Abstract

Background

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a widely used instrument for measuring levels of depression in patients in clinical practice and academic research; its factor structure has been investigated in various samples, with limited evidence of measurement equivalence/invariance (ME/I) but not in patients with more severe depression of long duration. This study aims to explore the factor structure of the PHQ -9 and the ME/I between treatment groups over time for these patients.

Methods

187 secondary care patients with persistent major depressive disorder (PMDD) were recruited to a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with allocation to either a specialist depression team arm or a general mental health arm; their PHQ-9 score was measured at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Exploratory Structural Equational Modelling (ESEM) was performed to examine the factor structure for this specific patient group. ME/I between treatment arm at and across follow-up time were further explored by means of multiple-group ESEM approach using the best-fitted factor structure.

Results

A two-factor structure was evidenced (somatic and affective factor). This two-factor structure had strong factorial invariance between the treatment groups at and across follow up times.

Limitations

Participants were largely white British in a RCT with 40% attrition potentially limiting the study’s generalisability. Not all two-factor modelling criteria met at every time-point.

Conclusion

PHQ-9 has a two-factor structure for PMDD patients, with strong measurement invariance between treatment groups at and across follow-up time, demonstrating its validity for RCTs and prospective longitudinal studies in chronic moderate to severe depression.

Keywords: PHQ-9, factor structure, measurement equivalence/invariance, Exploratory Structural Equational Modelling, major depressive disorder, chronic depression

Introduction

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item self-reported scale measuring the symptoms of major depression derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, (fourth edition (DSM-IV)) (Kroenke et al., 2001; Spitzer et al., 1999). It can help clinicians quickly evaluate the severity of a person’s mood and has been applied in various patient populations such as coronary heart disease (de Jonge et al., 2007), spinal cord injury (Krause et al., 2010), diabetes (Zhang et al., 2013), and primary care (Baas et al., 2011; Petersen et al., 2015); the scale has also been used to measure depression in the general population (Yu et al., 2012).

Recently the PHQ-9 was used as depression measure for secondary care patients with persistent major depressive disorder (PMDD) in a pragmatic clinical trial conducted in the UK (Morriss et al., 2016; Morriss et al., 2010)) As a well validated and frequently used instrument, the PHQ-9’s underlying factor structure has been explored for various patient populations already. However no study has yet investigated the factor structure for specialist mental health patients with persistent or chronic moderate to severe unipolar depressive disorder. Understanding the factor structure of PHQ-9 for secondary care patients with PMDD could help to understand precisely what is being measured by this instrument to aid the interpretation of studies such as randomised controlled trials of interventions or large scale mechanistic or epidemiological investigations in this population of patients. Additionally it could help understand the underlying dimensions and mechanism of long term unipolar depressive disorder (Elhai et al., 2012).

Studies that have explored the factor structure of PHQ-9 have shown heterogeneous findings (Petersen et al., 2015), with the number of underlying factors varying between one and two (Baas et al., 2011; Krause et al., 2010; Richardson and Richards, 2008). These differences might be due to the different patient populations, physical and mental co-morbidities, research design and analyses, e.g. using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) compared to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Two factor structure items have generally been grouped into two types: somatic (e.g. sleep difficulties, appetite changes and fatigue) and non-somatic/affective items (e.g. depressed mood, feeling of worthlessness and suicidal thoughts). However, even with the two factors structure, there are still some inconsistent item-factor mapping patterns across studies (Elhai et al., 2012; Petersen et al., 2015). Patients with PMDD are more likely to have other axis 1 psychiatric disorders; in particular: generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder and hypochondriasis as well as more atypical depression and treatment resistance (Rush et al., 2012), which is in itself associated with melancholia and a number of personality traits (Bennabi et al., 2015). Clinically, melancholia is associated with more complete loss of pleasure, low energy, walking and talking more slowly and less reactivity of mood among features measured by the PHQ-9 (Parker et al., 2013).

Given that PHQ-9 has been used as a depression outcome measure in various studies, establishing the measurement invariance/equivalence (ME/I) across groups is a logical prerequisite to conducting substantive cross-group and/or follow-up time comparisons (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). Measurement invariance of PHQ-9 was made between male and female (Petersen et al., 2015) and across ethnic groups (Baas et al., 2011); a further study by (Richardson and Richards, 2008) also reported that the PHQ-9 factor structure was relatively stable across follow-up times for patients with spinal cord injury. However, this was performed using only exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on PHQ-9 measures collected at each follow-up time and comparing the factor loading by eye to draw their conclusion. No formal statistical tests were applied to justify the cross-time measurement invariance (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). Hence, conclusions on measurement invariance across follow-up time requires further examination.

To make group comparisons of PHQ-9 development across follow-up time points, longitudinal between-group measurement invariance should be established before making any valid inference based on comparing PHQ-9 scores between treatment and control groups across measurement time. Nevertheless, no study has yet investigated the between group measurement invariance across follow-up time.

EFA and CFA have previously been used to investigate PHQ-9 factor structure (Petersen et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2012). However, both EFA and CFA have methodological limits (Asparouhov and Muthén, 2009; Marsh et al., 2014). Using EFA, it is impossible to incorporate latent EFA factors into subsequent analyses and it is not easy to test measure invariance across groups and/or times (Marsh et al., 2014).With CFA, each item is strictly allowed to load on one factor and all non-target loadings are constrained to zero. In applied research, it is generally justifiable by theory and/or item contents that item(s) could cross load on different latent factors. Restrictive zero loading typically results in inflated CFA factor correlation and leads to biased estimates in CFA modelling when other variables are included in the model (Marsh et al., 2014). The latest methodology development integrates the best features of both EFA and CFA together as Exploratory Structural Equational Modelling (ESEM), applying EFA rigorously to specify more appropriately the underlying the factor structure together with applying the advanced statistical methods typically associated with CFAs (Marsh et al., 2014). Hence, ESEM will be performed to test the factor structure of PHQ-9 for secondary care patients with PMDD. Measurement invariance tests of PHQ-9 factor structure, i.e. between treatment group invariance at and across follow-up time, will also be conducted using ESEM.

In summary, the factor structure and measurement invariance between treatment groups across follow-up time of PHQ-9 for secondary care patients with PMDD will be explored. This study will apply methodologically rigorous ESEM modelling to explore the factor structure of the PHQ-9 scale and measurement invariance between treatment groups at and across follow-up time points.

Method

Patients and instruments

Participants (N = 187) were drawn from a multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating outcomes of a specialist mood disorders team for treatment seeking adults in secondary mental health care services (Special depression service, SDS) compared to treatment as usual (TAU). At the time of recruitment participants were receiving treatment in secondary mental health services from community mental health teams, out-patient and in-patient units in three mental health trusts across Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Cambridgeshire in the UK.

Participants were eligible for the study if they were; thought by the referrer to have primary unipolar depression; aged 18 years or over; able and willing to give oral and written informed consent to participate in the study; had been offered or received direct and continuous care from one or more health professionals in the preceding 6 months and currently be under the care of a secondary care mental health team; had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder with a current major depressive episode according to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID)(First et al., 1997); met five of nine NICE criteria for symptoms of moderate depression; had a score of ≥16 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS17)(Williams et al., 2008); and had a Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)(American Psychiatric Association, 1994) score ≤ 60. Participants were not included if they were; in receipt of emergency care for suicide risk, at risk of severe neglect, or a homicide risk, but were not excluded because of such risk provided the risk was adequately contained in their current care setting and the primary medical responsibility for care was with the referral team; did not speak fluent English; were pregnant; had unipolar depression secondary to a primary psychiatric or medical disorder, except when bipolar disorder was identified by the research team after referral with unipolar depression because an SDS would be expected to manage bipolar depression in clinical practice (n=8, 4.3%).

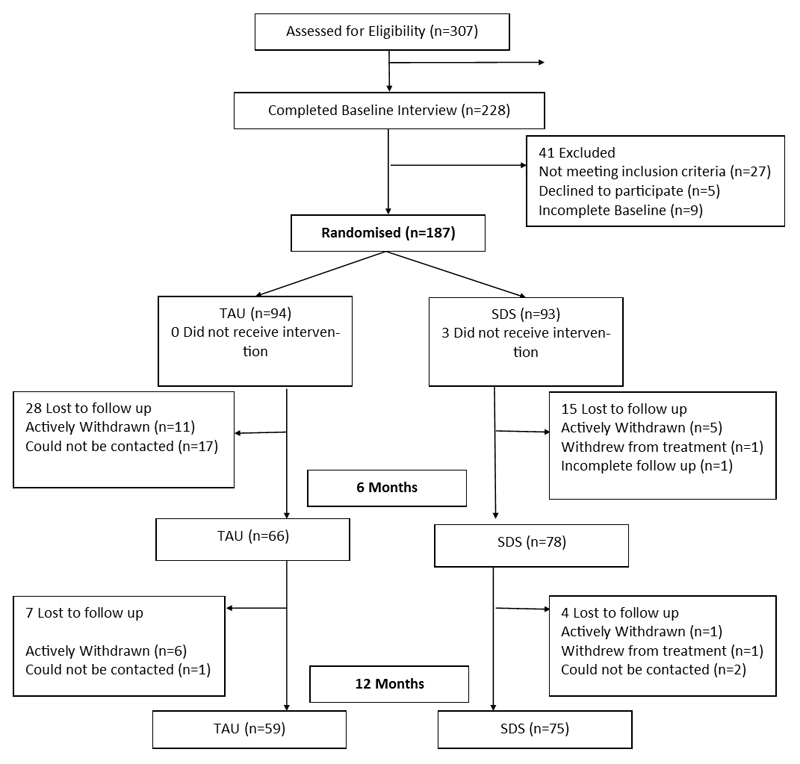

Of the total 187 patients, 93 (49.7%) patients were allocated to the treatment arm and 94 (50.3%) to treatment as usual (TAU) arm. (See Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram of participant flow through the study). The primary outcome measures were HDRS17 and GAF which were measured at baseline, 6 and 12 month follow up time points (Morriss et al., 2010); the secondary outcome measures included Beck Depression Inventory version I (BDI-I) (Beck et al., 1961), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR) (Rush et al., 2006), the modified Social Adjustment Scale (SAS-M) (Cooper et al., 1982), Patient Doctor Relationship Questionnaire (PDRQ) (Van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2004) and the EQ-5D-3L (Euroqol Group, 1990). The study design and data collection procedures have been described in the published protocol (Morriss et al, 2010), more details about the trial and its primary outcomes can also be found from the trial report by Morriss et al, 2016.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of participant flow through the study

PHQ-9 was a secondary outcome measure used to assess participants’ depressive symptoms and was collected at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. The PHQ-9 asks participants to rate the frequency of depressive symptoms they had experienced in the two weeks prior on an ordinal scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days) and 3 (nearly every day). Developed from DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorder the PHQ-9 comprises of following 9 items: 1) Little interest or pleasure in doing things; 2) Feeling down, depressed or hopeless; 3) Trouble falling asleep, or sleeping too much; 4) Feeling tired or having little energy. 5) Poor appetite or overeating; 6) Feeling bad about yourself or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down; 7) Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television; 8) Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed or the opposite being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual; 9) Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way. Participants’ item scores are summed up to a total score to reflect the severity of depression.

Statistics

ESEM was used to explore the factor structure of the PHQ-9 (Marsh et al., 2014). With reference to existing works on factor structure of PHQ-9, one factor and two factor structure models were tested for data across all follow-up times. Measurement invariance between treatment groups across all follow-up time points for the best fitted factor structure was also tested using ESEM. For measurement invariance testing the overall longitudinal measurement invariance test (measuring cross time measurement invariance) for all participants as one group was conducted first, followed by testing between group measurement invariance across follow-up times. The former measurement invariance test included the following consecutive steps: configural invariance, metric invariance test (item factor loading invariance) and scalar invariance (item threshold invariance) test (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). The between group measurement invariance across follow-up times was performed using the same testing order as for overall longitudinal measurement invariance. However, with each test step, we first tested the model with relevant parameters set to be equal between groups at each follow-up time, and then moved to test the invariance between groups across follow-up time periods, i.e. parameters were set equal between groups and across follow-up time. All ESEM models were performed using software Mplus 7.3 in its default setting (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). Ordinal item score was analysed with the WLSMV estimator and missing values were automatically accounted for using the full-information maximum likelihood approach built into Mplus (Enders and Bandalos, 2001; Graham, 2003).

Several fitting indices along with chi-square (χ2) test were used to judge model fit as χ2 tests are sensitive to large sample sizes and non-normal data (Wen et al., 2004). For the comparative fit index (CFI) and the non-normed fit index (NNFI), values above 0.90 generally indicate models with acceptable fit, a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08 usually indicates reasonable fit with a threshold of 0.05 reflecting a close fit to the data (Marsh et al., 2010). Model comparisons were generally evaluated by reference to the χ2 change test; here we used the Mplus DIFFTEST function to conduct χ2 difference tests as the WLSMV estimator was used to analyse ordinal items scores (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). However, χ2 change tests are influenced by sample size and data non-normality as well (Marsh et al., 2009), i.e. if the sample size is large, a trivial differences would result in a significant value of χ2 change, which means rejecting the null hypothesis that there is no real difference between models (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002; Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). The CFI change is independent of both model complexity and sample size and not correlated with the overall fit measurements, a reduction of 0.01 or more in CFI suggests the null hypothesis of no difference should be rejected (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). We therefore mainly judged model improvement on the CFI change (Guo et al., 2009; Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). A number of specific modelling details will be presented alongside the results, the Mplus code performing various ESEM models and a brief on ME/I test procedure could be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4622053.v2

Results

Participants’ background

Participants’ average age was 46.6 years (SD=11.4) with 114 being females (61.5%), mean duration of illness 16.7 years (sd=11.3, range: 0.5- 49 years), with mean baseline HDRS17 score of 22.6 (sd=8.2, range 16-40), and baseline BDI mean score of 35.0 (sd=8.9, range: 13-56). More details of participants’ background information including disease status are presented in Table 1. The trial evidenced statistical and clinically important treatment effect of differences in change from baseline measure of PHQ-9 at 9 month (-3.5, 95% CI: (-5.7, -1.3), p=0.002) and 12 month (-2.9, 95% CI: (-5.2, -0.7), p=0.011) compared to general specialist mental health care. On the primary outcome measure HDRS17 statistical and clinically important differences did not emerge until 18 months (Morriss et al., 2016). Not all participants had PHQ-9 scores, with five patients having no PHQ-9 data and were therefore excluded from the analysis. The actual number of participants having PHQ-9 data are shown in the last column of Table 2.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Total(187) | |

| Age, mean (sd,range) | 47(11.5, 11.3-86) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 114(61) |

| Employment status [N=181]: n (%) | |

| full-time employment | 39(22) |

| Other employment1 | 21(12) |

| Retired | 26(14) |

| Unemployed | 73(40) |

| Receipt of benefits [N=181]: n (%) | 124(69) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| before 16 | 10(5) |

| up to 18 or apprenticeship | 81(43) |

| Highest qualification – Advanced levels | 40(21) |

| Highest qualification –degree or post-degree | 56(30) |

| Married or co-habiting, n (%) | 92(49) |

| Children, 1 or more, n (%) | 119(64) |

| Baseline HDRS17, mean (sd, range) | 22.6(8.2, 16-40) |

| Baseline GAF, mean (sd, range) | 48.5(8.2, 21-65) |

| Baseline BDI-I, mean (sd, range) | 35.6(8.9, 11-56) |

| Baseline PHQ9, mean (sd, range) | 19.6(4.8, 5-27) |

| Baseline QIDS-SR, mean (sd, range) | 27.5(7.2, 10-48) |

| SAS-M, mean (sd, range) | 2.0(0.6,0.3-3.6) |

| PDRQ, mean (sd, range) | 62.5(16.8,24-90) |

| Baseline EQ-5D-3L index score, mean (range), n | 0.349(-0.349-0.848),175 |

| Years since first diagnosis of depression mean (sd, range) | 16.7(11.3, 0.5-49) |

| Depressed > 1 year, n (%) | 162(87) |

| Years since first diagnosisof depressionmedian (range) | 11.5(0.5-51) |

| Observed PHQ-9 Mean change from baseline (95% CI) | |

| 3 month | -1.85(-2.86,-0.84) |

| 6 month | -4.28(-5.36,-3.21) |

| 9 month | -5.18(-6.28,-4.09) |

| 12 month | -5.75(-6.88,-4.62) |

| Clinical Characteristic | |

| Current unipolar major depressive episode1 | 179 (95.7) |

| Current bipolar 2 major depressive episode | 8 (4.3) |

| Past major depressive episode | 156 (83.4) |

| Current melancholia | 105 (56.1) |

| Current psychotic symptoms (delusions and/or hallucinations) | 49 (26.2) |

| With dysthymia (“double depression”) | 17 (9.1) |

| Any other comorbid anxiety, substance use or eating disorder | 151 (80.3) |

| Substance use disorder (alcohol and/or drug abuse or dependence) | 32 (17.1) |

| Eating disorder (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder) | 22 (11.8) |

| Anxiety disorder: | 146 (78.1) |

| Panic disorder or agoraphobia | 86 (46.2) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 85 (45.7) |

| Simple phobia | 48 (25.8) |

| Social phobia | 44 (23.7) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 37 (19.9) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 30 (16.1) |

| Somatoform disorder (hypochondriasis or other somatoform disorder) | 31 (16.6) |

| Current active physical illness: | 120 (64.2) |

| One current active physical illness | 77 (41.2) |

| Two or more active physical illnesses | 25 (13.4) |

| Current rheumatological or orthopedic problem | 43 (23.4) |

| Current cardiovascular disorder (including diabetes mellitus) | 33 (17.1) |

| Current respiratory disorder | 26 (13.5) |

| Current neurological disorder | 18 (9.4) |

Referral to RCT made as a unipolar major depressive episode but using standardised psychiatric interview diagnosed as bipolar 2 major depressive episode.

Table 2. Model fitting indices for one-factor modelling and two-factor modelling.

| Data | Model | χ2(df), p = | RMSEA | CFI | NNFI | N(%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | ESEM 1 factor | 97.387(27), p<.001 | 0.121 | 0.906 | 0.875 | 177(94.7) |

| ESEM 2 factor | 37.455(19), p=.007 | 0.074 | 0.975 | 0.953 | ||

| 3 month | ESEM 1 factor | 94.715(27), p<.001 | 0.133 | 0.942 | 0.923 | 141(75.4) |

| ESEM 2 factor | 58.160(19), p<.001 | 0.121 | 0.967 | 0.937 | ||

| 6 month | ESEM 1 factor | 82.598(27), p<.001 | 0.133 | 0.960 | 0.947 | 117(62.6) |

| ESEM 2 factor | 36.802(19), p=.008 | 0.089 | 0.987 | 0.976 | ||

| 9 month | ESEM 1 factor | 41.291(27), p=.039 | 0.068 | 0.995 | 0.993 | 113(60.4) |

| ESEM 2 factor | 28.324(19), p=.077 | 0.066 | 0.996 | 0.993 | ||

| 12 month | ESEM 1 factor | 34.757(27),p=.145 | 0.054 | 0.996 | 0.994 | 100(53.5) |

| ESEM 2 factor | Not convergent | |||||

| CFA 2 factor | 34.258(26),p=.129 | 0.056 | 0.995 | 0.993 | ||

*: number of patients having valid item score

RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI= comparative fit index; NNFI= non-normal fit index.

Factor structure of PHQ-9

In line with the modelling steps, results of PHQ-9 factor structure exploration are presented first, followed by results of the overall longitudinal measurement invariance test and longitudinal between group measurement invariance test. Table 2 contains the results of model fit indices of one-factor and two-factor models for data collected at each time point. The two-factor ESEM model for 12 month data was not (?) convergent so a two-factor CFA model was run instead, using a model with item-factors mapped as patterns shown in Table 2, based on reference to the two-factor ESEM factor structure presented from data collected at the other follow-up time points. Results in table 2 showed that the two-factor structure models generally fitted the data better than a one-factor structure model. The CFI index was >0.90 for both 1 and 2 factor solutions at each time point but compared to baseline the 2 factor solution varies by -0.012 to 0.021 whereas the 1 factor solution varies by 0.096 over time. The NNFI is >0.90 at all time points for the 2 factor solution but is only 0.875 at baseline. The RMSEA is <0.08 at 3 time-points in the 2 factor solution but only at 2 points in the 1 factor solution. The patterns of item-factor mapping and item factor loading are largely similar across each follow-up data point.

Overall measurement invariance across follow-up time

With reference to the results of ESEM modelling for each individual dataset, we put all data as one group and sequentially ran the measurement invariance test model: configural invariance, loading invariance and item threshold invariance. The pattern of item-factor mapping and item factor loadings, which are the result of the invariant loading model, are presented in Table 3, the model fit indices for each measurement invariance testing model are presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Item Factor loading (se) for PHQ-9 factors (N=182).

| Item | Factor1 | Factor2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.566(0.056) | 0.223(0.072) |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed or hopeless | 0.760(0.041) | 0.072(0.051)# |

| 3. Trouble falling asleep, or sleeping too much | 0.023(0.064)# | 0.526(0.052) |

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.415(0.065) | 0.350(0.063) |

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating | 0.002(0.005)# | 0.654(0.046) |

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself – or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 0.791(0.035) | -0.004(0.004)# |

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 0.276(0.070) | 0.478(0.063) |

| 8. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or the opposite – being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual |

-0.067(0.089)# | 0.702(0.058) |

| 9. Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way | 0.819(0.050) | -0.061(0.069)# |

Note: All loadings without # are statistically significant at p=<0.001 level

Table 4. Overall longitudinal Measurement Equivalence/Invariance Model fitting indices and comparison (N=182).

| Invariance Model | χ2(df), p= | RMSEA | CFI | NNFI | Δχ2(df), p= | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Configural | 1175.587(865), p<0.001 | 0.044 | 0.947 | 0.939 | ||

| 2. Loading | 1178.478(921), p<0.001 | 0.039 | 0.956 | 0.953 | 63.496(56), p=0.229 | - 0.009 |

| 3. Threshold a | 1546.641(1028), p<0.001 | 0.053 | 0.911 | 0.915 | 577.949(107), p<0.001 | 0.045 |

| 4. Threshold b# | 1309.062(1024), p<0.001 | 0.039 | 0.951 | 0.953 | 172.243(103),p<0.001 | 0.005 |

# free baseline and 3 month factor mean estimates.

RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI= comparative fit index; NNFI= non-normal fit index; Δχ2 = change in chi-square; ΔCFI = change in comparative fit index

The configural invariance model result showed the two factor structure model with similar patterns of item-factor mapping was maintained across follow-up time (χ2(df)= 1175.59 (865), p<0.001; RMSEA=0.044, CFI=0.947, NNFI=.939) (Table 4). The invariant loading model fitted data slightly better than the configural invariance model with smaller RMSEA and increased CFI/NNFI values, in addition to non-significant χ2 change. Table 3 results show item 4 had a cross factor loading (0.415 and 0.350) with slightly higher loading for factor 1 than factor 2. Item 7 and item 1 also had non-negligible cross factor loadings. With reference to the item content, factor one could be termed as an affective factor and factor two could be specified as a somatic factor. For threshold invariance across follow-up time using Mplus default settings where all latent factor means were fixed to 0 for model identification purposes (model threshold a in Table 4), the model fitted data well (χ2(df)= 1546.641(1028), p<0.001, RMSEA=0.053, CFI=0.911, NNFI=0.915), but the CFI dropped 0.045. i.e. more than 0.01 cut-off value, from the invariance loading model (threshold a in Table 4). The model modification indices suggested freeing baseline and 3 month factor 1 mean estimates could significantly improve model fitting. However we had to free both factor 1 and 2 mean estimates as required by the ESEM modelling procedure (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). The final threshold invariance across follow-up time model (model threshold b in Table 4) showed 0.005 CFI drop from the invariance loading model. Results in Table 4 showed that strong factorial invariance was evidenced across follow-up time periods.

Between treatment group longitudinal measurement invariance

On top of overall longitudinal measurement invariance, we further tested the between group longitudinal measurement invariance, ie. treatment group ME/I at and across follow-up time. Model fitting indices of each between-group longitudinal measurement invariance model were presented in Table 5. When performing multiple group CFA with categorical items, the scale factor had to be fixed to 1 for model identification purposes for the configural invariance and invariant loading models, but scaled factors were freely estimated in treatment group for the between group invariant threshold model (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). Hence the invariant threshold (model 4 in Table 5) and invariant loading model (model 3 in Table 5) were not nested models; therefore the DIFFTEST can’t be performed directly to test χ2 change between Table 5 model 3 and model 4. The χ2 change test between model 3 and 4 were therefore tested by Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 change test with modelling using the WLSM estimator (Satorra and Bentler, 2001). All other model fitting information shown in Table 5 is from modelling with the default WLSMV estimator.

Table 5. Between treatment arm longitudinal Measurement Equivalence/Invariance Model fitting indices and comparison (N=182).

| Invariance Model | χ2(df), p= | RMSEA | CFI | NNFI | Δχ2(df), p= | ΔCFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Configural | 2043.942(1730), p<0.001 | 0.045 | 0.946 | 0.939 | ||

| 2 | Equal group loading at each time | 2082.055(1800), p<0.001 | 0.041 | 0.952 | 0.947 | 86.688(70), p=0.086 | -0.006 |

| 3 | Equal group loading at and across follow-up time | 2131.921(1856), p<0.001 | 0.040 | 0.953 | 0.950 | 76.259(56), p=0.037 | -0.001 |

| 4 | Equal group threshold at each time | 2231.112(1934), P<0.001 | 0.041 | 0.949 | 0.948 | 89.270(78), p=0.180# | 0.004 |

| 5 | Equal group threshold at and across flow-up time | 2383.243(2040), P<0.001 | 0.043 | 0.941 | 0.943 | 224.619(106), p<0.001 | 0.008 |

# Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 test using WLSM estimator.

RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI= comparative fit index; NNFI= non-normal fit index; Δχ2 = change in chi-square; ΔCFI = change in comparative fit index

Table 5 shows that all between-group longitudinal invariance models fitted the data well in that all model CFIs and NNFIs are above 0.9 and RMSEAs are below the 0.08 cut-off value. ΔCFIs from the previous models are all less than 0.01cut-off value so the strong factorial invariance between groups across follow up time periods for PHQ-9 were evidenced in secondary care PMDD patients.

Discussion

The PHQ-9 is a widely used instrument for measuring levels of depression in patients in clinical practice and academic research and though its factor structure has been investigated in various samples and across demographics, it has not been explored in patients with long-term moderate to severe depression. Furthermore no formal statistical tests have been applied to justify the cross-time measurement invariance in PHQ-9 and nor has the between group measurement invariance across follow-up time been investigated.

The factor structure of the PHQ -9 and the ME/I between treatment groups over time for British psychiatric patients with PMDD was therefore investigated and it was found that a two-factor structure fitted the data best. The two factors may be called ‘affective’ and ‘somatic’. The affective factor is measured by items including “little interest or pleasure in doing things”, “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”, “feeling tired or having little energy”, “feeling bad about yourself” and “thoughts of being better off dead”; the somatic factor is measured by items including “trouble falling asleep”, “poor appetite or overeating”, “trouble concentrating on things” and “moving or speaking so slowly…”. Most items clearly loaded on only one factor but the item “Feeling tired or having little energy”, loaded almost equally on both factors while two other items “little pleasure” and “poor concentration”, loaded mainly on one factor but also on to a small degree.

Although a two factor structure was evidenced in present study, the long term depression condition and the relevant comorbidities shown in PMDD patients make the PHQ-9 item-factor association mapping somehow different from results based on other kind of samples such as soldiers (Elhai et al., 2012), spine injury patients (Krause et al., 2010) and primary care patient (Petersen et al., 2015). These studies showed that the somatic factor has five items with item “Fatigue” generally measuring the non-somatic dimension; but our current study shows that the item “Fatigue” loaded highly in the affective factor together with sizable loading on the somatic factor. This might reflect the PMDD patients’ typical comorbidities such as anxiety and hypochondriasis (Rush et al., 2012) in addition to their persistent melancholia symptoms (Parker et al., 2013). Furthermore, the ESEM, which allows cross factor loading, provided an opportunity to investigate the depression factor-items association for PMDD patients measured by PHQ-9 questionnaire. Unlike CFA results where items loaded on only one factor, cross factor loadings in ESSEM suggested that the depression factor structure measured by PHQ-9 might not be the same as factors measured in other sample groups, e.g. items Anhedonia, Fatigue and Concentration Difficulty showed some loading on both somatic and affective components in PMDD patients. This cross factor loading pattern were largely similar as the one from an EFA study where depression in spinal cord injury patients’ 25 years post-injury was explored (Richardson and Richards, 2008).

This two-factor structure was found to have strong factorial measurement invariance both across time and also between treatment groups across follow-up time. The two-factor structure of PHQ-9 for secondary care PMDD patients is consistent with results from studies in other populations such as US soldiers and German primary care patients (Elhai et al., 2012; Petersen et al., 2015). Thus the PHQ-9 is a valid measure of depression over time in persistent moderate to severe depressed patients in specialist mental health care, as well as cross-sectionally in less chronic or severe primary care or community samples of patients with unipolar depressive episodes.

Measurement part invariance between groups across follow up time is the logical prerequisite to meaningfully compare the PHQ-9 score between two treatment groups collected at each measurement time for making a valid statistical inference, when assessing secondary care PMDD patients using the PHQ-9. The configural invariance implies that the PHQ-9 items evoked the same conceptual framework in defining the two latent constructs for both groups when measured at different times; the invariant item factor loadings show that the association and patterns mapping the items and factors are stable between two treatment groups across the 12 month follow up time; the item threshold invariance showed evidence of a trivial systematic response bias between groups across follow-up time (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). The invariant item threshold and invariant loading model indicated the existence of strong factorial invariance, i.e. the measurement scales have the same operational definition between two groups at and across follow-up time. Hence the between group and cross-time PHQ-9 mean score comparison is explicitly meaningful (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002).

Measurement invariance testing also generally includes testing the item uniqueness invariant between groups and/or across follow-up time (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000), i.e. item residual variance invariant across follow-up time. Nevertheless, as item score was treated as an ordinal scale in this study, an item uniqueness invariance model could not be tested directly as used for modelling with continuous items (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). This methodological constraint was a limitation of the current study and alternative methodologies employing invariant item uniqueness should be explored in the future.

There are also other methodological strengths and limitations in this study. The first strength lies in that the recently developed ESEM approach, which is regarded as having integrated the benefits of both EFA and CFA (Marsh et al., 2014), was used to investigate the factor structure of the PHQ-9 and to conduct measurement invariance testing. Cross-factor loadings between treatment groups were explicitly modelled in the current study with ESEM advantages. A second strength is that ordinal item scores were analysed using a nonlinear model which is more appropriate than treating ordinal items as continuous quantities, which has been the previous approach in factor analysis studies (Elhai et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2011; Richardson and Richards, 2008; Yu et al., 2012). A third strength is the between group longitudinal measurement invariance was tested using a multiple group approach with longitudinal data (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000); this makes good use of Mplus’ built-in missing value analysis function to take into account missing value information under a Missing at Random assumption. This approach will increase the power of analysis as all patients were included in modelling for each measurement time; it also take into account and estimates the association between factors measured at different time points (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000).

Limitations include the selection of patients who were all participants in a randomised controlled trial that excluded patients with a baseline HDRS17 Score below 16 and a GAF score of above 60. Therefore the results apply only to patients with at least moderate to severe depression at baseline although some of their scores fell into the mild to moderate range over time. There may be systematic differences between patients who agree to participate in a randomised controlled trial of treatment and those that do not; the sample was on average middle aged and white British, therefore the results may not apply to people with extremes of age or other ethnic backgrounds. Although PMDD is not strictly the same as treatment-resistant or chronic depression, the baseline characteristics and chronicity of depression in this sample suggests that the vast majority of patients would have also met criteria for both chronic depression and treatment resistant depression.

A further limitation is that not all two-factor model fitting indices, when analysed separately at each time point, meet the suggested model fitting criteria required for model fitting evaluation. This could be due to random sampling errors, quite high attrition over time with the loss of just over 40 per cent of the sample by 12 months or because the trial treatment has alleviated the depression symptoms. However the same factor structures were evidenced at each measurement time if all data were modelled simultaneously, suggesting that specialist depression service treatment with both drug and psychological treatment had not changed the nature of the depression over time even when the severity of symptoms measured on the PHQ-9 had reduced. In terms of ESEM modelling, parameter estimates for the ESEM model cannot be freely fixed to improve the modelling fit with the current version of Mplus. This remains a methodological challenge.

As a secondary data analysis, the sample size used in this study was pre-specified during trial design stage (Morriss et al., 2010). A size of 180 of participants was recommended to be sufficient for most factor analytic modelling under conditions with various numbers of factors, the ratio of item/factor and level of communalities (Mundfrom et al., 2005). Researchers have found that larger sample sizes were not always needed for factor analytical modelling (MacCallum et al., 1999; Mundfrom et al., 2005; Pearson and Mundform, 2010). Hence, in the present study, ESEM model fitting results at each follow up time shown in Table 2 exhibited the same factor analysis modelling at 9 and 12 month follow up times, despite having fewer patients due to attrition and generally fitted data better than modelling on baseline, 3 and 6 month data where there weremore participants. Nevertheless, a larger sample size with more items could help to improve factor analysis model fitting (MacCallum et al., 1999). Our study also showed longitudinal ME/I models with a two factor structure fitted data very well, while the ESEM 2-factor model using only 12 month follow-up data couldn’t converge, possibly due to fewer participants following attrition compared to earlier time points.

In conclusion, the PHQ-9 measure for British secondary care patients with PMDD showed two underlying latent factors: affective and somatic. This two-factor structure was evidenced to have strong factorial measurement invariance between treatment arms across follow-up. Therefore the factor structure of the PHQ-9 is not altered over time nor with combined psychological and drug treatment suggesting that it is a valid and robust self-rated outcome measure for further interventional, aetiological or epidemiological research in people with PMDD, chronic depression or treatment resistant depression in specialist mental health settings.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was supported by centre grant funding from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) for Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire, NIHR CLAHRC East Midlands, NIHR CLAHRC Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, NIHR CLAHRC East of England, UK Medical Research Council, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust and Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research, the National Health Service, the Medical Research Council nor the Department of Health in England. The work was supported by contributions from the CLAHRC Specialist Mood Disorder Study Group Ayesha Alrumaithi, Vijender Balain, Angie Balwako, Marcus Barker, Michelle Birkenhead, Paula Brown, Brendan Butler, Jo Burton, Isobel Chadwick, Adele Cresswell, Jo Dilks, Paige Duckworth, Heather Flambert, Richard Fox, Paul Gilbert, Emily Hammond, Joy Hodgkinson, Gail Hopkins, Valentina Lazarevic, Jane Lowey, Ruth MacDonald, Sarah EM Larson, Julie McKeown, Richard Moore, Inderpal Panasar, Mat Rawsthorne, Kathryn Reeveley, Jayne Simpson, Katie Simpson, Kasha Siubka-Wood, Gemma Walker, Samm Watson, Shirley Woolley, Nicola Wright, Min Yang, Ian Young. We would also like to acknowledge the help and support of the Mental Health Research Network and the Clinical Research Network in the East Midlands and East of England, and the University of Nottingham for providing sponsorship.

Abbreviations

- CFA

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI

comparative fit index

- EFA

exploratory factor analysis

- ESEM

exploratory structural equation modelling

- ME/I

measurement equivalence/invariance

- NNFI

non-normal fit index

- PMDD

persistent major depressive disorder

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SDS

specialist depression service

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest.

None of the authors reports any financial or personal conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Sandra Simpson, Nottinghamshire Healthcare Foundation Trust.

Prof Tim Dalgleish, Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge.

Rajini Ramana, Cambridge and Peterborough Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

Prof Min Yang, West China School of Public Health, Sichuan University, PR China.

Prof Richard Morriss, CLAHRC-EM, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Baas KD, Cramer AOJ, Koeter MWJ, van de Lisdonk EH, van Weert HC, Schene AH. Measurement invariance with respect to ethnicity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;129:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennabi D, Aouizerate B, El-Hage W, Doumy O, Moliere F, Courtet P, Nieto I, Bellivier F, Bubrovsky M, Vaiva G, Holztmann J, et al. Risk factors for treatment resistance in unipolar depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;171:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Osborn M, Gath D, Feggetter G. Evaluation of a modified self-report measure of social adjustment. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:68–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge P, Mangano D, Whooley MA. Differential association of cognitive and somatic depressive symptoms with heart rate variability in patients with stable coronary heart disease: Findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:735–739. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815743ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Contractor AA, Tamburrino M, Fine TH, Prescott MR, Shirley E, Chan PK, Slembarski R, Liberzon I, Galea S, Calabrese JR. The factor structure of major depression symptoms: A test of four competing models using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Psychiatry Research. 2012;199:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation for missing data in Structural Equation Models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Euroqol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I) American Psychiatric Press, Inc; Washington, D.C: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Adding missing-data relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2003;10:80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Aveyard P, Fielding A, Sutton S. The factor structure and factorial invariance for the decisional balance scale for adolescent smoking. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;16:158–163. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Fielding A, Sutton S, Aveyard P. Psychometric Properties of the Processes of Change Scale for Smoking Cessation in UK Adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;18:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Reed KS, McArdle JJ. Factor structure and predictive validity of somatic and nonsomatic symptoms from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9: A longitudinal study after spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010;91:1218–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: the validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Lüdtke O, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJS, Trautwein U, Nagengast B. A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:471–491. doi: 10.1037/a0019227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Morin AJS, Parker PD, Kaur G. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:85–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Trautwein U. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling, Integrating CFA and EFA: Application to Students' Evaluations of University Teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:439–476. [Google Scholar]

- Morriss R, Garland A, Nixon N, Guo B, James M, Kaylor-Hughes C, Moore R, Ramana R, Sampson C, Sweeney T, Dalgleish T. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a specialist depression service versus usual specialist mental health care to manage persistent depression: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:821–831. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss R, Marttunnen S, Garland A, Nixon N, McDonald R, Sweeney T, Flambert H, Fox R, Kaylor-Hughes C, James M, Yang M. Randomised controlled trial of the clinical and cost effectiveness of a specialist team for managing refractory unipolar depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundfrom DJ, Shaw DG, Ke TL. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. International Journal of Testing. 2005;5:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LK. Mplus user's guide. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, McCraw S, Blanch B, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Synnott H, Rees A-M. Discriminating melancholic and non-melancholic depression by prototypic clinical features. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;144:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RH, Mundform DJ. Recommended sample size for conducting exploratory factor analysis on dichotomous data. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2010;9 [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JJ, Paulitsch MA, Hartig J, Mergenthal K, Gerlach FM, Gensichen J. Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for female and male primary care patients with major depression in Germany. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;170:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson EJ, Richards JS. Factor structure of the PHQ-9 screen for depression across time since injury among persons with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53:243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Zisook S, Fava M, Sung SC, Haley CL, Chan HN, Gilmer WS, Warden D, Nierenberg AA, Balasubramani GK, et al. Is prior course of illness relevant to acute or longer-term outcomes in depressed out-patients? A STAR*D report. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:1131–1149. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler P. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JW, the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study, G Validation and utility of a self-report version of prime-md: The phq primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Feltz-Cornelis C, Van Oppen P, Van Marwijk H, De Beurs E, Van Dyck R. A patient-doctor relationship questionnaire (PDRQ-9) in primary care: development and psychometric evaluation. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:4–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Hau KT, Marsh HW. Structural equation model testing: Cutoff criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2004;36:186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Kobak KA, Bech P, Engelhardt N, Evans K, Lipsitz J, Olin J, Pearson J, Kalali A. The GRID-HAMD: standardization of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;23:120–129. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f948f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Tam WWS, Wong PTK, Lam TH, Stewart SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ting R, Lam M, Lam J, Nan H, Yeung R, Yang W, Ji L, Weng J, Wing Y-K, Sartorius N, et al. Measuring depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Hong Kong Chinese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;151:660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]