Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Post-marketing comparative trials describe medication use patterns in diverse, real-world populations. Our objective was to determine if differences in rates of adherence and tolerability exist among new users to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI’s).

Design:

Pragmatic randomized, open label comparative trial of AChEI’s currently available in the United States.

Setting:

Four memory care practices within four healthcare systems in the greater Indianapolis area.

Participants:

Eligibility criteria included older adults with a diagnosis of possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease (AD) who were initiating treatment with an AChEI. Participants were required to have a caregiver to complete assessments, access to a telephone, and be able to understand English. Exclusion criteria consisted of a prior severe adverse event from AChEIs.

Intervention:

Participants were randomized to one of three AChEIs in a 1:1:1 ratio and followed for 18 weeks.

Measurements:

Caregiver-reported adherence, defined as taking or not taking study medication, and caregiver-reported adverse events, defined as the presence of an adverse event.

Results:

196 participants were included with 74.0% female, 30.6% African Americans, and 72.9% who completed at least 12th grade. Discontinuation rates after 18 weeks were 38.8% for donepezil, 53.0% for galantamine, and 58.7% for rivastigmine (p=0.063) in the intent to treat analysis. Adverse events and cost explained 73.1% and 25.4% of discontinuation. No participants discontinued donepezil due to cost. Adverse events were reported by 81.2% of all participants; no between-group differences in total adverse events were statistically significant.

Conclusions:

This pragmatic comparative trial showed high rates of adverse events and cost-related non-adherence with AChEIs. Interventions improving adherence and persistence to AChEIs may improve AD management.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer’s, clinical care

Introduction

Post-marketing clinical trials embedded within clinical environments provide valuable opportunities to capture natural treatment patterns within the real-world care environment. Comparative effectiveness research conducted in clinical practice can maximize the advantages of observational research through minimally intrusive data collection, and introduce strengths of experimental research by introducing methods such as randomization. Comparative effectiveness trials are an ideal way to capture treatment patterns and clinical outcomes among real-world populations suffering from multiple comorbidities that are often excluded from industry-sponsored trials.

The pro-cholinergic drugs tacrine, donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine have been the standard of care for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) for more than two decades. These medications do not alter the natural history of the disease but they are believed to delay progression of cognitive and functional decline, and minimize behavioral disturbances.1, 2 In a Cochrane Systematic Review of 13 randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trials of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) in the treatment of dementia, one in three stopped treatment due to adverse effects.1

Both cost and tolerability limit use of AChEI in older adults with dementia, however no randomized trial has been conducted which directly compared adherence of all three treatments currently available. Industry-sponsored data report discontinuation rates due to adverse events between 5–15%,3–5 whereas post-marketing cohort studies have reported discontinuation due to adverse events up to 35% as early as 12 weeks after initiation.6–8 Existing studies were commonly conducted outside of the United States and often in populations with low levels of comorbidity with low rates of discontinuation due to adverse events,6,8 suggesting the impact of comorbid disease and multiple medications is under-represented.9,10

Despite differences among the AChEI in pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic properties, no clinically-relevant differences in efficacy outcomes have been consistently reported.1, 2, 11,12 However no randomized trial has directly compared safety and adherence in the three treatments available in the United States (tacrine withdrawn from the market in 2012). Our objective was to determine if differences in adherence and adverse events of AChEI exist in a real-world clinical setting among new users of AChEI.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The study design was a pragmatic, randomized open-label clinical trial to compare adherence to and tolerability of the three AChEIs approved for treatment of AD. The setting and study methods have been previously published and are described below (http://Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01362686).13 Participants were enrolled from one of four healthcare systems within the metropolitan Indianapolis area. Each memory care practice within these healthcare systems provides outpatient geriatric and dementia care that includes expert evaluation of cognitive health, including comprehensive neuropsychologic testing, and other laboratory and imaging parameters recommended in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia. Providers in these healthcare systems include both physicians and nurse practitioners, and each facility has access to neuropsychologic support in the interpretation of neuropsychologic assessments.13 Patients, families, and primary care providers are the primary source of referrals. One institution also participated in a voluntary dementia screening study beginning in 2012 (CHOICE study: R01AG040220); otherwise no systematic screening approaches for dementia existed in the remaining primary care environments at the time of this study.

Participants

Eligible participants included those diagnosed with possible or probable AD by geriatric and dementia experts within memory care practices of the four healthcare systems participating in the study in central Indiana. Complete eligibility criteria require (1) the provider’s intent to initiate therapy with a AChEI; (2) consent from a legally authorized representative and agreement from a caregiver to complete the study outcome assessments; (3) access to a telephone, and (4) the ability to understand English. Patients are referred to study sites for cognitive or functional assessments. Although the intended target population were those deemed by the provider as candidates for initiation of an AChEI, prior exposure to this class of medications was not a contraindication for eligibility. Those currently receiving AChEI therapy, or those whose prior exposure to AChEI resulted in an adverse event that prevented rechallenge, were excluded. Enrollment was conducted by clinical or research staff at each study site, and follow-up interviews were conducted by centrally located research staff.

Intervention and randomization

The study intervention is limited to the initial treatment allocation, determined by the randomization method described below. Beyond the initial treatment selection, the study followed a naturalistic, pragmatic design to accommodate the real-world clinical setting. Although providers were required to prescribe the AChEI generated from the randomization procedure, the protocol allowed providers the discretion to prescribe the dosage form and titrate the dose based on their clinical impression throughout the study period in concordance with routine clinical care. Similarly, in those who did not tolerate, could not afford, or did not take the assigned AChEI for any other reason, discontinuation or changes to another AChEI were allowed at the discretion of the provider.

The randomization process allocated participants to either donepezil (Aricept™), rivastigmine (Exelon™), or galantamine (Razadyne™) in a 1:1:1 ratio and was stratified by study site to avoid demographic or clinical differences by location. A computer-generated randomization scheme was implemented in REDCap, the online Research Electronic Data Capture web-based system for data collection available to the Clinical and Translational Science Institutions. Staff from each participating memory care practice had access to the REDCap system to follow the randomization protocol.

Regional health information exchange

Each participating study site contributes electronic medical record information to the Indiana Network for Patient Care (INPC). The INPC was developed in 1995 by the Regenstrief Institute as the first regional health information exchange. INPC has grown to integrate clinical information from health care systems throughout the state of Indiana and includes pharmacy, laboratory, encounter, diagnosis and procedural codes and a variety of other documentation notes and reports.14

The INPC provided diagnostic and pharmacy data to compare comorbidities within the study population. We used pharmacy data from the INPC to calculate a Chronic Disease Score (CDS).15,16 The CDS maps medication classes to chronic disease, which are then weighted for the risk of either mortality (CDS-Mortality) or healthcare utilization (CDS-Healthcare). We have previously used these measures to correlate comorbidity scores with mortality and healthcare utilization.17

Outcome assessment

Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected by clinic and research staff at baseline, and outcome assessments collected at weeks 6, 12, and 18 by telephone interviews with the participant’s caregiver. The first participant was enrolled on May 2, 2011, with the final participant enrolled on April 27th, 2014; follow-up concluded on September 15th, 2014. Research staff conducting follow-up interviews were initially blinded to the randomization allocation, however staff did collect medication-specific adverse event information for any dementia medication participants were currently taking. The primary outcome was caregiver-reported adherence to study medication, reported as taking the randomly-allocated drug (Intention-to-treat analysis) or any drug in the class (per protocol analysis). If study medication was discontinued, the reason for discontinuation was reported as an adverse event, cost, forgetfulness to either fill the prescription or consume the medication as directed, or discontinuation by the physician for any other reason. The secondary outcome was caregiver-reported adverse events, defined as an adverse event thought to be due to study medication. Adverse events were collected through both voluntary report and as a forced-checklist of events. Research staff also collected care-giver reported response to adverse events: reported as hospital or emergency department admission, outpatient visit to the participant’s physician, receipt of a new medication to treat the adverse event, discontinuation of study medication, or other action taken as a result of the adverse event.

Power and statistical analysis

Our original sample size assumptions were based on discontinuation rates from phase III clinical trials and database analyses of new users of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and assumed a 15% discontinuation rate for donepezil, and 35% discontinuation rates for rivastigmine and galantamine within the 18 week study period.1,18 Our planned sample size of 300 participants would have provided 88% power to detect the difference between donepezil and each of the other study medications at a two-tailed significance level of 0.05.13 A planned mid-point analysis conducted by the external data safety and monitoring board reviewed a blinded outcome analysis and progress on enrollment. Given a higher rate of discontinuation and lower rate of recruitment than anticipated, the board approved early termination of the study after 200 participants were enrolled.

We used Chi-square tests and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) models to test for differences in demographics and comorbidities between the three randomized groups. Logistic regression models were used to test for differences in adherence (intention-to-treat and per protocol) rates between the three groups. The Holm Stepdown method of adjusting for multiple comparisons was used when significant differences between the three study groups were found.19

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, as well as each participating healthcare system. Informed consent was provided by each participant’s legally authorized representative.

Results

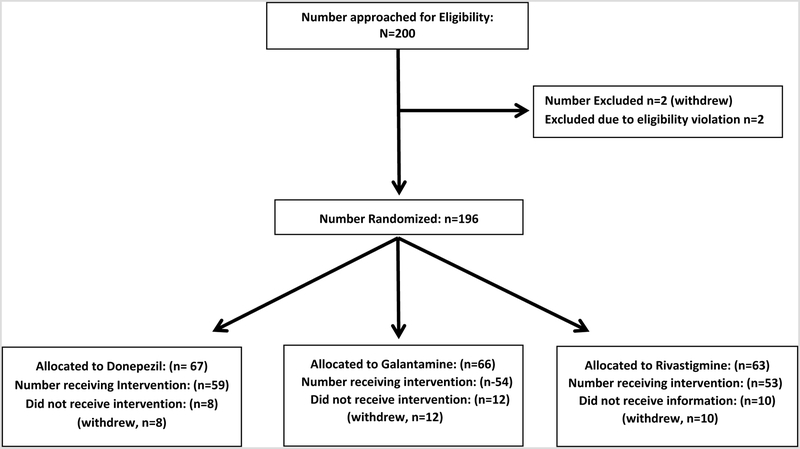

The figure reports the flow diagram for the 196 participants who provided consent for the study and were included in the analysis. Demographic characteristics of the enrolled population are shown in table 1, with overall characteristics of 74.0% females, 30.6% African American, and 72.9% completing at least a high school education. The mean number of prescription medications captured from medical records of the INPC health information exchange was 8.4 for all participants. Table 1 shows that no differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were identified between study groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| Overall (n = 196) | Donepezil (n=67) | Galantamine (n=66) | Rivastigmine (n=63) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 80.2 (8.4) | 79.1 (7.6) | 80.1 (9.6) | 81.6 (7.8) | 0.264 |

| Gender | 0.300 | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 51 (26.0%) | 19 (28.4%) | 20 (30.3%) | 12 (19.0%) | |

| Female, n (%) | 145 (74.0%) | 48 (71.6%) | 46 (69.7%) | 51 (81.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.641 | ||||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 5 (2.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Not Hispanic, n (%) | 188 (95.9%) | 66 (98.5%) | 62 (93.9%) | 60 (95.2%) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Race | 0.204 | ||||

| Other, n (%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| African American, n (%) | 60 (30.6%) | 26 (38.8%) | 21 (31.8%) | 13 (20.6%) | |

| White, n (%) | 134 (68.4%) | 41 (61.2%) | 44 (66.7%) | 49 (77.8%) | |

| Education | 0.619 | ||||

| Less than HS, n (%) | 17 (8.8%) | 4 (6.0%) | 8 (12.5%) | 5 (7.9%) | |

| Some HS, n (%) | 34 (17.5%) | 14 (20.9%) | 7 (10.9%) | 13 (20.6%) | |

| HS Graduate, n (%) | 67 (34.5%) | 23 (34.3%) | 21 (32.8%) | 23 (36.5%) | |

| Some College, n (%) | 76 (39.2%) | 26 (38.8%) | 28 (43.8%) | 22 (34.9%) | |

| Caregiver Relationship to Patient | 0.615 | ||||

| Spouse, n (%) | 40 (25.0%) | 15 (26.8%) | 12 (22.6%) | 13 (25.5%) | |

| Daughter, n (%) | 75 (46.9%) | 26 (46.4%) | 24 (45.3%) | 25 (49.0%) | |

| Son, n (%) | 24 (15.0%) | 5 (8.9%) | 10 (18.9%) | 9 (17.6%) | |

| Other, n (%) | 21 (13.1%) | 10 (17.9%) | 7 (13.2%) | 4 (7.8%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Vascular Disease, n (%) | 35 (25.7%) | 13 (25.5%) | 13 (27.1%) | 9 (24.3%) | 0.958 |

| COPD, n (%) | 36 (26.5%) | 14 (27.4%) | 11 (22.9%) | 11 (29.7%) | 0.764 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 77 (56.6%) | 33 (64.7%) | 24 (50.0%) | 20 (54.0%) | 0.315 |

| CHF, n (%) | 67 (49.3%) | 25 (49.0%) | 25 (52.1%) | 17 (46.0%) | 0.854 |

| Affect Disorder, n (%) | 64 (47.1%) | 23 (45.1%) | 21 (43.8%) | 20 (54.0%) | 0.602 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 25 (18.4%) | 10 (19.6%) | 12 (25.0%) | 3 (8.1%) | 0.132 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 81 (59.6%) | 28 (54.9%) | 32 (66.7%) | 21 (56.8%) | 0.452 |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 47 (34.6%) | 16 (31.4%) | 15 (31.2%) | 16 (43.2%) | 0.428 |

| CDS Score – Health Care* | 0.798 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.6 (4.5) | 7.3 (4.5) | 7.8 (4.8) | 7.8 (4.0) | |

| CDS Score – Mortality * | 0.840 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (3.5) | 5.4 (3.5) | 5.9 (3.9) | 5.8 (2.9) | |

| Dispensed Prescription Medications | 0.818 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (4.7) | 8.0 (5.1) | 7.9 (4.4) | 8.6 (4.7) |

CDS: Chronic Disease Score derived from dispensed pharmacy data 12 months prior to enrollment

Table 2 presents 18-week results of the intention-to-treat and per protocol analysis, which reports adherence by randomization group (intention-to-treat), and by medication consumed if randomized drug was not initiated (per protocol); the per protocol analysis accounts for participants who never consumed the medication they were randomized to receive, most often due to cost limitations (usually due to lack of coverage by insurance provider). Adherence data was obtained on 84.7% (166/196) of enrollees. There were no significant differences between patients who withdrew and patients who continued in the study.

Table 2.

Adherence rates by both intention-to-treat and per protocol analysis.

| Intention to Treat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil (n=67) | Galantamine (n=66) | Rivastigmine (n=63) | p-value | |

| Non-adherent, n (%)* | 26 (38.8%) | 35 (53.0%) | 37 (58.7%) | 0.063 |

| Reasons for non-adherence: | ||||

| Withdrew/lost to follow-up (no outcome assessment) | 8 (11.9%) | 12 (18.2%) | 10 (15.9%) | 0.599 |

| Cost, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (13.6%) | 11 (17.5%) | 0.002 |

| Adverse drug event, n (%) | 13 (19.4%) | 12 (18.2%) | 13 (20.6%) | 0.974 |

| Forgot, Lost, Never started, n (%) | 4 (6.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0.406 |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1.000 |

| Per Protocol# | ||||

| Donepezil (n=79) | Galantamine (n=46) | Rivastigmine (n=41) | p-value | |

| Non-adherent, n (%)* | 19 (24.1%) | 15 (32.6%) | 16 (39.0%) | 0.218 |

| Reasons for non-adherence: | ||||

| Cost, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.524 |

| Adverse drug event, n (%) | 14 (17.7%) | 12 (26.1%) | 13 (34.1%) | 0.193 |

| Forgot, Lost, Never started, n (%) | 4 (5.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0.784 |

| Unknown | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1.000 |

Adherence defined as caregiver-report of continued medication use. P-value for difference between groups is 0.063 for Intent-to-treat analysis, and 0.218 for per-protocol analysis.

The per protocol analysis reports study groups by the medication received, and excluded those who withdrew and/or did not complete an outcome assessment.

Overall, 50% of the population discontinued or did not initiate the treatment they were randomized to receive in the intent to treat analysis. Among those who were non-adherent and completed at least one outcome assessment, adverse events were the most common reason for discontinuation of the randomized study drug (55.9%), followed by cost (29.4%). No caregiver reported cost as a reason for discontinuation of donepezil. The adherence rates did not significantly differ (p=0.063) across the three groups. Non-adherence due to cost differed by study group (p=0.002, intent to treat analysis); participants randomized to the donepezil group had significantly lower cost-related non-adherence than those randomized to galantamine (p=0.002) and those randomized to rivastigmine (p=0.001). There was no difference in cost-related non-adherence between galantamine and rivastigmine groups (p=0.628). The adherence rates are not significantly different (p=0.218) when examining the data by medication actually consumed (per protocol analysis) when excluding cost/insurance as a reason for non-adherence.

Table 3 reports rates of severe adverse events resulting in an acute care visit (hospital or emergency department), an outpatient visit, or a new medication to treat an adverse event. Among 121 severe adverse events, 45% occurred in conjunction with at least one other adverse event. The most common result of a severe adverse event was an outpatient visit (23% of events) and receipt of a new medication (21% of events). Thirty-one percent of severe adverse reactions resulted in discontinuing study medication, regardless of an interaction with a provider. Cumulative rates of adverse events reported by caregivers are presented by medication consumed in supplementary table S1. Overall, 81.2% of caregivers reported an adverse event due to study medication. Only nightmares were more common in those taking donepezil (p=0.044). Gastrointestinal, neurological, and musculoskeletal adverse events were the most common events for each medication.

Table 3:

Proportion of study participants experiencing severe adverse events

| Donepezil (n=79) | Galantamine (n=46) | Rivastigmine (n=41) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular - total | 8.8% | 6.5% | 12.2% |

| Fast or slowed heart rate | 7.6% | 0.0% | 7.3% |

| Irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) | 6.3% | 6.5% | 4.9% |

| Neuro – all other | 31.7% | 23.9% | 26.8% |

| Fainting | 2.5% | 2.2% | 4.9% |

| Dizziness | 6.3% | 13.0% | 17.1% |

| Nightmares | 8.9% | 4.4% | 2.4% |

| Headache | 10.1% | 4.4% | 7.3% |

| Seizures or fits | 1.3% | 2.2% | 0.0% |

| Sleeplessness or poor sleep (insomnia) | 12.7% | 4.4% | 14.6% |

| Gastrointestinal – total | 26.6% | 19.6% | 29.3% |

| Upset stomach | 15.2% | 6.5% | 19.5% |

| Vomiting | 5.1% | 6.5% | 7.3% |

| Diarrhea | 16.5% | 10.9% | 17.1% |

| Lack of interest in eating (anorexia) | 12.7% | 4.4% | 9.8% |

| Musculoskeletal – total | 25.3% | 21.7% | 26.8% |

| Muscle cramps | 8.9% | 10.9% | 4.9% |

| Pain | 6.3% | 13.0% | 7.3% |

| Falls | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.3% |

| Feeling tired (Fatigue) | 11.4% | 6.5% | 7.3% |

| Tremor or shaking | 7.6% | 2.2% | 7.3% |

| Incontinence – total | 11.4% | 8.7% | 7.3% |

| Incontinence of urine or stool | |||

| Respiratory – total | 3.8% | 8.7% | 4.9% |

| Asthma/wheezing or trouble breathing | |||

| Entorhinal – total | 16.5% | 4.4% | 4.9% |

| Runny nose (rhinitis) |

Interaction may have included any or more than one of the following: acute care visit (hospital or emergency department), outpatient visit, or receipt of a new medication to treat an adverse event.

p-value for difference between groups: entorhinal total = 0.048

p-value for difference between groups: falls = 0.014

Using the per protocol analysis, table 4 describes the proportions of study participants who achieved and sustained the maximum dosage of medication they received. Maximum doses were defined as at least 10 mg/day for donepezil, 12mg twice daily by mouth or 24mg extended-release once daily by mouth for galantamine, and 6mg twice daily by mouth, or at least the 9.5 mg patch for those receiving rivastigmine.Participants using rivastigmine were more likely to achieve maximum dose if using the patch dosage form compared to the oral form (7/20 with patch vs. 0/16 with oral form). Among participants using any form of galantamine, those using the XR formulation experienced a higher proportion of severe adverse events (71% of galantamine XR users vs. 36% of users of galantamine regular release). No difference in the rate of overall adverse events (or severe adverse events) was identified among participants using different forms of rivastigmine. Among those not achieving maximum dose, 66.7% of donepezil users were adherent to a lower dose of study medication, 75.7% of galantamine users were adherent to a lower dose, and 62.1% of rivastigmine users were adherent to a lower dose.

Table 4:

Proportion of study participants in Per Protocol analysis achieving and maintaining maximum dose of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

| % Achieving Max Dose | % Achieving Max Dose on last interview | |

|---|---|---|

| Donepezil (n=76) | 52.6% | 42.9% |

| Galantamine *(n=39) | 5.1% | 2.6% |

| Rivastigmine^(n=36) | 19.4% | 16.7% |

Once-daily dosage form prescribed to 35.9% of participants taking galantamine

Patch dosage form prescribed to 55.6% of participants taking rivastigmine

Discussion

Results from our trial show that adverse events and cost-related non-adherence are common among new users of AChEI within 18 weeks of treatment initiation. We used a randomized study design to compare the three pharmacologic treatments, eliminating selection bias inherent in observational studies, and found high rates of non-adherence, but no statistically significant difference in adherence between treatment arms (despite a 20% absolute difference in adherence, donepezil vs. rivastigmine). Although overall differences in adherence rates were not statistically significant, cost-related non-adherence was higher for those randomized to galantamine and rivastigmine than those randomized to donepezil (p=0.002).

The primary difference in rates of adherence between groups in the intent to treat analysis was due to cost. This result is potentially representative of the timeframe of this study (enrollment occurring between 2011–2014). Cost reported as a barrier to adherence was primarily due to coverage from prescription payment programs and availability of generic products, and may not directly reflect the patient/caregiver’s willingness to pay prescription costs. In 2011, donepezil was the only generic medication approved in the United States and became the preferred medication from most third party payers when commercially available in early 2012. Generic forms of galantamine and rivastigmine subsequently became available during the study period. Among medications consumed by our study population, 59% of donepezil users reported using only generic donepezil, 90% of galantamine users reported only receiving generic galantamine, and 28% of rivastigmine users reported receiving only generic rivastigmine. Although generic availability has increased since initiation of our study, some plans continue to list generic AChEI’s (particularly galantamine and rivastigmine) in the most costly coverage tiers. Because costs influenced adherence in our study, we expect poor adherence to certain AChEI’s until all generic medications are competitively priced.

The discontinuation rates identified in our pragmatic comparative trial are notably higher than those reported by industry-sponsored trials,3–5 several observational studies8, 18–24 and randomized trials comparing two treatments.7, 25 Not surprisingly, discontinuation rates due to adverse events in pre-marketing clinical trials are reported at much lower rates of 5–13% for mild-moderate AD.3–5 Observational studies from Italian and Spanish populations report variable discontinuation rates of 16.4% and 36.7%, respectively.6,12 Other studies reporting from administrative and claims databases have reported discontinuation rates up to 31.2% at 6 months and 67% at 14 months.12, 21–24

Two randomized trials have compared donepezil with either rivastigmine or galantamine. Wilkinson and colleagues report a randomized trial comparing donepezil and rivastigmine in an international sample of older adults with mild-moderate AD, with discontinuation rates due to adverse events of 10.7% for the donepezil and 21.8% for the rivastigmine groups.7 A second study comparing galantamine and donepezil in 188 older adults in the United Kingdom found discontinuation rates due to adverse events of 13.4% (galantamine) and 13.2% (donepezil).25 Differences between our results and prior randomized trials likely reflect the degree of comorbidity and use of concomitant medications between populations included in international studies compared to our mid-west American sample.

We also identified notable differences in rates and distribution of adverse events in our real-world populations compared with those reported in industry-sponsored trials. Interestingly, the rate of adverse events reported in our study occurred despite few participants achieving recommended doses. Gastrointestinal adverse events in industry-sponsored trials report rates from 19% in donepezil trials3 to 47% in rivastigmine trials.4 Gastrointestinal adverse events, as a group, were reported at a rate of approximately 50% by our population. Notably, central nervous system and musculoskeletal system adverse events were reported by approximately 50% of our study population as well, whereas rates reported in industry-sponsored trials were much lower at approximately 20% and 10%.3–5 Improving tolerability and persistence to AChEIs may improve long-term treatment outcomes and reduce psychotropic use in patients with AD.8

Although this study is the first pragmatic randomized trial of all three AChEIs and has several strengths, some limitations are worth noting. First, with 166 participants included in the analysis, we had 20.8% power to determine the observed effect size between donepezil and galantamine, and 52.2% power to detect the observed difference between donepezil and rivastigmine, thereby introducing the potential for type II error. Second, participant selection is expected to be consistent with the FDA-approved use of the study medications, which includes a diagnosis of probable or possible AD. Such diagnoses may vary by practitioner and result in a heterogeneous mixture of participants with AD with or without mixed pathologies. However, because the intent was to study adherence and tolerability and not efficacy, we expect the impact on generalizability to be minimal. Third, caregiver-reported outcomes may differ from participant-reported outcomes and may complicate the comparison of results to other studies. Additionally, outcome assessors were not blinded to treatment, introducing the potential for measurement bias. Fourth, adverse events were reported through both voluntary and prompted methods, which may have overestimated the prevalence. Adverse events were also reported irrespective of dose; faster titration schedules and higher doses are known to provoke a higher rate of adverse events. However, few participants in our study achieved maximum recommended doses. Lastly, given the 18-week duration of the study, the use of caregiver-reported adherence as our primary outcome may better reflect a measure of early persistence rather than adherence over time.

Findings from this pragmatic comparative trial support tolerability and cost as common reasons reported for discontinuation of AChEI, partially explaining poor penetration of these medications in clinical care.26 This under-treatment phenomenon may result in un-realized therapeutic benefit for the growing population with AD.8 Methods to identify and reduce adverse events may result in a larger proportion of patients benefiting from longer periods of treatment. Similarly, competitive pricing of available generics can minimize cost-related non-adherence between medications in the class. Given that no disease-modifying therapies are currently available, increasing the use of currently-available treatments may reduce the symptom burden and lower costs required to care for the population with AD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1: Cumulative adverse events by medication consumed.

Figure:

Description of participant flow through study procedures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following providers, employees of the memory care practices assisting with subject recruitment and enrollment, and research staff that executed the study: Patrick Healey, MD; Diane Healey, MD; Vijaya Sirigirireddy, MD; Jenny Allbright, RN, BSN, CCM; Indiana Alzheimer’s Disease Center: Martin Farlow, MD; Community Health Network: Margaret Campbell, ANP, GNP; Azita Chehresa, MD; Indiana University Health: Eugene Lammers, MD; Kristine Lieb, MD; Kofi Quist, MD; Tochukwu Iloabuchi, MD; IU Center for Aging Research: Amie Frame, MPH, Amanda Harrawood.

Sponsor’s Role: The trial was funded through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) R01HS019818–01. The funding agency had no role in any of the following: the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the AHRQ.

Funding: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) R01HS019818-01

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Neither the funding agency nor any outside organization had a role in study design, data collection, data analysis, the decision to publish or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Birks J Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2006:CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Yau KK, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J 2003;169:557–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aricept(R) [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Exelon(R) [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razadyne(R) [package insert]. TItusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raschetti R, Maggini M, Sorrentino GC, Martini N, Caffari B, Vanacore N. A cohort study of effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005;61:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson DG, Passmore AP, Bullock R, et al. A multinational, randomised, 12-week, comparative study of donepezil and rivastigmine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Pract 2002;56:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olazaran J, Navarro E, Rojo JM. Persistence of cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in dementia: insights from a naturalistic study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2013;3:48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM, et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell NL, Skaar TC, Perkins AJ, et al. Characterization of hepatic enzyme activity in older adults with dementia: potential impact on personalizing pharmacotherapy. Clin Interv Aging 2015;10:269–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. J Am Med Assoc 2005;293:596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Pousa S, Turon-Estrada A, Garre-Olmo J, et al. Differential efficacy of treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease over a 6-month period. Dement Geriatr Cog Disord 2005;19:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell NL, Dexter P, Perkins AJ, et al. Medication adherence and tolerability of Alzheimer’s disease medications: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Barnes M, Schadow G, Blevins L, Dexter PR, Mamlin B, Committee IM. The Indiana network for patient care: a working local health information infrastructure. An example of a working infrastructure collaboration that links data from five health systems and hundreds of millions of entries. Health affairs 2005;24(5):1214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark DO, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Baluch WM, Simon GE. A chronic disease score with empirically derived weights. Med Care 1995;33:783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins AJ, Kroenke K, Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW, Callahan CM. Common comorbidity scales were similar in their ability to predict health care costs and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1040–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mauskopf JA, Paramore C, Lee WC, Snyder EH. Drug persistency patterns for patients treated with rivastigmine or donepezil in usual care settings. J Manag Care Pharm 2005;11:231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm S A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardette V, Andrieu S, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Predictive factors of discontinuation and switch of cholinesterase inhibitors in community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a 2-year prospective, multicentre, cohort study. CNS Drugs 2010;24:431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh G, Thomas SK, Arcona S, Lingala V, Mithal A. Treatment persistency with rivastigmine and donepezil in a large state medicaid program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1269–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh DC, Thomas SK, Valiyeva E, Arcona S, Vo L. Drug persistency of two cholinesterase inhibitors: rivastigmine versus donepezil in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2005;22:695–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann N, Gill SS, Bell CM, et al. A population-based study of cholinesterase inhibitor use for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kogut SJ, El-Maouche D, Abughosh SM. Descreased persistence to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy with concomitant use of drugs that can impair cognition. Pharmacotherapy 2005;25:1729–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilcock G, Howe I, Coles H, et al. A long-term comparison of galantamine and donepezil in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2003;20:777–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Cumulative adverse events by medication consumed.