Abstract

The balance between positive and negative regulators required for synaptic plasticity must be well organized at synapses. Protein kinase Cα (PKCα) is a major mediator that triggers long-term depression (LTD) at synapses between parallel fibers and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum. However, the precise mechanisms involved in PKCα regulation are not clearly understood. Here, we analyzed the role of diacylglycerol kinase ζ (DGKζ), a kinase that physically interacts with PKCα as well as postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) family proteins and functionally suppresses PKCα by metabolizing diacylglycerol (DAG), in the regulation of cerebellar LTD. In Purkinje cells of DGKζ-deficient mice, LTD was impaired and PKCα was less localized in dendrites and synapses. This impaired LTD was rescued by virus-driven expression of wild-type DGKζ, but not by a kinase-dead mutant DGKζ or a mutant lacking the ability to localize at synapses, indicating that both the kinase activity and synaptic anchoring functions of DGKζ are necessary for LTD. In addition, experiments using another DGKζ mutant and immunoprecipitation analysis revealed an inverse regulatory mechanism, in which PKCα phosphorylates, inactivates, and then is released from DGKζ, is required for LTD. These results indicate that DGKζ is localized to synapses, through its interaction with PSD-95 family proteins, to promote synaptic localization of PKCα, but maintains PKCα in a minimally activated state by suppressing local DAG until its activation and release from DGKζ during LTD. Such local and reciprocal regulation of positive and negative regulators may contribute to the fine-tuning of synaptic signaling.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Many studies have identified signaling molecules that mediate long-term synaptic plasticity. In the basal state, the activities and concentrations of these signaling molecules must be maintained at low levels, yet be ready to be boosted, so that synapses can undergo synaptic plasticity only when they are stimulated. However, the mechanisms involved in creating such conditions are not well understood. Here, we show that diacylglycerol kinase ζ (DGKζ) creates optimal conditions for the induction of cerebellar long-term depression (LTD). DGKζ works by regulating localization and activity of protein kinase Cα (PKCα), an important mediator of LTD, so that PKCα effectively responds to the stimulation that triggers LTD.

Keywords: cerebellum, DGKζ, long-term depression, PKCα, Purkinje cells

Introduction

Many forms of long-term synaptic plasticity have been observed in several brain areas, which are triggered by increases in concentrations or activities of signaling molecules that work positively for synaptic plasticity (Huganir and Nicoll, 2013). In contrast, molecules that negatively regulate these positive regulators are also implicated in synaptic plasticity (Baumgärtel and Mansuy, 2012). One way such negative regulators are thought to be involved is by maintaining low activities of positive regulators at a basal state; yet the inhibitory effects of these negative regulators are reduced upon the induction of synaptic plasticity (Fukunaga et al., 2000; Launey et al., 2004). Another function of negative regulators is to prevent the hyperactivation of positive regulators, which oppositely reduces the probability to induce synaptic plasticity (Khoutorsky et al., 2013). The balance between positive and negative regulators appears to be important to achieve appropriate activities of the signaling network that triggers synaptic plasticity.

In the case of long-term depression (LTD) at synapses between parallel fibers (PFs) and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, a large number of signaling molecules have been implicated to be involved (Ito, 2002; Hirano, 2013; Kim and Tanaka-Yamamoto, 2013). Many of these molecules can be categorized as positive regulators, and protein kinase C (PKC) has long been known to be necessary and even sufficient for LTD (Linden and Connor, 1991; Hartell, 1994; De Zeeuw et al., 1998; Endo and Launey, 2003; Kondo et al., 2005). Although the pathway and functions of PKC activation during LTD have been well understood (Hirano, 2013; Kim and Tanaka-Yamamoto, 2013), it is not clear as to how PKC activity is precisely regulated. Another question remains regarding isoform specificity. Although at least 8 isoforms of PKC are expressed in Purkinje cells, PKCα has been reported to be responsible for LTD. The unique PDZ ligand motif in the C terminus of PKCα was shown to be important for its function in LTD (Leitges et al., 2004), suggesting that its binding with the PDZ-domain containing protein PICK1 via this PDZ ligand motif (Staudinger et al., 1997) may be required for its involvement in LTD. However, because PICK1 appears to bind only with activated PKCα (Perez et al., 2001), comprehensive mechanisms explaining the specificity of PKCα remain unclear.

Diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) metabolizes diacylglycerol (DAG) to phosphatidic acid (PA), which is the major pathway to terminate DAG signaling (Sakane et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2009). Therefore, DGK can be considered a negative regulator of PKC, which can be activated by DAG. The DGK isoform DGKζ was shown to be targeted to excitatory synapses by its interaction with postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) family proteins and to regulate synaptic morphology and functions in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (K. Kim et al., 2009, 2010; Seo et al., 2012). In a study using an in vitro assay and cultured cell lines, it was demonstrated that DGKζ reduces PKCα activity by interacting with PKCα and metabolizing DAG, whereas such regulation of PKCα by DGKζ is attenuated by PKCα-dependent phosphorylation of DGKζ and by subsequent dissociation of PKCα from DGKζ (Luo et al., 2003a,b). Given that DGKζ is expressed at high levels in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Hozumi et al., 2003; K. Kim et al., 2009), the mutual regulation of DGKζ and PKCα may be crucial for the local and fine regulation of PKCα activity at synapses upon the stimulation triggering LTD.

In this study, we investigated the involvement of DGKζ in cerebellar LTD using DGKζ-deficient (DGKζ−/−) mice. We found that DGKζ contributes to LTD by regulating the synaptic localization and activities of PKCα, and by releasing PKCα during LTD. Our study demonstrates a novel signaling mechanism that effectively responds to synaptic stimulation via physical and functional interactions between DGKζ and PKCα.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All procedures involving mice were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Korea Institute of Science and Technology. In this study, we used DGKζ−/− mice, which were generated previously (Zhong et al., 2003). For experiments comparing electrophysiological and biochemical properties between wild-type (DGKζ+/+) and DGKζ−/− mice, heterozygous (DGKζ+/−) mice were crossed to produce both DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− littermates. Lentiviral or adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors were stereotaxically injected into the cerebellar cortex of 9- to 11-day-old DGKζ−/− pups. The injected pups were taken care of by foster ICR female mice with pups of similar age.

Patch-clamp recording and live cell imaging.

Chemicals used were obtained from Sigma or Wako Pure Chemical Industries, unless otherwise specified. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from Purkinje cells as described previously (Miyata et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). Briefly, sagittal slices (200 μm) of cerebella from 17- to 25-day-old mice of either sex were bathed in extracellular solution (ACSF) containing the following (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, and 0.01 bicuculline methochloride (Tocris Bioscience). Patch pipettes (resistance 5–6 mΩ) were filled with the following (in mm): 130 potassium gluconate, 2 NaCl, 4 MgCl2, 4 Na2-ATP, 0.4 Na-GTP, 20 HEPES, pH 7.2, and 0.25 EGTA. To visualize increases in intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i), Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB1, Invitrogen, 0.25 mm) was added instead of EGTA. When GFP-conjugated proteins were virally expressed, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from Purkinje cells expressing GFP, which were identified by GFP fluorescence under a microscope (Olympus BX61WI). The imaging of GFP was performed using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000).

EPSCs were evoked in Purkinje cells (holding potential of −70 mV) by activating PFs with a glass stimulating electrode on the surface of the molecular layer (PF-EPSCs). PF-EPSCs were acquired and analyzed using pClamp software (Molecular Devices). To evoke LTD by electrical stimulation (PF&ΔV), PF stimuli were paired with Purkinje cell depolarization (0 mV, 200 ms), 300× at 1 Hz. To test the effects of a shorter (200 PF&ΔV) or longer (500 PF&ΔV) duration of stimulation, the same stimulus was applied 200 or 500 times at 1 Hz, respectively. For the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP, PF), only PF stimuli were applied 300× at 1 Hz. Data were accepted if the series resistance changed by <20%, the input resistance was >80 mΩ, and the holding current changed by <20%. Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded as described previously (Yamamoto et al., 2012). To detect slow EPSCs, a burst of PF stimulation (100 Hz, 100 ms) was applied in the presence of the AMPAR antagonist CNQX (25 μm, Tocris Bioscience) (Hartmann et al., 2008).

Live cell imaging of OGB1 was performed using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse FN1) equipped with an iXon Ultra 897 camera (Andor) and NIS elements imaging software (Nikon). Images of the cells were taken at 30 Hz, before, during, and after the PF burst stimulation (100 Hz, 100 ms). The timing of PF stimulation was controlled by the trigger-out feature of NIS elements software. The ratio of increased fluorescence to basal fluorescence (ΔF/F0) was calculated from the stimulated Purkinje cell dendrites using the equation ΔF/F0 = ((F − Fb) − (F0 − Fb))/(F0 − Fb), in which F, F0, and Fb are fluorescence intensity in the ROI at a certain time point, averaged intensity in the ROI before the PF stimulation, and background signals, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and biocytin labeling.

Primary antibodies used were rabbit or guinea pig anti-DGKζ (K. Kim et al., 2009), mouse anti-PKCα (BD Biosciences), mouse (Sigma), rabbit (Sigma), or guinea pig (Synaptic Systems) anti-calbindin, mouse anti-metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma), rabbit anti-synapsin 1/2 (Synaptic Systems), mouse anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (MAPK/Erk, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phosphorylated MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-GluA2 (Millipore), rabbit anti-PICK1 (Abcam), and rabbit anti-PSD-93/chapsyn-110 (1634) (M.H. Kim et al., 2009) antibodies. Secondary antibodies used were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare), HRP-conjugated anti-guinea pig IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), AlexaFluor-647-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), AlexaFluor-647-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), AlexaFluor-488-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-guinea pig IgG (Invitrogen), and AlexaFluor-405-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation analyses using cerebellar slices were performed as described previously with slight modifications (Yamamoto et al., 2012). Briefly, freshly prepared cerebellar slices were subjected to chemical LTD stimulation after incubating for 30 min in normal ACSF. For chemical LTD stimulation, slices were treated with extracellular solution containing 50 mm K+ and 10 μm glutamate (K-glu) for 5 min. Slices were then lysed in lysis buffer containing the following: 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 8, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 μm staurosporine (Calbiochem), 1 × proteinase inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque), and 1 × phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque). After homogenization and centrifugation, mouse anti-PKCα was added to the supernatant (∼500 μg protein) to immunoprecipitate PKCα and rotated at 4°C followed by the addition of 20 μl protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). The immunoprecipitate was suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to immunoblotting analyses to detect DGKζ and PKCα. To quantify the binding of PKCα to DGKζ, band intensities were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), and the ratios of normalized band intensities of DGKζ to those of PKCα were then calculated. The binding between DGKζ and PSD-93 in the cerebellum was confirmed by immunoprecipitation with a PSD-93 antibody of cerebellar lysates that were solubilized by 1% sodium deoxycholate (K. Kim et al., 2009).

To test the binding between DGKζ and PKCα, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3-FLAG-DGKζ (wild-type) and pcDNA3-PKCα (wild-type or mutant). Approximately 45 h after transfection, cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing the following: 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 8, 1 mm EDTA, 0.2% NP-40 Alternative (Calbiochem), 10% glycerol, 1 × proteinase inhibitor mixture, and 1 × phosphatase inhibitor mixture. Cell lysates were centrifuged to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation using M2 FLAG beads (Sigma). The immunoprecipitates were then subjected to immunoblotting analyses to detect FLAG-tagged DGKζ and PKCα.

Crude synaptosome (P2) and cytosolic fractions (S2) were prepared as described previously (Kohda et al., 2013). In brief, the whole cerebellum from DGKζ+/+ or DGKζ−/− mice was dissected out and homogenized in HEPES-buffered sucrose (0.32 m sucrose, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.3, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 × proteinase inhibitor mixture, and 1 × phosphatase inhibitor mixture). After removal of the nuclear fraction by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min. The resulting pellet was suspended in HEPES-buffered sucrose, and the supernatant and the suspended pellet were used as S2 and P2 fractions, respectively. The S2 and P2 fractions were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to immunoblotting analyses to detect PKCα, β-actin, synapsin, AMPAR subunit GluA2, DGKζ, and PICK1. For quantification, band intensities were measured using ImageJ software. Because the ratios of the band intensities of β-actin in the P2 fractions to those in the S2 fractions did not significantly differ between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− cerebella (p = 0.197, Student's t test), the band intensities of PKCα, synapsin, and GluA2 were normalized to those of β-actin. Then, the ratios of the normalized band intensities in the P2 fractions to those in the S2 fractions were calculated (r = (XP2/β − actinP2)/(XS2/β − actinS2), where XP2 and XS2 are the band intensities of PKCα, synapsin, or GluA2 in the P2 and S2 fractions, respectively, and β-actinP2 and β-actinS2 are the band intensities of β-actin in the P2 and S2 fractions, respectively.

For the labeling of Purkinje cells using biocytin, whole-cell patch clamps were made with internal solution including 0.5% biocytin (Tocris Bioscience) and AlexaFluor-488 (Invitrogen). After waiting 20 min for the diffusion of the internal solution into Purkinje cells, slices were immediately fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated with AlexaFluor-488-conjugated streptavidin (1:500, Invitrogen). Z-stack images of single Purkinje cells and digitally magnified images of distal dendrites were acquired by an A1R laser-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon) for Sholl analysis and the counting of spine numbers, respectively.

For immunohistochemistry of cerebellar slices, mice were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with 4% PFA in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The cerebellum was postfixed for 3 h at 4°C, followed by sectioning (40 μm) using a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1200S). Sections were blocked in 5% normal goat serum in PBS, incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed several times, and then incubated in secondary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature. Single optical sections of confocal images were acquired by an A1R laser scanning confocal microscope.

To analyze MAPK phosphorylation, freshly prepared cerebellar slices were subjected to chemical LTD stimulation for 5 min and washed in normal ACSF for 0–10 min. Slices were then lysed in the same lysis buffer as that used for immunoprecipitation analyses. After homogenization, samples were centrifuged to remove cell debris. The lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE to detect MAPK and phosphorylated MAPK by immunoblotting. To quantify MAPK phosphorylation, band intensities were measured by ImageJ, and the ratio of phosphorylated MAPK to total MAPK was then calculated.

In vivo viral injection.

To make lentiviral vectors, constructs for vesicular stomatitis virus G- pseudotyped lentiviral vectors were provided by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Hanawa et al., 2002). Viral vectors that express GFP-DGKζ-WT or GFP-DGKζ-ΔC under the control of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) promoter were produced as described previously (Torashima et al., 2006) with slight modifications. In brief, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with a mixture of four plasmids, pCAGkGP1R, pCAG4RTR2, pCAG-vesicular stomatitis virus G, and either pCL20c-MSCV-GFP-DGKζ-WT or pCL20c-MSCV-GFP-DGKζ-ΔC, using calcium phosphate. At ∼46 h after transfection, viral vectors were harvested from the culture medium by ultracentrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 90 min, suspended in Hanks balanced salt solution, and stored at −80°C.

To make AAV vectors, an AAV vector plasmid with the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α (CaMKIIα) promoter that was developed by the Deisseroth laboratory was obtained from Addgene. AAV vectors were produced according to the protocol provided by the Salk Institute Gene Transfer, Targeting and Therapeutics core facility (http://vectorcore.salk.edu/index.php) with slight modifications. In brief, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with a mixture of three plasmids: pHelper (Agilent Technologies), serotype 1 plasmid (a gift from Dr. Jinhyun Kim, Korea Institute of Science and Technology), and pAAV-CaMKIIα-GFP, pAAV-CaMKIIα-GFP-DGKζ-WT, pAAV-CaMKIIα-GFP-DGKζ-KD, or pAAV-CaMKIIα-GFP-DGKζ-SN using calcium phosphate. At ∼72 h after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed by sonication. Then, AAV vectors were collected from the cell lysate by gradient ultracentrifugation using a Beckman NVT90 rotor at 48,000 rpm for 47 min, dialyzed in PBS with sucrose, concentrated by centrifugal filter devices (Millipore), and stored at −80°C.

Viral vectors were injected into the cerebellum of 9- to 11-day-old DGKζ−/− pups, as described previously (Torashima et al., 2006) with slight modifications. Briefly, mice were anesthetized by Avertin (250 μg/g body weight) and mounted on a stereotaxic stage. The cranium over the cerebellar vermis was exposed by a midline sagittal incision. A hole was made ∼3 mm caudal from λ by the tip of forceps, and a glass needle was placed in lobe IV-V of the cerebellar vermis. The lentiviral solution (2–3 μl total) was injected at a rate of 200 nl/min, and the AAV solution (1 μl total) was injected at three different locations at a rate of 1000 nl/min, using an UltraMicroPump II and Micro4 controller (World Precision Instruments). After the surgery, mice were kept on a heating pad until they recovered from the anesthesia, and then they were returned to their foster ICR mother.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences were determined by the paired or unpaired Student's t test (for two-group comparisons) and one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey or Bonferroni test (for more than two-group comparisons). Statistical analysis of mEPSC amplitude was performed by the Mann-Whitney test. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Results

DGKζ expression in cerebellar Purkinje cells

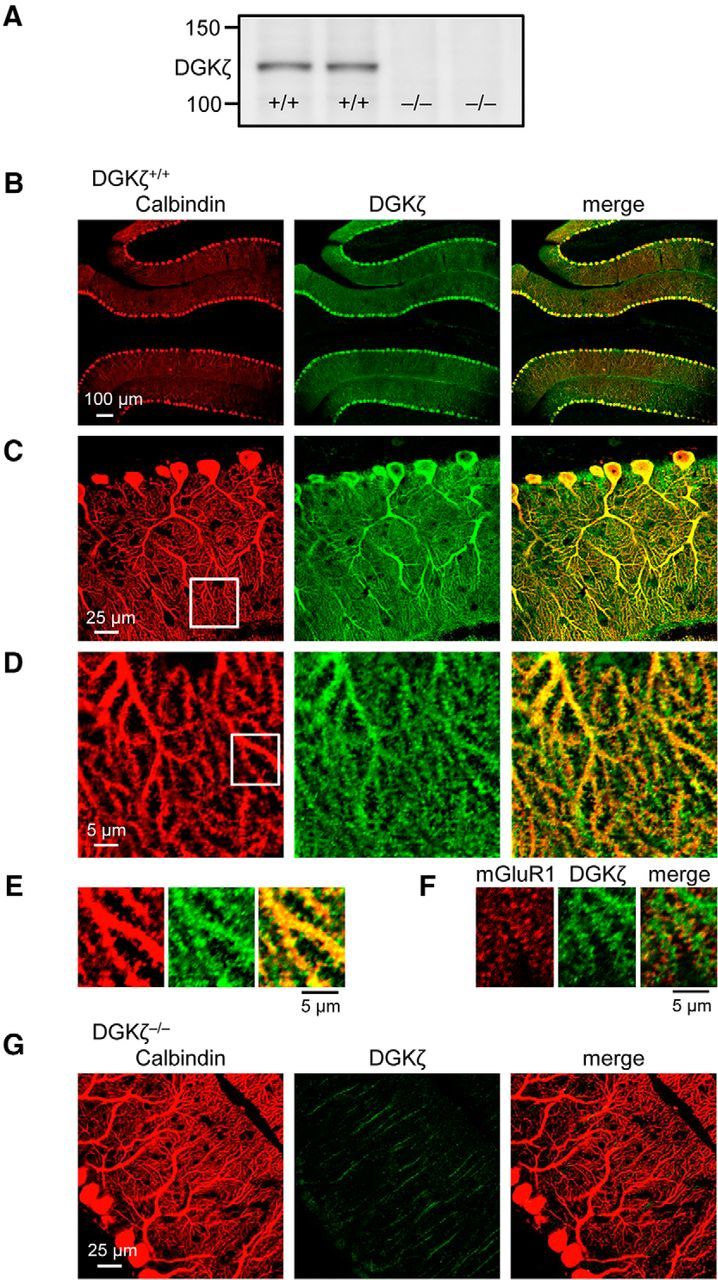

We first confirmed the expression of DGKζ in the cerebellum by Western blot analysis of cerebellar lysates of DGKζ+/+ mice (Fig. 1A). To investigate the distribution of endogenous DGKζ in the cerebellum, we performed immunohistochemical staining of sagittal cerebellar slices. Consistent with previous reports (Hozumi et al., 2003; K. Kim et al., 2009), the immunosignal of DGKζ was predominantly detected in cerebellar Purkinje cells in DGKζ+/+ mice (Fig. 1B,C). Magnified images around distal dendrites showed that DGKζ also exists in the distal dendrites of Purkinje cells as well as their protrusive structures (Fig. 1D,E). We confirmed that these protrusions are dendritic spines by their overlap with mGluR1 (Fig. 1F), which is concentrated on dendritic spines (Takács et al., 1997; Yoshida et al., 2006). In contrast, we did not detect clear signals in DGKζ−/− mice by both Western blot (Fig. 1A) and immunohistochemical (Fig. 1G) analyses, confirming that the DGKζ antibody used in this study (K. Kim et al., 2009) specifically detects DGKζ. These data indicate that DGKζ is strongly expressed in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Because DGKζ exists not only in soma and proximal dendrites, but also in distal dendrites and dendritic spines of Purkinje cells, DGKζ might play roles in the regulation of Purkinje cell synapses.

Figure 1.

Expression of DGKζ in cerebellar Purkinje cells. A, Immunoblot using an antibody against DGKζ in cerebellar lysates of two DGKζ+/+ and two DGKζ−/− mice. B–G, Confocal images of DGKζ+/+ (B–F) or DGKζ−/− (G) cerebellar slices double stained with antibodies against calbindin (red) and DGKζ (green; B–E, G) or with antibodies against mGluR1 (red) and DGKζ (green; F).

Cerebellar LTD is impaired in DGKζ−/− mice

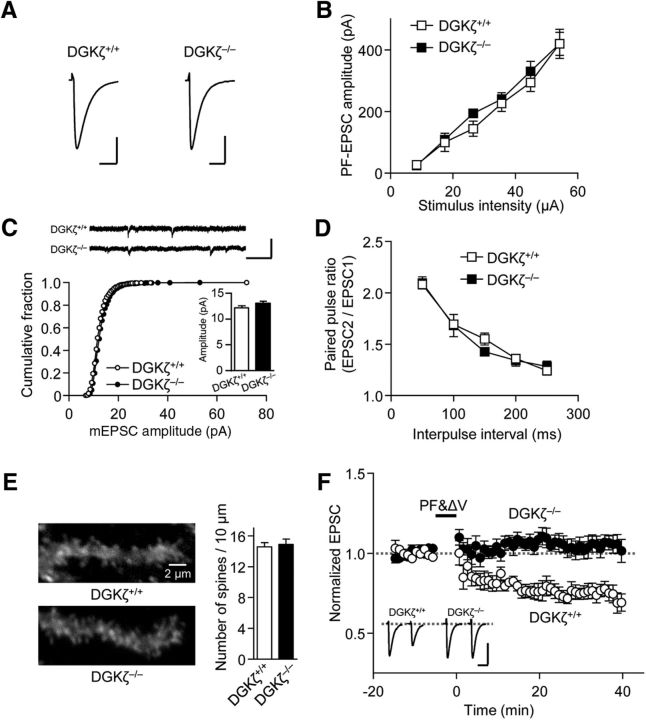

To investigate whether DGKζ plays a role in the regulation of cerebellar Purkinje cell synapses, we compared basal synaptic transmission at PF-Purkinje cell synapses between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice (Fig. 2A). The kinetics of EPSC were not different between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice (10%–90% rise time: DGKζ+/+, 2.37 ± 0.2 ms, n = 10; DGK−/−, 2.03 ± 0.11 ms, n = 9, p = 0.171; decay time constant: DGKζ+/+, 11.9 ± 1.1 ms, n = 10, DGKζ−/−, 10.4 ± 0.7 ms, n = 9, p = 0.24, Student's t test). The relationship between the stimulus intensity and the amplitude of PF-EPSC was also unchanged in DGKζ−/− mice (Fig. 2B, p = 0.926, two-way ANOVA). Consistently, distributions of mEPSC amplitudes recorded in DGKζ−/− mice were equivalent to those in DGKζ+/+ mice, and their averaged amplitudes were not significantly different (Fig. 2C, p = 0.061, Mann–Whitney test), indicating that the amplitude of PF-EPSC was not affected by the lack of DGKζ. Likewise, presynaptic glutamate release did not appear to be affected because the paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) ratio of PF-EPSC in DGKζ−/− mice was comparable with that in DGKζ+/+ mice (Fig. 2D, p = 0.745, two-way ANOVA). In addition, we investigated the spine density by visualizing dendritic spines of Purkinje cells using biocytin, which was introduced through a patch pipette. We found that there was no significant difference in spine density between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice (Fig. 2E, p = 0.7, Student's t test). Thus, DGKζ deficiency does not affect basal synaptic transmission and synaptic density at PF-Purkinje cell synapses. This is in clear contrast to the case of hippocampal synapses, in which spine density and excitatory synaptic transmission are reduced in DGKζ−/− mice (K. Kim et al., 2009), suggesting that DGKζ plays specific roles in Purkinje cell synapses.

Figure 2.

DGKζ deficiency impairs cerebellar LTD but has no effect on basal transmission, presynaptic release, and spine density. A, Averaged traces of PF-EPSCs recorded in DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells. Calibration: 100 pA, 25 ms. B, Amplitudes of PF-EPSCs elicited in DGKζ+/+ (n = 4) or DGKζ−/− (n = 6) Purkinje cells by PF stimuli of increasing intensity (8, 17, 27, 36, 45, and 54 μA). C, Amplitudes of mEPSCs in DGKζ+/+ (n = 11) and DGKζ−/− (n = 10) Purkinje cells, shown as cumulative distributions and bar graphs (inset). Raw exemplar traces are shown at the top. Calibration: 50 pA, 0.5 s. D, PPF ratios of PF-EPSCs elicited in DGKζ+/+ (n = 5) or DGKζ−/− (n = 8) Purkinje cells by a pair of PF stimuli with different intervals (50–250 ms). E, Images of distal dendrites of biocytin-labeled Purkinje cells (left) and spine numbers per 10 μm dendritic segments (right: DGKζ+/+, n = 6; DGKζ−/−, n = 7). F, Time course of LTD induced by PF&ΔV (1 Hz, 300×) in DGKζ+/+ (n = 10) or DGKζ−/− (n = 7) Purkinje cells. Exemplar traces of PF-EPSCs shown in F as well as in the subsequent figures are single (unaveraged) responses before (left) and after (20–30 min, right) stimulation. Calibration: 200 pA, 20 ms. PF-EPSC amplitudes shown in F as well as the subsequent figures presenting the time course of PF-EPSCs are normalized to their mean prestimulation level. Error bars indicate SEM.

We next examined the involvement of DGKζ in LTD. Whereas LTD was induced by pairing PF stimulation with Purkinje cell depolarization at 1 Hz for 300 s (PF&ΔV) in Purkinje cells of DGKζ+/+ mice, LTD was impaired in Purkinje cells of DGKζ−/− mice (Fig. 2F). The reduction in PF-EPSC calculated at 20–30 min after PF&ΔV was significantly smaller in DGKζ−/− mice than in DGKζ+/+ mice (DGKζ+/+, 24.3 ± 3.9%, n = 10; DGKζ−/−, −5.77 ± 4.9%, n = 7; p < 0.01, Student's t test). This result indicates that DGKζ is involved in cerebellar LTD.

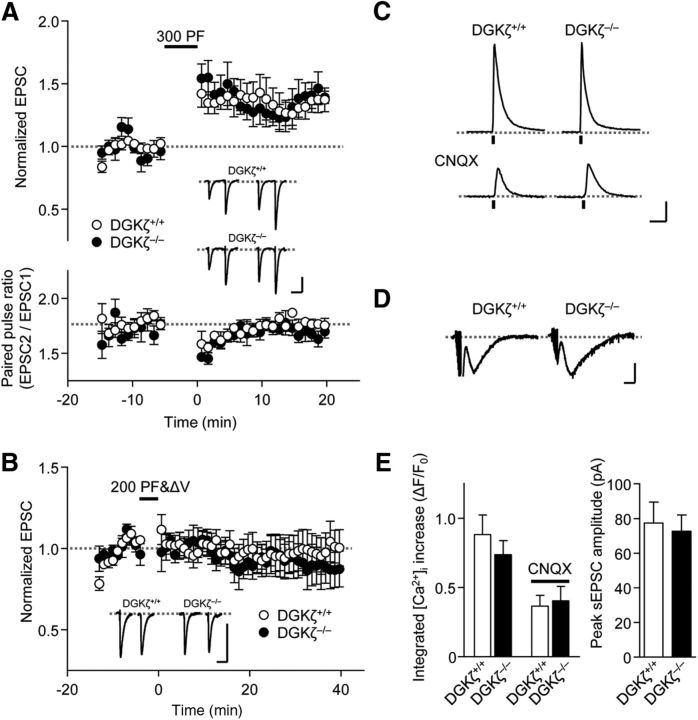

We also tested the involvement of DGKζ in another form of synaptic plasticity. LTP at PF-Purkinje cell synapses was triggered by PF stimulation at 1 Hz for 300 s in DGKζ+/+ slices (Fig. 3A). Consistent with previous reports (Lev-Ram et al., 2002; Coesmans et al., 2004; Belmeguenai and Hansel, 2005), LTP triggered by a 1 Hz PF stimulation was expressed postsynaptically because PPF ratios were not altered by the stimulation (Fig. 3A). LTP was also observed in DGKζ−/− slices, and the potentiation of PF-EPSC in DGKζ−/− slices was similar to that in DGKζ+/+ slices (Fig. 3A; DGKζ+/+, 32.5 ± 8.4%, n = 8; DGKζ−/−, 39.7 ± 8.8%, n = 6; p = 0.572, Student's t test). To further confirm that LTD triggered by 300 s of PF&ΔV is altered specifically at PF-Purkinje cell synapses, we tested the effects of a shorter duration (200 s) of pairing PF stimulation with Purkinje cell depolarization on PF-EPSC. With this stimulation protocol, PF-EPSC was neither potentiated nor depressed in DGKζ+/+ slices (Fig. 3B). Likewise, PF-EPSC was also unaltered in DGKζ−/− slices (Fig. 3B). The changes in PF-EPSC that were calculated 20–30 min after this shorter duration of stimulation were not significantly different between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− slices (DGKζ+/+, 4.24 ± 11%, n = 7; DGKζ−/−, 5.87 ± 8.8%, n = 6; p = 0.912, Student's t test). These results indicate that LTD is impaired specifically at PF-Purkinje cell synapses.

Figure 3.

LTP at PF-Purkinje cell synapses is unaffected in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells. A, Time course of LTP induced by PF stimuli (1 Hz, 300×) in DGKζ+/+ (n = 7) and DGKζ−/− (n = 5) Purkinje cells. Bottom, Accompanying PPF ratios of PF-EPSC elicited by a pair of PF stimuli with a 100 ms interval. B, Time course of changes in PF-EPSC amplitudes before and after a pairing stimulation of PF with Purkinje cell depolarization (1 Hz, 200×) recorded from DGKζ+/+ (n = 7) and DGKζ−/− (n = 6) Purkinje cells. C, Changes in OGB1 fluorescence (ΔF/F0) measured in DGKζ+/+ or DGKζ−/− Purkinje cell dendrites in the absence or presence of CNQX (25 μm) upon burst PF stimulation at 100 Hz for 100 ms. Calibration: 0.5 ΔF/F0, 1 s. D, Representative traces of slow EPSC elicited by burst PF stimulation and recorded from DGKζ+/+ or DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells in the presence of CNQX. Calibration: 50 pA, 200 ms. E, Summary of OGB1 fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0) and peak amplitudes of slow EPSCs (n = 10, n = 16). Error bars indicate SEM.

It is well known that LTD requires mGluR activation at PF synapses as well as increases in [Ca2+]i, the latter of which results from Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from IP3 receptors (Finch et al., 2012). We tested whether a deficiency of DGKζ affects these functions by applying a burst of PF stimulation (100 Hz, 100 ms). The [Ca2+]i increase in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells was not significantly different from that in DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells (Fig. 3C,E, p = 0.4, Student's t test). To investigate the functions of the mGluR and IP3 receptor, CNQX was applied to the extracellular solutions. The increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3C,E, p = 0.77, Student's t test) and slow EPSCs (Fig. 3D,E, p = 0.75, Student's t test) in the presence of CNQX was also similar between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells. These results suggest that a deficiency of DGKζ does not affect the signaling upstream of an increase in [Ca2+]i.

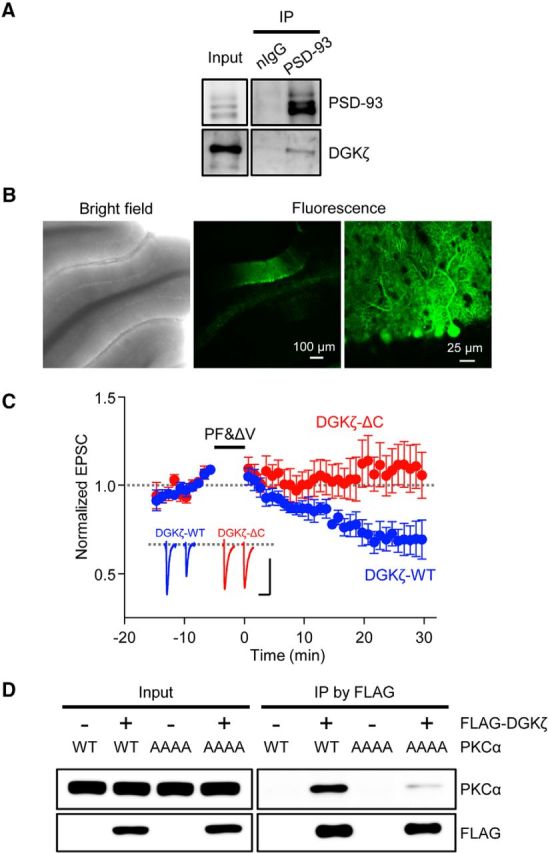

PKCα is mislocalized in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of LTD impairment in DGKζ−/− mice, we considered the involvement of the interaction of DGKζ with PSD-95 family proteins and PKCα (Luo et al., 2003b; K. Kim et al., 2009) and hypothesized that DGKζ promotes the synaptic targeting of PKCα via its interaction with PSD-95 family proteins in Purkinje cells. We confirmed that DGKζ indeed interacted with PSD-93, a major PSD-95 family protein expressed in Purkinje cells, in the cerebellum (Fig. 4A). To test our hypothesis, we investigated whether the binding of DGKζ to PSD-93 is necessary for LTD induction, by recording LTD in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells expressing wild-type DGKζ (DGKζ-WT) or a mutant form of DGKζ lacking the C-terminal PDZ binding motif (DGKζ-ΔC) that is required for the binding of DGKζ to PSD-95 family proteins (K. Kim et al., 2009). Lentiviral vectors expressing DGKζ-WT or DGKζ-ΔC fused with GFP were injected into the cerebellum of DGKζ−/− mice. The expression of DGKζ was mainly observed in Purkinje cells (Fig. 4B), as was expected from a report showing that lentiviral vectors driven by the MSCV promoter successfully promoted the expression of molecules in Purkinje cells (Torashima et al., 2006). Expression of DGKζ-WT in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells restored LTD, confirming that DGKζ is required for LTD (Fig. 4C). However, expression of DGKζ-ΔC in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells failed to restore LTD (Fig. 4C). The depression of PF-EPSC in cells expressing DGKζ-ΔC was significantly smaller than that in cells expressing DGKζ-WT (DGKζ-WT, 30 ± 7%, n = 6; DGKζ-ΔC, −9.82 ± 12%, n = 8; p < 0.05, Student's t test). These results indicate that the interaction of DGKζ with PSD-93 via its PDZ binding motif is required for cerebellar LTD.

Figure 4.

Binding of DGKζ with PSD-95 family proteins is required for LTD. A, Immunoblot of coimmunoprecipitated DGKζ and precipitated PSD-93 in DGKζ+/+ cerebellum. Normal IgG (nIgG) was used as a control. B, Bright-field and fluorescence images of live cerebellar slices obtained from a DGKζ−/− mouse injected with a lentiviral vector expressing GFP-DGKζ-WT. C, Time course of LTD induced by PF&ΔV (1 Hz, 300×) in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT (blue circles, n = 6) and DGKζ-ΔC (red circles, n = 8). Error bars indicate SEM. D, Immunoblot of coimmunoprecipitated PKCα-WT or PKCα-AAAA mutant, and immunoprecipitated FLAG-DGKζ in HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-DGKζ together with either PKCα-WT or PKCα-AAAA.

By immunoprecipitation analysis using lysates from HEK293T cells expressing DGKζ and PKCα, we confirmed that DGKζ interacts with PKCα (Fig. 4D). A study previously demonstrated that LTD impairment in PKCα-knocked down Purkinje cells was rescued by the expression of wild-type PKCα, but not by the expression of a PKCα mutant (PKCα-AAAA), in which the unique PDZ-binding motif (QSAV) in the C terminus was replaced with 4 alanine residues (Leitges et al., 2004). Therefore, we tested the interaction of DGKζ with PKCα-AAAA. Interestingly, the interaction was severely reduced compared with that between DGKζ and wild-type PKCα (Fig. 4D), indicating that the PDZ-binding motif in PKCα is involved in its interaction with DGKζ. Together with the study showing the importance of the PDZ-binding motif in PKCα for LTD (Leitges et al., 2004), this result supports the idea that the interaction of PKCα with DGKζ via its PDZ-binding motif is required for LTD.

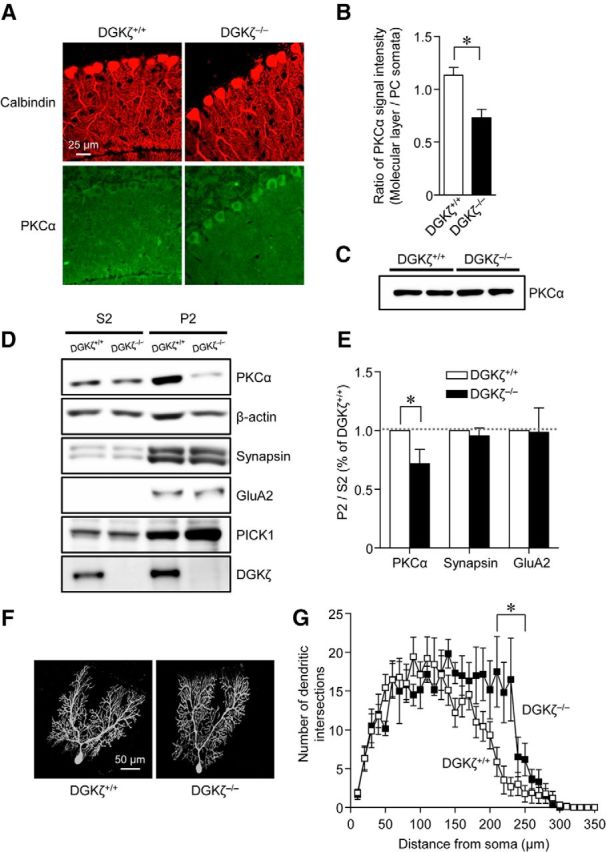

To directly demonstrate that PKCα is mislocalized in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells, we next performed immunohistochemical staining of cerebellar slices with antibodies against calbindin and PKCα, and we examined the localization of endogenous PKCα in Purkinje cells of DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− slices. In DGKζ+/+ slices, immunosignals of PKCα were detected equally in both Purkinje cell soma and the molecular layer, the latter of which is mostly occupied by Purkinje cell dendrites (Fig. 5A). The ratio of PKCα staining in the molecular layer to that in soma was 1.13 ± 0.1 (Fig. 5B), indicating the ubiquitous distribution of PKCα throughout DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells. In contrast, PKCα staining in Purkinje cell soma was enhanced in DGKζ−/− slices (Fig. 5A). The ratio of PKCα staining in the molecular layer to that in soma in DGKζ−/− slices was significantly decreased compared with the ratio in DGKζ+/+ slices (Fig. 5B, p < 0.01, Student's t test). Because the total amount of endogenous PKCα was not altered by the loss of DGKζ (Fig. 5C), an alteration of PKCα distribution is not due to an increase or decrease in the total amount of PKCα in Purkinje cells. Furthermore, we measured the amount of PKCα in the fractionated components of the cerebellum: cytosolic fractions (S2) and crude synaptosomal fractions (P2). The P2 fraction was confirmed by the concentration of synaptic proteins, namely, the GluA2 subunit of the AMPAR, PICK1, and synapsin (Fig. 5D). In the DGKζ−/− cerebellum, the amount of PKCα in P2 fractions was reduced compared with that in the DGKζ+/+ cerebellum, whereas the amount of the GluA2 and synapsin was similar to those in the DGKζ+/+ cerebellum (Fig. 5D). To quantify the amount of various proteins in the fractions, we calculated the ratio of band intensities in the P2 fractions to those in the S2 fractions (Fig. 5E). The ratio of PKCα was significantly lower in the DGKζ−/− cerebellum than that in the DGKζ+/+ cerebellum, whereas ratios for GluA2 and synapsin were comparable between the DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− cerebellum. These results indicate that a lower amount of PKCα is localized in synapses and dendrites of DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells than DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells.

Figure 5.

Reduced dendritic and synaptic localization of PKCα in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells. A, Images of DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− cerebellar slices double stained with antibodies against calbindin and PKCα. B, The ratio of the PKCα signal in the molecular layer to that in the soma (DGKζ+/+, n = 24; DGKζ−/−, n = 24). C, Immunoblotting using an antibody against PKCα in DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− cerebellar lysates. D, Immunoblotting using antibodies against PKCα, β-actin, synapsin, GluA2, PICK1, and DGKζ in S2 and P2 fractions obtained from DGKζ+/+ or DGKζ−/− cerebellum. E, Ratios of PKCα, synapsin, and GluA2 signals in P2 fractions to those in S2 fractions (DGKζ+/+, n = 9; DGKζ−/−, n = 9). Ratios are normalized to those of DGKζ+/+ cerebellum. B, E, Statistically significant difference between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice: B, *p < 0.01 (Student's t test); E, *p < 0.05 (Student's t test). F, Images of biocytin-labeled Purkinje cells of DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice. G, Sholl analysis of the number of dendritic intersections in DGKζ+/+ (n = 9) and DGKζ−/− (n = 6) Purkinje cells. *Statistically significant difference between DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells (p < 0.05, Student's t test). Open and filled symbols represent results obtained from DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells, respectively. In all graphs, error bars indicate SEM.

We also tested whether PKCα activity is reduced in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cell dendrites. Previous studies suggested that PKCα activation reduces the dendritic branching of Purkinje cells (Gundlfinger et al., 2003). We thus examined the dendritic branching pattern of biocytin-labeled Purkinje cells in DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− mice (Fig. 5F). Sholl analysis demonstrated that dendritic branching was enhanced in distal dendrites of DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells compared with DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells (Fig. 5G, whole dendrites, p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA; dendrites at a distance of 210–250 μm, p < 0.05, Student's t test). This result suggests that PKCα activity is reduced in Purkinje cell dendrites of DGKζ−/− mice. Thus, deletion of DGKζ results in less PKCα localization in synapses as well as dendrites of Purkinje cells, and such mislocalization of PKCα likely leads to the reduced activity of PKCα around synapses and consequently to LTD impairment.

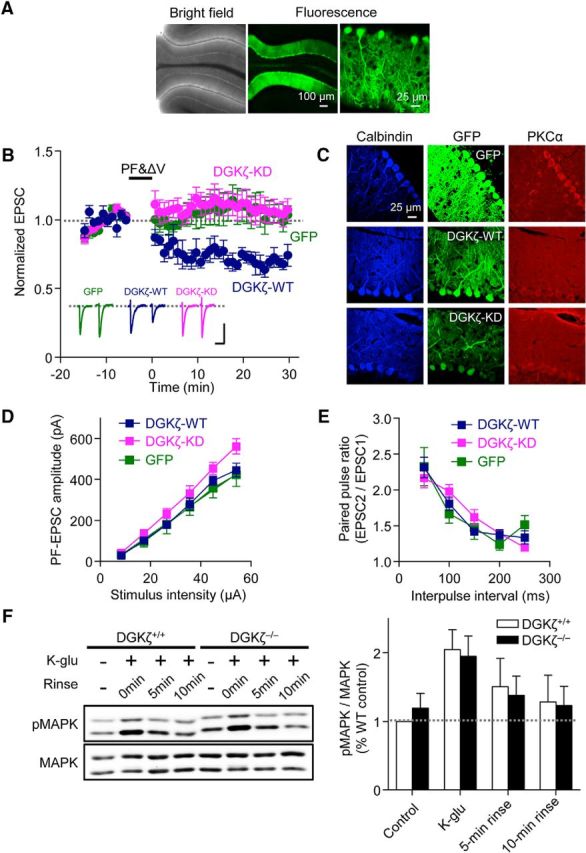

DGKζ kinase activity is required for LTD induction

Our results so far suggest that the PDZ binding motif-dependent anchoring function of DGKζ is important for the proper localization of PKCα and cerebellar LTD. We next examined whether the kinase function of DGKζ, which leads to the metabolization of DAG, is also involved in LTD. For this purpose, we performed rescue experiments using AAV vectors expressing wild-type (DGKζ-WT) or a kinase-dead mutant of DGKζ (DGKζ-KD) fused with GFP, as well as GFP alone. With our experimental conditions, GFP fluorescence was observed almost exclusively in Purkinje cells (Fig. 6A) (Y. Kim et al., 2015). Expression of DGKζ-WT in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells restored LTD (Fig. 6B; 29.9 ± 4.9%, n = 5), as seen in the rescue experiments with lentiviral vectors. In contrast, expression of DGKζ-KD as well as GFP alone failed to restore LTD (Fig. 6B; DGKζ-KD, −6.93 ± 8.6%, n = 8; GFP, −5.03 ± 8.9%, n = 6). ANOVA confirmed the significance of the difference (p < 0.05), and multiple comparison by the Tukey test confirmed that LTD in cells expressing DGKζ-KD was significantly smaller than that in cells expressing DGKζ-WT (p < 0.05) but was not significantly different from LTD in cells expressing GFP alone (p = 0.998). We also analyzed alterations of PKCα distribution by immunohistochemical staining of cerebellar slices expressing DGKζ-WT, DGKζ-KD, or GFP alone, with an antibody against PKCα (Fig. 6C). The ratio of PKCα staining in the molecular layer to that in soma in DGKζ−/− slices expressing DGKζ-WT or DGKζ-KD was both significantly increased compared with the ratio in slices expressing GFP alone (DGKζ-WT, 0.75 ± 0.03, n = 19; DGKζ-KD, 0.66 ± 0.02, n = 23; GFP, 0.59 ± 0.02, n = 22; p < 0.05, Bonferroni test), suggesting that the failure to restore LTD in cells expressing DGKζ-KD is not due to the mislocalization of PKCα. These results indicate that not only the anchoring function, but also the kinase activity, of DGKζ is required for LTD. DGKζ-KD is able to anchor PKCα to synapses but does not metabolize DAG, so that PKCα activity may be enhanced at the synapses of Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-KD. However, it is unlikely that such enhanced PKCα activity triggers LTD and inhibits the further induction of LTD because the PF-EPSC amplitude at the basal level was not depressed, and presynaptic glutamate release was unaltered in cells expressing DGKζ-KD (Fig. 6D,E; PF-EPSC amplitude, p = 0.717; PPF, p = 0.232, two-way ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Kinase activity of DGKζ is required for LTD. A, Bright-field and fluorescence images of live cerebellar slices obtained from a DGKζ−/− mouse injected with an AAV vector expressing GFP-DGKζ-WT. B, Time course of LTD induced by PF&ΔV (1 Hz, 300×) in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT (n = 5), DGKζ-KD (n = 8), or GFP alone (n = 6). C, Images of DGKζ−/− cerebellar slices expressing GFP-DGKζ-WT, GFP-DGKζ-KD, or GFP alone. Slices were double stained with antibodies against calbindin and PKCα. D, Amplitudes of PF-EPSCs elicited in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT (n = 8), DGKζ-KD (n = 10), or GFP alone (n = 7) by PF stimuli of increasing intensity (8, 17, 27, 36, 45, and 54 μA). E, PPF ratios of PF-EPSCs elicited in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT (n = 11), DGKζ-KD (n = 11), or GFP alone (n = 9) by a pair of PF stimuli with different intervals (50–250 ms). B, D, E, Dark blue, magenta, and green symbols represent results obtained from Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT, DGKζ-KD, and GFP alone, respectively. F, Immunoblots detecting MAPK and phosphorylated MAPK (pMAPK) in DGKζ+/+ and DGKζ−/− cerebellar slices that were lysed after incubating in normal ACSF (control), or immediately (K-glu), 5 min (5 min rinse), or 10 min (10 min rinse) after K-glu stimulation. Right, Ratios of the pMAPK signal to the MAPK signal normalized to the ratio in control DGKζ+/+ slices (DGKζ+/+, n = 4; DGKζ−/−, n = 4). Error bars indicate SEM.

DGKζ not only metabolizes DAG, but also produces PA. One possibility by which PA may be involved in LTD is by activation of the MAPK pathway (Rizzo et al., 1999, 2000). However, the level of MAPK activation in DGKζ−/− cerebellar slices was equivalent to that in DGKζ+/+ slices, with or without chemical LTD stimulation (Fig. 6F), suggesting that PA produced by DGKζ is not the major pathway of MAPK activation during LTD. Therefore, the kinase activity of DGKζ appears to be required for reducing DAG signaling, rather than for activating PA signaling, during LTD.

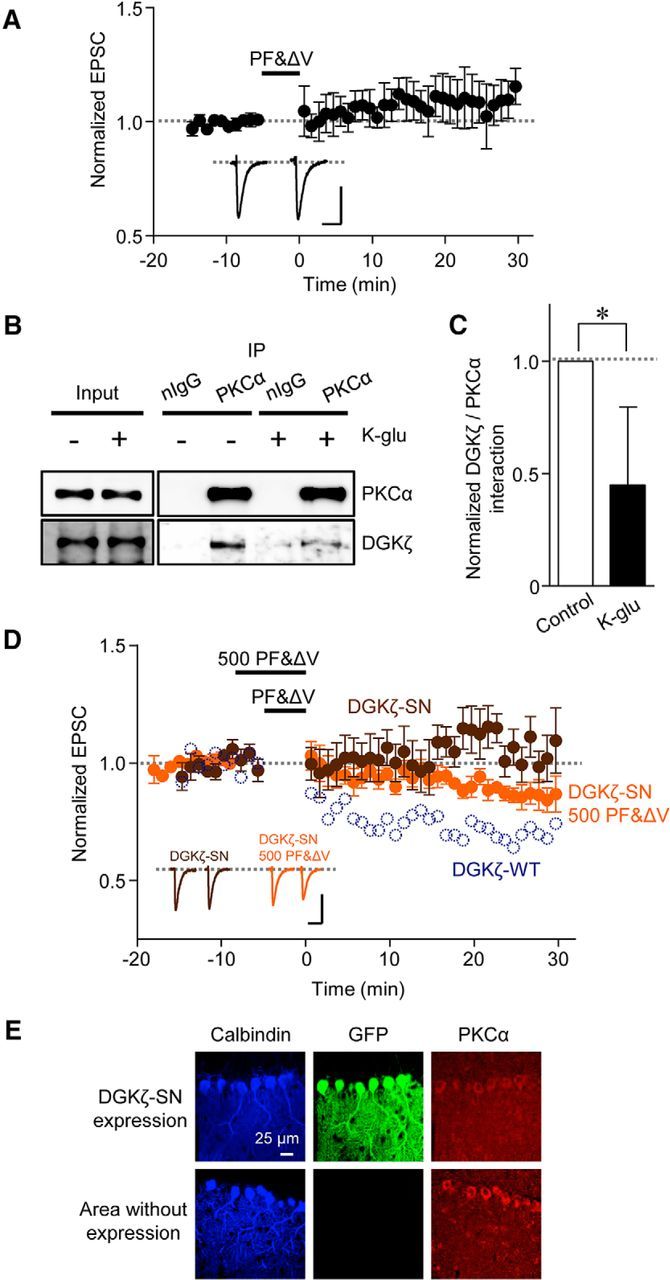

Activity-dependent dissociation of PKCα from DGKζ is required for LTD

A previous study proposed a model of the reciprocal regulation of DGKζ by PKCα (Luo et al., 2003b): activated PKCα phosphorylates DGKζ, the phosphorylation of DGKζ results in the dissociation of PKCα from DGKζ, and the dissociation allows PKCα to remain active without being suppressed by DGKζ. Because PKCα activation is critical for LTD, it is possible that such reciprocal regulation occurs during LTD. We tested this possibility by two experiments. First, we performed immunoprecipitation analysis using lysates from cerebellar slices to examine the interaction between PKCα and DGKζ in the cerebellum. For this analysis, chemical LTD stimulation with K-glu was used to induce LTD in cerebellar slices. We previously showed that K-glu treatment for 5 min indeed induced LTD (Tanaka and Augustine, 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2012), and further confirmed that the preincubation of slices with K-glu occluded PF&ΔV-evoked LTD because LTD was not induced in slices pretreated with K-glu for 5 min (Fig. 7A, −8.93 ± 9.5%, n = 4; p < 0.01 compared with LTD in DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells shown in Fig. 2F, Student's t test). In the control cerebellar slices that were incubated in normal ACSF, PKCα was immunoprecipitated by the PKCα antibody. We then found that a substantial amount of DGKζ was coimmunoprecipitated by this antibody in the control slices, whereas much less was immunoprecipitated by normal IgG (Fig. 7B), indicating the interaction of PKCα with DGKζ in the cerebellum. Compared with the control slices, the amounts of coimmunoprecipitated DGKζ were reduced following treatment of the slices with chemical LTD stimulation with K-glu (Fig. 7B). To quantify the interaction of DGKζ with PKCα, the ratio of band intensities of DGKζ and PKCα was calculated. We found that the ratio was significantly smaller in K-glu-treated samples than the control samples (Fig. 7C, p < 0.05, Student's t test). These results indicate that PKCα is dissociated from DGKζ after LTD stimulation.

Figure 7.

Activity-dependent dissociation of DGKζ and PKCα is necessary for LTD. A, Inhibition of PF&ΔV-evoked LTD by preincubation of DGKζ+/+ cerebellar slices with K-glu for 5 min (n = 4). PF&ΔV stimulation was applied at ∼30 min after the end of K-glu treatment. B, Immunoblotting of coimmunoprecipitated DGKζ and precipitated PKCα in DGKζ+/+ cerebellar slices treated with or without K-glu. Normal IgG (nIgG) was used as a control. C, Ratio of the signal of coimmunoprecipitated DGKζ to the signal of precipitated PKCα (n = 5). *Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05, Student's t test). D, Time course of LTD induced by PF&ΔV (1 Hz, 300×, brown circles, n = 7) or 500 PF&ΔV (1 Hz, 500 times, orange circles, n = 6) in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-SN. For comparison, the time course of LTD in Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-WT shown in Figure 6B is overlaid (dark blue dotted circles). E, Images of a cerebellar slice from a DGKζ−/− mouse expressing GFP-DGKζ-SN. The slice was double stained with antibodies against calbindin and PKCα. For comparison, images of an area of the same slice, in which GFP expression was not observed, are also shown.

Second, to test whether the reciprocal regulation of DGKζ by PKCα is necessary for LTD, we performed rescue experiments using a mutant form of DGKζ, in which four serine residues were replaced with asparagine residues (DGKζ-SN). It was reported that DGKζ-SN maintained its kinase activity and that the interaction of PKCα with DGKζ-SN was not affected by the activation or inhibition of PKCα (Luo et al., 2003b), so that DGKζ-SN was considered as a mutant that does not receive reciprocal regulation by PKCα. As with DGKζ-WT and DGKζ-KD, an AAV vector expressing DGKζ-SN was injected into the DGKζ−/− cerebellum. We found that the expression of DGKζ-SN in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells failed to restore LTD (Fig. 7D). The depression of PF-EPSC in cells expressing DGKζ-SN (−6.8 ± 7.6%, n = 7) was significantly smaller than that in cells expressing DGKζ-WT (p < 0.05, Tukey test). Similar to the case of DGKζ-KD, changes of PKCα distribution in DGKζ−/− slices expressing DGKζ-SN were analyzed (Fig. 7E). The ratio of PKCα staining in the molecular layer to that in soma in DGKζ−/− slices expressing DGKζ-SN (0.71 ± 0.02, n = 19) was significantly increased compared with the ratio in DGKζ−/− slices expressing GFP alone (p < 0.05, Bonferroni test), suggesting that the failure to restore LTD by DGKζ-SN expression is not due to the mislocalization of PKCα. Finally, because the failure of DGKζ-SN to restore LTD may be overcome by a stimulation that strongly activates PKCα, even without the reciprocal regulation of DGKζ-SN by PKCα, we tested whether a longer duration (500 s) of pairing PF stimulation with Purkinje cell depolarization (500 PF&ΔV) could trigger LTD in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-SN. Although LTD was not clearly induced by 500 PF&ΔV, there was a tendency of slight depression (Fig. 7D; 12.3 ± 4.2%, n = 6). No significant difference was detected upon comparison with both cases, in which a 300 s duration of PF&ΔV induced or did not induce LTD in cells expressing DGKζ-WT (p = 0.17, Tukey test) or DGKζ-SN (p = 0.093, Tukey test), respectively. Thus, small amounts of LTD may have been induced by stronger PKCα activation following 500 PF&ΔV in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells expressing DGKζ-SN. Together with the results of immunoprecipitation analysis, we conclude that the reciprocal regulation of DGKζ by PKCα, which presumably leads to the dissociation of PKCα from DGKζ and consequently to further PKCα activation, is required for LTD induction.

Discussion

PKC has been established to be necessary and even sufficient for cerebellar LTD (Linden and Connor, 1991; Hartell, 1994; De Zeeuw et al., 1998; Endo and Launey, 2003; Kondo et al., 2005); hence, the precise regulation of PKC is critical for synaptic functions. We investigated the role of DGKζ, which was shown to physically and functionally interact with PKCα, in the regulation of LTD. The present study demonstrated several results indicating that DGKζ indeed regulates PKCα and consequently LTD: (1) LTD is impaired in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells; (2) PKCα is less localized in the dendrites and synapses of DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells compared with DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells, and targeting of DGKζ to synapses is required for LTD; (3) the kinase activity of DGKζ is involved in LTD; and (4) the binding between PKCα and DGKζ is reduced upon LTD stimulation, and the inverse regulation from PKCα to DGKζ, which presumably leads to the dissociation of PKCα from DGKζ, is required for LTD. Together, our study revealed the importance of DGKζ in cerebellar LTD, and further presented the underlying mechanisms of the regulation by DGKζ of the localization and activity of PKCα that is required for LTD.

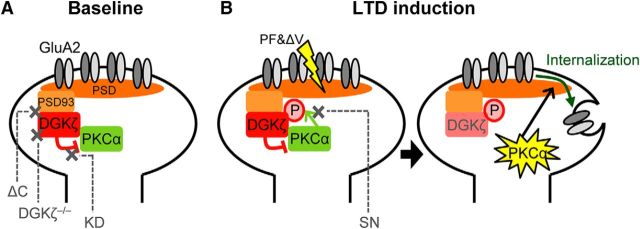

Mutual regulation of PKCα and DGKζ is required for cerebellar LTD

Based on the results of this study, we propose a model as to how DGKζ controls PKCα in terms of synaptic regulation in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Fig. 8). Results showing the mislocalization of PKCα in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells indicate that DGKζ works to place PKCα in its correct position. Because DGKζ can interact with PKCα and the targeting of DGKζ to synapses is required for LTD, DGKζ-dependent anchoring of PKCα at synapses is likely to be a function of DGKζ that is required for LTD. In addition to its anchoring function, the kinase activity of DGKζ is also required for LTD, based on the results showing that DGKζ-KD could not restore LTD. Although it is not entirely clear as to how the kinase activity of DGKζ is involved in LTD, considering that DGKζ metabolizes DAG, leading to a decrease in PKCα activity, and that an increase rather than a decrease in PKCα activity mediates LTD, one possibility is that the reduction of PKCα activity by DGKζ works at the basal state. Thus, the anchoring function, as well as the kinase activity of DGKζ for PKCα, appears to prepare synapses to respond to the synaptic stimulation that triggers LTD. Furthermore, our results using DGKζ-SN indicate that the functions of DGKζ in anchoring PKCα to synapses and in reducing PKCα activity are not sufficient, and that the inverse regulation from PKCα to DGKζ and the following dissociation of PKCα are required for LTD. Indeed, our immunoprecipitation analysis showed that PKCα was dissociated from DGKζ upon LTD stimulation. The requirement of this inverse regulation also supports the idea that the kinase activity of DGKζ is required for reducing PKCα activity at the basal state. Thus, PKCα activity is maintained at a reduced level around synapses by DGKζ in the basal state (Fig. 8A), but synaptic stimulation triggering LTD activates PKCα through Ca2+ and DAG production, and the activated PKCα phosphorylates DGKζ and is released from DGKζ, so that PKCα can effectively trigger LTD by enhancing AMPAR internalization (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Proposed model of the role of DGKζ in the regulation of PKCα activity and LTD at baseline (A) and after LTD induction (B). The affected proteins/functions in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells, with or without the expression of mutant forms of DGKζ, namely, DGKζ-ΔC (ΔC), DGKζ-KD (KD), or DGKζ-SN (SN), are indicated by crosses.

Unlike other isoforms of PKC, PKCα has a unique PDZ ligand motif in its C terminus, and this PDZ ligand motif is critical for the function of PKCα in LTD (Leitges et al., 2004). The PDZ ligand motif in PKCα is responsible for its interaction with PICK1 (Staudinger et al., 1997). Furthermore, the interaction of PICK1 with GluA2 AMPARs after PKC-dependent GluA2 phosphorylation is required for the internalization of AMPARs during LTD (Steinberg et al., 2006). These reports suggest that the requirement of the PDZ ligand motif in PKCα for LTD arises from its interaction with PICK1 (Leitges et al., 2004). In the present study, we showed that the interaction between DGKζ and PKCα relies on the PDZ ligand motif in PKCα (Fig. 4C), raising the possibility that this motif is critical for LTD, also because of its interaction with DGKζ. Because PICK1 interacts with PKCα only in the activated state (Perez et al., 2001), whereas DGKζ interacts with PKCα in the inactivated state (Luo et al., 2003b), these two interacting partners of PKCα act cooperatively: DGKζ interacts with PKCα at the basal level to control the localization of and to reduce the activity of PKCα, but upon LTD stimulation, PKCα is released from DGKζ and PICK1 interacts with PKCα to perform further reactions required for LTD. This idea could be verified by investigating the presence of three molecules in the same synaptic signaling clusters and analyzing the mechanisms causing the switch of PKCα-interacting partners during LTD. The former would be supported by our results showing that all three proteins were concentrated in the P2 fraction of DGKζ+/+ cerebella (Fig. 5D). The mechanisms involved in the switch of interaction partners are not clear but may involve an increased binding affinity of PKCα with an active conformation to PICK1 (Leonard et al., 2011; Erlendsson et al., 2014), and a decreased binding affinity of PKCα to phosphorylated DGKζ.

Our immunoblotting analysis using synaptosomes demonstrated that the synaptic localization of PKCα relies on DGKζ. In addition, our immunohistochemical analysis showing less PKCα localization at dendrites in DGKζ−/− Purkinje cells compared with DGKζ+/+ Purkinje cells indicated that the dendritic localization of PKCα is also affected by DGKζ. Because PSD-93 is distributed throughout soma and dendrites of Purkinje cells (Brenman et al., 1996; McGee et al., 2001), DGKζ may also interact with PSD-93 in soma or dendrites. Alternatively, many DGKζ-interacting partners have been identified (Rincón et al., 2012), and these proteins may determine the dendritic localization of DGKζ and PKCα. Studies regarding DGKζ-interacting partners support the concept that DGKζ works as a component in protein complexes, where lipid-metabolizing enzymes and lipid effectors act together to coordinate lipid signaling in a local area (Rincón et al., 2012). The present result showing that DGKζ functions to target and regulate PKCα around synapses for cerebellar LTD is in line with this concept.

Regulation of synaptic plasticity by DGKζ in Purkinje cells and hippocampal pyramidal cells

It has been shown previously that DGKζ regulates synaptic plasticity in Schaffer collateral-CA1 pyramidal (SC-CA1) synapses in the hippocampus (Seo et al., 2012). In these synapses of DGKζ−/− mice, LTP is enhanced but LTD is attenuated because of an abnormally increased level of DAG and the subsequent enhancement of PKC activity. In contrast, our results showed that LTD is impaired in PF-Purkinje cell synapses of DGKζ−/−, and yet LTP is intact, indicating that DGKζ specifically contributes to LTD. Many factors may be involved in creating the differences of DGKζ function in the regulation of synaptic plasticity between these two types of synapses. One factor may be the way in which DAG-related molecules, phospholipase C (PLC) and PKC, are involved in synaptic plasticity. Given that inhibitors of PLC or PKC did not affect LTP and LTD in wild-type SC-CA1 synapses (Seo et al., 2012), PLC and PKC in SC-CA1 synapses can be considered as “modulators,” which are molecules modulating the ability to trigger synaptic plasticity or playing a permissive role (Citri and Malenka, 2008). On the other hand, PLC and PKC working in cerebellar LTD are considered as “mediators,” which are directly responsible for triggering synaptic plasticity (Citri and Malenka, 2008). DGKζ-regulating modulators may arrange overall synaptic conditions in SC-CA1 synapses, whereas DGKζ-regulating mediators may directly regulate LTD of PF-Purkinje cell synapses. Even though the machinery involving DGKζ is different, DGKζ deficiency affects synaptic plasticity in both types of synapses, suggesting the general importance of DAG-related molecules and their regulation by DGKζ for coordinating synaptic plasticity.

Balance between positive and negative regulators working for cerebellar LTD

Synaptic plasticity is generally triggered by the strong stimulation of synapses, in which many signaling molecules are involved and activated. LTD at PF-Purkinje cell synapses in the cerebellum is mediated by a positive feedback kinase loop (Kuroda et al., 2001; Tanaka and Augustine, 2008; Le et al., 2010), which is an effective mechanism to enhance the amplitude or timing of activation upon stimulation, but also might be problematic for the control of specificity. Therefore, negative regulators, such as phosphatases, are included in the theoretical model (Kuroda et al., 2001). Indeed, the reduction of phosphatase activity was implicated in LTD (Launey et al., 2004). We previously demonstrated that another inhibitory molecule, Raf-kinase inhibitory protein, was involved in regulating the PKC-dependent activation of the MAPK pathway for LTD (Yamamoto et al., 2012). In addition, PTPRR, a MAPK-specific tyrosine phosphatase, was recently shown to act to maintain low basal MAPK activity and to create an optimal window to boost MAPK activity upon LTD stimulation (Erkens et al., 2015). In the present study, we found that DGKζ is involved in LTD by its anchoring function that positively regulates PKCα localization, by its kinase function that negatively regulates PKCα activity, and by its ability to receive inverse regulation from activated PKCα to release PKCα. Similar functional and physical interactions may work to achieve the local and fine activation of signaling molecules required for synaptic plasticity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the World Class Institute (WCI) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of Korea (NRF Grant WCI 2009-003), Japan Science and Technology Agency PRESTO Grant, Korea Institute of Science and Technology Institutional Program Project 2E25540, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Research Foundation for Opto-Science and Technology, NRF of Korea Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of Korea NRF Grant 20110007460, and Institute for Basic Science IBS-R002-D1. We thank Dr. George J. Augustine for valuable comments on this paper; Yoonhee Kim and Begüm Aküzüm for technical assistance; and Dr. Karam Kim for helpful suggestions on experiments using DGKζ−/− mice.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Baumgärtel K, Mansuy IM. Neural functions of calcineurin in synaptic plasticity and memory. Learn Mem. 2012;19:375–384. doi: 10.1101/lm.027201.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmeguenai A, Hansel C. A role for protein phosphatases 1, 2A, and 2B in cerebellar long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10768–10772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2876-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenman JE, Christopherson KS, Craven SE, McGee AW, Bredt DS. Cloning and characterization of postsynaptic density 93, a nitric oxide synthase interacting protein. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7407–7415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07407.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Abramovici H, Gee SH, Topham MK. Diacylglycerol kinases as sources of phosphatidic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coesmans M, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron. 2004;44:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C, Bian F, Koekkoek SK, van Alphen AM, Linden DJ, Oberdick J. Expression of a protein kinase C inhibitor in Purkinje cells blocks cerebellar LTD and adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Neuron. 1998;20:495–508. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S, Launey T. ERKs regulate PKC-dependent synaptic depression and declustering of glutamate receptors in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:863–872. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkens M, Tanaka-Yamamoto K, Cheron G, Márquez-Ruiz J, Prigogine C, Schepens JT, Nadif Kasri N, Augustine GJ, Hendriks WJ. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type R is required for Purkinje cell responsiveness in cerebellar long-term depression. Mol Brain. 2015;8:1. doi: 10.1186/s13041-014-0092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlendsson S, Rathje M, Heidarsson PO, Poulsen FM, Madsen KL, Teilum K, Gether U. Protein interacting with C-kinase 1 (PICK1) binding promiscuity relies on unconventional PSD-95/discs-large/ZO-1 homology (PDZ) binding modes for nonclass II PDZ ligands. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:25327–25340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.548743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch EA, Tanaka K, Augustine GJ. Calcium as a trigger for cerebellar long-term synaptic depression. Cerebellum. 2012;11:706–717. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K, Muller D, Ohmitsu M, Bakó E, DePaoli-Roach AA, Miyamoto E. Decreased protein phosphatase 2A activity in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurochem. 2000;74:807–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlfinger A, Kapfhammer JP, Kruse F, Leitges M, Metzger F. Different regulation of Purkinje cell dendritic development in cerebellar slice cultures by protein kinase Cα and β. J Neurobiol. 2003;57:95–109. doi: 10.1002/neu.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa H, Kelly PF, Nathwani AC, Persons DA, Vandergriff JA, Hargrove P, Vanin EF, Nienhuis AW. Comparison of various envelope proteins for their ability to pseudotype lentiviral vectors and transduce primitive hematopoietic cells from human blood. Mol Ther. 2002;5:242–251. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartell NA. cGMP acts within cerebellar Purkinje cells to produce long term depression via mechanisms involving PKC and PKG. Neuroreport. 1994;5:833–836. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199403000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann J, Dragicevic E, Adelsberger H, Henning HA, Sumser M, Abramowitz J, Blum R, Dietrich A, Freichel M, Flockerzi V, Birnbaumer L, Konnerth A. TRPC3 channels are required for synaptic transmission and motor coordination. Neuron. 2008;59:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. Long-term depression and other synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2013;89:183–195. doi: 10.2183/pjab.89.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi Y, Ito T, Nakano T, Nakagawa T, Aoyagi M, Kondo H, Goto K. Nuclear localization of diacylglycerol kinase ζ in neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1448–1457. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huganir RL, Nicoll RA. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: the last 25 years. Neuron. 2013;80:704–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. The molecular organization of cerebellar long-term depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:896–902. doi: 10.1038/nrn962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoutorsky A, Yanagiya A, Gkogkas CG, Fabian MR, Prager-Khoutorsky M, Cao R, Gamache K, Bouthiette F, Parsyan A, Sorge RE, Mogil JS, Nader K, Lacaille JC, Sonenberg N. Control of synaptic plasticity and memory via suppression of poly(A)-binding protein. Neuron. 2013;78:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Yang J, Zhong XP, Kim MH, Kim YS, Lee HW, Han S, Choi J, Han K, Seo J, Prescott SM, Topham MK, Bae YC, Koretzky G, Choi SY, Kim E. Synaptic removal of diacylglycerol by DGKζ and PSD-95 regulates dendritic spine maintenance. EMBO J. 2009;28:1170–1179. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Yang J, Kim E. Diacylglycerol kinases in the regulation of dendritic spines. J Neurochem. 2010;112:577–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Choi J, Yang J, Chung W, Kim JH, Paik SK, Kim K, Han S, Won H, Bae YS, Cho SH, Seo J, Bae YC, Choi SY, Kim E. Enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission, enhanced long-term potentiation, and impaired learning and memory in mice lacking IRSp53. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1586–1595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4306-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Tanaka-Yamamoto K. Mechanisms producing time course of cerebellar long-term depression. Neural Netw. 2013;47:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Kim T, Rhee JK, Lee D, Tanaka-Yamamoto K, Yamamoto Y. Selective transgene expression in cerebellar Purkinje cells and granule cells using adeno-associated viruses together with specific promoters. Brain Res. 2015;1620:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda K, Kakegawa W, Matsuda S, Yamamoto T, Hirano H, Yuzaki M. The δ2 glutamate receptor gates long-term depression by coordinating interactions between two AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E948–E957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218380110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Kakegawa W, Yuzaki M. Induction of long-term depression and phosphorylation of the δ2 glutamate receptor by protein kinase C in cerebellar slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1817–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda S, Schweighofer N, Kawato M. Exploration of signal transduction pathways in cerebellar long-term depression by kinetic simulation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05693.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launey T, Endo S, Sakai R, Harano J, Ito M. Protein phosphatase 2A inhibition induces cerebellar long-term depression and declustering of synaptic AMPA receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:676–681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0302914101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TD, Shirai Y, Okamoto T, Tatsukawa T, Nagao S, Shimizu T, Ito M. Lipid signaling in cytosolic phospholipase A2α-cyclooxygenase-2 cascade mediates cerebellar long-term depression and motor learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3198–3203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitges M, Kovac J, Plomann M, Linden DJ. A unique PDZ ligand in PKCα confers induction of cerebellar long-term synaptic depression. Neuron. 2004;44:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard TA, Różycki B, Saidi LF, Hummer G, Hurley JH. Crystal structure and allosteric activation of protein kinase C βII. Cell. 2011;144:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ram V, Wong ST, Storm DR, Tsien RY. A new form of cerebellar long-term potentiation is postsynaptic and depends on nitric oxide but not cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8389–8393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122206399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DJ, Connor JA. Participation of postsynaptic PKC in cerebellar long-term depression in culture. Science. 1991;254:1656–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.1721243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Prescott SM, Topham MK. Protein kinase C alpha phosphorylates and negatively regulates diacylglycerol kinase zeta. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:39542–39547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Prescott SM, Topham MK. Association of diacylglycerol kinase zeta with protein kinase C alpha: spatial regulation of diacylglycerol signaling. J Cell Biol. 2003b;160:929–937. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee AW, Topinka JR, Hashimoto K, Petralia RS, Kakizawa S, Kauer FW, Aguilera-Moreno A, Wenthold RJ, Kano M, Bredt DS, Kauer F. PSD-93 knock-out mice reveal that neuronal MAGUKs are not required for development or function of parallel fiber synapses in cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3085–3091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03085.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata M, Finch EA, Khiroug L, Hashimoto K, Hayasaka S, Oda SI, Inouye M, Takagishi Y, Augustine GJ, Kano M. Local calcium release in dendritic spines required for long-term synaptic depression. Neuron. 2000;28:233–244. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JL, Khatri L, Chang C, Srivastava S, Osten P, Ziff EB. PICK1 targets activated protein kinase Cα to AMPA receptor clusters in spines of hippocampal neurons and reduces surface levels of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5417–5428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05417.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón E, Gharbi SI, Santos-Mendoza T, Mérida I. Diacylglycerol kinase zeta: at the crossroads of lipid signaling and protein complex organization. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Shome K, Vasudevan C, Stolz DB, Sung TC, Frohman MA, Watkins SC, Romero G. Phospholipase D and its product, phosphatidic acid, mediate agonist-dependent raf-1 translocation to the plasma membrane and the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1131–1139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Shome K, Watkins SC, Romero G. The recruitment of Raf-1 to membranes is mediated by direct interaction with phosphatidic acid and is independent of association with Ras. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23911–23918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakane F, Imai S, Kai M, Yasuda S, Kanoh H. Diacylglycerol kinases: why so many of them? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J, Kim K, Jang S, Han S, Choi SY, Kim E. Regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation and long-term depression by diacylglycerol kinase zeta. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1018–1026. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger J, Lu J, Olson EN. Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C-α. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32019–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Shen Y, Xia J, Rubio ME, Yu S, Jin W, Thomas GM, Linden DJ, Huganir RL. Targeted in vivo mutations of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 and its interacting protein PICK1 eliminate cerebellar long-term depression. Neuron. 2006;49:845–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takács J, Gombos G, Görcs T, Becker T, de Barry J, Hämori J. Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1a in Purkinje cell dendritic spines is independent of the presence of presynaptic parallel fibers. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:433–442. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971101)50:3<433::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Augustine GJ. A positive feedback signal transduction loop determines timing of cerebellar long-term depression. Neuron. 2008;59:608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torashima T, Okoyama S, Nishizaki T, Hirai H. In vivo transduction of murine cerebellar Purkinje cells by HIV-derived lentiviral vectors. Brain Res. 2006;1082:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Khiroug L, Augustine GJ. Quantification of spread of cerebellar long-term depression with chemical two-photon uncaging of glutamate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8635–8640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130414597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Lee D, Kim Y, Lee B, Seo C, Kawasaki H, Kuroda S, Tanaka-Yamamoto K. Raf kinase inhibitory protein is required for cerebellar long-term synaptic depression by mediating PKC-dependent MAPK activation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14254–14264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2812-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, Miura E, Kamiya H, Kano M, Watanabe M. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-α around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol, and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4740–4751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XP, Hainey EA, Olenchock BA, Jordan MS, Maltzman JS, Nichols KE, Shen H, Koretzky GA. Enhanced T cell responses due to diacylglycerol kinase ζ deficiency. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:882–890. doi: 10.1038/ni958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]