Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is an evolutionarily-conserved, structural and functional separation between circulating blood and the central nervous system. By controlling permeability into and out of the nervous system, the BBB plays a critical role in the precise regulation of neural processes. Here we review recent studies demonstrating that permeability at the BBB is dynamically controlled by circadian rhythms and sleep. An endogenous circadian rhythm in the BBB controls transporter function, regulating permeability across the BBB. In addition, sleep promotes the clearance of metabolites along the BBB, as well as endocytosis across the BBB. Finally, we highlight the implications of this regulation for diseases including epilepsy.

Keywords: pgp transporters, Drosophila, permeability, endocytosis, epilepsy, chronotherapy

The blood-brain barrier is a dynamic structure

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is not a static structure, but instead is a site of active regulation. As a cellular structure that separates circulatory fluids (e.g. blood, hemolymph) from the brain, the BBB imposes strict regulation on molecules moving into and out of the central nervous system. Here we focus on recent studies demonstrating that both circadian rhythms and sleep regulate the movement of molecules across and along the BBB.

Circadian rhythms are biological processes that endogenously oscillate with a period of approximately 24 hours. This rhythm is driven by a molecular clock and can be synchronized with, but is not reliant upon, external cues (e.g. light, temperature, and feeding patterns). While the central circadian pacemaker is in the brain (e.g. the suprachiasmatic nucleus in mammals), other cells, including the cells of the BBB [1, 2], have autonomous circadian rhythms driven by molecular clocks [3]. In addition the large arteries that perfuse the brain in mammals themselves contain endogenous circadian clocks [4, 5]. Critical studies originating in Drosophila melanogaster and then extended to mammals revealed that molecular clocks are comprised of transcriptional feedback loops. The core of this auto-regulatory loop in Drosophila involves the proteins Period (PER) and Timeless (TIM) inhibiting their own transcription at a specific time of day by acting on the transcriptional activators Clock (CLK) and Cycle (CYC) [6].

Sleep is an important behavior regulated by the circadian clock. While the timing of sleep is regulated by the circadian clock, the amount and quality of sleep depend largely on homeostatic mechanisms that ensure sufficient sleep in an organism. These two processes are separable, such that mutations in clock genes do not consistently lead to significant changes in total sleep [7], and mutations leading to decreased sleep do not disrupt the circadian clock [8, 9]. As for circadian rhythms, fly models provide a robust model system to study sleep. Fly sleep recapitulates several features of sleep found in mammals including circadian regulation, prolonged periods of quiescence with increased thresholds for arousal, electrophysiological correlates (although some of the electrophysiological signatures of sleep are specific to mammals), and changes with age [10–12]

In this review, we highlight recent evidence demonstrating that both circadian rhythms and sleep regulate functions of the blood-brain barrier across species. Entry of hormones, cytokines, and xenobiotics from blood to brain oscillates depending on the time of day. Additionally, both the movement of metabolic products along the BBB, and endocytosis across the BBB, typically occur more robustly during sleep. Finally, we comment on how this might affect human disease and future therapeutic interventions.

Drosophila melanogaster provides a robust model for studies of the blood-brain barrier

The mammalian BBB consists of vascular endothelial cells, connected to each other by tight junctions that form a lumen for blood flow. Endothelial cells express a set of transporters to move molecules both into and out of the brain [13], which include permeability-glycoprotein multidrug transporter (also known as pgp, multidrug resistance protein 1, or ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1 [ABCB1]), an ATP-dependent efflux pump that can pump both endogenous molecules and exogenous compounds back into the lumen of blood vessels [14, 15]. The surface of endothelial cells exposed to the brain is surrounded by specialized projections (endfeet) of astrocytic glial cells.

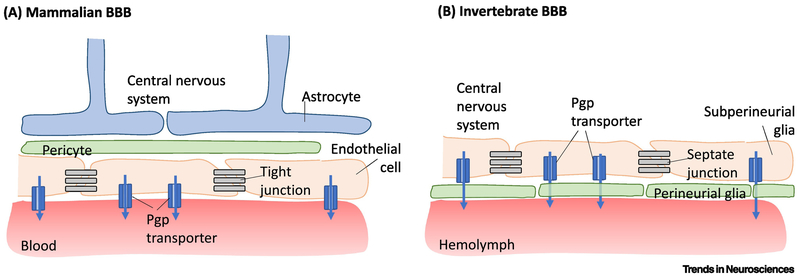

While there are differences at a gross anatomical level, the cellular structure and function of the Drosophila and mammalian BBB share many commonalities [16, 17] (Figure 1). Instead of a closed circulatory system found in mammals, flies have an open circulatory system containing hemolymph (analogous to blood) that is separated from the central nervous system by two layers of glial cells: perineurial glia (PG) and subperineurial glia (SPG). The SPG layer is proximal to the central nervous system and forms a continuous structure with tight junctions, whereas the PG layer is proximal to the hemolymph and coated in neural lamina [18]. The SPG express pgp-like transporters, allowing for the same active efflux that occurs in vertebrate systems [19]. We next discuss findings from fly and vertebrate models demonstrating how the BBB is regulated by time-of-day effects.

Figure 1. The mammalian and invertebrate BBB share structural and functional commonalities.

A) The mammalian BBB consists of vascular endothelial cells, connected to each other by tight junctions, lining blood vessels. Endothelial cells express permeability-glycoprotein multidrug transporter (pgp transporter) that pumps both endogenous and exogenous molecules out of the central nervous system and into the blood vessel lumen. Pericytes surround endothelial cells and help regulate endothelial cells’ barrier phenotype. Astrocytic endfeet ensheathe these blood vessels. B) The invertebrate BBB has several similar features. Hemolymph is separated from the central nervous system by two layers of glia: perineurial glia (PG) and subperineurial glia (SPG). The SPG are closer to the central nervous system and are connected by septate junctions. The SPG express pgp transporters, analogous to mammalian vascular endothelial cells.

Circadian regulation of permeability through the blood-brain barrier

Molecules can cross the BBB by 1) penetration through the plasma membrane through pores or endocytosis (e.g. albumin); 2) carrier-mediated transport systems (e.g. glucose, amino acids); 3) direct permeation through the plasma membrane (e.g. lipophilic molecules) [20], which is regulated by the activity of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters; or 4) paracellular aqueous diffusion, which under normal conditions is inhibited by tight junctions.

Rhythmic expression of several secreted molecules in the brain

The concentrations of several molecules in the central nervous system (CNS),undergo circadian oscillations, likely because of their rhythmic entry into the CNS (See Table 1). These include tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) [21], leptin [22], β-amyloid [23], delta-sleep inducing peptide (DSIP) [24], and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) [25]. When TNFα, an inflammatory cytokine, was intravenously injected into mice with an iodine label (125I- TNFα), uptake into the spinal cord demonstrated a circadian rhythm [21] such that greatest TNFα uptake occurred between Zeitgeber time (ZT) 20-23 (ZT0, lights on; ZT12, lights off); interestingly the same rhythmic uptake did not occur in the brain [21]. Knockdown of the TNFα receptors p55 and p75 in mice eliminated entry of 125I-labeled TNFα into the spinal cord and brain, implicating these receptors in the uptake [26]. Disease relevance is suggested for instance by the finding that TNFα uptake is upregulated after spinal cord injury, even in areas of the spinal cord not directly affected by the injury [27, 28].

Table 1.

Timing of Peak Concentrations in the CNS of Various Endogenous and Exogenous Molecules that Undergo Circadian Oscillations

| Class | Solute | Organism | Peak CNS accumulation | Animal behavior at peak | BBB mechanism | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | IL-6 | Human | 19:00 | Active | Carrier-mediated transport | [89,90] |

| TNFα | Mouse | ZT20–ZT23 | Active | Carrier-mediated transport | [21,26,28] | |

| Hormone | Leptin | Mouse | ZT14–ZT18 | Active | Carrier-mediated transport | [22] |

| Norepinephrine | Human | 09:00–15:00 h | Active | Unknown | [31] | |

| PDG2 | Rat | ZT8 | Rest | Unknown | [25,30] | |

| Peptide | β-amyloid | Mouse | ZT18–ZT24 | Active | Carrier-mediated transport | [23,70] |

| DSIP | Rat | ZT4–ZT8 | Rest | Unknown | [24] | |

| Xenobiotic | [18F]MC225 | Rat | ZT15 | Active | Direct permeation/efflux | [35] |

| Daunorubicin | Fly | ZT12 | Rest | Direct permeation/efflux | [36] | |

| Quinidine | Rat | ZT8 | Rest | Direct permeation/efflux | [34] | |

| Rhodamine B | Fly | ZT12–ZT16 | Rest | Direct permeation/efflux | [36] |

Similarly, entry of the hunger-suppressing hormone, leptin, into the brain and spinal cord undergoes daily oscillation. Labeling of leptin with 125I revealed greatest influx into the mouse brain and spinal cord between ZT14-ZT18 [22]. This also occurred through a saturable transport system, as addition of unlabeled leptin inhibited the uptake of labeled leptin into the CNS [22].

β-amyloid, involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease, also undergoes a daily oscillation in the interstitial fluid of mice, peaking between ZT18-24 [23]. Global loss of BMAL1, a component of the molecular clock, led to decreased daily oscillations of β-amyloid and increased amyloid plaque deposition [23]. This oscillation was dependent on function of the molecular clock in the SCN [23].

Other endogenous molecules also exhibit daily oscillations in the CSF, though the mechanisms of most of these cycles remain unclear. DSIP is a peptide that promotes slow-wave sleep. While the existence of DSIP as an endogenous peptide has been called into question [29], it does appear to cross the BBB though a non-saturable mechanism with circadian changes in brain concentration [24]. As another example, PGD2 exhibits daily oscillations in the rat CSF, peaking at 14:00 and increasing after sleep deprivation [25, 30]. Injection of PDG2 into the forebrain of rats resulted in increased sleep [30]. In addition, norepinephrine [31] and Interleukin 1a (IL-1a) [32] exhibit diurnal CNS oscillations through unknown mechanisms.

Rhythmic permeability of the BBB (discussed below) is one possible mechanism to explain rhythmic expression of secreted factors in the CNS. Another possibility is circadian regulation of the interstitial space of the brain, as movement of the interstitial fluid is thought to control or modulate the passage of molecules from the brain to the vasculature. It is known that sleep increases the volume of the interstitial space [33], which conceivably leads to changes in the concentration of various molecules, although the specifics of these changes remain debated.

Daily oscillations in permeability of exogenous molecules across the BBB

Pgp regulates the permeability of many endogenous and exogenous molecules across the BBB in a circadian manner. For instance, levels of quinidine, a substrate of pgp, were higher in the CSF and interstitial fluid of rats, as measured by microdialysis, when it was intravenously injected during their resting phase (ZT0, ZT4, and ZT8) than when they were active [34]. This suggests that pgp is more active during periods of wakefulness.

In contrast, when rats were injected with [18F]MC225, a radioactive substrate of pgp, increased accumulation in the brain occurred during the early active phase (ZT15) [35]. This suggests that the pgp transporter was less active when rats were behaviorally active at night, but these results are complicated by the fact that it is difficult to assess intravascular versus interstitial/CSF [18F]MC225 signal when using PET imaging. PET imaging does not allow for direct measurement of CNS concentrations, and thus may lead to the observed discrepancy with the previous study.

As in rodents, pgp activity is increased during times of wakefulness in flies. Injection of flies with rhodamine B, a xenobiotic, at various points throughout a day resulted in greater retention of the substrate in the brain at night (ZT12) during the rest phase [36]. This was due, in part, to active efflux through pgp-like transporter during the day, as genetic or pharmacological inhibition of this transporter increased accumulation of rhodamine B in the brain [36]. Loss of the circadian clock also inhibited the nighttime increase in permeability, suggesting that the clock normally inhibits pgp-like transporters at night to allow increased permeability [36]. Interestingly, genetic inhibition of pgp transporters in flies led to increased sleep, possibly by increasing CNS permeation of peripheral sleep-promoting molecules [37].

Mechanisms underlying circadian changes in BBB permeability

In unicellular organisms and human cells, intracellular Mg2+ regulates the period, amplitude, and phase of circadian oscillations and is itself controlled by the molecular clock [38]. As Mg2+ influences numerous cellular processes, including protein translation and function, changes in Mg over the course of the day can have profound effects on cell physiology.

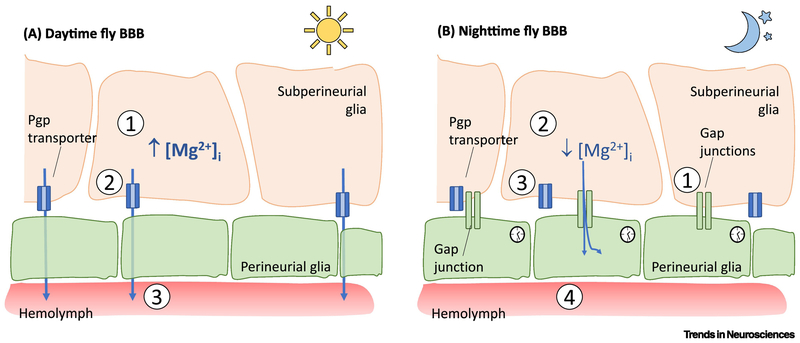

At the fly BBB, a molecular clock in the PG cells serves to maintain oscillations of Mg2+ [36]. High levels of Mg2+ in the subperineurial glia during daytime increases the activity of pgp transporters, thereby decreasing permeability of the BBB. Mg2+ increases the activity of pgp transporters by stabilizing their binding to ATP [39]. At night (ZT14), the circadian clock in the PG upregulates expression of gap junction proteins Inx1 and Inx2, leading to increased connectivity between subperineurial glia and perineurial glia and a decrease in Mg2+ in the SPG [36]. Thus, the perineurial glia function as a Mg2+ sink, driving intracellular Mg2+ down in subperineurial glia at night, which in turn decreases pgp activity and increases permeability at the BBB [36] (Figure 2). Interestingly, glial expression of the clock protein PERIOD decreases with age in fly models, although the relevance of this finding for BBB function is not known [40].

Figure 2. Circadian regulation of permeability-glycoprotein multidrug transporter-mediated permeability across the fly BBB.

A) During daytime, (1) the concentration of Mg2+ in subperineurial glia is higher, (2) leading to increased function of permeability-glycoprotein multidrug transporter (pgp transporters), thereby (3) increasing active efflux and decreasing permeability of the BBB. B) At nighttime, (1) expression of gap junction proteins Inx1 and Inx2 is upregulated by the molecular clock, leading to increased connectivity between subperineurial glia and perineurial glia. (2) The perineurial glia serve as a Mg2+ sink, driving intracellular Mg2+ down in subperineurial glia, which in turn (3) decreases pgp activity and (4) effectively increases permeability at the BBB.

Blood-brain barrier function is regulated by sleep

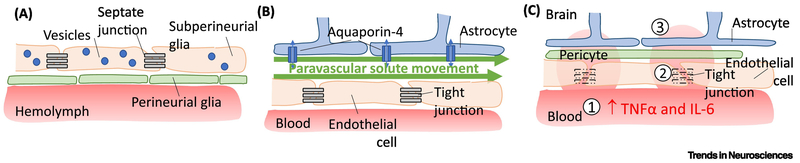

Recent evidence demonstrates that endocytosis occurs across the BBB during sleep, and inhibition of this process increases the need for sleep [41]. Sleep regulates movement of molecules not only across the BBB, but also along it, such that clearance of waste byproducts in the perivascular space is increased during sleep [42]. Sleep loss increases permeability of the BBB through a variety of mechanisms, including increased inflammatory signaling and down-regulation of tight-junction proteins [43, 44]. Disruption of sleep not only impairs these regulatory functions, but can also lead to breakdown of the BBB (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3. Endocytosis across and paravascular solute movement along the BBB is increased during sleep.

A) In fly models, endocytosis across subperineurial glia is increased in sleep. B) In mammals, interstitial fluid enters the brain parenchyma along paravascular spaces along arteries before entering the interstitial space in the brain parenchyma, allowing for solute movement. C) Sleep restriction leads to (1) increased activity of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-6, which can lead to (2) downregulation of tight junction proteins and (3) increased permeability of the BBB.

Endocytic trafficking across the BBB is enhanced during sleep

Endocytosis across the glia of the BBB is a newly appreciated function for sleep. Using a fly model, endocytosis was found to be highest early in the night (ZT14), when sleep need is thought to be the highest, and lowest early in the morning (ZT2), when sleep need is low [41]. Whereas sleep/wake state affects endocytosis, levels of endocytosis across subperineurial glia of the BBB (Figure 3A) also regulate sleep. Blocking endocytosis in the SPG through the use of Shibire, a dominant-negative allele of dynamin, which is a GTPase involved in endocytosis and vesicle formation, increased total sleep time [41]. These findings indicate a reciprocal relationship between sleep and endocytosis, although the specific molecules trafficked in a sleep-dependent fashion are not known yet. Importantly, inhibition of endocytic trafficking did not result in overt breakdown of the BBB, as 10 kD dextran was still restricted from the brains of these flies [41].

To identify critical components of endocytosis that drive sleep, a panel of Rab proteins was screened in flies [41]. Rab proteins are GTPases that regulate many aspects of vesicular formation, movement, and fusion. A constitutively-active form of Rab11 was found to promote sleep when expressed in either subperineurial glia or perineurial glia [41]. These data further indicate that endosomal formation and trafficking in the BBB is a critical role of sleep.

Mammalian models also demonstrate a correlation between sleep and vesicular trafficking across the BBB. Restriction of sleep in rats for 20 hours a day over 10 consecutive days revealed a 3-fold increase in the number of pinocytic vesicles in CA3 hippocampal endothelial cells, as revealed by transmission electron microscopy [45]. Taken together, invertebrate and vertebrate models suggest that endocytosis and vesicular trafficking across the BBB is modulated by sleep and could represent one of sleep’s functions. Induction of prolonged wakefulness leads to increased endocytosis across the BBB at the beginning of sleep, when sleep-need is the greatest. How this affects glial transcytosis, the movement of macromolecules from one side of the cell to the other, is unknown.

Sleep promotes perivascular clearance

As mentioned, in addition to regulation across the BBB, sleep/wake state also affects movement of molecules along the BBB. In rodent models, interstitial fluid is thought to enter the brain parenchyma along arterial perivascular spaces and exit along venous perivascular spaces [33, 42] through a ‘glymphatic system’ (Figure 3B), though other studies suggest drainage of interstitial fluid along arteries and capillaries [46, 47]. This system clears byproducts and waste products out of the brain and is facilitated by sleep [42]. Sleep is associated with an up to 60% increase in interstitial spaces (although controversy on the exact numbers remains), which may promote exchange between interstitial fluid and CSF due to decreased tissue resistance [42]. This CSF flux through the interstitium is facilitated by aquaporin-4 expression in astrocytes, as loss of aquaporin-4 in a mouse model decreased CSF influx and associated clearance of solutes [33]. Solute movement through perivascular and interstitial spaces is increased by the sleep state [42], but whether or not there is also circadian oscillation in the interstitial volume is unknown.

A well-studied toxic by-product regularly removed from the CNS is soluble β-amyloid. As demonstrated by murine models, in healthy physiology, most β-amyloid is cleared out of the brain, while the remainder is degraded [48]. β-amyloid is cleared through multiple overlapping routes (previously reviewed in detail [49]), which include substantial clearance through the BBB [50, 51], as well as elimination through the interstitital fluid-CSF exchange described above [33]. Consistent with the role of glial aquaporin-4 in solute movement, loss of aquaporin-4 in murine models leads to impaired β-amyloid clearance from the brain [33]. β-amyloid in the CSF likely exits through cervical lymphatic vessels into cervical lymph nodes [52].

These findings are important from a disease perspective, as perivascular clearance is reduced in the aging brain, leading to accumulation of β-amyloid associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Comparison of 2-3 month-old wild-type mice to 18-20 month-old mice showed a 40% decrease in β-amyloid clearance [53]. The age-related decline is attributed to decreased arterial pulsatility and decreased localization of aquaporin-4 to perivascular endfeet [53]. This effect may be further exacerbated by loss of sleep, given that older individuals sleep less and have decreased quality of sleep [54]. β-amyloid was found to accumulate in interstitial fluid during wakefulness and after sleep deprivation, in fact even after just one night of sleep deprivation [55, 56]. Similarly, tau, a cytoplasmic protein also associated with neurodegeneration, increases in interstitial fluid and CSF during wakefulness and after sleep deprivation in both mice and humans [57]. Thus, sleep may be restorative in neurodegenerative disease by allowing for perivascular clearance.

Sleep loss leads to increased BBB permeability

Many models demonstrate that sleep loss is associated with increased paracellular aqueous permeability, which is typically limited by tight junctions, at the BBB. When sleep was restricted in rats for 10 days, BBB permeability increased to allow influx of markers such as fluorescein-sodium and Evans blue [58, 59]. Even short periods of recovery sleep ranging from 40-120 minutes led to normalization of permeability, except in the hippocampus and cerebellum [45]. Similarly, sleep restriction for 6 days in mice led to increased permeability across the BBB to fluorescein and biotin, which normalized after 24 hours of recovery sleep [43].

The increased BBB permeability associated with sleep deprivation has been attributed to inflammatory signaling leading to downregulation of endothelial tight-junction proteins (Figure 3C). Sleep restriction leads to increased activity of several pro-inflammatory mediators, including C-reactive protein [60], interleukin-1β [61] (IL-1β), interleukin-6 [62] (IL-6), interleukin-17 [63] (IL-17), interferon-γ [64] (IFNγ), and TNFα [62, 64–67]. IL-1β suppresses astrocytic maintenance of the BBB, resulting in increased permeability [61]. TNFα and IL-6 lead to decreased expression and mislocalization of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a protein found in tight junctions, in human brain microvascular endothelial cells [44]. Sleep restriction in rats produced the formation of clefts between endothelial cells in the hippocampus, as well as decreased expression of tight junction components claudin-5 and occludin [58, 59]. Sleep restriction in mice also decreases expression of tight junction proteins including occludin, claudin-1, claudin-5, and zonula occludens-2 [43]. These effects of cytokine signaling on BBB permeability are not specific to sleep loss, as other models that enhance TNFα and IL-6 signaling can produce a similar breakdown [68, 69]. The effects of sleep loss on disruption of the BBB may be more apparent in aged mice as compared to young mice [65].

Possible roles for circadian- and sleep- mediated regulation of the blood-brain barrier

The recent studies discussed above suggest a model in which the energy-intensive process of moving molecules into and out of the brain is compartmentalized to certain times of the day. One could speculate that in part, the selectivity serves to distribute energy expenditure through the day. While we focused primarily on recent discoveries involving the pgp transporter and endocytosis across the blood-brain barrier, there are many other mechanisms of energy-dependent transport across the BBB, which involve other members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family of transporters as well the solute carrier (SLC) family of transporters. However, whether these larger superfamilies of transporters are regulated by circadian rhythms and sleep remains to be determined.

Possible compartmentalization of energy-intensive processes

Both fly and rodent models suggest that the ATP-dependent pgp transporter is more active during periods of activity [34, 36]. The transporter plays an important role in limiting exposure to exogenous molecules by actively pumping these molecules from the brain parenchyma into the lumen of blood vessels. This could be advantageous from an evolutionary perspective. As animals explore their environments, they encounter possibly neurotoxic molecules and rely on active transport of these toxins out of the brain. These types of exposures would presumably be fewer during periods of rest and inactivity, thereby decreasing the need for energy-intensive transport.

Conversely, during times of sleep, mechanisms that remove metabolic waste products are upregulated. Endocytosis across the fly BBB is upregulated during sleep, and when inhibited, increases the need for sleep [41]. Movement of solutes along perivascular spaces also plays an important role in clearing potentially toxic waste products out of the brain [42]. It seems plausible that at least some of these still-unidentified waste products may also be somnogenic (sleep-inducing) compounds, so that they would increase sleep in order to promote clearance.

This temporal compartmentalization of the activities of the BBB, with active efflux primarily occurring during the day and endocytosis with perivascular clearance occurring mostly during the night, may conserve energy over a day:night cycle. However, these processes are not mutually exclusive. For example, pgp transporters, which are under circadian control, also play a role in the clearance of β-amyloid from the brain [70]. Thus, while the absolute levels of pgp-related transport or endocytosis across the BBB change, these processes would not be expected to be turned completely ‘on’ or ‘off’ at any time of day. In addition, sleep deprivation has multiple effects that likely affect the balance of active efflux during wake and endocytosis during sleep. For example, while the concentration of cytokines in the CSF may be regulated by circadian changes in permeability across the BBB [21, 22], these same cytokines may accumulate during sleep deprivation to significantly increase BBB permeability.

The impact on disease: do changes in BBB permeability affect seizures?

Disruption of circadian- and sleep-mediated regulation of the BBB could contribute to disease. A comprehensive discussion of possible disease relevance is beyond the scope of the current article, and we will focus on epilepsy, where converging data seems to point at a prominent sleep/circadian disease component, possibly acting via regulation of the BBB. Postmortem hippocampi from people with epilepsy demonstrate breakdown of the BBB with increased extravasation of serum components into brain parenchyma [71, 72]. Preliminary data also indicate that acute breakdown of the BBB can cause seizures in a porcine model and in patients undergoing blood-brain barrier disruption for improved delivery of chemotherapy to the brain [73]. These studies indicate that loss of BBB integrity could worsen seizure burden.

Epilepsy is linked to circadian-dependent processes. For instance, seizure occurrence follows a cyclic pattern [74, 75]. A study of 131 adult patients with epilepsy using intracranial EEG recording demonstrated a peak in seizures between 16:00 and 19:00 for seizures originating from occipital or mesial temporal cortex, and between 04:00 and 07:00 for seizures from the frontal or parietal lobes [76]. Similarly a study of 225 children with epilepsy demonstrated a temporal distribution to seizures, with temporal lobe seizures occurring between 21:00 and 09:00, frontal lobe seizures between 00:00 and 06:00, parietal lobe seizures between 06:00 and 09:00, and occipital lobe seizures between 09:00 and 12:00 [77]. Why there are differences in the temporal distribution of seizures between adults and children is not known, but could reflect the diverse nature of epilepsy syndromes that occur at different ages, e.g. Panayiotopoulos Syndrome typically occurs in childhood and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy typically occurs in adolescence. Whether this periodicity in seizure frequency is related to BBB dysfunction is also not well understood. Nevertheless, circadian disruption of the BBB is likely not the only way circadian dysregulation increases susceptibility to seizures. For example, global disruption of BMAL1 or specific disruption of CLOCK, both components of the molecular clock, in neurons leads to a lower seizure threshold in mouse models [78, 79].

Additionally, sleep loss has been demonstrated to increase seizure frequency in both animal [80, 81] and human [82, 83] studies and increase the concentration of excitatory neurotransmitters [84]. As detailed above, sleep deprivation is associated with a breakdown of the BBB, possibly through an inflammatory mechanism. Whether sleep-dependent regulation at the BBB, including sleep-related perivascular solute clearance and endocytosis across the BBB, contributes to seizure burden is unknown.

A role for chronotherapy based on circadian changes in the BBB

Circadian changes in BBB permeability could be leveraged to improve disease therapy. In a fly model of epilepsy, administration of the anti-seizure medication phenytoin at night, when pgp-mediated efflux is low, was more effective in decreasing seizure burden than daytime administration [36]. This effect was dependent on the molecular clock, as inhibition of CYCLE, a per transcriptional activator, in the BBB blocked the circadian responsiveness to phenytoin [36]. These results likely extend to people with epilepsy as demonstrated in a cohort of 103 people who were being treated with phenytoin and carbamazepine [85]. When all or most of these medications were given at 20:00, as opposed to a more typical dosing schedule of equal doses twice daily, there was significant improvement in seizure control with decreased side effects and maintenance of appropriate drug levels in blood [85]. Thus a ‘chronotherapeutic’ dosing schedule could allow for improved efficacy at lower dosages, thereby decreasing the likelihood of toxic side-effects.

Other chronotherapeutic considerations may include giving a medication when it is optimally metabolized or when the symptoms are typically high. In a person with epilepsy, this would involve dosing a medication when seizure frequency is the greatest [86]. For example, in a study of 17 children with nocturnal and early morning seizures, 15 children had a greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency when their nighttime dose of anti-seizure medications was made proportionally larger [87].

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The BBB is dynamically regulated by both circadian rhythms and sleep. In the fly, circadian changes in pgp transporter activity controls permeability of serum components into the brain. Additionally, in mammals sleep is associated with increased perivascular clearance of waste metabolites out of the brain, and in flies with increased endocytosis across the BBB. Despite progress in understanding the regulation of the BBB, many questions remain (see Outstanding Questions). Identification of the critical molecules that traffic into and out of the brain continues to be very important. Identification of somnogenic molecules that arise in the periphery and cross the BBB to accumulate in the awake brain will further elucidate the physiological control of sleep. Understanding how sleep deprivation might affect circadian regulation will also likely yield important insights. Sleep restriction has wide-ranging effects, including fundamental changes such as decreased glucose uptake into the brain [43].

Outstanding Questions.

Does sleep deprivation affect the circadian rhythm of BBB permeability? As recently demonstrated in the fly BBB, permeability at the BBB increases because of decreased Pgp activity at night. Understanding how sleep loss, common inmodern society, mightmodulate Pgp transporter activity may shed light on essential functions of sleep.

What are the molecules that accumulate in the awake brain to promote sleep?

What molecules are trafficked across the BBB by endocytosis during sleep?While recent data fromthe fly BBB highlight the importance of endocytosis during sleep, further studies are necessary to identify the critical molecules being trafficked.

What is the physiological relevance of changing molecular transport across the BBB depending on the time of day or state of an animal? In this article, we hypothesize that time of day or behavioral state temporally compartmentalizes different types of energy-intensive molecular trafficking.

Is sleep- and circadian-regulated permeability of the BBB relevant for human disease? Disrupted sleep and circadian rhythms may contribute to a variety of neurological diseases, including epilepsy. Further studies investigating whether sleep- and circadian-regulated permeability of the BBB is disrupted in disease states could open new avenues of treatment.

How can medication dosing schedules be optimized to account for circadian changes in BBB permeability, for instance in epilepsy? Given that numerous clinical studies demonstrate a clear circadian rhythm in seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy, it is possible that leveraging time-related changes in BBB permeability could allow for more effective seizure treatment with fewer offtarget adverse effects.

Sleep and circadian clocks are closely linked to human neurological disease. Among the clearest examples is epilepsy, which demonstrates a circadian rhythm of seizure occurrence. Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease, have also been associated with sleep and circadian disturbances, as reviewed elsewhere [88]. In addition to understanding disease pathology, circadian regulation is relevant for the treatment of disease. Chronotherapeutic approaches that capitalize on times and states of increased BBB permeability have the potential to improve patient outcomes while minimizing undesirable side-effects. Thus, understanding the role of sleep- and circadian-related changes in BBB has the potential to improve management of human disease.

Highlights.

Recent evidence from fly models reveals an endogenous circadian rhythm at the blood-brain barrier. This rhythm controls function of the permeability-glycoprotein multidrug transporter, which actively pumps both endogenous and exogenous molecules out of the central nervous system. Function of this transporter is decreased at night, increasing permeability to multiple substrates into the brain overnight.

Endocytosis is a newly-appreciated important function for sleep. Endocytosis across the BBB is increased during sleep, and when inhibited, increases the need for sleep.

Sleep also promotes the clearance of metabolites out of the brain along paravascular spaces. During sleep, the interstitial spaces of the brain are larger, allowing for more robust movement of metabolites from interstitial spaces into CSF. These solutes can then travel along vessels and out of the brain.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R37NS048471 to A.S. and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (A.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carver KA et al. (2014) Rhythmic expression of cytochrome P450 epoxygenases CYP4×1 and CYP2c11 in the rat brain and vasculature. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307, 989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Y et al. (2014) Clock upregulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and promotes mononuclear cells adhesion to endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443, 586–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohawk JA et al. (2012) Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci 35, 445–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson AJ et al. (2005) Cardiovascular tissues contain independent circadian clocks. Clin Exp Hypertens 27, 307–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durgan DJ et al. (2017) The rat cerebral vasculature exhibits time-of-day-dependent oscillations in circadian clock genes and vascular function that are attenuated following obstructive sleep apnea. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37, 2806–2819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubowy C and Sehgal A (2017) Circadian Rhythms and Sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 205, 1373–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendricks JC et al. (2003) Gender dimorphism in the role of cycle (BMAL1) in rest, rest regulation, and longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Rhythms 18, 12–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh K et al. (2008) Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science 321, 372–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi M et al. (2014) Identification of Redeye, a new sleep-regulating protein whose expression is modulated by sleep amount. Elife 3, e01473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw PJ et al. (2000) Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287, 1834–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitz DA et al. (2002) Electrophysiological correlates of rest and activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol 12, 1934–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirelli C and Bushey D (2008) Sleep and wakefulness in Drosophila melanogaster. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1129, 323–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daneman R and Prat A (2015) The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King M et al. (2001) Transport of opioids from the brain to the periphery by P-glycoprotein: peripheral actions of central drugs. Nat Neurosci 4, 268–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loscher W and Potschka H (2005) Blood-brain barrier active efflux transporters: ATP-binding cassette gene family. NeuroRx 2, 86–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hindle SJ and Bainton RJ (2014) Barrier mechanisms in the Drosophila blood-brain barrier. Front Neurosci 8, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeSalvo MK et al. (2011) Physiologic and anatomic characterization of the brain surface glia barrier of Drosophila. Glia 59, 1322–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stork T et al. (2008) Organization and function of the blood-brain barrier in Drosophila. J Neurosci 28, 587–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer F et al. (2009) Evolutionary conservation of vertebrate blood-brain barrier chemoprotective mechanisms in Drosophila. J Neurosci 29, 3538–3550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banks WA and Kastin AJ (1985) Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to neuropeptides: the case for penetration. Psychoneuroendocrinology 10, 385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan W et al. (2002) Selected contribution: circadian rhythm of tumor necrosis factor-alpha uptake into mouse spinal cord. J Appl Physiol (1985) 92, 62; discussion 1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan W and Kastin AJ (2001) Diurnal variation of leptin entry from blood to brain involving partial saturation of the transport system. Life Sci 68, 2705–2714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kress GJ et al. (2018) Regulation of amyloid-beta dynamics and pathology by the circadian clock. J Exp Med 215, 1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks WA et al. (1985) Modulation of immunoactive levels of DSIP and blood-brain permeability by lighting and diurnal rhythm. J Neurosci Res 14, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandey HP et al. (1995) Concentration of prostaglandin D2 in cerebrospinal fluid exhibits a circadian alteration in conscious rats. Biochem Mol Biol Int 37, 431–437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan W and Kastin AJ (2002) TNFalpha transport across the blood-brain barrier is abolished in receptor knockout mice. Exp Neurol 174, 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan W et al. (1997) Blood-brain barrier permeability to ebiratide and TNF in acute spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 146, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan W et al. (1999) Upregulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha transport across the blood-brain barrier after acute compressive spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 19, 3649–3655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovalzon VM and Strekalova TV (2006) Delta sleep-inducing peptide (DSIP): a still unresolved riddle. J Neurochem 97, 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ram A et al. (1997) CSF levels of prostaglandins, especially the level of prostaglandin D2, are correlated with increasing propensity towards sleep in rats. Brain Res 751, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziegler MC et al. (1976) Circadian rhythm in cerebrospinal fluid noradrenaline of man and monkey. Nature 264, 656–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banks WA et al. (1998) Diurnal uptake of circulating interleukin-1alpha by brain, spinal cord, testis and muscle. Neuroimmunomodulation 5, 36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iliff JJ et al. (2012) A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 4, 147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kervezee L et al. (2014) Diurnal variation in P-glycoprotein-mediated transport and cerebrospinal fluid turnover in the brain. Aaps J 16, 1029–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savolainen H et al. (2016) P-glycoprotein Function in the Rodent Brain Displays a Daily Rhythm, a Quantitative In Vivo PET Study. Aaps J 18, 1524–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang SL et al. (2018) A Circadian Clock in the Blood-Brain Barrier Regulates Xenobiotic Efflux. Cell 173, 139.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hindle SJ et al. (2017) Evolutionarily Conserved Roles for Blood-Brain Barrier Xenobiotic Transporters in Endogenous Steroid Partitioning and Behavior. Cell Rep 21, 1304–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feeney KA et al. (2016) Daily magnesium fluxes regulate cellular timekeeping and energy balance. Nature 532, 375–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth CL et al. (2000) Analysis of the properties of the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain of human P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry 39, 5518–5526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long DM and Giebultowicz JM (2018) Age-Related Changes in the Expression of the Circadian Clock Protein PERIOD in Drosophila Glial Cells. Front Physiol 8, 1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Artiushin G et al. (2018) Endocytosis at the Drosophila blood-brain barrier as a function for sleep. Elife 7, 10.7554/eLife.43326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie L et al. (2013) Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342, 373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He J et al. (2014) Sleep restriction impairs blood-brain barrier function. J Neurosci 34, 14697–14706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rochfort KD and Cummins PM (2015) Cytokine-mediated dysregulation of zonula occludens-1 properties in human brain microvascular endothelium. Microvasc Res 100, 48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez-Gonzalez B et al. (2013) REM sleep loss and recovery regulates blood-brain barrier function. Curr Neurovasc Res 10, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arbel-Ornath M et al. (2013) Interstitial fluid drainage is impaired in ischemic stroke and Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Acta Neuropathol 126, 353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szentistvanyi I et al. (1984) Drainage of interstitial fluid from different regions of rat brain. Am J Physiol 246, 835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qosa H et al. (2014) Differences in amyloid-beta clearance across mouse and human blood-brain barrier models: kinetic analysis and mechanistic modeling. Neuropharmacology 79, 668–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarasoff-Conway JM et al. (2015) Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 457–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shibata M et al. (2000) Clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-ss(1-40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest 106, 1489–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storck SE et al. (2016) Endothelial LRP1 transports amyloid-beta(1-42) across the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest 126, 123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pappolla M et al. (2014) Evidence for lymphatic Abeta clearance in Alzheimer’s transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis 71, 215–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kress BT et al. (2014) Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol 76, 845–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohayon MM et al. (2004) Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep 27, 1255–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shokri-Kojori E et al. (2018) beta-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 4483–4488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang JE et al. (2009) Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 326, 1005–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holth JK et al. (2019) The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science 363, 880–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hurtado-Alvarado G et al. (2017) Chronic sleep restriction disrupts interendothelial junctions in the hippocampus and increases blood-brain barrier permeability. J Microsc 268, 28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hurtado-Alvarado G et al. (2016) A2A Adenosine Receptor Antagonism Reverts the Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Induced by Sleep Restriction. PLoS One 11, e0167236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meier-Ewert HK et al. (2004) Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 43, 678–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y et al. (2014) Interleukin-1beta induces blood-brain barrier disruption by downregulating Sonic hedgehog in astrocytes. PLoS One 9, e110024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Venancio DP and Suchecki D (2015) Prolonged REM sleep restriction induces metabolic syndrome-related changes: Mediation by pro-inflammatory cytokines. Brain Behav Immun 47, 109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yehuda S et al. (2009) REM sleep deprivation in rats results in inflammation and interleukin-17 elevation. J Interferon Cytokine Res 29, 393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hurtado-Alvarado G et al. (2018) The yin/yang of inflammatory status: Blood-brain barrier regulation during sleep. Brain Behav Immun 69, 154–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Opp MR et al. (2015) Sleep fragmentation and sepsis differentially impact blood-brain barrier integrity and transport of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in aging. Brain Behav Immun 50, 259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramesh V et al. (2012) Disrupted sleep without sleep curtailment induces sleepiness and cognitive dysfunction via the tumor necrosis factor-alpha pathway. J Neuroinflammation 9, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chennaoui M et al. (2011) Effect of one night of sleep loss on changes in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) levels in healthy men. Cytokine 56, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silwedel C and Forster C (2006) Differential susceptibility of cerebral and cerebellar murine brain microvascular endothelial cells to loss of barrier properties in response to inflammatory stimuli. J Neuroimmunol 179, 37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farkas G et al. (1998) Experimental acute pancreatitis results in increased blood-brain barrier permeability in the rat: a potential role for tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 6. Neurosci Lett 242, 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cirrito JR et al. (2005) P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest 115, 3285–3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rigau V et al. (2007) Angiogenesis is associated with blood-brain barrier permeability in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 130, 1942–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Vliet EA et al. (2007) Blood-brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 130, 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marchi N et al. (2007) Seizure-promoting effect of blood-brain barrier disruption. Epilepsia 48, 732–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanchez Fernandez I and Loddenkemper T (2018) Chronotherapeutic implications of cyclic seizure patterns. Nat Rev Neurol 14, 696–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karoly PJ et al. (2018) Circadian and circaseptan rhythms in human epilepsy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 17, 977–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Durazzo TS et al. (2008) Temporal distributions of seizure occurrence from various epileptogenic regions. Neurology 70, 1265–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Loddenkemper T et al. (2011) Circadian patterns of pediatric seizures. Neurology 76, 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li P et al. (2017) Loss of CLOCK Results in Dysfunction of Brain Circuits Underlying Focal Epilepsy. Neuron 96, 401.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gerstner JR et al. (2014) BMAL1 controls the diurnal rhythm and set point for electrical seizure threshold in mice. Front Syst Neurosci 8, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lucey BP et al. (2015) A new model to study sleep deprivation-induced seizure. Sleep 38, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohen HB and Dement WC (1970) Prolonged tonic convulsions in REM deprived mice. Brain Res 22, 421–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fang PC et al. (2008) Seizure precipitants in children with intractable epilepsy. Brain Dev 30, 527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rajna P and Veres J (1993) Correlations between night sleep duration and seizure frequency in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 34, 574–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mohammed HS et al. (2011) Neurochemical and electrophysiological changes induced by paradoxical sleep deprivation in rats. Behav Brain Res 225, 39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yegnanarayan R et al. (2006) Chronotherapeutic dose schedule of phenytoin and carbamazepine in epileptic patients. Chronobiol Int 23, 1035–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ramgopal S et al. (2013) Chronopharmacology of anti-convulsive therapy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guilhoto LM et al. (2011) Higher evening antiepileptic drug dose for nocturnal and early-morning seizures. Epilepsy Behav 20, 334–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mattis J and Sehgal A (2016) Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and Disorders of Aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27, 192–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agorastos A et al. (2014) Circadian rhythmicity, variability and correlation of interleukin-6 levels in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of healthy men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 44, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Banks WA et al. (1994) Penetration of interleukin-6 across the murine blood-brain barrier. Neurosci Lett 179, 53–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]