Abstract

Objective

Beta-lactam antibiotics are recommended as first-line for treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia. The objective of this study was to compare effectiveness of anti-MSSA therapies among bacteremia patients exclusively exposed to 1 antimicrobial.

Method

This was a national retrospective cohort study of patients hospitalized in Veterans Affairs medical centers with MSSA bacteremia from January 1, 2002, to October 1, 2015. Patients were included if they were treated exclusively with nafcillin, oxacillin, cefazolin, piperacillin/tazobactam, or fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin and levofloxacin). We assessed 30-day mortality, time to discharge, inpatient mortality, 30-day readmission, and 30-day S. aureus reinfection. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using propensity-score (PS) matched Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results

When comparing nafcillin/oxacillin (n = 105) with cefazolin (n = 107), 30-day mortality was similar between groups (PS matched n = 44; HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.11–4.00), as were rates of the other outcomes assessed. As clinical outcomes did not vary between nafcillin/oxacillin and cefazolin, they were combined for comparison with piperacillin/tazobactam (n = 113) and fluoroquinolones (n = 103). Mortality in the 30 days after culture was significantly lower in the nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin group compared with piperacillin/tazobactam (PS matched n = 48; HR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.01–0.78), and similar when compared with fluoroquinolones (PS matched n = 32; HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.30–5.96).

Conclusions

In hospitalized patients with MSSA bacteremia, no difference in mortality was observed between nafcillin/oxacillin and cefazolin or fluoroquinolones. However, higher mortality was observed with piperacillin/tazobactam as compared with nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin, suggesting it may not be as effective as a monotherapy in MSSA bacteremia.

Keywords: antibiotic treatment, bloodstream infection, comparative effectiveness, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, Veterans

Among hospitalized patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia, higher mortality was observed with exclusive piperacillin/tazobactam monotherapy as compared with exclusive nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin monotherapy.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia is associated with mortality rates as high as 22%–42% [1, 2]. S. aureus can metastasize to other organs, including the heart (ie, endocarditis) in up to 30%–40% of patients, making appropriate patient management crucial for the prevention of infection-related complications and mortality [3]. Antistaphylococcal penicillins and cefazolin generally are recognized as preferred treatment options against MSSA BSIs [4–8]. Furthermore, other beta-lactams (eg, piperacillin/tazobactam) and fluoroquinolones are utilized clinically for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bloodstream infections (BSIs), despite the lack of data supporting this practice.

Several observational comparative effectiveness studies of antistaphylococcal penicillins and cefazolin for the treatment of MSSA BSIs have been conducted in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Asia, and Canada, ranging from approximately 100 to 7300 patients [4–10]. Although 2 studies favor beta-lactam therapy over vancomycin for definitive treatment of MSSA BSIs [10, 11], effectiveness between cefazolin and antistaphylococcal penicillins is harder to elucidate as several studies have found no difference in outcomes [4–8] and 2 studies reported better outcomes with cefazolin [9, 12]. A recent meta-analysis of 7 studies, analyzing 1589 patients receiving cefazolin and 2802 patients receiving antistaphylococcal penicillins, reported significantly lower 90-day mortality with cefazolin [12]. Similar findings were observed in another recent meta-analysis that included 10 studies and 4728 patients [13]. However, these findings are difficult to interpret due to broad and varying antimicrobial treatment definitions, including exposures to various antibiotic therapies over the course of infection, which produced within-treatment-group heterogeneity in the meta-analysis and limited direct comparison between studies. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare effectiveness between preferred monotherapy treatments (ie, nafcillin, oxacillin, and cefazolin), and alternative monotherapy treatments, including piperacillin/tazobactam and fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin and moxifloxacin) in patients with MSSA BSI. Our cohort uniquely describes patients treated exclusively with 1 of these antistaphylococcal antimicrobial agents.

METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

We identified a retrospective cohort of patients with MSSA-positive blood cultures that were collected January 1, 2002, to October 1, 2015, during a hospital admission at a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) aged 18 years old or older, (2) remained admitted for more than 2 days, and (3) survived for more than 2 days. The culture collection date served as the index date. Antibiotic therapies were assessed from the index date through the discharge date or the first 30 days after culture for admissions of longer durations. We identified patients treated with a single antimicrobial therapy for the duration of treatment. Patients receiving combination therapy or with a change in therapy were excluded. For our study, we identified patients treated with nafcillin, oxacillin, cefazolin, piperacillin/tazobactam, or fluoroquinolone (moxifloxacin and levofloxacin) monotherapy. To eliminate the influence of confounding by comedication, we only included patients treated exclusively with these antibiotics of interest. Therefore, we excluded patients with changes or switches in therapy and also excluded patients with other doses of systemic, empiric, or definitive antimicrobial agents.

Clinical data were obtained from national VA databases and included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic and procedure codes during outpatient visits and inpatient stays, microbiologic and chemistry laboratory data, vital signs, and pharmacy data, including bar code medication administration records [14, 15]. Current and past comorbidities were identified from ICD-9-CM codes. The modified Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III score was utilized to assess severity of illness, as previously defined [15]. We assessed clinical outcomes including all-cause mortality within 30 days of the first positive MSSA blood culture (index date), length of hospital stay, length of intensive care unit stay, inpatient mortality, 30-day readmission, and 30-day S. aureus (ie, MSSA and methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) reinfection.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in patient characteristics that were assessed for the following groups compared: (1) nafcillin/oxacillin versus cefazolin, (2) nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin versus piperacillin/tazobactam, and (3) nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin versus moxifloxacin/levofloxacin. Therefore, the following steps were repeated for each comparison. Initial assessment of differences included chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Then likelihood ratio testing was used to identify patient characteristics associated with both exposure and clinical outcomes. Next, propensity scores (PS) using logistic regression with backwards stepwise elimination were developed. Characteristics, including age, sex, severity of illness, intensive care stays, and other characteristics independently associated with both exposure and clinical outcomes, were used to build the propensity score model. For each PS model, the absence of multi-collinearity and goodness of fit were confirmed. We identified matches using nearest neighbor matching within a caliper of 0.05. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression model. A sensitivity analysis adjusting Cox models for propensity score quintiles was performed. Analyses were performed with SAS software v. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

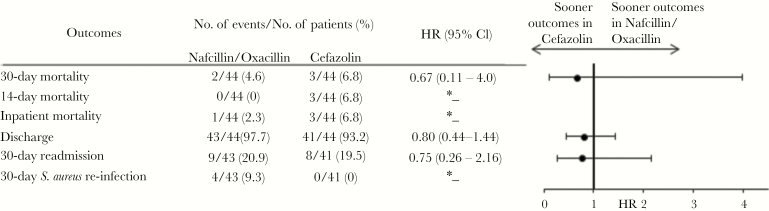

A total of 428 patients were identified and met final inclusion criteria for analysis. Of them, 105 were in the nafcillin or oxacillin group (24.5%), 107 in the cefazolin group (25.0%), 113 in the piperacillin/tazobactam (26.4%), and 103 in the fluoroquinolone group (24.1%). We first compared nafcillin/oxacillin with cefazolin (Table 1). The Charlson comorbidity index was similar between the nafcillin/oxacillin and cefazolin groups (median, 2 vs 2; P = .61); however, patients in the cefazolin group had higher rates of chronic kidney disease (41.1% vs 27.6%; P = .04), older age (mean, 64 vs 60.3; P = .03), and earlier antimicrobial treatment initiation from culture (median, 1 vs 2 days; P = .009) when compared with nafcillin/oxacillin. Baseline characteristics were balanced between the nafcillin/oxacillin and cefazolin groups via propensity score matching (nafcillin/oxacillin n = 44, cefazolin n = 44). All clinical outcomes were similar between the exposure groups, including 30-day mortality (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.11–4.00), discharge (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.44–1.44) and 30-day readmission (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.26–2.16) (Figure 1). Consequently, the nafcillin/oxacillin and cefazolin were combined (n = 212) to compare preferred treatment options with piperacillin/tazobactam (n = 113) and fluoroquinolones (n = 103), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Receiving Cefazolin and Nafcillin/Oxacillin Therapy

| Overall cohort | Propensity-score matched cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Cefazolin (n = 107) | Nafcillin or oxacillin (n = 105) | P value | Cefazolin (n = 44) | Nafcillin or oxacillin (n = 44) | P value |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 64.0 ± 12.8 | 60.3 ± 12.4 | .03 | 60.8 ± 13.3 | 62.3 ± 12.3 | .57 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 105 (98.1) | 103 (98.1) | 1.0 | 43 (97.7) | 43 (97.7) | 1.0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 27.9 ± 7.0 | 28.0 ± 7.3 | .95 | 27.6 ± 7.9 | 27.6 ± 7.5 | .99 |

| Obese, n (%) | 41 (38.3) | 35 (33.3) | .45 | 14 (31.8) | 16 (36.4) | .65 |

| Year of treatment | ||||||

| 2002–2009, n (%) | 78 (72.9) | 86 (81.9) | .12 | 36 (81.8) | 37 (84.1) | .78 |

| 2010–2015, n (%) | 29 (27.1) | 19 (18.1) | .12 | 8 (18.2) | 7 (15.9) | .78 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | .61 | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1.5–4) | .51 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Alcoholism | 11 (10.3) | 15 (14.3) | .37 | 5 (11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Cancer | 11 (10.3) | 13 (12.4) | .63 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 27 (25.2) | 21 (20.0) | .36 | 10 (22.7) | 10 (22.7) | 1.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (7.5) | 13 (12.4) | .23 | <5 (<11.4) | 5 (11.4) | .43 |

| Diabetes mellitus, complicated | 20 (18.7) | 13 (12.4) | .21 | 7 (15.9) | 5 (11.4) | .53 |

| Diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 31 (29.0) | 41 (39.1) | .12 | 13 (29.6) | 21 (47.7) | .08 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 44 (41.1) | 29 (27.6) | .04 | 18 (40.9) | 18 (40.9) | 1.0 |

| Dialysis | 13 (12.2) | 17 (16.2) | .40 | 8 (18.2) | 12 (27.3) | .31 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 17 (15.9) | 15 (14.3) | .74 | 7 (15.9) | 10 (22.7) | .42 |

| Coagulopathy | <5 (<4.7) | <5 (<4.8) | 1.0 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Coronary heart disease | 35 (32.7) | 39 (37.1) | .50 | 13 (29.6) | 17 (38.6) | .37 |

| Congestive heart failure | 18 (16.8) | 15 (14.3) | .61 | 8 (18.2) | 7 (15.9) | .78 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 23 (21.5) | 27 (25.7) | .47 | 10 (22.7) | 6 (13.6) | .27 |

| Hypertension | 65 (60.8) | 60 (57.1) | .59 | 26 (59.1) | 28 (63.6) | .66 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 16 (14.9) | 11 (10.5) | .33 | 5 (11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Liver disease | 9 (8.4) | 16 (15.2) | .12 | 5 (11.4) | 7 (15.9) | .53 |

| Community onset infection,b n (%) | 78 (72.9) | 75 (71.4) | .81 | 34 (77.3) | 35 (79.6) | .79 |

| Intensive care admission, n (%) | 5 (4.7) | 6 (5.7) | .73 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 11 (10.3) | <5 (<4.8) | .07 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| APACHE score,b median (IQR) | 25.5 (17–37) | 22 (14–34) | .06 | 23 (15–33) | 20 (13–37) | .55 |

| Source of infection,c n (%) | ||||||

| Endocarditis | 7 (6.5) | 8 (7.6) | .76 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | .68 |

| Skin and soft tissue infections | 28 (26.2) | 18 (17.1) | .11 | 12 (27.3) | 10 (22.7) | .62 |

| Osteomyelitis | 12 (11.2) | 14 (13.3) | .64 | 6 (13.6) | 6 (13.6) | 1.0 |

| Urine | <5 (<4.7) | 8 (7.6) | .06 | 0 | 5 (11.4) | .06 |

| Respiratory | <5 (<4.7) | <5 (<4.8) | .68 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Surgical site | 6 (5.6) | <5 (<4.8) | .28 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Chronic ulcer | 8 (7.5) | <5 (<4.8) | .25 | <5 (<11.4) | <5 (<11.4) | 1.0 |

| Prior healthcare exposures, n (%) | ||||||

| Hospitalization prior 30d | 14 (13.1) | 18 (17.1) | .41 | 6 (13.6) | 6 (13.6) | 1.0 |

| Nursing home prior 30d | <5 (<4.7) | <5 (<4.8) | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Time to antimicrobial initiation from culture, median days (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | .009 | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 2.5 (0–4) | .68 |

| Inpatient antimicrobial duration, median days (IQR) | 8 (5–14) | 9 (6–16) | .14 | 7 (4–14) | 7 (5–16) | .41 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

aCulture-confirmed source of infection.

bWith missing values.

cWithin 48 hours of index culture.

Figure 1.

Clinical Outcomes in Propensity-Matched Cefazolin-Treated and Nafcillin/Oxacillin-Treated Patients With Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremiaa.a The propensity score was derived from an unconditional logistic regression model and controlled for the variables listed in Supplementary Table S4. The asterisk symbol denotes that the sample size (n) was too small.

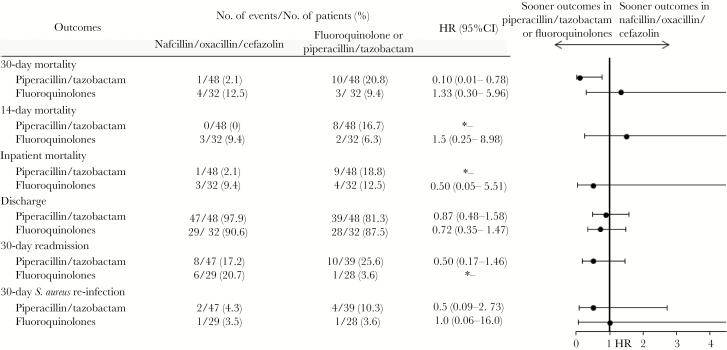

The piperacillin/tazobactam group (n = 113), compared with the nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin group (n = 212), was older (66.6 vs 62.2 years, P = .003), with higher comorbidity scores (3 vs 2, P = .0001) and APACHE scores (34.5 vs 24.0, P < .0001; Table 2). Intensive care unit admissions (13.3% vs 5.2%, P = .01), and previous hospitalizations (24.8% vs 15.1%, P = .03) were more common in the piperacillin/tazobactam group, with significant variations in infection source. These baseline characteristics were balanced via a propensity score model (nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin n = 48, piperacillin/tazobactam n = 48) and are further detailed in Table 2. In the propensity-score matched cohort, time to 30-day mortality was significantly higher in the piperacillin/tazobactam group than the preferred treatment group (HR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.01–0.78; Figure 2). Although time to antimicrobial initiation from culture and duration of therapy were included in the propensity score model, they remained significantly different in the matched groups. In a sensitivity analysis, inclusion of these variables in the Cox proportional hazards model did not change the effect estimates.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Receiving Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Nafcillin/Oxacillin/Cefazolin Therapy

| Overall cohort | Propensity-score matched cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Piperacillin/ tazobactam (n = 113) | Nafcillin or oxacillin or cefazolin (n = 212) | P value | Piperacillin/ tazobactam (n = 48) | Nafcillin or oxacillin or cefazolin (n = 48) | P value |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 66.6 ± 12.9 | 62.2 ± 12.7 | .003 | 64.4 ± 13.8 | 63.3 ± 13.0 | .69 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 111 (98.2) | 208 (98.1) | 1.0 | 48 (100) | 47 (97.9) | 1.0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.9 ± 7.2 | 27.9 ± 7.1 | .21 | 26.8 ± 7.6 | 27.0 ± 6.0 | .90 |

| Obese, n (%) | 38 (33.6) | 76 (35.9) | .69 | 16 (33.3) | 16 (33.3) | 1.0 |

| Year of treatment | ||||||

| 2002–2009, n (%) | 76 (67.3) | 164 (77.4) | .05 | 36 (75.0) | 36 (75.0) | 1.0 |

| 2010–2015, n (%) | 37 (32.7) | 48 (22.6) | .05 | 12 (25.0) | 12 (25.0) | 1.0 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4) | .0001 | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–5) | .34 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Alcoholism | 12 (10.6) | 26 (12.3) | .66 | 7 (14.6) | 7 (14.6) | 1.0 |

| Cancer | 22 (19.5) | 24 (11.3) | .05 | 8 (16.7) | 7 (14.6) | .78 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 21 (18.6) | 48 (22.6) | .39 | 7 (14.6) | 7 (14.6) | 1.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 9 (8.0) | 21 (9.9) | .56 | 5 (10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus, complicated | 37(32.7) | 33 (15.6) | .0003 | 13 (27.1) | 10 (20.8) | .47 |

| Diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 48 (42.5) | 72 (34.0) | .13 | 19 (39.6) | 17 (35.4) | .67 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 41 (36.3) | 73 (34.4) | .74 | 14 (29.2) | 16 (33.3) | .66 |

| Dialysis | 7 (6.2) | 30 (14.2) | .03 | <5 (<10.4) | 5 (10.4) | .71 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 22 (19.5) | 32 (15.1) | .31 | 5 (10.4) | 6 (12.5) | .75 |

| Coagulopathy | 10 (8.9) | 8 (3.8) | .06 | 5 (10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | .44 |

| Coronary heart disease | 29 (25.7) | 74 (34.9) | .09 | 12 (25.0) | 11 (22.9) | .81 |

| Congestive heart failure | 26 (23.0) | 33 (15.6) | .10 | 9 (18.8) | 5 (10.4) | .25 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 42 (37.2) | 50 (23.6) | .01 | 12 (25.0) | 14 (29.2) | .65 |

| Hypertension | 76 (67.3) | 125 (59.0) | .14 | 34 (70.8) | 30 (62.5) | .39 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 24 (21.2) | 27 (12.7) | .04 | 10 (20.8) | 5 (10.4) | .16 |

| Liver disease | 10 (8.9) | 25 (11.8) | .42 | 5 (10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | .71 |

| Community onset infection,b n (%) | 81 (71.7) | 153 (72.2) | .93 | 33 (68.8) | 36 (75.0) | .50 |

| Intensive care admission, n (%) | 15 (13.3) | 11 (5.2) | .01 | <5 (<10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | .36 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 8 (7.1) | 15 (7.1) | .99 | <5 (<10.4) | 8 (16.7) | .03 |

| APACHE score,b median (IQR) | 34.5 (22–52) | 24.0 (15–37) | <.0001 | 31 (18–44) | 24 (18–38) | .27 |

| Source of infection,c n (%) | ||||||

| Endocarditis | 0 | 15 (7.1) | .004 | 0 | <5 (<10.4) | .24 |

| Skin and soft tissue infections | 38 (33.6) | 46 (21.7) | .02 | 16 (33.3) | 16 (33.3) | 1.0 |

| Osteomyelitis | 13 (11.5) | 26 (12.3) | .84 | 6 (12.5) | 9 (18.8) | .40 |

| Urine | 13 (11.5) | 10 (4.7) | .02 | <5 (<10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | 1.0 |

| Respiratory | 10 (8.9) | 6 (2.8) | .02 | <5 (<10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | 1.0 |

| Surgical site | <5 (<4.4) | 8 (3.8) | .50 | <5 (<10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | .36 |

| Chronic ulcer | 24 (21.2) | 12 (5.7) | <.0001 | 9 (18.8) | 6 (12.5) | .40 |

| Prior healthcare exposures, n (%) | ||||||

| Hospitalization prior 30d | 28 (24.8) | 32 (15.1) | .03 | 16 (33.3) | 12 (25.0) | .37 |

| Nursing home prior 30d | <5 (<4.4) | <5(<2.4) | .61 | <5 (<10.4) | <5 (<10.4) | 1.0 |

| Time to antimicrobial initiation from culture, median days (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–4) | <.0001 | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | .02 |

| Inpatient antimicrobial duration, median days (IQR) | 5 (3–9) | 8.5 (5–14.5) | <.0001 | 5 (3–10) | 10.5 (5–17.5) | .001 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

aCulture-confirmed source of infection.

bWith missing values.

cWithin 48 hours of index culture.

Figure 2.

Clinical Outcomes in Propensity-Matched Nafcillin/Oxacillin/Cefazolin-Treated and Piperacillin/Tazobactam- or Fluoroquinolone-Treated Patients With Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremiaa. aThe propensity score was derived from an unconditional logistic regression model and controlled for the variables listed in Supplementary Table S4. The asterisk symbol denotes that the sample size (n) was too small.

Comorbidity burden was similar between the fluoroquinolone group (moxifloxacin and levofloxacin n = 103) and the preferred treatment group (nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin n = 212; Table 3). However, fluoroquinolone-treated patients were older (69 vs 62.2 years, P < .0001), with higher APACHE scores (32 vs 24, P = .0002). After balancing patient characteristics (nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin n = 32, moxifloxacin/levofloxacin n = 32), no differences in time to mortality were observed between fluoroquinolones and nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin in the propensity-score matched cohort (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.30–5.96; Figure 2). Similar results across all comparison groups were observed in sensitivity analyses adjusted by propensity score quintiles (Supplementary Tables S1 to S3).

Table 3.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Receiving Fluoroquinolones and Nafcillin/Oxacillin/Cefazolin Therapy

| Overall cohort | Propensity-score matched cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Moxifloxacin or levofloxacin (n = 103) | Nafcillin or oxacillin or cefazolin (n = 212) | P value | Moxifloxacin or levofloxacin (n = 32) | Nafcillin or oxacillin or cefazolin (n = 32) | P value |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 69.0 ± 13.7 | 62.2 ± 12.7 | <.0001 | 71.3 ± 13.7 | 67.1 ± 15.3 | .25 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 100 (97.1) | 208 (98.1) | .69 | 32 (100) | 30 (93.8) | .49 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 7.0 | 27.9 ± 7.1 | .30 | 27.0 ± 6.4 | 28.7 ± 7.5 | .34 |

| Obese, n (%) | 27 (26.2) | 76 (35.9) | .09 | 9 (28.1) | 11 (34.4) | .59 |

| Year of treatment | ||||||

| 2002–2009, n (%) | 86 (83.5) | 164 (77.4) | .21 | 28 (87.5) | 26 (81.3) | .49 |

| 2010–2015, n (%) | 17 (16.5) | 48 (22.6) | .21 | <5 (<15.6) | 6 (18.8) | .49 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | .36 | 2.5 (2–5) | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | .55 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Alcoholism | 9 (8.7) | 26 (12.3) | .35 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Cancer | 21 (20.4) | 24 (11.3) | .03 | 6 (18.8) | 7 (21.9) | .76 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 28 (27.2) | 48 (22.6) | .38 | 10 (31.3) | 11 (34.4) | .79 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 14 (13.6) | 21 (9.9) | .33 | 8 (25.0) | <5 (<15.6) | .10 |

| Diabetes mellitus, complicated | 19 (18.5) | 33 (15.6) | .52 | <5 (<15.6) | 6 (18.8) | .49 |

| Diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 32 (31.1) | 72 (34.0) | .61 | 12 (37.5) | 11 (34.4) | .79 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 24 (23.3) | 73 (34.4) | .04 | 11 (34.4) | 12 (37.5) | .79 |

| Dialysis | 7 (6.8) | 30 (14.2) | .06 | <5 (<15.6) | 5 (15.6) | .71 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 39 (37.9) | 32 (15.1) | <.0001 | 10 (31.3) | 6 (18.8) | .25 |

| Coagulopathy | <5 (<4.9) | 8 (3.8) | .28 | 0 | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Coronary heart disease | 34 (33.0) | 74 (34.9) | .74 | 13 (40.6) | 12 (37.5) | .80 |

| Congestive heart failure | 19 (18.5) | 33 (15.6) | .52 | 9 (28.1) | 8 (25.0) | .78 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 39 (37.9) | 50 (23.6) | .01 | 10 (31.3) | 11 (34.4) | .79 |

| Hypertension | 55 (53.4) | 125 (59.0) | .35 | 21 (65.6) | 18 (56.3) | .44 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 9 (8.7) | 27 (12.7) | .30 | 6 (18.8) | 5 (15.6) | .74 |

| Liver disease | 7 (6.8) | 25 (11.8) | .17 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Community onset infection,b n (%) | 76 (73.8) | 153 (72.2) | .76 | 22 (68.8) | 19 (59.4) | .43 |

| Intensive care admission, n (%) | <5 (<4.9) | 11 (5.2) | .56 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | <5 (<4.9) | 15 (7.1) | .26 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| APACHE score,b median (IQR) | 32 (23- 40) | 24 (15–37) | .0002 | 29 (21- 38) | 30 (18–44) | .95 |

| Source of infection,c n (%) | ||||||

| Endocarditis | 0 | 15 (7.1) | .003 | 0 | <5 (<15.6) | .49 |

| Skin and soft tissue infections | 14 (13.6) | 46 (21.7) | .09 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | .67 |

| Osteomyelitis | <5 (<4.9) | 26 (12.3) | .0008 | 0 | <5 (<15.6) | .11 |

| Urine | 19 (18.5) | 10 (4.7) | <.0001 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Respiratory | 22 (21.4) | 6 (2.8) | <.0001 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Surgical site | <5 (<4.9) | 8 (3.8) | .28 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Chronic ulcer | 8 (7.8) | 12 (5.7) | .47 | <5 (<15.6) | <5 (<15.6) | 1.0 |

| Prior healthcare exposures, n (%) | ||||||

| Hospitalization prior 30d | 15 (14.6) | 32 (15.1) | .90 | 6 (18.8) | 5 (15.6) | .74 |

| Nursing home prior 30d | <5 (<4.9) | <5 (<2.4) | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Time to antimicrobial initiation from culture, median days (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 2 (0–4) | <.0001 | 1 (0–3) | 1.5 (0–3.5) | .35 |

| Inpatient antimicrobial duration, median days (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 8.5 (5–14.5) | <.0001 | 5 (4–11.5) | 7 (5–10) | .27 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

aCulture-confirmed source of infection.

bWith missing values.

cWithin 48 hours of index culture.

Discussion

We compared clinical outcomes among patients with MSSA bacteremia exclusively treated with nafcillin/oxacillin, cefazolin, piperacillin/tazobactam, or fluoroquinolone monotherapy during their hospital stay. Overall, our findings are similar to published observational studies, with additional insight regarding the use piperacillin/tazobactam in MSSA bacteremia.

Similar to previously published observational studies, we found that cefazolin effectiveness was not significantly different from antistaphylococcal penicillins (ie, cloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and nafcillin) [4, 5, 7, 8]. In contrast with our findings, several studies have reported improved clinical outcomes with cefazolin [9, 12, 13]. This discrepancy may be due to differences in inclusion criteria surrounding antimicrobial exposure during treatment, including safety as an outcome and a potential inoculum effect. Our study preselected a unique cohort of patients that received only nafcillin/oxacillin, cefazolin, piperacillin/tazobactam, or fluoroquinolones throughout their entire hospitalization.

A retrospective cohort conducted in the VA population compared mortality among MSSA bacteremia patients receiving definitive treatment with nafcillin or oxacillin (n = 2004) versus cefazolin (n = 1163) from 2003–2010 [9]. In contrast to our study, the authors found that mortality was higher in the nafcillin/oxacillin group versus the cefazolin group at 30 days (10% vs 15%; adjusted HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.51–0.78; P < .001), and at 90 days (25% vs 20%; adjusted HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66–0.90; P = .001), concluding that cefazolin may be preferred over nafcillin/oxacillin. The reason for the differences between our study and this study may be a result of the additional antibiotics used during both empiric therapy and concomitant antibiotic use. In this other VA study, definitive therapy was defined as receipt of nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin between 4 and 14 days after culture collection. This treatment definition did not account for empiric therapy or concomitant therapy [9, 11]. Further, it is unclear whether patients receiving as little as 1 day of nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin were included in these treatment groups as duration of therapy was not discussed in the article.

A recently published meta-analysis, which included studies utilizing various definitions of definitive treatment, found that 90-day mortality was less likely in patients who received cefazolin compared with antistaphylococcal penicillins (nafcillin, oxacillin, or cloxacillin; odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41–0.99) [12]. However, the limitations of this meta-analysis significantly affect the applicability of the findings in clinical practice. For example, only 2 of the 7 included studies identified a decreased risk of mortality with cefazolin. One was a small, prospective observational study conducted in South Korea that reported a higher discontinuation rate with nafcillin due to side effects. The second study that found a reduction in mortality with cefazolin was the aforementioned 2003–2010 VA study [9] that utilized broad exposure definitions. This was the largest and most heavily weighted study included in the meta-analysis, accounting for 73.2% of the cefazolin patients and 71.5% of the antistaphylococcal penicillin [12]. A second meta-analysis evaluated 10 studies with similar results and limitations; however, a subgroup analysis excluding the 2010 VA study [9] was performed and a mortality benefit favoring cefazolin over antistaphylococcal penicillins remained (risk ratio [RR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58–0.94) [13]. Our study differed, as we exclusively assessed monotherapy, presuming that empiric and concomitant therapies influence clinical outcomes. Differences in exposure definitions across studies make direct comparisons challenging and contribute to the limited applicability of the meta-analysis results.

Although our study did not evaluate safety, it is important to note that in addition to cefazolin demonstrating greater safety compared with nafcillin/oxacillin in several studies [6, 16–24], nafcillin treatment may be associated with higher adverse events rates than oxacillin [25, 26]. Conversely, increased 30-day all-cause mortality with cefazolin has been reported in high inoculum MSSA infections compared with standard inoculum infections (risk ratio [RR], 2.65; 95% CI, 1.10–6.42; P = .03) [27]. This is likely due to S. aureus beta-lactamase production. Initially recognized in the late 1960s with 4 distinct serotypes (A, B, C, and D) expressing blaZ enzymes [28, 29], type A blaZ appears to have high affinity for deactivating cefazolin via hydrolysis. Although hydrolysis may be overcome in standard infections (ie, 5 × 105 CFU/mL), treatment failure in high-inoculum infections (ie, >5 × 107 CFU/mL) has been described [27, 30, 31]. Therefore, inoculum effect (ie, complicated bacteremia, with foci of infection) should be considered in patients that are not clinically improving or are decompensating while on cefazolin [27, 32]. Additionally, the presence of type A, B, C, and D blaZ enzymes vary geographically and should be considered when selecting an antistaphylococcal penicillin over cefazolin. We only assessed patients without changes in therapy and, therefore, included patients who tolerated monotherapy with nafcillin, oxacillin, cefazolin, piperacillin/tazobactam, or fluoroquinolones without significant adverse effects leading to treatment discontinuation.

Of interest, 30-day mortality was significantly higher for patients receiving piperacillin/tazobactam compared with nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin in our study. Our findings are consistent with a previously published retrospective single-center cohort study evaluating empiric and definitive therapy for MSSA bacteremia among patients receiving a beta-lactam antimicrobial therapy within 48 hours after blood culture collection [33]. Investigators from this non-US–based study identified higher mortality among patients receiving beta-lactams/beta-lactam inhibitors (BLBLIs) empirically for MSSA bacteremia (OR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.23–5.85) [33]. Based on empiric therapy, they observed a mortality benefit in patients initially treated with oxacillin or cefazolin compared with cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime. For definitive therapy, it was concluded that cefazolin was not significantly different from oxacillin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.47–1.77). Overall, their observations indicate that although cefazolin may be a safe and effective alternative to oxacillin, other beta-lactams, including second and third generation cephalosporins and BLBLIs, may be associated with higher mortality. Although conflicting data exist [34, 35], other studies have observed poor outcomes associated with second and third generation cephalosporins [36–38].

A possible explanation for the increased mortality we observed with piperacillin/tazobactam may be due to the inability of tazobactam to induce staphylococcal types A and C beta-lactamases, both of which are associated with elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC), in addition to an inoculum effect [32, 39, 40]. A recent study evaluated 302 MSSA isolates and found increased MICs with increased bacterial inoculum [32]. MICs exceeded susceptibility breakpoints among BLBLIs, including piperacillin/tazobactam, with significant increases in mean MIC between high and standard inocula (high inoculum, 48.14 ± 4.08 vs standard inoculum, 2.04 ± 0.08 mg/L; P < .001). The inoculum effect for piperacillin/tazobactam exposure also is associated with presence of type C blaZ beta-lactamase enzymes 87.8% of the time versus 8.8% non-type C (P < .001) [32]. Type C enzymes bind more tightly to piperacillin/tazobactam than type A enzymes and can lead to a subsequently more pronounced deactivation [40]. Prevalence of type C enzymes are as high as 46%–53% nationally and internationally [31, 41].

Interestingly, we did not observe a difference between nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin when compared with fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin and moxifloxacin). Studies evaluating fluoroquinolones for MSSA bacteremia are limited, and often evaluate MRSA [42, 43], which is not a recommended treatment option [44]. A prospective, randomized, open-label multicenter trial that compared an oral fluoroquinolone (fleroxacin) plus rifampin to standard therapy (parenteral flucoxacillin or vancomycin) for staphylococcal infections (not exclusively MSSA), found that oral treatment was similar to parenteral therapy [43]. Although this may be because fluoroquinolones have excellent oral bioavailability and tissue penetration, the comparator in this study is not a preferred treatment for MSSA [43]. Safety concerns should be considered prior to selecting fluoroquinolones as a treatment for MSSA bacteremia, including the high risk of developing a Clostridiodes difficile infection [45], as well as manufacturer and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-recognized adverse events, including, but not limited to, tendon rupture, aortic rupture, psychiatric effects, and hypoglycemia. Consequently, the use of fluoroquinolones should be avoided when alternative agents are available.

Our study is not without limitations. We only included patients with exposure to 1 antimicrobial agent throughout their entire hospitalization. This is not representative of typical clinical scenarios where changes in treatment occur when moving from empiric to definitive therapy and where combination therapy may be used [46]. In fact, antibiotic treatment may be misclassified in as many as 86% of patients when traditional exposure definitions are used [46]. Therefore, our exposure definition allowed us to attribute clinical outcomes to a single antibiotic, rather than overlooking other antibiotic exposures, including varying periods of combination therapy, overlapping therapy, and changes in therapy, which commonly occurs in other studies. A known limitation of observational studies is the inability to control for all factors that contribute to confounding by indication, as providers might not typically initiate nafcillin or oxacillin therapy empirically. Confounding by comedication is a major concern with existing comparative effectiveness research in infectious diseases. We, therefore, utilized a highly specific exposure definition to overcome this problem. However, because antibiotic monotherapy was not commonly used, sample sizes were low for some of the exposure-outcome associations assessed. This resulted in several wide confidence interval ranges, which affected the ability to detect small differences between groups. Moreover, information on source control, time to blood culture clearance, total duration of therapy, doses used, and routes of administration for fluoroquinolones (ie, intravenous versus oral) were not available. Our findings are supported by other published studies that have concluded cefazolin is similar to antistaphylococcal penicillins, and piperacillin/tazobactam may be sub-optimal to treat MSSA bacteremia [4, 5, 7, 8, 10].

S. aureus bacteremia can metastasize, making it difficult to eradicate and leading to high mortality rates [1, 2]. Our comparative effectiveness study demonstrated similar clinical outcomes between nafcillin, oxacillin, cefazolin, and fluoroquinolones. However, 30-day mortality was higher in patients receiving piperacillin/tazobactam monotherapy. This observed higher mortality may be a result of the beta-lactam inoculum effect providing clinical relevance of this phenomenon previously described by in vitro data [32]. We observed higher mortality rates among patients treated exclusively with piperacillin-tazobactam, suggesting it may not be as effective as monotherapy in MSSA bacteremia. Further studies are warranted to guide provider decisions regarding empiric and definitive therapy in MSSA bacteremia, including the effect of discontinuation of piperacillin-tazobactam as empiric therapy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A.R.C., M.B., J.A.C., K.L., and V.L. were responsible for the conception, study design, protocol development, analysis and interpretation of data, and for preparation and critical revision of the final manuscript. A.R.C., M.B., J.A.C., and V.L. generated data.

Disclaimer. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs.

Financial support. None reported.

Potential conflicts of interest. This work has been supported in part by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veterans Affairs, and with resources and through use of facilities at Providence VA Medical Center. A.R.C. has received research funding from Pfizer, Cubist (Merck), and The Medicines Company. K.L.L. has received research funding as an advisor for Merck; Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc.; Pfizer Pharmaceuticals; Nabriva Therapuetics US, Inc.; Melinta Therapeutics, Inc.; Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals; and Paratek Pharmaceuticals. All other authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Corey GR. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: definitions and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48(Suppl 4):S254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cluff LE, Reynolds RC, Page DL, Breckenridge JL. Staphylococcal bacteremia and altered host resistance. Ann Intern Med 1968; 69:859–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fowler VG Jr, Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. ; S. aureus Endocarditis and Bacteremia Study Group. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:653–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bai AD, Showler A, Burry L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cefazolin versus cloxacillin as definitive antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteraemia: results from a large multicentre cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:1539–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis JS, Turnidge J, Tong S. A large retrospective cohort study of cefazolin compared with flucloxacillin for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018; 52:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee S, Choe PG, Song KH, et al. Is cefazolin inferior to nafcillin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:5122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pollett S, Baxi SM, Rutherford GW, Doernberg SB, Bacchetti P, Chambers HF. Cefazolin versus nafcillin for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in a California tertiary medical center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:4684–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rao SN, Rhodes NJ, Lee BJ, et al. Treatment outcomes with cefazolin versus oxacillin for deep-seated methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:5232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDanel JS, Roghmann MC, Perencevich EN, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cefazolin versus nafcillin or oxacillin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus infections complicated by bacteremia: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schweizer ML, Furuno JP, Harris AD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of nafcillin or cefazolin versus vancomycin in methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bidell MR, Patel N, O’Donnell JN. Optimal treatment of MSSA bacteraemias: a meta-analysis of cefazolin versus antistaphylococcal penicillins. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:2643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rindone JP, Mellen CK. Meta-analysis of trials comparing cefazolin to antistaphylococcal penicillins in the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018; 84:1258–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caffrey AR, Timbrook TT, Noh E, et al. Evidence to support continuation of statin therapy in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: pii: e02228-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Timbrook TT, Caffrey AR, Luther MK, Lopes V, LaPlante KL. Association of higher daptomycin dose (7 mg/kg or Greater) with improved survival in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pharmacotherapy 2018; 38:189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flynt LK, Kenney RM, Zervos MJ, Davis SL. The safety and economic impact of cefazolin versus nafcillin for the treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Infect Dis Ther 2017; 6:225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee B, Tam I, Weigel B 4th, et al. Comparative outcomes of β-lactam antibiotics in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: treatment success, readmissions and antibiotic switches. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:2389–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S, Song KH, Jung SI, et al. ; Korea INfectious Diseases (KIND) study group. Comparative outcomes of cefazolin versus nafcillin for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a prospective multicentre cohort study in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24:152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li J, Echevarria KL, Hughes DW, Cadena JA, Bowling JE, Lewis JS 2nd. Comparison of cefazolin versus oxacillin for treatment of complicated bacteremia caused by methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:5117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li J, Echevarria KL, Traugott KA. β-Lactam therapy for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a comparative review of cefazolin versus antistaphylococcal penicillins. Pharmacotherapy 2017; 37:346–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Monogue ML, Ortwine JK, Wei W, Eljaaly K, Bhavan KP. Nafcillin versus cefazolin for the treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Infect Public Health 2018; 11:727–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah MD, Wardlow LC, Stevenson KB, Coe KE, Reed EE. Clinical outcomes with penicillin versus alternative beta-lactams in the treatment of penicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pharmacotherapy doi: 10.1002/phar.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Youngster I, Shenoy ES, Hooper DC, Nelson SB. Comparative evaluation of the tolerability of cefazolin and nafcillin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus infections in the outpatient setting. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:369–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eljaaly K, Alshehri S, Erstad BL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety of antistaphylococcal penicillins compared to cefazolin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62:e01816-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viehman JA, Oleksiuk LM, Sheridan KR, et al. Adverse events lead to drug discontinuation more commonly among patients who receive nafcillin than among those who receive oxacillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:3090–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Timbrook TT, Sutton J, Spivak E.1407. Disproportionality analysis of safety with nafcillin and oxacillin with the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5(Suppl 1):S433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller WR, Seas C, Carvajal LP, et al. The cefazolin inoculum effect is associated with increased mortality in methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richmond MH. Wild-type variants of exopenicillinase from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J 1965; 94:584–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosdahl VT. Penicillinase production in Staphylococcus aureus strains of clinical importance. Dan Med Bull 1986; 33:175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nannini EC, Singh KV, Murray BE. Relapse of type A β-lactamase-producing Staphylococcus aureus native valve endocarditis during cefazolin therapy: revisiting the issue. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:1194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nannini EC, Stryjewski ME, Singh KV, et al. Inoculum effect with cefazolin among clinical isolates of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: frequency and possible cause of cefazolin treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:3437–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Song KH, Jung SI, Lee S, et al. ; Korea INfectious Diseases (KIND) study group. Inoculum effect of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus against broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019; 38:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paul M, Zemer-Wassercug N, Talker O, et al. Are all beta-lactams similarly effective in the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia? Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:1581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Forsblom E, Ruotsalainen E, Järvinen A. Comparable effectiveness of first week treatment with aHRnti-staphylococcal penicillin versus cephalosporin in methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a propensity-score adjusted retrospective study. PLOS ONE 2016; 11:e0167112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Patel UC, McKissic EL, Kasper D, et al. Outcomes of ceftriaxone use compared to standard of therapy in methicillin susceptible staphylococcal aureus (MSSA) bloodstream infections. Int J Clin Pharm 2014; 36:1282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carr DR, Stiefel U, Bonomo RA, et al. A comparison of cefazolin versus ceftriaxone for the treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in a tertiary care VA medical center. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nissen JL, Skov R, Knudsen JD, et al. Effectiveness of penicillin, dicloxacillin and cefuroxime for penicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a retrospective, propensity-score-adjusted case-control and cohort analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68:1894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rasmussen JB, Knudsen JD, Arpi M, et al. Relative efficacy of cefuroxime versus dicloxacillin as definitive antimicrobial therapy in methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a propensity-score adjusted retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69:506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonfiglio G, Livermore DM. Behaviour of β-lactamase-positive and -negative Staphylococcus aureus isolates in susceptibility tests with piperacillin/tazobactam and other β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. J Antimicrob Chemother 1993; 32:431–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bonfiglio G, Livermore DM. β-Lactamase types amongst Staphylococcus aureus isolates in relation to susceptibility to β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. J Antimicrob Chemother 1994; 33:465–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Richter SS, Doern GV, Heilmann KP, et al. Detection and prevalence of penicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in the United States in 2013. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:812–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ruotsalainen E, Järvinen A, Koivula I, et al. ; Finlevo Study Group. Levofloxacin does not decrease mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia when added to the standard treatment: a prospective and randomized clinical trial of 381 patients. J Intern Med 2006; 259:179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schrenzel J, Harbarth S, Schockmel G, et al. ; Swiss Staphylococcal Study Group. A randomized clinical trial to compare fleroxacin-rifampicin with flucloxacillin or vancomycin for the treatment of staphylococcal infection. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gade ND, Qazi MS. Fluoroquinolone therapy in Staphylococcus aureus infections: where do we stand? J Lab Physicians 2013; 5:109–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McCusker ME, Harris AD, Perencevich E, Roghmann MC. Fluoroquinolone use and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:730–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caffrey AR, Babcock ZR, Lopes VV, Timbrook TT, LaPlante KL. Heterogeneity in the treatment of bloodstream infections identified from antibiotic exposure mapping. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2019; 28:707–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.