Abstract

Cellular membranes are, in general, impermeable to macromolecules (herein referred to as macrodrugs, e.g., recombinant protein, expression plasmids, or mRNA), which is a major barrier for clinical translation of macrodrug-based therapies. Encapsulation of macromolecules in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) can protect the therapeutic agent during transport through the body and facilitate the intracellular delivery via a fusion-based pathway. Furthermore, designing LNPs responsive to stimuli can make their delivery more localized, thus limiting the side effects. However, the principles and criteria for designing such nanoparticles remain unclear. We show that the thermodynamic state of the lipid membrane of the nanoparticle is a key design principle for acoustically responsive fusogenic nanoparticles. We have optimized a cationic LNP (designated LNPLH) with two different phase transitions near physiological conditions for delivering mRNA. A bicistronic mRNA encoding a single domain intracellular antibody fragment and green fluorescent protein (GFP) was introduced into a range of human cancer cell types using LNPLH, and the protein expression was measured via fluorescence corresponding to the GFP expression. The LNPLH/mRNA complex demonstrated low toxicity and high delivery, which was significantly enhanced when the transfection occurred in the presence of acoustic shock waves. The results suggest that the thermodynamic state of LNPs provides an important criterion for stimulus responsive fusogenic nanoparticles to deliver macrodrugs to the inside of cells.

Keywords: lipid nanoparticle, LNP, mRNA, shock wave, intracellular antibody fragment, transfection

Introduction

Many human diseases involve abnormal protein–protein interactions (PPIs) that affect normal biological processes. Modulation of PPIs is attracting increasing interest in basic and disease biology. While there are increasing numbers of examples of successful development of compounds that interfere with PPI,1 the interaction surface between proteins are often large and discontinuous, which make conventional small-molecule inhibitors difficult to isolate. As an alternative to drug-like compounds, investigations into macromolecules that specifically interfere with PPIs have led to some notable success, for example, with peptides,2 proteins,3,4 and DNA/RNA/peptide aptamers.5−7 Using such macromolecules (so-called macrodrugs8) to target PPIs is an approach that builds on molecular biology rather than chemistry because macrodrugs are capable of both specificity and high affinity on target molecules.

The variable regions of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (VH) and light chain (VL) are minimal fragments that can recognize antigens9 and these have been demonstrated to specifically bind proteins inside cells and therefore is termed as iDabs (intracellular domain antibodies).10 The efficacy of iDabs was shown using an anti-RAS VH single domain.3 RAS proteins are frequently mutated in human cancers, and aberrant RAS function leads to constitutive signal transduction associated with hyper-proliferative and developmental disorders.11 Inhibition of tumor growth by interfering PPIs between RAS and its interaction partners in vivo using an intracellular antibody fragment has been shown to be effective in inhibiting tumor initiation and tumor growth. However, most of the disease targets, including RAS, are located inside cells, making it necessary to deliver intracellular antibody fragments as macrodrugs. This could be achieved using recombinant protein and nucleic acid coding for the protein. Protein molecules can be immunogenic, and are generally unstable that makes it difficult to achieve a therapeutic concentration in vivo. It is therefore impractical to directly deliver protein molecules across the plasma membrane into cells.12 Delivering exogenously produced protein-coding nucleic acid, such as DNA and mRNA, into cells, to achieve continuous production of the protein drug in situ is an alternative approach.13,14 However, introducing mRNA, compared to DNA that was commonly introduced by viral vectors, does not integrate into host genome because natural degradation pathways of mRNA also ensure that the protein expression is transient and avoids unwanted long-term effects. The translation of protein from mRNA mostly occurs in the cytoplasm, so delivering mRNA avoids the need to transport across the nuclear membrane.14 Therefore mRNA delivery will potentially result in a more efficacious protein expression than via plasmid DNA delivery.

Nonetheless, intracellular nucleic acid delivery remains a major challenge for large-molecule therapeutics. The scientific problems associated with delivering therapeutic mRNA are fundamentally different from the passive intracellular delivery of small-molecule drugs as the cell membrane selectively prevents large molecules entering cells. From a thermodynamic perspective, the energy barrier and the kinetics of crossing the cellular membrane are related to the size and hydrophilicity of the molecule.15,16 The energy barrier is higher for larger and more hydrophilic molecules to such an extent that practically no mRNA crosses the cellular membrane passively. An added challenge with mRNA-based therapeutics is that they require shielding from serum-based degradation and from the immune system until they are inside the target cells.

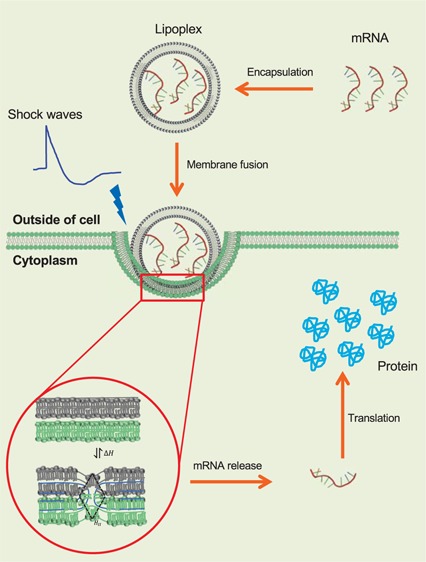

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and lipid–nucleic acid-complexed nanoparticles (lipoplexes) can potentially provide solutions to these problems, both as a safe carrier of the macrodrug to the target cell and as an agent that forms an intermediate with the cell membrane delivering the therapeutic via fusion between LNP and the plasma membrane (Figure 1A,B).17−22 The rate of delivery depends on the energy barrier that needs to be overcome to form the LNP/cell fusion intermediate, also known as a stalk, which corresponds to the lipid membranes deforming from a lamellar Lα phase to an inverse hexagonal HII phase (see Figure 1B). While stalk-mediated fusion is a particular example of the endocytosis mechanism, in general, by making the nanoparticle more compliant to deformation, its contribution to the activation energy for internalization can be minimized, which is critical even for receptor-mediated endocytosis.23 Ultimately, thermodynamic fluctuations or other physical stimuli have to overcome this barrier to allow the internalization of the nanoparticle irrespective of the specific molecular mechanism involved. Therefore, there are three ways to increase the probability of the system attaining activation enthalpy of fusion enhancing nanoparticle uptake; (1) lower the energy barrier, (2) increase the thermodynamic fluctuations, and (3) couple an external physical stimulus (e.g., acoustic waves), all of which are employed here. The energy barrier for the fusion intermediate can be lowered by designing the nanoparticle close to the Lα → HII transition. The thermodynamic fluctuations as well as the coupling into acoustic waves are directly related to the heat capacity of the nanoparticle, which is maximized near an order–disorder transition (Lα → Lβ).24 Because the system has to operate under the physiological condition, the aim was to design an LNP/mRNA complex that has both the transitions near the physiological condition. It has recently been established how acoustic impulses can induce state changes in LNPs.24 Our work presents a continuation of concerted efforts toward establishing a systematic and unified thermodynamic approach for localized and enhanced intracellular delivery of macrodrugs using acoustic stimulation. We combine principles of material science, interface physics, biophysics, and molecular biology starting from macroscopic effects of the acoustic impulse and how it leads to nanoparticle internalization. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first instance where acoustic state changes have been employed as a strategy for macrodrug intracellular delivery. Here, we show that an EDPPC/cholesterol-based nanoparticle,25 designed to have both transitions at physiological conditions, is a potent transfection agent that can efficiently deliver a bicistronic mRNA molecule, encoding an anti-RAS intracellular antibody fragment, into several different mutant RAS-expressing human cancer cell lines. We further show that these transfected cells are also susceptible to acoustic treatment using shock waves, as expected from their thermodynamic state, which results in significant increase in transfection and protein translation of sensitive cell lines.

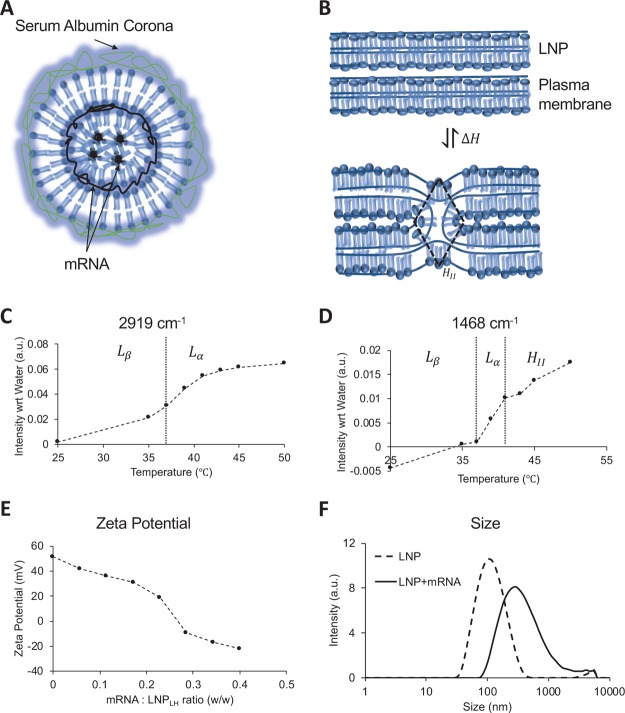

Figure 1.

Physical characteristics of the lipid nanoparticle. (A) Schematic of the LNP–mRNA complex. Amphiphilic lipid molecules are drawn to show the lamellar fluid phase (Lα) and inverted hexagonal (HII) phase coexistence. mRNA molecules assemble in the intralamellar space of the Lα phase or the hydrophilic core of the HII phase. When incubated with plasma, a serum albumin corona forms around the shells shielding the positive charge of the nanoparticle. (B) Intermediate stalk formation during the fusion of two lamellar bilayers is shown take place via the (HII) phase. The transition occurs via reversible exchange of enthalpy ΔH. (C) Peak intensity in FTIR spectra of the LNP at 2919 cm–1 measured as a function of temperature. The peak corresponds to the stretching of −CH2 bonds and identifies the gel (Lβ) to fluid (Lα) transition near 37 °C.27 (D) Peak intensity in FTIR spectra of the LNP at 1468 cm–1 measured as a function of temperature. The peak corresponds to the scissoring of −CH2 bonds and identifies two kinks corresponding to gel (Lβ) to fluid (Lα) transition near 37 °C and lamellar fluid (Lα) and inverted hexagonal (HII) transition near 41 °C.27 (E) Zeta potential of LNP/mRNA lipoplex as a function of mRNA titrated reported as the w/w ratio on x axis. The w/w ratio of 0.2 in the vicinity of the isoelectric point was used as initial estimate for the optimum mRNA to LNP ratio (F) size distribution of the lipid nanoparticles measured using a Zetasizer before and after association with the native mRNA at the w/w ratio of 0.2 (zeta potential 19.1 mV).

Results

LNP and Lipoplex Characterization

The ideal lipoplex for in vivo use will have both the lamellar fluid phase to inverted hexagonal phase transition (Lα → HII) and lamellar fluid phase to lamellar gel phase (Lα → Lβ) transition close to physiological conditions and potentially an external stimulus can be used to trigger phase transition that will enhance the fusion of the lipoplex with the cell. A formulation based on EDPPC and cholesterol (70:30, mol/mol), described previously,25 has a Lα → Lβ transition at 37 °C and a Lα → HII transition at 41 °C. The presence of these transitions was confirmed in our experiment using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra (Figure 1C,D). We have designated this formulation LNPLH. In addition, two other formulations were designed: LNP1 to have a strong tendency to undergo nonlamellar transitions upon mixing with negatively charged lipids found in cell membranes and LNP2 which has transition temperatures lower than LNPLH, so the lipids are in the highly fluid state. LNP1 was formulated with cationic homologues of dilauroyl (EDLPC) and dioleoyl (EDOPC) lipids, which at a 60:40 composition have been previously reported to form an inverted micellar cubic phase upon mixing with the negatively charged lipids, resulting in enhanced synergistic transfection.26 LNP2 was formulated with EDPPC and 1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoe- thanolamine (DEPE), which at a 60:40 ratio has a broad Lα → Lβ transition at 28 °C and a Lα → HII transition at 37 °C.25

The specific lipoplex structure that forms when mRNA is incorporated into the LNPLH was assessed by the zeta potential of the lipoplex. Figure 1E shows that the zeta potential of the LNPLH alone (no mRNA) is 50 mV, which is consistent with the presence of cationic lipids. The LNPLH sample was prepared from the dried lipid film by rehydration and extrusion as described in the Experimental Section. Concentrated mRNA was titrated into the LNPLH sample and the zeta potential monitored as the mRNA/LNPLH ratio increased. The zeta potential decreases monotonically because of the incorporation of negatively charged mRNA into positively charged LNP. There is a relatively sharp drop as the mRNA/LNP ratio increases from 0.23 to 0.28 at which point the zeta potential becomes negative and, as the concentration of mRNA is further increased, the zeta potential continues to decrease monotonically. The drop around the mRNA/LNP ratio of 0.25 is typical for the internalization of mRNA during the LNP/mRNA complex formation that follows the accumulation of mRNA at the LNP surface (for microscopic details of the process and the intermediate steps20). These experiments gave an initial estimate for the optimal mRNA to the LNPLH ratio of 20:100 (w/w), and this was further optimized with the use of cell-based transfection experiments (see below). Figure 1F shows the size distribution of lipoplex before and after the association with the native mRNA at the w/w ratio of 0.2 (zeta potential 19.1 mV), which shows that the mean diameter increases from 112 to 302 nm and the distribution polydispersity index increases from 0.254 to 0.334 upon formation of the lipoplex. The optimal mRNA to LNP ratio determined in the zeta potential experiments was further tested with RiboGreen RNA assay and generally more than 95% of total mRNA in the system was associated with LNP.

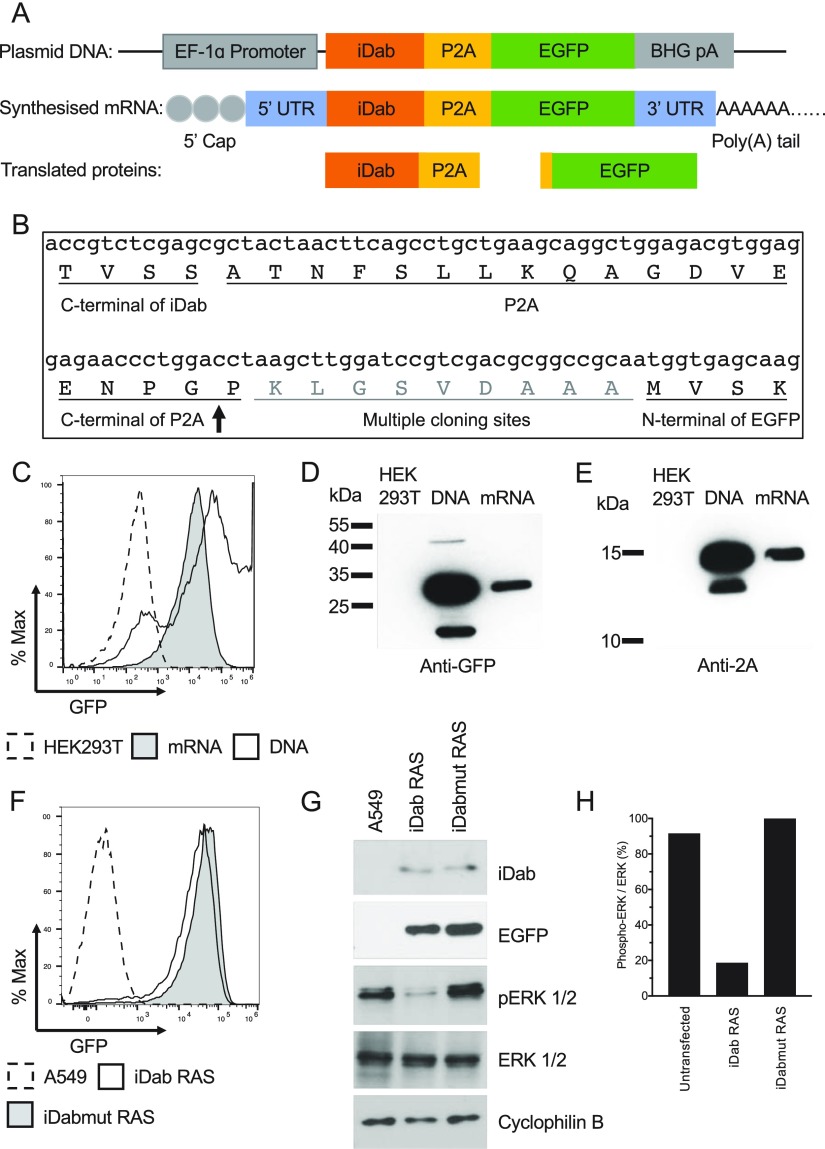

The bicistronic mRNA expression used for our study is illustrated in Figure 2A comprises an mRNA encoding an iDab and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), in a bicistronic format including a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 (P2A) that allows the iDab and EGFP expressed simultaneously from one transcript. Figure 2B illustrates the junction nucleic acid and protein sequences at the end of the iDab, the P2A, and the start of EGFP. The expression of iDab from the mRNA is reported by the expression of EGFP, which can be detected with fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. The bicistronic plasmid DNA was generated by cloning the iDab-P2A-EGFP expression cassette into a plasmid that has a human elongation factor-1 alpha (EF-1 alpha) promoter, and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. The iDab-P2A-EGFP was used as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template for in vitro transcription of the bicistronic mRNA. A modified version of bicistronic mRNA was also synthesized with uridine-5′-triphosphate being replaced with pseudo-uridine-5′-triphosphate (pseudo-UTP) for an improved stability of the nucleic acid.

Figure 2.

Bicistronic plasmid DNA encoding iDab and green fluorescent protein (EGFP) panel (A) shows the schematic representation of the expression plasmid and the corresponding in vitro synthesized mRNA encoding the single domain-intracellular antibody fragment (iDab) and EGFP that are separated by porcine teschovirus-1 2A peptide sequence. The synthesized mRNA has a 5′cap and a 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTR) before a poly(A) tail of >150 bases. EF-1α Promoter, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1; BGH pA, bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. Following the transcription of the mRNA and translation, two proteins are made, viz., EGFP and iDab with a P2A tag. The junction RNA and amino acid sequences are shown in panel (B). The ribosome-skipping site between P2A and EGFP is indicated by the arrow. Bicistronic plasmid DNA or in vitro transcribed mRNA using native nucleotides were transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, cells were collected and EGFP fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry (C) and the protein expression analyzed by western blot with antibody detecting the P2A tag of the iDab (D) or antibody detecting GFP (E). HEK293T, untransfected HEK293T cells; DNA, cells transfected with plasmid DNA; mRNA, cells transfected with bicistronic mRNA. The bicistronic mRNA synthesized with pseudo-UPT was transfected into A549 cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 7 h incubation, cells were collected and analyzed for the GFP expression by flow cytometry (F) and lysed and analyzed for the expression level of various protein using western blot (G). Inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK was determined by the ratio of phospho-ERK to total ERK for each sample (H). A549, untransfected A549 cells; iDab RAS, cell transfected with bicistronic mRNA iDab RAS-2A-EGFP; iDabmut RAS, cell transfected with bicistronic mRNA iDabmut RAS-2A-EGFP. iDab RAS is an anti-RAS single-domain intracellular antibody and iDabmut RAS is a mutant form that is expressed but no longer binds to RAS protein.

Both the plasmid and the naked, native mRNA were transfected into HEK293T cells (a human embryonic kidney cell line) using Lipofectamine 2000 and the translation products were confirmed using flow cytometry of EGFP fluorescence (Figure 2C) and western blot using antibody detecting GFP (Figure 2D) or detecting the 2A tag on the iDab (Figure 2E) 24 h after transfection. While there are reports of inefficient ribosome recognition of the 2A skipping sequence,28 in this case, very little iDab-EGFP fusion protein was observed (Figure 2D). It was also noted that transfection with the plasmid DNA was only about 30% of cells, while almost all cells transfected with mRNA showed the EGFP expression (Figure 2C). However, the levels of GFP fluorescence were higher in the plasmid transfection than mRNA. Both an anti-RAS VH iDab (iDab RAS) and a mutant form of anti-RAS VH iDab (iDabmut RAS) that has only three amino acids mutated from iDab RAS but no longer binds to RAS protein3 was also constructed to the bicistronic expression system. Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 that harbor a homozygous KRASG12S allele was used to test the iDab RAS and iDabmut RAS. The modified version of both bicistronic mRNAs was introduced into A549 cells and the expression of the iDab RAS and iDabmut RAS was first indicated by the expression of EGFP (Figure 2F) and confirmed using western blot (Figure 2G). The persistent stimulation of the MAPK/ERK signal pathway, caused by the constitutive activation of mutant KRAS in A549 cells, was efficiently inhibited by iDab RAS, expressed from the introduced bicistronic mRNA, by 5-fold compared to the mutant form iDabmut RAS that did not show inhibition of the Ras-dependent pathway (Figure 2H). This showed that there was sufficient intracellular antibody expression to interfere with the RAS-effector PPI.

Assessment of mRNA Delivery to Human Cells Using LNP1, LNP2, and LNPLH

All three LNP formulations were tested for delivery of a fluorescently labeled mRNA lacking a polyA tail, which was synthesized in vitro using fluorescein-12-UTP instead of native UTP, into HEK293T cells. The fluorescent signals in the FITC channel from cells delivered with mRNA by different LNP formulations were compared using confocal microscopy and fluorescence-activated flow cytometry (FACS). The formulations delivered the fluorescent mRNA into HEK293T cells at different efficiencies (Figure S1, Supporting Information) with LNPLH that has both Lα → Lβ and Lα → HII transitions close to physiological conditions, showing higher efficiency than LNP1 or LNP2.

Variable Cellular Uptake and mRNA Delivery by LNPLH

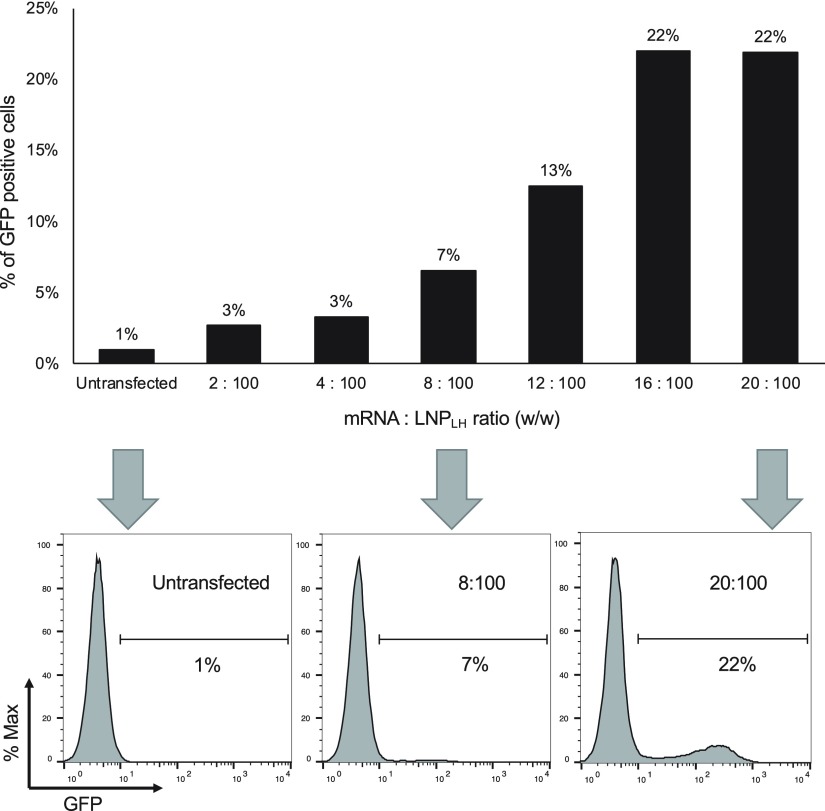

The most efficient lipoplex appeared to be LNPLH and therefore this formulation was used for subsequent experiments. Initial experiments of zeta potential measurements of mRNA titrations with the LNPLH-suggested association with the mRNA synthesized using native nucleotides were optimal at the mRNA to the LNPLH ratio of 20:100 (w/w) (Figure 1E). This loading ratio was optimized for the best transfection by transfecting HEK293T cells using the same amount of mRNA complexed with LNP at various mRNA to LNP ratios from 2:100 to 20:100 (w/w). The result showed that the transfection levels appear to saturate at an mRNA to LNP ratio of 16:100 and 20:100 (w/w) (Figure 3) and a ratio of 20:100 was used in subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Optimization of the mRNA to LNP ratio for lipoplex production. LNPLH was complexed with mRNA at the different weight ratios indicated from 2:100 to 20:100 mRNA/LNP and were compared by transfection in HEK293T cells. Transfection levels were assessed by flow cytometry and are represented as the percentage of cells showing GFP fluorescence (upper panel). Representative flow cytometry results of the indicated mRNA/LNPLH ratios were indicated with arrows and shown in the lower panel.

The mRNA was protected by the encapsulation in the LNPLH and the stability of the mRNA within the lipoplex was confirmed after recovery from prepared particles (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Further protection for the mRNA was achieved by the use of a modification in which uridine-5′-triphosphate was replaced with pseudo-UTP, known to increase the nuclease stability and enhance mRNA translation while showing innate immune suppression.29 The antireverse cap analog (ARCA) was also used to improve translatable mRNA yield and to achieve better transfection efficiency. We observed that the modified mRNA gave rise to higher fluorescence when transfected in A549 cells (Figure S3A, Supporting Information) and mRNA was released and expressed from both LNPLH and Lipofectamine 2000 (Figure S3B, Supporting Information).

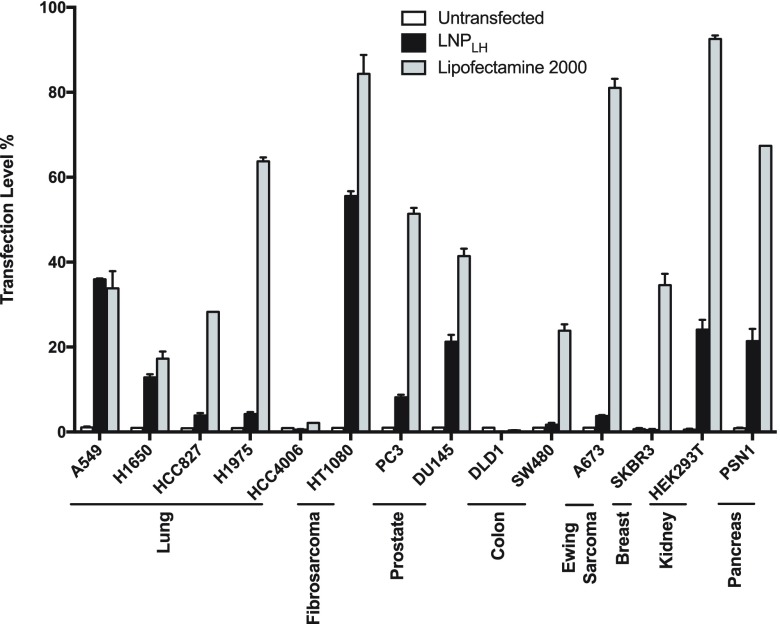

The ability of the LNPLH lipoplex to deliver mRNA and release it for translation into protein was assessed with an array of human cell lines, derived from different cancer types, using an LNP to mRNA ratio of 20:100 (w/w). The translation of the mRNA following delivery by the LNPLH was quantified by the fluorescent signal from the EGFP expression, compared to transfection with commercially available Lipofectamine 2000. The transfected cells were incubated for 24 h before analyzing using flow cytometry and the transfection level, which is represented by the gated GFP-positive cell population was normalized to the low background, auto-fluorescence signal (∼1%) from the untransfected cells. HEK293T cells transfected with mRNA using Lipofectamine 2000, as the positive control, displayed about 92% of the viable cells with the EGFP expression. Figure 4 shows the results for 14 cell lines, including HEK293T cells. In the main, we observed best transfection efficiency with the commercial transfection reagent (although toxicity was also much higher, see below). However, the LNPLH/mRNA complex significantly delivered mRNA that could be translated into the reporter EGFP protein in eleven of the fourteen cell lines tested, with four cell lines A549, HT1080, DU145, and PSN1 exhibiting greater than 20% delivery. There were three cell lines that did not result in enhanced delivery: DLD1 (colorectal), SW480 (colorectal), and HCC4006 (lung). With the possible exception of colorectal cancer lines, there was no obvious cell type bias mRNA delivery. However, some cell lines show high LNPLH delivery of the mRNA that may indicate properties yet to be elucidated that can be exploited for increasing cargo release.

Figure 4.

LNPLH transfection of a human cancer cell line panel with the bicistronic mRNA LNPLH/mRNA complex was prepared using the 20:100 w/w ratio of mRNA/LNP and used to transfect lung cancer cell lines (A549, H1650, HCC827, H1975, and HCC4006), a fibrosarcoma cell line (HT1080), prostate cancer cell lines (PC3 and DU145), colorectal cell lines (DLD1 and SW480), a Ewing Sarcoma cell line (A673), a breast cancer cell line (SKBR3), a pancreatic cancer cell line (PSN1), and embryonic kidney cells HEK293T. The percentage of cells with GFP fluorescence was analyzed using flow cytometry and the values converted to percentages of the maximum count using FlwoJo software as shown in the histograms. Lipofectamine 2000 was used as control for mRNA transfection. Data shown as mean values ± standard deviation of 3 or more samples.

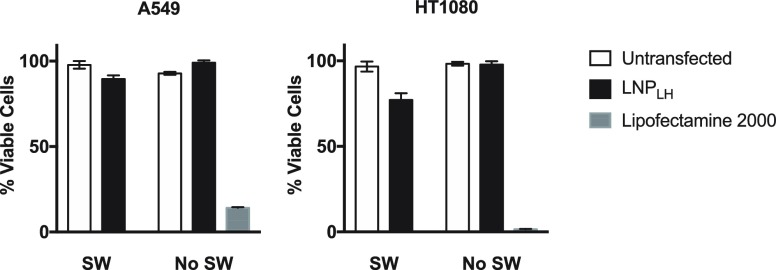

The toxicity of the LNPLH/mRNA complex was investigated using CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay on the two cell lines (A549 and HT1080) that displayed the highest levels of the GFP expression after transfection. Cells were incubated with the LNPLH/mRNA complex for 24 h before the cell viability was determined. The viability of A549 and HT1080 cells that were transfected with LNP/mRNA was not significantly reduced compared with the viability after mRNA transfection using Lipofectamine 2000, in which A549 viability was 14% after 24 h and HT1080 viability was 1.5% after 24 h (Figure 5). Cells were usually assayed for protein translation 24 h after transfection; however, it was also noticed that the cell viability and morphology were not significantly affected even after 72 h after treatment (data not shown). Thus, although Lipofectamine 2000 generally resulted in better translatable mRNA delivery than the LNPLH/mRNA, it also resulted in a much smaller number of viable cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of LNPs on cell viability. Two cell lines (A549 and HT1080) were transfected by mRNA using either LNPLH or Lipofectamine 2000 and cell viabilities were analyzed using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay at 24 h after transfection. Alternatively, 500 shock waves (energy setting P10 of a Swiss PiezoClast) were applied to cells after LNPLH/mRNA complex had been added to the cultures and cells incubated for 24 h before cell viability assay. SW, samples exposed to shock wave; no SW, samples without shockwave treatment. Data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation of 3 or more samples.

Shock Waves Promote the mRNA Delivery Using LNPLH

The ability of LNPs to deliver nucleic acids to cells and release their cargo for transcription/translation is an important objective. One goal of this work is to develop ways to enhance mRNA delivery and release in order to impart a therapeutic function to these macrodrugs. The use of pressure waves such as shock waves is one possible method to influence cell structure and LNP conformational state that might facilitate macrodrug release, but this may have deleterious effect of cell viability. The effect of shock waves on viability was investigated with A549 and HT1080 cell lines. Immediately after LNPLH/mRNA transfection, 500 shock waves were delivered at energy setting P10 (see Experimental Section), and cell viability was compared with LNPLH/mRNA transfected cells that were not treated with shock waves. Cells that were treated with shock waves after transfection by LNPLH showed minimal loss of viability (10% for A549 or 23% for HT1080). This compares favorably with loss of viability observed when using Lipofectamine 2000, where loss of viability ranged from 86% to 98% (Figure 5).

The most likely mechanisms by which shock waves interact with lipid membranes is either through direct stress or through cavitation. Therefore, we employed different energy level settings and different doses of shock waves to determine the optimal combination. Accordingly, we transfected the A549, HT1080, HEK293T, and PSN1 (all which had exhibited good transfectability, Figure 4) using setting P5, that is, below the cavitation threshold in this experimental system and P10, that is, above the cavitation threshold (see Experimental Section) with different doses of shock waves. Transfection was analyzed after 24 h by monitoring the EGFP expression from the LNPLH cargo mRNA (Figure 6A). When shock waves were applied, we observed an increased percentage of cells showing the GFP signal compared to no shock waves. We also noted a marked shift in the population toward higher fluorescence intensity in the presence of LNPLH lipoplex, which is further quantified with median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in the presence or absence of shock waves, for all four cell lines. The effect is most prominent in HEK293T cells, followed by A549, PSN1, and HT1080. Thus, exposure to shock waves improves the population of cells showing the EGFP expression. However, the peak signal itself is not affected significantly by the shock waves, implying that the peak intensity is probably limited by the rate of translation and not the delivery (discussed below). Figure 6B plots average expression levels obtained using different shock wave settings, showing that both an increase in the energy level as well as the number of shock waves increases the efficiency of the process.

Figure 6.

Shock waves improve the delivery of mRNA to cells by LNPLH. The mRNA was delivered to four human cell lines (HEK293T, A549, HT1080 and PSN1) with LNPLH/mRNA lipoplex with or without shock wave treatment and the GFP fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry after 24 h. Representative FACS overlay plots of GFP signals from cells transfected with lipoplex and treated with shock waves at indicated settings (grey area) were compared with lipoplex transfected cells without shock waves treatment (solid line) are showed in panel (A). In panel (B), all four cell lines were transfected with lipoplex and treated with various settings of shock waves as indicated. The expression levels of GFP after each treatment were represented using relative MFI by subtracting the MFI of the untreated samples (UN). UN, untransfected; Lipoplex, mRNA was delivered into cells using lipoplex SW, samples exposed to shock waves; no SW, samples without shockwave treatment. Data shown as mean values ± standard deviation of 3 or more samples.

Discussion

Intracellular Delivery of mRNA Using LNPLH

The implementation of macromolecule drugs (defined as macrodrugs8 as opposed to small-molecule drugs) for intracellular therapy has enormous implications because of the range of molecules (nucleic acids and proteins) that can be selected and optimized by molecular biology techniques. However, the challenges of delivering macrodrugs to cells continue to impede progress. There are at least two strategic issues. One is the vehicle of choice and the other is the macromolecule cargo. In the work presented here, we have developed an LNP as the vehicle and modified mRNA as the macrodrug. As proof-of-concept, we made a bicistronic mRNA coding for an intracellular antibody fragment that binds to KRAS3 and an EGFP separated by 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1.30 We confirmed that our in vitro synthesized mRNA was functional by transfecting into A549 cells and detecting GFP fluorescence by flow cytometry, which means that mRNA is released from the LNPs and protein synthesis occurs in the cells (Figure 2F). Further, we compared the effect of the anti-RAS iDab with a mutant version, that has only 3 amino acid changes compared to iDab RAS but does not bind to KRAS. While the EGFP that was expressed from mRNA of both the antibody fragments (Figure 2F), only the iDab RAS mRNA protein product was able to inhibit the phosphorylation of the ERK biomarker downstream of KRAS signaling (Figure 2G,H).

Intracellular delivery of nucleic acid using viral systems is often limited by unwanted immune responses, but nonviral materials, such as lipid-based nanoparticles (LNP) and polymer-based materials, have been developed to evade antigenicity.31−34 Some of these nanomaterials are at the stage of clinical trials to deliver siRNA35 and mRNA.36 Nonetheless, the identification of effective and safe delivery systems remains one of the biggest challenges for intracellular mRNA delivery.

The delivery of nucleic acid using cationic lipids is generally nonspecific but still a wide variety of cells are difficult to transfect probably because of the individual physical properties and composition of the phospholipid membranes. We have employed knowledge of the thermodynamics of lipid membranes25 to identify the formulation of EDPPC/cholesterol (LNPLH) that has two phase transitions, Lα → Lβ and Lα → HII, close to body temperature (Figure 1), from which we designed an LNP/mRNA complex optimized for entry into target cells and could be triggered by shock waves. Even in the absence of shock waves, the presence of these fusion-facilitating transitions exhibited transfection activity comparable to that of Lipofectamine 2000 in a number of cell lines (Figure 4). Using shock waves resulted in enhanced delivery in HEK293T, A549, and PSN1 cells but not in HT1080 cells (Figure 6). These results suggest that the LNPLH formulation may need to be tuned for specific cell targets.37 For therapeutic applications, additional lipids (e.g., PEGylated lipids) are usually required to improve the delivery of the LNP, therefore the ratios of each component may also need to be adjusted accordingly to keep both phase transitions close to the physiological conditions when designing the multicomponent LNP.

Challenges in mRNA Delivery Using LNPLH

The mRNA was protected by encapsulating with the LNPLH (depicted in Figure 1A). Although a comparable percentage of cells showed protein expression when the mRNA was introduced by both LNPLH and Lipofectamine 2000 (Figure 4), the expression level of protein in cells with mRNA delivered by LNPLH is still lower than those transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Therefore, the iDab translated from LNPLH-mediated mRNA delivery was not sufficient to show significant inhibition on the RAS-dependent signaling pathway, unlike Lipofectamine 2000 (Figure 2G). It is noted that when modified mRNA was incorporated into the LNP, the difference in transfection was minor (Figure S3, Supporting Information) suggesting that the limiting steps for the protein expression from LNPLH-mediated mRNA delivery could be the endosomal escape of the lipoplex and/or the release of the mRNA from the lipoplex. The phase transition of LNPLH triggered by shock waves could enhance the fusion of the lipoplex with both the cell membrane and the endosome membrane; therefore, a higher percentage of cells with mRNA delivered by LNPLH showed improved protein expression when shock waves were applied (Figure 6). However, it should be noted that the peak of the GFP signal intensity was about 10-fold weaker for the mRNA delivered with LNPLH compared to the same cell types that were transfected with modified mRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Figure S3, Supporting Information). This is presumably because LNPLH protects mRNA from degradation but also hinders ribosome access to mRNA. Therefore, the kinetics of release of mRNA from LNPLH is a parameter that could be improved to achieve better protein synthesis. This may also explain the second peak (or a tail) of the stronger GFP signal, comparable with mRNA transfected by Lipofectamine 2000, evident when the lipoplex (modified mRNA/LNPLH) to cell ratio was increased (Figure S3B, Supporting Information). However, the above interpretation assumes GFP fluorescence is directly proportional to protein expression, which is only a first order approximation.38

A main goal of this study was to demonstrate that the acoustic control of the state of a liposome can affect its transfection efficiency and to explore a new method to improve the mRNA delivery across the cell membrane utilizing the external stimulus. The propensity of LNPLH to undergo both Lα → Lβ and Lα → HII transitions after small perturbations, together with its significant activity in HEK293T cells even in the absence of shockwaves, makes LNPLH a promising candidate for acoustic control of transfection activity. While the proximity to Lα → Lβ and Lα → HII transitions in the initial state diagram of the LNPLH makes it very likely that these transitions, and hence transfection, occur upon the interaction of LNPLH with various cell lines and shock waves, the presence of these transitions in the initial state diagram is not necessary and such transition can emerge from the interaction of the cells and the LNP itself. In fact, LNP1 has previously been shown to induce such synergistic transitions upon interaction with negatively charged lipids. However, such transitions cannot be predicted without a comprehensive biophysical understanding of such synergistic interactions with native cellular membrane, especially in the presence of shock waves, which is beyond the scope of this work. Given the complexity of cellular membranes that is challenging to mimic artificially, a systematic approach will require a proper access to the thermodynamic state of the cellular membrane during such interactions, which remains experimentally challenging. Therefore, LNPLH is not necessarily the most optimal solution but an important starting formulation for our perturbation-based approach. The expression level of protein depends not only on the amount of mRNA that entered the cells but also other factors including endosome release39 and translational regulation in each cell type. In this experiment, the protein was detectable suggesting the mRNA was successfully delivered across the cell membrane and released into the cytoplasm while the cell viability was not affected compared to the lipofectamine 2000 system. The LNP could potentially be equipped with functional lipids such as ionizable lipids40 to promote the intracellular release, biodegradable lipids to improve biocompatibility, and PEGylated lipids to improve the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the LNP for future in vivo use. Furthermore, immuno-LNP with antibody against cell-specific surface marker conjugated to the LNP would allow the LNP/mRNA lipoplex to localize to target sites and facilitate the targeted delivery of mRNA to specific cell types for therapeutic applications.

Conclusions

Our work has highlighted the importance of the thermodynamic state of the lipid interface as a design principle for nanoparticles, in particular, that having the interfacial-lipids close to two-phase transitions enhances intracellular delivery through both passive endocytosis and amplification of coupling to an external stimulus. This is important because the focus is usually on the molecular structure of the various constituents of the nanoparticles, with limited attention to the thermodynamic state. This work has demonstrated that thermodynamically designed LNPs can deliver mRNA to various types of cancer cells in vitro and that the delivery efficiency is significantly enhanced in the presence of shock waves. The transfection efficiency was dependent on the cell type when the LNPLH formulation was employed and therefore it may be that a better understanding of cellular biophysics (i.e., the role of cell membrane composition and physical selectivity due to inherent nonlinearity of phase transitions) will allow the design of LNPs that are selective for predetermined cell types. In many clinical applications, this could be a benefit for the design of cell-selective LNPs that would result in reduced off target delivery.

Experimental Section

Preparation and Characterization of LNP

The 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-ethylphosphocholine (EDPPC) in chloroform (Avanti Polar Lipids 890702), 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-ethylphosphocholine (EDLPC, Avanti Polar Lipids 890700), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-ethylphosphocholine (EDOPC, Avanti Polar Lipids 890704), 1,2-dielaidoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphoethanolamine (DEPE, Avanti Polar Lipids 850726), cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich C8667-5G) and chloroform (ACROS Organics 364321000) were purchased and used without further purification. LNP1 was formed using 60:40 EDLPC/EDOPC mol ratio, LNP2 was prepared using EDPPC/DPPE at a 60:40 mol ratio, LNPLH was prepared using EDPPC and cholesterol at a 70:30 mol %. Lipids of each formulations were mixed in chloroform and dried either at room temperature in a glass vial overnight in a tissue culture hood or at 42 °C for 2 h using a rotary evaporator. The subsequent lipid film was hydrated with 1 mL of RNAse-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific 10977035) at 60 °C followed by vortexing and extrusion through a 400 nm polycarbonate filter (Avanti mini-extruder set) at 50 °C.

The FTIR spectrum was obtained using the attenuated total internal reflectance (Bio-rad spectrometer, FTS6000). The surface of the sensing prism was covered with the LNPLH emulsion at the concentration of 1.2 mg/mL and was covered by the temperature-controlling apparatus from top. Absorption spectra were recorded from wave numbers 400–4000 cm–1, with a resolution of 2 cm–1. Absorption spectra of RNAse-free water were linearly subtracted as the background signal. The size and zeta potential of LNPLH and the lipoplex were characterized using differential light scattering (Malvern Panalytical, Zeta Sizer). The LNPLH sample was prepared by diluting 40 μL of the LNPLH emulsion at the stock concentration of 1.2 mg/mL into 800 μL of RNAse-free water. To make the lipoplex, mRNA (252 ng/μL) was titrated in to the LNPLH emulsion at 25 °C and the zeta potential was measured for every 10 μL of mRNA added. The sizes were measured for pure LNPLH and for lipoplex at the optimized mRNA to LNPLH ratio (0.2 w/w). Samples were measured immediately after the addition of mRNA at 25 °C.

Construction of the Bicistronic Plasmid

Cloning was made using the VHExpress vector (Bradbury, Gene 1997)43 to replace the VH expression cassette of the original vector between PmlI and XbaI recognition sites by a multiple cloning site consists PmlI, NheI, PacI, NotI, BglII, and XbaI recognition sites. The sequence of the multiple cloning sites is CACGTGGCCAGCTAGCCCTGCAGGTTAATTAAGCGATCGCGGCGCGCCACTAGTGCGGCCGAGATCTTCTAGA. The resulting construct was termed pJEF vector. The EGFP coding sequence was PCR-amplified from the vector pEPI (a gift from Wade-Martins, University of Oxford, UK)41 using the forward primer 5′-AATTGCTAGCCTCGAGGGATCCTCTAGAGCGGCCGCAATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TTATTTAGATCTGAGTCCGGACTTGTAC-3′ and cloned into the pJEF vector between NotI and BglII recognition sites to construct the pJEF-EGFP vector. The bicistronic expression cassette iDab-P2A-EGFP for both iDab RAS and iDabmut RAS was designed to include the T7 promoter followed by N-terminal farnesylation sequence to the 5′ end. The forward primer for PCR amplification of iDab-P2A was 5′-ACCATTTTAATTAATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGAGCTCGAATTCACTAGTGCCGCCACCATGCTGTGCTGTATGAGAAGAACCAAACAGGTTGCCGAGGTGCAGCTG-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-ACCATTGCGGCCGCGTCGACGGATCCAAGCTTAGGTCCAGGGTTCTCCTCCACGTCTCCAGCCTGCTTCAGCAGGCTGAAGTTAGTAGCGCTCGAGACGGTGAC-3′.

The PCR product of iDab-P2A was cloned using PacI/NotI sites of the pJEF-EGFP vector to produce the bicistronic plasmid pJEF-iDab-2A-EGFP. The iDabs used in this study are anti-RAS VH and its inactivated mutant version.3

mRNA Synthesis

The iDab-P2A-EGFP fragment was PCR-amplified using forward primer 5′-GGGTTTTATGCGATGGAGTTTC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AAGAAAGCGAAAGGAGCG-3′ from the pJEF-iDab-2A-2EGP plasmid. The PCR products were used for mRNA synthesis. The mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Invitrogen AM1344) was used for in vitro transcription using native NTPs. The MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen AM1333) was used for mRNA synthesis using ARCA (NEB S1411S) and pseudo-UTP (Jena Bioscience NU-1139S) with a modified protocol. The reaction (1 μg of PCR product, 7.5 mM of ATP, CTP, and pseudo-UTP, 1.5 mM of GTP, 6 mM of ARCA, 2 μL of 10× reaction buffer and 2 μL of enzyme mix) was diluted to 20 μL of the final volume with nuclease-free water and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h followed by TURBO DNase (final concentration of 2 U/μL) treatment at 37 °C for 15 min. A poly(A) tail was added to the synthesized mRNA using a poly(A) Tailing Kit (Invitrogen AM1350). The fluorescently labeled mRNA was also synthesized with the MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit following the steps described above except the 10× concentrated Fluorescein RNA Labeling Mix (ROCHE 11685619910) was used as the NTP mixture. The fluorescently labeled mRNA was synthesized without poly(A) tailing. Synthesized mRNA was purified using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen 74134) and the concentration was measured using NanoDrop ND-8000.

RiboGreen RNA Assay

The mRNA was quantitated using the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Reagent (Invitrogen R11490). LNP/mRNA lipoplex was diluted in TE buffer or the same volume of TE buffer containing 1% of Triton X-100 (Triton buffer). The free mRNA in the system that was not incorporated with the LNP was quantitated from the sample in TE buffer. The total mRNA of both incorporated and free mRNA in the system was quantitated from the sample in Triton buffer. The mRNA associated with the LNP was calculated by subtracting the free mRNA (mRNA detected from the sample diluted in TE buffer) from the total mRNA (mRNA detected from the sample diluted in Triton buffer).

Cells Lines and Tissue Culture

Lung cancer cell lines A549, H1650, HCC827, H1975, and HCC4006, fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080, prostate cancer cell lines PC3 and DU145, colorectal cell lines DLD1 and SW480, Ewing sarcoma cell line A673, breast cancer cell line SKBR3, pancreatic cancer cell line PSN1, and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco 31966-021) medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma F7524) and penicillin streptomycin (Gibco 15140-122).

Transfection, Flow Cytometry, and Confocal Microscopy

The stock LNPLH (1.2 mg/mL) was diluted 5 times with Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific 31985070) to prepare the LNPLH working solution. The Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific 11668027) was prepared by diluting 3 μL of stock solution into 50 μL of Opti-MEM. The mRNA was prepared at 50 ng/μL with Opti-MEM and either the LNPLH working solution or the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent were mixed with an equal volume of diluted mRNA to yield the LNP/mRNA or Lipofectamine 2000/mRNA complexes. Cells cultured in a T75 flask was detached with trypsin before transfection and prepared at 300 000 cells/mL in DMEM with 10% FBS. Each 250 μL of cell suspension was mixed with 30 μL of LNP/mRNA or Lipofectamine 2000/mRNA complex in a thin-walled tube and treated with or without shockwave at 37 °C. Transfected cells were transferred to 48-well plates and incubated for 24 h before flow cytometry analysis using Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a forward scatter (FSC-area)/side scatter (SSC-area) plot for gating live cells followed by an FSC-height/FSC-area plot for doublet discrimination. The GFP-positive population was gated on the single-cell population terming 1% of the GFP signal from the background in the negative control (untransfected cells).

Viability Assays

Cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay (Promega G7573). Cells were cultured in 96-well plates and, after transfection, were incubated for 24 h, the medium was removed and 100 μL of the CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to each well and mixed by gentle shaking. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and the luminescence recorded using a plate reader (PerkinElmer, 2103 Envision).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were transfected with DNA or mRNA and, after 6 h of incubation, were detached with trypsin (Gibco 25300054), washed with PBS, and lysed with lysis buffer 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 1% (w/v) SDS, 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor (Millipore 535140), and 1% (v/v) phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific 78402) following with sonication using Diagenode Bioruptor Pico with settings of 30 s on, 30 s off, 10 cycles at 4 °C. The protein concentration of the whole lysate was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific 23225), and 15 μg of the total protein for each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane; proteins were detected by western analysis with the antibodies below and visualized using an electrochemical luminescence (ECL) detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific 34079). Antibodies used were anti-2A (Millipore ABS31), anti-GFP (Santa Cruz sc-9996), and anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling 9101S) as primary antibodies for the expression of iDab and EGFP and endogenous phosphorylated Erk1/2. Total Erk1/2 and cyclophilin B were detected using anti-Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling 9102S) and anti-cyclophilin B (Abcam, ab178397). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling 7074S) or anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling 7076S) were used as the secondary antibody for ECL detection.

Shock Waves

Shock waves were applied to the samples in thin-wall PCR tubes (Starlab I1402-2908). The cap of the PCR tubes was further sealed by wrapping parafilm wax around and was placed at the focus of the shockwave source in a temperature-controlled water tank at 37 °C. Shock waves were generated by a Swiss PiezoClast (EMS Electro Medical Systems S.A, Switzerland) and fired in to the water tank from below and focused at 1 cm below the free surface.24 The amplitude of the shock waves was controlled via energy level setting, which could be varied from P1 to P20. The focal waveforms consisted of a pulse about 5 μs in duration with a leading positive phase and trailing negative phase. At P5, the peak pressure amplitudes were 1.3 MPa for both phases and at P10 the peak pressure amplitudes was 2 MPa for the positive phase and 1.5 MPa for the negative phase.42 A fixed number of shockwaves were fired at a repetition rate of 3 Hz into one sample at a time. During this time, the rest of the samples were kept at 37 °C.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under Programme Grant EP/L024012/1 (OxCD3: Oxford Centre for Drug Delivery Devices) and partly by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award 099246/Z/12/Z and an MRC programme grant MR/J000612/1. The raw data for this paper is available from the Oxford University Research Archive (https://ora.ox.ac.uk).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b21398.

Confocal microscopy images and FACS plots of mRNA delivery using LNPs; western blot of in vitro synthesized protein from LNP/mRNA; and FACS plots of the protein expression after LNP/mRNA transfection (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.Z. and S.S. contributed equally. Originators of project: R.O.C., T.H.R. Participated in research design: all authors. Conducted experiments: J.Z. and S.S. Performed data analysis: all authors. Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arkin M. R.; Tang Y.; Wells J. A. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Protein-Protein Interactions: Progressing toward the Reality. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 1102–1114. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar A. A.; Reichert J. M. Future Directions for Peptide Therapeutics Development. Drug Discovery Today 2013, 18, 807–817. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.; Williams R. L.; Rabbitts T. H. Tumour Prevention by a Single Antibody Domain Targeting the Interaction of Signal Transduction Proteins with RAS. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3250–3259. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers-Casterman C.; Atarhouch T.; Muyldermans S.; Robinson G.; Hammers C.; Songa E. B.; Bendahman N.; Hammers R. Naturally Occurring Antibodies Devoid of Light Chains. Nature 1993, 363, 446–448. 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto M.; Sakamoto K.; Shirouzu M.; Hirao I.; Yokoyama S. RNA Aptamers That Specifically Bind to the Ras-Binding Domain of Raf-1. FEBS Lett. 1998, 441, 322–326. 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee S. M.; Rusconi C. P.; Sullenger B. A. Aptamers: An Emerging Class of Therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005, 56, 555–583. 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman R.; Yeh J. T.-H.; Laurenson S.; Ferrigno P. K. Design and Validation of a Neutral Protein Scaffold for the Presentation of Peptide Aptamers. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 352, 1118–1133. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.; Rabbitts T. H. Interfering with Protein-Protein Interactions: Potential for Cancer Therapy. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 1569–1574. 10.4161/cc.7.11.6061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E. S.; Güssow D.; Griffiths A. D.; Jones P. T.; Winter G. Binding Activities of a Repertoire of Single Immunoglobulin Variable Domains Secreted from Escherichia coli. Nature 1989, 341, 544–546. 10.1038/341544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.; Lobato M. N.; Rabbitts T. H. Single Domain Intracellular Antibodies: A Minimal Fragment for Direct in vivo Selection of Antigen-Specific Intrabodies. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 331, 1109–1120. 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjei A. A. Blocking Oncogenic Ras Signaling for Cancer Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 1062–1074. 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila A.; Sánchez A.; Tobío M.; Calvo P.; Alonso M. J. Design of Biodegradable Particles for Protein Delivery. J. Controlled Release 2002, 78, 15–24. 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann T.; Roblin R. Gene Therapy for Human Genetic Disease?. Science 1972, 175, 949–955. 10.1126/science.175.4025.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U.; Karikó K.; Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics - developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 759–780. 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. M.; Katz Y. Interpretation of Nonelectrolyte Partition Coefficients between Dimyristoyl Lecithin and Water. J. Membr. Biol. 1974, 17, 121–154. 10.1007/bf01870176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter A.; Gutknecht J. Permeability of Small Nonelectrolytes through Lipid Bilayer Membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1986, 90, 207–217. 10.1007/bf01870127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewert K. K.; Evans H. M.; Zidovska A.; Bouxsein N. F.; Ahmad A.; Safinya C. R. A Columnar Phase of Dendritic Lipid–Based Cationic Liposome–DNA Complexes for Gene Delivery: Hexagonally Ordered Cylindrical Micelles Embedded in a DNA Honeycomb Lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3998–4006. 10.1021/ja055907h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez I. M.; Cullis P. R. Roles of Lipid Polymorphism in Intracellular Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 47, 139–148. 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez I. M.; Maurer N.; Cullis P. R. On the Mechanism Whereby Cationic Lipids Promote Intracellular Delivery of Polynucleic Acids. Gene Ther. 2001, 8, 1188–1196. 10.1038/sj.gt.3301506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koynova R.; Tenchov B. Cationic phospholipids: structure-transfection activity relationships. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 3187–3200. 10.1039/b902027f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zelphati O.; Szoka F. C. Jr. Mechanism of Oligonucleotide Release from Cationic Liposomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 11493–11498. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Miao L.; Satterlee A.; Huang L. Delivery of Oligonucleotides with Lipid Nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 68–80. 10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Shi W.; Freund L. B. From The Cover: Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 9469–9474. 10.1073/pnas.0503879102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava S.; Cleveland R. O.; Schneider M. F. On Measuring the Acoustic State Changes in Lipid Membranes Using Fluorescent Probes. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 9702–9712. 10.1039/c8sm01635f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koynova R.; MacDonald R. C. Mixtures of Cationic Lipid O-ethylphosphatidylcholine with Membrane Lipids and DNA: Phase Diagrams. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 2449–2465. 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74668-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koynova R.; Wang L.; Tarahovsky Y.; MacDonald R. C. Lipid Phase Control of DNA Delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005, 16, 1335–1339. 10.1021/bc050226x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal H. L.; Mantsch H. H. Polymorphic Phase Behaviour of Phospholipid Membranes Studied by Infrared Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1984, 779, 381–401. 10.1016/0304-4157(84)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H.; Lee S.-R.; Li L.-H.; Park H.-J.; Park J.-H.; Lee K. Y.; Kim M.-K.; Shin B. A.; Choi S.-Y. High Cleavage Efficiency of a 2A Peptide Derived from Porcine Teschovirus-1 in Human Cell Lines, Zebrafish and Mice. PLoS One 2011, 6, e18556 10.1371/journal.pone.0018556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L.; Manos P. D.; Ahfeldt T.; Loh Y.-H.; Li H.; Lau F.; Ebina W.; Mandal P. K.; Smith Z. D.; Meissner A.; Daley G. Q.; Brack A. S.; Collins J. J.; Cowan C.; Schlaeger T. M.; Rossi D. J. Highly Efficient Reprogramming to Pluripotency and Directed Differentiation of Human Cells with Synthetic Modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 618–630. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felipe P.; Luke G. A.; Hughes L. E.; Gani D.; Halpin C.; Ryan M. D. E unum pluribus: multiple proteins from a self-processing polyprotein. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 68–75. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler C. R.; Bähr-Mahmud H.; Celik L.; Hebich B.; Roth A. S.; Roth R. P.; Karikó K.; Türeci Ö.; Sahin U. Erratum: Elimination of Large Tumors in Mice by mRNA-Encoded Bispecific Antibodies. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1241. 10.1038/nm1017-1241d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek J. C.; Patel A. K.; Kauffman K. J.; Fenton O. S.; Webber M. J.; Heartlein M. W.; DeRosa F.; Anderson D. G. Polymer-Lipid Nanoparticles for Systemic Delivery of mRNA to the Lungs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13808–13812. 10.1002/anie.201608450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. B.; Zhang S.; Kos P.; Xiong H.; Zhou K.; Perelman S. S.; Zhu H.; Siegwart D. J. Non-Viral Crispr/Cas Gene Editing in vitro and in vivo Enabled by Synthetic Nanoparticle Co-Delivery of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1059–1063. 10.1002/anie.201610209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball R. L.; Hajj K. A.; Vizelman J.; Bajaj P.; Whitehead K. A. Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for Enhanced Co-Delivery of siRNA and mRNA. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 3814–3822. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behlke M. A. Progress Towards in vivo Use of siRNAs. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 644–670. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richner J. M.; Himansu S.; Dowd K. A.; Butler S. L.; Salazar V.; Fox J. M.; Julander J. G.; Tang W. W.; Shresta S.; Pierson T. C.; Ciaramella G.; Diamond M. S. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell 2017, 168, 1114–1125 e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto O.; Rosendahl P.; Mietke A.; Golfier S.; Herold C.; Klaue D.; Girardo S.; Pagliara S.; Ekpenyong A.; Jacobi A.; Wobus M.; Töpfner N.; Keyser U. F.; Mansfeld J.; Fischer-Friedrich E.; Guck J. Real-Time Deformability Cytometry: On-the-Fly Cell Mechanical Phenotyping. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 199–202. 10.1038/nmeth.3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsliger M.-A.; Wachter R. M.; Hanson G. T.; Kallio K.; Remington S. J. Structural and Spectral Response of Green Fluorescent Protein Variants to Changes in pH†,‡. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 5296–5301. 10.1021/bi9902182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majzoub R. N.; Wonder E.; Ewert K. K.; Kotamraju V. R.; Teesalu T.; Safinya C. R. Rab11 and Lysotracker Markers Reveal Correlation between Endosomal Pathways and Transfection Efficiency of Surface-Functionalized Cationic Liposome-DNA Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 6439–6453. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b04441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple S. C.; Akinc A.; Chen J.; Sandhu A. P.; Mui B. L.; Cho C. K.; Sah D. W. Y.; Stebbing D.; Crosley E. J.; Yaworski E.; Hafez I. M.; Dorkin J. R.; Qin J.; Lam K.; Rajeev K. G.; Wong K. F.; Jeffs L. B.; Nechev L.; Eisenhardt M. L.; Jayaraman M.; Kazem M.; Maier M. A.; Srinivasulu M.; Weinstein M. J.; Chen Q.; Alvarez R.; Barros S. A.; De S.; Klimuk S. K.; Borland T.; Kosovrasti V.; Cantley W. L.; Tam Y. K.; Manoharan M.; Ciufolini M. A.; Tracy M. A.; de Fougerolles A.; MacLachlan I.; Cullis P. R.; Madden T. D.; Hope M. J. Rational Design of Cationic Lipids for siRNA Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 172–176. 10.1038/nbt.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persic L.; Roberts A.; Wilton J.; Cattaneo A.; Bradbury A.; Hoogenboom H. R. An integrated vector system for the eukaryotic expression of antibodies or their fragments after selection from phage display libraries. Gene 1997, 187, 9–18. 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lufino M. M. P.; Manservigi R.; Wade-Martins R. An S/Mar-based Infectious Episomal Genomic DNA Expression Vector Provides Long-Term Regulated Functional Complementation of LDLR Deficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, e98 10.1093/nar/gkm570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava S.; Cleveland R. State Changes in Lipid Interfaces Observed During Cavitation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 141, 3740. 10.1121/1.4988229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.