Abstract

Indoor tanning leads to melanoma, the fifth most common cancer in the U.S. The highest rate of indoor tanning is among young women whose exposure to tanned images in the media is linked to protanning attitudes. This study evaluated the efficacy of a media literacy intervention for reducing young women’s indoor tanning. Intervention participants analyzed the content and functions of the media influencing protanning attitudes and produced counter-messages to help themselves and peers resist harmful media effects. The message production was of two types: digital argument production or digital story production. The control group received assessments only. This three-group randomized design involved 26 sorority chapters and 247 members in five Midwestern states where indoor tanning is prevalent. At 2- and 6-month follow-up assessments, those in the two intervention conditions were less likely to be indoor tanners (p = .033) and reported lower indoor tanning intentions (p = .002) compared to those in the control condition. No difference between the two intervention groups was found for behavior. Although the argument group exhibited slightly weaker indoor tanning intentions than the story group, the difference was not significant. The results provide the first evidence of the efficacy of a media literacy intervention for indoor tanning reduction. Implications for participative engagement interventions are discussed.

Keywords: indoor tanning, melanoma, media literacy, participative engagement

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the United States (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2018) and the risk of melanoma is significantly associated with the exposure to artificial ultraviolet rays of indoor tanning (Ting, Schultz, Cac, Peterson, Walling, 2007; Westerdahl et al., 1994; Westerdahl, Ingvar, Masback, Jonsson, Olsson, 2000). Among 18–29 year olds, ten or more lifetime indoor tanning sessions increase the risk of melanoma by 6.5 times, with over 75% of melanoma in ages 18 to 29 associated with indoor tanning behavior (Cust et al., 2011).

Indoor tanners are predominantly young women (Demko, Borawski, Debanne, Cooper, Stange, 2003) and more young women than men are diagnosed with melanoma (Robinson, Kim, Rosenbaum, & Ortiz, 2008). Melanoma is one of the most prevalent cancers in women younger than 30 (American Cancer Society, 2017). Nationwide, the highest rates of indoor tanning are found among young women aged 18–25 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

Media are an important source of socially constructed perceptions about risk behavior (Fishbein & Yzer, 2003). Research has found that the media depict tanned looks positively for young women (Cho, Hall, Kosmoski, Fox, & Mastin, 2010) and that exposure to protanning media is linked to protanning beliefs and indoor tanning tendencies among young women (Stapleton, Hillhouse, Coups, & Pagoto, 2016). Therefore, pivotal to reducing indoor tanning among young women is to address the socially constructed positive perceptions about a tanned look. Media literacy interventions are educational programs to deter unhealthy effects of the media and a meta-analysis of media literacy interventions documented that they have been persuasive in reducing motivations for risk behaviors in a range of domains (Jeong, Cho, & Hwang, 2012). Such an intervention, however, has yet to target indoor tanning.

The present study evaluates the efficacy of a media literacy intervention in reducing indoor tanning behavior among young women. In our intervention, participants critically analyzed the content and functions of the media influencing protanning attitudes (analysis) and on this basis developed counter-messages to help themselves and peers resist protanning media effects (production). Furthermore, this study compared the efficacy of two innovative approaches to production: digital argument production and digital story production. Both are participative production of counter-messages using multimedia, but digital argument production emphasizes logical analyses of representative facts and figures whereas digital story production emphasizes reflections on personal experiences and emotions. By investigating which strategy can be more effective, we sought to inform and enhance future participative communication interventions.

Media Literacy Interventions

Media literacy is a set of knowledge structures concerning media content, media effects, media industries, self, and the real world (Potter, 2013). Because the media tend to portray risk behavior outcomes in a positive light thereby promoting the risk behavior (see for examples Dalton et al., 2002, 2003), media literacy interventions (MLIs) have been designed to provide people with the knowledge to recognize the influences of the media on their health-related decisions and actions and with the skills to combat unhealthy media effects (Thoman & Jolls, 2003). To this end, MLIs comprise two main modules: analysis of media content and effects and production of counter messages against dominant media messages. The analysis module is typically didactic, whereas the production module is participative.

The analysis module has been a core component of MLIs. Generally, through this analysis module, the interventions aimed to increase the knowledge about the media, awareness of media influences, and judgment of media realism which is the ability to discern the discrepancy between media representations and reality (Jeong et al., 2012). Interventions then sought to connect this media-relevant knowledge and skills with behavior-relevant beliefs, attitudes, and intentions (Jeong et al., 2012). Of the media-relevant outcomes, realism judgement may be particularly important to behavior change, as research has found that it predicts attitude toward behavior (see Cho, Shen, & Wilson, 2014).

Compared to analysis, the production component of media literacy has been less frequently investigated. When a small number of previous MLIs added the production component in which participants produced counter messages, it increased the persuasive effects of the intervention (e.g., Banerjee & Greene, 2007). Research has not examined production of which message can be more impactful for behavior change, however.

Two of the primary message forms communication theory has focused on include arguments and stories (Baesler & Burgoon, 1994; Fisher, 1984). Although a wealth of communication research has examined these two message forms, it focused on the effects of exposure to arguments or stories produced by others. Sparse theory or research is available to account for the effects of participants’ production of these messages. Self-persuasion can be a powerful tool for behavior change because the motivation comes from within the person (Aaronson, 1999). Research on self-persuasion, however, has focused on the effects of self-generated arguments (e.g., Baldwin et al., 2017). Little theory and research has examined the effects of self-generated stories.

As arguments and stories are constructed differently, they may activate differential outcomes and processes. Scrutinizing facts and figures, arriving at objective conclusions about social phenomena is important in argument construction (Briñol, McCaslin, & Petty, 2012). Story construction, using retrospective reflection on personal experience, emphasizes reaching acute awareness of one’s life experience and how it was affected by social environment (Larkey & Hill, 2012). Perspectives of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and empowerment theory (Freire, 1970, 1992) suggest that story production may be more effective for behavior change than argument production. According to social cognitive theory, the observation of self’s actions and motivations is a beginning point of self-regulatory behavior change process. To empowerment theory (Freire, 1970), the examination of one’s personal experience and its location in larger social contexts raises critical consciousness that can catalyze social change. The examination of personal experience, the first step toward behavior change (Bandura, 1986) and social change (Freire, 1970), is the foundation of story rather than argument production.

Moreover, in the production portion of group-based MLIs, participants express and share counter messages. Compared to an argument session, speaking about personal experiences may be more emotionally engaging, providing greater motivation for change. Sharing personal stories may foster empathetic bonding and solidarity among community members toward addressing unhealthy social norms (Larkey & Hill, 2012). As argument production utilizes the examination of representative data, facts, and figures, it may be less personal and emotionally engaging. Empathetic connection may be less likely among community members sharing counter-arguments as compared to counter-stories (see Table 1 for a summary of core characteristics of argument and story production).

Table 1.

Core Conceptual Components of Argument and Story Production

| Argument production | Story production | |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Media vs. reality of objective, societal facts | Media vs. reality of lived, personal experience |

| Emphasis | Accuracy and logical strength | Authenticity and emotional strength |

| Visual image | Picture of a media image featuring others | Picture of self |

| Group session goal | Collective validation | Collective support |

On these bases, we expected that participants in our media literacy intervention conditions would report lower indoor tanning rates and less indoor tanning intention than those in the control condition. We also expected that the participants in the digital story production condition would report less indoor tanning behavior and intention than those in digital argument production condition.

Methods

Study Design

To evaluate the efficacy of the intervention, a group randomized controlled design was employed. Sorority chapters were randomly assigned to a media literacy intervention group or a control group. The media literacy intervention was of two types: one with media analysis followed by counter-argument production and the other with media analysis followed by counter-story production. Control group participants received assessments only. A total of 26 sorority chapters participated in this study, of which 10 were in argument condition, 8 in story condition, and 8 in control condition.

The study was scheduled to address the seasonal nature of indoor tanning (IT) behavior, as research shows that IT behavior is more prevalent from January through March than any other months of the year, with a peak in March (Abar et al., 2010; Hillhouse, Turrisi, Stapleton, & Robinson, 2008). Baseline assessment was conducted in September (wave 1) and interventions were delivered in October before the indoor tanning season began. Efficacy of the intervention was assessed in December prior to the beginning of the heavy IT season (2-month follow-up, wave 2) and in April after the heavy IT season (6-month follow-up, wave 3).

Participants

Participants were sorority member college women clustered within sorority chapters. Social normative aspects are salient in tanning behavior, and socially driven risk behaviors are prevalent in sororities (Capone, Wood, Borsari, Laird, 2007; Dennis, Lowe, Snetselaar, 2009; Park, Sher, Wood, & Krull, 2009). Rates of IT behavior are considered to be especially high in sororities, making them a high risk group needing an effective intervention (Dennis et al., 2009; Hovenic et al., 2012). The sororities were in five Midwestern states where more young women indoor tan than those in other parts of the country (CDC, 2012; Demko et al., 2003). Those who engaged in IT behavior in the past or those who had intention to engage in IT behavior in the future (4 or higher on a five-point ranging from 1 “definitely no” to 5 “definitely yes”) were eligible to participate. Participants (n = 247) had the age range of 18 to 28 (M = 20.23, SD = 1.16) and 94.4% of them were White, with the rest comprised of Hispanics (2.4%), more than one race (2.0%), and Asian (1.2%).

Development of the Intervention

We developed and used a procedural framework for media literacy intervention design (see Table 2). This framework is based on a review and integration of prior conceptual (e.g., Potter, 2014) and empirical work on media literacy (e.g., Austin & Johnson, 1997; Hobbs & Frost, 2003; Primack et al., 2006). A cornerstone of the development of MLIs is knowledge about how media portray risk behaviors such as tanning and how those portrayals are associated with willingness to engage in the risk behavior.

Table 2.

Framework for Developing Media Literacy Intervention for Public Health

| Steps | Goals | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understand the public health problem | Literature review |

| 2 | Understand the media-related dimensions of the public health problem | Literature review |

| 3 | Understand media coverage of the public health issue and the effects of the media coverage on the intended audience | |

| Media coverage: What is truthful, distorted, overrepresented, or underrepresented? | Content analysis | |

| Media effects: What are the audience’s perceptions, beliefs, and misinformation? | Survey | |

| 4 | Compare the media coverage and effects and audience perceptions with reality | |

| Use juxtapositions of visual images, texts, and graphs | ||

| Provide evidence for the audience how their perceptions have been influenced by the media | ||

| 5 | Obtain and integrate feedback for the prototype content | Focus group/individual interview |

Formative research was conducted to develop the intervention content. Formative research included a review of literature on media content and effects relevant to tanning (e.g., Cho et al., 2010; Cho, Lee, & Wilson, 2010; Stapleton et al., 2016) and survey of college women (n = 474) assessing their media use habits and IT perceptions and practices. On these bases, images, stories, data, and facts that reflect the core constructs of the intervention were gathered and organized into a PowerPoint presentation for the media analysis module. Formative evaluation of intervention was done at three sorority houses with a total of 45 participants. These three houses did not participate in the main study. Using quantitative measures and free response options, the formative evaluation assessed clarity, accuracy, usefulness, enjoyment, and informativeness of the intervention. The quantitative ratings and qualitative feedback were used to refine and enhance the content and style of the program.

The Intervention

Overall, the intervention consisted of five sections. The first four sections were for media analysis and the fifth and final section was dedicated to media production. The first three media analysis sections were comprised of the following: overview of media influences on women’s perceptions and practices related to health and beauty, specific media content and effects on women’s tanning related perceptions, and malleability of perceptions and misperceptions about tanning as they relate to media portrayals. The fourth section of the media analysis module presented everyday women’s media advocacy against IT behavior and melanoma.

The media literacy intervention was designed to influence cognitive, affective, and social factors that impact risk and risk prevention behavior. The cognitive aspects included media realism judgement which is related to critical thinking abilities (Austin & Johnson, 1997; Hobbs & Frost, 2003; Primack et al., 2006; Thoman & Jolls, 2003). To foster the ability to judge media realism and critical thinking abilities, the intervention provided comparisons between media depictions and reality using juxtapositions of visual images, statistics and facts, after which questions about the realism of media depictions of young women’s body ideals including tan ideals were raised. The affective aspects included involvement in the issue and the social aspects included collective efficacy beliefs (Bandura, 1986) about addressing unhealthy media effects and social norms. Stories of young women who experienced melanoma themselves and the media advocacy work that they have done to prevent others from having the same experience were presented as a means to activate involvement in the issue and collective efficacy in preparation for the media production module that came after the media analysis module.

The media production module encouraged cognitive and affective involvement in the issue and collective efficacy in impacting positive social change. The core conceptual components of argument and story production that guided the design of the production module are presented in Table 1. Each counter message production focused on key characteristics of arguments and stories per Briñol et al. (2012) and Larkey and Hill (2012), respectively. In the argument version of the counter-message production module, participants were asked how they would counter the media’s harmful influence on young women’s appearance-related behavior, including tanning. In the story version of the counter-message production module, participants were asked to describe a time when what they saw or heard in the media changed the way they felt about their appearance including tanning and then look back and reflect.

Participants were presented with examples before developing their own counter-messages. Sample counter arguments included imagery of celebrities and well-known campaign materials that glorified a tanned look, which were followed by images of women who experienced negative health and beauty effects from indoor tanning. The arguments then assessed the motivation and credibility of message producers compared to the health and beauty risks of IT which are typically left undisclosed in advertisements. Sample counter stories showed younger images of the interventionists and the tanned celebrities they used to idolize, which were followed by the experiences of trying out IT for the first time to emulate the celebrities. The stories then described how the outcome was different from the expectations or disappointing, with a retrospective reflection that media had much to do with their own and peers’ desire to achieve a tanned look.

Delivery of the Intervention

The interventions were delivered to sorority houses by two interventionists who were extensively trained in media literacy content and delivery using written script and procedure. Interventions were delivered during one of the times sororities dedicated for their members’ educational meetings. Thus, this study accommodated and fit in the natural organizational schedules of the participating groups. Each intervention lasted about 60 to 75 minutes. The media analysis module lasted 30 minutes, followed by a 30- to 45-minute media production module. In the digital counter message production module, participants worked in groups of 2–3 to design either counter argument or counter story using on iPads. They were instructed to write down individual argument or stories first on a note card, then develop a group message by identifying the common threads. After that, they were instructed to add visual images and voiceover. At the conclusion, screening of the produced counter arguments or stories was done to share them with the rest of the group.

A typical counter-argument tended to follow the structure of the intervention-given examples closely. They included images of celebrity women with a tanned look, which the participants juxtaposed with images everyday women who experienced negative IT effects. The arguments then called for greater awareness of reality among young women. Counter-stories were more varied, reflecting the more personal nature of the task. Some emphasized ways they overcame media influence or would like to; others provided stories of preparing for formals and the need to change social expectations. Counter-arguments included images of celebrities and advertisements, while counter-stories included personal images.

Measures

The primary outcome of interest was IT behavior, which was measured by the scale recommended by National Cancer Institute (Lazovich et al., 2008); the scale’s accuracy and reliability has been documented (Dennis et al., 2008; Hillhouse, Turrisi, Jaccard, & Robinson, 2012). The measure assessed monthly IT behavior, by asking “how many times in the month of [March] have you used a tanning bed or booth,” with an open-ended response format. The measure has been employed in large scale nationwide surveillances of IT behavior conducted by Health Information National Trend Survey of National Cancer Institute, National Health Interview Survey of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Sun Survey of American Cancer Society.

The secondary outcome of interest was future intention to indoor tan, measured by asking participants to indicate how likely they will use an IT bed or booth in the next two months. The response scale ranged from 1 “very unlikely” to 7 “very likely.” This measure was administered at each follow-up and we averaged the two 7-point scale responses at each assessment.

As covariates, we assessed at baseline the number of times that participants used IT beds in the past twelve months and their intention to indoor tan in the next 12 months (see Table 3). The demographic variables of age, race/ethnicity, and skin sensitivity (Weinstock, 1992) were also assessed.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Baseline Variables

| BaselineCovariates | ArgumentMean (SD) | StoryMean (SD) | ControlMean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past 12-month indoor tanning behavior | 17.00 (44.93) | 15.49 (21.16) | 17.22 (30.33) |

| Future indoor tanning intention | 3.26 (1.11) | 3.36 (1.17) | 3.45 (1.30) |

Results

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4. Parameters and standard errors were estimated by maximum likelihood method, using all available information from partially missing cases. There were 1.2% (n = 3) missing data in monthly IT behavior, which were count data. Because an imputation of this variable requires a strong assumption about its distribution and a sufficient basis to make such an assumption is not available in the existing literature, we concluded that an imputation inappropriate. Consequently, we removed the missing cases in analyses. To compare the results before and after the removal we ran the statistical evaluation models described below with multiple imputation (MI). Intervention effects were significant on behavior and intention in both n = 247 with the removal and n = 250 with the MI. The effect estimation was adjusted for baseline covariates including past IT behavior and future IT intention.

Baseline Analyses

For each of the two outcome variables, a mixed-design analysis of variance model was employed to evaluate baseline covariates across the three conditions, with participants and intervention sites treated as random effects. There was no significant difference among the three conditions in past 12-month IT behavior (F = 0.03, p = 0.98) and future IT intention (F = 0.20, p = 0.82). Table 3 presents the details.

Indoor Tanning Behaviors

A mixed-effects logistic regression analysis was performed to model the occurrence of IT behavior in the follow-up months and to evaluate the effect of the intervention on behavior. For this analysis we transformed response to a binary variable, with 1 indicating the occurrence of IT behavior and 0 for no IT behavior. Our original assumption was that the IT behavior will have a Poisson distribution, per previous research (Cokkinides, Weinstock, O’Connell, & Thun, 2002; Cokkinides, Weinstorck, Lazovich, Ward, & Thun, 2009). Poisson distribution, however, failed to describe the distribution of the IT behavior of our sample. On the contrary there were a large number of zero frequencies of IT reported by participants. While the mean and standard deviation should be the same in a Poisson distribution, our mean (1.64) was much smaller than standard deviation (4.17).

Consequently, we considered zero-inflated Poisson and zero-inflated negative binomial models to accommodate the zero inflation and dispersion issues. These models assume heterogeneity within sample: One subgroup would report excessive zeros, while the other would have a Poisson or negative binomial distribution. These models did not accurately explain our data either, because of a subgroup of the sample reported heavy IT behavior (≥ 10 sessions per month). Therefore, an alternative approach was necessary to analyze the behavior.

Considering that the majority of the sample reported zero and a few reported frequent IT behavior, we decided to use a contrast to reflect the subgroups, using the aforementioned binary transformation to focus on predicting whether a participant did not indoor tan (non-user), which corresponds to a zero indoor-tanning frequency, or a participant indoor tanned (user), which corresponds to a positive indoor-tanning frequency. The transformation was appropriate as we found a significant and strong positive point biserial correlation between the binary indicator and IT frequency (r = .69, p < .001).

In the mixed-effects logistic regression model, month and baseline covariates (age, past 12-month IT behavior, future IT intention) were included in the model for adjustments, while participant within site and site within treatment were treated as random effects. Specifically, we allowed for individual variation and site variation and assumed that they were normally distributed. The detailed model was:

where i stood for the intervention condition, j for month, k for site, and l for participant.

A significant difference between intervention and control conditions was found (F2,22 = 4.00, p = 0.033). The baseline covariates of past IT behavior (b = 0.0107, s.e. = .0041, p = 0.0096), and future IT intention (b = 1.0632, s.e. = .1409, p < .0001) were positively associated with the IT behavior reported at the two follow-up assessments, while age was negatively associated with the outcome (b = −0.2758, s.e. = .1174, p = 0.019). We also found a significant difference across the months (F4,964 = 10.29, p < .001).

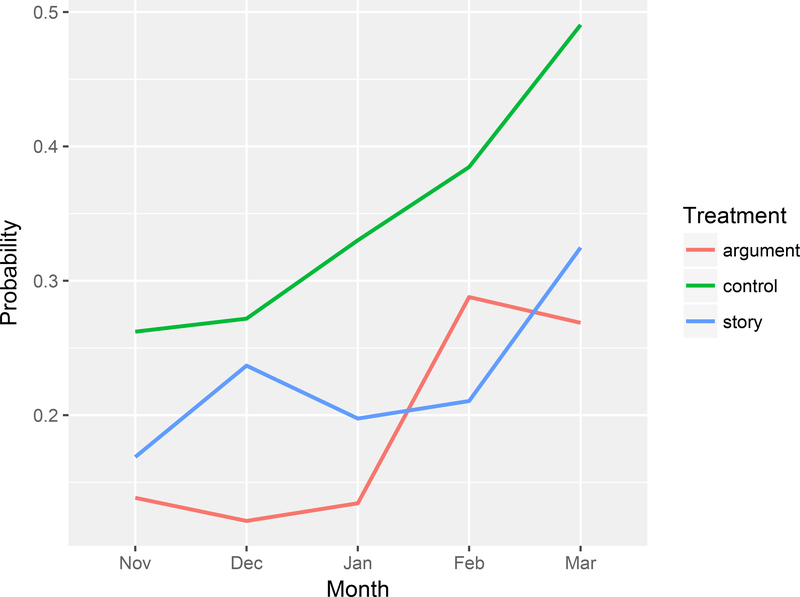

The results indicated that participants in the argument group and story group were less likely to be indoor tanners compared to those in the control group at the two follow-up assessments (βargument= −0.94, βstory= −0.73, βcontrol = 0). Specifically, the odds of reporting as a non-IT bed user were 2.55 (p = .0173) and 2.07 (p = .0489) times less for the argument and story group participants, respectively, compared to the odds of control group participants. Table 4 presents the details. Figure 1 depicts monthly trends of all three groups. Although all three groups exhibited an increasing trend across the follow-up period, the control group reported higher IT frequencies than the argument or story group. The story group reported higher IT frequencies than the argument group, except for February. The increasing trend across the groups reflects the seasonal nature of IT behavior which is generally more frequent between December and March (Abar et al., 2010; Hillhouse et al., 2008). The results show that the intervention buffered the seasonal increase.

Table 4.

Differences in Estimated Effects on Indoor Tanning Occurrence between Conditions

| Estimate | Standard Error | DF | t Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argument vs. Control | −0.9372 | 0.3641 | 22 | −2.57 | 0.0173 |

| Story vs. Control | −0.7270 | 0.3486 | 22 | −2.09 | 0.0489 |

| Argument vs. Story | −0.2102 | 0.3931 | 22 | −0.53 | 0.5982 |

Figure 1.

Probability of Indoor Tanning Bed User

Indoor Tanning Intentions

We investigated the intervention effect on future IT intention at waves 2 and 3 through an analysis of covariance model. The response variable was participants’ IT intention in the next two months. Wave and baseline covariates (age, past 12-month IT behavior, future IT intention) were included in the model as covariates. Participant within site and site within treatment were treated as random effects. The model specification was:

where i stood for the intervention condition, j for month, k for site, and l for subject.

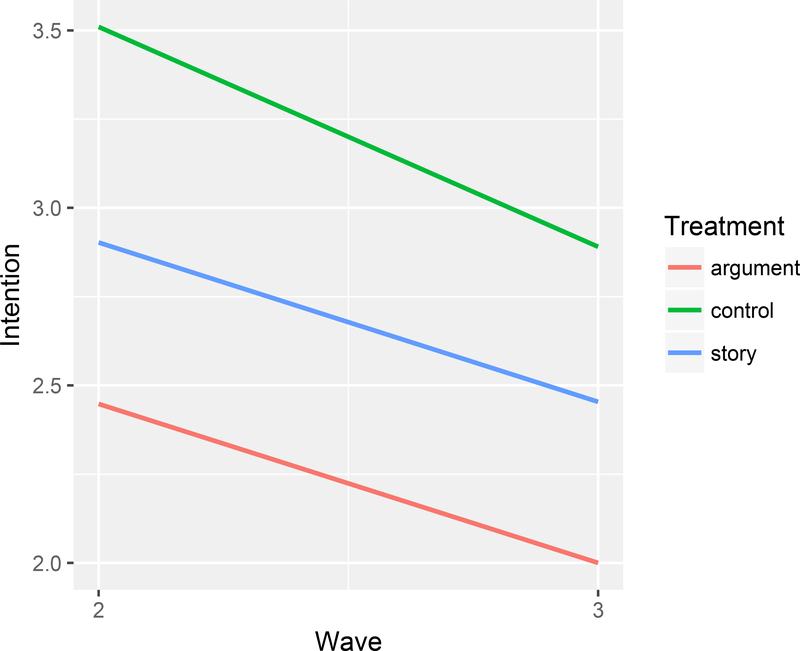

A significant difference among the three conditions was found (F2,22 = 8.26, p = .0021). The baseline covariate of future IT intention (b = 0.7854, s.e. = .0739, p < .0001) was positively associated with the IT intention reported at the two follow-up assessments. We further found significant differences between argument and control (p = .0006), and between story and control (p = .0376). Table 5 shows the results. Participants in the argument and story groups indicated weaker intention to indoor tan in the next two months than those in the control group across the two follow-up assessments. In addition, the argument group exhibited slightly weaker IT intention than the story group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = .0959). In addition, there was a significantly lower IT intention reported at wave 3 than at wave 2 (F1,232 = 16.37, p < .0001), which reflects that the IT season was ending (Hillhouse et al., 2008). Table 6 shows the means and standard deviations of IT intentions across the three groups at waves 2 and 3. Figure 2 depicts the time trends across the conditions.

Table 5.

Tests of Intervention Effects on Future Indoor Tanning Intentions

| Estimate | Standard Error | DF | t Value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argument vs Control | −0.8230 | 0.2049 | 22 | −4.02 | 0.0006 |

| Story vs. Control | 0.4411 | 0.1993 | 22 | 2.21 | 0.0376 |

| Argument vs Story | −0.3819 | 0.2195 | 22 | −1.74 | 0.0959 |

Table 6.

Means and Standard Deviations of Indoor Tanning Intentions at Follow-ups

| Control | Argument | Story | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 2 | 3.51(2.27) | 2.45 (1.80) | 2.90 (1.91) |

| Wave 3 | 2.89 (1.93) | 2.00 (1.54) | 2.45 (1.81) |

Figure 2.

Indoor Tanning Intention

Discussion

Reducing IT behavior is a major goal of the Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent melanoma (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Despite the significance, only a small number of IT interventions have been available (Hillhouse et al., 2008, 2017). This study investigated whether MLIs are a viable strategy to reduce IT behavior. The interventions comprising media analysis and media production modules were delivered to sorority houses in five Midwestern states and the effects of the intervention on IT behavior and intention were assessed through two follow-up assessments conducted at two and six months post intervention.

The results indicate the efficacy of the MLIs for IT reduction. Participants in the intervention groups reported lower IT rates and weaker IT intentions than those in the control group at two- and six-month follow up assessments. To our knowledge, this is the first media literacy intervention to address IT behavior. It is also one of few MLIs that found long term (i.e., ≥ 6 months) intervention effects on behavior.

In addition, the effects were found among sorority women, who are considered an at-risk group because of high rates of IT behavior (Dennis et al., 2008; Hovenic et al., 2012). The interventions included a participative media production component in which sorority members worked together to design digital counter messages against harmful media messages and effects. This study shows that engaging sororities in MLIs was efficacious in reducing their IT risk. Given that the mission of sororities include service, sisterhood, and leadership, members empowered with media literacy through intervention participation can reach out to other young women and share their knowledge and skills.

Notably, this intervention was succinct in duration (60–75 minutes). Extensive, health-related MLIs can comprise five one-hour sessions. Similarly, digital story production is generally considered to require a day’s training. This study demonstrates that a media literacy intervention using participatory counter-message production can be provided to young women in a succinct duration with efficacy, suggesting that it has the potential to reach a larger audience without asking too much of their time. With appropriate reach, an intervention can engage large numbers of young women in creating counter messages, so a cultural shift in the dominant media message about young women’s tanned look could be possible.

An innovative component of this study was the comparison of digital counter argument and story production. Between the two, a slight and statistically nonsignificant advantage of argument production over story production was observed. Participants in the argument group reported weaker intentions to IT in the future than those in the story group. This finding contradicts the expectation that story production will generate greater changes in IT behavior and intention than argument production.

This unexpected finding necessitates speculation about the reason. First, the small-group setting may have been less conducive to the self-introspection crafting digital stories requires than the collection and analysis of generalized facts needed to support digital arguments. Because this was a group-level intervention, the small-group format for the media production module was deemed more appropriate and consistent with the overall structure of the intervention. Future research should investigate whether the relative efficacies of argument and story production change in individual-level interventions. Second, argument rather than story production may have been more consistent with the central tenet of media literacy, which is the ability to analyze media and to apply these skills to decisions and actions. Taken together, an important next step in this research is to examine the psychological and social processes mediating or moderating the differences observed between the argument and story groups. Additionally, this result may reflect the dearth of conclusive evidence supporting the notion that exposure to stories is more persuasive than exposure to other message forms such as arguments. The result also resonates with a meta-analysis that found the persuasive advantage of statistical evidence over story (Allen & Preiss, 1997; see also Baesler & Burgoon, 1994).

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has some limitations. This study could involve only the sorority chapters whose leadership was open to it. Sororities plan their schedule far ahead and a substantial portion of it comprises university or college mandated educational programs, thus finding the time slot for the intervention was challenging and identifying a timeslot did not guarantee all sorority members were able to attend at the given time. Considering the difficulties that this study faced, and the efficacy it demonstrates in spite of them, future research should examine ways for remote-delivery and remote-access of the intervention (e.g., web-based) for wider reach and greater impact. Researchers should also consider contextual influences on the dissemination of MLIs and the role of social networks within and across sororities in the diffusion of media literacy and risk prevention behavior.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, this study adds to the approaches to public health interventions for preventing risk behaviors. Public health interventions frequently utilize behavior change theories that elucidate beliefs about behavior that determine the likelihood of the behavior. Because the media are an important source of behavioral beliefs (Fishbein & Yzer, 2003), when beliefs about the media are addressed underpinning causes of the behavioral beliefs may be addressed. This study indicates that focusing on media literacy to address the role of the media in facilitating positive beliefs about a risk behavior can be a fruitful route to reducing the risk behavior.

This study contributes to the emergent literature on participative engagement in health interventions (e.g., Freedman et al., 2009; Gubrium & Harper, 2013; Larkey & Hill, 2012; Schillinger et al., 2017). Communication theory and research has focused on the effects of exposure to messages produced by others. This study investigated the effects of production of messages by self, and compared the relative effectiveness of argument and story production. To date, sparse research has investigated which participative strategies can be more effective for behavior change, despite the growing recognition of the importance of participative engagement.

Although the difference between argument and story failed to reach significance, perhaps due to insufficient statistical power, the trend toward the advantage of argument over story observed in this study contribute to the knowledge base on the effects of participative interventions. Simultaneously, the finding about the argument advantage could be a caveat that story production might not be as powerful as previously thought. The next step of this research is to examine the underlying mechanisms of argument and story production effects. Future studies should continue to investigate the effects of differential participative engagement strategies in order to inform intervention design and enhance intervention outcomes.

Practically, the results show that media literacy education is a useful approach to reduce young women’s IT behavior, a significant cause of melanoma in this population. Therefore, future efforts to prevent IT behavior and melanoma among young women should consider including media literacy education as a core intervention component.

Contributor Information

Hyunyi Cho, School of Communication, The Ohio State University 154 N. Oval Mall Columbus, OH 43210 Phone: 614-247-1691, cho.919@osu.edu.

Bing Yu, Purdue University.

Julie Cannon, Cornell University.

Yu Michael Zhu, Purdue University.

References

- Aronson E (1999). The power of self-persuasion. American Psychologist, 54, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Abar BW, Turrisi R, Hillhouse J, Loken E, Stapleton J, & Gunn H (2010). Preventing skin cancer in college females: heterogeneous effects over time. Health Psychology, 29, 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, & Preiss RW (1997). Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta‐analysis. Communication Research Reports, 14, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2017). Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer.html

- Austin EW, & Johnson KK (1997). Effects of general and alcohol-specific media literacy training on children’s decision making about alcohol. Journal of Health Communication, 2, 17–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AS, Denman DC, Sala M, Marks EG, Shay A, Sobha F, … Tiro JA (2017). Translating self-persuasion into an adolescent HPV vaccine promotion intervention for parents attending safety-net clinics. Patient Education and Counseling, 100, 736–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SC, & Greene K (2007). Antismoking initiatives: Effects of analysis versus production media literacy interventions on smoking-related attitude, norm, and behavioral intention. Health Communication, 22, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsma LJ, & Carney ME (2008). Effectiveness of health-promoting media literacy literature education: A systematic review. Health Education Research, 23, 522–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baesler EJ, & Burgoon JK (1994). The temporal effects of story and statistical evidence on belief change. Communication Research, 21, 582–602. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol P, McCaslin MJ, & Petty RE (2012). Self-generated persuasion: Effects of the target and direction of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 925–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Wood MD, Borsari B, & Laird RD (2007). Fraternity and sorority involvement, social influences, and alcohol use among college students: A prospective examination. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 21, 316–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2012). Use of indoor tanning devices by adults — United States, 2010. MMWR, 61, 323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Hall JG, Kosmoski C, Fox RL, & Mastin T (2010). Tanning, skin cancer risk, and prevention: A content analysis of eight popular magazines that target female readers, 1997–2006. Health Communication, 25, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Lee S, & Wilson K (2010). Magazine exposure, stereotypical beliefs about tanned women, and tanning attitudes. Body Image, 7, 364–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Shen L, & Wilson KM (2014). Perceived realism: Dimensions and roles in narrative persuasion. Communication Research, 41, 828–851. [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Weinstock MA, O’Connell MC, & Thun MJ (2002).Use of indoor tanning sunlamps by US youth, ages 11–18 years, and by their parent or guardian caregivers: Prevalence and correlates. Pediatrics, 102, 1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Lazovich E, Ward E, & Thun M (2009). Indoor tanning use among adolescents in the U.S., 1998 to 2004. Cancer, 115, 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, Jenkins MA, Schmid H, Hopper JL, … Mann GJ (2011). Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. International Journal of Cancer, 128, 2425–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Ahrens MB, … Heatherton TF Effects of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. Lancet, 362 (9380), 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, & Heatherton TF (2002). The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Preventive Medicine, 34, 516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demko CA, Borawski EA, Debanne SM, Cooper KD, & Stange KC (2003). Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the United States. Archives Pediatric Dermatology, 157, 854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis LK, Lowe JB, & Snetselaar LG (2009). Tanning behavior among young frequent tanners is related to attitudes and not lack of knowledge about dangers. Health Education Journal, 68, 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis LK, Kim Y, & Lowe JB (2008). Consistency of reported tanning behaviors and sunburn history among sorority and fraternity students. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology, and Photomedicine, 24, 191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WR (1984). Narrative as human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M & Yzer MC (2003). Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory, 13, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DA, Bess KD, Tucker HA, Boyd DL, Tuchman AM, & Wallston KA (2009). Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36, 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1992) Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A, & Harper K (Eds). (2013). Participatory visual and digital methods. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Jaccard J, & Robinson J (2012). Accuracy of self-reported sun exposure and sun protection behavior. Prevention Science, 13, 519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Scaglione NM, Cleveland MJ, Baker K, & Florence C (2017). A web-based intervention to reduce indoor tanning motivations in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 18, 131–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, & Robinson JA (2008). A randomized controlled trial of an appearance focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer, 113, 3257–3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R, & Frost R (2003). Measuring the acquisition of media-literacy skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 38, 330–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hovenic W, Miles A, Lewis E, Hoffman E, Edison K, Carstens S, … Fancher W (2012). Knowledge is not power: Knowing risks of tanning does not impact tanning behaviors in members of sororities on a Big 12 campus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 66, AB85. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Cho H, & Hwang Y (2012). Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication, 67, 454–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, & Hill A (2012). Using narratives to promote health In Cho H (Ed.), Health communication message design: Theory and practice (pp. 95–112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lazovich D, Stryker JE, Mayer JA, Hillhouse J, Dennis LK, Pichon L, … Thompson K (2008). Measuring nonsolar tanning behavior: Indoor tanning and sunless tanning. Archives of Dermatology, 144, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Wood PK, & Krull JL (2009). Dual mechanisms underlying accentuation of risky drinking via fraternity/sorority affiliation: the role of personality, peer norms, and alcohol availability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 241–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter WJ (2014)). Media literacy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Gold MA, Switzer GE, Hobbs R, Land SR, & Fine MJ (2006). Development and validation of smoking media literacy scale for adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 160, 369–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JK, Kim J, Rosenbaum S, & Ortiz S (2008). Indoor tanning knowledge, attitudes, and behavior among young adults from 1988–2007. Archives of Dermatology, 144, 484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Ling PM, Fine S, Boyer CB, Rogers E, Vargas RA, … Chou WS (2017). Reducing cancer and cancer disparities: Lessons from a youth-generated diabetes prevention campaign. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, S103–S113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2018). Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JL, Hillhouse J, Coups EJ, & Patoto S (2016). Social media use and indoor tanning among a national sample of young adult non-Hispanic white women: A cross-sectional study. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 75, 218–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoman E, & Jolls T (2003). Media Lit Kit—Literacy for the 21st Century: An overview and orientation guide to media literacy education. Retrieved from: http://www.medialit.org/sites/default/files/01_MLKorientation.pdf

- Ting W, Schultz K, Cac NN, Peterson M, & Walling HW (2007). Tanning bed exposure increases the risk of malignant melanoma. International Journal of Dermatology, 46, 1253–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock MA (1992). Assessment of sun sensitivity by questionnaire: Validity of items and formulation of a prediction rule. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl J, Olsson H,, Masback A, Ingvar C, Jonsson N, Brandt L, … Moller T (1994). Use of sunbeds or sunlamps and malignant melanoma in southern Sweden. American Journal of Epidemiology, 140, 691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl J, Ingvar C, Masback A, Jonsson N, & Olsson H (2000). Risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in relation to use of sunbeds: further evidence for UV-A carcinogenicity. British Journal of Cancer, 82, 1593–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. Retrieved from: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/prevent-skin-cancer/