Abstract

This prospective cohort pilot study sought to characterize the short-term temporal trajectory of, and risk factors for, body image disturbance (BID) in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). Most patients were male (35/56), had oral cavity cancer (33/56), and underwent microvascular reconstruction (37/56). Using the Body Image Scale (BIS), a validated patient-reported outcome measure of BID, the prevalence of BID (BIS ≥10) increased from 11% preoperatively to 25% at 1 month postoperatively and 27% at 3 months posttreatment (P < .001 and P = .0014 relative to baseline, respectively). Risk factors for BID included female sex (odds ratio [OR], 4.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3–19.8), pT 3 to 4 tumors (OR, 8.9; 95% CI, 2.0–63.7), and more severe baseline shame and stigma (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01–1.13), depression (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06–1.51), and social isolation (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01–1.49). The prevalence and severity of BID increase immediately posttreatment. Demographic, oncologic, and psychosocial characteristics identify high-risk patients for targeted interventions.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, body image, patient reported outcomes, survivorship, disfigurement, quality of life

Head and neck cancer (HNC) arises in cosmetically and functionally critical areas, resulting in life-altering disfigurement, difficulty swallowing, and challenges speaking.1,2 As a result, HNC survivors express high rates of body image disturbance (BID), a multidimensional construct characterized by a displeasing self-perceived change in appearance and/or function.3–6 Although BID is associated with significant psychosocial morbidity and decreased quality of life,7,8 significant gaps about its epidemiology remain. This knowledge gap about the temporal trajectory of, and risk factors for, BID in surgically managed HNC patients7,8 precludes delivery of optimally timed, preventative, and therapeutic interventions targeted to high-risk patients. This pilot study aims to test the hypotheses that (1) BID increases in prevalence and severity in the short term following treatment, and (2) demographic, oncologic, and psychosocial characteristics identify a high-risk subset of patients.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. Included patients were ≥18 years old with surgically treated HNC. Participants were recruited from a multidisciplinary HNC clinic at a single academic medical center using a purposive enrollment strategy to stratify across hypothesized risk factors. Seventy patients enrolled; mortality (n = 7) and lost to follow-up (n = 7) resulted in a final cohort of 56 patients.

Sociodemographic,9 comorbidity,10 and oncologic data were collected. Psychological, emotional, social, and functional characteristics were assessed with the following validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): Shame and Stigma Scale,11 PROMIS-SF v1.0–Depression 4a and Anxiety 4a,12 PROMIS-SF v2.0–Social Isolation and Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities 4a and 4a,13 and Performance Status Scale–Head and Neck.14 The primary outcome measure was the Body Image Scale (BIS), a validated PROM of BID in oncology patients4 that has been widely used to study BID in HNC5,6,15–18; BIS scores of ≥10 are considered clinically significant.19,20 Data were collected at enrollment, 1 month postoperatively, and 3 months after treatment completion (surgery or adjuvant therapy).

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.2.2. Summary statistics for demographics, clinical measures, and PROMs included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous measures. Changes in BIS scores over time were analyzed using a Wilcoxon sign-rank test. Associations between demographics, clinical characteristics, psychosocial and head and neck function, and BID (BIS score ≥10 vs <10) were summarized using odds ratios (ORs) based on fitted simple logistic regression models. Models were adjusted for pretreatment BIS scores (treated as a continuous variable) using multiple logistic regression models. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for ORs were constructed using a profile likelihood approach to improve interval coverage.21 Summed scores for all PROMs were treated as missing if any individual question for that instrument was missing.

Results

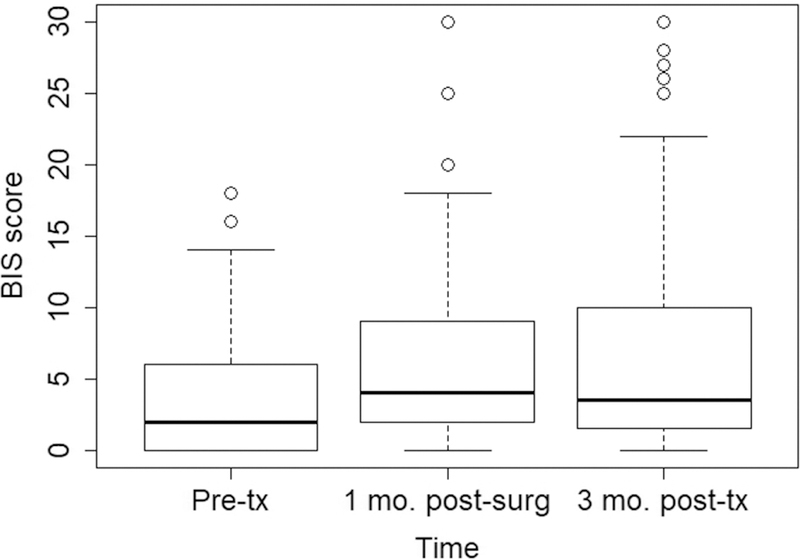

Table 1 shows the cohort characteristics. The prevalence of BID (BIS ≥10) increased from 11% (6/53) preoperatively to 25% (13/53) at 1 month after surgery and 27% (14/52) at 3 months after the completion of treatment (P < .001 and P = .0014 for values relative to baseline, respectively). The median pretreatment BIS was 2 (IQR, 0–6), increasing to 4 (IQR, 2–9) at 1 month postoperatively, then 3.5 (IQR, 1.75–10) 3 months after treatment completion (Figure 1). Increases in BIS scores of more than 5 points occurred in 22% of patients (11/51) from baseline to 1 month postoperatively and 23% of patients (11/49) from baseline to 3 months posttreatment. Relative to baseline, 63% of patients (32/51) had higher BIS scores at 1 month postoperatively and 57% (28/49) had higher BIS scores at 3 months posttreatment.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Clinical, Oncologic, and Psychosocial Characteristics of the Study Cohort (N = 56).

| Characteristic | No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 61 (51.75–71) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Female | 21 (38) |

| Male | 35 (63) |

| Race, No. (%) | |

| White | 48 (86) |

| African American | 7 (13) |

| Other | 1 (2) |

| Insurance, No. (%) | |

| Private | 25 (45) |

| Medicare | 24 (43) |

| Medicaid/self-pay/other | 7 (13) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |

| Married/current partner | 33 (59) |

| Single/separated/divorced/widowed | 23 (41) |

| Living situation, No. (%)b | |

| Spouse/partner | 36 (64) |

| Self | 9 (16) |

| Parents/children/friends/other | 16 (28) |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | |

| High school or less | 20 (36) |

| College attendee or graduate | 27 (48) |

| Graduate school | 9 (16) |

| Occupational status, No. (%) | |

| Employedc | 15 (27) |

| Not employedd | 18 (32) |

| Retired | 23 (41) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), No. (%) | |

| Underweight | 2 (4) |

| Normal weight | 19 (34) |

| Overweight/obese | 35 (63) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score, No. (%) | |

| 0 | 33 (59) |

| 1 | 9 (16) |

| ≥2 | 14 (25) |

| Tumor location and histology, No. (%) | |

| Oral cavity SCC | 33 (59) |

| Oropharynx SCC/SCC of unknown primary | 8 (14) |

| Larynx SCC | 4 (7) |

| Facial cutaneous malignancy | 11 (20) |

| p16 status (oropharynx cases only), No. (%) | |

| p16 negative | 3 (38) |

| p16 positive | 5 (63) |

| AJCC pathologic T classification, No. (%) | |

| 0–2 | 30 (54) |

| 3–4b | 26 (46) |

| Ablative surgery, No. (%)b | |

| Mandibulectomy | 11 (20) |

| Glossectomy | 34 (61) |

| Maxillectomy | 4 (7) |

| Radical tonsillectomy/pharyngectomy | 4 (7) |

| Total laryngectomy | 2 (4) |

| Partial laryngectomy | 2 (4) |

| Skin/soft tissue resection | 14 (25) |

| Parotidectomy | 3 (5) |

| Neck dissection | 49 (88) |

| Other | 3 (5) |

| Reconstructive surgery, No. (%) | |

| None or dermal substitute | 15 (27) |

| Regional flap | 4 (7) |

| Microvascular free flap | 37 (66) |

| Osseous microvascular free flap reconstruction, No. (%) | |

| No | 46 (82) |

| Yes | 10 (18) |

| Adjuvant therapy, No. (%) | |

| None | 22 (39) |

| Radiation | 20 (36) |

| Chemoradiation | 14 (25) |

| Median (IQR) | |

| Shame and Stigma Scale | 14 (10–21.75) |

| PROMIS Anxiety–SF 4a | 10 (5.5–12.5) |

| PROMIS Depression–SF 4a | 6 (4–9.5) |

| PROMIS Satisfaction with Social | 16 (11.75–20) |

| Roles and Activities–SF 4a | |

| PROMIS Social Isolation–SF 4a | 4 (4–8) |

| Performance Status Scale–Head and | 92 (69–100) |

| Neck, average score across subscales | |

| Normalcy of Diet | 100 (50–100) |

| Public Eating | 100 (75–100) |

| Understandability of speech | 100 (75–100) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; IQR, interquartile range; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Percentages may not sum to 1 due to rounding.

Number sums to more than 56 as patients may belong to more than 1 category concurrently.

Includes full-time employment and part-time employment.

Includes unemployed, work disability, homemaker.

Figure 1.

Short-term temporal trajectory of body image disturbance in patients with surgically treated head and neck cancer. Box-and-whisker plot showing the severity of body image disturbance (as determined by Body Image Scale [BIS] scores) prior to treatment, 1 month after surgery, and 3 months after completion of treatment.

The logistic regression analysis demonstrating the relationship between demographic, clinical, and psychosocial risk factors and BID (BIS ≥10) at 1 month postoperatively and 3 months after treatment is shown in Table 2. Risk factors for BID included female sex, pT 3 to 4 tumors, and higher baseline levels of shame and stigma, depression, and social isolation.

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Body Image Disturbance (Body Image Scale Score ≥10) at 1 Month Postoperatively and 3 Months Posttreatment.a

| BIS Score ≥10 at 1 Month Postoperatively |

BIS Score ≥10 at 3 Months Posttreatment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | nb | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | nb | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjustedc OR (95% CI) |

| Sex | 51 | 49 | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 2.25 (0.59–8.7) | 2.20 (0.48–10.6) | 4.8 (1.3–19.8) | 4.3 (0.88–23.9) | ||

| Age, y | 51 | 49 | ||||

| 40+ | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| <40 | 7.6 (0.66–173.7) | 4.9 (0.24–142.7) | 6.4 (0.56–144.9) | 3.9 (0.15–124.4) | ||

| Marital status | 51 | 49 | ||||

| Married/current partner | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Single, divorced, separated, widowed | 0.43 (0.09–1.7) | 0.32 (0.04–1.6) | 0.38 (0.07–1.5) | 0.23 (0.03–1.3) | ||

| BMI | 51 | 49 | ||||

| Overweight or obese | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Underweight or normal | 1.6 (0.41–6.1). | 1.9 (0.39–9.5) | 0.68 (0.13–2.8) | 0.99 (0.16–5.1) | ||

| AJCC Pathologic T Classification | 51 | 49 | ||||

| 0, 1, or 2 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 3 or 4a | 8.9 (2.0–63.7) | 19.6 (2.8–352.3) | 3.15 (0.85–13.5) | 3.8 (0.8–24.2) | ||

| Reconstructive surgery | 51 | 49 | ||||

| None or dermal | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Substitute rotational flap | 4.7 (0.16–144.5) | 11.1 (0.25–832.8) | 1.8 (0.07–27.2) | 1.3 (0.04–23.2) | ||

| Microvascular free flap | 6.4 (1.0–123.3) | 21.5 (1.7–1341.8) | 2.5 (0.54–18.1) | 2.3 (0.39–20.8) | ||

| Osseous microvascular free flap reconstruction | 51 | 49 | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.9 (0.50–15.7) | 22.3 (2.4–304.5) | 1.1 (0.15–6.1) | 4.7 (0.49–42.4) | ||

| Pretreatment Shame and Stigma Scale | 50 | 1.06 (1.01–1.13) | 1.06 (0.19–6.07) | 48 | 1.11 (1.04–1.21) | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) |

| Pretreatment PROMIS Emotional Distress–Anxiety SF4a | 50 | 1.15 (0.98–1.39) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 48 | 1.19 (1.00–1.46) | 0.98 (0.75–1.26) |

| Pretreatment PROMIS Emotional Distress–Depression SF4a | 50 | 1.25 (1.06–1.51) | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | 48 | 1.13 (0.96–1.34) | 0.80 (0.54–1.07) |

| Pretreatment PROMIS Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities SF4a | 51 | 0.88 (0.77–0.98) | 0.94 (0.82–1.10) | 49 | 0.90 (0.79–1.01) | 0.98 (0.84–1.15) |

| Pretreatment PROMIS Social Isolation SF4a | 51 | 1.21 (1.01–1.49) | 1.05 (0.79–1.34) | 49 | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 0.88 (0.58–1.18) |

| Pretreatment Performance Status– Head and Neck, average across subscales | 50 | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 1.00 (0.97–1.05) | 48 | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) |

| Performance Status Scale–Head and Neck, Normalcy of Diet | 50 | 48 | ||||

| 90, 100 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 0, 10, …, 80 | 1.09 (0.21–4.65) | 0.79 (0.11–4.31) | 2.11 (0.52–8.34) | 2.75 (0.46–17.14) | ||

| Performance Status Scale–Head and Neck, Public Eating | 50 | 48 | ||||

| 75, 100 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 0, 25, 50 | 2.06 (0.37–9.81) | 1.00 (0.12–6.14) | 1.45 (0.27–6.67) | 0.86 (0.10–5.35) | ||

| Performance Status Scale–Head and Neck, Understandability of Speech | 51 | 49 | ||||

| 75, 100 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 0, 25, 50 | 2.27 (0.40–11.18) | 1.22 (0.12–8.35) | 2.76 (0.58–12.73) | 1.78 (0.23–11.49) | ||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BIS, Body Image Scale; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Bold values are statistically significant.

N < 56 for certain patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs; PROMs were treated as missing if any individual question for that instrument was missing).

Adjusted for pretreatment Body Image Scale scores (treated as a continuous variable) using multiple logistic regression models.

Discussion

As the importance of delivering patient-centered HNC care grows, it is imperative to move beyond clinician ratings of disfigurement22,23 to patient-reported assessments of how HNC affects body image.24,25 A landmark study by Krouse et al26 analyzing adaptation following HNC treatment analyzed longitudinal changes in BID, although it employed a nonvalidated outcome measure. Other studies of BID in surgically-treated HNC patients have been cross-sectional in nature.5,15,27 Our prospective cohort design using a validated PROM of BID thus represents a methodological improvement over prior research. Using this rigorous approach, we expand upon prior work5,6,27–30 to provide preliminary data that demographic (female sex), oncologic (T-stage, free flap), and baseline psychological, emotional, and social characteristics identify a subset of patients at high risk for BID.

This prospective cohort study using a validated PROM was methodologically sound and conducted with low levels of missing data. Limitations include the single-institution design and lack of long-term follow-up, which should be addressed in future work. The small sample size, which was not determined a priori to measure prespecified changes in BID, limits power to detect small but clinically significant differences. We attempted to maintain high external validity by employing a purposive enrollment strategy and creating a cohort representative of a standard academic HNC practice. However, the heterogeneous inclusion criteria limit internal validity relative to a study with narrowly defined inclusion criteria (eg, T4 oral cavity cancer undergoing free flap reconstruction).

In this prospective cohort pilot study of surgically treated patients with HNC, the prevalence and severity of BID increased at 1 month postoperatively and 3 months posttreatment relative to pretreatment. Demographic, oncologic, and psychosocial characteristics identified high-risk patients. These data will inform the delivery of optimally timed, targeted, preventative, and therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: American Cancer Society grant ACS IRG-16–185-17 to Evan Graboyes, National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA138313 to the Biostatistics Shared Resource of the Hollings Cancer Center. Neither funding organization had no role in the design and conduct; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or writing or approval of the manuscript.

Sponsorships: None.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Jansen F, Snyder CF, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Identifying cutoff scores for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the head and neck cancer-specific module EORTC QLQ-H&N35 representing unmet supportive care needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2016;38(suppl 1):E1493–E1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: a review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;62:251–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhoten BA. Body image disturbance in adults treated for cancer—a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teo I, Fronczyk KM, Guindani M, et al. Salient body image concerns of patients with cancer undergoing head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck 2016;38:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fingeret MC, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Weston J, Nipomnick S, Weber R. The nature and extent of body image concerns among surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology 2012;21:836–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Reece GP, Gillenwater AM, Gritz ER. Multidimensional analysis of body image concerns among newly diagnosed patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck 2010;32:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol 2013;49:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Goettsch K. Body image: a critical psychosocial issue for patients with head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2015;17:422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kissane DW, Patel SG, Baser RE, et al. Preliminary evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Shame and Stigma Scale in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2013;35:172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment 2011;18:263–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn EA, DeWalt DA, Bode RK, et al. New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol 2014;33:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer 1990;66:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Branch L, Feuz C, McQuestion M. An investigation into body image concerns in the head and neck cancer population receiving radiation or chemoradiation using the Body Image Scale: a pilot study. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci 2017;48:169–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SC, Huang BS, Lin CY, et al. Psychosocial effects of a skin camouflage program in female survivors with head and neck cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2017;26:1376–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SC, Huang CY, Huang BS, et al. Factors associated with healthcare professional’s rating of disfigurement and self-perceived body image in female patients with head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis MA, Sterba KR, Brennan EA, Maurer S, Hill EG, Day TA, Graboyes EM. A systematic review of patient reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer [published online ahead of print February 12, 2019]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg doi: 10.1177/0194599819829018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopwood P, Lee A, Shenton A, et al. Clinical follow-up after bilateral risk reducing (‘prophylactic’) mastectomy: mental health and body image outcomes. Psychooncology 2000;9:462–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman KA, Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, et al. Reducing body image-related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: results from the My Changed Body randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1930–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Rodin GM, Gullane PJ. Reliability and validity of an observer-rated disfigurement scale for head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck 2000;22: 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dropkin MJ, Malgady RG, Scott DW, Oberst MT, Strong EW. Scaling of disfigurement and dysfunction in postoperative head and neck patients. Head Neck Surg 1983;6:559–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djan R, Penington A. A systematic review of questionnaires to measure the impact of appearance on quality of life for head and neck cancer patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013; 66:647–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albornoz CR, Pusic AL, Reavey P, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 2013;40:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krouse JH, Krouse HJ, Fabian RL. Adaptation to surgery for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 1989;99:789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke SA, Newell R, Thompson A, Harcourt D, Lindenmeyer A. Appearance concerns and psychosocial adjustment following head and neck cancer: a cross-sectional study and nine-month follow-up. Psychol Health Med 2014; 19:505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SC, Yu PJ, Hong MY, et al. Communication dysfunction, body image, and symptom severity in postoperative head and neck cancer patients: factors associated with the amount of speaking after treatment. Support Care Cancer 2015;23: 2375–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katre C, Johnson IA, Humphris GM, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Assessment of problems with appearance, following surgery for oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer using the University of Washington appearance domain and the Derriford appearance scale. Oral Oncol 2008;44:927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhoten BA, Deng J, Dietrich MS, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image and depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: an important relationship. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:3053–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]