Abstract

We examined the roles of maternal and child lifetime stress exposures, infant temperament (orienting/regulation, surgency/extraversion), and maternal caregiving during infancy and preschool on preschoolers’ working memory and inhibitory control in a sociodemographically diverse pregnancy cohort. Working memory was predicted by infant orienting/regulation, with differential effects by level of maternal cognitive support in infancy; maternal lifetime stress exposures exerted independent negative effects on working memory. Inhibitory control was positively associated with maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy, which mediated the effects of maternal lifetime stress exposures on inhibitory control. These findings have implications for interventions designed to optimize child executive functioning.

Keywords: working memory, inhibitory control, stress, caregiving, temperament

Introduction

Executive functioning (EF) abilities encompass a number of mental processes that underlie regulation of goal-directed behavior, academic and social competencies, and mental health. Aberrations in EF are implicated in numerous neurodevelopmental and clinical disorders (Garon, Bryson, & Smith, 2008; Segalowitz & Davies, 2004; Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Gaertner, 2007). Data indicate that behaviors emerging as early as infancy are developmental antecedents of more complex executive skills that develop into young adulthood (Wiebe et al., 2011). Moreover, EF during early childhood predicts adolescent and adult functioning across a range of domains (e.g., school achievement, psychopathology), leading some to conclude that identifying factors influencing the development of EF in early childhood is one of the most important research topics in developmental and psychological science (Moriguchi & Shinohara, 2018).

EF comprises three distinct domains: working memory, inhibitory control, and set shifting/cognitive flexibility (Frick et al., 2017; Spruijt, Dekker, Ziermans, & Swaab, 2018). To date, research on determinants of EF, particularly in early childhood, has tended either to treat these underlying abilities as a unitary, domain-general process or to examine discrete abilities (e.g., inhibitory control) in isolation. Different theories regarding EF development have influenced these approaches, with some suggesting that when EF skills are beginning to emerge in early childhood, EF is a more unitary construct that differentiates into distinct components in later development (Wiebe et al., 2011; Zeytinoglu, Calkins, Swingler, & Leerkes, 2017). Others propose that different aspects of EF have different developmental trajectories that are initially distinct and then become more coordinated and integrated into more complex EF skills over time (Frick et al., 2017; Garon et al., 2008). Moreover, while data suggest that the skills underlying effective EF begin to develop in infancy and are dependent on both intrinsic and environmental factors, most studies have examined intrinsic and environmental factors separately without consideration of how such factors may interact to influence EF abilities (Frick et al., 2017). Research that explores whether different EF skills are influenced by different intrinsic factors and exhibit differential vulnerability to various environmental influences in early life may address the field’s underlying questions about the structure of EF over the course of development and further our understanding of early life factors that contribute to EF deficits.

Studies suggest that early life stress exposures negatively impact EF abilities. Performance on various EF measures, including working memory, attentional and inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility, has been associated with prenatal and childhood stress exposures (Kishiyama, Boyce, Jimenez, Perry, & Knight, 2009; Lipina, Martelli, Vuelta, & Colombo, 2005; Plamondon et al., 2015). Moreover, studies link pre- and postnatal stress exposures to structural and functional changes in brain areas subserving EF abilities (e.g., prefrontal cortex), degree of balance between higher order prefrontal control systems and lower limbic systems, and dysfunction of stress regulatory systems that interact with these brain areas (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [HPA]; Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009; Suor, Sturge-Apple, & Skibo, 2017; Zhu et al., 2014). The prenatal period appears particularly sensitive to the impact of maternal stress/trauma on offspring brain development via alterations in maternal gestational biology (e.g., endocrine, immune, metabolic systems) that influence fetal neural anatomy and physiology (Buss et al., 2017). Importantly, most studies define prenatal stress in relation to stressors that occur during pregnancy; however, evidence suggests that maternal exposures prior to conception may influence fetal development via persistent disruptions to maternal biology (Enlow et al., 2017; Enlow et al., 2009). Notably, findings regarding prenatal stress effects on offspring EF have been inconsistent, possibly due to varied operationalizations of stress across studies. Furthermore, there is some evidence that different domains of EF may be differentially impacted by prenatal stress (Plamondon et al., 2015). Research is needed that considers a comprehensive assessment of both maternal and child lifetime stress exposures to determine the influence of type and timing on child EF development.

Studies have also linked maternal caregiving behaviors to child EF in early life. Caregivers are hypothesized to influence EF development by acting as external regulators, aiding the infant in regulating attention and emotions through sensitive responding to infant cues (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010). These interactions shape the development of associative learning mechanisms, attentional control, and emotion regulation, which form the foundation of later EF abilities (Cheng, Lu, Archer, & Wang, 2017; Sheridan, Peverill, Finn, & McLaughlin, 2017). Child EF abilities have been linked to a range of caregiver behaviors, including behaviors supportive of cognitive skills development, such as attention-directing behaviors, stimulation, and scaffolding/autonomy support, and behaviors supportive of emotion regulation development, such as sensitivity, maternal-child attachment quality, and discipline strategies (Bernier, Carlson, Deschenes, & Matte-Gagne, 2012; Conway & Stifter, 2012; de Cock et al., 2017; Li et al., 2016; Spruijt et al., 2018; Suor et al., 2017; Zeytinoglu et al., 2017). Importantly, there is evidence that the types of caregiving behaviors that support EF abilities may vary by the specific EF domain and the age of the child, reflecting the different neural developmental trajectories underlying each EF domain and the different environmental supports required to optimize these trajectories (Cheng et al., 2017; Spruijt et al., 2018). However, the extant literature has not consistently identified which caregiving qualities during specific developmental periods are most important in promoting distinct EF domains (Bernier et al., 2010; Suor et al., 2017). The role of caregiving quality in infancy in predicting later EF abilities has been particularly understudied (Cheng et al., 2017; Conway & Stifter, 2012).

Supportive, sensitive caregiving may be especially important for promoting EF abilities among vulnerable children, including those exposed to stress/trauma (Plamondon et al., 2015). For example, evidence suggests that a poor caregiving environment has greater negative impact on children who experienced a stressed gestational environment (Buss et al., 2017; Plamondon et al., 2015), and positive, emotionally supportive caregiving mitigates the negative impact of direct trauma exposure on children (Nelson & Bosquet, 2000). However, parenting stress has been linked to decreased caregiving quality as well as to poorer child EF, in part via indirect effects through caregiving quality (de Cock et al., 2017). Trauma in caregivers’ own childhood may have particularly detrimental impact on later caregiving quality (Moehler, Biringen, & Poustka, 2007). Thus, a lifetime perspective in characterizing caregiver stress/trauma exposures may be critical in understanding the independent and joint effects of stress and caregiving quality on child EF development.

Measures of infant temperament have also been associated with child EF (Frick et al., 2017; Leve et al., 2013). Conceptually, temperament is relevant for EF as it refers to stable individual differences in traits germane to EF, including attention, self-regulation, and surgency (Bush et al., 2017; Frick et al., 2017). However, the extant literature is unclear as to which temperament characteristics are most relevant for EF and whether different temperament domains, particularly in infancy, predict different EF abilities. Notably, a number of studies have found associations between maternal prenatal stress/negative life events and infant temperament (Bush et al., 2017; Van den Bergh et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2014), suggesting a potential pathway from prenatal stress exposures to child EF abilities through infant temperament (Lin, Crnic, Luecken, & Gonzales, 2014). Although there is some evidence that prenatal stress predicts infant levels of regulation and extraversion/surgency, the literature is limited and mixed on magnitude and direction of effects (Bush et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2014; Lipton et al., 2017). The large majority of studies on stress and infant temperament have focused on negative affectivity/difficult temperament, leading to calls for more research on stress exposure effects on the temperament domains of effortful control and extraversion (Van den Bergh et al., 2017), which may be particularly relevant to the development of EF abilities (Frick et al., 2017).

Additionally, there is evidence that temperament influences children’s sensitivity to environmental influences and that children with different temperamental profiles benefit from different caregiving styles (Amicarelli, Kotelnikova, Smith, Kryski, & Hayden, 2018; Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Conway & Stifter, 2012; Frick et al., 2017). The specific temperament characteristics that influence children’s responsivity to caregiving behaviors relevant for EF development are unknown, necessitating research that examines interactions between caregiving and child temperament in predicting child EF abilities (Bernier et al., 2012). Moreover, different theoretical models have been proposed that generate different hypotheses as to how temperament and caregiving may jointly influence child EF development. A differential susceptibility model hypothesizes that certain temperamental profiles enhance susceptibility to both enriched and adverse caregiving environments, whereas a diathesis-stress model hypothesizes that temperamental profiles influence susceptibility specifically to adverse caregiving environments, and a vantage sensitivity model hypothesizes that temperamental profiles influence susceptibility specifically to enriched caregiving environments (Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Li et al., 2016; Pluess & Belsky, 2013). More studies are required to (a) explicate the particular infant temperament domains that predict specific child EF abilities; (b) test whether infant temperament mediates links between early stress exposures and later EF abilities; (c) explore whether certain temperament profiles influence a child’s responsiveness to caregiving behaviors that support or impede the development of child EF abilities; and (d) examine whether the joint effects of infant temperament and caregiver behaviors on EF vary based on the specific EF domains assessed.

The overall goal of this study was to leverage a longitudinal pregnancy cohort to elucidate prenatal and early childhood determinants of EF in the preschool period. We focused specifically on examining the effects of maternal and child lifetime stress exposures, infant temperament, and maternal caregiving quality in infancy and the preschool period on two domains of EF: child working memory and inhibitory control. These EF domains were chosen because they (a) undergo rapid changes over the first years of life, (b) can be validly measured in the preschool period, and (c) enable the maturation of other EF abilities (e.g., cognitive flexibility) in later development and thus are broadly important for long-term functioning (Spruijt et al., 2018; Wiebe et al., 2011). For analyses involving infant temperament, we focused on the established infant temperament domains of orienting/regulation and extraversion/surgency (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003). We hypothesized that greater orienting/regulation predicts greater child working memory due to its inclusion of items assessing attentional abilities and predicts greater child inhibitory control due to its inclusion of items assessing self-regulation abilities; notably, others have contended that early attentional processes in infancy reflected in measures of temperamental regulation play a major role in the development of EF and self-regulation (Frick et al., 2017; Rabinovitz, O’Neill, Rajendran, & Halperin, 2016). We hypothesized that greater infant extraversion/surgency predicts lower child inhibitory control due to its inclusion of items assessing activity level and approach behaviors; to date, evidence is limited and mixed as to how extraversion/surgency may relate to EF (Frick et al., 2017). We further tested whether the impact of maternal caregiving on child working memory and inhibitory control varied by infant temperament. Finally, we considered whether any associations between maternal trauma/stress exposure history and child EF were independent of or mediated by infant temperament and/or maternal caregiving quality, given data suggesting that maternal stress can influence infant temperament and impair caregiving behaviors (Van den Bergh et al., 2017).

Methods

Participants

Participants were mother-child dyads enrolled in the PRogramming of Intergenerational Stress Mechanisms (PRISM) study, a prospective pregnancy cohort originally designed to enroll N = 276 mother-child dyads to examine the role of maternal and child stress exposures on child development. Pregnant women were recruited from prenatal clinics in urban hospitals and community health centers in the Northeastern United States. Eligibility criteria included: 1) English- or Spanish-speaking; 2) age ≥ 18 years at enrollment; 3) single gestation birth. Exclusion criteria included 1) maternal endorsement of drinking ≥ 7 alcoholic drinks/week prior to pregnancy recognition or any alcohol following pregnancy recognition; 2) maternal positive HIV status, which would influence/confound biomarkers of interest. Based on screening data, there were no differences in race/ethnicity, education, or income between women who enrolled in PRISM and those who declined. Original funding supported recruitment of the cohort and follow-up to age 2 years. Additional funding allowed for assessments of a subsample of families when the children were approximately 3.5 years of age (preschool assessment). PRISM participants were eligible for the follow-up study if they had previously provided biosamples necessary to meet the aims of the additional funding award. The current analyses include 53 mother-child dyads who provided data from pregnancy through the preschool assessment. The sample in this study did not differ from PRISM cohort members not included in this study on child gender, maternal age, or maternal marital status. PRISM participants who did and did not complete this study differed on maternal education (current sample less likely to have not completed high school, more likely to have attained college degree) and maternal race/ethnicity (current sample more likely to be White or Black, less likely to be Hispanic). None of the children in the current analyses were reported to have a developmental or brain-related disorder.

Procedures

Maternal sociodemographics were assessed shortly following recruitment in pregnancy (M = 26.9 weeks gestation, SD = 8.1 weeks gestation). Within two weeks of enrollment, trained research assistants administered interviews inquiring about maternal lifetime stress exposures. When the children were 6 months of age, mother-infant dyads completed standardized laboratory assessments that included observations of maternal caregiving behaviors, and mothers completed a questionnaire regarding infant temperament (infant assessment). When the children were approximately 3.5 years of age, mothers and children participated in a home visit and a laboratory visit (preschool assessment). At the home visit, mothers completed questionnaires regarding their own and their children’s exposure to stressors since the pregnancy assessment. An assessment of the quality of cognitive stimulation and emotional support available to the child was also implemented. At the laboratory visit, children completed measures of working memory and inhibitory control. Study procedures were approved by the relevant institutions’ human studies ethics committees. Mothers provided written informed consent.

Measures

Maternal and child exposure to stressors, lifetime

Maternal stress and trauma exposures

Maternal exposure to potentially stressful and traumatic events was measured at two time points using the Life Stressor Checklist-Revised (LSC-R; Wolfe & Kimerling, 1997). The LSC-R assesses exposure to 30 events (e.g., experiencing a serious accident, natural disaster), including experiences particularly relevant to women (e.g., sexual assault, interpersonal violence). The LSC-R has established test-retest reliability and validity in diverse populations (McHugo et al., 2005; Wolfe & Kimerling, 1997). During pregnancy, mothers were asked to report on their lifetime exposure to each event up until the point of the interview. At the preschool assessment, mothers were asked to report on their exposures since the prior interview. For each time point (lifetime through index child’s pregnancy; child’s lifetime), a continuous stress exposure score was derived by summing the number of endorsed events, with higher scores indicating exposure to more events (possible range 0-30).

Child lifetime trauma exposures

Child lifetime exposure to 24 potentially traumatic events was assessed via the Traumatic Events Screening Inventory-Parent Report Revised (TESI-PRR; Ghosh Ippen et al., 2002), administered to mothers. The TESI-PRR was created specifically to assess trauma exposures among young children (birth to age 6 years), inquiring about events likely to occur and be stressful for young children (e.g., prolonged separation from caregiver, serious medical incident). The TESI-PRR has been identified as the best measure available for trauma exposures in young children, due to its thoroughness and developmental sensitivity (Brewin, 2005). A continuous trauma exposure score was derived by summing the number of endorsed events, with higher scores indicating exposure to more events (possible range 0-24).

Infant temperament

Infant temperament was ascertained using the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R; Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003). The 191-item IBQ-R was rationally derived, based on a definition of temperament as constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003), and has demonstrated reliability and validity (Parade & Leerkes, 2008). Mothers rated the frequency that their infant engaged in specific day-to-day behaviors in the prior week using a 7-point scale, with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Scores were summed across items according to IBQ-R scoring criteria to create 14 scales assessing a variety of behavioral domains. Research with the IBQ-R has identified three factors derived from the 14 scales: orienting/regulation, extraversion/surgency, and negative affectivity (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003). As noted in the Introduction, analyses focused on the factors orienting/regulation (Duration of Orienting, Soothability, Cuddliness, and Low Intensity Pleasure scales) and extraversion/surgency (Activity Level, Approach, Vocal Reactivity, High Intensity Pleasure, Smiling and Laughter, and Perceptual Sensitivity scales).

Maternal caregiving behaviors

Infancy

When the children were 6 months of age, they completed a 10-minute video-recorded free play with their mothers in the laboratory. Trained research assistants scored maternal, infant, and dyadic behaviors using a modified version of the Parent-Child Interaction Rating Scales (PCIRS; Sosinsky, Carter, & Marakovitz, 2004), a detailed scoring scheme created for the Connecticut Early Development Project. PCIRS scales were adapted from several well-validated behavioral coding schemes, including the NICHD Study of Early Child Care’s 24-month and 36-month Mother-Child Interaction Rating Scales (MCIRS) for the Three-Boxes Procedure (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999); the Caregiver-Child Affect, Responsiveness, and Engagement Scales (C-Cares; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2002); the Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA; Clark, 1999); and the Emotional Availability Scales (Biringen, Robinson, & Emde, 1994). The PCIRS was developed for use in a mother-toddler sample and adapted in consultation with the PCIRS developers for use in the current study with mother-infant dyads.

For the purposes of these analyses, 11 scales were considered that focused on maternal behaviors or quality of maternal-infant interactions. The average inter-rater reliability across scales and raters was 0.74. The scales were subjected to principal component analyses with Varimax rotation, revealing two factors suggestive of a cognitive support score and an emotional support score. The scales that loaded most heavily on the cognitive support score included quality of reciprocal interaction between mother and infant, maternal stimulation of infant cognitive development, dyadic joint attention, amount of language used by mother, mutual dyadic enjoyment, maternal positive regard for the infant, and maternal quality of language toward the infant. The scales that loaded most heavily on the emotional support score included maternal intrusiveness (negative loading), maternal negative regard for the infant (negative loading), maternal sensitivity, and dyadic affective mutuality. These cognitive and emotional support factor scores were used as measures of maternal caregiving behaviors in infancy, with higher scores indicating higher levels of supportive behaviors.

Preschool

During the home visit at the preschool assessment, the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment-Short Form (HOME-SF) was administered to assess the support available to promote the child’s cognitive and socioemotional development. The measure has demonstrated moderate stability across time (Bradley, 1989), and prior research has documented associations between child IQ and HOME subscales (Pianta & Egeland, 1994). The HOME-SF provides ratings on two subscales: cognitive stimulation and emotional support. The cognitive stimulation scale rates the child’s access to cognitively stimulating items and activities in daily life (e.g., access to books, assistance with learning shapes and colors, outings to museums). Higher scores indicate greater stimulation available. The emotional support scale assesses the child’s time spent with family, ability to make choices around food, and exposure to television. The emotional support scale also includes ratings of the caregiver’s use of a range of techniques for dealing with child aggression, with higher scores given for the endorsement of a variety of non-harsh methods (e.g., calming child, talking with child, giving child a chore). Higher scores on the emotional support scale indicate greater emotional support provided to the child.

Child executive functioning, preschool period

Working memory

Children completed the Nebraska Barnyard Task (NBT; Chevalier, James, Wiebe, Nelson, & Espy, 2014; Clark et al., 2014; Wiebe et al., 2015; Wiebe et al., 2011) to assess working memory. The NBT is a memory span-type task that requires the child to remember increasing sequences of animal names. During a training phase, the child was presented with 4 colored buttons arranged in a grid-like pattern on a computer screen. Each button included a picture of an animal and emitted a sound corresponding to the animal when pressed via touchscreen. Children were encouraged to memorize each animal’s location. The animal pictures were then removed, leaving only the colored buttons. The children were then asked to push the buttons corresponding to progressively increasing sequences of animal names read aloud. Up to three trials were administered for each sequence level. Testing was discontinued after the child responded incorrectly to all three items for a sequence length. The working memory score was computed as the proportion of correct responses at each span length, with higher scores indicating greater working memory capacity. The task has been validated in children as young as 3 years (Chevalier et al., 2014; Clark et al., 2014; Wiebe et al., 2015) and correlates consistently with other established measures of executive control during the preschool period (Clark et al., 2014).

Inhibitory control

Inhibitory control was assessed via a fish-shark go/no-go computer-based task designed and validated for use with preschoolers as young as 3 years, as previously described (Wiebe, Sheffield, & Espy, 2012). Briefly, children were instructed to press a button on a Cedrus RB-530 button box (San Pedro, CA) when they saw a fish and not press the button when they saw a shark. Following a training period, 40 test trials were administered in five blocks of eight trials (75% fish trials, 25% shark trials per block). For each trial, the stimulus (fish or shark) appeared on the screen for 1,500 ms or until the child pressed the button, with a 1,000-ms interstimulus interval between trials. After each button press, children received visual and audio feedback as to whether they responded correctly. No feedback was presented when the child did not press the button. Trials with response times < 200 ms were eliminated from the analysis, as recommended (Wiebe et al., 2012). The inhibitory control score was defined as the standardized difference between the hit rate/proportion of correct go trials and false alarm rate/proportion of incorrect no-go trials (i.e., sensitivity, d′), calculated by subtracting the z-score value of the hit rate right-tail p value from the z-score value of the false alarm rate right-tail p value (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005). Higher scores indicate greater inhibitory control and discrimination (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005; Wiebe et al., 2012). Go/no-go tasks are well-established, commonly used inhibitory control tasks (Casey et al., 1997).

Covariates

Covariates considered were variables the literature suggests may be associated with EF, including child age at the preschool assessment, gender, gestational age, maternal education, and maternal smoking during pregnancy (Mileva-Seitz et al., 2015; Suor et al., 2017). Gestational age, extracted from birth records, and child age at assessment were considered as continuous variables. Maternal education was scored as less than high school diploma, high school diploma/GED, some college, college degree, or graduate degree. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was categorized as yes/no based on maternal self-report of smoking at recruitment and/or in the third trimester, a validated method for classifying prenatal smoking status (Pickett, Kasza, Biesecker, Wright, & Wakschlag, 2009).

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Bivariate associations among the predictor variables, covariates, and child working memory and inhibitory control scores were determined. Multiple linear regression analyses were then fit to test whether infant temperament and maternal caregiving behaviors exerted independent effects on and/or interacted to predict child working memory or child inhibitory control, adjusting for covariates. Each model predicting working memory or inhibitory control was built by (a) including independent variables (infant temperament, maternal caregiving behaviors, stress measures), hypothesized interaction effects of relevant independent variables (infant temperament × maternal caregiving behaviors in infancy), and covariates (child age at EF assessment, gender, gestational age, maternal education, maternal smoking during pregnancy) that were associated with the dependent variable (child working memory or inhibitory control) at p < .10, and (b) stepwise deletion of these predictors at p > .20. Main effects remained in the model regardless of p value if an associated interaction effect was retained. Relevant variables were centered prior to creating interaction terms. For predicting working memory, the following interaction effects were tested in separate regression models: infant orienting/regulation × maternal cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy; infant orienting/regulation × maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy. For predicting inhibitory control, the following interaction effects were tested in separate regression models: infant orienting/regulation × maternal cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy; infant orienting/regulation × maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy; infant extraversion/surgency × maternal cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy; infant extraversion/surgency × maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy. Linear combinations of a main effect and an interaction effect calculated at low (1 SD below the mean), average (mean), and high (1 SD above the mean) levels of a moderator were used to describe the nature of any significant interactions. A priori hypotheses regarding effects of maternal stress on child EF through infant temperament or maternal caregiving behaviors were tested via mediational models if supported by bivariate correlational analyses. Due to the modest sample size, only simple (i.e., three variable) mediation models were explored. Bootstrapped confidence intervals were used to test indirect effects. Full information maximum likelihood was used throughout analyses to address missing data (5.5%).

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 1 details the sample sociodemographic characteristics. The children were primarily of normal birthweight (91% born > 2500 grams) and born full-term (94% born ≥ 37 weeks gestation); 25% of mothers endorsed smoking during pregnancy. Table 2 displays descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the predictor and outcome variables. Table 3 displays the correlation coefficients among the predictors and covariates.

Table 1.

Sample sociodemographic characteristics (N = 53)

| n† | % | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child gender (male) | 29 | 55 | ||

| Child age (years) | 3.84 | 0.25 | ||

| Child gestational age (weeks) | 39.14 | 1.44 | ||

| Child birthweight (grams) | 3357 | 531 | ||

| Child race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 22 | 42 | ||

| Black | 18 | 34 | ||

| Hispanic | 7 | 13 | ||

| Other‡ | 6 | 11 | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 32.1 | 4.7 | ||

| Maternal relationship status | ||||

| Married | 33 | 62 | ||

| Living together | 5 | 9 | ||

| Other§ | 13 | 25 | ||

| Maternal education | ||||

| Less than high school diploma | 3 | 6 | ||

| High school diploma/GED | 3 | 6 | ||

| Some college | 11 | 21 | ||

| College degree | 19 | 36 | ||

| Graduate degree | 15 | 28 | ||

| Annual household income | ||||

| < $20,000 | 9 | 17 | ||

| $20,000-$34,999 | 6 | 11 | ||

| $35,000-$59,999 | 10 | 19 | ||

| $60,000-$99,999 | 10 | 19 | ||

| $100,000+ | 16 | 30 |

Data were missing for 0 to 2 participants across variables.

The majority categorized as “other” race/ethnicity were identified by mother as Asian or multi-racial.

Other included never married, divorced, separated, and other relationship status.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for predictor and outcome variables

| M | SD | Working memory | Inhibitory control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |||

| Maternal and child stress/trauma exposures | ||||||

| Maternal lifetime stress//trauma exposures, up through pregnancy (LSC-R) | 5.90 | 3.74 | −.44 | .002 | −.37 | .016 |

| Maternal stress/trauma exposures during child’s lifetime (LSC-R) | 2.13 | 2.15 | −.21 | .122 | −.14 | .354 |

| Child lifetime trauma exposures (TESI-PRR) | 1.52 | 1.24 | −.01 | .920 | −.08 | .577 |

| Child temperament in infancy | ||||||

| Orienting/regulation (IBQ-R) | 5.29 | 0.49 | −.13 | .380 | .03 | .872 |

| Extraversion/surgency (IBQ-R) | 5.05 | 0.65 | −.09 | .557 | .22 | .184 |

| Maternal caregiving behaviors | ||||||

| Cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy (PCIRS) | 0.01 | 1.01 | .27 | .056 | .16 | .286 |

| Emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy (PCIRS) | -0.02 | 1.01 | .21 | .151 | .46 | .004 |

| Cognitive stimulation in childhood (HOME-SF) | 8.02 | 1.02 | .26 | .054 | .39 | .004 |

| Emotional support in childhood (HOME-SF) | 6.41 | 1.37 | .11 | .459 | .14 | .334 |

| Child executive functioning skills (outcomes) | ||||||

| Working memory (Nebraska Barnyard Task) | 1.10 | 0.68 | -- | -- | .33 | .025 |

| Inhibitory control (Go/No-Go Task) | 2.66 | 0.89 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Note. LSC-R = Life Stressor Checklist-Revised; TESI-PRR = Traumatic Events Screening Inventory-Parent Report Revised; IBQ-R = Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised; PCIRS = Parent-Child Interaction Rating Scales; HOME-SF = Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment-Short Form. Bolded values are statistically significant at p < .05.

Table 3.

Correlations among predictor variables

| LSC-R_P | LSC-R_C | TESI | Temp_O/R | Temp_E/S | CogSup | EmotSup | HOME_C | HOME_E | Age | Gender | GA | M_Educ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC-R_P | -- | ||||||||||||

| LSC-R_C | .67*** | -- | |||||||||||

| TESI | .46*** | .48*** | -- | ||||||||||

| Temp_O/R | −.01 | .06 | −.01 | -- | |||||||||

| Temp_E/S | .42** | .53*** | .14 | .48*** | -- | ||||||||

| CogSup | −.17 | −.27* | −.13 | .15 | .12 | -- | |||||||

| EmotSup | −.45*** | −.41** | −.40** | .01 | −.24 | .01 | -- | ||||||

| HOME_C | −.17 | −.08 | .15 | −.05 | −.09 | .32* | .23 | -- | |||||

| HOME_E | −.39** | −.35** | −.22 | −.03 | −.22 | .10 | .22 | .00 | -- | ||||

| Age | −.15 | −.11 | .24 | .02 | −.08 | .11 | −.03 | .13 | .11 | -- | |||

| Gender | −.10 | .01 | .17 | −.04 | .03 | .11 | −.12 | .29* | .00 | .07 | -- | ||

| GA | −.12 | −.23 | −.34** | −.14 | .00 | .25 | .19 | .22 | .03 | .14 | .08 | -- | |

| M_Educ | −.26 | −.48*** | −.19 | −.19 | −.23 | .25 | .43*** | .30* | .23 | .16 | .01 | .41*** | -- |

| Smoking | .08 | .11 | .01 | −.04 | −.08 | .06 | −.17 | −.10 | .09 | .00 | .01 | −.15 | −.29* |

Note. LSC-R_P = maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures through pregnancy; LSC-R_C = maternal stress/trauma exposures during child’s lifetime; TESI = child lifetime trauma exposures; Temp_O/R = infant temperament, orienting/regulation factor; Temp_E/S = infant temperament, extraversion/surgency factor; CogSup = maternal cognitive support in infancy; EmotSup = maternal emotional support in infancy; HOME_C = cognitive stimulation in childhood; HOME_E = emotional support in childhood; Age = child’s age at executive functioning assessment; Gender = child’s gender, with 1=male and 2=female; GA = gestational age; M_Educ = maternal educational attainment; Smoking = maternal smoking in pregnancy, with 0 = no; 1 = yes.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Correlational Analyses

Working memory

Poorer child working memory was associated with greater maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures through pregnancy but not with maternal or child stress/trauma exposures during the child’s lifetime (Table 2). Child working memory was not associated with maternal behaviors during either development period or with either of the infant temperament domains.

Inhibitory control

Poorer child inhibitory control was associated with greater maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures through pregnancy but not with maternal or child stress/trauma exposures during the child’s lifetime (Table 2). Higher child inhibitory control was associated with greater maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy and greater cognitive stimulation in childhood. Child inhibitory control was not associated with either of the infant temperament domains.

Regression Analyses

Working memory

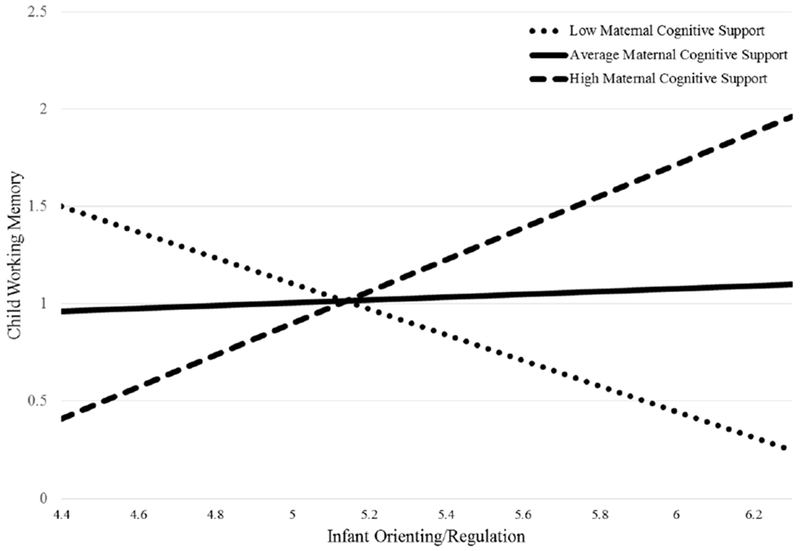

Table 4 presents the results of the final model predicting child working memory. A significant interaction effect was found between infant orienting/regulation and maternal cognitively supportive behaviors. At low and average levels of infant orienting/regulation, maternal cognitive support did not have a significant effect, ps > .05, whereas at high levels, maternal cognitive support was positively associated with child working memory (B = 0.50, 95% CI [0.24, 0.76], p < .001). Additionally, the association between infant orienting/regulation and child working memory varied by level of maternal cognitively supportive behaviors, with a negative association at low levels (B = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.53, −0.11], p = .002), no association at average levels (B = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.21], p = .669), and a positive association at high levels (B = 0.40, 95% CI [0.20, 0.69], p = .008; Figure 1). Maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures through pregnancy exerted an independent main effect, with greater maternal exposures associated with poorer child working memory. Gestational age and cognitive stimulation in childhood met a priori criteria for retention in the model as potentially important covariates. The model accounted for 46% of the variance in child working memory scores.

Table 4.

Final multiple regression analysis predicting child working memory

| B | SE B | β | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infant orienting/regulation | .08 | .18 | .05 | .669 | |

| 2. Maternal cognitive support in infancy | .14 | .08 | .20 | .103 | |

| 3. Infant orienting/regulation × maternal cognitive support in infancy | .36 | .10 | .45 | <.001 | |

| 4. Maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures | −.06 | .02 | −.33 | .006 | |

| 5. Cognitive stimulation in childhood | .11 | .08 | .16 | .169 | |

| 6. Child gestational age | .10 | .06 | .22 | .059 | |

| R2 = 0.46 |

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of maternal cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy on the association between infant orienting/regulation temperament domain and child working memory in the preschool period. At average levels of maternal cognitive support, there was no association between infant orienting/regulation and child working memory. At low levels of maternal cognitive support (1 SD below mean), there was a negative association between infant orienting/regulation and child working memory; at high levels of maternal cognitive support (1 SD above mean), there was a positive association.

In a separately tested model, the infant orienting/regulation by maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy interaction did not meet the inclusion criterion to predict child working memory. Mediational models were not considered given the lack of support in the correlational analyses (Tables 2 and 3) for any of the proposed models.

Inhibitory control

No infant temperament (orienting/regulation, extraversion/surgency) by maternal caregiving behaviors in infancy (cognitively supportive behaviors, emotionally supportive behaviors) interactions met the inclusion criterion to predict child inhibitory control in the multivariate model. The final regression model predicting inhibitory control showed significant main effects for maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy and for child gender (Table 5). Maternal smoking during pregnancy met a priori criteria for retention in the model as a potentially important covariate. The model accounted for 32% of the variance in child inhibitory control scores.

Table 5.

Final multiple regression analysis predicting child inhibitory control

| B | SE B | β | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy | .39 | .13 | .45 | .003 | |

| 2. Child gender | .51 | .22 | .29 | .021 | |

| 3. Maternal smoking during pregnancy | −.43 | .27 | −.21 | .110 | |

| R2 = 0.32 |

Relevant significant bivariate associations (Tables 2 and 3) supported testing the a priori hypothesis that the effect of maternal stress/trauma on child inhibitory control is mediated by maternal caregiving behaviors. A mediational model found a significant indirect effect of maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures through pregnancy on child inhibitory control through maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy (B = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.01, −0.15], p = .006), with nearly half (47%) of the total effect of maternal lifetime stress/trauma on child inhibitory control mediated through maternal emotionally supportive behaviors. There was no support in the correlational analyses for consideration of any other mediational models.

Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to explore the independent and interactive roles of several possible factors during pregnancy and the first three years of life in the development of early EF skills, specifically working memory and inhibitory control. Evidence indicates that brain development is especially rapid during this period and exquisitely vulnerable to environmental exposures shaping brain areas underlying EF (Buss et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2017; Spruijt et al., 2018). We focused on two types of exposures that the literature suggests have particular impact on early brain development: stress/trauma and maternal caregiving quality. In addition, we considered individual factors, namely the infant temperament domains of orienting/regulation and surgency/extraversion, given prior evidence that individual characteristics beginning in infancy are predictive of later EF skills and may influence the impact of environmental exposures on EF development. Overall, our findings suggest that working memory and inhibitory control are influenced by distinct processes in early life.

Analyses suggested that working memory in early childhood is influenced detrimentally by maternal stress/trauma exposures. Specifically, there was a moderately strong negative association between maternal lifetime exposure to stressors up through pregnancy and child working memory in the preschool period. Interestingly, neither maternal stress/trauma exposures during the child’s lifetime nor child direct exposures to potentially traumatic events were associated with child working memory. Moreover, the association between maternal lifetime exposures through pregnancy and child working memory remained significant even after accounting for infant temperament, maternal caregiving quality, and birth outcomes (gestational age). Notably, the significant stress exposure measure inquired about maternal lifetime exposures, including many stressors that only could have occurred during the mother’s childhood (e.g., child maltreatment). Together, these findings support, although do not confirm, the hypothesis that mothers’ stress/trauma exposures during sensitive periods of development (e.g., childhood) may lead to persistent disruptions in the functioning of maternal stress physiological regulation systems and maternal gestational biology, impacting fetal brain development (Buss et al., 2017). For example, data suggest that stress exposures disrupt HPA axis functioning and that the areas of the brain that subserve working memory (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus) are particularly sensitive to the effects of exposure to elevated cortisol levels (Buss et al., 2017). To date, the literature examining maternal stress exposures on offspring neurodevelopment has focused heavily on exposures that occurred during pregnancy and ignored exposures prior to the child’s conception. Further research is needed to determine the qualities of maternal exposures (e.g., type, timing) that have greatest impact on offspring brain development and the biological and behavioral mechanisms via which they exert effects.

The findings also suggest that child working memory is influenced by maternal caregiving behaviors, specifically behaviors supportive of cognitive development during infancy. Moreover, there was a significant interaction effect between maternal caregiving behaviors and infant temperament on child working memory consistent with the differential susceptibility hypothesis: Children with lower to average orienting/regulation traits appeared to show less sensitivity to the effects of maternal caregiving support on the development of working memory. Children with higher orienting/regulation traits appeared more responsive to maternal caregiving behaviors, with those exposed to low levels of cognitive support showing relatively diminished working memory scores and those exposed to high levels of cognitive support showing relatively enhanced working memory scores.

The processes associated with child inhibitory control were distinct from those associated with child working memory. First, whereas child working memory was associated with maternal cognitively supportive behaviors in infancy, child inhibitory control was associated with maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy. Unlike with child working memory, there was no significant interaction between infant temperament (orienting/regulation or extraversion/surgency) and maternal behaviors in infancy in predicting child inhibitory control. Although cognitive stimulation in the home during the preschool period was associated with child inhibitory control in correlational analyses, it was not significant in regression analyses. Together, these findings suggest that maternal emotionally supportive caregiving in infancy is a particularly strong predictor of child inhibitory control in the preschool period regardless of infant temperament. Furthermore, maternal lifetime exposure to stressors through pregnancy was found to exert effects on child inhibitory control through maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy. These results further support the conclusions that (a) maternal emotionally supportive behaviors in infancy may be central to supporting the development of child inhibitory control and (b) factors that reduce mothers’ abilities to behave in an emotionally sensitive manner (e.g., trauma history) may indirectly influence their children’s development of inhibitory control abilities through their impact on maternal behaviors.

The findings that child working memory was most strongly associated with maternal cognitive support in infancy and child inhibitory control with maternal emotional support in infancy are consistent with other studies that have found more cognitively supportive behaviors (e.g., verbal scaffolding) to be associated with working memory and more emotionally supportive caregiving behaviors (e.g., sensitivity, low intrusiveness) with child inhibitory control (Spruijt et al., 2018). They also align with other findings that maternal caregiving quality in infancy has strong associations with child EF in later development (Bernier et al., 2012; Bernier et al., 2010). Some have postulated that caregiving experiences during the first 2 years of life play a particularly critical role in later EF due to the rapid growth spurt and experience-dependent myelination and synaptic pruning that the frontal lobes undergo during this period (Bernier et al., 2012).

Notably, the association between working memory and inhibitory control in this sample was modest, consistent with prior findings and theories that different aspects of EF show different developmental trajectories and low correlations, particularly in early childhood (Frick et al., 2017; Garon et al., 2008). The finding that different models predicted working memory versus inhibitory control performance provides further evidence that these domains of EF may follow distinct developmental paths. Future studies should consider explicating the neural mechanisms underlying associations between various predictors and child EF skills across development. Such research may further inform our understanding of the processes by which EF skills become impaired as well as provide increased insight into the neural basis of EF skills. Currently, evidence suggests that working memory and inhibitory control involve somewhat overlapping brain regions. For example, studies implicate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and frontoparietal-temporal networks in working memory tasks (Gomez et al., 2018) and the anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, pre-supplementary motor area, and inferior parietal lobule during go/no-go tasks (Wiebe et al., 2012). The roles of different neural areas appear to change with maturation (e.g., for working memory, decreased role of hippocampus, increased role of prefrontal cortex with increasing age; Gomez et al., 2018). Newer theories are moving beyond attributing EF skills to specific neural structures and toward a focus on dynamic distributed neural networks (Bernstein & Waber, 2018). Such theories purport that environmental exposures influence EF skills through their impact on the establishment and functioning of neural networks rather than of distinct brain regions (Bernstein & Waber, 2018). Because these networks are highly malleable and dependent on early life experiences, early exposures may have particular impact on their construction and integration. Network differentiation, connectivity, and efficiency should increase through childhood and adolescence (Bernstein & Waber, 2018). Thus, assessing children at later ages and during critical developmental transitions will be crucial in determining whether the associations of early individual and environmental factors with EF abilities change as the underlying neural networks become more integrated and complex.

This study has several strengths. The sample was sociodemographically diverse in terms of child race/ethnicity, maternal education, family income, and parental relationship status. The longitudinal nature of the study provided for assessments at multiple developmental time points, including pregnancy, infancy, and the preschool period. Moreover, the assessments comprised maternal report measures, observations of maternal behaviors by trained raters, and direct assessment of child EF skills using well-validated age-appropriate tasks. This variety in measurement types reduces the likelihood of inflated associations due to shared method variance or maternal reporting biases. Furthermore, although the measures of maternal and child stress exposures relied on retrospective report, introducing possible error due to memory inaccuracies or reporting biases, prior data suggest that inaccuracies are in the direction of underestimating adverse experiences, which would lead to an underestimation of the magnitude of associations with child EF (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Also, the only stressor measure associated with child EF was assessed in pregnancy and thus unlikely to have been reported differentially by child characteristics. The use of maternal report of infant temperament leveraged the mother’s ability to observe her infant’s behavior over a range of contexts and was collected via the IBQ-R, which was designed to reduce the influence of reporting biases by inquiring about multiple examples of concrete infant behaviors for each domain rather than asking for abstract judgments (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003).

Limitations of the study should be noted. The relatively small sample size may have precluded detecting smaller yet important effects. A larger sample would allow for the testing of gender differences, as boys’ and girls’ neurodevelopment appears differentially impacted by early environmental exposures, including caregiving quality (Amicarelli et al., 2018; Mileva-Seitz et al., 2015; Plamondon et al., 2015; Van den Bergh et al., 2017). Although measures of maternal cognitive and emotional support were available during both infancy and childhood, they were assessed using different methodologies and focused on different behaviors, and thus may not have captured relevant maternal behaviors equivalently across ages. We did not examine the infant temperament domain of negative emotionality, which may influence EF development, particularly inhibitory or effortful control (Laurent et al., 2014; Rabinovitz et al., 2016). Future research with larger samples should consider the contributions of all domains of temperament, including their interactions with each other and with environmental factors, in predicting the maturation of EF skills across development. Prior work suggests that caregiving behaviors and children’s self-regulation skills may have bidirectional effects (Spruijt et al., 2018), which were not tested here. Future research should also consider the role of fathers/other caregivers, as the very limited work in this area suggests mothers and fathers play distinct, complementary roles in supporting child EF development (de Cock et al., 2017; Towe-Goodman et al., 2014). The role of genetic factors, which may influence several of the constructs assessed (Laurent et al., 2014), were not considered. Relatedly, maternal EF was not assessed and may contribute to both caregiving quality and child EF abilities (Mileva-Seitz et al., 2015; Suor et al., 2017; Zeytinoglu et al., 2017). A measure of general intellectual abilities was not available to include as a control variable; however, the different pattern of findings for the two EF domains analyzed and the relatively modest correlation between them decreases the likelihood that the results were driven by overarching cognitive capacities.

Although the sample was relatively diverse, it was skewed toward middle to high socioeconomic status. Studies should determine if these associations replicate in more economically disadvantaged populations, given documented associations between low socioeconomic status and EF deficits (Suor et al., 2017). Others have suggested that low socioeconomic status may exert its influence on child EF, at least in part, via reduced caregiving quality and greater stress exposure (Zeytinoglu et al., 2017). Thus, the current model may hold validity in a lower SES sample. The lack of an association between child trauma exposures and either working memory or inhibitory control may be due to low levels of exposure in this sample. Such associations may emerge in more trauma-exposed samples, where trauma type can be differentiated. There is evidence that exposures suggestive of deprivation of cognitive and social stimulation (e.g., neglect, low parental education) may be particularly harmful to neural structures and circuitry underlying EF (Sheridan et al., 2017). Finally, future studies may consider testing additional mechanisms that may contribute to associations between maternal stress exposures and child EF, such as prenatal stress reactivity (HPA axis, autonomic nervous system, oxidative stress, immune/inflammation) and prenatal and postnatal maternal psychopathology (Van den Bergh et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that two EF domains undergoing rapid development in the preschool period—working memory and inhibitory control—are influenced by different environmental exposures in early life. Specifically, although maternal caregiving behaviors in infancy had impact on both domains, cognitive support had more robust associations with working memory and emotional support with inhibitory control. Moreover, maternal caregiving behaviors interacted with infant temperament to predict child working memory, suggesting that children with particular temperament proclivities are more susceptible to both positive and negative influences of the caregiving environment as they relate to the development of working memory. On the other hand, results also suggest that higher quality maternal caregiving may enhance child inhibitory control regardless of temperament. Additionally, maternal lifetime stress/trauma exposures appear to influence both child working memory and inhibitory control, the former possibly via prenatal programming processes and the latter via maternal caregiving quality. Together, these findings may inform efforts to maximize the development of child EF abilities and, consequently, enhance long-term outcomes across a range of domains of functioning.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute under Grant R01HL095606; the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under Grant R01HD082078; the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences under Grant P30ES023515; the Boston Children’s Hospital’s Clinical and Translational Research Executive Committee, and the Program for Behavioral Science in the Department of Psychiatry at Boston Children’s Hospital. This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) UL1TR001433. None of the funding agencies had any role in the study design, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of any granting agency. We are grateful for the study families whose generous donation of time made this project possible.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amicarelli AR, Kotelnikova Y, Smith HJ, Kryski KR, & Hayden EP (2018). Parenting differentially influences the development of boys’ and girls’ inhibitory control. The British journal of developmental psychology. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & Pluess M (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull, 135(6), 885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Deschenes M, & Matte-Gagne C (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: a closer look at the caregiving environment. Dev Sci, 15(1), 12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, & Whipple N (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Dev, 81(1), 326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JH, & Waber DP (2018). Executive Capacities from a Developmental Perspective In Meltzer L (Ed.), Executive Function in Education: From Theory to Practice (2nd ed, pp. 57–81). New York, NY: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson JL, & Emde RN (1994). Maternal sensitivity in the second year: gender-based relations in the dyadic balance of control. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 64(1), 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH (1989). The use of the HOME Inventory in longitudinal studies of child development In K. N Bornstein MH (Ed.), Stability and Continuity in Mental Development: Behavioral and Biological Perspectives (pp. 191–215). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR (2005). Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. J Trauma Stress, 18(1), 53–62. doi: 10.1002/jts.20007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush NR, Jones-Mason K, Coccia M, Caron Z, Alkon A, Thomas M, … Epel ES. (2017). Effects of pre- and postnatal maternal stress on infant temperament and autonomic nervous system reactivity and regulation in a diverse, low-income population. Dev Psychopathol, 29(5), 1553–1571. doi: 10.1017/s0954579417001237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, Toepfer P, Fair DA, Simhan HN, … Wadhwa PD. (2017). Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal brain development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 56(5), 373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Trainor RJ, Orendi JL, Schubert AB, Nystrom LE, Giedd JN, … Rapoport JL. (1997). A developmental functional MRI study of prefrontal activation during performance of a Go-No-Go task. J Cogn Neurosci, 9(6), 835–847. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, Lu S, Archer M, & Wang Z (2017). Quality of maternal parenting of 9-month-old infants predicts executive function performance at 2 and 3 years of age. Front Psychol, 8, 2293. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier N, James TD, Wiebe SA, Nelson JM, & Espy KA (2014). Contribution of reactive and proactive control to children’s working memory performance: Insight from item recall durations in response sequence planning. Dev Psychol, 50(7), 1999–2008. doi: 10.1037/a0036644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CA, Nelson JM, Garza J, Sheffield TD, Wiebe SA, & Espy KA (2014). Gaining control: changing relations between executive control and processing speed and their relevance for mathematics achievement over course of the preschool period. Front Psychol, 5, 107. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R (1999). The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: A factorial validity study. Educ Psychol Meas, 59(5), 821–846. doi: 10.1177/00131649921970161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conway A, & Stifter CA (2012). Longitudinal antecedents of executive function in preschoolers. Child Dev, 83(3), 1022–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01756.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock ESA, Henrichs J, Klimstra TA, Janneke BMMA, Vreeswijk C, Meeus WHJ, & van Bakel HJA (2017). Longitudinal associations between parental bonding, parenting stress, and executive functioning in toddlerhood. J Child Fam Stud, 26(6), 1723–1733. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0679-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlow MB, Devick KL, Brunst KJ, Lipton LR, Coull BA, & Wright RJ (2017). Maternal lifetime trauma exposure, prenatal cortisol, and infant negative affectivity. Infancy, 22(4), 492–513. doi: 10.1111/infa.12176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlow MB, Kullowatz A, Staudenmayer J, Spasojevic J, Ritz T, & Wright RJ (2009). Associations of maternal lifetime trauma and perinatal traumatic stress symptoms with infant cardiorespiratory reactivity to psychological challenge. Psychosom Med, 71(6), 607–614. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ad1c8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick MA, Forslund T, Fransson M, Johansson M, Bohlin G, & Brocki KC (2017). The role of sustained attention, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament in the development of early self-regulation. Br J Psychol, 109(2), 277–298. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon N, Bryson SE, & Smith IM (2008). Executive function in preschoolers: A review using an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 31–60. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, & Rothbart MK (2003). Studying infant temperament via a revision of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behav Dev, 7, 517–522. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh Ippen C, Ford JD, Racusin R, Acker M, Bosquet M, Rogers K, … Edwards J. (2002). Traumatic Events Screening Inventory-Parent Report revised. San Francisco, CA: The Child Trauma Research Project of the Early Trauma Treatment Network & the National Center for PTSD Dartmouth Child Trauma Research Group. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez CM, Barriga-Paulino CI, Rodriguez-Martinez EI, Rojas-Benjumea MA, Arjona A, & Gomez-Gonzalez J (2018). The neurophysiology of working memory development: from childhood to adolescence and young adulthood. Rev Neurosci, 29(3), 261–282. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, & Rutter M (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishiyama MM, Boyce WT, Jimenez AM, Perry LM, & Knight RT (2009). Socioeconomic disparities affect prefrontal function in children. J Cogn Neurosci, 21(6), 1106–1115. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Fisher PA, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2014). Stress system development from age 4.5 to 6: Family environment predictors and adjustment implications of HPA activity stability versus change. Dev Psychobiol,56(3), 340–354. doi: 10.1002/dev.21103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, DeGarmo DS, Bridgett DJ, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Harold GT, … Reiss D, (2013). Using an adoption design to separate genetic, prenatal, and temperament influences on toddler executive function. Dev Psychol, 49(6), 1045–1057. doi: 10.1037/a0029390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sulik MJ, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Lemery-Chalfant K, Stover DA, & Verrelli BC (2016). Predicting childhood effortful control from interactions between early parenting quality and children’s dopamine transporter gene haplotypes. Dev Psychopathol, 28(1), 199–212. doi: 10.1017/s0954579415000383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Crnic KA, Luecken LJ, & Gonzales NA (2014). Maternal prenatal stress and infant regulatory capacity in Mexican Americans. Infant Behav Dev, 37(4), 571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipina S, Martelli M, Vuelta B, & Colombo J (2005). Performance on the A-not-B task of Argentinian infants from unsatisfied and satisfied basic needs homes. Interam J Psychol, 39, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton LR, Brunst KJ, Kannan S, Ni YM, Ganguri HB, Wright RJ, & Bosquet Enlow M (2017). Associations among prenatal stress, maternal antioxidant intakes in pregnancy, and child temperament at age 30 months. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 8(6), 638–648. doi: 10.1017/s2040174417000411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, & Heim C (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan N, & Creelman C (2005). Detection theory: A user’s guide. 2 New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McHugo GJ, Caspi Y, Kammerer N, Mazelis R, Jackson EW, Russell L, … Kimerling R. (2005). The assessment of trauma history in women with co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders and a history of interpersonal violence. J Behav Health Serv Res, 32(2), 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileva-Seitz VR, Ghassabian A, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van den Brink JD, Linting M, Jaddoe VW, … van IMH (2015). Are boys more sensitive to sensitivity? Parenting and executive function in preschoolers. J Exp Child Psychol, 130, 193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehler E, Biringen Z, & Poustka L (2007). Emotional availability in a sample of mothers with a history of abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 624–628. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi Y, & Shinohara I (2018). Effect of the COMT Val158Met genotype on lateral prefrontal activations in young children. Dev Sci, 21(5), e12649. doi: 10.1111/desc.12649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, & Bosquet M (2000). Neurobiology of fetal and infant development: implications for infant mental health In Zeanah CH Jr (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (pp. 37–59). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1999). Child care and mother-child interaction in the first three years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1399–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parade SH, & Leerkes EM (2008). The reliability and validity of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised. Infant Behav Dev, 31(4), 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, & Egeland B (1994). Predictors of instability in children’s mental test performance at 24, 48, and 96 months. Intelligence 18, 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett KE, Kasza K, Biesecker G, Wright RJ, & Wakschlag LS (2009). Women who remember, women who do not: a methodological study of maternal recall of smoking in pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res, 11(10), 1166–1174. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plamondon A, Akbari E, Atkinson L, Steiner M, Meaney MJ, & Fleming AS (2015). Spatial working memory and attention skills are predicted by maternal stress during pregnancy. Early Hum Dev, 91(1), 23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess M, & Belsky J (2013). Vantage sensitivity: individual differences in response to positive experiences. Psychol Bull, 139(4), 901–916. doi: 10.1037/a0030196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitz BB, O’Neill S, Rajendran K, & Halperin JM (2016). Temperament, executive control, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across early development. J Abnorm Psychol, 125(2), 196–206. doi: 10.1037/abn0000093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz SJ, & Davies PL (2004). Charting the maturation of the frontal lobe: An electrophysiological strategy. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 116–133. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00283-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Peverill M, Finn AS, & McLaughlin KA (2017). Dimensions of childhood adversity have distinct associations with neural systems underlying executive functioning. Dev Psychopathol, 29(5), 1777–1794. doi: 10.1017/s0954579417001390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky LS, Carter A, & Marakovitz S (2004). Parent Child Interaction Rating Scales (PCIRS). [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, & Gaertner BM (2007). Measures of effortful regulation for young children. Infant Ment Health J, 28(6), 606–626. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt AM, Dekker MC, Ziermans TB, & Swaab H (2018). Attentional control and executive functioning in school-aged children: Linking self-regulation and parenting strategies. J Exp Child Psychol, 166, 340–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suor JH, Sturge-Apple ML, & Skibo MA (2017). Breaking cycles of risk: The mitigating role of maternal working memory in associations among socioeconomic status, early caregiving, and children’s working memory. Dev Psychopathol, 29(4), 1133–1147. doi: 10.1017/s095457941600119x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda C, Rodriguez V, Shannon J, Hannibal B, Ahuja P, & Spellmann M (2002). Caregiver-Child Affect, Responsiveness, and Engagement Scale (C-CARES) Fourteen-Month Version. New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Towe-Goodman NR, Willoughby M, Blair C, Gustafsson HC, Mills-Koonce WR, & Cox MJ (2014). Fathers’ sensitive parenting and the development of early executive functioning. J Fam Psychol, 28(6), 867–876. doi: 10.1037/a0038128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BRH, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, Braeken M, de Rooij SR, Entringer S, … Schwab M. (2017). Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Clark CAC, De Jong DM, Chevalier N, Espy KA, & Wakschlag L (2015). Prenatal tobacco exposure and self-regulation in early childhood: Implications for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Sheffield T, Nelson JM, Clark CA, Chevalier N, & Espy KA (2011). The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. J Exp Child Psychol, 108(3), 436–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Sheffield TD, & Espy KA (2012). Separating the fish from the sharks: a longitudinal study of preschool response inhibition. Child Dev, 83(4), 1245–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01765.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J, & Kimerling R (1997). Gender issues in assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder In Wilson J & Keane T (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 192–238). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoglu S, Calkins SD, Swingler MM, & Leerkes EM (2017). Pathways from maternal effortful control to child self-regulation: The role of maternal emotional support. J Fam Psychol, 31(2), 170–180. doi: 10.1037/fam0000271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P, Sun MS, Hao JH, Chen YJ, Jiang XM, Tao RX, … Tao FB. (2014). Does prenatal maternal stress impair cognitive development and alter temperament characteristics in toddlers with healthy birth outcomes? Dev Med Child Neurol, 56(3), 283–289. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]