Abstract

Our understanding of the scope and clinical relevance of gut microbiota metabolism of drugs is limited to relatively few biotransformations targeting a subset of therapeutics. Translating microbiome research into the clinic requires, in part, a mechanistic and predictive understanding of microbiome-drug interactions. This review provides an overview of microbiota chemistry that shapes drug efficacy and toxicity. We discuss experimental and computational approaches that attempt to bridge the gap between basic and clinical microbiome research. We highlight the current landscape of preclinical research focused on identifying microbiome-based biomarkers of patient drug response and we describe clinical trials investigating approaches to modulate the microbiome with the goal of improving drug efficacy and safety. We discuss approaches to aggregate clinical and experimental microbiome features into predictive models and review open questions and future directions toward utilizing the gut microbiome to improve drug safety and efficacy.

Keywords: Microbiome, Drug metabolism, Metabolomics, High throughput genomics

1. Introduction

Microbiome research has reinvigorated an ecological and metabolic view of diseases, including, but not limited to, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, metabolic diseases and cancers. Advances in culture-independent methodologies for high throughput analysis of microbial community composition and function, analytical chemistry techniques and gnotobiotic mouse models have expanded our understanding of gut microbiota-mediated biotransformations of exogenous compounds including diet-based chemicals, environmental toxins and therapeutic drugs [1,2]. In particular, recent studies provide mechanistic insight into the role of gut microbiota metabolism in drug bioavailability, efficacy and toxicity and suggest that the gut microbiome, in addition to human genetics and environmental variables, contributes to inter-personal variation in human drug responses [1,2].

However, we have limited insight into 1) the broader spectrum of human gastrointestinal tract microbial species and enzymes that can alter drug bioavailability and toxicity; and 2) the clinical relevance of microbiome metabolism. These gaps in our understanding of gut microbiome chemistry at both the community and individual gut strain level present a challenge to incorporating data from microbiome studies into accurate surrogate endpoints for clinical studies. Here, we describe human and microbial drivers of variability in drug response, and discuss current barriers and opportunities for translating basic research on microbial drug metabolism into clinical applications. We specifically focus on model systems, experimental approaches and computational techniques to characterize the microbiome and its interactions with drugs.

2. Connecting human and microbial drivers of variability in drug response

2.1. Human metabolism and individual variation in drug response

Advances in high throughput sequencing and analytical chemistry propel precision medicine initiatives that use genomic, gene expression, proteomic and metabolomic data to inform patient treatment and care [3]. Yet, using these diverse data types to systematically maximize drug efficacy and minimize toxicity remains an open challenge. Towards addressing this challenge, pharmacology subdisciplines, pharmacogenomics and pharmacometabolomics, aim to identify the impact of human genetics and metabolism on patient drug responses [4]. Among the early successes of pharmacogenomics research was the identification of genetic polymorphisms in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzyme family which catalyzes the glucuronidation of drug compounds, promoting their inactivation and elimination from the human body. Patients with specific UGT1A1 variants have lower glucuronidation rates, which impacts the detoxification of a number drugs, including the HIV drug atazanavir, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and the chemotherapeutic irinotecan [5,6]. Clinical laboratories can thus use an UGT1A1 genotype assay to determine personalized patient toxicity risk [7]. Beyond UGT genotyping, pharmacogenomics tests that target other hepatic enzymes involved in drug metabolism, such as members of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily, may guide dosing decisions. For example, in the package insert for warfarin, a commonly prescribed drug with a narrow therapeutic range, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) includes a dosing guide based on a patient's CYP2C9 genotype [8,9].

Early proponents of pharmacogenomics hypothesized that genetic polymorphism analysis in drug metabolizing enzymes and the human genome more broadly would substantially improve clinical practice to reduce poor efficacy and toxicity [10,11]. However, basic research advances characterizing how genome variants impact drug metabolism have not been broadly translated into the clinic. In part, this discrepancy relates to how drug metabolism has been traditionally characterized in the context of the human liver and intestinal mucosa. The gut microbiota is a third dimension in drug metabolism, providing a nonoverlapping enzymatic capacity that generates distinct metabolites from host enzymatic products and may also shape drug pharmacokinetics. Research focused on extending pharmacogenomics and pharmacometabolomics to include the impact of the microbiome on drugs falls under the umbrella of pharmacomicrobiomics [12].

2.2. Microbiome chemical mechanisms shape drug metabolism

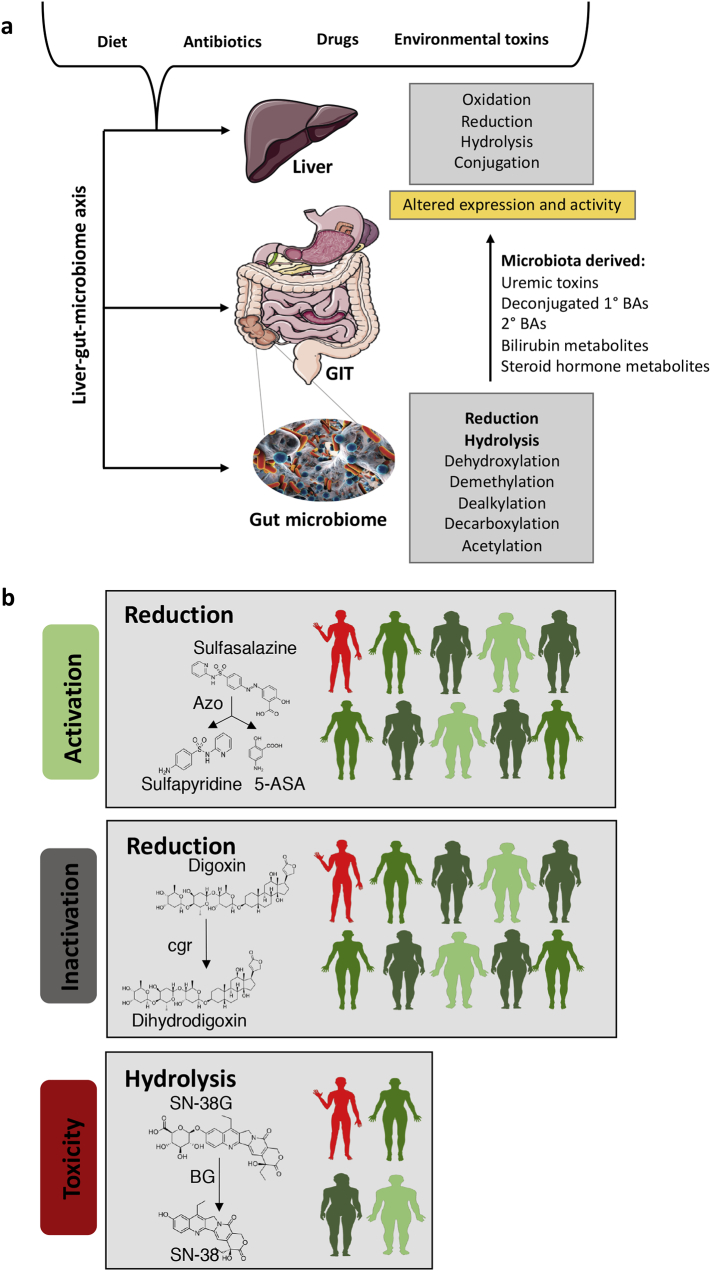

The gut microbiota alters drugs by various mechanisms: degrading the drug [13,14]; activating the drug [[13], [14], [15]]; and modulating host enzymes that metabolize the drug [13,14] (Fig. 1). Known microbial reactions that shape drug metabolism have been reviewed extensively by Wilson et al., and Spanogiannopoulos et al., and highlight bacterial enzymes such as β-glucosidases, β-glucuronidases, aryl sulfatases, azoreductases and nitroreductases, which have prominent roles in xenobiotic metabolism and vary widely in activity, sequence similarity, and abundance across individuals [1,2]. Hydrolytic and reductive reactions are the primary chemical mechanisms of gut microbiota drug metabolism. These reactions reflect the physiochemical parameters of the distal intestine, which has a limited oxygen gradient. The gut microbiota is also the source of numerous other chemical reactions including acetylation, deamination, dehydroxylation, decarboxylation, demethylation, deconjugation and proteolysis [1,2]. To date, microbial strains and enzymes have been experimentally demonstrated to directly or indirectly impact the metabolism and efficacy of over 50 therapeutic drugs, driving inter-patient variability in drug activation, inactivation and toxicity [1,2].

Fig. 1.

Gut microbiota-host liver metabolic interactions drive variability in drug response.

a Hepatic and gut microbiome enzymes co-metabolize chemically diverse exogenously derived substrates including foods, therapeutic drugs and environmental toxins. Key host hepatic enzymes include the cytochrome P450s (CYPs) superfamily and flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs) [16] which are involved in phase I metabolism. Phase II enzymes including glutathione S-transferases (GST), sulfotransferases (SULTs) and uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs). Hydrophilic therapeutic drug and drug conjugates excreted from the liver into the gastrointestinal tract via the biliary route are chemically modified primarily by gut microbiota hydrolytic and reductive reactions into hydrophobic products that can be reabsorbed via enterohepatic circulation [72], modified or extensively degraded by the gut microbiota. Gut microbiota metabolism also indirectly regulates phase I and II hepatic enzymes by producing metabolites, including uremic toxins and secondary bile acids, that alter hepatic enzyme expression and activity. b Gut microbiota enzyme catalyzed reactions have been linked to variation in patient response phenotypes. For example, microbial mediated azoreduction transforms the anti-inflammatory drug, sulfasalazine, into bioactive products. 10% of healthy individuals are poor converters of sulfasalazine [73]. Microbial metabolism also negatively impacts host drug responses. Approximately 10% of patients given the cardiac glycoside, digoxin, excrete high levels of an inactive metabolite which is generated by microbial enzymes [74]. 25% of patients taking Irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for the treatment of colorectal cancer experience grade 3–4 diarrhea which is mediated by microbial β-glucuronidase reactivation of a major inactive metabolite of the drug [75].

2.3. Microbiome modulation of phase I and II drug metabolism enzymes

Microbial metabolism of dietary and endogenous compounds indirectly shapes key host hepatic enzymes that broadly contribute to drug metabolism. For example, Phase I hepatic enzymes account for 80% of oxidative metabolism of commonly used medications and include the cytochrome P450s (CYPs) superfamily and flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs) [16]. Phase II hepatic enzymes include glutathione S-transferases (GST), sulfotransferases (SULTs) and uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) and play key roles in drug detoxification and elimination from the body. The expression and activity of these enzymes is modulated by gut microbiota metabolism of uremic solutes, bile acids and steroid hormones; these microbiome-drug interactions can have adverse consequences for patients taking drugs that are substrates for these enzymes [17,18]. Microbiota produced uremic solute indoxyl sulfate decreases CYP3A4 expression, reducing CYP3A4 mediated metabolism clearance of a diverse range of therapeutics including erythromycin, nimodipine and verapamil (Fig. 1) [19].

2.4. Therapeutic drug influences on the gut microbiome

Research studies defining how therapeutic drug moderation the gut microbiome can play a central role in a drug's mechanism of action are limited. Of note, metformin, an antidiabetic drug, has a poorly defined mechanism of action and is known to alter gut microbiome composition [20,21]. Recently Sun et al., used a combined metabolomics and shotgun metagenomic approach using human serum and feces to conclude that metformin decreases the abundance of Bacteroides fragilis, limiting its bile salt hydrolase activity and promoting an increase in glycoursodeoxycholic acid concentrations in the gut [20]. Sun et al., also used a mouse model to confirm that glycoursodeoxycholic acid suppresses intestinal farnesoid X receptor signaling and alleviates obesity-related metabolic disease [20]. Recent work by Maier et al., illustrates the off-target effects of therapeutic drugs on the microbiome. Maier identified non-antibiotic therapeutic drugs that inhibit the growth of specific gut relevant bacterial strains [22]. Additional work by Brochado et al., also highlights inter-species variation in sensitivity to therapeutic antibiotic and non-antibiotic compounds [23].

3. Ex vivo and animal models for microbiome drug metabolism research

3.1. Models of the human gastrointestinal tract

Experimental models for the study of human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) phenotypes reflect different features of the physiological complexity and biogeography of the human GIT. Defined anatomically, the GIT is a continuous tube, approximately 9 m in length in an adult human, that includes the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, cecum and rectum [24]. Microbes populate the entire GIT, from the oral cavity to colon [25]. The activity of microbes in the small (duodenum, jejunum and ileum) intestine and colon, is of particular interest for human microbiome researchers, as these are the key sites for microbial activity. Choosing an appropriate study design, based in part on how anatomical and physiological features of the colon may impact its microbial ecology, may help address the challenge of reproducing findings from model systems to human biology.

3.1.1. Ex vivo colon models

Ex vivo colon models are a powerful approach to replicate the complexity and dynamics human gut microbial communities. Batch or continuous fermentation systems replicate the anaerobic condition of the colon and allow specification of physiological parameters such as pH and dissolved oxygen [26]. A human fecal sample prepared under anaerobic conditions serves as the initial inoculum into a multichambered bioreactor. Takagi and colleagues developed a single-batch fermentation system to evaluate the effect of prebiotics on the colonic microbiota and found that supplementation with prebiotic oligosaccharides increased the abundance of the genus Bifidobacteria and acetate production [27]. Fermentation systems can be manipulated through the introduction of substrates of interest, monitored and sampled at defined timepoints. However, there are concerns about how well the fecal microbiota approximates the activity of colon. Comparative intestinal and fecal sampling in a limited number of human and primate studies identified overlapping but distinct microbial communities between the small intestine, colon and fecal community [28,29].

A second class of ex vivo colon models, enteroids and organoid cultures, replicate key host physiological features. These cultures are generated from heterogenous cell populations that self-organize into three-dimensional structures that recapitulate features of the small intestinal epithelium [30]. These systems have been employed to gain insight into host-viral and host-bacteria interactions. For example, Finkbeiner et al. established an organoid model that supported rotavirus infection after inoculation with rotavirus infected stool [31]. Forbester et al. used an intestinal organoid model to assess interactions between the enteric pathogen, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with the intestinal mucosa [32]. Enteroids and organoids suffer from overlapping disadvantages with fermentation systems in that they can take months to stabilize for use [30]. It is also challenging to mimic and culture anaerobes under the conditions necessary to support organoid and enteroid systems. For example, in an organoid model of Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection, the pathogen was viable for a maximum of 12 h [33].

3.2. Model systems in the study of microbiome-drug interactions

3.2.1. Rodent

Mouse models are considered the gold standard in terms of balancing tractability with approximating the anatomical, physiological and microbial features of human microbiomes. Both humans and mice are dominated by the microbial phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes but vary at the genus level [34,35]. However, humans have a lower glandular pH stomach, a significantly thicker layer of mucin as a part of the epithelial barrier in the colon, an appendix and a segmented colon [34,35]. As highlighted in Section 2.4, mouse models play a powerful role in confirming mechanisms of microbiome-host-drug interactions that are identified through human studies.

3.2.2. Other whole organism model systems

Scott et al., used the worm Caenorhabditis elegans to investigate the role of host-microbe co-metabolism on the efficacy of fluoropyrimidine cancer drugs and identified several mechanisms by which microbial metabolic processes shape fluoropyrimidine efficacy. Bacteria convert the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine to 5-fluorouracil and the bacterial deoxyribonucleotide pool shapes 5-fluorouracil induced autophagy [36]. The advantages of using C. elegans include its short generation time and high tractability [37]. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) represents a vertebrate model for microbiome research. Zebrafish models have been employed to study the role of microbes in development [38]. Phelps et al., used a zebrafish model to uncover a role of microbial colonization in normal neurobehavioral development [39]. These systems, while less expensive than mice and more readily genetically tractable, recapitulate neither human physiology nor microbiome composition.

4. Community level analysis of microbiome function

4.1. High throughput sequencing

Our current knowledge of the microbial inhabitants of our gut is based primarily on community level analyses. A major unmet challenge is to design species level analyses that appropriately contextualize how individual species function within a larger community and to replicate the complexity of interactions in the gut environment. Towards addressing this challenge, the use of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing and metagenomic shotgun sequencing of fecal samples can be employed to characterize the microbial community resolved at the level of species or strains and functional potential. The 16S rRNA gene has a region that is widely conserved across bacteria and a hyper-variable region that allows classification of bacteria into closely related groups. Sequences that contain similar hyper-variable regions are clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) [40]. Recently, new methods have been developed to replace OTUs with Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) as the “unit of analysis” [41].

4.1.1. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics

Taxonomic studies are thus far limited in predicting human disease and health states [42,43]. Shotgun metagenomics, an alternative approach, is the untargeted sequencing of the total DNA of a sample, providing insight into both phylogenetic diversity and the abundance of functional genes. Metatranscriptomics studies provide insight into community-level gene expression, a more direct measure of microbiome functional activity. These approaches are more expensive than 16S-based profiling and share technical and computational challenges. Assembling metagenomic and metatranscriptomics data and downstream statistical analyses to assess differences in microbial features are not standardized, contributing to variability in significant functional features between studies [42].

4.2. High throughput protein and metabolite analyses

4.2.1. Metaproteomics and metabolomics

While not yet used as a standard component of human microbiome research, metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses provide complementary and more direct insight into active functions of gut microbes than metatranscriptomic or metagenomic approaches. These analyses are based on the use of mass spectrometry coupled to a variety of front-end molecular separation approaches. Using combined and metagenomic and metaproteomic analysis Erickson et al. found significant differences in protein expression in the intestinal barrier between individuals in good health and those with Crohn's disease [44]. Microbiome studies including metabolomics have found that greater microbiota mediated p-cresol formation competitively reduced acetaminophen sulfonation and excretion in the urine, and is a key source of inter-personal variation in acetaminophen metabolism [45]. To date, targeted approaches, quantifying a defined set of metabolites, and untargeted approaches have been used to follow the fate and interplay between host and gut microbiota generated metabolites. For example, we used a combined shotgun metagenomic and targeted metabolomic approach to quantify inter-individual variability in microbiome metabolism of a glucuronidated metabolite of a chemotherapeutic drug and linked a high turnover phenotype to specific microbial β-glucuronidases [46]. There are notable bottlenecks that restrict the use of these approaches in microbiome studies including expense and the tradeoffs between efficient protein or metabolite extraction from fecal or intestinal samples while maintaining mass spectrometry sensitivity [47].

5. Computational approaches to pharmacokinetics in microbiome research

5.1. Computational approaches to pharmacokinetics in microbiome research

There are several computational approaches to model and predict drug pharmacokinetics and microbial metabolic processes that support the quantitative in silico assessment of microbiome-drug interactions. These approaches, which most notably include physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, rely on data gathered from high throughput sequencing and analytical chemistry approaches.

5.1.1. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models

PBPK models represent whole body drug kinetics with differential equations [48]. The model system is defined by compartments corresponding to specific tissues of the body such as the liver, kidney, gut, or lung. System-specific parameters are derived from experimental data such as enzyme and transporter expression, organ volumes and blood flow. Drug-specific parameters include drug physiochemical properties and tissue permeability. Traditionally these models exclusively modelled human metabolism; however, several studies have included microbial enzymes among the system-specific parameters. For example, Boajian Wu developed a PBPK model to evaluate the impact of GIT glucuronide hydrolysis of SN-38 Glucuronide, a key inactive metabolite of the chemotherapeutic irinotecan, on the pharmacokinetic profile of the active compound, SN-38. In this two-compartment model, encompassing the liver and gut, Wu found GIT microbial β-glucuronidase activity increased intestinal exposure to SN-38 but not systemic exposure [49]. Recently, Zimmermann et al., used gnotobiotic mouse studies involving a specific gut colonist that varied in its encoding of single enzymes to quantify brivudine metabolism in vivo and to construct a pharmacokinetic model to quantitatively predict microbiome contributions to systemic drug and metabolite exposure and to distinguish host and microbe contributions [50].

5.1.2. Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA)

COBRA methods use formalized metabolic models to simulate, analyze and predict metabolic phenotypes including how microbes utilize various metabolic processes, host-microbe interactions and microbe-microbe interactions [51,52]. In the context of drug metabolism, Swagatika et al., employed COBRA methods to model the effects of commonly used drugs, including statins, anti-hypertensives, analgesics and immunosuppressants, on human metabolism [53]. They found that diet shapes human metabolism and elimination of acetaminophen and statins [53]. In particular, a low L-cysteine vegetarian diet resulted in a reduction in sulfation and excretion of acetaminophen metabolites. Reduced sulfation can be attributed to low levels of sulfur containing compounds such as L-cysteine, which contributes to the biosynthesis of a critical co-factor, phosphoadenylyl sulfate, for sulfation reactions [53].

There have been notable efforts to integrate the strengths of PBPK and COBRA methods [54,55]. Krauss et al., combined COBRA and PBPK methods to more accurately predict allopurinol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Allopurinol is a preventative antigout medication that prevents increases in uric acid levels and alters gut microbiota composition [56]. The authors predicted the pharmacological effects of allopurinol on the biosynthesis of uric acid and reported a 69.3% decrease in uric acid concentrations which is supported by clinical data [55]. Future use of these approaches will enable both a systems level and targeted mechanistic understanding of host-microbiome metabolism.

6. Bringing insights from microbiome-drug interaction studies into the clinic

6.1. Microbiome metabolic phenotyping

The impact of the microbiome on the efficacy and toxicity of the chemotherapeutic irinotecan and the cardiac drug digoxin are relatively well characterized (Fig. 1b). In the case of metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving irinotecan (CPT-11), microbial β-glucuronidases hydrolyze the glucuronide group from the major inactive metabolite of CPT-11, SN-38 glucuronide. A build-up of SN-38 in the colon causes epithelial cell damage that contributes to severe diarrhea in some patients [15,57]. Using a combined shotgun metagenomics and targeted metabolomics approach, a group previously identified a phylogenetically diverse set of bacterial β-glucuronidases and transporter proteins that are associated with high turnover of SN-38 glucuronide and a potentially elevated risk of irinotecan dependent toxicity [46]. Defining the metabolic and metagenomic basis of variability in drug metabolism using ex vivo incubations of drugs with human fecal samples may suggest putative biomarkers of a patient's risk of poor drug efficacy and safety.

6.2. Developing drug metabolism classifiers

To date metabolic phenotyping studies of microbe-drug interactions pairing DNA or RNA high throughput sequencing with metabolomics reveal that the level of gut microbiome complexity linked to drug metabolism varies between drugs [45,46,58]. A major hurdle is understanding what microbiome features identified through these preclinical studies, using model systems or human fecal samples as a proxy for the gut microbiome, will translate into accurate surrogate endpoints for clinical studies. For example, the presence or absence of a particular microbe or enzyme in a sequenced fecal sample may not have the power to predict drug metabolism.

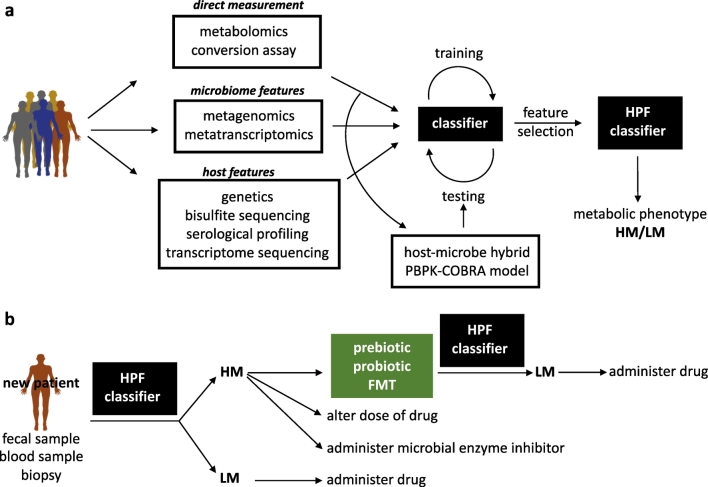

One approach to overcome this hurdle is to combine features using machine learning to identify the combinations of features most strongly predictive of drug metabolism. One such supervised learning approach is the “random forest” [59,60] method, which can be used to combine chemical, molecular, and clinical features. Initially one could define drug metabolism as a binary value where every sample is labeled as either “high” or “low” based on drug concentrations in a fecal sample from a patient. A receiver-operator curve plotting true-positive and false-positive rates can then be used to assess performance on different combinations of feature sets [61]. To target specific features that drive predictions one can calculate the importance of individual features to prediction accuracy by calculating the mean decrease in accuracy per feature [60]. This analysis outputs the highest performing feature set and classifier to be used with future patient data for a given drug (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pipeline for metabolic phenotyping and modulation of microbiome driven adverse drug responses.

a The construction of a high performance classier (HPC) to distinguish high drug metabolizers (HM) from low drug metabolizers (LM). For patients treated with therapeutic drugs that are susceptible to glucuronidation, such as irinotecan and NSAIDs, being a HM may reflect an elevated risk for drug-dependent toxicity. The main steps for metabolically phenotyping of HM and LM patients include data aggregation and preparation as input features for classifier training and testing, followed by the selection of key features that predict outcome and evaluation of classifier performance. The feature space for the classifier can be derived from preclinical and clinical studies and might include multi'omic data derived from both microbiome and host studies. This data can be integrated into hybrid COBRA-PBPK models to gain further predictive and mechanistic insight into drug pharmacokinetic profiles and aid in the identification of key host and microbiome parameters. b The HPC can be used to stratify new patients taking susceptible therapeutics into either HM or LM ‘metabotypes’ based on non-invasive fecal sampling alone or in addition to host biological samples. HM patients may undergo pre-treatment therapy, ranging from the use of probiotics and prebiotics to FMT, to modulate the microbiome towards a LM profile and improved treatment efficacy and safety.

6.3. Clinical trials

6.3.1. CPT-11

There are a number of clinical trials investigating the efficacy of probiotics to modulate microbiome-dependent adverse drug responses. A randomized, double blind design was carried out to investigate the potential for probiotic use to minimize CPT-11 induced toxicity. Patients were randomized in to a probiotic group (PRO) and a placebo group (PLA). 39% of patients in the PRO group experienced grade 3–4 diarrhea while 61% of participants in the PLA group experienced diarrhea (Table 1) [62]. Future studies of a similar design may also address how diet influences microbiome β-glucuronidase activity and patient toxicity by including metagenomics or metatranscriptomic sequencing from fecal samples to assess microbiome function.

Table 1.

Clinical trials investigating microbiome intervention and profiling approaches to improve drug efficacy and safety.

| Drug (s) | ATC Classification | Target Outcome | Microbiome Intervention | Phase | N | NCT | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthohumol | Anti-cholesterol, Anti-inflammatory | Establish PK | Microbiome profiling | 1 | 32 | NCT03735420 | Not yet recruiting |

| Metronidazole | Anti-infective | ↑ Efficacy | Probiotic: Lactobacillus GG | 4 | 0 | NCT00304863 | Withdrawn |

| Antibiotic-unspecified | Antibiotic | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: BioGaia Lactobacillus reuteri | NA | 73 | NCT02127814 | Completed |

| Irinotecan | Antineoplastic agents | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: PROBIO-FIX INUM | 3 | 100 | NCT02819960 | Recruiting |

| Irinotecan | Antineoplastic agents | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: Colon DophilusTM | 3 | 46 | NCT01410955 | Completed |

| Irinotecan | Antineoplastic agents | ↓ Toxicity | Antibacterial: Cefpodoxime | 1 | 20 | NCT00143533 | Completed |

| VEGF-TKI | Antineoplastic agents | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: Activia yogurt containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173010) | NA | 20 | NCT02944617 | Recuriting |

| Dacomitinib | Antineoplastic agents | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: VSL 3 | 2 | 236 | NCT01465802 | Completed |

| Tenofovir | Antiviral | ↑ Efficacy and Safety | Fecal Microbiota Transplant | NA | 64 | NCT02689245 | Completed |

| Chemotherapy-unspecified | Chemotherapy-unspecified | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: VSL 3 | NA | 20 | NCT03704727 | Recruiting |

| Tacrolimus | Immunosuppreseant | ↑ Efficacy and Safety | Microbiome profiling | 4 | 148 | NCT02498977 | Recruiting |

| Pembrolizumab | Monoclonal antibody | ↑ Efficacy | Fecal Microbiota Transplant | 2 | 20 | NCT0334113 | Recuriting |

| Aspirin | NSAID | ↓ Toxicity | Probiotic: | 2 | 109 | NCT03228589 | Completed |

| Aspirin | NSAID | ↓ Toxicity | Microbiome profiling | NA | 100 | NCT03450317 | Recruiting |

Recent efforts to reduce CPT-11 toxicity also include targeted inhibition of microbial enzymes that convert the inactive form of the drug to its active form. Wallace et al., 2010, identified potent Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase inhibitors which substantially reduce CPT-11 induced toxicity in mice while having no effect on the orthologous mammalian enzyme [15]. A clinical trial establishing the safety and efficacy of this approach in human population has the potential to yield valuable insight into the efficacy of targeted, small molecule modulators of specific microbiome functions.

6.3.2. Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressant commonly used for kidney transplant recipients. A narrow therapeutic range limits its efficacy: underexposure increases the risk of graft rejection and over-exposure increases the risk of drug-related toxicity [63]. An ongoing clinical trial focused on identifying biomarkers of successful discontinuation of immunosuppressants including tacrolimus for patients with liver disease, includes microbiome profiling as a secondary outcome measure for a trial (Table 1). However, preclinical research provides compelling evidence of a role of the gut microbiota in patient outcomes.

In a pilot study of kidney transplant recipients, patients who required a 50% increase in the standard dose of tacrolimus to maintain therapeutic levels had a greater abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [64]. Subsequently, Guo et al., reported that tacrolimus is converted into less potent metabolites by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and other Clostridiales in monocultures as well as by the fecal microbiota from healthy individuals [65]. Given that the host physiological and pharmacokinetic parameters relating to tacrolimus are well defined, including the identification of host CYP3A4*22 and CYP3A5*3 polymorphisms linked to variable tacrolimus levels [66], there is an opportunity to integrate known data regarding host and microbe metabolism of the drug into an integrated PBPK and COBRA model.

6.3.3. Xanthohumol

Xanthohumol is a prenylated flavonoid and promising anti-cholesterol and anti-inflammatory candidate therapeutic. The mechanisms for its antiatherogenic properties are diverse and include the inhibition of triglyceride synthesis, prevention of low density lipoprotein oxidation and the promotion of reverse cholesterol transport in macrophages [67,68]. In vitro, xanthohumol has strong antimicrobial activity against Bacteroides fragilis and toxigenic, clinically relevant, strains of C.difficile [69]. Microbial metabolism has been linked to the bioactivity and toxicity of xanthohumol. For example, the gut microbiota converts xanthohumol into 8-prenylnaringenin, an estrogenic phytoestrogen, and then further metabolizes the compound into less potent end products [70]. Eubacterium ramulus, from the abundant human microbiome genus Eubacterium, metabolizes xanthohumol extensively in vitro70. How the microbiome contributes to xanthohumol efficacy and toxicity is the focus of an ongoing Phase I randomized, interventional clinical trial (Table 1).

7. Conclusions and future prospects

The extent to which the gut microbiome influences variability in population level therapeutic drug efficacy and toxicity is unknown. Furthermore, we have limited insight into the underlying mechanisms, enzymes, metabolites and species that play key roles in microbiome-drug interactions. A broader map of the metabolic potential of gut microbes will support the development of predictive models of how drugs and foods are modified by the host microbiome, enabling crucial insight into the microbial enzymes and pathways that are responsive to drugs.

Collectively, mechanistic animal model studies, high throughput sequencing and computational approaches used to investigate the microbiome-drug interactions, represent a pipeline for the prediction and modulation of gut microbiome driven adverse drug responses in the clinic (Fig. 2). A shift away from snapshot study designs towards longitudinal human studies that monitor microbiome function over time and at varying levels of granularity may accelerate our discovery of population-level variability in drug response. Longitudinal study designs, depending on their resolution, offer unique insights into how microbial communities respond to a particular perturbation [71].

8. Outstanding questions

Among the outstanding questions to address through preclinical studies and randomized clinical trials are: Is a patient's pre-treatment microbiome predictive of her drug response outcome? What microbiome features are most predictive? What is the temporal stability of patient microbiome phenotypes? How does diet and antibiotic use impact therapeutic drug treatment? What host factors are key modulators of microbiome activity that may shape drug response outcomes? Addressing these questions will enable us to reengineer microbial interactions to better promote drug safety and efficacy.

9. Search strategies and selection criteria

Clinical trial data for this review was identified by searches of ClinicalTrials.gov in addition to PubMed and references from relevant articles using the search terms “microbiome”, “microbiota”, “drug”, “metabolism”, “drug treatment”, “gene expression”, “metagenomics”, “prebiotic”, “probiotic”, “intervention”,“16 s” and “NOT ‘review’[Publication Type]”. Only articles published in English between 2010 and 2019 were included with an exception for those introducing key terms for the first time; preference was given to articles published between 2016 and 2019.

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Guthrie has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kelly has nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program Career Development Award from the United States Department of Defense to Libusha Kelly (CA171019); Leah Guthrie was supported by the predoctoral Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology and Genetics 5T32GM007491-41. The funders had no role in writing the paper.

References

- 1.Wilson I.D., Nicholson J.K. Gut microbiome interactions with drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity. Transl Res. 2017;179:204–222. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wilson, I. D. & Nicholson, J. K. Gut microbiome interactions with drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity. Transl. Res. 179, 204–222 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Spanogiannopoulos P., Bess E.N., Carmody R.N., Turnbaugh P.J. The microbial pharmacists within us: a metagenomic view of xenobiotic metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:273–287. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Spanogiannopoulos, P., Bess, E. N., Carmody, R. N. & Turnbaugh, P. J. The microbial pharmacists within us: a metagenomic view of xenobiotic metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 273–287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kuntz T.M., Gilbert J.A. Introducing the microbiome into precision medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kuntz, T. M. & Gilbert, J. A. Introducing the Microbiome into Precision Medicine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 81–91 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Aziz R.K. 2012. Rethinking pharmacogenomics in an ecosystem: Drug-microbiome interactions, Pharmacomicrobiomics, and personalized medicine for the human Supraorganism; pp. 258–261. [Google Scholar]; Aziz, R. K. Rethinking Pharmacogenomics in an Ecosystem: Drug-microbiome Interactions, Pharmacomicrobiomics, and Personalized Medicine for the Human Supraorganism. 258–261 (2012).

- 5.Lankisch T.O. Gilbert's syndrome and Irinotecan toxicity: combination with UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1A7 variants increases risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:695–701. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lankisch, T. O. et al. Gilbert'’s Syndrome and Irinotecan Toxicity: Combination with UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1A7 Variants Increases Risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17, 695–701 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Stingl J.C., Bartels H., Viviani R., Lehmann M.L., Brockmöller J. Relevance of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase polymorphisms for drug dosing: a quantitative systematic review. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:92–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stingl, J. C., Bartels, H., Viviani, R., Lehmann, M. L. & Brockmöller, J. Relevance of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase polymorphisms for drug dosing: A quantitative systematic review. Pharmacol. Ther. 141, 92–116 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gammal R.S. Clinical Pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for UGT1A1 and Atazanavir prescribing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:363–369. doi: 10.1002/cpt.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gammal, R. S. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for UGT1A1 and Atazanavir Prescribing. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 99, 363–369 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Moaddeb J., Haga S.B. Pharmacogenetic testing: current evidence of clinical utility. Ther Adv drug Saf. 2013;4:155–169. doi: 10.1177/2042098613485595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Moaddeb, J. & Haga, S. B. Pharmacogenetic testing: Current Evidence of Clinical Utility. Ther. Adv. drug Saf. 4, 155–169 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Scordo M. Influence of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on warfarin maintenance dose and metabolic clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:702–710. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Scordo, M. et al. Influence of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on warfarin maintenance dose and metabolic clearance. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 72, 702–710 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ventola C.L. Pharmacogenomics in clinical practice: reality and expectations. P T. 2011;36:412–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ventola, C. L. Pharmacogenomics in clinical practice: reality and expectations. P T 36, 412–50 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Phillips K.A., Veenstra D.L., Oren E., Lee J.K., Sadee W. Potential role of pharmacogenomics in reducing adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. JAMA. 2001;286:2270–2279. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Phillips, K. A., Veenstra, D. L., Oren, E., Lee, J. K. & Sadee, W. Potential role of pharmacogenomics in reducing adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. JAMA 286, 2270–9 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Rizkallah M., Saad R., Aziz R. The human microbiome project, personalized medicine and the birth of Pharmacomicrobiomics. Curr Pharmacogenomics Person Med. 2010;8:182–193. [Google Scholar]; Rizkallah, M., Saad, R. & Aziz, R. The Human Microbiome Project, Personalized Medicine and the Birth of Pharmacomicrobiomics. Curr. Pharmacogenomics Person. Med. 8, 182–193 (2010).

- 13.Saad R., Rizkallah M.R., Aziz R.K. Gut Pharmacomicrobiomics: the tip of an iceberg of complex interactions between drugs and gut-associated microbes. Gut Pathog. 2012;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Saad, R., Rizkallah, M. R. & Aziz, R. K. Gut Pharmacomicrobiomics: the tip of an iceberg of complex interactions between drugs and gut-associated microbes. Gut Pathog. 4, 16 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.ElRakaiby M. Pharmacomicrobiomics: the impact of human microbiome variations on systems pharmacology and personalized therapeutics. OMICS. 2014;18:402–414. doi: 10.1089/omi.2014.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ElRakaiby, M. et al. Pharmacomicrobiomics: the impact of human microbiome variations on systems pharmacology and personalized therapeutics. OMICS 18, 402–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wallace B.D. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science. 2010;330:831–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1191175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wallace, B. D. et al. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 330, 831–5 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wilkinson G.R. Drug metabolism and variability among patients in drug response. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2211–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wilkinson, G. R. Drug Metabolism and Variability among Patients in Drug Response. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2211–2221 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Devlin A.S. Modulation of a circulating uremic solute via rational genetic manipulation of the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Devlin, A. S. et al. Modulation of a Circulating Uremic Solute via Rational Genetic Manipulation of the Gut Microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 20, 709–715 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Björkholm B. Intestinal microbiota regulate xenobiotic metabolism in the liver. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Björkholm, B. et al. Intestinal Microbiota Regulate Xenobiotic Metabolism in the Liver. PLoS One 4, e6958 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Barnes K.J., Rowland A., Polasek T.M., Miners J.O. Inhibition of human drug-metabolising cytochrome P450 and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme activities in vitro by uremic toxins. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:1097–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Barnes, K. J., Rowland, A., Polasek, T. M. & Miners, J. O. Inhibition of human drug-metabolising cytochrome P450 and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme activities in vitro by uremic toxins. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 1097–1106 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sun L. Gut microbiota and intestinal FXR mediate the clinical benefits of metformin. Nat Med. 2018;24:1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sun, L. et al. Gut microbiota and intestinal FXR mediate the clinical benefits of metformin. Nat. Med. 24, 1919–1929 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wu H. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat Med. 2017;23:850–858. doi: 10.1038/nm.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu, H. et al. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat. Med. 23, 850–858 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Maier L. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018 doi: 10.1038/nature25979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature (2018). doi:10.1038/nature25979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Brochado A.R. Species-specific activity of antibacterial drug combinations. Nature. 2018;559:259–263. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0278-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brochado, A. R. et al. Species-specific activity of antibacterial drug combinations. Nature 559, 259–263 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Valentin J.P. vol. 229. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2015. Handbook of experimental pharmacology; pp. 291–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; .Valentin, J.P. et al. in Handbook of experimental pharmacology 229, 291–321 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Hillman E.T., Lu H., Yao T., Nakatsu C.H. Microbial ecology along the gastrointestinal tract. Microbes Environ. 2017;32:300–313. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME17017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hillman, E. T., Lu, H., Yao, T. & Nakatsu, C. H. Microbial Ecology along the Gastrointestinal Tract. Microbes Environ. 32, 300–313 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.O'Donnell M.M., Rea M.C., Shanahan F., Ross R.P. The use of a mini-bioreactor fermentation system as a reproducible, high-throughput ex vivo batch model of the distal Colon. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1844. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; O'’Donnell, M. M., Rea, M. C., Shanahan, F. & Ross, R. P. The Use of a Mini-Bioreactor Fermentation System as a Reproducible, High-Throughput ex vivo Batch Model of the Distal Colon. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1844 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Takagi R. A single-batch fermentation system to simulate human colonic microbiota for high-throughput evaluation of prebiotics. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Takagi, R. et al. A Single-Batch Fermentation System to Simulate Human Colonic Microbiota for High-Throughput Evaluation of Prebiotics. PLoS One 11, e0160533 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Yasuda K. Biogeography of the intestinal mucosal and Lumenal microbiome in the rhesus macaque. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yasuda, K. et al. Biogeography of the Intestinal Mucosal and Lumenal Microbiome in the Rhesus Macaque. Cell Host Microbe 17, 385–391 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Durbán A. Assessing gut microbial diversity from Feces and rectal mucosa. Microb Ecol. 2011;61:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9738-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Durbán, A. et al. Assessing Gut Microbial Diversity from Feces and Rectal Mucosa. Microb. Ecol. 61, 123–133 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Blutt S.E., Crawford S.E., Ramani S., Zou W.Y., Estes M.K. Engineered human gastrointestinal cultures to study the microbiome and infectious diseases. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Blutt, S. E., Crawford, S. E., Ramani, S., Zou, W. Y. & Estes, M. K. Engineered Human Gastrointestinal Cultures to Study the Microbiome and Infectious Diseases. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 241–251 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Finkbeiner S.R. Stem cell-derived human intestinal Organoids as an infection model for rotaviruses. MBio. 2012;3 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00159-12. e00159-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; .Finkbeiner, S. R. et al. Stem Cell-Derived Human Intestinal Organoids as an Infection Model for Rotaviruses. MBio 3, e00159-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Forbester J.L. Interaction of salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium with intestinal Organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2926–2934. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00161-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Forbester, J. L. et al. Interaction of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium with Intestinal Organoids Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Infect. Immun. 83, 2926–2934 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Leslie J.L. Persistence and toxin production by Clostridium difficile within human intestinal organoids result in disruption of epithelial paracellular barrier function. Infect Immun. 2015;83:138–145. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02561-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Leslie, J. L. et al. Persistence and toxin production by Clostridium difficile within human intestinal organoids result in disruption of epithelial paracellular barrier function. Infect. Immun. 83, 138–45 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Nguyen T.L.A., Vieira-Silva S., Liston A., Raes J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:1–16. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nguyen, T. L. A., Vieira-Silva, S., Liston, A. & Raes, J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis. Model. Mech. 8, 1–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hildebrand F. Inflammation-associated enterotypes, host genotype, cage and inter-individual effects drive gut microbiota variation in common laboratory mice. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hildebrand, F. et al. Inflammation-associated enterotypes, host genotype, cage and inter-individual effects drive gut microbiota variation in common laboratory mice. Genome Biol. 14, R4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Scott T.A. Host-microbe co-metabolism dictates cancer drug efficacy in C. elegans. Cell. 2017;169 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Scott, T. A. et al. Host-Microbe Co-metabolism Dictates Cancer Drug Efficacy in C. elegans. Cell 169, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Norvaisas P., Cabreiro F. Pharmacology in the age of the holobiont. Curr Opin Syst Biol. 2018;10:34–42. [Google Scholar]; Norvaisas, P. & Cabreiro, F. Pharmacology in the age of the holobiont. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 10, 34–42 (2018).

- 38.Stephens W.Z. The composition of the zebrafish intestinal microbial community varies across development. ISME J. 2016;10:644–654. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stephens, W. Z. et al. The composition of the zebrafish intestinal microbial community varies across development. ISME J. 10, 644–54 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Phelps D. Microbial colonization is required for normal neurobehavioral development in zebrafish. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10517-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Phelps, D. et al. Microbial colonization is required for normal neurobehavioral development in zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 7, 11244 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Morgan X.C., Huttenhower C. Meta'omic analytic techniques for studying the intestinal microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1437–1448.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morgan, X. C. & Huttenhower, C. Meta'’omic analytic techniques for studying the intestinal microbiome. Gastroenterology 146, 1437–1448.e1 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Holmes S.P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 2017;11:2639–2643. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 11, 2639–2643 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Schloss P.D. Identifying and overcoming threats to reproducibility, Replicability, robustness, and generalizability in microbiome research. MBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00525-18. e00525-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Schloss, P. D. Identifying and Overcoming Threats to Reproducibility, Replicability, Robustness, and Generalizability in Microbiome Research. MBio 9, e00525-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Jansson J.K., Baker E.S. A multi-omic future for microbiome studies. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jansson, J. K. & Baker, E. S. A multi-omic future for microbiome studies. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16049 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Erickson A.R. Integrated Metagenomics/Metaproteomics reveals human host-microbiota signatures of Crohn's disease. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Erickson, A. R. et al. Integrated Metagenomics/Metaproteomics Reveals Human Host-Microbiota Signatures of Crohn'’s Disease. PLoS One 7, e49138 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Clayton T.A., Baker D., Lindon J.C., Everett J.R., Nicholson J.K. Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14728–14733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904489106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clayton, T. A., Baker, D., Lindon, J. C., Everett, J. R. & Nicholson, J. K. Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 14728–33 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Guthrie L., Gupta S., Daily J., Kelly L. Human microbiome signatures of differential colorectal cancer drug metabolism. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2017;3(27) doi: 10.1038/s41522-017-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Guthrie, L., Gupta, S., Daily, J. & Kelly, L. Human microbiome signatures of differential colorectal cancer drug metabolism. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 3, 27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Petriz B.A., Franco O.L. Metaproteomics as a complementary approach to gut microbiota in health and disease. Front Chem. 2017;5(4) doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Petriz, B. A. & Franco, O. L. Metaproteomics as a Complementary Approach to Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease. Front. Chem. 5, 4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Schellenberger J. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA toolbox v2.0. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1290–1307. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Schellenberger, J. et al. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox v2.0. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1290–1307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Wu B. Use of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models to evaluate the impact of intestinal glucuronide hydrolysis on the pharmacokinetics of aglycone. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1281–1301. doi: 10.1002/jps.22827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wu, B. Use of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models to evaluate the impact of intestinal glucuronide hydrolysis on the pharmacokinetics of aglycone. J. Pharm. Sci. 101, 1281–301 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Zimmermann M., Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M., Wegmann R., Goodman A.L. Separating host and microbiome contributions to drug pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Science. 2019;363 doi: 10.1126/science.aat9931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; .Zimmermann, M., Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M., Wegmann, R. & Goodman, A. L. Separating host and microbiome contributions to drug pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Science 363, eaat9931 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Babaei P., Shoaie S., Ji B., Nielsen J. Challenges in modeling the human gut microbiome. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:682–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Babaei, P., Shoaie, S., Ji, B. & Nielsen, J. Challenges in modeling the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 682–686 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Becker S.A. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA toolbox. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Becker, S. A. et al. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox. Nat. Protoc. 2, 727–738 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Sahoo S., Haraldsd H.S., Fleming R.M.T., Thiele I. 2018. Modeling the effects of commonly used drugs on human metabolism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sahoo, S., Haraldsd, H. S., Fleming, R. M. T. & Thiele, I. Modeling the effects of commonly used drugs on human metabolism. doi:10.1111/febs.13128 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Thiele I., Clancy C.M., Heinken A., Fleming R.M.T. Quantitative systems pharmacology and the personalized drug–microbiota–diet axis. Curr Opin Syst Biol. 2017;4:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Thiele, I., Clancy, C. M., Heinken, A. & Fleming, R. M. T. Quantitative systems pharmacology and the personalized drug–microbiota–diet axis. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 4, 43–52 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Krauss M. Integrating cellular metabolism into a multiscale whole-body model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Krauss, M. et al. Integrating Cellular Metabolism into a Multiscale Whole-Body Model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002750 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Yu Y., Liu Q., Li H., Wen C., He Z. Alterations of the gut microbiome associated with the treatment of hyperuricaemia in male rats. Front Microbiol. 2018;9(2233) doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yu, Y., Liu, Q., Li, H., Wen, C. & He, Z. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome Associated With the Treatment of Hyperuricaemia in Male Rats. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2233 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Wallace B.D. Structure and inhibition of microbiome β-glucuronidases essential to the alleviation of cancer drug toxicity. Chem Biol. 2015;22:1238–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; .Wallace, B. D. et al. Structure and Inhibition of Microbiome β-Glucuronidases Essential to the Alleviation of Cancer Drug Toxicity. Chem. Biol. 22, 1238–49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Haiser H.J. Predicting and manipulating cardiac drug inactivation by the human gut bacterium Eggerthella lenta. Science (80-) 2013;341:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1235872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Haiser, H. J. et al. Predicting and Manipulating Cardiac Drug Inactivation by the Human Gut Bacterium Eggerthella lenta. Science (80-.). 341, 295–298 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Team, R. D. C . 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]; Team, R. D. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2013).

- 60.Liaw A., Wiener M. Classification and regression by random forest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]; Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2, 18–22 (2002).

- 61.Sing T., Sander O., Beerenwinkel N., Lengauer T. ROCR: visualizing classifier performance in R. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:7881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sing, T., Sander, O., Beerenwinkel, N. & Lengauer, T. ROCR: visualizing classifier performance in R. Bioinformatics 21, 7881 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Mego M. Prevention of irinotecan induced diarrhea by probiotics: a randomized double blind, placebo controlled pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mego, M. et al. Prevention of irinotecan induced diarrhea by probiotics: A randomized double blind, placebo controlled pilot study. Complement. Ther. Med. 23, 356–362 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Shrestha B.M. Two decades of tacrolimus in renal transplant: basic science and clinical evidences. Exp Clin Transplant. 2017;15:1–9. doi: 10.6002/ect.2016.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shrestha, B. M. Two Decades of Tacrolimus in Renal Transplant: Basic Science and Clinical Evidences. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 15, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Lee J.R. Gut microbiota and tacrolimus dosing in kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lee, J. R. et al. Gut Microbiota and Tacrolimus Dosing in Kidney Transplantation. PLoS One 10, e0122399 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Guo Y. Commensal gut Bacteria convert the immunosuppressant tacrolimus to less potent metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47:194–202. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.084772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Guo, Y. et al. Commensal Gut Bacteria Convert the Immunosuppressant Tacrolimus to Less Potent Metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 47, 194–202 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Størset E. Improved prediction of tacrolimus concentrations early after kidney transplantation using theory-based pharmacokinetic modelling. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:509–523. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Størset, E. et al. Improved prediction of tacrolimus concentrations early after kidney transplantation using theory-based pharmacokinetic modelling. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 78, 509–23 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Miranda C.L. Xanthohumol improves dysfunctional glucose and lipid metabolism in diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;599:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Miranda, C. L. et al. Xanthohumol improves dysfunctional glucose and lipid metabolism in diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 599, 22–30 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Hirata H. Xanthohumol, a hop-derived prenylated flavonoid, promotes macrophage reverse cholesterol transport. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;47:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hirata, H. et al. Xanthohumol, a hop-derived prenylated flavonoid, promotes macrophage reverse cholesterol transport. J. Nutr. Biochem. 47, 29–34 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Cermak P. Strong antimicrobial activity of xanthohumol and other derivatives from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) on gut anaerobic bacteria. APMIS. 2017;125:1033–1038. doi: 10.1111/apm.12747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cermak, P. et al. Strong antimicrobial activity of xanthohumol and other derivatives from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) on gut anaerobic bacteria. APMIS 125, 1033–1038 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Paraiso I.L. Reductive metabolism of Xanthohumol and 8-Prenylnaringenin by the intestinal bacterium Eubacterium ramulus. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:1800923. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Paraiso, I. L. et al. Reductive Metabolism of Xanthohumol and 8-Prenylnaringenin by the Intestinal Bacterium Eubacterium ramulus. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 63, 1800923 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.David L.A. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Kim D.-H. Special section on drug metabolism and the microbiome-perspective gut microbiota-mediated drug-antibiotic interactions. DRUG Metab Dispos Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:1581–1589. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.063867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kim, D.-H. Special Section on Drug Metabolism and the Microbiome-Perspective Gut Microbiota-Mediated Drug-Antibiotic Interactions. DRUG Metab. Dispos. Drug Metab Dispos 43, 1581–1589 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Klotz U., Maier K., Fischer C., Heinkel K. Therapeutic efficacy of sulfasalazine and its metabolites in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1499–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012253032602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klotz, U., Maier, K., Fischer, C. & Heinkel, K. Therapeutic Efficacy of Sulfasalazine and Its Metabolites in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn'’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 303, 1499–1502 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Lindenbaum J., Rund D.G., Butler V.P., Tse-Eng D., Saha J.R. Inactivation of digoxin by the gut flora: reversal by antibiotic therapy. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:789–794. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198110013051403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lindenbaum, J., Rund, D. G., Butler, V. P., Tse-Eng, D. & Saha, J. R. Inactivation of Digoxin by the Gut Flora: Reversal by Antibiotic Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 305, 789–794 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.McQuade R.M., Bornstein J.C., Nurgali K. Anti-colorectal cancer chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea: current treatments and side-effects. Int J Clin Med. 2014;5:393–406. [Google Scholar]; McQuade, R. M., Bornstein, J. C. & Nurgali, K. Anti-Colorectal Cancer Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhoea: Current Treatments and Side-Effects. Int. J. Clin. Med. 5, 393–406 (2014).