Abstract

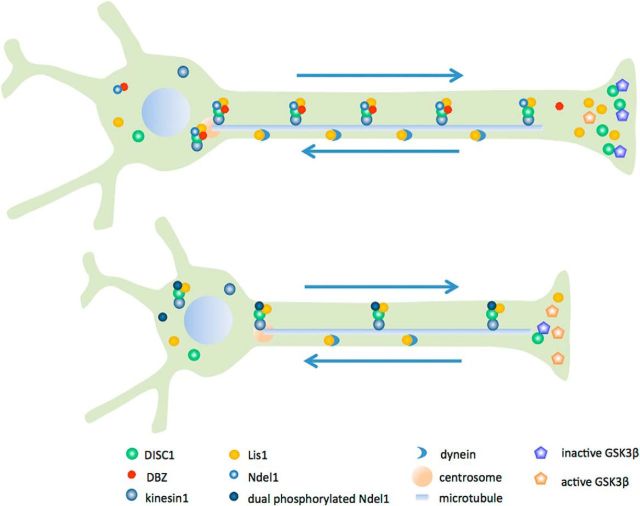

Cell positioning and neuronal network formation are crucial for proper brain function. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) is anterogradely transported to the neurite tips, together with Lis1, and functions in neurite extension via suppression of GSK3β activity. Then, transported Lis1 is retrogradely transported and functions in cell migration. Here, we show that DISC1-binding zinc finger protein (DBZ), together with DISC1, regulates mouse cortical cell positioning and neurite development in vivo. DBZ hindered Ndel1 phosphorylation at threonine 219 and serine 251. DBZ depletion or expression of a double-phosphorylated mimetic form of Ndel1 impaired the transport of Lis1 and DISC1 to the neurite tips and hampered microtubule elongation. Moreover, application of DISC1 or a GSK3β inhibitor rescued the impairments caused by DBZ insufficiency or double-phosphorylated Ndel1 expression. We concluded that DBZ controls cell positioning and neurite development by interfering with Ndel1 from disproportionate phosphorylation, which is critical for appropriate anterograde transport of the DISC1-complex.

Keywords: anterograde transport, cortical development, microtubule, migration, neurite extension

Introduction

Radially and horizontally migrating neurons are the primary source of the neocortical neurons (Rakic, 1990; Bayer and Altman, 1991; Noctor et al., 2004; Marín et al., 2010). Impaired neuron migration increases vulnerability to neurological and/or psychiatric disorders (Walsh et al., 2008; Brandon and Sawa, 2011; Poduri et al., 2013). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. The neurodevelopmentally regulated scaffold protein Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) has attracted much attention because DISC1 is a promising candidate gene for major mental illnesses (Hodgkinson et al., 2004; Cannon et al., 2005; Weinberger, 2005; Chubb et al., 2008). Although DISC1 is versatile, the critical role of DISC1 in cortical development has been demonstrated. An acute insufficiency of DISC1 activity induced by RNAi results in impaired radial migration, the mechanism by which most excitatory neurons are arranged, and mice with such distorted brain structures exhibit abnormal behavior (Kamiya et al., 2005; Niwa et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2010; Ishizuka et al., 2011). By contrast, the importance of DISC1 in vivo remains controversial because no obvious cortical impairment has been observed in DISC1 knock-out mice thus far (Kuroda et al., 2011).

To elucidate the functional relevance of DISC1, several groups have identified molecules that work together with DISC1, such as Ndel1, Lis1 and Fez1 (Miyoshi et al., 2003; Ozeki et al., 2003; Ishizuka et al., 2006; Mackie et al., 2007; Taya et al., 2007; Brandon et al., 2009; Brandon and Sawa, 2011). DISC1-binding zinc finger protein (DBZ; alternatively referred to as ZNF365, KIAA0844 or Su48) is one such molecule that has a predicted C2H2-type zinc-finger motif and coiled-coil domains (Gianfrancesco et al., 2003; Hattori et al., 2007). Su48 has been identified as a centrosome protein essential for cell division. Excessive expression of the DBZ/Su48 deletion mutant in vitro sequesters γ-tubulin into the cytosol and prevents it from binding to the centrosome (Hirohashi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006).

DBZ mRNA expression is limited in the brain. An in situ hybridization study of the adult rat brain revealed robust expression of DBZ mRNA in the forebrain, particularly in the cortex and the hippocampus (Hattori et al., 2007); however, the importance of DBZ in mammals in vivo has not been fully elucidated. Overexpression of both DBZ and DISC1 results in a significant decrease in the number of neurite-bearing PC12 cells, whereas overexpression of either DBZ or DISC1 alone does not alter the number of neurite-bearing PC12 cells. Furthermore, neurite outgrowth is inhibited by the overexpression of the DISC1-binding domain of DBZ (DBZ 152–301) in PC12 cells and primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons (Hattori et al., 2007), as well as in basket cells of the DBZ-deficient mouse cortex (Koyama et al., 2013). The further importance and underlying mechanisms of DBZ activity have not been addressed. In the present study, we used our recently generated DBZ knock-out mice (Koyama et al., 2013) to investigate how DBZ exerts its effects, particularly through Ndel1, Lis1 and DISC1.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Pregnant C57BL/6 mice were used. Embryonic day (E)0.5 was defined as the day of confirmation of a vaginal plug. All pregnant animals were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg). All experiments were conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals of the University of Fukui or Osaka University and approved by their animal ethics committees. All possible efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-GAPDH (sc-32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GFP that can recognize enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) for Western blotting (no. 632377; BD Biosciences; sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and for immunoprecipitation (no. 598, MBL), anti-HA for Western blotting (sc-805, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and for immunocytochemistry (HA.11 clone16B12, Covance), anti-myc (sc-40, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FLAG (M2; F3165, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-βIII-tubulin (Tuj1, a gift from Dr A. Frankfurter, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA), anti-tyrosinated tubulin (MAB1864, Millipore), anti-Cux1 (sc-13024; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Tbr1 (AB2261; Millipore), anti-Ki67 (clone SP6, Thermo Fisher Scientific Lab Vision), anti-BrdU (CldU; no. 0109; AbD Serotec), and anti-BrdU (IdU; no. 69138; BD Biosciences). AlexaFluor 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (A11001, A11034, A11031, A11036, A11077, Invitrogen) were also used. We generated anti-pT219 Ndel1, anti-pS251 Ndel1, anti-Lis1, anti-DISC1 (Hattori et al., 2007), and anti-DBZ antibodies.

Generation of anti-DBZ rat monoclonal antibody.

Generation of the anti-DBZ rat monoclonal antibody was based on the rat lymph node method established by Kishiro et al. (1995). A 10-week-old female WKY/Izm rat (SLC) was injected in the hind footpads with 200 μl of an emulsion containing 350 μg of KLH-DBZ peptide (SPREFFRPAKKGEHLGLSRKGNFRPKMAK KKPTAIVNII; Sigma-Aldrich) and Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories). After 6 weeks, the cells from the medial iliac lymph nodes of the rat immunized with the antigen were fused with mouse myeloma SP2/W cells at a ratio of 5:1 in a 50% polyethylene glycol solution (PEG 1500, Roche Applied Science). The resulting hybridoma cells were plated into 96-well plates and cultured in HAT selection medium (Hybridoma-SFM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 ng/ml recombinant human IL-6 (R&D Systems), 100 mm hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.4 mm aminopterin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 16 mm thymidine (Sigma-Aldrich). At 6 d postfusion, the hybridoma supernatants were screened using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay against the BSA-DBZ peptide. Positive clones were subcloned and rescreened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and by Western blotting. The specificity of our antibody was confirmed and described in our related manuscript (Koyama et al., 2013).

In situ hybridization.

A cDNA fragment of mouse DBZ was amplified by RT-PCR [the oligonucleotide primers were 5′-CTTTGCGCAGCTGACTCAGAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTCAGCACTGCGATCATTTCC-3′ (antisense) for mouse DBZ] and used as a template for probe synthesis. In situ hybridization was performed with sagittal or coronal mouse brain sections with 35S-labeled RNA probes as described previously (Koyama et al., 2008).

Nissl staining.

Paraffin-embedded brain tissue sections (7 μm) were deparaffinized and placed in 0.5% cresyl violet in water at 37°C for 10 min. The sections were briefly rinsed twice in 90% ethanol and dipped in 100% ethanol three times before being dehydrated in xylene three times for 5 min each. The sections were affixed to glass coverslips using Permount solution (Fisher Scientific) and examined under a light microscope.

Bodian's staining.

Sections (7 μm) were deparaffinized and hydrated in water. The sections were then incubated in 1% protargol solution (Polysciences) for 24 h at 37°C. After being rinsed in water, the sections were placed in a reducing solution (1% hydroquinone) for 5 min and then washed in water. The sections were then rinsed in 1% gold chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) in water for 10 min, followed by several rinses with water. The sections were incubated in 0.5% oxalic acid in water for 10 min and fixed with 5% sodium thiosulfate for 3 min. Subsequently, the sections were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted with Entellan (Merck).

Morphological analyses of Golgi-cox stained neurons.

Four animals each of the DBZ+/+ and the DBZ−/− mice were studied at postnatal day (P)3. Rapid Golgi staining was performed on 250-μm-thick sections using an FD Rapid GolgiStain Kit (FD NeuroTechnologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bright-field microscopic images of pyramidal neurons in layer V of the cerebral cortices were obtained using a BZ-9000 fluorescence microscope (Keyence). Cells that fulfilled the following criteria were randomly chosen for analyses: (1) the cell body and extending dendrites were completely impregnated, (2) the cell was isolated from surrounding impregnated cells, and (3) the cell body was in layer V of the cerebral cortex. ImageJ software (NIH) was used to measure the width of the apical dendrite and the number of total branch points in the primary apical dendrite. Dendrite width was measured at the region where the apical dendrite arose from the soma. Forty-five cells from the DBZ+/+ mice and the littermate DBZ−/− mice were selected and measured.

Birth-date analysis.

Pregnant mice were injected with a single dose of CldU (50 μg/kg, 105478, MP Biomedicals) at E13.5 and IdU (50 μg/kg, 17125, Sigma-Aldrich) at E16.5. The embryos were collected at P2. Labeled cells represented the neurons that underwent the final S-phase at the time of CldU/IdU injection. On coronal sections, the entire cortical thickness was subdivided equally into ten 100-μm-wide fractions (Bins 1–10). CldU- and IdU-positive cells were counted, and the percentage of these cells relative to all cells (stained with Hoechst) was calculated for each fraction as described previously (Komada et al., 2008). This percentage was calculated as follows: (CldU- or IdU-positive cell number/Hoechst-stained cell number) × 100.

Vectors.

For protein expression, plasmid vectors constructed using the pCAGGS vector (Niwa et al., 1991) were used so that the cDNAs were driven under a CAG promoter. We previously constructed a pcDNA3.1(+) expression vector (Invitrogen) carrying the full-length human DISC1 cDNA with the HA epitope sequence (DISC1-HA). In the present study, DISC1-HA was subcloned into the pCAGGS vector (pCAGGS DISC1-HA, hereafter designated DISC1-HA). The full-length mouse DISC1 cDNA was cloned into the pCAGGS EGFP vector to generate DISC1 with EGFP fused to the C-terminus (pCAGGS mouse DISC1-EGFP, hereafter designated mDISC1-EGFP). The full-length human DBZ cDNA encoding 407 aa was subcloned into the pCAGGS EGFP vector to generate DBZ with EGFP fused to the N-terminus (pCAGGS EGFP-human DBZ; hereafter designated hDBZ). The full-length mouse DBZ cDNA was also subcloned into the pCAGGS EGFP vector to generate pCAGGS EGFP-mouse DBZ (hereafter designated mDBZ). The full-length human Ndel1 cDNA was subcloned into the pCAGGS myc-FLAG IRES GFP vector. The N-terminal region of Ndel1cDNA and the C-terminal region of the Ndel1 cDNA were also subcloned and used as pCAGGS myc-Ndel1-Nt (Ndel1-Nt, residues 1–205) and pCAGGS Ndel1-Ct-FLAG (Ndel1-Ct, residues 206–345), respectively. Point mutations in Ndel1 (T219E, T219A, S251E, S251A) were introduced using a mutagenesis kit (KOD-plus mutagenesis kit, TOYOBO). The pCAGGS EB3-EGFP vector was generated by subcloning the EB3-EGFP fragment of the Tα-LPL-EB3-EGFP vector (a gift from Dr A. Sakakibara, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan) into the pCAGGS-5MCS vector (a modified pCAGGS vector with multiple cloning sites) using the EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites. To visualize centrin2 in the centrosome, pEGFP-CETN2 was generated by modifying pCAGGS1-centrin2-EGFP (a gift from Dr Kubo, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, we generated pCAGGS DS-Red2 by inserting a DS-Red2 fragment (subcloned from the pDS-Red2 vector, Takara-Bio, Japan) into the pCAGGS vector. pCAGGS tdTomato was constructed and given to us by Dr Kuroda (Univiversity of Fukui, Fukui, Japan).

RNA interference.

For shRNA expression, plasmid vectors constructed using the mU6pro vector were used so that the shRNAs were expressed under a mouse U6 promoter. Three different constructs for mouse DBZ shRNAs were prepared in the mU6pro vector, which has a mouse U6 promoter. The targets of these shRNAs were the following nucleotides from mouse DBZ cDNA: RNAi no. 1: 5′-AGCGGACCCTCCTGACAAAATGC-3′; RNAi no. 2: 5′-AAGCAGTTGGAATATTATCAAAG-3′; and RNAi no. 3: 5′-CTGAGTCTCCAAGAGAATTCTTC-3′, which were termed DBZ-shRNA1, 2 and 3, respectively. We used DBZ-shRNA1 as the DBZ-RNAi (mU6pro DBZ-RNAi). Its scrambled sequence, 5′-GCCAGCCGAATTAGCGCACCTACA-3′, was used as the control RNAi (mU6 scramble). For cotransfection, a molar ratio of 1 (pCAGGS EGFP) to 1 (shRNA-expression plasmid or empty mock vector) was used. Mouse DISC1 shRNA was prepared in the mU6pro vector. The target was 5′-GGCAAACACTGTGAAGTGC-3′. An empty shRNA vector (mU6pro) was used as the empty mock vector.

In utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer and tissue preparation.

In utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer was performed essentially as described previously (Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001; Tabata and Nakajima, 2001; Xie et al., 2013). Briefly, pregnant mice were deeply anesthetized on E14.5, and the uterine horns were exposed. Plasmid DNA, purified using an EndoFree plasmid kit (Qiagen), was dissolved in PBS at a final concentration of 0.5–2.5 μg/μl together with Fast Green (final concentration 0.01%). For cotransfection, molar ratios of 1 (pCAGGS EGFP, pCAGGS DS-Red2 or pCAGGS tdTomato) to 3–6 (the other plasmids for cotransfection) were used. Approximately 2 μl of plasmid solution was injected into the lateral ventricle from outside the uteri with a glass micropipette (GD-1.5, Narishige). Then, each embryo in the uterus was placed between tweezer-type electrodes and electronic pulses (40 V; 50 ms duration) were injected, after which the uterus was placed back into the abdominal cavity to allow the embryos to continue normal development. The mixtures of plasmid solutions contained the following combinations: (1) pCAGGS EGFP + mU6pro, (2) pCAGGS EGFP + mU6pro scramble, (3) pCAGGS EGFP + mU6pro DBZ-RNAi, (4) pCAGGS EGFP + mU6pro DBZ-RNAi + pCAGGS EGFP-human DBZ, (5) pCAGGS DS-Red2 + pEGFP-CETN2 + mU6pro, (6) pCAGGS DS-Red2 + pEGFP-CETN2 + mU6pro DBZ-RNAi, (7) pCAGGS DS-Red2 + pEGFP-CETN2 + mU6pro DBZ-RNAi + pCAGGS EGFP-human DBZ, (8) pCAGGS DS-Red2 + pEGFP-CETN2 + pCAGGS DISC1-HA, (9) pCAGGS EGFP-mouse DBZ, (10) pCAGGS EGFP + pCAGGS DISC1-HA, (11) pCAGGS EGFP + mU6pro DBZ-RNAi + pCAGGS DISC1-HA, (12) pCAGGS myc-T219E:S251E Ndel1-FLAG-ires-EGFP, (13) pCAGGS myc-T219E:S251E Ndel1-FLAG-ires-EGFP + pCAGGS DISC1-HA, (14) pCAGGS tdTomato + pCAGGS myc, and (15) pCAGGS tdTomato + pCAGGS myc-T219E:S251E Ndel1. Nuclear staining was performed with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen).

Three or 4 d after electroporation (E17.5 or E18.5), the pregnant dams were killed, and the brains of the embryos were fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. To analyze cell shape and migration, 100 μm sections were cut using a microslicer (DTK-1000, DosakaEM). For immunohistochemical staining, 12–14 μm cryosections were prepared after the brains were immersed in 30% sucrose/0.1 m PBS until the brains sank. The sections at the neocortex with the lateral ventricle containing EGFP-expressing cells were imaged and analyzed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM5 PASCAL, Carl-Zeiss).

Cell culture and immunocytochemistry.

To observe an individual neuron, cortices were dissected out and dissociated with papain (Worthington) for 20 min, and neurons were plated on collagen-coated glass-bottom dishes. The neurons were grown for 2–4 d in culture media consisting of neuronal basal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and 0.2 mm l-glutamine. The neurons were then immunostained and analyzed. Some neurons were transfected with pCAGGS DISC1-HA before immunostaining. Neuro2A (N2a) cells were obtained from the Laboratory of Molecular Pharmacology, Institute of Medical, Phamaceutical and Health Sciences, Kanazawa University; they were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer for 15 min, permeabilized and blocked with 0.25% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min. The samples were then incubated with various antibodies, followed by incubation with the AlexaFluor 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). The images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer A1, Carl-Zeiss), and immunofluorescence intensity in the axon was scanned using ImageJ software.

Analyses of neuronal positioning.

To quantify neuronal migration in brain slices 3 or 4 d after in utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer, we identified the subregions (the ventricular zone, subventricular zone, intermediate zone, cortical plate, and marginal zone) of the cerebral cortex. Cortices were divided into 5 or 10 bins, and the cell bodies in each bin were counted.

Analyses of nucleus-centrosome coupling.

RNAi constructs, together with pCAGGS DS-Red2 and a centrosome marker, were introduced into embryos at E14.5 using in utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer. The molar ratio of pCAGGS DS-Red2, pEGFP-CETN2 and RNAi constructs introduced in this experiment was 1:1:1 (0.67 μg/μl). The molar ratio of pCAGGS DS-Red2, pEGFP-CETN2, HA-DISC1, and RNAi constructs introduced in this experiment was 1:1:1:1 (0.5 μg/μl). In some cases, pCAGGS DS-Red2, pEGFP-CETN2, and HA-DISC1 were introduced. At E17.5, the developing cerebral cortices were coronally sectioned using a cryostat at 14 μm. The centrosomes and nuclei were labeled with pEGFP-CETN2 and Hoechst, respectively. Images of neurons in the intermediate zone were randomly acquired using confocal microscopes (LSM5 PASCAL, Carl-Zeiss).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting analyses.

Immunoprecipitation was performed with protein-G Sepharose (GE Healthcare) or Dynabeads protein-G (Life Technologies). Immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-DBZ antibody for lysates of whole mouse brains at E14.5, E17.5, P0, and P5 or performed with the anti-GFP antibody for HEK293T cell lysates, followed by Western blotting analysis performed with the anti-DISC1 antibody, or with anti-myc and anti-FLAG antibodies as described previously (Miyoshi et al., 2003).

In vitro kinase assays.

Mouse DBZ was subcloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector (GE Healthcare Biosciences). Protein purification was performed with glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare Biosciences). In vitro phosphorylation by Cdk5 or by Aurora A was performed in kinase buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mm EGTA) containing 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP (PerkinElmer) and 0.5 μg of GST-Cdk5/p35 (Sigma-Aldrich) or GST-Aurora A (Mori et al., 2009), GST-Ndel1 (Niethammer et al., 2000), and GST-DBZ in a 20 μl reaction mixture for 15 min. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS Laemmli sample buffer. The mixtures were then boiled, and the lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography.

EB3 experiments.

The following vectors were introduced into embryos at E14.5 via in utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer:

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + mu6pro (0.5 μg/μl).

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + mu6pro DBZ-RNAi (0.5 μg/μl).

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + pCAGGS myc-T219E:S251E Ndel1 (0.5 μg/μl).

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + pCAGGS myc-T219A:S251A Ndel1 (0.5 μg/μl).

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + pCAGGS (1 μg/μl).

pCAGGS EB3-EGFP (0.5 μg/μl) + pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl) + pCAGGS DISC1-HA (1 μg/μl).

Two days after electroporation (E16.5), the pregnant dams were killed, the cortices of the embryos were dissected out and dissociated with papain for 20 min, and the neurons were plated on polyethylenimine-coated glass-bottom dishes. The neurons were grown for 2 d in culture media consisting of neuronal basal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and 0.2 mm l-glutamine, and images that included the neurite processes were captured every 4 s for 2 min using a confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl-Zeiss) with a 63× water-immersion objective lens. Kymographs of time-lapse movies were generated using the Multiple Kymograph plug-in for ImageJ software (J. Rietdorf, European Molecular Biology Laboratory). The velocities from the kymographs were calculated using the ImageJ “read velocities from tsp” macro.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching.

Two vectors were introduced into embryos at E14.5 using in utero electroporation-mediated gene transfer: pCAGGS mDISC1-EGFP (2.0 μg/μl) and pCAGGS tdTomato (0.2 μg/μl). Primary culture of the cortical neurons was performed as described above, and the neurons were grown for 3 d before fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis. FRAP experiments were performed using a confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl-Zeiss) equipped with a 488 nm laser line and a 63× water-immersion objective lens. During FRAP analysis, the cells were maintained at 37°C in an incubation chamber, and a defined area of the growth cone was bleached with the 488 nm laser line at 100% power output for 10 iterations. Fluorescence recovery was monitored with the 488 nm laser line at 2% power every 1 s for 60 s. Data analysis was performed using the “Mean ROI” (acquisition of fluorescent intensity during the recovery) and “FRAP” modules (calculation of the half-time for fluorescence recovery) of the LSM710 ZEN software (Carl-Zeiss).

Statistical analyses.

We used Welch's t test or Student's t test to verify whether two sets of the mean were significantly different. For multiple comparisons, we performed a one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction.

Results

DBZ mRNA is localized primarily in the subventricular/intermediate zone of the developing cortex

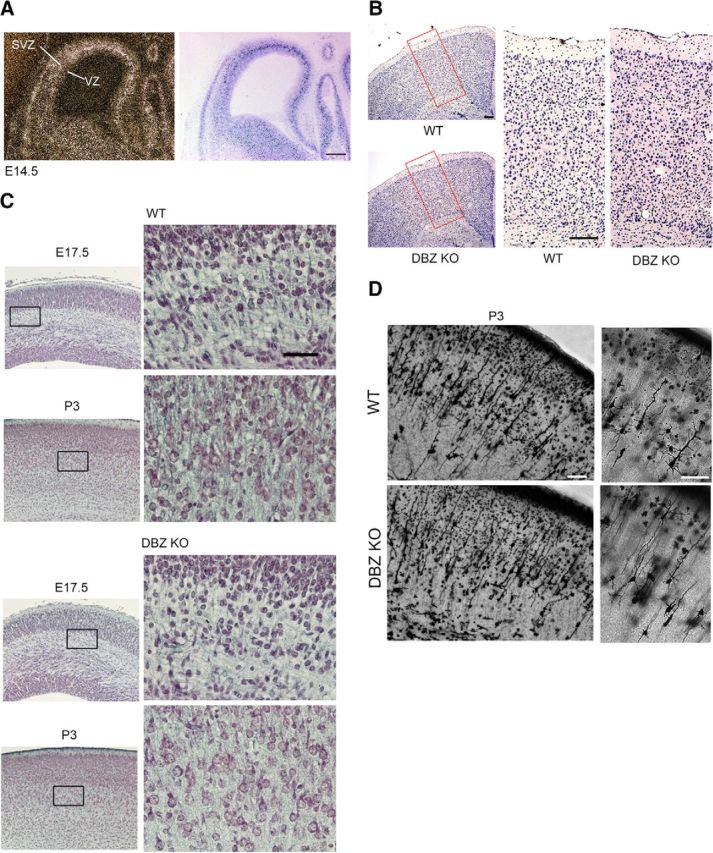

Because DISC1 is involved in cortical development, we investigated whether the DISC1 binding partner DBZ also plays a role in cortical development. To address this question, we examined the DBZ mRNA expression pattern in the developing mouse cortex. Our in situ hybridization study revealed that DBZ mRNA expression in the developing cortex occurs mainly in the subventricular/intermediate zone. No obvious expression was observed in the ventricular zone, where most neurons are generated, at E14.5 (Fig. 1A). This finding is consistent with previous studies regarding DBZ mRNA expression in rodent brains (Hattori et al., 2007; Koyama et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Neurite development is impaired by DBZ deletion. A, DBZ mRNA was localized primarily in the subventricular/intermediate zone (SVZ). A representative coronal section of an E14.5 cortex is shown (left). The section was counterstained with Nissl staining (right). No obvious expression was observed in the ventricular zone (VZ), whereas strong signals were observed in the SVZ. Scale bar, 200 μm. B, Histological examination of the cortices of the DBZ−/− (DBZ KO) and the littermate DBZ+/+ mice (WT). High-magnification views of the red boxes are shown on the right. Scale bars, 200 μm. C, Representative photomicrographs show coronal sections of the cortices at E17.5 and at P3 stained using Bodian's method. The DBZ−/− mice showed poor neurite development. High-magnification images in the squares on the left are shown in the next right panels. Scale bars, 100 μm. D, Examples of Golgi-impregnated P3 cerebral cortices of a WT and a DBZ KO mouse are shown. Magnified images are shown in the right. Pyramidal neurons with thin and less-branched dendrites were frequently observed in the DBZ KO. Scale bars, 40 μm.

DBZ is required for the proper radial migration of neurons that are born ∼E13.5

To elucidate the role of DBZ in vivo, DBZ was disrupted by homologous recombination (Koyama et al., 2013). First, we macroscopically examined the brains of adult (2 months old) DBZ−/− mice (DBZ KO) for malformations, and no apparent gross defects were observed. No obvious histological disturbances were observed either (Fig. 1B). Next, we investigated whether DBZ is involved in the morphological development of neurons. First, we used the Bodian method to visualize the nerve fibers of cortical neurons of the DBZ−/− mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates at E17.5 and P3. In the DBZ−/− mice, the nerve fibers were more weakly stained with this method than those nerve fibers of the WT littermates at both stages (Fig. 1C). Next, we examined the shapes of the cortical pyramidal neurons of the DBZ−/− mice using modified Golgi-Cox staining at P3 and found that their dendrites were less developed (Fig. 1D). Specifically, the diameters of the stained apical dendrites of the DBZ−/− mice were 48.6 ± 1.6% smaller (p < 1.0 × 10−3, Student's t test), and the total number of secondary dendrites was 33.5 ± 1.9% lower (p < 1.0 × 10−3, Student's t test) compared with the WT littermates (hereafter, all values represent the mean ± SEM). Next, we examined the formation of cortical layers in the DBZ−/− mouse cortex with layer-specific markers, such as T-box brain gene 1 (Tbr1) for deep-layer neurons (layers V–VI; Rubenstein et al., 1999) and homeobox cut gene 1 (Cux1) for superficial (upper)-layer neurons (layer II/III; Cubelos et al., 2010). No obvious differences in terms of signal intensity or distribution of Tbr1 or Cux1 were observed between the DBZ−/− mice and their wild-type littermates at E18.5.

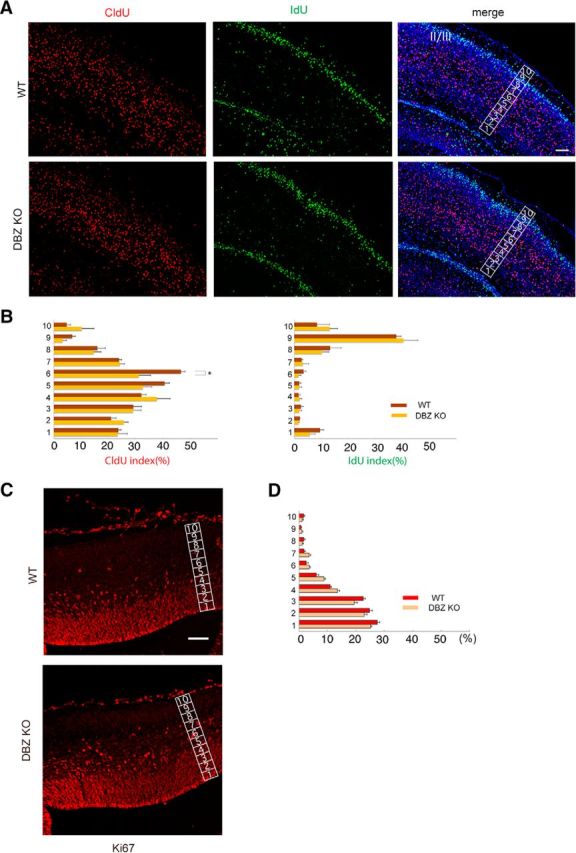

Next, we investigated neuronal cell positioning. Additionally, because DBZ has been demonstrated to be involved in cell division (Hirohashi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006), we investigated whether cell proliferation was altered in the developing neocortex. To address this issue, we consecutively injected the thymidine homologs CldU and IdU at E13.5 and at E16.5, respectively, and observed the localization of labeled cells on P2. CldU-labeled cells were widely dispersed in the cortex, whereas most IdU-labeled cells had accumulated in the superficial layer (layer II/III; Fig. 2A). The number of CldU-labeled cells in the cortex of the DBZ−/− mouse was similar to that of the wild-type littermate (Table 1), and this similarity was the case for IdU-labeled cells (Table 1). Additionally, no significant difference was observed between the DBZ−/− mouse and the controls in terms of the total number of labeled cells in the cortex at P2 (Table 1). These data suggest that DBZ does not play a critical role in cell proliferation in the developing cortex.

Figure 2.

Cell arrangement is impaired in the cortex due to DBZ deletion. A, Neuronal cell arrangement was altered by DBZ deletion. The thymidine homologs CldU and IdU were consecutively injected at E13.5 and E16.5, respectively, and the localization of labeled cells was observed at P2 in layer II/III (II/III). B, Distributions of CldU- and IdU-labeled cells in the cortex. The cortex was divided into 10 bins, and the labeled cells in each bin were counted. C, Immunohistochemistry against the proliferation marker Ki67 in an E15.5 mouse cortex. Scale bar, 200 μm. D, The labeled cells in each bin were counted. The values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Numbers of CldU-labeled cells and IdU-labeled cells in the cortex

| P2 | No. of CldU-labeled cells | No. of IdU-labeled cells | Total no. of Hoechst-stained cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT littermates (control) | 60.7 ± 6.0 | 26.7 ± 1.8 | 259.1 ± 7.8 |

| DBZ−/− mice | 54.1 ± 3.1 | 25.4 ± 4.8 | 249.4 ± 12.8 |

The numbers of CldU-labeled and IdU-labeled cells and the total number of Hoechst-stained cells in each bin were calculated (100 μm wide) and summed.

In addition to the dividing cells in the ventricular zone, other evidence indicates that the intermediate progenitors in the subventricular zone provide a fraction of upper cortical neurons. Because the intermediate progenitors are dividing at ∼E15.5 (Shikata et al., 2011), we further investigated the distribution of Ki67-positive neurons at E15.5. No obvious difference was observed in terms of the numbers or distributions of Ki67-positive cells in the cortex (Fig. 2C). By dividing the cortex into 10 bins, the Ki67-positive cells in each bin were counted in the presence or absence of DBZ (Fig. 2D). Percentages of Ki-67-positive cells were as follows (shown in WT vs DBZ KO, n = 5, Welch's t test): Bin 1: 27.49 ± 0.92 versus 25.10 ± 0.50; Bin 2: 24.82 ± 0.95 versus 22.95 ± 3.09; Bin 3: 22.61 ± 0.68 versus 19.43 ± 1.09; Bin 4: 10.97 ± 0.46 versus 13.51 ± 0.69; Bin 5: 6.03 ± 0.88 versus 8.71 ± 0.64; Bin 6: 2.52 ± 0.61 versus 3.63 ± 0.28; Bin 7: 1.67 ± 0.44 versus 3.51 ± 0.51; Bin 8: 1.62 ± 0.42 versus 1.08 ± 0.39; Bin 9: 0.59 ± 0.28 versus 0.99 ± 0.31; and Bin 10: 1.66 ± 0.29 versus 1.08 ± 0.39. No significant differences were observed between WT and DBZ KO in terms of Ki67-positive cell distribution.

Next, we examined the distributions of CldU- and IdU-labeled cells (Fig. 2A,B). The CldU index (the number of CldU-positive cells divided by the number of Hoechst-positive cells, shown as percentages) was as follows (WT vs DBZ KO): Bin 1: 23.60 ± 1.08 versus 23.42 ± 3.50; Bin 2: 20.97 ± 1.84 versus 25.64 ± 1.65; Bin 3: 29.15 ± 3.00 versus 29.07 ± 2.90; Bin 4: 32.06 ± 1.71 versus 37.76 ± 4.94; Bin 5: 40.59 ± 1.79 versus 32.58 ± 3.31; Bin 6: 46.56 ± 1.55 versus 31.17 ± 4.39 (p = 0.030); Bin 7: 23.84 ± 1.04 versus 24.19 ± 1.75; Bin 8: 15.99 ± 2.90 versus 14.61 ± 2.74; Bin 9: 6.78 ± 1.12 versus 3.23 ± 1.41; Bin 10: 4.73 ± 1.41 versus 10.22 ± 4.53. The IdU index (%) in each bin was as follows: Bin 1: 9.53 ± 1.44 versus 5.77 ± 1.95; Bin 2: 2.06 ± 0.13 versus 1.61 ± 0.27; Bin 3: 2.43 ± 0.89 versus 1.83 ± 0.91; Bin 4: 1.64 ± 0.56 versus 1.98 ± 0.83; Bin 5: 1.85 ± 0.63 versus 1.78 ± 0.95; Bin 6: 3.45 ± 0.95 versus 1.56 ± 0.90; Bin 7: 2.70 ± 0.50 versus 3.15 ± 2.19; Bin 8: 13.27 ± 4.09 versus 10.18 ± 2.61; Bin 9: 37.72 ± 1.77 versus 40.33 ± 5.43; and Bin 10: 8.40 ± 4.70 versus 13.10 ± 2.98 (n = 3, Student's t test). Although the distributions of IdU-labeled cells were indistinguishable between the DBZ−/− mice and controls, the localization of CldU-labeled cells in the DBZ−/− mice differed from that in controls, suggesting that radial migration was partially impaired as a result of DBZ deficiency.

Acute DBZ insufficiency results in migration arrest

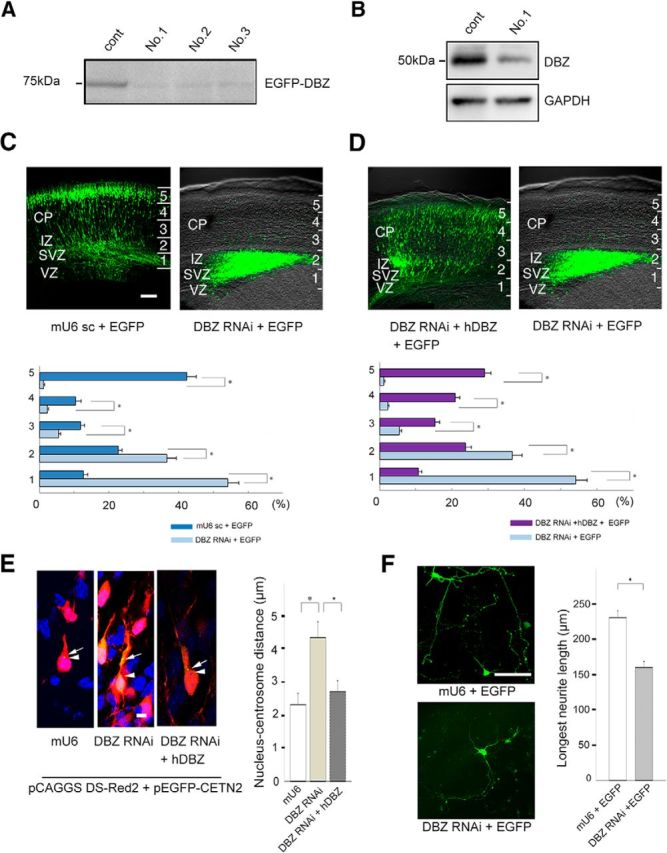

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the DBZ−/− mouse phenotype, we performed DBZ-knockdown experiments. First, we constructed three vectors (knockdown vectors) that produce different short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against DBZ to knockdown DBZ by RNA interference. Vector No. 1 showed the strongest knockdown activity against DBZ (Fig. 3A). We then confirmed the knockdown activity of Vector No. 1 against endogenous DBZ (Fig. 3B). We used Vector No. 1 thereafter for DBZ knockdown (called the DBZ knockdown vector).

Figure 3.

Acute DBZ insufficiency leads to impaired radial migration, poor neurite elongation and a loss of centrosome-nucleus coupling. A, The efficiencies of RNA interference with different shRNAs against DBZ (Nos. 1–3) were evaluated. No. 1 markedly suppressed EGFP-DBZ expression and was subsequently used for all DBZ-knockdown experiments. B, shRNAs against DBZ No. 1 suppressed endogenous DBZ expression in N2a cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. C, The mU6pro scramble vector (mU6 sc) was used as a control (left). DBZ-knockdown radially migrating cells did not migrate far beyond the intermediate zone (right). CP, Cortical plate; IZ, intermediate zone. The neocortex was subdivided evenly into five bins (1–5) from the ventricular zone (VZ) to the CP. The occurrences of GFP-labeled cells (cell bodies) in each bin were counted. D, DBZ-knockdown neurons that were cotransfected with the hDBZ migrated into the cortical plate (left), whereas sole DBZ-knockdown neurons did not migrate (right, the same image of C). Scale bar, 100 μm. E, Neurons in the cortical plate were examined in the brain slices. Neurons, their centrosomes and their nuclei, were labeled with DS-Red2 (shown in red), EGFP-CETN2 (green), and Hoechst (blue), respectively. The nucleus–centrosome distances were greater in neurons with RNAi against DBZ compared with controls. CETN2, Centrin 2. Arrows indicate centrosomes, and arrowheads represent the edges of nuclei. Scale bar, 5 μm. F, At E17.5, DBZ-expressing neurons were collected from the cortices and dissociated for primary culture. The lengths of the primary neurites were measured after culture for 96 h. Acute DBZ-insufficient neurons had shorter primary neurites than controls. Scale bar, 100 μm. The values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

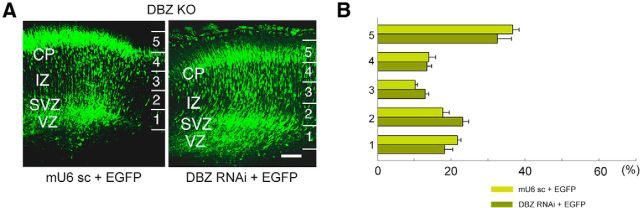

We injected the DBZ knockdown vector in the ventricular zone of the neocortex at E14.5 using an in utero gene-transfer technique involving electroporation (in utero electroporation). An EGFP-expressing vector was coelectroporated with the knockdown vector so that transfected neurons could be visualized. At E18.5, most labeled neurons in the controls were accumulated in the upper cortical plate, suggesting that these neurons left the ventricular zone and then migrated outward to the cortical plate (Fig. 3C, left). By contrast, DBZ-insufficient neurons did not migrate far outward to the cortical plate; only a few labeled neurons reached the upper cortical plate, and most neurons halted in the intermediate zone or in the subventricular zone (Fig. 3C,D, right; please note that these images are identical). The number of EGFP-expressing cells in each bin was calculated by dividing the cortex into five bins. The percentages of EGFP-positive cells in each bin compared with the total number of EGFP-positive cells were as follows (n = 5 each, Welch's t test) in the case of mU6pro scramble versus DBZ RNAi: Bin 1: 12.67 ± 1.24 versus 54.10 ± 3.19 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); Bin 2: 22.68 ± 1.04 versus 36.67 ± 2.57 (p = 0.002); Bin 3: 11.87 ± 1.08 versus 5.55 ± 0.53 (p = 0.002); Bin 4: 10.39 ± 1.51 versus 2.27 ± 0.38 (p = 0.005); and Bin 5: 42.36 ± 2.67 versus 1.13 ± 0.37 (p < 1.0 × 10−3). This RNAi-mediated impairment of radial migration was rescued by coexpressing RNAi-resistant human DBZ (hDBZ; Fig. 3D). The actual data are as follows (n = 5, Welch's t test) in the case of DBZ RNAi + hDBZ versus DBZ RNAi: Bin 1: 10.84 ± 0.90 versus 54.10 ± 3.19 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); Bin 2: 23.68 ± 1.65 versus 36.67 ± 2.57 (p = 0.002); Bin 3: 15.44 ± 1.30 versus 5.55 ± 0.53 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); Bin 4: 20.92 ± 1.23 versus 2.27 ± 0.38 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); and Bin 5: 28.96 ± 1.70 versus 1.13 ± 0.37 (p < 1.0 × 10−3). Because the off-target effects of shRNAs on radial migration has been intriguing (Iguchi et al., 2012; Baek et al., 2014), we examined whether our DBZ knockdown vector impairs radial migration or not in the DBZ−/− mice (Fig. 4). Incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells in each bin were as follows (n = 5 each, Welch's t test), shown as mU6 scramble versus DBZ RNAi: Bin 1: 21.61 ± 1.08 versus 18.15 ± 2.29 (p = 0.222); Bin 2: 17.76 ± 1.68 versus 23.12 ± 1.66 (p = 0.053); Bin 3: 10.17 ± 0.63 versus 12.93 ± 1.03 (p = 0.057); Bin 4: 13.87 ± 1.88 versus 13.35 ± 1.27 (p = 0.825); and Bin 5: 36.59 ± 1.74 versus 32.45 ± 3.79 (p = 0.362). No significant off-target effects were observed.

Figure 4.

Acute DBZ insufficiency does not significantly alter the migration of radially migrating neurons in DBZ KO mouse. A, B, The mU6pro scramble vector (mU6 sc) was used as a control (left). DBZ-knockdown radially migrating neurons of the DBZ KO mouse did not exhibit any significant difference in terms of localization. Vectors were injected at E14.5 and brains were observed at E18.5. The neocortex was subdivided evenly into five bins. Occurrences of GFP-labeled cells (cell bodies) in each bin were counted. Scale bar, 100 μm. Values represent the mean ± SEM.

To elucidate the mechanisms of the migration arrest due to acute DBZ insufficiency, we examined the effects of DBZ on nucleus-centrosome coupling, which has been proposed to be an important mechanism accounting for neuronal migration. We examined E14.5 transfected migrating neurons in the intermediate zone at E17.5 and observed a significant increase in the distance between the nucleus and the centrosome in the DBZ-insufficient neurons (Fig. 3E). The actual distances were as follows (n = 20, post hoc Bonferroni test): control (mU6): 2.31 ± 0.35 μm; DBZ RNAi: 4.33 ± 0.49 μm; DBZ RNAi + hDBZ: 2.72 ± 0.30 μm. The p values were as follows: mU6 versus DBZ RNAi: p = 0.001; DBZ RNAi versus DBZ RNAi + hDBZ: p = 0.023.

Because it is difficult to observe the shapes of entire neurons clearly in vivo, we conducted further comparisons of the neurite length between DBZ-insufficient neurons and control neurons in primary culture (Fig. 3F). Gene transfer was performed at E14.5, and neurons were collected at E17.5 and dissociated for primary culture. Ninety-six hours later, the lengths of the longest neurites were measured in vitro. DBZ-knockdown neurons had shorter neurites than control neurons (Fig. 3F), suggesting that proper neurite extension is dependent on DBZ. The actual lengths were as follows (n = 28 for mU6, n = 30 for DBZ RNAi, Welch's t test): 230.34 ± 9.23 μm (control, mU6) and 160.34 ± 8.06 μm (DBZ RNAi); p < 1.0 × 10−3.

DBZ is related to the dual phosphorylation of threonine 219 and serine 251 on Ndel1, whose phosphorylation status affects radial migration

Ndel1 is required for dynein function and facilitates the interaction between Lis1 and dynein, and Ndel1 activity is regulated by phosphorylation (Shu et al., 2004; Toyo-Oka et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2007; Yamada et al., 2008). It has been shown that threonine 219 is phosphorylated by Cdk5 (Mori et al., 2007) and serine 251 is phosphorylated by Aurora A (Mori et al., 2009; Takitoh et al., 2012). Dynein and dynactin motor proteins have key roles not only in retrograde transport but also in microtubule advance during growth cone remodeling associated with axonogenesis (Lenz et al., 2006; Grabham et al., 2007). Because DBZ binds to Ndel1 in vitro (Hirohashi et al., 2006), we examined whether DBZ modulates the phosphorylation status of Ndel1 in vivo. Ndel1 phosphorylation at threonine 219 and at serine 251 (pT219-Ndel1 and pS251-Ndel1, respectively) was increased in the cortices of the DBZ−/− mice (Fig. 5A). The signal intensity of total Ndel1 in the DBZ−/− mice compared with their WT littermates was 1.02 ± 0.09 (n = 3, p = 0.86, Welch's t test; Fig. 5A left). We then normalized the pT219-Ndel1 and pS251-Ndel1 signal intensities with full-length Ndel1 in each case. The mean signal intensity of pT219-Ndel1 of DBZ KO against WT was 1.34 ± 0.50 (n = 3, p = 0.008, Welch's t test; Fig. 5A, middle), whereas that of pS251-Ndel1 of DBZ KO against WT was 1.42 ± 0.05 (n = 3, p = 0.007, Welch's t test; Fig. 5A, right).

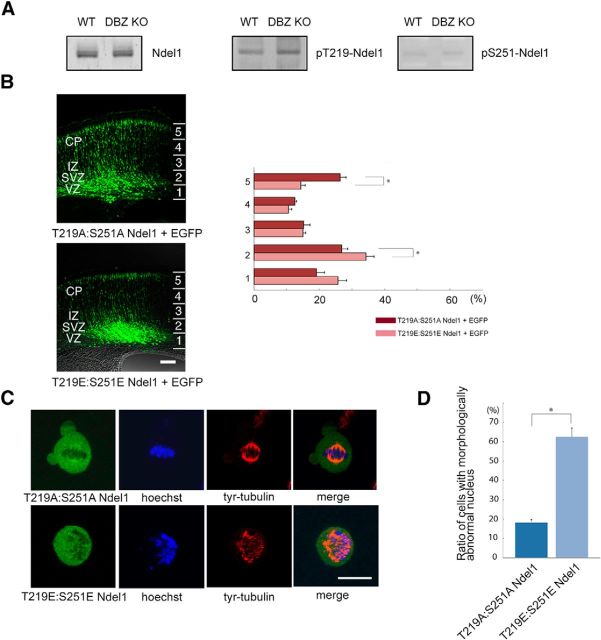

Figure 5.

DBZ regulates Ndel1 phosphorylation, and the phosphorylation-status of Ndel1 is critical for radial migration. A, Cell lysates from the cerebral cortices of E18.5 DBZ KO and WT were subjected to Western blot analyses. The phosphorylation of threonine 219 and serine 251 of Ndel1 increased in the DBZ KO. B, Radial migration was impaired by the ectopic expression of a dual-phospho-mimetic form of Ndel1 (T219E:S251E Ndel1). Scale bar, 100 μm. C, The ratio of cells with morphologically abnormal nuclei increased in T219E:S251E Ndel1-overexpressing cells. T219E:S251E Ndel1- or T219A:S251A Ndel1-expressing vectors were transfected into HeLa cells. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were immunostained with anti-tyrosinated tubulin antibody and observed with confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 5 μm. D, The ratio of cells with morphologically abnormal nucleus is shown. Values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

The ectopic expression of the dual-phosphorylation mimetic mutant (T219E:S251E Ndel1), in which threonine 219 and serine 251 were replaced with glutamate, resulted in migration arrest (Fig. 5B, bottom), whereas that of the nonphosphorylatable mutant (T219A:S251A Ndel1), in which threonine 219 and serine 251 were replaced with alanine, did not induce any alterations in radial migration (Fig. 5B, top). The number of EGFP-expressing cells in each bin was calculated by dividing the cortex into 5 bins. The incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells of T219A:S251A Ndel1 versus T219E Ndel1:S251E Ndel1 in each bin were as follows (n = 5 each. Welch's t test): Bin 1: 19.08 ± 2.54 versus 25.69 ± 2.71; Bin 2: 26.86 ± 1.86 versus 34.36 ± 2.41 (p = 0.041); Bin 3: 15.04 ± 1.93 versus 15.11 ± 0.83; Bin 4: 12.61 ± 0.49 versus 10.53 ± 1.01; and Bin 5: 26.41 ± 1.78 versus 14.32 ± 1.42 (p = 0.001; Fig. 5B).

To our knowledge, simultaneous Ndel1 phosphorylation at threonine 219 and serine 251 has not been previously reported. Thus, we next investigated the effects of such double phosphorylation on Ndel1 activity. When we overexpressed T219E:S251E Ndel1 in dividing HeLa cells, the ratio of cells with distorted nuclei increased (Fig. 5C,D). Abnormal spindle fibers were observed in ∼60% of T219E:S251E Ndel1-transfected cells, whereas abnormal spindle fibers were observed in ∼20% of T219A:S251A Ndel1-transfected cells, suggesting that the dual phosphorylation of Ndel1 resulted in centrosome malfunctioning. The actual incidences (%) of T219A:S251A Ndel1 and T219E:S251E Ndel1 cells with abnormal spindles were as follows (n = 3, Welch's t test): 18.57 ± 0.99 and 62.85 ± 4.36 (p = 0.007), respectively.

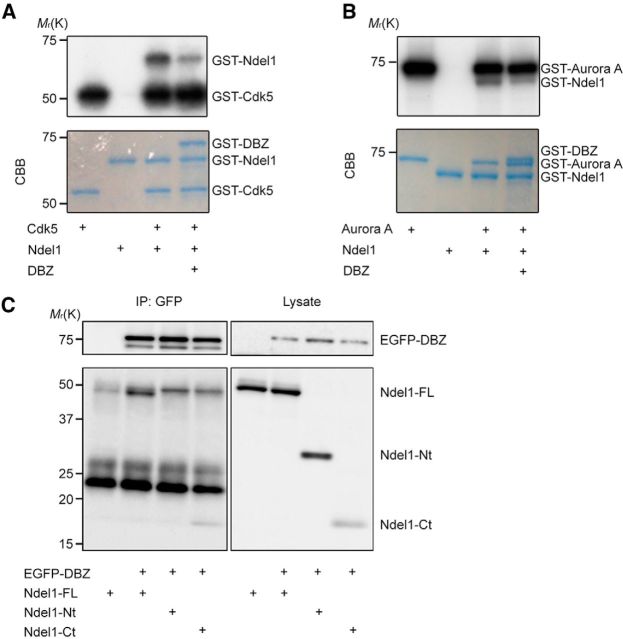

Because Ndel1 is a substrate of Cdk5 and of Aurora A, both of which affect neuronal migration (Niethammer et al., 2000; Mori et al., 2009; Takitoh et al., 2012), we performed an in vitro phosphorylation assay of Cdk5 and Aurora A to examine whether DBZ affected the direct phosphorylation of Ndel1 by Cdk5 and Aurora A. GST-Ndel1 was significantly less phosphorylated by Cdk5 and Aurora A in the presence of DBZ than in the absence of DBZ (Fig. 6A,B). These results suggest that DBZ regulates Ndel1 phosphorylation by Cdk5 and Aurora A.

Figure 6.

Cdk5 and Aurora A are involved in Ndel1 phosphorylation. A, B, Examination of the effect of GST-DBZ on phosphorylation of GST-Ndel1 by GST-Cdk5/p35 (A) and GST-Aurora A (B). GST-Ndel1 was incubated with GST-DBZ and GST-Cdk5/p35 (A) or GST-Aurora A (B). Phosphorylation of GST-Ndel1 decreased in the presence of DBZ (top) in both cases. CBB staining (bottom). C, Coimmunoprecipitation assay of DBZ and Ndel1. HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-DBZ in combination with full-length Ndel1; myc-Ndel1-FL-FLAG (Ndel1-FL), the N-terminus of Ndel1; myc-Ndel1-Nt (Ndel1-Nt, residues 1–205), or the C-terminus of Ndel1; Ndel1-Ct-FLAG (Ndel1-Ct, residues 206–345). Immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-GFP antibody, and Western blotting was performed with anti-myc and anti-FLAG antibodies.

We further examined the binding region of Ndel1 to DBZ and observed that the C-terminal region of Ndel1 coimmunoprecipitated with DBZ. This finding suggests that DBZ binds to the C-terminal region of Ndel1, in which phosphorylation sites for Cdk5 (T219) and Aurora A (S251) are contained (Fig. 6C).

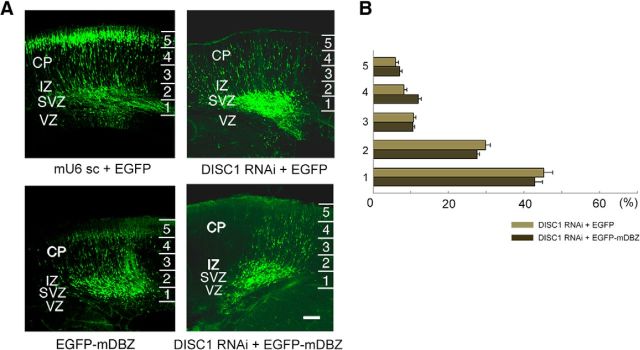

DISC1 is capable of rescuing migration arrest and centrosome-nucleus decoupling due to DBZ insufficiency and to Ndel1 dual phosphorylation

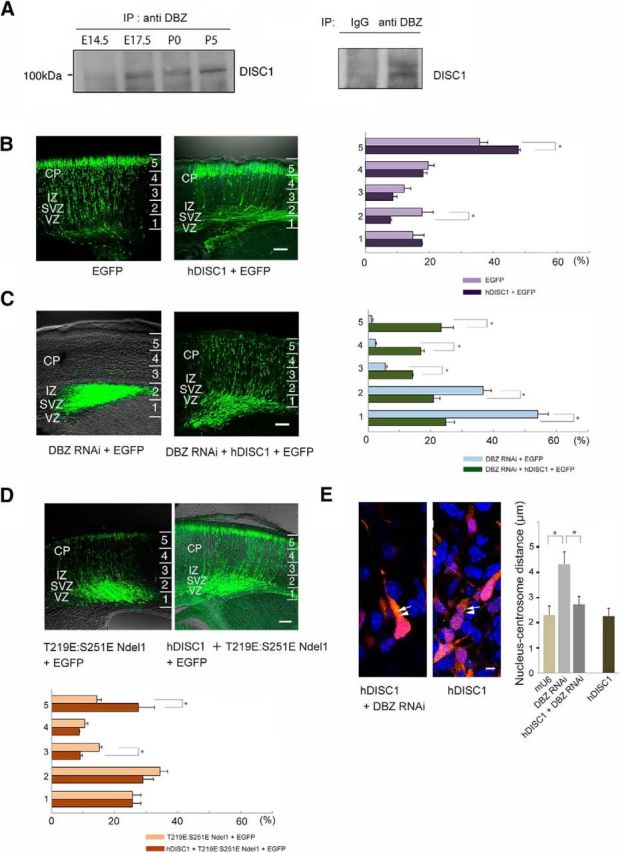

Next, because DBZ is a DISC1 binding partner, we examined how DISC1 is involved in the role of DBZ in radial migration. First, we confirmed that DBZ binds to DISC1 in the developing neocortex (Fig. 7A). Figure 3C shows that acute DBZ insufficiency resulted in the impaired radial migration of cortical neurons. Furthermore, DISC1 insufficiency has been shown to perturb cortical neuron radial migration (Kamiya et al., 2005). Therefore, we examined whether DISC1 and/or DBZ overexpression affected the radial migration of DBZ- or DISC1-insufficient neurons. Surprisingly, DISC1 rescued the migration arrest caused by DBZ insufficiency (Fig. 7C), whereas DBZ did not rescue impaired migration caused by DISC1 insufficiency (Fig. 8). The incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells in each bin in Figure 7C were as follows (shown as DBZ RNAi + hDISC1 vs DBZ RNAi, n = 5, Welch's t test): Bin 1: 24.80 ± 2.77 versus 54.10 ± 3.19 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); Bin 2: 20.78 ± 2.43 versus 36.67 ± 2.57 (p = 0.001); Bin 3: 14.25 ± 0.14 versus 5.55 ± 0.53 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); Bin 4: 16.77 ± 1.11 versus 2.27 ± 0.38 (p < 1.0 × 10−3); and Bin 5: 23.27 ± 4.32 versus 1.13 ± 0.37 (p = 0.003). The incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells in each bin in Figure 8 were as follows (shown as DISC1 RNAi + mDBZ vs DISC1 RNAi, n = 3, Welch's t test): Bin 1: 42.77 ± 2.17 versus 45.26 ± 2.36; Bin 2: 27.62 ± 0.65 versus 29.84 ± 1.21; Bin 3: 10.54 ± 0.57 versus 10.77 ± 0.61; Bin 4: 11.95 ± 0.84 versus 8.19 ± 0.82; and Bin 5: 7.11 ± 0.60 versus 5.94 ± 0.78. Concurrently, we were curious about a fact that an excess of DISC1 had some effects on radial migration (Fig. 7B). The incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells were as follows (shown as hDISC1 + EGFP vs EGFP, n = 5, Welch's t test): Bin 1: 17.66 ± 0.29 versus 14.87 ± 3.45; Bin 2: 7.66 ± 0.35 versus 17.77 ± 3.47 (p = 0.043); Bin 3: 8.66 ± 1.38 versus 12.07 ± 2.1; Bin 4: 18.02 ± 1.31 versus 19.64 ± 1.01; and Bin 5; 48.09 ± 0.54 versus 35.65 ± 2.53 (p = 0.007).

Figure 7.

DISC1 rescues impaired migration and impaired nucleus-centrosome coupling due to DBZ insufficiency. A, Mouse brain lysates at E14.5, E17.5, P0, or P5 were immunoprecipitated with the anti-DBZ antibody. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blotting analyses with the anti-DISC1 antibody (left). The anti-DBZ antibody was examined with mouse brain lysate at P5 using normal IgG (right). B, C, Using in utero electroporation gene transfer, the indicated vectors, including an EGFP-expressing vector, were transfected into the lateral ventricle of mouse embryos at E14.5, and the migration of transfected cells was observed at E18.5. The neocortex was evenly subdivided into five bins. The incidences (%) of GFP-labeled cells (cell bodies) in each bin were counted. The arrest of migration in DBZ-knockdown neurons (C, left); the same image as Fig. 3C,D) was rescued by the coexpression of human DISC1 (hDISC1). Scale bar, 100 μm. D, hDISC1 rescue of impaired migration due to the expression of a dual phosphorylation mimetic form of Ndel1 (T219E:S251E). Expression vectors for T219E:S251E Ndel1 and hDISC1 were transfected together with an EGFP-expressing vector into the ventricle at E14.5, and the transfected cortices were observed at E18.5. Comparisons of the distribution of EGFP-labeled cells between the T219E:S251E Ndel1-transfected and hDISC1/T219E:S251E Ndel1-transfected cortices. hDISC1 coexpression rescued the impaired migration caused by T219E:S251E overexpression. E, The impaired nucleus-centrosome coupling due to DBZ insufficiency was rescued by hDISC1 coexpression. Additionally, we measured the nucleus-centrosome distance of neurons with exogenous hDISC1 alone. There were no significant changes in the nucleus-centrosome distance in this case. Scale bar, 5 μm. The values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Mouse DBZ (mDBZ) overexpression did not rescue the migration arrest due to DISC1 knockdown. A, B, The neocortex was subdivided evenly into five bins. The occurrences of GFP-labeled cells (cell bodies) in each bin were counted. Scale bar, 100 μm. The values represent the mean ± SEM.

Next, we investigated whether DISC1 rescued the migration impairment caused by the ectopic expression of the dual phosphorylation mimetic form of Ndel1, T219E:S251E Ndel1. The coexpression of DISC1 partially rescued this migration impairment (Fig. 7D). The incidences (%) of EGFP-positive cells in each bin were as follows (shown as hDISC1 + T219E:S251E Ndel1 vs T219E:S251E Ndel1, n = 4 for hDISC1 + T219E:S251E Ndel1 and n = 5 for T219E:S251E Ndel1, Welch's t test): Bin 1: 25.62 ± 2.66 versus 25.69 ± 2.71; Bin 2: 28.96 ± 3.43 versus 34.35 ± 2.41; Bin 3: 9.07 ± 0.69 versus 15.11 ± 0.83 (p = 0.001); Bin 4: 8.74 ± 0.23 versus 10.53 ± 1.01; and Bin 5: 27.61 ± 5.29 versus 14.32 ± 1.42 (p = 0.008).

Finally, we examined whether DISC1 rescued the impaired nucleus-centrosome coupling produced by DBZ insufficiency. The distance between the nucleus and the centrosome was rescued by the coexpression of DISC1 (Fig. 7E). The nucleus-centrosome distances were 2.31 ± 0.35 μm (control, mU6 only), 4.33 ± 0.49 μm (DBZ RNAi), and 2.82 ± 0.25 μm (DBZ RNAi + hDISC1; n = 20 each). The p values were as follows: mU6 versus DBZ RNAi was 0.001 and DBZ RNAi versus DBZ RNAi + DISC1 was 0.023 (post hoc Bonferroni test). Additionally, we further asked whether exogenous expression of DISC1 modulates the nucleus-centrosome coupling. DISC1 did not show any further effects on the distance between the nucleus and the centrosome (Fig. 7E).

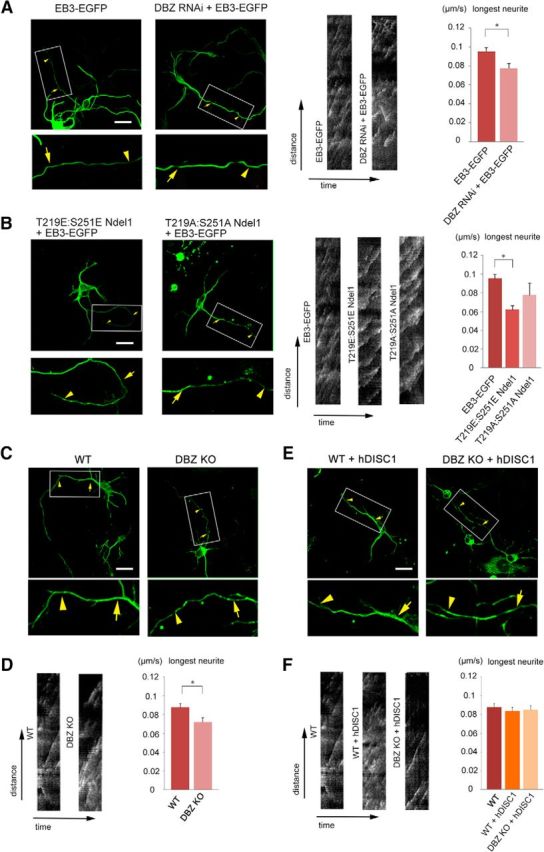

DBZ regulates neurite elongation by controlling microtubule extension

Because neurite extension was impaired in the DBZ−/− mice and in the DBZ-knockdown neurons, we determined whether the speed of microtubule growth was altered by monitoring the behavior of the microtubule plus-end binding (EB) protein EB3 in the neurites. The EGFP-tagged EB3 expression vector was transfected into the ventricular zone at E14.5, and cortical neurons were collected at E16.5 and cultured for 2 d before observation. Time-lapse images of EB3 allowed us to monitor how the microtubules extended and/or retracted. The extension speeds of microtubules detected by accumulated EB3 were slower in the neurites of DBZ-insufficient neurons (0.073 ± 0.007 μm/s, EB3-EGFP + DBZ RNAi) than in those of the control neurons (0.094 ± 0.006 μm/s, EB3-EGFP + mu6; n = 20, p = 0.033, Welch's t test; Fig. 9A). The slow extension of microtubules detected with accumulated EB3 was also observed in T219E:S251E Ndel1-overexpressing neurons: 0.062 ± 0.003 μm/s (T219E:S251E Ndel1 + EB3-EGFP) and 0.076 ± 0.005 μm/s (T219A:S251A Ndel1 + EB3-EGFP); p < 1.0 × 10−3 for EB3-EGFP versus T219E:S251E Ndel1 + EB3-EGFP (n = 20 each, Welch's t test; Fig. 9B). Indeed, the velocity of EB3 was slower in the DBZ−/− neurons (0.071 ± 0.005 μm/s) than the wild-type neurons (0.088 ± 0.004 μm/s; n = 20, p = 0.017, Welch's t test; Fig. 9C,D). Interestingly, EB3 velocities in microtubules of the DBZ−/− neurons with DISC1 were similar to the velocities in microtubules of the DBZ+/+ neurons with and without DISC1 (n = 20, post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 9E,F).

Figure 9.

Depleting DBZ or expressing a phosphorylation mimetic form of Ndel1 results in a slower extension of EB3-EGFP, and coexpressing DISC1 rescues this phenotype. A, Using in utero electroporation gene transfer, the indicated vectors were transfected into the lateral ventricles of mouse embryos at E14.5. At E16.5, EB3-EGFP-expressing neurons were collected from the cortices and dissociated for primary culture. Forty-eight hours later, time-lapse images were obtained. Scale bar, 20 μm. EB3 binds to microtubule tips, and EB3 movements between the arrow and the arrowhead are shown in the kymographs. The results demonstrated that the EB3-EGFP velocity significantly decreased in DBZ-knockdown neurons. B, T219E:S251E Ndel1-expressing vectors or T219A:S251A Ndel1-expressing vectors were transfected together with the EB3-EGFP-expressing vector. The EB3 velocity in neurites significantly decreased in the T219E:S251E Ndel1-expressing neurons. C, D, The EB3 velocity in the neurites decreased in DBZ−/− neurons. E, F, Human DISC1 (hDISC1)-HA-expressing vectors were cotransfected into the lateral ventricle of mouse embryos at E14.5. Unlike DBZ−/− neurons without DISC1, no significant alteration in terms of EB3 velocity was observed among DISC1-overexpressing DBZ+/+ neurons, DISC1-overexpressing DBZ−/− neurons and neurons from WT. The values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

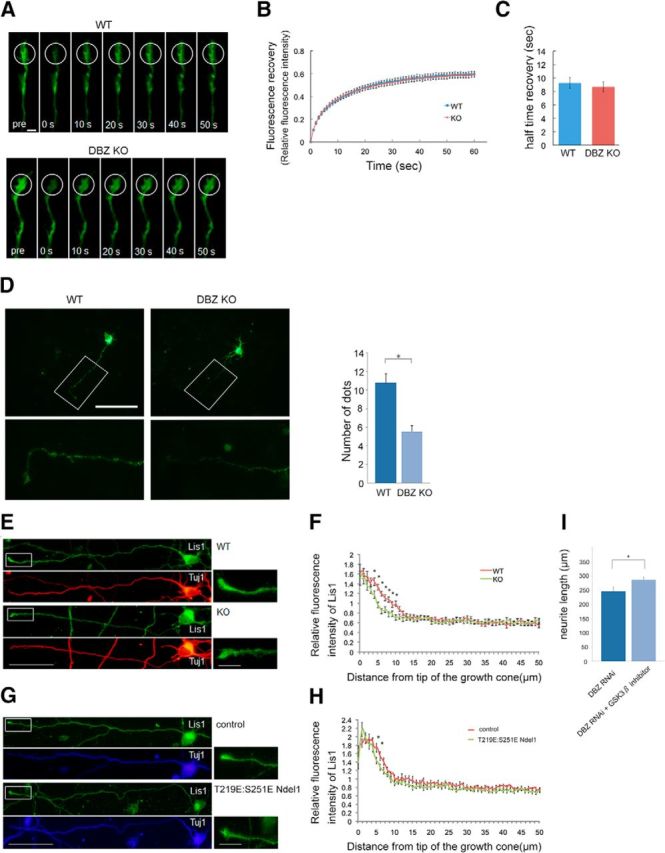

Decreased amounts of DISC1 and Lis1 are transported distally, and GSK3β activity is enhanced under the DBZ-deficient condition

DISC1 forms a complex with Lis1, and this complex is transported anterogradely along the microtubule (Taya et al., 2007). Because DISC1 plays a crucial role in neurite extension through its modulation of GSK3β activity at the distal end (Mao et al., 2009), we assumed that smaller amounts of DISC1 were transported, resulting in poor neurite elongation in the DBZ-deficient condition. Our assumption is consistent with our observation that DISC1 rescued the phenotype of the DBZ−/− mice in which neurites were poorly developed. To evaluate DISC1 transport into the growth cone, cortical neurons transfected with an EGFP-tagged DISC1 expression vector at E14.5 were collected at E16.5 and cultured for 3 d before FRAP analysis. Surprisingly, no differences were observed between the cortical neurons taken from the wild-type littermates and the DBZ−/− mice; half of the DISC1-EGFP was recovered to the growth cone within 10 s: the half-times of recovery were 9.3 ± 0.8 s (WT) and 8.7 ± 0.7 s (DBZ−/−; n = 40, p = 0.599, Welch's t test; Fig. 10A–C). Therefore, the transport speed of the DISC1 complex was independent of DBZ activity. Next, to examine whether DBZ was involved in DISC1 transport, we overexpressed DISC1-HA in cortical neurons with in utero electroporation and observed the DISC1-HA distribution along the axons. Because DISC1-HA was visible as small dots, we counted the visible dots along the axon (distal end – 100 μm from the distal end). The number of DISC1-HA dots decreased in the DBZ−/− mice (5.5 ± 0.7) compared with controls (10.7 ± 1.0; n = 18, p < 1.0 × 10−3, Welch's t test; Fig. 10D). Therefore, it is likely that a decreased amount of DISC1 was transported in the DBZ−/− mice.

Figure 10.

Deleting DBZ or overexpressing a phosphorylation mimetic form of Ndel1 impairs the anterograde transport of DISC1 and Lis1 to the proximal ends. A, FRAP analysis of DBZ+/+ and DBZ−/− cortical neurons transfected with the mDISC1-EGFP expression vector. The indicated areas (white circles) of a growth cone were bleached, and fluorescence recovery was monitored every 1 s for 1 min. B, Quantitative fluorescence recovery data were calculated from the fluorescence intensities of the bleached areas of the DBZ+/+ and DBZ−/− cortical neurons over a period of 1 min following photobleaching. The data were normalized such that the fluorescence intensity of the prebleach sample was set to one, and the initial postbleach sample was set to zero. C, The half-time of recovery was calculated from each recovery curve. Scale bar, 5 μm. D, DISC1-HA-expressing vectors were transfected into DBZ+/+ neurons and DBZ−/− neurons. Neurons were stained with the anti-HA antibody. Magnified images of the white boxes are shown in the bottom. The occurrences of HA signals within 100 μm of the tip of axon were counted. The number of HA signals significantly decreased in the DBZ−/− neurons. Scale bar, 100 μm. E, Cortical neurons cultured from DBZ+/+ or DBZ−/− mouse embryos (E16.5) were stained with antibodies against Lis1 (green) and βIII-tubulin (Tuj1; red) at DIV3. Magnified images of the white boxes are shown on the right. F, Relative immunofluorescence intensities of Lis1 over Tuj1 within 50 μm of the tip of the growth cone were plotted. The fluorescence intensity of Lis1 decreased in the proximal side of the growth cones of the DBZ−/− neurons. G, The control empty vector or T219E:S251E Ndel1 expression vector, together with the tdTomato expression vector, were transfected at E14.5. At E16.5, tdTomato-positive neurons were collected from the cortices and dissociated for primary culture. Cortical neurons were stained with antibodies against Lis1 (green) and βIII-tubulin (Tuj1; blue) at DIV3. Magnified images of the white boxes are shown in the right. H, Relative immunofluorescence intensities of Lis1 over Tuj1 within 50 μm of the tip of the growth cone were plotted. The fluorescence intensity of Lis1 decreased in the proximal side of the growth cones in T219E:S251E Ndel1-expressing neurons. Scale bars, 50 μm (left) and 10 μm (right). I, The DBZ RNAi vector and the EGFP expression vector were transfected into the lateral ventricle at E14.5, and cortical neurons were collected and dissociated for primary culture at E16.5. Ninety-six hours after the beginning of primary culturing, the lengths of the primary neurites were measured. A GSK3β inhibitor rescued the poor neurite extension caused by acute DBZ insufficiency. The values represent the mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05.

Next, because our observations were made under conditions of DISC1 overexpression, we studied how the endogenous DISC1 complex and/or complex components were transported in vivo by assessing the subcellular distribution of Lis1, which is one of the critical components of the DISC1 complex. Primary cultured cortical neurons taken from E16.5 embryos were grown for 3 d for immunocytochemical analysis, and the immunofluorescence intensity of Lis1 in the axons was examined. Smaller amounts of Lis1 were transported in the DBZ KO compared with the wild-type mice. The relative fluorescence intensities of Lis1 were as follows (n = 20, Welch's t test): 1.44 ± 0.10 (WT) and 1.17 ± 0.08 (DBZ KO) at 4 μm from the tip (p = 0.043); 1.33 ± 0.08 (WT) versus 0.96 ± 0.06 (DBZ KO) at 5 μm (p = 0.001); 1.20 ± 0.08 (WT) and 0.84 ± 0.05 (DBZ KO) at 6 μm (p < 1.0 × 10−3); 1.11 ± 0.07 (WT) and 0.87 ± 0.067 (DBZ KO) at 7 μm (p = 0.013); 1.08 ± 0.07 (WT) and 0.78 ± 0.06 (DBZ KO) at 8 μm (p = 0.001); 0.98 ± 0.06 (WT) and 0.78 ± 0.06 (DBZ KO) at 9 μm (p = 0.035); 0.99 ± 0.06 (WT), and 0.71 ± 0.06 (DBZ KO) at 10 μm (p = 0.001; Fig. 10E,F).

This failure of Lis1 transport was also observed in neurons with the phosphorylated mimetic form of Ndel1 (n = 20, Welch's t test). The relative fluorescence intensities of Lis1 were as follows: 1.74 ± 0.16 (control) and 1.44 ± 0.08 (T219E:S251E Ndel1) at 5 μm from the tip (p = 0.027); 1.54 ± 0.11 (control) and 1.28 ± 0.08 (T219E:S251E Ndel1) at 6 μm (p = 0.049; Fig. 10G,H).

Inhibition of GSK3β activity is crucial for neurite extension and microtubule growth at the distal tip (Yoshimura et al., 2005; Arimura et al., 2009), and GSK3β activity is suppressed by local DISC1. Therefore, we assessed GSK3β activity in the presence or absence of DBZ. If smaller amounts of DISC1 are transported distally, then GSK3β activity is likely to be enhanced. Indeed, 100 nm of the GSK3β inhibitor 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime rescued the poor neurite extension caused by DBZ insufficiency (n = 15, Welch's t test): 246.2 ± 15.4 μm (DBZ RNAi) and 289.3 ± 23.1 μm (DBZ RNAi + GSK3β inhibitor; p = 0.033; Fig. 10I).

Discussion

In the present study, we elucidated the importance of DBZ in cell positioning and neurite development in vivo and its underlying mechanisms (Fig. 11). Although DBZ is capable of regulating cell proliferation in vitro, the total numbers of CldU and IdU were not significantly different between the DBZ−/− mice and their wild-type littermates. Therefore, it is unlikely that DBZ plays a major role in the production of neurons in the cortex. The limited localization of DBZ, of which mRNA was expressed primarily in the intermediate zone but not in the ventricular zone, where most neurons are generated from the apical progenitors, is one plausible explanation for the function of DBZ in the cortex. Notably, another dividing population in the cortex, such as intermediate progenitors in the subventricular zone, did not exhibit much difference in terms of its proliferation, based on our Ki67 results. Because we do not have an antibody against DBZ adequate for use with immunohistochemistry, the localization of DBZ in the individual intermediate progenitors has not been elucidated.

Figure 11.

Cell biological aspects of DBZ activities. DBZ+/+ (top) and DBZ−/− (bottom). In the absence of DBZ, Ndel1 was disproportionately phosphorylated in a neuron, leading to poor transportation of DISC1 and Lis1 to the neurite ends. DISC1 suppresses GSK3β activity, which inhibits neurite extension. If insufficient amounts of DISC1 are transported, then neurites do not fully elongated. Anterogradely transported Lis1 is then retrogradely transported and plays a critical role in neuronal migration in an amount-dependent manner.

Dual phosphorylation of Ndel1 at threonine 219 and serine 251 was enhanced in the absence of DBZ. This dual phosphorylation altered the interaction between microtubules and centrosomes and hampered the anterograde transport of the DISC1-Lis1-Ndel1 complex. It has been shown that Ndel1 activity is controlled by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of Ndel1 serine 251 by Aurora A has been demonstrated to be crucial for regulating microtubule organization during neurite extension (Mori et al., 2009; Takitoh et al., 2012). It has also been shown that Cdk1 and Cdk5 regulate Ndel1 activity by phosphorylating threonine 219 (Niethammer et al., 2000; Toyo-Oka et al., 2008). However, in this study, we found that dual phosphorylation of Ndel1 impaired neurite extension; suggesting that threonine 219 phosphorylation and serine 251 phosphorylation are sequestered events in vivo. Thus, in a sense, DBZ probably acts as a guardian against excessive Ndel1 phosphorylation. This is consistent with our finding that the mimetics of dual-phosphorylated Ndel1 exhibited impaired cell division, suggesting that proper centrosome function was disrupted. The fact that the nucleus-centrosome distance was elongated in DBZ-insufficient neurons indicates that Ndel1 activity deteriorated in the absence of DBZ. Because Ndel1 adopts a sharply bent back structure (Soares et al., 2012), it is possible that DBZ, which binds to the C-terminal domain of Ndel1, hinders the access of Aurora A and cdk5 to Ndel1.

The loss of DBZ resulted in poor extension of neurites. This phenotype was rescued by GSK3β inhibition, suggesting that GSK3β activity was altered in the absence of DBZ. Because DISC1 helps neurites extend by inhibiting GSK3β at the distal ends (Yoshimura et al., 2005; Arimura et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2009), one plausible explanation underlying this function of DBZ is that DISC1 is not transported to the distal ends in sufficient quantities to inhibit GSK3β activity in the absence of DBZ. Indeed, a GSK3β inhibitor rescued poor neurite extension due to acute DBZ insufficiency. It has been reported that GSK3β regulates dendritic growth (Rui et al., 2013); therefore, it is plausible that poor development of dendrites in the P3 DBZ−/− mice, as shown by Golgi-Cox staining, is due to low GSK3β activity. Additionally, our FRAP analysis suggested that the DISC1 transport speed was not altered by DBZ deficiency. Therefore, it is likely that the activity of KIF5, which is contained in the complex and acts as a motor cargo for transport, is independent of Ndel1 phosphorylation.

In our study, only Bin 6 showed the difference in terms of the CldU index at P2. Although the subtype of affected neurons remains unclear, it is possible that retarded migration due to DBZ deletion resulted in this difference at P2. In this study, we demonstrated that DBZ regulates the anterograde transport of Lis1. Although retrogradely transported from the distal ends, Lis1 plays a crucial role in pulling the nucleus toward the direction of migration, which is important for radial migration (Shu et al., 2004). Additionally, a certain amount of Lis1 is critical for radial migration; the Lis1+/− mouse exhibits severe migration defects, and a heterozygous mutation of the Lis1 gene results in lissencephaly in humans (Reiner et al., 1993; Hirotsune et al., 1998). Thus, a minimal or appropriate amount of Lis1 should be anterogradely transported to the distal ends before retrograde transport. Therefore, it is likely that such perturbed anterograde transport of Lis1 leads to the impairment of radial migration. Indeed, smaller amounts of Lis1 were observed in the neurite tips of the DBZ−/− mice, and nucleus-centrosome decoupling, one indication of Lis1-nucleus malfunction, was observed under DBZ-deficient conditions.

An excess of DISC1 accelerated the radial migration but did not alter the distance between the nucleus-centrosome, suggesting that DISC1 may play a role for radial migration independent of Lis1. Then, we could not exclude the possibility that the migration defects due to the acute insufficiency of DBZ or the overexpression of phosphorylation mimetic form of Ndel1 were rescued by this DISC1 activity. Anyhow, it is likely that the optimal amount of DISC1 is important for the proper radial migration.

Interestingly, an acute insufficiency of DBZ due to RNAi apparently resulted in more severe phenotypes of radial migration than the DBZ−/− mice. In addition to the fact that knockdown induces an insufficiency that is abrupt compared with the knock-outs, it should be noted that knockdown neurons are surrounded by intact neurons, which made it easy for us to observe the abnormal behavior of the knockdown neurons, whereas DBZ is deleted in all neurons in the knock-out mice, causing these neurons to behave similarly. Recently, it is shown that the off-target effects of some shRNAs alter the radial migration, warning the reckless usage of shRNAs for the studies on radial migration (Baek et al., 2014). We have been cautious of applying shRNAs (Iguchi et al., 2012), and in this study, we drew our major conclusions with the DBZ−/− mice.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Multidisciplinary Program for Elucidating Brain Development from Molecules to Social Behavior (Fukui Brain Project), the Project Allocation Fund of the University of Fukui, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Neural Diversity and Neocortical Organization” and the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences “Integrated research on neuropsychiatric disorders” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. We thank T. Bando, H. Yoshikawa and S. Kanae for technical assistance, T. Taniguchi for secretarial assistance, J. Miyazaki for the pCAGGS vector, and J. Y. Yu and D. L. Turner for the mU6pro vector.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Arimura N, Kimura T, Nakamuta S, Taya S, Funahashi Y, Hattori A, Shimada A, Ménager C, Kawabata S, Fujii K, Iwamatsu A, Segal RA, Fukuda M, Kaibuchi K. Anterograde transport of TrkB in axons is mediated by direct interaction with Slp1 and Rab27. Dev Cell. 2009;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek ST, Kerjan G, Bielas SL, Lee JE, Fenstermaker AG, Novarino G, Gleeson JG. Off-target effect of doublecortin family shRNA on neuronal migration associated with endogenous microRNA dysregulation. Neuron. 2014;82:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S, Altman J. Neocortical development. New York: Raven; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon NJ, Sawa A. Linking neurodevelopmental and synaptic theories of mental illness through DISC1. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:707–722. doi: 10.1038/nrn3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon NJ, Millar JK, Korth C, Sive H, Singh KK, Sawa A. Understanding the role of DISC1 in psychiatric disease and during normal development. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12768–12775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3355-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Hennah W, van Erp TG, Thompson PM, Lonnqvist J, Huttunen M, Gasperoni T, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Pirkola T, Toga AW, Kaprio J, Mazziotta J, Peltonen L. Association of DISC1/TRAX haplotypes with schizophrenia, reduced prefrontal gray matter, and impaired short- and long-term memory. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1205–1213. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:36–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubelos B, Sebastián-Serrano A, Beccari L, Calcagnotto ME, Cisneros E, Kim S, Dopazo A, Alvarez-Dolado M, Redondo JM, Bovolenta P, Walsh CA, Nieto M. Cux1 and Cux2 regulate dendritic branching, spine morphology, and synapses of the upper layer neurons of the cortex. Neuron. 2010;66:523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco F, Esposito T, Ombra MN, Forabosco P, Maninchedda G, Fattorini M, Casula S, Vaccargiu S, Casu G, Cardia F, Deiana I, Melis P, Falchi M, Pirastu M. Identification of a novel gene and a common variant associated with uric acid nephrolithiasis in a Sardinian genetic isolate. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1479–1491. doi: 10.1086/375628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabham PW, Seale GE, Bennecib M, Goldberg DJ, Vallee RB. Cytoplasmic dynein and LIS1 are required for microtubule advance during growth cone remodeling and fast axonal outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5823–5834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T, Baba K, Matsuzaki S, Honda A, Miyoshi K, Inoue K, Taniguchi M, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Baba A, Shimizu S, Yukioka F, Kumamoto N, Yamaguchi A, Tohyama M, Katayama T. A novel DISC1-interacting partner DISC1-binding zinc-finger protein: implication in the modulation of DISC1-dependent neurite outgrowth. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:398–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirohashi Y, Wang Q, Liu Q, Li B, Du X, Zhang H, Furuuchi K, Masuda K, Sato N, Greene MI. Centrosomal proteins Nde1 and Su48 form a complex regulated by phosphorylation. Oncogene. 2006;25:6048–6055. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S, Fleck MW, Gambello MJ, Bix GJ, Chen A, Clark GD, Ledbetter DH, McBain CJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Graded reduction of Pafah1b1 (Lis1) activity results in neuronal migration defects and early embryonic lethality. Nat Genet. 1998;19:333–339. doi: 10.1038/1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson CA, Goldman D, Jaeger J, Persaud S, Kane JM, Lipsky RH, Malhotra AK. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1): association with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:862–872. doi: 10.1086/425586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi T, Yagi H, Wang CC, Sato M. A tightly controlled conditional knockdown system using the Tol2 transposon-mediated technique. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka K, Paek M, Kamiya A, Sawa A. A review of disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 (DISC1): neurodevelopment, cognition, and mental conditions. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka K, Kamiya A, Oh EC, Kanki H, Seshadri S, Robinson JF, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Kubo K, Furukori K, Huang B, Zeledon M, Hayashi-Takagi A, Okano H, Nakajima K, Houslay MD, Katsanis N, Sawa A. DISC1-dependent switch from progenitor proliferation to migration in the developing cortex. Nature. 2011;473:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature09859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kubo K, Tomoda T, Takaki M, Youn R, Ozeki Y, Sawamura N, Park U, Kudo C, Okawa M, Ross CA, Hatten ME, Nakajima K, Sawa A. A schizophrenia-associated mutation of DISC1 perturbs cerebral cortex development. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1167–1178. doi: 10.1038/ncb1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishiro Y, Kagawa M, Naito I, Sado Y. A novel method of preparing rat-monoclonal antibody-producing hybridomas by using rat medial iliac lymph node cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1995;20:151–156. doi: 10.1247/csf.20.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komada M, Saitsu H, Kinboshi M, Miura T, Shiota K, Ishibashi M. Hedgehog signaling is involved in development of the neocortex. Development. 2008;135:2717–2727. doi: 10.1242/dev.015891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y, Fujiwara T, Kubo T, Tomita K, Yano K, Hosokawa K, Tohyama M. Reduction of oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein expression following facial nerve transection. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;36:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y, Hattori T, Shimizu S, Taniguchi M, Yamada K, Takamura H, Kumamoto N, Matsuzaki S, Ito A, Katayama T, Tohyama M. DBZ (DISC1-binding zinc finger protein)-deficient mice display abnormalities in basket cells in the somatosensory cortices. J Chem Neuroanat. 2013;53:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Yamada S, Tanaka M, Iizuka M, Yano H, Mori D, Tsuboi D, Nishioka T, Namba T, Iizuka Y, Kubota S, Nagai T, Ibi D, Wang R, Enomoto A, Isotani-Sakakibara M, Asai N, Kimura K, Kiyonari H, Abe T, et al. Behavioral alterations associated with targeted disruption of exons 2 and 3 of the Disc1 gene in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4666–4683. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz JH, Schuchardt I, Straube A, Steinberg G. A dynein loading zone for retrograde endosome motility at microtubule plus-ends. EMBO J. 2006;25:2275–2286. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie S, Millar JK, Porteous DJ. Role of DISC1 in neural development and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, Madison JM, Koehler AN, Doud MK, Tassa C, Berry EM, Soda T, Singh KK, Biechele T, Petryshen TL, Moon RT, Haggarty SJ, Tsai LH. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136:1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O, Valiente M, Ge X, Tsai LH. Guiding neuronal cell migrations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001834. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Honda A, Baba K, Taniguchi M, Oono K, Fujita T, Kuroda S, Katayama T, Tohyama M. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1, a candidate gene for schizophrenia, participates in neurite outgrowth. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:685–694. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori D, Yano Y, Toyo-oka K, Yoshida N, Yamada M, Muramatsu M, Zhang D, Saya H, Toyoshima YY, Kinoshita K, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S. NDEL1 phosphorylation by aurora-A kinase is essential for centrosomal maturation, separation, and TACC3 recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:352–367. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori D, Yamada M, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shirai Y, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Saya H, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S. An essential role of the aPKC-aurora A-NDEL1 pathway in neurite elongation by modulation of microtubule dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/ncb1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer M, Smith DS, Ayala R, Peng J, Ko J, Lee MS, Morabito M, Tsai LH. NUDEL is a novel Cdk5 substrate that associates with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein. Neuron. 2000;28:697–711. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Kamiya A, Murai R, Kubo K, Gruber AJ, Tomita K, Lu L, Tomisato S, Jaaro-Peled H, Seshadri S, Hiyama H, Huang B, Kohda K, Noda Y, O'Donnell P, Nakajima K, Sawa A, Nabeshima T. Knockdown of DISC1 by in utero gene transfer disturbs postnatal dopaminergic maturation in the frontal cortex and leads to adult behavioral deficits. Neuron. 2010;65:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor SC, Martínez-Cerdeño V, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR. Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:136–144. doi: 10.1038/nn1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki Y, Tomoda T, Kleiderlein J, Kamiya A, Bord L, Fujii K, Okawa M, Yamada N, Hatten ME, Snyder SH, Ross CA, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 (DISC-1): mutant truncation prevents binding to NudE-like (NUDEL) and inhibits neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:289–294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduri A, Evrony GD, Cai X, Walsh CA. Somatic mutation, genomic variation, and neurological disease. Science. 2013;341:1237758. doi: 10.1126/science.1237758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Principles of neural cell migration. Experientia. 1990;46:882–891. doi: 10.1007/BF01939380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O, Carrozzo R, Shen Y, Wehnert M, Faustinella F, Dobyns WB, Caskey CT, Ledbetter DH. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein beta-subunit-like repeats. Nature. 1993;364:717–721. doi: 10.1038/364717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, Anderson S, Shi L, Miyashita-Lin E, Bulfone A, Hevner R. Genetic control of cortical regionalization and connectivity. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:524–532. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Y, Myers KR, Yu K, Wise A, De Blas AL, Hartzell HC, Zheng JQ. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and maintenance by glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2628. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Nakatsuji N. Efficient gene transfer into the embryonic mouse brain using in vivo electroporation. Dev Biol. 2001;240:237–246. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]