Abstract

Background

Candida is an important cause of infections in premature infants. Gastrointestinal colonization with Candida is a common site of entry for disseminated disease. The objective of this study was to determine whether a dietary supplement of medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) reduces Candida colonization in preterm infants.

Methods

Preterm infants with Candida colonization (n=12) receiving enteral feedings of either infant formula (n=5) or breastmilk (n=7) were randomized to MCT supplementation (n=8) or no supplementation (n=4). Daily stool samples were collected to determine fungal burden during a 3 week study period. Infants in the MCT group received supplementation during 1 week of the study period. The primary outcome was fungal burden during the supplementation period as compared to the periods before and after supplementation.

Results

Supplementation of MCT led to a marked increase in MCT intake relative to unsupplemented breast milk or formula as measured by capric acid content. In the treatment group, there was a significant reduction in fungal burden during the supplementation period as compared to the period before supplementation (RR = 0.15, p = 0.02), with a significant increase after supplementation was stopped (RR = 61, p < 0.001). Fungal burden in the control group did not show similar changes.

Conclusions

Dietary supplementation with MCT may be an effective method to reduce Candida colonization in preterm infants.

Keywords: Medium-chain Triglycerides, Candida, Neonate, Prematurity

Introduction

While Candida species are commonly found as commensal, colonizing organisms in immunocompetent individuals, newborn infants are a unique population at risk for severe Candida infection. Term infants commonly develop mucocutaneous disease, such as diaper dermatitis or oral thrush. However, infants born preterm, in part due to immaturity of the developing immune system, are susceptible to invasive disease. Disseminated candidiasis is a particularly morbid etiology of late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight infants. In one large series, the mortality rate of all infants affected by invasive candidiasis was 32%.(1) However, if the etiologic organism was Candida albicans, the mortality rate reached as high as 44%. Additionally, among survivors of invasive candidiasis, the rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment is high.(2)

Given the high morbidity and mortality rates among affected infants, strategies for prevention of infection have received considerable attention. Risk factors for development of disseminated disease include: low birth weight, gestational age at birth less than 32 weeks, vaginal delivery, use of central catheters, hyperalimentation, use of H2 blockers, postnatal steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics including third generation cephalosporins.(3–6) In recent years, preventative strategies have focused on those risk factors that are modifiable such as improved central line care, more judicious use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and use of prophylaxis with anti-fungal agents including fluconazole and/or nystatin.(7) These measures likely resulted in a decrease in rates of invasive disease despite increased survival rates of very low birth weight infants.

Another potentially modifiable risk factor for the development of disseminated disease is colonization of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with Candida. GI colonization occurs commonly in infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), most frequently with C. albicans, followed by C. parapsilosis. (8) Further, up to 45% of infants with invasive disease have GI colonization with Candida prior to the onset of dissemination, and invasive infection by the colonizing strain has been well documented.(9) Of those who had GI cultures available, 40% had the same Candida strain isolated from both the GI tract and the blood. Therefore, reducing gastrointestinal colonization represents an important strategy for reducing rates of invasive disease in preterm infants.

Fluconazole prophylaxis is effective in reducing invasive candidiasis and in preventing Candida colonization in very low birth weight infants in neonatal intensive care units.(10, 11) However, it appears less effective in eliminating colonization once it occurs and therefore may not ultimately modify the relationship between colonization and subsequent development of invasive disease.(11) Additionally, the degree of exposure and duration of treatment raises concern for development of antifungal resistance. Though trials have not shown emergence of resistance in the face of prophylactic dosing, no study has been powered to specifically look at this outcome. Importantly, prolonged drug exposure also places infants at risk for toxicities. To mitigate these risks, current recommendations suggest fluconazole in neonates with birth weights <1000 grams who are cared for in nurseries with high rates (>10%) of invasive candidiasis.(12) Alternative strategies continue to be sought which will reduce both colonization and invasive disease and avoid risks associated with the use of anti-fungal agents. Administration of lactoferrin holds promise as one such strategy, and has been shown to reduce invasive disease, albeit without a detectable decrease in GI colonization.(13)

In a well-established adult murine model of gastrointestinal colonization with Candida albicans, dietary fatty acids were found to have a significant impact on colonization.(14) Specifically, a diet containing coconut oil, which is high in medium-chain fatty acids, reduced the ability of C. albicans to establish colonization and reduced fungal burden in mice previously colonized with C. albicans. Moreover, a diet containing coconut oil together with beef tallow, which is high in long-chain fatty acids, still led to reduced colonization as compared to a diet containing only beef tallow. These data suggest that a change in the fatty acid composition of GI contents promoted by coconut oil may directly inhibit the establishment of colonization by Candida, and led to speculation that dietary supplementation with medium-chain fatty acids, in the form of medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil, would reduce GI colonization and thus invasive disease in humans. MCT oil has been a component of infant formulas for decades. It is also used as a dietary supplement in NICUs for improved nutrition in very low birth weight infants. MCT oil is thus known to be safe for administration to infants. Here, the hypothesis that dietary supplementation with medium-chain triglycerides will reduce the amount of Candida in the intestinal tracts of preterm infants was tested in a pilot study.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Eligibility

This pilot, open-label, randomized controlled trial included premature infants admitted to the NICU at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island who were screened for GI Candida colonization from June 2014 - December 2015. Infants were eligible for screening if they were born prematurely (< 37 weeks gestational age), were receiving full volume fortified enteral feedings and had an anticipated stay of at least 3 weeks. Exclusion criteria included: gestational age > 37 weeks, current receipt of parenteral nutrition or MCT oil, current or past exposure to anti-fungal medications, presence of a GI anomaly or stoma, or an anticipated stay of less than 3 weeks. The study was reviewed and approved by the Women & Infants Hospital Institutional Review Board and was performed under IND 121549 from the United States Food and Drug Administration. This study describes the use of MCT oil to reduce Candida colonization. This product is not labeled for prevention or treatment of disease.

Study Procedures

A stool sample was cultured from each eligible infant on yeast extract, peptone, dextrose (YPD) agar media (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 2% agar) containing streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml). Microbes grown from positive stool cultures were evaluated by microscopy to verify the presence of yeast. Parents of infants whose stool cultures yielded any detectable Candida were then approached for informed consent. Once informed consent was obtained, stools were sampled daily for 3 days to establish baseline colonization. Samples were weighed, suspended in sterile saline, diluted serially and cultured on YPD agar media containing streptomycin and ampicillin. All samples were processed within 24 hours, a time period previously determined to have no effect on colony counts. Presence and concentration of organisms was recorded in colony forming units per gram (cfu/g) of stool. Speciation of Candida was determined using the Vitek-2 system (bioMérieux, Durham, NC) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Infants who had cleared their stool colonization, defined as a colony count of less than 100 colony forming units (cfu) per gram, during the 3 days of baseline stool sampling were excluded from the remainder of the study. Infants were randomized to MCT oil supplementation or no supplementation groups through the use of sequentially-numbered opaque sealed envelopes. Infants were randomized to either receive supplemental dietary MCT oil (Nestlé Health Science, Vevey, Switzerland) at a dose of 0.5 mL/oz (4 kcal/oz) over the course of a 7 day period or no supplement. Neither staff nor family members were blinded to study group assignment. Infants in the NICU preferentially receive mother’s own breast milk supplemented with bovine-based fortifiers when available. This milk is provided either fresh or thawed from frozen supplies. Commercial preterm formula (Similac® Special Care or Enfamil® Premature) was used when mother’s breast milk was not available. Type, amount and caloric density of feedings was determined by the clinical team caring for each infant. Daily stool samples, as available, were collected during the treatment period and for up to 10 days after discontinuation of supplementation. For infants receiving maternal breast milk, a daily sample of breast milk was collected for fatty acid analysis. For formula fed infants, type and caloric density of formula was recorded. Additionally, selected demographic data were obtained from each enrolled infant’s medical record.

Safety Monitoring

Infants were followed closely by study personnel for any signs of intolerance. Predefined signs of intolerance included feeding intolerance, defined as any clinical event related to feeding (gastric aspirates, emesis, abdominal distension) that results in a reduction or withholding of enteral feedings for a period of 24 hours or more; diarrhea; necrotizing enterocolitis; poor weight gain; or excessive weight gain. No signs of intolerance, adverse events, or safety concerns were identified for any subjects throughout the study.

Fatty Acid Analysis

Representative breast milk samples obtained from infants receiving breast milk before and after the supplementation period were subjected to fatty acid analysis. Breast milk lipids were extracted after the addition of an internal standard (C17:0),(15) followed by saponification and methylation.(16) The resulting fatty acid methyl esters (FAME’s) were analyzed using an established gas chromatography method.(17) Peaks of interest were identified by comparison with authentic fatty acid standards (Nu-Chek Prep, Inc. MN) and expressed as mg/ml. Capric acid (C10:0) was used as a proxy for total medium chain fatty acids. The amount of capric acid added to supplemented infants was calculated based on the known content in the MCT oil supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics and morbidities were compared between groups using Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Fungal burden counts were compared between groups using negative binomial regression within time period (before, during, after) with generalized estimating equations adjustment for multiple measures per individuals within time. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Study Population Demographics

Two hundred thirty seven infants were screened for inclusion during the study period (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Of these, 43 (18%) were colonized with Candida. Seventeen infants were enrolled during the study period; 6 infants were randomized to no supplementation and 11 infants were randomized to MCT oil supplementation. Two infants in the control group and 3 infants in the supplementation group were excluded from subsequent analysis because stool colonization had cleared after screening and before MCT treatment. Timing of enrollment for each subject is depicted in Supplemental Digital Content 2 (table). Demographic characteristics are depicted in Supplemental Digital Content 3 (table). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were detected between groups. The percentage of infants who received breast milk versus formula was similar, as was duration of TPN receipt. No infants received antacids during the study period. Duration of antibiotic treatment was comparable and no infants received third-generation cephalosporins.

Candida species

There were a variety of Candida species that colonized the gastrointestinal tracts of enrolled infants (Table 1). Candida albicans was the most common species colonizing infants enrolled in the MCT oil supplementation group; while Candida parapsilosis was most common in infants randomized to receive no supplementation. Additional colonizing species were Candida lusitaniae and Candida rugosa.

Table 1.

Colonizing Candida species of enrolled subjects

| MCT oil supplement (n=8) | No supplement (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans, n | 5 | 1 |

| Candida parapsilosis, n | 0 | 2 |

| Candida lusitaniae, n | 2 | 1 |

| Candida rugosa, n | 1 | 0 |

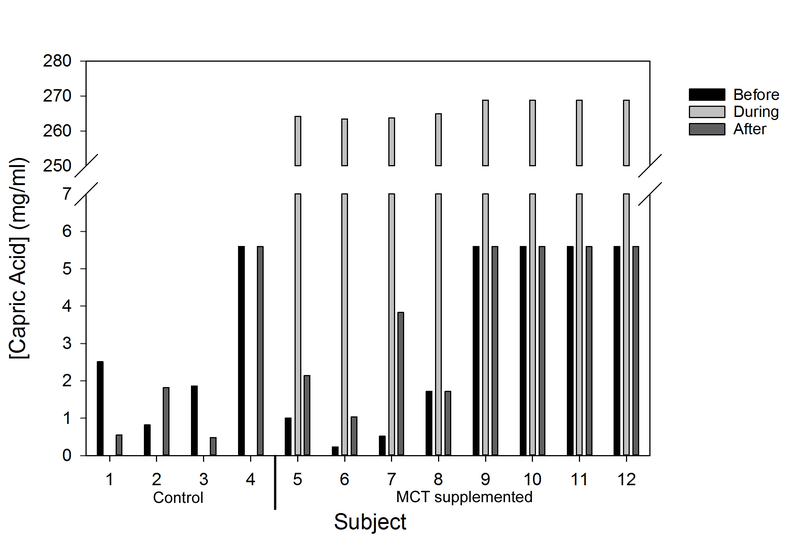

Total Dose of Medium-Chain Triglycerides Received

For breast milk fed infants, the fatty acid composition of breast milk samples before and after the supplementation period was determined by fatty acid analysis. Information on the fatty acid content of commercial formulas is available. To compare the medium chain fatty acid contents of feeds given to infants, capric acid, a medium chain fatty acid (C10) that comprises 28% of the supplemented MCT oil, was used as a proxy for total medium chain fatty acids. The amount of capric acid received by all infants before and after the supplementation period and the calculated additional capric acid received by supplemented infants is depicted in Figure 1. Regardless of whether the infant received breast milk or formula feeds, the MCT oil dose (4 kcal/oz) provided a substantially increased level of dietary capric acid during the supplementation period. This increase was detected irrespective of the prescribed caloric density of the feeds.

Figure 1.

Total capric acid received per subject per mL of feeding before, during and after MCT oil supplementation. Subjects 1–4 were in the control group and subjects 5–12 received MCT supplementation. Subjects 4 and 9–12 received formula feedings. Fatty acid composition of feeds given to infants at various times were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

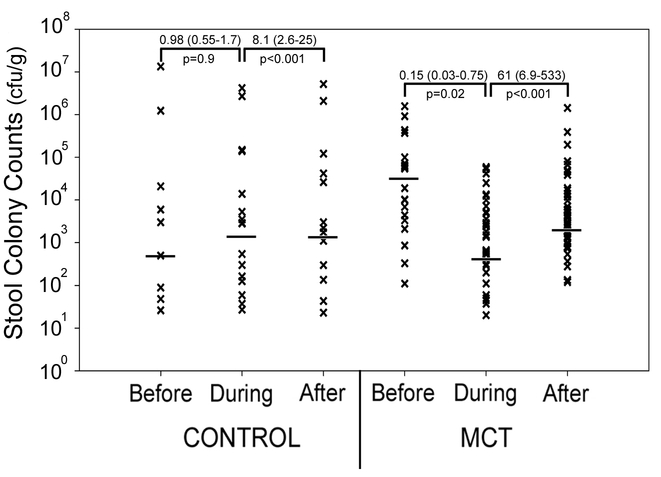

Gastrointestinal Fungal Burden

Overall infant stool fungal burden by time period throughout the study duration is depicted in Figure 2. To estimate the direction and magnitude of the effect of MCT supplementation on stool fungal burden while accounting for multiple measures from each individual, a longitudinal generalized estimating equations model using a negative binomial distribution was applied to determine the rate ratio (RR) reflecting the change in stool colony counts between time periods. Day was included in the model to adjust for possible temporal processes affecting colony counts (p < 0.001). Compared to the period before supplementation, colony counts during the supplementation period were significantly lower in those infants who received MCT oil (RR = 0.15, p = 0.02). Colony counts in the period after supplementation increased compared to those during supplementation (RR = 61, p < 0.001). In the control group no change in colony counts was detected in the “during” period (RR = 0.98, p = 0.9), while there was an increase of smaller magnitude comparing the period “during” to “after” (RR = 8.1, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Fungal burden per study period. Shown are individual colony counts, in colony forming units per gram of stool, for enrolled subjects during each study time period. Each symbol indicates results from a single stool sample. The bar represents median count. Rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) are depicted to reflect the direction and magnitude of change in stool colony counts between time periods for each group.

To assess the changes in fungal counts in each individual subject, the average colony counts in the time periods before and during supplementation were determined for each subject, and the fold change for each individual during the supplementation period was calculated relative to the period before supplementation. On average, infants in the control group increased their colony count during the “supplementation” period by 3-fold, whereas the MCT treated group had an average 84% reduction in colony counts.

Comorbidities

A between-group comparison of comorbidities is depicted in Table 2. No infants had sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis. Other morbidities were similar between groups. Chronologic age and corrected gestational age at discharge or transfer were likewise similar between groups. One infant in the MCT oil supplementation group was transferred to an outside facility at 32 weeks corrected gestational age. All enrolled infants survived to discharge or transfer.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for comorbidities of enrolled subjects

| MCT oil supplement (n=8) | No supplement (n=4) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

| NEC, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

| PDA, n (%) | 1 (12) | 1 (25) | 1.00 |

| Any IVH, n (%) | 2 (25) | 1 (25) | 1.00 |

| IVH – Grades 3 and 4, n (%) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.52 |

| PVL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

| Any ROP, n (%) | 3 (37) | 2 (50) | 1.00 |

| BPD, n (%) | 7 (87) | 2 (50) | 0.24 |

| Length of stay, days | 110 (51–152) | 87 (28–134) | 0.29 |

| Chronologic age at D/C or transfer, wk | 15.7 (7–21) | 12.5 (4–19) | 0.56 |

| Corrected age at D/C or transfer, wk* | 41 (32–46) | 40.3 (36–45) | 0.80 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

One infant from supplement group was transferred to another facility at 32 weeks corrected age

NEC – Necrotizing enterocolitis; PDA – Patent ductus arteriosus; IVH – Intraventricular hemorrhage; PVL – Periventricular leukomalacia; ROP – Retinopathy of prematurity; BPD – Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; D/C - Discharge

Discussion

Candida colonization of the GI tract in premature infants frequently precedes the development of invasive disease.(9) The GI tract is uniquely accessible to an oral therapy that could act directly to eliminate colonization, obviating the need for systemic therapy. The use of oral nystatin to reduce colonization has suggested that such an approach can be effective.(18, 19) Although pilot in nature, our study provides preliminary evidence that the use of nutritional supplementation with oral medium-chain triglycerides may be an effective approach to reduce GI Candida colonization in preterm neonates while avoiding exposure to pharmaceutical agents.

Studies of the acquisition of Candida colonization over time suggest that a preterm infant remains at risk for colonization throughout the duration of his/her admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.(20, 21) Colonization with C. albicans occurring within the first week of life represents vertical transmission from mother to infant, whereas colonization occurring after week 2 or with non-albicans species most likely occurs through horizontal transmission.(22) Additionally, breast milk represents a unique exposure to neonates and colonization of breast milk with Candida spp. has been linked to yeast colonization in infants.(23) As such, breast milk serves as a potential ongoing yeast exposure for infants throughout the neonatal period. Therefore, any effective prophylactic regimen meant to prevent or eliminate gastrointestinal colonization likely requires ongoing administration. A non-pharmacologic therapy based on administering a supplement with a well-established safety profile, such as MCT oil, is an attractive and cost-effective option.

The mechanism of action by which MCTs exert an effect on Candida is not fully elucidated. Incubation of C. albicans in the presence of medium-chain fatty acids in vitro, in particular capric acid, results in disruption of the plasma membrane leading to disorganization of the cytoplasm and ultimately to cell death.(24) These findings suggest a direct cytotoxic effect of MCT on fungal cells. Other potential effects of capric acid on C. albicans virulence include reduction in hyphae formation, adhesion and biofilm formation.(25) Additional evidence from a murine model of C. albicans colonization points to an indirect effect through a reduction in the availability of long-chain fatty acids in the GI tracts of mice fed a diet high in medium-chain fatty acids. This reduction in long-chain fatty acids may inhibit GI colonization by C. albicans due to reduced energy sources.(14)

A potential advantage of MCT oil over chemoprophylaxis for Candida colonization is its apparent efficacy across Candida species. Fifty-two Candida isolates from clinical specimens representing 6 different species were tested for their susceptibility to either coconut oil or fluconazole.(25) All species were sensitive to coconut oil, whereas 8% of isolates were resistant to fluconazole at the highest concentration tested (128 μg/ml). Even species intrinsically resistant to fluconazole demonstrated some susceptibility to coconut oil in this series. Our data are consistent with these observations; MCT oil was effective in patients regardless of the colonizing species. However, the species of Candida colonizing infants in the control group were largely non-albicans species while more than half of the MCT supplemented infants were colonized with C. albicans. Differing species between groups may confound our results.

While our findings are consistent with those found in the mouse model of C. albicans colonization, there are limitations to our study. The reduction in GI Candida colonization seen is potentially multifactorial. The diet provided to enrolled infants was not standardized and therefore heterogeneity in nutrition may exert its own effect on colonization outside of the contribution of MCT oil supplementation alone. We did not explore dose as a variable and our sample size was small. Therefore, although our results showed that MCT oil supplementation was well tolerated and appeared to be efficacious in reducing GI colonization, additional study is required to determine which Candida species are affected as well as optimal dosage and timing. Further, a larger prospective randomized controlled trial will be needed to confirm that MCT supplementation reduces colonization and to determine whether supplementation ultimately reduces the more important outcome of rates of invasive candidiasis in preterm infants. Of note, no adverse effect of MCT supplementation was observed in our study cohort, although the study was not adequately powered to assess safety. Length of stay was 23 days longer in the supplementation group. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it most likely reflects an earlier mean gestational age in this group (25.5 vs. 27.8 weeks) rather than an effect of MCT exposure.

In summary, our findings indicate that dietary supplementation with MCT may be an effective non-pharmacological method to reduce Candida colonization in the GI tracts of preterm infants. This reduction in GI colonization may ultimately lead to a reduction in the rate of invasive candidiasis in a high-risk population of newborns.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1 (figure). Flow diagram for subject screening and enrollment.

Supplemental Digital Content 2 (table). Enrollment

Supplemental Digital Content 3 (table). Univariate analysis for demographic factors of enrolled subjects

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Lauro for assistance in speciation of Candida isolates and Audrey Goldbaum for the fatty acid analysis of the breast milk samples in the Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory (HNRCA). We also appreciate the assistance of the nurses in the NICU in sample collection. We thank Dr. Damian Krysan for critical insights that stimulated the inception of this project. We gratefully acknowledge support from the Tufts CTSI (National Center for Research Resources Award Number UL1RR025752) that was provided at an early stage of this work. KTWG (K12GM074869) and JMB (P20GM103537 and P20GM104317) were supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). CAK was partially supported by grants R01AI081794 and R01AI118898 from the NIH. ESV was supported by the Alpert Medical School Summer Assistantship program. Work in the Bliss laboratory was also supported by funds from the William and Mary Oh – William and Elsa Zopfi Professorship for Pediatrics and Perinatal Research from Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: KTWG (K12GM074869) and JMB (P20GM103537 and P20GM104317) were supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). CAK was partially supported by grants R01AI081794 and R01AI118898 from the NIH. ESV was supported by the Alpert Medical School Summer Assistantship program. Work in the Bliss laboratory was also supported by funds from the William and Mary Oh – William and Elsa Zopfi Professorship for Pediatrics and Perinatal Research from Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest or funding to disclose.

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin DK Jr., Stoll BJ, Fanaroff AA, et al. Neonatal candidiasis among extremely low birth weight infants: risk factors, mortality rates, and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 22 months. Pediatrics. 2006;117:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin DK Jr., Smith PB, Arrieta A, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of repeat-dose micafungin in young infants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feja KN, Wu F, Roberts K, et al. Risk factors for candidemia in critically ill infants: a matched case-control study. J Pediatr. 2005;147:156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manzoni P, Farina D, Leonessa M, et al. Risk factors for progression to invasive fungal infection in preterm neonates with fungal colonization. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2359–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, Hornik CP, Benjamin DK Jr., et al. Risk factors for invasive candidiasis in infants >1500 g birth weight. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aliaga S, Clark RH, Laughon M, et al. Changes in the incidence of candidiasis in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics. 2014;133:236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saiman L, Ludington E, Dawson JD, et al. Risk factors for Candida species colonization of neonatal intensive care unit patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:1119–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saiman L, Ludington E, Pfaller M, et al. Risk factors for candidemia in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit patients. The National Epidemiology of Mycosis Survey study group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1660–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Pugni L, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of prophylactic fluconazole in preterm neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2483–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Messner H, et al. Bovine lactoferrin prevents invasive fungal infections in very low birth weight infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunsalus KT, Tornberg-Belanger SN, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH, Kumamoto CA. Manipulation of host diet to reduce gastrointestinal colonization by the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. mSphere. 2016;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison WR, Smith LM. Preparation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters and Dimethylacetals from Lipids with Boron Fluoride--Methanol. J Lipid Res. 1964;5:600–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthan NR, Ip B, Resteghini N, Ausman LM, Lichtenstein AH. Long-term fatty acid stability in human serum cholesteryl ester, triglyceride, and phospholipid fractions. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2826–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aydemir C, Oguz SS, Dizdar EA, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prophylactic fluconazole versus nystatin for the prevention of fungal colonisation and invasive fungal infection in very low birth weight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011;96:F164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell A, Isaacs D, Halliday R. Oral nystatin prophylaxis and neonatal fungal infections. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang YC, Li CC, Lin TY, et al. Association of fungal colonization and invasive disease in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibovitz E, Livshiz-Riven I, Borer A, et al. A prospective study of the patterns and dynamics of colonization with Candida spp. in very low birth weight neonates. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bliss JM, Basavegowda KP, Watson WJ, Sheikh AU, Ryan RM. Vertical and horizontal transmission of Candida albicans in very low birth weight infants using DNA fingerprinting techniques. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow BDW, Reardon JR, Perry EO, et al. Expressed Breast Milk as a Predictor of Neonatal Yeast Colonization in an Intensive Care Setting. J Ped Infect Dis. 2014;3:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergsson G, Arnfinnsson J, Steingrimsson O, Thormar H. In vitro killing of Candida albicans by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3209–3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogbolu DO, Oni AA, Daini OA, Oloko AP. In vitro antimicrobial properties of coconut oil on Candida species in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Med Food. 2007;10:384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1 (figure). Flow diagram for subject screening and enrollment.

Supplemental Digital Content 2 (table). Enrollment

Supplemental Digital Content 3 (table). Univariate analysis for demographic factors of enrolled subjects