Abstract

Introduction: Community health workers (CHWs) play a vital role in health across Hawai‘i, but the scope of this work is not comprehensively collated. This scoping review describes the existing evidence of the roles and responsibilities of CHWs in Hawai‘i. Methods: Between May and October 2018, researchers gathered documents (eg, reports, journal articles) relevant to Hawai‘i CHWs from health organizations, government entities, colleges/universities, and CHWs. Documents were reviewed for overall focus and content, then analyzed using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 10 Essential Public Health Services as well as the Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project roles to identify workplace roles and gaps. Results: Of 92 documents received, 68 were included for review. The oldest document dated to 1995. Document types included curricula outlines, unpublished reports, and peer-reviewed articles. Documents discussed trainings, certification programs, CHWs' roles in interventions, and community-, clinical-, and/or patient-level outcomes. Cultural concordance parity between CHWs and patients, cost savings, and barriers to CHW work were noted. Most roles named by the Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project were mentioned in documents, but few were related to the roles of “community/policy advocacy” and “participation in research and evaluation.” Workplace roles, as determined using the 10 Essential Public Health Services, focused more on “assuring workforce competency” and “evaluation,” and less on “policy development,” and “enforcing laws.” Discussion: CHWs are an important part of Hawaii's health system and engage in many public health functions. Although CHW roles in Hawai‘i mirrored those identified by the CHW Core Consensus Project and 10 Essential Public Health Services frameworks, there is a noticeable gap in Hawai‘i CHW professional participation in research, evaluation, and community advocacy.

Keywords: Community health workers, CHW, roles, interventions, training, outreach, Hawai‘i

Introduction

Community health worker (CHW) is a broad term encompassing a wide range of job titles including lay health worker, outreach worker, navigator, and others.1 The American Public Health Association defines CHWs as frontline public health workers who are trusted community members with an unusually close understanding of the community served, with roles including bridging health/social services and the community, increasing health access, ensuring cultural competency of interventions, and building community and individual capacity,2 though other definitions exist.3,4 Common activities include mediation between health and social systems, communities, and individuals; health education; case management; coaching and social support; advocacy; and service provision.5 Nationally, CHWs may participate in health interventions and health promotion activities related to cancer screening,6–8 cardiovascular disease prevention,9–11 mental health interventions,6 asthma control,12 and medication safety.6 Community membership and racial/ethnic concordance between CHWs and patients can positively affect intervention success;6,13 however, health outcomes and cost effectiveness of CHW interventions vary.6,14

National interest in expanding the roles of CHWs is demonstrated through federal policies and initiatives. CHW roles were recognized in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.15 The Department of Labor's Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grant provided $2 billion nationally toward training and development of in-demand jobs, including CHWs, at community colleges across the country and in Hawai‘i.16 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supported CHW engagement in proffering community-clinical linkages for disease prevention and management.17

While CHWs have long been engaged across Hawai‘i, the full scope of this work has not been comprehensively collated. Although individual projects and studies document CHW participation in trainings and health interventions, reports on CHW activities in Hawai‘i may not be published in peer-reviewed journals and thus may not be mentioned in systematic literature reviews nationally.6,14 To describe the breadth of CHW engagement in Hawai‘i, we conducted a scoping review to understand the history and evidence base of CHW activities, roles, and responsibilities across all types of available literature.

Methods

Research Collaboration

The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Healthy Hawai‘i Initiative Evaluation Team (UHET) was asked by the Hawai‘i State Department of Health (HDOH) to conduct a scoping review of the breadth of CHW engagement in Hawai‘i. Scoping reviews examine the range of activities and the state of research where knowledge is limited.18 Following one method for scoping reviews,19 we identified the knowledge gap on CHWs in Hawai‘i, then gathered relevant documents. We solicited documentation, reports, and journal articles on Hawai‘i-based CHWs from leaders and CHWs at health organizations, government agencies, and colleges and universities via email, face-to-face contact, and phone. Documents collected from May through October 2018 were sent to UHET. We also identified journal articles through PubMed and the UH Mānoa Library OneSearch system from May through September 2018.

Analysis Plan, Framework Analysis, and Theoretical Frameworks

Document data were entered into a Microsoft Excel database, including publication year, setting of the CHW work, document type (eg, journal article, report), CHW roles (eg, training, intervention), types of outcomes (eg, training or patient outcomes), and cost-savings data. Only documents discussing work done in Hawai‘i related to CHWs were included. Descriptive quantitative data were analyzed in Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Documents were qualitatively analyzed for CHW titles, themes related to engagement, barriers, and opportunities using the Excel database. To understand how CHWs were engaged in service, we conducted a framework analysis20 using 2 nationally recognized frameworks (Table 1): the CHW Core Consensus Project (C3 Project, a partnership between the University of Texas-Houston School of Public Health's Institute for Health Policy and the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), which identified major CHW roles,5 and the CDC's 10 Essential Public Health Services (10 EPHS).21 The C3 Project roles were developed using a community-based participatory research approach that included gathering primary data from 5 states and 2 national organizations on CHW roles and training, and then reviewing the findings. The review was conducted by an advisory body and also by CHWs at national meetings and online prior to publication.5 The roles identified by the C3 Project were used to understand the roles and responsibilities of CHWs in Hawai‘i, and to improve the comparability of our findings to those of other studies.1 The 10 EPHS were selected to understand the public health functions of CHWs in Hawai‘i. This study did not include human subjects and thus did not require institutional review board oversight.

Table 1.

| 10 Essential Public Health Services21 | Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) Project Roles5 |

| Monitor health status to identify community health problems | Cultural mediation among individuals, communities, and health and social service systems |

| Diagnose and investigate health problems and health hazards in the community. | Providing culturally appropriate health education and information |

| Inform, educate, and empower people about health issues | Care coordination, case management, and systems navigation |

| Mobilize community partnerships to identify and solve health problems | Provide coaching and social support |

| Develop polices and plan that support individual and community health efforts | Advocating for individuals and communities |

| Enforce laws and regulation that protect health and ensure safety | Building individual and community capacity |

| Link people to needed professional health services and assure the provision of health care when otherwise unavailable | Provide direct services |

| Assure a competent public health and personal health care workforce | Implementing individual and community assessments |

| Evaluate effectiveness, accessibility and quality of personal and population-based health services. | Conducting outreach |

| Research for new insights and innovative solutions to health problems. | Participating in evaluation and research |

Results

Scoping Review

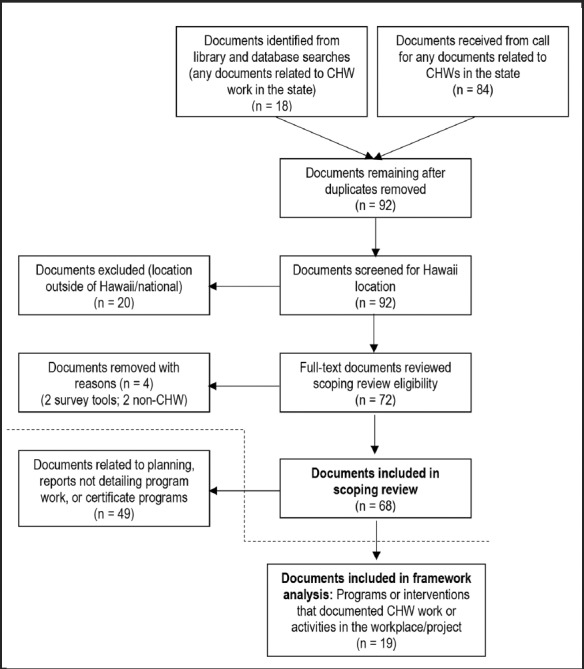

UHET collected 92 unduplicated documents via document solicitation and library search. Sixty-eight documents were retained for the scoping review (Figure 1). Table 2 describes both self-reported job titles of CHWs from recent conference registrations and titles used by employers.22,23 Commonly reported titles were care coordinator, case manager or worker, community health advocate, community health outreach worker, health educator, patient navigator, or peer educator. Other titles were also reported, such as community health educator, health care worker, peer advocate, and public health aide.

Figure 1.

Article Exclusion Process Diagram for Scoping Review of CHW Work in Hawai‘i

Table 2.

Commonly Self-reported and Employer-reported CHW Job Titles in Hawai‘i (Alphabetized)

| Commonly Reported | Less Frequently Reported |

| Care coordinator or care guide Case managers/case workers Community health advocate or advisor Community health representative Community health worker Community liaison Community outreach worker/community health outreach worker Enrollment specialist Health ambassador Health educator/Lay health educator Patient navigator Patient representative Peer educator |

Certified forensic peer specialist Clinical social worker Community advocate Community health educator Community health service program assistant Community health worker supervisor Community wellness advocate Doula Eligibility worker/manager Employment counselor/job coach Family caregiver Government and social service specialist Health care worker Housing counselor Interpreter Mentor/Kupuna Nutrition assistant Outreach education worker Paramedical assistant Patient care coordinator Peer advocate or advocate Public health aides Student |

Descriptive statistics about the documents are reported in Table 3. The oldest document was dated 1995. Just over a third (35.82%) were published since 2015, coinciding with a period of increased workforce development programs. Many reported on statewide projects (41.79%), followed by work on O‘ahu (31.34%). Island-specific project examples include a CHW diabetes self-management intervention on O‘ahu24 and delivery of a lifestyle-change program on Moloka‘i.25 Three documents contained information about a Pacific-26 or national-level project that included work in Hawai‘i, including national evaluations.27,28 Most documents were academic products such as journal articles (38.81%), followed by reports (26.87%), which included evaluations of conferences or trainings,29 or reports to grantors about curriculum development.30–32 We received agendas and minutes for trainings29 or planning meetings,33–36 and strategic plans that envisioned CHWs as part of community behavioral health teams.37,38 Lastly, we found state legislative documents regarding CHWs.39–41

Table 3.

Document Descriptions

| Description | Frequency (%) (n=68) |

| Year of Publication | |

| 1999 or older | 4 (5.88) |

| 2000–2004 | 8 (11.76) |

| 2005–2009 | 16 (23.53) |

| 2010–2014 | 13 (19.12) |

| 2015 and newer | 25 (36.76) |

| Undated | 2 (2.94) |

| Specific Geographies | |

| Statewide (all islands) | 28 (41.18) |

| National or Pacific plus any island | 3 (4.41) |

| Any island or combination of islands (except whole state) | 37 (54.41) |

| Any Hawai‘i Islanda | 6 (8.82) |

| Any Kaua‘ia | 4 (5.88) |

| Any Lāna‘ia | 1 (1.47) |

| Any Mauia | 11 (16.18) |

| Any Moloka‘ia | 9 (13.24) |

| Any O‘ahua | 27 (39.71) |

| Document Type | |

| Journal articles, dissertations, or poster presentations | 27 (39.71) |

| Reports | 18 (26.47) |

| Certification curricula or flyers | 9 (13.24) |

| Agendas and minutes | 8 (11.7 |

| Strategic plan | 3 (4.41) |

| Legislation | 3 (4.41) |

| CHW Engagement | |

| Education and training programs | 37 (54.41) |

| Interventions | 18 (26.47) |

| Needs assessment | 7 (10.29) |

| Other | 6 (8.82) |

Frequency of each island mentioned; for example one article mentioned Lāna‘i, Hawai‘i Island, and O‘ahu.

Over half of the documents related to educational or training opportunities for CHWs. The oldest document among these dated to 2002 and discussed CHW certificate programs as part of the Wai‘anae Health Academy, a partnership between Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center and Kapi‘olani Community College.27,42–44 Between 2002–2007, two more college-delivered certificate programs were offered in “Case Management” and “Outreach for Health Promotion,” designed by a statewide community advisory group including representatives from Community Health Centers (CHCs) and Native Hawaiian Health Care Systems, convened by the Hawai‘i Primary Care Association and funded by the Hawai‘i Rural Development Project. More than 150 CHWs participated in 1 or both certificate programs delivered face-to-face on 5 islands through 2007.45 The 2015 Department of Labor TAACCCT Grant funded year-long CHW certificate programs at community colleges across the state.46

Disease- and/or population-specific trainings were developed, which included diabetes47,48 and cardiovascular disease-specific trainings49 for CHWs working with Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Filipinos. The ‘Imi Hale Native Hawaiian Cancer Network developed a cancer patient navigation program for CHWs and outreach workers to facilitate timely cancer screening and treatment.50 Three statewide workshops in 2013 were developed specifically to assist CHWs with working with public benefit programs (ie, MedQuest, financial assistance, Social Security, federal housing assistance, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), along with working with special populations (eg, people affected by homelessness, migrants from the nations of the Compact of Free Association).29 In 2017, a training on chronic disease prevention and management occurred at a statewide CHW conference.23

Barriers to advancing the work of CHWs were identified in needs assessments and other documents. Themes from recent documents included the need for more educational and training opportunities, resource and information sharing, standardized training curricula, increased pay and reimbursement strategies, and CHW empowerment and support for their work.23,51 Training needs related to chronic disease management,23,52 including the management of diabetes,47,52,53 cardiovascular disease,49 heart disease,52 and cancer,52 were frequently identified. Other topics of interest were learning about community resources22,46 for families, working with people experiencing homelessness, and financial aid.23,51 An unpublished survey found CHWs sought other additional skills, including crisis management, community building and leadership development, outreach strategies, policy and advocacy, self-care and boundary setting, team building, and working with underserved populations.23 Barriers to educational programs or workforce development access included program availability and location54 and college entrance requirements, cost, and time limitations of busy CHWs.55 Currently, workplaces have addressed some of these issues through in-house training programs;54 however a study of professional development programs found these types of programs face a number of worker-, clinic-, and community-related barriers which will require system-level changes to overcome.27

Funding barriers were consistently identified across documents. The staff at Federally-Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) report previously wanting to hire more CHWs51 and that CHWs are an integral part of the workforce, but also that CHW positions are constructed from multiple grants and not necessarily reimbursed through other payment sources.54 For example, insurers may contract with interpreters for physician appointments, but interpreters may not be available during scheduled appointments, resulting in CHWs providing those services unreimbursed.54 The lack of a career pathway was another barrier identified to advancing the field.56 However, one study examining cancer navigators found as the level of navigator education increased, so did the cost of the navigator (ie, navigators who were nurses received higher pay),57 suggesting increased education is a means to increased pay.

Documents discussed a number of opportunities, past and present. First, CHC-based CHWs and their employers agree with the APHA's definition of CHWs, and also agree that the C3 Project roles broadly reflect CHWs' scope of work.51 Support and opportunities from different sectors exist for statewide networking and for potentially starting a CHW association. For example, 6 statewide conferences of CHWs have been held since 2002 to provide networking and training for CHWs, along with encouragement to build a CHW professional association.23,58 Among CHWs, support exists to develop task forces or groups59,60 for planning around policymaking and legislation.59 In addition to the training and certification opportunities mentioned above, FQHCs are in a unique position to provide on-the-job training for CHWs.27,54 Two documents reported that CHW-involved interventions yielded cost savings, including reduced hospital utilization among high utilizers for a savings of $34,681–$71,338 per navigator,61 and a 91% drop in emergency department use among pediatric asthma patients, with a savings of $931 per patient.62 Lastly, policies related to CHWs were introduced into the Hawai‘i State Legislature39–41 which further demonstrates interest in this growing workforce.

Framework Analysis

For the framework analysis, we further limited the documents to those that directly discussed or evaluated CHWs' interventions or research work, in order to further understand the roles of CHWs in the workplace and analyze their roles vis-à-vis the C3 Project roles and 10 EPHS frameworks. This left 19 studies that specifically discussed the roles in these settings (Figure 1). Documents that discussed training programs, strategic planning, certification, or legislation were excluded from analysis. The included studies discussed chronic disease prevention and management, cancer navigation and screening interventions, a pediatric asthma management and control intervention, and lifestyle change interventions. Four studies63–66 discussed a single program, the Wai‘anae Cancer Research Project, and were combined for analysis.

The C3 Project roles (Table 4) most frequently discussed were “cultural mediation among individuals, communities, and health and social systems,” “providing culturally appropriate health education and information,” “care coordination, case management, and systems navigation,” and “providing coaching and support.” Nearly all articles mentioned mediation between patients or program participants and the health system, including providing assistance to patients overcoming systemic barriers to cancer treatment28,69,70 or screening,64,68 bridging between patients and clinics to improve treatment compliance,24 navigating social systems,61,71 or improving a health system's interventions.71 Activities were also aligned with providing culturally-appropriate health education and information. For example, in the Wai‘anae Cancer Research Project, lay health workers participated in the design of the study materials and implemented a culturally-appropriate intervention for Native Hawaiian women.63–66 Eleven articles mentioned care coordination, case management, systems navigation, and/or coaching and support. Case management and systems navigation were most prominent in articles regarding cancer services,28,63–66,68–71 and other articles mentioned case management as part of the duties of CHWs for other chronic disease interventions.24,54,62 Coaching and support were also prominent in cancer-related articles,28,63–66,69–71 although CHWs also served as lifestyle coaches for lifestyle-change programs.25,54 The C3 Project role that was cited least frequently was “implementing individual or community assessments.” For example, doctors trained in cancer screening, rather than CHWs, would provide assessments.68 However, CHW-implemented assessments included asthma risk assessments62 and community-level assessments in which data collection was conducted via focus groups48 or computer-assisted telephone interviewing.63–66

Table 4.

Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) Project Roles3 Identified in Studies Included in the Framework Analysis

| Author(s) or Organization(s) | 1† | 2† | 3† | 4† | 5† | 6† | 7† | 8† | 9† | 10† | Total |

| Stupplebeen, et al, 201954 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | |

| Braun, et al, 201570 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||

| Allison, et al, 201371 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||

| Braun, et al, 201228 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Aitaoto, et al, 201273 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||

| Fernandes, et al, 201267 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Domingo, et al, 201169 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Gellert, et al, 201025 | X | X | 2 | ||||||||

| Braun, et al, 200850 | X | X | 2 | ||||||||

| Santos, et al, 200872 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Aitaoto, et al, 200748 | X | X | 2 | ||||||||

| Gellert, et al, 200668 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||

| Beckham S, et al, 200462 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||

| A Breast and Cervical Cancer Project in a Native Hawaiian Community: Wai‘anae Cancer Research Project (Gotay, et al, 2000; Banner, et al, 1999; Matusnaga, et al, 1996; Banner, et al, 1995).63–66 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | |

| Humphry, et al, 199724 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Cheng, et al, n.d.61 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Total | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

Key: 1. Cultural Mediation Among Individuals, Communities, and Health and Social Service Systems. 2. Providing Culturally Appropriate Health Education and Information. 3. Care Coordination, Case Management, and System navigation. 4. Providing Coaching and Social Support. 5. Advocating for Individuals and Communities. 6. Building Individual and Community Capacity. 7. Providing Direct Service. 8. Implementing Individual and Community Assessments. 9. Conducting Outreach. 10. Participating in Evaluation and Research.

CHWs perform many of the 10 EPHS services (Table 5). The most frequently performed services were “inform, educate, and empower,” “link to or provide care,” “assure a competent workforce,” and “mobilize community partnerships.” CHWs provided health education and promotion across all articles in a variety of chronic disease prevention or management contexts. These included diabetes prevention54 and management;24 hypertension management;54,67 lifestyle change programs;25 cancer screening, navigation, and education;28,48,63–66,68,71 smoking cessation;72 emergency department diversion;61 and pediatric asthma management.62 Linkages to other services or provision of care was another key activity conducted by CHWs that was mentioned in all but 1 article. CHWs participated in some type of training program to deliver interventions or to participate in research projects,48,50,63,65 which we counted toward “assuring a competent workforce.” Additionally, CHWs marshalled community resources to promote health improvement, such as building community-clinical linkages.50,54 The least frequently mentioned of the 10 EPHS was the role of CHWs in evaluation.69,73 Two of the 10 EPHS were not mentioned in any articles. One was policy development, which includes developing local health policy and state-level planning, and the other was enforcing laws, which includes education on health laws and regulations, and compliance support.21

Table 5.

10 Essential Public Health Services21 Identified in Studies Included in the Framework Analysis

| Author(s) or Organization(s) | A ‡ | B ‡ | C ‡ | D ‡ | E ‡ | F ‡ | G ‡ | H ‡ | I ‡ | J ‡ | Total |

| Stupplebeen, et al, 201954 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Braun, et al, 201570 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Allison, et al, 201371 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Braun, et al, 201228 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||

| Aitaoto, et al, 201273 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |||

| Fernandes, et al, 201267 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||

| Domingo, et al, 201169 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Gellert, et al, 201025 | X | 1 | |||||||||

| Braun, et al, 200850 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||

| Santos, et al, 200872 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||

| Aitaoto, et al, 200748 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||

| Gellert, et al, 200668 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||

| Beckham S, et al, 200462 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| A Breast and Cervical Cancer Project in a Native Hawaiian Community: Wai‘anae Cancer Research Project (Gotay, et al, 2000; Banner, et al, 1999; Matusnaga, et al, 1996; Banner, et al, 1995).63–66 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Humphry, et a., 199724 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Cheng, et al, n.d.61 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||

| Total | 7 | 5 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 5 |

Key: A - Monitor Health. B - Diagnose & Investigate. C - Inform, Educate, Empower. D - Mobilize Community Partnerships. E - Develop Policies. F - Enforce laws. G - Link to/Provide Care. H - Assure Competent Workforce. I - Evaluate. J - Research.

Discussion

This scoping review found CHWs (and workers functioning as CHWs) have been part of the Hawai‘i health landscape for well over 20 years, during which time they have contributed to a number of health interventions with diverse populations. Additionally, formalized training and certification programs have been offered for at least the last 15 years, and a rich and diverse network of non-profit, academic, and government organizations has supported the growth of the CHW field. We identified several barriers and opportunities related to the field. In addition, we performed a framework analysis that examined CHWs roles in Hawai‘i related to both public health and the workplace.

To overcome some barriers related to training, distance-learning tools such as Zoom have been used for single-subject trainings and within some certificate programs. Use of these tools, plus asynchronous course delivery, could further promote access to training for CHWs across the state including those in rural, remote communities. Because such efforts may feel less personal than in-person courses, engagement and peer support should be considered in these modalities. Eliminating college admission and financial aid barriers could help in increasing certification enrollment. Programs should also work to ensure that working adults who enroll are able to secure practicum locations that will support their work schedules.54 Based on existing best practices, CHWs should be continuously involved in training development, facilitation, and support.74

In looking at the C3 Project roles, the least frequently mentioned role was “implementing individual or community assessments”; however, researchers in a few articles mentioned CHWs as fulfilling this role.48,62,63–66 Thus, CHWs in Hawai‘i may also be engaged in non-clinical roles in the areas of academic research and evaluation. Researchers may want to consider CHWs for positions on their teams. CHWs recently mentioned policy and advocacy as a training need.23 CHWs in Hawai‘i fulfilled many of the 10 EPHS services, although “law enforcement” and “policy development” were not found in this study. These roles may be filled by other types of employees, although CHWs have successfully participated in community-level advocacy to address policies related to the social determinants of health and promote health equity in other settings.75,76 CHWs could potentially serve as key informants for health in the community for policymakers.

Lastly, organizations working toward creating momentum for a statewide CHW association should support CHWs' development as leaders in organizing efforts, and provide support for trainings, networking, and reimbursement for CHWs. Lessons learned from other communities and states should be leveraged to build capacity; the new National Association of Community Health Workers can be a capacity building resource. Existing trainings for CHWs could be leveraged into online or distance training formats for greater reach. Building reimbursement infrastructure for CHWs, a multifaceted topic, will require participation of CHWs statewide including those working at non-profits, health centers, and state institutions.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. We relied on submitted documents and those found via searches, and our reliance on written documents likely led to omission of projects with CHWs that lacked documentation. While written documents are resistant to memory decay,77 documents may not contain information germane to the engagement of CHWs. Additionally, we did not receive documents from known CHW employers and no comprehensive list of CHWs or their employers exists, thus, a call for documents may not have reached all CHWs or their employers. Documentation may simply not exist, pointing to a need for further data collection and recording of activities related to the field. It is possible that some documents may have been withheld for unknown reasons. Short-term funding cycles may also hamper information gathering due to turnover and institutional memory loss. As a result, CHWs' contributions to health care in the state are likely underreported. One planned remedy to these issues is the development of a website to house knowledge of Hawai‘i CHWs that can be continually updated. Other recommendations for research and data collection include conducting a statewide CHW assessment, collecting oral histories on the CHW movement in the state, and performing updated scoping reviews over time. Finally, documents analyzed could suffer from selection bias, as a large number of documents discussed training programs rather than CHW work in the field. We addressed this through the framework analysis.

Conclusion

This review collected and analyzed 68 documents related to the various contributions of CHWs to Hawaii's health care landscape. CHWs work largely mirrored the nationally recognized C3 Project roles and some of the 10 EPHS services. We have provided a snapshot of the landscape, not a complete picture. This project highlights the need for a comprehensive inventory of CHWs and CHW employers in Hawai‘i, and the need for more documentation and research on CHW contributions to the health of Hawaii's communities.

Practical Implications

This article gathers and describes existing documents about community health workers in Hawai‘i to show where they have been working, what work they have been doing, and needs of the workforce. We hope this article will expand and support the CHW field in Hawai‘i in the future. The documents used in this review are cataloged on a publicly accessible website to assist CHWs and others in their work.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank those who provided documents for this review. Mahalo nui loa to Stephanie Cacal for her assistance in writing this manuscript.

Abbreviation List

- CHC

Community health center

- CHW

Community health worker

- HDOH

Hawai‘i State Department of Health

- HPCA

Hawai‘i Primary Care Association

- UHET

University of Hawai‘i Evaluation Team (Office of Public Health Studies)

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclosure Statement

This publication was supported by the Hawai‘i State Department of Health.

Highlights

A scoping review of documents on community health workers (CHW) in Hawai‘i was conducted

Documents discussed workforce programs, intervention roles, barriers, and outcomes

Many roles performed by Hawai‘i CHWs reflect the roles performed by the national workforce and identified in public health frameworks

CHWs are working statewide and are important to Hawaii's public health and health care systems

Opportunities exist for CHW engagement in research, evaluation, and advocacy

References

- 1.Lohr AM, Ingram M, Nuñez AV, Reinschmidt KM, Carvajal SC. Community-clinical linkages with community health workers in the United States: a scoping review. Health Promot Prac. 2018;19(3):349–360. doi: 10.1177/1524839918754868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Public Health Association, author. Support for community health workers to increase health access and to reduce health inequities. 2009. Nov 10, https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities.

- 3.Minnesota Community Health Worker Alliance, author. Definition. 2018. http://mnchwalliance.org/who-are-chws/definition/

- 4.World Health Organization, author. Global health workforce alliance - Community health workers. 2016. https://who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/themes/community/en/

- 5.Rosenthal E, Rush C, Allen C. Understanding scope and competencies: a contemporary look at the United States community health worker field. Houston, TX: Project on CHW Policy & Practice, University of Texas-Houston School of Public Health, Institute for Health Policy; 2016. pp. 1–43. https://sph.uth.edu/dotAsset/28044e61-fb10-41a2-bf3b-07efa4fe56ae.pdf. Published July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3–e28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen TT, Tsoh JY, Woo K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and Chinese Americans: efficacy of lay health worker outreach and print materials. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):e67–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland KB, Milliken EL, Rohan EA, et al. Use of community health workers and patient navigators to improve cancer outcomes among patients served by federally qualified health centers: a systematic literature review. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):61–76. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR, Hill MN, Kim MT, Levine DM. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownstein JN, Chowdhury F, Norris S, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez PM, Zanowiak J, Goldfeld K, et al. Protocol for project IMPACT (improving millions hearts for provider and community transformation): a quasi-experimental evaluation of an integrated electronic health record and community health worker intervention study to improve hypertension management among South Asian patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):810. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2767-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peretz PJ, Matiz LA, Findley S, Lizardo M, Evans D, McCord M. Community health workers as drivers of a successful community-based disease management initiative. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1443–1446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murayama H, Spencer MS, Sinco BR, Palmisano G, Kieffer EC. Does racial/ethnic identity influence the effectiveness of a community health worker intervention for African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes? Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(3):485–493. doi: 10.1177/1090198116673821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Medical Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez J, Ro M, Villa NW, Powell W, Knickman JR. Transforming the delivery of care in the post-health reform era: what role will community health workers play? Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):e1–e5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durnham C, Eyster L, Mikelson KS, Cohen E. Early results of the TAACCCT grants: the trade adjustment assistance community college and career training grant program brief 4. Wahsington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017. pp. 1–21. https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/completed-studies/20170308-TAACCCT-Brief-4.pdf. Published February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutledge GE, Lane K, Merlo C, Elmi J. Coordinated approaches to strengthen state and local public health actions to prevent obesity, diabetes, and heart disease and stroke. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15(E14):1–7. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(69):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(117):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support (OSTLTS), author The 10 essential public health services an overview; Presentation presented at: OSTLTS meeting; May 23, 2014; Acme, Michigan. https://www.cdc.gov/stltpublichealth/publichealthservices/pdf/essential-phs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapi‘olani Community College, author. CHW employer feedback survey. Honolulu, HI: Kapi‘olani Community College; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawai‘i Department of Health (HDOH), author Report for CHW conference 8/25/17 evaluation. Kapolei, HI: Author; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphry J, Jameson LM, Beckham S. Overcoming social and cultural barriers to care for patients with diabetes. West J of Med. 1997;167(3):138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gellert KS, Aubert RE, Mikami JS. Ke ‘Ano Ola: Molokai's community-based healthy lifestyle modification program. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):779–783. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aitaoto NT, Braun KL, Ichiho HM, Kuhau R L. Diabetes today in the Pacific: reports from the field. Pac Health Dialog. 2005;12(1):124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrar B, Morgan JC, Chuang E, Konrad TR. Growing your own: community health workers and jobs to careers. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):234–246. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun KL, Kagawa-Singer M, Holden AEC, et al. Cancer patient navigator tasks across the cancer care continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):398–413. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spock N. Public benefits training for outreach workers; public benefits training - part ii; and public benefits and special populations (meeting agendas) Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Primary Care Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeGare S. Curriculum development report. Kahului, HI: University of Hawai‘i, Maui College; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legare S. CHW focus group feedback. Kahului, HI: University of Hawai‘i, Maui College; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlather C, LeGare S. CHW curriculum program evaluation report. Kahului, HI: University of Hawai‘i, Maui College; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Office of the Governor, author. Workforce committee meeting June 25, 2015 (Meeting Minutes and Presentation) Honolulu, HI: State of Hawai‘i, Health Care Innovation Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Office of the Governor, author. Workforce committee meeting minutes July 23, 2015 3:00pm–4:30pm (Meeting Minutes and Presentation) Honolulu, HI: State of Hawai‘i, Health Care Innovation Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of the Governor, author. Hawai'i health care innovation models project workforce committee meeting August 27, 2015 (Meeting Minutes and Presentation) Honolulu, HI: State of Hawai‘i, Health Care Innovation Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Office of the Governor, author. Hawai'i health care innovation models project workforce committee meeting October 15, 2015 (Meeting Minutes and Presentation) Honolulu, HI: State of Hawai‘i, Health Care Innovation Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of the Governor, The Hawai‘i Healthcare Project, author. State of Hawai‘i healthcare innovation plan. Honolulu, HI: Office of the Governor; 2014. https://governor.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Hawaii-Healthcare-Innovation-Plan_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Office of the Governor, author. Hawai‘i State health innovation plan. Honolulu, HI: Office of the Governor; 2016. https://governor.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/FINAL-Hawaii-State-Health-System-Innovation-Plan-Appendices-June-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Relating to apprenticeships. HR HB1638 HD2 SD1, 29th leg, regular sess of 2018 (HI)

- 40.Requesting the department of health to establish a certification process, an oversight board, and a reimbursement process for services for community health workers. HR SCR 100, 29th leg, regular sess of 2018 (HI)

- 41.Requesting the department of health to establish a certification process, an oversight board, and a reimbursement process for services for community health workers. HR SR 59, 29th leg, regular sess of 2018 (HI)

- 42.Wai‘anae Health Academy, author. Wai'anae health academy: Ola Loa Ka Naauao (Brochure) Wai‘anae, HI: Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wai'anae Health Academy, author. Community health worker I general course (Brochure) Wai‘anae, HI: Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wai‘anae Health Academy, author. Community health worker II general course (Brochure) Wai‘anae, HI: Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spock N. Report on Department of Labor funds contracted through mcc rural development project, 2002–2008. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Primary Care Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlather TC. Community health worker certificate program evaluation [dissertation] Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Look MA, Baumhofer NK, Ng-Osorio J, Furubayashi JK, Kimata C. Diabetes training of community health workers serving native Hawaiians and Pacific people. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(5):834–840. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aitaoto NT, Braun KL, Dang KL, Soa TL. Cultural considerations in developing church-based programs to reduce cancer health disparities among Samoans. Ethn Health. 2007;12(4):381–400. doi: 10.1080/13557850701300707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moleta CDI, Look MA, Trask-Batti MK, Mabellos T, Mau ML. Cardiovascular disease training for community health workers serving native Hawaiians and other pacific peoples. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(7):190–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun KL, Allison A, Tsark JU. Using community-based research methods to design cancer patient navigation training. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(4):329–340. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spock N. Final report on HPCA-CHW Project: CHW engagement, December 15, 2015–June 30, 2016. Honolulu, HI: Hawai‘i Primary Care Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hawaii Department of Health, author. Hawaii CHW survey 2017. Kapolei, HI: Hawaii Department of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Look MA, Furubayashi JK. Ulu reports: Ulu Network strategic directions, 2004–2007. Honolulu, HI: John A. Burns School of Medicine, Department of Native Hawaiian Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stupplebeen DA, Sentell TL, Pirkle CM, et al. Community health workers in action: community clinical linkages for diabetes prevention and hypertension management at three CDC 1422 grant-funded community health centers. Hawaii J Med Public Health. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spock N. Final Report, Community health worker training program September 15, 2002–June 15, 2004. Pu‘unene, HI: Hawai‘i Primary Care Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mandari D, Mersberg S. Educational interests and barriers of community health workers in Hawai‘i. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Domingo JB, Braun KL. Characteristics of effective colorectal cancer screening navigation programs in federally qualified health centers: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):108–126. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spock N. Community health workforce development program. Pu‘unene, HI: Hawaii Primary Care Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moir S, Yasutake J. 2017 Community health worker priority survey. Honolulu, HI: Hawai‘i Public Health Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papa Ola Lōkahi, author. The Native Hawaiian Health Care Systems community health worker survey results. Honolulu, HI: Papa Ola Lokahi; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng D, Hilmes C, Nishizaki L, Shearer A. Poster. Honolulu, HI: Improving homeless care while reducing utilization. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beckham S, Kaahaaina D, Voloch K, Washburn A. A community-based asthma management program: effects on resource utilization and quality of life. Hawai‘i Med J. 2004;63(4):121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banner RO, DeCambra H, Enos R, et al. A breast and cervical cancer project in a Native Hawaiian community: Wai'anae cancer research project. Prev Med. 1995;24(5):447–453. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Banner RO, Gotay CC, Matsunaga DS, et al. Effects of a culturally tailored intervention to increase breast and cervical cancer screening in Native Hawaiians. In: Glover CS, Hodge FS, editors. Native outreach: A report to American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian communities. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute Office of Special Populations; 1999. pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matsunaga DS, Enos R, Gotay CC, et al. Participatory research in a Native Hawaiian community: The Wai'anae Cancer Research Project. Cancer. 1996;78(7):1582–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gotay C C, Banner R O, Matsunaga D S, et al. Impact of a culturally appropriate intervention on breast and cervical screening among native Hawaiian women. Prev Med. 2000;31(5):529–537. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernandes R, Braun KL, Spinner JR, et al. Healthy heart, healthy family: a NHLBI/HRSA collaborative employing community health workers to improve heart health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):988–999. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gellert K, Braun KL, Morris R, Starkey V. The ‘Ohana Day Project: a community approach to increasing cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Domingo JB, Davis EL, Allison AL, Braun KL. Cancer patient navigation case studies in Hawai'i: the complimentary role of clinical and community navigators. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(12):257–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Braun KL, Thomas WL, Domingo JL, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in Medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):365–370. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.llison AL, Ishihara-Wong DDM, Domingo JB, et al. Helping cancer patients across the care continuum: the navigation program at Queen's Medical Center. Hawaii J Med Public Healh. 2013;72(4):116–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santos L, Braun KL, Ae'a K, Shearer L. Institutionalizing a comprehensive tobacco-cessation protocol in an indigenous health system: lessons learned. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(4):279–89. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aitaoto N, Braun KL, Estrella J, Epeluk A, Tsark J. Design and results of a culturally tailored cancer outreach project by and for Micronesian women. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.100262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The University of Arizona, Arizona area Health Education Centers Program, Community Health Worker National Education Collaborative, author. Key considerations for opening doors: developing community health worker education programs. Tucson, AZ: Arizona Area Health Education Centers Program, The University of Arizona; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sabo SJ, Ingram M, Reinschmidt KM, et al. Predictors and a framework for fostering community advocacy as a community health worker core function to eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ingram M, Schachter KA, Sabo SJ, et al. A community health worker intervention to address the social determinants of health through policy change. J Prim Prev. 2014;32(2):199–123. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiss CH. Evaluation. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]