Key Points

Question

Does an association exist between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery?

Findings

In this survey study of 252 participants, increased investment in the use of social media platforms was associated with increased consideration of cosmetic surgery. Participants who reported using specific applications, such as YouTube, Tinder, and Snapchat photograph filters, had an increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery; use of other applications, including WhatsApp and Photoshop, was associated with significantly lower self-esteem scores.

Meaning

These findings suggest that perceptions of cosmetic surgery may vary based on social media and photograph editing application use.

Abstract

Importance

Social media platforms and photograph (photo) editing applications are increasingly popular sources of inspiration for individuals interested in cosmetic surgery. However, the specific associations between social media and photo editing application use and perceptions of cosmetic surgery remain unknown.

Objective

To assess whether self-esteem and the use of social media and photo editing applications are associated with cosmetic surgery attitudes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A population-based survey study was conducted from July 1 to September 19, 2018. The web-based survey was administered through online platforms to 252 participants.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Each participant’s self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (scores range from 0-30; higher scores indicate higher self-esteem) and the Contingencies of Self-worth Scale (scores range from 1-7; higher scores indicate higher self-worth). Cosmetic surgery attitude was measured using the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (scores range from 1-7; higher scores indicate higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery). Unpaired, 2-tailed t tests were used to assess the significance of self-esteem and cosmetic surgery attitude score differences among users of various social media and photo editing applications. Structural equation modeling was used to assess the association between social media investment and cosmetic surgery attitudes.

Results

Of the 252 participants, 184 (73.0%) were women, 134 (53.2%) reported themselves to be white, and the mean age was 24.7 (range, 18-55) years. Scores on the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale from users and nonusers across applications were compared, with lower self-esteem scores noted in participants who reported using YouTube (difference in scores, −1.56; 95% CI, −3.01 to −0.10), WhatsApp (difference in scores, −1.47; 95% CI, −2.78 to −0.17), VSCO (difference in scores, −3.20; 95% CI, −4.98 to −1.42), and Photoshop (difference in scores, −2.92; 95% CI, −5.65 to −0.19). Comparison of self-esteem scores for participants who reported using other social media and photo editing applications yielded no significant differences. Social media investment had a positive association with consideration of cosmetic surgery (R, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.04-0.66). A higher overall score on the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale was noted in users of Tinder (difference in means, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.34-1.23), Snapchat (difference in means, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.71), and/or Snapchat photo filters (difference in means, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.16-0.72). Increased consideration of cosmetic surgery but not overall acceptance of surgery was noted in users of VSCO (difference in means, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.32-1.35) and Instagram photo filters (difference in means, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.01-0.76) compared with nonusers.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that the use of certain social media and photo editing applications may be associated with increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery. These findings can help guide future patient-physician discussions regarding cosmetic surgery perceptions, which vary by social media or photo editing application use.

This survey study examines whether self-esteem and the use of social media and photo editing applications are associated with cosmetic surgery attitudes among participants responding to a web-based survey.

Introduction

Social media provide endless opportunities to present our best—often digitally enhanced and contrived—self to the public. Applications such as Snapchat and Instagram have built-in filters and photograph (photo) editing features that allow users to soften wrinkles or alter the size of their eyes before sharing self-images (“selfies”) throughout social media. The ubiquity of social media and photo editing applications significantly affects the field of cosmetic surgery. The 2017 annual American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery survey found that 55% of surgeons reported seeing patients who requested surgery to improve their appearance in selfies. Although social media appear to be behind increased rates of cosmetic surgery, little research has been conducted to explore whether the use of social media and photo editing applications is associated with perceptions of cosmetic surgery.

Several studies have examined the psychosocial impact of selfies. McLean et al found that teenaged girls who regularly posted selfies on social media had higher body dissatisfaction and significant overvaluation of body shape. Frequent selfie viewing behavior was also correlated with lower self-esteem and decreased life satisfaction, which may lead to body dysmorphic disorder, a psychiatric condition characterized by excessive preoccupation with nonexistent or minimal defects in one’s appearance. These findings highlight the adverse effects of social media on self-esteem and emphasize the need to better assess how social media use influences attitudes toward cosmetic surgery.

The increasing popularity of selfie taking and photo editing has led cosmetic surgeons to coin a new term—Snapchat dysmorphia—to refer to the psychological phenomenon of patients bringing filtered selfies to their surgeons to illustrate the desired surgical changes they are looking to achieve. Although filtered selfies provide surgeons with visually defined patient expectations, much debate exists over whether photo editing contributes to body dysmorphic disorder or influences a patient’s perceptions of cosmetic surgery.

Relatively little quantitative research exists linking the use of social media and photo editing applications with the general public’s cosmetic surgery attitudes. To address the research gap, this study aimed to assess whether the use of social media and photo editing applications is associated with changes in cosmetic surgery attitudes. The hypothesis was that participants who had higher investment in using social media and photo editing applications would have increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery compared with participants who had lower investment.

Methods

Participants

Between July 1 and September 19, 2018, individuals were recruited to complete a web-based survey through public access website distributions (Reddit, Facebook, and Instagram) and university email list invitations. Individuals were not eligible to participate if they were younger than 18 years or did not denote English as their primary language. In all, 252 individuals successfully completed the survey. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University.

Survey Instrument

The survey was built using Qualtrics survey software (SAP SE). The survey’s first page comprised a description of the study, exclusion criteria, and notification to respondents that continuing with the survey would serve as informed consent for study participation. To encourage participation, respondents were given the opportunity to enter a gift card raffle when they completed the survey.

After providing demographic information, participants were asked to select the social media platforms (eg, Facebook and YouTube) they currently used from a list of platforms, which was generated from a 2018 Pew Research Center study that identified popular social media applications in the United States. If desired, participants could also report an unlisted social media application. Participants then self-reported the number of hours per day they typically spent on social media platforms.

To assess photo editing use, participants were asked to select the photo editing tools (eg, Snapchat filters and Photoshop) they currently used from a list of applications and/or to report an unlisted application. The list of photo editing applications was created from the most popular free and paid photo and video applications chart in the Apple App Store. Participants were also asked, using visual analog sliding scales, the number of self-images they posted per week (range, 0-200 images), the percentage of their posted photos that were digitally enhanced (range, 0%-100%), and the amount of time they spent digitally enhancing a photo before posting (range, 0-100 minutes). In addition, participants were asked to report whether they had ever untagged or removed a photograph of themselves from social media if the photograph “was not digitally enhanced or edited to their liking.”

Three previously validated questionnaires were used to measure respondents’ self-esteem and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (score range, 0-30; higher scores indicate higher self-esteem) and the 10-item, abbreviated version of the Contingencies of Self-worth (CSW) Scale (score range, 1-7; higher scores indicate higher self-worth). Only the appearance and approval domain questions were used from the CSW, as those domains were most closely related to physical appearance as a basis for self-worth. The 15-item Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS) (score range, 1-7; higher scores indicate higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery) was used to assess attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. Cosmetic surgery attitudes were based on 3 domains: (1) consider, or the degree to which an individual would consider having cosmetic surgery; (2) social, or the acceptance of cosmetic surgery based on social motivation; and (3) intrapersonal, or the acceptance of cosmetic surgery based on intrapersonal motivation. Scores from each ACSS domain were averaged to compute a mean score for overall acceptance of cosmetic surgery.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software, version 15 (StataCorp LLC). Unpaired, 2-tailed t tests were used to compare Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale scores and ACSS scores among users and nonusers. Difference in scores was calculated by subtracting the scores of nonusers from the scores of users. Multilinear regression analysis was performed to assess the association between social media and photo editing application use, self-esteem, and participant ACSS scores. Preliminary analysis revealed associations between social media and photo editing use, the appearance domain of the CSW, and the consider domain of the ACSS.

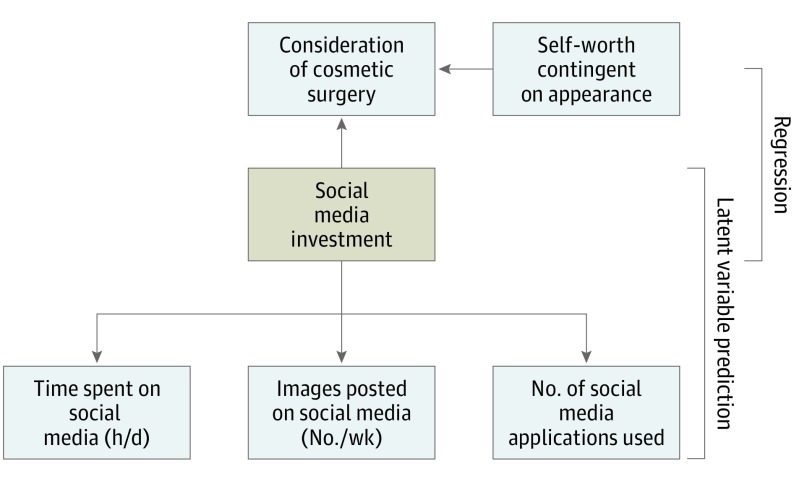

Further analysis of these associations was performed using structural equation modeling, which allowed us to account for latent and observed variables that may have been associated with consideration of cosmetic surgery beyond the domains measured. In the Figure, the variable in the tan rectangle (social media investment) represents an unmeasurable latent variable inferred from collected data. Variables in blue rectangles represent observed variables from survey results. The social media investment latent variable comprised time spent on social media (hours per day), number of images posted on social media per week, and number of social media applications currently used. The photo editing investment variable comprised collective responses regarding the number of photo editors used, minutes spent editing a picture before posting, and the percentage of all posted images that were enhanced. However, given sample size criteria, photo editing investment variables were not analyzed in the study’s structural equation model. Both the latent variable (social media investment) and the observed variable (self-worth contingent on appearance) were regressed with the consider domain of ACSS scores. Significance testing was 2-sided, with a significance threshold of P < .05.

Figure. Conceptual Path Diagram Illustrating Associations Between Variables in the Structural Equation Model.

Results

A total of 252 participants successfully completed the web-based survey between July 1 and September 19, 2018; Table 1 lists their demographic characteristics. Of the respondents, most were women (184 [73.0%]) and white (134 [53.2%]), with a mean age of 24.7 (range, 18-55) years and a 4-year college degree (178 [70.6%]) and had not previously undergone any cosmetic surgeries to enhance their appearance (242 [96.0%]). Participants reported using a mean of 7 social media (range, 1-14) and 2 photo editing (range, 1-6) applications. All survey participants reported using at least 1 social media platform.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) (N = 252) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 24.7 (18-55) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 67 (26.6) |

| Female | 184 (73.0) |

| Prefer not to specify | 1 (0.4) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 82 (32.5) |

| Black | 8 (3.2) |

| White | 134 (53.2) |

| Hispanic | 14 (5.5) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 |

| Other/prefer not to specify | 14 (5.5) |

| Educational level | |

| <High school | 0 |

| High school diploma or general equivalence diploma | 5 (2.0) |

| Some college | 24 (9.5) |

| 2-y College degree | 1 (0.4) |

| 4-y College degree | 178 (70.6) |

| Master degree | 25 (9.9) |

| Doctoral degree | 19 (7.5) |

| Annual household income, $a | |

| <25 | 48 (19.0) |

| 25 to <50 | 31 (12.3) |

| 50 to <75 | 35 (13.9) |

| 75 to <100 | 27 (10.7) |

| 100 to <150 | 31 (12.3) |

| 150 to <200 | 12 (4.8) |

| ≥200 | 68 (27.0) |

| Cosmetic procedures | |

| Underwent procedure to enhance facial appearance | 10 (4.0) |

| Friends or relatives underwent procedure to enhance facial appearance | 68 (27.0) |

Values are expressed in thousands.

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

On the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, participants who reported using YouTube (difference in scores, −1.56; 95% CI, −3.01 to −0.10) and WhatsApp (difference in scores, −1.47; 95% CI, −2.78 to −0.17) social media platforms had lower self-esteem scores than nonusers. Users of VSCO (difference in scores, −3.20; 95% CI, −4.98 to −1.42), and Photoshop (difference in scores, -2.92; 95% CI, -5.65 to −0.19) photo editing platforms also had significantly lower self-esteem scores than nonusers. Comparison of self-esteem scores for users of all other social media and photo editing applications yielded no significant differences.

Contingencies of Self-worth Scale

Multivariate regression analysis indicated that participants with self-worth more contingent on appearance had increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery. On the CSW, each 1-U change in appearance-based self-worth was associated with a 0.53-point increase in consideration of surgery (95% CI, 0.34-0.71), a 0.21-point increase in intrapersonal acceptance of surgery (95% CI, 0.06-0.35), and a 0.35-point increase in social acceptance of surgery (95% CI, 0.19-0.51).

Social Media

Multivariate regression analysis showed that participants who used more social media applications were more likely to consider surgery (R, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.01-0.18). Further analysis using planned-hypothesis, unpaired, 2-tailed t tests assessed differences in ACSS scores among users of different social media and photo editing applications. Mean overall ACSS scores were compared for each application, and results of significance are summarized in Table 2. A higher overall score on the ACSS was noted in users of Tinder (difference in means, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.34-1.23), Snapchat (difference in means, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.71), and/or Snapchat photo filters (difference in means, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.16-0.72). Comparison of all other social media applications yielded no significant difference in overall ACSS score.

Table 2. Overall Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS) Mean Scores by Social Media and Photo Editing Application.

| Application | ACSS Mean Score | P Valuea | Difference in ACSS Mean Scores (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did Not Use Application | Used Application | |||

| Social media | ||||

| YouTube | 3.19 | 3.55 | .02 | 0.36 (0.05 to 0.68) |

| Tinder | 3.37 | 4.16 | <.001 | 0.79 (0.34 to 1.23) |

| 3.65 | 3.20 | .002 | −0.44 (−0.72 to −0.16) | |

| Snapchat | 3.17 | 3.56 | .02 | 0.39 (0.07 to 0.71) |

| Photo editing | ||||

| Any platform | 3.31 | 3.52 | .17 | 0.21 (−0.09 to 0.51) |

| Snapchat filters | 3.26 | 3.70 | .002 | 0.44 (0.16 to 0.72) |

| Facetune | 3.41 | 4.34 | .005 | 0.94 (0.29 to 1.59) |

Significance testing was 2-sided, with a significance threshold of P < .05.

Photo Editing

Snapchat filter users had a higher mean acceptance of cosmetic surgery score across all ACSS domains compared with nonusers (Table 2). Increased consideration of cosmetic surgery but not overall acceptance of surgery was noted in users of VSCO (difference in ACSS score means, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.32-1.35) and Instagram photo filters (difference in ACSS score means, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.01-0.76) compared with nonusers. Participants who reported having “untagged or removed a posted photograph of yourself from social media because it was not digitally edited or enhanced to your liking” also had a higher ACSS score (difference in ACSS score between participants reporting yes and participants reporting no, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.33-0.92) compared with participants who did not report removing posted self-images. Of the 252 survey participants, 166 (65.87%) reported using photo editing applications to make changes in photo lighting (eg, adding filters or adjusting brightness, contrast, and warmth), and 13 (5.16%) reported using these applications to make changes in body or face shape. There was no significant difference in overall ACSS score between participants who reported making lighting edits and those who did not. Participants who reported making face reshaping edits had a higher ACSS consider domain score (difference in mean ACSS score, 1.74; 95% CI, 0.61-2.87) than nonusers.

Structural Equation Modeling

Results of structural equation modeling (Table 3 and Table 4) showed that social media investment and self-worth were positively associated with ACSS consideration of cosmetic surgery scores. For each additional point on the CSW contingent on appearance, the ACSS consideration score increased by 0.47 points. For each additional point in social media investment, the ACSS consideration score increased by 0.35 points.

Table 3. Structural Equation Model Analysis for Consideration of Cosmetic Surgery.

| Type of Analysis | Regression Coefficient (SE) [95% CI] | Constant | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable Predictionb | |||

| Covariates for social media investment | |||

| Time spent on social media, h/d | 1.42 (0.55) [0.34 to 2.50] | 2.79 | .01 |

| Images posted on social media, No./wk | 10.64 (3.61) [3.56 to 17.72] | 11.21 | .01 |

| Regression, R | |||

| Covariates for consideration of cosmetic surgery | |||

| Self-worth contingent on appearance | 0.47 (0.10) [0.28 to 0.66] | NA | <.001 |

| Social media investment | 0.35 (0.16) [0.04 to 0.66] | NA | .03 |

| Constant | 0.91 (0.47) [−0.02 to 1.84] | NA | .05 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Significance testing was 2-sided, with a significance threshold of P < .05.

Data for the number of social media applications used were constrained.

Table 4. Structural Equation Model Analysis for Random Effects.

| Variable | Variance Estimate (SE) [95% CI] |

|---|---|

| Time spent on social media, h/d | 2.59 (0.67) [1.55-4.31] |

| Images posted on social media, No./wk | 579.63 (63.07) [468.31-717.42] |

| No. of social media applications used | 4.36 (0.51) [3.45-5.49] |

| ACSS consideration of cosmetic surgery score | 1.95 (0.18) [1.62-2.35] |

Abbreviation: ACSS, Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale.

Discussion

A primary motivator for patients seeking cosmetic surgery is the desire to look better in photographs. The rising trend of pursuing cosmetic surgery based on social media inspiration highlights the need to better understand patients’ motivations to seek cosmetic surgery. To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure the association between social media and photo editing use and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. The findings suggest that the following factors were associated with increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery: use of YouTube, Tinder, Snapchat, and/or Snapchat filters; basing one’s self-worth more contingent on appearance; and having removed selfies from social media because “it was not digitally edited or enhanced to your liking.” Increased social media investment and the use of Instagram photo filters and/or VSCO photo editing applications were associated with increased consideration of cosmetic surgery.

The data analysis (Table 3) suggests that increased social media investment may be associated with an increased likelihood to consider cosmetic surgery. Past literature has examined the negative psychosocial effects of social media on self-esteem. Perloff described the relationship between social media use and body image as mutually reinforcing: those who have body image concerns are more drawn to activities like social media that focus strongly on appearance and provide the means to seek gratification for body image concerns. At the same time, social media engagement may exacerbate an individual’s body image concerns through active comparison with peers. Consistent with Perloff, this study shows that participants who use social media platforms such as YouTube tend to have lower self-esteem. Because YouTube allows users to access beauty-related videos while connecting with other users interested in cosmetics, the platform may generate appearance comparisons between users that can harm self-esteem. This study further found that YouTube users have, in addition to lower self-esteem, higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery. This association is perhaps mediated by previous research reporting that the desire to improve psychosocial well-being (ie, the desire to feel happier and more confident) and aesthetic appearance are clear motivators for patients seeking cosmetic surgery.

These findings also suggest that ACSS scores vary based on social media and photo editing application use. WhatsApp users had a lower acceptance of cosmetic surgery compared with nonusers, and YouTube, Tinder, and Snapchat users had a higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery compared with nonusers (Table 2). The differences in cosmetic surgery acceptance may be associated with the features and functions of the applications themselves. For instance, WhatsApp is a smartphone instant messaging application that enables users to exchange text messages, free of charge and in real time, with individuals or friend groups. WhatsApp users connect with other users whom they perceive have relationships close enough with them to be in direct texting communication. Because they primarily interact with friends on WhatsApp, users may be less influenced by the ideas of users outside their direct friend network. In contrast, YouTube allows users to comment on and share videos with all other YouTube users. YouTube users are therefore exposed to a broader scope of social media influence, which may be associated with higher ACSS scores. Tinder is a smartphone dating application that emphasizes self-appearance through the display of profile pictures on public dating profiles. Validation of self-worth is a prominent motivation for people to join and use Tinder, likely contributing to the higher ACSS scores among its users. Finally, Facebook users had no significant difference in ACSS scores compared with nonusers. Facebook allows users to primarily interact with friends whom they personally verify and add to their network. The narrow scope of self-defined Facebook friends renders its users less influenced by all Facebook users and, similar to WhatsApp, results in fewer associations between application use and ACSS scores.

The results of this study regarding the association between photo editing and attitudes toward surgery were unexpected. The structural equation model for photo editing did not have adequate power to determine an overall significant association between photo editing investment and ACSS scores. One explanation for this result may be that, in contrast to social media use, photo editing application use does not affect self-esteem enough to drive interest in cosmetic surgery. The study data noted no difference in self-esteem scores between participants who reported using at least 1 photo editing application and those who did not. This finding is consistent with previous literature, which reported that selfie manipulation did not significantly affect body dissatisfaction. Social media, in comparison with photo editing, may provide users with more active engagement in self-appearance through the practice of seeking, comparing, and commenting on social media content, which may result in a more evident association between social media use and cosmetic surgery attitudes. In addition, a wide variety of photo editing features exist, including tools that allow users to make general photo (eg, lighting) and body-specific (eg, reshaping facial features) changes. The use of photo editing features to make lighting changes had no significant association with cosmetic surgery attitudes. In contrast, the use of photo editing features to alter facial features was associated with increased consideration of surgery. Given the broad range of photo editing features, the association between the use of photo editing as a whole and attitudes toward surgery was not significant.

Limitations

The current study is not without limitations. Because the survey was web based, the participant population was skewed to a younger demographic that was more social media savvy. All study participants reported using at least 1 social media application. This response may have resulted from the survey’s distribution though social media sites, including Reddit and Facebook, and university email lists. The study population sufficiently matched the demographics of young people seeking cosmetic surgery but was not representative of the overall population of patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Studies have reported that patients aged 18 to 24 years compose only 24% of the demographic age range of patients who seek cosmetic surgery. Furthermore, the web-based survey provided us with only cross-sectional data, and a longitudinal study would provide a more accurate measurement of the association between social media use and the general population’s attitudes toward surgery over time. Future studies can obtain longitudinal sample populations drawn from all age ranges to better represent the population of patients seeking cosmetic surgery.

We also recognize that a multitude of factors, including those not measured in this study, can indicate an individual’s investment in social media and photo editing applications. Previous literature discussed factors, including the number of social networking site friends and the reasons for social media use, that may also contribute to an individual’s overall social media investment. To account for these unobserved factors, the structural equation model used the latent variable of social media investment. Future studies with larger samples may further elucidate the association between photo editing investment and cosmetic surgery attitudes.

Conclusions

These data suggest that higher investment in social media and the use of specific social media and photo editing applications are associated with increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery. This study lays the foundation for describing the association between self-esteem, social media and photo editing application use, and perceptions of cosmetic surgery, which can help guide future patient-physician discussions regarding surgical outcomes and expectations.

References

- 1.Ramphul K, Mejias SG. Is “Snapchat dysmorphia” a real issue? Cureus. 2018;10(3):e2263. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Selfies—living in the era of filtered photographs. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(6):443-444. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH, Masters J. Photoshopping the selfie: self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(8):1132-1140. doi: 10.1002/eat.22449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang R, Yang F, Haigh MM. Let me take a selfie: exploring the psychological effects of posting and viewing selfies and groupies on social media. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34(4):274-283. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brucculieri J. “Snapchat dysmorphia” points to a troubling new trend in plastic surgery. HuffPost https://www.huffpost.com/entry/snapchat-dysmorphia_n_5a8d8168e4b0273053a680f6. Published February 22, 2018. Accessed January 6, 2019.

- 7.Hosie R. More people want surgery to look like a filtered version of themselves rather than a celebrity, cosmetic doctor says. Independent https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/cosmetic-surgery-snapchat-instagram-filters-demand-celebrities-doctor-dr-esho-london-a8197001.html. Published February 6, 2018. Accessed January 6, 2019.

- 8.Smith A, Anderson M Social media use in 2018. Pew Research Center website. https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/. Published March 1, 2018. Accessed June 1, 2018.

- 9.Crocker J, Wolfe CT. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(3):593-623. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson-King D, Henderson-King E. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: scale development and validation. Body Image. 2005;2(2):137-149. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maisel A, Waldman A, Furlan K, et al. Self-reported patient motivations for seeking cosmetic procedures. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1167-1174. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perloff RM. Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles. 2014;71(11-12):363-377. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church K, de Oliveira R What’s up with WhatsApp? comparing mobile instant messaging behaviors with traditional SMS. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services; August 30, 2013; Munich, Germany. https://www.ic.unicamp.br/~oliveira/doc/MHCI2013_Whats-up-with-whatsapp.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 14.Sumter SR, Vandenbosch L, Ligtenberg L. Love me Tinder: untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34(1):67-78. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergman SM, Fearrington ME, Davenport SW, Bergman JZ. Millennials, narcissism, and social networking: what narcissists do on social networking sites and why. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;50(5):706-711. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]