Abstract

Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa are at disproportionately high risk for intimate partner violence (IPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The interconnected risks for IPV and HIV present the opportunity for interventions to concurrently seek to reduce violence and sexual risk behaviors among young people. Accordingly, the present systematic review evaluates interventions that concomitantly address IPV and HIV risk among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. The authors systematically reviewed electronic databases for studies meeting the following criteria: use of randomized control trials (RCT) or quasi-RCT in Sub-Saharan African countries; inclusion of adolescents aged 13–18 years; use of a comparison group (wait listed, designated to a comparative treatment, or treatment as usual); and incorporation of IPV and HIV outcome assessments. Results suggested that six studies have utilized rigorous research methodologies to evaluate integrated IPV/HIV interventions; however, few have targeted adolescents. The six studies meeting inclusion criteria indicate that current research on IPV/HIV is conducted with rigorous study designs among target populations with high IPV/HIV risk, using gender-specific risk reduction activities. The authors' findings indicate there is also the need for consistent application of valid and reliable outcome measurements of IPV and HIV risk. Additional research is needed to identify best practices for reducing IPV and HIV incidence among vulnerable adolescent populations in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: domestic violence, intervention/treatment, youth violence, adolescent victims

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa is disproportionately affected by the global burdens of intimate partner violence (IPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). According to the World Health Organization, IPV is defined as a subset of gender-based violence (GBV), in which acts or threats of physical, sexual, and emotional violence are perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner (World Health Organization 2013). Although men and boys experience sexual violence, women and girls are at disproportionately higher risk for violence (World Health Organization 2014). In the African region, 36.6% of women reported lifetime experience of physical or sexual IPV, compared with 23.2% in high-income regions (World Health Organization 2013). Sub-Saharan African countries also account for 64% of all new HIV acquisition (Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], 2017). Furthermore, an estimated 25.5 million adults and children are living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa and 10 countries alone are home to 80% of the global population of individuals living HIV (UNAIDS 2014, 2017). The high prevalence rates of IPV and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa underscore the importance of intervening to address these dual public health concerns.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, adolescence marks a period of increased risk for both IPV and HIV (Flisher et al. 2007; UNAIDS 2017). One study among South African adolescents reported that 49.8% of the boys and 52.4% of the girls in Grades 9–12 had experienced or perpetrated physical violence in a dating relationship (Swart et al. 2002). Among the global population of adolescents living with HIV, nearly 85% live in Sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations Children's Fund 2017). There are several potential reasons why adolescents show elevated risk for both IPV and HIV. Sexual debut is common in adolescence and can be associated with increased risk for negative health outcomes such as acquisition of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended pregnancies, and sexual violence (Kotchick et al. 2001). In fact, by the age of 16, 50% or more of South African and Tanzanian youths have become sexually active (Eaton et al. 2003; Munguti et al. 1997). High rates of transactional sex among young women Sub-Saharan Africa (Luke 2003) may increase risk for both IPV and HIV due to power dynamics and condom negotiation within relationships (Dunkle et al. 2004a; Kaufman and Stavrou 2002). In addition, high rates of engagement in age-disparate sexual relationships may also increase risk for both IPV and HIV (Evan et al. 2016). A systematic review by Eaton et al. (2003) found that high rates of force, coercion, and male-dominated sexual relationships may also exacerbate HIV risk among South African adolescents (Eaton et al. 2003).

Research emerging from Sub-Saharan Africa suggests that adolescents and particularly young women who experience IPV are at higher risk for HIV and other STIs (Jewkes et al. 2010; Teitelman et al. 2016). Experiences of IPV can increase risk for HIV through several pathways (Dunkle and Decker 2013; Dunkle et al. 2004b; García-Moreno and Watts 2000; Jewkes et al. 2010; Li et al. 2014; Maman et al. 2002; van der Straten et al. 1998). First, experiences of sexual victimization among women often result in tearing of sexual tissue, which can increase susceptibility to HIV acquisition (Kim et al. 2003). Other studies suggest that power inequality in violent dating relationships is negatively associated with women's ability to negotiate condom use and refuse unwanted sexual activity (García-Moreno and Watts 2000; Pettifor et al. 2004). Research also demonstrates an association between IPV and increased engagement in sexual risk behavior among adolescents, including engaging in sexual activity with multiple sexual partners, substance use, and transactional sex (Dunkle and Decker 2013; Dunkle et al. 2007). HIV-positive women may also face increased risk of IPV as a result of HIV status disclosure, and some women may choose not to disclose their status to sexual partners due to fear of violence (Maman et al. 2001).

Currently, several reviews document the efficacy of IPV and HIV interventions for adults in Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, an evaluation of IPV prevention strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa and other low- and middle-income countries found that structural interventions are potentially effective in reducing male perpetration of IPV (Bourey et al. 2015). Another review of IPV interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa reported promising results from community-based interventions that aim to change gender attitudes and the community's tolerance of IPV (McCloskey et al. 2016). Problematically, both these recent reviews lacked attention to the specific inclusion of adolescents in these interventions; a particularly high-risk group. One systemic review assessed IPV interventions targeting adolescents, but did not focus specifically on Sub-Saharan Africa (De Koker et al. 2014).

Understanding what interventions have included or targeted adolescents can help inform the development of interventions focused on preventive strategies in this younger age group. Because patterns on the prevalence of violence show that violence rises steadily from early adolescence onward (World Health Organization 2013), effective intervention for violence early in the life course can prevent the development of numerous poor health outcomes associated with IPV.

Reviews of HIV preventive interventions specifically targeting adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa suggest various intervention strategies and designs that currently demonstrate mixed results (Harrison et al. 2010; Michielsen et al. 2013; Paul-Ebhohimhen et al. 2008). For example, Harrison et al. (2010) reviewed eight HIV interventions for South African adolescents and found that prevention strategies which targeted social and structural factors for HIV risk, as well as causal HIV risk pathways specific to the region, had the biggest impact of sexual risk behavior reduction. Michielsen et al. (2013) reviewed HIV prevention among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa and attributed the limited effectiveness of current strategies to factors related to the intervention design, implementation, and evaluation. Paul-Ebhohimhen's et al. (2008) review suggests that school-based HIV prevention have a greater statistically significant impact on outcomes related to HIV knowledge and attitudes than outcomes related to behavior change.

Taken together, while previous reviews of the literature document the efficacy of interventions targeting adults at risk for either IPV or HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa, research to date is lacking on the efficacy of interventions that concurrently address IPV and HIV. In fact, to their knowledge, the only review evaluating interventions addressing both HIV and IPV risks in Sub-Saharan Africa is specific to identifying interventions that could be led by nurses in health care settings (Anderson et al. 2013). No studies to date have reviewed the efficacy of interventions that concurrently target IPV and HIV risks among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Adolescence offers a crucial window of opportunity for reducing IPV and HIV incidence by preventing or curtailing problematic relationship (De Koker et al. 2014) and sexual behaviors (Pedlow and Carey 2004) to preclude continuing patterns of violence and sexual risk into adulthood. Given the prevalence of IPV and HIV among adolescents, and the potential for interventions to address these intersecting public health concerns concurrently, the present systematic review sought to evaluate the current evidence base on interventions that concurrently target the prevention of HIV and IPV for adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The authors used a Boolean search strategy to find peer-reviewed studies in four electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL). The following search terms were expanded and modified, if necessary, for each electronic database: HIV, IPV, adolescent, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The search terms for each database can be found in the appended search protocol (Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed studies were included in the systematic review if they (a) sampled people living in Sub-Saharan African countries, (b) utilized a randomized control trial (RCT) or quasi-RCT design and presented results of the intervention, (c) targeted both IPV and HIV risk behavior, including but not limited to HIV acquisition, as primary outcomes for either prevention or risk reduction, (d) included a control or comparison group that received standard care (including treatment as usual/no intervention), a wait-list control group, or comparative treatment intervention, and (e) targeted, or included, adolescent participants 13–18 years of age (inclusive). Studies were excluded from the systematic review if the intervention (a) did not measure both IPV and HIV as outcomes, (b) lacked a comparison group, or (c) described the intervention in a study protocol without available results. Because they were interested in reviewing all past and currently existing IPV/HIV interventions, they did not confine their search to a predefined publication period.

While there is variation in what is culturally and socially recognized as the stage of adolescence (American Psychological Association 2002), the systematic review defined adolescence as 13–18 years of age to align with the scope of the medical subject heading term used for the electronic database search. However, because they wanted to ensure that the search string did not exclude studies that included adolescents combined with other groups, the authors did not use age criteria in the search string, but rather chose to capture these articles in an initial electronic search for further title and abstract, then full-text review. The electronic databases were searched during October 2017 and yielded 727 unique reports. A preliminary review resulted in the exclusion of 702 articles as their titles or abstracts did not fulfill the inclusion criteria.

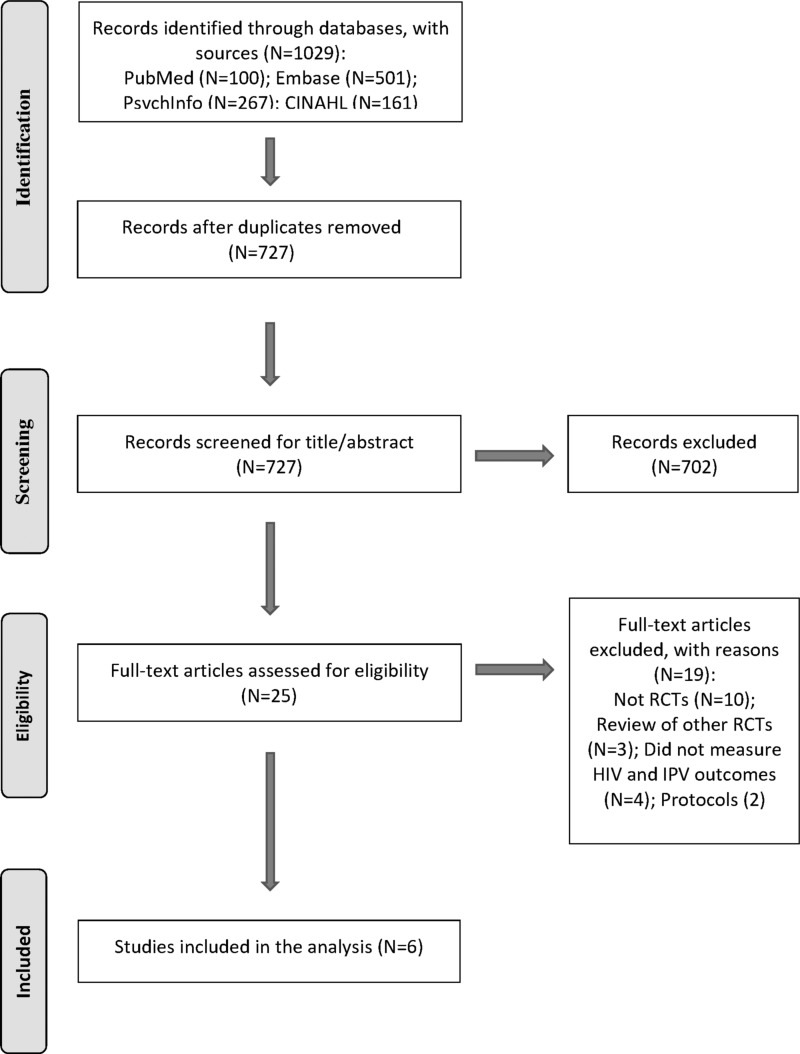

After full-text review of the remaining 25 articles, 19 were excluded from analysis because they did not (a) provide an integrated IPV/HIV prevention or risk reduction intervention, (b) measure both IPV and HIV, (c) include a control or comparison group, or (d) include peer-reviewed results. Figure 1 presents a PRISMA diagram depicting a graphical representation of the study selection process. Specific details were extracted from the included studies: study design, sample characteristics, format and dosage of activities, assessments, results, and follow-up times. Data extraction included coding for details related to both intervention delivery and study methodology.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart for study selection.

Multiple authors reviewed each stage of data extraction and resolved any point of disagreement through discussion and revisiting the inclusion criteria and data abstraction table. When key study information was not provided, they contacted the authors directly for clarification. The list of included studies was sent to two experts in the field to confirm that no studies were missing from the list. Study information was then assessed using thematic analysis with the findings presented below.

Results

Overview

Six studies that met inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review. These studies describe interventions targeting prevention or risk reduction for both IPV and HIV among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. Table 1 provides details for these six studies, including a description of study samples and intervention elements. The six studies were all published in the past 12 years, including the IMAGE study (Pronyk et al. 2006), Stepping Stones (Jewkes et al. 2008), Kalichman et al.'s GBV/HIV prevention intervention (2009), SASA! (Abramsky et al. 2014), Safe Homes and Respect for Everyone (SHARE) (Wagman et al. 2015), and PREPARE (Mathews et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Integrated Intimate Partner Violence/Human Immune Deficiency Virus Interventions Targeting or Including Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa

| Study | Location | Participant characteristics | Intervention description | Study characteristics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramsky et al. (2014) | Rubaga and Makindye Divisons, Kampala, Uganda. | 2532 men and women at F/U Avg age men: 27 years; avg age women:28 years | 4 years, 5 month 1. No specific dosage of community mobilization activities: advocacy and media on local media channels, communication materials, training. 2. CG wait-listed |

Pair-matched CRCT; 4-year F/U survey. IPV outcomes: a priori; social acceptability IPV; women's PYr exp. IPV. HIV outcome: SRBs | At 4 years F/U, lower acceptance of IPV among women; higher acceptance of a woman refusing sex among women. Decreased past year sexual concurrency among men. |

| Jewkes et al. (2008) | Eastern Cape province of South Africa | 2776 men and women 16–23 years old. | 6–8 weeks, 1. Thirteen 1 h sessions in single-sex groups (role play, drama, critical reflection); three meetings; one community meeting; 2. CG 3 h session on HIV risk. |

CRCT; F/U at 12 and 24 months F/U rate 75% for men and women at 12 months, 73% of women and 69% of men at 24 months IPV outcome: IPV incidence questionnaire. HIV: biological outcomes; SRBs. | Intervention was not associated with lower HIV acquisition; associated with lower HISV-2. No significant effect on reported IPV perp among men. |

| Kalichman et al. (2009) | Cape Town, South Africa | 475 men. Avg age 30.2 years (standard deviation 9.5). | 1 week 1. 5 small group sessions (skill building, goal setting, risk identification, condom use skill building, sexual communication training) 2. CG: 3-h HIV/alcohol risk session; no IPV component. |

Quasi-experimental intervention trial; F/U at 1 mo, 3 and 6 months. Participant retention greater than 90%. IPV outcome: seven-item domestic violence scale; past month IPV perp. HIV: 11 item HIV knowledge test; four item stigma scale; SRB intent. | Increased discussion of condoms with partner at 1 month F/U; increased reporting of HIV testing at 3 months F/U; increased intention to reduce SRBs, decreased reporting of past-month physical IPV perp at 6-months F/U. |

| Mathews et al. (2016) | Western Cape, South Africa | 3451 Grade 8 participants. Avg age 13 years. | 21 weeks 1. Weekly 1–1.5 h after-school sessions (interactive and skill based group sessions); weekly access to PREPARE school nurse; 2-day training for school safety teams. 2. CG: attended school as usual |

CRCT; F/U at 6 and 12 months. 94% retention at 6 months and 88% retention at 12 months IPV outcome: IPV exp and perp past 6 months. HIV: SRBs | No significant association between intervention and SRBs at 6 or 12 months F/U. At 12 months. F/U, participants less likely to report IPV exp. |

| Pronyk et al. (2006) | Rural Limpopo province of South Africa | 6576 men and women. Eight hundred sixty women in Cohort 1 exposed to intervention. Avg age Cohort 1: 41 years. Cohort 2: persons 14–35 years old sleeping in Cohort 1 household; Cohort 3: 14–35 de jure residents of Cohort 1 households. | 12–15 months 1. Cohort 1: Microfinance group meetings every 2 weeks over 10 or 20 weeks cycles; 1 h gender and HIV training session every 2 weeks; Community mobilization for 6–9 months following training. 2. CG wait-listed |

CRCT; F/U at 2 years (Cohort 1 and Cohort 2) and 3 years (Cohort 3). At 2 years F/U, study retained 90% of intervention cohort 1 and 84% of CG cohort 1. IPV outcome: PYr IPV exp. HIV: biological outcome; SRBs | 2 years F/U Cohort 1 less likely to report PYr IPV exp. Intervention not associated with decreased SRBs or decreased HIV acquisition in Cohorts 2 and 3. |

| Wagman et al. (2015) | Rakai, Uganda | 11,448 individuals 15–49 years (no avg age provided) | 4 years No specific dosage 1. Community mobilization activities (activism, campaigns, newsletters, peer groups, support counseling). 2. CG: routine HIV prevention and treatment services. |

CRCT; F/U at 16 and 35 months after baseline. Retention 57% at 35 month F/U. IPV outcome: conflict tactic scales PYr exp and perp. HIV: biological outcome; SRBs | Intervention associated with decreased exp of physical and sexual IPV at 35 months. follow up. SHARE associated with decreased HIV acquisition. |

avg, average; CRCT, cluster randomized control trial; CG, comparison group; exp, experience; F/U, follow-up; PYr, past year; perp, perpetration; SRBs, sexual risk behaviors; IPV, intimate partner violence; HIV, human immune deficiency virus; SHARE, Safe Homes and Respect for Everyone.

Study design

Five of the six studies used a cluster RCT design (Abramsky et al. 2014; Jewkes et al. 2008; Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015) and one study utilized a quasi-experimental trial design (Kalichman et al. 2009). All six studies implemented fully powered trials to examine the efficacy of interventions (Abramsky et al. 2014; Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015).

Geography

Four studies took place in South Africa (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006) and two studies were implemented in Uganda (Abramsky et al. 2014; Wagman et al. 2015). No studies from western or central Africa were identified.

Target population

The target populations varied considerably. Importantly, only two of the six studies included in the authors' review specifically targeted youths or young adults (Jewkes et al. 2008; Mathews et al. 2016) The age range criteria in the youth-tailored interventions were defined as 16–23 years (Jewkes et al. 2008) and Grade 8 adolescents (Mathews et al. 2016). Three of the six studies included, but did not specifically target, adolescents, with inclusion criteria for age ranges defined as 15–49 years (Wagman et al. 2015), 18–49 years (Abramsky et al. 2014), and 18 years and older (S. Kalichman, personal communication, March 22, 2018). One study did not provide age specifications for direct recipients of the intervention, but gathered data on intervention impact from two cohorts of participant household members 14–35 years old (Pronyk et al. 2006).

Among the four studies that did not specifically target adolescents or students, participants were recruited based on their identification as general community members (Abramsky et al. 2014; Kalichman et al. 2009), enrollment in existing cohort studies (Wagman et al. 2015), or loan eligibility (Pronyk et al. 2006). Among the six studies, one exclusively recruited male participants (Kalichman et al. 2009) and one delivered the intervention exclusively to female participants, but gathered additional outcome data from male and female community members (Pronyk et al. 2006).

Control condition

Two of the studies used control groups that were wait-listed to receive the intervention after the trial was complete (Abramsky et al. 2014; Pronyk et al. 2006), two control groups received routine health services (Mathews et al. 2016; Wagman et al. 2015), and two control groups received one 3-h session on HIV risk, without mention of IPV (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009).

Intervention dose and format

Four studies implemented the intervention activities in group settings (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006) and two studies at the community level (Abramsky et al. 2014; Wagman et al. 2015). The interventions typically prescribed lengths for each session, ranging from 1-h (Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006) to 3-h (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009). The two community mobilization studies did not include or prescribe specific lengths for intervention activities (Abramsky et al. 2014; Wagman et al. 2015).

The dosages of the interventions sessions varied considerably. Kalichman et al. (2009) implemented five 3-h sessions over the course of five consecutive days. Other studies implemented intervention activities on a weekly or biweekly basis over the course of 6–8 weeks (Jewkes et al. 2008), 21 weeks (Mathews et al. 2016), or 6–9 months (Pronyk et al. 2006). Abramsky et al. (2014) and Wagman et al. (2015) implemented community mobilization activities without prespecified dosage over the course of roughly 4 years. The intervention settings varied between and within studies. Intervention locations included schools (Mathews et al. 2016), HIV clinics (Wagman et al. 2015), local media channels (Abramsky et al. 2014), microfinance loan centers (Pronyk et al. 2006), and community settings (Abramsky et al. 2014; Kalichman et al. 2009; Wagman et al. 2015).

Intervention approaches

Four of the six studies aimed to reduce perpetration and experience of IPV (Abramsky et al. 2014; Jewkes et al. 2008; Mathews et al. 2016; Wagman et al. 2015). One study exclusively targeted IPV perpetration (Kalichman et al. 2009) and one study focused specifically on reducing experience of IPV (Pronyk et al. 2006). HIV outcomes included sexual risk behaviors and biological outcomes: concurrent sexual partners (Abramsky et al. 2014; Kalichman et al. 2009; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015); reported condom use (Kalichman et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015); transactional sex (Mathews et al. 2016), and sexual debut (Mathews et al.., 2016), as well as HIV acquisition (Jewkes et al. 2008; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015).

Three studies implemented structural interventions to target the social and economic environments influencing HIV and IPV risk. Intervention activities included microfinance programs and community mobilization events to address cultural norms toward violence (Abramsky et al. 2014; Pronyk et al. 2006; Wagman et al. 2015). The other studies can be described as multicomponent interventions, in which group-based activities target modifiable individual behaviors, structural level causes of HIV and IPV risk, and attitudes toward gender equality. The multicomponent intervention activities focused on modification of individual risk behaviors, addressed beliefs relating to gender equality, and built sexual health skills (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2016). The six studies are grouped by intervention approach and described below:

Structural interventions

SASA! is a community-level mobilization intervention targeting IPV and sexual-risk behavior reduction among individuals 18–49 years of age living in Kampala, Uganda (Abramsky et al. 2014). Participants in communities receiving the intervention were exposed to various activities led by trained Community Activists (CAs), including group discussions, public events, trainings, and films. The intervention activities aimed to reduce social acceptability of IPV among community members to reduce perpetration and victimization, as well as sexual risk behavior reduction addressing the increased risk of HIV associated with concurrent sexual partners among male participants. The intervention did not have a prescribed dosage of intervention exposure, but supported the CAs progression through the program's phases and strategies. More than 11,000 activities were implemented during the duration of the study. The control group was wait-listed for the intervention. The average age of men and women in the intervention group and control groups fell within the range of 27–29 years. The study did not report the proportion of participants 18 years of age. Comparison of baseline and follow-up data demonstrated that the intervention was associated with reduced social acceptance of IPV among women (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] 0.54, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.38–0.79), and increased acceptance among women that women can refuse sex (aRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.07–1.52). SASA! was not associated with statistically significant reductions in overall IPV incidence, although the study reported reductions in experience of past-year physical IPV among female participants in the intervention group compared with the control group (aRR 0.48, 95% CI 0.16–1.39). The intervention was associated with decreased sexual risk behaviors, measured by self-reports of concurrent sexual partners among nonpolygamous men (aRR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36–0.91).

IMAGE is a combined microfinance and gender training intervention targeting women in the Limpopo province of South Africa (Pronyk et al. 2006). The intervention and control villages each contained three cohorts to study the direct and indirect impact of the intervention: eligible female loan recipients (average age 41 years) in cohort 1, 14–35 years old household members of the loan recipients in cohort 2, and randomly sampled community members comprising cohort 3. The total study population was 6576. The study did not report the proportion of participants 14–18 years of age, but reported the youngest participants' age in cohort 2 (16.9 years) and cohort 3 (17.1 years). The women in cohort 1 directly received loans through a group lending model. Loan groups held a total of 10 1-h meetings every other week for support, discussion of credit, business assessments, and repayment. Within the 1-h loan meetings, the intervention delivered structured trainings through the Sisters for Life gender and HIV training program. Phase 1 of the structured training included 10 sessions during which participants and trained team leaders explored topics of gender, IPV, HIV, and relationship skill building. In Phase 2 of Sisters for Life, the intervention included community mobilization activities, including identification and training of natural leaders in each village, development of locally tailored action plans for each village, and continued assistance from the training team for 6–9 months. Participants in the control villages were wait listed to receive the intervention. At follow-up, the study assessed past-year experience of IPV in cohort 1, unprotected sex with nonspousal partners among cohort 2 participants, and HIV incidence in cohort 3 using laboratory-based diagnoses. IMAGE was associated with decreased experience of IPV in cohort 1 (aRR 0.45, 95% CI 0.23–0.91). The intervention was not associated with increased protection during sex among cohort 2 participants or HIV incidence in cohort 3.

SHARE addressed IPV and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda (Wagman et al. 2015) using community mobilization, individual counseling, and group-based strategies. Study participants were 15–49-year-old individuals (N = 11,448) recruited from the existing Rakai Community Cohort Study. Among the study population, 10% (N = 1167) of participants were 15–19 years of age. Individuals in the intervention group were exposed to a range, but no prescribed dosage, of intervention activities, including marches, distribution of learning activities, posters, and newsletters. The aim of the intervention activities was to change social attitudes regarding IPV and reduce perpetration and experience of IPV, while concurrently addressing various sexual risk behaviors related to multiple sexual partners, nonmarital sexual partners, condom use, and alcohol use before sexual activity.

SHARE included intervention activities specifically targeting GBV through group programming for men and boys (e.g., IPV and HIV risk reduction group sessions led by male leaders), in addition to activities targeting young adults through peer group discussions on topics related to healthy relationships and safe sex. Women in the intervention group seeking HIV services were also given a brief intervention to reduce the risk of IPV related to HIV disclosure. The control group received standard HIV services offered through the ongoing cohort study, which included HIV prevention and treatment, HIV testing, counseling, and care referral. Analysis of self-reported experience and perpetration of IPV found that the intervention was associated with decreased past-year experience of physical IPV (adjusted prevalence risk ratio [aPRR] 0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.92), sexual IPV (aPRR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67–0.97), and forced sex (aPRR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.96) among women. The intervention was neither significantly associated with decreased incidence of emotional IPV among women nor self-reported IPV perpetration among men. At the 35-month follow-up, laboratory-based diagnoses demonstrated a negative association between exposure to SHARE and HIV acquisition within the intervention group (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.97), with statistically significant reduction in HIV acquisition among male participants (aIRR 0.59, 95% CI 0.35–0.95), but not female participants (aIRR 0.72, 95% CI 0.49–1.07) in the intervention.

Multicomponent interventions

PREPARE is a school-based intervention designed to reduce experience and perpetration of IPV, increase condom use, and delay sexual debut among Grade 8 adolescents (N = 3451) in the Western Cape Province, South Africa (Mathews et al. 2016). Over the course of 21 weeks, participants (average age 13) in the intervention group attended weekly 1–1.5 h educational sessions facilitated group discussion of IPV, relationships, sexual decision-making, gender and power inequity, communication skills, and sustainable community change. The school health service included free weekly access to a PREPARE nurse for “health checks,” screenings, and referrals related to participants' sexual health. The school safety program educated school community members about IPV prevalence, laws related to sexual violence, and school safety planning. Participants in the control group attended school and did not receive any additional programming. Results from the 12-month follow-up surveys found that PREPARE was not significantly associated with delayed sexual debut, condom use, or number of sexual partners. The intervention was associated with decreased report of experience of IPV (odds ratio [OR] 0.77, 95% CI 0.61–0.99).

Kalichman et al. (2009) recruited male participants 18 years and older (N = 475) from two townships in Cape Town, South Africa to compare the effects of a trial IPV/HIV intervention with an HIV/alcohol intervention on IPV perpetration and risk of STI. Over the course of 1 week, men in the intervention group (average age 30.2 years, standard deviation 9.5 years) participated in five 3-h integrated GBV and HIV risk-reduction sessions. The study did not provide details on the proportion of participants 18 years of age. The intervention activities included exploration of GBV/HIV risk identification and reduction through condom use skill building, behavioral role play with group feedback and discussion with South Africa media clips for context, and advocacy skill building. The control group received one 3-h session on HIV/alcohol risk reduction that did not include GBV or IPV intervention material. HIV outcomes measured sexual risk history characteristics, including the results of the participants' most recent HIV test, as well as assessments of AIDS knowledge, AIDS-related stigma, sexual risk-reduction behavioral intentions, and self-reports of concurrent sexual partners, condom use, and sexual communication. The study found that the field trial was not significantly associated with increased condom use, decreased number of sexual partners, or decreased occurrence of unprotected sex. At the 6-month follow-up, the field trial was associated with decreased perpetration of past-month physical IPV (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.4). Participants who at baseline reported that they had lost their temper with a woman, men in the intervention group were less likely to report losing their temper compared with men in the control group at 6-month follow-up (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8).

Stepping Stones is a participatory intervention designed to reduce HIV, herpes simplex type 2 among young men and women 15–26 years old (N = 2776) living in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa (Jewkes et al. 2008). Over the course of 6–8 weeks, participants in the intervention group attended 13 3-h long single-sex group meetings, three mixed-sex peer meetings, and one community meeting. Intervention activities were both group and individual based, including a variety of participatory role play, drama, and critical reflection exercises to facilitate exploration of gender equity and healthy relationships. The study designed the activities to reduce experience and perpetration of IPV, as well as sexual behaviors that increase risk of STI. The study delivered a 3-h session on safe sex, condoms, and HIV to the control group. Stepping Stones, while not associated with reduced HIV incidence, was able to demonstrate 33% reduction in Type 2 herpes simplex virus (aIRR 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.97). The study was also associated with a lower proportion of male participants reporting IPV perpetration at 2-year follow-up in the intervention group compared with the control (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.62, 95% CI 0.38–1.01).

Discussion

For this systematic review, the authors examined the geographic distribution, study design, and target population of six interventions designed to reduce IPV and HIV risk in Sub-Saharan African settings. Even though the field of integrated IPV/HIV prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa is in its nascent stages, it is encouraging that six interventions have been conducted with rigorous study designs. For researchers in the field of adolescent IPV and HIV prevention, the authors' findings suggest a significant need for age-tailored interventions for young people facing the dual risk of IPV and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. A larger evidence base will allow future meta-analyses to examine effective sexual risk and violence prevention strategies among adolescents. They have identified some of key strengths and gaps in the literature below. A summary of core implications of the current review for practice, policy, and research is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Implications of the Review for Practice, Policy, and Research

| Area of impact | Implications of the review |

|---|---|

| Practice | • The findings of this review suggest that integrated IPV/HIV interventions show promise as a sexual risk and violence prevention strategy among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. |

| Policy | • Policy makers interested in preventing HIV and IPV should be aware of the dual risk pathways, and that policies in support of risk reduction in one may affect rates of the other (and vice versa). |

| • HIV and IPV risk reduction policy should address the mechanisms by which gender and economic inequities affect rates of sexual risk behaviors and violence against women. | |

| Research | • Targeting adolescents in integrated IPV/HIV interventions would provide further evidence regarding effective age-specific strategies for sexual risk behavior reduction and violence prevention. |

| • Research on integrated IPV/HIV interventions would benefit from consistent biological outcomes and standardized IPV outcomes to improve rigorous, comparable measurement across studies. | |

| • Research examining concurrent IPV/HIV prevention should examine specific gender-targeted approaches to increase men and boys' involvement in promoting and normalizing gender equality. |

Geographic distribution of the studies

Findings indicate that integrated IPV/HIV interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa have been rigorously evaluated in regions of Sub-Saharan Africa with the greatest burden of IPV and HIV. The six studies were conducted in eastern and southern African countries, in which 19.4 million adults and children are living with HIV, compared with 6.1 million in western and central African countries (UNAIDS 2017). Southern and eastern Sub-Saharan Africa also report high IPV prevalence, with lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual abuse as high as 90% in this region (United Nations 2012). In South Africa, where four of the six interventions took place, the lifetime prevalence of physical and sexual abuse is 49% (United Nations 2012).

Their findings also point to a regional gap in the literature, as no integrated IPV/HIV trials emerged from western or central African countries. This finding supports the need for increased HIV/AIDS prevention and intervention efforts in western and central African countries, where HIV prevalence rates, although lower than central and southern African countries, are not met with adequate treatment provision and transmission prevention (Djomand et al. 2014; Médecins Sans Frontières 2016). Previous studies in West Africa have found high prevalence rates and social acceptance of IPV, including experience of dating violence among university-aged women and IPV among women living with HIV/AIDS (Diallo and Voia 2016; Olorunsaiye et al. 2017; Olowookere et al. 2015; Umana et al. 2014).

Considering the high IPV and HIV prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa, it is surprising that not more than six studies fulfilling inclusion criteria emerged in their search. The authors recommend that future researches assess the efficacy of integrated IPV/HIV interventions in all regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, as the documented burden of both IPV and HIV demonstrates the pressing need for evidence-based interventions.

Study design elements

The results of their review demonstrate that integrated IPV/HIV interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa have been implemented with rigorous research methods. The RCTs large sample sizes are a key strength among the studies, indicating that the majority of current research is producing meaningful results through fully powered trials. The researchers reported unbiased allocation of clusters of participants to receive the intervention or comparative treatment, which can help minimize the potential for contamination between the two groups (Torgerson 2001).

The included studies' control groups represented a range of comparison conditions, which lent varying strength to the studies' results. Importantly, three studies compared integrated IPV/HIV interventions with HIV-focused services or risk reduction trainings, which demonstrates growing interest in the potential for combined IPV/HIV prevention to reduce a number of related sexual and interpersonal risk behaviors.

Target population

The authors' results are encouraging with respect to the number of studies that are included, although they did not always specifically target adolescents. PREPARE and Stepping Stones targeted early and late adolescence, respectively (Jewkes et al. 2008; Mathews et al. 2016); only PREPARE's study sample was entirely within 13–18 years old. Furthermore, although SHARE included participants as young as 15 years old, the reported impact of SHARE does not disaggregate the data by age to show the effect of intervention among younger participants. Similarly, IMAGE included participants as young as 14 years old in cohort 2 and cohort 3, however, the results did not provide evidence of diffusion of the intervention among household and community members. The six studies' inclusion criteria for participant ages varied considerably, ultimately making it difficult to compare the effect of the interventions across same age adolescents.

Their finding that participants in IPV/HIV interventions are generally older coincides with study populations, in which there is evidence of current romantic relationships, cohabitation, IPV experience, IPV perpetration, concurrent sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use at baseline. Indeed, even among the youngest participants included in PREPARE's study, at baseline, 22% of the Grade 8 participants reported sexual debut, 45% had experienced IPV, and more than a quarter had perpetrated IPV (Mathews et al. 2016), indicating that secondary prevention strategies are needed for this age group. The findings suggest that while the majority of current research on integrated IPV/HIV examines secondary prevention intervention strategies among populations with preexisting risk or incidence of IPV and HIV, there exists an important gap in the current research on IPV/HIV primary prevention strategies among adolescents.

Addressing gender norms and identifying sexual risk behaviors during adolescence are crucial for primary prevention of both IPV and HIV (McCloskey et al. 2016; Mwale and Muula 2017). The wide range of included ages among many of the studies limits the ability of intervention activities to include appropriate developmental tailoring, particularly among adolescent participants who may not have relationship or sexual experience. This indicates an important gap in the current research. They recommend developmentally appropriate interventions that tailor all aspects of content and activities to the target population based on specific factors, including risk behavior, gender, and, importantly, age (Pedlow and Carey 2004).

Adolescence is marked by cognitive maturation, increased risk-taking, and development of decision-making skills, all of which may benefit from extended training with age-specific skill-building opportunities to increase the impact of interventions (Pedlow and Carey 2004). In addition, within the period of adolescence remain distinct phases of sexual development that require age-tailored interventions (Pedlow and Carey 2004). Sexual risk interventions targeting youths in preadolescence may focus on primary prevention and establish safe behaviors to promote safe relationships and delay sexual debut, as seen in PREPARE (Mathews et al. 2016).

Alternatively, interventions targeting older adolescents who may already be sexually active need to focus on secondary prevention through skill building and reducing sexual risk behaviors, including inconsistent condom use and multiple sex partners (Mwale and Muula 2017). Developmental and age-tailored interventions would align intervention programming with key milestones relating to both risk and opportunity for IPV and HIV prevention such as puberty, initiation of first intimate relationships, and initial sexual debut. A developmental and age-tailored approach might also leverage family involvement in interventions during earlier adolescence and peer influence in later adolescence. The present review indicates that further research needs to examine the age-specific effects of IPV/HIV interventions to determine the most effective prevention strategies for primary prevention during adolescence and secondary prevention as adolescents' transition to adulthood.

Another significant finding of their review is the active engagement of male participants in five of the six studies. Five of the six interventions aimed to reduce IPV perpetration among the study population. This is highly promising and demonstrates that the current research on IPV/HIV is addressing the important role men must play in IPV prevention (Carlson et al. 2015). One intervention was delivered exclusively to male participants (Kalichman et al. 2009), while two other studies divided participants into single-sex groups to receive the intervention (Jewkes et al. 2008; Pronyk et al. 2006). The authors are encouraged by the specific focus on young men that has emerged in the field of integrated HIV and IPV prevention, since gender targeting may be an effective means of promoting community-wide gender equality and normalizing safe sexual behaviors (Peacock and Levack 2004).

The review found that the interventions targeting HIV and IPV risk among male participants implemented skill-building activities to promote sexual communication and condom use, as well as group discussions and role play to explore the topics of HIV and IPV risk, attitudes toward women, and healthy relationships (Jewkes et al. 2008; Kalichman et al. 2009). These strategies are aligned with previous literature calling for HIV and gender-targeted interventions to increase “space for boy's voices” to direct the discourse on masculinity, identity, and renegotiation of power within relationships (Thorpe 2012).

Intervention strategies

Their review found that both structural and behavioral approaches are being used to concomitantly reduce IPV and HIV risk in Sub-Saharan Africa. The structural interventions primarily addressed the economic and social environments that contribute to gender inequity and increased risk of HIV. For example, interventions targeted aspects such as social norms, poverty, and mobilization of leaders and grassroots action to address social attitudes and resources for IPV and HIV. While the structural interventions in this review did not specifically target adolescents, previous research shows evidence of the positive impact of structural interventions that address the economic, political, and social environments of both IPV and HIV risk (Berkman et al. 2005; Bourey et al. 2015; Handa et al. 2014; Harrison et al. 2010). Addressing structural factors that impact adolescent sexual health may lead to more enduring risk reduction than behavioral interventions (DiClemente et al. 2007).

However, due to the significant variety of intervention activities, dosages, and outcome measures, it is difficult to assess whether structural or behavioral approaches were more effective in reducing IPV/HIV risk. Research has found that adolescent sexual and reproductive health is influenced by a combination of social and structural factors, including safe homes, parental communication, sustained livelihoods, and poverty (Bastien et al. 2011; Madise et al. 2007; Mosavel et al. 2012). It may be that both structural and individual behavioral components are needed in interventions; that is precisely the approach used by multicomponent interventions.

Importantly, the multicomponent interventions used various skill-building activities to enhance sexual communication, condom use, and personal beliefs surrounding gender equality. In fact, each of the six interventions underscored gender inequity as a social factor that contributes to IPV and HIV risk. These are important strategies to address the distinct gender disparities in HIV risk; the average odds of a Sub-Saharan African woman being infected with HIV is 60% higher than her male counterpart (Magadi 2011). A larger evidence base will allow future research to assess which structural and behavioral approaches are effective in reducing risk of IPV and HIV in the individual relationship and societal level.

Furthermore, because of the wide age ranges in the study samples, it is also difficult to know with certainty which interventions were most effective among adolescents and why. The limited number of school-based integrated IPV/HIV interventions in the review highlights another priority area for future research. Schools offer the opportunity to reach large numbers of young people, increase intervention exposure by building program elements into the existing curriculum, and address social norms related to gender equity and sexual risk behaviors in the school community (Harrison et al. 2010; Mathews et al. 2016; World Health Organization 2010).

Efficacy

The results show mixed results for the potential for integrated IPV/HIV prevention to reduce sexual risk behavior and improve gender equality among adolescents at the individual and community level. Two interventions were associated with decreased IPV, as indicated by reduced self-reports of experience of IPV (Mathews et al. 2016; Pronyk et al. 2006). One intervention demonstrated reductions in IPV perpetration and STI incidence, but not HIV (Jewkes et al. 2008). Three interventions were associated with both statistically significant reductions in IPV and HIV risk (Abramsky et al. 2014; Kalichman et al. 2009; Wagman et al. 2015).

However, the outcomes used to measure IPV and HIV reductions among these three interventions varied significantly, from social attitudes toward IPV (Abramsky et al. 2014) to self-reported incidence (Kalichman et al. 2009; Wagman et al. 2015). Similarly, the findings of Abramsky et al. (2014), Kalichman et al. (2009), and Wagman et al. (2015) represent intervention impacts on varied HIV outcomes, including both biological outcomes (Wagman et al. 2015) and self-reported sexual risk behavior reduction (Abramsky et al. 2014; Kalichman et al. 2009).

There was significant variation in how IPV and HIV were defined and measured across the six studies captured in this review. These differences present challenges for comparing across studies. Furthermore, all included studies relied on self-reports of IPV experience, perpetration, or measures of gender equitable attitudes that may introduce biases depending on the characteristics of the participant and the study's definition of IPV (Schroder et al. 2003; Waltermaurer 2005). Studies that measure both experience and perpetration of IPV in a community may be able to report reductions in IPV incidence more reliably than studies that measure either experience or perpetration of IPV exclusively.

In regard to HIV, half of the studies use biological outcomes to measure the interventions' effect on HIV risk reduction, while three studies used self-reported sexual risk behaviors, which is subject to reporting bias. Increasing use of biological outcomes in HIV prevention is challenging, but the results indicate that they need more studies that include rigorous, comparable measurement. The field of integrated IPV/HIV prevention will benefit from consistent definitions and conceptualizations of IPV and HIV risk.

It is encouraging that three studies resulted in statistically significant reductions in both IPV and HIV risks. However, the mixed efficacy of the six interventions is a surprising result and suggests that more work in intervention development and refinement is warranted. One area for increased attention is narrowing of interventions to target specific age and developmental stages within adolescence. Another area for increased attention is the dose of intervention and follow-up times. The included studies implemented the intervention over a significant range of time, from five consecutive days of 3-h sessions (Kalichman et al. 2009), to more than 11,000 community mobilization activities over the course of 4 years (Abramsky et al. 2014). The majority of the interventions implemented weekly or biweekly sessions. Importantly, the three interventions with demonstrated reductions in both HIV and IPV implemented intervention activities in either concentrated doses; Kalichman et al. (2009) exposed participants to 15 h of intervention material in 5 days, while the two community mobilization interventions delivered continuous activities over the course of roughly 4 years (Abramsky et al. 2014; Wagman et al. 2015). Further research is needed to examine the impact of different intervention dosages.

The follow-up period also varied considerably, with assessments ranging from 1 month to 4 years postintervention launch. Only one intervention (Pronyk et al. 2006) reported short duration of follow-up as a limitation to the study's findings. Although longer durations of study and extended follow-up assessments may increase the risk of follow-up attrition or contamination between study sites, the authors recommend that future research uses space follow-up assessments so as to measure the long-term impact of IPV/HIV interventions.

Overall, the findings are encouraging for integrated IPV/HIV interventions and have important implications for public health practice as well as public health policy. The demonstrated reductions in both IPV and HIV suggest that public health policy makers should be aware of the dual risk pathways that exist between both public health problems. Policies aiming to reduce IPV may also benefit HIV reduction efforts. Further research is needed to examine the existence and effect of current policies that address both risks among adolescents concurrently. However, the interventions' strategies and results demonstrate that policies promoting gender and economic equity may help reduce risk factors that influence sexual risk taking and violence against young women.

Limitations

The present findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The selected electronic databases and chosen search terms may not have provided access to all relevant studies. It is possible that the inclusion criteria and search terms around age did not capture all studies describing integrated IPV/HIV interventions using varying definitions of adolescence. The decision to include only peer-reviewed articles may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant reports or dissertations on the topic. Due to the wide range of intervention designs, delivery methods, outcome measurements, and limited number of existing interventions, it is difficult to compare efficacy across interventions using a meta-analytical approach. Half of the studies used self-reported sexual risk behaviors to measure HIV outcomes and all six studies used self-reported measures of experience of IPV, which allows for social desirability and recall bias to affect study results (Schroder et al. 2003). More rigorous biological measures of HIV and IPV are needed. Furthermore, it is difficult to assess the efficacy of the studies among adolescent participants as not all the studies provided disaggregated outcome data by age.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this review, interventions that integrate HIV and IPV prevention among adolescents are limited in number and are found in eastern and south African countries. The authors' analysis demonstrates that the majority of IPV and HIV interventions include both adult and older adolescent study populations and measure IPV and HIV outcomes in a range of ways. All included studies used group-based activities to promote gender equality and safer sexual norms. An expansion of prevention research is needed in other settings throughout Africa to develop additional approaches for reducing IPV and HIV among vulnerable adolescent populations.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by grant number R34MH113484 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH.

Appendix 1

Search Strategies

PubMed search string:

Search ((HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv OR hiv-1* OR hiv-2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno-deficiency virus OR human immune-deficiency virus OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus)) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune-deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome)) OR “sexually transmitted diseases, Viral”[MeSH:NoExp])) AND (“Adolescent”[MeSH] OR youth OR youths OR youngster OR teenager OR teenagers OR teen OR teens OR adolescent[mh] OR adolescent OR adolescents OR adolescence OR child[mh] OR child OR children OR young person* OR young people OR student OR students) AND (“Domestic Violence”[MeSH] OR intimate partner violence OR intimate partner abuse OR dating violence OR dating abuse OR relationship violence OR relationship abuse OR physical abuse[mh] OR adolescent relationship abuse OR adolescent dating abuse OR adolescent dating violence OR violence against women OR sexual assault OR sexual violence OR sexual abuse OR young people “Intimate Partner Violence”[Mesh]) AND (Africa OR Sub-Saharan OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cameroon OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR Cote d'Ivoire OR Djibouti OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mauritius OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR Sierra Leone OR Somalia OR “South Africa” OR Sudan OR Swaziland OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Uganda OR “Western Sahara” OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe).

Embase search string:

((('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection') AND ([embase]/lim OR [medline]/lim)) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus') OR ('human immunodeficiency virus 1'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus 1') OR ('acquired immune deficiency syndrome'/exp OR 'acquired immune deficiency syndrome') OR ('serodiagnosis')) AND (('partner violence') OR ('domestic violence') OR ('dating violence') OR ('sexual assault') OR ('sexual violence') OR ('rape') OR ('sexual abuse')) AND (('juvenile') OR ('adolescent') OR ('child') OR ('adolescence') OR ('student') OR ('school age') OR ('young adult')) AND (('africa') OR ('africa south of the sahara') OR ('angola') OR ('angolan') OR ('benin') OR ('beninese') OR ('botswana') OR ('burkina faso') OR ('burkinabe') OR ('burundi') OR ('cameroon') OR ('cameroonian') OR ('cape verde') OR ('central africa') OR ('central african republic') OR ('central african') OR ('chad') OR ('comoros') OR ('congo') OR ('cote divoire') OR ('djibouti') OR ('equatorial guinea') OR ('eritrea') OR ('eritrean') OR ('ethiopia') OR ('ethiopian') OR ('gabon') OR ('gabonese') OR ('ghana') OR ('ghanaian') OR ('guinea') OR ('guinea-bissau') OR ('kenya') OR ('kenyan') OR ('lesotho') OR ('liberia') OR ('liberian') OR ('madagascar') OR ('malawi') OR ('malawian') OR (mali) OR ('mauritania') OR ('mauritius') OR ('mozambique') OR ('mozambican') OR ('namibia') OR ('namibian') OR ('niger') OR ('nigeria') OR ('nigerian') OR ('rwanda') OR ('rwandan') OR ('sao tome and principe') OR ('senegal') OR ('senegalese') OR ('seychelles') OR ('seychellene') OR ('sierra leone') OR ('sierra leonean') OR ('somalia') OR ('somali (citizen)') OR ('south africa') OR ('south african') OR ('sudan') OR ('sudanese') OR ('swaziland') OR ('swazi (people)') OR ('tanzania') OR ('tanzanian') OR ('togo') OR ('togolese') OR ('uganda') OR ('ugandan') OR ('western sahara') OR ('zambia') OR ('zambian') OR ('zimbabwe') OR ('zimbabwean')).

PsychInfo search string:

Search Alert: “((HIV Infections OR HIV OR hiv OR hiv-1* OR hiv-2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno-deficiency virus OR human immune-deficiency OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus)) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune-deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome)) OR “sexually transmitted diseases, Viral”)) AND ((“Adolescent” OR youth OR youths OR youngster OR teenager OR teenagers OR teen OR teens OR adolescent[mh] OR adolescent OR adolescents OR adolescence OR child[mh] OR child OR children OR young adult OR young person* OR young people OR student OR students)) AND (“Domestic Violence” OR intimate partner violence OR intimate partner abuse OR dating violence OR dating abuse OR relationship violence OR relationship abuse OR physical abuse OR adolescent relationship abuse OR adolescent dating abuse OR adolescent dating violence OR violence against women OR sexual assault OR sexual violence OR sexual abuse OR young people “Intimate Partner Violence”)) AND ((Africa OR Sub-Saharan OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cameroon OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR Cote d'Ivoire OR Djibouti OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mauritius OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR Sierra Leone OR Somalia OR “South Africa” OR Sudan OR Swaziland OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Uganda OR “Western Sahara” OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe)).

CINAHL search string:

Search Alert: “((HIV Infections OR HIV OR hiv OR hiv-1* OR hiv-2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno-deficiency virus OR human immune-deficiency OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus)) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune-deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome)) OR “sexually transmitted diseases, Viral”)) AND ((“Adolescent” OR youth OR youths OR youngster OR teenager OR teenagers OR teen OR teens OR adolescent[mh] OR adolescent OR adolescents OR adolescence OR child[mh] OR child OR children OR young adult OR young person* OR young people OR student OR students)) AND ((“Domestic Violence” OR intimate partner violence OR intimate partner abuse OR dating violence OR dating abuse OR relationship violence OR relationship abuse OR physical abuse OR adolescent relationship abuse OR adolescent dating abuse OR adolescent dating violence OR violence against women OR sexual assault OR sexual violence OR sexual abuse OR young people “Intimate Partner Violence”)) AND ((Africa OR Sub-Saharan OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cameroon OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR Cote d'Ivoire OR Djibouti OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mauritius OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR Sierra Leone OR Somalia OR “South Africa” OR Sudan OR Swaziland OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Uganda OR “Western Sahara” OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. (2014). Findings from the SASA! study: A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 12, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2002). Developing adolescence: A reference for professionals. https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/develop.pdf (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- Anderson JC, Campbell JC, Farley JE. (2013). Interventions to address HIV and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the literature. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 24, 383–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien S, Kajula LJ, Muhwezi WW. (2011). A review of studies of parent-child communication about sexuality and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health 8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman A, Garcia J, Muñoz-Laboy M, et al. (2005). A critical analysis of the Brazilian response to HIV/AIDS: Lessons learned for controlling and mitigating the epidemic in developing countries. Am J Public Health. 95, 1162–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourey C, Williams W, Bernstein EE, et al. (2015). Systematic review of structural interventions for intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries: Organizing evidence for prevention. BMC Public Health. 15, 1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J, Casey E, Edleson JL, et al. (2015). Strategies to engage men and boys in violence prevention: A global organizational perspective. Violence Against Women. 21, 1406–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koker P, Mathews C, Zuch M, et al. (2014). A systematic review of interventions for preventing adolescent intimate partner violence. J Adolesc Health. 54, 3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo SA, Voia M. (2016). The threat of domestic violence and women empowerment: The case of West Africa. Afr Dev Rev. 28, 92–103 [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. (2007). A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: Sustaining effects using an ecological approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 32, 888–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djomand G, Quaye S, Sullivan PS. (2014). HIV epidemic among key populations in West Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 9, 506–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K, Decker M. (2013). Gender-based violence and HIV: Reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am J Reprod Immunol. 69, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes R, Nduna M, et al. (2007). Transactional sex with casual and main partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: Prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Soc Sci Med. 65, 1235–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown H, et al. (2004a). Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: Prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med. 59, 1581–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown H, et al. (2004b). Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 363, 1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton L, Flisher A, Aarø L. (2003). Unsafe sexual behavior in South African youth. Soci Sci Med. 56, 149–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan M, Risher K, Zungu N, et al. (2016). Age-disparate sex and HIV risk for young women from 2002 to 2012 in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 19, 21310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher A, Myer L, Mèrais A, et al. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of partner violence among South African adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 48, 619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C, Watts C. (2000). Violence against women: Its importance for HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 14, S253–S265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa S, Halpern CT, Pettifor A, et al. (2014). The government of Kenya's cash transfer program reduces the risk of sexual debut among young people age 15–25. PLoS One. 9, e85473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Newell M-L, Imrie J, et al. (2010). HIV prevention for South African youth: Which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health. 10, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. (2010). Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. Lancet. 376, 41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. (2008). Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 337, 391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2017). UNAIDS data 2017. www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2014). The gap report. www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf [PubMed]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, et al. (2009). Integrated gender-based violence and HIV risk reduction intervention for South African men: Results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prev Sci. 10, 260–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman CE, Stavrou SE. (2002). “Bus fare, please”: The economics of sex and gifts among adolescents in urban South Africa. Population Council Policy Research Division Working Papers. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnada195.pdf

- Kim J, Martin L, Denny L. (2003). Rape and HIV: Post-exposure prophylaxis: Addressing the dual epidemics in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 11, 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick B, Shaffer A, Forehand R, et al. (2001). Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clin Psychol Rev. 21, 493–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Marshall C, Rees H, et al. (2014). Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 17, 18845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke N. (2003). Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in Sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 34, 67–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madise N, Zulu E, Ciera J. (2007). Is poverty a driver for risky sexual behaviour? Evidence from national surveys of adolescents in four African countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 11, 83–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magadi MA. (2011). Understanding the gender disparity in HIV infection across countries in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. Sociol Health Illn. 33, 522–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan N, et al. (2001). Women's barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: Challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care. 13, 595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan N, et al. (2002). HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: Findings from a voluntary counselling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Am J Public Health. 92, 1331–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C, Eggers SM, Townsend L, et al. (2016). Effects of PREPARE, a multi-component, school-based HIV and intimate partner violence (IPV) prevention programme on adolescent sexual risk behaviour and IPV: Cluster randomised controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 20, 1821–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Boonzaier F, Steinbrenner SY, et al. (2016). Determinants of intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of prevention and intervention programs. Partner Abuse. 7, 277–315 [Google Scholar]

- Médecins Sans Frontières. (2016). Out of focus: How millions of people in West and Central Africa are being left out of the global HIV Response. www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/HIV_AIDS/Docs/HIV_report_WCA_ENG_2016.pdf (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- Michielsen K, Temmerman M, Van Rossem R. (2013). Limited effectiveness of HIV prevention for young people in sub-Saharan Africa: Studying the role of intervention and evaluation. Facts Views Vision ObGyn. 5, 196–208 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosavel M, Ahmed R, Simon C. (2012). Perceptions of gender-based violence among South African youth: Implications for health promotion interventions. Health Promot Int. 27, 323–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munguti K, Grosskurth H, Newell J, et al. (1997). Patterns of sexual behavior in a rural population in north-western Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 44, 1553–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwale M, Muula AS. (2017). Systematic review: A review of adolescent behavior change interventions [BCI] and their effectiveness in HIV and AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 17, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olorunsaiye CZ, Brunner L, Laditka SB, et al. (2017). Associations between women's perceptions of domestic violence and contraceptive use in seven countries in West and Central Africa. Sex Reprod Healthc. 13, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olowookere SA, Fawole OI, Adekanle DA, et al. (2015). Patterns and correlates of intimate partner violence to women living with HIV/AIDS in Osogbo, southwest Nigeria. Violence Against Women. 21, 1330–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. (2008). A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 8, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock D, Levack A. (2004). The men as partners program in South Africa: Reaching men to end gender-based violence and promote sexual and reproductive health. Int J Mens Health. 3, 173–188 [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow CT, Carey MP. (2004). Developmentally-appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescents: Rationale, review of interventions, and recommendations for research and practice. Ann Behav Med. 27, 172–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Measham D, Rees H, et al. (2004). Sexual power and HIV risk, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 11, 1996–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. (2006). Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 368, 1973–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KEE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. (2003). Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 26, 104–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swart LA, Stevens MSG, Ricardo I. (2002). Violence in adolescents' romantic relationships: Findings from a survey amongst school-going youth in a South African community. J Adolesc. 25, 385–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Jemmott JB, Bellamy SL, et al. (2016). Partner violence, power and gender differences in South African adolescents' HIV/STI behaviors. Health Psychol. 35, 751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe M. (2012). Masculinity in an HIV Intervention. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity. 53, 61–68. (Last accessed on July1, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson DJ. (2001). Contamination in trials: Is cluster randomisation the answer? BMJ. 322, 355–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana JE, Fawole OI, Adeoye IA, et al. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence towards female students of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Womens Health. 14, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2012). Violence against women prevalence data: Surveys by country. www.endvawnow.org/uploads/browser/files/vawprevalence%0Amatrix_june2013.pdf%0A (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). (2017). Turning the tide against AIDS will require more concentrated focus on adolescents and young people. data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/# (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- van der Straten A, King R, Grinstead O, et al. (1998). Sexual coercion, physical violence, and HIV infection among women in steady relationships in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS Behav. 2, 61–73 [Google Scholar]

- Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, et al. (2015). Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: Analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. Lancet Global Health. 3, e23–e33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltermaurer E. (2005). Measuring intimate partner violence (IPV): you may only get what you ask for. J Interpers Violence. 20, 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/en (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf?ua=1 (Last accessed on July1, 2018)

- World Health Organization. (2010). Sexual determinants of sexual and reproductive health: Informing future research and programme implementation. apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44344/1/9789241599528_eng.pdf (Last accessed on July1, 2018)