Abstract

Health disparities have persisted despite decades of efforts to eliminate them at the national, regional, state and local levels. Policies have been a driving force in creating and exacerbating health disparities, but they can also play a major role in eliminating disparities. Research evidence and input from affected community-level stakeholders are critical components of evidence-based health policy that will advance health equity. The Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center (TCC) for Health Disparities Research at Morehouse School of Medicine consists of five subprojects focused on studying and informing health equity policy related to maternal-child health, mental health, health information technology, diabetes, and leadership/workforce development. This article describes a “health equity lens” as defined, operationalized and applied by the TCC to inform health policy development, implementation, and analysis. Prioritizing health equity in laws and organizational policies provides an upstream foundation for ensuring that the laws are implemented at the midstream and downstream levels to advance health equity.

Keywords: Health Equity, Transdisciplinary, Policy, Health Disparities

Introduction

Despite efforts at the federal, regional, state and local levels, health disparities persist and continue to widen in some populations.1,2 The tangible and intangible costs associated with health disparities are significant, contributing to loss of life, early death, disability and inefficiencies in the system.3 Social, behavioral, economic, and environmental factors are critical drivers of health and disproportionately contribute to poor health outcomes.4 Developing effective strategies to improve health for vulnerable and under-resourced populations challenges researchers to examine how policies, both historic and contemporary, perpetuate health disparities.

This article describes how the Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center (TCC) for Health Disparities Research at Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) operationalized and applied a “health equity lens” to health policy research, development, and implementation. The MSM TCC is an institution-wide research initiative started in 2012 with funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD); the TCC is focused on developing, informing, and evaluating health policies and health policy leadership that advances health equity. Five subprojects focused on diverse health equity issues, including maternal-child health, mental health, health information technology, chronic disease, and leadership development. TCC subproject problem and vision statements are presented in Table 1; and Table 2 provides details on the specific aims of each TCC subproject.

Table 1. Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center for Health Disparities Research: Subproject problem and vision statements.

| Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policya | Health360xa | Health Policy Training | |

| Project focus | Maternal-Child Health and Child Academic Readiness | Mental Health | HIT | Diabetes | Leadership/ Workforce Development |

| Problem | Disparities in educational, physical and mental health outcomes often surface in childhood. Parents who demonstrate positive psychological adjustment are better positioned to support the success of their children. | Behavioral health disparities disproportionately impact underserved populations. Ethnically and culturally diverse populations may receive lower-quality and poorly coordinated mental healthcare compared with White Americans. | Adoption and utilization of HIT has the potential to reduce health disparities, but it is unclear whether and to what extent HIT policies advance and support health equity. | Coupled with care coordination and other support, HIT, including electronic health records and home monitoring tools have been shown to improve adherence to care plans and outcomes for diabetic patients. Use of culturally tailored HIT applications and peer support may be more effective in reducing diabetes disparities. | Racial and ethnic minority and health disparity populations would benefit from better equipped researchers, scientists and policy makers. All populations would benefit by policies and practices that by design prevented disparities in health outcomes among and within all populations. |

| Vision statement | Building parental, institutional and community capacity to promote behaviors and policies that ensure academic readiness, behavioral and physical health, and wellness at the community level. | Providing culturally tailored mental health screening and treatment in locations where racially diverse populations seek primary care, empowering providers and patients to address mental health needs that reduce health disparities. | Identifying gaps in HIT policy that exacerbate existing health disparities and facilitating bilateral communication to engage communities and frontline clinicians and inform policy and practice. | Implementing a technology-based, patient-centered diabetes management program that empowers racial and ethnic minorities, and providers that serve them, to improve diabetes outcomes and reduce the disparities. | Developing health policy leaders who value health equity, understand the root causes of health disparities and have the skills, knowledge and abilities to inform policies that will achieve health equity. |

a. These two subprojects were merged into a single project in the funding proposal. As the project period evolved, the project split into two subprojects in order to better address the specific aims.

Table 2. Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center for Health Disparities Research: Subproject specific aims.

| Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training | |

| Project focus | Maternal-Child Health and Child Academic Readiness | Mental Health | HIT | Diabetes | Leadership/ Workforce Development |

| Specific Aimsa | 1) Use quality parenting as an intervention for addressing childhood physical and mental health inequities; 2) Evaluate the extent to which existing policies in nine southeastern states ensure receipt of early child development resources and effectiveness of programs to support community participation in decision-making related to quality parenting; 3) Implement Smart & Secure Children (SSC) quality parenting intervention in nine southeastern states and demonstrate extent to which this intervention improves child and parent outcomes in vulnerable minority communities. | 1) Design, implement, and evaluate the effectiveness of a culturally centered integrated health care model to address depression and selected co-morbid chronic diseases among underserved ethnically and culturally diverse adults; 2) Assess the impact of mental health insurance mandates and coverage on access to a community-based integrated mental and primary health care model for vulnerable populations. | 1) Identify and analyze existing state and federal HIT policies that impact implementation of HIT in high disparity communities in Georgia and other similarly situated states in the region; 2) Build a collaborative regionwide coalition of community-level health equity advocates to evaluate state and federal policies that positively affect HIT implementation in these communities. | 1) Analyze electronic health record (EHR) patient data and other clinical data to evaluate adherence to evidence-based protocols and disease-based quality measures; use of Physician Quality Reporting System-qualified EHR; Meaningful Use payments; health promotion and disease prevention; and appropriate data collection and reporting; 2) Evaluate effectiveness of a customizable chronic illness and decision support EHR template in improving clinical diabetes outcomes, among high-risk and dual-eligible Medicare beneficiaries. | 1) Identify health policy leaders’ training needs for developing, implementing, and changing policies to address disparities in health; 2) develop a range of health policy leadership training programs in the Satcher Health Leadership Institute (SHLI) at Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) to meet the needs of health professionals, community leaders, and students; 3) evaluate the impact of two SHLI health policy training programs: SHLI Health Policy Leadership Fellowship Program for postdoctoral professionals and the SHLI Community Health Leadership Program for community leaders and students. |

a. Specific aims shown here were developed as part of the funding proposal and have been edited for brevity. Project activities are described in Tables 3-7.

The TCC’s explicit prioritization of health equity within policy research and the broad issues covered necessitated development of a health equity lens that provided a consistent framework and approach, guiding the work and supporting systematic analysis across all subprojects. Varied applications of a health equity lens have been described in the literature.5-7 However, to our knowledge, the application of a health equity lens to analyzing, developing, and informing health-related policies has not been previously described.

Defining a Health Equity Lens Focused on Policy

Definitions of both health disparities and health equity have evolved considerably since the World Health Organization’s original definition as differences in health that “are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust.”8 Soon after the project was initiated in 2012, the TCC adopted the Healthy People 2020 definition of health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage.”9 This definition is broad in scope and recognizes the breadth of population groups experiencing health disparities associated with race, ethnicity, sex, preferred language, disability status, sexual orientation, gender identity, immigration status, socioeconomic status, geography, military service, mental health status and many other factors. This definition goes beyond health care disparities, clearly grounding the fundamental drivers of health disparities in the social determinants of health: the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and play. The TCC also embraced the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) definition of health equity, meaning attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires removing systemic obstacles such as poverty and discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness, poor access to health care, un/underemployment, poor quality education and housing, and unsafe neighborhoods.10

In a policy context, health equity requires creation of the conditions necessary for people to achieve their optimal health potential. This is an important distinction that acknowledges the role (power and control) policymakers have to remove systemic barriers and prioritize health equity. Yet, a disconnect persists when policy solutions fail to: 1) allocate the necessary resources to those at greatest disadvantage; 2) give vulnerable communities decision-making power; and 3) hold policymakers and other decision makers accountable for prioritizing health equity. Achieving health equity requires that all members of society are valued equally, and efforts are focused on advancing policies that create healthy, empowered communities that have the resources to support health and wellness.

With these guiding definitions, the TCC described its application of a health equity lens as strategically, intentionally and holistically examining the impact of an issue, policy or proposed solution on underserved and historically marginalized communities and population subgroups, with the goal of leveraging research findings to inform policy.

Role of Policy to Advance Health Equity

Research shows that health equity is possible through policy action.11,12 Health policies that radically changed our approach to childhood immunizations, breast cancer prevention and treatment, tobacco control, and maternal and child health demonstrate this fact.13,14 Each of these examples of success included targeted approaches that were culturally tailored to the specific groups experiencing health disparities. Targeted policy approaches, particularly those focused on the public health and health care systems, have measurably improved the health of many Americans. There is growing awareness, however, that population health is affected by the complex interaction of contextual factors outside the traditional purviews of public health and health care, such as housing, food security, safe neighborhoods, access to healthy food and economic security.15 Health policy leaders are increasingly moving upstream to embrace health-in-all-policies and develop evidence-based policies across non-health sectors as a strategy for addressing the social determinants of health and achieving health equity.16 To eliminate health disparities and move the needle toward health equity, mechanisms are needed to translate research to inform evidence-based health policy development and evaluation.

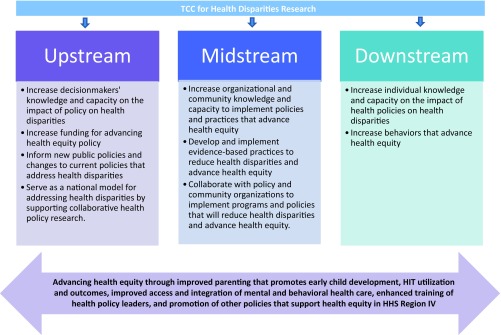

The McKinlay Model for Health Promotion

The McKinlay Model for Health Promotion, initially developed to promote healthy behaviors such as physical activity and nutrition, has been adapted for targeting the elimination of health disparities.17,18 The TCC grounded its work in the McKinlay Model (Figure 1) and applied this model to policy. The model identifies three levels of policy intervention—the individual level (downstream), the community level (midstream) and the societal/decision-makers level (upstream). The downstream level encompasses individuals such as patients, parents, health care providers and community members and focuses on strategies to improve individual-level policies and behaviors. The midstream level, which includes schools, health care organizations and institutions, and public health organizations, focuses on changes within communities, organizations and institutions that reach the population of people functioning within the community or organization’s service area. The upstream level focuses on the public policies made by governing bodies that impact entire populations, including state and national legislatures, school boards, and zoning authorities. These upstream entities set an agenda through laws, regulations, ordinances and budgets, which are often implemented at the midstream and downstream levels. Identification and distinction of these three levels provides a continuum of opportunities to intervene for maximal and targeted impact.

Figure 1. Application of the McKinlay Model for health promotion to policy by the TCC.

Applying a Health Equity Lens to Policy

The TCC’s health equity lens was intended to clearly frame health in the context of social, behavioral, economic, and environmental determinants, and to work collaboratively with community stakeholders to increase knowledge and engagement with policy processes. The TCC’s application of a health equity lens consisted of five steps: 1) identify the health equity issue and affected population; 2) analyze the relevant policy impacts and opportunities for policy improvement; 3) develop policy-relevant research strategies in partnership with community stakeholders; 4) measure and evaluate policy outcomes and impacts on heath disparities; and 5) disseminate findings to relevant audiences and stakeholders, including policy makers, communities, public health officials, and health care providers. Each construct is described below in Tables 3-7, providing an overview of how the five TCC subprojects applied a health equity lens.

Identify Health Equity Issue and Affected Population (Table 3)

Table 3. Applying a health equity lens to policy across five subprojects of the TCC: issue identification.

| Identify health equity issue and affected population | Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training |

| Health equity issue | Prevalence of childhood obesity and threats to positive childhood mental health | Prevalence of depression and the delivery of low quality mental health services | Potential for HIT to reduce existing disparities, create new disparities, or widen disparities in health outcomes | Prevalence and severity of diabetes, obesity and other chronic conditions | Prevalence of policies and practices that create, sustain, or widen health disparities compared with policies and practices that create or advance health equity |

| Health policy issue | Parents and policymakers have the potential to impact childhood obesity, mental health disparities and academic success through supportive, culturally tailored quality parenting programs | Health care clinics and system policies should support culturally centered models of integrated care, guiding staff training and education, clinical service provision, and use of health information technology | HIT policies may be exacerbating existing disparities; community stakeholders including primary care physicians, public health professionals are often not engaged in the policymaking process | Diabetic patients are empowered to manage their health with support programs including culturally tailored peer support and HIT | Health policy training programs that integrate health equity develop leaders prepared to advance health equity |

| Affected population | African Americans living in under-resourced communities as compared with the general population | Racial/ethnic minority groups, individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) and other vulnerable populations with known mental health disparities | Underserved and vulnerable populations, including racial/ethnic minorities, LGBTQ, people with disabilities, rural populations, Medicaid recipients and the health care providers serving these populations | Racial and ethnic minorities in the South with diabetes, obesity and other chronic conditions | Health policy leaders, health professionals enrolled in the SHLI Health Policy Leadership Fellowship and the Community Health Leadership Program and the organizations/communities they serve |

Identifying and characterizing the specific areas of health inequity are critical first steps in developing the research, outreach and dissemination strategies necessary to mitigate the issue. Because health disparities are multi-faceted, intersectional, and affect many populations, it is imperative to develop targeted approaches. Within the TCC, evidence-based approaches including literature reviews, expert panels and pilot studies were used to identify key health equity issues and affected populations and assess the existing evidence. Two subprojects were able to leverage their existing data to refocus and enhance their programs. Two subprojects used pilot data to inform their work. A fourth project relied on existing health disparities research and consultation with an advisory board of national experts to guide its issue identification and research strategies. All subprojects focused on engaging and empowering the community, as defined specifically by each subproject, in their research development, evaluation and dissemination processes.

Analyze Relevant Policy Impacts and Opportunities for Policy Improvement (Table 4)

Table 4. Applying a health equity lens to policy across five subprojects of the TCC: policy analysis and identify opportunities for informing policy.

| Analyze relevant policy impacts and opportunities for policy improvement | Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training |

| McKinlay Model Level of Intervention | Downstream, Midstream, Upstream | Downstream, Midstream, Upstream | Downstream, Midstream, Upstream | Downstream, Midstream | Downstream, Midstream, Upstream |

| Level of Policy Research/Intervention | Evaluate impact of SSC quality parenting program on childhood obesity and mental health (downstream); Assess impact of state and local policies on childhood obesity and mental health (midstream & upstream); Inform current and proposed policies to enhance provision of equitable early child development programs (upstream) | Activate patients to seek mental health care through data and shared decision-making (downstream); Inform provider and practice-level policies that ensure integration between primary care and behavioral health providers, sharing clinical information and team-based coordination (downstream & midstream); Evaluate impact of culturally centered integrated care model on system/clinic policies related to quality, safety, efficiency and disparity reduction (midstream); Analyze population-level characteristics of Medicaid patients with depression (upstream) | Assess state and federal laws for impact on health equity (upstream); Analyze implementation of HIT policies by health care providers and systems (midstream); Inform, engage and activate health care providers and communities to inform HIT policies regarding impact on health equity (midstream & downstream) | Assess provider, practice and system barriers and facilitators to implementing a technology-based chronic care management program in an accountable care organization (downstream & midstream); Evaluate effectiveness of a technology-based chronic care management program on diabetes outcomes and patient management (downstream) | Examine the workforce and training needs for health policy leaders focused on health equity (midstream & upstream); Evaluate training outcomes for a health policy fellowship program focused on health equity (downstream) |

Systematic evaluation of the policy landscape is critical for identifying and contextualizing factors across the entire policy cycle that exacerbate or fail to eliminate health disparities. Policy evaluation establishes the evidence base for improving policy and involves studying the policy content, implementation and impact.19 TCC research projects and collaborative partners employed an iterative process to critically analyze the policy environments associated with their respective health equity areas. This iterative process drew upon multiple research methodologies: review and secondary data analysis of epidemiological data; literature reviews; environmental scans; qualitative research with care providers, administrators, patients and community members; and community needs assessments. It also required the use of policy research methodologies: governmental policy scans and gap analyses; legal epidemiology; reviews of institutional and organizational policies and bylaws; and evaluation of system policies and standard operating procedures.

The TCC’s policy evaluation approach included identification of policy dilemmas where: 1) no policies existed to specifically address the health disparities; 2) policies were adopted but poorly or inequitably implemented; 3) implementation of existing policies resulted in deleterious consequences for vulnerable populations; or 4) existing policies were not sufficiently evaluated to determine differential impacts among vulnerable populations. Once the policy dilemma was fully assessed, identification of strategic policy opportunities involved equity-focused discovery and collaborative efforts that informed the development of new policies, engaged key policy stakeholders, informed policy agenda setting efforts, and guided evaluation of the policies among populations with established health disparities. The McKinlay Model for Health Promotion was utilized across the TCC research portfolio to describe and organize both policy dilemmas that required deeper analysis, and opportunities to inform policy change at three levels of influence: downstream, midstream, and upstream.

Develop Policy-relevant Research Strategies in Partnership with Community Stakeholders (Table 5)

Table 5. Applying a health equity lens to policy across five subprojects of the TCC: developing policy-relevant research strategies.

| Develop policy-relevant research strategies in partnership with community stakeholders | Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training |

| Research/ Intervention Strategy | Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches empower and activate parents to deepen their understanding of quality parenting strategies and impact on childhood obesity and mental health. CBPR changed the current paradigm of external policy advocacy to one in which historically disenfranchised communities provide leadership in policy development and advocacy. | Mixed methods research, including focus groups, clinical intervention and secondary data analysis, and a CBPR approach inform a patient-centered and iterative research strategy to implement a culturally centered integration treatment intervention in primary care community health clinic. | Mixed methods research, including content analysis, secondary data analysis, key informant interviews and gap analysis identified policy barriers and facilitators to use of HIT to advance health equity. Guidance from the literature, key informants and a national advisory board resulted in research questions related to priority areas. | Mixed methods research, including focus groups, a clinical intervention and a CBPR approach were used to inform a patient-centered and iterative research strategy to implement Heath 360x, a culturally tailored diabetes support program and technology intervention in the Morehouse Healthcare ACO and community practices. | Conduct a health policy leaders’ needs assessment survey informed by an advisory board composed of institutional and community-based stakeholders and experts. This evaluation of fellowship outcomes was unique in its focus on career trajectories, subsequent leadership roles, engagement in and impact on health policy and health equity-relevant work. |

| Community Engagement | Community cores are developed in each SSC site to serve as points-of-contact for establishing local TCCs and building community infrastructure and capacity for the implementation of SSC to address childhood obesity, mental health, and school readiness by promoting quality parenting. | Patients, providers and practice administrators inform the intervention design and strategy through key informant interviews and focus groups. | A coalition of primary care providers and clinics, policymakers and community organizations were leveraged to bilaterally communicate the impact of existing HIT policies and potential impacts of proposed state and federal HIT policies. | Patients, community leaders, providers and practice administrators inform the intervention design and strategy through key informant interviews and focus groups. | Collaborate with organizational partners, health policy leaders and health policy fellows to identify health equity issues and develop projects and resources to inform policies that advance health equity. |

Key features of the TCC’s application of a health equity lens were inclusivity of affected stakeholders, use of innovative approaches to conduct health policy-relevant research and multidisciplinary research teams. This required the TCC to understand how individual and community health were both a product and predictor of community capacity so that community-level engagement in solutions to achieve health equity were incentivized. Academic and community partners each contributed significantly to research design and implementation.

The TCC research activities were strategically designed to: 1) lead efforts to educate priority populations about health equity issues and empower these communities to engage in the policymaking process; and 2) build strategic partnerships and collaborations that address health equity issues to develop strength in numbers and a unified voice to inform potential solutions. Opportunities for cross-sector collaboration were emphasized and strategically developed to inform and develop health-related policies that improved priority population health across multiple health outcomes. The TCC intentionally worked to integrate research findings into policy development and implementation to evaluate impact and effectiveness of health policies and build community capacity for sustaining the health equity effort.

Measure & Evaluate Policy Outcomes and Impacts on Health Disparities (Table 6)

Table 6. Applying a health equity lens to policy across five subprojects of the TCC: measurement and evaluation.

| Measure and evaluate policy outcomes on health disparities | Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health Information Technology (HIT) Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training |

| Downstream outcomes | Changes in parent knowledge about healthier lifestyles; Changes in parent motivation to change their own and their family’s health behaviors; Changes in parent knowledge and desire to advocate for improved policies relating to healthy child development. | Patient outcomes after exposure to culturally tailored intervention; perceived care-seeking behaviors of targeted patients; Knowledge of integrated care models; Awareness and attitudes related to culturally tailored integrated care models. | Types & characteristics of providers adopting EHR; characteristics of Medicaid enrollees receiving telemedicine services. | # of patients enrolled; Effectiveness of intervention in improving diabetes management; Provider-level workflow issues. | # of and characteristics of fellows who completed program; # of fellows with full-time employment by sector; Promotions/leadership roles since fellowship completion; Importance of/role of health disparities and health equity in current position. |

| Midstream outcomes | Extent to which existing local policies ensure receipt of appropriate early child development resources and program effectiveness in supporting community participation. | Perceived barriers/ facilitators to incorporating culturally tailored integrated care models into clinical practice. | System and community-level barriers and facilitators to adoption and implementation of HIT in underserved communities. | # of practices enrolled and connected to data warehouse; Amount of data flowing; System-level barriers and facilitators to integration. | Service on local, state, and national health advisory boards; Promotions/leadership roles since fellowship completion; Develop, implement or change public policy that address health disparities. |

| Upstream outcomes | Extent to which existing state policies ensure receipt of appropriate early child development resources; Post-implementation demonstration of improvement in mental health, school readiness, reduction in child neglect and obesity among vulnerable children in minority communities. | Secondary data analysis of Medicaid claims including patients similar to study sample (racial/ethnic minority, Depression diagnosis, 1+ chronic condition). | Categories of demographic data included in federal EHR technology programs; Inclusion of health equity language in proposed, final policies; Health equity implications of proposed/ final policies. | N/A | Service on local, state, and national health advisory boards; Promotions/leadership roles since fellowship completion; Develop, implement or change public policy that address health disparities. |

Measuring and providing sufficient evidence of the effectiveness of interventions is one of many barriers to implementing actionable health policies.20 This is especially true when evaluating complex systems, issues and interventions leading to health disparities. Therefore, it was critical to determine how policy outcomes and impacts would be measured and evaluated early in the planning process. The TCC implemented a participatory approach to develop evaluation plans that would effectively measure not just the presence or change to a policy, but how the TCC’s multi-level policy interventions impacted health disparities. Stakeholders were engaged and expert input from community, research, and health policy leaders were used to determine TCC outcome measures.

Project-specific logic models were developed collaboratively to align project activities with expected policy impacts. Quarterly plans and reports were submitted to continuously track the key strategies, outputs and outcomes associated with projected impacts. Evaluation of the TCC subprojects also focused on creating or revising quantitative and qualitative assessment measures associated with the policy impact of TCC projects. Assessment tools were identified, revised, or developed to include downstream, midstream, and upstream policy outcomes in the TCC McKinlay model; Table 6 provides specific examples. Some of the overarching downstream policy outcomes across the TCC and its subprojects included: changes in individual knowledge and capacity on the impact of health policies on health disparities; and changes in individual behaviors that advance health equity. Overarching midstream policy outcomes included: changes in organizational and community knowledge; changes in capacity to implement policies and practices; development and implementation of evidence-based practices to reduce health disparities and collaborations to implement programs; and introduction/adoption of policies that would reduce health disparities and advance health equity. Overarching upstream policy outcomes were: change in knowledge and capacity on the impact of policy on health disparities by decision makers and government officials; change in funding for advancing health equity policy; and change in public and organizational policies that address health disparities.

Disseminate Findings to Relevant Audiences and Stakeholders (Table 7)

Table 7. Applying a health equity lens to policy across five subprojects of the TCC – strategic dissemination.

| Disseminate findings to relevant audiences & stakeholders | Collaborative Action for Child Equity (CACE) | Project THRIVE | Health IT Policy | Health360x | Health Policy Training |

| Academic dissemination | Publication in peer-reviewed journals; Presentation at national conferences | Publication in peer-reviewed journals; Presentation at national, state conferences | Publication in peer-reviewed journals; Presentation at national, state conferences | Publication in peer-reviewed journals; Presentation at national, state conferences | Publication in peer-reviewed journals; Presentation at national, state and local conferences |

| Community dissemination | Development of policy briefs for targeted audiences; Community/coalition meetings & presentations | Development of policy briefs, infographic targeted for lay audience, trivia game focused on cultural competency and integrated care; Community education | Continuous cycle of bilateral communication with health care providers, community organizations and policymakers to inform existing and developing policies using social media, webinars, public comments | Community-level presentations and forums | Inclusion of outcome data in marketing/promotion materials |

| Policy dissemination | Development of policy briefs for targeted audiences; Webinar with partners | Development of policy briefs, infographic targeted for lay audience, trivia game focused on cultural competency and integrated care | Continuous cycle of bilateral communication with health care providers, community organizations and policymakers to inform existing and developing policies using social media, webinars, public comments, advisory board meetings | N/A | Inclusion of outcome data in marketing/ promotion materials |

Broad dissemination of research evidence and outcomes is critical to policy development and implementation that address health disparities. Gaps between policy, research and practice are well understood and the evolution of dissemination and implementation science seeks to bridge across these silos. One foundational challenge is the incentive by funding agencies and academic institutions to publish research findings in scientific journals, which are not accessible to many individuals, communities, health care providers and policymakers. Broad methods of dissemination including social media, webinars and blogs are promising to get scientific evidence into the hands of those most affected.

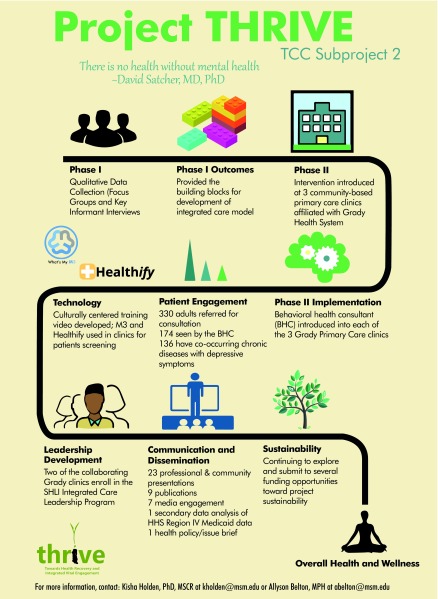

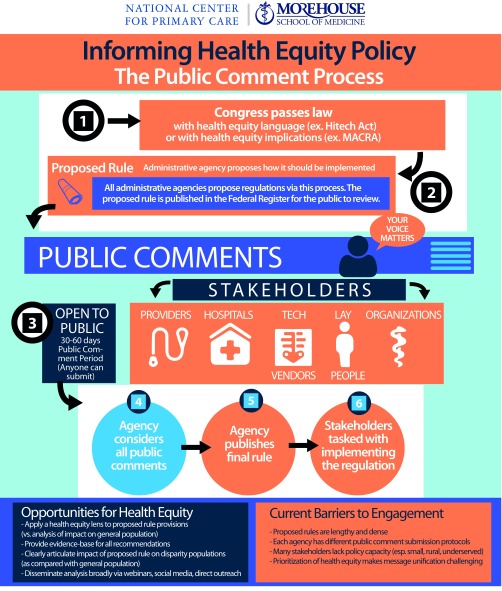

The TCC prioritized broad dissemination of its research findings through an established dissemination and implementation core, which worked directly with the subprojects to ensure strategic and intentional early planning for broad dissemination. All subprojects published findings in scientific journals, but dissemination did not stop there.21-24 Social media (eg, Twitter pages/handles: @MSMTCCPolicy, @TCC_HITPolicy, @Kennedy-Satcher, @SatcherHP) , webinars, blogs, infographics, and policy briefs were developed to inform downstream, midstream and upstream policy.25-27 As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the TCC developed infographics to help communicate complex findings from the TCC subprojects to multiple audiences. In addition, the Health Equity Leadership and Exchange Network (http://www.nationalcollaborative.org/our-programs/health-equity-leadership-exchange-network-helen/), a collaborative effort between the National REACH Coalition, Morehouse School of Medicine, and the National Collaborative for Health Equity, was established to share research findings and policy opportunities.

Figure 2. TCC Project THRIVE infographic.

Figure 3. TCC HIT policy infographic.

Expanding the Health Equity Lens

Although challenges remain relative to the advancement of health equity in all policies, it nonetheless remains a national priority, as evidenced by its inclusion in federal, state, and local governmental policies.28 Alignment of public health, social services and health care finance and delivery is challenging and needed to accomplish sustainable improvement. As demonstrated by the TCC’s work, policies play a major role in the achievement of health equity and therefore should be included in more research and dissemination strategies. Applying a policy-focused health equity lens in research can empower investigators to recognize and measure the impact of policy and then leverage their research to inform policy. Researchers have the tools and platform to ensure appropriate and meaningful data are collected and available for research; there are many opportunities to push academia to align promotion and funding incentives with health equity and broad dissemination of research findings.

The TCC’s inclusion of community partners highlights the value of engaging, informing and empowering community members to understand the role of policy and mechanisms for informing policy improvements. Community organizers and non-profit organizations are the experts on issues relevant to their communities and excel at activating their stakeholders and academic institutions and researchers. Partnering with academic institutions creates a bridge for the evidence to flow into communities and to identify the role of policy.

In order to achieve health equity, the current policy landscape and incentive structures require significant changes. The TCC found that language and context are important and that including health equity language in laws and organizational policies provides an upstream foundation for ensuring the laws are implemented at the midstream and downstream levels to advance health equity.

Conclusion

Achieving health equity is not merely a moral imperative but benefits all communities. The financial and social costs of health disparities are significant and will continue to grow without application of a health equity lens to research, practice and policy. The TCC for Health Disparities Research at Morehouse School of Medicine applied a health equity lens by employing these five steps: 1) identify the health equity issue and affected population; 2) analyze the relevant policy impacts and opportunities for policy improvement; 3) develop policy-relevant research strategies in partnership with community stakeholders; 4) measure and evaluate policy outcomes and impacts on heath disparities; and 5) disseminate findings to relevant audiences and stakeholders, including policy makers, communities, public health officials, and healthcare providers. This strategy leveraged transdisciplinary research teams and empowered community members to engage in the research and policy processes. The TCC’s research resulted in important findings for policy development and implementation that advance health equity.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD008173. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the TCC subproject principle investigators, research and administrative staff and the TCC Research Core for their contributions to this manuscript.

References

- 1. Singh GK, Kogan MD, Slifkin RT. Widening disparities in infant mortality and life expectancy between Appalachia and the rest of the United States, 1990-2013. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1423-1432. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1571PMID:28784735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bilal U, Diez-Roux AV. Troubling trends in health disparities. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1557-1558. 10.1056/NEJMc1800328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the economic burden of racial health inequalities in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(2):231-238. 10.2190/HS.41.2.c 10.2190/HS.41.2.c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S4)(suppl 4):S517-S519. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, et al. . Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):56-64. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barsanti S, Nuti S. The equity lens in the health care performance evaluation system. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29(3):e233-e246. 10.1002/hpm.2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keippel AE, Henderson MA, Golbeck AL, et al. . Healthy by design: using a gender focus to influence complete streets policy. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(suppl 1):S22-S28. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity in health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22:429–445. (First published with the same title from: Copenhagen: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, 1990 (EUR/ICP/RPD 414).) 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Phase I Report: Recommendations for the Framework and Format of Healthy People 2020. Section IV: Advisory Committee findings and recommendations. Last accessed December 19, 2018 from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/PhaseI_0.pdf.

- 10. Braveman P. A new definition of health equity to guide future efforts and measure progress. Health Affairs Blog. June 22, 2017. Last accessed May 10, 2019 from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170622.060710/full/

- 11. Rust G, Zhang S, Malhotra K, et al. . Paths to health equity: local area variation in progress toward eliminating breast cancer mortality disparities, 1990-2009. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2765-2774. 10.1002/cncr.29405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dawes DE. 150 Years of Obamacare. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutchins SS, Jiles R, Bernier R. Elimination of measles and of disparities in measles childhood vaccine coverage among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(s1)(suppl 1):S146-S152. 10.1086/379651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Gitchell J. The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: a tobacco control scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(4):338-353. 10.1097/00124784-200407000-00011 10.1097/00124784-200407000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Artiga S, Hinton E.. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. 2018. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Last accessed December 18, 2018 from https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

- 16. Rajotte BR, Ross CL, Ekechi CO, Cadet VN Health in All Policies: addressing the legal and policy foundations of Health Impact Assessment. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39(1_suppl) (suppl 1):27-29. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00560.x PMID:21309891 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. McKinlay JB. Preparation for aging. In: Heikkinen E, Kuusinen J, Ruppila I, eds. The New Public Health Approach to Improving Physical Activity and Autonomy in Older Populations. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995:87-103. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Satcher D. Ethnic disparities in health: the public’s role in working for equality. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e405. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Step by Step—Evaluating Violence and Injury Prevention Policies, Brief 1: Overview of Policy Evaluation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last accessed December 18, 2018 from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/about/evaluation.html.

- 20. Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576-1583. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bolar CL, Hernandez N, Akintobi TH, et al. . Context matters: A community-based study of urban minority parents’ views on child health. J Ga Public Health Assoc. 2016;5(3):212-219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wrenn G, Kasiah F, Belton A, et al. . Patient and practitioner perspectives on culturally centered integrated care to address health disparities in primary care. Perm J. 2017;21:16-018. 10.7812/TPP/16-018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Douglas MD, Dawes DE, Holden KB, Mack D. Missed policy opportunities to advance health equity by recording demographic data in electronic health records. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(S3)(suppl 3):S380-S388. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heiman HJ, Smith LL, McKool M, Mitchell DN, Roth Bayer C. Health policy Training: a review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;13(1):h13010020. 10.3390/ijerph13010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douglas M. Are We There Yet? Policy Prescriptions Blog Post, Dec. 14, 2015. Last accessed December 18, 2018 from http://www.policyprescriptions.org/are-we-there-yet/.

- 26. Heiman H, Artiga S.. Issue Brief. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. Published by the Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2015. (Predecessor to Ref 14, published in 2018).

- 27. Belton A. Stronger than Kryptonite: How Black Superwomen Remain Resilient. Thrive Global Blog Post, June 28, 2018. Last accessed December 18, 2018 from https://thriveglobal.com/stories/stronger-than-kryptonite/.

- 28. Berenson J, Li Y, Lynch J, Pagán JA. Identifying policy levers and opportunities for action across states to achieve health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1048-1056. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]