Abstract

Objective:

This meta-analysis synthesized the literature regarding the effect of therapist experience on internalizing client outcomes to evaluate the utility of lay providers in delivering treatment and to inform therapist training.

Method:

The analysis included 22 studies, contributing 208 effect sizes. Study and client characteristics were coded to examine moderators. We conducted subgroup meta-analyses examining the relationship of therapist experience across a diverse set of internalizing client outcomes.

Results:

Results demonstrated a small, but significant relationship between therapist experience and internalizing client outcomes. There was no relationship between therapist experience and outcomes in clients with primary anxiety disorders. In samples of clients with primary depressive disorders and in samples of clients with mixed internalizing disorders, there was a significant relationship between experience and outcomes. The relationship between therapist experience and outcomes was stronger when clients were randomized to therapists, treatment was not manualized, and for measures of client satisfaction and “other” outcomes (e.g., dropout).

Conclusions:

It appears that therapist experience may matter for internalizing clients under certain circumstances, but this relationship is modest. Continuing methodological concerns in the literature are noted, as well as recommendations to address these concerns.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, psychotherapist training/supervision/development, internalizing, meta-analysis

Internalizing disorders are characterized by anxiety, fear, shyness, low self-esteem, sadness, and/or depression (Ollendick & King, 1994), are the most common group of mental illnesses worldwide, affecting 20–30% of people in their lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2007), often leading to a significant decrease in functioning (e.g., Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2007; van Ameringen, Mancini, & Farvolden, 2003). Poor outcomes are more likely to occur without treatment, and fewer than half of individuals with internalizing disorders receive services (Kessler, Demler, et al., 2005; Meri-kangas et al., 2011; Wu et al., 1999).

One barrier to clients accessing treatment is a shortage of therapists (Fricchione et al., 2012; Kessler, Demler, et al., 2005; Saraceno et al., 2007). An approach to address this shortage is task shifting, or having services delivered by laypersons or bachelor’s-level providers who receive supervision by highly trained professionals (Fulton et al., 2011). Many task-shifting efforts focused on implementing manualized evidence-based practices have taken place in low-and middle-income countries, with promising results (Chibanda et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2013; Petersen, Hancock, Bhana, & Govender, 2014). Yet, task shifting is often met with resistance in more developed countries due to concerns that it will decrease the quality of care (Buttorff et al., 2012; Hoeft, Fortney, Patel, & Unützer, 2018). For task shifting to be confidently justified, more evidence is needed that less experienced therapists can deliver treatments with comparable client outcomes to more experienced therapists.

Overall, syntheses of the research literature render equivocal findings on the impact of therapist experience on outcomes (e.g., Franklin, Abramowitz, Furr, Kalsy, & Riggs, 2003). The mixed nature of the evidence may be due, in part, to the lack of a shared or agreed upon definition of “therapist experience.” Therapist experience has been operationalized to differentiate between “professionals” and “paraprofessionals” (i.e., individuals without a professional degree and/or no therapy experience), as well as different degree types, status in training program, and time practicing therapy (Bright, Baker, & Nei-meyer, 1999; Budge et al., 2013; Propst, Paris, & Rosberger, 1994). Definitional inconsistencies hinder comparisons across studies, making it difficult to discern which therapists attain better client outcomes. Moreover, there is a growing body of literature exploring the impact of therapist experience within specific populations (Podell et al., 2013) or utilizing fine-grained indices of therapist experience, such as the number of times using a treatment manual (Huppert et al., 2001; Podell et al., 2013). The potential contribution of therapist variability on client outcomes is acknowledged (e.g., Goldberg, Hoyt, Nissen-Lie, Nielsen, & Wampold, 2016; Roos & Werbart, 2013), yet the sources of variability remain largely unknown. With a high demand for therapists, emerging efforts to train laypersons to meet this need, and the high prevalence ofinternaliz-ing disorders worldwide, now is an excellent time for an updated synthesis of the literature to re-examine the impact of therapist experience on internalizing client outcomes.

One way to examine this question is through metaanalysis. Meta-analyses are thought to be more transparent, more replicable, and deliver a more interpretable message than review papers and individual studies (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Several meta-analyses including clients with internalizing and externalizing disorders have examined associations between therapist experience and client outcomes (Berman & Norton, 1985; Durlak, 1979; Hattie, Sharpley, & Rogers, 1984; Stein & Lambert, 1984, 1995; Weisz, Weiss, Alicke, & Klotz, 1987; Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, & Morton, 1995). These meta-analyses found conflicting results, some finding an overall positive relationship between experience and outcomes (Stein & Lambert, 1995), some finding no relationship (Berman & Norton, 1985; Stein & Lambert, 1984; Weisz et al., 1987), and some finding a negative relationship (Durlak, 1979; Hattie et al., 1984; Weisz et al., 1995).

One way to understand this heterogeneity is that the relationship between experience and outcome may vary as a function of client, clinician, treatment, or methodological factors. Stein and Lambert (1995) found a positive relationship between therapist experience and client satisfaction with treatment and change on psychological self-report measures (e.g., the Beck Depression Inventory; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), but not for measures of clients’ perceived helpfulness of treatment or personality measures. They also found a positive relationship between therapist experience and outcomes when outcomes were rated by independent evaluators (IEs), but not clients or therapists; they theorized that IEs might be better able to detect subtle outcome differences. The authors proposed other potential moderators that they were not able to examine in their dataset, including randomization of clients to therapists (as more severe clients may be assigned to more experienced therapists without randomization), inclusion of clients with comorbid disorders (who may be difficult for inexperienced therapists to treat), and provision of equal supervision to all therapists (versus providing more supervision to the less experienced therapists). Weisz and colleagues (1987, 1995) found that youth with internalizing disorders had better outcomes when treated by professional therapists than by graduate students or paraprofessionals, but there was no effect of experience in externalizing samples.

In sum, the overall effect of therapist experience on client outcomes is inconsistent across studies, and no two meta-analyses have examined the same moderators of therapist experience and client outcomes. It is possible that a clearer picture would be obtained in a focused examination within a narrower diagnostic group (Beutler, 1997; Michael, Huelsman, & Crowley, 2005) while examining a range of potential moderators.

Two previous meta-analyses focused on the effect of therapist experience on outcomes in clients with depressive disorders (Johnsen & Friborg, 2015; Michael et al., 2005). Michael et al. (2005) investigated this question in treatment studies for youth depression, finding that professional therapists (i.e., doctoral or master’s level therapists) and graduate students obtained equivalent outcomes; the only moderator they examined was client age, and they found no differences in effects by age group. In a meta-analysis focused on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression, Johnsen and Friborg (2015) found that professional psychologists achieved better outcomes than graduate students but did not examine moderators. Two recent meta-analyses focused on the role of therapist experience in dropout in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Ong, Clyde, Bluett, Levin, & Twohig, 2016) and generalized anxiety disorder (Gersh et al., 2017) found no relationship.

The time is ripe for a new meta-analysis on the relationship between experience and outcomes that includes studies focused on the broad spectrum of internalizing symptoms across adult and youth samples. The current study built upon previous meta-analyses in four ways. First, we included studies treating primary anxious, primary depressed, and mixed groups of youth and adult clients with internalizing disorders. Second, we examined effect sizes across a broad range of outcome measures. Previous internalizing-specific meta-analyses focused on calculating effect sizes from symptom measures (Johnsen & Friborg, 2015; Michael et al., 2005) or dropout (Gersh et al., 2017; Ong et al., 2016), and did not examine other outcomes such as functioning or treatment satisfaction.

Third, the current meta-analysis focused on studies that examined the role of therapist experience within a single sample, such as looking at correlations between years of experience and client outcomes. The previous meta-analyses on depression or anxiety made comparisons between effect sizes obtained in separate studies with clients who were treated by therapists of different experience levels. This approach may lack sensitivity to detect effects, as all therapists in each study had to be assigned to the same experience level. Comparing relatively inexperienced therapists from one study to experienced therapists in another study also ignores confounding factors between studies, such as differences in client severity or supervision quality. Finally, this study examined moderators thought to influence the relationship between therapist experience and client outcomes.

The current study therefore had three aims. Aim 1 was to determine the overall relationship between therapist experience and internalizing client out-comes aggregated across all study measures. Aim 2 was to examine moderators of these effects. Although we had no a priori hypothesis, we explored if the relationship between experience and client outcomes differed based on treatment approach (i.e., CBT versus non-CBT treatment). We hypothesized larger effect sizes would be found in adult versus youth samples (Johnsen & Friborg, 2015; Michael et al., 2005; Weisz et al., 1995). As no previous meta-analysis had examined primary depressed and primary anxious clients within the same sample, we had no a priori hypothesis regarding client diagnosis. Consistent with hypotheses put forth by Stein and Lambert (1995), we hypothesized larger effect sizes would be found in studies that included clients with comorbid disorders, provided equal supervision to all therapists, and randomized clients to therapists. We investigated, but had no a priori hypothesis, regarding the effect oftreatment manualization. Consistent with Beutler (1997), we hypothesized that larger effect sizes would be found in studies using more specific definitions of therapist experience (e.g., number of times using a manual) than in studies using broad definitions (e.g., number of years of clinical experience). We also examined publication year as a moderator, with no a priori hypothesis.

Finally, Aim 3 was to conduct subgroup analyses to examine differences in effect sizes based on variables that could not be examined via formal moderator analyses, due to the comparisons involving multiple effect sizes from the same study (e.g., effects on self-report versus IE-report measures). We calculated effect sizes separately based on different measure domains (e.g., anxiety symptoms, functioning) and rater of outcome (e.g., self-rated, IE rated). We hypothesized that larger effect sizes would be found when outcome was rated by IEs, as found in a previous broad population meta-analysis (Stein & Lambert, 1995). We had no a priori hypotheses regarding measure domain.

Method

When possible, we followed PRISMA (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) guidelines for meta-analysis. For details, please see Supplemental Table 1.

Search Procedure

We conducted an exhaustive article search of published and unpublished literature examining therapist experience and internalizing client outcomes using PsycINFO, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Dissertation & Theses Global. We used key words to identify relevant studies (search terms in Supplemental Table 2). We identified additional articles from past reviews and meta-analyses, reference lists of identified studies, and unpublished data via professional listservs and study authors.

Inclusion criteria for articles were: (i) written in English, (ii) included mental health professionals (i.e., people with training in psychotherapy), (iii) examined the impact of therapist experience specifically on internalizing client outcomes, and (iv) included adequate statistical information on relevant client outcomes for effect size coding. Studies that met all other inclusion criteria but did not offer necessary statistical information to compute effect sizes were initially included, and study authors were contacted for this information. Studies could be published/conducted in any year. We considered internalizing populations to include anxiety, depressive, post-traumatic stress (PTSD), and OCD, as well as related adjustment disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2013). We included PTSD and OCD despite their removal from the Anxiety Disorder section in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—5th Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), due to heavy overlap in symptomatology and treatment with the anxiety disorders (e.g., Goodwin, 2015). The clients in the studies fell into three presentations: primary anxiety, primary depressive, and mixed internalizing populations (i.e., therapists treated clients with anxiety or depressive disorders).

We were broad in our inclusion of therapist experience definitions (see Supplemental Table 3). Examples of definitions of therapist experience included professional versus paraprofessionals, general clinical experience (e.g., years conducting therapy), degree/schooling levels (e.g., bachelor’s versus master’s therapists), experience with client populations (e.g., number of anxious clients treated), experience with specific treatment (e.g., number of times using the Coping Cat), and professionals versus trainees. We did not include studies that characterized experience as “therapist age” due to the diverse ages at which therapists enter formal training. Outcome statistics included were pre-post M/SD, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, frequencies, t-tests, and Odds Ratios.

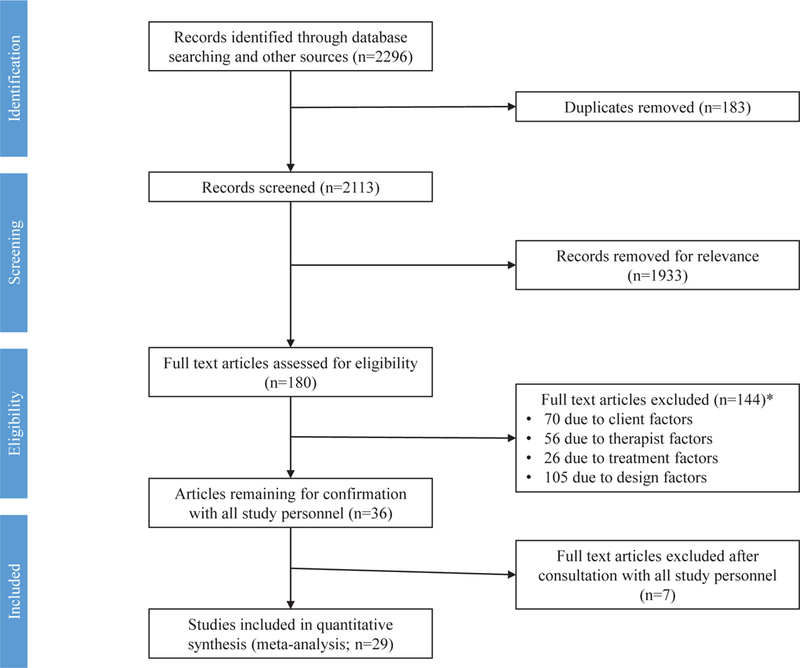

Articles were excluded if: (i) the treatment was not focused on internalizing concerns (e.g., college students seeking academic counseling) or (ii) the treatment providers were inappropriate (e.g., parents of clients) or only paraprofessional providers were used (see Figure 1). The initial search process identified 2296 articles. We removed 183 duplicates and 1933 studies were removed based on abstract review. Reasons for removal at this stage included focus on non-internalizing psychiatric disorders, focus on medical conditions, no outcome measures, and no psychotherapy. A graduate student (the study first author) and a trained undergraduate research assistant identified the remaining 180 articles as “included” or “excluded,” and indicated the reason for exclusion (i.e., client, therapist, treatment, or design factors). Reliability was examined on the first 40% of the articles between the screeners via Cohen’s (1968) kappa, which is considered acceptable if it is greater than 0.70 (McHugh, 2012). Interrater reliability ranged from .80 to .98 (overall inclusion/exclusion kappa = .80, client kappa = .89, therapist kappa = .84, treatment = .98, design kappa = .85). After reliability was met, the first author conducted random checks on the inclusion and exclusion of studies to combat drift. We excluded 151 studies from the sample, leaving 29 studies. Seven studies that met inclusion criteria were not included (Calleo et al., 2013; Ehlers et al., 2013; Hahlweg, Fie-genbaum, Frank, Schroeder, & von Witzleben, 2001; Mason, Grey, & Veale, 2016; McLay et al., 2012; Norton, Little, & Wetterneck, 2014; Shelton & Madrazo-Peterson, 1978) because authors could not be reached to obtain enough information to calculate effect sizes. Twenty-two studies were included in final effect size calculations, including two unpublished dissertations (Bisbey, 1995; Lewis, 2011).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for article screening. *Numbers add up to more than 144 because articles could meet exclusion for several factors. Client factors = Clients presented with non-internalizing disorders/symptoms (e.g., externalizing behaviors, feeding and eating disorders, personality disorders, substance abuse), Therapist factors = all therapists were of the same level of experience (e.g., all lay persons, all graduate students), no information was given to determine if variability in experience, or only 1–2 therapists were in the study, Treatment factors = Studies intentionally had treatment modality vary by experience group or treatment was academic counseling, medication management, and/or case management only, Design factors = Therapist experience was measured but never directly linked or examined with client outcomes.

Of note, many of the included studies compared multiple therapist groups within the same study (Franklin et al., 2003; Nyman, Nafziger, & Smith, 2010; Propst et al., 1994) or examined the same group of therapists according to two different definitions of experience (Huppert et al., 2001; Podell et al., 2013), creating several comparisons of interest per study. For parsimony, we will use the term “independent sample” or k to refer to unique comparisons, even though they may have been included in the same article. From this definition, this meta-analysis contained 35 independent samples from 22 unique articles.

Study and Effect Size Coding

Coding included calculation of effect size and coding of study characteristics and potential moderators. Coding was conducted by three graduate student coders. Interrater reliability was established by randomly sampling 50% of the articles to be coded by all three coders. Disagreements between coders were discussed with all three coders. In the rare case that coders could not agree, the codes were brought to a supervising faculty member for a final decision. Reliability for categorical codes (e.g., definition of therapist experience) was calculated using Cohen’s (1968) kappa. Reliability of continuous codes (e.g., client age) was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients. Both forms of reliability were considered acceptable if they were greater than .70 (McHugh, 2012). Reliability ranged from .72 to .98 across codes. Once reliability was established, the remaining articles were coded by pairs of coders to combat drift. Moderator variables included treatment approach, client age, diagnostic category, comorbidity, supervision, randomization, treatment manualization, definition of therapist experience, and study year (see Supplemental Table 3).

After consensus was reached on all codes, effect size, and moderator data were entered into Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software®, which was used to calculate either r (correlational studies) or d (between-group studies) effect sizes. We converted all effect sizes into Cohen’s d to allow all studies to be combined for analysis. All effect sizes were adjusted using Hedges’ g to attain an unbiased estimator (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Hedges’ g of .2, .5, and .8 represented small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Analyses

All analyses were run using the metafor package in R (Viechtbauer, 2010). We decided a priori to use a random effect model, allowing the true effect size to vary from study to study, due to the heterogeneity in methods, client sample, and treatment (Pigott, 2012). We calculated the overall effect size of therapist experience on client outcome (Aim 1) and effect sizes for the subgroup analyses (Aim 3) as weighted means, with each effect size weighted by the inverse of that independent sample’s variance. Moderator analyses (Aim 2) were conducted using mixed effect models. For categorical moderators, we computed weighted means for each group, variances, and standard errors of the group mean effect estimates, tested the null hypothesis that each group is equal to zero, and created confidence intervals around the weighted mean for each group (Rau-denbush, Cooper, Hedges, & Valentine, 2009). For study year, which was a continuous moderator, we estimated the variation of the error terms under the mixed effect model using REML, used meta-regression, tested the significance of the individual coefficients, and constructed the 95% confidence interval for these beta coefficients (Rau-denbush et al., 2009).

We examined whether there was evidence of a publication bias in our meta-analysis using a Funnel plot (Greenhouse & Inyengar, 2009). Interpreting funnel plot symmetry can be subjective (Sutton, 2009), so we also calculated Egger’s linear regression test. For significant models, we also calculated a Fail Safe N, a calculation that estimates the number of studies needed for the p-value to become insignificant (Rosenberg, 2005). In subgroup meta-analyses where there were less than 10 effect sizes, we did not create funnel plots or use Egger’s regression test, as the power of the regression test can be too low to distinguish chance from true asymmetry (Higgins & Green, 2011).

Handling Dependency

Most independent samples included multiple measures, and therefore yielded multiple effect sizes. To aggregate these effect sizes, we used the Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (BHHR, 2009) method, as it is the univariate method found to be least biased and most precise in large simulation studies (Del Re, 2015; Scammacca, Roberts, & Stuebing, 2014; Wei & Higgins, 2013). We aggregated effect sizes to obtain one effect size per independent sample in each analysis, using the MAd package in R, which averages all within-study effect sizes and variances, considering the correlations among the within-study outcome measures consistent with BHHR procedures (Cooper, Hedges, & Valentine, 2009). We kept the default correlation for between within-study effect sizes of r =.50, as several studies have found the average correlation between popular measures of anxiety and depression to be around this value (e.g., Wampold et al., 1997).

For Aims 1 and 2, we aggregated all measures for each study. For Aim 3, we aggregated based on the subgroup (e.g., all depression measures from a study), to avoid dependency within independent samples if treated as moderators. For Aim 3, we increased the correlation between within-study effect sizes to .70 to represent the increase in similarity between measures within each aggregating group, thereby using a slightly higher correlation which may increase Type II error (Scammacca et al., 2014).

Results

Final Study Sample for Meta-analytic Coding

The 35 included independent samples (from 22 articles) ranged in publication date from 1976 to 2016. Two of these studies (McLean & Hakstian, 1979; Russell & Wise, 1976) were included in previous within-study meta-analyses. Coding yielded a total of 208 effect sizes, representing 2383 clients and 352 therapists. Five independent samples from three articles focused on youth clients; the rest used adult clients. The client sample was primarily female (66.1%) and Caucasian (87.16%). Independent samples most often used CBT or CBT variants as treatment (k = 23), treated anxious clients (k = 19), included clients with comorbid diagnoses in the sample (k = 19), and used broad definitions of therapist experience (i.e., professionals versus paraprofessionals, general clinical experience, or degree type; k = 26). Seventeen independent samples used multiple raters of outcome, with 11 of the remaining independent samples relying on self-rated measures, and 7 relying on IE rated measures. Independent samples were split between those that randomized clients to therapists (k = 13) and those that did not (k = 15). They were also split on level of supervision provided to therapists, where 17 independent samples provided equal amounts of supervision to all therapists, and 16 provided more supervision to less experienced therapists (see Supplemental Table 4).

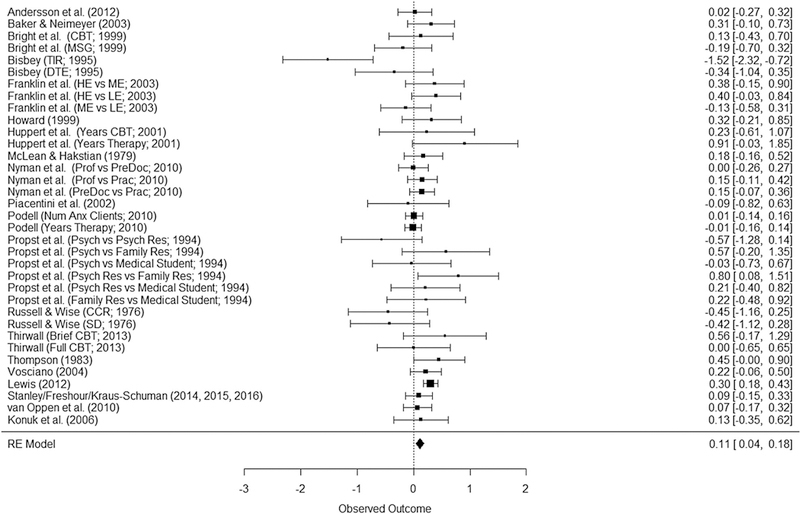

Aim 1: Examination of the Relationship Between Experience and Outcomes

When all measures were averaged within each independent sample, therapist experience was significantly related to internalizing client outcomes (Hedges’ g =.11, p =.002), suggesting that more therapist experience leads to better client outcomes (Table I; for individual study effect sizes, see Figure 2). This effect size fell below Cohen’s (1988) cutoff for a small effect. These findings did not appear to be impacted by publication bias given the symmetrical funnel plot and nonsignificant Egger’s regression test (z = −.56, p =.57). Rosenthal’s Fail Safe N indicated that 94 studies would have rendered the effect size nonsignificant.

Table I.

Random effects models.

| Model | k | Hedges’ g | 95% CI |

Qwithin | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| All outcomes aggregated | 35 | .11** | .04 | .18 | 59.84** | 24.16 |

| Outcomes aggregated by domain | ||||||

| Anxiety | 23 | .13 | −.02 | .28 | 63.84*** | 70.83 |

| Depression | 18 | .09 | −.002 | .19 | 20.79 | 23.36 |

| Internalizing Symptoms | 8 | .06 | −.05 | .15 | 4.73 | 0.00 |

| Functioning | 18 | .06 | −.03 | .15 | 17.56 | 5.19 |

| Satisfaction with treatment | 8 | .26* | .02 | .49 | 5.41 | 0.00 |

| Other measure domains (e.g., drop out, number of sessions, relapse rate) | 6 | .23* | .04 | .42 | 1.98 | 0.00 |

| Combination of internalizing and other symptom domains | 7 | .20 | −.19 | .58 | 7.77 | 20.11 |

| Outcomes aggregated by rater | ||||||

| Self-rated | 27 | .12** | .02 | .20 | 51.05** | 30.38 |

| Independent evaluator rated | 23 | .12 | −.007 | .25 | 45.22** | 50.52 |

| Caregiver rated | 2 | .005 | −.12 | .13 | .06 | 0.00 |

| Other (e.g., chart review) | 4 | .16 | −.03 | .35 | 1.54 | 0.00 |

p <.05.

p<.01

p<.001.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of outcomes across all measures.

Aim 2: Moderators of Effect Size Across all Measures

The Q statistic was first examined to determine variability in effect sizes. This test was significant (Q(32) = 59.85, p = .004), suggesting appropriateness of moderator analyses. We examined seven moderators: treatment approach (CBT or non-CBT), client age (adult or youth), client diagnostic category (primary anxiety, primary depression, or mixed internalizing), comorbidity (comorbidity allowed or not allowed/ unknown), supervision (equal supervision or less experienced therapists received more supervision), randomization (clients randomized to therapist or not randomized/unknown), treatment manualization (treatment manualized or not manualized/unknown), definition of therapist experience [broad (i.e., professionals versus paraprofessionals/trainees) or specific (i.e., experience with a specific client population)], and study year. Results are presented in Table II.

Table II.

Moderator analyses for all outcome measures aggregated.

| Model | k | Hedges’ g | 95% CI |

Qmoderators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Treatment Approach | |||||

| Intercept (Non-CBT treatments) | 31 | .12 | −.07 | .32 | .04 |

| CBT versus Non-CBT Treatments | −.02 | −.24 | .20 | ||

| Client age | |||||

| Intercept (Youth clients) | 35 | .02 | −.12 | .15 | 2.58 |

| Adult versus youth clients | .13 | −.03 | .28 | ||

| Client diagnostic category | |||||

| Intercept (Mixed internalizing) | 35 | .21*** | .11 | .30 | 8.79* |

| Primary anxiety versus mixed internalizing | −.18** | −.30 | −.05 | ||

| Primary depression versus mixed internalizing | .00 | −.19 | .19 | ||

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Intercept (No comorbidity allowed/unknown) | 35 | .08 | −.03 | .20 | .34 |

| Comorbidity allowed versus not allowed/unknown | .05 | −.11 | .20 | ||

| Supervision | |||||

| Intercept (Less supervision) | 33 | .18*** | .10 | .27 | 6.50* |

| Equal supervision versus more supervision for less experienced therapists | −.16* | −.28 | −.04 | ||

| Randomization | |||||

| Intercept (Randomization of clients) | 28 | .24*** | .14 | .34 | 8.19** |

| No randomization of clients versus randomization of clients | −.18** | −.30 | −.06 | ||

| Treatment manualization | |||||

| Intercept (No manualization) | 35 | .19*** | .10 | .29 | 4.71* |

| Treatment manualization versus no manualization | −.14* | −.27 | −.01 | ||

| Definition of therapist experience | |||||

| Intercept (Specific definitions) | 35 | .14* | .01 | .27 | .34 |

| Broad definitions versus specific definitions | −.05 | −.21 | .11 | ||

| Study year | |||||

| Intercept | 33 | −4.08 | −20.15 | 11.99 | .26 |

| Moderator | .002 | −.006 | .01 | ||

Note: CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p < .001.

Independent samples treating clients with mixed internalizing disorders (Intercept = .21, p <.0001) showed a positive experience-outcome relationship. Independent samples treating clients with primary depressive disorders also showed a positive relationship between experience and outcomes, with no detectable difference from studies treating mixed internalizing disorders (Moderator = .00, p = .99). In independent samples of clients with primary anxiety disorders, this relationship was attenuated and nonsignificant (Mod-erator= −.18, p = .006; Hedges’ g = .03), suggesting experience is less important in primary anxiety disorder treatment than in mixed internalizing or primary depressive disorder treatment.

Surprisingly, when independent samples provided more supervision to less experienced therapists, there was a significant positive relationship between therapist experience and outcome (Intercept = .18, p <.0001), whereas when therapists received equal supervision, this relationship was attenuated and became nonsignificant (Moderator = −.16, p =.01; Hedges’ g = .02). When clients were randomized to therapists, there was a significant positive relationship between therapist experience and outcome (Inter-cept=.24, p <.0001). When clients were assigned to therapists based on severity of presentation or next available therapist, this relationship was attenuated and became nonsignificant (Moderator = −.18, p = .004; Hedges’ g = .06). In independent samples where treatment was not manualized, there was a significant positive relationship between therapist experience and outcome (Intercept = .19, p < .0001). When treatment was manualized, this relationship was attenuated (Moderator = −.14, p = .03; Hedges’ g= .05), suggesting that less experienced therapists can attain equivalent client outcomes to experienced therapists with structured protocols. The relationship between experience and outcome did not differ by treatment approach, client age, comorbidity, therapist experience definition, or study year.

We examined the relationship between moderator variables to better understand our results and identify possible confounding moderators (Pigott, 2012). Relationships between categorical moderator variables were examined using Fisher’s exact test for count data, as the number of comparisons in each cell was often too low, violating chi-square assumptions (Agresti, 2002). Independent samples treating clients with anxiety disorders were more likely to provide equal supervision for all therapists, use CBT, use manualized treatments, and treat youth than studies treating depression or broad internalizing diagnoses (all p’s < .05). Of note, independent samples using CBT were much more likely to use treatment manuals, with none of the non-CBT independent samples using manualized treatments.

Aim 3: Relationship Between Experience and the Average Effect Size within Subgroups

Meta-analyses within measure domains.

The relationship between experience and treatment satisfaction was significant (k = 8, Hedges’ g = .26, p = .03). Rosenthal’s Fail Safe N returned a value of four studies. The relationship between experience and other outcome measures was significant (k = 6, Hedges’ g =.23, p =.01), indicating that more experienced therapists’ clients dropped out of treatment and relapsed less, and attended more sessions than those of less experienced therapists. Rosenthal’s Fail Safe N returned a value of six studies. No other outcome domains returned significant relationships between experience and internalizing client outcome (see Table I).

From a visual inspection of the funnel plots, depressive symptoms and functioning domains appeared to be asymmetrical, suggesting possible publication bias, whereas all other funnel plots appeared relatively symmetrical. The Egger’s regression tests for functioning (k = 18, z = 2.04, p = .04) were significant, and depressive symptoms (k = 18, z= −1.88, p =.06) approached significance, suggesting possible publication bias.

Meta-analyses within measure rater.

The relationship between experience and outcome was significant for self-rated outcomes (k = 27, Hedges’ g =.12, p =.008; Table I). The Rosenthal’s Fail Safe N returned a value of 57 studies. No other model showed a significant experience-outcome relationship. We examined funnel plots for self-rated and IE rated models only, as caregiver and other rated models included only two and three independent samples respectively. From visual inspection of the funnel plots, self-rated outcomes appeared to be asymmetrical. The funnel plot for IE rated out-comes appeared relatively symmetrical. The Egger’s regression test for self-rated measures and IE rated measures were nonsignificant (k = 27, z = −1.39, p = .16; k = 23, z = .47,p = .63).

Discussion

This meta-analysis sought to better understand the relationship between therapist experience and internalizing client outcomes. As hypothesized, therapists with more experience attained better outcomes with internalizing clients than less experienced therapists. Several significant moderators of this effect emerged including client diagnosis, treatment manualization, therapist supervision, and client randomization. Available data suggests depression may be more difficult to treat than anxiety (Cuijpers et al., 2013; Weisz et al., 2017). As such, therapist experience may be more important in the treatment of depressive disorder clients or clients with comorbid depression and anxiety. Our results were concordant with Johnsen and Friborg (2015) and Weisz et al. (1987, 1995) findings that more experience is related to better outcomes in internalizing clients, but inconsistent with the Michael et al. (2005) meta-analysis. This could be due to our primarily adult sample, though our moderator analyses suggested that therapist experience did not differ between adult and youth clients and the previous meta-analyses by Weisz and colleagues did find effects for internalizing youth. Our focus on within-study effect sizes was perhaps more sensitive to detect effects than the between-study approach utilized by Michael et al. (2005). Additional within-study examinations of therapist experience in youth samples are needed to fully understand the role therapist experience plays in different ages and diagnostic categories.

Experience was associated with better outcomes when treatments were not manualized, but not when manualized treatments were used. This finding has exciting implications for task shifting, as treatment manuals may help less experienced therapists obtain equivalent outcomes to more experienced therapists. It is also possible that this finding is attributable to client diagnosis, as primary anxiety studies were more likely to involve treatment manuals. Future research is needed to fully understand the potential role that treatment manuals might play in supporting less experienced therapists.

Contrary to our expectations, a positive relationship between experience and outcomes was found in studies where less experienced therapists received more supervision. One possible explanation for this finding is that supervision was confounded with client diagnosis, as the studies treating clients with primary anxiety disorders were more likely to offer equal amounts of supervision across experience levels.

As Stein and Lambert (1995) previously theorized, there was a significant positive relationship between therapist experience and client outcomes when clients were randomized to therapists, but not when they were assigned non-randomly. One explanation for this finding may be that, when non-random assignment is used, more experienced therapists might receive more complex clients that are more difficult to treat. Indeed, two included studies acknowledged that more severe clients were often assigned to experienced therapists (Franklin et al., 2003; Lewis, 2011). Unfortunately, many of the included studies did not report pre-treatment M/SDs for the different therapist groups or conduct analyses demonstrating equivalence in pre-treatment symptoms, so differences in initial client severity were unable to be statistically tested. Future studies on the role of therapist experience on client outcomes would benefit from random assignment.

Subgroup analyses by measure domain indicated that therapist experience seems to be related to higher client satisfaction and improvements in “other” measure domains (e.g., number of sessions, dropout), but not anxiety and functioning. The finding that therapist experience is related to higher client satisfaction is consistent with previous meta-analyses (Stein & Lambert, 1995). More experienced therapists may be able to more easily build rapport, respond client needs, and repair and maintain alliance than less experienced therapists, ultimately decreasing treatment dropout, increasing client satisfaction, and increasing the number of sessions attended.

Examination of effect sizes by reporter found a relationship between experience and outcomes for self-report measures only. This finding was contrary to our hypothesis that IE-rated outcomes would show larger effects than self-report (Stein & Lambert, 1995). However, the effect size for IE-rated outcomes was actually slightly larger than the effect size for self-reported outcomes (.1232 versus .1151, respectively), and was likely nonsignificant due to greater estimation uncertainty. Thus, it is possible that we were underpowered to detect a significant effect in IE-rated outcomes.

Limitations of the Current Study and of the Therapist Experience Literature

Overall, we found limited support for increased therapist experience leading to better internalizing client outcomes. Methodological concerns identified in previous meta-analyses were still present, even in newer studies. Over half of the studies did not randomize clients to therapists. Several studies also contained small client samples (<50 per group) and/or small therapist samples (<5 per group; Bisbey, 1995; Propst et al., 1994; Russell & Wise, 1976). Studies often did not report power analyses and were potentially underpowered to detect differences between therapist experience levels. Studies also rarely examined long-term client outcomes, leaving unknown whether experience is related to maintenance of treatment gains.

We could not investigate many moderators of interest due to limited information or homogeneity in our sample. More than half of the studies did not provide race/ethnicity information for their samples, and few focused on youth samples. Other variables could not be coded due to limited reporting or lack of heterogeneity in the included studies, including treatment setting (e.g., college counseling center, medical center), treatment delivery (e.g., individual versus group treatment), client recruitment procedures, and therapist caseload.

In the early studies included in our meta-analysis, therapists were often classified as “professionals” or “paraprofessionals,” (e.g., Bright et al., 1999; Russell & Wise, 1976). However, there was inconsistent categorization of these two groups across studies; some therapists considered paraprofessionals in one study would be considered professionals in another, which may have masked crucial group differences.

Despite efforts to combat publication bias, we only identified two unpublished dissertation studies (Bisbey, 1995; Lewis, 2011). Our subgroup meta-analysis examining the relationship between therapist experience and client functioning revealed an asymmetrical funnel plot and significant Egger’s regression test. Although Egger’s regression test is more powerful than nonparametric tests, it can be underpowered to detect publication bias in a smaller subgroup meta-analyses (Sutton, 2009). Further, Egger’s regression test does not test for publication bias; it tests for funnel plot asymmetry, which may be due to poor study methodology or small sample sizes (Higgins & Green, 2011). Thus, this positive result may indicate publication bias in the 18 independent samples included in this meta-analysis. Finally, we did not systematically code for study quality. However, there is evidence that quality coding schemas are highly subjective, and ratings may change even within the same investigator over time (Greco, Zangrillo, Biondi-Zoccai, & Landoni, 2013; Stegenga, 2011).

Strengths of the Current Study

This study brings several valuable additions to the literature on therapist experience. First, this study was conducted with more advanced statistical techniques and with many moderators of interest. Examining the role of therapist in different subgroups of internalizing disorders (i.e., primary anxiety, primary depression, and mixed internalizing disorders) also further explored findings from previous meta-analyses (Johnsen & Friborg, 2015; Michael et al., 2005; Weisz et al., 1987, 1995). We also examined a broad range of outcomes, including symptoms, functioning, as well as nonspecific indicators of treatment success (e.g., satisfaction, dropout). Examination of therapist experience differences within the same study also addressed the limitations present in between-study meta-analyses on this subject (Gersh et al., 2017; Johnsen & Friborg, 2015; Michael et al., 2005; Ong et al., 2016), as these approaches may lack sensitivity to detect effects and ignore potential confounding factors between studies. We believe all these factors add to our understanding of the relationship between therapist experience and client outcome.

Implications and Future Directions

Although this meta-analysis heeded the advice ofpre-vious meta-analysts and researchers, the relationship between therapist experience and internalizing client outcomes appears to be modest, and only under certain conditions. Consistent with the emerging literature supporting the use of task shifting in low-and middle-income countries (Barnett, Lau, & Miranda, 2018; Chibanda et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2014) and the use of stepped-care models in high-income countries (e.g., England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies program; Clark, 2012; Firth, Barkham, Kellett, & Saxon, 2015), it may be appropriate to consider increasing the role of lay therapists in treating clients with clients with anxiety. Our findings further suggest that the use of treatment manuals may allow for lay workers to obtain equivalent out-comes to more experienced therapists (e.g., Firth et al., 2015; Hooley, Gopalan, & Lucienne, 2017).

There are several confounding factors that can make the relationship between therapists at different levels of experience difficult to examine. Some studies have examined outcomes obtained by the same therapists over time as they gain experience. As in cross-sectional studies, some studies show small increases in therapist effectiveness as they gain experience (Owen, Wampold, Kopta, Rousmaniere, & Miller, 2016), and some show slight decreases in effectiveness but lower client dropout (Goldberg, Rousmaniere, et al., 2016). Future work using similar methodology and longer follow up periods within internalizing client populations would inform strategies to get more clients treatment and ways to train students in mental health Masters and Doctoral programs. This method may also be more amenable to study in naturalistic clinic settings than a randomized trial, increasing the generalizability of study results.

Despite limitations, the present analysis included newer, more methodologically sound studies, and is timely for implementation and service provision concerns. This study further adds to the growing therapist variability literature seeking to understand under which circumstances and for which clients particular types of therapists are the most effective. Renewed research in this basic area of psychotherapy research using longitudinal within-therapist designs is necessary to address many concerns in the literature, and to best serve the millions of people worldwide in need of mental health services yearly.

Supplementary Material

Clinical or methodological significance of this article:

This article examines the overall effect of therapist experience on internalizing client outcomes, as well as several moderators and subgroups that were unable to be examined in older meta-analyses. Results suggest therapist experience is important for outcomes in depressed clients and when treating mixed groups of internalizing clients, but not in clients with anxiety disorders. Use of treatment manuals appear to “level the field” between experienced and inexperienced therapists, as a significant relationship emerged between experience and outcomes when treatment manuals were not used. Findings lend guidance to efforts training lay people to provide services, training of clinicians, and future research in the area.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Soyeon Ahn and Eric Pedersen for their statistical consultation, and Drs Debbiesiu Lee and Saneya Tawfik for their helpful comments in earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1469802.

References

* Articles included in study.

- Agresti A (2002). Categorical data analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- *Andersson G, Carlbring P, Furmark T, & the S.O.F.I.E Research Group. (2012). Therapist experience and knowledge acquisition in internet-delivered CBT for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. PloS One, 7(5), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML,Lau AS,&Miranda J (2018). Layhealthworker involvement in evidence-based treatment delivery: A conceptual model to address disparities in care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 63(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS, & Norton NC (1985). Does professional training make a therapist more effective? Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE (1997). The psychotherapist as a neglected variable in psychotherapy: An illustration by reference to the role of therapist experience and training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4(1), 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- *Bisbey LB (1995). No longer a victim: A treatment outcome study for crime victims with post-traumatic stress disorder. San Diego: UMI Proquest. [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, & Horwood LJ (2007). Anxiety disorders and suicidal behaviours in adolescence and young adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, & Rothstein HR (2009). Subgroup analyses In Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (Eds.), Introduction to meta-analysis (pp. 149–186). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- *Bright JI, Baker KD,& Neimeyer RA (1999). Professional and paraprofessional group treatments for depression: A comparison of cognitive-behavioral and mutual support interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Owen JJ, Kopta SM, Minami T, Hanson MR, & Hirsch G (2013). Differences among trainees in client outcomes associated with the phase model of change. Psychotherapy, 50(2), 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttorff C, Hock RS, Weiss HA, Naik S, Araya R, Kirkwood BR,... Patel V (2012). Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(11), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleo JS, Bush AL, Cully JA, Wilson NL, Kraus-Schuman C, Rhoades HM,. Kunik ME (2013). Treating late-life GAD in primary care: An effectiveness pilot study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(5), 414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mesu P, Kajawu L, Cowan F, Araya R, & Abas MA (2011). Problem-solving therapy for depression and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: Piloting a task-shifting primary mental health care intervention in a population with a high prevalence of people living with HIV. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM (2012). The English improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) program In McHugh RK & Barlow DH (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological interventions (pp. 61–77). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provisions for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (2009). The hand-book of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, & Dobson KS (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. The CanadianJournal ofPsychiatry, 58(7), 376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re AC (2015). A practical tutorial on conducting meta-analysis in R. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 11(1), 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA (1979). Comparative effectiveness ofparaprofessional and professional helpers. Psychological Bulletin, 86(1), 80–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Grey N, Wild J, Stott R, Liness S, Deale A,. Clark DM (2013). Implementation of cognitive therapy for PTSD in routine clinical care: Effectiveness and moderators of outcome in a consecutive sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(11), 742–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth N, Barkham M, Kellett S, & Saxon D (2015). Therapist effects and moderators of effectiveness and efficiency in psychological wellbeing practitioners: A multilevel modelling analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 69, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Furr JM, Kalsy S, & Riggs DS (2003). A naturalistic examination of therapist experience and outcome of exposure and ritual prevention for OCD. Psychotherapy Research, 13(2), 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- *Freshour JS, Amspoker AB, Yi M, Kunik ME, Wilson N, Kraus-Schuman C,... Stanley M (2016). Cognitive behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder delivered by lay and expert providers has lasting benefits. International Journal ofGeriatric Psychiatry, 31(11), 1225–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricchione GL, Borba CP, Alem A, Shibre T, Carney JR, & Henderson DC (2012). Capacity building in global mental health: Professional training. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20(1), 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Sparkes SP, Auh EY, Vujicic M, & Soucat A (2011). Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: A review of recent evidence. Human Resources for Health, 9(1), 1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersh E, Hallford DJ, Rice SM, Kazantzis N, Gersh H, Gersh B, & McCarty CA (2017). Systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in individual psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 52, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT, Nissen-Lie HA, Nielsen SL, & Wampold BE (2016). Unpackingthe therapist effect: Impact of treatment length differs for high-and low-performing therapists. Psychotherapy Research, 48, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1216625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Rousmaniere T, Miller SD, Whipple J, Nielsen SL, Hoyt WT, & Wampold BE (2016). Do psychotherapists improve with time and experience? A longitudinal analysis of outcomes in a clinical setting. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM (2015). The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(3), 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco T, Zangrillo A, Biondi-Zoccai G, & Landoni G (2013). Meta-analysis: Pitfalls and hints. Heart, Lung and Vessels, 5(4), 219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse JB, & Inyengar S (2009). Sensitivity analysis and diagnostics In Cooper H, Hegdes LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (pp. 417–433). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Fiegenbaum W, Frank M, Schroeder B, & von Witzleben I (2001). Short-and long-term effectiveness of an empirically supported treatment for agoraphobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(3), 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattie JA, Sharpley CF, & Rogers HF (1984). Comparative effectiveness of professional and paraprofessional helpers. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 534–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, & Olkin L (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, & Green S (2011). Recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry. BMJ, 5, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, & Unutzer J (2018). Tasksharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: A systematic review. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley C, Gopalan G, & Lucienne T (2017). Barriers to task-shifting evidence based treatments in child welfare settings: Qualitative findings from an implementation trial. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Sand Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- *Howard RC (1999). Treatment of anxiety disorders: Does specialty training help? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30(5), 470–473. [Google Scholar]

- *Huppert JD, Bufka LF, Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, & Woods SW (2001). Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome in a multicenter trial for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(5), 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen TJ, & Friborg O (2015). The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 747–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, De Graaf RON, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I,... Kawakami N (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE,... Zaslavsky AM (2005). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(24), 2515–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Konuk E, Knipe J, Eke I, Yuksek H, Yurtsever A, & Ostep S (2006). The effects of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy on posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the 1999 marmara, Turkey, earthquake. International Journal ofStress Management, 13(3), 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- *Kraus-Schuman C, Wilson NL, Amspoker AB, Wagener PD, Calleo JS, Diefenbach G,... Stanley MA (2015). Enabling lay providers to conduct CBT for older adults: Key steps for expanding treatment capacity. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 5(3), 247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lewis CC (2011). Understanding patterns of change: Predictors of response profiles for clients treated in a CBT training clinic (Doctor of Philosophy). University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mason L, Grey N, & Veale D (2016). My therapist is a student? The impact of therapist experience and client severity on cognitive behavioural therapy outcomes for people with anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44(2), 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLay RN, Graap K, Spira J, Perlman K, Johnston S, Rothbaum BO,... Rizzo A (2012). Development and testing of virtual reality exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in active duty service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 177(6), 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean PD, & Hakstian AR (1979). Clinical depression: Comparative efficacy of outpatient treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(5), 818–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B,. Olfson M (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. Adolesents: Results of the national comorbidity survey -adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolscent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael KD, Huelsman TJ, & Crowley SL (2005). Interventions for child and adolescent depression: Do professional therapists produce better results? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2), 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Skavenski S, Kasoma M, Imasiku M, Bolton P,... Cohen JA (2013). Identification, modification, and implementation of an evidence-based psychotherapy for children in a low-income country: The use of TF-CBT in Zambia. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 7(1), 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Little TE, & Wetterneck CT (2014). Does experience matter? Trainee experience and outcomes during transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(3), 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nyman SJ, Nafziger MA, & Smith TB (2010). Client outcomes across counselor training level within a multitiered supervision model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(2), 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, & King NJ (1994). Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of internalizing problems in children: The role of longitudinal data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CW, Clyde JW, Bluett EJ, Levin ME, & Twohig MP (2016). Dropout rates in exposure with response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: What do the data really say? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 40, 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Wampold BE, Kopta M, Rousmaniere T, & Miller SD (2016). As good as it gets? Therapy outcomes of trainees over time. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Hancock JH, Bhana A, & Govender K (2014). A group-based counselling intervention for depression comorbid with HIV/AIDS using a task shifting approach in South Africa: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 158, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott TD (2012). Planning a meta-analysis in a systematic review In Pigott TD (Ed.), Advances in meta-analysis (pp. 13–32). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- *Podell JL, Kendall PC, Gosch EA, Compton SN, March JS, Albano AM,. Piacentini JC (2013). Therapist factors and outcomes in CBT for anxiety in youth. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(2), 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Propst A, Paris J, & Rosberger Z (1994). Do therapist experience, diagnosis and functional level predict outcome in short term psychotherapy? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 39 (3), 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Cooper BS, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (2009). Analyzing effect sizes: Random-effects models In Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.), Thehandbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (pp. 295–316). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Kuhl EA, & Kupfer DJ (2013). The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry, 12(2), 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, & Werbart A (2013). Therapist and relationship factors influencing dropout from individual psychotherapy: A literature review. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 394–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MS (2005). The file-drawer problem revisited: A general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution, 59(2), 464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Russell RK, & Wise F (1976). Treatment ofspeech anxietyby cue-controlled relaxation and desensitization with professional and paraprofessional counselors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 23(6), 583–586. [Google Scholar]

- Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J,... Underhill C (2007). Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 370(9593), 1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammacca N, Roberts G, & Stuebing KK (2014). Meta-analysis with complex research designs dealing with dependence from multiple measures and multiple group comparisons. Review of Educational Research, 84(3), 328–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JL, & Madrazo-Peterson R (1978). Treatment outcome and maintenance in systematic desensitization: Professional versus paraprofessional effectiveness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 25(4), 331–335. [Google Scholar]

- *Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Amspoker AB, Kraus-Schuman C, Wagener PD, Calleo JS,. Kunik ME (2014). Lay providers can deliver effective cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized trial. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegenga J (2011). Is meta-analysis the platinum standard of evidence? Studies in History and Philosophy ofScience Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy ofBiological and Biomedical Sciences, 42 (4), 497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DM, & Lambert MJ (1984). On the relationship between therapist experience and psychotherapy outcome. Clinical Psychology Review, 4, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DM, & Lambert MJ (1995). Graduate training in psychotherapy: Are therapy outcomes enhanced? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(2), 182–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton AJ (2009). Publication bias In Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (pp. 435–454). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- *Thompson LW, Gallagher D, Nies G, & Epstein D (1983). Evaluation of the effectiveness of professionals and nonprofessionals as instructors of “coping with depression” classes for elders. The Gerontologist, 23(4), 390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ameringen M, Mancini C, & Farvolden P (2003). The impact of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17(5), 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *van Oppen P, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, Schuurmans J, van Dyck R, & Emmelkamp PM (2010). Does the therapy manual or the therapist matter most in treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder? A randomized controlled trial ofexposure with response or ritual prevention in 118 patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(9), 1158–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich F, Benson K, & Ahn H (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empiricially, “all must have prizes”. Psychological Bulletin, 122(3), 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, & Higgins JP (2013). Estimating within-study covariances in multivariate meta-analysis with multiple outcomes. Statistics in Medicine, 32, 1191–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R,... Fordwood SR (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. American Psychologist, 72(2), 79–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Alicke MD, & Klotz M (1987). Effectiveness of psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A meta-analysis for clinicians. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(4), 542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Han SS, Granger DA, & Morton T (1995). Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 450–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, Moore RE, Cohen P, Alegria M,. Roper MT (1999). Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(9), 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.