Abstract

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) graft rupture occurs at a high rate, especially in young athletes. The geometries of the tibial plateau and femoral intercondylar notch are risk factors for first-time ACL injury; however, little is known about the relationship between these geometries and risk of ACL graft rupture.

Hypothesis

The geometric risk factors for noncontact graft rupture are similar to those previously identified for first-time noncontact ACL injury, and sex-specific differences exist.

Study Design

Case-control study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods

Eleven subjects who suffered a noncontact ACL graft rupture and 44 subjects who underwent ACL reconstruction but did not experience graft rupture were included in the study. Using magnetic resonance imaging, the geometries of the tibial plateau subchondral bone, articular cartilage, meniscus, tibial spines, and femoral notch were measured. Risk factors associated with ACL graft rupture were identified using Cox regression.

Results

The following were associated with increased risk of ACL graft injury in males: increased posterior-inferior-directed slope of the articular cartilage in the lateral tibial plateau measured at 2 locations (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.50, P = .029; HR = 1.39, P = .006), increased volume (HR = 1.45, P = .01) and anteroposterior length (HR = 1.34, P = .0023) of the medial tibial spine, and increased length (HR = 1.18, P = .0005) and mediolateral width (HR = 2.19, P = .0004) of the lateral tibial spine. In females, the following were associated with increased risk of injury: decreased volume (HR = 0.45, P = .02) and height (HR = 0.46, P = .02) of the medial tibial spine, decreased slope of the lateral tibial subchondral bone (HR = 0.72, P = .01), decreased height of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (HR = 0.09, P = .001), and decreased intercondylar notch width at the anterior attachment of the ACL (HR = 0.72, P = .02).

Conclusion

The geometric risk factors for ACL graft rupture are different for males and females. For females, a decreased femoral intercondylar notch width and a decreased height of the posterior medial meniscus were risk factors for ACL graft rupture that have also been found to be risk factors for first-time injury. There were no risk factors in common between ACL graft injury and first-time ACL injury for males.

Keywords: ACL, knee, biomechanics, injury prevention

Even after surgical reconstruction, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture has been associated with abnormal knee biomechanics4 and the development of degenerative changes within the knee.15,27,32,35,51,53 Patients who suffer an additional injury to their ACL graft sustain more pronounced chondral injuries and report more inferior clinical outcomes than do subjects who only sustain 1 ACL injury.1,8,58 In the general population (ages 13–62 years), reports estimate that ACL graft failure occurs at a rate of about 4.4% at 2-year follow-up, 7% at 5-year follow-up, and 11% at 15-year follow-up,7,23 thus causing the individual to undergo repeated surgery and rehabilitation. In the young (16 ± 3 years) athletic population, the reinjury rate has been reported as being 9% at 2 years after ACL reconstruction (ACLR).34

Several geometric characteristics of the knee have been identified as risk factors for first-time ACL injury, including decreased femoral intercondylar notch width, increased posterior-inferior-directed slope of the tibial articular cartilage surface and subchondral bone, decreased ACL volume, and decreased tibial spine volume.¶ Notably, these geometric factors appear to be different between males and females.45 Although risk factors for first-time ACL injury have been identified, risk factors for ACL graft injury have not been as thoroughly investigated.

Thus far, much of the previous work that has focused on identifying the risk factors for ACL graft rupture has been based on descriptive epidemiology.7,20,23,25,28,38,39,55 One of the risk factors for ACL graft rupture is younger age at the time of ACL injury.13,20,23,39,55 Related to this is the finding that increased activity level and return to sport have also been reported as risk factors for ACL graft injury.23,55 Age as a risk factor represents a cause for concern as the population at greatest risk for first-time ACL injury is composed of young athletes.18 Several studies have identified that male subjects undergo a higher rate of revision ACLR than do females.25,28,39,49 In addition, a family history of ACL injury may double the risk of ACL graft rupture.7,55

Geometric characteristics of the knee associated with ACL graft injury have been the subject of far less study. Wolf et al57 measured the outlet of the femoral intercondylar notch intraoperatively using a handheld caliper and found that the femoral outlet width was not associated with risk of ACL graft failure. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–based measurements of the geometry of the femoral intercondylar notch have been shown to be associated with increased risk of suffering a firsttime ACL injury.12,41,56 MRI may serve as a more precise and reproducible method of evaluating the intercondylar notch geometry. Webb et al54 found that subjects suffering a contralateral ACL or ipsilateral graft injury after ACLR were more likely to have an increased posterior-inferior-directed tibial plateau slope in the lateral compartment than were those who did not suffer a reinjury. However, there was no significant difference when ACL graft ruptures were analyzed as a group distinct from contralateral injuries. Using MRI data, Christensen et al10 found that an increased posterior-inferior–directed tibial plateau slope in the lateral compartment was a risk factor for ACL graft injury in a combined male and female and a female-specific analysis of subjects within 2 years after ACLR.

To our knowledge, no study has determined the comprehensive characteristics of knee joint geometry that are predictive of the risk of ACL graft rupture. As such, the purpose of this investigation was to determine the geometric factors associated with the risk of ACL graft rupture. We hypothesized that the risk factors for noncontact ACL graft rupture would be similar to those previously identified for first-time ACL injury, specifically a decreased femoral notch width and an increased posterior-inferior–directed lateral tibial plateau slope. We also hypothesized that the risk factors for ACL graft injury would differ between males and females.

METHODS

Human Subjects

This study used a subset of data from a larger, institutional review board-approved investigation that identified first-time noncontact ACL injuries in high school and college athletes over a 4-year time interval.3,5,40,44–46,52,56 Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment. Subjects who had sustained a noncontact (MRI and orthopaedic surgeon confirmed) grade III ACL injury during participation in a high school or college sport, and had elected to undergo surgical reconstruction of their ACL, were included in the current study. Cases of ACL graft rupture were defined as those suffering a noncontact, MRI- and orthopaedic surgeon–confirmed ACL graft rupture without injury to the contralateral knee. Eighty-eight first-time ACL-injured subjects who underwent ACLR were prospectively followed for up to 5.5 years after initial surgery. Contact was made with 69 subjects (78.5%); of those, 6 (8.7%) individuals suffered an ACL graft injury. Five additional athletes who participated in the same sports at the same institutions over the same 4-year time interval, but who had previously been excluded from the larger overall study of 88 first-time ACL injuries because their presenting injury was an ACL graft rupture, were added to the current study. This produced a total of 11 subjects (5 female and 6 male) who suffered ACL graft rupture over the study interval. From the 69 subjects with whom contact was established, 44 (25 female and 19 male) who were of similar sex, age, and weight as the ACL graft-ruptured subjects, but had not suffered a second ACL injury to either knee after primary ACLR, were selected as a comparison group (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Study Subjectsa

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft Rupture | ACL Injury and Reconstruction With No ACL Graft Rupture | P | Graft Rupture | ACL Injury and Reconstruction With No ACL Graft Rupture | P | |

| Subjects, n | 6 | 19 | — | 5 | 25 | — |

| Age at first ACL injury, y | 18.0 ± 2.3 | 18.5 ± 2.5 | .34 | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 16.6 ± 1.2 | .11 |

| Age at second ACL graft injury, y | 19.1 ± 2.3 | — | — | 18.1 ± 2.4 | — | — |

| Follow-up interval, mob | 13.4 (7.0–33.9) | 46.3 (32.5–67.3) | — | 26.2 (7.3–59.0) | 38.1 (23.0–59.7) | — |

| Interval between first ACL injury and ACLR, mo | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | — | — | 2.6 (0.6–8.6) | — | — |

| Interval between ACLR and graft rupture, moc | 12.5 (6.0–32.5) | — | — | 23.6 (6.7–58.4) | — | — |

| Weight, kg | 83.3 ± 19.3 | 77.2 ± 19.0 | .26 | 66.5 ± 10.1 | 63.5 ± 8.2 | .28 |

| Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft, n (%) | 4 (66.7) | 15 (78.9) | — | 3 (60) | 15 (60) | — |

| Hamstring tendon autograft, n (%) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | — | 0 (0) | 5 (20) | — |

| Allograft, n (%) | 0(0) | 2 (13.3) | — | 1 (20) | 2(8) | — |

| Graft source unknown, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | — | 1 (20) | 3(12) | — |

| Sport associated with ACL injury, n | ||||||

| Soccer | 2 | 5 | 2 | 11 | ||

| Basketball | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Lacrosse | 2 | 4 | — | 4 | ||

| Rugby | — | 2 | 1 | — | ||

| Baseball/softball | — | 1 | 1 | — | ||

| Track and field | — | — | — | 1 | ||

| Field hockey | — | — | — | 3 | ||

| Football | 1 | 3 | — | — | ||

| Wrestling | — | 1 | — | — | ||

Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as mean ± SD or mean (range). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ACLR, ACL reconstruction.

Follow-up for graft-ruptured subjects was measured as the time interval between first-time ACL injury and graft injury. Follow-up for non-graft-ruptured subjects was measured as time from initial injury to survey contact.

There was no significant difference between time to graft failure for males compared with that for females (P = .27).

Surgical Procedures

Six surgeons (5 fellowship trained in sports medicine) operating at academic, community, and private centers performed the ACLRs in the patients who eventually went on to rupture their ACL graft. The average duration of the surgeons’ practice was 17.7 years (range, 4–26 years). The graft material used was bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft in 7 (4 male) graft ruptures, hamstring autograft in 2 ruptures (both males), BPTB allograft in 1 rupture (female), and not reported for 1 female subject (Table 1). Of the 44 subjects who did not suffer a graft rupture, the ACLRs were performed by 4 of the 6 surgeons who had patients with ACL graft ruptures in our study, as well as 5 additional surgeons. In total, 9 orthopaedic surgeons (6 fellowship trained in sports medicine) with an average of 17.5 years (range, 4–26 years) in practice performed ACLRs in the group that did not go on to suffer ACL graft rupture. Of those subjects not suffering ACL graft rupture, BPTB autograft was used in 30 subjects (15 females), hamstring autograft was used in 6 subjects (5 females), allograft was used in 4 subjects (2 females), and the graft source could not be identified for 4 subjects (3 females).

Surveillance and Follow-up

For the subjects in the ACL graft–ruptured group, the time to follow-up was defined as the time interval from the initial ACL injury to the time of ACL graft rupture (Table 1). Male subjects who suffered an ACL graft rupture had an average time to graft rupture of 13.4 months (range, 7.0–33.9 months), while female ACL graft-ruptured subjects had an average time to graft rupture of 26.2 months (range, 7.3–59.0 months). Of the 11 subjects who sustained an ACL graft rupture, 9 (5 male) returned to participation in high school or college athletics and sustained the graft rupture while participating in the respective sport that produced the initial ACL injury, while the 2 other subjects who suffered ACL graft rupture remained active and sustained their ACL graft injuries during participation in other athletic activities (volleyball and basketball). The follow-up interval of the subjects who did not suffer ACL graft rupture was defined as the time interval from the initial ACL injury to survey contact (Table 1). For males who did not suffer ACL graft rupture, the mean follow-up was 46.3 months (range, 32.5–67.3 months). Of the 19 males who did not suffer graft rupture, 11 returned to competing in their original sport, 6 returned to a different sport or were recreationally active, and 2 did not report their activity level. The mean follow-up interval for the females who did not suffer ACL graft rupture was 38.1 months (range, 23.0–59.7 months). Of those 25 female subjects, 21 returned to competing in their original sport, 2 remained active in a different sport, and 2 did not report their activity level. A summary of demographic data for all study participants is presented in Table 1.

Data Acquisition

Bilateral MRIs were obtained on all subjects with the same Phillips Achieva TX 3-T scanner (Phillips Medical Systems). Knees were scanned with the subject supine and their knees in an extended position inside an 8-channel SENSE knee coil. Sagittal, 3-dimensional (3D), T1-weighted, fast-field echo (voxel size 0.3 mm × 0.3 mm × 1.2 mm) and sagittal, 3D, proton density-weighted (voxel size 0.4 mm × 0.4 mm × 0.7 mm) MRI sequences were used to obtain joint morphologic measurements. These DICOM images were viewed and digitized using Osirix software (Pixmeo; version 3.6.1, open source). Bone and soft tissue landmarks were manually segmented using a Cintiq tablet (Wacom Tech Corp) by 2 pairs of investigators; one pair completed the femoral notch measures, and the other pair made the remaining measurements. Femoral intercondylar notch segmentation was performed in the coronal oblique plane using a proton density–weighted sequence, while all other segmentation was completed in the sagittal plane of the Tl-weighted sequence. Thirty-one distinct measurements were collected for the following structures: tibial spines, tibial subchondral bone, tibial articular cartilage, menisci, and femoral intercondylar notch (see the Appendix, available in the online version of this article and at http://ajsm.sagepub.com/supplemental). The measurement techniques have been previously described and shown to be reproducible (see online Appendix Table Al for measurement descriptions and intraclass coefficient data).3,44,46,56 All data were referenced to a 3D, bone-referenced coordinate system,3 which allowed for measurements to be made in a reliable and reproducible manner, both within and between subjects. All measurements were collected bilaterally, although comparisons between ACL-injured and ACL graft-injured subjects were made using data acquired from the uninjured knee, as prior work has shown ACL injury can produce an immediate change to certain aspects of knee geometry. For 6 of the subjects who suffered ACL graft rupture, the MRI data were acquired after the first ACL injury but before surgery. The remaining 5 subjects who suffered ACL graft ruptures were identified soon after injury to their graft, and MRI data were not available before the graft rupture. Consequently, MRI data were obtained after the graft rupture.

Statistical Methods

Cox regression analyses were conducted, modeling time to event, with each factor as an independent variable to assess its univariate association with the risk of ACL graft rupture. Separate analyses were done for males and females. Significance level alpha was set at .05 a priori for all analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Significant findings, including hazard ratio (HR), 95% CI, and P values, are provided in Table 2. An analysis of all measurements, including combined male and female data, means, and SDs, may be found in the supplemental text (see Appendix Tables A2 and A3, available online).

TABLE 2.

Results From the Univariate Cox Regression Analysis

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Hazard Ratio for ACL Graft Rupture (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio for First ACL Injury | Hazard Ratio for ACL Graft Rupture (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio for First ACL Injury |

| Tibial spine | ||||||

| Med_volume, 100 mm3 | 1.45 (1.17–1.95) | .01 | 0.67 | 0.45 (0.23–0.89) | .02 | NS |

| Med_height, mm | 1.17 (0.61–2.24) | .64 | NS | 0.46 (0.24–0.90) | .02 | NS |

| Med_length, mm | 1.34 (1.11–1.60) | .0023 | NS | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | .46 | NS |

| Lat_volume, 100 mm3 | 1.24 (0.88–1.58) | .21 | NS | 1.27 (0.83–1.96) | .27 | NS |

| Lat_length, mm | 1.18 (1.07–1.28) | .0005 | NS | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) | .71 | NS |

| Lat_width, mm | 2.19 (1.42–3.37) | .0004 | NS | 1.44 (0.83–2.50) | .20 | NS |

| Tibial articular cartilage and meniscus | ||||||

| Lat_MCS, deg | 1.50 (1.04–2.16) | .029 | NS | 0.99 (0.75–1.31) | .95 | 1.30 |

| Lat_PCS, deg | 1.39 (1.10–1.76) | .006 | NS | 0.95 (0.86–1.04) | .24 | 1.15 |

| Med_MCH, mm | 1.00 (0.61–1.65) | .99 | NS | 0.09 (0.02–0.37) | .001 | 0.63 |

| Tibial plateau subchondral bone | ||||||

| LTS, mm | 1.03 (0.82–1.30) | .77 | NS | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | .01 | 1.22 |

| Femoral intercondylar notch | ||||||

| NW_AA, mm | 1.07 (0.73–1.56) | .73 | 0.70 | 0.72 (0.54–0.94) | .02 | 0.69 |

Data are presented as hazard ratios with 95% CIs. The bolded text represents comparisons that were statistically significant( P < .05). For the significant results, previously reported univariate odds ratios are presented for first-time anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury risk.3,44,46,56 Lat, measurement in the lateral tibial compartment; LTS, lateral tibial slope; MCH, meniscus cartilage height; MCS, posterior-directed slopes in the middle segment of the tibial articular cartilage; Med, measurement in the medial tibial compartment; NS, the measurement was not significant as a first-time ACL injury risk factor; NW_AA, femoral notch width at the anterior attachment of the ACL; PCS, posterior-directed slopes in the posterior segment of the tibial articular cartilage.

Male Subjects

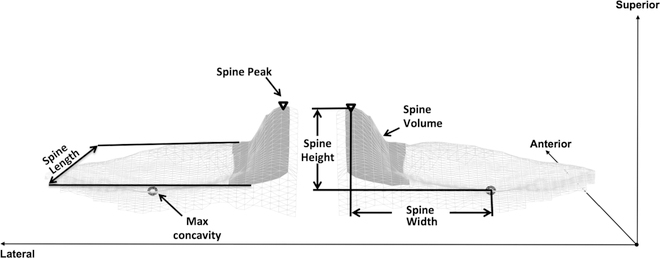

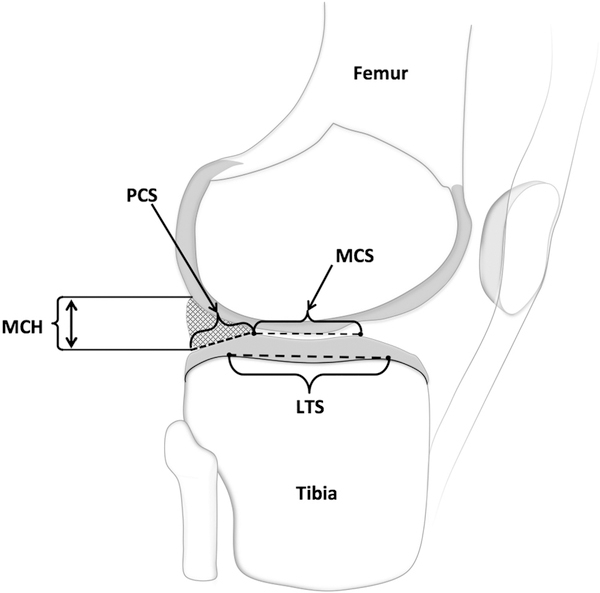

Within male subjects, every 1-mm increase in the mediolateral distance between the peak of the lateral tibial spine and the point of maximum concavity in the lateral compartment of the tibia (Figure 1) was associated with a 119% increase in the risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 2.19; P = .0004). In contrast to the female results, every 100 mm3 increase in the medial tibial spine volume (Figure 1) was associated with a 45% increased risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 1.45; P = .01). Every 1-mm increase in the maximum anterior-posterior length of the medial tibial spine (Figure 1) was associated with a 34% increase in the risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 1.34; P = .0023), and a 1-mm increase in the same measurement of tibial spine length in the lateral compartment (Figure 1) was also associated with an 18% increased risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 1.18; P = .0005). In the lateral tibial compartment, every 1° increase in middle cartilage slope (Figure 2) was associated with a 50% increase in risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 1.50; P = .029). Similarly, a 1° increase in posterior cartilage slope in the lateral compartment (Figure 2) was associated with a 39% increased risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 1.39; P = .006).

Figure 1.

Segmented data of subchondral tibial bone (light gray) and tibial spine (dark gray) of the medial and lateral tibial compartments. Tibial spine volume is the area shaded in dark gray. Tibial spine width, length, and height are depicted. The maximum (Max) concavity was determined as the point on the tibia that corresponded to the most distal point of the femur when the knee was in extension. The measurements were acquired in the same manner for the lateral and medial compartments of the tibia.

Figure 2.

Sagittal view of the lateral tibial compartment depicting segmented data for meniscus (cross-hatched triangle), tibial articular cartilage (light gray surface), and underlying subchondral bone. Middle cartilage slope (MCS) and posterior cartilage slope (PCS), meniscus cartilage height (MCH), and lateral tibial slope (LTS) measurements are depicted. The same measures were made in the medial compartment of the tibia.

Female Subjects

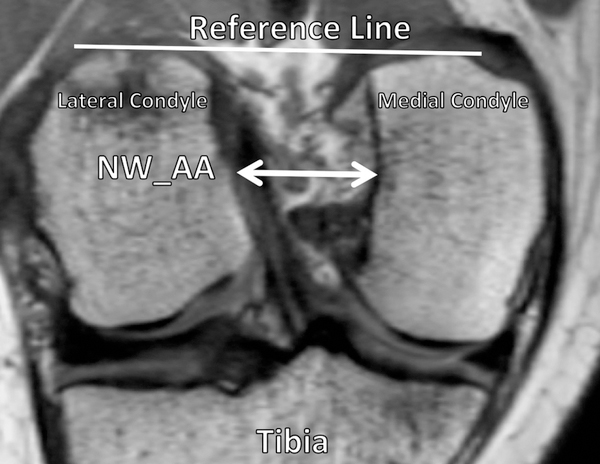

Within female subjects, every 1-mm increase in the distance from the cartilage surface to the maximum height of the posterior horn of the meniscus in the medial compartment (Figure 2) was associated with a 91% decrease in risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 0.09; P = .001). Likewise, an increase in medial tibial spine volume of 100 mm3 (Figure 1) was associated with a 55% decrease in risk of ACL graft injury (HR = 0.45; P = .02). Similarly, a 1-mm increase in the superior-inferior height of the medial tibial spine (Figure 1) was associated with a 54% decrease in risk of ACL graft injury (HR = 0.46; P = .02). For measurements of tibial subchondral bone, a significant association with risk of ACL graft injury was found only among the female athletes. Every 1° increase in the posterior-inferior–directed slope of the lateral tibial compartment (Figure 2) was associated with a 28% decrease in risk of suffering an ACL graft injury (HR = 0.72; P = .01). A significant relationship between characteristics of the femoral intercondylar notch and risk of ACL graft injury was revealed. Every 1-mm increase in notch width at the anterior attachment of the ACL (Figure 3) was associated with a 28% decrease in the risk of ACL graft rupture (HR = 0.72; P = .02).

Figure 3.

Oblique-coronal view of the femoral intercondylar notch. The notch width (NW_AA) was measured by identifying the anterior attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) on the lateral condyle and drawing a line to the wall of the medial condyle. The measurement was made parallel to the reference line indicated, which connected the 2 most posterior aspects of each femoral condyle.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study support the hypothesis that the anatomic factors associated with risk of ACL graft rupture are different between males and females. However, only 2 of the anatomic risk factors associated with risk of ACL graft injury were also associated with risk of first-time ACL injury for the female athletes: a decreased femoral intercondylar notch width and a decreased height of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. There were no risk factors in common between ACL graft injury and first-time ACL injury for the male athletes.

For the females, the factors that were associated with increased risk of injury to both the ACL graft and the ACL included a decreased width of the femoral notch and a decreased height of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: The former may be associated with impingement of the ACL graft against the femoral notch (as has been shown for the native ACL),2,16 while the latter may be associated with the observation that a smaller posterior horn of the meniscus would be less effective at resisting anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur as described by Hudek et al.22 In addition to these common risk factors for injury to the ACL and ACL graft, females with decreases in the height and volume of the medial tibial spine had an increased risk of ACL graft injury. A decrease in the 3D contour and distribution of the tibial spine may be associated with a decrease in resistance to the intersegmental joint loads produced by articular contact between the tibia and femur during participation in sport and activity. This may influence the magnitude of internal-external rotation and medial translation between these articular surfaces, which in turn may increase the magnitude of strain that the ACL graft is exposed to and must resist, particularly during maneuvers that create substantial loads such as planting, cutting, and pivoting. It is also important for us to point out that several studies have found that an increase in the posterior-inferior–directed slope of the lateral tibial plateau is associated with increased risk of suffering a first-time ACL injury,3,41,43,50 as well as an ACL graft injury.10 Consequently, we hypothesized that the same relationship would exist between tibial plateau slope and risk of ACL graft injury. However, we found the opposite in the female athletes: A decreased slope was associated with increased risk of ACL graft injury. This contradictory finding may be explained by the observation that an anterior-directed slope of the tibial plateau has been associated with increased genu recurvatum,9 a risk factor for ACL injury,6 and has been shown to increase ACL strain values.29 In addition, Terauchi et al48 found that, in females, either hyperextension or posterior-directed tibial plateau slope was associated with ACL injury, but the 2 variables were inversely related. Finally, an increase in the vertical orientation of an ACL graft relative to the tibial plateau is associated with increased risk of injury to the graft,17 and the strain produced by movement of the knee into hyperextension would likely be greater for a vertically oriented ACL graft compared with a graft that is oriented more horizontally; however, we are unaware of a study analyzing this relationship. We are aware of the work of Thompson et al,49 who found an increased rate of ACL graft rupture in subjects who had a graft oriented more vertically relative to subjects who did not go on to suffer a graft rupture. This observation leads us to theorize that the decreased posterior-inferior–directed slope in the female athletes who suffered ACL graft injury could be associated with increased knee hyperextension, thereby increasing strain across the ACL graft, especially if the graft is oriented vertically.

The males were found to have a distinct set of risk factors based on the geometry of the articular surfaces and spines of the tibial plateau. Increased posterior-inferior–directed slope of the middle and posterior regions of lateral tibial articular cartilage was associated with increased risk of ACL graft injury, and these findings were consistent with the literature concerning first-time ACL injury in females.46 It is likely that the mechanism associated with increased posterior-inferior–directed slope of the lateral tibial cartilage and risk of graft injury is the same as that proposed for first-time ACL injury26,31: Increased lateral tibial cartilage slope is associated with increased magnitude of the anterior-directed intersegmental load across the tibia relative to the femur, which increases the strain values on the ACL graft during participation in sport. With regard to the tibial spines, increases in the volume and anteroposterior length of the medial tibial spine were associated with increased risk of graft rupture in the male athletes. We expected the opposite relationship, as described above for the females, and consequently it is difficult to provide an explanation for this finding. Finally, we found that an increased mediolateral width of the lateral tibial spine was associated with an increased risk of ACL graft rupture. The mechanism by which this relationship works may be explained by the fact that an increased mediolateral width produces a greater moment arm, which may produce greater magnitudes of intersegmental internal-external torques across the tibiofemoral joint during activities associated with plant, cut, and pivot sports.

Several studies have reported that risk factors for a first-time ACL injury differ between males and females.3,44–46,56 The current study produced a similar finding. Differences in ACL graft rupture rates between males and females25,28 may be explained by geometric differences in knee anatomy between sexes. Other work has found that the position of the knee at the time of noncontact, first-time ACL injury differs for males and females.24 This may also hold true for ACL graft injury and, thus, supports some of the differences found between males and females regarding geometric risk factors. Future studies designed to study the risk factors associated with repeated ACL injury should consider conducting sex-specific analyses.

Our study has several strengths, including the fact that no previous study, to our knowledge, has prospectively identified a comprehensive set of geometric risk factors for ACL graft rupture using MRI data. The use of a 3D coordinate system located within bone with a reliable approach resolves positional tibiofemoral variability at the time of MRI acquisition, thus standardizing the measurements. This approach is supported by the work of Feucht et al,14 which indicated the need for a comprehensive 3D analysis of the tibia to assess risk of ACL injury. In addition, the entry criteria used for this investigation were stringent, as we excluded all partial ACL graft tears and necessitated a noncontact mechanism of index ACL injury and repeated ACL graft injuries coupled with continued involvement in athletics. We controlled for the risk of sustaining a first-time injury because all subjects sustained at least 1 ACL injury. The athletes who did not experience an ACL graft rupture were similar in age and weight in comparison with those who suffered graft rupture and participated in many of the same sports that produced the injuries, making our study population very homogeneous.

Some of our findings may be difficult to explain using the current understanding of ACL biomechanics because knee mechanics change after ACL injury and reconstruction. Increased external tibial rotation has been observed when performing jumping, landing, and pivoting after ACLR,37 as well as increased anterior tibial translation relative to the femur.4,47 Therefore, the geometry of the knee may have a different effect on its biomechanical behavior during high-energy tasks in a joint with a reconstructed ACL compared with a joint with a normal ACL. Further study is required to identify how these changes may be related to, and be affected by, joint geometry.

The variability in the surgical procedure and surgeon experience was associated with strengths and limitations of this study. Only 1 surgeon had less than 14 years of experience, only 1 surgeon without sports medicine fellowship training performed an ACLR that resulted in graft rupture, and a variety of graft materials were used. While this makes our work more generalizable to all athletes at risk for suffering ACL graft injury, the sample size was not large enough to allow us to conduct subgroup analyses based on graft material, extent of surgeon training, and the years of experience associated with ACLR. The small sample size limited our statistical power to identify risk factors; however, the motivation for this work was hypothesis generating. A design limitation was the use of the contralateral knee as a surrogate for the injured knee; this approach was chosen because ACL injury changes some aspects of knee geometry.3,36,46 The effect of the injury and ACLR on the geometry of the femoral notch and tibial spines may have been significant and may have important implications for the risk of ACL graft injury. In addition, it is possible that altered gait mechanics of the injured knee may have affected the underlying geometry and biomechanics of the contralateral healthy knee,21 and vice versa. This issue is of concern because some MRIs were acquired before graft injury and some afterwards. However, we found no evidence of differences in either the means or the variability of measurements made in the contralateral knee of subjects with graft injuries based on when the MRI was obtained. We also repeated the analyses with an indicator variable to control for the timing of the MRI and obtained similar results to the unadjusted analyses, further indicating that any changes to the geometry of the contralateral knee between initial injury and graft rupture did not greatly influence the results. Another limitation was our inability to account for the possible role of surgical technique, specifically tunnel malposition,17 as a cause of graft failure rather than graft rupture produced by a mechanism similar to that of a first-time ACL injury. Unfortunately, neither bone tunnel position data nor knee laxity data after surgery were available to us for this study. However, work by Matava et al30 demonstrated that 10 orthopaedic surgeons reviewing 20 cases of revision ACLR were unable to agree whether the cause of graft failure was due to malpositioning of the graft or by other mechanisms. Therefore, even if we had intraoperative and/or radiographic data on bone tunnel location, it is unclear if we would have the ability to establish the cause of graft failure. ACL graft rupture is a multifactorial problem, and the relative contributions of the many variables (intrinsic and extrinsic factors and surgical and rehabilitative strategies) are not known. Because graft failure due to graft malposition or poor tissue integration may occur by a different mechanism, we excluded any ACL injury occurring within 6 months after ACLR and required a noncontact mechanism of injury for both the ACL and ACL graft injury. Finally, we were unable to control for differences in rehabilitation protocols, which may influence risk of graft rupture. Our exclusion of graft injuries occurring less than 6 months after ACLR may help to account for this, as does the fact that differences in accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation have not been shown to alter anterior-posterior knee laxity during healing.4 However, future studies should attempt to standardize and monitor return to sport protocols to account for this potential confounder.

An important goal of identifying risk factors for ACL graft rupture is to decrease its incidence, and recent work has advocated for this.33 Armed with this knowledge, clinicians may be able to better counsel those considering ACLR by giving an individualized risk assessment. Given that MRI is routinely acquired after first-time ACL injury, the ability to screen for these risk factors is much more practical compared with screening for first-time ACL injury. Second, risk factor identification may help shape an individualized rehabilitation plan. Third, identification of risk factors could drive surgical modification to compensate for these risk-associated geometries. For example, Sonnery-Cottet et al42 have used proximal tibial anterior closing-wedge angle osteotomies in 5 subjects (4 males) undergoing a third ipsilateral ACLR to decrease posterior-inferior-directed slope of the tibial plateau. There was no recurrence of ACL injury after follow-up of 23 to 45 months. Similar results were reported by Dejour et al11 in a group of 6 males and 3 females. Given the significance of the posterior-inferior-directed cartilage slope found in male athletes in our study, we believe this serves as an example of how risk factor identification can be used to help reduce reinjury rates through counseling and surgical intervention.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first to develop a model inclusive of multiple geometric factors associated with the risk of ACL graft rupture. Medial tibial spine volume, the geometry of the medial and lateral tibial spines, the slope of the tibial subchondral bone and cartilage in the lateral compartment, the height of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, and the geometry of the intercondylar notch all produced significant results in sex-specific analyses. Several results reflected those found regarding first-time ACL injury risk factors, while others indicated that there are differences between the risk factors for ACL graft rupture and those for first-time ACL injury. We demonstrated that geometric risk factors for ACL graft injury are different for males and females. The current investigation provides a starting point, and future work is warranted on a larger scale to help describe the full context of ACL graft rupture risk factors with the goal of reducing the incidence of reinjury through a multidisciplinary approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Support was received from the following grants: National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases 5R01-AR050421 and DOE SC 0001753.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Ageberg E, Forssblad M, Herbertsson P, Roos EM. Sex differences in patient-reported outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the Swedish knee ligament register. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1334–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson AF, Lipscomb AB, Liudahl KJ, Addlestone RB. Analysis of the intercondylar notch by computed tomography. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beynnon BD, Hall JS, Sturnick DR, et al. Increased slope of the lateral tibial plateau subchondral bone is associated with greater risk of noncontact ACL injury in females but not in males: a prospective cohort study with a nested, matched case-control analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Naud S, et al. Accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind investigation evaluating knee joint laxity using Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(12):2536–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beynnon BD, Vacek PM, Newell MK, et al. The effects of level of competition, sport, and sex on the incidence of first-time noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8): 1806–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA Jr, Garrett WE Jr. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000;23(6):573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourke HE, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Patterson V, Pinczewski LA. Survival of the anterior cruciate ligament graft and the contralateral ACL at a minimum of 15 years. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9): 1985–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JL, Allen CR, Stephens TE, et al. Differences in mechanisms of failure, intraoperative findings, and surgical characteristics between single- and multiple-revision ACL reconstructions: a MARS cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi IH, Chung CY, Cho TJ, Park SS. Correction of genu recurvatum by the Ilizarov method. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(5):769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen JJ, Krych AJ, Engasser WM, Vanhees MK, Collins MS, Dahm DL. Lateral tibial posterior slope is increased in patients with early graft failure after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2510–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dejour D, Saffarini M, Demey G, Baverel L. Tibial slope correction combined with second revision ACL produces good knee stability and prevents graft rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrose. 2015;23(10):2846–2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everhart JS, Flanigan DC, Simon RA, Chaudhari AM. Association of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury with presence and thickness of a bony ridge on the anteromedial aspect of the femoral intercondylar notch. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1667–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faltstrom A, Hagglund M, Magnusson H, Forssblad M, Kvist J. Predictors for additional anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the Swedish national ACL register. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrose. 2016;24(3):885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feucht MJ, Mauro CS, Brucker PU, Imhoff AB, Hinterwimmer S. The role of the tibial slope in sustaining and treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrose. 2013;21(1): 134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Roemer FW, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung DT, Hendrix RW, Koh JL, Zhang LQ. ACL impingement prediction based on MRI scans of individual knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Getelman MH, Friedman MJ. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J Am Aead Orthop Surg. 1999;7(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt EA, et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006; 34(9):1512–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemi J, Chandrashekar N, Mansouri H, et al. Shallow medial tibial plateau and steep medial and lateral tibial slopes: new risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2010; 38(1):54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hettrich CM, Dunn WR, Reinke EK, Group M, Spindler KP. The rate of subsequent surgery and predictors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: two- and 6-year follow-up results from a multicenter cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1534–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofbauer M, Thorhauer ED, Abebe E, Bey M, Tashman S. Altered tibiofemoral kinematics in the affected knee and compensatory changes in the contralateral knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2715–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudek R, Fuchs B, Regenfelder F, Koch PP. Is noncontact ACL injury associated with the posterior tibial and meniscal slope? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(8):2377–2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Reinke EK, Huston LJ, MOON Consortium, Spindler KP. Risk factors and predictors of subsequent ACL injury in either knee after ACL reconstruction: prospective analysis of 2488 primary ACL reconstructions from the MOON cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krosshaug T, Nakamae A, Boden BP, et al. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: video analysis of 39 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(3):359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leys T, Salmon L, Waller A, Linklater J, Pinczewski L. Clinical results and risk factors for reinjury 15 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipps DB, Oh YK, Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM. Morphologic characteristics help explain the gender difference in peak anterior cruciate ligament strain during a simulated pivot landing. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1756–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maletis GB, Inacio MC, Funahashi TT. Risk factors associated with revision and contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in the Kaiser Permanente ACLR registry. Am J Sports Med. 2015; 43(3):641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markolf KL, Gorek JF, Kabo JM, Shapiro MS. Direct measurement of resultant forces in the anterior cruciate ligament: an in vitro study performed with a new experimental technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(4):557–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matava MJ, Arciero RA, Baumgarten KM, et al. Multirater agreement of the causes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction failure: a radiographic and video analysis of the Mars cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(2):310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLean SG, Oh YK, Palmer ML, et al. The relationship between anterior tibial acceleration, tibial slope, and ACL strain during a simulated jump landing task. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(14):1310–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oiestad BE, Holm I, Aune AK, et al. Knee function and prevalence of knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study with 10 to 15 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2201–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paterno MV. Incidence and predictors of second anterior cruciate ligament injury after primary reconstruction and return to sport. J Athl Train. 2015;50(10):1097–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of second ACL injuries 2 years after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1567–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter HG, Jain SK, Ma Y, Black BR, Fung S, Lyman S. Cartilage injury after acute, isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear: immediate and longitudinal effect with clinical/MRI follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raynauld JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Berthiaume MJ, et al. Correlation between bone lesion changes and cartilage volume loss in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee as assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging over a 24-month period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; 67(5):683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ristanis S, Stergiou N, Patras K, Vasiliadis HS, Giakas G, Georgoulis AD. Excessive tibial rotation during high-demand activities is not restored by anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1323–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmon L, Russell V, Musgrove T, Pinczewski L, Refshauge K. Incidence and risk factors for graft rupture and contralateral rupture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):948–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2): 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith HC, Johnson RJ, Shultz SJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) as a screening tool for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. Am J Sports Med. 2012; 40(3):521–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnery-Cottet B, Archbold P, Cucurulo T, et al. The influence of the tibial slope and the size of the intercondylar notch on rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11): 1475–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonnery-Cottet B, Mogos S, Thaunat M, et al. Proximal tibial anterior closing wedge osteotomy in repeat revision of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1873–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stijak L, Herzog RF, Schai P. Is there an influence of the tibial slope of the lateral condyle on the ACL lesion? A case-control study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(2):112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturnick DR, Argentieri EC, Vacek PM, et al. A decreased volume of the medial tibial spine is associated with an increased risk of suffering an anterior cruciate ligament injury for males but not females. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(11):1451–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturnick DR, Vacek PM, DeSarno MJ, et al. Combined anatomic factors predicting risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury for males and females. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sturnick DR, Van Gorder R, Vacek PM, et al. Tibial articular cartilage and meniscus geometries combine to influence female risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(11):1487–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tagesson S, Oberg B, Kvist J. Static and dynamic tibial translation before, 5 weeks after, and 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015; 23(12):3691–3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terauchi M, Hatayama K, Yanagisawa S, Saito K, Takagishi K. Sagittal alignment of the knee and its relationship to noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(5):1090–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson S, Salmon L, Waller A, Linklater J, Roe J, Pinczewski L. Twenty-year outcomes of a longitudinal prospective evaluation of isolated endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2164–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Todd MS, Lalliss S, Garcia E, DeBerardino TM, Cameron KL. The relationship between posterior tibial slope and anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tourville TW, Johnson RJ, Slauterbeck JR, Naud S, Beynnon BD. Relationship between markers of type II collagen metabolism and tibiofemoral joint space width changes after ACL injury and reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):779–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vacek PM, Slauterbeck JR, Tourville TW, et al. Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for first-time noncontact ACL injury in high school and college athletes: a prospective cohort study with a nested, matched case-control analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6): 1492–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Porat A, Roos EM, Roos H. High prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study of radiographic and patient relevant outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(3):269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Webb JM, Salmon LJ, Leclerc E, Pinczewski LA, Roe JP. Posterior tibial slope and further anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed patient. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2800–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014; 42(3):641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitney DC, Sturnick DR, Vacek PM, et al. Relationship between the risk of suffering a first-time noncontact ACL injury and geometry of the femoral notch and ACL: a prospective cohort study with a nested case-control analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolf MR, Murawski CD, van Diek FM, van Eck CF, Huang Y, Fu FH. Intercondylar notch dimensions and graft failure after single- and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(3):680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.