Abstract

The goal of therapy is typically to improve clients’ self-management of their problems, not only during the course of therapy but also after therapy ends. Although it seems obvious that therapists are interested in improving client’s self-management, the psychotherapy literature has little to say on the topic. This article introduces Leventhal’s Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation, a theoretical model of the self-management of health, and applies the model to the therapeutic process. The Common-Sense Model proposes that people develop illness representations of health threats and these illness representations guide self-management. The model has primarily been used to understand how people self-manage physical health problems, we propose it may also be useful to understand self-management of mental health problems. The Common-Sense Model’s strengths-based perspective is a natural fit for the work of counseling psychologists. In particular, the model has important practical implications for addressing how clients understand mental health problems over the course of treatment and self-manage these problems during and after treatment.

Keywords: health psychology, counseling psychology, self-management, Common-Sense Model, illness representations

“Patients are in control. No matter what we as health professionals do or say, patients are in control of these important self-management decisions. When patients leave the clinic or office, they can and do veto recommendations a health professional makes” (Glasgow & Anderson, 1999, p. 2090).

“Ultimately the success of therapy hinges on the possibility that clients will generalize changes beyond the context of therapy” (Scheel, Seaman, Roach, Mullin, & Mahoney, 1999, p.308).

The goal of psychotherapy is not only to reduce symptoms and improve functioning during the course of therapy, but also to improve clients’ management of mental health problems in daily life after therapy ends. Arguably, the latter is why people seek out and engage in therapy in the first place. Unfortunately, we have little knowledge of the specific factors that promote clients’ effective self-management of their mental health problems. Moreover, we have little knowledge of how therapists can optimize clients’ self-management.

Viewed as taking responsibility for one’s own behavior and well-being (Lorig & Holman, 2003), self-management is a broad concept that includes promoting one’s health through sleep, physical activity, regular medical check-ups, and so on. Importantly, self-management also includes engaging in mental health promotion, such as increasing self-awareness, gaining insight, and changing how one approaches personal relationships (Lorig & Holman, 2003). Insofar as therapy is a tool for optimizing mental health, we can understand self-management as clients’ meaningful involvement in the therapeutic process, including taking ownership of their therapeutic progress and following the therapist’s recommendations. Although it is known that effective therapy improves clients’ self-management (e.g., Scheel et al., 1999), there is scant literature on factors that promote effective self-management of mental health during and after therapy.

It goes without saying that therapists need to take note of and address clients’ motivation for staying in treatment and for making difficult changes to improve their mental health. Indeed, not all clients are willing or able to assume the necessary responsibility for self-management of mental health concerns. It is estimated that 40% to 60% of clients drop out of treatment prematurely (Baruch, Vrouva, & Fearon, 2009), and one in three mental health appointments are not attended (Lefforge, Donohue, & Strada, 2007). Among clients who do remain in treatment, fewer than 50% adhere to their therapists’ recommendations (Nieuwlaat et al., 2014).

The counseling psychology literature has identified some self-management approaches related to better outcomes, including the use of effective coping (e.g., Sheu & Sedlacek, 2004) and positive problem solving strategies (e.g., Grant, Elliott, Giger, & Bartolucci, 2001; Rath, Hradil, Litke, & Diller, 2011). Although these studies touch on components of self-management, there is no explicit, comprehensive model of the self-management of mental health problems in the counseling psychology literature. This gap is notable since a foundational value in counseling psychology is the strengths-based perspective on clients’ problems in living. In our view, having an empirically supported understanding of how people effectively manage their mental health problems would enhance our ability to effectively intervene with clients.

Several self-management models in the social and health psychology literature may shed light on the self-management of mental health problems (e.g., Control Theory, Self-Determination Theory). To a large extent, however, these models focus on a single aspect of self-management, such as goal setting and achievement (e.g., Janz & Becker, 1984), control (Carver & Scheier, 1982) and motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Few of these models take into account an individual’s phenomenological perspective on self-management or the influence of culture on this perspective – factors that are at the heart of the work of counseling psychologists.

The purpose of this article is to introduce a comprehensive model of self-management of mental health that takes into account clients’ unique, culturally-based perspectives: Leventhal’s Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM; Hale, Treharne, & Kitas, 2007; Leventhal, Weinman, Leventhal, & Phillips, 2008; McAndrew et al., 2008). After describing the model and its empirical support, we apply the model to the therapeutic process. The article concludes with several recommendations for research based on our application of the CSM to psychotherapy.

LEVENTHAL’S COMMON-SENSE MODEL OF SELF-REGULATION

According to the CSM, people are active problem-solvers who purposefully manage threats to health. A health threat is any physical, emotional or social risk that could or does impact a person’s physical or mental health. In response to a health threat, people develop illness representations of the mental or physical health threat that guide their self-management efforts (Leventhal, Leventhal, & Breland, 2011; Leventhal et al., 2008; McAndrew, Mora, Quigley, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 2014; Meyer, Leventhal, & Gutmann, 1985). People then monitor if their self-management improves the health threat and make additional or different self-management changes in response to their monitoring. As a simple example, the onset of a cough and stuffy nose may elicit an illness representation of a short-duration cold that can be treated with rest and chicken soup. The illness representation will also include beliefs about how long the cold will last, the consequences of the cold and the cause of the cold. If the cough and stuffy nose are still present three weeks later, the individual may consider other potential illnesses (e.g., a sinus infection) and use a different self-management approach (e.g., seeking professional help).

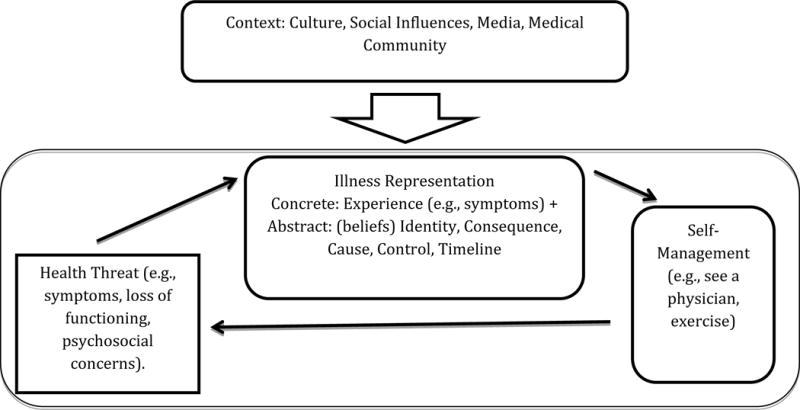

The CSM is a dynamic model as shown in Figure 1. Illness representations are not static. People look for information in their daily life through medical resources, social supports, and their cultural norms, and try to fit this information into their understanding of the health threat. Like a puzzle, people disregard pieces of information that do not make sense, and hold onto information that fits. Further, they constantly monitor their health and use this information to re-evaluate and re-shape their illness representations. As one client explained, “I was self-medicating and drinking a lot back then. I knew I had to stop that. So when I did… I still had the feelings—that’s when I, you know, looked for medical help for the problem” (Elwy et al., 2011, p. 5).

Figure 1.

Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation

There is strong evidence to support the CSM. Physical and mental health representations do guide people’s attitudes and behavior (e.g., “depression is treatable with help from a psychologist and the support of my family;” “I should make an appointment with my doctor and follow her recommendations”; Hagger & Orbell, 2003). Moreover, the CSM has been used to explain variability in mental health outcomes for clients with depression (Hagger & Orbell, 2003; Hampson, Glasgow, & Foster, 1995), anxiety (Spoont, Sayer, & Nelson, 2005), anorexia nervosa (Holliday, Wall, Treasure, & Weinman, 2005) and schizophrenia (Lobban, Barrowclough, & Jones, 2004), as well as physical outcomes for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Zoeckler, Kenn, Kuehl, Stenzel, & Rief, 2014), Parkinson’s disease (Simpson, Lekwuwa, & Crawford, 2013), hypertension (Meyer et al., 1985), cardiovascular disease (Martin et al., 2005), and cancer (Kelly et al., 2005).

Nature of Illness Representations

A central tenet of the CSM is that people create illness representations that guide the interpretation of information about a specific health threat (Leventhal, Brissette, & Leventhal, 2003; McAndrew, Schneider, Burns, & Leventhal, 2007). Illness representations have both concrete and abstract aspects. The concrete aspect of an illness representation refers to the actual experience of the health threat (e.g., intense sadness with the concomitant weight of sorrow, fatigue, and numbness) or the physical memory of that experience (e.g., remembering the weight of sorrow). In contrast, the abstract aspect of an illness representation refers to the cognitive beliefs or perceptions that describe the health threat. The abstract aspect of illness representations arises from the individual’s lived experience with the health threat, as well as from information about the health threat gathered from the medical community, social networks, and the media.

The abstract aspect of illness representations also arise from a person’s cultural framework. Like individuals, cultures have mental models or frameworks for organizing health threats and people draw on these models to develop their personal illness representations (Kleinman & Benson, 2006). For example, as compared to the United States, mental models of grief are different in the People’s Republic of China, where there are culturally prescribed rituals, expectations for the experience of, and a timeframe for experiencing acute grief (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Zhang & Noll, 2005). In the US, the grieving process is focused on helping the bereaved accept the death, in the People’s Republic of China the grieving process is more focused on honoring the dead and helping their transition to the afterlife (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Zhang & Noll, 2005).

The above example of grief can be used to illustrate the five components that comprise the abstract aspect of an illness representation. The abstract aspect of illness representations encompasses its identity (“grief”), consequence (e.g., “I can’t handle life”), cause (e.g., death of a close friend), whether and how it can be controlled or contained (e.g., “hide from the world”), and how long it will last (e.g., “forever”). In other words, the five components of the abstract aspect of an illness representation are: identity, consequence, cause, control, and timeline (Hagger & Orbell, 2003; Leventhal et al., 2003). Each of these components can significantly influence self-management of mental health threats and therefore may be a key target for therapeutic intervention.

Identity

The most commonly described component of illness representations is the identity of the health threat (Fortune et al., 2004), which refers to how the threat is labeled. Identity also refers to the symptoms associated with the health threat.

How a health threat is identified is strongly associated with a person’s approach to self-management and, eventually, to its outcome (Hagger & Orbell, 2003). For example, waking up with a pounding headache may be viewed as the result of stress, depression, migraine, or brain cancer. Each label prompts different self-management strategies. A person’s approach to a headache might be to reduce stress at work, consult a psychologist or a neurologist, or go to the emergency room. Naturally, some self-management approaches are more effective than others depending on the root cause of the health threat.

Identity labels are influenced by gender and culture. As one example, there is a long history of identifying women’s physical symptoms as a stress response (somatization, hysteria) rather than as symptoms of cardiovascular disease (Martin et al., 2004; Martin & Lemos, 2002). In one study (Martin et al., 2004), men and women were interviewed immediately following a heart attack. Compared to their male counterparts, women were less likely to attribute their pre-hospitalization symptoms to heart disease. Further, when these women sought advice from others, including medical professionals, they were less likely to be advised that their symptoms could reflect a serious heart condition. Because the women were less likely to label their symptoms as a heart attack, they tended to delay seeking care, which increased their risk of morbidity and mortality (Martin et al., 2005).

Identity labels are modified by experiences with the health condition and healthcare. As illustrated in the following quote from a study on illness representations of patients seeking help for depression in primary care (Elwy, Yeh, Worcester, & Eisen, 2011), a health threat originally labeled as a personality flaw was reattributed to a mental health problem.

After all these years growing up with it, uh, I didn’t know what it was. Nobody else knew what it was. And I was finally diagnosed. The reason I feel like this way. So it was a good thing that it was finally presented to me that I have a mental problem (p. 5).

Consequence

The second component of an illness representation is the consequence of the health threat. Health threats are perceived along a continuum from not serious, to somewhat serious, to highly serious; perceiving a health threat as “somewhat serious” is associated with relatively better outcomes (Hagger & Orbell, 2003).

On the other hand, perceiving a health threat as highly serious, with extreme consequences, is associated with poor psychological well-being, diminished social and role functioning and vitality, and heightened psychological distress (Hagger & Orbell, 2003). Health threats that are viewed as having extremely serious consequences are associated with poorer outcomes, above and beyond objective measures of a person’s health status. This is because threats that are seen as very serious tend to reduce self-management through avoidance (Heijmans, 1998).

Threats that are seen as not serious with few negative consequences also reduce self-management by not promoting healthcare seeking (McKinley, Moser, & Dracup, 2000). Depression, for example, is often viewed as impairing, but not serious. For this reason, people with depression tend to delay seeking psychological care for an average of eight years (Wang et al., 2005).

Health threats also have perceived social consequences. Like some physical health threats (e.g., HIV), many mental health threats are viewed as stigmatizing (Vogel, Wade, & Hackler, 2007). Perceptions of greater stigma are generally associated with less likelihood of seeking treatment, poor adherence and dropout (Sirey et al., 2001). Consider the quote below from a client who had delayed treatment due to the stigma surrounding mental illness.

I regret not going to the hospital. I listened to too many people and I suddenly thought I am going to be labelled a loony. I wasn’t aware obviously because it hadn’t happened to me before so I was…yet it did stop me from going there. (Dinos, Stevens, Serfaty, Weich, & King, 2004, p. 178)

Cause

Another component of an illness representation is the perceived cause of the health threat. Causal attributions are powerful predictors of self-management, including the type and frequency of healthcare utilization (Sensky, MacLeod, & Rigby, 1996). People who attribute their problems, such as loss of employment, to normal aspects of life are less likely to seek healthcare than people who view life changes as a sign of a physical or mental health disorder (Elwy et al., 2011).

Perceptions of cause are highly influenced by cultural beliefs. In one study, for example, Karasz (2005) compared white women’s illness representations of depression to South Asian women’s illness representations. After reading a narrative of a depressed woman, the South Asian participants were more likely to attribute the cause of the depressive symptoms to a social stressor (e.g., husband cheating). In contrast, the white women were more likely to use a western medical model of depression and attribute the cause of the depression to both social (e.g., divorce) and biological (e.g., hormonal) problems. Cultural beliefs about the cause of depressive symptoms framed how the women interpreted the narrative.

Control

Another component of illness representations are beliefs about control. Perceiving greater control over a health threat typically leads to more active self-management, resulting in better outcomes (Hagger & Orbell, 2003). Likewise, perceiving greater control over one’s mental health leads to seeking psychotherapy and/or engaging in preventive care to stop mental health problems before they escalate. Control beliefs also influence the types of self-management approaches people use. This is particularly important when cultural beliefs about how to control health threats do not fit with the mental health provider’s beliefs. For example, western medicine’s reliance on medication to treat psychosis, does not fit with cultural use of a spiritual leader in Caribbean cultures and can lead some to reject western mental healthcare (Kirmayer, Groleau, Guzder, Blake & Jarvis, 2003).

Timeline

The final component of illness representations are beliefs about the timeline for the health threat, (i.e., acute, chronic or episodic). In general, viewing a health threat as chronic is associated with worse psychological well-being, worse social and role functioning and vitality, and greater psychological distress (Hagger & Orbell, 2003). Although chronic timeline beliefs are typically associated with worse outcomes, the reverse is sometimes the case. This paradox highlights the complexity of self-management and the importance of determining an individual’s phenomenological illness representation. For example, viewing a long lasting condition as acute can lead to delays in treatment, as one depressed client explained:

Um, ’cause, I mean, it—it didn’t—it did not last. I mean, the days I would be depressed would be because of the, you know, the day itself. And, you know, once the day passed by, you know, the next day is not the same. You know? It’s not a—something that sticks with me like that, you know? (Elwy et al., 2011, p. 7)

APPLYING THE CSM TO PSYCHOTHERAPY

How can the CSM be used to guide our work with clients to improve their self-management? Similar to motivational interviewing, the CSM is not a stand-alone approach for addressing mental health problems. Rather, we propose that the CSM can be used as an adjunct to any theoretical approach to therapy by helping match clients to evidence-based therapies and improve their engagement in the chosen treatment, ultimately improving self-management of their psychosocial problems.

According to the CSM, clients use illness representations to guide their self-management efforts (Leventhal et al., 2011). By extension, to improve client self-management the therapist needs to (1) elicit the client’s illness representation; (2) negotiate a shared or concordant set of illness representations with the client to guide the therapeutic decision making; and (3) help the client explicitly link the illness representation to a self-management plan (McAndrew et al., 2008). Each of these three steps is described in more detail in the following sections.

Elicit the Client’s Illness Representations

Assessment of a client’s illness representations allows the therapist to tailor treatment efforts to the individual and thereby improve adherence and the efficacy of the treatment. It is important that therapists explicitly assess client’s illness representations. The act of eliciting illness representations, itself, is associated with favorable treatment outcomes (Phillips, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 2012; Theunissen, de Ridder, Bensing, & Rutten, 2003). Explicit assessment is also necessary because client’s often do not volunteer their illness representations. Many clients are reluctant or even lie about sensitive components of their illness representations (Blanchard & Farber, 2016), fearing that they will be misunderstood or viewed as naïve (e.g., I am not depressed, I believe there is something wrong with me). Some clients are simply unaware of their illness representations and need the therapist to help make each component explicit. Finally, explicit assessment is needed because therapists’ perceptions of their client’s illness representations are often inaccurate (Phillips, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 2011). This is particularly true for clients who are members of a racial or minority group or who are of low socioeconomic status (Harrington, Haven, Bailey, & Gerald, 2013).

To assess illness representations, therapists may consider the use of a standardized assessment (Davis et al., 2006). The Mental Health Illness Perception Questionnaire- Mental Health (Witteman, Bolks & Hutchemaekers, 2011) measures clients’ perceptions of their psychosocial problems; the Illness Perception Questionnaire – Brief (IPQ-Brief; Broadbent, Petrie, Main, & Weinman, 2006) is a shortened, 9-item scale of illness representations. A semi-structured interview is often more appropriate due to the complex nature of many mental health problems and cultural influences on illness representations that are difficult to capture with quantitative assessment. The interview should probe clients’ perceptions of the identity, consequences, control, cause and timeline of their illness representation, as well as current self-management practices. The DSM-5 provides an example of a semi-structured interview to probe clients’ illness representations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue and Short Explanatory Model Interview are other well-known examples of semi-structured interviews to determine illness representations (Lloyd et al., 1998; Weiss, 1997).

Knowledge of a client’s culture can help therapists inquire about common illness representations. Therapists who are familiar with a particular client population can elicit specific illness beliefs and then address them with accurate knowledge. In the absence of this process, recommending specific therapeutic approaches may be ineffective. For example, many military veterans who have complex post-deployment health concerns (chronic physical and mental health symptoms) are afraid that they are dying, but few veterans tend to express these beliefs without explicitly being asked (Sumathipala et al., 2008). Without inquiring and addressing these concerns, suggesting behavioral therapy to improve quality of life may be viewed as irrelevant and the therapist seen as uninformed.

Assessment of clients’ illness representations should also assess self-management strategies. It is common for clients to make significant changes to their daily life to accommodate the problem, which after years may feel normal to the client and the family. In our example of working with veterans with complex post-deployment health concerns, most of these clients have greatly limited their daily activities and interpersonal relationships in an attempt to manage their pain and anxiety and reduce fatigue. Because this inactivity is not perceived as a choice, the veteran does not always view it as a self-management practice. With further exploration and explanation of illness representations, these clients may be encouraged to increase their daily activities and improve interpersonal relationships as a way to improve quality of life and potentially reduce some of the more debilitating symptoms.

Negotiate a Shared or Concordant Set of Illness Representations

After assessing the client’s illness representations and self-management strategies, the therapist can work with the client to develop concordant, or shared, illness perceptions. Developing concordant illness representations is a natural extension of the working alliance, a key predictor of therapy outcomes (Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, Symonds, & Horvath, 2012), that involves negotiating therapist-client agreement on the goals and tasks of treatment. To negotiate concordant illness representations, the therapist needs to assume that the client’s perspective is valid. There needs to be a balance between the medical model, which assumes that the therapist is correct, and the contextual model, which assumes that all of client’s cultural and illness representations are sacred and therefore not subject to dispute (Quill & Brody, 1996).

The therapist also needs identify the components of the illness representation that are key to improving self-management and for which there has to be a shared understanding with the client. Not all aspects of illness representations are important for every client and not each divergent belief has to be addressed. The therapist must accept divergent beliefs between the client and therapist that are not critical to the treatment, provide psychoeducation for beliefs that are not accurate, and work to develop some shared understanding of beliefs in order to encourage effective self-management. In working with veterans who have complex post-deployment health concerns, for example, we have found that some discordant views on the cause are acceptable (e.g. an exposure concern vs. biopsychosocial model), as long as the therapist acknowledges the veteran’s beliefs and demonstrates a working knowledge of post-deployment health and illness. The therapy process benefits from psychoeducation on the consequences of the health threat (e.g., the symptoms are disabling, but not deadly). Finally, in our experience it is most important that therapist and client have concordant views of control (e.g., “While there is no cure, there are steps we can take to improve your well-being”) and timeline (e.g., you will likely need to manage this for the rest of your life). As self-management leads to improvement in symptoms, concordance about other specific illness beliefs become more likely (e.g., consequence: “This condition is disabling, but I can still have a good life”).

There is some evidence supporting the importance of concordant beliefs in the counseling psychology literature (Phillips, et al., 2011). Claiborn, Ward and Strong (1981) randomized clients to either a treatment that was discordant with their beliefs about their procrastination or one that was concordant. Clients who had concordant beliefs with their therapist reported significantly greater expectations for improvement and in fact were more improved and satisfied with the changes they made. Another study demonstrated the positive impact of concordant beliefs about illness representations on treatment outcomes for patients with bipolar disorder. Scott and Tacchi (2002) explicitly queried clients about their illness representations and worked collaboratively to develop a concordant understanding about bipolar disorder during a seven-session treatment program. The pilot study showed improvement in clients’ medication adherence and beliefs about medication. Notably, at the start of treatment 30% of clients were not adherent, whereas over 80% of clients were adherent by the end of treatment.

Help the Client Explicitly Link Illness Representations to Effective Self-Management

Research on the CSM indicates that people develop illness representations and then use them to make self-management decisions, evaluate the self-management approaches, and use this information as feedback to refine their illness representations and behavior (Hagger & Orbell, 2003). However, this feedback loop is often not explicit for clients. By helping clients understand the feedback loop as therapy progresses and teaching them how to assess various self-management strategies in light of their illness beliefs, therapists can promote lasting benefits after therapy has terminated. A client with depressive symptoms, for example, may be taught to become more active when her mood becomes depressed, or a client who ruminates may learn to use this as a cue to practice mindfulness intentionally. In each of these examples, the client is learning to make self-management purposeful.

As clients try out different self-management approaches, they are continually re-evaluating these approaches and evaluating the value of the therapy in general. For example, in cognitive-behavioral therapy, the client is guided to make a number of changes, such as increasing activities, challenging automatic thoughts, increasing social interactions. Ideally the therapist helps the client determine which management strategies were most effective and which ones were easier to accomplish. Barriers should also be discussed in order to facilitate continued self-management and improvement in mental health. Therapists also need to provide benchmarks against which to progress. For example, some self-management approaches can be expected to lead to immediate improvement, whereas other approaches, particularly those involving insight (Lorig & Holman, 1983), have delayed effects and may not lead to improvement until after therapy has ended.

To illustrate use of the CSM to improve therapy, we present the following hypothetical case example. The case is a compilation of our experience treating many veterans with complex post-deployment physical and mental health concerns.

Case Example

Mr. “Gorden” is a white, 32-year old, married combat veteran with one child, who was referred for therapy by his primary care physician. Mr. Gorden complains of chronic pain, fatigue, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The therapist’s evaluation confirms that Mr. Gorden has PTSD. The therapist also notes significant impairments in daily functioning. Mr. Gorden is not currently working and worries that he and his wife are heading for divorce due to fighting about his inability to help his family.

Integrating the CSM into her assessment and treatment, the therapist continues the assessment by identifying Mr. Gorden’s illness representations, including the identity, cause, consequence, control, and timeline. She also considers how the military culture may be influencing his illness representation. Mr. Gorden reports that his problems began soon after his one year combat deployment to Iraq, where he worked as a gunner. He views his problem as an inability to find employment (identity) due to the poor economy and society’s prejudice against veterans (cause). Mr. Gorden is concerned that he will be unemployed for a long time (timeline) and that nothing in his life will get better until he is able to work (consequence). Mr. Gorden indicates that he needs to get a job before he deals with any of his other problems (control).

Although Mr. Gorden believes that he has PTSD, he does not see it as severe enough to warrant treatment. Rather, he attributes most of his anxiety and marital problems to being unemployed. Finally, he attributes his chronic pain and fatigue to exposure to burn pits (open fires in Iraq). Mr. Gorden admits to being embarrassed about seeking help, stating, “I was a marine, I should be able to power through,” a belief that is common in the military culture. He describes few social supports, stating, “I could ask my family for help, but I don’t want to bother them, so I don’t.” He also says that he only agreed to come for the consultation to appease his primary care physician, and he does not expect to come back.

Using the CSM to guide her conceptualization of Mr. Gorden, the therapist recognizes the importance of validating Mr. Gorden’s beliefs and developing a shared illness representation. The therapist comments on the significance and difficulty of Mr. Gorden’s unemployment. She next provides psychoeducation on PSTD and suggests that it would be easier to find employment if he were first to see a reduction in his anxiety. Her initial goal is to shift Mr. Gorden’s illness representations to match her conceptualization. Mr. Gorden immediately disagrees that his PTSD symptoms are his primary problem, stating that if he had a job, he could control his anxiety.

The therapist and Mr. Gorden agree that he has multiple problems, but disagree on the primary problem. At this point, it would be tempting to assume that Mr. Gorden’s beliefs are maladaptive and then challenge his belief that he does not need help for his PTSD symptoms. This approach, however, is likely to alienate a client who is already reluctant to seek treatment. Further, it is possible that with employment Mr. Gorden will find it easier to address his anxiety and marital problems.

Understanding the importance of having a shared understanding of Mr. Gorden’s problem (identity), the therapist agrees to first address Mr. Gorden’s unemployment by helping him make some decisions about his vocational goals and assess his current job hunting skills. The therapist also recognizes the need to re-evaluate to determine whether unemployment is the primary problem. She negotiates with Mr. Gorden to monitor his PTSD symptoms and relationship quality during treatment, and if they are not noticeably improved, to consider an empirically-supported treatment for PTSD and couples therapy. Further, the therapist addresses Mr. Gorden’s belief that he should be able to “power through” and not show weakness. She provides an alternative interpretation of his cultural value of strength, pointing out that it takes strength to acknowledge symptoms, learn personal limits, and ask for help. Her goal is to work within Mr. Gorden’s cultural views while providing a rationale to continue in treatment.

Importantly, while there remain areas of disagreement (e.g., identity of the primary problem), the therapist has developed concordant illness beliefs around critical components for Mr. Gorden’s treatment, specifically the goal of obtaining meaningful employment and a commitment to monitor his other problems. Moreover, Mr. Gorden now understands and agrees with the expectation to try new self-management approaches (i.e., obtaining employment), evaluate the outcome of each approach, and use the resulting information to guide future goals for treatment. Mr. Gorden leaves the initial session feeling understood and agrees to return for another appointment next week.

Research Recommendations

In this article, we argue for use of the CSM to improve therapy process and outcomes. Below, we highlight a research agenda to further our understanding of using the CSM to improve mental health outcomes. Specifically, research is needed in the following areas: use of the CSM to improve our understanding of (a) how illness representations influence the self-management of mental health problems, (b) how therapists can best address illness representations in psychotherapy; (c) the mechanisms by which addressing illness representations lead to better outcomes, and (d) the relationship between culture and illness representations.

There is initial evidence to suggest that illness representations are associated with self-management and well-being of mental health problems (Elwy et al., 2011), but additional research is needed. Prospective studies should better quantify the effect sizes and temporal order of the relationships. Qualitative studies could illuminate clients’ perspective on how they manage their mental health problems. This work should be conducted with clients in therapy and with individuals who have mental health concerns but are not seeking treatment. Studying both populations will allow us to understand differences in self-management between people willing to seek treatment and those who have not yet sought treatment, thus allowing us to tailor our approaches to self-management in therapy and better engage individuals who have not considered therapy as an option.

Qualitative studies with expert therapists from different orientations and qualitative analyses of their interactions with clients are needed to elucidate how therapists currently address illness representations in therapy. Do these therapists seek to develop concordance? How do they balance evidence-based therapies with an acceptance of the client’s illness representations? When therapists seek to develop concordance, what techniques are most useful? Future research should also examine how to best train therapists to use the CSM.

Qualitative interviews and observational studies can also elucidate the mechanisms through which developing concordant illness representations may improve treatment outcomes. One unexplored mechanism is the relationship between concordance in illness representations and the working alliance, which is a powerful predictor of psychotherapy outcomes. As previously noted, the working alliance is often defined as shared goals and tasks, in addition to the bond. A shared understanding of the illness representations is a similar construct. It is not known if a shared understanding of illness representations explains outcomes over and above the working alliance, or if it contributes directly to the working alliance.

Finally, research has documented that culture is a lens through which individuals develop illness representations (Horne et al., 2004; Jayne & Rankin, 2001; Klonoff & Landrine, 1994; Pachter, 1994; Sobralske, 2006; Yeung, Chang, Gresham Jr, Nierenberg, & Fava, 2004). It is, however, not known how and when culture influences illness representations. Much of the existing research has considered culture as a static variable. Although a pan-cultural approach can improve our understanding of cultural differences, it is limited. At its worst, this approach can lead to stereotypes (e.g., men won’t seek mental health treatment) or inadequate care. Hence, it is particularly important to understand the process of how culture becomes incorporated into illness representations. Why are some clients’ illness representations highly influenced by western medicine and other clients more influenced by cultural beliefs? Additionally, what is the best approach for addressing culturally informed illness representations when clients and therapists come from different cultural backgrounds?

CONCLUSION

For psychotherapy to be effective, it must help clients learn to self-regulate their mental health problems. Leventhal’s Common-Sense Model is a comprehensive model of self-management that can guide therapists in helping clients learn self-management strategies. Using the CSM to understand and improve clients’ self-management of mental health problems is an explicitly client-centered approach that shows promise for enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

Incorporating the CSM into psychotherapy, particularly during the initial and termination phases of treatment, can help therapists develop a treatment plan tailored to clients’ unique, culturally-based perspectives. Working from the perspective of the CSM, therapists can begin to develop a shared understanding of the nature of the client’s health threat from the perspectives of identity, cause, consequence, control, and timeline. With these CSM components in mind, the working alliance is likely to be enhanced through a concordant understanding of the health threat and responsive negotiation of the goals and tasks of treatment.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: This study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service (CDA-052 to L. McAndrew); the NJ War Related Illness and Injury Study Center.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense or the United States government.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. McAndrew, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University at Albany War Related Illness and Injury Study Center, Department of Veterans Affairs New Jersey Healthcare System

J. L. Martin, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University at Albany

M. Friedlander, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University at Albany

K. Shaffer, University at Albany

J. Breland, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System

S. Slotkin, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology, University at Albany

H. Leventhal, Institute of Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, Rutgers University

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch G, Vrouva I, Fearon P. A follow‐up study of characteristics of young people that dropout and continue psychotherapy: Service implications for a clinic in the community. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2009;14:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard M, Farber BA. Lying in psychotherapy: Why and what clients don’t tell their therapist about therapy and their relationship. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2016;29:90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Zhang N, Noll JG. Grief Processing and Deliberate Grief Avoidance: A Prospective Comparison of Bereaved Spouses and Parents in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:86–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborn CD, Ward SR, Strong SR. Effects of congruence between counselor interpretations and client beliefs. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1981;28:101. [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, Weich S, King M. Stigma: the feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184:176–181. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwy AR, Yeh J, Worcester J, Eisen SV. An illness perception model of primary care patients’ help seeking for depression. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:1495–1507. doi: 10.1177/1049732311413781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Symonds D, Horvath AO. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59:10–17. doi: 10.1037/a0025749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune G, Barrowclough C, Lobban F. Illness representations in depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;43:347–364. doi: 10.1348/0144665042388955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Anderson RM. In diabetes care, moving from compliance to adherence is not enough. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:2090–2092. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JS, Elliott TR, Giger JN, Bartolucci AA. Social problem-solving abilities, social support, and adjustment among family caregivers of individuals with a stroke. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2001;46:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:141–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness: How can we use it to understand and respond to our patients’ needs? Rheumatology. 2007;46:904–906. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Glasgow RE, Foster LS. Personal models of diabetes among older adults: Relationship to self-management and other variables. Diabetes Education. 1995;21:300–307. doi: 10.1177/014572179502100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington KF, Haven KM, Bailey WC, Gerald LB. Provider perceptions of parent health literacy and effect on asthma treatment recommendations and instructions. Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 2013;26:69–75. doi: 10.1089/ped.2013.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans MJ. Coping and adaptive outcome in chronic fatigue syndrome: Importance of illness cognitions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998;45:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday J, Wall E, Treasure J, Weinman J. Perceptions of illness in individuals with anorexia nervosa: A comparison with lay men and women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37:50–56. doi: 10.1002/eat.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education & Behavior. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K, Leventhal H, Andrykowski M, Toppmeyer D, Much J, Dermody J, Schwalb M. Using the common sense model to understand perceived cancer risk in individuals testing for BRCA1/2 mutations. Psychooncology. 2005;14:34–48. doi: 10.1002/pon.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Acitelli LK. Accuracy and bias in the perception of the partner in a close relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:439–448. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D, Guzder J, Blake C, Jarvis E. Cultural consultation: A model of mental health service for multicultural societies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48:145–153. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefforge NL, Donohue B, Strada MJ. Improving session attendance in mental health and substance abuse settings: A review of controlled studies. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1994;45:79–122. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common-sense” of chronic illness management. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;41:152–163. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Weinman J, Leventhal EA, Phillips LA. Health psychology: The search for pathways between behavior and health. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:477–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KR, Jacob KS, Patel V, et al. The development of the Short Explanatory Model Interview (SEMI) and its use among primary-care attenders with common mental disorders. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:1231–1237. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobban F, Barrowclough C, Jones S. The impact of beliefs about mental health problems and coping on outcome in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1165–1176. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400203x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Latham GP. New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Johnsen EL, Bunde J, Bellman SB, Rothrock NE, Weinrib A, Lemos K. Gender differences in patients’ attributions for myocardial infarction: Implications for adaptive health behaviors. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12:39–45. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1201_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Lemos C, Rothrock N, Bellman SB, Russell D, Tripp-Reimer T, Gordon E. Gender disparities in common sense models of illness among myocardial infarction victims. Health Psychology. 2004;23:345–353. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Lemos K. From heart attacks to melanoma: Do common sense models of somatization influence symptom interpretation for female victims? Health Psychology. 2002;21:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew L, Schneider SH, Burns E, Leventhal H. Does patient blood glucose monitoring improve diabetes control? A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Education. 2007;33:991–1011. doi: 10.1177/0145721707309807. discussion 1012-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew LM, Mora PA, Quigley KS, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Using the common sense model of self-regulation to understand the relationship between symptom reporting and trait negative affect. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;21:989–994. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew LM, Musumeci-Szabo TJ, Mora PA, Vileikyte L, Burns E, Halm EA, Leventhal H. Using the common sense model to design interventions for the prevention and management of chronic illness threats: From description to process. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:195–204. doi: 10.1348/135910708X295604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley S, Moser DK, Dracup K. Treatment-seeking behavior for acute myocardial infarction symptoms in North America and Australia. Heart & Lung. 2000;29:237–247. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.106940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Leventhal H, Gutmann M. Common-sense models of illness: The example of hypertension. Health Psychology. 1985;4:115–135. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, Jack S. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LA, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Factors associated with the accuracy of physicians’ predictions of patient adherence. Patient Education & Counseling. 2011;85:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Physicians’ communication of the common‐sense self‐regulation model results in greater reported adherence than physicians’ use of interpersonal skills. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17:244–257. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quill TE, Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125:763–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath JF, Hradil AL, Litke DR, Diller L. Clinical applications of problem-solving research in neuropsychological rehabilitation: Addressing the subjective experience of cognitive deficits in outpatients with acquired brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56:320–328. doi: 10.1037/a0025817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel MJ, Seaman S, Roach K, Mullin T, Mahoney KB. Client implementation of therapist recommendations predicted by client perception of fit, difficulty of implementation, and therapist influence. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(3):308–316. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Tacchi MJ. A pilot study of concordance therapy for individuals with bipolar disorders who are non‐adherent with lithium prophylaxis. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4:386–392. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensky T, MacLeod AK, Rigby MF. Causal attributions about common somatic sensations among frequent general practice attenders. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:641–646. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu H, Sedlacek WE. An exploratory study of help-seeking attitudes and coping strategies among college students by race and gender. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2004;37:130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shick Tryon G, Collins Blackwell S, Felleman Hammel E. A meta-analytic examination of client–therapist perspectives of the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research. 2007;17:629–642. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J, Lekwuwa G, Crawford T. Illness beliefs and psychological outcome in people with Parkinson’s disease. Chronic Illness. 2013;9:165–176. doi: 10.1177/1742395313478219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Services. 2001;52:1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont M, Sayer N, Nelson DB. PTSD and treatment adherence: The role of health beliefs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:515–522. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000172474.86877.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Hewege S, Sumathipala K, Prince M, Mann A. Understanding the explanatory model of the patient on their medically unexplained symptoms and its implication on treatment development research: A Sri Lanka study. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen NC, de Ridder DT, Bensing JM, Rutten GE. Manipulation of patient–provider interaction: Discussing illness representations or action plans concerning adherence. Patient Education & Counseling. 2003;51:247–258. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Heimerdinger-Edwards SR, Hammer JH, Hubbard A. “Boys don’t cry”: Examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:368–382. doi: 10.1037/a0023688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, Hackler AH. Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, Heidrich S. African American women’s beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:1589–1601. doi: 10.1177/1049732309350686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC): framework for comparative study of illness. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1997;34:235–263. [Google Scholar]

- Witteman C, Bolks L, Hutschemaekers G. Development of the Illness Perception Questionnaire Mental Health. Journal of Mental Health. 2011;20:115–125. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.507685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeckler N, Kenn K, Kuehl K, Stenzel N, Rief W. Illness perceptions predict exercise capacity and psychological well-being after pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2014;76:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]