INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a diverse group of neoplasms arising from cells in the diffuse neuroendocrine system. At least 17 different types of neuroendocrine cells are found in the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract.1 In the pancreas, they are located in the islets of Langerhans, which were first described by their namesake in 1869.2 There are five well-defined pancreatic islet cell types which produce biologically active peptides including insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, and ghrelin.3 Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are also capable of hormone production and are believed to arise from islet cells or, more likely, their precursors.1,4 Tumors that overproduce hormones may be associated with distinct clinical syndromes and are referred to as functional; those that do not secrete hormones, secrete them in minimal quantities, or secrete peptides that do not result in an obvious syndrome (e.g. pancreatic polypeptide) are termed non-functional. PNETS may produce multiple hormones5 and are referred to by the name of the hormone whose effects dominate the clinical picture appended with “-oma”, as in insulinoma or gastrinoma.

History

The first report of a PNET was by Albert Nicholls, who described an adenoma arising from the islets of Langerhans in 1902.6 The term karzinoide (carcinoid) was introduced in 1907 by Siegfried Oberndorfer to describe small tumors of the distal ileum resembling carcinoma, but with less malignant potential.7 Although the term originally referred specifically to ileal tumors, over the next half century the definition would be expanded until nearly any NET could be referred to as a carcinoid, regardless of its primary site.8 In 1924, Seale Harris described several patients with symptoms of hypoglycemia, which the authors attributed to hypersecretion of insulin by the pancreas.9 Convincing evidence of insulinoma was first presented by Wilder et al. in 1927, who reported a patient with recurrent hypoglycemic episodes who was found at exploratory surgery to have an unresectable distal pancreatic mass. Autopsy of the same patient revealed nodal and liver metastases, and the tumor cells were noted to bear a “striking” resemblance to islets of Langerhans. Further evidence that the tumor was an insulinoma was provided when the effect of tumor extract injected in rabbits mimicked that of insulin.10 Two years after this report, Roscoe Graham enucleated a 1.5 cm insulinoma from the pancreas of a patient suffering from recurrent hypoglycemic episodes, successfully curing her disease.11 In the decades following the initial reports of hyperinsulinism and insulinoma, syndromes associated with oversecretion of various other peptides by islet cell tumors were described, although the responsible hormone was not always correctly identified until later: serotonin in 1931, glucagon in 1942, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in 1950, gastrin in 1955, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) in 1958, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) in 1973, somatostatin in 1977, growth hormone releasing factor (GRF) in 1978, neurotensin in 1981, and cholecystokinin (CCK) in 2013.12–23

Epidemiology

Pancreatic NETs have an approximate incidence of 0.5 per 100,000 persons per year and account for fewer than 10% of all NETs.24,25 The mean age at diagnosis is 57–58 years, and the peak incidence is in the seventh decade.26–29 At least 70% of these tumors are non-functional, and the most common functional PNETs are insulinomas, followed by gastrinomas.29–32 Together, these three subtypes account for the large majority of PNETs. The incidence of other tumors, such as VlPomas, glucagonomas and somatostatinomas, is not well defined, but they are significantly rarer.31,32 Most PNETs are malignant, and upwards of 60% of patients will have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.1,26,27 Insulinomas, which are benign in 90% of cases, are the exception to this rule; as a consequence, their incidence is frequently underestimated in population-based studies which use data from cancer registries, such as the SEER database.24,29,31,32 The majority of PNETs are sporadic, but as many as 10–20% are associated with inherited cancer syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), or glucagon cell hyperplasia and neoplasia.32–37 Of these, MEN1 is the most frequently associated with PNETs.

Despite the high frequency of metastases, the prognosis of patients with PNETs is favorable, particularly when comped to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The median overall survival for patients in the SEER database diagnosed with PNETs between 1973 and 2012 was 3.6 years. However, over this time period there has been significant improvement in survival, particularly for patients with advanced stage disease.24,26 The median overall survival for patients with metastatic PNETs is now 5 years, and for patients with surgically resected, non-metastatic tumors the 20-year disease specific survival is just over 50%.24,38

PRESENTATION

The presentation of PNETs varies considerably. When present, the symptoms of non-functional tumors are generally non-specific and related to tumor mass effect, but these tumors are increasingly being detected incidentally on imaging prior to developing symptoms.39,40 In contrast, functional tumors are frequently associated with dramatic hormonal syndromes leading to an earlier diagnosis and improved prognosis.28 The clinical presentations of PNET subtypes are summarized in table 1.18,29–32,41–46 Despite the stark differences in presentation, the diagnostic workup and treatment of functional and non-functional tumors is largely similar.1,5,45 While the majority of PNETs occur sporadically, they may also arise in association with several hereditary cancer syndromes, the characteristics of which are shown in table 2.33,34,36,47–52

Table 1:

| Clinical Presentation of PNET Subtypes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor | Hormone | Symptoms |

| Nonfunctional PNET | Varies (Pancreatic polypeptide, chromogranin A, others in small quantities) | Asymptomatic, abdominal/back pain, nausea/vomiting, pancreatitis, obstructive jaundice |

| Insulinoma | Insulin | Hypoglycemic symptoms (tremor, palpitations, anxiety, hunger, cognitive impairment, seizure, coma), fasting hypoglycemia, rapid correction with glucose (Whipple’s triad) |

| Gastrinoma | Gastrin | Severe, medically refractory peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux, diarrhea (Zollinger Ellison-Syndrome) |

| VIPoma | Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) | Watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, achlorhydria (WDHA syndrome, pancreatic cholera or Verner Morrison Syndrome) |

| Glucagonoma | Glucagon | Necrolytic migratory erythema, weight loss, diabetes mellitus, diarrhea, venous thrombosis |

| Somatostatinoma | Somatostatin | Diabetes, gallstones, steatorrhea, weight loss |

| Pancreatic Carcinoid | Serotonin, tachykinins | Flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasm, valvular heart disease (carcinoid syndrome) |

| ACTHoma | Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) | Obesity, facial plethora, round face (moon facies), hirsutism, hypertension, bruising, fatigue, depression, dorsal fat pad, glucose intolerance, stria, proximal weakness, menstrual irregularities, decreased fertility (Cushing’s syndrome) |

| GRFoma | Growth hormone-releasing factor (GRF or GHRF) | Coarse facial features, enlarged hands and feet, macroglossia, deepening voice, skin thickening, sleep apnea, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, fatigue, weakness (Acromegaly) |

| PTHrPoma | Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) | Nephrolithiasis, weakness, bone pain, nausea, constipation, polyuria, depression (Hypercalcemia) |

Table 2:

Characteristics of hereditary cancer syndromes associated with PNETs. Data from references 33, 34, 36, 47-52.

| Hereditary Cancer Syndromes Associated with PNETs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syndrome | Gene | Inheritance | Incidence of PNETs | Other Characteristics |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 | MEN1 | Autosomal Dominant | 20–70% symptomatic PNET, nonfunctional most common followed by gastrinoma, nearly 100% develop multiple pancreatic microadenomas | Parathyroid hyperplasia (95–100%), pituitary tumors (30–50%), angiofibromas (85%), adrenal adenoma (30–40%), Gastric NETs (10–35%) |

| Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome | VHL | Autosomal Dominant | 10–20%, almost all nonfunctional | Retinal and CNS hemangioblastoma (60–80%), renal cell carcinoma (25–70%), pheochromocytoma (10–20%), pancreatic cysts (35–80%), epididymal cystadenoma (25–60%) |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | NF1 | Autosomal Dominant | 0–10%, characteristically ampullary/duodenal somatostatinomas | Café-au-lait macules (99%), neurofibromas (99%), skin fold freckling (85%), Lisch nodules (95%), optic pathway glioma (15%), learning problems (60%) skeletal abnormalities, pheochromcytomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors |

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | TSC1, TSC2 | Autosomal Dominant | Rare, may be functional or nonfunctional | Variable presentation: hamartomas affecting brain, skin, kidneys, and eyes; clasically seizures, developmental delay, and angiofibromas |

| Glucagon cell hyperplasia and neoplasia (Mahvash Syndrome) | GCCR | Autosomal Recessive | 100%, micro- and macro-glucagonomas | Background of glucagon cell hyperplasia |

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PNET ultimately depends on immunohistochemical examination of tumor tissue for confirmation; however, serum markers and imaging also play a critical role in the workup of these tumors. The diagnostic sequence will vary from patient to patient, depending on the presentation; those that present with hormonal symptoms may initially undergo blood testing, while those with non-functional tumors are frequently discovered incidentally on imaging. Regardless of whether biochemical testing precedes imaging or vice versa, patients with PNETs will usually undergo both as part of their diagnostic workup.45,53–55

Biochemical

Laboratory testing involves the use of both biomarkers which are common to most PNETs as well as specific hormones which are secreted by functional PNETs and responsible for the associated syndromes. Chromogranin A (CgA) is an acidic glycoprotein which is found in the secretory granules of all neuroendocrine cells and is among the most widely studied biomarkers for NETs. Serum CgA is elevated in patients with PNETs and is correlated with both disease burden and survival.56,57 A recent meta-analysis on CgA for the diagnosis of NETs reported that the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 73% and 95% respectively; however, these values will vary depending on the specific assay and diagnostic thresholds employed.58 Moreover, clinicians should be aware that elevated CgA may be associated with hypertension, renal dysfunction, treatment with proton-pump inhibitors, and a variety of other benign and malignant diseases unrelated to NETs.59 Pancreastatin, a protein derived from CgA, is another potential biomarker. Although pancreastatin is less sensitive for the diagnosis of NETs than CgA, it is also less susceptible to non-specific elevation, and has been shown to correlate with survival in surgical patients.56,57,60 Other biomarkers which are variably elevated in patients with PNETs include neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin B, and pancreatic polypeptide, though none of these are as widely validated as CgA.56,57 Given the limitations of the available biomarkers, a 51-gene, PCR-based assay (NETest) has recently been developed for the diagnosis and surveillance of NETs. The NETest has superior sensitivity and specificity (94 and 96%, respectively) for PNETs when compared to CgA; however, the test is significantly more expensive than serum testing for other makers.61

Biochemical testing for functional PNETs is directed by symptoms of hormone excess (table 1). Insulinomas present with inappropriately high insulin levels in the setting of hypoglycemia, characterized by Whipple’s triad: hypoglycemic symptoms, low plasma glucose, and resolution of symptoms with administration of glucose. The diagnosis should be confirmed by measurement of elevated insulin, pro-insulin and C-peptide during a hypoglycemic episode, which is often induced by a supervised 72-hour fast. In patients with refractory peptic ulcer disease, the presence of a gastrinoma may be confirmed by serum gastrin > 10 times the upper limit of normal in the setting of gastric pH ≤ 2, or moderately elevated gastrin with a positive secretin or glucagon stimulation test. Proton pump inhibitors should be discontinued for 1–2 weeks prior to measurement of the fasting serum gastrin, during which time acid suppression may be maintained with histamine type 2 blockers. Biochemical testing can help support the diagnosis for other functional PNETs, but given their rarity, there are no universally accepted diagnostic thresholds.46,56,57

Imaging

Imaging studies play a vital role in the diagnosis and workup of PNETs. Computed tomography (CT) is the most commonly used modality, and it has several favorable characteristics when compared to other studies: it is quick, widely available, and provides excellent anatomic definition of the pancreas, and of lymph node or liver metastases (Figures 1, 2). The mean sensitivity of CT for PNETs is 82%.62,63 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a similar mean sensitivity of 79% for primary PNETs, but is significantly more sensitive than CT for the detection of liver metastases, particularly when hepatocyte specific contrast agents are used (e.g. Eovist).63–65 Because of this, MRI is primarily used to evaluate liver tumor burden, particularly in patients for whom hepatic debulking is being considered.53,54

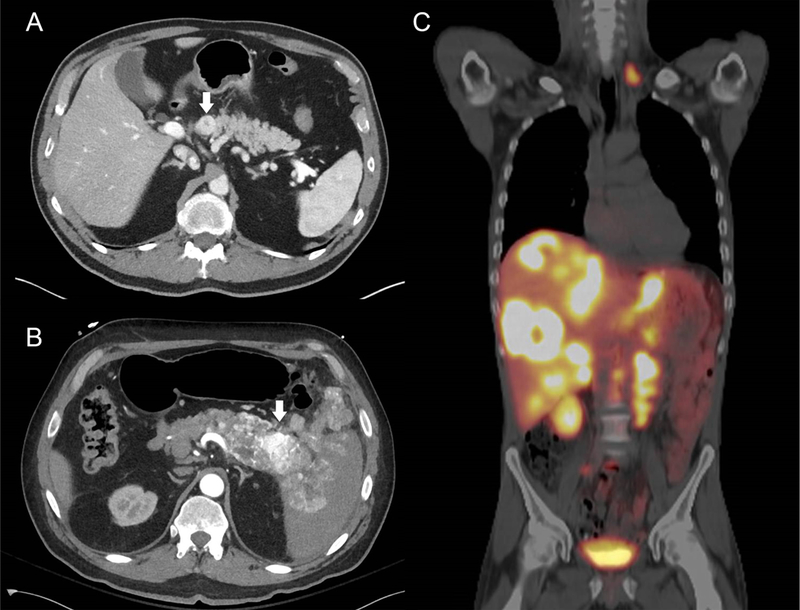

Figure 1:

(A) Arterial phase CT showing a well-circumscribed, enhancing PNET (arrow). (B) Arterial phase CT showing an enhancing PNET (arrow) which is directly invading the spleen and peritoneal cavity. (C) 68Ga-PET allows the entire body to be imaged in a single study. In this patient, who had previously undergone primary PNET resection, extensive metastases are seen in the liver, paraaortic lymph nodes, and left supraclavicular lymph nodes.

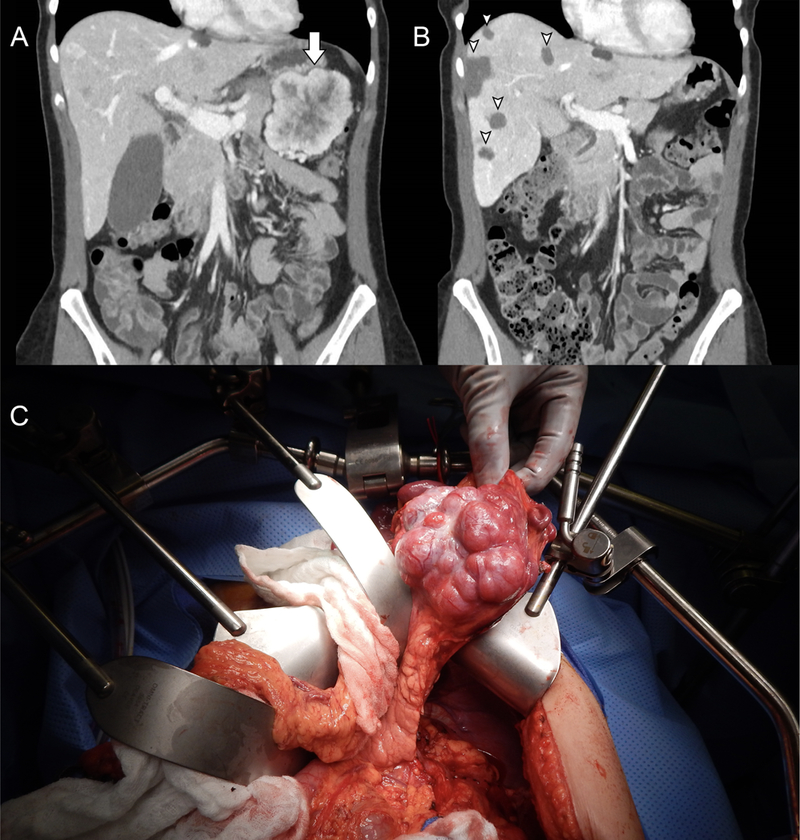

Figure 2:

(A) A large, peripherally enhancing PNET in the tail of the pancreas (arrow), and faintly hyper-and hypoenhancing hepatic metastases are seen on venous phase CT. (B) The postoperative venous phase CT from the same patient following distal pancreatectomy, cholecystectomy and multiple ultrasound-guided, microwave ablations of the liver (arrow heads). (C) Intraoperative appearance of the PNET, within the tail of the pancreas.

Somatostatin receptors are expressed by 80–100% of PNETs, with the exception of insulinomas for which the rate of expression is 50–70%.66 Functional imaging techniques include indium-111 somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (111In-SRS, Octreoscan) and gallium-68 positron emission tomography (68Ga-PET, Netspot), both of which use radiolabeled somatostatin analogs to localize neuroendocrine tumors (Figures 1, 3). 111In-SRS predates 68Ga-PET and has been more widely available; however, due to its quicker acquisition and superior sensitivity, 68Ga-PET is rapidly becoming the functional imaging modality of choice.62,63 A recent meta-analysis found the pooled sensitivity and specificity of 68Ga-PET for the diagnosis of NETs were 93% and 91%, respectively.67 Somatostatin-receptor based imaging will often clearly show distant metastases that are not apparent on conventional imaging, and is very useful for evaluating the entire body in a single scan, or for equivocal lesions on CT or MRI. Although the spatial resolution of 68Ga-PET is superior to that of 111In-SRS, the non-contrasted CT scan which accompanies it does not provide adequate anatomic definition for surgical planning, and a contrast enhanced CT and/or MRI is still required for this purpose. Finally, while fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is widely used to image other malignancies, well-differentiated PNETs are comparatively slow growing and frequently do not show avid glucose uptake. FDG-PET may be used for imaging poorly differentiated tumors, which are also less likely to express somatostatin receptors, and thus less likely to show up well on 68Ga-PET or 111In-SRS.68

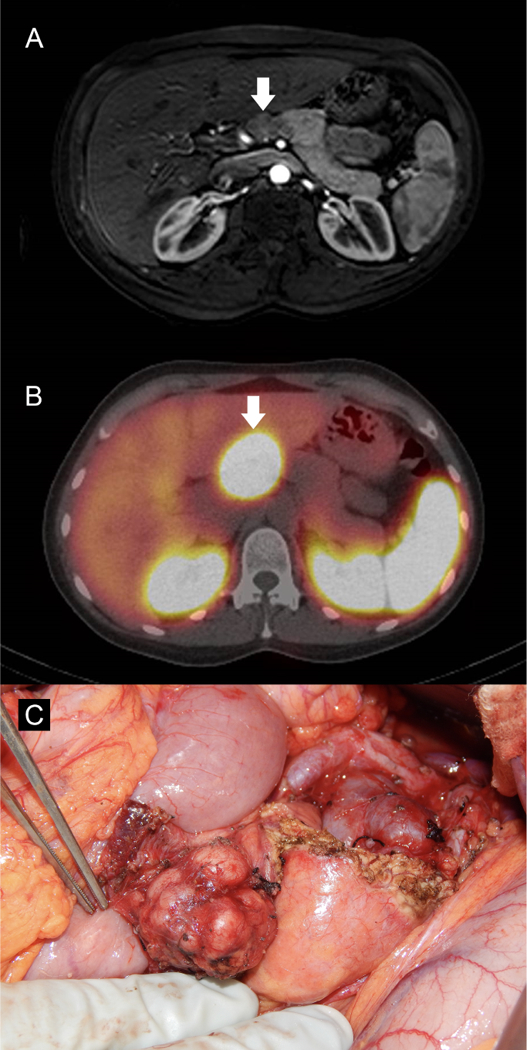

Figure 3:

(A) Hypoenhancing pancreatic neck mass shown on contrast enhanced, T1 weighted MRI (arrow). (B) The same mass shows intense uptake on 111In-SRS (arrow). (C) The mass was well encapsulated and not near the pancreatic duct, thus enucleation and lymphadenectomy were performed.

Patients who present with liver metastases can have symptoms mimicking biliary pathology, in which case the first evidence of a NET may be a liver mass seen on right upper quadrant ultrasound. In these patients, ultrasound guided biopsy of the metastases will confirm the diagnosis. For patients with localized disease, or for those with biochemical evidence of a PNET but no imaging findings (usually small insulinomas or gastrinomas), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be used to visualize the tumor. EUS is the most sensitive test for localizing small PNETs, and it also allows for biopsy via fine needle aspiration (FNA) to confirm the diagnosis.69–71

Pathology

Pancreatic NETs are definitively diagnosed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and histologic examination of the tumor.45,72,73 Tissue may be obtained via EUS and FNA of the pancreatic tumor, by percutaneous core needle biopsy of a liver metastasis, or by surgical resection, although every effort should be made to obtain a tissue diagnosis prior to operation. Immunohistochemical examination of the tumor should include staining for general NET markers, commonly chromogranin and synaptophysin, as well as markers for the site of origin which is particularly important for NET liver metastases of unknown origin. First line IHC markers for this purpose include PAX6 (paired box 6), PAX8 (paired box 8), ISL1 (islet 1), CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and TTF1 (thyroid transcription factor 1). Of these, PAX6, PAX8 and ISL1 serve as pancreatic markers, while CDX2 positivity suggests a small bowel NET and TTF1 indicates a lung NET.72,73 Once the neuroendocrine nature of the tumor has been established, the tumor should be graded by the Ki-67 index (proliferative index) and mitotic rate according to 2017 WHO classification (Table 3).35 Due to the limited amount of material returned by FNA, biopsies obtained using this technique may be more prone to sampling error, and tend to underestimate tumor grade.71,74 PNETs are staged according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, which is shown in table 4, or the ENETS system, which is largely similar.75 A study comparing validity of these two staging systems found them to be equally valid, and that a model which employed the Ki-67 index as a continuous variable was more prognostic than either.76

Table 3:

2017 WHO classification of PNETs. From Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs. 4th Edition ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017, with permission.

| WHO Classification of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Classification/grade | Ki-67 Proliferative index | Mitotic index (per 10 HPF) |

| Well-differentiated NET | ||

| Grade 1 | <3% | <2 |

| Grade 2 | 3–20% | 2–20 |

| Grade 3 | >20% | >20 |

| Poorly differentiated NEC | ||

| Grade 3 | >20% | >20 |

Table 4:

AJCC Staging of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. From Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Edition ed. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing; 2017, with permission.

| AJCC Staging of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors | |

|---|---|

| Primary Tumor (T) | Description |

| TX | Tumor cannot be assessed |

| T1 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, <2 cm |

| T2 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, 2–4 cm |

| T3 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, >4 cm OR tumor invading the duodenum or common bile duct |

| T4 | Tumor invading adjacent organs (stomach, spleen, colon, adrenal) or the wall of large vessels (celiac axis, or the superior mesenteric artery) |

| (m) suffix | Multiple tumors, if the number is known use T(#), if unavailable or too numerous use T(m) |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node involvement |

| N1 | Regional lymph node involvement |

| (sn) suffix | Indicates nodal metastasis identified by sentinal node biopsy only |

| (f) suffix | Indicates nodal metastasis identified by FNA or core needle biopsy only |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1a | Metastases confined to the liver |

| M1b | Metastases in at least 1 extrahepatic site |

| M1c | Both hepatic and extrahepatic metastases |

| Stage | |

| I | T1, N0, M0 |

| II | T2-T3, N0, M0 |

| III | T4, N0, M0, OR Any T, N1, M0 |

| IV | Any T, Any N, M1 |

MANAGEMENT

The treatment of PNETs is a multidisciplinary effort, incorporating surgery, somatostatin analogs (SSAs), targeted therapy, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. A number of recent trials have significantly expanded the therapeutic options, and guidelines for treatment continue to evolve.

Surgery

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for PNETs.31,45,53–55 For patients with localized disease, resection is frequently curative, and even those with distant metastases may derive significant benefit in terms of both symptom control and survival from surgical debulking.77,78 The surgical approach to PNETs depends on the size and location of the tumor, functional status, and presence or absence of distant metastases. Resection of PNETs may be accomplished by pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) or distal pancreatectomy; however, the high morbidity associated with major pancreatic resection combined with the indolent growth of well-differentiated PNETs has led to the adoption of more conservative strategies for small tumors, including enucleation or careful observation.79

Localized Disease

For patients with PNETs confined to the pancreas and regional lymph nodes, treatment options include distal pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, central pancreatectomy, enucleation or observation. All PNETs larger than 2 cm and functional tumors, irrespective of size, should be resected.31,45,53–55 Incidentally discovered PNETs less than 2 cm in size generally exhibit benign behavior,80 and the increasingly frequent diagnosis of small, non-functional PNETs has heightened the controversy over how these tumors should be managed. Single-institutional studies have shown that a nonoperative approach to PNETs smaller than 2 cm is feasible and safe: with an average follow-up of 3 to 4 years, no patients under observation developed metastases and there was no disease specific mortality.81,82 The risks of observation must be balanced against the complication rate for patients undergoing resection of PNETs, which is roughly 30%, and as high as 45% in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy or total pancreatectomy.83 In an effort to avoid these complications, close observation rather than resection may be considered for well-differentiated PNETs less than 2 cm, particularly those confirmed to be low grade by biopsy.46,54 However, recommendations for conservative management should be interpreted with caution: reviews of the SEER and NCDB databases have found that nearly 30% of PNETs under 2 cm had nodal involvement, clearly demonstrating the malignant potential of these tumors, and studies supporting the safety of observation had relatively short follow-up.81,82,84,85 Additionally, a meta-analysis of studies comparing resection to nonsurgical management found that surgery was associated with a significant overall survival benefit, even for PNETs less than 2 cm.79

When the decision to resect is made, enucleation can be considered for tumors which are well-circumscribed, small, well-differentiated, not in close proximity to the pancreatic duct, and without evidence of nodal or distant metastases (Figure 3).45,54,55 The primary advantage of enucleation versus standard pancreatic resection is that the former is associated with a lower rate of postoperative pancreatic insufficiency,55 although this advantage may primarily apply only to pancreatic head masses.86 Additionally, pancreatic enucleation is associated with a similar rate of overall complications, and a higher rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula when compared to standard resection.79,86 Small tumors located in the pancreatic body that are too close to the duct to allow for enucleation may be resected via central pancreatectomy.31,55

Formal pancreatic resection should be performed for tumors that are larger than 2–3 cm, abutting the pancreatic duct, intermediate or high grade, or suspicious for lymph node involvement.31,54,55 Pancreaticoduodenectomy is performed for tumors of the pancreatic head, while tumors in the body or tail are resected via distal pancreatectomy, with or without splenic preservation. Regional lymphadenectomy should be performed as a matter of course with pancreatic resection, as more than 50% of tumors larger than 2 cm will have nodal metastases.46,54,84,87 Recurrence is common even following R0 resection, and is significantly more likely in patients with nodal metastases.46,87

Although several factors, including tumor size greater than 3 to 4 cm, lymph node involvement, tumor vascularity as assessed by CT, and Ki-67 index greater than 5% are associated with an increased likelihood of recurrence,87–89 the optimal frequency and duration of follow-up has not been conclusively established. Surveillance should include imaging with CT or MRI and monitoring of serum markers, particularly if these were elevated preoperatively. Follow-up is initially at 3 to 6 months, and then every 6 to 12 months in the absence of recurrence, but this may be more frequent for high-grade tumors. Given the risk of late recurrence, surveillance should be continued for at least seven years following resection. 68Ga-PET may be used to evaluate equivocal evidence of disease recurrence.53,55

Metastatic Disease

Although patients with distant metastases have generally passed the point at which curative resection may be hoped for, surgery continues to play a central role in their treatment.45,54,55,77,78,90–92 The liver is the overwhelmingly favored site of metastasis for PNETs, accounting for roughly 80% of all metastases, but metastases to the bone, distant lymph nodes, and peritoneal cavity (by direct invasion) are also frequent.93 Significant hepatic replacement by tumor is common, and among patients with metastatic disease, liver failure is the most common cause of death. In contrast to surgery for metastatic adenocarcinoma, the importance of margin status is de-emphasized, and there is a proportionally greater emphasis on preservation of normal hepatic parenchyma. There appears to be minimal benefit associated with R0/R1 resection compared to R2, and even when R0 margins are achieved, eventual disease recurrence is nearly universal.90,91 Numerous surgical series have shown that cytoreductive surgery improves survival and symptomatic control, and historically this has been attempted when 90% cytoreduction was deemed feasible. While a significant majority of patients will be considered unresectable at this threshold, recent studies have shown similar results may be achieved using a lower cutoff of 70% debulking. In order to achieve adequate cytoreduction in patients with numerous, bilobar liver metastases, parenchyma sparing techniques including enucleation and intraoperative, ultrasound-guided ablation are employed (Figure 2), with similar results compared to formal hepatectomy.77,78,92

Cytoreductive surgery is largely accepted as a standard treatment for PNET liver metastases,45,54,55 but precise indications and contraindication for surgery continue to be defined. Broadly, patients should be considered for debulking if they have well-differentiated, grade 1 or 2, metastatic PNETs with less than 50% hepatic replacement (preferably <25%) with a surgically amenable distribution (i.e. not miliary), normal or near-normal liver function, and no evidence of carcinoid heart disease or other major comorbidities. Extra-hepatic metastases should not be considered a contraindication to hepatic debulking, and peritoneal tumor deposits may be resected concurrently.77,92 For patients with extensive liver involvement who are ineligible for hepatic debulking, but are otherwise well-suited for surgery and have no evidence of extra-hepatic disease, liver transplantation appears to offer improved survival.94,95 However, the potential benefits of transplant must be carefully weighed against the scarcity of available grafts and the prospect of lifelong immunosuppression. Moreover, the indications for transplant, as defined by the Milan-NET criteria,95 are very similar to those for hepatic debulking, further complicating patient selection.

Primary tumor resection should be considered in patients with metastatic disease to avoid obstructive complications from the pancreatic mass and further metastatic seeding. In most cases this may be performed simultaneously; the primary exception is for pancreaticoduodenectomy and hepatic ablation, which should be performed in a staged fashion to avoid the theoretical risk of hepatic abscess formation. Even in the case of unresectable metastatic disease, there may be a survival advantage associated with resection of the primary tumor,96 but studies showing a benefit may be prone to selection bias.

Patients with metastatic PNETs are usually treated long-term with somatostatin analogs (SSAs) such as octreotide long-acting-repeatable (octreotide LAR) or lanreotide. The incidence of gallstones in these patients is roughly 50%, significantly higher than the general population. Because the rate of symptomatic biliary disease remains low, prophylactic cholecystectomy is not recommended as a separate operation. However, the risk of developing complications from gallstones is sufficiently elevated to warrant cholecystectomy for patients undergoing primary resection or hepatic cytoreduction, particularly since laparoscopic cholecystectomy may be more difficult after liver surgery.97

Patients with distant metastases should be assumed to have residual tumor following surgery, and should undergo routine biochemical and radiographic surveillance.53,55,90 Patients should be seen in 3 to 6 months following surgery, and then every 6–12 months thereafter. Rapid progression or high-grade disease warrants more frequent surveillance.53,55

Surgical Approach

In general, PNETs are approached via laparotomy to facilitate adequate inspection of the abdomen and debulking of nodal or distant metastases. However, for patients with small localized tumors, distal pancreatectomy or enucleation may be performed laparoscopically with similar outcomes.54,55,98 The role of laparoscopy for metastatic disease is significantly more limited. For patients with PNETs and liver dominant disease, laparoscopic hepatic ablation offers a less invasive alternative to open surgery, with equivalent rates of symptomatic improvement, significantly less morbidity, and a much shorter hospital course.99

Hereditary Syndromes

Many of the principles of management are common between sporadic and inherited PNETs, but there are some special considerations for patients with hereditary syndromes such as MEN-1 and VHL. The surgical management of MEN-1 is covered in Colleen M Kiernan and Elizabeth G Grubbs’ article “Surgical Management of MEN-1 and MEN-2,” in this issue, and this effort will not be duplicated here. The most common pancreatic manifestations of VHL are multiple cysts or serous cystadenomas; however, PNETs are also seen in approximately 10 to 20% of these patients.48,52,55,100 PNETs associated with VHL are frequently multiple and usually non-functional. They are also significantly more likely to be benign than sporadic tumors, and have longer recurrence-free survival following resection.52,100 The risk of progression for PNETs less than 1.5 cm in patients with VHL appears to be very low, and this observation, coupled with the high incidence of multifocal tumors, has led to recommendations against routine resection of asymptomatic PNETs smaller than 1.5 cm.100 Tumors over 3 cm in size, with doubling time less than 500 days, or exon 3 mutations are significantly more likely to metastasize, and therefore, these are indications for resection in VHL patients.101

Liver Directed Therapy

For patients with PNET liver metastases, percutaneous ablation and hepatic artery embolization (HAE) are less invasive options for hepatic cytoreduction compared to surgery. Percutaneous ablation of liver metastases may be performed using radio-frequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation (MWA), or cryoablation.45,54,55,102,103 Direct comparison of each modality for the treatment of PNET liver metastases is difficult due to the limited data in the literature, but extrapolation from the treatment of hepatocellular cancer suggests that outcomes are similar.104,105 MWA has several theoretical advantages over RFA, including faster ablation time and higher intertumoral temperature, and may be superior for larger lesions.104,106 Reported rates of symptomatic improvement and complete ablation are both greater than 90%.103,106 Percutaneous ablation is a reasonable option for the treatment of one or only a few metastases, particularly in patients who are not candidates for surgical resection.45

Hepatic artery embolization takes advantage of the fact that liver metastases are preferentially supplied by the hepatic artery, in contrast to the normal liver parenchyma, which receives much of its blood supply from the portal vein. A catheter is introduced into the hepatic artery and used to deliver therapy locally to the metastatic lesions rather than systemically. Bland HAE is performed using polyvinyl alcohol particles which occlude blood flow to the metastases, inducing hypoxic necrosis. Chemotherapy or radioactive microspheres may also be delivered via the catheter, (chemoembolization and radioembolization, respectively) but at this time no one method has been shown to be definitively superior.107 Patients are admitted following embolization for the management of a constellation of symptoms referred to as post-embolization syndrome. This self-limited syndrome is characterized by fever, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting and occurs in up to 90% of patients following the procedure.108 HAE is indicated for patients with liver dominant disease and a patent portal vein who are not candidates for operative hepatic debulking.45,54,55

Medical Therapy

For patients with localized PNETs, resection is often curative, and no further treatment is needed in the absence of recurrence. For patients with metastases, a number of systemic therapies are available for disease control and symptom palliation. Streptozocin was one of the first agents to show activity against PNETs, but significant side effects and the more recent introduction of less toxic therapies have limited its use.109,110 The antiproliferative properties of SSAs were demonstrated by the CLARINET trial, and due to their favorable side effect profile and inhibition of hormone secretion, long acting SSAs are considered first line therapy for metastatic PNETs.45,54,55,111,112 The tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus are second line treatments which are generally well tolerated and are associated with modest improvements in progression-free survival.113,114 Although previous chemotherapeutic regimens have provided only moderate survival benefits and substantial toxicity, the combination of capecitabine and temozolomide (CAPTEM) has been introduced as a promising new regimen with high objective response rates, improved survival and superior tolerability.115,116 Finally, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) was recently shown to significantly increase progression-free survival in patients with metastatic NETs in the NETTER-1 trial. Although this trial enrolled only patients with midgut NETs, other non-randomized trials have shown similar results in NETs arising from other sites, and PRRT was recently FDA approved for the treatment of all NETs.117 A summary of selected randomized controlled trials for the treatment of PNETs are presented in table 5.

Table 5:

Selected Randomized Controlled Trials for the Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Data from references 53, 109, 112-114, 117.

| Selected Randomized Controlled Trials for the Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Year | Enrollment | Patients Enrolled |

Intervention | Comparator | Progression Free Survival |

Response rate |

| Moertel et al. | 1980 | Unresectable, metastatic PNETs | 84 | STZ 500mg/m^2 + FU 400mg/m^2 daily × 5 days, q6w | STZ 500mg/m^2 daily × 5 days, q6w | Not reported | 63% vs 36% (p<0.01) |

| Raymond et al. | 2011 | Well-differentiated, progressive, unresectable PNETs | 171 | Sunitinib 37.5mg daily | Placebo | 11.4 vs 5.5 months (p<0.001) | 9.3% vs 0% (p=0.007) |

| RADIANT-3 | 2011 | Low or intermediate-grade, unresectable, progressive PNETs | 410 | Everolimus 10mg daily | Placebo | 11.0 vs 4.6 months (p<0.001) | 5% vs 2% (p<0.001) |

| CLARINET | 2014 | Nonfunctioning enteropancreatic NETs or Gastrinoma, SSR+, Unresectable, Ki-67 <10%, 96% stable disease | 204 (45% PNETs) | Lanreotide 120mg q28d | Placebo | 65.1% vs 33.0% at 24 months (p<0.001) | Not reported |

| NETTER-1 | 2017 | Well-differentiated, unresectable, progressive midgut NETs, SSR+, Ki-67 <20% | 229 | 177Lu-Dotatate PRRT 7.4 GBq q8w + Octreotide LAR 30mg q4w | Octreotide LAR 60mg q4w | 65.2% vs 10.8% at 20 months (p<0.001) | 18% vs 3% (p<0.001) |

| E2211 | 2018 | Low or intermediate-grade, unresectable, progressive PNETs | 144 | CAP 750 mg/m^2 daily × 14 days + TMZ 200 mg/m^2 daily × 5 days | TMZ 200 mg/m^2 daily × 5 days | 22.7 vs 14.4 months (p=0.023) | Not reported |

High Grade Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Until recently, all high-grade PNETs, defined by a Ki-67 index over 20%, were classified as neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC); as of the latest WHO classification, they are now divided into high-grade well-differentiated NETs and poorly differentiated NEC (Table 3).35 NEC may be further subdivided into small-cell and large-cell types, but it is unclear how this may affect prognosis or treatment.118,119 With a median survival of 5 to 21 months, these tumors are significantly rarer and more aggressive than well-differentiated, grade 1 and 2 PNETs, and their management is distinct in several respects.118–120 High-grade PNETs are more metabolically active and less likely to express somatostatin receptors. Thus, they are more likely to be detected by FDG-PET and less likely to show uptake on somatostatin receptor based imaging when compared to low-grade tumors.68 On immunohistochemical exam, high-grade tumors are less likely to stain positively for chromogranin, and the typical markers used to assign a site of origin cannot be reliably applied.72,118,119

Surgical resection should be considered for localized, high-grade PNETs and should involve formal oncologic resection (pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy with lymphadenectomy) rather than enucleation.53,54,118 Patients with metastases derive minimal benefit from cytoreduction, and should not be considered for debulking surgery.78 Adjuvant chemotherapy and every 3 month follow-up after resection is recommended due to the high risk of recurrence.53,118 Standard first line chemotherapy for high-grade PNETs consists of cisplatin or carboplatin plus etoposide or irinotecan.53,54,110,118. A number of other agents have been suggested as second line therapy, but none are well validated.53,54,110,118 Among high-grade PNETs, those with a Ki-67 index between 20 and 55% were less likely to respond to platinum based chemotherapy, but were associated with better survival than those with a Ki-67 index over 55%.119 This may reflect the difference between well-differentiated, high-grade PNETs, which typically have Ki-67 indices closer to 20%, and poorly differentiated NECs, which typically have much higher Ki-67 indices. SSAs, everolimus and sunitinib play a limited role in the treatment of high-grade PNETs.

SUMMARY

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are rare malignancies characterized by indolent growth and a propensity to metastasize. The heterogeneity of PNETs is striking: they may present with debilitating hormonal syndromes, diffuse liver metastases, or as asymptomatic, incidentally discovered masses. Similarly, their prognosis runs the gamut from extremely favorable, as is the case with the majority of insulinomas, to dismal for poorly differentiated NEC. Once a PNET is suspected, the diagnostic workup should consist of biochemical testing for NET markers and thorough imaging, which may include CT, MRI, EUS and 68Ga-PET. The diagnosis is confirmed by verifying IHC positivity for NET markers, at which point the tumor is graded according to the WHO classification. Pancreatic tumors which are low-grade, non-functional, stable in size and smaller than 2 cm may be safely observed, while those that do not meet these criteria are indicated for resection. Standard resections include pancreaticoduodenectomy for head masses and central or distal pancreatectomy for body and tail masses. Enucleation is an option for selected tumors smaller than 3 cm which are not abutting the pancreatic duct. Patients with well- differentiated, metastatic PNETs should be considered for surgical debulking, with or without concurrent primary resection, in order to improve survival and symptomatic control. Other options for hepatic cytoreduction include percutaneous ablation, HAE and liver transplant in highly selected patients. A wide variety of systemic therapies are now available for the treatment of metastatic disease including SSAs, everolimus, sunitinib, PRRT and CAPTEM. High grade PNETs carry a grave prognosis and are treated primarily with platinum-based chemotherapy. Formal oncologic resection may be considered for localized disease but does not play a role for metastatic, high-grade tumors.

KEY POINTS

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) arise from islet cells or their precursors and may cause symptoms from mass effect or hormone production.

The standard treatment for localized PNETs is pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy, but enucleation or observation may be considered for small tumors.

Approximately 60% of PNETs will present with metastases, most commonly to the liver.

The treatment for metastatic PNETs is multimodal and includes primary resection, surgical debulking, liver directed therapy, and a variety of systemic treatments.

PNETs carry a significantly more favorable prognosis when compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

SYNOPSIS

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are a diverse group of neoplasms with a generally favorable prognosis. Although they exhibit indolent growth, metastases are seen in roughly 60% of patients. PNETs may produce a wide variety of hormones which are associated with dramatic symptoms, but the majority are non-functional. The diagnosis and treatment of these tumors is a multidisciplinary effort, and management guidelines continue to evolve. This review provides a concise summary of the presentation, diagnosis, surgical management, and systemic treatment of PNETs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the T32 grant CA148062–0 (AS) and SPORE grant P50 CA174521–01 (JH)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Aaron T. Scott, Email: aaron-scott@uiowa.edu.

James R. Howe, Email: james-howe@uiowa.edu.

References

- 1.Schimmack S, Svejda B, Lawrence B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The diversity and commonalities of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(3):273–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langerhans P Beiträge zur mikroskopischen Anatomie der Bauchspeicheldrüse. Berlin: Buchdruckerei von Gustav Lange; 1869. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Da Silva Xavier G The Cells of the Islets of Langerhans. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018;7(3):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vortmeyer AO, Huang S, Lubensky I, Zhuang Z. Non-islet origin of pancreatic islet cell tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1934–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modlin IM, Moss SF, Gustafsson BI, Lawrence B, Schimmack S, Kidd M. The archaic distinction between functioning and nonfunctioning neuroendocrine neoplasms is no longer clinically relevant. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(8):1145–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholls AG. Simple Adenoma of the Pancreas arising from an Island of langerhans. J Med Res. 1902;8(2):385–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberndorfer S Karzinoide Tumoren des Dünndarms. Frankfurter Zeitschrift Fur Pathologie. 1907;1:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams ED, Sandler M. The classification of carcinoid tumours. Lancet. 1963;1(7275):238–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris S. Hyperinsulinism and dysinsulinism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1924;83(10):729–733. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilder RM, Allan FN, Power MH, Robertson HE. Carcinoma of the islands of the pancreas: Hyperinsulinism and hypoglycemia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1927;89(5):348–355. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howland G, Campbell WR, Maltby EJ, Robinson WL. Dysinsulinism: Convulsions and coma due to islet cell tumor of the pancreas, with operation and cure. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1929;93(9):674–679. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett JH, Long CF. A case of congenital stenosis of the pulmonary valve, with late onset of cyanosis: death from carcinoma of the pancreas. Amer J MedSci. 1931;182:212. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peart WS, Porter KA, Robertson JI, Sandler M, Baldock E. Carcinoid syndrome due to pancreatic-duct neoplasm secreting 5-hydroxytryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptamine. Lancet. 1963;1(7275):239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker S, Kahn D, Rothman S. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignant tumors. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. 1942;45(6):1069–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Castillo EB, Trucco E, Manzuoli J. [Cushing’s disease and cancer of the pancreas]. La Presse Medicale. 1950;58(43):783–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balls KF, Nicholson JTL, Goodman HL, Touchstone JC. FUNCTIONING ISLET-CELL CARCINOMA OF THE PANCREAS WITH CUSHING’S SYNDROME. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1959;19(9):1134–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zollinger RM, Ellison EH. Primary Peptic Ulcerations of the Jejunum Associated with Islet Cell Tumors of the Pancreas. Annals of Surgery. 1955;142(4):709–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verner JV, Morrison AB. Islet cell tumor and a syndrome of refractory watery diarrhea and hypokalemia. Am J Med. 1958;25(3):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeWys WD, Stoll R, Au WY, Salisnjak MM. Effects of streptozotocin on an islet cell carcinoma with hypercalcemia. Am J Med. 1973;55(5):671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson LI, Hirsch MA, Holst JJ, et al. Pancreatic somatostatinoma. Clinical features and physiological implications. Lancet. 1977;1(8013):666–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplan RH, Koob L, Abellera RM, Pagliara AS, Kovacs K, Randall RV. Cure of acromegaly by operative removal of an islet cell tumor of the pancreas. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feurle GE, Helmstaedter V, Tischbirek K, et al. A multihormonal tumor of the pancreas producing neurotensin. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26(12):1125–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehfeld JF, Federspiel B, Bardram L. A neuroendocrine tumor syndrome from cholecystokinin secretion. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(12):1165–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):1–18, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121(4):589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(10):1727–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao JC, Eisner MP, Leary C, et al. Population-based study of islet cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3492–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fottner C, Ferrata M, Weber MM. Hormone secreting gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasias (GEP-NEN): When to consider, how to diagnose? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(4):393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo JH, Lee JA, Chabot JA. Nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94(3):689–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(2):409–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Wilde RF, Edil BH, Hruban RH, Maitra A. Well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: from genetics to therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(4):199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen RT, Berna MJ, Bingham DB, Norton JA. Inherited pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes: advances in molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and controversies. Cancer. 2008;113(7 Suppl):1807–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs. 4th Edition ed Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sipos B, Sperveslage J, Anlauf M, et al. Glucagon cell hyperplasia and neoplasia with and without glucagon receptor mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(5):E783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niina Y, Fujimori N, Nakamura T, et al. The current strategy for managing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Gut Liver. 2012;6(3):287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chi W, Warner RRP, Chan DL, et al. Long-term Outcomes of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2018;47(3):321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birnbaum DJ, Gaujoux S, Cherif R, et al. Sporadic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: prognostic significance of incidental diagnosis. Surgery. 2014;155(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagefi PA, Razo O, Deshpande V, et al. Evolving patterns in the detection and outcomes of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: the Massachusetts General Hospital experience from 1977 to 2005. Arch Surg. 2007;142(4):347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(5):753–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Luo G, Fu D, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Med Oncol. 2011;28(4):1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whipple AO, Frantz VK. Adenoma of Islet Cells with Hyperinsulinism: A Review. Ann Surg. 1935;101(6):1299–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(6):737–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):735–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):153–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2990–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maher ER, Neumann HP, Richard S. von Hippel-Lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(6):617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet. 2007;44(2):81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larson AM, Hedgire SS, Deshpande V, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Genet. 2012;82(6):558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staley BA, Vail EA, Thiele EA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: diagnostic challenges, presenting symptoms, and commonly missed signs. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erlic Z, Ploeckinger U, Cascon A, et al. Systematic comparison of sporadic and syndromic pancreatic islet cell tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013;42(4):557–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh S, Dey C, Kennecke H, et al. Consensus Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Guidelines from a Canadian National Expert Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(8):2685–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falconi M, Bartsch DK, Eriksson B, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system: well-differentiated pancreatic non-functioning tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vinik AI, Chaya C. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(1):21–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofland J, Zandee WT, de Herder WW. Role of biomarker tests for diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumours. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(11):656–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang X, Yang Y, Li Z, et al. Diagnostic value of circulating chromogranin a for neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marotta V, Zatelli MC, Sciammarella C, et al. Chromogranin A as circulating marker for diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine neoplasms: more flaws than fame. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(1):R11–R29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sherman SK, Maxwell JE, O’Dorisio MS, O’Dorisio TM, Howe JR. Pancreastatin predicts survival in neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):2971–2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Bodei L, Drozdov I, Aslanian H. The clinical utility of a novel blood-based multi-transcriptome assay for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(8):1223–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maxwell JE, Howe JR. Imaging in neuroendocrine tumors: an update for the clinician. Int J Endocr Oncol. 2015;2(2):159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sundin A, Arnold R, Baudin E, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Radiological, Nuclear Medicine & Hybrid Imaging. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):212–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dromain C, de Baere T, Lumbroso J, et al. Detection of liver metastases from endocrine tumors: a prospective comparison of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tirumani SH, Jagannathan JP, Braschi-Amirfarzan M, et al. Value of hepatocellular phase imaging after intravenous gadoxetate disodium for assessing hepatic metastases from gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: comparison with other MRI pulse sequences and with extracellular agent. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(9):2329–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reubi JC. Somatostatin and other Peptide receptors as tools for tumor diagnosis and treatment. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80 Suppl 1:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Treglia G, Castaldi P, Rindi G, Giordano A, Rufini V. Diagnostic performance of Gallium-68 somatostatin receptor PET and PET/CT in patients with thoracic and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2012;42(1):80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Squires MH 3rd, Volkan Adsay N, Schuster DM, et al. Octreoscan Versus FDG-PET for Neuroendocrine Tumor Staging: A Biological Approach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(7):2295–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puli SR, Kalva N, Bechtold ML, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(23):3678–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosch T, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF, et al. Localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(26):1721–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zilli A, Arcidiacono PG, Conte D, Massironi S. Clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasonography on the management of neuroendocrine tumors: lights and shadows. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bellizzi AM. Assigning site of origin in metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a clinically significant application of diagnostic immunohistochemistry. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(5):285–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Adsay NV, et al. Pathology reporting of neuroendocrine tumors: application of the Delphic consensus process to the development of a minimum pathology data set. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):300–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weynand B, Borbath I, Bernard V, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour grading on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: high reproducibility and inter-observer agreement of the Ki-67 labelling index. Cytopathology. 2014;25(6):389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al. , eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Edition ed. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellison TA, Wolfgang CL, Shi C, et al. A single institution’s 26-year experience with nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a validation of current staging systems and a new prognostic nomogram. Ann Surg. 2014;259(2):204–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morgan RE, Pommier SJ, Pommier RF. Expanded criteria for debulking of liver metastasis also apply to pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2018;163(1):218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scott AT, Breheny PJ, Keck KJ, et al. Effective cytoreduction can be achieved in patients with numerous neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases (NETLMs). Surgery. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finkelstein P, Sharma R, Picado O, et al. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (panNETs): Analysis of Overall Survival of Nonsurgical Management Versus Surgical Resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(5):855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bettini R, Partelli S, Boninsegna L, et al. Tumor size correlates with malignancy in nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumor. Surgery. 2011;150(1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee LC, Grant CS, Salomao DR, et al. Small, nonfunctioning, asymptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): role for nonoperative management. Surgery. 2012;152(6):965–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gaujoux S, Partelli S, Maire F, et al. Observational study of natural history of small sporadic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):4784–4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith JK, Ng SC, Hill JS, et al. Complications after pancreatectomy for neuroendocrine tumors: a national study. J Surg Res. 2010;163(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jutric Z, Grendar J, Hoen HM, et al. Regional Metastatic Behavior of Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Impact of Lymph Node Positivity on Survival. Pancreas. 2017;46(7):898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kuo EJ, Salem RR. Population-level analysis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors 2 cm or less in size. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2815–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jilesen AP, van Eijck CH, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, van Dijkum EJ. Postoperative Outcomes of Enucleation and Standard Resections in Patients with a Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. World J Surg. 2016;40(3):715–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hashim YM, Trinkaus KM, Linehan DC, et al. Regional lymphadenectomy is indicated in the surgical treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Ann Surg. 2014;259(2):197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamamoto Y, Okamura Y, Uemura S, et al. Vascularity and Tumor Size are Significant Predictors for Recurrence after Resection of a Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(8):2363–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Genc CG, Falconi M, Partelli S, et al. Recurrence of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Survival Predicted by Ki67. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(8):2467–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mayo SC, de Jong MC, Pulitano C, et al. Surgical management of hepatic neuroendocrine tumor metastasis: results from an international multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(12):3129–3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarmiento JM, Heywood G, Rubin J, Ilstrup DM, Nagorney DM, Que FG. Surgical treatment of neuroendocrine metastases to the liver: a plea for resection to increase survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maxwell JE, Sherman SK, O’Dorisio TM, Bellizzi AM, Howe JR. Liver-directed surgery of neuroendocrine metastases: What is the optimal strategy? Surgery. 2016;159(1):320–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(12):2679–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors: A systematic review. Surgery. 2017;162(3):525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mazzaferro V, Pulvirenti A, Coppa J. Neuroendocrine tumors metastatic to the liver: how to select patients for liver transplantation? J Hepatol. 2007;47(4):460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Almond LM, Hodson J, Ford SJ, et al. Role of palliative resection of the primary tumour in advanced pancreatic and small intestinal neuroendocrine tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(10):1808–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Trendle MC, Moertel CG, Kvols LK. Incidence and morbidity of cholelithiasis in patients receiving chronic octreotide for metastatic carcinoid and malignant islet cell tumors. Cancer. 1997;79(4):830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fernandez-Cruz L, Blanco L, Cosa R, Rendon H . Is laparoscopic resection adequate in patients with neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors? World J Surg. 2008;32(5):904–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mazzaglia PJ, Berber E, Milas M, Siperstein AE. Laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of neuroendocrine liver metastases: a 10-year experience evaluating predictors of survival. Surgery. 2007;142(1):10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Mestier L, Gaujoux S, Cros J, et al. Long-term Prognosis of Resected Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in von Hippel-Lindau Disease Is Favorable and Not Influenced by Small Tumors Left in Place. Ann Surg. 2015;262(2):384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blansfield JA, Choyke L, Morita SY, et al. Clinical, genetic and radiographic analysis of 108 patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) manifested by pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNETs). Surgery. 2007;142(6):814–818; discussion 818 e811–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lewis MA, Hobday TJ. Treatment of neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:973946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mohan H, Nicholson P, Winter DC, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for neuroendocrine liver metastases: a systematic review. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(7):935–942 e931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Muscatiello N. Microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32(3):339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mahnken AH, Konig AM, Figiel JH. Current Technique and Application of Percutaneous Cryotherapy. Rofo. 2018;190(9):836–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Groeschl RT, Pilgrim CH, Hanna EM, et al. Microwave ablation for hepatic malignancies: a multiinstitutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1195–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kennedy AS. Hepatic-directed Therapies in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(1):193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moertel CG, Hanley JA, Johnson LA. Streptozocin alone compared with streptozocin plus fluorouracil in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(21):1189–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Garcia-Carbonero R, Rinke A, Valle JW, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Systemic Therapy 2: Chemotherapy. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rinke A, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4656–4663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Cwikla JB, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):501–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ramirez RA, Beyer DT, Chauhan A, Boudreaux JP, Wang YZ, Woltering EA. The Role of Capecitabine/Temozolomide in Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kunz PL, Catalano PJ, Nimeiri H, et al. A randomized study of temozolomide or temozolomide and capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2211)[Abstract]. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(15_suppl):4004–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 Trial of (177)Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ilett EE, Langer SW, Olsen IH, Federspiel B, Kjaer A, Knigge U. Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Gastroenteropancreatic System: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2015;5(2):119–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Strosberg JR, Cheema A, Weber J, Han G, Coppola D, Kvols LK. Prognostic validity of a novel American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(22):3044–3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]