Abstract

We recently revealed that the axon endoplasmic reticulum resident transcription factor Luman/CREB3 (herein called Luman) serves as a unique retrograde injury signal in regulation of the intrinsic elongating form of sensory axon regeneration. Here, evidence supports that Luman contributes to axonal regeneration through regulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and cholesterol biosynthesis in adult rat sensory neurons. One day sciatic nerve crush injury triggered a robust increase in UPR-associated mRNA and protein expression in both neuronal cell bodies and the injured axons. Knockdown of Luman expression in 1 d injury-conditioned neurons by siRNA attenuated axonal outgrowth to 48% of control injured neurons and was concomitant with reduced UPR- and cholesterol biosynthesis-associated gene expression. UPR PCR-array analysis coupled with qRT-PCR identified and confirmed that four transcripts involved in cholesterol regulation were downregulated >2-fold by the Luman siRNA treatment of the injury-conditioned neurons. Further, the Luman siRNA-attenuated outgrowth could be significantly rescued by either cholesterol supplementation or 2 ng/ml of the UPR inducer tunicamycin, an amount determined to elevate the depressed UPR gene expression to a level equivalent of that observed with crush injury. Using these approaches, outgrowth increased significantly to 74% or 69% that of injury-conditioned controls, respectively. The identification of Luman as a regulator of the injury-induced UPR and cholesterol at levels that benefit the intrinsic ability of axotomized adult rat sensory neurons to undergo axonal regeneration reveals new therapeutic targets to bolster nerve repair.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) plays a vital role in the sensing and responding to cellular perturbations through alterations in protein and cholesterol biosynthesis, with quality control being ensured through the unfolded protein response (UPR). But the UPR's role in sensory axon regeneration is largely unknown. In sensory axons, the ER generates an important retrograde injury signal through the synthesis and cleavage/activation of the ER transmembrane transcription factor, Luman/cAMP response element binding protein 3, that is retrogradely transported to the nucleus where it regulates the intrinsic of ability of these neurons to regenerate an axon. We now show that Luman does so by regulating the UPR and cholesterol biosynthesis at levels that are beneficial to axon regeneration.

Keywords: CHOP, DRG, ER stress, peripheral nerve regeneration, Srebp1, xbp1

Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury induces complex pathophysiologic changes in sensory neurons, including increased synthesis of axonal and cell body proteins and lipids that play crucial roles in nerve regeneration (Liu et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2012). These changes typically impose endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in other cell types and lead to activation of the adaptive unfolded protein response (UPR), which is aimed at increasing ER protein folding capacity and maintaining lipid homeostasis (Basseri and Austin, 2012). Although UPR activation is a negatively implicated factor in many neurodegenerative diseases and neuropathologies (Hetz and Mollereau, 2014; O'Brien et al., 2014), it also has beneficial effects (Mantuano et al., 2011; Favero et al., 2013; Ohri et al., 2013). But the role of the UPR in peripheral axon regeneration remains to be elucidated.

Three ER-resident proteins have been shown to act as UPR transducers: protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring protein-1 (IRE1), and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) (Colgan et al., 2011). Activated PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic inactivation factor 2 (eIF2α), suppressing protein translation, and is also linked to regulation of the apoptotic regulator CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP). Activated IRE1 mediates the specific splicing of X-box binding protein (xbp1) mRNA to active xbp1 (spliced xbp1), which regulates several UPR-related genes to increase protein folding capacity and degradation of misfolded proteins (Ron and Walter, 2007). ATF6 is processed to its active form by proprotein convertase site-1 and site-2 proteases (S1P and S2P; encoded by Mbtps1 and Mbtps2), the same proteases that process sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs), which regulate sterol biosynthesis (Colgan et al., 2011).

We have recently revealed that the axon ER transmembrane transcription factor, Luman/CREB3 (herein called Luman), is rapidly activated and synthesized in injured axons where it serves as a critical retrograde injury signal regulating axon regeneration linking ER stress to axon repair (Ying et al., 2014). Whether the UPR is induced in sensory neurons or regulated by Luman is unknown, but possible, given that UPR-associated genes are downstream targets of Luman in other cell types (DenBoer et al., 2005; Liang et al., 2006). Luman is implicated in the UPR through its high sequence similarity with ATF6 (Lu et al., 1997) and its ability to bind to ER stress response and UPR elements (Liang et al., 2006; DenBoer et al., 2005), the latter regulating expression of homocysteine-responsive ER-resident ubiquitin-like resident protein (Herp, which improves folding capacity and protein load balance in the ER) and ER degradation enhancing a mannosidase-like protein.

This study tested the hypothesis that Luman-associated regulation of sensory axon regeneration is linked to its regulation of the UPR following axotomy. We provide evidence that peripheral nerve injury induces the UPR and cholesterol biosynthesis in axotomized sensory neurons in a Luman-dependent manner and at a level beneficial for regenerative axonal growth.

Materials and Methods

Unless stated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and all experiments were performed at minimum in triplicate.

Animals, surgical procedure, and tissue preparation

Animal procedures were in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the University of Saskatchewan Animal Research Ethics Board. Adult male Wistar rats (225–250 g; Charles River Laboratories) were used. Aseptic unilateral 1 d midthigh sciatic nerve crush injuries were performed using a smooth-jaw hemostat (0.6 mm tip) fully closed (10 s) under 2% isoflurane anesthesia. Naive animals served as controls. Animals were given buprenorphine (0.05–0.1 mg/kg) subcutaneously preoperatively and postoperatively and killed by Euthanyl Forte (sodium pentobarbital) overdose followed by transcardial perfusion with 4% PFA or by CO2 death before tissue culture.

Adult DRG culture

Naive animals or 1 d nerve-injured rats were killed and L4–L6 DRGs removed, treated with 0.25% collagenase (1 h; 37°C) and dissociated with 2.5% trypsin (30 min; 37°C) before plating neurons on laminin- (1 μg/ml) and poly-d-lysine-coated (25 μg/ml) coverslips at 104 cells/well in 6-well plates (BD Biosciences) in DMEM with or without 10 ng/ml of NGF (Cedarlane Laboratories). Cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside (10 μm) was added to inhibit non-neuronal cell proliferation.

Treatments

siRNA.

DRG cultures were transfected at the time of plating for 48 h with one of two sets of rat Luman-specific siRNA: siRNA-1 (5′-CGACUGGGAGGUAGAGGAUUUAC-3′); or siRNA-2, a mix of two Luman-specific sequences (5′-AGCAAAUCUUACAGAAAGUGGAGGA-3′; and 5′-GAACCACAUGGCUCAAGCAGAGCAA-3′) or negative control siRNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen). Luman knockdown efficiency was assessed by Western blot and immunohistochemistry. Transfection efficiency of siRNA treatment was determined by transfecting dissociated 1 d injury conditioned or naive DRG neurons with 10 nm of a TYE 563 DS Transfection Control duplex followed by assessment of neuronal uptake 24 h later.

Cholesterol.

Cholesterol was dissolved in ethanol and used at 2 μg/ml.

Tunicamycin.

Tunicamycin was dissolved in DMSO and used at final concentrations of 0.4, 2, and 10 ng/ml.

Neurite outgrowth

Total axon length/neuron (identified by βIII-tubulin immunofluorescence) was calculated for all neurons in each of ∼50 random fields per experimental treatment group per replicate (N = 3) using NeurphologyJ (Ho et al., 2011) 48 h after plating for each experimental condition examined.

Axon isolation

The Zheng et al. (2001) approach used dissociated L4–L6 DRG neurons plated onto transwell tissue culture inserts containing a polyethylene tetraphthalate membrane with 3 μm pores (BD Biosciences) coated with poly-l-lysine and laminin. To isolate axons only, the top membrane surface was scraped with a cotton-tipped applicator (Q-tips). For cell body and proximal axon isolation, the surface underneath the membrane was scraped.

In vitro axotomy model

An adaptation of the mini-explant culture approach used by Ying et al. (2014) was implemented. L4–L6 DRGs were cut into 4 or 5 pieces and plated in a row (15–20 explants/well) on top of scratches made with a pin rake (Tyler Research) in 6-well plates coated with poly-d-lysine (25 μg/ml) and laminin (1 μg/ml) in DMEM supplemented with 10 ng/ml NGF with or without Luman siRNA treatment as above. The volume of medium was kept low for the first 24 h to help hold the explants to the culture surface via surface tension. The cultures were maintained for 7 d, with Ara-C (10 μm; to abolish cell proliferation). Fresh medium with or without Luman siRNA was added every 3 d. On day 7, the axons extending from the mini-explants were subjected to a scratch injury performed 2 mm away from the explants on either side of the row of explants. Eighteen hours later, the experiment the explants were fixed for 1 h in 4% PFA, followed by cryoprotection in 20% sucrose, removal from the dishes, and embedding as a group in cryomolds. Eight micron sections were cut on a cryostat (Microm) and processed for immunofluorescence histochemistry as below.

Neuronal counts

To assess the impact of siRNA treatment on neuronal numbers, all β-III tubulin-immunopositive neurons within 38–40 fields obtained by raster scanning in an identical manner were counted for each condition analyzed.

Cholesterol assay

Total and free cellular cholesterol mass was determined by the enzymatic fluorometric Amplex Red Cholesterol assay kit (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence cytochemistry

Dissociated L4–L6 DRG neurons fixed in 4% PFA (20 min) were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (30 min, room temperature), blocked with 2% goat serum, 2% horse serum, and 1% BSA (30 min), before incubation with mouse anti-βIII-tubulin (1:1000; Millipore), rabbit anti-Luman (1:500; V. Misra) (Lu et al., 1997), rabbit anti-GRP-78 (1:1000), rabbit-anti-SREBP (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-CHOP (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse anti-importin-β (1:200; Thermo Scientific) overnight (4°C). Immunoreactivity was visualized by either AlexaFluor-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 1 h at room temperature) or Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories;1 h at room temperature).

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

Fixed cryoprotected L4–L5 DRGs were cut at 10 μm on a cryostat (Microm). Sections were blocked 1 h at room temperature with SEA BLOCK (Thermo Scientific) incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-GRP78 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-CHOP (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit-anti-SREBP (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse anti-βIII-tubulin (1:1000; Millipore), then visualized by AlexaFluor-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 1 h at room temperature).

Analysis and quantification of immunofluorescence signal

To ensure accurate analysis of relative changes in immunofluorescence signal between experimental groups, coverslips or tissue from both experimental and control groups were processed under identical conditions and mounted on the same slide so that analysis was also performed in a systematic and equivalent fashion. Immunofluorescence data were gathered from digital images of the neuronal cultures or tissue sections captured under identical exposure conditions using Northern Eclipse version 7.0 software (EMPIX Imaging) and a Zeiss Axio Imager M.1 fluorescence microscope. Images were blinded with respect to experimental condition. Analysis was performed by tracing the outline of individual neurons using Northern Eclipse, which then calculates the average Gray and total area (in μm2) for image, yielding average Gray per μm2. For experimental conditions examined, all values obtained at that time point were normalized to the mean value of the average Gray per μm2 value for the control condition.

To quantify alterations in immunofluorescence signal for a specific marker within only the axons in a nerve section, the sections were dually processed for the axonal marker βIII-tubulin and the marker of interest. The βIII-tubulin signal was used to create a mask that defined the axonal regions (ImageJ; Rasband WS, ImageJ, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2015). The mask was then applied to the corresponding same field image of the marker being assessed, and the level of immunofluorescence signal within the mask was determined in average Grays and expressed as average Gray/μm2. Values were then normalized against the mean value of the average Gray/μm2 readings for the control condition.

Two-photon imaging

Two-photon imaging was performed using a custom-modified Olympus BX51WIF upright research microscope interfaced with an Ultima-X-Y laser-scanning module (Prairie Technologies) directly coupled to a Mai Tai XF (Spectra Physics) mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser source. Images were acquired using high numerical aperture Olympus objective lenses (LUMPLFL 40× W/IR-2 40×) and the epifluorescence detected with two top-mounted low-dark current (<10 nA) high-sensitivity (>8500 A/lumen) external PMT detectors (Hamamatsu). Emission of the relevant wavelengths was simultaneously acquired using selective emission filters (41001, 41002 Olympus BX2 mounted). Z-stack images above and below the membrane (1.5 μm step, 10.5 μm total depth) were acquired with an X-Y spatial resolution of 0.29 μm/pixel and were compressed into single, 2D maximum intensity projections.

Western blot analysis

L4–L6 DRGs were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor mixture. Lysates were centrifuged (10 min, 14,000 × g), supernatants collected, and protein concentration determined (Bradford assay). A total of 20 μg protein was electrophoresed on 12% SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), blocked (LI-COR Biosciences; 1 h at room temperature), and incubated overnight (4°C) with rabbit anti-GRP78 (1:1000), rabbit anti-protein disulfide isomerase (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-PERK (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phosphorylated PERK (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-CHOP (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-IRE1α (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phosphorylated IRE1α (1:1000: Abcam), rabbit anti-Calnexin (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-SREBP1 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-Luman (1:1000; V. Misra) (Lu et al., 1997). Membranes were then incubated with IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse secondary antibody or IRDye 680LT goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000; LI-COR Biosciences; 1 h at room temperature). Proteins were visualized with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Goat anti-Lamin B (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or mouse anti-GAPDH (1:2000; Novus Biologicals) served as loading controls.

qRT-PCR array

UPR qRT-PCR arrays (SA Biosciences) containing primers for 84 gene transcripts involved in the UPR were used as per the manufacturer's instruction to compare mRNA purified from dissociated 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons transfected with Luman-specific siRNA or nontargeting control siRNA for 2 d in vitro. The results were analyzed (including 5 housekeeping genes) using an SA Biosciences online resource RT2 profiler.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted (RNeasy Kit, QIAGEN) and converted to cDNA (QuantiTect Rev Transcription Kit, QIAGEN). qRT-PCR primers are as follows: Spliced xbp1, 5′-TCTGCTGAGTCCGCAGCAGG and 5′-TAAGGAACTGGGTCCTTCT; xbp1, 5′-TCAGACTACGTGCACCTCTGC and 5′-TAAGGAACTGGGTCCTTCT; Chop, 5′-TGGAAGCCTGGTATGAGGAC and 5′-TGCCACTTTCCTCTCGTTCT; GRP78, 5′-GGCTTGGATAAGAGGGAAGG and 5′-GGTAGAACGGAACAGGTCCA; Luman, 5′-TGTGCCCGCTGAGTATGTTG and 5′-AGAAGGTCGGAGCCTGAGAA; Insig1, 5′-ACAGTGGGAAACATAGGAC and 5′-TGAACGCATCTTTAGGAG; Insig2, 5′-AGCAACCGTTGTCACCCA and 5′-TCCCATCGTTATGCCTCC; Srebf1, 5′-CGCTACCGTTCCTCTATCA and 5′-CTCCTCCACTGCCACAAG; Mbtps2, 5′-GTCCCGTTACTAATGTGC and 5′-CAAACTTGAGTGGCTTCA; Canx, 5′-TTTGGGTGGTCTACATTC and 5′-CTTCTTCGTCCTTCACAT; Ubxn4, 5′-GGAACGGTGCTTTATCCA and 5′-ATCTTGAGTCCGCAGTCG; GAPDH, 5′-GGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTGGAGTC and 5′-GTGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC; and 18S rRNA, 5′-TCCTTTGGTCGCTCGCTCCT and 5′-TGCTGCCTTCCTTGGATGTG.

All qRT-PCRs satisfied MIQE guidelines. GAPDH and 18S rRNA served as normalizers. In qRT-PCR array, five housekeeping genes were analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Differences between means were assessed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's analysis Prism (GraphPad Software). All values are expressed as mean ± SEM with differences considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

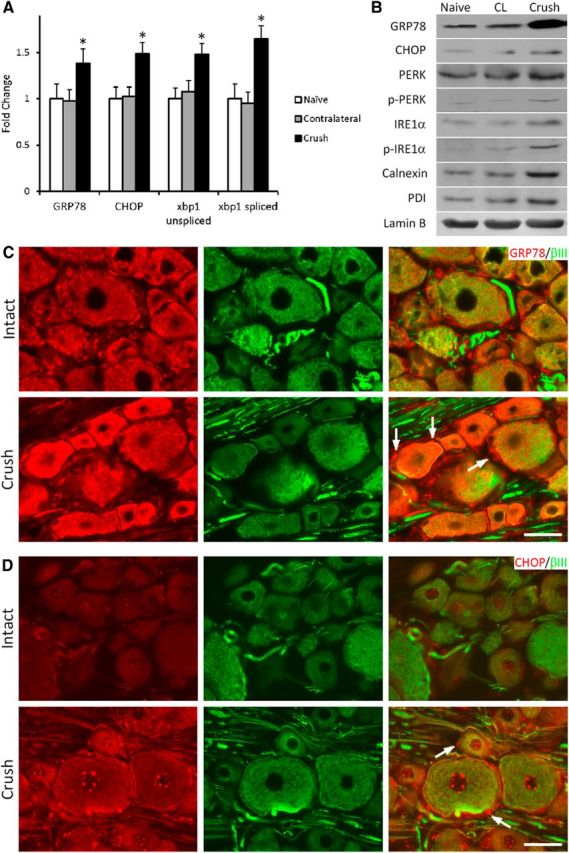

Sciatic nerve crush injury triggers the UPR in DRGs and axons

To determine whether axotomy induces the UPR in sensory neurons, UPR-related gene expression was examined in 1 d sciatic nerve crush injured DRG. qRT-PCR analysis revealed increased UPR transcript expression, including the chaperone protein, glucose-related protein 78 (GRP78), the apoptosis regulator CHOP, xbp1, and the splice product of xbp1 in axotomized DRGs (Fig. 1A). These results were confirmed by Western blot analysis that also examined additional UPR protein markers that all increased in response to injury. These included PERK and IRE1 (transducers of UPR) and their activated phosphorylated forms, Calnexin (chaperone protein), and protein disulfide isomerase (catalyzes disulfide formation and protein folding) (Fig. 1B) (Hetz and Mollereau, 2014). Immunofluorescence revealed a dramatic increase in cytoplasmic GRP78 and CHOP expression in injured DRG neurons (identified by their coexpression of neuronal specific β-III tubulin) and perineuronal cells, with increased nuclear localization of the transcription factor CHOP also observed in the injured neurons (Fig. 1C,D).

Figure 1.

Nerve injury elevates UPR expression in DRG neurons. A, mRNA levels as determined using qRT-PCR of UPR-related genes relative to naive controls in DRGs ipsilateral or contralateral to 1 d sciatic nerve crush as indicated (4 runs, 2 animals/group/run). B, Representative immunoblot of DRG UPR-related proteins in samples from naive, 1 d crush injury, or contralateral to crush (CL) as indicated. p-PERK and p-IRE1α detect the phosphorylated/activated forms of the proteins. Lamin B, loading control (N = 3 separate experiments). (C) GRP78 and (D) CHOP immunofluorescence (IF) colabeled with the neuronal marker βIII tubulin in DRG sections as indicated (Intact or 1 d crush). Arrows indicate representative perineuronal satellite cells immunopositive for each marker in injured DRG. Note the elevated expression in both neuronal and perineuronal cells following nerve injury. Scale bar, 50 μm. N = 4 animals analyzed per experimental condition. *p < 0.01.

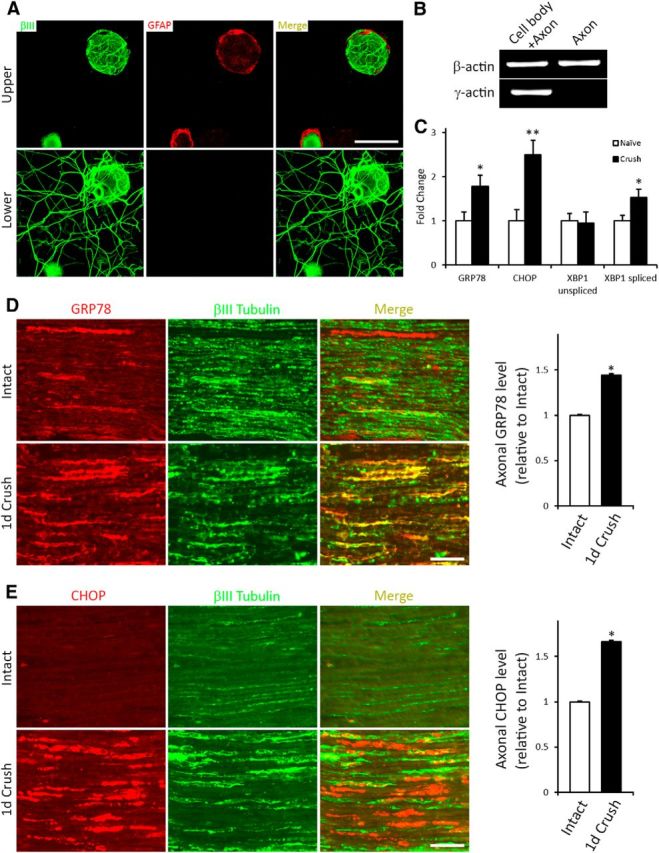

Axons have been shown to contain an ER equivalent (Merianda and Twiss, 2013) and express and locally synthesize several ER resident proteins, including GRP78 and calreticulin (Willis et al., 2005). To assess whether there is an axonal UPR, dissociated DRG neurons from naive or 1 d prior injury-conditioned animals were cultured on membrane inserts, thereafter extending axons/neurites through the 3 μm membrane pores (that neither Schwann cells nor satellite glial cells appeared able to migrate through; Fig. 2A) and growing along the lower membrane surface. Pure axonal samples were obtained by scraping away cell components from the top surface of the insert membrane. RNA extract purity from lower membrane “axon only” preparations as opposed to upper membrane “cell bodies and proximal axons” was ascertained by the absence of cell body-restricted γ-actin mRNA and the presence of β-actin mRNA in both cell bodies and axons (Fig. 2B) and the absence of the nuclear envelope protein LaminB, as previously described (Ying et al., 2014). qRT-PCR analysis on pure axonal mRNAs revealed increased levels of GRP78, CHOP, and spliced xbp1 in injury-conditioned neurons (Fig. 2C), supporting that nerve injury triggers the UPR in both axotomized DRGs and axons. To verify that this also occurred in vivo, axonal GRP78 and CHOP protein expression was analyzed in tissue sections of intact or injured nerve proximal to a 1 d crush injury site using the βIII-tubulin immunofluorescence signal to create a mask to define the axonal regions and allow quantification of the UPR marker within. Both GRP78 and CHOP showed significant injury-associated increases in the injured axons (Fig. 2D,E), with CHOP also highly expressed in extra-axonal cells.

Figure 2.

The UPR is elevated in injured axons. A, Neuronal DRG cultures grown on insert membranes and processed to detect the neuron/axon marker βIII tubulin (green) and the Schwann cell/satellite glial cell marker GFAP (red) immunofluorescence as indicated, with focal plane of images taken being either above (top) or below (bottom) the membrane. The presence of βIII tubulin and the absence of GFAP signal in the lower membrane indicate that only axons extend through the pores to grow on the underside of the membrane. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, qRT-PCR of RNA from “axon only” or “cell body + proximal axon” preparations. The absence of γ-actin confirms purity of “axon only” extract. C, qRT-PCR analysis of axonal mRNA levels of UPR-related genes relative to naive controls from 1 d crush injury-conditioned DRG neurons assayed 48 h in vitro on transwell inserts (N = 4 experimental replicates). *p < 0.01. **p < 0.01. Representative sections of sciatic nerve immediately proximal to the crush injury site or from intact control sciatic nerve processed to detect expression of the UPR proteins GRP78 (D) or CHOP (E) and colocalized with the axonal marker β-III tubulin. Histograms (right) summarize alterations in expression of the markers in the 1 d injured axons (1 d Crush) relative to Intact control. Scale bar, 100 μm. *p < 0.01. N = 3 animals and 37–44 fields analyzed/condition. The expression of both UPR-associated proteins is significantly elevated in the 1 d injured axons, with increased extra axonal expression also evident for CHOP.

Because increased levels of the transcription factor CHOP were observed in the nuclei of injured sensory neurons (Fig. 1D) and the role GRP78 plays in protein transport out of the ER (for review, see Naidoo, 2009), we posited that axonal injury may induce a retrograde transport of these UPR proteins from the injured axon back to the cell body, similar to that which we recently described for axonal ER-resident transcription factor Luman (Ying et al., 2014). To examine this, the sciatic nerve was crushed and then 24 h later ligated proximal to the injury site for another 24 h before processing for CHOP or GRP78 immunofluorescence. The intense CHOP or GRP78 signal observed in the injury-conditioned nerve, especially that distal to ligation versus ligation alone, is consistent with the retrograde transport of CHOP and GRP78 from the initial crush site toward the cell body (Fig. 3A,B). There was also an accumulation of GRP78 on the proximal side of the ligation in the injury-conditioned nerve relative to ligation alone, supporting that this chaperone protein is also anterogradely transported in response to injury. Colocalization of these immunofluorescence signals with βIII tubulin confirmed their localization to the injured axons. Collectively, events, such as altered UPR transcript and protein expression, the accumulation of CHOP in the nucleus, evidence of its and GRP78's retrograde transport, and the presence of increased levels of spliced xbp-1, support that injury triggers the UPR response in both DRG and axons.

Figure 3.

UPR protein transport in injured axons. Representative sciatic nerve sections processed for (A) GRP or (B) CHOP immunofluorescence from animals that had undergone 24 h sciatic nerve ligation (left panels) or sciatic nerve crush, followed by ligation proximal to the injury site 24 h later, for an extra 24 h as indicated. DRG with arrow indicates retrograde direction, whereas Crush with arrow indicates direction toward prior crush site. Endogenous GRP78 and CHOP signal is increased and accumulates distal to ligation in the crush+ligation nerve (boxes) versus ligation only. Box insets highlight the high degree of colocalization between the UPR marker (red) in and the axonal marker β-III tubulin (green). The increased levels of GRP78 and CHOP in the Crush+ligation nerve in area immediately distal to the ligation are consistent with increased synthesis of the UPR markers in the injury-conditioned nerve and retrograde transport from the initial injury site. Note the accumulation of GRP78 proximal to ligation in the Crush+Ligation nerve suggestive of anterograde transport as well in response to the prior injury. Scale bar, 50 μm. N = 3 animals/condition analyzed.

Luman siRNA effectively decreases Luman expression

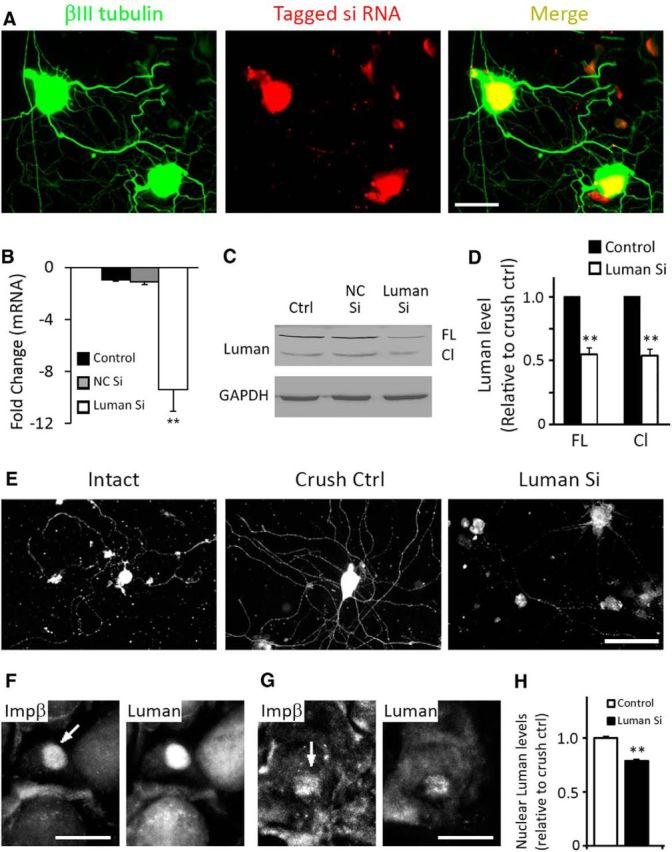

Luman is a UPR-associated transcription factor (DenBoer et al., 2005; Liang et al., 2006) that is activated in sensory neurons by axotomy (Ying et al., 2014). To study the role of Luman in regulating the nerve injury-triggered UPR, we first had to assess whether treatment of the neuronal cultures with Luman-selective siRNAs could effectively knock down Luman expression at the mRNA, protein, and functional levels. The ability of the siRNAs to effectively transfect neuronal cultures was examined by exposing the cultures in an identical manner to a fluorescently nontargeting siRNA. This revealed that virtually all neurons examined took up the labeled siRNA (Fig. 4A) (Ying et al., 2014). Next, we exposed half of the intact or 1 d injury-conditioned dissociated neurons to Luman-selective siRNA for 48 h before processing all cultures for Luman and βIII-tubulin expression by immunofluorescence or qRT-PCR to assess impact on Luman mRNA levels and neuron viability. Cell counts of 3 experimental repeats revealed that virtually neurons survived the Luman siRNA treatment with 103 ± 5.51% (SEM) or 102 ± 9.58% (SEM) of the intact or injury conditioned neurons, respectively, surviving relative to the control cultures. qRT-PCR demonstrated an efficient Luman mRNA knockdown in the 1 d injury-conditioned neurons in response to the Luman-specific siRNA treatment (Luman Si) versus medium alone (Control) or nontargeting control siRNA (NC Si; Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis of Luman protein levels in neurons cultured under these conditions showed that Luman siRNA knocked down expression of both full-length and cleaved/activated forms of Luman protein by equivalent amounts (Fig. 4C,D). We also observed decreased Luman immunofluorescence signal in the Luman siRNA-treated cultures apparent in both the cell body and axonal compartments (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Luman siRNA treatment effectively reduces Luman expression. A, Fluorescence photomicrographs showing βIII tubulin-positive 1 d injury-conditioned cultured neurons (green) are successfully transfected with fluorescently tagged siRNA 24 h after treatment. B, qRT-PCR reveals efficient Luman mRNA knockdown in 1 d injury-conditioned neurons cultured 48 h with Luman-specific siRNA (Luman Si) versus medium alone (Ctrl, Control) or nontargeting control siRNA (NC Si). C, Representative Western blot analysis of Luman protein levels in neurons cultured under conditions as in B shows effective knockdown of both full-length (FL) and cleaved /activated (Cl) forms of Luman protein (N = 3 experimental replicates; GAPDH loading control). D, Quantification of three experimental replicates as in C reveals that the full-length and cleaved/activated forms of Luman are downregulated in an equivalent manner by Luman siRNA. E, Representative Luman immunofluorescence (IF)-positive neurons from Intact, 1 d injury-conditioned Control, or 1 d injury-conditioned Luman siRNA-treated cultures as in B reveal an injury-associated increase in axonal and neuronal Luman IF relative to Intact and a marked reduction in axon outgrowth and Luman IF in the Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned neurons. Scale bar, 100 μm. F, G, Representative neurons from sections of mini-DRG explants grown for 7 d with (G) or without (F) Luman siRNA treatment before axotomizing the neurites for 18 h and examining Luman and importin-β (Ιmpβ) immunofluorescence in the neuronal nuclei. Note the robust nuclear localization of importin-β (arrow) in the axotomized neurons in both experimental groups, but with visibly reduced nuclear Luman levels in the siRNA-treated injury conditioned neurons (G). Scale bar, 25 μm. H, Quantification of Luman IF levels in importin-β-positive nuclei in control versus Luman siRNA-treated neurons reveals a significant reduction in levels of Luman immunofluorescence signal in the nucleus (N = 97–98 importin-β-positive neuronal nuclei assessed/condition). **p < 0.001.

Finally, we also examined whether the reduced Luman expression in the siRNA-treated cultures also resulted in decreased levels of Luman reaching the nucleus following axotomy. To do this, we seeded naive L4–L6 mini-DRG explants onto culture dishes where a pin rake was used to create scratches on the surface along which neurons within the explants extended their axons for 7 d in the presence or absence of Luman siRNA as per Ying et al. (2014). At 7 d in vitro, the axons on either side of the row of explants were transected using a pin at a distance of 2 mm from the explants. The experiments were stopped 18 h later and the explants dually processed for importin-β and Luman immunofluorescence. This in vitro axotomy model resulted in localization of importin-β to many of the nuclei of both the axotomy control and axotomy+Luman siRNA groups. However, the levels of Luman observed in the neuronal cell bodies and the nuclei of those neurons with intense importin-β were markedly different between the two groups with the neurons in the Luman siRNA-treated cultures displaying significantly lower levels of Luman in the nuclei relative to the axotomy control neurons (Fig. 4F–H).

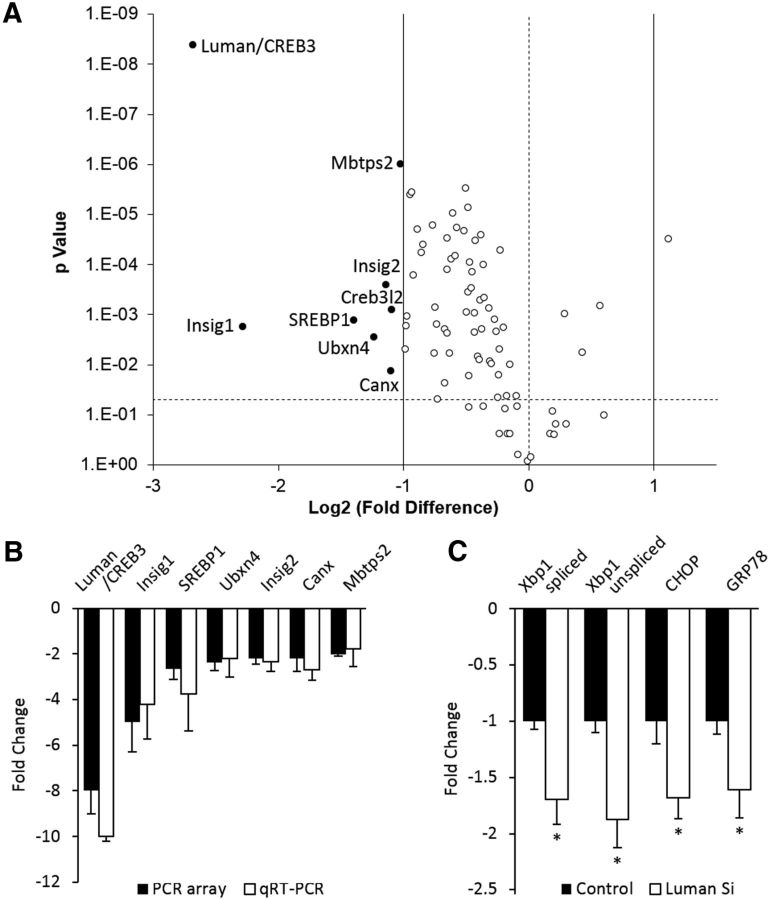

Knockdown of Luman decreases the injury-induced UPR

qRT-PCR arrays that assess UPR-associated gene expression were used to determine whether knockdown of endogenous Luman alters UPR-associated gene expression. RNA purified from 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons cultured and transfected 48 h in vitro with Luman-specific siRNA or nontargetting control siRNA revealed that many UPR-related genes are downregulated in Luman knockdown neurons (Fig. 5A). The mRNAs downregulated >2-fold included insulin-induced gene 1 (Insig1), Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 (Srebf1), UBX domain-containing protein 4 (Ubxn4), insulin-induced gene 2 Insig2, Calnexin (Canx), and Membrane-bound transcription factor site-2 protease (Mbtp2). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed these array results with no significant differences noted between microarray and qRT-PCR data. We also confirmed a significant downregulation of previously examined GRP78, CHOP, xbp1, and spliced xbp1 (Fig. 5B,C). Notably, the UPR response in the 1 d Crush only experiments (Fig. 5A) did not differ significantly from those values obtained in the 1 d Crush +NC siRNA experiments in Figure 5C (data not shown), supporting that the siRNA did not invoke a generalized ER stress response. Interestingly, among the 8 genes downregulated >2-fold, Insig1, Insig2, Srebf1, and Mbtps2 are involved in the regulation of cholesterol synthesis (Colgan et al., 2011).

Figure 5.

Knockdown of Luman expression decreases the injury-induced UPR. A, Volcano plot derived from qRT-PCR array data monitors UPR-associated transcripts with log2 fold change for injury-conditioned DRG neurons transfected with Luman-specific versus control-scrambled siRNA (x-axis) as a function of p value (y-axis) (horizontal dashed line, p = 0.05). Transcripts downregulated >2-fold are shown as solid spots with gene designations (p < 0.05). B, qRT-PCR array data were verified by qRT-PCR for mRNAs identified in A (N = 4 animals/condition as in A; N = 4 experimental replicates). C, qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels in 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons cultured 48 h in nontargeting control siRNA (Control) or Luman-specific siRNA (Luman Si) for markers assessed in Figure 1 as indicated (N = 3 experimental replicates). *p < 0.01.

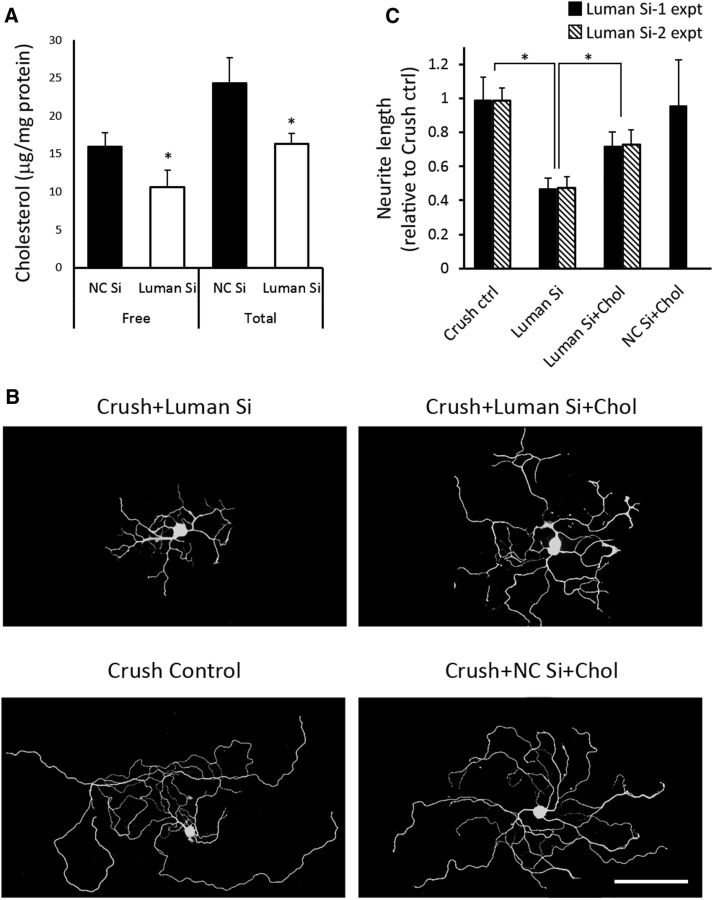

Supplemental cholesterol rescues axon outgrowth in Luman knockdown neurons in vitro

Because cholesterol is an essential cell membrane component and Luman knockdown impairs axon outgrowth in injury-conditioned neurons (Ying et al., 2014), we speculated that Luman siRNA-treated neurons might not make enough cholesterol to support intrinsic regenerative axon growth. Of note, Luman knockdown significantly reduced free and total cholesterol levels in injury-conditioned sensory neurons by 34 ± 7% and 33 ± 5%, respectively (Fig. 6A), with a similar impact on SREBP1 expression at the transcript and protein levels (see Figs. 5, 8). To investigate whether the decreased cholesterol levels were causally linked to the shortened axon outgrowth (Fig. 6B), Luman knockdown neurons from injury-conditioned DRGs were analyzed in vitro with or without cholesterol supplementation as per Fünfschilling et al. (2012).

Figure 6.

Cholesterol dependency of sensory axon outgrowth. A, Cholesterol levels in 1 d injury-conditioned neurons transfected 48 h in vitro with nontargeting control (NC) or Luman-specific siRNA. N = 4 experimental replicates. B, Representative 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons assayed 48 h in medium alone (Crush Control), NC siRNA + 2 μg/ml cholesterol (NC Si + Chol), Luman Si, or Luman Si + 2 μg/ml cholesterol (Luman Si + Chol) followed by β-III tubulin immunofluorescence axon detection (N = 3 experimental replicates). Scale bar, 200 μm. C, Quantification of total axon length in B (N = 150 neurons/condition/Luman siRNA; N = 3 experimental replicates/Luman siRNA). Knockdown of Luman decreased total and free cholesterol levels and axon outgrowth that could be partially rescued by supplemented cholesterol. *p < 0.01. Virtually identical results were observed with either Luman siRNA-1 (Si-1 expt) or Luman siRNA-2 (Si-2 expt).

Figure 8.

Impact of tunicamycin or cholesterol supplementation on SREBP1, cholesterol, and CHOP expression. A, Representative neurons from 48 h cultures of 1 d injury preconditioned neurons processed for immunofluorescence (IF) to detect the cholesterol biosynthesis regulator SREBP1 reveal reduced neuronal and axonal expression in response to Luman siRNA treatment (Crush+Luman Si) relative to Crush Control that can be rescued with 2 ng/ml tunicamycin treatment (N = 3 experimental replicates). Scale bar, 70 μm. B, Quantification of SREBP1 IF signal intensity in DRG neurons cultured as in A reveals a significant decrease in SREBP1 expression in response to Luman siRNA treatment (Luman Si) relative to Crush Control (Crush ctrl) that is reversed with 2 ng/ml tunicamycin treatment (Luman Si+Tu) (N = 130–160 neurons analyzed/experimental condition from 3 experimental replicates). ***p < 0.001. C, Total cholesterol levels in 1 d injury-conditioned control neurons or 1 d injury-conditioned neurons transfected 48 h in vitro with Luman-specific siRNA (Luman Si) or Luman-specific siRNA+ 2 ng/ml tunicamycin. Note the similar pattern of regulation as was observed for SREBP1 in B. N = 3 experimental replicates. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. D, Representative Western blot showing impact of cholesterol. supplementation on SREBP1 expression in 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons assayed 48 h in medium alone (Crush Control), NC siRNA + 2 μg/ml cholesterol (NC Si + Chol), Luman Si, or Luman Si + 2 μg/ml cholesterol (Luman Si + Chol). E, Quantification of neurons treated as in D reveals decreased SREBP1 protein expression with Luman siRNA treatment that is further reduced to nearly undetectable levels with cholesterol supplementation (Luman Si+Chol) (N = 128–158 neurons analyzed/experimental condition from 3 or 4 experimental replicates). **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. F, Representative neurons from experimental conditions as in D and processed for IF to detect CHOP expression in neurons identified with β-III tubulin IF. Axon growth is impaired and cytoplasmic and axoplasmic CHOP expression reduced relative to Crush control in response to Luman siRNA treatment, with both being increased by cholesterol supplementation. Scale bar, 100 μm. G, Quantification of neurons treated as in F reveals decreased CHOP protein expression with Luman siRNA treatment relative to crush control that is significantly rescued with cholesterol supplementation (Luman Si+Chol) (N = 86–99 neurons analyzed/experimental condition from 3 or 4 experimental replicates). **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Luman knockdown resulted in neurons forming axons that were 48 ± 6% shorter than injury-conditioned controls. Cholesterol supplementation, given concomitantly with Luman siRNA, significantly rescued axon outgrowth in these neurons to 74 ± 9% that of control neurons (Fig. 6B,C), with no discernible impact on control nontargeting siRNA-treated injury-conditioned neuron outgrowth, suggesting that 1 d axotomized control DRG neurons produce the cholesterol required for this form of intrinsic regenerative axon growth or that maximal outgrowth is set by other factors (Fig. 6B,C). Notably, the results of these cholesterol supplementation experiments were virtually identical when repeated with a different set of Luman-selective siRNAs (Fig. 6C; Luman Si-2 expt).

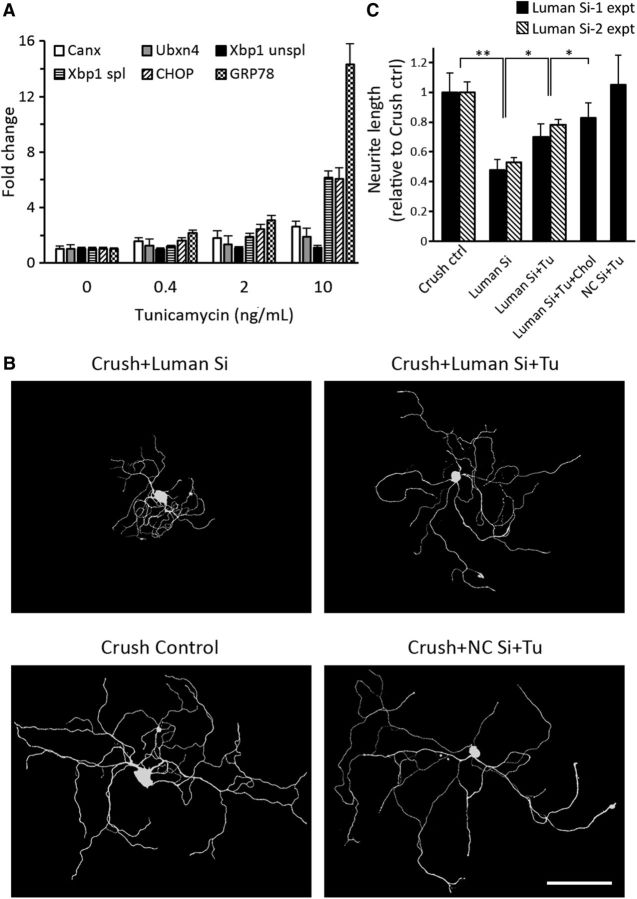

Rescue of axon outgrowth in Luman knockdown neurons by a UPR inducer

Our finding that cholesterol supplementation did not fully rescue the axon outgrowth (Fig. 6) prompted us to investigate whether other UPR-related genes downregulated by Luman siRNA (Fig. 5) contribute to regenerative axon outgrowth, but in a cholesterol-independent manner. Thus, tunicamycin, a UPR inducer that activates the UPR through pathways not involving Luman (Liang et al., 2006), was used. Luman knockdown decreased mRNA expression of the UPR markers Canx, Ubxn4, GRP78, CHOP, xbp1, and spliced xbp1 levels by 1.6 ± 0.25-fold to 4.2 ± 1.5-fold (Fig. 2). To increase expression of these UPR genes back to their normal 1 d injury-associated levels, varying low concentrations of tunicamycin were tested. Figure 7A reveals that 2 ng/ml tunicamycin increased the aforementioned UPR-associated gene expression by 1.4 ± 0.5-fold to 3.1 ± 0.4-fold, rendering expression close to levels observed in control injured neuron. Further, 2 ng/ml tunicamycin did not discernibly alter the Luman siRNA-induced reductions in Luman in cultured naive neurons (data not shown).

Figure 7.

UPR-inducer tunicamycin rescues axon outgrowth in Luman knockdown neurons. A, UPR-associated gene mRNA levels in 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons cultured 48 h in Luman-specific siRNA + tunicamycin at indicated concentrations and normalized to 0 ng/ml tunicamycin values (N = 3 experimental replicates). B, Representative 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons assayed 48 h in medium alone (Crush Control), nontargeting control siRNA + 2 ng/ml tunicamycin (NC Si + Tu), Luman-specific siRNA (Luman Si), or Luman-specific siRNA + 2 ng/ml tunicamycin (Luman Si + Tu), followed by β-III tubulin immunofluorescence axon detection (performed in triplicate). Scale bar, 200 μm. C, Quantification of total axon length in B and 1 d injury-conditioned DRG neurons assayed 48 h in Luman Si + tunicamycin and cholesterol (Luman Si + Tu + Chol) (N = 150 neurons/experimental condition; 3 replicates/Luman siRNA set). *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. Knockdown of Luman decreased total axon outgrowth that could be partially rescued by the UPR inducer tunicamycin, with equivalent results observed with either Luman siRNA treatment (Si-1 expt vs Si-2 expt).

We next analyzed axon outgrowth in Luman knockdown 1 d injury conditioned neurons assayed in vitro 48 h ± 2 ng/ml tunicamycin added concomitantly with the Luman siRNA. Although tunicamycin treatment had no apparent impact on nontargetting control siRNA-transfected neurons, it significantly rescued axon outgrowth in Luman knockdown neurons to 69 ± 9% that observed in control injury-conditioned only neurons (Fig. 7B,C).

When cholesterol and tunicamycin were applied together, the axons grew significantly longer than that when used individually, reaching 83 ± 10% that of control injury-conditioned neurons. It should be noted that the effects of combined cholesterol and tunicamycin treatment were neither completely additive, nor did they reach at least 100% of the growth observed in injury-conditioned control neurons, supporting that the regulation of these two pathways is likely intertwined and does not occur one in isolation of the other.

To assess whether the tunicamycin-induced axon growth in Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned neurons might also be associated with elevated expression of SREBP1, a key transcription factor driving cholesterol biosynthesis (for review, see Fernández-Hernando and Moore, 2011), neuronal SREBP1 expression was examined and compared with Luman siRNA-treated or crush injury control neurons. Qualitative and quantitative analysis revealed that the rescue of axon outgrowth with 2 ng/ml tunicamycin in the Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned neurons was associated with increased SREBP1 expression in both the cell bodies and axons of these injury-conditioned neurons (Fig. 8A,B). These changes were paralleled by increases in total cholesterol levels as measured by assay (Fig. 8C) or as assessed using the cholesterol binding stain filipin (data not shown). However, this latter form of cholesterol assessment is extremely susceptible to fading and thus could not be reliably used for quantitative analysis (Rudolf and Curcio, 2009).

The increased SREBP1 expression effected by tunicamycin was in sharp contrast to its regulation by cholesterol supplementation in the Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned neurons. In these experiments, SREBP1 expression was reduced even further relative to Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned control neurons, suggesting that, when exogenous cholesterol is high enough to meet the growth demands, a negative feedback loop is induced with respect to the endogenous cholesterol biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 8D,E). Finally, we also examined whether the increased axon growth effected by cholesterol supplementation of the Luman siRNA-treated, injury-conditioned neurons has an impact on UPR expression relative to the Luman siRNA-treated only controls by assessing alterations in CHOP expression in these experiments. Qualitatively, we found CHOP expression to be elevated in both the cell bodies and axon compartments of Luman siRNA+cholesterol-supplemented neurons relative to the Luman siRNA injury-conditioned control neurons, with quantification of the immunofluorescence signal over the neuronal cell body revealing that these changes in expression are significant (Fig. 8F,G).

Discussion

The UPR strives to reestablish proteostasis while meeting the demand for increased protein production and/or proper protein folding under times of ER stress. Here, we provide the first evidence supporting that the UPR, including cholesterol biosynthesis, is extensively activated in DRG neurons and axons in response to axotomy, that it is regulated by Luman, and that the UPR is involved in the intrinsic ability of injured sensory neurons to undergo robust axon regenerative growth.

Peripheral axotomy induces the UPR in DRG neurons and axons

The UPR is implicated in many neurodegenerative disorders (Hetz and Mollereau, 2014; O'Brien et al., 2014). The deleterious impact of the UPR on neuronal pathological states is generally the focus of ER stress/UPR research, with strategies to dampen this response by deletion of CHOP or delivery of UPR antagonists proving neuroprotective (Hu et al., 2012). But the converse is also true, with the UPR actively promoting Schwann or retinal ganglion cell survival after injury (Mendes et al., 2009; Mantuano et al., 2011), supporting that, when induced to only moderate levels, it can be neuroprotective.

Molecular stimuli can alter the functional state of axonal proteins implicated in the UPR. For example, axonal application of BDNF causes xbp1 splicing (Hayashi et al., 2007), whereas lysophosphatidic acid treatment increases eIF2 phosphorylation and calreticulin translation (Vuppalanchi et al., 2012), supporting that at least some components of the UPR are activated, post-translationally modified, and translated in axons. Given the critical roles that increased axonal and neuronal protein synthesis play in axon regeneration (Jung et al., 2012), it is predicted that the UPR would be activated to regulate these processes. Our data support extensive UPR activation following injury, with all UPR markers examined increasing in both neurons and axons (Figs. 1, 2, 3). The exact nature of the signal initiating this response is currently unknown but likely involves ER stress events, such as calcium release from ER stores or a response to axotomy-induced axoplasmic calcium fluxes (Yudin et al., 2008; Vuppalanchi et al., 2012). Luman can also be activated by ER stress (Liang et al., 2006).

Luman links the UPR to the regenerative growth of sensory neurons

Luman overexpression protects cells against ER stress-induced apoptosis (Liang et al., 2006); and in axotomized neurons, endogenous Luman favorably regulates regenerative axon growth (Ying et al., 2014). We now demonstrate that Luman's role in UPR regulation is an important link to the intrinsic regenerative axonal growth capacity of sensory neurons.

Luman transcript and protein expression were effectively downregulated by either of two siRNA treatments (Figs. 4, 6, 8). It is possible that only a small portion of the transcripts are available for translation, as most axonal transcripts are held in a translationally repressed state by the zip code protein directing it to its subcellular location until synthesis is triggered by a cellular event, such as axotomy (Donnelly et al., 2011).

Luman knockdown in injury-conditioned neurons decreased the UPR (Fig. 5), while also partially blocking axon growth, the latter consistent with our previous study (Figs. 4, 6, 8) (Ying et al., 2014). Luman knockdown was associated with lower levels of Luman in the injury-conditioned neuronal nuclei (Fig. 4H), likely functionally linked to the observed reduced UPR. It is unlikely that the treatment affected the ability of axonal injury signals to be retrogradely transported as intense nuclear staining for importin-β, a protein synthesized intra-axonally at the site of injury involved in transporting cargo proteins from the site of injury to the cell body (Hanz et al., 2003), was observed. It is not known whether the regulation of the UPR or SREBP1 levels by Luman is a consequence of direct transcriptional regulation but is possible whether these genes have UPR or ER stress elements in their promoters (Liang et al., 2006).

Before our study, little was known about the involvement of the UPR or components of the UPR in axon growth. Recently, the UPR marker GRP78 was linked to axon growth and fasciculation in development of thalamocortical connections (Favero et al., 2013). Our study supports that an increased UPR appears causally related to the intrinsic ability of sensory neurons to regenerate axons. In Luman knockdown injury-conditioned neurons, we found low-dose tunicamycin, a UPR inducer that does not involve Luman (Liang et al., 2006), brought levels of downregulated UPR markers back to those observed in injury-conditioned controls and also significantly rescued axon outgrowth in the Luman knockdown neurons (Fig. 7). This supports that a low level of UPR is beneficial for axon outgrowth. It is said that both the severity and duration of the stimulus effecting a UPR in cells determine how harmful the outcomes will be. The concept that hormetic doses of cellular stressors are beneficial to the repair state is not novel (Calabrese et al., 2010; Fouillet et al., 2012), but the demonstration that only 2 ng/ml of tunicamycin (500× less than that used by Fouillet et al., 2012) benefits regenerative axonal growth in injury-conditioned sensory neurons is. Not surprisingly, we found that 48 h exposure to 50–100 ng/ml tunicamycin left the injury-conditioned neurons in a growth incapacitated and compromised state (data not shown). Also notable is the lack of discernible impact 2 ng/ml tunicamycin had on the axonal growth capacity of naive neurons (data not shown), supporting that additional injury-associated factors must contribute to regenerative axon growth regulated by the UPR.

Cholesterol is an essential component in membrane structure and signal transduction, with the regulation of cholesterol and the UPR being linked (Colgan et al., 2011) through UPR activation of SREBPs (Kammoun et al., 2009), transcription factors regulating sterol biosynthesis. The activation of SREBPs (also known as SREBFs), ATF6, and Luman all requires proteolysis by S1P and S2P (encoded by Mbtps1 and Mbtps2, respectively) (Ye et al., 2000; Raggo et al., 2002). Neuronal Luman knockdown significantly decreased the expression of genes coding for SREBP1 and Mtbtps2/S2P (Figs. 2, 8) and decreased cellular cholesterol levels (Figs. 6, 8). In the CNS, defective cholesterol biosynthesis in mature neurons can be compensated for by astrocytic cholesterol transfer (Fünfschilling et al., 2012). A similar situation may exist for sensory neurons, whereby supplemental cholesterol compensates for the reduced cholesterol in axotomized Luman knockdown neurons (Fig. 6), thereby rescuing axon growth. Interestingly, exogenous cholesterol appears to invoke a negative feedback loop with respect to SREBP1 regulation, as even lower levels of SREBP1 expression in the Luman siRNA+cholesterol treated injury-conditioned neurons were observed. This is consistent with lipid repletion models where the proteolytic cleavage/activation of SREBPs is inhibited (Ye and Debose-Boyd, 2011). It may be also be an attempt by the neurons to mitigate an excessive UPR response potentially induced by the cholesterol, a neuroprotective strategy when the UPR is high (Cunha et al., 2008; Taghibiglou et al., 2011; Volmer et al., 2013). Indeed, the elevated levels of CHOP observed in Luman knockdown neurons in response to cholesterol supplementation supports that a general UPR may be induced by this treatment (Fig. 8F,G) but, at the level observed, still appears to be beneficial for axon growth.

However, because cholesterol supplementation did not increase the growth in control siRNA-transfected neurons, this suggests that additional factors beyond cholesterol limit the extent of this regenerative growth or that perhaps endogenous either axotomized DRG neurons are normally able to endogenously synthesize enough cholesterol to fully support regenerative axon growth programs under the conditions examined.

UPR proteins as potential retrograde injury signals

We have shown that, shortly following axonal injury, the cleavage/activation and release of Luman from the axonal ER equivalent proximal to the site of injury, coupled with enhanced local synthesis, allows it to act as a significant retrograde injury signal. The activated Luman is transported back to the cell in an importin-β-dependent manner, where it serves as a critical regulator of the intrinsic ability of sensory neurons to regenerate their axon (Ying et al., 2014). In addition to Luman being retrogradely transported from the injury site, the accumulation of axonal GRP78 and CHOP distal to a 1 d nerve ligation site in nerves injury-conditioned 1 d before ligation supports that these Luman-regulated axonal UPR transcripts and proteins may also serve vital roles as retrograde injury signals. Finally, the postinjury time frame examined in this study is consistent with these cellular events being part of the inductive phase of sensory axon regeneration, which we have shown are dependent on the early rises in BDNF expression following injury, while the chronic phase is not (Geremia et al., 2010; Zigmond, 2012). Whether axotomy-induced increases in Luman expression are also regulated by BDNF is not presently known, but preliminary studies support that injury-associated increases in Luman, the UPR, and SREBP1 expression in vivo are transient, with marked reductions in expression observed by 4 d after axotomy (Z. Ying, N.A. McLean, J.M. Johnston, and V.M.K. Verge, unpublished observations).

In conclusion, these findings demonstrate that an extensive Luman-regulated UPR, including cholesterol regulation, is activated in axotomized DRG neurons and axons. Further, both UPR induction and cholesterol supplementation were found to contribute to the intrinsic regenerative axon growth capacity of sensory neurons, thereby providing novel therapeutic targets for improved nerve regeneration.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR RT733698 and CIHR MOP74747 and Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation SHRF 2803 Grants to V.M.K.V., Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Discovery Grant to V.M., and China Scholarship Council 2010603017 and University of Saskatchewan College of Graduate Studies scholarship to Z.Y. We thank N. Rapin for excellent technical assistance and Drs. L. Baillie and S. Mulligan for their expert help with two-photon imaging.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Basseri and Austin, 2012.Basseri S, Austin RC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:841362. doi: 10.1155/2012/841362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese et al., 2010.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antiox Redox Signal. 2010;13:1763–1811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan et al., 2011.Colgan SM, Hashimi AA, Austin RC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid dysregulation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha et al., 2008.Cunha DA, Hekerman P, Ladrière L, Bazarra-Castro A, Ortis F, Wakeham MC, Moore F, Rasschaert J, Cardozo AK, Bellomo E, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Lupi R, Hai T, Herchuelz A, Marchetti P, Rutter GA, Eizirik DL, Cnop M. Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2308–2318. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DenBoer et al., 2005.DenBoer LM, Hardy-Smith PW, Hogan MR, Cockram GP, Audas TE, Lu R. Luman is capable of binding and activating transcription from the unfolded protein response element. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly et al., 2011.Donnelly CJ, Willis DE, Xu M, Tep C, Jiang C, Yoo S, Schanen NC, Kirn-Safran CB, van Minnen J, English A, Yoon SO, Bassell GJ, Twiss JL. Limited availability of ZBP1 restricts axonal mRNA localization and nerve regeneration capacity. EMBO J. 2011;30:4665–4677. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero et al., 2013.Favero CB, Henshaw RN, Grimsley-Myers CM, Shrestha A, Beier DR, Dwyer ND. Mutation of the BiP/GRP78 gene causes axon outgrowth and fasciculation defects in the thalamocortical connections of the mammalian forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:677–696. doi: 10.1002/cne.23199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Hernando and Moore, 2011.Fernández-Hernando C, Moore KJ. MicroRNA modulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2378–2382. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouillet et al., 2012.Fouillet A, Levet C, Virgone A, Robin M, Dourlen P, Rieusset J, Belaidi E, Ovize M, Touret M, Nataf S, Mollereau B. ER stress inhibits neuronal death by promoting autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:915–926. doi: 10.4161/auto.19716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fünfschilling et al., 2012.Fünfschilling U, Jockusch WJ, Sivakumar N, Möbius W, Corthals K, Li S, Quintes S, Kim Y, Schaap IA, Rhee JS, Nave KA, Saher G. Critical time window of neuronal cholesterol synthesis during neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7632–7645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1352-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geremia et al., 2010.Geremia NM, Pettersson LM, Hasmatali JC, Hryciw T, Danielsen N, Schreyer DJ, Verge VM. Endogenous BDNF regulates induction of intrinsic neuronal growth programs in injured sensory neurons. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanz et al., 2003.Hanz S, Perlson E, Willis D, Zheng JQ, Massarwa R, Huerta JJ, Koltzenburg M, Kohler M, van-Minnen J, Twiss JL, Fainzilber M. Axoplasmic importins enable retrograde injury signaling in lesioned nerve. Neuron. 2003;40:1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi et al., 2007.Hayashi A, Kasahara T, Iwamoto K, Ishiwata M, Kametani M, Kakiuchi C, Furuichi T, Kato T. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced XBP1 splicing during brain development. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34525–34534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz and Mollereau, 2014.Hetz C, Mollereau B. Disturbance of endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:233–249. doi: 10.1038/nrn3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho et al., 2011.Ho SY, Chao CY, Huang HL, Chiu TW, Charoenkwan P, Hwang E. NeurphologyJ: an automatic neuronal morphology quantification method and its application in pharmacological discovery. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al., 2012.Hu Y, Park KK, Yang L, Wei X, Yang Q, Cho KS, Thielen P, Lee AH, Cartoni R, Glimcher LH, Chen DF, He Z. Differential effects of unfolded protein response pathways on axon injury-induced death of retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2012;73:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung et al., 2012.Jung H, Yoon BC, Holt CE. Axonal mRNA localization and local protein synthesis in nervous system assembly, maintenance and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:308–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun et al., 2009.Kammoun HL, Chabanon H, Hainault I, Luquet S, Magnan C, Koike T, Ferré P, Foufelle F. GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress-induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1201–1215. doi: 10.1172/JCI37007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang et al., 2006.Liang G, Audas TE, Li Y, Cockram GP, Dean JD, Martyn AC, Kokame K, Lu R. Luman/CREB3 induces transcription of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response protein Herp through an ER stress response element. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7999–8010. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01046-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al., 2011.Liu K, Tedeschi A, Park KK, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic mechanisms of axon regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu et al., 1997.Lu R, Yang P, O'Hare P, Misra V. Luman, a new member of the CREB/ATF family, binds to herpes simplex virus VP16-associated host cellular factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5117–5126. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantuano et al., 2011.Mantuano E, Henry K, Yamauchi T, Hiramatsu N, Yamauchi K, Orita S, Takahashi K, Lin JH, Gonias SL, Campana WM. The unfolded protein response is a major mechanism by which LRP1 regulates Schwann cell survival after injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13376–13385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2850-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes et al., 2009.Mendes CS, Levet C, Chatelain G, Dourlen P, Fouillet A, Dichtel-Danjoy ML, Gambis A, Ryoo HD, Steller H, Mollereau B. ER stress protects from retinal degeneration. EMBO J. 2009;28:1296–1307. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merianda and Twiss, 2013.Merianda T, Twiss J. Peripheral nerve axons contain machinery for co-translational secretion of axonally-generated proteins. Neurosci Bull. 2013;29:493–500. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, 2009.Naidoo N. Cellular stress/the unfolded protein response: relevance to sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien et al., 2014.O'Brien PD, Hinder LM, Sakowski SA, Feldman EL. ER stress in diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a new therapeutic target. Antiox Redox Signal. 2014;21:621–633. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohri et al., 2013.Ohri SS, Hetman M, Whittemore SR. Restoring endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggo et al., 2002.Raggo C, Rapin N, Stirling J, Gobeil P, Smith-Windsor E, O'Hare P, Misra V. Luman, the cellular counterpart of herpes simplex virus VP16, is processed by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5639–5649. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5639-5649.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron and Walter, 2007.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf and Curcio, 2009.Rudolf M, Curcio CA. Esterified cholesterol is highly localized to Bruch's membrane, as revealed by lipid histochemistry in wholemounts of human choroid. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:731–739. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghibiglou et al., 2011.Taghibiglou C, Lu J, Mackenzie IR, Wang YT, Cashman NR. Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP1) activation in motor neurons in excitotoxicity and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): Indip, a potential therapeutic peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmer et al., 2013.Volmer R, van der Ploeg K, Ron D. Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217611110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuppalanchi et al., 2012.Vuppalanchi D, Merianda TT, Donnelly C, Pacheco A, Williams G, Yoo S, Ratan RR, Willis DE, Twiss JL. Lysophosphatidic acid differentially regulates axonal mRNA translation through 5′UTR elements. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;50:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis et al., 2005.Willis D, Li KW, Zheng JQ, Chang JH, Smit A, Kelly T, Merianda TT, Sylvester J, van Minnen J, Twiss JL. (2005) Differential transport and local translation of cytoskeletal, injury-response, and neurodegeneration protein mRNAs in axons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:778–791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye and DeBose-Boyd, 2011.Ye J, DeBose-Boyd RA. Regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004754. piia004754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye et al., 2000.Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Davé UP, Prywes R, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying et al., 2014.Ying Z, Misra V, Verge VM. Sensing nerve injury at the axonal ER: activated Luman/CREB3 serves as a novel axonally synthesized retrograde regeneration signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16142–16147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407462111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudin et al., 2008.Yudin D, Hanz S, Yoo S, Iavnilovitch E, Willis D, Gradus T, Vuppalanchi D, Segal-Ruder Y, Ben-Yaakov K, Hieda M, Yoneda Y, Twiss JL, Fainzilber M. Localized regulation of axonal RanGTPase controls retrograde injury signaling in peripheral nerve. Neuron. 2008;59:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng et al., 2001.Zheng JQ, Kelly TK, Chang B, Ryazantsev S, Rajasekaran AK, Martin KC, Twiss JL. A functional role for intra-axonal protein synthesis during axonal regeneration from adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9291–9303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09291.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, 2012.Zigmond RE. Cytokines that promote nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2012;238:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]