Abstract

The declining efficiency of myelin regeneration in individuals with multiple sclerosis has stimulated a search for ways by which it might be therapeutically enhanced. Here we have used gene expression profiling on purified murine oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), the remyelinating cells of the adult CNS, to obtain a comprehensive picture of how they become activated after demyelination and how this enables them to contribute to remyelination. We find that adult OPCs have a transcriptome more similar to that of oligodendrocytes than to neonatal OPCs, but revert to a neonatal-like transcriptome when activated. Part of the activation response involves increased expression of two genes of the innate immune system, IL1β and CCL2, which enhance the mobilization of OPCs. Our results add a new dimension to the role of the innate immune system in CNS regeneration, revealing how OPCs themselves contribute to the postinjury inflammatory milieu by producing cytokines that directly enhance their repopulation of areas of demyelination and hence their ability to contribute to remyelination.

Keywords: cytokines, migration, multiple sclerosis, Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, remyelination

Introduction

The adult CNS contains a widespread population of multipotent progenitor cells, commonly referred to as oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs; ffrench-Constant and Raff, 1986; Levine et al., 2001). While the physiological function of these cells in the normal CNS remains uncertain, it is well established that adult OPCs (aOPCs) are primarily responsible for generating new oligodendrocytes (OLs) and the restoration of myelin sheaths following demyelinating injury (Zawadzka et al., 2010). This regenerative process of remyelination can be highly efficient, especially after single episodes of demyelination in young adults (Shields et al., 1999). However, in chronic demyelinating disease, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), remyelination becomes less efficient, with the result that axons are left denuded and vulnerable to irreversible degeneration, leading to the accumulation of disability (Ferguson et al., 1997; Nave and Trapp, 2008). To develop therapies by which remyelination can be enhanced, it will be necessary to identify the key mechanisms that regulate remyelination.

At least three distinct phases of remyelination are identifiable, as follows: first, a process of activation, in which aOPCs in the vicinity of the injury change their shape and gene expression profile; second, aOPC recruitment into and within the demyelinated area by migration and proliferation; and third, differentiation of the recruited aOPCs into mature myelin sheath-forming oligodendrocytes (Levine and Reynolds, 1999). Ultimately, the successful orchestration of remyelination involves a complex interplay between environmental and cell intrinsic mechanisms in which the transition between each phase is appropriately timed (Franklin, 2002).

Genomic screening has already led to the identification of several important regulatory pathways and mechanisms by which remyelination is governed. These include the Wnt pathway, a negative regulator of differentiation and two positive regulatory mechanisms involving the nuclear receptor RXRγ (retinoid X receptor γ) and the transcription factor MRF (myelin gene regulatory factor; Emery et al., 2009; Fancy et al., 2009, 2011; Huang et al., 2011; Koenning et al., 2012). These studies testify to the value of gene-profiling approaches and prompted us to establish the gene profile of aOPCs in the normal physiological state and how it changes in response to demyelinating injury as aOPCs prepare to engage in remyelination.

Materials and Methods

Animals and cuprizone treatment.

Neonatal OPCs (nOPCs) and aOPCs were isolated from the brain of either sex postnatal day 1 (P1) to P5 and 2-month-old PDGFαR:GFP hemizygous mice, respectively (Klinghoffer et al., 2002; RRID:IMSR_JAX:007669). Adult OPCs in demyelinating conditions (activated aOPCs) were isolated from the brain of either sex 2-month-old PDGFαR:GFP mice, previously treated for 5 weeks with cuprizone (0.2%; Sigma). Adult OLs were isolated from the brains of 2-month-old PLP:GFP homozygous mice of either sex (Spassky et al., 2001). Animal care and experiments were performed according to European Community regulations and ethics policies.

Fluorescent-activated cell sorting purification of GFP-positive oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells.

Isolation was performed in two steps, as described previously (Piaton et al., 2011). Briefly, brains from either PDGFαR::GFP mice (Klinghoffer et al., 2002; RRID:IMSR_JAX:007669) or PLP-GFP mice (Spassky et al., 2002) were used to obtain OPCs and oligodendrocytes, respectively. Tissue was dissected in HBSS 1× [HBSS 10× (Invitrogen), 0.01 m HEPES buffer, 0.75% sodium bicarbonate (Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin] and mechanically dissociated. After an enzymatic dissociation step using papain (30 μg/ml in DMEM-Glutamax, with 0.24 μg/ml l-cystein and 40 μg/ml DNase I), cells were put on a preformed Percoll density gradient before centrifugation for 15 min. Cells were then collected and stained with propidium iodide (PI) for 2 min at room temperature (RT). In a second step, GFP-positive and PI-negative cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Aria, Becton Dickinson) and collected in pure fetal bovine serum. To ensure the sorting of a homogenous population of OPCs from adult PDGFαR::GFP brains, only the high GFP cells (selected using a cutoff of fluorescence intensity representing ∼90% of the GFP cells) were sorted, as described by Piaton et al. (2011). For microarray analysis, cells were washed twice in PBS 1× (PBS 10×, Invitrogen), then the dry cell pellets were frozen at −80°C. For cultures, cells were maintained in modified Bottenstein–Sato (BS) medium (DMEM containing 0.5% FCS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 10 μm insulin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite, 100 μg/ml transferrin, 0.28 μg/ml albumin, 60 ng/ml progesterone, 16 μg/ml putrescine, 40 ng/ml triiodothyronine, and 30 ng/ml l-thyroxine), before being platted on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips (40 μg/ml, Sigma; for immunostaining and ELISA), on Matrigel-coated wells (1:10; BD Biosciences; for video microscopy), or on transwell xCELLingence inserts (Roche; for migration assay). To assess the differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis of in vitro OPCs, recombinant proteins Il1β (5 ng/ml; R&D Systems) or Ccl2 (20 ng/ml; PeproTech) were added in BS medium. To assess differences in differentiation, we used a morphological classification of oligodendroglial development adapted from Huang et al. (2011), in which five stages were defined. For flow cytometry analysis, cells were fixed with 4% PFA, directly after the Percoll gradient. Then they were incubated with anti-O4-PE antibody [mouse IgM, dilution 1:11 for 106 cells/100 μl; catalog #130-095-887 (RRID:AB_10831029), Miltenyi Biotec] or control isotype [mouse IgM PE, dilution 1:11 for 106 cells/100 μl; catalog #130-093-177 (RRID:AB_871723), Miltenyi Biotec], for 30 min at RT in PBS 1×. Cells were analyzed using a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and Diva software.

RNA extraction and microarray analysis.

For each condition, we used four independently FACS samples, to provide four biological replicates. Total RNA was extracted using NucleoSpin RNA XS kit (Macherey-Nagel). Quantity and quality of RNA extractions were analyzed using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico kit (Agilent). Labeled RNAs (Liqa Kit, Agilent) were then hybridized onto Agilent whole-mouse genome microarray chips. Data were normalized and analyzed using the R statistical open tool (R Manuals; RRID:OMICS_01764). We used a Student's t test and Benjamini–Hochberg test to identify the differentially expressed genes between two conditions (cutoffs: p < 0.001 and q < 0.01, respectively). Gene expression levels and unsupervised hierarchical clustering were visualized using MultiExperiment Viewer version 4.6.0 open software (TM4 Microarray Software Suite: TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer; RRID:nif-0000-10486). The gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed using GOrilla open software. Ariadne Genomics-Pathway Studio software was used to select genes of interest. A full list of genes was deposited in NCBI GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus; RRID:nif-0000-00142; accession number: GSE48872).

Immunostaining.

For immunohistochemistry, animals were perfused with 4% PFA in PBS 1×. The brains were dissected, and cryoprotected in PBS 1× and sucrose 15% at 4°C overnight, frozen embedded in gelatin 7% (gelatin porcine skin, Merck), sucrose 15%, PBS 1×; and 14 μm serial coronal cryostat sections were saved. Other brain samples were dissected, and maintained in PBS 1× in 20 μm serial coronal vibratome sections. The slides were treated for 10 min with 100% ethanol at −20°C, and, after saturation in PBS 1×, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 10% horse serum for 1 h at RT, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS 1×, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 5% horse serum. After washing, Alexa Fluor-conjugated and biotinylated secondary antibodies were incubated for 1.5 h at RT. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst solution (1 μg/ml), and sections were mounted in Fluoromount-G (CliniSciences). For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at RT, and staining was performed as described above, without the ethanol step. Staining was observed using a fluorescence microscope Zeiss Imager. Pictures were acquired with an AxioCam camera and analyzed using ImageJ software (ImageJ; RRID:nif-0000-30467). For quantification of Ccl2 and Il1β expression on coronal sections of demyelinated brains, only demyelinating areas, selected by the absence of or low myelin basic protein (MBP) staining, were quantified. Similar areas were quantified on control sections.

Antibodies.

For immunostaining, antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-MBP [chicken IgY, 1:200; catalog #AB9348 (RRID:AB_2140366), Chemicon International/Millipore/Linco Research], anti-platelet-derived growth factor α receptor [PDGFαR; rat IgG2a, 1:800; catalog #562171 (RRID:AB_2307390), BD PharMingen], anti-GFP (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500; catalog #A6455 (RRID:AB_221570), Invitrogen], anti-cleaved caspase-3 [rabbit polyclonal, 1:500; catalog #AF835 (RRID:AB_2243952), R&D systems], anti-Ki-67 [mouse IgG1, 1:400; catalog #550609 (RRID:AB_2307388), BD-PharMingen], anti-Ccl2 (rabbit IgG, 1:1000, Torrey Pines Biolabs), anti-Ccl2 [mouse IgG1, clone 5D3-F7, 1:100; catalog #16-7099-85 (RRID:AB_469223), eBioscience; for human tissue], anti-Il1β [rabbit polyclonal, 1:100; catalog #ab9722, (RRID:AB_308765), Abcam], anti-Olig1 [mouse IgG2b, 1:400; catalog #MAB2417 (RRID:AB_2157534), R&D Systems], anti-Olig2 [rabbit polyclonal, 1:200; catalog #AB9610 (RRID:AB_570666), Chemicon International/Millipore/Linco Research], anti-Ccr2 [rabbit polyclonal, 1:200; catalog #ab21667 (RRID:AB_446468), Abcam], anti-A2B5 [mouse IgM, 1:5; catalog #MAB1416 (RRID:AB_357687), R&D Systems], anti O4 (mouse monoclonal IgM, 1:5; hybridoma was a gift from I. Sommer, University of Glasgow, UK), and anti-NG2 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:200; Millipore).

Quantitative PCRs.

PCR primers for mouse Il1β, Ccl2, Ccr2, Il1r1, and Ppia were purchased from Qiagen. RT was performed using Verso cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on the LightCycler 480 using the QuantiFast Probe Duplex Assays (Qiagen). Results were normalized against Ppia and expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Cell migration.

Cell migration was assessed using the xCELLingence System (Roche). On top of the upper chamber, 25,000 FAC-sorted cells were plated. Control medium or medium containing the recombinant proteins Il1β (5 ng/ml; R&D systems) or Ccl2 (20 ng/ml; PeproTech), and/or their respective antagonists Il1ra1 (200 ng/ml; R&D systems) and INCB3344 (INCB, 8 μm; Chemscene) were distributed in the lower chambers. Cell migration was followed for 48 h. Each condition was run simultaneously in triplicate or quadriplicate. Results were expressed compared with control medium or with the migration of aOPCs under control conditions for each independent experiment (n = 5).

Video microscopy.

FAC-sorted cells were plated on Matrigel-coated wells for 24 h. Cells were then monitored for 24 h (one picture every 10 min) using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and a Hamamatsu camera, in BS medium only (for control conditions and for transduced cells) or in BS medium with Il1β (5 ng/ml; R&D systems) or Ccl2 (20 ng/ml; PeproTech) recombinant proteins. MetaMorph tracking software was used to follow every cell (identified by a single colored spot), and quantify their motility and velocity. Three distinct positions and an average of 150 cells per well were analyzed.

ELISA.

FAC-sorted cells were plated in 96-well plaques (100,000 cells per well, in 100 μl of BS). After 24 h, supernatants from FACs-purified aOPCs were collected, and cells were detached using trypsin (0.025%). Cells were then lysed in Tris (50 mm), pH 7.4, NaCl (150 mm), Triton 1%, and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100; Sigma). The protein concentration in cell lysates was quantified using a BCA protein assay to normalize Ccl2 and Il1β expression. Ccl2 and Il1β expressions in cell supernatants and cell lysates were quantified following Mouse MCP-1 ELISAs and Mouse Il1β ELISAs, respectively (BioVendor).

CG4 culture.

Rat CG4 cells were grown on poly-d-ornithine-coated (100 μg/ml) plastic Petri dishes in a mixture of N1 medium supplemented with B104 medium (30%) and biotin (10 ng/ml).

Lentiviral vector production.

The plasmid insert pDONR221mm_ccl2 (a gift from Dr. S. Melik-Parsadaniantz, Institut de la Vision, Paris, France) has been completely sequenced before use. Lentiviral vectors were prepared through LR clonase II Gateway recombination (Invitrogen) to generate CMV_CCL2-2A-mCherry and CMV_DsRed-Myc. Lentiviral vector stocks were produced by transient transfection of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with the p8.9 encapsidation plasmid, the VSV glycoprotein-G-encoding pHCMV-G plasmid, and the lentiviral recombinant vector. Supernatants were ultracentrifugated, and the pellets were resuspended in PBS 1×. Aliquots were kept at −80°C until use. The transduction efficiency of each lentivirus was evaluated using ELISA p24 titration kit (ZeptoMetrix) on HEK 293T cells.

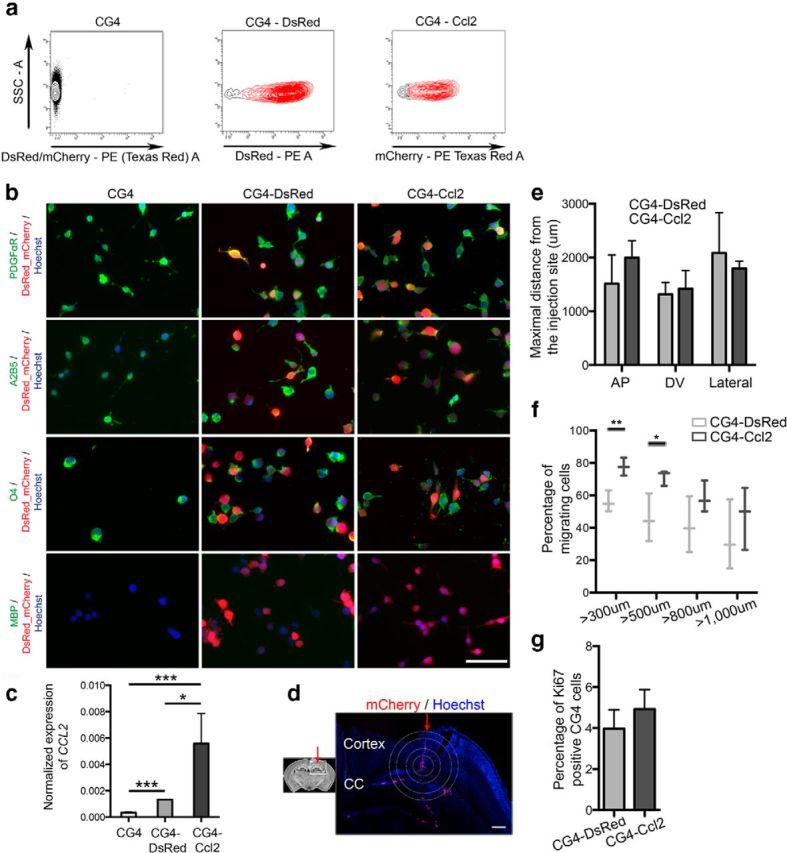

Cell transduction and grafting.

Two-month-old PDGFαR:GFP brain cells were isolated by Percoll gradient as previously described. Cells were resuspended in BS medium and plated on 25 cm2 flasks. CG4 cells were maintained in N1 culture medium. Cells were then transduced for 24 h with either CMV_CCL2-2A-mCherry or CMV_DsRed-Myclentiviral vectors at a multiplicity of infection of 100, using DEAE-Dextran hydrochloride for OPCs, not for CG4 (1×; Sigma). Three days after the transduction, mCherry-positive or DsRed-positive cells (OPCs or CG4 cells) were FAC-sorted and plated back, or 100,000 CG4 cells were directly grafted in the anterior brain of postnatal 2-d-old PDGFαR:GFP mice. P2 PDGFαR::GFP mice were killed 40 h after the CG4 graft, and brains were dissected and frozen before being coronally cut by cryostat. For each brain, we accessed the maximal lateral, dorsoventral, and anteroposterior migration. We quantified the number of CG4 cells remaining at the injection site, which migrated over 300, 500, 800, and 1000 μm, and therefore calculated the percentage of moving cells. For each experiment, we analyzed three to six animals per condition.

Multiple sclerosis tissue samples.

Fixed postmortem multiple sclerosis brain samples were obtained from the UK Multiple Sclerosis tissue Bank. Histological assessment of the lesions was performed using Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet and Oil-red-O (macrophages filled with myelin debris) histological staining. Lesions were classified according to their inflammatory activity (KP1 immunolabeling) and on the basis of histological criteria of acute lesions (active demyelination, myelin vacuolation, inflammation or edema, minor gliosis, and vague margin) and chronic lesions (no myelin vacuolation, absence of inflammation, gliosis, axonal loss, and sharp margin). The expression of Ccl2 was analyzed in active lesions (n = 5), the active border of chronic lesions (n = 3), the chronic silent core (n = 4), and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM, n = 6) from six different patients. For each lesion, we calculated the ratio of Ccl2 expression by aOPCs in the lesion normalized to the percentage in adjacent NAWM of the same size. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described above, with the addition of an initial pretreatment with an unmasking solution (low pH, citric acid; Vector Laboratories).

Statistical analyses.

All quantifications were performed blindly. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 software. Error bars on all graphs represent the SE.

Results

The gene expression profile of aOPCs in normal CNS resembles that of OLs

OLs are distinctive from the progenitor cells that give rise to them, and so, as expected, the two cells have distinctive gene expression profiles (Cahoy et al., 2008). However, the transcriptional profile of aOPCs in the normal intact CNS is unknown. Furthermore, since increased expression of genes associated with developmental myelination has been detected in aOPCs in response to demyelination in the adult CNS (Fancy et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2008), we first hypothesized that the transcriptome of the aOPCs would be distinct from that of the nOPCs, and, second, that the transcriptome of the aOPCs would revert to that of the nOPCs upon activation. To address the first of these, we compared gene profiles of aOPCs with those of nOPCs and OLs.

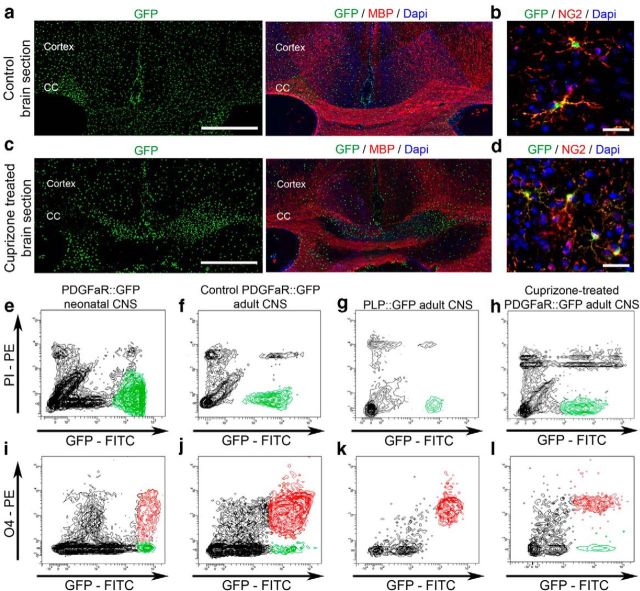

Adult OPCs were isolated by FACS from brains of 2-month-old PDGFαR:GFP transgenic mice (Klinghoffer et al., 2002; Hamilton et al., 2003) using a cutoff of fluorescence intensity to select high-GFP cells, as previously described (Piaton et al., 2011). To ensure that the GFP population, widely distributed in the adult CNS (Fig. 1a), consisted of aOPCs, we assessed their expression of NG2, a marker of OPCs, in vivo. Whereas 91.7 ± 1.7% of the GFP-positive cells expressed NG2+, virtually all highly GFP-positive cells were NG2 positive (Fig. 1b). In contrast, low-expressing GFP cells (not exceeding 10% of the GFP-positive cells in vivo) were NG2 negative, possibly corresponding to differentiating cells.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometry sorting of OPCs and OLs. a, Coronal section of a control adult PDGFαR::GFP brain showing homogeneously distributed GFP-positive aOPCs. Scale bar, 200 μm. b, GFP-positive cells are also expressing NG2. Scale bar, 50 μm. c, Coronal section of a demyelinated brain treated with cuprizone for 5 weeks, showing increased GFP-positive cell density within the demyelinated areas (lack of MBP staining). Scale bar, 200 μm. d, GFP-positive cells expressing NG2 on a cuprizone-treated brain section. Scale bar, 50 μm. e, f, h, Neonatal OPCs (e), and adult OPCs from control (f) and from demyelinated conditions (h) are sorted by flow cytometry from PDGFαR::GFP brains. g, Mature OLs are isolated from PLP-GFP brains. All sorted cells are GFP positive and PI negative. i–l, Flow cytometry analysis of O4 expression in neonatal OPCs (i), adult OPCs from control (j), demyelinated brains (l) and mature OLs (k). CC, Corpus callosum.

Neonatal OPCs were isolated by FACS from the brains of P1–P5 PDGFαR:GFP transgenic mice. OLs were isolated by FACS from the brains of adult (2-month-old) PLP-GFP mouse in which GFP is restricted to mature OLs (Fig. 1g; Spassky et al., 2001; Le Bras et al., 2005).

Flow cytometry analysis showed that O4 was expressed by 72.8 ± 4.9% of cells sorted from PDGFαR:GFP neonatal brain, whereas it was expressed by 94.9 ± 1.6% of cells isolated from PDGFαR:GFP adult brain and 97.2 ± 2.3% of cells isolated from proteolipid protein (PLP)-GFP adult brains (Fig. 1e–g,i–k).

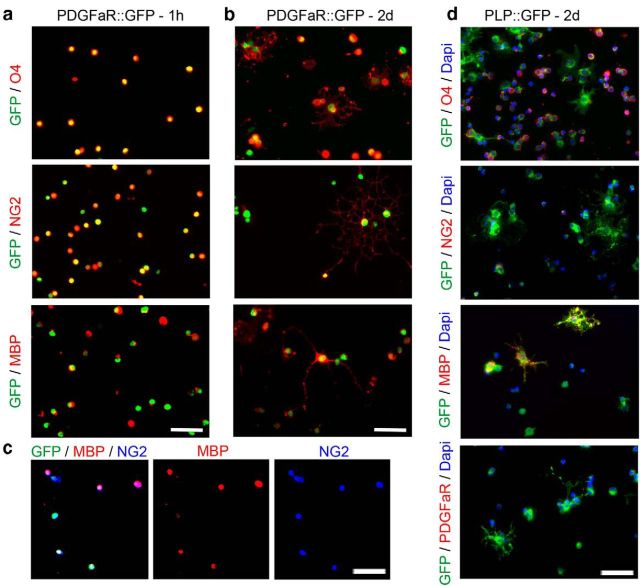

To further characterize sorted cells from PDGFαR:GFP adult brains, immunolabeling was performed, 1 h and 2 d after sorting, on cells cultured in modified BS medium. At both time points, GFP-sorted cells expressed markers of immature stages of the oligodendroglial lineage, such as O4 and NG2 (96% and 98%, respectively, quantification in one representative experiment), but also the marker of mature stages MBP [87%, quantification in one representative experiment; Fig. 2a–c (see triple labeling in c)]. This in vitro analysis supported the conclusion that the GFP-positive population isolated from adult PDGFαR:GFP transgenic mice were adult OPCs. In contrast, whereas OLs sorted from PLP-GFP adult brains expressed O4 and MBP, they did not express NG2 or PDGFαR (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

In vitro characterization of the sorted cell populations. a, b, Immunolabeling on sorted GFP-positive cells isolated from PDGFαR::GFP brains, 60 min after cell platting (a) or after 2 d in culture (b). Sorted aOPCs express NG2 and O4, as well the mature marker MBP. Scale bar, 50 μm. c, Triple staining with GFP/NG2/MBP. d, Immunolabeling on GFP-positive cells isolated from PLP-GFP brains, after 2 d in culture. Only a percentage of sorted aOLs express O4, whereas almost all express MBP. NG2 or PDGFαR expressions are not detected on aOLs. Scale bar, 50 μm.

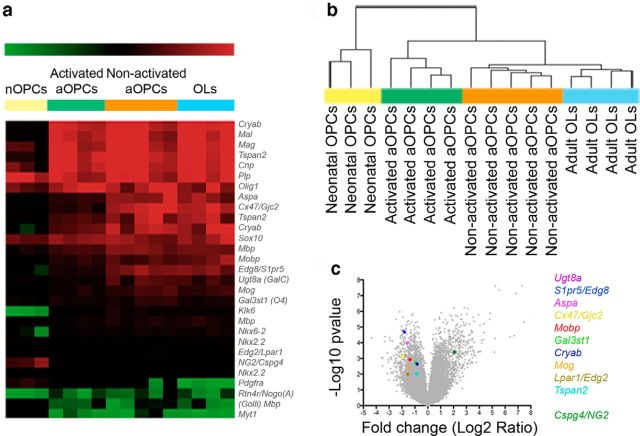

Having characterized in vitro populations of nOPCs, aOPCs, and OLs, a microarray analysis of each cell population was undertaken with four independently sorted samples providing four biological replicates. Total RNA prepared from each cell type was used to generate labeled RNA, which were hybridized to Agilent whole-mouse-genome microarrays. To validate the data obtained, we first examined genes known to be specific to the oligodendrocyte lineage. Quantitative comparison of gene expression data from nOPCs, aOPCs, and mature OLs distinguished the three cell populations (Fig. 3a). For example, NG2 was highly expressed by nOPCs and aOPCs compared with OLs (a 93.1-fold increase in nOPCs, p < 0.001; and a 2.74-fold increase in aOPCs, p < 0.05). Similar differential expression occurred with PDGFαR (214.6-fold increase in nOPCs, p < 0.001; 4.53-fold increase in aOPCs, p < 0.05, compared with OLs). Conversely, mRNAs of MBP, myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein (MOBP), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) were more highly expressed in OLs compared with nOPCs (MBP: 4.46-fold increase, p < 0.001; MOBP: 25.5-fold increase, p < 0.01; MOG: 41.2-fold increase, p < 0.001, in OLs compared with nOPCs). However, the expression of these differentiation-associated genes was also significantly greater in aOPCs than in nOPCs (MBP: 4.20-fold increase p < 0.01; MOBP: 77.9-fold increase p < 0.005; MOG: 43.7-fold increase p < 0.001, in aOPCs compared with nOPCs).

Figure 3.

mRNA profile of the sorted populations. a, Microarray analysis restricted to oligodendroglial genes showing the different profiles of each population. b, Hierarchical clustering of all genes (dendogram): each column represents the gene expression of one replicate (Pearson correlation, using Multi-Experiment Viewer). Volcano plot (x-axis = Log2 ratio activated vs nonactivated aOPCs; y-axis = −Log10 p value) shows the changes induced by demyelination in aOPCs, and colored dots point to some known oligodendroglial markers. c, On the right are genes overexpressed, and on the left genes underexpressed by activated aOPCs.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of all genes revealed that aOPCs and OLs have a gene expression profile more similar to each other than to nOPCs (Fig. 3b). Such clustering was not due to the differential expression of genes related to cell division, as the dendrogram pattern was not modified when proliferation and cell cycle-related genes were excluded from the analysis. To identify genes most differentially expressed among the three cell populations, we used Student's t test and Benjamini–Hochberg test (cutoff: p < 0.001 and q < 0.03), which revealed 2361 genes differentially expressed between nOPCs and aOPCs (with fold changes up to 100 for the highly differentially expressed genes) but only 37 genes differentially expressed between aOPCs and OLs (fold changes up to 20 for the highly differentially expressed genes). Thus, nOPCs and aOPCs have distinct gene expression profiles, with aOPCs having a profile that more closely resembles that of OLs.

Gene expression profile of aOPCs reverts to that of nOPCs following demyelination

To examine the activated aOPC transcriptome following demyelination, we isolated aOPCs from 2-month-old PDGFαR:GFP mice in which demyelination had been induced by feeding them a cuprizone diet (0.2%) for 5 weeks. In initial experiments, we showed low interindividual variability in the extent of demyelination between cuprizone-treated mice, with 93% of them having a demyelinated corpus callosum and areas of demyelination in the cerebral cortex (n = 23; Fig. 1c; Skripuletz et al., 2008; Koutsoudaki et al., 2009; Silvestroff et al., 2012). We first established that the vast majority of GFP-positive cells coexpressed NG2 in vivo (86.1 ± 9.0% in demyelinated slices; Fig. 1d). O4 expression by GFP-positive cells, assessed by flow cytometry analysis (Fig 1h,l), was not significantly different between control and demyelinating conditions (94.9 ± 1.6% and 89.7 ± 3.6%, respectively; Fig. 1j,l).

Transcriptomic analysis was performed as described above. Initial analysis revealed that aOPCs from demyelinated brains (henceforth described as “activated aOPCs”) expressed nOPC-associated genes at higher levels and OL-associated genes at lower levels than aOPCs from normal CNS (henceforth described as “nonactivated aOPCs”). For example, the expression of NG2 was increased 4.2-fold (p < 0.001) in activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated OPCs, whereas genes associated with myelination had lower levels of expression [e.g., expression was decreased by 2.6-fold (p < 0.005) and 2.8-fold (p < 0.005), respectively, for MOBP and MOG expression; Fig. 3a]. These demyelination-induced changes in aOPC gene expression are further illustrated by Volcano plot analysis, performed by plotting the fold change (log2 “ratio activated aOPCs/nonactivated aOPCs”) of genes that were differentially expressed against their significance (−log10 “p”; Fig. 3c). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the different samples further revealed the distinctive gene expression profiles of activated versus nonactivated aOPCs. The dendrogram showed that activated aOPCs were clustered in a third branch, between nonactivated aOPCs and OLs on one side, and nOPCs on the other (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that activated aOPCs have a gene expression pattern that is distinct from that of nonactivated aOPCs, reverting to a pattern of gene expression that more closely resembles that of nOPCs.

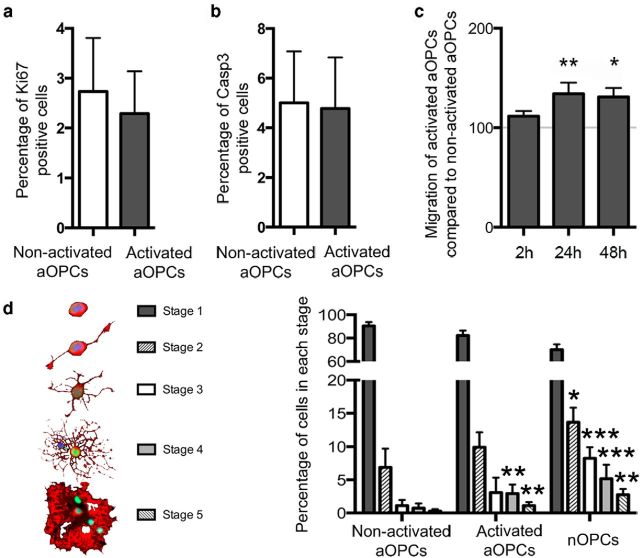

Activated aOPCs have increased migration and accelerated differentiation compared with nonactivated aOPCs

To gain insight into the functional changes conferred on aOPCs upon activation, we compared proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation rates between activated and nonactivated aOPCs in a series of cell culture assays. No differences in either the proportions of proliferative or apoptotic cells were detected (Fig. 4a,b). Migration rates were quantified using the xCELLingence Migration System wells over 2 d, showing a 1.3-fold increase in migration rate in activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated aOPCs (Fig. 4c). Since in vitro aOPCs express mature oligodendroglial markers, classifying the stages of differentiation using antigenic markers was not possible, so we therefore used a morphological classification of oligodendroglial development that was adapted from Huang et al. (2011). This analysis revealed that activated aOPCs differentiate more rapidly compared with nonactivated aOPCs (Fig. 4d). This faster rate of differentiation of activated aOPCs was similar to the rate of differentiation of nOPCs (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

In vitro functional changes in activated aOPCs. a, b, After 2 d in vitro, the proportions of activated and nonactivated aOPCs undergoing proliferation (a) and apoptosis (b) are similar. c, In vitro vertical migration assessed during a 2 d period, showing at 24 and 48 h a 1.3-fold increased migration of activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated aOPCs (n = 6; paired Student's t test). Differentiation is assessed using morphological classification (stages 1–5; adapted from Huang et al., 2011; schematic representation on the left). d, After 3 d, activated aOPCs are more differentiated than nonactivated aOPCs, with a higher proportion of cells in stages 4 and 5, a pattern ressembling nOPC differentiation (n = 3; paired Student's t test, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.005, *p < 0.05).

These results indicate that the changes in gene expression that occur upon demyelination-induced activation conferred on aOPCs increased motility and the rate of differentiation.

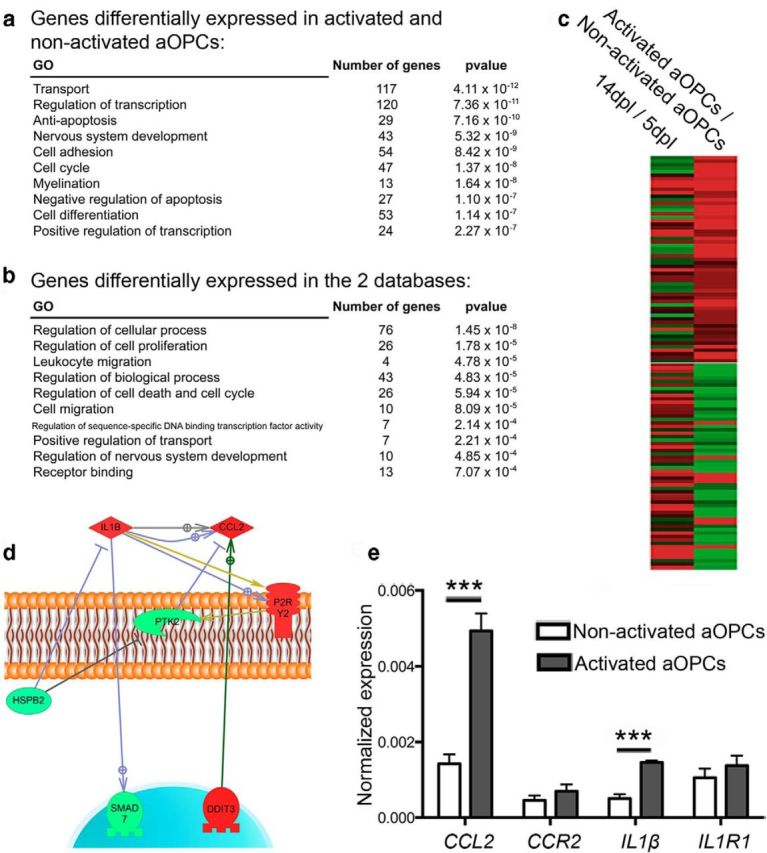

Activated aOPCs have increased expression of genes associated with innate immune system function

To identify which changes in gene expression that occur with activation might account for functional changes, we identified all genes significantly differentially expressed between activated and nonactivated aOPCs. This selection was performed using Student's t test and Benjamini–Hochberg test (cutoff: p < 0.001 and q < 0.03; Tables 1, 2). This resulted in the selection of 839 differentially expressed genes, which were then classified according to gene ontology (Fig. 5a). We then compared our data with a previously published database of gene expression occurring during remyelination of toxin-induced demyelination of adult rat CNS white matter (Huang et al., 2011), reasoning that genes with differential expression in both isolated activated aOPCs and in remyelinating lesions were likely to have functional significance. Specifically, to identify putative genes responsible for the enhanced migration of activated aOPCs, we compared our activated aOPC profile with genes that had decreased expression in the remyelination model from the stage of 14 d postlesion (dpl), when recruited OPCs are undergoing differentiation, compared with 5 dpl, when OPC recruitment is maximal. One hundred nineteen genes were differentially expressed in both databases (cutoff: q < 0.05 used for both databases; Fig. 5b,c; Table 3). Using Ariadne Genomics-Pathway Studio to identify likely genes interactions within these 119 genes, we selected the following group of 7 interacting genes: IL1β, CCL2, P2RY2, DDIT3, PTK2, HSPB2, and SMAD7. Among these seven genes, the expression of IL1β, CCL2, P2RY2, and DDIT3 was increased, whereas the expression of PTK2, HSPB2, and SMAD7 was decreased in activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated aOPCs (Fig. 5d). Within the genes with increased expression, we noted the following two genes associated with innate immune system signaling proteins: interleukin-1β [IL1β; 1.7-fold increase) and Ccl2 chemokine (CCL2, also known as MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1); 2.4-fold increase]. We confirmed the increased expression of these two genes using qPCR (2.9-fold increase of IL1β; 3.5-fold increase of CCL2). In contrast, there was no quantitative difference in mRNA levels of IL1R1 and CCR2, the two major receptors of Il1β and Ccl2, respectively (Fig. 5e).

Table 1.

The top 50 genes overexpressed in activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated aOPCs

| ID | Symbol | Gene name | Activated aOPCs/non-activated aOPCs ratio | p value* | q value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_51_P363947 | Cdkn1a | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21) | 176.23 | 1.00E-05 | 0.003 |

| A_55_P1986296 | Tagln2 | Transgelin 2 | 46.53 | 0 | 0.00031 |

| A_51_P330428 | Eif4ebp1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 | 38.11 | 0 | 0.00018 |

| A_51_P519251 | Nupr1 | Nuclear protein 1 | 37.6 | 1.00E-04 | 0.00758 |

| A_55_P1959748 | Asns | Asparagine synthetase | 35.84 | 9.00E-04 | 0.02023 |

| A_66_P106661 | Slc7a1 | Solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y + system), member 1 | 28.68 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_51_P241995 | Col5a3 | Collagen, type V, α3 | 27.97 | 0 | 0.00191 |

| A_55_P1954221 | Emp1 | Epithelial membrane protein 1 | 20.78 | 1.00E-05 | 0.003 |

| A_66_P111562 | Ccnd1 | Cyclin D1 | 20.53 | 5.00E-05 | 0.00567 |

| A_51_P315904 | Gadd45g | Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible 45 γ | 20.08 | 1.00E-04 | 0.00758 |

| A_51_P392687 | Vim | Vimentin | 18.26 | 0.00021 | 0.01032 |

| A_51_P352968 | Marcks | Myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate | 18.06 | 0.00013 | 0.0085 |

| A_51_P390538 | Mpeg1 | Macrophage expressed gene 1 | 17.13 | 0.00058 | 0.01618 |

| A_51_P131408 | Tnfrsf12a | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a | 16.75 | 2.00E-05 | 0.00343 |

| A_51_P102789 | C1qc | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, C chain | 15.89 | 0.00032 | 0.01265 |

| A_52_P1197913 | Gadd45b | Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible 45 β | 15.34 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_55_P2033376 | 1810041L15Rik | RIKEN cDNA 1810041L15 gene | 13.55 | 0.00344 | 0.0421 |

| A_51_P110759 | Slc1a1 | Solute carrier family 1 (neuronal/epithelial high-affinity glutamate transporter, system Xag), member 1 | 12.9 | 0.00116 | 0.02318 |

| A_55_P2064547 | Tuba1c | Tubulin, α1C | 12.28 | 0.00035 | 0.01296 |

| A_55_P2068892 | Il6ra | Interleukin 6 receptor, α | 12.03 | 5.00E-05 | 0.00545 |

| A_51_P359636 | Lgals3bp | Lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 binding protein | 12.01 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_55_P2345853 | 3200002M19Rik | RIKEN cDNA 3200002M19 gene | 11.86 | 6.00E-04 | 0.01648 |

| A_55_P2165869 | Cebpb | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), β | 11.7 | 0.00079 | 0.01914 |

| A_55_P2121608 | Sox4 | SRY-box containing gene 4 | 11.43 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_66_P135173 | 9630013A20Rik | RIKEN cDNA 9630013A20 gene | 11.23 | 0.00038 | 0.01363 |

| A_55_P2000439 | Ptprz1 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type Z, polypeptide 1 | 11.23 | 0.00382 | 0.04504 |

| A_55_P1971599 | Bcan | Brevican | 11.09 | 0.00013 | 0.00837 |

| A_51_P246317 | Mt2 | Metallothionein 2 | 11.03 | 0.00042 | 0.01385 |

| A_51_P106059 | Traf4 | TNF receptor-associated factor 4 | 11.02 | 0.00198 | 0.03076 |

| A_55_P2162204 | Kctd15 | Potassium channel tetramerization domain containing 15 | 10.89 | 2.00E-05 | 0.00398 |

| A_55_P2162910 | Rtn1 | Reticulon 1 | 10.8 | 0.00015 | 0.0089 |

| A_55_P2024888 | Ctss | Cathepsin S | 10.75 | 0.00278 | 0.03756 |

| A_51_P474459 | Socs3 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 10.67 | 5.00E-05 | 0.00575 |

| A_51_P501844 | Cyp26b1 | Cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 | 10.59 | 0.00127 | 0.02434 |

| A_55_P2122020 | Klf4 | Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut) | 10.32 | 2.00E-05 | 0.00381 |

| A_55_P2105858 | Atf5 | Activating transcription factor 5 | 10.27 | 0 | 0.00012 |

| A_66_P126332 | Zfp703 | Zinc finger protein 703 | 10.12 | 0.00041 | 0.01382 |

| A_55_P2121856 | Ier5l | Immediate early response 5-like | 9.93 | 0.00046 | 0.01449 |

| A_51_P421140 | Tubb6 | Tubulin, β6 | 9.87 | 0.00023 | 0.01097 |

| A_51_P102789 | C1qc | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, C chain | 9.84 | 0.00378 | 0.04483 |

| A_55_P1971963 | Tmem176b | Transmembrane protein 176B | 9.62 | 0.00278 | 0.03756 |

| A_51_P258690 | Scrg1 | Scrapie responsive gene 1 | 9.61 | 0.00013 | 0.00835 |

| A_55_P1999902 | 9.6 | 4.00E-05 | 0.00485 | ||

| A_52_P597634 | Fzd1 | Frizzled homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 9.59 | 0.00013 | 0.00836 |

| A_55_P2098598 | Btg1 | B-cell translocation gene 1, anti-proliferative | 9.54 | 0.00029 | 0.01189 |

| A_55_P2003541 | Nrcam | Neuron-glia-CAM-related cell adhesion molecule | 9.53 | 1.00E-05 | 0.00333 |

| A_65_P19395 | H2-D1 | Histocompatibility 2, D region locus 1 | 9.12 | 3.00E-05 | 0.00436 |

| A_51_P159453 | Serpina3n | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3N | 9 | 0.00228 | 0.0336 |

| A_55_P1953728 | Nes | Nestin | 8.75 | 0.00016 | 0.00914 |

| A_51_P502614 | Dusp6 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 | 8.72 | 1.00E-04 | 0.00758 |

* Student's t test.

† Benjamini–Hochberg test.

Table 2.

The top 50 genes overexpressed in nonactivated aOPCs compared with activated aOPCs

| ID | Symbol | Gene name | Nonactivated aOPCs/activated aOPCs ratio | p value* | q value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_52_P373694 | Jph4 | Junctophilin 4 | 20.00 | 1.00E-05 | 0.00278 |

| A_52_P540434 | Ppp1cc | Protein phosphatase 1, catalytic subunit, γ isoform | 12.50 | 0.00156 | 0.02709 |

| A_55_P2146520 | Carns1 | Carnosine synthase 1 | 11.11 | 0.00163 | 0.02758 |

| A_55_P1984655 | Smtnl2 | Smoothelin-like 2 | 11.11 | 0.0016 | 0.02743 |

| A_55_P1955869 | Gm9315 | Predicted gene 9315 | 10.00 | 9.00E-05 | 0.00734 |

| A_51_P105927 | Rasl12 | RAS-like, family 12 | 10.00 | 4.00E-05 | 0.00486 |

| A_66_P122613 | 9630009A06Rik | RIKEN cDNA 9630009A06 gene | 9.09 | 0.00516 | 0.05202 |

| A_55_P2044389 | Kif6 | Kinesin family member 6 | 9.09 | 0.00013 | 0.00842 |

| A_51_P246166 | Expi | Extracellular proteinase inhibitor | 8.33 | 0.00201 | 0.03104 |

| A_51_P348433 | Rasal1 | RAS protein activator like 1 (GAP1 like) | 8.33 | 0.00072 | 0.0182 |

| A_55_P2148624 | Gpr61 | G-protein-coupled receptor 61 | 7.69 | 1.00E-05 | 0.00306 |

| A_55_P1996674 | Itih3 | Inter-α trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 3 | 7.69 | 0.00061 | 0.0166 |

| A_55_P1959485 | LOC634933 | 7.69 | 6.00E-05 | 0.00643 | |

| A_55_P2011286 | Hopx | HOP homeobox | 7.14 | 0.00218 | 0.03261 |

| A_55_P2149942 | Ninj2 | Ninjurin 2 | 7.14 | 8.00E-04 | 0.01926 |

| A_55_P2005859 | Fn3k | Fructosamine 3 kinase | 6.67 | 0.00371 | 0.04446 |

| A_55_P2042923 | Sgk2 | Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 2 | 6.67 | 4.00E-05 | 0.00494 |

| A_55_P2243883 | B230117O15Rik | RIKEN cDNA B230117O15 gene | 6.25 | 0.00021 | 0.01051 |

| A_51_P285077 | Hhatl | Hedgehog acyltransferase-like | 6.25 | 0.00178 | 0.02897 |

| A_51_P430973 | Paqr7 | Progestin and adipoQ receptor family member VII | 6.25 | 0.00508 | 0.05151 |

| A_51_P200561 | 4930506M07Rik | RIKEN cDNA 4930506M07 gene | 5.88 | 0.00045 | 0.01418 |

| A_66_P114381 | Ypel2 | Yippee-like 2 (Drosophila) | 5.88 | 0.00195 | 0.03047 |

| A_55_P2268022 | 9330199G10Rik | RIKEN cDNA 9330199G10 gene | 5.56 | 0.0092 | 0.07041 |

| A_55_P2006525 | Adamtsl4 | ADAMTS-like 4 | 5.56 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_52_P559545 | Cercam | Cerebral endothelial cell adhesion molecule | 5.56 | 0.00177 | 0.02879 |

| A_51_P316553 | Kdr | Kinase insert domain protein receptor | 5.56 | 0.00032 | 0.01261 |

| A_55_P2012430 | LOC100045251 | 5.56 | 0.00176 | 0.02871 | |

| A_55_P2142072 | Synj2 | Synaptojanin 2 | 5.56 | 0.00098 | 0.02134 |

| A_55_P2039606 | 5.56 | 0.00055 | 0.01597 | ||

| A_55_P2022870 | 5.56 | 0.00254 | 0.03577 | ||

| A_55_P2076994 | Defa-rs10 | Defensin-α-related sequence 10 | 5.26 | 0.00716 | 0.06191 |

| A_55_P2004159 | LOC100039646 | 5.26 | 0.00053 | 0.0156 | |

| A_55_P1983999 | Pppde2 | PPPDE peptidase domain containing 2 | 5.26 | 0.00013 | 0.00857 |

| A_51_P104710 | Sspo | SCO-spondin | 5.26 | 0.00986 | 0.07278 |

| A_55_P1984976 | Wnt5b | Wingless-related MMTV integration site 5B | 5.26 | 0.00087 | 0.02004 |

| A_55_P2121352 | Cdk5 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | 5.00 | 0.00078 | 0.0191 |

| A_55_P2227321 | Ptprd | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, D | 5.00 | 0.00028 | 0.01178 |

| A_52_P563825 | B3galt1 | UDP-Gal:βGlcNAc β 1,3-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide 1 | 4.76 | 0.00016 | 0.00898 |

| A_55_P2131954 | Gm2590 | Predicted gene 2590 | 4.76 | 0.00137 | 0.02533 |

| A_52_P376169 | Lypd6 | LY6/PLAUR domain containing 6 | 4.76 | 0.00818 | 0.06634 |

| A_55_P2042356 | Rftn1 | Raftlin lipid raft linker 1 | 4.76 | 0.00105 | 0.02213 |

| A_52_P493477 | Serpinb1c | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 1c | 4.76 | 1.00E-04 | 0.00761 |

| A_51_P112762 | Slc5a3 | Solute carrier family 5 (inositol transporters), member 3 | 4.76 | 0.001 | 0.02155 |

| A_55_P1954680 | B230206H07Rik | RIKEN cDNA B230206H07 gene | 4.55 | 0.00136 | 0.02528 |

| A_55_P2102515 | Daam1 | Disheveled associated activator of morphogenesis 1 | 4.55 | 0.00049 | 0.01505 |

| A_51_P349495 | Mboat1 | Membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 1 | 4.55 | 0.00347 | 0.04233 |

| A_55_P1991164 | Mlc1 | Megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts 1 homolog (human) | 4.55 | 0.00112 | 0.02296 |

| A_52_P497188 | Prrg1 | Proline-rich Gla (G-carboxyglutamic acid) 1 | 4.55 | 0 | 0.0019 |

| A_55_P2088965 | Scarb1 | Scavenger receptor class B, member 1 | 4.55 | 0.00836 | 0.06713 |

| A_55_P2121165 | Tmeff1 | Transmembrane protein with EGF-like and two follistatin-like domains 1 | 4.55 | 0.00116 | 0.02318 |

* Student's t test.

† Benjamini–Hochberg test.

Figure 5.

Biostatistical analysis to identify genes of interest. a, Gene ontology performed on GOrilla software for all genes differentially expressed between activated aOPCs and nonactivated aOPCs. b, Gene ontology for genes differentially expressed in activated aOPCs versus those in the nonactivated aOPC database and in the reported early repair database of caudal cerebellar peduncle (CCP) lesions comparing 14 versus 5 dpl. c, Representation of the 119 genes differentially expressed in both databases. d, Identification of a group of seven interacting genes, using Ariadne Genomics–Pathway Studio. e, qPCR detection of CCL2, CCR2, IL1β, and IL1R1 on activated aOPCs and nonactivated aOPCs. qPCR showing CCL2 and IL1β expression in activated aOPCs (n = 4; Student's t test, ***p < 0.001).

Table 3.

The 119 genes differentially expressed in both databases

| Probe ID illumina | Gene symbol | Fold change in activated aOPC/nonactivated aOPC ratio | FDR-activated aOPC/nonactivated aOPC ratio | Fold change 14 dpl/5 dpl ratio | FDR 14 dpl/5 dpl ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILMN_51219 | Mt3 | 1.161 | 0.027 | 1.796 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_53363 | Gpd1 | 0.970 | 0.011 | 1.496 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_52937 | Nupr1 | 5.233 | 0.000 | 0.985 | 0.023 |

| ILMN_59954 | Fxyd6 | 2.061 | 0.005 | 2.297 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_58714 | Slc25a29 | 0.574 | 0.049 | 0.612 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_64674 | Crip2 | 2.135 | 0.000 | 1.715 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_58852 | Nr4a2 | 1.105 | 0.031 | 0.436 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_64905 | RGD1311433 | 0.557 | 0.045 | 0.340 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_53779 | Mpg | 0.776 | 0.034 | 0.343 | 0.010 |

| ILMN_53158 | RGD1308093 | 0.007 | 0.033 | 0.371 | 0.009 |

| ILMN_68876 | NA | 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.421 | 0.009 |

| ILMN_48674 | Fzd1 | 3.262 | 0.000 | 0.423 | 0.040 |

| ILMN_49747 | Cirbp | 1.768 | 0.006 | 0.451 | 0.033 |

| ILMN_60518 | Timp3 | 2.659 | 0.002 | 0.461 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_66452 | Phlda1 | 1.194 | 0.003 | 0.519 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_69826 | Tnfrsf12a | 4.066 | 0.000 | 0.690 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_63705 | Gadd45a | 2.373 | 0.001 | 0.759 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_53681 | RGD1561238 | 0.638 | 0.001 | 0.791 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_57274 | Ngfr | 0.871 | 0.040 | 0.855 | 0.009 |

| ILMN_53094 | NA | 1.256 | 0.004 | 0.875 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_51692 | Hbegf | 1.236 | 0.009 | 0.954 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_54579 | Cspg4 | 2.057 | 0.001 | 0.964 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_49640 | Ddit4 | 1.220 | 0.007 | 1.059 | 0.014 |

| ILMN_66374 | Lmo4 | 2.720 | 0.000 | 1.073 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_47800 | Fabp7 | 1.585 | 0.010 | 1.152 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_52596 | Col1a2 | 1.394 | 0.004 | 1.197 | 0.020 |

| ILMN_56986 | Scg3 | 0.834 | 0.014 | 1.535 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_52684 | Col5a3 | 4.806 | 0.000 | 1.601 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_55428 | Csrp2 | 1.042 | 0.012 | 1.993 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_58726 | Gas6 | 0.885 | 0.011 | 2.400 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_69972 | Sparcl1 | 0.518 | 0.034 | 2.517 | 0.011 |

| ILMN_67000 | NA | 0.921 | 0.021 | 0.876 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_70091 | Lipa | −1.234 | 0.008 | −0.577 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_54243 | Birc2 | −1.350 | 0.009 | −1.605 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_52565 | Myadm | −1.113 | 0.049 | −0.971 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_57271 | Faim | −0.764 | 0.033 | −0.765 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_63415 | Nfe2l2 | −0.652 | 0.020 | −0.593 | 0.014 |

| ILMN_58795 | Atp6ap2 | −0.659 | 0.042 | −0.517 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_59859 | Arfgef2 | −1.117 | 0.044 | −0.496 | 0.022 |

| ILMN_48347 | Xpo1 | −0.800 | 0.028 | −0.468 | 0.030 |

| ILMN_51090 | RGD1561318 | −0.985 | 0.003 | −0.465 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_52394 | Gyg1 | −0.893 | 0.016 | −0.385 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_57554 | Tmem49 | −0.887 | 0.006 | −0.360 | 0.020 |

| ILMN_55052 | Fpgt | −0.568 | 0.029 | −0.358 | 0.008 |

| ILMN_51657 | Bmp2k | −1.018 | 0.004 | −0.354 | 0.042 |

| ILMN_62852 | M6prbp1 | −0.982 | 0.023 | −0.353 | 0.032 |

| ILMN_55477 | RGD1561318 | −1.285 | 0.010 | −0.314 | 0.023 |

| ILMN_65955 | Slc26a11 | −1.416 | 0.019 | −0.286 | 0.012 |

| ILMN_69380 | Hapln2 | −0.787 | 0.029 | −0.913 | 0.018 |

| ILMN_53575 | LOC100362769 | 0.343 | 0.010 | −0.499 | 0.036 |

| ILMN_54331 | Slc38a1 | 2.431 | 0.000 | −0.600 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_61673 | P2ry2 | 1.746 | 0.047 | −1.288 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_69830 | Ddit3 | 2.473 | 0.001 | −0.655 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_70092 | Arf6 | 1.550 | 0.004 | −0.556 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_63004 | NA | 2.659 | 0.031 | −0.713 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_58897 | Emb | 1.531 | 0.035 | −1.498 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_56900 | Acaa2 | 1.605 | 0.001 | −0.624 | 0.036 |

| ILMN_55502 | C1qc | 3.990 | 0.001 | −0.711 | 0.048 |

| ILMN_50644 | Il1b | 1.669 | 0.037 | −2.340 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_68242 | Ccl2 | 2.396 | 0.001 | −1.441 | 0.007 |

| ILMN_60683 | RGD1309759 | 1.394 | 0.010 | −1.179 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_48844 | Fam3c | 1.370 | 0.021 | −1.063 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_52928 | Anxa5 | 1.065 | 0.005 | −0.810 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_60037 | Lgals3bp | 3.586 | 0.000 | −0.803 | 0.008 |

| ILMN_59873 | Sdad1 | 0.616 | 0.023 | −0.791 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_58534 | Impa2 | 1.511 | 0.050 | −0.759 | 0.012 |

| ILMN_67102 | Naprt1 | 1.261 | 0.018 | −0.700 | 0.003 |

| ILMN_62651 | Eif4ebp1 | 5.252 | 0.000 | −0.698 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_66666 | NA | 1.732 | 0.012 | −0.591 | 0.037 |

| ILMN_53677 | Scamp2 | 0.477 | 0.050 | −0.537 | 0.005 |

| ILMN_60223 | Gsto1 | 2.157 | 0.003 | −0.524 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_50677 | Sh3bp4 | 0.903 | 0.039 | −0.504 | 0.036 |

| ILMN_61212 | Mad2l1bp | 0.509 | 0.046 | −0.503 | 0.009 |

| ILMN_51505 | Txnrd1 | 0.862 | 0.014 | −0.415 | 0.030 |

| ILMN_50573 | Serp1 | 0.781 | 0.021 | −0.289 | 0.036 |

| ILMN_61404 | Cst3 | 1.121 | 0.011 | −0.231 | 0.046 |

| ILMN_48324 | Sbds | −0.601 | 0.048 | 0.460 | 0.010 |

| ILMN_61670 | Carhsp1 | −0.680 | 0.015 | 0.489 | 0.008 |

| ILMN_48913 | Hspb2 | −0.503 | 0.043 | 0.584 | 0.009 |

| ILMN_63175 | Abca2 | −1.737 | 0.007 | 0.597 | 0.020 |

| ILMN_58653 | Cldnd1 | −0.550 | 0.039 | 0.600 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_53618 | Clcn2 | −1.377 | 0.011 | 0.611 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_56148 | Atrn | −0.540 | 0.039 | 0.638 | 0.006 |

| ILMN_54730 | Pomgnt1 | −0.972 | 0.008 | 0.673 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_57175 | Phlpp1 | −0.985 | 0.013 | 0.746 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_55608 | Arl2 | −0.860 | 0.024 | 0.786 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_63002 | Apln | −1.388 | 0.005 | 0.816 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_53865 | NA | −0.659 | 0.050 | 0.883 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_55899 | Fntb | −1.130 | 0.021 | 0.892 | 0.001 |

| ILMN_57086 | Slc44a1 | −0.803 | 0.010 | 1.022 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_56690 | Prkcz | −1.349 | 0.003 | 1.050 | 0.015 |

| ILMN_60295 | Myo1d | −1.772 | 0.029 | 1.133 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_47781 | Cdc42ep2 | −1.084 | 0.010 | 1.256 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_56537 | Tppp3 | −1.099 | 0.010 | 1.316 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_48166 | Aldh1a1 | −1.820 | 0.009 | 1.630 | 0.030 |

| ILMN_61133 | Jam3 | −1.128 | 0.003 | 2.144 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_65657 | Pafah1b2 | −1.285 | 0.013 | 0.286 | 0.026 |

| ILMN_66755 | NA | −1.007 | 0.005 | 0.289 | 0.013 |

| ILMN_57177 | Ppp2r5b | −0.544 | 0.034 | 0.299 | 0.040 |

| ILMN_53817 | Rbbp6 | −1.053 | 0.050 | 0.315 | 0.020 |

| ILMN_56707 | Zfp354a | −0.983 | 0.019 | 0.343 | 0.012 |

| ILMN_64783 | Ermp1 | −1.007 | 0.005 | 0.387 | 0.044 |

| ILMN_55879 | Klhl2 | −0.799 | 0.012 | 0.417 | 0.014 |

| ILMN_48256 | Smad7 | −1.237 | 0.002 | 0.465 | 0.004 |

| ILMN_52620 | Fam115a | −0.799 | 0.029 | 0.493 | 0.035 |

| ILMN_52044 | LOC100365024 | −1.130 | 0.028 | 0.498 | 0.034 |

| ILMN_68931 | Ptk2 | −1.832 | 0.021 | 0.537 | 0.042 |

| ILMN_63713 | Epdr1 | −0.836 | 0.010 | 0.547 | 0.036 |

| ILMN_58939 | Lrig3 | −0.856 | 0.023 | 0.577 | 0.019 |

| ILMN_55683 | NA | −0.802 | 0.013 | 0.654 | 0.010 |

| ILMN_67298 | Thra_v2 | −1.409 | 0.019 | 0.733 | 0.020 |

| ILMN_56830 | Znf536 | −0.894 | 0.014 | 0.968 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_69891 | Prkcq | −0.683 | 0.021 | 0.976 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_60293 | Frmd8 | −0.913 | 0.006 | 0.987 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_161522 | Tmem98 | −0.860 | 0.021 | 0.993 | 0.002 |

| ILMN_59078 | Tmprss5 | −1.121 | 0.010 | 1.181 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_56185 | Tmem98 | −1.482 | 0.002 | 1.233 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_61041 | Bpgm | −0.887 | 0.015 | 1.369 | 0.000 |

| ILMN_64748 | Ndrg2 | −0.637 | 0.015 | 1.764 | 0.024 |

Ratios and q values by Benjamini–Hochberg test in both databases. FDR, False discovery rate.

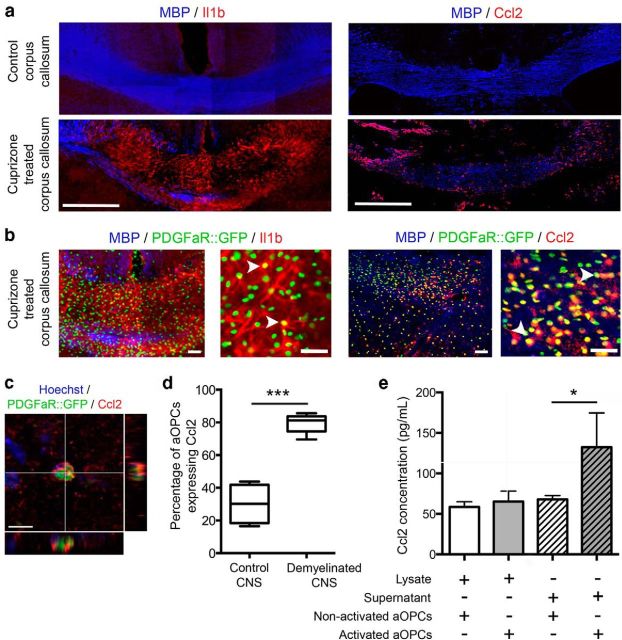

Ccl2 expression is increased within areas of cuprizone-induced demyelination

We next asked whether Ccl2 and Il1β were expressed by aOPCs in vivo in normal and demyelinated white matter of PDGFαR:GFP transgenic mice. By immunohistochemistry, increased Il1β and Ccl2 expression was detected in demyelinated areas, compared with control brain sections (Fig. 6a). As the expression of Il1β was mostly diffuse, quantification of the proportion aOPCs expressing Il1β in demyelinated tissue was difficult (Fig. 6b). The percentage of GFP-positive aOPCs expressing Ccl2 (Fig. 6b,c) increased from 30.1 ± 6.1% to 79.3 ± 2.0% between control and demyelinated brain areas (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

In vivo Il1β and Ccl2 expression by aOPCs in control and cuprizone-treated PDGFαR:GFP adult mice. a, Immunostaining on coronal brain sections of control and cuprizone-treated PDGFαR::GFP adult mice showing increased numbers of aOPCs (GFP-positive cells) in the demyelinated area (corpus callosum) associated with increased expression of Il1β and Ccl2. Scale bar, 200 μm. b, Higher-magnification image showing GFP-positive aOPCs expressing Il1β and Ccl2 (white arrowheads). Scale bar, 50 μm. c, A GFP-positive cell expressing Ccl2. Scale bar, 10 μm. d, Quantification of the percentage of aOPCS expressing Ccl2 showing a 2.5-fold increase after demyelination (n = 5; Student's t test ***p < 0.001). e, ELISA performed on lysates and supernatants of purified aOPCs from control and demyelinated brains showing a twofold increase of Ccl2 secretion by activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated aOPCs (Student's t test, *p < 0.05).

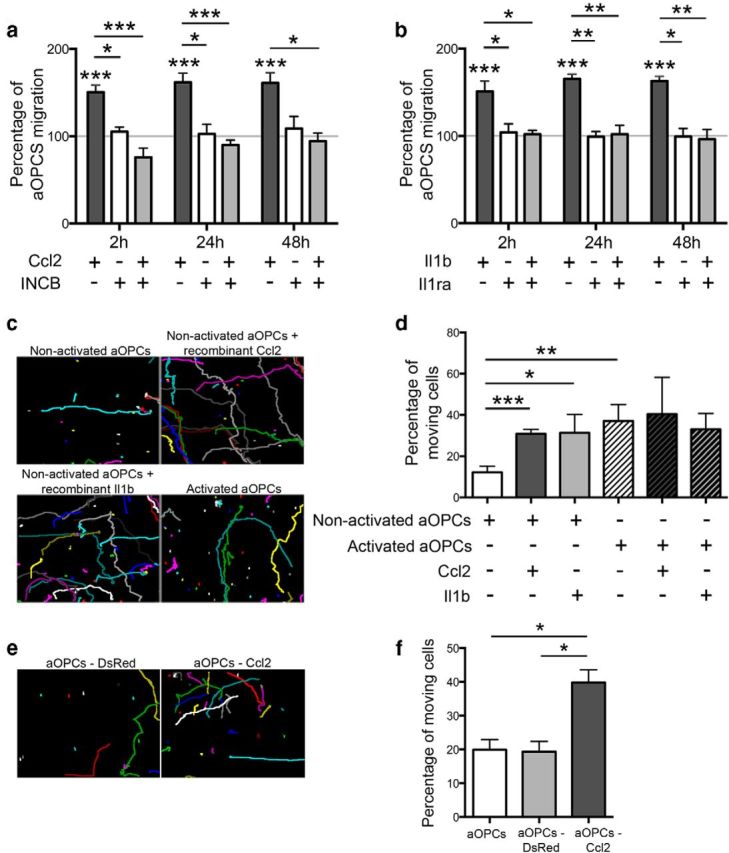

Il1β and Ccl2 increase adult OPCs migration in vitro

To assess the effects of Il1β and Ccl2 on nonactivated aOPCs, cells were cultured with different concentrations of Il1β recombinant protein (2, 5, and 10 ng/ml) or Ccl2 recombinant protein (2, 10, and 20 ng/ml). Proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation were not altered by Il1β or Ccl2 (data not shown). However, 20 ng/ml Ccl2 caused a significant increase in aOPC migration, which was reversed by the specific Ccr2 receptor antagonist INCB (Fig. 7a). Similarly, 5 ng/ml Il1β also caused an increase in aOPC migration, which was repressed by the Il1β receptor antagonist Il1ra (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

Influence of Il1β and Ccl2 on aOPC migration in vitro. a, b, Soluble Ccl2 (20 ng/ml) and Il1β (5 ng/ml) increase aOPC migration, compared with control in a vertical migration system. This effect is blocked by the respective antagonists INCB (for Ccl2, 8 μm) and Il1ra1 (for Il1β, 200 ng/ml; Student's t test, *p < 0.01, **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.001). c, d, Horizontal migration assessed by video microscopy (each colored spot represents a single cell track, c) showing that nonactivated aOPCs treated by soluble Ccl2 or Il1β become as mobile as activated aOPCs (treated or not with Ccl2 or Il1β; d). e, f, A similar increase is induced by lentiviral-mediated overexpression of Ccl2 (aOPCs-Ccl2) compared with control vector (aOPCs-DsRed; n = 3; Student's t test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.002).

Using videomicroscopy, we followed the motion of individual aOPCs over a 24 h period (Fig. 7c). This revealed that the addition of Ccl2 and Il1β increased the percentage of motile aOPCs (30.8 ± 2.2%, p < 0.005; and 31.3 ± 8.9%, p < 0.05, respectively), compared with nontreated cells (12.2 ± 2.9%). Indeed, Ccl2- and Il1β-treated nonactivated aOPCs become as mobile as activated aOPCs [activated aOPCs, 37.0 ± 7.9% (p < 0.01), which is not further increased by Ccl2 or Il1β treatment; Fig. 7c,d]. The chemokinetic effect of neither agent was associated with changes in velocity (mean velocity, 3.7 ± 1.1 mm/week for each condition).

We next showed, using ELISA of the supernatant of cultured aOPCs, that the Ccl2 secretion was significantly greater in activated aOPCs compared with nonactivated OPCs (132.2 ± 42.4 and 67.8 ± 4.9 pg/ml, respectively; p < 0.05; Fig. 6e). We were unable to detect Il1β in supernatants of either cultured activated or nonactivated OPCs. For this reason, our subsequent studies focused on Ccl2.

These data suggest a model in which aOPCs respond to demyelination by increasing the expression of Ccl2 and (possibly) Il1β, which, by enhancing their motility, enable them to populate areas of demyelination more efficiently.

Overexpression of Ccl2 in aOPCs results in increased migration

To assess whether aOPC migration could be enhanced by increasing the expression of Ccl2, cells were isolated from the brains of PDGFαR:GFP mice and transduced with either a lentiviral vector expressing Ccl2 linked to mCherry fluorescent protein (CMV_CCL2-2A-mCherry) or a control vector expressing a myc-tagged DsRed fluorescent protein (CMV_DsRed-Myc). After 4 d in culture, GFP-positive/mCherry-positive and GFP-positive/DsRed-positive cells were FAC sorted and replated, where their individual migrations were followed by videomicroscopy over a 24 h period (Fig. 7e). Nontransduced aOPCs and aOPCs transduced with the control lentivirus (aOPCs-DsRed) had similar percentages of motile cells (19.9 ± 3.0% and 19.3 ± 3.0%, respectively), while the aOPCs transduced with the CMV_CCL2-2A-mCherry lentiviral vector (aOPCs-Ccl2) had a significantly increased percentage of motile cells (39.8 ± 3.7%; p < 0.05; Fig. 7f).

We next asked whether aOPCs transduced to express Ccl2 would exhibit enhanced migration following transplantation into the neonatal mouse brain. Since we were unable to obtain sufficient numbers of transduced primary aOPCs for transplantation, we instead used the CG4 cell line that reliably mimics the behavior of primary OPCs following transplantation (Franklin et al., 1995). Approximately 80% of the CG4 cells were transduced at 3 d postinfection with increased CCL2 detected by qPCR (Fig. 8c), allowing us to sort mCherry-positive or DsRed-positive cells, and to graft these transduced cells into the corpus callosum of neonatal PDGFαR:GFP mouse pups (Fig. 8a,d). We confirmed that CG4 cells were not affected by lentivirus transduction: transduced or nontransduced CG4 cells are immature progenitors, expressing PDGFαR and O4, but not MBP (Fig. 8b). We have also checked that nontransduced CG4 cells, as well as CG4 cells transduced with control or Ccl2_mCherry lentivirus, express Ccr2 (data not shown). No difference in the maximal distance of migration was observed between CG4 cells transduced with the control lentivirus (CG4-DsRed) and CG4 cells expressing Ccl2 (CG4-Ccl2) at 40 h after grafting (Fig. 8e). However, a significantly increased number of CG4-Ccl2 cells had migrated from the site of injection compared with the control CG4-DsRed (Fig. 8f), whereas proliferation rate was similar (Fig. 8g).

Figure 8.

Influence of Ccl2 on aOPC migration in vivo. a, Four days after transduction, CG4 transduced with the control (CG4-DsRed) or with the Ccl2 lentivirus (CG4-Ccl2, tagged with mCherry) were sorted. b, CG4 cells were plated and immunostained 4 d after transduction. Scale bar, 50 μm. Nontransduced and transduced CG4 cells express immature markers PDGFαR, A2B5, and O4, but not the mature marker MBP. c, qPCR detection of CCL2 on nontransduced CG4 cells and transduced CG4 cells (CG4-DSRed or CG4-Ccl2). CCL2, expressed at a low level in nontransduced cells, is increased after transduction with the Ccl2 lentivirus (n = 3; Student's t test, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05). Sorted cells are injected in P2 PDGFαR:GFP brains. d, The circles represent distances. Scale bar, 200 μm. Red arrow represents the injection track, the inner circle represents the injection site. CC, Corpus callosum. e, No difference in the distance of migration [dorsoventral (DV), anteroposterior (AP), and lateral (Lateral)] was detected between CG4-DsRed and CG4-Ccl2 cells. f, g, Quantification of the percentage of transduced CG4 cells, which have migrated at different distances from the injection site: CG4-Ccl2 cells are more migratory compared to CG4-DsRed cells (f), without difference in the percentage of proliferating cells (g; n = 3; Student's t test, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

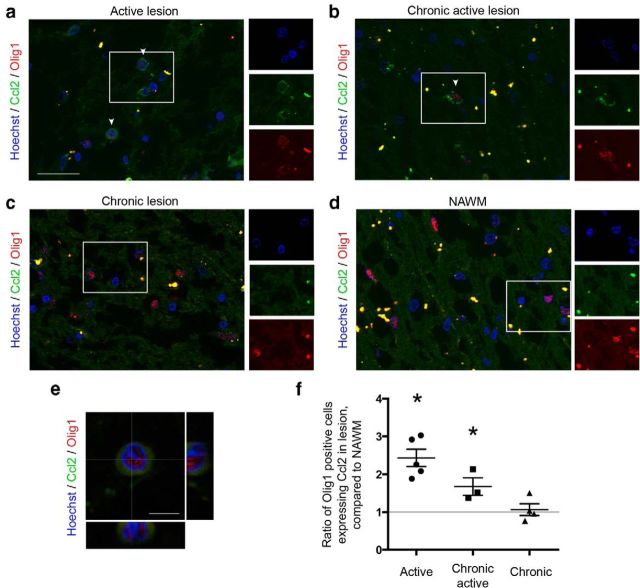

Ccl2 is expressed within active MS plaque OPCs

We analyzed Ccl2 expression within active regions of MS plaques (i.e., either active plaques or the active border of chronic lesions; see lesion classification in Materials and Methods), and within chronic lesions or NAWM. OPCs were identified by nuclear Olig1 staining. Within active areas, 3–5% of OPCs expressed Ccl2 (Fig. 9a,b,e), whereas only 1–2% were detected in chronic lesions and NAWM (Fig. 9c,d). Quantification was performed by comparing each MS lesion to adjacent NAWM of the same size (see Materials and Methods). In active MS plaques and the active border of chronic plaques, a 2.4- and 1.7-fold increase of Ccl2-expressing OPCs was detected. In contrast, within chronic plaques, no significant difference was detected (Fig. 9f).

Figure 9.

a, b, Ccl2 immunostaining on MS tissues. OPCs (nuclear Olig1 staining) expressing Ccl2 (arrowhead) in an active lesion (a) and active borders of a chronic lesion (b). c, d, Virtually no Ccl2-expressing OPCs in a chronic lesion (c) or NAWM area (d). Scale bar, 50 μm. e, High-magnification image of one OPCs, stained by nuclear Olig1 antibody (red), expressing Ccl2 (green). Scale bar, 10 μm. f, Ratio of the percentage of nuclear Olig1-positive cells expressing Ccl2 in multiple sclerosis lesions, compared to adjacent NAWM of the same size (n = 3–6, depending on the type of lesion; one-way ANOVA and Holm–Sidak multiple-comparisons test, *p < 0.05).

Discussion

Using a microarray screen on purified populations of cells of the oligodendroglial lineage, we have been able to specifically analyze the aOPC population and gain insights into intrinsic changes distinguishing demyelination (i.e., distinguishing activated aOPCs from nonactivated aOPCs). We first demonstrated that aOPCs have a more mature transcriptome than nOPCs. These results corroborate previous reports showing that adult O4-positive cells have higher levels of transcripts for myelin genes compared with neonatal O4-positive cells (Lin et al., 2009). It has been suggested that myelin-associated proteins inhibit OPC differentiation, in part, by suppressing the expression of Nkx2.2, which could explain the maintenance of undifferentiated aOPCs in adult brains (Robinson and Miller, 1999; Syed et al., 2008). This mature pattern of aOPC gene expression is also evident from a comparison with the mRNA profile of OLs sorted from PLP:GFP transgenic lines. A much lower number of genes (37 genes) are differentially regulated between the two cell types, compared with the high number of genes (2361 genes) differentially regulated between aOPCs and nOPCs. A major issue for the microarray data validation was to ascertain that the sorted cell populations from adult PLP-GFP and PDGFαR:GFP brains corresponded to populations of OLs and OPCs, respectively. Since aOPCs express PLP transcripts, one caveat might have been the possibility that sorting from adult PLP-GFP transgenic lines results in the isolation of a mixed population of OLs and aOPCs. This possibility was ruled out by the fact that sorted PLP-GFP OLs do not express immature markers NG2 or PDGFαR (which are expressed by aOPCs). Furthermore, as we could not rule out that some GFP-expressing cells in the adult brain of PDGFαR:GFP mice were already differentiated oligodendrocytes, while retaining GFP expression, we assessed the in vivo expression of NG2, a progenitor marker. Whereas 91.7% of all GFP-positive cells express NG2, some low GFP expressing cells were NG2 negative, suggesting that these were differentiating cells. We then confirmed that all sorted cells expressed NG2.

Sorted aOPCs express MBP, a marker of mature oligodendrocytes. Although we cannot rule out that MBP expression is “artificially” induced by the cellular stress related to the isolation procedure, these data are in line with the microarray data, but also with previously published data (Li et al., 2002; Ruffini et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2009), showing the expression of different mature markers by OPCs in the adult CNS. Nevertheless, we were unable to detect MBP expression on PDGFαR::GFP-positive cells in vivo, suggesting the low expression of the protein.

Using the cuprizone model, we showed that aOPCs revert to a more immature mRNA expression profile after demyelination and acquire new capacities. To further validate that GFP-positive cells were corresponding to adult OPCs in demyelinated CNS, we have assessed in vivo that, as under control conditions, the GFP-positive cells expressed NG2. In addition, although we cannot exclude the idea that a small proportion of activated cells are newly generated from the germinal zone of cuprizone-treated brains, GFP-positive cells were disseminated within the whole white matter of cuprizone-treated mice, suggesting that sorted cells were mostly “local” aOPCs rather than aOPCs newly generated from activated neural stem cells.

Several previous studies have analyzed gene expression profiles in CNS demyelinating lesions, but none focused on a single cell population (Jurevics et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2011). Using a rat model of toxin-induced demyelination, Fancy et al., 2009 reported that ∼50 transcription factor-encoding genes show dynamic expression during remyelination including the Wnt pathway mediator Tcf4, leading to the identification of a major negative regulator of OPC differentiation. Analyzing gene expression profiles of the separate stages of spontaneous remyelination in a related model led to the identification of the retinoid acid receptor RXRγ as a major positive regulator of OPC differentiation (Huang et al., 2011).

Using isolated cells maintained in tissue culture, we found that activated aOPCs acquire new capacities for migration and differentiation. We showed that this increased migration corresponds to a chemokinetic effect, with an increased percentage of mobile adult OPCs, without change in the speed of migration. Therefore, aOPCs acquire increased migration and differentiation capacity, both parameters being crucially needed after a demyelinating insult, to reach the demyelinating area and initiate the regenerative process during a window of time when axonal damage is still reversible.

In the cuprizone model, where demyelination and remyelination often occur contemporaneously, it is hazardous to correlate mRNA gene expression changes to a particular stage of the regenerative process. Therefore, to select genes of interest, we took advantage of a gene expression database obtained in a different experimental model, allowing us to distinguish the separate stages of spontaneous remyelination (Huang et al., 2011). In this study, mRNAs were extracted from microdissected lesions that included different cell populations. Our strategy has therefore been to compare our aOPC-specific database and the “early repair database” (14 vs 5 dpl), and to select genes differentially expressed in both databases, which resulted in the identification of 119 genes. These were further analyzed to identify interacting genes, from which emerged two genes of the innate immune system, IL1β and CCL2. We showed that both Ccl2 and Il1β influenced the motility of aOPCs through Ccr2 and Il1r1 receptors, respectively. In contrast, no effect on differentiation was detected, suggesting that, among the acquired capacities of activated OPCs, increased expression of Ccl2 and Il1β were contributing only to the increased migration. The migratory effect of Ccl2 on aOPCs, which was related neither to receptor expression nor to the stage of differentiation (data not shown), was further confirmed in vivo, using gain-of-function experiments.

Both Ccl2 and Il1β are secreted by inflammatory cells and act as chemoattractants (Matsushima et al., 1989; Rollins, 1991). The expression of Ccl2 and Il1β is increased in many different neurological diseases, among them Alzheimer's disease, CNS injury, and MS (Stefini et al., 2008; Sokolova et al., 2009; Hagman et al., 2011). In MS lesions, increased Ccl2 expression has been reported in acute and chronic lesions, and related to the activation and migration of leukocytes and microglial cells (Mahad and Ransohoff, 2003). In addition to inflammatory cells, astrocytes have been shown to express Ccl2 (Glabinski et al., 1996). Using in vitro migration assays, several groups have shown that Ccl2 increases the migration of microglia cells, macrophages, monocytes, and neural stem cells (Widera et al., 2004; Opalek et al., 2007; Hinojosa et al., 2011; Iqbal et al., 2013; Li and Tai, 2013). The expression of Il1β or Ccl2 on cells of the oligodendroglial lineage has not been previously reported. Here we show that these cytokines are expressed in aOPCs after experimental demyelination and in MS, and that this expression influences their migration capacity, in vitro and in vivo (using the CG4 oligodendroglial cell line for the grafting experiments). The migration of nonactivated aOPCs was also enhanced when Ccl2 or Il1β was added to the culture medium. However, in vitro migration of activated aOPCs was not affected by the addition of Ccl2 or Il1β, suggesting that activated aOPCs no longer rely on Ccl2 or Il1β (even self-secreted) for an enhanced migration rate. Moreover, in addition to an autocrine effect, the migration of aOPCs might be influenced by the release of Ccl2 or Il1β from neighboring inflammatory cells.

Our results indicate that demyelination-activated OPCs express inflammatory mediators that promote their ability to engage in regeneration by enhancing their ability to respond to injury by increased motility and ultimately differentiation. Although further experiments with cell-specific loss of function would be needed to decipher this complex interplay between inflammatory cells and regenerative cells, our results hint at a previously unrecognized level of cross talk, which, by changing damaged CNS tissue into an environment conducive to regeneration, offers up new opportunities for enhancing remyelination in clinical situations such as those occurring in MS patients where their powers are waning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation ARSEP (R.J.M.F. and C.L.), the UK Multiple Sclerosis Society (R.J.M.F.), the French National Agency for Research, and the French Medical Research Foundation (A.L.D.). The research leading to these results has received funding from the program “Investissements d'avenir” ANR-10-IAIHU-06. We thank C. Blanc and B. Hoareau (Flow Cytometry Core CyPS, Pierre & Marie Curie University, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France) for their assistance on FACS; and D. Langui (Cellular Imaging Core, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital) for his assistance for videomicroscopy experiments; and P. Ravassard (Vectoroly Core Facility, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital). We also thank Dr. B. Nait-Oumesmar (Centre de Recherche de l'Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle Épinière, UMRS 975, Paris) for analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions and the UK Multiple Sclerosis Society Brain Bank (Professor R. Reynolds, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom) for multiple sclerosis tissue. In addition, we thank Dr. P. Soriano for the PDGFαR:GFP transgenic line.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery B, Agalliu D, Cahoy JD, Watkins TA, Dugas JC, Mulinyawe SB, Ibrahim A, Ligon KL, Rowitch DH, Barres BA. Myelin gene regulatory factor is a critical transcriptional regulator required for CNS myelination. Cell. 2009;138:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Zhao C, Franklin RJ. Increased expression of Nkx2.2 and Olig2 identifies reactive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells responding to demyelination in the adult CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, Yuk DI, Irvine KA, Kaing S, Sanai N, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1571–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Harrington EP, Yuen TJ, Silbereis JC, Zhao C, Baranzini SE, Bruce CC, Otero JJ, Huang EJ, Nusse R, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Axin2 as regulatory and therapeutic target in newborn brain injury and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/nn.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH. Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 1997;120:393–399. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant C, Raff MC. Proliferating bipotential glial progenitor cells in adult rat optic nerve. Nature. 1986;319:499–502. doi: 10.1038/319499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ. Why does remyelination fail in multiple sclerosis? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:705–714. doi: 10.1038/nrn917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Bayley SA, Milner R, ffrench-Constant C, Blakemore WF. Differentiation of the O-2A progenitor cell line CG-4 into oligodendrocytes and astrocytes following transplantation into glia-deficient areas of CNS white matter. Glia. 1995;13:39–44. doi: 10.1002/glia.440130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabinski AR, Balasingam V, Tani M, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Yong VW, Ransohoff RM. Chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed by astrocytes after mechanical injury to the brain. J Immunol. 1996;156:4363–4368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman S, Raunio M, Rossi M, Dastidar P, Elovaara I. Disease-associated inflammatory biomarker profiles in blood in different subtypes of multiple sclerosis: prospective clinical and MRI follow-up study. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;234:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton TG, Klinghoffer RA, Corrin PD, Soriano P. Evolutionary divergence of platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor signaling mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4013–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.4013-4025.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa AE, Garcia-Bueno B, Leza JC, Madrigal JL. CCL2/MCP-1 modulation of microglial activation and proliferation. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JK, Jarjour AA, Nait Oumesmar B, Kerninon C, Williams A, Krezel W, Kagechika H, Bauer J, Zhao C, Evercooren AB, Chambon P, ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ. Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal AJ, Regan-Komito D, Christou I, White GE, McNeill E, Kenyon A, Taylor L, Kapellos TS, Fisher EA, Channon KM, Greaves DR. A real time chemotaxis assay unveils unique migratory profiles amongst different primary murine macrophages. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurevics H, Largent C, Hostettler J, Sammond DW, Matsushima GK, Kleindienst A, Toews AD, Morell P. Alterations in metabolism and gene expression in brain regions during cuprizone-induced demyelination and remyelination. J Neurochem. 2002;82:126–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinghoffer RA, Hamilton TG, Hoch R, Soriano P. An allelic series at the PDGFalphaR locus indicates unequal contributions of distinct signaling pathways during development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:103–113. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenning M, Jackson S, Hay CM, Faux C, Kilpatrick TJ, Willingham M, Emery B. Myelin gene regulatory factor is required for maintenance of myelin and mature oligodendrocyte identity in the adult CNS. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12528–12542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1069-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoudaki PN, Skripuletz T, Gudi V, Moharregh-Khiabani D, Hildebrandt H, Trebst C, Stangel M. Demyelination of the hippocampus is prominent in the cuprizone model. Neurosci Lett. 2009;451:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras B, Chatzopoulou E, Heydon K, Martínez S, Ikenaka K, Prestoz L, Spassky N, Zalc B, Thomas JL. Oligodendrocyte development in the embryonic brain: the contribution of the plp lineage. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:209–220. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041963bl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM, Reynolds R. Activation and proliferation of endogenous oligodendrocyte precursor cells during ethidium bromide-induced demyelination. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:333–347. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM, Reynolds R, Fawcett JW. The oligodendrocyte precursor cell in health and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01691-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Crang AJ, Rundle JL, Blakemore WF. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the adult rat CNS express myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) Brain Pathol. 2002;12:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tai HH. Activation of thromboxane A2 receptor (TP) increases the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and recruits macrophages to promote invasion of lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Mela A, Guilfoyle EM, Goldman JE. Neonatal and adult O4(+) oligodendrocyte lineage cells display different growth factor responses and different gene expression patterns. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:3390–3402. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad DJ, Ransohoff RM. The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) Semin Immunol. 2003;15:23–32. doi: 10.1016/S1044-5323(02)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima K, Larsen CG, DuBois GC, Oppenheim JJ. Purification and characterization of a novel monocyte chemotactic and activating factor produced by a human myelomonocytic cell line. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1485–1490. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave KA, Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:535–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opalek JM, Ali NA, Lobb JM, Hunter MG, Marsh CB. Alveolar macrophages lack CCR2 expression and do not migrate to CCL2. J Inflamm (Lond) 2007;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaton G, Aigrot MS, Williams A, Moyon S, Tepavcevic V, Moutkine I, Gras J, Matho KS, Schmitt A, Soellner H, Huber AB, Ravassard P, Lubetzki C. Class 3 semaphorins influence oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment and remyelination in adult central nervous system. Brain. 2011;134:1156–1167. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Miller RH. Contact with central nervous system myelin inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Dev Biol. 1999;216:359–368. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BJ. JE/MCP-1: an early-response gene encodes a monocyte-specific cytokine. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini F, Arbour N, Blain M, Olivier A, Antel JP. Distinctive properties of human adult brain-derived myelin progenitor cells. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2167–2175. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63266-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Sandoval J, Swiss VA, Li J, Dupree J, Franklin RJ, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1024–1034. doi: 10.1038/nn.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields SA, Gilson JM, Blakemore WF, Franklin RJ. Remyelination occurs as extensively but more slowly in old rats compared to young rats following gliotoxin-induced CNS demyelination. Glia. 1999;28:77–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199910)28:1<77::AID-GLIA9>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestroff L, Bartucci S, Pasquini J, Franco P. Cuprizone-induced demyelination in the rat cerebral cortex and thyroid hormone effects on cortical remyelination. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]