Introduction

Currently, HIV treatment is recommended for all persons living with HIV (PLWH) regardless of their immune status in order to prevent HIV-related morbidity, mortality and reduce transmission to others[1, 2]. There are multiple first line antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens recommended for treatment-naïve PLWH based on efficacy and tolerability data obtained in randomized controlled trials[3, 4]. Each contains 3 or more antiretroviral agents, and most contain an Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor (InSTI). A majority of these ART regimens contain an antiretroviral agent that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the last 3 years based on short-term surrogate endpoints including achieving viral suppression[5–7]. Further, these first line regimens have demonstrated relatively little toxicity, like neurologic disturbances, in select samples and controlled settings[8, 9]. Due to their novelty, many of these contemporary ART regimens have not been studied in observational cohorts.

Because participants in a randomized control trial (RCT) may vary greatly from real world populations (race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and adherence rates), and additional supports are afforded by the RCT environment, it is important to study ART outcomes as a part of routine care to demonstrate the comparative effectiveness of novel ART[10, 11]. Real world ART durability may reflect more subjective treatment outcomes like quality of life or mild side effects that affect adherence in routine care and are likely of greater importance in clinic-based samples consisting of more diverse and heterogeneous PLWH in routine HIV care[12]. Provider and patient decisions also contribute to real world durability[13].

Recently, two national multi-site cohorts have demonstrated improved durability of ART [14, 15]. Notably, these studies extended to 2009 and 2011, respectively, precluding the study of novel antiretroviral agents, like elvitegravir, and dolutegravir, which are now included in first line treatment guidelines[3]. In our single-site clinic population we found that, in treatment naïve individuals, ART durability was decreasing in recent years (2010–2012 vs. 2007–2009); largely due to the availability of newer ART regimens, which afford improved tolerability and dosing convenience[13, 16]. This trend emerged when patients and providers selected novel ART to replace older ART, abbreviating the durability of older regimens in the current treatment era. Yet, these findings are already dated by the dynamic ART treatment landscape in which several novel regimens have been FDA-approved and increasingly adopted as first-line ART since the conclusion of this study.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the durability, defined as time to regimen modification (including discontinuation), of novel ART regimens, including those released since 2012, as part of routine care in a multi-site cohort in the U.S. We examined various socio-demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the initial regimen modification. We hypothesized that novel InSTI-based regimens would be more durable than older regimens and that overall durability would decrease in more recent years, reflective of a treatment landscape that now includes multiple well tolerated co-formulated and single tablet ART regimens, based on prior research in our clinic cohort and elsewhere[13, 16].

Methods

This was a retrospective follow-up study conducted within the CFAR Network of Integrated Systems (CNICS) Cohort. CNICS is a research network capturing clinical, socio-demographic, and behavioral information in an electronic database including more than 32,000 PLWH in the modern ART era at 8 HIV treatment sites in the U.S, including University of Alabama at Birmingham; University of Washington; University of California, San Francisco; University of California, San Diego; Case Western Reserve University; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Johns Hopkins University; and Fenway Health/Harvard University. The CNICS data repository includes social, demographic, pharmacologic, laboratory, and diagnostic data collected through electronic medical records at each of the 8 CNICS sites[17]. Quality assessment is performed at all sites individually prior to submission to the CNICS data management core. All data that are transmitted to the central repository undergoes additional quality assessment to ensure accuracy. We included treatment-naïve adult patients (>18 years of age) initiating ART (≥ 3 drugs) for at least 14 days between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2014 in the CNICS Cohort. Administrative censoring occurred between January 2013 and July 2015, depending on data collection at each CNICS site. We excluded patients with a baseline (at ART initiation) viral load <200 copies/mL to remove elite controllers as well as those potentially misclassified as ART naive from the sample. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and each participating CNICS site has Institutional Review Board approval for the cohort.

Outcome Variable

The outcome of interest was the durability of the initial regimen. Durability was calculated as the number of months from the regimen initiation until discontinuation/modification or death, whichever occurred earlier (“Modified”). Regimen modification was defined as any change in the ART composition. Patients who did not experience the event (“Continued”) were censored at their last contact with the health system (e.g. arrived visit, lab result); 90 days were added to the duration of the ART regimen from that date assuming patients continued their medication for that period. If a patient was switched from individual drugs to a fixed-dose combination (FDC) of the same constituent drugs, the regimen was considered “Continued.”

Independent Variables

Baseline HIV biomarkers markers (CD4, VL), age, sex, race, HIV transmission risk factor, insurance status, and ART regimens were extracted. ART regimens were categorized according to regimen composition (≥ 3 antiretroviral agents) and class of the ART anchor drug. Initiation era was categorized as 2007–2009, 2010–2012, and 2013–2015 according to the calendar year of regimen initiation. Drug classes included those receiving a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), boosted protease inhibitor (PI), or an integrase inhibitor (InSTI) based regimen or an integrase inhibitor combined with a boosted protease inhibitor (InSTI/PI). Those receiving an NNRTI/InSTI and NNRTI/PI-based regimen were categorized as InSTI -based and PI-based, respectively, according to the most potent component[18, 19].

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive evaluation was performed by grouping patients as “Modified” or “Continued” depending upon the regimen modification status as described earlier. Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations (SDs). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (with percentages). Time to modification of the initial regimen (durability) was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Median durability time is reported in months and compared across stratified variables using the log-rank test. Association of various characteristics with time to regimen modification was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards (PH) models to estimate crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We adjusted for the following clinically important variables: age, race, sex, transmission risk factor (MSM, IVDU, heterosexuality), CD4 count, VL, initiation era (2007–2009, 2010–2012, 2013–2015), and class of ART regimen. Additionally, a multivariable model using individual drug regimen instead of class was also examined. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 5,373 patients met study inclusion criteria with a mean age of 38 years (SD 10.9) at ART initiation. The participants were 38% black, 85% male; 64% MSM, 25% uninsured. The baseline mean CD4 cell count was 332 cells/mm3 (SD 226), and the mean baseline VL was 31,162 copies/mL (SD 138,348). Efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir (n= 2173, 40%) was the most commonly prescribed initial ART regimen overall (Table 1), but Elvitegravir/cobicistat/ emtricitabine/tenofovir became more common after FDA approval in 2012 (Supplemental Figure). A majority were receiving an NNRTI-based regimen (n=2,637), and a minority were receiving an NNRTI/ InSTI (n= 34) and NNRTI/PI based regimen (n=26), which were categorized as InSTI and PI-based, respectively as described above.

Table 1.

Characteristics of treatment naïve PLWH initiating care in the CNICS Cohort between 2007 and 2015

| Characteristic | Total=5373 | Modifieda=2285 | Continueda=3088 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <30 | 1468 (27) | 596 (26) | 872 (28) |

| 30–45 | 2511 (47) | 1049 (46) | 1462 (47) |

| >45 | 1394 (26) | 640 (28) | 754 (25) |

| Race | |||

| White | 2638 (49) | 1098 (48) | 1540 (50) |

| Black | 2015 (38) | 911 (40) | 1104 (36) |

| Other | 720 (13) | 276 (12) | 444 (14) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 4546 (85) | 1841 (81) | 2705 (88) |

| Female | 827 (15) | 444 (19) | 383 (12) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 663 (12) | 248 (11) | 415 (13) |

| Public | 997 (19) | 451 (20) | 546 (18) |

| Uninsured | 1336 (25) | 495 (21) | 841 (27) |

| Unknown | 2377 (44) | 1091 (48) | 1286 (42) |

| Transmission Mode | |||

| MSM/Homosexual | 3463 (64) | 1380 (60) | 2083 (67) |

| Heterosexual | 1160 (22) | 540 (24) | 620 (20) |

| IVDU | 332 ( 6) | 192 ( 8) | 140 ( 5) |

| Other | 418 ( 8) | 173 ( 8) | 245 ( 8) |

| VL at regimen initiation (copies per mL) | |||

| <10,000 | 1,210 (23) | 474 (21) | 736 (24) |

| ≥10,000 | 4,163 (77) | 1,811(79) | 2,352 (76) |

| CD4 cell countb (mm3) at regimen initiation | |||

| ≥200 | 3804 (71) | 1507 (66) | 2297 (75) |

| <200 | 1551 (29) | 772 (34) | 779 (25) |

| Initiation Era (Year) | |||

| 2007–2009 | 1882 (35) | 1003 (44) | 879 (28) |

| 2010–2012 | 2135 (40) | 938 (41) | 1197 (39) |

| 2013–2015 | 1356 (25) | 344 (15) | 1012 (33) |

| Drug class | |||

| InSTI | 1110 (21) | 279 (12) | 831 (27) |

| InSTI/PI | 76 ( 1) | 49 ( 2) | 27 ( 1) |

| NNRTI | 2637 (49) | 1079 (47) | 1558 (50) |

| PI | 1547 (29) | 875 (39) | 672 (22) |

| Regimen | |||

| Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine | 106 ( 2) | 11 ( 0) | 95 ( 3) |

| Atazanavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 665 (12) | 382 (17) | 283 ( 9) |

| Darunavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 546 (10) | 245 (11) | 301 (10) |

| Dolutegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 89 ( 2) | 20 ( 1) | 69 ( 2) |

| Efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2173 (40) | 927 (41) | 1246 (40) |

| Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 571 (11) | 69 ( 3) | 502 (16) |

| Raltegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 286 ( 5) | 135 ( 6) | 151 ( 5) |

| Rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 336 ( 6) | 71 ( 3) | 265 ( 9) |

| Other | 601 (11) | 425 (19) | 176 ( 6) |

ART=anti-retroviral therapy; CNICS=CFAR Network of Integrated Systems; InSTI =integrase inhibitor; MSM=men having sex with men; PI=protease inhibitor; NNRTI= a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PLWH=people living with HIV/AIDS.

Patients in whom initial regimen was discontinued/modified or those who died while on the initial regimen were grouped as “Modified” while patients who remained on the initial regimen during the study period were grouped as “Continued.”

Missing data: Modified=6, Continued=12.

Regimen Durability

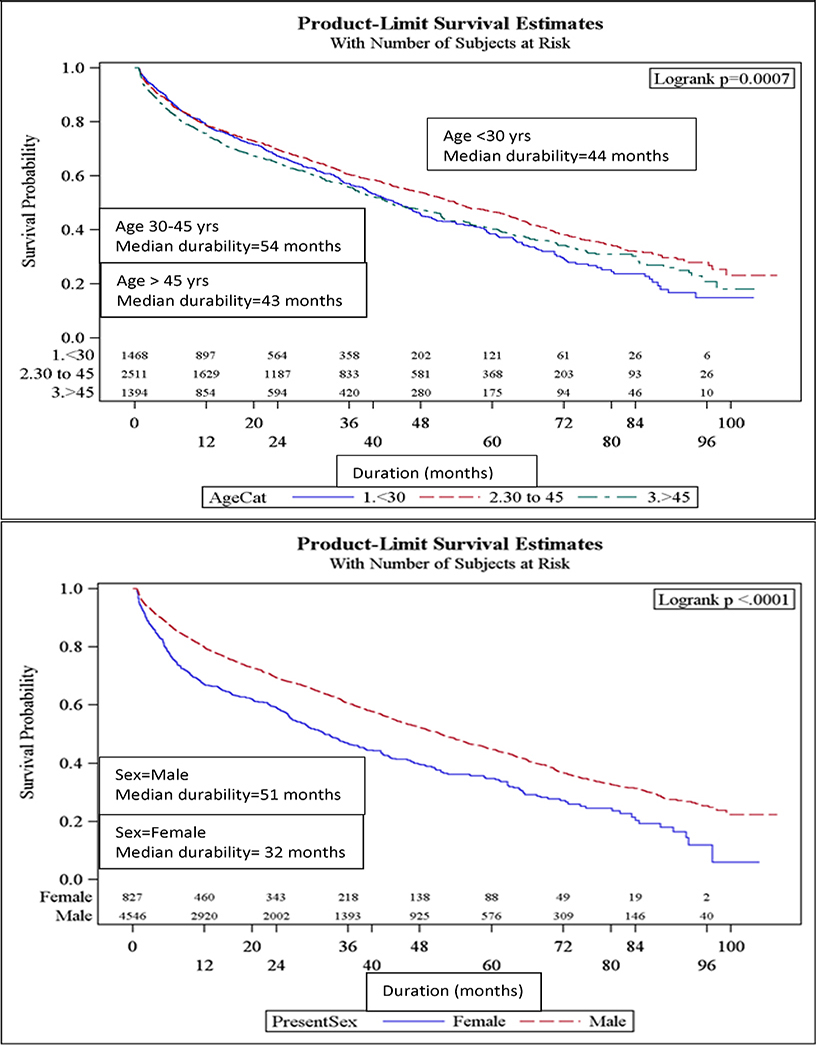

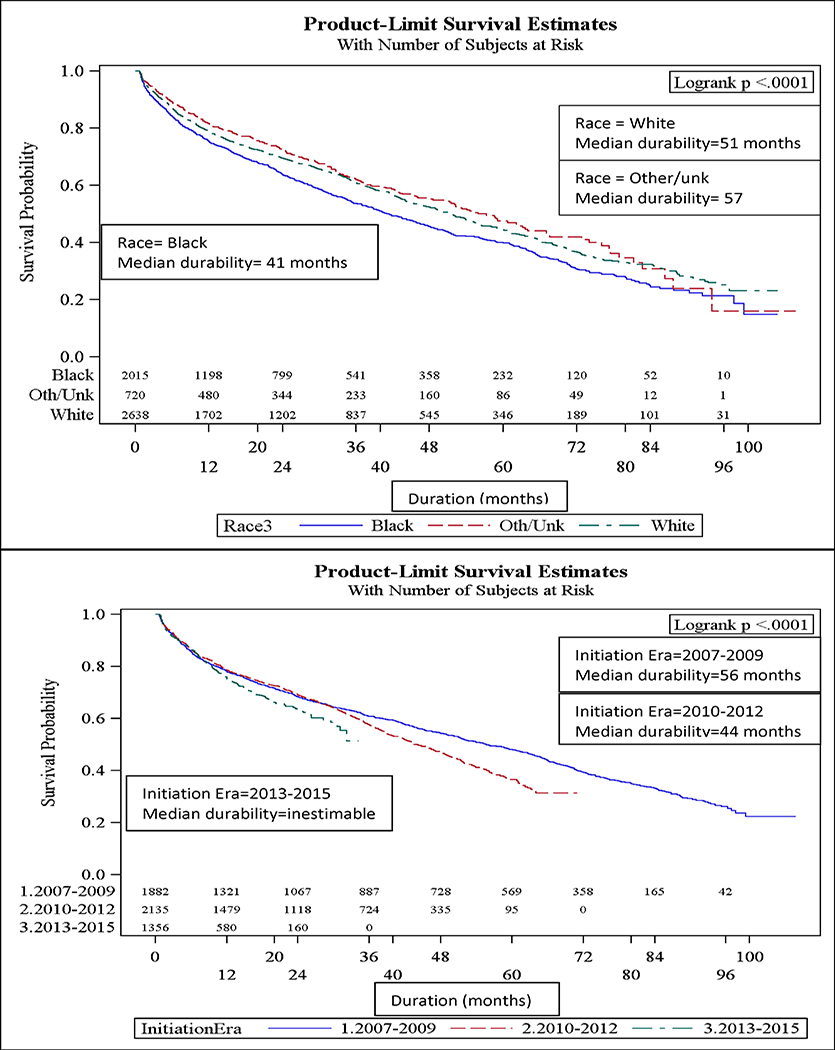

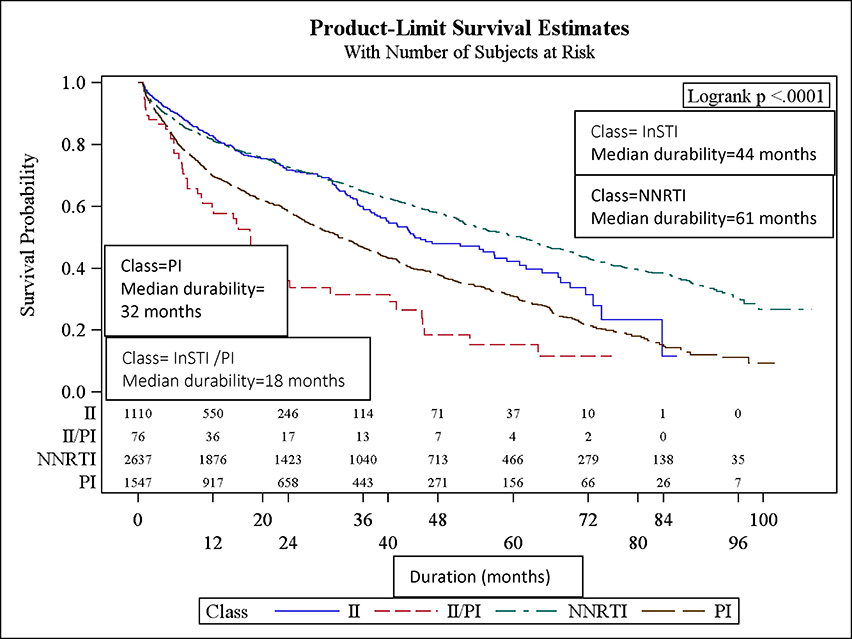

Overall, the median durability of initial ART regimens was 49 months (95% CI: 45, 51). Females, younger patients (<30 yrs old), black patients (Figure 1a–c), and IVDU had significantly shorter initial ART regimen durability. The median durability of NNRTI-based regimens was longest (median durability = 61 mos), followed by InSTI- based (44 mos) and PI-based regimens (32 mos; Figure 1d). The relative durability of ART regimens according to class, 3-drug composition, and year of initiation is summarized in Table 2. Efavirenz and rilpivirine-based ART were the most durable: 62 and 70 mos, respectively. Raltegravir-based ART were the most durable of the InSTI-based regimens, while evitegravir and dolutegravir-based ART durability were inestimable because the median had not yet been reached (over half of patients “Continued” on these ART regimens). Reduced median durability of ART regimens was found in regimens initiated in 2010–2012 (44 mos) relative to 2007–2009 (56 mos). Those initiating in 2013–2015 experienced a median durability that was inestimable (25th percentile: 12 mos) (Figure 1c; p-value<0.0001).

Figure 1a-e.

Median durability of ART regimens according to age, sex, race, year of initiation, and ART class in a multisite cohort of treatment naïve PLWH

Table 2:

Summary of median durability of ART regimen by regimen class, composition, and year of initiation in treatment naïve HIV patients initiating care in a multi-site cohort

| Class of ART backbone | Treatment share N (%) | Median durability, months (95% CI) |

| Integrase Inhibitor | 1110 (21) | 44 (40, 57) |

| Integrase Inhibitor/Protease Inhibitor | 76 (1) | 18 (10, 24) |

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | 2637 (49) | 61 (56, 65) |

| Protease Inhibitor | 1547 (29) | 32 (29, 35) |

| ART regimen composition | Treatment share N (%) | Median durability, months (95% CI) |

| Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine | 106 (2) | 9!, * |

| Atazanavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir/r | 665 (12) | 36 (31,42) |

| Darunavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 546(10) | 41 (36, 47) |

| Dolutegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 89 (2) | 5!, 22! |

| Efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2173 (40) | 62 (56,65) |

| Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 571 (11) | 33!, * |

| Raltegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 286 (5) | 43 (36,57) |

| Rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 336 (6) | 70 (47, *) |

| Other | 601 (11) | 18 (15,22) |

| Year of ART regimen initiation |

Treatment Share N (%) |

Median durability, months (95% CI) |

| 2007–2009 | 1882 (35) | 56 (51,61) |

| 2010–2012 | 2135 (40) | 44 (42,47) |

| 2013–2015 | 1356 (25 ) | 11!, 31! |

Median durability calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves

Point estimate not estimable thus 25th and 75th percentile is shown

75th percentile is not estimable

Factors Associated with Time to Regimen Modification

The initial ART regimen was modified in 2,285 patients (43%). Table 1 compares the baseline clinical and sociodemographic characteristics (obtained prior to ART initiation) of those who modified versus continued their initial regimen. Of those who modified their regimen, 55% (n=1,257) had a detectable viral load at the time of modification. According to ART class “backbone,” the percentage who modified their regimen with a VL ≥200 copies/mL was 51%, 35%, 10% and 3% for NNRTI, PI, InSTI and InSTI/PI-based regimens, respectively. The percentage who modified their regimen in the setting of a VL≥200 copies/mL (ie. virologic failure) was less than 10% for all regimens except the atazanavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir (15%), efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir (43%), and regimens classified as other (21%). The percentage who modified with a detectable VL also decreased each year from 56% (2007) to 12% (2015).

In univariate analysis (Table 3), the following factors were significantly associated with regimen modification: ART backbone class (NNRTI, PI, InSTI, InSTI /PI), black race, female sex, public and unknown insurance, IVDU, heterosexual HIV transmission, lower CD4 cell count and initiation in more recent years (2010–2012 and 2013–2015). In a multivariable model, patients aged 30 to 45 were less likely to modify their initial ART regimen (aHR=0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9, Table 3) relative to those < 30 years old. Those with black race (aHR=1.1; 95% CI: 1.0–1.2) relative to white race, female sex (aHR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.2–1.6), IVDU (aHR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–1.9) relative to homosexual HIV transmission riks, and CD4 cell count <200 (aHR=1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.3) relative to CD4 count ≥200 were more likely to have regimen modification. Compared to patients initiating ART during 2007–2009, those initiating ART during 2010–2012 (aHR=1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.3) and 2013–2015 (aHR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.3–1.8) era were more likely to modify ART. Relative to InSTI -based regimens, those regimens that were InSTI /PI (aHR=2.7, 95% CI: 2.0–3.7) or PI-based (aHR=1.9, 95% CI: 1.6–2.2) were significantly more likely to be modified. NNRTI-based regimens were not significantly more likely to be modified relative to InSTI -based regimens.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for initial regimen modification for treatment naïve PLWH in the CNICS cohort initiating ART between 2007 – 2015 by cox proportional hazard and categorized by ART drug class

| Characteristic | Univariate analysisa | Multivariable analysisa,b | Multivariable analysisa,b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| <30* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 30–45 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.01 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | <0.001 |

| >45 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 0.52 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.12 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||||

| White* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Black | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0,1.2) | 0.05 | 1.0 (0.9,1.1) | 0.53 |

| Other | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.19 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.19 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.09 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Female | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Uninsured* | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Private | 0.9 ( 0.8,1.0) | 0.16 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Public | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) | 0.004 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Unknown | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 0.002 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Transmission Mode | ||||||

| Homosexual* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Heterosexual | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.59 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.67 |

| IVDU | 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) | 0.01 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 0.32 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 0.21 |

| CD4 cell count | ||||||

| ≥ 200 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| <200 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.01 |

| Unknown | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 0.64 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.9) | 0.65 | 0.9 (0.4, 1.9) | 0.70 |

| Viral Load (copies/m3) | ||||||

| ≥10,000 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| <10,000 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.84 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.68 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.47 |

| Initiation Era | ||||||

| 2007–2009* | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 2010–2012 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| 2013–2015 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.3,1.8) | <0.001 | 2.6 (2.0, 3.0) | <0.001 |

| Class | ||||||

| InSTI * | 1.0 | 1.0 | -- | -- | ||

| InSTI /PI | 2.5 (1.8,3.4) | <0.001 | 2.7 (2.0, 3.7) | <0.001 | -- | -- |

| NNRTI | 0.9 (0.8,1.0) | 0.21 | 1.1 (1.0,1.3) | 0.16 | -- | -- |

| PI | 1.6 (1.4,1.8) | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) | <0.001 | -- | -- |

| Regimen | -- | -- | ||||

| Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine | 1.4 (0.8, 2.7) | 0.26 | -- | -- | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) | 0.24 |

| Atazanavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2.6 (2.0, 3.3) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 5.1 (3.8, 6.7) | <0.001 |

| Darunavir/ritonavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2.4 (1.8, 3.1) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 4.0 (3.0, 5.3) | <0.001 |

| Dolutegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2.7 (1.6, 4.4) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 2.6 (1.6, 4.3) | <0.001 |

| Efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 3.3 (2.5, 4.4) | <0.001 |

| Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/Tenofovir | 1.0 | -- | -- | 1.0 | ||

| Raltegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 2.2 (1.6, 2.9) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 3.9 (2.9, 5.4) | <0.001 |

| Rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) | 0.22 | -- | -- | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | <0.01 |

| Other | 4.2 (3.3, 5.4) | <0.001 | -- | -- | 8.0 (6.1, 10.7) | <0.001 |

ART=anti-retroviral therapy; CNICS=CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems; InSTI =integrase inhibitor; MSM=men having sex with men; PI=protease inhibitor; NNRTI= a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PLWH=people living with HIV/AIDS.

All characteristics (column 1) were obtained prior to ART initiation

Model 1 includes all variables displayed in table except insurance and regimen composition

Model 2 includes all displayed variables except insurance and backbone drug

is reference category

Cox Proportional hazards model

Multivariable model

Next, evaluation of individual regimen durability according to 3 or 4 drug composition rather than drug class of the anchor drug were evaluated (Table 2). The results of multivariable analysis were similar to the anchor drug class analyses with regards to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Relative to Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/ tenofovir, the most commonly prescribed regimen in recent years, all regimens were significantly more likely to be modified with the exception of Dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine, which was statistically insignificant.

Discussion

In this diverse, multisite cohort of treatment naïve PLWH in the U.S., the overall durability of initial ART regimens in our cohort was over 4 years. A majority of treatment naïve PLWH (57%) remained on their initial regimen at the study end date. The dynamic treatment landscape in which an increased number of co-formulated and single tablet ART regimens became available over the study period (2007–2015) is evident in the changing prescribing trends, the increasing number of ART modifications, and the apparent reduction in ART durability (fig 1c) in more recent years. Although efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir previously was the most prevalent initial regimen, elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir has eclipsed it as the most commonly prescribed first-line ART in this real world cohort[20]. Of all drug classes, InSTI and NNRTI-based regimens were the most durable and least likely to be modified. Consistent with our hypothesis, new regimens dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine and elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir were highly durable and least likely to be modified over the study period. Notably, dramatic shifts were observed in virologic failure (>200 c/mL) at the time of ART modification over the study period. Whereas over 50% of modifications were associated with virologic failure (VF) in the earlier period, fewer than 10% of ART changes were in the setting of VF in more recent years. Taken together, these findings suggest that the contemporary ART era affording numerous simple, well tolerated regimens has resulted in treatment changes for convenience and side effects, rather than virologic failure, paradoxically resulting in less durable regimens in more recent years.

Despite current dogma and treatment guideline recommendations, results demonstrate that NNRTI-based regimens are highly durable, even surpassing the InSTI-based regimens, and unlikely to be modified. The relative NNRTI durability is likely due to longer time on the market: most NNRTI-based regimens have been available for > 7 years, unlike many InSTI -based ART. Moreover, for a long period, the only approved single tablet ART regimen available was NNRTI based, hence, side effects with this regimen may have been more acceptable to patients and providers in the absence of other simple regimens. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that NNRTI based regimens are extremely durable with a median time to modification of 61 months. When comparing ART regimens according to composition, all but one (i.e.,dolutegravir/ abacavir/lamivudine) are more likely to be modified relative to elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir. This likely reflects changing prescribing practices: InSTI -based regimens, especially single tablet formulations, are more popular, and appear to be usurping older NNRTI and PI-based regimens, leading to more regimen modifications (supplemental fig)[13, 21].

Our study is unique in that it includes novel ART, like raltegravir, elvitegravir, and dolutegravir which were introduced over the study period in 2007, 2012, and 2013, respectively. It is likely that the increased ART modification and decreased ART durability in more recent years (2010–2012, 2013–2015 vs 2007–2009) results from a preference for newer, convenient single tablet regimens including those containing novel ART anchor drugs, Dolutegravir and Elvitegravir.[13, 16] As older regimens are replaced by newer, once daily regimens, their measured durability is subsequently abbreviated. These findings need further study to analyze if the apparent reduced durability of InSTI -based regimens relative to NNRTIs is due to switching within the class (ie. raltegravir to dolutegravir; dolutegravir multi-tablet to fixed dose combination). Furthermore, the reduced number of PLWH who modified their initial regimen due to elevated viral load levels (ie. VL ≥200 copies/mL) supports the notion that people are switching their regimens for reasons other than virologic failure. Regimen simplification and/or convenience is a leading cause of regimen modification, and virologic failure, resistance and/or treatment-limiting side effects are less likely in the current treatment landscape[16],[21].

Although there are inherent challenges in measuring durability (e.g., ART availability, provider preferences), when adjusting for ART regimen, year of initiation, and other sociodemographic characteristics, we observed notable differences in vulnerable populations. Youth, females, blacks, and IVDU experienced reduced ART durability. It is likely that those with comorbid IVDU experience reduced adherence, resistance and virologic failure contributing to this trend[22, 23]. Poor durability in women, youth and blacks is more complex. In our study and others, women are more likely to modify their regimen and have significantly shorter time to regimen modification[13] [23]. This data suggests there may be ART differences related to pregnancy, pharmacokinetics, and/or health disparities in females with HIV [22, 23]. Black experience slightly reduced ART durability relative to white PLWH when adjusting for clinical and ART-related differences. ART outcomes experienced by racial and gender minorities in the contemporary ART treatment era should be further investigated in observational settings to identify and eliminate disparities. Finally, evaluating and optimizing poor ART outcomes in those <30 years of age is crucial as this population is disproportionately affected by HIV in the modern era[24, 25].

This study is limited by a lack of data on patient-reported reasons for regimen modification, which could include side effects, toxicity, and/or desire for more convenient dosing (ie. single tablet regimen). Likewise, reasons for regimen selection (e.g., opportunistic infection, renal insufficiency) were not available but would shed additional light on prescribing patterns.

In addition, due to a small number and short follow up time of PLWH receiving some of the most novel regimens (ie. dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine), it is difficult to interpret durability at the regimen level. Results that categorize by class, on the other hand, are sufficiently powered and have a greater cumulative follow up time to allow interpretation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study evaluates the durability of novel ART agents and regimens, including InSTI and fixed dose combination single tablet ART, in treatment naïve PLWH in a real world, multisite cohort initiating therapy from 2007 to 2015. We found that new classes and antiretroviral agents are highly durable relative to older, multi-tablet regimens. In addition, the adoption of these novel regimens has contributed to an overall reduction in durability and increase in regimen modifications over time. Simultaneously, a dramatic temporal reduction in virologic failure at the time of regimen modification was observed. Taken together, these findings suggest that the contemporary ART era affording numerous simple, well tolerated regimens has resulted in treatment changes for convenience and side effects, rather than virologic failure, paradoxically resulting in less durable regimens in more recent years. Finally, minorities, youth, women and IVDU have disparate ART durability outcomes, which suggest ongoing ART challenges in vulnerable populations and deserves further evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the CFAR Network of Integrated Systems (CNICS) for their assistance with data collection.

References

- 1.Lundgren JD, et al. , Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373(9): p. 795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, et al. , Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DHHS. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. [cited 2016 August 10]; Available from: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv-guidelines/0.

- 4.Gunthard HF, et al. , Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2016 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. Jama, 2016. 316(2): p. 191–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clotet B, et al. , Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (FLAMINGO): 48 week results from the randomised open-label phase 3b study. Lancet, 2014. 383(9936): p. 2222–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walmsley SL, et al. , Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(19): p. 1807–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sax PE, et al. , Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet, 2015. 385(9987): p. 2606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stellbrink HJ, et al. , Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 51(8): p. 963–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wohl D, et al. , Brief Report: A Randomized, Double-Blind Comparison of Tenofovir Alafenamide Versus Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate, Each Coformulated With Elvitegravir, Cobicistat, and Emtricitabine for Initial HIV-1 Treatment: Week 96 Results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2016. 72(1): p. 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo-Mancilla JR, et al. , Minorities remain underrepresented in HIV/AIDS research despite access to clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials, 2014. 15(1): p. 14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieuwkerk PT, et al. , LImited patient adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for hiv-1 infection in an observational cohort study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2001. 161(16): p. 1962–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Dakkak I, et al. , The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care, 2013. 25(4): p. 400–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton EF, et al. , Unanticipated effects of new drug availability on antiretroviral durability: Implications for Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2016: Open Forum Infectious Diseases; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheth AN, et al. , Antiretroviral regimen durability and success in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients by year of treatment initiation, United States, 1996–2011. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slama L, et al. , Increases in duration of first highly active antiretroviral therapy over time (1996–2009) and associated factors in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 65(1): p. 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Biagio A, et al. , Discontinuation of Initial Antiretroviral Therapy in Clinical Practice: Moving Toward Individualized Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2016. 71(3): p. 263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitahata MM, et al. , Cohort profile: the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. Int J Epidemiol, 2008. 37(5): p. 948–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowitz M, et al. , Rapid and durable antiretroviral effect of the HIV-1 Integrase inhibitor raltegravir as part of combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: results of a 48-week controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2007. 46(2): p. 125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arribas JR, et al. , The MONET trial: week 144 analysis of the efficacy of darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) monotherapy versus DRV/r plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, for patients with viral load < 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL at baseline. HIV Med, 2012. 13(7): p. 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinnell JA, et al. , Antiretroviral prescribing patterns in treatment-naive patients in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2010. 24(2): p. 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotte L, et al. , Effectiveness and tolerance of single tablet versus once daily multiple tablet regimens as first-line antiretroviral therapy - Results from a large french multicenter cohort study. PLoS One, 2017. 12(2): p. e0170661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robison LS, et al. , Short-term discontinuation of HAART regimens more common in vulnerable patient populations. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2008. 24(11): p. 1347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes AJ, et al. , Discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy among adults receiving HIV care in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 66(1): p. 80–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reportable STDs in Young People 15–24 Years of Age, by State. 2013; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/by-age/15-24-all-stds/default.htm.

- 25.The Centers for Disease Control. HIV in the United States: At A Glance. July 2015. [cited 2016 February 26]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_basics_ataglance_factsheet.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.