Abstract

Objectives. To assess whether increasing health aid investments affected public opinion of the United States in recipient populations.

Methods. We linked health aid data from the United States to nationally representative opinion poll surveys from 45 countries conducted between 2002 and 2016. We exploited the abrupt and substantial increase in health aid when the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) were launched to assess unique changes in opinions of the United States following program onset. We also ascertained increased exposure to health aid from the United States by systematically searching for mentions of US health aid programs in popular press.

Results. Favorability ratings of the United States increased within countries in proportion to health aid and were significantly higher after implementation of PEPFAR and PMI. Higher US health aid was associated with more references to that aid in the popular press.

Conclusions. Our study was the first, to our knowledge, to show that US investments in health aid improved the United States’ image abroad.

Public Health Implications. Sustained global health investments may offer important returns to the United States as well as to the recipient populations.

Over the past 20 years, the US government donated more to global health financing than any other country.1 Though its primary purpose is disease alleviation, health aid is often also framed as an investment in international goodwill.2 The putative diplomatic benefits to the United States have been important reasons for the provision of health aid, yet the effect of these investments on United States’ global standing remains largely unknown.2–4 The current US administration has deprioritized foreign aid: the 2018 US budget proposed 23% cuts to health aid.5 If global health investments have promoted the standing of the United States in recipient countries, cutting back on support may hurt not only the recipient populations but also the United States’ stock of “soft power,” or the ability to influence international policy through noncoercive means.6

Here, we used nationally representative data from 45 countries collected between 2002 and 2016 to explore the hypothesis that health aid investments benefitted the United States in the form of improved public opinion in recipient countries. We also tested whether health aid’s association with public opinion is unique by assessing whether aid to other sectors also affected public opinion.

Most US health aid supports specific health focus areas, with HIV, malaria, and maternal and child health programs constituting the largest areas of investment.1 Although this focused approach to global health financing has drawn criticism, its unprecedented scale also made it a uniquely visible engagement.7,8 The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched in 2003, has arguably become the dominant organization supporting the global response to HIV/AIDS.3 Similarly, the US President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), launched in 2005, became one of the main funders of malaria control.9 These large and successful programs have been addressing high-burden diseases,10,11 and their activities are visible to recipient populations. The unprecedented scale yet focused scope of US health aid provides an opportunity to test its effect on public opinion.

In our analysis, we examined the extent to which US health investments in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have been followed by improved perceptions of the United States among recipient populations. One previous study found that PEPFAR improved the reputation of US leadership.12 However, this study only examined the short-term impact of PEPFAR by using data from 2007 to 2010. To our knowledge, no study to date has examined the long-run effect of health aid on the national reputation of the United States, using a longer panel of data that takes into account the rapid increase in health aid that occurred in the first decade of the 21st century.1 At a time when political sentiment turns inward and US commitment to global health is ebbing, understanding the impact of health investments on US interests abroad is particularly important.

METHODS

In our study, we used population-representative opinion poll data collected in 45 countries from 2002 to 2016 to test the hypothesis that increasing investments in health led to improved public opinion of the United States in recipient populations. We tested whether the relationship between health aid and public opinion of the United States was unique from aid allocated to other sectors by including disbursements to other major aid categories in our models. We also tested whether public opinions of the United States changed significantly after the implementation of PEFPAR and PMI. Finally, we explored the mechanism through which increasing health aid may have affected public perception of the United States by testing whether references to US aid programs increased in frequency and sentiment in local newspapers.

Public Opinion Surveys

We obtained 258 nationally representative Global Attitudes Surveys, based on interviews with more than 260 000 respondents, conducted by the Pew Research Center in 45 LMICs between 2002 and 2016.13 Countries were defined as low- or middle-income according to the World Bank’s definition.14 Pew surveys are conducted annually, but not all countries are surveyed at every round; they are comparable between countries and over time. The surveys use 2-stage sampling design that accounts for unequal probability of selection and socio-demographic distribution. Adult participants (aged ≥ 18 years) were asked to rate their opinion of the United States on a 4-point Likert scale, from “very unfavorable” to “very favorable.” In the main analyses, our outcomes were (1) an indicator for very favorable opinion of the United States and (2) the proportion of respondents indicating very favorable opinion of the United States (additional details about the survey and outcomes are in Appendix A, Section 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Annual Foreign Aid Disbursement Data

We obtained annual disbursement data from the Foreign Aid Explorer, a US government panel data set that tracks aid distributed through more than 70 US government agencies, broken down by recipient country, year, and aid sector.15 Our analysis focused on the top 5 largest sectors in terms of average annual disbursements, in constant 2016 US dollars. The main explanatory variable was a continuous measure of disbursements for health and population, or aid supporting services related to infectious disease control, noncommunicable diseases, basic nutrition, mental health, and reproductive health. Other aid sectors included governance (institution building, elections, legal and judicial development), humanitarian (emergency food, shelter, clothing), infrastructure (energy, transport and storage, telecommunications), and military or peacekeeping.16 We used the measures of aid disbursements for sectors other than health as negative controls.17 In other words, we tested the hypothesis that aid to these 4 sectors would have a null (or small) effect on public opinion because of its political or security focus or less visible presence in recipient countries. For example, exposure to programs that promote judicial development or build energy grids may have less influence on public perceptions than aid that involves direct interactions with recipients, such as receiving medical care, obtaining a bed net, or participating in a vaccination campaign.

Bilateral Aid Programs

We also defined binary indicators for PEPFAR- and PMI-focus countries. PEPFAR was implemented in 7 of our study countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam). PMI was operating in 9 of our study countries (Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda). PEPFAR started implementation in 2004, and PMI launched gradually between 2006 and 2011, starting in 3 countries (Angola, Tanzania, and Uganda). PEPFAR and PMI indicators reflected the different timing of program implementation.

Statistical Analysis

We began by examining bivariate associations between the proportion of respondents who had a very favorable opinion of the United States and the amount of aid disbursed toward health (and, separately, the other sectors) in a given country and year.

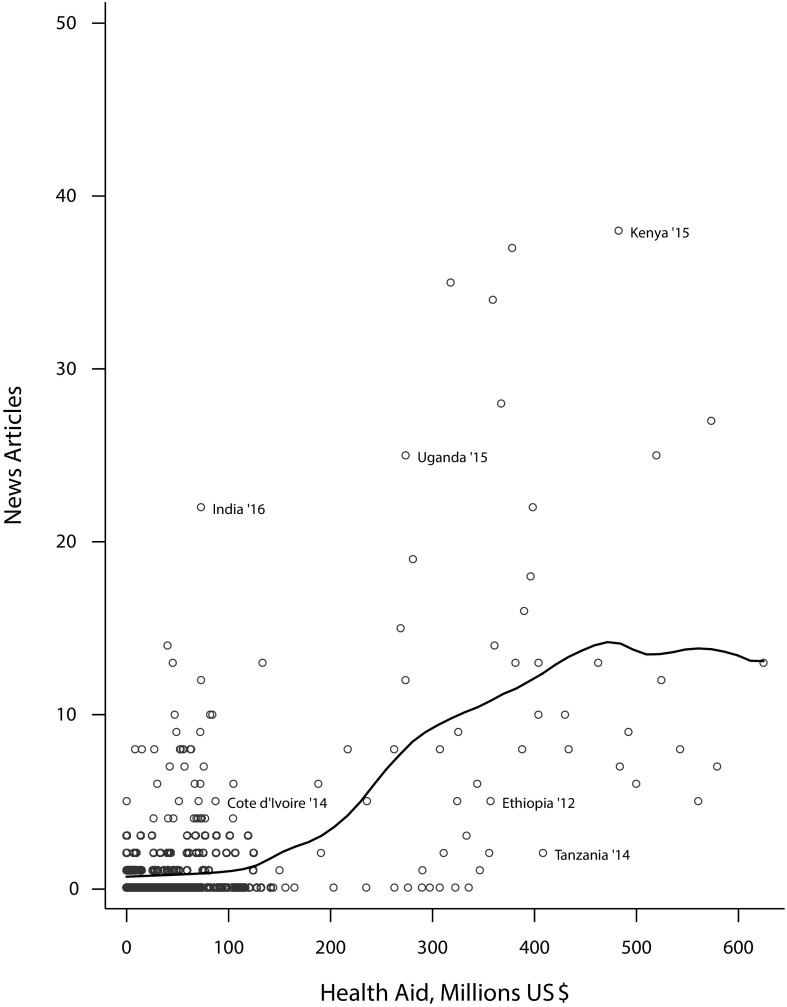

Next, we fitted the linear regression model specified in Equation 1:

|

where Yijt was a binary indicator set to 1 if respondent i in country j in year t had a very favorable opinion of the United States. The key explanatory variable was UShealthaid_deciles, a vector of indicators that ranked health aid disbursements in each country and year into deciles, from lowest level (1st decile) to highest level (10th decile). We adjusted models for aid to other sectors (governance, infrastructure, humanitarian, and military or peacekeeping), also in deciles. Aid disbursements were in deciles to address their nonlinear relationship with opinion of the United States, highly skewed distribution, and uneven scales of disbursements to the 5 categories.

Xi was a vector of individual-level covariates (age and gender), and Zjt was a vector of time-varying country-level covariates from the World Bank: logged gross national income (GNI) per capita, total population, and mobile phone ownership.18 αj was a set of country indicators, and γt was the full set of year indicators. We then refitted the regression model by using country–year data, excluding Xi, or the person-level covariates (Appendix A, Equation B).

We also tested the impact of an additional hundred million dollars in aid by fitting a model with the continuous measures of disbursements and quadratic terms to account for the nonlinear relationship of aid and opinion of the United States (Appendix A, Equation C). Finally, we used difference-in-differences models to evaluate whether opinion of the United States improved more after implementation of PMI and PEPFAR in focus counties (Appendix A, Equations D and E). These models included an indicator for PEPFAR (PMI) recipients, an indicator for postimplementation years, a cross-product of these terms (the difference-in-differences estimator), and were adjusted for the covariates defined previously.

All models included survey weights, and standard errors were clustered at the country level to relax the assumption of independently and identically distributed error terms.19 We set statistical significance at the α = 0.05 level with 2-sided tests. We conducted analysis with Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

News Media and Exposure to US Aid Programs

We constructed a corpus of news stories that mentioned PEPFAR or PMI by crawling through online archives of the top 3 newspapers by circulation in each study country.20,21 Our algorithm searched through articles in various languages, dating back to 2002 (details in Appendix A, Section 3.1). We scraped all articles that mentioned PEPFAR or PMI (search terms in Appendix A, Table A) and performed data cleaning procedures to ensure we excluded duplicate articles or directory pages from our data set. We then used a natural language processing algorithm22 to calculate sentiment scores based on how many positive or negative adjectives were used in the news stories (additional details in Appendix A, Section 3.3). The sentiment scores ranged from −1.0 (very negative) to +1.0 (very positive). Next, we collapsed the number of articles and sentiment scores to country–year level to combine the news data set with the health aid data set. In the cases where we found no articles that met our search criteria, we assigned those country–year observations a frequency of zero articles. Finally, we assessed the relationship between the frequency and sentiment of the articles and the level of health aid disbursements. We used models similar to our main country–year specifications, substituting frequency and sentiment of articles for opinion of the United States as the outcome and focusing on health aid as the explanatory variable of interest (Appendix A, Equation F).

Sensitivity Analyses

To test the effect of having both PMI and PEPFAR on the opinion of the United States, we fitted a difference-in-differences-in-differences model in which the “post-PMI” and “post-PEPFAR” terms were interacted. We also analyzed trends in public opinion of the United States and health aid before and after 2009, when a change in US administrations occurred. We made sure that none of the study countries were outliers by excluding each individual country from the models. We also checked whether the difference-in-differences results were robust to restricting the sample to countries that were surveyed at least once before and after PMI and PEPFAR implementation. We tested using alternative years as the threshold for specifying “post-PMI” indicator. Finally, we tested alternative model specifications, including ordered logistic regression for ordered responses and logistic regression for binary responses.

RESULTS

We used all available Pew Global Attitudes Surveys conducted in LMICs between 2002 and 2016.14 Our sample included 266 679 survey respondents from 45 countries, 36 385 of whom lived in 7 PEPFAR focus countries (Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam had pre–post data; Ethiopia only had data from the postimplementation period) and 37 329 in 9 PMI focus countries (Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda had pre–post data; Angola only had pre-PMI data; Ethiopia only had post-PMI data). A full list of the number of surveys per country and the years in which surveys were conducted are in Appendix A, Table B. A summary of the number of surveys conducted before and after PEPFAR and PMI implementation is in Appendix A, Table C. The average country was surveyed 6 times (range = 1–14 rounds) and included 1156 participants (range = 500–4029). The average age of participants was 38 years (range = 18–77 years), and 49% of participants were women.

On average, the United States allocated most foreign aid in the 45 study countries toward military and peacekeeping aid (Appendix A, Table D), followed by health aid. Health aid allocations were significantly higher in PEPFAR- and PMI-focus countries than in comparison countries. PEPFAR accounted for 48% and PMI for 9% of US health aid portfolio in 2018.23 Appendix A, Figure A displays average aid disbursements in the top 5 categories by study country and geographic region.

Higher Health Aid Investments and Opinions of the United States

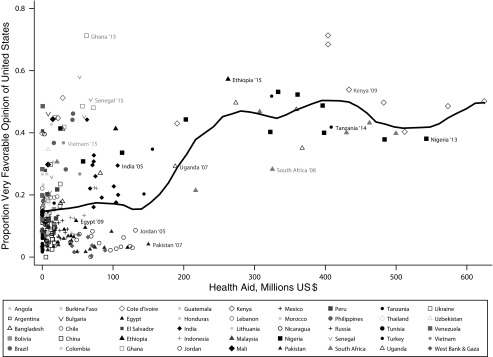

We found a positive association between US health investments and the probability of very favorable opinion of the United States (Figure 1): as health aid increased in study countries, so did the opinion of United States, both in sub-Saharan Africa (where ratings of the United States were generally highest) and globally. When we examined the association between very favorable opinion of the United States and disbursements to other sectors, we found either no clear association or negative association (Appendix A, Figures B–E).

FIGURE 1—

Association Between Health Aid (in Millions) and the Probability of “Very Favorable” Opinion of the United States: 45 Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 2002–2016

Note. Line represents nonparametric kernel-weighted local polynomial regression fit (with Epanechnikov kernels and zero degree polynomials for local mean smoothing). Each marker represents health aid donations to a given country and year (x-axis) and the corresponding proportion of respondents in that country and year who had a very favorable opinion of the United States (y-axis). Labels for select countries are displayed as reference examples; legend displays full list of markers and countries.

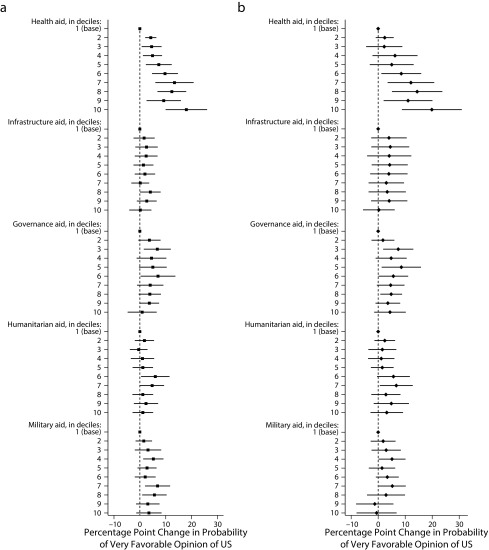

Figure 2 displays percentage point changes in probability of a very favorable opinion of the United States as a function of health aid disbursements (in deciles), adjusted for disbursements to other sectors (also in deciles), and other covariates. Higher investments in health were associated with improved favorability ratings of the United States. Probability of very favorable opinion of the United States was 18.0 percentage points higher (95% confidence interval [CI] = 10.0, 26.0) in the countries and years when US donations were in the top decile of health aid compared with countries and years in the lowest decile of health aid. In contrast, higher investments in governance, infrastructure, humanitarian, and military aid were not associated with better opinion of United States.

FIGURE 2—

Association of Health Aid Disbursements With Higher Probability of “Very Favorable” Opinion of United States at the (a) Individual Level and (b) Country Level: 45 Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 2002–2016

Note. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals obtained from multivariable regression models that included aid to all 5 sectors (in deciles), logged gross national income per capita, total population size, mobile phone ownership, and country and year fixed effects. Individual-level models were also adjusted for age and gender and were weighted by the probability of respondents being selected for the survey. Individual-level model based on responses from 266 679 individuals. Aggregate-level model based on 258 country–year observations. Standard errors were clustered at country level (n = 45).

In models with continuous measures of aid, an additional hundred million dollars in health aid was associated with a 5.7 percentage point increase (95% CI = 1.6, 9.8) in the probability of a very favorable opinion (Appendix A, Figure F).

Effect of Bilateral Aid on Opinions of the United States

The average probability of a very favorable opinion of the United States increased by 6.3 percentage points (95% CI = 0.4, 12.1) in PEPFAR-focus countries following program implementation (Table 1). After implementation of PMI, the average probability of a very favorable opinion of the United States increased by 10.8 percentage points (95% CI = 2.5, 19.1).

TABLE 1—

More Favorable Opinion of United States After Implementation of PEPFAR and PMI: 45 Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 2002–2016

| Effect on Probability of “Very Favorable” Opinion of the United States |

||

| PEPFAR | PMI | |

| Individual-level data | ||

| DD estimate, %∆ (95% CI) | 6.3 (0.4, 12.1) | 10.8 (2.5, 19.1) |

| Mean (pre, control) | 16.1 | 13.9 |

| No. respondents | 266 679 | 266 679 |

| Country-level data | ||

| DD estimate, %∆ (95% CI) | 6.6 (0.0, 13.2) | 11.2 (3.4, 18.9) |

| Mean (pre, control) | 16.6 | 13.9 |

| No. country–wave observations | 258 | 258 |

Note. %∆ = percentage point change; CI = confidence interval; DD = difference-in-differences; PEPFAR = President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; PMI = President’s Malaria Initiative. Effect of PEPFAR (PMI) represents the difference-in-differences estimators or the percentage point change in the probability of having a “very favorable” opinion of United States after introduction of the program in focus countries. All least squares regression models also included PEPFAR (PMI) indicators to adjust for baseline differences between recipient and nonrecipient countries, post- indicators to account for underlying time trends from before to after intervention, logged gross national income per capita, total population size, mobile phone ownership, and year and country fixed effects. Individual-level models also adjusted for age and gender of respondent and were weighted by the probability of respondents being selected for the survey. CIs were calculated by using standard errors clustered at country level (n = 45).

News Analysis

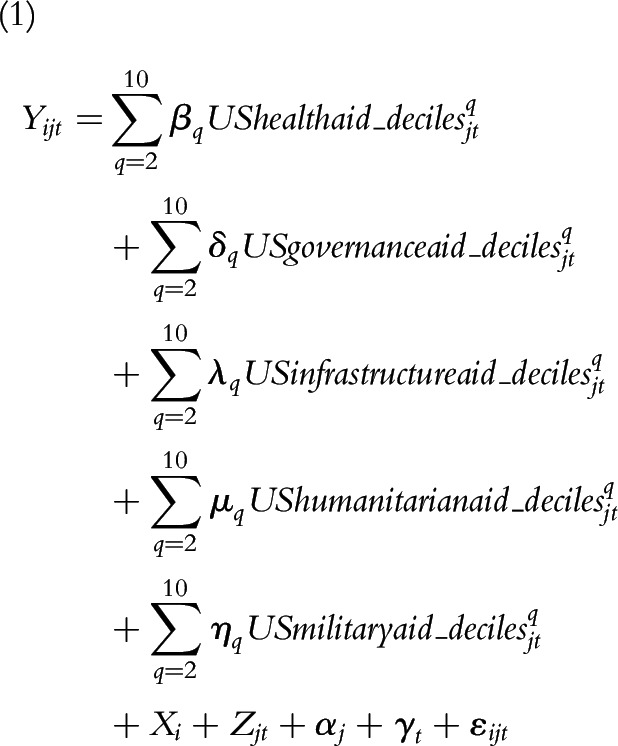

We searched through online archives of 135 widely circulated newspapers in the 45 study countries between 2002 and 2016. We found 1098 articles published that mentioned PEPFAR (n = 888), PMI (n = 172), or both (n = 38). The first article that mentioned PEPFAR was published in 2003 in South Africa, after which the number of articles increased gradually to 8 articles in 2004, 79 articles in 2010, and 218 articles in 2016. Thirty-four countries had at least 1 article published about PEPFAR or PMI, including 23 comparison countries (Appendix A, Table E). The majority of the articles had positive (> 0) sentiment scores. After we collapsed the data to country–year level, we found an average sum of 1.4 articles (range = 0–69) and an average sum of sentiment scores of 0.53 (range = −0.5–4.0). Higher US donations for health were associated with more news articles and more positive sentiment of stories that mentioned the HIV and malaria control programs (Figure 3; Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). An additional hundred million dollars in health aid was associated with approximately 3.1 more articles per year (95% CI = 2.67, 3.50) and 0.22 points higher polarity score (95% CI= 0.07, 0.36; Appendix A, Table F). PEPFAR and PMI were mentioned more frequently in recipient than comparison countries (Appendix A, Table G).

FIGURE 3—

Association of Health Aid Disbursements With Stories Published in Popular Press That Mentioned PMI or PEPFAR by Frequency: 45 Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 2002–2016

Note. PEPFAR = President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; PMI = President’s Malaria Initiative. Local mean smoothing regression of the frequency and sentiment of news stories as a function of US donations for health in a given country and year. Left panel shows the sum of articles published in a given country and year. Right panel shows the sum of sentiment scores of news stories published in a given country and year. Labels for select country–year observations are displayed as reference examples. Articles were scraped from online archives of 135 newspapers in 45 study countries, collapsed at country–year level, and combined with annual foreign aid disbursement data from the Foreign Aid Explorer. Local polynomial regression was fitted with Epanechnikov kernels and zero degree polynomials for local mean smoothing. Appendix B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows association by sentiment.

Sensitivity Analysis

We found an additional improvement in the opinion of the United States in countries that received both PMI and PEPFAR funding (Appendix A, Table H). The probability of a very favorable opinion of the United States increased by an additional 6.6 percentage points (95% CI = −0.3, 13.5; P = .059) in countries that received both PMI and PEPFAR funding, over and above the 12.1 percentage point increase in countries that only received PEPFAR (95% CI = 6.2, 18.0) and 22.7 percentage point increase in countries that only received PMI (95% CI = 12.6, 32.8) after we adjusted for all other covariates. We also found that the positive association between health aid and opinion of the United States existed during the George W. Bush (2002–2008) and Barack Obama (2009–2016) administrations (Appendix A, Figure G).

We confirmed that no individual countries were driving the results by excluding each country from analysis (Appendix A, Figure H and Table I). Results were robust to restricting the sample to the 31 countries that were observed at least once before and after program implementation (Appendix A, Table J). We also tested alternative definitions of the post-PMI variable. PMI was gradually scaled up from 2006 to 2011 (8 out of the 9 PMI-recipient countries in our sample implemented the program by 2008). We found no difference in findings when we varied the “post-” year from 2006 to 2009 (Appendix A, Table K). Results were also robust to alternative model specifications, including ordered logistic regression for ordered responses and logistic regression for binary outcomes (Appendix A, Figures I, J, and K).

DISCUSSION

We found that health aid was independently and consistently associated with more favorable attitudes toward the United States among recipient populations. This effect was present between countries, within countries, and in difference-in-differences models. Invariably, higher health aid investments were associated with greater improvements in favorability. The magnitude of this effect was substantial: about a 6 percentage point increase in highly favorable opinion of the United States per additional hundred million dollars in health aid within recipient countries or a roughly 18 percentage point increase from lowest to highest decile of US health donations in a given year. Aid allocated to other sectors did not have a discernable effect on attitudes toward the United States.

Our work was guided by the theory that health aid is uniquely positioned to sway public opinion because of its visibility, sustainability, and effectiveness in addressing salient health problems. Exposure to US programs could occur through interaction with program services, hearing or reading stories about the programs, or through observation of plaques, logos, and billboards that promote US investments in local health systems. To our knowledge, we provide the first empirical evidence that the increasing presence of US-sponsored health programs can be detected in articles published in local news media. We found a relatively large volume of articles that mentioned PEPFAR and PMI programs in widely circulated newspapers, and that the mentions and sentiment of stories about these programs increased substantially in countries and years when US health donations were higher. Such reminders of US investments in LMICs appear to have positively influenced how the recipient populations perceive the United States.

Health aid has been theorized to create “soft power,”6 yet empirical evidence on this topic is very limited.2–4,24 The study mentioned in the introduction found that a doubling of per capita PEPFAR spending was associated with 20% to 23% higher approval of US presidents between 2007 and 2010.12 Our study improves upon these findings by using data on health aid broadly, from before and after PEPFAR implementation, and on favorability of the United States as a whole. The last point is important because sentiment toward the United States as a whole may transcend the opinion of US leaders, whose personalities and political skills may sway favorability ratings independent of the more stable attitudes toward a nation. Our sensitivity analysis indicates that health aid was associated with improved perceptions of the United States during both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations.

We found that the probability of respondents having a very favorable opinion of the United States increased significantly after introduction of PEPFAR and PMI. These findings are important in view of the severe cuts proposed to PEPFAR and PMI budgets, which could lead to excess disease burden and mortality from HIV and malaria.25,26 Aside from the clear humanitarian merits of programs such as PMI and PEPFAR, our study shows that further global health investments also generate good will toward the United States. Sustained funding levels have the potential to not only continue the global health community on the path to disease control and elimination but also foster the closer ties that have been built between United States and recipient nations.

Limitations

Although we aimed to assess the impact of foreign aid on public opinion of the United States by using robust and conservative methods, we cannot definitively preclude the possibility that there is some unmeasured confounding in our study. To limit bias, we included year indicators (to address shifts in opinions of the United States that occurred over time independently of US foreign aid policies) and country indicators (to account for time-invariant differences between countries). We also made use of the natural experiments created by the implementation of PEPFAR and PMI to show preferential shifting of opinion of the United States in recipient versus comparison countries.

Pew Research Center conducts Global Attitude Surveys annually, but not all countries are surveyed at each round. Our study would have been strengthened if our sample included more countries over time, especially before PEPFAR and PMI implementation. Nonetheless, our findings are generalizable given the large representation of nations from all world regions and a substantial number of PEPFAR and PMI recipient nations.

We conducted sentiment analysis by using an algorithm that assigned a polarity score based on text of the entire article rather than specific mentions of US health programs. Future studies should explore algorithms that may be capable of analyzing words in close proximity of the study keywords.

Public Health Implications

For the past 15 years, the United States has provided more health aid than any other country, which has significantly contributed to reduced disease burden, increased life expectancy, and improved employment in recipient countries.10,11,26,27 Proposed cuts to health aid could have a significant impact on some of the most successful US foreign aid programs, reducing the PEPFAR budget by $860 million dollars (–18%) and the PMI budget by $331 (–44%).28 Our study provides evidence in support of continued health aid investments by showing that donations for health have also provided important returns to the United States. Cutting back on global health support may not only hurt the populations in recipient countries, as has been estimated by scholars and policy experts,25,26 but also offset the gains to the United States’ image that its leadership and generosity have cultivated. Although the United States is the largest aid provider in absolute terms, this generosity has historically constituted less than 1% of its gross domestic product. Our results suggest that the dollars invested in health aid offer good value for money. That is, the relatively low investment in health aid (in terms of gross domestic product) has provided the United States with large returns in the form of improved public perceptions, which may advance the US government’s ability to negotiate international policies that are aligned with US priorities and preferences. Evidence from our study provides support for providing health aid as a tool for lowering disease burden in developing countries and a form of prioritizing US interests.

Conclusions

Our study was the first, to our knowledge, to explore the role of US donations for health on shaping America’s image abroad. Using data on aid and opinions of the United States, we found that investments in health offer a unique opportunity to promote the perceptions of the United States abroad, in addition to disease burden relief. Our study provides new evidence to support the notion that health diplomacy is a net win for the United States and recipient countries alike.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No human participants were involved in this study. Institutional review board approval was not needed.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Dieleman JL, Schneider MT, Haakenstad A et al. Development assistance for health: past trends, associations, and the future of international financial flows for health. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2536–2544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dzau V, Fuster V, Frazer J, Snair M. Investing in global health for our future. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1292–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1707974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauci AS, Eisinger RW. PEPFAR—15 years and counting the lives saved. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):314–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta V, Kerry VB. Globally inclusive investments in health: benefits at home and abroad. BMJ. 2017;356:j1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the US government fiscal year 2018: a new foundation for American greatness. 2017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2107.

- 6.Nye JS. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York, NY: PublicAffairs; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnhart S. PEPFAR: is 90-90-90 magical thinking? Lancet. 2016;387(10022):943–944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gostin LO. President’s emergency plan for AIDS relief: health development at the crossroads. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2046–2048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kates J, Wesler A. Global financing for malaria: trends & future status. Kaiser Family Foundation. December 2014. Available at: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/report/global-financing-for-malaria-trends-future-status. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- 10.Bendavid E, Holmes CB, Bhattacharya J, Miller G. HIV development assistance and adult mortality in Africa. JAMA. 2012;307(19):2060–2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakubowski A, Stearns SC, Kruk ME, Angeles G, Thirumurthy H. The US President’s Malaria Initiative and under-5 child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a difference-in-differences analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(6):e1002319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldsmith BE, Horiuchi Y, Wood T. Doing well by doing good: the impact of foreign aid on foreign public opinion. Quart J Polit Sci. 2014;9(1):87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pew Research Center. Global attitudes and trends. 2018. Available at: http://www.pewglobal.org/datasets. Accessed October 27, 2017.

- 14.The World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups: historical classification by income in XLS format. 2018. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 15.US Government Agency for International Aid. Foreign Aid Explorer. Available at: https://explorer.usaid.gov/data.html. Accessed December 5, 2017.

- 16.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Purpose codes: sector classification. 2018. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/purposecodessectorclassification.htm. Accessed December 5, 2017.

- 17.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen ET, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):383–388. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The World Bank. World Development Indicators 1960–2017. Available at: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators. Accessed November 20, 2017.

- 19.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119(1):249–275. [Google Scholar]

- 20.4 International Media & Newspapers 2006–2018. Available at: https://www.4imn.com. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- 21. W3 Newspapers. Find world newspapers online. 2009–2018. Available at: https://www.w3newspapers.com. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- 22.Loria S. TextBlob: Simplified Text Processing. Release v0.15.2. Available at: https://textblob.readthedocs.io/en/dev. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- 23.Kaiser Family Foundation. Breaking down the U.S. global health budget by program area. 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/breaking-down-the-u-s-global-health-budget-by-program-area. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- 24.Milner HV, Tingley D. Public opinion and foreign aid: a review essay. Int Interact. 2013;39(3):389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walensky RP, Borre ED, Bekker L Do less harm: evaluating HIV programmatic alternatives in response to cutbacks in foreign aid. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(9):618–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Winskill P, Slater HC, Griffin JT, Ghani AC, Walker PG. The US President’s Malaria Initiative, Plasmodium falciparum transmission and mortality: a modelling study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner Z, Barofsky J, Sood N. PEPFAR funding associated with an increase in employment among males in ten sub-Saharan African countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(6):946–953. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser Family Foundation. White House releases FY18 budget request. May 24, 2017. Available at: https://www.kff.org/news-summary/white-house-releases-fy18-budget-request. Accessed April 20, 2018.