6) Activity Tracking Technology Opinions, which contained six questions related to perceived ease of use, six questions measuring perceived usefulness, and three questions capturing intent to adopt on a 1 (Extremely Unlikely) to 7 (Extremely Likely) scale (Table 1; adapted from Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Questionnaires 3–6 were re-administered after 28 days in the study.

Table 1.

Examples of Technology Opinion Questions

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Perceived ease of use | My interaction with an activity tracking technology would be clear and understandable. |

| Perceived usefulness | I would find an activity tracking technology useful in my daily life. |

| Intent to adopt | Given that I have access to an activity tracking technology, I predict that I would use it. |

Interviews.

Participants were interviewed at the start and at the completion of the study to assess their attitudes and opinions about the technologies used (e.g., likes, dislikes, recommendations).

Diaries.

For the first two weeks, participants were prompted to complete a daily diary of three questions that were designed to take no more than five minutes to finish. During the last two weeks of the study, participants completed the diary twice a week. The questions were:

Please describe any difficulties you had with your technology today.

Please describe anything new that you learned about your technology today.

Please comment about any thoughts/experiences you had while using your technology today.

Procedure

Prior to the initial home visit, participants were mailed an informed consent form and initial questionnaires. During the initial home visit, researchers set up the technology and conducted the initial interview. For the next 28 days, participants completed diaries and usage data were collected. The final questionnaires were mailed to the participants’ homes towards the end of the study and were collected during the final interview.

RESULTS

Participants had a moderate amount of technology experience, with a general technology breadth mean score of 23.06, (SD=4.92, range=12–32 on a 0–36 scale). Participants had a technology use frequency mean score of 1.57 (SD=.42, range=.83–2.47 on a 0 to 3 scale).

Participants in the two technology conditions did not differ in initial, t(14)=−.51, p=.62, or final intents to adopt, t(14)=−.23, p=.82. Consequently, the remaining analyses combined the participants from the two technology groups.

Twelve participants used their technology all 28 days. Three participants used their technology between 24 and 27 days. One participant used his technology for 18 days, but was out of town for most of the days the technology was not used.

Questionnaires

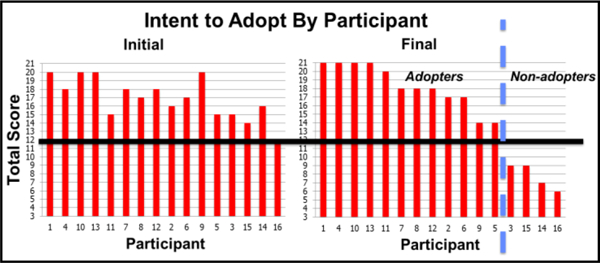

Intent to adopt was calculated by taking a sum of each participant’s responses to the three corresponding questions, creating a 3–21 possible range. Initially, every participant scored 12 (midpoint on the scale) or above on intent to adopt. However, after 28 days of using their assigned wellness management technologies, 12 participants scored above the midpoint and 4 fell below the midpoint (Figure 2). Because of this divide, individuals with final intent to adopt composite scores above 12 were categorized as adopters. Participants with scores below 12 on the final intent to adopt measure were categorized as non-adopters.

Figure 2.

Participants’ intent to adopt scores on a 3 to 21 scale. The neutral midpoint is bolded. The dashed line divides adopters and non-adopters.

Adopters and non-adopters differed significantly on initial, t(14)=3.34, p<.02, and final intent to adopt, t(14)=7.70, p<.01 (Figure 3). For participants categorized as adopters, a paired-sample t-test revealed no significant changes in their intent to adopt over time, p=.52. Non-adopters did change their intent over time, t(3)=7.51, p<.02.

Figure 3.

Intent to adopt means of adopters and non-adopters, on a scale of 3 to 21, at the start and end of the study. Asterisks represent significant differences. Error bars show standard error.

In the UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003), perceived ease of use and percieved usefulness impact intent to adopt. Initial and final perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness scores were calculated by taking the mean of their six corresponding questionnaire items, creating ranges of 1–7. Initially, adopters and non-adopters did not differ significantly in their perceptions of ease of use, p=.10 (Figure 4). However, by the end of the study, the groups’ perceptions of ease of use did differ significantly, t(14)=2.74, p=.02. Examing only adopters, perceived ease of use did not significantly change over time, p=.78. Perceived ease of use also did not change significantly for only non-adopters, p=.69.

Figure 4.

Perecieved ease of use means of adopters and non-adopters, on a scale of 1 to 7, at the start and end of the study. The asterisk represents a significant difference. Error bars show standard error.

When considering the role of perceived usefulness (Figure 5), differences between adopters and non-adopters emerged both at the start of the study, t(14)=3.89, p<.01, and at the end of the study, t(14)=4.01, p <.01. As for perceived ease of use, change was not observed within only adopters, p=.56 or only non-adopters, p=.39, throughout the course of the study.

Figure 5.

Percevied usefulness means of adopters and non-adopters, on a scale of 1 to 7, at the start and end of the study. Asterisks represent significant differences. Error bars show standard error.

In sum, non-adopters did score lower than adopters on intent to adopt, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness measures compared to adopters. However, only the intent to adopt measure revealed changes within the non-adopter group over time, where initially non-adopters were, on average, intending to adopt their wellness management technologies. This may suggest that intent to adopt is a more diagnostic measure than perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness for revealing changes in opinions over usage. To investigate why non-adopters chose not to continue using their technologies, we examined diary comments.

Diaries

Diary comments that related to the technology were coded as positive, negative, or neutral. Two independent coders had higher than 90% agreement for all three codes; the results from Coder 1 are presented here. In general, adopters made more comments than non-adopters. Additionally, adopters made more positive than negative comments whereas non-adopters made more negative than positive comments (Table 2). In response to the question about difficulties experienced, 28 comments from adopters explicitly stated “no difficulties” but only 2 such comments were found for non-adopters.

Table 2.

Valence of Diary Comments Made By Adopters and Non-adopters

| Adopters (n=12) | Non-adopters (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Comments | 118 | 10 |

| Negative Comments | 103 | 22 |

| Neutral Comments | 74 | 6 |

| Ratio of Positive/Negative | 1.14 | .45 |

For non-adopters (n=4), positive comments were themed around ease of use of the help functions and general ease of use of the technology. Non-adopters made negative comments about the time it took to use the technology, especially when entering data. Fitbit One non-adopters disliked that they were unable to use the device to track exercise in the pool. Users who ultimately did not intend to adopt myfitnesspal.com had difficulty adding foods to the calorie tracker.

Adopters (n=12) made more comments overall. Themes that emerged in their positive comments related to ease of use, to the usefulness of help functions, to the usefulness of viewing progress over time, and to liking the technology in general. Fitbit One users also mentioned liking the accuracy of the technology and the sleep and alarm functions whereas myfitnesspal.com users mentioned liking the informative links and extensive food database.

Adopters also reported disliking the amount of time it took to use the technologies in entering data. Though some mentioned the Fitbit One was accurate, others did not agree. Fitbit One adopters also desired to bring the device into the pool. Although some myfitnesspal.com users mentioned that many name brand foods could be found, others explained that adding homemade foods could be difficult. Examples of comments are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example of Technology-related Comments

| Final intent | Technology | Question topic | Comment | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopter | Fitbit One | Thoughts and experiences | I would hate to have my fitbit show no activity. Using the Fitbit forces me to take a walk everyday!!! That’s a good thing… | Positive |

| Adopter | myfitnesspal.com | New things learned | Certain there [were] new [things] that I could have learned today, just did not have time to invest today. | Negative |

| Non-adopter | Fitbit One | Difficulties | Still trying to figure out the food intake and make it work. Not getting any better. I make inputs, but can’t get them to record. | Negative |

| Non-adopter | myfitnesspal.com | Difficulties | Found it easy to use. | Positive |

In sum, adopters disliked many of the same aspects of the technologies that non-adopters disliked. However, unlike adopters, non-adopters never mentioned liking the overall technology. Adopters found it helpful to view their progress, to plan meals, to stay motivated, or to know their projected fitness. Although some non-adopters mentioned it was easy to use, none commented positively on its usefulness.

DISCUSSION

This study examined underlying reasons why older adults intentions to adopt wellness management technologies did or did not change over time. Overall, users who intended to use wellness management technologies at the end of the 28-day trial period initially had greater intent to use, somewhat higher (though not significantly) perceived ease of use scores, and higher perceived usefulness scores than those who did not ultimately intend to adopt. Adopters had a larger positive comment to negative comment ratio compared to non-adopters. By the end of four weeks, non-adopters had lower intent to adopt than non-adopters.

Building on Fausset et al. (2013), this study used both quantitative and qualitative measures over a longer period of use. Following users over time is an important approach in understanding technology adoption. As suggested by Rogers (2003), adoption is a process. Accordingly, our study suggests that initial measurements of intent to adopt may not be a very accurate predictor of whether someone will adopt a given technology over an extended time period. Although some people express initial willingness to try a new technology, there are users who will decide to stop after a short period of time (Blanson Henkemans, Rogers, & Dumay, 2011).

Although the quantitative measures did not reveal perceived ease of use as a potential problem with these technologies, diary data suggested that some participants found aspects of the wellness management technology difficult to use. For example, multiple comments were made about difficulties adding foods to the logs from extensive databases. By tracking users’ opinions over time, a more complete understanding of technology adoption is possible.

Similar to Fausset et al. (2013), our diary data suggested perceived usefulness may be a key factor in the decision to adopt a wellness management technology. Some adopters commented on the value of the technology for tracking progress and planning meals, but not one non-adopter made a similar comment. In general, themes that emerged related to elements that influence perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, such as the accuracy of the technologies. Additionally, while perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness do play a role in technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003), intent to adopt may be more diagnostic in highlighting differences between adopters and non-adopters. However, the current participants were generally in good health and further research is needed to determine if these influences may be different depending on health, especially in populations with chronic diseases.

Encouraging for wellness management technology designers is that all older adults in our sample were neutral to high in their initial intent to adopt. This suggests that if the benefits emerge over usage while costs (e.g., effort) are minimized, older adults may be excellent candidates for consumers. Human factors guidelines in design and implementation could improve the benefit-cost ratio (Preusse, Mitzner, Fausset, & Rogers, 2014). Ideally, these technologies should make data entry, such as through food databases, and data corrections, such as accuracy in step-counts, faster and more intuitive for older adult users. In addition to minimizing time and effort costs, especially for new users, these technologies should also communicate potential usefulness to target users, for example through promotional videos showing older adults as users tracking their nutritional intake.

Indeed, older adults are already tracking their health, just not often through these sorts of technologies (Fox & Duggan, 2013). Interestingly, one participant who at the end of the study intended to adopt, mentioned on his first day of use that he could have written out the food and activity logs much quicker. This suggests that by showing benefits over time, older adults may decide to switch from keeping track of their diet and exercise from paper and pencil or in their heads to wellness management technologies. Further investigation is needed to better understand the underlying opinions regarding wellness management technology adoption. In particular, a better understanding of the underlying opinions of these technologies for individuals in poorer health is needed.

ACKNOWELDGEMENT

This research supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging) Grant P01 AG17211 under the auspices of the Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (CREATE; www.create-center.org).

This research was conducted in coordination with the Georgia Tech HomeLab (homelab.gtri.gatech.edu), which provides the capability to conduct in-home research that supports the development of innovative technologies that promote health, wellness, and independence for older adults. HomeLab brings together a multidisciplinary team of scientists and engineers and a community of older adults interested in participating in research. We thank Brad Fain, Hannah Jahant, Chandler Price, and Mallory Skelton for their help and support on this project.

REFERENCES

- Albaina IM (2008). Persuasive technology to motivate elderly individuals to walk: A case study. (Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands: ). [Google Scholar]

- Barg-Walkow LH, Mitzner TL, & Rogers WA (2014). Technology Experience Profile (HFA-TR-1402). Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology, School of Psychology, Human Factors and Aging Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Becker H, Stuifbergen A, Oh HS, & Hall S (1993). Self-rated abilities for health practices: A health self-efficacy measure. Health Values: The Journal of Health Behavior, Education & Promotion, 17(5), 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Blanson Henkemans O, Rogers W, & Dumay A (2011). Personal characteristics and the law of attrition in randomized controlled trials of eHealth services for self-care. Gerontechnology, 10(3), 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, & Grumbach K (2002). Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(19), 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Charness N, Dijkstra K, Fisk AD, Rogers WA, & Sharit J (2006). Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement Demographic and Background Questionnaire (CREATE-TR-2006–02). University of Miami: CREATE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S, & Kramer AF (2003). Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults A meta-analytic study. Psychological Science, 14(2), 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FD (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar]

- Elward K, & Larson E (1992). Benefits of exercise for older adults. A review of existing evidence and current recommendations for the general population. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 8(1), 35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausset CB, Mitzner TL, Price CE, Jones BD, Fain BW, & Rogers WA (2013). Older adults’ use of and attitudes toward activity monitoring technologies. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 57th Annual Meeting (pp. 1683–1687). Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk AD, Rogers WA, Charness N, Czaja SJ, & Sharit J (2009). Designing for older adults: Principles and creative human factors approaches (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox S & Duggan M (2013). Tracking for Health. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Tracking-for-Health. [Google Scholar]

- Freid VM, Bernstein AB, & Bush MA (2012). Multiple chronic conditions among adults aged 45 and over: trends over the past 10 years. Women, 45, 64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz B, & Lauckner C (2012). Diabetes management via mobile phones: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health, 18(3), 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Ahn DK, Oliveira BM, Atienza AA, Castro CM, & Gardner CD (2008). Promoting physical activity through hand-held computer technology. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(2), 138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland D & Ingledew DK (1997). The measurement of exercise motives: Factorial validity and invariance across gender of a revised Exercise Motivations Inventory [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner TL, McBride SE, Barg-Walkow LH, & Rogers WA (2013). Self-management of wellness and illness in an aging population In Morrow DG (Ed.), Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics (Vol. 8, pp. 277–333). Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. [Google Scholar]

- Preusse KC, Mitzner TL, Fausset CB, & Rogers WA (in press). Activity monitoring technologies and older adult users: Heuristic analysis and usability assessment Proceedings of the 2014 Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care: Leading the Way. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society [Google Scholar]

- Rejeski WJ, & Mihalko SL (2001). Physical activity and quality of life in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(suppl 2), 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th edition). New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, Bell RC, Croteau KA, De Bourdeaudhuij I, … Lutes LD (2011). How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition Physical Activity, 8(1), 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, & Davis FD (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar]

- Wallston KA, Wallston BS, & DeVellis R (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Education & Behavior, 6(1), 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]