Abstract

Objective

To create a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm to identify transgender patients in electronic health records.

Design

We developed an NLP algorithm to identify patients (keyword + billing codes). Patients were manually reviewed, and their health care services categorized by billing code.

Setting

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Participants

234 adult and pediatric transgender patients.

Main Outcome Measures

Number of transgender patients correctly identified and categorization of health services utilized.

Results

We identified 234 transgender patients of whom 50% had a diagnosed mental health condition, 14% were living with HIV, and 7% had diabetes. Largely driven by hormone use, nearly half of patients attended the Endocrinology/Diabetes/Metabolism clinic. Many patients also attended the Psychiatry, HIV, and/or Obstetrics/Gynecology clinics. The false positive rate of our algorithm was 3%.

Conclusions

Our novel algorithm correctly identified transgender patients and provided important insights into health care utilization among this marginalized population.

Keywords: Transgender, Natural Language Processing, Electronic Health Records, Utilization

Introduction

Transgender Health

Transgender people, also called gender minorities, continue to be underserved and marginalized as a population due to bias and discrimination. As a result, transgender people experience health disparities, including disproportionally high rates of HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and mental health conditions as well as barriers to accessing health care.1 Even when transgender people are able to access care, they report high rates of discrimination and bias within the health care system.1 Often, transition-related health care —such as gender affirming surgery and hormone therapy—is excluded from coverage by commercial payers and government insurance programs.1 In addition to being transgender, transgender people of color, particularly transfeminine people, often face barriers when entering the health care system due to structural racism.2 For example, rates of HIV infection among transgender women are higher than rates observed among cisgender (Table 1 provides definitions for this and other terms used throughout this article) women, cisgender men, and transgender men. Transgender men, who are understudied in HIV research, had a higher frequency of a positive HIV test than cisgender women though not cisgender men or transgender women.3 Black or African American individuals, including transgender women and men, are at a disproportionately higher risk for HIV than individuals of other races/ethnicities.3,4 A meta-analysis found that more than half of Black or African American transgender women in the United States are living with HIV.5 Another study found that Black/African American or Hispanic or Latino transgender women are more likely to be living with HIV than transgender women of other races/ethnicities.3 In 2016, the director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities issued a statement declaring gender minorities a “health disparity population for research purposes,”6 and in 2011, the Institute of Medicine released a report calling for an increase in research on the intersections of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health and the health of people of color.7 Despite these calls, research documenting health outcomes of transgender populations remains limited due to the lack of data collection including transgender people, especially transgender people of color.

Table 1. Key terms and current definitions of gender identity and related concepts.

| Gender identity | A person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or a male; a girl, a woman, or a female, or an alternative gender (eg, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, gender neutral) that may or may not correspond to a person’s sex assigned at birth or to a person’s primary or secondary sex characteristics8 |

| Sex assigned at birth | For the majority of births, a relative, midwife, doula, nurse or physician inspects the genitalia of the infant upon delivery and assigns the female sex or male sex based on this observation. Typically, sex is treated as binary, but exceptions may occur in some medical and/or cultural contexts (eg, an infant with ambiguous genitalia). 9 |

| Transgender | An adjective to describe a diverse group of individuals who self-identify as a gender minority or whose gender identity is different (in varying degrees) from the sex assigned to them at birth 10 |

| Gender minority | A broader term to describe transgender and other people whose gender identity, expression, or reproductive development varies from traditional, cultural, or societal norms11 |

| Cisgender | Of, relating to, or being a person whose gender identity corresponds with the sex the person was assigned at birth12 |

| Transsexual | Adjective (often applied by the medical profession) to describe individuals who seek to change or who have changed their primary and/or secondary sex characteristics through femininizing or masculinizing medical interventions (hormones and/or surgery), typically accompanied by a permanent change in gender role10 |

| Non-binary | Adjective and umbrella term to describe a person’s gender that can be neither male nor female, both male and female at the same time, as different genders at different times, or as no gender at all13 |

| Genderqueer | An identity that falls under the non-binary umbrella but has different meanings to different people. Typically used by a person who does not subscribe to conventional gender definitions. |

| Transgender men (FTM) | Adjective to describe individuals assigned female at birth who are changing or who have changed their body and/or gender role from birth-assigned female to a more masculine body or role10 |

| Transgender women (MTF) | Adjective to describe individuals assigned male at birth who are changing or who have changed their body and/or gender role from birth-assigned male to a more feminine body or role10 |

| Transmasculine | An inclusive umbrella term that refers to transgender people assigned a female sex at birth and who identify on the masculine spectrum, including as a man of transgender experience, transgender man, transman, female-to-male (FTM), genderqueer, or another masculine identity14 |

| Transfeminine | An inclusive umbrella term that refers to transgender people assigned a male sex at birth and who identify on the feminine spectrum, including as a woman of transgender experience, transgender woman, transwoman, male-to-female (MTF), genderqueer, or another feminine identity15 |

| Gender identity disorder | Formal diagnosis set forth by the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Rev (DSM IV-TR). Gender identity disorder is characterized by a strong and persistent cross-gender identification and a persistent discomfort with one’s sex or sense of inappropriateness in the gender role of that sex, causing clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.10 This diagnosis is considered outdated and has been replaced by gender dysphoria. |

| Gender Dysphoria | Diagnosis given to indicate distress resulting from a difference between a person’s gender identity and the person’s sex assigned at birth and the associated gender role and/or primary and secondary sex characteristics.9 |

Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

Despite recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) for collecting gender identity information as a standard practice in EHRs,7 most EHR systems do not store data about gender identity or sexual orientation in a structured fashion. While the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) does mandate collection of gender identity demographic fields in EHRs certified under the Meaningful Use of Electronic Health Records program, the collection of gender identity information is not nationally mandated. Additionally, there is no standardized way to collect gender identity information in EHR systems.16 Transgender patients may be reluctant to share their transgender identity with health care providers due to the fear of discrimination.7,16 This fear, combined with the obstacles many transgender people face in obtaining health care, has made the collection of epidemiologic data about transgender patient health services utilization challenging.17 Even though EHR software upgrades to allow for collection of gender identity data are increasingly common, health care providers still rarely utilize these tools.18 Health care systems may therefore underestimate the number of transgender patients in their care due to the lack of documentation of transgender status and gender identity in their EHRs as well as the exclusion of transgender participants in clinical research.

Previous Work to Identify Transgender Patients in Electronic Health Records

To prepare for our research, we conducted a systemic review of the evidence related to the identification of transgender patients in electronic health records. This search yielded only 21 published articles that described identification of transgender patients in EHRs. Of the 21 articles, 19 used ICD codes, one used ICD codes and NLP, and one used pharmacy records. However, only one published statistics documenting the performance of their algorithm. Some articles sought not only to describe the identification of transgender patient cohorts in EHR systems, but also to assess the health outcomes and clinical utilization patterns among transgender patient populations. Several previously published studies have been from authors within the same research institutions using the same EHR datasets, which, while important, has resulted in a relatively limited number of unique patients included in prior research. Notably, 11 of the articles reported the algorithmic identification of cohorts of transgender veterans within United States Veterans Administration (VA) EHR data. These studies found that, compared with cisgender veteran populations, transgender veterans were more likely to be diagnosed as living with mental (eg, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) and physical (eg, diabetes, HIV, cardiovascular disease) health conditions.19 In alignment with the exacerbation of poor health outcomes previously documented among non-White transgender populations, these studies also found that Black transgender veterans were more likely to be homeless or incarcerated and less likely to be married compared with White transgender veterans.20

Study Objective

The overall objective of this study was to create a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm to identify transgender patients in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center electronic health care record. The goal of creating the algorithm was to develop a comprehensive, evidence-based summary of transgender health care utilization and quality. This article builds on previous research and describes the outcomes of using an NLP algorithm to identify transgender patients in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s EHR.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, we undertook a quantitative study to identify transgender patients in the EHR system. To accomplish this, we developed an algorithm to systematically identify transgender patients within the Vanderbilt University Medical System’s homegrown EHR system, StarPanel. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. A waiver of informed consent was obtained.

A combination of keywords (“gender dysphoria”, “genderqueer”, “MTF”, “FTM”, “transgender”, “transsexual”) and ICD 9 administrative billing codes (302.51 (Trans-sexualism with asexual history), 302.52 (Trans-sexualism with homosexual history), 302.53 (Trans-sexualism with heterosexual history), 302.6 (gender identity disorder in children), 302.85 (gender identity disorder in adolescents or adults)) was used to identify transgender patients in the EHR. Keywords and billing codes were selected based on previous literature,17,21,22 our own expertise, and ICD billing practices at the time the data were abstracted. To be classified as transgender, patient medical records needed to include at least one keyword and one billing code. We then manually reviewed each patient flagged by the algorithm and created a database of patient records, noting patients who had been flagged inappropriately. Clinical notes and encounters for all patients seen at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from 2001 to 2016 were searched for these keywords and diagnoses codes. No patient-entered data (ie, patient portal messages) were included in the search.

We conducted manual reviews of patient EHR records to confirm the presence of algorithm keywords. Using a form in REDCap,23 a secure web-based survey tool, we abstracted the patient’s sex at birth, gender identity, date of birth, number of entries and dates of entries in the medical record, whether the patient was deceased, the clinics/departments the patient attended, and whether there was a record of an administrative change of patient gender marker or name.

Additionally, we utilized standard database query tools to query our health system’s electronic patient data warehouse to determine medication information, age distribution, and co-morbidities of the transgender patient cohort identified by our algorithm.

Statistics

Among the transgender patients identified by our search, we calculated summary descriptive statistics for our cohort using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA), including demographic distribution and frequency of an administrative gender marker change. We also identified the most frequent diagnosis and medications prescribed. Using our NLP search strategy, we calculated the false positive rate for our final algorithm. A false positive was defined as a patient flagged as being transgender who upon review of the chart was confirmed to be cisgender. A false negative was defined as a transgender patient who was not flagged by our algorithm. Because of the nature of our study, we were unable to calculate a false negative rate.

Results

In total, the algorithm identified 234 patients who had at least one algorithm keyword and one billing code. This represented <.1% of all patients cared for at Vanderbilt. Patient demographics are shown in Table 2. The false positive rate of the final algorithm was 3%.

Table 2. Demographics of transgender cohort – n (%).

| Race | |

| White | 162 (70%) |

| Black | 39 (17%) |

| Other | 13 (6%) |

| Unknown | 41 (18%) |

| Gender identity | |

| MTF | 23 (10%) |

| FTM | 18 (8%) |

| Genderqueer | 0 (0%) |

| Transgender unspecified | 193 (82%) |

| Gender marker changed in EHR | |

| Yes | 42 (18%) |

| No | 192 (82%) |

MTF, transgender women; FTM, transgender men.

Of the cohort of transgender patients identified by the algorithm, more than 50% had a diagnosed mental health condition, 14% were living with HIV, and 7% had diabetes. Largely driven by hormone use, nearly half of patients had attended the Endocrinology/Diabetes/Metabolism clinic. Other top clinics attended included Internal Medicine, Trauma, Comprehensive Care Clinic (a clinic for people living with HIV), Psychiatry, and Obstetrics/Gynecology. Overall, 44% of transgender patients were taking transition-related medications, and 34% of patients had a documented psychiatric inpatient stay.

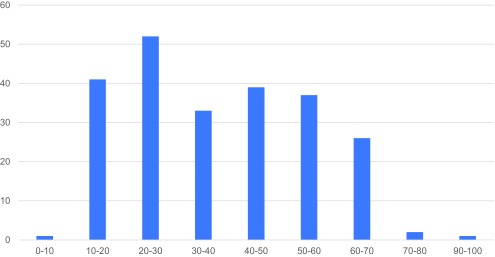

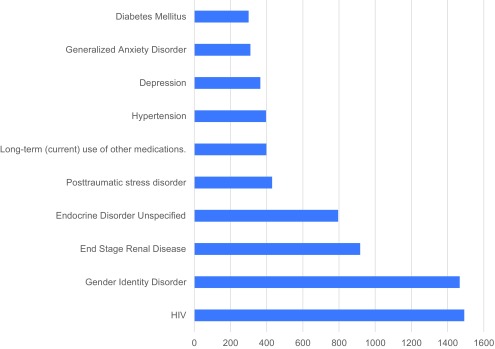

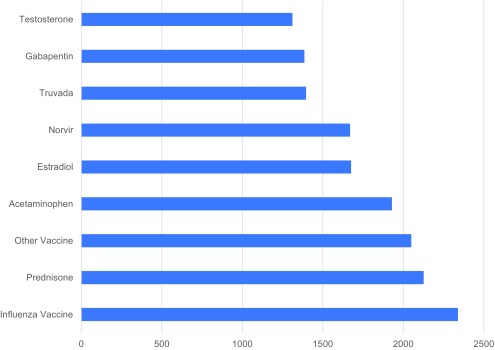

Figure 1 shows the distribution of age. Figure 2 shows the most frequent diagnoses (from ICD-9 codes) associated with patient cohort and Figure 3 shows the most frequent medications administered. Notable findings are that the top ICD-9 code is 042 (diagnosis of HIV), two of the top ten medications are hormones (estradiol and testosterone), and two of the top medications are anti-retroviral medications (Norvir and Truvada).

Figure 1. Age distribution.

Figure 2. Top 10 diagnoses.

Figure 3. Top medications.

Discussion

We created a novel approach to successfully identify transgender patients in an EHR system. Given that very few health centers today in the United States are capturing gender identity data using structured approaches, this type of strategy will remain important as health care institutions develop electronic approaches to investigate the epidemiology of transgender health and health care quality. At Vanderbilt, we have used the tools described in this work as a part of our larger efforts to develop quality metrics specific to transgender patients as well as track referral patterns and clinic utilization. Additionally, these tools have been further leveraged to support both the development of additional clinical documentation tools within our electronic health records, and the functionality to provide real-time clinical decision support during clinical encounters with transgender patients.

A core strength of our work is the low false positive rate of our algorithm, especially given that 11% is a typical threshold for acceptable false positives.24 Requiring both a keyword and ICD code allowed for the more precise identification of transgender patients. ICD codes, which are used for diagnostic and billing reasons, can be used to identify transgender patients because gender dysphoria and gender identity disorder appear as mental health disorders in the DSM and therefore have associated billing codes. Notably, outdated transgender-related terms also appear in the diagnostic codes (eg, ICD9 302.53, “trans-sexualism with heterosexual history”). The inclusion of not only billing codes but also keywords in our algorithm is important for future work seeking to increase the sensitivity of algorithms to identify transgender patients in EHR systems. Of note, algorithms only using ICD codes may not identify all transgender patients in the EHR because not all transgender patients fit the diagnostic criteria for Gender Dysphoria (GD) or Gender Identity Disorder (GID) or desire to have a documented diagnosis of GD or GID. Additionally, not all transgender people who do fit the diagnostic criteria wish to medically transition and therefore may not appear in algorithms limited to ICD codes.

Our approach is not without limitations. Unlike previous investigations, requiring both keywords and billing codes to identify transgender patient EHR cohorts, our algorithm did detect false positive cases.21 For a false positive to have occurred in our study, a provider must have used a keyword term in a clinical note and incorrectly entered a related ICD code. In the limited number of cases where our algorithm detected false positive results, the text containing the keyword was often embedded in descriptions contained in the social history section of the EHR (eg, “the patient’s boyfriend is a transmale individual”). Negation language also contributed to false positive detection (eg, “the patient is not transgender”). Another limitation of both our work (and also of structured gender identity data capture approaches) is that patients who had not disclosed their transgender identity to their provider or who had requested that their gender identity not be documented in their medical record would not be detected by our algorithm, thereby contributing to false negative results. Other factors leading to false negatives include lack of provider education of transgender identities. We found evidence that many providers did not understand transgender identities in our chart review analysis. Providers frequently ambiguously documented the gender identities of transgender patients, making it difficult to determine if patients were trans men (female-to-male/FTM), trans women (male-to-female/MTF), or genderqueer, such as only documenting that patients identify as transgender but not if they identify as a binary identity (trans man or trans woman) or as a non-binary identity (eg, non-binary or genderqueer) (Table 1). We also observed that providers documented patient pronouns in non-affirming ways (eg, “(s)he”) or change pronouns throughout the same note or patient encounter. The lack of provider education likely also contributed to another key limitation of our work - the low sensitivity of our algorithm to identify genderqueer patients in the EHR. This phenomenon will hopefully become self-limiting as more providers learn to accurately document genderqueer genders in patient medical records. Additionally, expanding our keyword search to include not only “genderqueer” but also “non-binary/nonbinary” may increase the number of positive results, since not all non-binary people identify as genderqueer. As language and common identity labels change, these keywords will need to be reassessed or additional identities will need to be added.

Of note, our algorithm was designed to have a low false positive rate by requiring the identification of both a keyword and a diagnosis code. This approach therefore could not identify transgender patients who only met one criteria and would create a false negative event. However, our approach has and will continue to be useful in generating cohorts of transgender patients where there is confidence about the gender identity of those included. Therefore, this algorithm and our approach is best used in situations where it is important to clearly identify transgender patients (ie, for research, quality management, or utilization review programs), but would not necessarily be helpful in quantifying the overall incidence of transgender patients.

Given that we undertook a detailed manual chart review after using the algorithm for case identification, we have confidence that our algorithm performed well over a large cohort of patients receiving care from a large variety of clinicians at a large health care system. Given the diversity of care settings, clinics, and notes reviewed, we expect the approach to be widely generalizable. However, it will be important to keep in mind that as terminology and diagnoses change, the suitability of the algorithm may also vary.

Conclusion

In summary, this study represents an important step forward in understanding how to identify transgender patient cohorts within EHR systems lacking structured methods of capturing gender identity or that have a low utilization of structured gender identity collection methods, thereby enabling characterization and analysis of the health care experience of transgender patients in large health systems. Additional research on identifying transgender patients in EHRs is necessary. There are still many outstanding questions about the best way to collect these data, such as: 1) who should collect the information; 2) at what point in the care process it should be collected; and 3) how often it should be updated – as some of the elements of gender identity may change over time. These unanswered questions lead to important policy implications, as clinicians and health systems grapple with larger issues around data collection of transgender and other sexual minority patients. Given our findings, and the fact that more EHRs are increasing the technical capabilities for documenting transgender patient identity (eg, patient self-identification in secure portals), we recommend using consistent structured data collection whenever possible but only after provider training and education about the nuances of documenting transgender status.

In the future, as more providers document gender identity in the EHR, it will be possible to conduct larger and more robust studies on the use of NLP as well as using the results to further explore transgender health outcomes. Applications of this work can contribute to the development of tools in the EHR to better document the gender identity of transgender patients, which will lead to assessing the quality of transgender health care and prioritization of health services for transgender patients. Overall, this research can promote health equity among transgender populations at the health systems level.

Acknowledgments

The project described is supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Grant Number U54MD008173, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIMHD or NIH.

References

- 1. Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Milbank Q. 2017;95(4):726-748. 10.1111/1468-0009.12297 10.1111/1468-0009.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reisner SL, Bailey Z, Sevelius J Racial/ ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women Health. 2014;54(8):750-767. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/03630242.201 4.932891 PMID:25190135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Habarta N, Wang G, Mulatu MS, Larish N. HIV Testing by Transgender Status at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Funded Sites in the United States, Puerto Rico, and US Virgin Islands, 2009-2011. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1917-1925. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siembida EJ, Eaton LA, Maksut JL, Driffin DD, Baldwin R. A comparison of HIV-related risk factors between Black transgender women and black men who have sex with men. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):172-180. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team . Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1-17. 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pérez-Stable EJ. Director’s Message: Sexual and Gender Minorities Formally Designated as a Health Disparity Population for Research Purposes. 2016. Last accessed Jan. 10, 2019 from https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/message_10-06-16.html

- 7. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian , Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. Last accessed April 22, 2019 from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/ [PubMed]

- 8. American Psychological Association Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70(9):832-864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polderman TJC, Kreukels BPC, Irwig MS, et al. ; International Gender Diversity Genomics Consortium . The biological contributions to gender identity and gender diversity: bringing data to the table. Behav Genet. 2018;48(2):95-108. 10.1007/s10519-018-9889-z 10.1007/s10519-018-9889-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Standards of Care (SOC) for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. World Professional Association for Transgender Health;2012. Last accessed April 22, 2019 from https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

- 11.Gallup. In U.S., Estimate of LGBT Population Rises to 4.5%. 2018. Last accessed April 22, 2019 from https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises. aspx

- 12. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, Barker MJ, Nieder TO, T’Sjoen G. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):95-102. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446 10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reisner SL, Gamarel KE, Dunham E, Hopwood R, Hwahng S. Female-to-male transmasculine adult health: a mixed-methods community-based needs assessment. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2013;19(5):293-303. 10.1177/1078390313500693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Adolescent gender-related abuse, androphilia, and HIV risk among transfeminine people of color in New York City. J Homosex. 2014;61(5):691-713. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00918369.201 4.870439 PMID:24294927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Donald C, Ehrenfeld JM. The opportunity for medical systems to reduce health disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex patients. J Med Syst. 2015;39(11):178. 10.1007/s10916-015-0355-7 10.1007/s10916-015-0355-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Bhasin S, et al. Advancing methods for US transgender health research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):198-207. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients—practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843-847. 10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kirkham C, Butler P, Raynor L, et al. Identifying Transgender Patients in Electronic Health Records Systems: A Systematic Review. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Medical Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown GR, Jones KT. Racial health disparities in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1(4):257-266. 10.1007/s40615-014-0032-4 10.1007/s40615-014-0032-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roblin D, Barzilay J, Tolsma D, et al. A novel method for estimating transgender status using electronic medical records. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(3):198-203. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kauth MR, Shipherd JC, Lindsay J, Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Jones KT. Access to care for transgender veterans in the Veterans Health Administration: 2006-2013. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S4)(suppl 4):S532-S534. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carter ME, Divita G, Redd A, et al. Finding ‘evidence of absence’ in medical notes: using NLP for clinical inferencing. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;226:79-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]