Abstract

MicroRNAs are dysregulated in breast cancer. Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2/B1) is a reader of the N(6)-methyladenosine (m6A) mark in primary-miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) and promotes DROSHA processing to precursor-miRNAs (pre-miRNAs). We examined the expression of writers, readers, and erasers of m6A and report that HNRNPA2/B1 expression is higher in tamoxifen-resistant LCC9 breast cancer cells as compared to parental, tamoxifen-sensitive MCF-7 cells. To examine how increased expression of HNRNPA2/B1 affects miRNA expression, HNRNPA2/B1 was transiently overexpressed (~5.4-fold) in MCF-7 cells for whole genome miRNA profiling (miRNA-seq). 148 and 88 miRNAs were up- and down-regulated, respectively, 48 h after transfection and 177 and 172 up- and down-regulated, respectively, 72 h after transfection. MetaCore Enrichment analysis identified progesterone receptor action and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling via miRNA in breast cancer as pathways downstream of the upregulated miRNAs and TGFβ signaling via SMADs and Notch signaling as pathways of the downregulated miRNAs. GO biological processes for mRNA targets of HNRNPA2/B1-regulated miRNAs included response to estradiol and cell-substrate adhesion. qPCR confirmed HNRNPA2B1 downregulation of miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222 and upregulation of miR-1266-5p, miR-1268a, miR-671-3p. Transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 reduced MCF-7 sensitivity to 4-hydroxytamoxifen and fulvestrant, suggesting a role for HNRNPA2/B1 in endocrine-resistance.

Subject terms: miRNAs, Breast cancer

Introduction

The majority of breast tumors (70%) express estrogen receptor α (ERα) which is successfully targeted by adjuvant therapies that increase overall survival1. The current standard adjuvant treatments for patients with ERα+ breast cancer either inhibit ERα activity, e.g., tamoxifen (TAM) for premenopausal women, or block the conversion of androgens to estrogens by aromatase inhibitors (AIs), e.g., letrozole, in postmenopausal women2. Unfortunately, endocrine therapies are limited by the development of acquired endocrine resistance in ~30–40% of initially responsive patients that can occur up to 30 years after primary therapy3,4. A variety of mechanisms have been implicated in TAM-resistance (TAM-R)5,6, including altered microRNA (miRNA) and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) expression7–9. Most miRNAs are transcribed, by RNA polymerase II, either as introns of host genes or as independent genes called primary (pri)-miRNAs10. Pri-miRNAs are processed by the DROSHA-DGCR8 microprocessor complex to precursor (pre)-miRNAs prior to nuclear export11. In the cytoplasm, the double stranded pre-miRNA is unwound by the DICER-TRBP complex to incorporate one strand of the miRNA (called the guide strand) into the RNA induced silencing (RISC) complex containing the catalytic Argonaut proteins, e.g., AGO212. By basepairing with nucleotides in the 3′UTR of target genes within RISC, miRNAs can act as either oncomiRs by reducing protein levels of tumor suppressors or as tumor suppressors by decreasing oncogenic proteins in breast tumors7. The processing of pri-miRNA transcripts is regulated in part by post-transcriptional modifications (PTMs) of pri-miRNA13.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrometry identified N(6)-methyladenosine (m6A) as the most common modification of mRNA and lncRNAs14,15. m6A plays a role in pre-mRNA processing, alternative splicing, nuclear export, stability, and translation16,17 by acting as a ‘conformational marker’ that induces sequence-dependent outcomes in RNA remodeling18. A recent report also identified higher m6A in selected pri-miRNA sequences that corresponded with increased levels of the corresponding mature miRNA in MDA-MB-231 triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells13.

m6A methylation is added by the RNA methyltransferase complex (WTAP, METTL3, METTL14, VIRMA, and RBM15), removed by the dioxygenases FTO and ALKBH5, and recognized by a variety of ‘readers’, including YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and HNRNPA2/B119–21. METTL3 methylation of m6A on pri-miRNAs13 and RNA-dependent interaction of HNRNPA2/B1 with DGCR8, a component of the DROSHA complex, stimulate processing of selected pri-miRNA-m6A to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA)22. HNRNPA2/B1 transcript expression is upregulated in breast tissue of postmenopausal parous women23, but its role in the protective effect of early pregnancy on postmenopausal ERα+ breast cancer is unknown24. HNRNPA2/B1 protein expression was higher in breast tumors compared to normal breast and knockdown of HNRNPA2/B1 inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by causing S phase arrest and apoptosis25.

HNRNPA2 and HNRNPB1 are two splice isoforms transcribed from the same locus but are traditionally treated as a single protein26. HNRNPB1 is a lower abundance (~5%) N-terminal splice variant of the more highly expressed HNRNPA2 isoform and contains an additional 12 aa encoded by exon 227. HNRNPA2/B1 share the remaining protein structure including an RNA-binding domain containing two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) separated by a 15 aa linker and a C-terminal Gly-rich, low complexity region with a prion-like domain (PrLD), RGG box, and Py-motif including M9 nuclear localization signal28. In addition to its recognition of m6A in pri-miRNA and role in RNA splicing and processing29, HNRNPA2/B1 is involved in DNA repair30 and genome stability31.

In MCF-7 ERα+ breast cancer cells, enhanced cross-linking immunoprecipitation (eCLIP) using antibodies specific to HNRNPB1 alone or HNRNPA2/B1 in combination identified 1,472 transcripts bound by both HNRNPB1 and HNRNPA2/B1, 899 transcripts uniquely bound by HNRNPB1, and 479 transcripts uniquely bound by HNRNPA2/B132. HNRNPB1 binding sites revealed a preference for 5′-AGGAAGG-3′ versus 5′-UGGGGA-3′ for HNRNPA2/B132. HNRNPA2/B1 binding peaks were primarily in chromatin samples, consistent with HNRNPA2/B1 binding to nascent transcripts32.

Here we identified HNRNPA2/B1 expression to be higher in LCC9 and LY2 endocrine-resistant cells compared to parental MCF-7 luminal A breast cancer cells. We used miRNA-seq to identify differences in miRNA transcripts in MCF-7 cells when HNRNPA2/B1 is overexpressed and evaluated the pathways and mRNA targets associated with each misregulated miRNA for relevance to breast cancer and endocrine resistance. Progesterone receptor (PR) action in breast cancer and TGFβ signaling via miRNA in breast cancer were identified as pathways downstream of the upregulated miRNAs, and TGFβ signaling via SMADs and activation of Notch signaling were identified as pathways downstream of the downregulated miRNAs. TGFβ signaling, response to estradiol, and cell-substrate adhesion were pathways associated with mRNA targets of the identified miRNAs. Accordingly, overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in MCF-7 cells reduced their sensitivity to 4-hydroxytamoxifen and fulvestrant, indicating that increased HNRNPA2/B1 plays a role in tamoxifen and fulvestrant resistant cell proliferation.

Results and Discussion

Expression of RNA writers, readers, and erasers in breast cancer cells

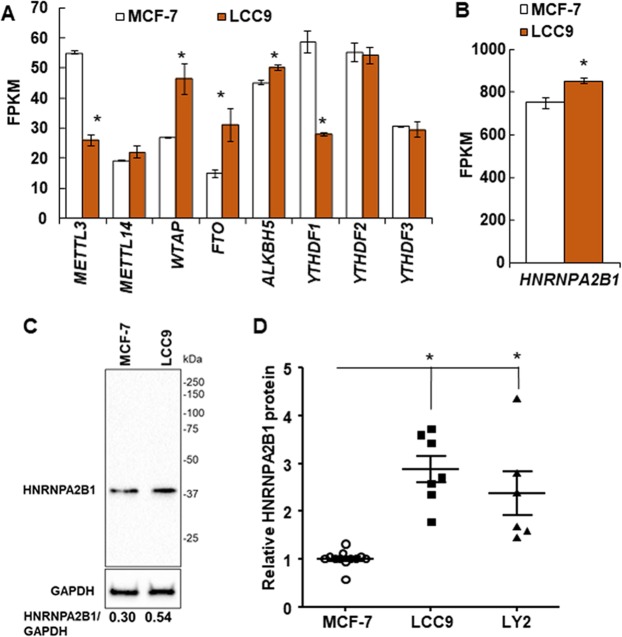

TAM/fulvestrant-resistant LCC9 breast cancer cells have higher levels of expression of diverse miRNAs compared with parental, TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells33. To determine if there are differences in the expression of the genes encoding the readers, writers, and erasers of reversible m6A RNA modification19 between MCF-7 and LCC9 cells, we examined the steady state transcript levels of m6A writers (WTAP, METTL3, and METTL14), readers (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, and HNRNPA2/B1) and erasers (FTO and ALKBH5) in RNA-seq data from our previous RNA-seq study, GEO accession number GSE8162034 (Fig. 1A). The expression of METTL3 and YTHDF1 transcripts was lower in LCC9 than MCF-7 cells whereas WTAP, FTO, ALKBH5, and HNRNPA2/B1 were higher in LCC9 than MCF-7 cells. The possible role of the expression of METTL3, YTHDF1, WTAP, FTO, and HNRNPA2/B1 transcripts in human breast tumors on overall survival was examined using the online tool Kaplan-Meier Plotter35. There was no association of overall survival (OS) for breast cancer patients based on primary tumor expression of METTL3, YTHDF1, or WTAP (Supplementary Fig. 1). Low expression of FTO was associated with lower OS (Supplementary Fig. 2A). However, higher FTO nuclear staining was reported in ER-/PR-/HER2+ breast tumors36. Patients with ER-/PR-/HER2+ breast tumors have ~40% lower disease-free survival compared to women with luminal A breast tumors37. HNRNPA2/B1 transcript expression was higher than any of the other genes examined in the m6A pathway (Fig. 1B). HNRNPA2/B1 protein expression was also ~2.6-fold higher in LCC9 and LY2 cells than MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1C,D, Supplementary Fig. 3). Kaplan-Meier (K-M) survival analysis showed that higher expression of HNRNPA2/B1 is associated with lower OS to ~150 months (Supplementary Fig. 2B). After ~220 months, the black line denoting high HNRNPA2B expression indicates reduced survival for those 3 patients in the K-M plot (Supplementary Fig. 2B). More data are needed to better understand whether low HNRNPA2B1 in the primary tumor predicts reduced OS after ~220 months. Thus, because of the high expression of HNRNPA2B1 at the transcript and protein levels in LCC9 endocrine-resistant cells, its association with lower survival, and its role in increasing pri-miRNA processing22, we selected HNRNPA2B1 for further study.

Figure 1.

Expression of the genes encoding the readers, writers, and erasers of reversible m6A RNA modification. (A,B) Data are from a previous RNA-seq experiment in MCF-7 and LCC9 cells (GEO GSE81620). Data are the average of three replicate experiments +/− SEM. with FPKM = fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads. *P < 0.05 in a two-tailed student’s t test. (C) Representative western blot of HNRNPA2B1 protein expression in WCE from MCF-7 and LCC9 cells. The blot was stripped and reprobed for GAPDH. The numerical values are HNRNPA2B1/GAPDH in these blots. The full-length blot of GAPDH is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1C. (D) Summary of relative HNRNPA2B1 protein expression in LCC9 and LY2 cells compared to MCF-7 parental cells. P < 0.05, One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

miRNA-seq analysis of HNRNPA2/B1-regulated miRNAs in MCF-7 cells

Based on our observation of higher HNRNPA2/B1 in LCC9 compared to MCF-7 cells, we hypothesized that the overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in LCC9 cells promotes processing of pri-miRNAs resulting in increased pre- and mature miRNAs that act on targets and pathways to promote endocrine resistance. We note that HNRNPA2/B1 upregulated miR-99a, miR-125b, and miR-149 in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells22, and we reported higher levels of miR-125b and miR-149, but not miR-99a, in LY2 endocrine resistant breast cancer cells as compared to MCF-7 cells in an earlier study38. To evaluate the effect of increased HNRNPA2/B1 on mature miRNA expression in breast cancer, MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with a control vector for 48 h or an expression vector for HNRNPA2/B1 for 48 or 72 h (Fig. 2A). A limitation of this analysis was that a 72 h control-transfected group was not included. We did not detect differences in control gene (GAPDH) expression between 48 and 72 h control-transfected samples (Supplementary Fig. 3E). However, complete RNA transcriptome analysis of the 72 h control-transfected MCF-7 cells would have been a better control for the 72 h HNRNPA2/B1-transfected cells.

Figure 2.

HNRNPA2B1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells. (A) The ΔCT values for HNRNPA2B1 normalized to 18 S of each of the six samples used for RNA se. MCF-7 cells were transfected with pCDNA3 control or pCDNA-3-HNRNPA2B1. Each point is the mean of triplicate determinations within one qPCR run of these samples. *p < 0.05, One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (B) Western blot for HNRNPA2B1 in MCF-7 cells control-transfected (C) and transfected with HNRNPA2B1 for 48 h. The blot was stripped and reprobed for GAPDH. Values are the HNRNPA2B1/GAPDH in this blot. The full-length blot of GAPDH is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1D. (C) Summary of relative HNRNPA2B1 protein expression in MCF-7 cells transfected for 48 h vs. control, n = mean ± std of 7 biological replicates. P < 0.0004, two-tailed student’s t-test. (D) The heat map represents the miRNAs having a fold-change of ±4. Yellow is upregulated and purple is downregulated (scale at top). Genes were clustered based on similar expression profiles.

The transfection resulted in average ~5 fold increase in HNRNPA2/B1 protein expression (Fig. 2B,C). miRNA was isolated from six replicate experiments 48 or 72 h after HNRNPA2/B1 transfection for global changes in the miRNA transcriptome (miRome). Supplementary Table 1 shows a summary of the sequence analysis of the samples. A heatmap shows the relative consistency of miRNA expression changes in the replicate samples within each comparison and the changes between time after HNRNPA2/B1 transfection (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Three pairwise comparisons were evaluated: 48 h versus control, 72 h versus control, and 72 h versus 48 h. In total, 795 miRNAs were differentially expressed (p ≤ 0.05). 210 (110 up and 100 down) common to both time points, 236 (148 up and 88 down) uniquely at 48 h, and 349 (177 up and 172 down) uniquely at 72 h (Table 1). The identities and values of differentially expressed miRs are shown in Supplementary Tables 2–7 for all comparisons. Note that several miRs are listed twice, due to their coding from multiple gene locations. A heatmap for differentially expressed miRs passing a fold change (FC) threshold of ±4 (Log2FC ±2) in one or more of the comparisons is shown in Fig. 2D.

Table 1.

Comparison of the number of differentially expressed miRNAs using a p-value cutoff of ≤0.05.

| Comparison time transfected with HNRNPA2/B1 | Total DE miRNAs | Upregulated miRNAs | Downregulated miRNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h vs. control | 236 | 148 | 88 |

| 72 h vs. control | 349 | 177 | 172 |

| 72 h vs. 48 h | 433 | 204 | 229 |

miRNAs upregulated in HNRNPA2/B1-transfected MCF-7 cells

Based on previous reports that HNRNPA2B1 increases processing of pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA and mature miRNAs13,22, we hypothesized that HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression would increase levels of miRNAs regulated by m6A in the respective pri-miRNA. We focus only on the miRNAs whose expression was significantly increased in response to HNRNPA2B1 transfection (Fig. 3, Tables 2, 3, Supplementary Table 8). Figure 3 shows that 148 and 177 miRNAs were uniquely increased at 48 and 72 h after HNRNPA2B1 transfection while 110 miRNAs were increased at both time points.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram depicting the number of different and common miRNAs identified as upregulated after transient HNRNPA2B1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells after 48 or 72 h. MetaCore Enrichment by Pathway Maps analysis of DE miRNAs upregulated after 48 h (left, # 1–5) and 72 h (right, 1–6) (both versus control) and those identified in common at 48 and 72 h (below, #1–10).

Table 2.

Fourteen miRNAs were upregulated ≥2.0-fold by transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in MCF-7 cells at 48 and 72 h.

| miRNA | logFC 48 h | logFC 72 h | Comments on role in breast or other cancers | Possible cellular role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1266-3p | 2.77 | 2.94 | High breast tumor levels are a prognostic factor for recurrence-metastasis61 | oncomiR |

| miR-2861 | 2.55 | 2.42 | Higher expression in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43. Increased in papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC) with lymph node metastasis74. | Endocrine-resistance oncomiR |

| miR-4426 | 3.63 | 3.63 | Downregulated in HER2-overexpressing MCF-7 cells75. | |

| miR-4667-5p | 2.25 | 2.25 | Upregulated in HER2-overexpressing MCF-7 cells75 | |

| miR-4739 | 3.03 | 3.03 | Increased by si-CTNNB1 (β-catenin) in gastric cancer (GC) cells, implying a tumor suppressive function in GC76. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-6087 | 2.15 | 2.03 | Downregulated in Adriamycin-resistant MCF-7 cells77. | |

| miR-6088 | 2.63 | 2.42 | Increased by the natural sweetener steviol in HCT-116 cells78. | |

| miR-6762-5p | 2.95 | 2.41 | No references found | |

| miR-6771-5p | 2.49 | 2.26 | No references found | |

| miR-6801-3p | 3.19 | 3.03 | No references found | |

| miR-6803-5p | 2.45 | 2.00 | No references found | |

| miR-6805-3p | 2.79 | 2.40 | Increased by 1 nM progestin R5020 in T47D, BT474, and ZR-75-1 BCa cells, but its role was not examined79 | |

| miR-7107-5p | 2.13 | 3.03 | Higher breast tumor expression levels associated with acquired resistance to chemotherapy63. | oncomiR chemo-resistance |

| miR-762 | 3.23 | 2.41 | promotes BrCa cell proliferation & invasion by targeting IRF780. Directly targets tumor suppressor MEN1 in ovarian cancer and promotes metastasis81. | oncomiR |

miRNAs are sorted by name. The log fold change (logFC) is the average of 6 biological replicate samples and all are statistically significant as indicated by the p ≤ 0.05. The apparent cellular role is based on publications cited related to breast or other cancers as indicated as found in PubMed and Google Scholar.

Table 3.

Sixty miRNAs were upregulated ≥2.0-fold by transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in MCF-7 cells at 48 h, but not at 72 h.

| miRNA | logFC | Comments on role in breast or other cancers | Possible cellular role |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1233-3p | 2.21 | Increased in serum of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients82; represses GDF1583 | oncomiR |

| miR-1279 | 2.55 | No references found | |

| miR-1538 | 2.13 | Identified in serum of neuroblastoma patients84. | |

| miR-212-5p | 2.15 | overexpressed in drug-resistant breast tumors and DOX-resistant MCF-7 cells, targets PTEN85 | oncomiR |

| miR-217 | 1.39 | Expression correlated with ER+ in breast tumors86; higher in TNBC tumors than ER+ tumors, correlated with tumor grade and cancer stage and targeted DACH187; overexpression in MCF-7 cells reduced TAM-sensitivity, reduced E-cadherin, increased invasion and SNAI1 (Snail), and downregulated PTEN88; targets PPARGC1A (PGC-1α) in breast cancer cells89; miR-217 inhibitor blocks docetaxel- or cisplatin-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells90; acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting KLF5 in TNBC cells91. Directly targets SIRT192. | oncomiR TAM-R Tumor suppressor |

| miR-222-5p | 2.59 | Increased in TAM-R cells54; Roles in BCa and TAM-R reviewed7,34,39; high levels are associated with breast tumor stage93. Directly targets SSSCA1 (P27)94. | oncomiR TAM-R |

| miR-302c-3p | 2.60 | Expression correlated with HER2+ in breast tumors86 and development of breast cancer95; Directly targets ESR1 (ERα)96, CCND1 (Cyclin D1)97; BCRP98; MEKK199 | oncomiR |

| miR-3129-3p | 2.57 | Downregulated in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) cell lines and overexpression by lentiviral transduction inhibited EOC cell proliferation in vitro and tumor xenograft growth in vivo100. | Tumor suppressor in EOC |

| miR-3132 | 2.13 | Upregulated in A549, HUVEC and THP-1 cells infected with a hantavirus (Prospect Hill virus)101 | |

| miR-3135a | 2.60 | No references relevant to human cancer were found | |

| miR-3168 | 2.60 | Upregulated by 2 nM paclitaxel treatment in HepG2 cells and thought to play a role in paclitaxel resistance102. | |

| miR-3195 | 2.42 | Related to metastases103 | |

| miR-3610 | 2.58 | Upregulated in BCa tissues104. | |

| miR-3619-3p | 2.20 | High expression in MCF-7 cells and acts as a tumor suppressor by directly targeting PLD (phospholipase D)105; higher expression correlated with tumor relapse in small cell carcinoma of the esophagus106 | tumor suppressor |

| miR-3655 | 3.26 | Upregulated in metastatic melanoma107. | |

| miR-3674 | 2.40 | No references relevant to cancer were found | |

| miR-3919 | 2.60 | No references relevant to cancer were found | |

| miR-3923 | 2.13 | Downregulated in primary breast tumors with lymph node metastasis108. | tumor suppressor |

| miR-3938 | 2.57 | No references relevant to cancer were found | |

| miR-3944-5p | 2.00 | Upregulated by hypoxia in AC16 cardiomyocytes109. | |

| miR-3960 | 2.24 | No references found re. experimental evidence for miR-3960 in cancer. | |

| miR-410-5p | 2.00 | Located in the DLK1-DIO3 genomic region 14q32 that has 2 maternally and 3 paternally expressed genes, 2 lncRNAs, and 53 miRNAs110; high expression favorable in gastric, ovarian, and lung cancer110; miR-410-3p is downregulated in breast tumors and acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting SNAI1111; Suppresses cell growth, migration, and invasion and enhances apoptosis in MCF-7 and T47D cells; directly targets ERLIN2112; Directly targets STAT3113. | tumor suppressor |

| miR-4459 | 2.38 | Upregulated in exosomes derived from chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells114. Identified as specific for ERBB2 breast tumors115. | |

| miR-4463 | 2.60 | Increased in serum of PCOS patients116 | |

| miR-4524b-5p | 3.29 | Increased in salivary glands from Sjögren syndrome patients117. | |

| miR-4532 | 2.07 | Increased expression in MCF-7 CSC-mammospheres- spheroid culture118; Higher in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43 | oncomiR TAM-R |

| miR-4634 | 3.86 | Expression similar in serum from BC patients vs controls119. | |

| miR-4653-5p | 3.86 | None found, but miR-4653-3p was decreased in recurrent/metastatic lesions compared to the matched ER+/PR+ primary breast tumors120 | |

| miR-4657 | 2.13 | Downregulated in metformin-treated cholangiocarcinoma tumor cell lines121. | |

| miR-4665-5p | 2.60 | Upregulated by mechanical compression of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) from invasive ductal carcinomas122. | |

| miR-4679 | 2.13 | Upregulated in VEGF-overexpressing K562 leukemia cells123. | |

| miR-4701-3p | 2.21 | Downregulated in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43. Upregulated in plasma of PTC patients124 | |

| miR-4717-5p | 2.60 | miR-4717-3p was downregulated in the blood of 6 breast cancer patients125. | |

| miR-4723-3p | 2.60 | Downregulated in prostate tumors and acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting ABL1126. | tumor suppressor in PCA |

| miR-4739 | 2.60 | Increased by si-CTNNB1 (β-catenin) in gastric cancer (GC) cells, implying a tumor suppressive function in GC76. | |

| miR-4750-5p | 3.45 | Computational studies identified a binding site for miR-4750-5p in TBC1D17 that has a role in breast cancer, but direct interaction was not verified127. | |

| miR-4752 | 2.60 | No references found | |

| miR-4755-3p | 3.24 | No references relevant to breast or other cancers was found | |

| miR-4763-5p | 2.60 | Increased in blood from multiple myeloma patients128. | |

| miR-4787-5p | 2.98 | Downregulated in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas129. Upregulated in plasma as a specific biomarker of lung squamous cell carcinoma130. | |

| miR-4800-3p | 4.20 | Upregulated in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T TNBC cells compared to MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells131. | |

| miR-500b-3p | 2.45 | Higher in blood from patients with synovial sarcoma132 and prostate cancer (PCA)133 than controls. | |

| miR-507 | 2.57 | Apparent tumor suppressor: lower in breast tumors and cell lines than non-neoplastic tissue and cells and directly targets FLT1134. | tumor suppressor in BC |

| miR-5188 | 2.13 | Downregulated in siHER2-transfected BT474 cells75 | |

| miR-548f-3p | 2.35 | Upregulated in metformin-treated cholangiocarcinoma tumor cell lines121. | |

| miR-548g-3p | 2.39 | Directly targets the stem loop A promoter element within the 5′UTR of dengue virus and represses replication135. | |

| miR-5572 | 2.13 | Identified in minor salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients, in Jurkat cells, and in immortalized human salivary gland cell line pHSG136 | |

| miR-5581-5p | 2.21 | Upregulated in vulvar squamous cell carcinomas137 | |

| miR-587 | 2.60 | Higher expression in chemoresistant colorectal tumors and modulates drug resistance by directly targeting PPP2R1B in colorectal cancer cells138. | oncomiR in colo-rectal cancer |

| miR-595 | 2.66 | Commonly overexpressed in endocrine cancers, including PTC40; tumor promoter in human glioblastoma (GBM) cells by directly targeting SOX741. Downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and directly targets ABCB142. | oncomiR and tumor suppressor |

| miR-6075 | 2.75 | Increased expression in pancreato-biliary cancer139 | |

| miR-6501-5p | 2.41 | No references found | |

| miR-6515-3p | 2.18 | Increased in blood from vitiligo patients140 | |

| miR-6723-5p | 2.26 | Increased by xanthohumol (a hop plant extract that reduces cell viability) treatment of U87 MG glioma cells141. | |

| miR-6741-3p | 2.60 | Upregulated in the blood of Systemic Lupus Erythematous patients with class IV lupus nephritis142. | |

| miR-6762-5p | 2.95 | Identified as a potential target of hsa-circ-0036722, but not experimentally validated143 | |

| miR-6773-5p | 2.53 | Downregulated by cyclosporine A treatment of HK‐2 immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cells144. | |

| miR-6836-3p | 2.21 | Upregulated in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T TNBC cells compared to MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 cells131. | |

| miR-6882-5p | 2.13 | Identified as a biomarker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma145 | |

| miR-6886-3p | 2.58 | Downregulated by the lncRNA HULC in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and directly targets USP22146. | |

| miR-7109-5p | 2.31 | No references found | |

| miR-8079 | 2.13 | No references found |

The miRNAs are sorted by name. The logFC is the average of 6 biological replicate samples and all are statistically significant as indicated. The apparent cellular role is based on publications cited related to breast or other cancers as found in PubMed and Google Scholar. We found published information on 14 of these 60 miRNAs with 8 having oncomiR and 7 had tumor suppressor roles in breast or other cancer.

Fourteen miRNAs were increased by ≥2.0-log fold at both 48 and 72 h (Table 2). Of the six miRNAs on which publications were found, four (miR-1266, miR-2861, miR-7107-5p, and miR-762) have oncogenic, endocrine- or chemo-resistance activities in breast cancer (Table 2). Sixty miRNAs were increased at 48 h, but not 72 h (Table 3, Supplementary Table 8). Of the twenty miRNAs with publications, seven had reported oncomiR functions and six had tumor suppressor functions. HNRNPA2/B1 transfection increased miR-222-5p, which is increased in TAM-R MCF-7 cells, and its role in TAM-R and targets, including ESR1 (ERα) and cell cycle genes, e.g., CDKN1B (P27/KIP1) have been reviewed7,39. While miR-595 has no established role in breast cancer, it has tumor promoter roles in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC)40 and human glioblastoma (GBM) cells41. However, miR-595 acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer42; thus, its role in breast cancer remains to be determined.

Fifty-one miRNAs were increased at 72 h, but were not increased at 48 h (Supplementary Table 8). Of the 17 miRNAs with published information relevant to cancer, 3 miRNAs (miR-4763-3p, miR-4787-5p, and miR-4800-3p) were reported to be higher in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 versus TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells43.

MetaCore analysis was performed on all three groups of upregulated miRNAs (common to 48 and 72 h, unique to 48 h, and unique to 72 h (Fig. 3). Pathways identified included “PR action in breast cancer: stimulation of metastasis” (involving downregulation of miR-29a-3p) and “TGFβ signaling via miRNA in breast cancer” (involving downregulation of miR-21-5p, miR-200a-3p, miR-200a-5p, miR-200c-3p, miR-200c-5p, miR-200b-3p, upregulation of miR-181a-5p) (Fig. 4). miR-200 family members are downregulated in breast cancer and in TAM-R breast cancer cell lines and tumors (reviewed in7,44). The decrease in miR-200 family members would be expected to relieve repression of ZEB1/2 leading to repression of E-cadherin and EMT, an indicator of breast cancer progression and metastasis45. The GO processes identified included “Cellular response to estrogen stimulus” (upregulation of miR-574-5p and miR-466) (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 2). Increased serum of miR-574-5p is a marker of breast cancer46.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram depicting the number of different and common miRNAs identified as downregulated after transient HNRNPA2B1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells after 48 or 72 h. MetaCore Enrichment by Pathway Maps analysis of DE downregulated miRNAs after 48 h and 72 h (both versus control) identified common and unique pathways putatively regulated by the DE miRNAs.

miRNAs downregulated in HNRNPA2/B1-transfected MCF-7 cells

Unexpectedly, we identified 88, 172, and 100 miRNAs downregulated at 48 h, 72 h, and both time points, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). This is the first identification of miRNAs downregulated in response to HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression. Of course, this could be a direct or indirect effect. Another HNRNP family member, HNRNPA1, can either promote or inhibit pri-miRNA processing, resulting in increased mature miR-18a47 and reduced let-7a-1 in HeLa cells48. We did not detect any significant increase in miR-18a nor a decrease in let-7a-1 in HNRNPA2/B1-transfected MCF-7 cells, implying that these two HNRNPs have different targets in different cells.

We focused on those downregulated ≥2.0-log fold: 57 at 48 h, 130 at 72 h, and 18 in common (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 7). Nine of the 18 common downregulated miRNAs had roles in breast cancer, including miR-221-3p and miR-222-3p (both target ESR1) and miR-515-5p and miR-516-5p, which are increased in TAM-R MCF-7 cells (Table 4). Of the 57 miRNAs downregulated at 48 h (Table 5), 26 have reported roles in breast cancer. Some have roles in TAM-R. let-7i and miR-489 are downregulated in TAM-resistant breast cancer cells and miR-101, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-515 are upregulated in TAM-resistant MCF-7 and other breast cancer cells7,39,49. Both miR-29a-3p and miR-29b-3p which reduce TAM-resistant MCF-7 cell (LCC9 and LY2 cell lines) proliferation, migration, and colony formation33 were downregulated by HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression.

Table 4.

Eighteen miRNAs were downregulated by transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in MCF-7 cells at 48 and 72 h.

| miRNA | logFC | Comments on role in breast or other cancers | Possible Cellular role |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1283 | −2.27 | ATF1 rs11169571 variant C, associated with increased colorectal cancer risk, inhibits binding of miR-1283147. Downregulated in plasma from stage IV and stage III melanoma patients148. Overexpressed in malignant Spitz lesions from melanoma tumors149 | |

| miR-221-3p | −1.16 | High expression in breast tumors vs. normal breast150. Higher expression in TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells54 and higher in MDA-MB-231 cells than MCF-7 cells151. Targets ESR1152, BBC3 (PUMA)153, TRPS1154, BIM155, NOTCH3156, TNFAIP3 (A20)157, PARP1158, and is involved in EMT159 | oncomiR |

| miR-222-3p | −0.96 | High expression associates with high tumor stage, Ki-67 staining, luminal B, and HER2 amplification in breast tumors93. Increased in TAM-R BCa cells and targets ESR1, ERBB3 (reviewed in7). | oncomiR |

| miR-224-5p | −2.86 | Higher expression in TNBC than in ER+ /PR+/HER2 breast tumors160. High expression in TNBC is associated with lower OS161. Downregulated in aromatase-resistant BCa cells162. SMAD4 is a direct target163. | |

| miR-4458 | −2.34 | Deregulated in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43 | |

| miR-4724-3p | −2.63 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-4738-5p | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-486-5p | −1.24 | Downregulated in exosomes in serum from BCa patients with recurrence59. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-489-5p | −1.67 | Reduced in BCa tumors164. Metastasis suppressor165. reduced in TAM-resistant MCF-7 cells54. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-5008-3p | −2.63 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-511-5p | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other solid cancers. | |

| miR-515-5p | −3.57 | Suppressed by E2 in MCF-7 cells166, E2-ERα-downregulated and TAM- ERα-upregulated; lower in ER- breast tumors and downregulates oncogenic genes in the WNT-signaling pathway167. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-516a-5p | −2.31 | Increased expression in TAM-R MCF-7 cells168; miR-516a-5p targets MARK4, a regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell motility, in BCa169. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-518c-3p | −3.39 | No reports for breast or other cancers, but upregulated by E2 in MCF-7 cells170. | |

| miR-518d-5p | −2.37 | No reports for BCa. Downregulated by CircRNA8924 that acts as a competitive endogenous RNA of miR-51d-5p and miR-519-5p in cervical cancer171. | |

| miR-520c-5p | −2.37 | miR-520c is oncogenic in TNBC172 | Oncogenic in TNBC |

| miR-526a | −2.37 | Transient overexpression of miR-526a mimics stimulated MCF-7 cell proliferation173. | |

| miR-6850-3p | −2.05 | No reports for breast or other cancers. |

miRNAs are sorted by name. LogFC is the average of 6 biological replicate samples and all are statistically significant as indicated by the p ≤ 0.05. The apparent cellular role is based on publications cited related to breast or other cancers as indicated as found in PubMed and Google Scholar.

Table 5.

Fifty-seven miRNAs were downregulated by transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 in MCF-7 cells at 48 h.

| miRNA | logFC | Comments on role in breast or other cancers is information on breast cancer not identified in PubMed | Apparent Cellular role |

|---|---|---|---|

| let-7f-2-3p | −0.75 | Low let-7f-2 predicts colon cancer progression174; upregulated in renal cancer175. | |

| let-7i-3p | −0.76 | TAM-sensitivity of ZR-75-1 BCa cells was increased by let-7i transfection176. | |

| miR-100-5p | −2.90 | Down-regulated in CSC generated from MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells177; miR-100 inhibits CSC in basal-like breast cancer and low miR-100 is a negative prognostic factor178 | |

| miR-101-3p | −0.61 | miR-101 transcripts on different chromosomes play diverse roles in the diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical outcome of BC179. miR-101-1, closely linked to ER, PR, and HER2, is processed into miR-101-3p and miR-101-5p, while miR-101-2 lower in expression in BC tumors than normal breast tissue, only produces mature miR-101-3p179. AMPK is a verified direct target of miR-101-3p180. Overexpression of miR-101 promotes E2-independent growth and TAM-R of MCF-7 cells181. | Putative oncomiR in BCa (reviewed in7).Tumor suppressor in breast cancer180 |

| miR-101-5p | −1.09 | Downregulated in HCC tumors and is a “potential diagnostic marker” for HCC182 | Putative tumor suppressor |

| miR-1251-5p | −1.36 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-1323 | −3.60 | Higher expression in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma tumors that are resistant to radiotherapy183. Upregulated in radiation-resistant A549 NSCLC cells184 and in radiation-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells185; High expression in cirrhosis-associated HCC correlated with “dismal survival and advanced staging”186 | oncomiR |

| miR-134-3p | −2.37 | Suppresses ovarian cancer stem cell biogenesis by directly targeting RAB27A187 | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-135a-5p | −2.30 | Reported to be highly expressed in breast tumors (n = 20)188; Upregulated by E2 in MCF-7 cells189; Directly targets ESRRA (ERRα)190 and ELK1 and ELK3 oncogenes191. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-138-5p | −1.83 | Upregulated in the circulation of patients with breast cancer, but there was no change observed in the tumor tissue192; Downregulated in breast tumors and lower expression was associated with advanced clinical tumor stage and metastatic disease193; directly targets VIM (vimentin) and inhibits cell invasion, migration, and proliferation in BCa cell lines193; | Tumor suppressor193 |

| miR-145-5p | −1.85 | Induced by p53 and directly targets MYC194 and RPS6KB1 (P70S6K1)195. Overexpression abrogates the oncogenic activity of circZNF609 in BCa cells; further, circZNF609 and miR-145-5p are strongly negatively correlated in breast tumors196. linc01561 was a ceRNA of miR-145-5p in BCa cells197. | |

| miR-17-5p | −0.77 | Higher expression in TNBC versus luminal A invasive breast ductal carcinoma198. Downregulates E2-ERα-regulated gene expression by downregulating coactivator NCOA3 (AIB1, SRC-3) in MCF-7 cells199. Directly targets HBP1 to promote invasion and migration of BCa cells200. Directly targets DR4 and DR5 to inhibit TRAIL-induced apoptosis in BCa cells201. Suppresses TNBC cell proliferation and invasion by targeting ETV1202. Downregulated in exosomes from BCa patients with recurrence59. Directly inhibits translation of NCOA3 (AIB1) in BCa cells199 | Tumor suppressor203; anti-metastatic function in basal breast tumors204; oncomiR in other cancers205 |

| miR-187-3p | −0.91 | Higher expression in sporadic BCa than in tumors from women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations206. Down-regulated in colorectal, prostate, lung, RCC, and HCC207. | |

| miR-193a-3p | −0.82 | Acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting HIC2, HOXC9, PSEN1, LOXL4, ING5, c-KIT, PLAU, MCL, SRSF2, and WT1208. Upregulated in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43. miR-193a gene is silenced by methylation and directly targets GRB7 in ovarian cancer209. Only miR-193a-5p was downregulated in breast tumors whereas no difference was observed in the expression levels of miR-193-3p in BCa versus normal tissues210. Both miR193a-5p and miR-193a-3p repressed MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation by different targets. miR-193a-3p suppressed cell growth by inhibiting CCND1, PLAU, and SEPN1 and inhibited cell motility by suppressing PLAU expression | Tumor suppressor in many cancers. |

| miR-19a-3p | −0.70 | Lower in MCF-7 than MDA-MB-231 cells211. | oncomiR in breast cancer cells212 |

| miR-19b-3p | −0.82 | Expression level was significantly down‐regulated in BCa vs normal breast213. Downregulated in SK-BR-3 cells resistant to the PI3K inhibitor saracatinib and miR-19b-3p directly targets PIK3CA214 | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-20a-5p | −0.64 | Higher in TNBC than luminal A invasive breast ductal cancer198. LncRNA HOTAIR is overexpressed in breast tumors and directly binds downregulates miR-20a-5p215. Directly targets HMGA2215 and RUNX3216. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-26a-1-3p | −1.06 | Expression correlates with ER+/PR+ in breast tumors217. Direct targets include CCNE1, CDC2, and EZH2217; CHD1, GREB1 and KPNA2218, and MCL1219. Downregulated by E2 in MCF-7 cells220. Over-expression inhibited the growth of SKBR3 and BT474 cells221 and of MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF-7 cells222. However, overexpression for ≥ 3 d results in aneuploidy in human BCa cells223. | |

| miR-29a-3p | −0.97 | stimulates migration and invasion; Repressed by MYC, YYI, NFκB, CEBPA and stimulated by p53224. | OncomiR and tumor suppressor |

| miR-29b-3p | −0.71 | Low expression in breast tumors correlates with reduced OS and DFS225. Lower expression in invasive ductal adenocarcinoma versus lobular carcinomas and elevated in ER+ versus ER- breast tumors58.. Expression increased by GATA2 which suppresses MMP9, ANGPTL4, VEGF, and LOX promoting differentiation, blocking EMT to suppress metastasis226. Regulated by S100A7 acting as an oncogene in ER-negative and as a cancer-suppressor in ER-positive BCa cells, with miR-29b being the determining regulatory factor227. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-3125 | −3.38 | No reports for BCa. Lower in glioblastoma tissues as a poor prognostic indicator228. | |

| miR-320e | −0.88 | No reports for breast cancer. Significantly higher expression in stage III colon cancers from patients with recurrence and associated with poorer DFS229. | |

| miR-34b-5p | −2.20 | Downregulated in breast tumors166,230. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-34c-5p | −2.36 | Downregulated in breast tumors231 | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-3591-5p | −2.88 | No reports for BCa. Expression increased after radiation of A549 NSCLC cells and Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 33 (USP33) was a downstream target of miR-3591-5p232. | |

| miR-3663-5p | −2.96 | No reports for BCa. Expression increased in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)233. | |

| miR-3912-3p | −0.72 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-424-5p | −1.18 | Increased in serum of BCa patients with resistance to dovitinib234. Low in basal-like breast tumors235. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-4419a | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-4500 | −2.08 | No reports for BCa, but down regulated in colorectal cancer and downregulates HMGA2236. | |

| miR-4764-3p | −2.37 | Downregulated in HER2-overexpressing MCF-7 cells75. | |

| miR-4767 | −1.63 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-4789-3p | −2.16 | Identified as specific for basal breast tumors115. | |

| miR-4790-3p | −1.66 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-4793-3p | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-488-5p | −2.83 | Down regulated in breast tumors, but upregulated in plasma of patients with recurrent BCa237. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-497-3p | −0.66 | Higher in ER+ Breast tumors and directly targets ERRA238. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-520g-3p | −2.63 | miR-520g is higher in ER-/PR- breast tumors86. Plasma miR-520g expression levels were significantly higher in BC patients with lymph node metastatic disease239. | Oncogenic |

| miR-548ao-3p | −3.79 | Specifically upregulated in TNBC tumors240 | |

| miR-551b-3p | −1.99 | Lower in breast tumors and characterized as a tumor suppressor241. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-5584-5p | −2.63 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-5681a | −2.07 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-5682 | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-5692a | −3.51 | Overexpressed in HCC tumors and knockdown inhibited HCC cell growth and invasion242. | |

| miR-652-5p | −0.60 | Lower in breast tumors versus adjacent normal tissue243. miR-652-3p levels were significantly lower in the serum of BCa patients than that in controls244. | Tumor suppressor |

| miR-659-5p | −1.39 | Upregulated in rectal tumors from smokers245. | |

| miR-6716-3p | −1.61 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-6733-3p | −1.74 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-6794-3p | −2.57 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-6795-3p | −2.90 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-6834-5p | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-6878-5p | −2.37 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-7975 | −2.00 | No reports for breast or other cancers. | |

| miR-934 | −1.46 | Upregulated in breast tumors diagnosed ≤ 5.2 years postpartum in Hispanic women246. | |

| miR-937-3p | −2.17 | No reports for breast or other solid cancers. | |

| miR-944 | −1.57 | Increased by E2 in MCF-7 cells189. Higher in breast tumors and serum versus controls and targets BNIP3247. However, another study reported that miR-944 expression was repressed in breast tumors and cell lines248. miR-944 overexpression inhibited cell migration/invasion and directly targeted SIAH1 and PTP4A1248. miR-944 also inhibits metastasis of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting EMT by targeting MACC1249. | Cisplatin-resistance Tumor suppressors |

| miR-98-3p | −0.78 | Increased by E2 in MCF-7 cells250. Downregulated in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43. Inhibition of endogenous miR-98 in 4T1 mouse BCa cells promoted cell proliferation, survival, tumor growth, invasion, and angiogenesis251. miR-98 directly targets ALK4, MMP11, and HMGA2252. | Tumor suppressor |

miRNAs are sorted by name. LogFC is the average of 6 biological replicate samples and all are statistically significant as indicated by the p ≤ 0.05. The apparent cellular role is based on publications cited related to breast or other cancers as indicated as found in PubMed.

MetaCore pathway analysis identified “TGFβ signaling via SMADs in breast cancer” for the common 18 downregulated miRNAs, as well as “PR action in breast cancer: stimulation of metastasis” in the 48 h and “Activation of Notch signaling in breast cancer” in the 72 h downregulated miRNAs (Fig. 4). MetaCore enrichment analysis by GO processes identified “cellular response to estrogen stimulus (miR-206)” and “response to estrogen” (also miR-206) (Supplementary Fig. 7). E2, and the ER-selective agonist PPT suppressed miR-206 expression in MCF-7 cells50.

Identification of experimentally validated gene targets of the miRNAs differentially expressed in MCF-7 cells transfected with HNRNPA2/B1

The differentially expressed miRNAs were searched against miRTarBase51 for experimentally validated gene targets. Table 6 shows the number of differentially expressed miRNAs and the number of validated gene targets for these miRNAs. Genes identified as targets of the DE miRNAs were used as an input into categoryCompare52 to identify enriched Gene Ontology Biological Processes (GO:BP)52.

Table 6.

Identification of experimentally validated gene targets of the miRNAs differentially expressed in MCF-7 cells transfected with HNRNPA2/B1.

| Comparison time transfected with HNRNPA2/B1 | Total DE miRNAs | Validated Gene Targets from miRTarBase |

|---|---|---|

| 48 h vs. control | 236 | 7859 |

| 72 h vs. control | 349 | 8914 |

| 72 h vs. 48 h | 433 | 10305 |

Processes putatively regulated by the HNRNPA2B1-regulated miRNAs in MCF-7 cells include TGFβ signaling (Fig. 5), which is protective in normal breast epithelium but acts as a tumor promoter after genetic and epigenetic changes involved in breast tumorigenesis accrue45. TGFβ induces EMT in breast cancer cells in a pathway involving tumor suppressor miR-34 family members and we observed miR-34c-5p was downregulated by HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression at 48 h (Supplementary Table 3). Other processes identified as downstream of HNRNPA2B1-regulated miRNAs included response to estrogen/estradiol, stem cell population maintenance, Wnt signaling, regulation of cell junction organization, cellular response to steroid hormone stimulus, JNK/MAPK cascade, and nuclear transport (Fig. 6). Future studies will address which targets in these pathways are downstream of HNRNPA2B1-regulation of miRNA expression and their role in endocrine-resistance.

Figure 5.

Enriched GO:BP (Gene Ontology: Biological Processes) for genes targeted by differentially expressed miRNAs at the indicated times. mRNA targets identified in miRTarBase as validated targets for the differentially expressed miRNAs at each time point were compared to control or the indicated comparison for GO:BP analysis in categoryCompare.

Figure 6.

Enriched GO:BP (Gene Ontology: Biological Processes) for genes targeted by differentially expressed miRNAs at the indicated times. mRNA targets identified in miRTarBase as validated targets for the differentially expressed miRNAs at each time point were compared to control or the indicated comparison for GO:BP analysis in categoryCompare.

qPCR validation of HNRNPA2/B1-downregulated miRNA targets

We selected miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222-3p for validation by qPCR based on their roles in breast cancer and responses to antiestrogen therapies7,33,34,53–56. Because 48 h HNRNPA2B1-transfected MCF-7 cells showed decreased expression of each of these miRNAs (Tables 4 and 5), we expected each miRNA to be decreased in new transient transfection experiments. Indeed, miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222-3p transcript expression was reduced by 48 h of HNRNPA2B1 transfection in MCF-7 cells, whereas transfection with the parental expression vector pcDNA3.1 had no significant effect (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Regulation of miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222-3p by HNRNPA2B1. MCF-7 cells were either non-transfected (control), transfected with pcDNA3.1 parental vector, or an expression vector for HNRNPA2B1 for 48 h. qPCR for (A) miR-29a-3p; (B) miR-29b-3p, and (C) miR-222-3p. Each miRNA was normalized by RNU48. Values are relative expression normalized to control-transfected cells from 11 biological replicate experiments with multiple control and transfected wells in each experiment. Data were analyzed by two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Both miR-29a and miR-29b are considered tumor suppressors in breast cancer and their repression results in in cancer stem cell expansion in vitro57. Progestins repress miR-29a and miR-29b in ER+/PR+ breast cancer cells58 and “PR action in breast cancer: stimulation of metastasis” was identified in MetaCore analysis. Patients with ductal carcinoma and elevated miR-29b levels had a significantly longer disease-free survival (DFS) and lower risk to relapse58. miR-29b-3p was downregulated in exosomes of patients with breast cancer recurrence, suggesting a role for miR-29b-3p in inhibition of breast cancer progression and recurrence59. Downregulation of miR-222-3p is associated with AI-resistance in long-term estrogen-deprived MCF-7 cells60. Since miR-222 represses TGFβ-stimulated breast cancer growth56, HNRNPA2B’s downregulation of miR-222-3p may facilitate TGFβ signaling as identified in the MetaCore analysis. Hence, downregulation of these three miRNAs by HNRNPA2B1 may be involved in development of a TAM-R phenotype and worse prognosis in vivo, although further experiments will be needed to determine the pathways and targets involved.

qPCR validation of HNRNPA2/B1-upregulated miRNA targets

Based on their upregulation on HNRNPA2B1-transfected MCF-7 cells, we performed qPCR to validate increases in miR-1266-5p, miR-1268a, and miR-671-3p in separately HNRNPA2B1-transfected MCF-7 cells (11 biological replicate experiments, Fig. 8). As expected, all three miRNAs were significantly higher in HNRNPA2B1-transfected MCF-7 cells.

Figure 8.

Regulation of miR-1266-5p, miR-1268a, and miR-671-3p by HNRNPA2B1. MCF-7 cells were either non-transfected (control), transfected with pcDNA3.1 parental vector (pcDNA), or an expression vector for HNRNPA2B1 for 48 h. qPCR for (A) miR-1266-5p; (B) miR-1268a, and (C) miR-671-3p. Each miRNA was normalized by RNU48. Values are relative expression normalized to control-transfected cells from 11 biological replicate experiments with multiple control and transfected wells in each experiment. Data were analyzed by two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001.

Expression of miR-1266 was increased in breast tumors showing recurrence or metastasis after TAM treatment with Kaplan-Meir analysis showing that higher miR-1266 was associated with shorter OS and DFS61. This suggests a role for increased miR-1266 in TAM-resistant breast cancer progression. miR-1268a is upregulated in drug-resistant MDA-MB-231 cell lines62,63. We observed and increased in miR-1268a in HNRNPA2B1-transfected MCF-7 cells, but whether this increase is associated with endocrine-resistance in ERα+ breast cancer cells remains to be evaluated.

miR-671-5p was identified as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer, as its expression is lower in invasive breast tumors compared with normal breast. It directly targets FOXM1, and miR-671-5p overexpression inhibits the proliferation and invasion of MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and T47D, but not MCF-7 cells in vitro64. Likewise, miR-671-5p was downregulated in fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells43. Thus, the increase in miR-671-5p with HNRNPA2B1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells might not have the same tumor suppressor properties. Because HNRNAP2B1 caused multiple changes in miRNA expression, it will be necessary to analyze combinations of miRNAs and examine both phenotypic and transcriptomic responses.

Transient overexpression of HNRNPA2/B1 reduces TAM and fulvestrant responses in MCF-7 cells

Since LCC9 TAM-resistant cells have higher HNRNPA2/B1 than parental, TAM-sensitive MCF-7 cells, we examined whether transient transfection of MCF-7 cells with HNRNPA2/B1 would impact cell viability in response to TAM or fulvestrant treatment. HNRNPA2B1 overexpression alone does not positively affect MCF-7 viability. We actually observed a 10–15% reduction in MCF-7 cell viability 24 and 48 h post- transfection (Fig. 9A). However, in response to 4-OHT or fulvestrant treatment, HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression was able to increase cell viability, indicating decreased sensitivity to ER antagonists (Fig. 9B). This response is similar to the increased viability of LCC9 cells treated with 4-OHT and fulvestrant33. These data suggest a role for increased HNRNPA2/B1 expression in endocrine-resistance in MCF-7 cells. Future experiments will be required to examine the precise pathways and the role of the altered miRNAs and their targets in this response. Additional future directions include examination of how HNRNPA2B1 overexpression in MCF-7 cells and knockdown in LCC9 cells affects phenotypes associated with TAM-resistance including cell invasion, migration, clonogenic survival, and examination of mRNA targets/proteins of the pathways identified, particularly TGFβ signaling.

Figure 9.

Effect of transient HNRNPA2B1 cells on MCF-7 cell viability. (A) Results are the Absorbance readings at 490 nm from an MTT assay in which 5,000 MCF-7 cells were plated in OPTI-MEM for 18 h prior to transfection with vector control (pcDNA cont) or HNRNPA2B1 for 24 or 48 h followed by an MTT assay. Each bar is the avg. ± SEM of 4 wells in one experiment. B) MCF-7 cells were transfected with the pcDNA control vector or HNRNPA2B1 for 24 and then treated with vehicle control (DMSO), 100 nM or 1 µM 4-OHT or 100 nM fulvestrant for 48 h followed by an MTT assay. The control was set to 1 for each transfection. Each bar is the avg. ± SEM of 4 wells in one experiment. *p < 0.05 vs. control in both A and B. In (B) **p < 0.05 vs. the same treatment between control vs. HNRNPA2B-transfected cells. Student’s 2-tailed t-test was used for analysis.

Conclusions

The primary goal of this study was to identify the global impact of HNRNPA2/B1 overexpression on the miRNA transcriptome of luminal A MCF-7 breast cancer cells, based on the observation of higher HNRNPA2/B1 in LCC9 endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells. We report the comprehensive miRNA changes after 48 and 72 h of HNRNPA2/B1 transfection. A limitation of this study is that both 48 and 72 h HNRNPAB1-transfected cells were compared to control-transfected MCF-7 cells at 48 h. Time- and direction-specific regulated miRNAs were characterized using the MetaCore GO enrichment analysis algorithm, and PR action in breast cancer and TGFβ signaling via miRNA in breast cancer were identified as pathways downstream of the HNRNA2B1 miRome in MCF-7 cells. HNRNPA2B1-downregualtion of miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222-3p were confirmed by qPCR in separate experiments. Each of these miRNAs has established roles in breast cancer, including the PR action and TGFβ signaling pathways that were identified in MetaCore analysis. Transient overexpression of HNRNPA2B1 in MCF-7 cells abrogated the ability of 4-OHT and fulvestrant to reduce cell growth. These data support a role for increased HNRNPA2B1 in processes contributing to endocrine-resistance in breast cancer.

Methods

Cell culture and treatments

MCF-7 cells were purchased from American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and were used within 9 passages from ATCC. MCF-7 cells were grown as described previously65 prior to transient transfection with pcDNA3.1+C-DYK or pcDNA3.1+C-DYK into which HNRNPA2/B1 was cloned (purchased from GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Opti-MEM® Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The medium was changed from OPTI-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to Modified IMEM (Thermo Fisher) + 10% FBS six hours after transfection. For the 72 h transfected cells, the medium was replaced with fresh medium 48 h post transfection. A total of six biological replicates for each sample were analysed: control, HNRNPA2/B1-transfected for 48 h, and HNRNPA2/B1-transfected for 72 h.

For miRNA-seq

miRNA was isolated from six separate, biological replicate experiments for each sample group (Control, HNRNPA2/B1 48 h, HNRNPA2/B172 h) using the miRNeasy mini kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s directions. The integrity of the miRNA was confirmed using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were prepared using QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Qiagen). cDNA samples were barcoded with QIAseq miRNA NGS ILM IP primers. Adaptor dimers were removed from amplified libraries using QIAseq miRNA NGS beads. The quantity and quality of the library were analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer using the Agilent high sensitivity DNA kit. Pooled library samples were run on an Illumina miSeq to test quantity and quality using the miSeq Reagent Nano Kit V2 300 cycles (Illumina, Foster City, CA). Library and PhIX control (Illumina, Cat. No. FC-110-3001) were denatured and diluted using the standard normalization method to a final concentration of 6 pM. 300 µl of library and 300 µl of PhIX were combined and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq. Based on the miSeq run, the concentration of the libraries was corrected and re-pooled. Sequencing was performed on the University of Louisville Center for Genetics and Molecular Medicine’s (CGeMM) Illumina NextSeq 500 using the NextSeq 500/550 75 cycle High Output Kit v2 (FC-404-2002). Seventy-two single-end raw sequencing files (.fastq) representing three conditions with six biological replicates and four lanes per replicate were downloaded from Illumina’s BaseSpace onto the KBRIN server for analysis. Data were analyzed using miRDeep266 and edgR67.

The sequence reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19). Quality control (QC) of the raw sequence data was performed using FastQC (version 0.10.1)68. The FastQC results indicate quality trimming is not necessary since the minimum quality value for all samples is well above Q30 (1 in 1000 error rate). Preliminary adapter trimming was performed on each of the samples to remove the Qiagen 3′ Adapter sequence with Trimmomatric v0.3369. For all of the samples, a peak around 22 bp was found with a broader peak prior to 22 bp (data not shown). Further examination of the overrepresented full-length sequences show that many of these are from other ncRNA sequences. Furthermore, the mapping rate is similar among replicates of the same samples. Therefore, although the distributions differ, the resulting data appears to be consistent with previous miR reports70. The trimmed sequences were directly aligned to the human hg19 reference genome assembly using mirDeep266. Supplementary Table 1 indicates the number of raw reads, number of reads after trimming, and number of reads successfully aligned for each of the samples. The aligned sequences were then used as inputs into mirSeep2 along with the mirBase71 release 22 mature miRNA and miRNA hairpin sequences. The result is a file containing the number of reads mapping to each of the 2,822 human (hsa) miRs. After quantification, the resulting counts for each miR in each sample were combined into a reads matrix. Using the counts table resulting from the previous step, differentially expressed miRs were determined using edgeR67. Using a p-value cutoff of 0.05, the number of differentially expressed miRs in each comparison is shown in Table 1. A heatmap was constructed for differentially expressed miRs passing a FC threshold of ±4 (Log2FC ± 2) in one or more of the comparisons (Fig. 1). The resulting heatmap is shown with up-regulated genes (treatment vs. control) in red and down-regulated genes in green (Fig. 5). The differentially expressed miRs are shown in Tables 1–4, Supplementary Tables 2, 3 for all comparisons. Several miRs are listed twice, due to their coding from multiple gene locations. The raw data were uploaded in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database as GSE122634.

In silco identification of mRNA targets for miRNAs identified as HNRNPA2/B1-regulated in MCF-7 cells

Experimentally validated mRNA targets for human miRs were downloaded from miRTarBase release 6.172 from http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/download.php which contains 410,620 miRNA-mRNA interacting pairs. The differentially expressed miRs were then searched against miRTarBase for gene targets. Table 5 shows the number of differentially expressed miRs and the number of validated targets for these miRs. Genes identified as targets of the DEG miRNAs were used as an input into categoryCompare [13] to determine enriched Gene Ontology Biological Processes (GO:BP) and KEGG pathways52 (Supplementary Fig. 8).

In silico MetaCore network analysis

Pathway and network analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed in MetaCore version 6.27 (GeneGO, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). For miRNA analysis, RNA was isolated using miRNeasy Mini Kit RNA (Qiagen). RNA concentration and quality was assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit and the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit for RNA (both from ThermoFisher) were used to make cDNA for miRNA and mRNA, respectively. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) HNRNPA2/B1 was performed using TaqMan assays (ThermoFisher). 18S rRNA (ThermoFisher) was used as normalizer. qPCR for miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-222-3p used TaqMan assays and were normalized to RNU6B (ThermoFisher). qPCR was performed using an ABI Viia 7 Real-Time PCR system (LifeTechnologies) with each reaction run in triplicate. The comparative threshold cycle (CT) method was used to determine ΔCT, ΔΔCT, and fold-change relative to control73.

MTT assay

MCF-7 cells were transfected in 6-well plates for 24 h prior to counting and replating (5,000 cells/well) to 96-well plates in phenol red free IMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (CSS-FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were treated with vehicle control (DMS), 100 nM or 1 µM 4-OHT (4-hydroxytamoxifen, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), or 100 nM fulvestrant (ICI 182,780; Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA) for 48 h and cell viability quantified using CellTiter Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA).

Western blot

Whole cell extracts (WCE) were prepared in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with added phosphatase and complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). 40 or 45 µg of WCE protein were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and electroblotted on PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) for western blotting with the following antibodies: HNRNPA2B1 (B1 epitope-specific32) antibody # 18941 from IBL America (Minneapolis, MN USA); GAPDH cat.# sc-365062 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); β-actin (cat. # A5316, Sigma-Aldrich). Bands were visualized using a Bio Rad ChemiDoc MP imager and quantified by UN-SCAN-IT Graph Digitizer Software 7.1 (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT, USA).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For data in which two samples were compared, Student’s two-tailed test was performed. For data in which more than two samples were compared, one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from NIH: R21CA21952 to C.M.K. and C.S.T. and by an internal grant to C.M.K. from the KBRIN Bioinformatics core that supported E.C.R. and is supported by NIH/NIGMS grant P20 GM103436 (Nigel Cooper, PI).

Author Contributions

C.M.K. and K.M.P. performed experiments; C.M.K. designed experiments; E.C.R. performed bioinformatic analysis. C.M.K. performed MetaCore and statistical analyses; C.M.K. wrote the manuscript with editing by C.S.T. and E.C.R.

Data Availability

Raw sequencing data files obtained from our analysis are available at GEO: accession number GSE122634. All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information Files).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45636-8.

References

- 1.Zwart W, Theodorou V, Carroll JS. Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a multidisciplinary challenge. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2011;3:216–230. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmieri C, Patten DK, Januszewski A, Zucchini G, Howell SJ. Breast cancer: Current and future endocrine therapies. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014;382:695–723. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ring A, Dowsett M. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:643–658. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowsett M, Martin L-A, Smith I, Johnston S. Mechanisms of resistance to aromatase inhibitors. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2005;95:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan P, Maximov PY, Curpan RF, Abderrahman B, Jordan VC. The molecular, cellular and clinical consequences of targeting the estrogen receptor following estrogen deprivation therapy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;408:245–263. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke R, Tyson JJ, Dixon JM. Endocrine resistance in breast cancer – An overview and update. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;418(Part 3):220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muluhngwi P, Klinge CM. Roles for miRNAs in endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2015;22:R279–R300. doi: 10.1530/erc-15-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egeland NG, et al. The Role of MicroRNAs as Predictors of Response to Tamoxifen Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:24243–24275. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinge CM. Non-Coding RNAs in Breast Cancer: Intracellular and Intercellular Communication. Non-coding. RNA. 2018;4:40. doi: 10.3390/ncrna4040040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saini HK, Griffiths-Jones S, Enright AJ. Genomic analysis of human microRNA transcripts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:17719–17724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703890104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daugaard I, Hansen TB. Biogenesis and Function of Ago-Associated RNAs. Trends Genet. 2017;33:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hock J, Meister G. The Argonaute protein family. Genome Biol. 2008;9:210. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan T. N6-methyl-adenosine modification in messenger and long non-coding RNA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013;38:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu L, et al. Simultaneous Quantification of Methylated Cytidine and Adenosine in Cellular and Tissue RNA by Nano-Flow Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Coupled with the Stable Isotope-Dilution Method. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:7653–7659. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou S, et al. N6-Methyladenosine: a conformational marker that regulates the substrate specificity of human demethylases FTO and ALKBH5. Scientific reports. 2016;6:25677. doi: 10.1038/srep25677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Licht K, Jantsch MF. Rapid and dynamic transcriptome regulation by RNA editing and RNA modifications. J. Cell Biol. 2016;213:15–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng X, et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 2018;28:507–517. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alarcón CR, et al. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m6A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell. 2015;162:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peri S, et al. Defining the genomic signature of the parous breast. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barton M, Santucci-Pereira J, Russo J. Molecular pathways involved in pregnancy-induced prevention against breast cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:213. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Y, et al. Splicing factor hnRNPA2B1 contributes to tumorigenic potential of breast cancer cells through STAT3 and ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317694318. doi: 10.1177/1010428317694318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burd CG, Swanson MS, Görlach M, Dreyfuss G. Primary structures of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2, B1, and C2 proteins: a diversity of RNA binding proteins is generated by small peptide inserts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1989;86:9788–9792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozu T, Henrich B, Schäfer KP. Structure and expression of the gene (HNRPA2B1) encoding the human hnRNP protein A2/B1. Genomics. 1995;25:365–371. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80035-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu B, et al. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nature. Communications. 2018;9:420. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1977–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haley B, Paunesku T, Protic M, Woloschak GE. Response of heterogeneous ribonuclear proteins (hnRNP) to ionising radiation and their involvement in DNA damage repair. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2009;85:643–655. doi: 10.1080/09553000903009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shkreta Lulzim, Chabot Benoit. The RNA Splicing Response to DNA Damage. Biomolecules. 2015;5(4):2935–2977. doi: 10.3390/biom5042935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen ED, Balas MM, Griffin AM, Roberts JT, Johnson AM. Global Profiling of hnRNP A2/B1-RNA Binding on Chromatin Highlights LncRNA Interactions. RNA Biology. 2018;15:91–913. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1474072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muluhngwi P, et al. Tamoxifen differentially regulates miR-29b-1 and miR-29a expression depending on endocrine-sensitivity in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2017;388:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muluhngwi P, Alizadeh-Rad N, Vittitow SL, Kalbfleisch TS, Klinge CM. The miR-29 transcriptome in endocrine-sensitive and resistant breast cancer cells. Scientific reports. 2017;7:5205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05727-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gyorffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan A, Dang Y, Chen G, Mo Z. Overexpression of the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) in breast cancer and its clinical implications. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13405–13410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prat A, et al. Clinical implications of the intrinsic molecular subtypes of breast cancer. The Breast. 2015;24:S26–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manavalan TT, et al. Differential expression of microRNA expression in tamoxifen-sensitive MCF-7 versus tamoxifen-resistant LY2 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2011;313:26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klinge CM. miRNAs regulated by estrogens, tamoxifen, and endocrine disruptors and their downstream gene targets. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;418:273–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lima CR, Gomes CC, Santos MF. Role of microRNAs in endocrine cancer metastasis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017;456:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hao Y, Zhang S, Sun S, Zhu J, Xiao Y. MiR-595 targeting regulation of SOX7 expression promoted cell proliferation of human glioblastoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016;80:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian S, Zhang M, Chen X, Liu Y, Lou G. MicroRNA-595 sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin by targeting ABCB1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:87091–87099. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Q, et al. Differential microRNA profiles between fulvestrant-resistant and tamoxifen-resistant human breast cancer cells. Anticancer. Drugs. 2018;29:539–548. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klinge CM. Non-coding RNAs: long non-coding RNAs and microRNAs in endocrine-related cancers. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2018;25:R259–R282. doi: 10.1530/erc-17-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulei D, et al. The “good-cop bad-cop” TGF-beta role in breast cancer modulated by non-coding RNAs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2017;1861:1661–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang SK, et al. A Panel of Serum Noncoding RNAs for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Response to Therapy in Patients with Breast Cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:2476–2488. doi: 10.12659/MSM.909453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guil S, Caceres JF. The multifunctional RNA-binding protein hnRNP A1 is required for processing of miR-18a. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:591–596. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michlewski G, Cáceres JF. Post-transcriptional control of miRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2019;25:1–16. doi: 10.1261/rna.068692.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinge C. M. miRNAs and estrogen action. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012;23:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams BD, Furneaux H, White BA. The Micro-Ribonucleic Acid (miRNA) miR-206 Targets the Human Estrogen Receptor-{alpha} (ER{alpha}) and Represses ER{alpha} Messenger RNA and Protein Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;21:1132–1147. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chou Chih-Hung, Chang Nai-Wen, Shrestha Sirjana, Hsu Sheng-Da, Lin Yu-Ling, Lee Wei-Hsiang, Yang Chi-Dung, Hong Hsiao-Chin, Wei Ting-Yen, Tu Siang-Jyun, Tsai Tzi-Ren, Ho Shu-Yi, Jian Ting-Yan, Wu Hsin-Yi, Chen Pin-Rong, Lin Nai-Chieh, Huang Hsin-Tzu, Yang Tzu-Ling, Pai Chung-Yuan, Tai Chun-San, Chen Wen-Liang, Huang Chia-Yen, Liu Chun-Chi, Weng Shun-Long, Liao Kuang-Wen, Hsu Wen-Lian, Huang Hsien-Da. miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;44(D1):D239–D247. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flight RM, et al. categoryCompare, an analytical tool based on feature annotations. Front Genet. 2014;5:98. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz DJ, et al. Transcriptomic response of breast cancer cells to anacardic acid. Scientific reports. 2018;8:8063. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26429-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller TE, et al. MicroRNA-221/222 confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer by targeting p27(Kip1) J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29897–29903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804612200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Leva G, et al. MicroRNA Cluster 221-222 and Estrogen Receptor {alpha} Interactions in Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:706–721. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rao X, Di Leva G, Li M, Fang F, Devlin C, Hartman-Frey C, Burow M E, Ivan M, Croce C M, Nephew K P. MicroRNA-221/222 confers breast cancer fulvestrant resistance by regulating multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2010;30(9):1082–1097. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cittelly DM, et al. Progestin suppression of miR-29 potentiates dedifferentiation of breast cancer cells via KLF4. Oncogene. 2013;32:2555–2564. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]