SUMMARY

Calcium imaging using two-photon scanning microscopy has become an essential tool in neuroscience. However, in its typical implementation, the tradeoffs between fields-of-view, acquisition speeds and depth restrictions in scattering brain tissue pose severe limitations. Here, using an integrated systems-wide optimization approach combined with multiple technical innovations, we introduce a new design paradigm for optical microscopy based on maximizing biological information while maintaining the fidelity of obtained neuron signals. Our modular design utilizes hybrid multi-photon acquisition and allows volumetric recording of neuroactivity at single-cell resolution within up to 1×1×1.22mm volumes at up to 17Hz in awake behaving mice. We establish the capabilities and potential of the different configurations of our imaging system at depth and across brain regions by applying it to in-vivo recording of up to 12,000 neurons in mouse auditory cortex, posterior parietal cortex and hippocampus.

Keywords: Ca2+ imaging, volumetric, high-speed, 2-photon, 3-photon, microscopy, light sculpting, systems neuroscience, cortical network, circuit dynamics

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb:

A new volumetric calcium imaging method called Hybrid Multiplexed Sculpted Light Microscopy (HyMS) opens up the window to record neuronal activity of more than ten thousand neurons over the entire cortical depth and within the hippocampus of awake and behaving mice.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in optical microscopy have facilitated major discoveries in neuroscience, (Kato et al., 2015; Makino et al., 2017; Mao et al., 2011), by enabling functional recording at higher speed, spatial resolution, across depth and of ever-larger populations. Two-photon (2p) scanning microscopy (Denk et al., 1990; So et al., 2000) together with genetically encoded calcium (Ca2+) probes (Chen et al., 2013; Miyawaki et al., 1997; Nakai et al., 2001), has emerged as the standard modality for in vivo neuroactivity recording in the scattering brain. However, fundamental limits and tradeoffs between resolution, speed and size of the acquisition volume prevent scalability of the sequential point-by-point scanning approach of a diffraction-limited (DL) spot as used in conventional 2p microscopy. Despite recent advances (Helmchen and Denk, 2005; Ji et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Nöbauer et al., 2017; Prevedel et al., 2016; Reddy et al., 2008; Shain et al., 2017; Weisenburger and Vaziri, 2018; Yang and Yuste, 2017), it remains challenging to record activity of large populations at depth in scattering tissue at single-cell resolution and physiological timescales.

To address this issue here, we have developed a modular platform named Hybrid Multiplexed Sculpted Light (HyMS) microscopy featuring a systems-wide design paradigm and hybrid 2p-three-photon (3p) excitation. We have combined key innovations including spatiotemporal multiplexing, one-pulse-pervoxel excitation and synchronized detection, rapid remote scanning, and light sculpting using temporal focusing, in an integrated design approach to microscopy, where we demand from the imaging system high-quality single-neuron source extraction from a target volume and optimize all system parameters to meet these quantified standards at the maximum acquisition rate.

We demonstrate the performance of HyMS microscopy and its configurations in the mouse posterior parietal cortex (PPC), primary auditory cortex (pAUD) and hippocampus (HPC). Our target FOVs span axially over cortical layers 1–6, encompassing basal dendritic and pyramidal layers of the HPC CA1 region, within the HPC from CA1 to the dentate gyrus (DG), and cover laterally up to 1mm2. We show Ca2+ imaging of up to 1×1×0.6mm volumes at >5Hz, 340×340×250μm located at ~1mm depth, ~0.7×0.7×1mm spanning an entire cortical column and the major portion of the HPC; and we push the attainable depth for high-speed 3p imaging to >1.2mm. Our method has enabled near-simultaneous in vivo recording from populations of up to 12,000 neurons across different regions and depths of the mouse brain and opens up new possibilities to study how distributed network dynamics of large neuron populations encode sensory inputs and generate behavior.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Systems design and hardware modules

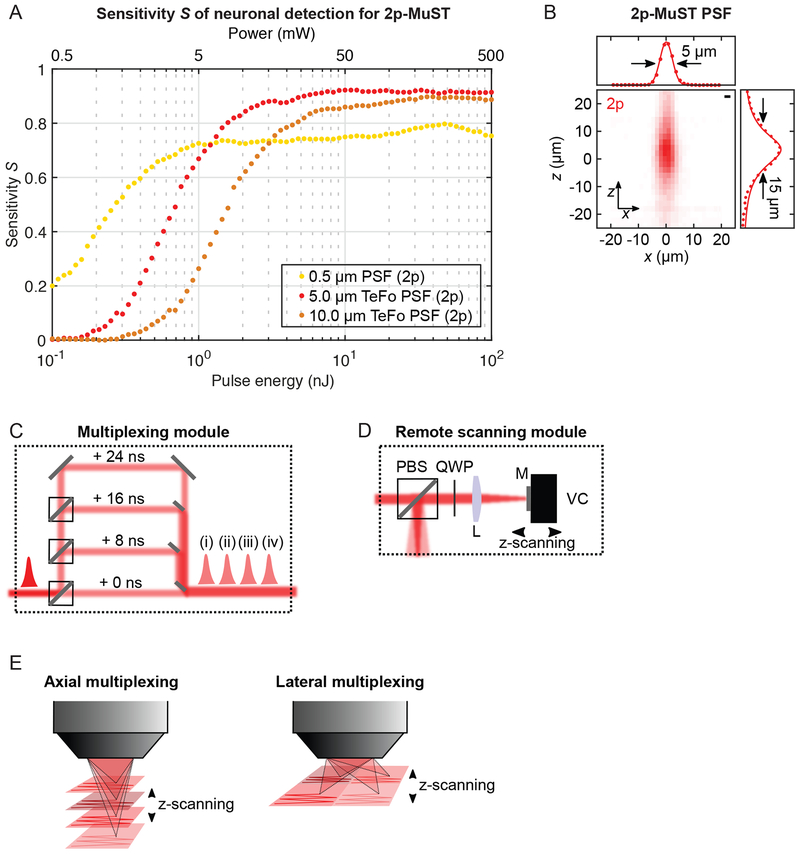

The aim of our microscope design was to faithfully extract neuroactivity of single somata, ~10–15μm (Kandel et al., 2000), from target volumes spanning >1mm axially and 1mm laterally in the mouse brain at a rate set by the timescale of Ca2+ transients while keeping the laser exposure to established safe limits. We experimentally explored how parameters such as pulse energy and spot size affect the ability of the microscope to extract neuronal signals. Informed by the results, we built a model accounting for the various system parameters such as collection efficiency, spot size and shape, or Ca2+ probe characteristics. We used the sensitivity, S, the true-positive rate of identifying neuron signals against a ground truth, as figure of merit in our signal extraction as it allows for direct microscope optimization based on a key performance factor that is of ultimate biological relevance. We found high (S>0.9) sensitivity can be achieved for 2p using a 5μm spot at tolerable pulse energy while maintaining high fidelity in signal detection (Fig. 1A). In contrast, a DL point spread function (PSF) under the same conditions only reaches S~0.75 due to under-sampling (Fig. 1A). We characterized the false-positive rate using the precision P, defined as 1–false-positive rate, and found P reached comparably high values of ~0.85–0.9 for all strategies (Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1: 2p-MuST microscope with remote scanning.

(A) Sensitivity S to evaluate power penalty in the microscope design for 2p excitation. Analysis for one-pulse-per-voxel acquisition, with DL (0.5μm, light orange), 5μm TeFo (red), and 10μm TeFo (orange) PSFs with 5μm sampling. Power values assume 5MHz repetition rate. (B) Experimental TeFo-PSF using a 0.5μm fluorescent bead. Scalebar: 2μm. (C) Multiplexing module creating four beamlets using PBS (polarizing beam splitters) and HWP (half wave plates), each delayed by 8ns respectively. (D) Remote scanning module with PBS (polarizing beam splitter), QWP (quarter wave plate) and mirror (M) mounted on a voice coil actuator (VC) modulating beam divergence for z-scanning. (E) Arrangement of TeFo-PSFs for the 4× axial and lateral multiplexing configuration of the 2p-MuST microscope.

The lateral and axial coupling of the localization of excitation in a Gaussian beam prevent the generation of a 5μm spot with comparable axial confinement. We used light sculpting based on temporal focusing (TeFo, Fig. S1B) for PSF engineering (Oron et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2005) which has been used in various imaging and optogenetic schemes (Andrasfalvy et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2012; Dana and Shoham, 2012; Dana et al., 2013; 2014; Hernandez et al., 2016; Prevedel et al., 2016; Schrödel et al., 2013). Increasing the PSF width requires higher pulse energies to maintain signal (Fig. 1A), however, this is not the case for the axial extent of the PSF as the fluorescence is proportional to the photon flux squared through the excitation area, not the excitation volume. Thus, while from a purely sampling perspective an isotropic PSF would be desirable, maximization of S and volume rate demands lengthening the axial width to the cell size, beyond which decrease in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and increased crosstalk reduce S (Fig. 1A). We used these results as target parameters for our sculpted PSF (Fig. 1B). We confirmed by in vivo characterizations that our desired PSF dimensions, in particular its axial size, are maintained in the scattering mouse brain (Fig. S1C–G); in keeping with reports that TeFo may be inherently resilient to tissue scattering (Dana and Shoham, 2011; Escobet-Montalbán et al., 2018; Papagiakoumou et al., 2010). We have previously shown that for a given average power the one-pulse-per-voxel excitation scheme yields a higher fluorescent signal and SNR compared to when the fluorescence signal over multiple pulses is averaged (Prevedel et al., 2016). Thus, we developed a custom laser system providing the highest possible repetition rate at sufficient pulse energies to facilitate such an excitation scheme with our enlarged PSF. To record from our target volume at the required rate, we combined our TeFo PSF with spatiotemporal multiplexing (Amir et al., 2007; Bewersdorf et al., 1998; Cheng et al., 2011; Stirman et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016) and built a Multiplexed Scanned TeFo (MuST) microscope (Fig. 1C). An 8ns delay between beamlets allowed us to de-multiplex the signals with negligible crosstalk (Fig. S1H–J).

To maximize axial scan speed, we combined TeFo with remote scanning (Botcherby et al., 2012) by inserting an axially movable mirror into a plane conjugated to both the grating and sample plane (Fig. 1D). Moving the mirror translates into a shift of the axial position of the TeFo spots. Using a light-weight mirror on a voice coil actuator (Botcherby et al., 2012; Sofroniew et al., 2016), we realized rapid z-scanning up to ~17Hz. We configured our MuST microscope for 4× axial or lateral multiplexing using different mirror holder chucks on the voice coil (Fig. 1E). In the following, we demonstrate the potential of these configurations for applications in different biological contexts and brain regions.

Volumetric high-speed imaging of mouse PPC

We performed 2p Ca2+ imaging in PPC layers 1–5 of awake head-fixed mice expressing GCaMP6f. We chose the PPC region (Fig. 2A) due to its accessibility and function as multisensory integrator (Harvey et al., 2012) which results typically in high levels of spontaneous activity (Mohan et al., 2018).

Fig. 2: High-speed volumetric 4×-axial 2p-MuST imaging of mouse PPC.

(A) Mouse brain region under test (PPC). (B) Configuration for 4×-axial 2p-MuST imaging. (C) Mirror holder chuck for 4× axial multiplexing. Scalebar: 5mm. (D) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 30min volumetric 4×-axial 2p-MuST recording in mouse PPC, 690×675×600μm FOV, 16.7Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6f. Scalebar: 100μm. See also Video S2. (E) Ca2+ traces of all 5,782 active neurons and zoom-in for 200 example neurons. (F) Treadmill velocity and behavioral state for subsequent analysis (locomotion: red). See also Video S1. (G) MIP of a 6min single-plane functional ground truth (2p DL) and simultaneous 2p-MuST recording at 390μm imaging depth, 165×165μm FOV, 10Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6f. See also Video S3. Right: Locations of the hand-annotated ground truth (black) and identified spatial components of the 2p-MuST recording (red). Scalebars: 20μm. (H) Ca2+ traces of all 14 active neurons from the 2p-MuST recording (red), matched to ground truth traces (black). (I) Experimental S and P scores of 2p-MuST (red) and DL recordings (blue) at varying imaging depths compared to human-annotated ground truth. Solid lines: mean; shaded area: SD (n=8 recordings).

In the 4× axial MuST configuration, we recorded over a 600μm axial range with each of the four beamlets covering a 150μm sub-volume (Fig. 2B). To do so, we designed a mirror holder chuck for the actuator that allowed positioning of the four mirrors at different z-positions resulting in ~150μm separation of the beamlets in the sample (Fig. 2C). Using this configuration, we could record within a 690×675×600μm volume at 16.7Hz (Fig. 2D and Video S1, S2) using only 36mW distributed across the four excitation spots, consistent with our model within safe power limits (Podgorski and Ranganathan, 2016; Prevedel et al., 2016). We typically found ~3,000–6,000 active neurons in our imaging volume (Fig. 2E) depending on the recording duration (~10–30min) and the animal’s behavioral state (Fig. 2F).

Our data processing pipeline (Fig. S2A) incorporated motion correction based on NoRMCorre (Pnevmatikakis and Giovannucci, 2017) and volumetric source extraction using constrained non-negative matrix factorization (CNMF) (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016), which allowed for signal extraction of partially overlapping neurons. The overall characteristics of our recordings such as Ca2+ transient decay times or relative change of fluorescence (Fig. S2B), and noise levels of the baseline (Fig. S2C) were consistent with previous demonstrations of functional 2p imaging in mouse cortex (Nadella et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016).

To experimentally validate our method, we integrated a DL 2p path to our setup to simultaneously record the same population activity with a DL and TeFo PSF (Fig. 2G, Video S3). We recorded at different imaging depths and quantitatively compared the fidelity of the neuronal signals from both acquisition modalities to an annotated functional ground truth (Fig. 2G–H). Detectable activities in the DL data, including traces with sparse activity and weak transients (ΔF/F0~0.2), can be reliably detected by our method (Fig. S2D). For all depths, our TeFo recordings reached reached S ~0.74±0.05 (mean±STD) with P~0.74±0.10 (mean±STD) (Fig. 2I). Comparably, the DL datasets reached S~0.94±0.05 (mean±STD) and P~0.67±0.14 (mean±STD) (Fig. 2I). At 25× higher sampling density, the DL resolution allowed for a moderately increased S, while P was reduced compared to TeFo. However, the slightly higher S of the DL method comes at a 100× lower volume rate and thus is unsuitable for volumetric Ca2+ imaging. Our TeFo scores for S and P are comparable to the reported performance of CNMF on DL datasets (Giovannucci et al., 2019). These results demonstrate that MuST does not impair the fidelity of neuron identification and signal extraction, and indeed performs at single neuron resolution comparably to standard DL techniques while enabling fast volumetric Ca2+ imaging.

To further gauge the performance of MuST, we plotted the nearest neighbor distances of the neurons (Fig. S2E) and found a histogram peak at ~20μm, agreeing with the expected neuron density in PPC (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2013); the lack of values near 0μm demonstrates that CNMF successfully merges neighboring sources resulting in a low probability that the same neuron is picked up twice. Our demonstrated volume rate of 16.7Hz for a ~0.3mm3 volume inside scattering brain tissue outperforms previously demonstrated, unbiased imaging systems (Bouchard et al., 2015; Duocastella et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2018; Song et al., 2017) including one from our laboratory (Prevedel et al., 2016) by >7×.

High-speed imaging of a 0.6mm3 volume in mouse pAUD

To demonstrate the broader application of MuST, we configured it for 4× lateral multiplexing (Fig. 3A) using another mirror holder chuck on the voice coil so that each beamlet covered a quarter of the 1mm2 target FOV (Fig. 1E). We then performed Ca2+ imaging across layers 1–5 of pAUD (Fig. 3B) in double-transgenic animals expressing GCaMP6s (Daigle et al., 2018).

Fig. 3: High-speed volumetric 4×-lateral 2p-MuST imaging of mouse pAUD.

(A) Configuration for 4×-lateral 2p-MuST imaging. (B) Mouse brain region under test (pAUD). (C) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 20min volumetric 4×-lateral 2p-MuST recording in mouse pAUD, 1×1×0.6mm FOV, 5.1Hz, double-transgenic GCaMP6s. Scalebar: 100μm. See also Fig. S3, Video S4. (D) Pure tone (amplitude modulated) stimulus. (E) Examples of trial-averaged single-neuron post-stimulus responses to the pure tone stimuli. Dotted squares: best frequency response. Shaded area: SD (n=25–30 trials). (F) Frequency tuning curves for each neuron with high correlation to a pure tone stimulus. (G) Locations of the 2,743 neurons (out of 7,186 active) with high correlation to the pure tone stimulus. (H) Axial z-projection for the cortical layers 2/3a, and 3b/4. Black arrow: gradient of increasing best frequency. Anatomical coordinate system: L: lateral; R: rostral. Scalebar: 200μm. (I) Projection of a vertical slice along the black arrow and through the shaded area in panel H. Scalebar: 200μm. (J) Difference in best frequency as a function of axial position in panel I, and linear regression (red). F-statistics vs. constant model: p=0.167. Error bars: SD (n=1,014 neurons). (K) Best frequency as a function of position along the black arrow in panel H, and linear regression (red). F-statistics vs. constant model: ***p=1.27×10−5. Error bars: SD (n=1,014 neurons).

The functional role of the auditory cortex and its sub-areas like pAUD is an area of active research (Blackwell and Geffen, 2017; Kuchibhotla and Bathellier, 2018). A dominant motif is a global organization of responses to certain frequency tones such that nearby neurons respond to similar frequencies, known as tonotopy (Stiebler et al., 1997). Conversely, simultaneously imaged neurons are strongly heterogeneously responding while exhibiting high noise correlations in the presence of audio stimuli, suggesting they form large, interconnected networks (Vasquez-Lopez et al., 2017). Thus, a method capable to record from a significant part of the auditory cortex and across its layers with single-cell resolution seems ideally suited to study how the coarse-scale tonotopy emerges from heterogeneous activity at the single-neuron level, and more generally, how auditory information is represented in the organization of the auditory cortex.

While answering these questions is beyond the scope of this work, motivated by the potential of MuST we performed exploratory recordings in pAUD. Fig. 3C shows a 3D maximum intensity projection (MIP) render of a 4× lateral MuST recording (Video S4). We recorded a 1×1×0.6mm volume at 5.1Hz and identified 11,907 active neurons in a 20min recording (Fig. S3A) where we presented the animal with frequency sweeps across its hearing range (Fig. S3B). We then presented 12 amplitude-modulated pure-tone stimuli from 6–81kHz at octave-based separations (Fig. 3D). We found 2,743 neurons with a high correlation to specific stimuli frequencies and observed the same neurons often respond to adjacent frequencies with different strength, resulting in a tuning curve for each neuron (Fig. 3E–F).

Next, we analyzed the locations of neurons with high stimulus correlation (Fig. 3G). We found them to be strongly heterogeneous and distributed across different pAUD layers, but we also observed regions with tuning to a specific frequency range. To further investigate the layer organization, we computed z-projections for cortical layers 2/3a and 3b/4 (Fig. 3H) and observed a macroscopic organization with an increasing best frequency response towards a patch of high frequency (~32–81kHz) responding neurons. Using a vertical projection we observed a similar organization across layers (Fig. 3I–J). To quantify the lateral frequency response gradient, we computed the best frequency along the black arrow in Fig. 3H and found neighboring neurons to have a more similar frequency response compared to neurons that are further apart (Fig. 3K). Our results, while allowing for the first time to visualize the simultaneously collected 3D response profiles of the auditory cortex, are consistent with previous studies using electrophysiology or Ca2+ imaging of small single-plane FOVs (Guo et al., 2012; Vasquez-Lopez et al., 2017).

The application of MuST to pAUD demonstrates how the ability to capture the dynamics of thousands of neurons within a volume of 0.6mm3 can be used to study the functional organization, and in particular the columnar structure, of large circuits.

Volumetric and high-speed 3p imaging of mouse PPC layer 6b and hippocampus CA1 through intact cortex

The obtainable imaging depth by 2p excitation is ultimately set by out-of-focus fluorescence: In the mouse brain, the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) reaches unity at ~800μm depth (Tao et al., 2017). The higher nonlinearity in 3p excitation eliminates most out-of-focus fluorescence while excitation photons are less scattered due to the red-shifted wavelength, enabling imaging of deeper structures (Horton et al., 2013; Ouzounov et al., 2017). The peak of the 3p cross-section for GCaMP excitation is at ~1,300nm, a spectral window where reduced water absorption and scattering lead to minimal attenuation in the tissue (Horton et al., 2013). To access depths beyond ~800μm, we designed our OPCPA with a second output channel at 1,300nm, pumped by the same laser as used for 2p-MuST.

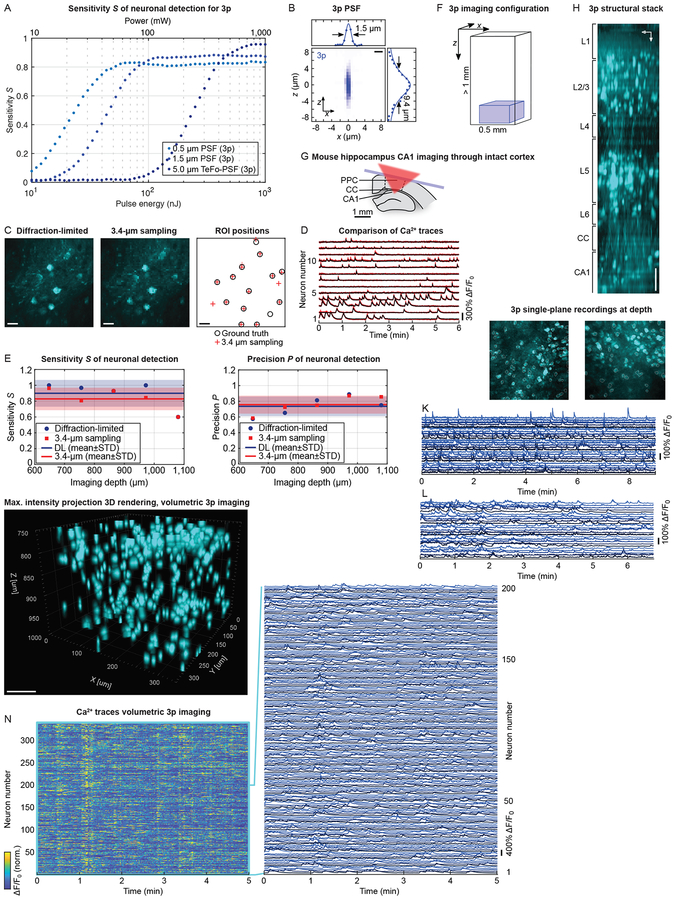

We applied the above sensitivity and precision framework to 3p Ca2+ imaging and found that a 5μm spot, which was optimal for 2p, would require excitation powers beyond the brain heating limit (Fig. 4A). Reducing the lateral size of the 3p PSF to 1.5μm at 3.4μm sampling, however, results in high S>0.9 while enabling us to access a large FOV of ~340×340μm using <80nJ at 1mm depth (Fig. 4A). Similar to 2p, a 3p DL PSF, under otherwise the same conditions, reaches only S~0.8 due to the sparse sampling (Fig. 4A). P reaches high values of ~0.85–0.9 for all 3p strategies (Fig. S4A). To ensure staying within the power budget for all configurations, we chose a repetition rate of ~1MHz for the 1,300nm OPCPA channel.

Fig. 4: High-speed and volumetric 3p imaging at depth of mouse PPC and HPC through intact cortex.

(A) Sensitivity S (at median 3p imaging depth, 1mm) to evaluate power penalty in the microscope design for 3p. Analysis for one-pulse-per-voxel acquisition, and DL (0.5μm, turquoise), 1.5μm (blue), and 5μm TeFo-PSF (dark blue) with 3.4μm sampling. Power values assume 1MHz repetition rate. (B) Experimental 3p PSF using a 0.5μm fluorescent bead. Scalebar: 2μm. (C) MIP of a 6min single-plane functional ground truth (3p DL) and retrieved 3p recording with 3.4μm sampling in PPC at 800μm imaging depth, 170×170μm FOV, 78Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6f. Right: Locations of the hand-annotated ground truth (black) and of the spatial components for the 3p recording with 3.4μm sampling (red). Scalebars: 20μm. (D) Ca2+ traces of all 13 active neurons from the 3.4μm sampled 3p recording (red) matched to ground truth traces (black). (E) Experimental S and P scores of 3.4μm sampled 3p recordings (red) and DL 3p recordings (blue) at varying imaging depths compared to human-annotated ground truth. Solid lines: mean; shaded area: SD (n=5 recordings). (F) Configuration for high-speed and volumetric 3p imaging at depth. (G) HPC CA1 imaging through intact PPC and CC. (H) 3p structural stack showing neurons in PPC layers 1–6, CC and HPC CA1. Scalebar: 100μm. (I) MIP of a ~9min single-plane 3p recording in CA1 through intact cortex at 1.16mm depth, 340×340μm FOV, 78Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6s. Scalebar: 100μm. See also Video S5. (J) MIP of a ~7min single-plane 3p recording in CA1 through intact cortex at 1.22mm depth, 340×340μm FOV, 78Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6f. Scalebar: 100μm. (K) Example Ca2+ traces (out of 104 active) from the dataset in panel I. (L) Example Ca2+ traces (out of 72 active) from the dataset in panel J. (M) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 5min volumetric 3p recording in PPC layer 6b and HPC CA1 through intact cortex at 750–1,000μm depth, 340×340×250μm FOV, 3.9Hz, cytosolic GCaMP6f. Scalebar: 100μm. See also Video S6. (N) Ca2+ traces of all 346 active neurons and zoom-in for the dataset shown in panel M.

Following the same argument as for 2p, an increased axial extent of the 3p PSF up to the cell size (10–15μm) allows for optimal S and volume rates. Thus, we designed and constructed a separate path of our microscope for 3p excitation and reduced the effective excitation NA of the microscope objective by underfilling generating a ~1.5μm lateral and ~9.4μm axial PSF (Fig. 4B). To experimentally validate our sparsely-sampled 3p modality, we recorded single planes at varying imaging depths and compared the fidelity of the extracted signals to an annotated ground truth (Fig. 4C–D). Across depths, S reached 0.85±0.10 (mean±STD) while P~0.76±0.12 (mean±STD) (Fig. 4E). A densely-sampled 3p recording reached similar scores with Ŝ0.90±0.17 (mean±STD) and P~0.74±0.13 (mean±STD) (Fig. 4E). Thus, the reduced spatial sampling of our 3p imaging does not impair its fidelity of neuronal signal extraction, performing comparably to standard DL 3p, but at higher acquisition rates. Moreover, we again utilized the single-pulse-per-voxel acquisition scheme, which for 3p led to an even greater, n2-times improvement of the signal for a given power compared to n-pulse-averaging.

Using our optimized configuration, allowed us to perform high-speed single-plane and volumetric 3p imaging at depths up to 1.22mm below the brain surface (Fig. 4F). To record activity of neurons in HPC CA1, it was necessary to image through the intact cortex and fibrous structure of the corpus callosum (CC, Fig. 4G). A structural stack using 3p from the brain surface to 1.2mm depth (Fig. 4H) shows labeled neurons across all layers with neuron densities in agreement with the known cortical layer structure (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2018; Herculano-Houzel et al., 2013). Recording from layer 6 neurons at ~700–850μm required only a moderate power of ~50mW, while passing through the scattering CC came at an additional requirement of 50–100mW consistent with previous reports on the shorter scattering length (~150μm) of white matter compared to neocortex (~300μm) (Wang et al., 2018).

We acquired single-plane (340×340μm FOV) 3p recordings of HPC CA1 neurons in mice expressing GCaMP6s (Fig. 4I, Video S5) and GCaMP6f (Fig. 4J) from depths up to 1.22mm through intact cortex. We typically imaged ~100–150 neurons per single plane while our acquisition strategy (Fig. S4B–G) allowed us to extract Ca2+ traces at 78Hz representing an order-of-magnitude improvement over previous results, albeit ~200μm deeper (Ouzounov et al., 2017). The required average power of ~190mW to image the deepest layers at 1.22mm was the highest power used in any configuration presented here, well within the reported safe limits of heat-induced photo damage (Podgorski and Ranganathan, 2016; Prevedel et al., 2016). Applying our data processing pipeline allowed us to obtain high-quality Ca2+ traces for both GCaMP6s/f labeling (Fig. 4K–L).

We observed our deep 3p recordings to exhibit more motion (Fig. S4H–I), up to ~20μm, compared to ~5–10μm in more superficial depths acquired with 2p-MuST (Fig. S4J), likely due to a longer lever arm between the recording plane and the head-mounting point. However, using our motion correction pipeline (Fig. S4H–J), motion events could be detected and compensated for such that artifacts in Ca2+ traces were effectivity suppressed.

Given that our planar framerate is well beyond the response time of GCaMP, we devoted the available surplus in speed to realization of volumetric 3p imaging. We recorded Ca2+ activity of layer 6b neurons in PPC and HPC CA1 within a ~340×340×250μm volume at 3.9Hz located between 750–1,000μm below the brain surface (Fig. 4M, Video S6). We identified a sub-population of neurons located in the lower part of cortical layer 6b (750–850μm from the brain surface) and another, deeper sub-population in HPC CA1. We were able to extract and demix the activity of typically 300–400 neurons within the above volume (Fig. 4N). To our knowledge these results represent the first demonstration of volumetric Ca2+ imaging at such tissue depths.

Hybrid Multiplexed Sculpted Light (HyMS) microscopy

To access the full potential of our method, we combined 2p-MuST and 3p into HyMS microscopy (Fig. S5A). Expanding on the multiplexing approach above, we integrated the 3p beam as a fifth beamlet delayed by ~8ns with respect to the 2p beamlets. Our custom laser system with both OPCPA channels pumped by the same laser ensures relative pulse delays are maintained, allowing us to use a single PMT and data acquisition pipeline to detect the fluorescence from all five (four 2p-MuST and one 3p) excitation spots (Fig. S5B).

For high versatility of our microscope, we designed an adjustable mirror holder chuck to freely select the axial positions of the four 2p-MuST sub-volumes with respect to each other and the 3p volume which was kept at the native focal plane. This allowed us to adjust the size and geometry of the target volumes to brain regions of interest. In the following, we discuss multiple configurations of our HyMS microscope and their applications to different regions in the mouse brain.

Volumetric imaging of an entire cortical column in mouse PPC

We first configured our HyMS microscope such that the combined axial range covered layers 1–6, i.e. the entire depth, of the mouse neocortex (Fig. 5A). We achieved functional recording of a ~690×675×1,000μm volume containing several thousand (4,121) active neurons at 13.0Hz (4.3Hz for the 3p sub-volume) in PPC (Fig. 5B–C). To our knowledge this represents the first volumetric recording of an entire cortical column, often regarded as the computational unit of neocortex (Mountcastle, 1997), at single-cell resolution and such volume rates. During typical sessions of 10–20min, animals exhibited frequent locomotion periods on our treadmill (Fig. 5D) and correspondingly elevated activity in PPC (Fig. 5E). The distribution of active neurons across cortical layers (Fig. 5F) was consistent with the anatomy and neuron density in these layers (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2018).

Fig. 5: Volumetric HyMS microscopy of an entire cortical column in mouse PPC.

(A) HyMS microscope configuration. Red: 2p, blue: 3p excitation volume. (B) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 10min HyMS recording in PPC, 665×730×1,000μm FOV, 13.0Hz (4.3Hz: 3p sub-volume), cytosolic GCaMP6f (green: 2p, cyan: 3p). Scalebar: 100μm. (C) Ca2+ traces of all 4,121 (2p: 3,995 (green); 3p: 126 (blue)) active neurons and zoom-in of example traces. White rectangles: traces in panel E. (D) Treadmill velocity and assigned behavioral state for subsequent analysis (locomotion: red). (E) Zoom-in of activity traces marked in panel C during a locomotion episode showing activity onset. (F) Histogram of active neurons as a function of imaging depth. (G) Spearman correlation coefficient (R) matrix from all traces in panel C, grouped by layer 1–6 and agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Left side: Pearson’s correlation coefficient of each Ca2+ trace with the treadmill velocity in panel D. Black and white triangles: clusters discussed in the main text. (H) Number of PCs explaining 95% of the variance of the dataset in panel C for the behavioral states ‘during locomotion’ (blue) and ‘stationary periods’ (red). Error bars: SD (n=300 permutations).

Our volumetric imaging capability allowed us to study correlations of network activity distributed across all layers. We computed the correlation matrix of all Ca2+ traces and grouped them by cortical layer and agglomerative hierarchical clustering within (Fig. 5G). We identified small and large clusters of spontaneous activity in each layer consisting of ~10–100 neurons, some showed correlated activity with a similarly-sized group in other layers. We also calculated the correlation of each trace with the treadmill velocity and found clusters of correlated activity in different layers showing high correlation (white triangles) or anti-correlation (black triangles) with the treadmill velocity. These clusters across cortical layers suggest the engagement of inhibitory and excitatory circuits associated with locomotion.

Alternatively, it is also possible to investigate brain state dynamics, i.e. the temporal evolution of the overall state of the network (Cunningham and Yu, 2014). With the ability to record from thousands of neurons, it is insightful to evaluate the amount of information gained by capturing population-level activity. To quantify how the dimensionality of latent population dynamics scales with the number of neurons recorded, we used principal component analysis (PCA) on a varying number of randomly-sampled neurons and computed the percent variance in the data captured by a given number of principal components (PCs), (Fig. 5H). We performed this analysis for two behavioral states ‘during locomotion’ and ‘stationary periods’ as shown in Fig. 5D. For each state, we found the number of PCs required to capture 95% of the variance to initially increase with the number of neurons, but ultimately to saturate, suggesting that our approach has sufficiently resolved the relevant population dynamics in the FOV during the two behavioral states. In the case of locomotion, the reduced dimensionality needed to quantify 95% of the variance reaches about one-third that of stationary periods. This suggests the dimensionality of population dynamics in large volumes of cortex is reduced during a concerted behavior such as locomotion compared to that of spontaneous activity during stationary periods. We speculate that this may result from the recruitment of many neurons to process a relevant subset of locomotion-related tasks from a manifold of possible tasks reducing the dimensionality of sparse activity in the circuit.

The above example demonstrates the capability of HyMS for systematic studies of the relationship between large-scale network activity comprising of neurons distributed across depth and different behavioral paradigms.

Volumetric imaging across mouse hippocampus CA1 and DG

Next, we applied HyMS microscopy to simultaneous Ca2+ imaging of dorsal HPC CA1 and DG neuronal populations while animals ran on a treadmill. The dynamics and interaction of different populations in HPC are involved in spatial information processing (Buzsaki and Moser, 2013; O’Keefe and Dostrovsky, 1971), formation and consolidation of declarative and episodic memory (Eichenbaum, 2004; Squire et al., 1984), and contain a cognitive map (O’Keefe and Nadel, 1978). Its canonical circuit model is the trisynaptic circuitry that serially processes information from the DG input, to area CA3, and to the CA1 output (Ahmed and Mehta, 2009; Soltesz and Losonczy, 2018). These computations occur over multiple spatial scales involving several anatomical regions within the HPC but recording across regions in the dorsal HPC has remained challenging, especially due to its deep location between ~0.9–2.3mm below the brain surface.

Our HyMS microscope is capable of recoding volumetrically the activity of neurons over an axial range spanning the majority of the HPC complex and thereby to fill knowledge gaps in the dissection of the HPC ensemble dynamics. To access the dorsal HPC, we performed window implantation preceded by cortical aspiration (Dombeck et al., 2010; Zaremba et al., 2017) using a metal-sintered conical cannula with wall angles matching the objective lens collection angle (Fig. 6A). We then adjusted our HyMS microscope so that a 765×665×800μm volume could be recorded at ~4.3–13Hz, where depths ranging from ~640–800μm were recorded by 3p (Fig. 6B). The curved structure at ~150–200μm depth is the pyramidal cell layer of HPC CA1. Overall, we found ~1,500 active neurons spanning the volume from CA1 to DG (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6: Simultaneous volumetric HyMS microscopy of mouse HPC CA1 and DG.

(A) Mouse brain with implanted conical cannula on top of HPC and aspirated cortex. (B) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 15min HyMS recording in HPC, 665×730×800μm FOV, 13.0Hz (4.3Hz: 3p sub-volume), cytosolic GCaMP6f (green: 2p, cyan: 3p). Scalebar: 100μm. (C) Ca2+ traces of all 1,465 (2p: 1,415 (green); 3p: 50 (blue)) active neurons and zoom-in of example traces. White rectangles: traces in panel E. (D) Spearman correlation coefficient (R) matrix from all traces in panel C, grouped by HPC region and agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Left side: Pearson’s correlation coefficient of each Ca2+ trace with the treadmill velocity in panel D. Black triangles: clusters discussed in the main text. (E) Ca2+ traces in panel C sorted by lag time for a locomotion episode. Numbers: cell populations discussed in the main text. (F) Lag time histogram for all Ca2+ traces in panel C. (G) Histogram of active neurons for the cell populations in panel E as a function of imaging depth.

We investigated the correlated activity between CA1 and DG neurons (Fig. 6D) and observed small and large clusters of activity in both CA1 and DG consisting of ~10–100 neurons. Some clusters showed correlated activity with clusters in the other HPC region (Fig. 6D), suggesting they are part of the same functional assembly. We examined the correlation of the Ca2+ traces with the treadmill velocity (Fig. 6D) and found groups of correlated activity in CA1 and DG with neurons showing high correlation or anti-correlation with the treadmill velocity (black triangles).

Next, we examined the neuroactivity during a locomotion episode. We sorted all traces by their lag time using the cross-correlation with the treadmill velocity (Fig. 6E). The lag time histogram shows a symmetric distribution around 0s delay (Fig. 6F). We found three distinct populations of neuroactivity (Fig. 6E): Population 1 showed sequential ordering of activity during the pre-locomotion period; 2 was highly active during locomotion while the activity of the other cells appeared inhibited; and 3 showed sequential activity during the post-locomotion episode. The activity observed in populations 1 and 3 is consistent with sparse activity of pyramidal cells while the robust, short-latency positive modulation of activity during locomotion of population 2 is more typical for interneurons (Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008). A histogram of the depths for the identified populations 1, 3 as well as 2 shows a peak at 150–200μm indicating the pyramidal layer (Fig. 6G). These results demonstrate that HyMS microscopy can be used to study the dynamics of the circuit activity simultaneously across multiple sub-regions of the HPC, giving access to unprecedented data on how the HPC formation process information.

Simultaneous volumetric Ca2+ imaging of mouse PPC and underlying hippocampus CA1

In biological experiments that require access to subcortical regions and thus cortical aspiration, care must be attained to avoid damaging overlying structures that may have critical inputs or fibers of passage to the target volume. Moreover, it may be of interest to study the neuronal dynamics of subcortical regions with that of the overlying cortical regions in a correlated manner. The versatility of HyMS microscopy allowed us to address both issues by demonstrating simultaneous volumetric recording of neuroactivity from the PPC and underlying HPC CA1 region. To demonstrate this capability, we chose the sub-volumes such that 2p-MuST accessed neurons located within 100–700μm axial range while we simultaneously recorded neurons located at 950–1,100μm depth with volumetric 3p (Fig. 7A). Thereby, we could record from ~3,500 active neurons within the PPC column and HPC CA1 neurons located directly underneath at 4.6–13.8Hz (Fig. 7B–C, Video S7) while animals exhibited frequent locomotion periods during typical sessions of 10–20min (Fig. 7D–E).

Fig. 7: Simultaneous volumetric imaging of mouse PPC layers 1–5 and HPC CA1 using HyMS microscopy.

(A) HyMS microscope configuration. Red: 2p, blue: 3p excitation volume. (B) 3D rendering (MIP) of a 10min HyMS recording in PPC and underlying HPC CA1, 720×665×1,100μm total volume (recorded from 100–700μm and 950–1,100μm depth), 13.8Hz (4.6Hz: 3p sub-volume), cytosolic GCaMP6f (green: 2p, cyan: 3p). Scalebar: 100μm. See also Video S7. (C) Ca2+ traces of all 2,395 (2p: 2,268 (green); 3p: 127 (blue)) active neurons and zoom-in of example traces. White rectangles: traces in panel E. (D) Treadmill velocity of the recording in panel C and behavioral state for subsequent analysis (locomotion: red). (E) Zoom-in of the activity traces marked in panel C during a locomotion episode showing activity onset. (F) Spearman correlation coefficient (R) matrix from all traces in panel C, grouped by brain region (PPC layer and HPC CA1) and agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Left side: Pearson’s correlation coefficient of each Ca2+ trace with the treadmill velocity in panel D. Black and white polygons: clusters discussed in the main text. (G) I(X1;X2,…,Xn) for the timeseries in panel C (blue) and ‘Shuffled’ (red), and the behavioral states ‘during locomotion’ and ‘stationary periods’. Shaded area: SD (n=300 permutations). P-value: Wilcoxon rank-sum test (between Experiment and Shuffled).

We studied correlations between different cortical layers in PPC and HPC CA1 as a function of animal behavior and identified clusters of spontaneous activity in cortical layers 1–5 and HPC CA1 (Fig. 7F). We observed more correlated activity across cortical layers and within the HPC than between both regions with few exceptions (white rectangles), in keeping with the higher density of connectivity within cortex and HPC, respectively. We examined the correlation of the activity with the treadmill velocity (Fig. 7F) and found clusters of correlated activity in cortex and HPC CA1 showing high correlation and anti-correlation with the treadmill velocity (black triangles). Furthermore, cortical neurons in clusters of inter-region correlation with HPC show negative correlation with the treadmill velocity. These functional results are consistent with the low number of direct projections from CA1 to the overlying PPC (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2018).

Next, we studied the degree of information contained in our recordings of thousands of neurons using an information theoretic approach. The mutual information I between variables quantifies the reduction in uncertainty about one variable given knowledge of another (Shannon and Weaver, 1949). For two random variables X and Y, we can be explicitly formulate I(X;Y) = H(X) – H(X|Y) as the reduction in entropy due to conditioning on one of the variables, where H(~) and H(~|~) represent entropy and conditional entropy. Compared to correlations and PCA, which capture only linear relationships among neurons, I also reflects nonlinear dynamics and higher-order correlations (Cover and Thomas, 2001). We computed I between a randomly-selected neuron and a varying number of randomly-sampled other neurons from both PPC and HPC CA1 to quantify the amount of information a single neuron gives about the population, and vice versa (Fig. 7G). We did this for the two behavioral states identified in Fig. 7D. Compared to stationary periods, locomotion increases I across the population, i.e. a lowered dimensionality of the population activity during locomotion, consistent with our observation of high mutual correlation clusters (Fig. 7F). Additionally, during locomotion, I steadily increases as more neurons are sampled (Fig. 7G), but not after removing any temporal alignment by shuffling, suggesting that temporal features associated with this active state are encoded in a distributed network. These behaviorally-relevant features could be encoding for intention and motor planning or for sensorimotor integration related to the tactile exploration of the treadmill.

Since the discovery of memory localization (Scoville and Milner, 1957), investigating the interactions between the HPC and cortical regions has been a mainstay in the neurobiology of learning and memory. Though formation and long-term maintenance of memories are believed to depend on the interplay between multiple brain regions (Sparks et al., 2011; Squire et al., 1984; Wilson and McNaughton, 1994), assessing network activity simultaneously between regions at the cell level has not been accomplished. HyMS microscopy opens up a way for multi-regional investigations into behavioral state-dependent modulation of cortico-HPC communication and information transfer.

Conclusions and outlook

Here, we have introduced HyMS microscopy and demonstrated large-scale volumetric in vivo Ca2+ imaging across all cortical layers of the mouse neocortex and within the HPC. Using an integrated, conceptual framework, we derived the parameters of our microscope design by optimizing the fidelity of extracting neuronal signals. We applied it to 2p and 3p volumetric imaging individually and in combination and demonstrated high-speed (~17Hz) acquisition rates within large volumes (up to 1×1×0.6mm), across an axial range of 1mm and beyond 1.2mm depth, allowing us to record the activity of up to 12,000 neurons. The obtainable imaging depths of our 3p and hybrid imaging approach are limited by the safe power levels before heat-induced damage occurs, although imaging at greater depths is possible—up to the limit posed by out-of-focus fluorescence (~800μm for 2p and ~2.5mm for 3p)—at a reduced acquisition rate or volume size. While our method was based on a costly, customized amplified fiber laser system, we expect that current developments in fiber laser technology will further boost widespread commercial distribution of such systems at lower costs in the foreseeable future. The capabilities of HyMS microscopy together with ongoing progress in optogenetics (Boyden et al., 2005; Emiliani et al., 2015; Vaziri and Emiliani, 2012; Zhang et al., 2007) provide an opportunity to gain new insights into the computational principles of information processing in the mammalian brain and to allow experimental testing of a wide range of theoretical models of cortical computations (Buonomano and Maass, 2009; McClelland and Goddard, 1998; Sompolinsky, 2014).

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Alipasha Vaziri (vaziri@rockefeller.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animal subjects

All surgical and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Rockefeller University. Male and female adult C57BL/6J, SST-IRES-Cre and Ai9 were supplied by Jackson Laboratory, and VGlut-IRES-Cre × Ai162 crossed mice were bred in house. All mice were 7–10 weeks of age at the time of the first procedure. Mice were allowed food and water ad libitum.

Virus injection

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5% - 2.0% maintenance at a flow rate of 0.7–0.9 l/min) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd.). A ~1cm incision was made over the midline of the scalp and the underlying periosteum was cleared from the skull. A grid of four 0.5mm diameter burr holes spaced 400μm apart was drilled in the center of the future window implant. A glass pipette was first back-filled with mineral oil and then front-filled with a genetically expressed Ca2+ indicator adeno-associated virus (AAV1-syn-GCaMP6f/s). The pipette was subsequently lowered to the injection site and virus was injected (32–64nl each, at 15–25nl/min; titer ~1×1012vgs/ml) into the brain parenchyma at 12–28 sites to achieve column-wide cortical (PPC: −2.5 AP, 1.8 ML, −1.2, −1.0, −0.8, −0.6, −0.4 DV or −2.2 AP, −1.75 ML, −1.3, −1.2, −1.1, −1.0, −0.6, −0.4, −0.2 DV) or hippocampal expression (−2.1 AP, 2.0 ML, −1.65 DV). Following injection, the scalp was sutured closed and the animal was allowed to recover 1–2 weeks before undergoing cranial window implantation.

Craniotomy and window implantation

As previously described, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic frame. The scalp was removed, and the underlying connective tissue was cleared from the skull. A custom-made stainless-steel head bar was fixed behind the occipital bone with cyanoacrylate glue (Loctite) or light-curable acrylic resin (Unifast, Henry Schein), and covered with black or pink dental cement (Ortho-Jet, Lang Dental). A circular craniotomy (3, 4, or 5mm diameter) was performed over the desired imaging site (PPC: centered at ~2.5mm caudal and ~1.8mm lateral; AUDp: centered at 2.7mm caudal and 5.35mm lateral, hippocampus: centered at ~2.0mm caudal and ~2.0mm lateral to bregma). A 3, 4, or 5mm circular glass coverslip (#1 thickness, Warner Instruments) was implanted in the craniotomy site and sealed in place with tissue adhesive (Vetbond). The exposed skull surrounding the cranial window was covered with a layer of cyanoacrylate glue and then dental cement. Hippocampal access using an implanted conical cannula was achieved by aspirating cortical tissue prior to implantation of a custom designed metal-sintered conical cannula. Post-operative care consisted of 3 days of subcutaneous delivery of dexamethasone (2mg/kg), antibiotic containing feed (LabDiet #58T7), and meloxicam (0.125mg/tablet) containing food supplements (Bio-Serv #MD275-M). After surgery, animals were returned to their home cages and were given at least one week for recovery and viral gene expression before being subjected to imaging experiments. Mice with damaged dura or unclear windows were euthanized and were not used for imaging experiments.

METHOD DETAILS

Obtaining sensitivity and precision of neuronal extraction under different acquisition conditions

In order to design our HyMS microscope with the optimal performance, we first developed an iterative process between experimental recordings under different acquisition conditions followed by evaluation and analysis of a number of performance metrics. This process allowed us to obtain an experimentally informed model through which different optical and imaging parameters (pulse energy, PSF, sampling) could be optimized. For each microscope configuration, we directly measured the fidelity of neuronal signal extraction by running the generated data stacks through a non-negative matrix factorization algorithm and evaluating the performance against the known ground truth. Performance was quantified using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) framework comprising “sensitivity S” (true-positive rate) and “precision P” (1–false-positive rate) (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2005). An ideal microscope should provide a high sensitivity without detrimental degradation of precision, for the largest possible volume and volume rate, within the bounds of the tissue heating limit.

To generate the above work flow, we conducted experiments recording from awake, head-fixed mice with cytosolic GCaMP6f labeling. Datasets corresponded to 2min recordings from a 300μm FOV in layer 2/3 (depth ~ 200μm) in mouse PPC recorded with high spatial and temporal resolution (0.6 NA, ~ 8μm axial localization, 0.6μm pixel size, 22.9Hz frame rate) using a large-FOV 2p microscope (Sofroniew et al., 2016). The recordings were motion-corrected using NoRMCorre, and neuronal footprints were extracted using the CaImAn software package (Giovannucci et al., 2019; Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016). The extraction algorithm was optimized by sweeping the spatial thresholds and comparing the extracted footprints to a visual inspection of the initial dataset. The detected footprints form the ground-truth basis for comparison for all subsequent configurations. The data stack was 2×2 pixel-binned to reduce shot noise, and background subtracted. Finally, the entire data stack was normalized to the average of the baseline values of the detected neurons (estimated by the median value of each neuron’s time series).

For each PSF shape, we calculated the expected signal and background counts as a function of the system parameters (collection efficiency, PMT gain, digitizer dynamic range, etc.), the geometry of the laser beam (pulse width, lateral spot size, axial extent, etc.), and the characteristics of the fluorophore (multi-photon interaction cross-section, intracellular concentration, etc.) (Tsai and Kleinfeld, 2010). The denoised data stack was renormalized to the expected signal, offset by the background, and convolved with the current lateral PSF of interest. Finally, shot-noise was added to each image in the stack using the ‘imnoise’ package (Matlab) with Poisson statistics. The resulting stack was spatially and temporally down-sampled to the desired resolution. The prepared stack was then fed into the CaImAn algorithm to extract neuronal footprints. These spatial footprints were compared to the ground-truth in order to compute S and P of signal extraction. For each configuration, we swept CaImAn’s spatial thresholds (as with the initial ground-truth) in order to maximize S and P scores. By evaluating S for each PSF, sampling, and power configuration, we could ensure that a given modality achieves the desired detection fidelity within a tissue-heating-limited power budget.

Laser source

We used a custom laser system consisting of an Yb-fiber chirped pulse amplifier (FCPA, Active Fiber Systems) and an optical parametric chirped pulse amplifier (OPCPA) (White Dwarf dual, Class 5 Photonics). The OPCPA had two output channels at 960nm and 1,300nm wavelength for 2p and 3p excitation, respectively. The 960nm channel produces >0.8μJ, <90fs pulses at a repetition rate of 4.7MHz. The 1,300nm channel produces >1.4μJ, <70fs pulses at a repetition rate of 1.0MHz. Both channels were dispersion-compensated using custom chirped mirror pairs (960nm channel, Class 5 Photonics) or a prism compressor (1,300nm channel, Newport) (Fig. S5A).

Spatiotemporal multiplexing module

The 2p beam was split into four beamlets using polarizing beam splitters (PBS) with half-wave plates (HWPs) for power adjustment of each beamlet (Fig. S5A). The beamlets were delayed by 8, 16 and 24ns using beam paths with relative length differences of ~2.5, ~5 and ~7.5m, respectively. Using two additional HWPs, the polarization was adjusted such that all four beamlets are TE polarized. The beam diameters of each beamlet were adjusted using individual telescopes, and the beams were then converged onto a plane that is conjugated to the temporal focusing grating.

Temporal focusing module

The four beamlets were then directed to the temporal focusing (Fig. S1B) lens (f=100mm) by a D-shaped mirror at a slight vertical angle and focused onto two small holographic diffraction gratings (1,500l/mm, Richardson 33999BK02–239H) in the Littrow configuration (Fig. S5A). The first diffraction order was spatially dispersed in the horizontal axis and collimated using the same lens before it is directed to the remote scanning module.

Remote scanning module

The four beamlets passed through a PBS and a quarter-wave plate (QWP) before being focused by the remote scanning lens (f=60mm) onto the remote scanning mirrors (Fig. S5A). Mirror holder chucks with different axial arrangements of four mirrors (Edmund Optics) were used to direct the beamlets to different positions in the sample in the different configurations shown in this work. The mirror holder chucks are mounted on a fast voice coil actuator (Equipment Solutions) which allows rapid remote scanning to continuously acquire volumes by saw-tooth axial z-scanning. The same lens re-collimates the beamlets and after the second pass through the QWP, the PBS directs the beamlets to the microscope. The high-speed driver (Equipment Solutions) allowed for an optimized flyback and settling time of ~10ms over a ~150–250μm travel range and ~20ms over a 600μm axial range in the sample.

HyMS microscope setup

The HyMS microscope setup is illustrated in Fig. S5A. It was built around a Sutter MOM scope (MP-285) and both the two-photon and three-photon path use an identical galvo/resonant scanning (15.5kHz) mirror pair (6215H, Cambridge Technology, and SC-30, EOPC). The two resonant scanners were controlled in a phased-locked master/slave configuration (EOPC). The scan and relay lenses were chosen such that the 2p scanned temporal focusing spot on the grating is imaged into the sample exciting a volume of 5×5×15μm and that the 3p spot excites a volume of 1.5×1.5×9.4μm, respectively. The 960nm and 1,300nm channels were combined before the tube lens (f=400mm) using a custom low-dispersion dichroic (AHF). We used a 0.8 NA, 16× water-immersion, long working distance microscope objective (CFI75LWD16xW2, Nikon). The objective was mounted on a long travel range (1mm), high-speed piezo stage (NPFocus1000, NPoint) which was used for three-photon and hybrid recordings to continuously acquire volumes by saw-tooth axial z-scanning of the microscope objective. The piezo used a high-speed driver (NPoint) which allowed for an optimized flyback and settling time of ~20ms over a ~150–250μm travel range. Signal was collected using wide-angle optics, and detection was performed using a photon multiplier tube (PMT, H10770-PA40, Hamamatsu), protected by a near-infrared (NIR)-blocking filter (HC 770/SP, Semrock).

Data acquisition scheme

The data acquisition scheme is shown in Fig. S5B. The PMT signal was recorded by an 800MHz digitizer (National Instruments). A field programmable gate array (FPGA) (National Instruments) allowed for synchronization of the voxel acquisition to the pulse repetition rate of the laser and to realize a scheme in which each voxel was excited only by a single laser pulse. The FPGA clock at 750MHz was provided by an evaluation board (Analog Devices) and phase-locked to the FCPA oscillator frequency. We triggered the FPGA digitizer board by individual laser pulses from the 960nm channel at 4.7MHz and collected the signal from the PMT within 5 of the 1.33ns samples (Fig. S1H). The line synchronization was provided by the master resonant scanner. Using a fast rise time (1ns) PMT, we were able to de-multiplex the fluorescent signals from subsequent beamlets at 8ns spacing with negligible dynamic (Fig. S1I) and static cross-talk (Fig. S1J). The laser intensity was blanked during the turnaround of the resonant scanner and axial flyback time and modulated with increasing image depth by Pockel’s cells (350–160-BK for the 960nm channel, and 350–80-LA for the 1,300nm channel, Conoptics).

Rational for using a single pulse-per-voxel scheme in 2p and 3p excitation

An element of our imaging approach is the synchronized data acquisition to the laser repetition rate which allows to record from the sample at the ultimate achievable signal using a single-pulse-per-voxel scheme. In the following we will elaborate this advantage for nonlinear signal acquisition for the cases of 2p and 3p excitation.

The fluorescence signal, Ne,2p, in 2p excitation via a pulsed laser source is proportional to the number of absorbed photons per voxel and laser pulse, and is given by (So et al., 2000):

with E = P0/f being the pulse energy at the sample plane, P0 the average laser power, f the laser pulse repetition rate, τ the pulse length, λ the central wavelength, A the excitation area at the sample, and δ the axial confinement of the excitation.

It can be seen that the fluorescence signal depends on the pulse energy as Ne,2p ~ E2. Thus, if the pulse energy E is split over n pulses due to an n-times higher repetition rate, the generated signal below the fluorophore saturation limit is reduced by n because

This means that for a given average power the signal is maximized for the maximum pulse energy and therefore for the lowest possible repetition rate. Since each imaging voxel requires at least one excitation pulse, we conclude that the fluorescence signal and the SNR are maximized when a one-pulse-per-voxel scheme is used.

Next, we look at the same consideration for the case of 3p excitation: Here, the fluorescence signal, Ne,3p, is proportional to the third power of the excitation photon flux, resulting in:

Since 3p excitation has a higher nonlinearity in the signal dependence on the pulse energy, Ne,3p ~ E3, the effect is even stronger pronounced: Averaging n pulses in the case of 3p results in an n2-reduction of the fluorescence signal:

Thus, in 3p excitation it is crucial to minimize the laser repetition rate to the desired sampling rate and acquire the signal synchronized to the laser clock in a one-pulse-per-voxel scheme.

Tissue heating due to linear absorption is the main known damage mechanism in nonlinear microscopy and it has been shown that average power levels above ~250mW can lead to heat-induced tissue damage as reported via immunohistochemical markers (Podgorski and Ranganathan, 2016; Prevedel et al., 2016). The tolerable levels of average power impose a limitation on the pulse energy at our effective repetition rate and for our larger, light-sculpted PSF, while using a single-pulse-per-voxel excitation scheme results in an √n-times SNR gain for the same average power (compared to averaging n laser pulses). We would also like to point out that this acquisition scheme not only allows to maximize the obtainable fluorescence signal and SNR from each voxel in both 2p and 3p excitation, but that it also allows for the lowest possible heat penalty due to linear absorption by the sample for a given average excitation power.

The average power densities (0.2mW/μm2) and pulse energy densities (0.04nJ/μm2) used in TeFo imaging are ~100× and ~5× lower than the corresponding values for a DL PSF (20mW/μm2 and 0.2nJ/μm2). Reported safe power densities are in the range of 2–5mW/μm2 and safe pulse energy densities are in the range of 0.025–0.06nJ/μm2 (Koenig et al., 1997; Hopt & Neher, 2001). Thus, our conditions are more than an order of magnitude below both the established linear heat-induced damage threshold and the threshold for non-linear damage while at the same time being about 100× (average power density) and 5× (pulse energy density) lower than typical values for standard DL 2p scanning microscopy.

Dynamic cross-talk analysis in spatiotemporal multiplexing

To increase the volumetric access of a multiphoton fluorescence microscope while maintaining sufficient temporal resolution, one must increase the sample acquisition rate. As discussed in the manuscript, spatiotemporal multiplexing can circumvent hardware limitations to increase this rate, however, imaging speed is ultimately limited by the fluorescence lifetime of the fluorophore of interest (Cheng et al., 2011). In the event that samples are acquired without sufficient temporal delay, the exponential decay from the first sample can leak into the second sample’s time bin, causing cross-talk and impairing the measurement fidelity.

Leakage between sample bins is only one form of cross-talk in a typical dataset, however. For example, out-of-plane fluorescence is a form of spatial cross-talk in an image, adding background to deeper planes and decreasing the SNR. While cross-talk is unavoidable, it can be tolerable to a certain degree. Ultimately, the goal of functional neuronal imaging is to resolve Ca2+ activity transients, thus the threshold for acceptable cross-talk must reflect the dynamics of the system.

In order to optimize the delay between multiplexed excitation beamlets in these experiments, we consider the dynamic cross-talk as a function of each sample’s temporal bin width (programmatically set by control of the digitizer through the microscope control software). Specifically, we consider the peak ΔF/F0 value of a signal from a given Ca2+ transient, Ik (t), measured within a primary sampling bin of a given width in time, τ. If the contaminating signal measured in the subsequent time bin has decayed below the baseline fluorescence of the neuron, this will not cause impairment of the extraction fidelity. Accordingly, the dynamic cross-talk, χ, is given by

where tpeak is the time point coincident with the peak ΔF/F0 value of transient k, and the median of Ik(t) approximates the baseline fluorescence of the neuron. Fig. S1I shows the mean cross-talk as a function of sample bin width for our microscope. In order to preserve fidelity while maximizing acquisition speed, we chose to operate with a bin-width of 8ns.

Experimental verification of TeFo recording against a structural and functional ground truth

A DL 2p excitation path was added to our setup for experimental verification of our TeFo recordings by allowing for a simultaneous recording of a functional and structural ground truth information. Both the TeFo and DL 2p path use identical galvo/resonant scanning (15.5kHz) mirror pairs (6215H, Cambridge Technology, and SC-30, EOPC). The two resonant scanners were controlled in a phased-locked master/slave configuration (EOPC). The TeFo and DL 2p channels were combined before the tube lens using a 50:50 non-polarizing beam splitter. Using our spatiotemporal multiplexing scheme, we have made 6min single-plane recordings (165×165μm FOV) at varying imaging depths (~100–600μm) in awake and behaving animals by simultaneously recording the same neuronal population activity with a DL PSF and our light-sculpted TeFo PSF. The recordings were motion-corrected using NoRMCorre, and neuronal footprints were extracted using the CaImAn software package (Giovannucci et al., 2019; Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016). The extraction algorithm was optimized by sweeping the spatial thresholds and comparing the extracted footprints to a visual inspection of the initial dataset with further hand-annotation of the optimized result. The detected footprints form the ground-truth basis for the subsequent comparison of the TeFo dataset and the high-resolution dataset. Next, both the TeFo and the DL dataset were fed into the CaImAn algorithm to extract neuronal footprints. These spatial footprints were compared to the ground-truth in order to compute the sensitivity and precision of extraction. For both modalities, we swept CaImAn’s spatial thresholds (as with the initial ground-truth) in order to maximize sensitivity and precision scores. In the single plane validation experiments due to the lower axial extent of the DL PSF, there are real neurons visible and identified in the light-sculpted TeFo PSF recording (Fig. 2G) which are out-of-focus in the DL recording.

This is a direct consequence of the fact that due to fundamental limitations of the hardware speed for the DL path functional ground truth validation experiments could only be performed for individual planes at different depths and not volumetrically. As a result, the presented precision values for the light-sculpted TeFo PSF as reported in Fig. 2I are systematically underestimated and thus a very conservative estimate. However, none of the volumetric recordings reported in this work are affected by this systematic underestimating of P, since in those recordings the axial dimension is densely sampled to ensure every neuron is detected by the signal processing algorithm only once by identifying and merging the spatial components in adjacent planes.

Cerebral vasculature visualization

For visualization of cerebral vasculature, 50μl of 2.5% FITC-Dextran dye (70kDa) (46945; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected into the right retro-orbital sinus under anesthesia. The animal remained under 1.5% isoflurane anesthesia throughout imaging and body temperature was maintained at 37°C. Upon completion of imaging, the animal was allowed to fully recover from anesthesia before being returned to its home cage. Using the spatiotemporal multiplexing, a structural volumetric stack was simultaneously acquired with the TeFo and the DL 2p path. Small capillaries (~3μm diameter) at various imaging depths were identified using the DL 2p channel and then used as fluorescent fiduciaries to measure the axial extent of the TeFo PSF. We found that, over a range from ~300–600μm imaging depth, the axial extent of our light-sculpted PSF is maintained inside scattering tissue at the desired ~15μm axial confinement with only a moderate deviation of 5–10% (Fig. S1C–G).

Auditory setup and stimulus

The noise level at the experimental setup was measured with a pressure pre-polarized condenser microphone system (PCB Piezotronics Inc.). The system was operated through a PXIe-6341 (National Instruments) card at 500kHz bandwidth with a 16bit A/D converter. The ambient noise was found to be below the threshold for the mouse hearing. Auditory stimuli were digitally generated at a sampling rate of 500kHz. The output signal then went through an electric loudspeaker driver and a programmable attenuator (Tucker-Davis Technologies), located at ~8 cm from the contra-lateral ear. For the pure tone stimulus, we used 12 amplitude-modulated pure tones in the low frequency band range from 6–81kHz at octave-based separations. All stimuli are cosine-squared gated (1ms on and off) and played in a random order in 3s intervals. Each stimulus was run at the same attenuation level of 60dB SPL which was at least 40dB SPL above the noise level in the laboratory and 20–40dB SPL above the hearing threshold of mice. During a typical 20min experiment ~340 stimuli were presented.

Experimental verification of 3p imaging modality against a structural and functional ground truth

We have made 6min single-plane recordings (170×170μm FOV) at varying imaging depths (600–1,100μm) in awake and behaving animals with high-resolution sampling. By removing pixels from the high-resolution recording, our 3.4μm sparse sampling condition for 3p imaging was retrieved from the same dataset. The neuronal signal extraction from this downsampled dataset was then compared to the results of the high-resolution dataset. The recordings were motion-corrected using NoRMCorre, and neuronal footprints were extracted using the CaImAn software package (Giovannucci et al., 2019; Pnevmatikakis et al., 2016). The extraction algorithm was optimized by sweeping the spatial thresholds and comparing the extracted footprints to a visual inspection of the initial dataset with further hand-annotation of the optimized result. The detected footprints form the ground-truth basis for the subsequent comparison of the two datasets. Next, both the 3.4μm sampling 3p recording and the densely-sampled, DL 3p dataset were fed into the CaImAn algorithm to extract neuronal footprints. These spatial footprints were compared to the ground-truth in order to compute the sensitivity and precision of extraction. For both datasets, we swept CaImAn’s spatial thresholds (as with the initial ground-truth) in order to maximize sensitivity and precision scores.

Imaging protocol

Awake mice were head-fixed on a custom-build treadmill and the window was aligned perpendicular to the optical axis using two goniometers and an alignment tool with a red laser diode and a PBS. The belt position was read out using a quadrature modulated optical encoder by an Arduino Uno. The belt position readout was synchronized to the acquisition using triggers. The behavior was recorded by a webcam (Logitech). To elicit running, air puffs were used occasionally during the recording. The microscope was controlled by Matlab (The Mathworks) using the open-source version of ScanImage 5.2 (Vidrio Technologies) with custom-developed ScanImage and FPGA code to allow for the above described sampling scheme. For 2p-MuST recordings, the lateral pixel size was ~5μm, and for 3p recordings the lateral pixel size was ~3.4μm. The temporal fill fraction for the fast axis was 0.9. The axial spacing between planes for volumetric imaging was ~15μm (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5) or ~13.3μm (Figs. 6 and 7). Table S1 provides an overview of the achievable imaging rates for example target volumes as a function of the multiplexing arrangement and axial scan strategy. Depending on depth and configuration, imaging was performed using a total, time-averaged excitation power of 36–190mW depending on the imaging modality out of the front lens of the microscope objective. A typical imaging session lasted continuously for 5–30min. For 3p and hybrid imaging, D2O (Sigma-Aldrich) was used instead of H2O as the immersion medium. For 2p recordings in auditory cortex, ultrasonic gel (Bio-Medical Instruments) was used instead of H2O as the immersion medium.

Data processing

The data processing pipeline is illustrated in Fig. S2A. Data processing was performed using custom software implemented in Matlab on a high-performance computation cluster (Data File S1). The channels were de-interleaved and the 2p and 3p data were separated. All datasets were corrected for the sinusoidal resonant scanner distortion: Due to the one-pulse-per-voxel excitation and detection scheme, no pixel mask for sample averaging could be applied during the data acquisition. Thus, data were resampled along the fast axis to correct for the sinusoidal trajectory. All datasets were motion corrected using the volumetric version of NoRMCorre (Pnevmatikakis and Giovannucci, 2017). Ca2+ activity traces were extracted using the volumetric patch version of CaImAn (Pnevmatikakis and Paninski, 2013; Giovannucci et al., 2019). CaImAn was initialized using the greedy method and the number of components to be found set at 2 times the number of neurons expected in the volume using the average neuronal density in the respective brain region. CaImAn was run with default parameters except for the following parameters that were adjusted to account for the different sampling in our recordings compared to standard DL recordings: SD of the Gaussian kernel, search method ellipse with appropriate minimum and maximum size of the ellipse, and the minimum and maximum size of each spatial component (Data File S1). In the case of 3p data, spatial components were identified on the 5-frame compounded data, but activity traces were extracted on the original, un-compounded data with 3× moving averaging (Fig. S4B–G). To avoid the accumulation of noise from the pixels that were sampled without any laser excitation present, these pixel values were set to ‘0’. This was done by recording a frame time stamp and a continuous trigger counter from 0 to 4 that was stored in the first pixel of each line in the image data. Activity traces were deconvolved using the OASIS implementation in CaImAn (2nd order autoregressive model) for visualization purposes.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using raw Ca2+ activity traces without spatial or temporal averaging. Histograms of the maximum ΔF/F0 values for the neuronal traces were computed from the Ca2+ traces. Histograms of the nearest neighbor distances were computed using ‘knnsearch’ with k=2 and the Euclidian distance metric on the centroid positions of the spatial components. Correlation coefficient matrices were computed from raw Ca2+ traces using the ‘corr’ function and the Spearman-type correlation.

For processing of the auditory stimulus experiments, the first 20 frames (~4s) following the stimulus onset were defined as the response window and the mean trial response was defined as the average ΔF/F0 within that window for all presentations of the same stimulus for each neuron. To identify sound-driven neurons, we correlated the mean trial response with an ideal Ca2+ transient corresponding the ΔF/F0 generated by 10 action potentials in GCaMP6s. Neurons with a correlation greater than 0.8 and a maximum ΔF/F0 with respect to the baseline above 0.1 were identified as neurons tuned to the frequency. The sound-driven neurons were used to determine the best frequency (BF), the frequency associated with the highest peak ΔF/F0 across all frequency responses.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering was performed using the ‘linkage’ function. Assignments of imaging depth to cortical layers or hippocampal regions were based of the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2018). Correlation coefficient matrices were then sorted with priority to brain region assignment and then cluster assignment. Principal component analysis was performed using the ‘pca’ function. For cross-correlation of the activity traces with the treadmill velocity, the treadmill velocity was convolved with a Ca2+ kernel and cross-correlation was computed using the ‘xcorr’ function. Mutual information was calculated under the Gaussian assumption, I(X;Y) = 1/2 log(|Σ(X)|/| Σ (X|Y)|, where Σ(X) and Σ(X|Y) indicate the sample covariance and conditional covariance matrices, respectively (Barrett and Seth, 2011). Both the principal component analyses and mutual information calculations on z-scored ΔF/F0 traces were performed over 300 random permutations of the neuron indices, for which the sample size was varied from 10 to the total number of neurons. Z-scores were computed using the ‘zscore’ function. Significance p-values between stationary periods and during locomotion were calculated using the ‘ranksum’ function.

Data visualization

Plots were generated using Matlab. Ca2+ traces in heatmaps were individually normalized for visualization. Denoised datasets were generated by multiplying the spatial components (neuronal footprints) with the deconvolved time series of the neuronal activity. For 3D visualization, the dynamic range of the denoised datasets was logarithmically compressed before 3D rendering was performed using Imaris (Bitplane). Figure panels were prepared in Inkscape (The Inkscape Project) and Adobe Illustrator CC (Adobe Inc.), and videos were edited using Blender Video Editor (Blender Foundation).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

A total of 69 neuronal recordings from 20 animals were analyzed. Only animals, for which all animal procedures (surgeries, viral injections and Ca2+ indicator expression) worked successfully, were included in the study. We found imaging results and data quality to be reliably reproducible and consistent, both across imaging sessions with the same animal, and across animals.

Statistical tests were performed using Matlab. Normally distributed data are presented as mean with standard deviation. The size and type of individual samples, n, for given experiments is indicated and specified in Figure legends.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Our custom data-processing pipeline is available to download as Data File S1. Data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material