Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Prostate cancer racial disparities in mortality outcomes is the largest in all of oncology, and less aggressive treatment received by African-American (AA) vs. Caucasian patients is likely a contributing factor. However, reasons underlying differences in treatment are unclear.

METHODS:

Prospective, population-based cohort of 1170 men with newly-diagnosed, non-metastatic prostate cancer enrolled from 2011 to 2013, before treatment, throughout North Carolina. By phone survey, each participant was asked to rate their cancer aggressiveness and their response was compared to actual diagnosis based on medical record review. Participants were also asked to rate the importance of 10 factors on their treatment decision-making process.

RESULTS:

78–80% of AA and Caucasian patients with NCCN low-risk cancer perceived their cancers to be “not very aggressive.” However, among high-risk patients, 54% of AA considered their cancer “not very aggressive,” compared to 24% of Caucasian patients (p<.001). Although both AA and Caucasian patients indicated “cure” to be a very important decision-making factor, AA were significantly more likely to consider cost, treatment time, and recovery time very important. In multivariable analysis, perceived cancer aggressiveness and cure as the most important factor were significantly associated with receiving any aggressive treatment; and associated with surgery (vs. radiation). After adjusting for these and sociodemographic factors, race was not significantly associated with treatment received.

CONCLUSIONS:

Racial differences in perceived cancer aggressiveness and factors important in treatment decision-making provide novel insights into reasons for the known racial disparities in prostate cancer, as well as potential targets for interventions to reduce these disparities.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, healthcare disparities, clinical decision-making, treatment outcomes, minority health

PRECIS:

In a population-based cohort, more African-American (AA) patients incorrectly perceived their cancers to not be aggressive. While both AA and Caucasian patients considered cure to be very important, AA patients were more likely to also indicate cost, treatment time and recovery time as important factors.

INTRODUCTION

Racial disparities in prostate cancer are well-described. Compared to Caucasian men, African-American (AA) men are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer.1 This difference is at least partly attributable to AA men having more aggressive and advanced disease at diagnosis, and receipt of more delayed and less-aggressive therapy.2–10 Notably, AA men are less likely to be treated with curative intent than Caucasian men,2,5,6 especially among men with intermediate- or high-risk disease.5

In a study by Moses et al. using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer across the United States, AA men were less likely to receive treatment (radical prostatectomy [RP], external beam radiation therapy [RT], or brachytherapy) compared to Caucasian men.11 Moreover, AA men received less aggressive treatment (i.e. less surgery and more radiation): RP (31.0% of AA patients vs 38.2% Caucasian), RT (26.8% AA vs 22.7% Caucasian).11 While published studies have consistently described less treatment overall and less aggressive treatment among AA men with prostate cancer – the reasons behind this disparity are not well understood and few studies have examined the factors influencing patients’ decisions that may contribute to this disparity.12–15

In a prospective, population-based cohort of patients with newly-diagnosed prostate cancer, we asked each patient about his priorities in the treatment decision-making process, and perceived aggressiveness of his diagnosed cancer. We hypothesized that there are differences between AA and Caucasian patients, which may provide insight into the observed treatment differences by race in prior studies. We hypothesize that these racial differences in perception and priorities may influence prostate cancer treatment selection. If so, future interventions to improve the accuracy of patients’ risk perception/understanding may improve the alignment between cancer aggressiveness and appropriate treatment selection, and in doing so, reduce racial disparities in mortality in prostate cancer – which is the largest disparity in all of oncology.16

METHODS

Patient Cohort

The North Carolina Prostate Cancer Comparative Effectiveness & Survivorship Study (NC ProCESS) enrolled patients with newly-diagnosed, non-metastatic prostate cancer throughout the state, in collaboration with the Rapid Case Ascertainment (RCA) system of the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry.17 RCA is an accelerated incident reporting system where registry staff proactively obtain information about newly diagnosed cancer patients from health care facilities in all 100 state counties within days of patient diagnosis. Patient information was then given to study staff for potential enrollment onto this prospective, observational cohort study. Participants were identified and enrolled between 2011 and 2013. Additional enrollment details have been described previously.17 The median time from cancer diagnosis to enrollment and completion of the baseline survey (conducted by phone) was 5 weeks; all patients were enrolled and completed baseline survey before treatment.

Data Collection

NC ProCESS collected data from 3 sources: participant self-report, cancer registry, and medical records. Cancer registry provided information on prostate cancer diagnosis (prostate specific antigen [PSA] level, Gleason score, and clinical stage; which we used to classify patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk disease using the NCCN guidelines)18 and patient age. Medical records and cancer registry data were used to determine primary treatment received within a year of diagnosis. Patients, who did not receive any treatment within 12 months after diagnosis were classified as “no initial treatment” and clinically is similar to an active surveillance approach. We used patient self-report for race and individual-level sociodemographic measures (education, insurance, employment, and household income). In addition, patients were asked questions regarding their perceived cancer aggressiveness and factors that contributed to their treatment decision-making process. Because validated instruments examining these issues do not exist8,12,14, the investigators drew from published studies to create the following questions specifically for this study:

- How aggressive is your prostate cancer?

- Not very aggressive

- Somewhat aggressive

- Very aggressive

- If you were making a decision today about treatment for your prostate cancer, please rate the following things by level of importance from very important, somewhat important, not important. (Patients rated each item separately)

- Preserving your quality of life

- Preserving your ability to have sex

- Preserving your ability to control your urination

- Preserving your bowel function

- Curing cancer

- Not being a burden on your family and friends

- The cost to you to receive this treatment

- The amount of time to receive treatment

- The amount of time to recover from treatment

- How this treatment affects your daily activities

Separately, participants were asked to identify the one most important factor impacting their decision-making process from the following list of options: curing cancer, preserving quality of life, not being a burden on family and friends, cost, how treatment affects daily activities, and other.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, factors impacting treatment decisions, and primary treatment received. The main focus of this study was to compare AA vs. Caucasian men, and Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the differences between groups. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the associations between race, perception of cancer aggressiveness, and treatment priorities with treatment selection. Two-sided p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

African-American men in the cohort were younger than Caucasian men and had more aggressive (higher risk) cancers (Table 1). Caucasian men overall attained higher educational levels and household income.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| African-American | Caucasian | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=304 N (%) |

N=866 N (%) |

||

| Age, median (range) | 62.4 (45.0 – 80.0) | 65.4 (41.0 – 81.0) | <.001 |

| Educational Level | |||

| High school or less | 156 (51.3) | 216 (24.9) | <.001 |

| Some college | 92 (30.3) | 247 (28.5) | |

| College graduate or higher | 56 (18.4) | 403 (46.5) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Public health insurance* | 188 (61.8) | 507 (58.6) | <.001 |

| Private health insurance | 87 (28.6) | 329 (38.0) | |

| None/other | 29 (9.5) | 30 (3.5) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 209 (68.8) | 724 (83.6) | <.001 |

| Not married | 95 (31.3) | 142 (16.4) | |

| Household Income | |||

| Less than $40,000 | 181 (62.6) | 232 (27.6) | <.001 |

| $40,001 to $70,000 | 68 (23.5) | 251 (29.9) | |

| $70,001 to $90,000 | 23 (8.0) | 135 (16.1) | |

| More than $90,000 | 17 (5.9) | 222 (26.4) | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 107 (35.2) | 389 (44.0) | <.001 |

| Retired | 121 (39.8) | 424 (49.0) | |

| Other | 78 (25.0) | 53 (6.1) | |

| NCCN Risk Group | |||

| Low risk | 120 (39.9) | 443 (52.1) | <.001 |

| Intermediate risk | 124 (41.2) | 307 (36.1) | |

| High risk | 57 (18.9) | 101 (11.9) |

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid and Veteran Affairs insurance

African-American and Caucasian men differed in the factors that influenced their treatment decision-making process (Table 2). For patients with more aggressive (intermediate/high risk) cancers, almost all AA (95.6%) and Caucasian (93.9%) men indicated curing cancer was “very important” (p=.45). The proportions of men who indicated preserving quality of life was a very important factor influencing their treatment decision-making were also similar (AA 87.9%, Caucasian 82.6%, p=.11). However, several factors were more commonly reported as important for AA men compared to Caucasian men: recovery time (80.7% AA vs. 49.5% Caucasian, p<.001), treatment time (75.7% vs. 39.0%; p<.001), impact on daily activities (73.5% vs. 57.6%; p<.001) and cost (65.8% vs. 32.1%, p<.001). The differences between AA vs. Caucasian patients in recovery time, treatment time, and cost were also observed in low-risk disease. Data for favorable intermediate-risk patients is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 2.

Percentage of patients who indicated each factor to be “very important” to treatment decision-making

| African-American | Caucasian | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| NCCN Intermediate/High Risk (N = 589) | |||

| Curing Cancer | 173 (95.6) | 383 (93.9) | .45 |

| Bowel Symptoms | 170 (93.9) | 331 (81.1) | <.001 |

| Urinary Symptoms | 162 (89.5) | 320 (78.4) | .001 |

| Preserving quality of life | 159 (87.9) | 337 (82.6) | .11 |

| Recovery Time | 146 (80.7) | 202 (49.5) | <.001 |

| Family/Friend Burden | 142 (78.5) | 294 (72.1) | .10 |

| Treatment Time | 137 (75.7) | 159 (39.0) | <.001 |

| Impact on daily activities | 133 (73.5) | 235 (57.6) | <.001 |

| Cost | 119 (65.8) | 131 (32.1) | <.001 |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 115 (63.5) | 185 (45.3) | <.001 |

| NCCN Low Risk (N = 564) | |||

| Bowel Symptoms | 113 (94.2) | 378 (85.1) | .01 |

| Urinary Symptoms | 111 (92.5) | 362 (81.5) | .003 |

| Curing Cancer | 110 (91.7) | 389 (87.6) | .26 |

| Preserving quality of life | 108 (90.0) | 382 (86.0) | .29 |

| Family/Friend Burden | 107 (89.2) | 322 (72.5) | <.001 |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 89 (74.2) | 219 (49.3) | <.001 |

| Recovery Time | 88 (73.3) | 208 (46.9) | <.001 |

| Cost | 84 (70.0) | 155 (34.9) | <.001 |

| Impact on daily activities | 83 (69.2) | 273 (61.5) | .14 |

| Treatment Time | 83 (69.2) | 150 (33.8) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Table 3 compares perceived cancer aggressiveness with actual diagnosis. For patients diagnosed with low-risk cancer, most AA and Caucasian patients perceived their cancers to be “not very aggressive” (80.3% AA vs. 77.6% Caucasian). However, there was a significant difference in perceived aggressiveness among AA and Caucasian patients with high-risk cancers. In these patients with the most aggressive type of localized prostate cancer, 53.9% of AA patients (vs. 24.0% of Caucasian patients) reported their cancers to be not very aggressive, and only 19.2% reported their cancers to be very aggressive (vs. 42.0% of Caucasian patients). Further analysis show no significant difference in the misalignment between patient perception and actual diagnosis in patients who lived in urban vs rural areas, after controlling for race (p=0.63, Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Perceived prostate cancer aggressiveness by actual diagnosis based on NCCN Risk Group

| African-American N (%) | Caucasian N (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCCN Low Risk (N=560) | |||

| Not very aggressive | 94 (80.3) | 333 (77.6) | .36 |

| Somewhat aggressive | 17 (14.5) | 82 (19.1) | |

| Very aggressive | 6 (5.1) | 14 (3.3) | |

| NCCN Intermediate Risk (N=429) | |||

| Not very aggressive | 71 (59.7) | 142 (48.0) | .09 |

| Somewhat aggressive | 41 (34.5) | 126 (42.6) | |

| Very aggressive | 7 (5.9) | 28 (9.5) | |

| NCCN High Risk (N=157) | |||

| Not very aggressive | 28 (53.9) | 14 (24.0) | <.001 |

| Somewhat aggressive | 14 (26.9) | 34 (34.0) | |

| Very aggressive | 10 (19.2) | 42 (42.0) | |

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network

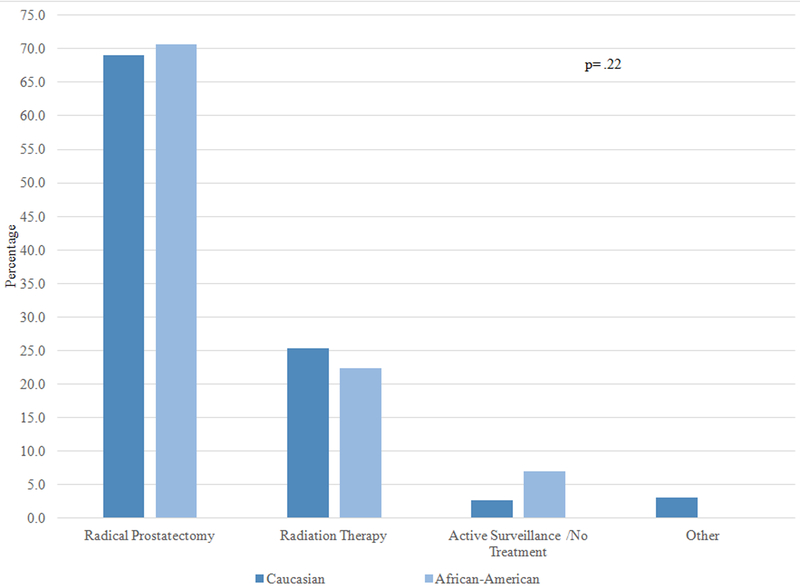

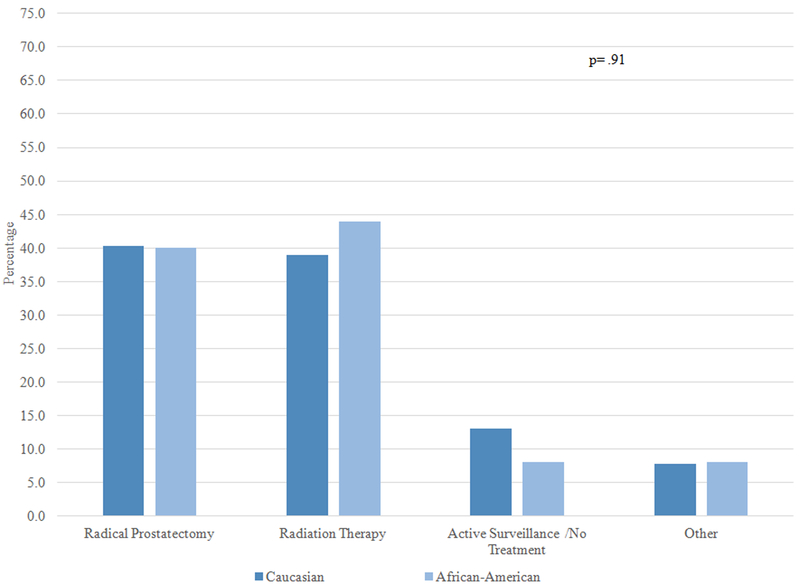

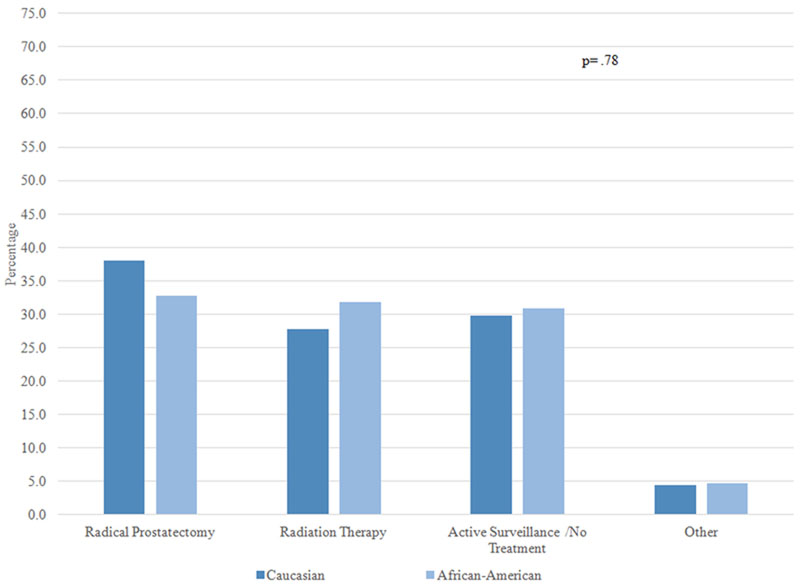

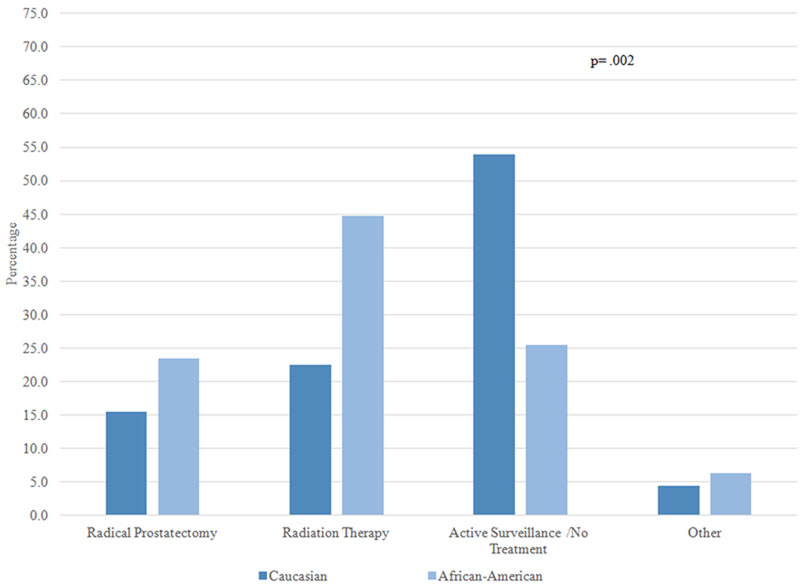

Overall, 90.1% of patients selected either “cure” or “preserving quality of life” as the most important factor impacting their treatment decision. Figure 1 examines the treatments received by AA and Caucasian patients stratified by one of these two factors, and by whether patients perceived their cancer to be aggressive or not aggressive. Among patients who perceived their cancer to be aggressive and indicated cure as the most important factor influencing their treatment decision, approximately 70% of AA and Caucasian patients chose RP and 25% chose RT; there was no significant difference in treatment by race (1A). On the other hand, among patients who perceived their cancers to be aggressive but the most important factor was preserving QOL, receipt of both RP and RT was around 40%, and there was no difference by race (1B). In patients who perceived their cancer to not be aggressive and the most important factor was cure, approximately 30–40% of patients received RP, RT, and no treatment; there was no racial difference (1C). Finally, there was a statistically significant difference in treatment selection among patients who perceived their cancer to not be aggressive and for whom preserving QOL was most important: active surveillance was the most common choice for Caucasian men (53.9%), while the most common choice for AA men was RT (44.7%) (1D).

Figure 1: Primary treatment by perception of cancer aggressiveness and top treatment priority in African-American and Caucasian patients.

Figure 1A: Patients who perceived their cancer as aggressive and the most important factor was cure (N=291)

Figure 1B: Patients who perceived their cancer as aggressive and the most important factor was quality of life (N=102)

Figure 1C: Patients who perceived their cancer as not aggressive and the most important factor was cure (N=405)

Figure 1D: Patients who perceived their cancer as not aggressive and the most important factor was quality of life (N=216)

Table 4 summarizes multivariable models examining factors associated with treatment selection. Perceived cancer risk appears to be the dominant factor associated with whether patients received treatment vs no treatment. Patients’ stated importance for curing the cancer was also a significant factor for receiving treatment (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.46–4.18). After adjusting for these and sociodemographic factors, there was no difference between AA and Caucasian patients in receiving treatment (OR for Caucasian 1.13, 95% CI .77–1.68). Stratified models by NCCN risk group did not change these results (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 4.

Logistic regression models: Factors associated with treatment vs. no treatment, and radical prostatectomy vs. radiation therapy

| Treatment vs. No Treatment* | Radical Prostatectomy vs. Radiation Therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Race (REF=African-American) | ||||

| Caucasian | 1.13 | .77 – 1.68 | 1.29 | .86 – 1.93 |

| Perceived Aggressiveness (REF=not very) | ||||

| Very | 13.76 | 4.11 – 46.10 | 4.66 | 2.49 – 8.70 |

| Somewhat | 4.95 | 3.15 – 7.79 | 1.65 | 1.15 – 2.36 |

| Most important decision-making factor (REF=all other) | ||||

| Cure | 2.47 | 1.46 – 4.18 | 4.50 | 2.25 – 9.01 |

| Preserving quality of life | 1.07 | .62 – 1.85 | 2.11 | 1.01 – 4.41 |

| Age | 0.93 | .90 – .96 | 0.91 | .88 – .94 |

| Marital Status (REF=married) | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.96 | .63 – 1.47 | 0.92 | .60 – 1.40 |

| Insurance (REF=other) | ||||

| Public** | 0.91 | .39 – 2.14 | 1.30 | .61 – 2.76 |

| Private | 0.82 | .35 – 1.94 | 1.35 | .63 – 2.89 |

| Employment Status (REF=retired) | ||||

| Full time | 0.83 | .53 – 1.30 | 1.55 | .98 – 2.46 |

| Other | 1.15 | .72 – 1.84 | 0.76 | .48 – 1.20 |

| NCCN Risk Group (REF=Low Risk) | ||||

| Intermediate Risk | 4.76 | 3.23 – 7.02 | 1.28 | .89 – 1.85 |

| High Risk | 2.88 | 1.57 – 5.28 | 0.80 | .47 – 1.35 |

Abbreviations: OR: Odds Ratio. CI: Confidence Intervals.

Treatment included radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy and brachytherapy within 12 months of diagnosis.

Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid and Veteran Affairs insurance

Similar findings were seen in the second multivariable model. Among patients who received treatment, a perception of more aggressive cancer and priority for curing the cancer were associated with higher odds of receiving RP vs. RT, and no racial difference was seen after adjusting for these and other covariates.

DISCUSSION

The large racial disparity in prostate cancer mortality outcomes is multifactorial. Prior studies have demonstrated that AA men are 2 times more likely than Caucasian men to die from prostate cancer1, and this is likely related to differences in screening,19,20 timeliness of treatment,4,10 and receipt of and aggressiveness of treatment.2,5,6,21 However, with the exception of a few, small retrospective focus group studies,12,14 reasons for racial differences in treatment selection have not been examined. To address this knowledge gap, we examined a population-based prospective observational cohort of AA and Caucasian prostate cancer patients and their perceptions of cancer aggressiveness, stated important factors in the treatment decision-making process, and primary treatment received. Several findings from this study reveal novel insights into the observed racial disparities in prostate cancer treatment, and as a result provide potential targets for intervention to reduce these disparities.

First, AA men were more likely than Caucasian men to incorrectly perceive their cancer to be not aggressive when diagnosed with high-risk disease. More than half of AA men with this most aggressive form of localized prostate cancer reported that their cancer was “not very aggressive,” compared to 24% of Caucasian men. At the same time, among all AA and Caucasian men who perceived their cancers to be aggressive, there were no racial difference in treatment received. Taken together, these findings suggest that the misalignment between perceived cancer aggressiveness and actual diagnosis among AA and Caucasian men may contribute to the differences in treatments described by prior studies.2,5,11

Results from the multivariable analysis support these findings, and demonstrated that the overwhelming factor influencing patients’ receipt of treatment (treatment vs no treatment), and the aggressiveness of treatment (RP vs. RT), was perception of cancer aggressiveness. Given the observed differences in perception of cancer aggressiveness among AA and Caucasian patients, and that this perception is strongly associated with treatment receipt – improved physician/patient communication to increase patient understanding of diagnosis, possibly with the use of a decision aid,22 may be a promising intervention to study as a potential mechanism to reduce disparities in treatment.

Prior studies have shown that AA patients have shorter, less informational consultations,23,24 are offered fewer treatment options,25–27 and are less likely to have racially/culturally concordant consultations.23,28 The lack of diversity in treating specialists may be a contributor to the imbalance in patient understanding of disease risk found in the current study.

Second, while both AA and Caucasian men considered cure and preserving QOL to be highly important, AA men were more likely than Caucasian men to also prioritize additional factors in their treatment decision-making process including cost, treatment time, and recovery time. These differences were dramatic; for example, while 65–70% of AA men indicated cost of treatment to be a “very important” consideration, only 32–35% of Caucasian men reported the same. Thus, it appears that the decision-making process for AA men may be more multifactorial than Caucasian men. These findings are consistent with a prior study, which also showed that AA men were more concerned with socioeconomic factors than their Caucasian counterparts.8 However, very few studies before the current report have investigated the diverse multitude of factors involved in treatment selection in prostate cancer.

The issue of financial toxicity has become increasingly relevant, as the rising costs of cancer treatment have been associated with a negative impact on cancer treatment compliance and patient outcomes.29–33 The financial burden of cancer treatment to patients can be substantial, and includes not only out-of-pocket expenses but also loss of income from missing work; it can also impact work of family members.34,35 Our results suggest that these issues disproportionally affect AA patients, who were significantly more likely to indicate that the factors of cost, treatment time and recovery time were very important. Accordingly, these findings suggest that aligning perceived cancer aggressiveness with actual diagnosis is only part of the problem, and addressing financial issues including treatment feasibility as it pertains to employment and affordability issues is another possible target for intervention to reduce prostate cancer disparities.

This study has a number of potential strengths and limitations. This study was a population-based, prospective cohort, and enrolled patients from small and large communities throughout North Carolina – which improves the generalizability of results compared to institutional studies; however, it is unknown if these results apply to patients outside the state. Due to the limited research in this area, there were no validated surveys that could be used to assess patient perception of aggressiveness and important factors in their decision-making process. The limitation is complemented by the ability of this study to provide novel insights in this understudied area regarding a commonly described problem.

CONCLUSION

In a population-based, diverse cohort of AA and Caucasian patients with newly-diagnosed prostate cancer, this study found that more AA than Caucasian men with aggressive, high-risk prostate cancer diagnoses incorrectly perceived their cancers to be not aggressive; further, patients who perceived their cancers to be not aggressive were less likely to receive treatment. In addition, while both AA and Caucasian patients indicated that curing the cancer was highly important, several additional factors were important for AA patients including cost, treatment time, and recovery time. These insights provide potential targets for intervention to reduce the well-known racial disparities in treatment, and potential mortality, in this disease.

Supplementary Material

Funding Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) grant CER-1310–06453 and a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; and the University Cancer Research Fund via the state of North Carolina.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD,. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moses KA, Paciorek AT, Penson DF, Carroll PR, Master VA. Impact of ethnicity on primary treatment choice and mortality in men with prostate cancer: data from CaPSURE. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(6):1069–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaston KE, Kim D, Singh S, Ford OH, 3rd, Mohler JL. Racial differences in androgen receptor protein expression in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;170(3):990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stokes WA, Hendrix LH, Royce TJ, et al. Racial differences in time from prostate cancer diagnosis to treatment initiation: a population-based study. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2486–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Ziehr DR, et al. Trends in disparate treatment of African American men with localized prostate cancer across National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk groups. Urology. 2014;84(2):386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Presley CJ, Raldow AC, Cramer LD, et al. A new approach to understanding racial disparities in prostate cancer treatment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tewari AK, Gold HT, Demers RY, et al. Effect of socioeconomic factors on long-term mortality in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2009;73(3):624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J, Janisse J, Ruterbusch J, Ager J, Schwartz KL. Racial Differences in Treatment Decision-Making for Men with Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: a Population-Based Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(1):35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrington WE, Schenk JM, Etzioni R, et al. Difference in Association of Obesity With Prostate Cancer Risk Between US African American and Non-Hispanic White Men in the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(3):342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid M, Meyer CP, Reznor G, et al. Racial Differences in the Surgical Care of Medicare Beneficiaries With Localized Prostate Cancer.JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moses KA, Orom H, Brasel A, Gaddy J, Underwood W, 3rd. Racial/Ethnic Disparity in Treatment for Prostate Cancer: Does Cancer Severity Matter? Urology. 2017;99:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman DB, Thomas TL, Owens OL, Hebert JR. It takes two to talk about prostate cancer: a qualitative assessment of African American men’s and women’s cancer communication practices and recommendations. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(6):472–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobran EK, Wutoh AK, Lee E, et al. Perceptions of prostate cancer fatalism and screening behavior between United States-born and Caribbean-born Black males. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(3):394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman DB, Corwin SJ, Rose ID, Dominick GM. Prostate cancer communication strategies recommended by older African-American men in South Carolina: a qualitative analysis. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(3):204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spain P, Carpenter WR, Talcott JA, et al. Perceived family history risk and symptomatic diagnosis of prostate cancer: the North Carolina Prostate Cancer Outcomes study. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2180–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeSantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):151–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen RC, Carpenter WR, Kim M, et al. Design of the North Carolina Prostate Cancer Comparative Effectiveness and Survivorship Study (NC ProCESS). J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Guidelines Prostate Cancer. 2017.

- 19.Mahal BA, Chen YW, Muralidhar V, et al. Racial disparities in prostate cancer outcome among prostate-specific antigen screening eligible populations in the United States.Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2017;28(5):1098–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legler JM, Feuer EJ, Potosky AL, Merrill RM, Kramer BS. The role of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing patterns in the recent prostate cancer incidence decline in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(5):519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underwood W, De Monner S, Ubel P, Fagerlin A, Sanda MG, Wei JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the treatment of localized/regional prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004;171(4):1504–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(10):CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr., Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(3):355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AM, Billingsley KG, Hayanga AJ, Matthews B, Baldwin LM, Birkmeyer JD. Residual treatment disparities after oncology referral for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(10):738–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson DR, Martinez ME, Gupta S, et al. Racial disparity in consultation, treatment, and the impact on survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(23):1814–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy MM, Simons JP, Ng SC, et al. Racial differences in cancer specialist consultation, treatment, and outcomes for locoregional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(11):2968–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muniz R, et al. The Effects of Race and Racial Concordance on Patient-Physician Communication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(9):980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, Fuld Nasso S, Saltz LB. How Should We Intervene on the Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care? One Shot, Four Perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glode AE, May MB. Rising Cost of Cancer Pharmaceuticals: Cost Issues and Interventions to Control Costs.Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(1):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard DH, Molinari NA, Thorpe KE. National estimates of medical costs incurred by nonelderly cancer patients. Cancer. 2004;100(5):883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Sabatino SA, Richardson LC. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(11):801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.