Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Family members of ICU survivors report long-term psychological symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We describe patient and family-member risk factors for PTSD symptoms among family members of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

DESIGN:

Prospective cohort study of family members of ARDS survivors.

SETTING:

Single tertiary care center in Seattle, Washington.

SUBJECTS:

From 2010 to 2015, we assembled an inception cohort of adult ARDS survivors who identified family members involved in ICU and post-ICU care. 162 family members enrolled in the study, corresponding to 120 patients.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

Family members were assessed for self-reported psychological symptoms 6 months after patient discharge using the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7). The primary outcome was PTSD symptoms, and secondary outcomes were symptoms of depression and anxiety. We used clustered multivariable logistic regression to identify patient and family-member risk factors for psychological symptoms. PTSD symptoms were present in 31% (95%CI 24–39%) of family participants. Family member risk factors for PTSD symptoms included preexisting mental health disorders (aOR 3.22, 95%CI 1.42–7.31), recent personal experience of serious physical illness (aOR 3.07, 95%CI 1.40–6.75), and female gender (aOR 5.18, 95%CI 1.74–15.4). Family members of previously healthy patients (Charlson index of zero) had higher frequency of PTSD symptoms (aOR 2.25, 95%CI 1.06–4.77). Markers of patient illness severity were not associated with family PTSD symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS:

The prevalence of long-term PTSD symptoms among family members of ARDS survivors is high. Family members with preexisting mental health disorders, recent experiences of serious physical illness, and family members of previously healthy patients are at increased risk for PTSD symptoms.

Keywords: family, PTSD, psychological outcomes, critical illness, ARDS

Introduction

Family members of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are often closely involved in their relatives’ ICU and post-ICU care.1,2 During patients’ critical illness, they may provide informal caregiving, communicate with clinicians, and serve as surrogate decision-makers.1 Following critical illness, family members provide physical and emotional support.2–4 These experiences place family members at risk of psychological symptoms, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety.5–7 Although some psychological symptoms may be expected, others might compromise family members’ personal health or impact caregiving.8,9 In order to improve long-term outcomes for ARDS survivors and their family members, we must better understand the burden and risk factors for psychological symptoms amongst family members.10

Studies of bereaved ICU family members have described risk factors for long-term psychological symptoms, including female gender, low educational attainment, and spousal relationship.11–14 PTSD symptoms have also been described in mixed cohorts of bereaved and non-bereaved ICU family members.15–17 Fewer studies have focused on psychological symptoms in family members of ICU survivors. Female gender, high-risk behaviors, and patient functional dependency have been associated with depression symptoms in family members of ICU survivors.5,6 Less is known about risk factors for family member symptoms of PTSD or anxiety. Addressing this knowledge gap will allow investigators to identify interventions to improve family outcomes.

In this study, we describe patient- and family-member-based risk factors for long-term PTSD symptoms among family members of ARDS survivors. We hypothesize that severity of patient illness, absence of preexisting patient comorbidities, preexisting mental health disorders in family members, and family members’ personal experiences of physical illness may be associated with PTSD symptoms.

Methods

Study Design and Study Site

In this single-center prospective cohort study, we examined family member surveys and patient data to identify risk factors for PTSD symptoms among family members. The study was conducted in the medical and trauma/surgical ICUs of a tertiary care and level I trauma center in Seattle, Washington. These ICUs share an open visitation policy, and families are encouraged to participate in bedside rounds. The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (#36942).

Participants

Between September 2010 and December 2015, we assembled an inception cohort of patients with ARDS hospitalized at the study site. All English-speaking, adult (age≥18 years) patients mechanically ventilated for ≥48 hours who survived to ICU discharge were screened for ARDS by the research team,18 and then for presence of a valid mailing address in the electronic health record (EHR). Patients were excluded for pregnancy, incarceration, or primary admitting diagnosis of head trauma or stroke.

Patient participants were invited to enroll by mail 3 months after discharge. Patients received a study description, consent form, $10 incentive, and study questionnaire. The questionnaire asked patients to identify adult family members most involved in their ICU and post-ICU care, and also their legal next-of-kin.19 Family members were invited to enroll using the same recruitment methods.

Data Collection

Family members received a mailed study packet with study questionnaires followed by a reminder postcard and up to 3 repeat mailings for non-responders. Eligible participants could opt-out of further contact by mail or phone. Questionnaires included demographic questions, standardized measures of mental and physical health prior to the patient’s hospitalization, and standardized measures of current self-reported psychological symptoms.

Demographic variables included age, gender, level of education, and relationship to the patient. Family members’ pre-ICU physical and mental health were retrospectively assessed using the Mental Health Visits and Medications Questionnaire. This questionnaire contains 8 items evaluating preexisting mental health and medical problems during the year prior to the patient’s hospitalization, and has been used in prior studies of hospitalized patients and caregivers.13,14,20–22 Respondents who took prescription mood medications or were cared for by mental health providers were classified as having a preexisting mental health disorder. Respondents who reported inpatient hospitalizations, accidents/injuries requiring medical attention, or admissions to nursing or rehabilitative facilities were classified as having experienced recent serious physical illness.

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C),23–26 a 17-item self-report questionnaire that elicits graded responses (from 1 “not at all” to 5 “extremely”) for the intrusive, avoidant, and arousal PTSD symptom clusters experienced during the prior month. Scores are summed (range 17–85); higher scores indicate a greater burden of PTSD symptoms.27 Symptoms of depression were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),28–33 which assesses the frequency of depression symptoms (from 0 “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day”) over the preceding two weeks. Scores are summed (range 0–27); higher scores indicate more depression symptoms.33 Symptoms of anxiety were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), which uses similar response options to the PHQ-9. Scores are summed (range 0–21); higher scores indicate more anxiety symptoms.34,35

Patients’ illness characteristics obtained from the EHR included demographics, admitting diagnosis, Charlson comorbidity index,36 admission APACHE II score,37 length of ICU stay, and post-ICU disposition. These characteristics were abstracted by trained research coordinators, with 10% of charts co-abstracted by the principal investigator (EK) to ensure data quality.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was family member self-reported PTSD symptoms, defined by a PCL-C score ≥ 35, which is considered suggestive of significant PTSD symptoms in the general population.27 Secondary outcomes were family members’ self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms, defined by PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores ≥ 10, which are suggestive of at least mild-to-moderate depression or anxiety symptoms, respectively.33,35

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the prevalence of PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms. To evaluate associations between potential risk factors and psychological symptoms, we used multivariable logistic regression with the primary outcome of PTSD symptoms (PCL-C ≥ 35). We began with the primary exposure of family member preexisting mental health disorders, and adjusted a priori for family member age, gender, level of education, and legal next-of-kin relationship.5,12–14,17 We then used forward stepwise regression with a significance level of p≤0.10 for addition to the model to evaluate associations between characteristics of family members (relationship to patient, recent experiences of physical illness) and patients (age, Charlson index, admission APACHE II, length of stay, post-ICU disposition). Covariates demonstrating significant collinearity with already-included exposures were discarded. Secondary outcomes of depression and anxiety symptoms were analyzed using the final model. All analyses were clustered by patient to allow for intragroup correlation, with some patients having more than one enrolled family member. Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

To handle missing outcome measure data, we designed an a priori algorithm for imputation of responses. When a participant skipped one item from the PCL-C, PHQ-9 or GAD-7, the missing value was imputed by substituting the mean of all items completed by that individual on that measure. Outcome measures missing more than one value were excluded.

Results

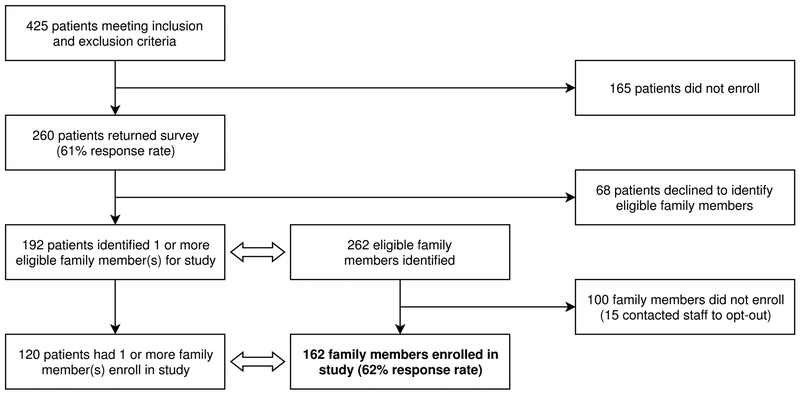

From an inception cohort of 425 eligible ARDS survivors, 260 (61%) enrolled in the patient cohort. Patient participants identified 262 eligible family members; 162 (62%) enrolled in the study. These family members corresponded to 120 members of the patient cohort (Figure 1). Family member surveys were completed at a median of 5.9 months after patient discharge (IQR 5.0–7.0; range 3.6–13.6).

Figure 1.

Patient and participant screening, recruitment, and response.

As non-responders had no engagement with study staff, we have no data on non-responders apart from their relationship to the patient. We assessed whether patient characteristics were associated with family non-response by comparing patient demographics, diagnosis, Charlson index, APACHE II, length of stay, and post-ICU disposition between patients of responding vs. non-responding family members. Family member non-response was more frequent among patients of minority race/ethnicity (73% vs. 50%, p<0.01). No other differences between the patients of family responders vs. non-responders were identified.

Most returned surveys were complete: 93% (151/162) of subjects answered all PCL-C items; 5 subjects omitted a single response; and, 6 subjects omitted more than one item and were excluded. Data completeness for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 was similar.

Characteristics of patients associated with family participants are shown in Table 1. Patients had a mean age at admission of 54.8 years (SD 15.7). A slight majority of patients were male (62%); most were white and non-Hispanic (90%). Over half of patients (58%) had a Charlson comorbidity index of zero. About one-third of ARDS cases were attributable to trauma, and an additional third were attributable to sepsis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of ARDS survivors.

| Patient Characteristic | Patients of family member(s) with PTSD symptoms n=48 a |

Patients of family member(s) without PTSD symptoms n=86 a |

All patients N=120 a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years at admission, mean (SD) | 53.9 (16.4) | 53.7 (16.6) | 54.8 (15.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 16 (33) | 37 (43) | 45 (38) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school, n (%) | 3 (7) | 7 (8) | 9 (8) |

| High school diploma or GED, n (%) | 5 (11) | 27 (32) | 30 (26) |

| Some college or trade school, n (%) | 25 (54) | 33 (39) | 53 (45) |

| College degree or higher, n (%) | 13 (28) | 17 (20) | 25 (21) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White and non-Hispanic, n (%) | 45 (96) | 74 (88) | 105 (90) |

| Non-white or Hispanic, n (%) | 2 (4) | 10 (12) | 12 (10) |

| Employment prior to admission | |||

| Employed, n (%) | 28 (58) | 38 (47) | 56 (49) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 2 (4) | 12 (15) | 14 (12) |

| Retired, n (%) | 12 (25) | 23 (28) | 30 (26) |

| Disabled, n (%) | 6 (12) | 8 (10) | 14 (12) |

| Primary ARDS risk factor | |||

| Trauma, n (%) | 22 (46) | 28 (33) | 44 (37) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 13 (27) | 30 (35) | 40 (33) |

| Other, n (%) | 13 (27) | 28 (33) | 36 (30) |

| Length of ICU stay in days, median (IQR) | 14 (9–21.5) | 13 (8–21) | 13 (8–21.5) |

| APACHE II score at admission, mean (SD) | 23.8 (7.4) | 23.2 (7.5) | 23.2 (7.7) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| Charlson index 0, n (%) | 32 (67) | 48 (56) | 69 (58) |

| Charlson index 1, n (%) | 5 (10) | 23 (27) | 28 (23) |

| Charlson index 2, n (%) | 7 (15) | 11 (13) | 15 (12) |

| Charlson index 3+, n (%) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 8 (7) |

| Post-ICU disposition | |||

| Home, n (%) | 24 (51) | 40 (47) | 55 (46) |

| Rehabilitation hospital, n (%) | 5 (11) | 8 (9) | 12 (10) |

| Long-term acute care, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Skilled nursing facility, n (%) | 18 (38) | 35 (41) | 48 (40) |

17 patients had multiple family members enrolled who differed in their PTSD symptoms; these patients are represented in both columns. 3 patients’ family members did not complete the PCL-C questionnaire, but did complete the PHQ-9 or GAD-7.

APACHE II: Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II score. ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome. GED: General Educational Development (high school equivalency diploma). SD: standard deviation. IQR: interquartile range. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Characteristics of family member participants are shown in Table 2. Mean age at the time of patient admission was 51.5 years (SD 14.7). Most family members were female (73%) and white/non-Hispanic (91%). 64% of family members were identified as the patient’s legal next-of-kin.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of family members of ARDS survivors.

| Family Member Characteristic | Family members with complete PCL-C N=156 |

All family members N=162 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD symptoms (PCL-C ≥ 35) n=49 |

No PTSD symptoms (PCL-C < 35) n=107 |

||

| Age in years at admission, mean (SD) | 51.6 (13.9) | 51.1 (15.3) | 51.5 (14.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 44 (89) | 68 (64) | 118 (73) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school, n (%) | 3 (6) | 12 (11) | 15 (9) |

| High school diploma or GED, n (%) | 15 (32) | 18 (17) | 35 (22) |

| Some college or trade school, n (%) | 14 (30) | 40 (38) | 55 (35) |

| College degree or higher, n (%) | 15 (32) | 35 (33) | 53 (34) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White and non-Hispanic, n (%) | 46 (94) | 94 (90) | 145 (91) |

| Non-white or Hispanic, n (%) | 3 (6) | 10 (10) | 14 (9) |

| Employment at time of survey | |||

| Employed, n (%) | 24 (53) | 66 (66) | 93 (62) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 10 (22) | 13 (13) | 23 (15) |

| Retired, n (%) | 6 (13) | 16 (16) | 24 (16) |

| Disabled, n (%) | 5 (11) | 5 (5) | 10 (7) |

| Relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse, n (%) | 24 (49) | 37 (36) | 63 (40) |

| Adult child, n (%) | 8 (16) | 25 (24) | 33 (21) |

| Sibling, n (%) | 3 (6) | 12 (12) | 16 (10) |

| Parent, n (%) | 6 (12) | 17 (16) | 25 (16) |

| Other, n (%) | 8 (16) | 13 (12) | 22 (14) |

| Washington State legal next-of-kin, n (%) | 37 (76) | 63 (59) | 103 (64) |

| Years known to patient, mean (SD) | 31.0 (14.8) | 34.2 (16.5) | 33.3 (15.9) |

| Preexisting mental health disorder | 23 (47) | 22 (21) | 46 (28) |

| Recently experienced serious physical illness | 23 (47) | 30 (28) | 56 (35) |

| Months from admission to survey return, median (IQR) | 6.1 (5.0–7.0) | 5.8 (5.1–6.9) | 5.9 (5.0–7.0) |

ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome. GED: General Educational Development (high school equivalency diploma). IQR: interquartile range. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder. PCL-C: Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist – civilian version. SD: standard deviation.

Among family members, 28% (46/162) had preexisting mental health disorders, as defined by self-reported prescription mood medications (83%), encounters with outpatient mental health providers (48%), or mental health hospitalizations (7%) during the year prior to the patient’s hospitalization. Additionally, 35% (56/162) of family members had experienced recent serious physical illness, as defined by inpatient hospitalizations (46%), accidents/injuries requiring medical attention (68%), or admission to nursing or rehabilitative facilities (9%) in the preceding year.

Symptoms of PTSD were present in 31% (95%CI 24–39%) of family participants. Depression symptoms were present in 21% (95%CI 15–29%) and anxiety symptoms in 18% (95%CI 13–25%). Family members with preexisting mental health disorders reported a higher prevalence of psychological symptoms in at least one of the three outcome measures (63% vs. 33%, unadjusted RD 30% [95%CI 14–47%], p<0.01).

In multivariable analysis adjusted for family member age, education, and legal next-of-kin relationship, we identified several independent risk factors associated with PTSD symptoms (Table 3). PTSD symptoms were more frequently reported by family members with a preexisting mental health disorder (adj. risk 44% vs. 20%, p<0.01), recent experience of physical illness (42% vs. 19%, p<0.01), female gender (35% vs. 9.6%, p<0.01), and by family members of patients with no medical comorbidities prior to their ARDS (32% vs. 17%, p=0.03).

Table 3.

Independent risk factors for PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms in family members of ARDS survivors.

| Patient and Family Member Characteristics | Family member PTSD symptoms |

Family member depression symptoms |

Family member anxiety symptoms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aORa (95% CI) | p | aORa (95% CI) | p | aORa (95% CI) | p | |

| Family Member Characteristics | ||||||

| Family member had preexisting mental health disorder | 3.22 (1.42, 7.31) | < 0.01 | 4.11 (1.80, 9.34) | < 0.01 | 3.67 (1.39, 9.68) | < 0.01 |

| Family member experienced a recent serious physical illness | 3.07 (1.40, 6.75) | < 0.01 | 2.20 (0.91, 5.29) | 0.08 | 2.21 (0.81, 6.06) | 0.12 |

| Female family member | 5.18 (1.74, 15.4) | < 0.01 | 2.79 (0.73, 10.5) | 0.13 | 3.17 (0.85, 11.8) | 0.08 |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||

| Patient had no comorbidities prior to ARDS admission | 2.25 (1.06, 4.77) | 0.04 | 1.70 (0.70, 4.13) | 0.24 | 1.66 (0.65, 4.28) | 0.29 |

Model adjusted for all listed risk factors, family member age, education, and legal next-of-kin relationship.

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio. ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder. PCL-C: Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist – civilian version. PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression scale. GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.

We evaluated several other potential risk factors for PTSD symptoms in family members including patient age, admission APACHE II, length of stay, and post-ICU disposition. However, addition of these covariates to the multivariable model revealed no evidence of association with the primary outcome (patient age: aOR 1.09 per 10 years, 95%CI 0.87–1.38; APACHE II: aOR 1.12 per 10 points, 95%CI 0.65–1.94; length of stay: aOR 1.01 per ICU day, 95%CI 0.99–1.03; discharge to location other than home: aOR 1.02, 95%CI 0.45–2.29).

In examining independent risk factors for the secondary outcomes of depression and anxiety symptoms, preexisting mental health disorders in family members were independently associated with depression and anxiety symptoms (Table 3). Associations between other examined risk factors (recent physical illness, female gender, absence of patient pre-morbidity) and depression or anxiety symptoms were not statistically significant. Evaluation of additional patient-based covariates (age, admission APACHE II, length of stay, and post-ICU disposition) revealed no associations with depression or anxiety symptoms.

Discussion

Among family members of ARDS survivors, we found a higher prevalence of PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms than reported in the general population.38 Previous studies of PTSD symptoms among ICU family members have also reported higher prevalence of symptoms than general population, although estimates of prevalence vary by study population and outcome measure.11,13–17 Our findings demonstrate that post-ICU PTSD symptoms are not limited to families who experienced death in the ICU. Our finding of substantial depression symptoms in family members of ARDS survivors is also consistent with previous studies of ICU survivors’ caregivers.6,12,13 Our findings support our hypotheses that family member preexisting mental health disorders, recent personal experiences of serious physical illness, and low patient premorbidity are independently associated with family member post-ICU PTSD symptoms. Counter to our hypothesis, markers of the patient’s severity of illness including length of stay, illness severity scores, and discharge location were not associated with family member psychological symptoms.

Our study introduces two important novel risk factors. First, family members of patients without preexisting comorbidities had more PTSD symptoms. Possible explanations include the abrupt introduction of new caregiving or financial pressures, or unanticipated role changes resulting from the patient’s illness. Although our study does not quantify premorbid physical or psychological impairments in patients, we hypothesize that previously healthy patients may suffer a more sudden decrement in health following ARDS, thereby influencing caregivers’ psychological symptoms.

A second novel risk factor identified was that family members who had themselves recently experienced serious physical illness had higher post-ICU PTSD symptoms. This finding illustrates the pertinence of family members’ own lived experiences in their psychological outcomes. It is possible that the stress associated with a serious physical illness may predispose family members to develop PTSD symptoms when exposed to the added stress of a critically ill family member. Alternatively, PTSD symptoms may arise from a family member’s own illness experience irrespective of his/her caregiving role. However, the high prevalence of PTSD symptoms in family members without recent physical illness suggests that the patient’s critical illness plays an important role in the development of family member psychological symptoms.

Other markers of illness severity were not associated with psychological symptoms in family members. Although prior studies of bereaved and non-bereaved family members have found associations between family member PTSD symptoms and patient-based risk factors including age and illness severity,13,16 these associations have not been described in family members of ARDS survivors. In studies of parents of critically ill children, parental PTSD symptoms also do not appear to be associated with illness severity.5,39–42 We hypothesize that differences in disease outcomes, clinical practices, and cultural norms may influence associations between illness severity and PTSD symptoms, and that illness severity factors that clinicians typically consider may not reliably predict family member psychological symptoms.

Our study has several limitations. First, as critical illness occurs unpredictably, we were unable to measure psychological symptoms in family members prior to the patient’s critical illness. However, our findings are consistent with previous studies that report a high burden of psychological symptoms in family members of ARDS survivors.6,15–17 Second, retrospective reporting of preexisting mental health comorbidities may introduce recall bias. To minimize this, our survey framed each question within a clearly delineated timeline. Third, although our response rate is within the range observed in other studies of ICU family members,12–17 it is possible that differential non-response by either patients or their families could introduce sampling bias. It seems likely that individuals with a high burden of psychological symptoms (especially avoidant symptoms of PTSD) would be less likely to respond to surveys. Notably, the prevalence of preexisting mental health disorders among participants is consistent with national estimates,38 and the prevalence of psychological symptoms is consistent with other studies of ICU family members. Additionally, studies examining response bias in family members of seriously ill patients have found that participation is highest among those who are highly engaged with the patient and their care, suggesting that our findings may be most applicable to these family members.43–45 Fourth, there were very few male respondents who reported psychological symptoms in our study. As female gender is associated with both caregiver status and post-ICU psychological symptoms,5,6,11–14 this most likely reflects limitations in sample size. A sensitivity analysis restricted to female respondents revealed similar findings to the primary analysis, although the association between Charlson score and PTSD symptoms was no longer statistically significant. Fifth, as a single-center study conducted in the United States, our findings may not generalize to other settings.

Lastly, we used screening questionnaires to assess self-reported psychological symptoms rather than standard diagnostic methods to diagnose depression, anxiety, or PTSD disease. As it is possible that these self-reported symptoms represent other mental health conditions or even normal coping behaviors, our study is unable to comment on the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder or other psychiatric disorders among respondents. Additionally, discrepancies between clinician-reported vs. self-reported methods of symptom assessment may lead to misclassification. However, findings from studies using structured clinical interviews to examine long-term psychological outcomes of ARDS survivors have largely paralleled studies using self-administered survey instruments;46–48 and while ARDS survivors may have neurocognitive symptoms that could be misattributed to psychiatric diagnoses, family members are more likely to be approximated by the population in whom these instruments were derived.

Conclusions

Family members of ARDS survivors describe long-term symptoms of PTSD at rates higher than that of the general population. Family members with preexisting mental health disorders or recent serious physical illness are at higher risk for PTSD symptoms. Family members of previously healthy patients are also at higher risk for PTSD symptoms. Further studies of family members at high risk are needed to better characterize the causes of these symptoms and identify potential targets for intervention to detect and reduce family member psychological symptoms after critical illness.

Financial support:

This work was supported by NIH T32 HL125195 (Lee) and NIH K23 HL098745 (Kross).

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Lee, Engelberg, Curtis, and Kross received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Lee and Engelberg’s institutions received funding from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (NIH T32 HL125195 to Dr. Lee). Drs. Engelberg and Kross’ institutions received funding from the NHLBI (NIH K23 HL098745 to Dr. Kross). Dr. Engelberg’s institution also received funding from Cambia Health Foundation, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the NIH. Dr. Hough disclosed that she does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Davidson JE. Family-centered care: meeting the needs of patients’ families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29(3):28–34; quiz 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox CE, Docherty SL, Brandon DH, et al. Surviving critical illness: acute respiratory distress syndrome as experienced by patients and their caregivers. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2702–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JI, Herridge MS, Tansey CM, et al. Well-being in informal caregivers of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haines KJ, Denehy L, Skinner EH, et al. Psychosocial outcomes in informal caregivers of the critically ill: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1112–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, et al. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care. 2016;20:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans RL, Bishop DS, Haselkorn JK. Factors predicting satisfactory home care after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(2):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinedinst NJ, Gebhardt MC, Aycock DM, et al. Caregiver characteristics predict stroke survivor quality of life at 4 months and 1 year. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(6):592–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kross EK. The importance of caregiver outcomes after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1149–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kross EK, Gries CJ, Curtis JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder following critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):875–887, ix-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, et al. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(4):795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, et al. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Informed consent—Persons authorized to provide for patients who are not competent—Priority, Revised Code of Washington 7.70.065.

- 20.Zatzick D, Russo J, Grossman DC, et al. Posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and recurrent traumatic life events in a representative sample of hospitalized injured adolescents and their parents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(4):377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Muller HG, et al. Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):941–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall GN, Schell TL. Reappraising the link between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptom severity: evidence from a longitudinal study of community violence survivors. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(4):626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald SD, Calhoun PS. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(8):976–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, et al. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe B, Grafe K, Kroenke K, et al. Predictors of psychiatric comorbidity in medical outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):764–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turvey CL, Willyard D, Hickman DH, et al. Telehealth screen for depression in a chronic illness care management program. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(1):51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(2):131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, et al. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(6):547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bronner MB, Knoester H, Bos AP, et al. Follow-up after paediatric intensive care treatment: parental posttraumatic stress. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(2):181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw RJ, Bernard RS, Deblois T, et al. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(2):131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(3):230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long AC, Downey L, Engelberg RA, et al. Understanding Response Rates to Surveys About Family Members’ Psychological Symptoms After Patients’ Critical Illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(1):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oldenkamp M, Wittek RP, Hagedoorn M, et al. Survey nonresponse among informal caregivers: effects on the presence and magnitude of associations with caregiver burden and satisfaction. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Potential for response bias in family surveys about end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2009;136(6):1496–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, Krauseneck T, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinert C, Meller W. Epidemiology of depression and antidepressant therapy after acute respiratory failure. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(5):399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):512–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]