ABSTRACT

Although varicella is usually a mild and self-limited disease, complications can occur. In 1998, the World Health Organization recommended varicella vaccination for countries where the disease has a significant public health burden. Nonetheless, concerns about a shift in the disease to older groups, an increase in herpes zoster in the elderly and cost-effectiveness led many countries to postpone universal varicella vaccine introduction. In this review, we summarize the accumulating evidence, available mostly from high and middle-income countries supporting a high impact of universal vaccination in reductions of the incidence of the disease and hospitalizations and its cost-effectiveness. We have also observed the effect of herd immunity and noted that there is no definitive and consistent association between vaccination and the increase in herpes zoster incidence in the elderly.

Keywords: Chickenpox, Varicella Zoster Virus, Chickenpox Vaccine, Immunization Programs, Herpes Zoster

Introduction

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is known to cause varicella, a common and usually mild illness in childhood. However, complications such as encephalitis, pneumonitis and secondary bacterial infections may occur, resulting in hospitalization and deaths.1 In 2014, World Health Organization (WHO) estimated approximately 4.2 million of varicella cases with severe complications and around 4200 related deaths occurring per year in the world.2 Humans are the only reservoir of Varicella-Zoster virus, and transmission is highly effective. A secondary attack rate higher than 70% has been described in unvaccinated groups.3 Similar to many other infectious diseases, active immunization is considered one of the main preventive interventions for varicella. The WHO recommends universal vaccination in places where varicella is a public health problem. However, resources should be sufficient to ensure reaching and sustaining high vaccine coverage (≥80%).2

Varicella Vaccine (VV), a live-attenuated viral vaccine, was first developed in Japan in the early 1970s (Oka strain).4,5 Several licensed formulations of live attenuated vaccines are currently available, as monovalent or combined with measles, mumps and rubella.2 After a single dose of VV, effectiveness against all forms of diseaseis around 76% to 85% and reaches up to 100% after two doses.6 The efficacy for hospitalization reduction is higher than 95% in most of studies.7–10 Long-term protection has been evidenced by both through the persistence of antibodies and efficacy higher than 90% up to ten years.11,12

Despite consistent data about immunogenicity and vaccine effectiveness (VE), some questions about the introduction of universal VV do exist. The number of countries with universal VV is growing and the knowledge about the impact in “a-real-world-scenario” among vaccinated populations is being continuously published. It has been hypothesized that a shift in the incidence to older ages groups could happen, which may be associated with a higher incidence of complications. Moreover, an increase in the incidence of herpes zoster (HZ) in the elderly individuals was also hypothesized, due to the lack of a natural boost of immunity through repeated contact with infected persons. Finally, cost-effectiveness is also an important point to be addressed.13

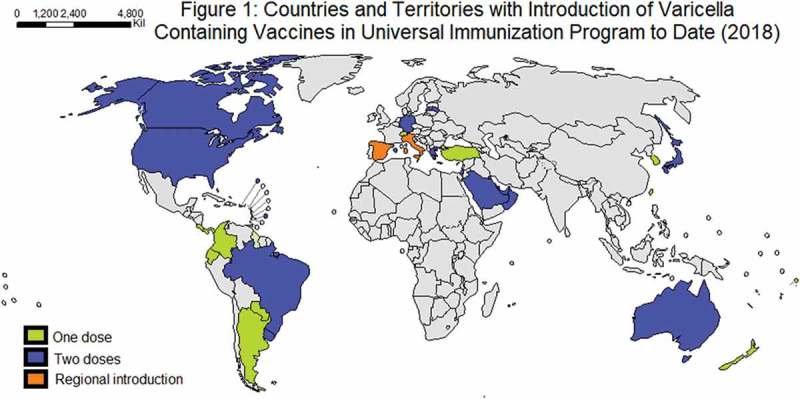

Currently, 36 countries and regions have introduced universal VV (Figure 1; Table 1), but many of these countries have no data about the impact. The aim of this article was to review the growing body of evidence about the impact of universal VV programs in epidemiology and disease related outcomes, as well as the effect on HZ in the elderly, herd immunity and cost-effectiveness.

Table 1.

| Americas | Country | Vaccine | Funded dosis | 1st and 2nd dose introduction (year) | Schedule (1st; 2nd dose) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Varicella | 1 | 2015 | 15 m; | |

| Bahamas (the) | Varicella | 2 | 2012 | 12 m; 4–5 y; | |

| Barbados | Varicella | 1 | 2012 | 12 m; | |

| Brazil | MMRV, Varicella | 2 | 2013, 2017 | 15 m; 4 y | |

| Canada | MMRV or Varicella | 2 | 2001, 2012 | 12–15 m;18 m-6 y | |

| Colombia | Varicella | 1 | 2015 | 12 m | |

| Costa Rica | Varicella | 1 | 2007 | 15 m | |

| Ecuador | Varicella | 1 | 2011 | 15 −23 m | |

| Panama | Varicella | 2 | 2013 | 15 m – 4 y; | |

| Paraguay | Varicella | 1 | 2013 | 15 m; | |

| Puerto Rico | Varicella | 2 | 1997 | 12 m; 4–5 y | |

| United States of America (the) | Varicella | 2 | 1995, 2006 | > 12 m; 4 y | |

| Uruguay | Varicella | 2 | 1999 | 12 m; 5 y | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Bahrain | Varicella | 2 | no data | 12 m; 3 y |

| Kuwait | MMRV | 2 | 2017 | 12, 24 m; 12 y | |

| Oman | Varicella | 1 | 2010 | 12 m; | |

| Qatar | Varicella | 2 | 2002 | 12 m; 4–6 y | |

| Saudi Arabia | Varicella | 2 | 1998, mandatory sincce 2008 | 18 m; 6 y | |

| United Arab Emirates (the) | Varicella | 2 | 2012 | 12 m; 5–6 y | |

| Europe | Andorra | Varicella | 2 | no data | 15 m; 3 y |

| Finland | Varicella | 2 | 2017 | 18 m; 6 y | |

| Germany | MMRV, Varicella | 2 | 2004, 2009 | 11–14 m;15–23 m | |

| Greece | MMRV, Varicella | 2 | 2006, 2009 | 12–15 m; 4–6 y | |

| Israel | MMRV, Varicella | 2 | 2008 | 12 m; 6 y | |

| Italy | MMRV or Varicella | 2 | 13–15 months; 5–6 years; | ||

| Sicily | 2003 | 2y | |||

| Veneto | 2005 | 15 months, 3y | |||

| Puglia | 2006 | 13 months; 5-6y | |||

| Toscana | 2008 | 13–15 months; 5-6y | |||

| Basilicata | 2010 | 13 months; 6y | |||

| Calabria | 2010 | 13–15 months; 5-6y | |||

| Sardinia | 2011 | 13 months; 6y | |||

| Friuli-Venezia-Giulia | 2013 | 13 months; 6y | |||

| Latvia | Varicella | 1 | 2008 | 12–15 m | |

| Luxembourg | MMRV | 2 | 2010 | 12, 15–23 m | |

| San Marino | Varicella | 2 | no data | 15 m; 10 y | |

| Spain | Varicella | 2 | 2016 | 15 m; 3–4 y | |

| Madrid | Program withdrawn nov/2013 | 2006 | 15 m | ||

| Navarre | 2007 | 15 m, 3y | |||

| Ceuta | 2009 | 18 m, 24 m | |||

| Melila | 2009 | 15 m, 24 m | |||

| Switzerland | Varicella | 1 | no data | 11–15 y; | |

| Turkey | Varicella | 1 | 2013 | 12 m | |

| Western Pacific | Australia | MMRV, Varicella | 2 | 2005 | 18 m; 10–15 y |

| Japan | Varicella | 2 | 2014 | 12; 18 m | |

| New Zealand | Varicella | 1 | 2017 | 15 m | |

| Niue | Varicella | 1 | 2017 | 15 m | |

| Republic of Korea (the) | Varicella | 1 | 2005 | 12–15 m | |

| Taiwan | Varicella | 1 | 2004 | 12–18 m | |

Methods

This is a non-systematic review addressing the impact of universal VV. Countries where VV was universally introduced were detected at WHO website (http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/schedules). The search was performed at PubMed with no limits of date or language, with the name of each country and the words “varicella” OR “varicella vaccine” AND “impact” OR “hospitalization” OR “incidence” OR “herpes zoster”. Where included all studies selected through criteria assessing any outcome of impact, both in vaccinated and non-vaccinated population, as well as impact on HZ epidemiology. For cost-effectiveness, studies were selected through search “varicella vaccine” AND “cost-effectiveness”.

Impact of universal VV by region

a. Americas.

The United States of America was the first country to introduce universal VV and, consequently, it became the country with the longest follow-up. In 1995, the monovalent varicella vaccine was approved in the United States of America by the FDA, and, in the same year, it was introduced as a single-dose routine childhood program. The coverage increased progressively from 27% to 88%, during 1997 to 2005.17 Comparing pre (1993–1995) and post-vaccination (1996–2004), varicella-related ambulatory visits were reduced by 66% (p < 0.001), reaching 98% of reduction in children younger than 4 years.18 Overall rate of hospitalization was 0.4/10000/year before and was reduced to 0.12/10000/year during the one dose era (p < 0.001), with greater reduction in children aged less than 4 years.19 Despite the success in reducing incidence and hospitalization in the vaccinated and non-vaccinated population aged less than 45 years, the occurrence of outbreaks led to the recommendation of a second dose in September 2005.18,19 The quadrivalent vaccine (measles-mumps-rubella-varicella) was licensed by the FDA and, in 2006, the second dose was introduced in routine National Immunization Program.17 This implementation resulted in a decline usually greater than 90% (comparing to pre-vaccination period) in the incidence, hospitalizations and death, with more pronounced impact in children20–22, as well as a reduction in the magnitude and duration of outbreaks.23 The percentages of reduction in the United States and other countries are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Impact of universal varicella vaccination on Varicella incidence.

| Country/ region |

Studies (First author/year) |

Design of studies/Period | Years after introduction and population evaluated (years of age) | Incidence Before VV (cases/100.000/year) | Vaccination coverage | % reduction after 1 dose (CI95%) | % Incidence change after 2 doses (CI95%) from pre-vaccine period | Impact in HZ | Evidence of indirect effect and age** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uruguay | Quian, 200824 | Retrospective (1997–2005) | 6 years, 0–14 years | 105,1 | 88–96% | Medical visits reduction of 87% over all groups (< 15y)(P < 0,001), 97% in 1–4y)(P < 0,001) | # | No data | Incidence reduction 80% in < 1 year (P < 0,001), 81% in 5–9 years (P < 0,001), and 65% in10–14 years (P < 0,001), |

| Costa Rica | Avila-Aguero, 201625 | National database retrospective review (2007–2015) | 8 years, all ages | 301–437 | 76–95% | 79,1% (< 5y), | No data | Incidence reduction of 73,8% (all ages) | |

| Brazil | Andrade, 201826 | Case-control | 5–32 months of age | - | - | VE for any severity: 86% (95% CI 72–92%) VE for moderate/severe disease: 93% (95% CI 82–97%) |

# | No data | |

| Canada | Wormsbecker, 201527 | Retrospective health care administrative data (1992–2011) | 10 years, 0–17 years | 1756,77 (OV) and 158,8 (ED) | Not available | 71% for office visits (p < 0.001), 71% for emergency visits (p < 0.001) | # | Decrease in OV (p < 0.001), increase in ED (p < 0.001) for 5–17 years | Shift to older ages (~ 11 months) for OV |

| U.S.A. Antelope Valley (AV), West Philadelphia (WP) |

Bialek, 201322 | Active surveillance data analyzes (1995–2010) | 9 years, all ages | AV: 1030 WP: 410 |

For one-dose AV: 90.5% to 95.1% WP: 92.7% to 94.6% |

89% in AV (~ 100) 90% in WP (~ 40) |

76.3% in WP (P < 0.001) and 67.1% in AV (P < 0.001) | No data | Decrease of 81.3% (p < 0.001) in individuals > 20 years |

| U.S.A. | Lopez, 201621 | Nationwide rates from passive surveillance data (2005–2014) | 19 years, all ages | No data | No data | 72%, 25.4 per 100,000 population (2005–06) |

84.6% 3.9 per 100,000 (2013–17), (p < 0.001). |

No data | Mild disease was more frequent among vaccinated patients (76.8%) than unvaccinated (23.2%) (p < 0.001). |

| U.S.A. | Baxter, 201428 | Serial cross-sectional survey (1995–2009) | 14 years, 0–29 years of age | 10310 (5–9y) 1940 (10–14y) 1230 (15–19y) |

> 90% for one-dose, 40% for two-dose |

90,2% (5–9y) 72,7% (10–14y) 92,7% (15-19y) |

95,5% (5–9y) 90,7% (10–14y) 94,3% (15-19y) |

No data | No shift to older age group |

| U.S.A. | Leung, 201620 | Retrospective cohort (1994–2012) | 17 years, 0–49 years | 215 (OV) | Not available | 78% | 84% (p = < 0,001) in 1–9 years; | No data | Incidence decline 60% (p = < 0,001) in all ages, O.F. decline 95% in < 1year with 35% reduction during 2nd dose (p = < 0,001); 84% all ages (0–49y) |

| Australia | Kelly, 201429 | Ecologic(1998–2012) | 7 years, all ages | 430 | ~ 83% | 53% in 0–4 years-old (p < 0.05) 47% in 5–9 years-old (p < 0.05) |

- | Grow incidence in < 70 years-old (p < 0.05), no change in those > 70 years-old | Significant decrease for all age groups < 50 years (p < 0.01), ≥ 50 years (p = 0.02) |

| Taiwan | Chang, 201114 | National health insurance database (2000–2008) | 4 years, < 20 years | 6600 in 4–5 years-old | 93–97% | Significant reduction in individuals < 7 years (p < 0.01); | - | No data | Shift to older ages (p < 0.001) |

| Taiwan | Chao, 201230 | National health insurance database (2000–2008) | 4 years, all ages | 829 | > 90% | 56% in 0–4 years-old | - | Increase,but it was not vaccine attributed | 29% decline in those > 20 years-old |

| Saudi Arabia | Al-Tawfiq, 201331 | Retrospective health insurance database (1994–2011) | 3 years, all ages | 739.8 | No data | - | 60% in 1–4 years (p < 0.0001) | No data | Reduction of incidence in < 1 year-old (p < 0.0001), and all ages (p < 0.0001) The peak age shif from < 5 years to 5–9 years |

| Italy (Veneto) | Pozza, 201132 | Ecologic (2000–2008) | 4 years, all ages | All ages: 289.2–325.6 (all ages) 0–14 years-old: 1939.3–2211.4 (RDP system), 6136.8–7712.7 (SPES system) |

78.6% in 2008 | - | Reduction in individuals between 0–14 years-old: 28.6% (RDP system) 34,7% (SPES system) |

Not available | |

| Italy | Bechini, 201533 | Ecologic (2003–2012) | 9 years, not informed | 130–218 | 84%-95% | - | 75.3% | No data | |

| Italy (Sicily) |

Amodio, 201534 | Regional administrative/clinical data (2003–2012) | 10 years, all ages | 110 | ~ 85% | 90% | 95% (p < 0.001). | No data | |

| Germany (Bavaria) | Streng, 201335 | Population based surveillance (2006–2011) | 7 years, < 17 years | 660 (95%CI 610–700) in 2006–2007, two years after vaccine introduction | 1st dose 38–68%, 2nd dose 59% | 65.2% (95%CI 200–260) in 2009–2010 | 67%(95%CI 190–250) (< 17 years) | No data | 71% decrease in children beloow 1 years of age, and 63% in older children and adolecents. |

| Germany | Rieck, 201736 | Health Insurance based study (2006–2015) | 11 years, - | Not available | > 80% | VE of 81.9% (95% CI: 81.4–82.5), |

VE of 94.4% (95% CI: 94.2–94.6) | No data | No association of VE with vaccination age, time since vaccination, or vaccine type. Unvaccinated individual had benefit from herd immunity |

| Spain (Navarra) | Cenoz, 201137 | Regional population data information (2006–2010) | 3 years, all ages | 804 | 88% one-doe 81% two-doses |

- | 96.3% in 1–6 years of age 96.3% in 10–14 years of age 85% in 15-19 years (vaccinated individuals) |

No data | 93% (p < 0,0001) in all ages Decline in no vaccinated groups of 88.2% (< 1 year), 73.3% (7–9 years) and 84.6% (> 20 years) |

| Spain (Navarra) | Cenoz, 201338 | Cohort (2006–2012) | 5 years, all ages | 804 (all ages) 5010 (0–14 years) |

95% one-doe 89% two-dose |

VE 96.8% (95% CI: 96.3–97.2%) | 98.5% (p < 0.0001) in the vaccinated cohort Incidence decrease 97.3% in all ages (p < 0.0001) |

No data | Significant herd protection among < 1 year, 22–44 years (p < 0.0001) and 45–64 years (p = 0.0015) Shift from 3 years-old to two peaks in individuals < 15 months and 9 years-old |

| Spain (Navarra) | Cenoz, 201339 | Case-control (2010–2012) | 5 years, 15 months to 10 years of age | - | 95% one-dose 89% two-dose |

87% (95% CI: 60% – 97%) (p < 0.001) | 97% (95% CI: 80% −100%) (p < 0.001) | No data | |

| Spain (Madrid) | Latasa, 201840 | Population-based follow-up (2001–2015) | 7 years (vaccine available between Nov 2006 and Jan 2014), all ages | 8439.61 (0–4 years) 2906.96 (5–9 years) 672.79 (10–14 years) 114.53 (> 14 years) |

> 90% | 95.8% RR 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) (0–4 years) 78.6% RR 0.21 (0.18 to 0.25) (5–9 years) |

- | No data | VE of 93.1% (95% CI: 90.9 to 94.8) Incidence decrease: 80.1% RR 0.20 (0.14 to 0.29) (10–14 years) and 80.4% RR 0.20 (0.15 to 0.25) (> 14 years) |

| Spain (Madrid) |

Comas, 201841 | Observational descriptive (2001–2015) | 7 years (vaccine available between Nov 2006 and Jan 2014), all ages | 1494.29 (all ages) 8792.65 (0–4 years) 3354.38 (5–9 years) 751.27 (10–14 years) 128.24 (> 14 years) |

93,7% | 88.9% RR (IC 95%: 0,09–0,13) (0–4 years) 76% RR IC 95%: 0,20–0,29) (5–9 years) |

- | Incidence reduction of 94% RR (IC 95%): 0,05–0,07 (all ages), 61% RR (IC 95%): 0,28–0,54 (10–14 years) 88.8% (IC 95%: 0,06–0,19) (> 14 years) |

|

| Europe (Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia and Sweden) |

Henry, 201842 | Multicenter phase A cohort, observer-blind, controlled Study (2009–2015) |

6.4 years, included children aged 12–22 months | - | - | VE 67.0% (95% CI: 61.8–71.4) for all and moderate cases VE 90.3% (95% CI: 86.9–92.8) for severe cases |

VE 95.0% (95% CI: 93.6–96.2) for moderate cases VE: 99.0% (95% CI: 97.7–99.6) for severe cases |

Four confirmedcases, all mild and three positive for wild-type virus | 96.6% to 99.8% seropositivity after 6 years of vaccination |

*Comparing with pre-vaccination period.** Limit of age where effect was found #implemented after the study period

ED = emergency department; OV = Office visits, VE = vaccine effectiveness; CI = confident interval; U.S.A. = (The) United States of America, HZ = herpes-zoster

Table 3.

Impact of universal varicella vaccination on hospitalization due to Varicella.

| Country/region | Studies (First author/year) |

Design of studies/Period | Years after introduction and population evaluated (years of age) | Incidence of hospitalizations due to Varicella Before Universal VV (rate per100.000) | Vaccination coverage | % Change on incidence after one-dose | % Change on incidence after two-doses from pre-vaccine period | Impact in HZ | Evidence of indirect effect and age** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uruguay | Quian, 200824 | Retrospective (1997–2005) | 6 years, < 15 years | 101 total cases in 1998 | 88–96% | 81% all ages (p < 0,001) 94% in 1–4y (p < 0,001) 73% in 5-9y (p < 0,001) |

# | No data | Hospitalization reduced by 63% in < 1 year (p < 0.001), 62% in 10–14 years (p = 0.044) |

| Brazil | Scotta, 201843 | Ecologic (2003–2016) | 3 years, < 20 years | 27,33 | 60% | 47.6% (p < 0.001) in 1–4 years | # | No data | Not significant in other age groups |

| Costa Rica | Avila-Aguero, 201725 | National database retrospective review (2007–2015) | 8 years, all ages | ~ 100–160 | 76–95% | 85,9% (all ages), 87% (< 5y) | # | No data | 98% less cases complication |

| U.S.A. | Shah, 201018 | National health care survey data (1993–2004) | 9 years, < 45 years | 30.9 | No data | 53%, (P < 0.001) in < 14 years |

# | No data | 65.8% reduction in ambulatory discharges (p < 0.001) < 45 years, 98% reduction among 0–4 years |

| U.S.A. | Lopez, 201119 | National health care survey data (1988–1995 vs 2000–2006) | 11 years, all ages | 4,2 | ≥ 65% (89% in 2006) | > 70% (p < 0,001) in those < 20 years | # | No data | ~ 65% hospitalization reduction in those > 20 years, p < 0,001 |

| U.S.A. | Baxter, 201428 | Cross-Sectional Series (1995–2009) | 14 years, 0–29 years | 2,13 | > 90%, 40% for 2nd dose |

77,1% | ~ 90% | No data | Annual decreased in all ages of 13% (p < 0.001) |

| U.S.A. | Leung, 201620 | Retrospective cohort (1994–2012) | 17 years, 0–49 years | 2,35 | No data | 89% (p < 0.001) | 99% for infants < 1 years, and 86–96¨% (p = < 0.001), in all ages | No data | Additional 10% decline for those 20–49 years-old during the 2-dose period |

| Canadá (Ontario) | Wormsbecker, 201527 | Retrospective health care administrative data analyzes (1992–2011) | 10 years, 0–17 years | 7,6 (< 1 year) |

Not available | 59% (95%CI: 0.10-1.69) | # | No change (< 18year) | Decrease in ICU admissions in < 1 year (p < 0.05), 69% decline in SSTI among < 12 years (p < 0.001) |

| Australia | Carville, 201044 | Ecologic (1995–2007) | 8 years privately available and 2 years funded, all ages | 4 (all ages) 21 (0–4 years) 7.7 (5-9 years) |

69% private available 98–102% publicly available |

38% (p < 0.05) in 0–4 years-old | - | 5% increase per years (95% CI 3–6%) in HZ hospitalization in all ages | 22.5% less hospitalization in all ages (p < 0.05) |

| Australia | Heywood, 201445 | Ecologic (1998–2010) | 4 years of funded vaccination, all ages | ~ 30 in 18–59 months | > 80% | 72.5% (95% CI: 68.8–75.7) in 1–4 years-old | - | HZ hospitalization decline 0.57% (95% CI: 0.24–0.91) per year, age-standardized | Significant Decline in < 40 years (p < 0.001) And 62,1% (95% CI: 54.7–68.3) in individuals < 1 year |

| Taiwan | Chang, 201114 | National heal insurance database (2000–2008) | 4 years, < 20 years | ~ 80 in < 1 year ~ 65 in < 6 years |

93–97% | Significant decrease in individuals < 6 years (p < 0.01) | - | No data | |

| Israel | Elbaz, 201646 | Retrospective chart review (2004–2012) | 4 years, ≤ 18 years | 389 (≤ 18 years) 1100 (1–6 years) |

Not available | - | 75% decline in individuals 1–6 years, (p < 0.001) | Decline 63% (p < 0.5) in < 18 years | |

| Spain (Navarra) | Cenoz, 201137 | Regional population data information (2006–2010) | 3 years, all ages | 25 total cases | 88% one-dose 81% two-doses |

- | 73% (p < 0.0001) | No data | Complicated hospitalizations were 40% in 2006 and 42.9% in 2009 |

| Spain (Navarra) | Cenoz, 201338 | Cohort (2006–2010) | 5 years, all ages | 4.2 (all ages) 20.9 (< 15 years) |

95% for one-doe 89% fro two-dose |

- | 95% (p < 0.0001) in individuals < 15 years | No data | 89% (p < 0.0001) in all ages |

| Spain (Madrid) | Latasa, 201840 | Population-based follow-up (2001–2015) | 7 years (vaccine available between november 2006 and January 2014), all ages | 60.91 (0–4 years) 10.36 (5-9 years) 2.59 (10–14 years) 2.57 (> 14 years) |

> 90% | 93.7% RR, RR (CI 95%): 0.05–0.09 (0-4 years) 76.4% RR, RR (CI 95%): 0.15–0.36 (5-9 years) |

- | No data | Incidence decrease (not vaccinated):83.0%, RR (CI 95%): 0.06–0.48 (10-14 years) 69.6%, RR (CI 95%): 0.25–0.37 (> 14 years) |

| Spain (Madrid) | Comas, 201841 | Observational descriptive (2001–2015) | 7 years (vaccine available Nov 2006 to Jan 2014), all ages | 5,99 all ages | 93.7% | 80.8% (RR CI 95%: 0,16–0,23) | - | No data | 80.4% decline among individuals < 1 year, RR (CI 95%): 0,09–0,37 |

| Italy (Veneto) | Pozza, 201132 | Ecologic (2000–2008) | 4 years, all ages | 4.1 (all ages) 18.7 (0-14 years-old) 44.3 (1-4 years-old) |

78.6% | - | 73.6% (1-4 years-old), informed as statistically significant | Not available | 55.1% (0-14 years) |

| Italy | Bechini, 201533 | Ecologic, (2003–2012) | 9 years, not informed | 3.0–3.8 | 84%–95% | - | ~ 75% | No data | Hospitalization costs reduction per region Apulia (86%), Sicily (83%), Tuscany (77%), Veneto (75%), Basilicata (71%), Friuli Venezia Giulia (10%) |

| Italy (Sicily) | Amodio, 201534 | Regional administrative/clinical data (2003–2012) | 10 years, all ages | 4.8 | ~ 85% | 62.5% | 83.3% (p < 0.001) | ||

| Germany (Bavaria) | Streng, 201335 | Population based surveillance (2006–2011) | 7 years, < 17 years | 7.6–12.1 (< 17 years) 15.2–21.0 (< 5 years) 60.8 (< 1 year) |

1st dose 38–68%, 2nd dose 59% | - | 43% (< 17 years) 78% (< 5 years) 76.6% (< 1 year) |

No data | Incidence hospitalization decline 76.6% in non-vaccinated group < 1 years-old (2005 vs 2009) |

*Comparing with pre-vaccination period.** Limit of age where effect was found #implemented after the study period

SSTI = skin and soft tissue infection; CI = confident interval; U.S.A. = (The) United States of America, ICU = Intensive care unit, HZ = herpes-zoster

In Canada, a public-funded single dose VV at 12–15 months of age was introduced gradually through different provinces and territories during 2000–2007. A reduction of 70% in the hospitalization rates across all age groups was shown, with a higher impact in children aged between one and four years (from 65 to 93%).47 Within this same age range, another study on active surveillance in twelve centers found similar results, a decline (90%) in hospitalization rates.48 The proportion of HZ was reported to be lower, from 8.6% to 3.8%, in children younger than 10 years after implementation of VV program in Alberta.49

In Latin America, eleven countries have introduced universal vaccination by 2018, where most countries have adopted a single-dose regime during the second year of life. However, data about the impact are available only from three countries: Uruguay, Costa Rica and Brazil.50 In 1999, Uruguay was the first country in Latin America to introduce universal VV. Six years after the implementation leads to a reduction of 81% in the proportion of varicella related hospitalizations and 87% of outpatient visits in the vaccinated age-groups was observed. Further, in children aged between one to four years, the proportion of hospitalizations were reduced by 94% with a single dose.24 Costa Rica reported a decrease of 79.1% in notified cases, and of 87% in hospitalization in children under five years of age, seven years after the introduction, and achieved coverage up to 95% in 2015.25

The largest country in Latin America, Brazil, recorded more than 16000 hospitalizations in children aged 1–4 years during the six years before VV introduction. Related deaths reached 2334 between 1996 and 2011, which included mortality in infants < 1 year and in children between 1–4 years of 0.88 and 0.40 deaths/100,000/year, respectively.51 One dose VV at 15 months was introduced in 2013 in Brazilian funded NIP. A study based on nationwide database reported that in the vaccinated age group (1–4 years), the hospital admission incidence of varicella and herpes zoster decreased from 27.33 to 14.33 per 100000 people per year, a reduction of 47.6% in hospitalizations three years after introduction. There was a direct saving costs decrease 37.91% with a single dose three years after public vaccine implementation.43 Another recent study, a prospective matched case-control study in two state capitals (São Paulo and Goiânia) reported 86% effectiveness against the disease of any severity and 93% against moderate and severe disease. Interestingly, 22% of the 168 cases occurred in vaccinated children and these patients had milder disease than non-vaccinated ones.26

b. Europe.

Before VV introduction, Europe estimated to account for more than five million cases per year, leading to more than three million primary care consultations per year, nearly 20,000 hospitalizations per year, and up to 80 to death per year (95% CI: 19–822). Besides this, around 60% of the cases were observed in children under five years of age (95% CI: 2.7–3.3).52 Annual reported incidence per 100,000 population varied from western (France, Netherlands, Germany and United Kingdom) southern (Italy, Spain, Portugal) and eastern (Poland, Romania) Europe as 300–1291, 164–1240 and 350, respectively. However, these numbers are much higher among children, accounting from 1,580–12,124/100,000 among 1–4 years of age and 4,400–18,600/100,000 among 0–4 years of age. Hospitalizations and death have a higher incidence in individuals of < 4 years of age.51,53

In Germany, routine VV was introduced in 2004 in children younger than two years and a second dose was recommended in 2009. The results from the German program provide robust data about the impact of VV.54 In a study assessing the period of a single dose (2005 to 2009), complicated varicella, classified as requiring hospitalizations or use the of antimicrobials, was reduced by 81% according to the sentinel surveillance.9 Another similar study during the same period and with similar methods reported a reduction in the number of cases by 63% in children aged 1–4 years and 38% in those aged 5–9 years.55 One single dose schedule reached a reduction of 86.4% (95% CI: 77.3–91.8) in the disease of any severity and 97.7% (95% CI: 90.5–99.4) in moderate to severe cases in children aged 1–7 years.56 In an observational surveillance in Munich area, the varicella cases reduced by 67%, five years after VV introduction, accounting a 43% decrease in the hospitalizations in patients younger than 17 years, which was more pronounced in children younger than five years (78%).35

The studies assessing the period after the second dose introduction have shown an additional benefit. The data from nationwide sentinel surveillance and health insurance claims assessing VE in the overall incidence found a decrease of 86.6% (95% CI: 85.2–87.9) after a single dose and of 97.3% (95% CI: 97.0–97.6) after the second dose in children between 1–4 years until 2014.57 Comparing 2005–2012 versus 1995–2003 data, the incidence of hospitalizations was markedly reduced in all children under nine years, with the greatest reduction in those aged between one and four years (62%, p < 0.05). The admissions due to HZ in adults older than 50 years showed an increasing trend before VV introduction.58 The incidence of neurologic complications also continuously decreases during the first seven years after vaccine introduction.8

The longest analysis in Germany was based on countrywide health insurance claims data and the described VE was 81.9% for one doses (95% CI: 81.4–82.5), two-dose VE, and 94.4% for two dose (95% CI: 94.2–94.6) in children born from 2006 to 2013.36

In Italy, VV was implemented in different regions at different times, thus studies of regional impact has been reported.32,34,59 In a collaborative research summarizing the impact in eight regions that first introduced a two-dose regime, a progressive reduction in the incidence of cases and hospitalization was found after the introduction. The regions that adopted VV earlier, such as Sicily, Veneto, Apulia and Tuscany, showed a higher rate of reduction.33 More recently, the data from Tuscany including four years of introduction revealed a reduction of about 50% in hospitalization, with the greatest effect on children aged 1–4 years, as determined by discharge diagnosis.60

Similarly to Italy, in Spain VV was not introduced as a nationwide universal program but momentarily in different regions. The data from several regions also reinforce the impact in reducing hospitalization in children under five years of age; there is an inverse correlation between vaccine coverage and hospitalization incidence.61,62 In Navarre, the effectiveness of one and two doses for laboratory confirmed cases was 87% (95%CI: 60% to 97%) and 97% (80% to 100%), respectively. However the effectiveness decline after the third year of vaccination.39 In the same region, another study reports an impressive reduction of 98.5% in the disease incidence among the vaccinated children aged up to eight years.38 A recently published study in the community of Madrid reported a single dose vaccine effectiveness of 76.7% (CI 95%: 71.9 to 80.7%) in children aged from 15 months to 13 years.40

In Greece, a retrospective chart review from a single center did not find differences in hospitalizations related to HZ in children younger than 16 years seven years after vaccine introduction.63 In Israel, universal VV was introduced in a two-dose schedule at 12 months and 6–7 years in 2008. In 2009–2012, a retrospective review from three centers reported a reduction of 75% in hospitalizations in children aged 1–6 years, without significant reduction in children aged from 7 to 18 years.46

c. Africa.

There are limited data about varicella in Africa. A systematic review analyzed 20 studies from 13 countries, but there are only three studies reporting varicella incidence that varied from 441 to 3420 cases per 100,000 persons. Varicella vaccination is not routine in any country in Africa, which has limited resources and other competing public health priorities.64,65

d. Oceania.

There are considerable number of studies about the impact of VV in Australia. In a national hospital database study assessing impact, four years after the introduction of universal VV in 2005 (one dose schedule at 18 months and catch-up at 12–13 years), hospitalizations declined by 72.5% in children between 1–4 years and 52.7% in all ages. Importantly, an indirect effect on the non-vaccinated age groups was found, but without an increase in the incidence of HZ in older individuals.45 In the other two reports the overall incidence was reduced in most age groups but an increasing trend in HZ hospitalization was found in older patients.29,44 In a more recently published study, a progressive decline in hospitalizations was reported until 2014, including in non-vaccinated age groups and also with no increase in the elderly.66 Further, the incidence of congenital and neonatal varicella was also reduced, with a significant decrease in 85% neonatal varicella in 2008–2009.67

e. Asia.

Only a few countries from the Asia-Pacific region have introduced universal varicella vaccination.68 Four decades after Japanese scientists developed the varicella vaccine, in November 2014, Japan started universal VV with a two-dose schedule. Till that, VV was offered only on a voluntary basis, approaching 40% of coverage, which was not enough to control the disease transmission.69 The first Japanese study assessing impact after vaccine introduction was a multicenter matched case-control study in children younger than 15 years, which reported an effectiveness of 76% and 94% with one and two doses, respectively.70

In South Korea, a single dose at 15 months of universal VV was introduced in 2005 but results about its effectiveness are not clear. Although no nationwide data about impact are available, two case-control studies observed no significant protection in children younger than 12 years. Interestingly, these studies included children vaccinated with different strains and the majority of patients used a strain that was different from the United States.71,72 However, most of the strains used are considered immunogenic.73 Further, the study design and the way controls were selected could generate a selection bias.

In Taiwan, a single dose universal VV was introduced in 2004 with a high coverage. The analysis of nationwide data has shown a reduction in incidence from 66 cases per 1000 people per year in 2000–2003 to 23 cases per 1000 people per year in 2008, as well as a reduction in hospitalizations in children younger than six years.14 Another retrospective nationwide study assessing effectiveness found a reduction of 82% and 85% on the incidence and hospitalizations, respectively.74 A rise in the incidence of HZ was found in Taiwan. However, it started even before vaccine introduction and cannot be attributed directly as a consequence of universal VV.30

In the Middle-East, many countries have recently introduced VV recently. The impact data on its effect are available from Saudi Arabia, which introduced universal VV in 2008 with a two dose schedule, and a study using health insurance data found an overall 60% reduction in the proportion of disease in children aged between 1–4 years after introduction.31,75

Herd immunity and shift to older age groups

An indirect effect of VV in non-vaccinated age groups has been described in many studies. As herd immunity is more pronounced in age groups closer to the vaccinated group, there are concerns about a shift of the disease to older age groups, which have a higher rate of complications.It is more likely in scenarios with low vaccine coverage (< 80%).76,77 However, this shift has not been confirmed and several studies have reported an overall decrease in the incidence, including among older age groups.18,19,22,45,47,55 Further, an indirect protection has been reported in individuals who are not eligible for live-attenuated immunization and may be at a higher risk of complication, such as children aged less than 1 year, susceptible pregnant and immunocompromised individuals.67,78,79

Changes in epidemiology of herpes zoster

In children and adolescents, VV is associated with a decrease in the incidence of HZ.80–82 Some theoretical models hypothesize an increase in the incidence of HZ in the elderly during some decades due to the lack of natural booster in VZV specific immune response after repeated contact with naturally infected individuals.83 These concerns, as well as the cost-effectiveness, led some countries to opt for no adoption of universal VV, like the United Kingdom. The evidence about this rise is not conclusive. Although some studies have shown an increase in HZ after universal VV was introduced, others did not or even found a reduction.44,45,47,61,84 Moreover, a consistent secular trend of increase in HZ was reported in elder individuals even before universal VV introduction, suggesting that other factors such as the prevalence of chronic diseases or seeking health-care patterns might be involved, though actual reasons are still poorly understood.30,49,58,85,86 Certainly, a longer follow-up is needed to answer these questions. Furthermore, the introduction of HZ can be a complementary approach in the elderly.87,88

Cost-effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness of universal VV has been a matter of debate for many years. Since varicella is commonly a benign disease in childhood, a rise in the incidence of HZ in older people could occur, due to lack of boosting throughout life. Many cost-effectiveness analyses about VV have been undertaken.89 The most recent systematic review addressing this issue globally included 38 studies. Authors concluded that the cost-effectiveness depends mainly on the effect of the incidence of HZ in the elderly, being cost-effective and cost-saving from payer and societal perspective not assuming any potential impact on HZ incidence. Conversely, considering a short-term increase on the incidence of HZ, VV would not be cost-effective. However, as discussed above, the real impact of universal VV in HZ disease is not clear in the older age groups and there is a need for further investigations, although there is an agreement among models that VV would reduce HZ incidence after 50 years of introduction.83,90 Moreover, if the impact on HZ is so important, HZ vaccines must be included in the model.91 Further, most cost-effectiveness analyses have intrinsic limitations of assuming uncertain or variable values as true and are done considering the data from high income countries.89,91

Conclusion

As discussed above and shown in Tables 2 and 3, extensive data have been published about the impact of universal VV on overall incidence, hospitalizations, complications and deaths. The results are consistent with a reduction greater than 80% in the incidence of disease and hospitalizations in most of the studies with a longer follow up. The additional effect of the second dose, as well as the indirect protection in non-vaccinated groups, has also been uniformly described. Concerns about an increase in the incidence of HZ in older individuals have not been confirmed in most of the studies, although a trend towards increasing HZ incidence has been shown by some of them. In this regard, probably longer observations may be necessary. Furthermore, though accurate data about burden may be difficult to obtain, universal VV seems to be cost-effective by reducing the rate of complications. As a limitation, most data are available from high and middle-income countries, and impact in low-income countries may not be the same as reported. Moreover, some countries have yet to overcome the heavy burden and mortality from other diseases such as measles, rotavirus, pneumococcal and meningococcal disease.64 Finally, VV is an important step in public health strategies and the introduction of universal vaccination should be considered if feasible from an economic standpoint.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have no declaration, financial benefit or public or private interest to disclosure.

Abbreviations

CI confidence interval

ED emergency department

HZ Herpes Zoster

U.S.A. The United States of America

VE Vaccine effectiveness

VV Varicella Vaccine

WHO World Health Organization.

References

- 1.Varicella vaccines. WHO position paper. Releve Epidemiol Hebd. 1998. August 7;73(32):241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: WHO position paper, June 2014–recommendations. Vaccine. 2016. January 4;34(2):198–199. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seward JF, Zhang JX, Maupin TJ, Mascola L, Jumaan AO.. Contagiousness of Varicella in vaccinated cases: a household contact study. JAMA. 2004. August 11;292(6):704. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, Asano Y, Yazaki T, Isomura S. Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of Varicella in children in hospital. The Lancet. 1974. November;304(7892):1288–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozaki T. Varicella vaccination in Japan: necessity of implementing a routine vaccination program. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(2):188–195. doi: 10.1007/s10156-013-0577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin M, Marti M, Kambhampati A, Jeram SM, Seward JF. Global Varicella Vaccine Effectiveness: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016. March 1;137(3):e20153741–e20153741. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirose M, Gilio AE, Ferronato AE, Ragazzi SLB. The impact of varicella vaccination on varicella-related hospitalization rates: global data review. Rev Paul Pediatr Engl Ed. 2016. September;34(3):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.rpped.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Streng A, Grote V, Rack-Hoch A, Liese JG. Decline of neurologic Varicella complications in children during the first seven years after introduction of Universal varicella vaccination in Germany, 2005–2011. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017. January;36(1):79–86. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spackova M, Muehlen M, Siedler A. Complications of Varicella after implementation of routine childhood varicella vaccination in Germany. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010. September;29(9):884–886. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e2817f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung J, Broder KR, Marin M. Severe varicella in persons vaccinated with varicella vaccine (breakthrough varicella): a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017. April 3;16(4):391–400. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2017.1294069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuter BJ, Weibel RE, Guess HA, Matthews H, Morton DH, Neff BJ, Provost PJ, Watson BA, Starr SE, Plotkin SA. Oka/Merck varicella vaccine in healthy children: final report of a 2-year efficacy study and 7-year follow-up studies. Vaccine. 1991. September;9(9):643–647. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(91)90189-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuter B, Matthews H, Shinefield H, Black S, Dennehy P, Watson B, Reisinger K, Kim LL, Lupinacci L, Hartzel J, et al. Ten year follow-up of healthy children who received one or two injections of varicella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004. February;23(2):132–137. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000109287.97518.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wutzler P, Bonanni P, Burgess M, Gershon A, Sáfadi MA, Casabona G. Varicella vaccination - the global experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017. August 3;16(8):833–843. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2017.1343669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang L-Y, Huang L-M, Chang I-S, Tsai F-Y. Epidemiological characteristics of varicella from 2000 to 2008 and the impact of nationwide immunization in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011. December;11(1) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-11-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. [Internet] World Health Organization 2018; 2018. [Accessed 2018 July 30]. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/schedules.

- 16.Varicella: Recommended vaccinations [Internet] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) 2018; 2018. [Accessed 2018 July 30]. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByDisease?SelectedDiseaseId=11&SelectedCountryIdByDisease=−1.

- 17.Marin M, Güris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep. 2007. June 22;56(RR–4):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah SS, Wood SM, Luan X, Ratner AJ. Decline in Varicella-related ambulatory visits and hospitalizations in the United States since routine immunization against Varicella. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010. March;29(3):199–204. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181bbf2a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez AS, Zhang J, Brown C, Bialek S. Varicella-related hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2006: the 1-dose varicella vaccination era. Pediatrics. 2011. February 1;127(2):238–245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung J, Harpaz R. Impact of the maturing varicella vaccination program on Varicella and related outcomes in the United States: 1994–2012. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2016. December;5(4):395–402. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez AS, Zhang J, Marin M. Epidemiology of Varicella during the 2-dose varicella vaccination program — United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016. September 2;65(34):902–905. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6534a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bialek SR, Perella D, Zhang J, Mascola L, Viner K, Jackson C, Lopez AS, Watson B, Civen R. Impact of a routine two-dose varicella vaccination program on Varicella epidemiology. Pediatrics. 2013. November 1;132(5):e1134–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung J, Lopez AS, Blostein J, Thayer N, Zipprich J, Clayton A, Buttery V, Andersen J, Thomas CA, Del Rosario M, et al. Impact of the US two-dose varicella vaccination program on the epidemiology of varicella outbreaks: data from Nine States, 2005–2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015. October;34(10):1105–1109. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quian J, Ruttimann R, Romero C, Dall’Orso P, Cerisola A, Breuer T, Greenberg M, Verstraeten T. Impact of universal varicella vaccination on 1-year-olds in Uruguay: 1997-2005. Arch Dis Child. 2008. October 1;93(10):845–850. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.126243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avila-Aguero ML, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Camacho-Badilla K, Soriano-Fallas A, Arroba-Tijerino R, Morice-Trejos A. Varicella prevention in Costa Rica: impact of a one-dose schedule universal vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016. March 4;16(3):229–234. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2017.1247700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrade AL, Da da Silva Vieira MA, Minamisava R, Toscano CM, de Lima Souza MB, Fiaccadori F, Figueiredo CA, Curti SP, Nerger MLBR, Bierrenbach AL. Single-dose varicella vaccine effectiveness in Brazil: A case-control study. Vaccine. 2018. January;36(4):479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wormsbecker AE, Wang J, Rosella LC, Kwong JC, Seo CY, Crowcroft NS, Deeks SL, Borrow R. Twenty years of medically-attended pediatric varicella and herpes zoster in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. Borrow R, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015. July 15;10(7):e0129483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter R, Tran TN, Ray P, Lewis E, Fireman B, Black S, Shinefield HR, Coplan PM, Saddier P. Impact of vaccination on the epidemiology of varicella: 1995-2009. Pediatrics. 2014. July 1;134(1):24–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly HA, Grant KA, Gidding H, Carville KS. Decreased varicella and increased herpes zoster incidence at a sentinel medical deputising service in a setting of increasing varicella vaccine coverage in Victoria, Australia, 1998 to 2012. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2014. October 16;19(41). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chao DY, Chien YZ, Yeh YP, Hsu PS, Lian IB. The incidence of varicella and herpes zoster in Taiwan during a period of increasing varicella vaccine coverage, 2000–2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2012. June;140(06):1131–1140. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Tawfiq JA, AbuKhamsin A, Memish ZA. Epidemiology and impact of varicella vaccination: A longitudinal study 1994–2011. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013. September;11(5):310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pozza F, Piovesan C, Russo F, Bella A, Pezzotti P, Emberti Gialloreti L. Impact of universal vaccination on the epidemiology of varicella in Veneto, Italy. Vaccine. 2011. November;29(51):9480–9487. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bechini A, Boccalini S, Baldo V, Cocchio S, Castiglia P, Gallo T, Giuffrida S, Locuratolo F, Tafuri S, Martinelli D, et al. Impact of universal vaccination against varicella in Italy: experiences from eight Italian Regions. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2015. January;11(1):63–71. doi: 10.4161/hv.34311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amodio E, Tramuto F, Cracchiolo M, Sciuto V, De Donno A, Guido M, Rota MC, Gabutti G, Vitale F. The impact of ten years of infant universal varicella vaccination in Sicily, Italy (2003–2012). Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2015. January;11(1):236–239. doi: 10.4161/hv.36157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streng A, Grote V, Carr D, Hagemann C, Liese JG. Varicella routine vaccination and the effects on varicella epidemiology – results from the Bavarian Varicella Surveillance Project (BaVariPro), 2006-2011. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013. December;13(1) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-13-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rieck T, Feig M, An der Heiden M, Siedler A, Wichmann O. Assessing varicella vaccine effectiveness and its influencing factors using health insurance claims data, Germany, 2006 to 2015. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2017. April 27;22(17) [Accessed 2017 Oct 29]. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=22784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cenoz MG, Catalán JC, Zamarbide FI, Berastegui MA, Gurrea AB. [Impact of universal vaccination against chicken pox in Navarre, 2006-2010]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2011. August;34(2):193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García Cenoz M, Castilla J, Chamorro J, Martínez-Baz I, Martínez-Artola V, Irisarri F, Arriazu M, Ezpeleta C, Barricarte A.Impact of universal two-dose vaccination on varicella epidemiology in Navarre, Spain, 2006 to 2012. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2013. August 8;18(32):20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cenoz MG, Martínez-Artola V, Guevara M, Ezpeleta C, Barricarte A, Castilla J. Effectiveness of one and two doses of varicella vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed cases in children in Navarre, Spain. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013. May 14;9(5):1172–1176. doi: 10.4161/hv.23451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latasa P, Gil de Miguel A, Barranco Ordoñez MD, Rodero Garduño I, Sanz Moreno JC, Ordobás Gavín M, Esteban Vasallo M, Garrido-Estepa M, García-Comas L. Effectiveness and impact of a single-dose vaccine against chickenpox in the community of Madrid between 2001 and 2015. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018. May 17:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1475813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García Comas L, Latasa Zamalloa P, Alemán Vega G, Ordobás Gavín M, Arce Arnáez A, Rodero Garduño I, Estirado Gómez A, Marisquerena EI. Descenso de la incidencia de la varicela en la Comunidad de Madrid tras la vacunación infantil universal. Años 2001-2015. Aten Primaria. 2018. January;50(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry O, Brzostek J, Czajka H, Leviniene G, Reshetko O, Gasparini R, Pazdiora P, Plesca D, Desole MG, Kevalas R et al. One or two doses of live varicella virus-containing vaccines: efficacy, persistence of immune responses, and safety six years after administration in healthy children during their second year of life. Vaccine. 2018. January;36(3):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scotta MC, Paternina-de la Ossa R, Lumertz MS, Jones MH, Mattiello R, Pinto LA. Early impact of universal varicella vaccination on childhood varicella and herpes zoster hospitalizations in Brazil. Vaccine. 2018. January;36(2):280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carville KS, Riddell MA, Kelly HA. A decline in varicella but an uncertain impact on zoster following varicella vaccination in Victoria, Australia. Vaccine. 2010. March;28(13):2532–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heywood AE, Wang H, Macartney KK, McIntyre P. Varicella and herpes zoster hospitalizations before and after implementation of one-dose varicella vaccination in Australia: an ecological study. Bull World Health Organ. 2014. August 1;92(8):593–604. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elbaz M, Paret G, Yohai AB, Halutz O, Grisaru-Soen G. Immunisation led to a major reduction in paediatric patients hospitalised because of the varicella infection in Israel. Acta Paediatr. 2016. April;105(4):e161–6. doi: 10.1111/apa.13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waye A, Jacobs P, Tan B. The impact of the universal infant varicella immunization strategy on Canadian varicella-related hospitalization rates. Vaccine. 2013. October;31(42):4744–4748. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan B, Bettinger J, McConnell A, Scheifele D, Halperin S, Vaudry W, Law B. The effect of funded varicella immunization programs on varicella-related hospitalizations in IMPACT centers, Canada, 2000–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012. September;31(9):956–963. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318260cc4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell ML, Dover DC, Simmonds KA, Svenson LW. Shingles in Alberta: before and after publicly funded varicella vaccination. Vaccine. 2014. October;32(47):6319–6324. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ávila-Agüero ML, Beltrán S, Castillo JB, Castillo Díaz ME, Chaparro LE, Deseda C, Debbag R, Espinal C, Falleiros-Arlant LH, González Mata AJ, et al. Varicella epidemiology in Latin America and the Caribbean. Expert Rev Vaccines [Internet]. 2017. December 19 [Accessed 2018 Mar 1]. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14760584.2018.1418327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Martino Mota A, Carvalho-Costa FA. Varicella zoster virus related deaths and hospitalizations before the introduction of universal vaccination with the tetraviral vaccine. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016. July;92(4):361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riera-Montes M, Bollaerts K, Heininger U, Hens N, Gabutti G, Gil A, Nozad B, Mirinaviciute G, Flem E, Souverain A et al. Estimation of the burden of varicella in Europe before the introduction of universal childhood immunization. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017. December;17(1) [Accessed 2018 Mar 1]. http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-017-2445-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Varicella vaccination in the European Union. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Varicella-Guidance-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Helmuth IG, Poulsen A, Suppli CH, Mølbak K. Varicella in Europe—A review of the epidemiology and experience with vaccination. Vaccine. 2015. May;33(21):2406–2413. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siedler A, Arndt U. Surveillance and outbreak reports. Impact of the routine varicella vaccination programme on varicella epidemiology in Germany [Internet]; 2010. April 1 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19530T. [PubMed]

- 56.Liese JG, Cohen C, Rack A, Pirzer K, Eber S, Blum M, Greenberg M, Streng A. The effectiveness of varicella vaccination in children in Germany: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013. September;32(9):998–1004. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829ae263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siedler A, Rieck T, Tolksdorf K. Strong additional effect of a second Varicella vaccine dose in children in Germany, 2009-2014. J Pediatr. 2016. June;173:202–206.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siedler A, Dettmann M. Hospitalization with varicella and shingles before and after introduction of childhood varicella vaccination in Germany. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014. December 2;10(12):3594–3600. doi: 10.4161/hv.34426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bella A, Trucchi C, Gabutti G, Cristina Rota M. Burden of varicella in Italy, 2001–2010: analysis of data from multiple sources and assessment of universal vaccination impact in three pilot regions. J Med Microbiol. 2015. November 1;64(11):1387–1394. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boccalini S, Bonanni P, Bechini A. Preparing to introduce the varicella vaccine into the Italian immunisation programme: varicella-related hospitalisations in Tuscany, 2004–2012. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2016. June 16;21(24) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gil-Prieto R, Walter S, Gonzalez-Escalada A, Garcia-Garcia L, Marín-García P, Gil-de-Miguel A. Different vaccination strategies in Spain and its impact on severe varicella and zoster. Vaccine. 2014. January;32(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gil-Prieto R, Garcia-Garcia L, San-Martin M, Gil-de-Miguel A. Varicella vaccination coverage inverse correlation with varicella hospitalizations in Spain. Vaccine. 2014. December;32(52):7043–7046. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Critselis E, Theodoridou K, Alexopoulou Z, Theodoridou M, Papaevangelou V. Time trends in pediatric Herpes zoster hospitalization rate after Varicella immunization: herpes zoster hospitalization time trends. Pediatr Int. 2016. June;58(6):534–536. doi: 10.1111/ped.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dbaibo G, Tatochenko V, Wutzler P. Issues in pediatric vaccine-preventable diseases in low- to middle-income countries. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016. September;12(9):2365–2377. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1181243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hussey H, Abdullahi L, Collins J, Muloiwa R, Hussey G, Kagina B. Varicella zoster virus-associated morbidity and mortality in Africa – a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017. December;17(1) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-017-2815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sheridan SL, Quinn HE, Hull BP, Ware RS, Grimwood K, Lambert SB. Impact and effectiveness of childhood varicella vaccine program in Queensland, Australia. Vaccine. 2017. June;35(27):3490–3497. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khandaker G, Marshall H, Peadon E, Zurynski Y, Burgner D, Buttery J, Gold M, Nissen M, Elliott EJ, Burgess M, et al. Congenital and neonatal varicella: impact of the national varicella vaccination programme in Australia. Arch Dis Child. 2011. May 1;96(5):453–456. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.206037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen L-K, Arai H, Chen LY, Chou MY, Djauzi S, Dong B, Kojima T, Kwon KT, Leong HN, Leung EM et al. Looking back to move forward: a twenty-year audit of herpes zoster in Asia-Pacific. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017. December;17(1) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. http://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-017-2198-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoshikawa T, Kawamura Y, Ohashi M. Universal varicella vaccine immunization in Japan. Vaccine. 2016. April;34(16):1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hattori F, Miura H, Sugata K, Yoshikawa A, Ihira M, Yahata Y, Kamiya H, Tanaka-Taya K, Yoshikawa T. Evaluating the effectiveness of the universal immunization program against varicella in Japanese children. Vaccine. 2017. September;35(37):4936–4941. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee YH, Choe YJ, Cho S, Kang CR, Bang JH, Oh M, Lee J-K. Effectiveness of varicella vaccination program in preventing laboratory-confirmed cases in children in Seoul, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(12):1897. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh SH, Choi EH, Shin SH, Kim Y-K, Chang JK, Choi KM, Hur JK, Kim K-H, Kim JY, Chung EH, et al. Varicella and varicella vaccination in South Korea. Plotkin SA, editor. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014. May;21(5):762–768. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00645-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi UY, Huh DH, Kim JH, Kang JH. Seropositivity of Varicella zoster virus in vaccinated Korean children and MAV vaccine group. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016. October 2;12(10):2560–2564. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1190056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang W-C, Huang L-M, Chang I-S, Tsai F-Y, Chang L-Y. Varicella breakthrough infection and vaccine effectiveness in Taiwan. Vaccine. 2011. March;29(15):2756–2760. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Turab M, Chehadeh W. Varicella infection in the Middle East: prevalence, complications, and vaccination. J Res Med Sci. 2018;23(1):19. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_979_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Hoek AJ, Melegaro A, Zagheni E, Edmunds WJ, Gay N. Modelling the impact of a combined varicella and zoster vaccination programme on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus in England. Vaccine. 2011. March 16;29(13):2411–2420. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taylor JA. Herd immunity and the varicella vaccine: is it a good thing? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001. April;155(4):440–441. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chaves SS, Lopez AS, Watson TL, Civen R, Watson B, Mascola L, Seward JF. Varicella in infants after implementation of the US varicella vaccination program. Pediatrics. 2011. December 1;128(6):1071–1077. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kappagoda C, Shaw P, Burgess M, Botham S, Cramer L. Varicella vaccine in non-immune household contacts of children with cancer or leukaemia: varicella vaccine in contacts of children with cancer. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999. August;35(4):341–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tseng HF, Smith N, Marcy SM, Sy LS, Jacobsen SJ. Incidence of herpes zoster among children vaccinated with Varicella Vaccine in a prepaid health care plan in the United States, 2002–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009. December;28(12):1069–1072. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181acf84f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, Roberts M, Vandermeer M, Riedlinger K, Bialek SR, Marin M. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the Varicella Vaccine Era, 2005–2009. J Infect Dis. 2013. December 1;208(11):1859–1868. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Civen R, Marin M, Zhang J, Abraham A, Harpaz R, Mascola L, Bialek SR. Update on incidence of herpes zoster among children and adolescents after implementation of varicella vaccination, Antelope Valley, CA, 2000 to 2010. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016. October;35(10):1132–1136. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Gay NJ, Law B, De Serres G. Modelling the impact of immunization on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus. Epidemiol Infect. 2000. December;125(3):651–669. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800004714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patel MS, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Herpes zoster–related hospitalizations and expenditures before and after introduction of the Varicella Vaccine in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008. December;29(12):1157–1163. doi: 10.1086/590662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawai K, Yawn BP, Wollan P, Harpaz R. Increasing incidence of herpes zoster over a 60-year period from a population-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016. July 15;63(2):221–226. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leung J, Harpaz R, Molinari N-A, Jumaan A, Zhou F. Herpes zoster incidence among insured persons in the United States, 1993–2006: evaluation of impact of varicella vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2011. February 1;52(3):332–340. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nelson MR, Britt HC, Harrison CM. Evidence of increasing frequency of herpes zoster management in Australian general practice since the introduction of a varicella vaccine. Med J Aust. 2010. July 19;193(2):110–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Horn J, Karch A, Damm O, Kretzschmar ME, Siedler A, Ultsch B, Weidemann F, Wichmann O, Hengel H, Greiner W, et al. Current and future effects of varicella and herpes zoster vaccination in Germany – insights from a mathematical model in a country with universal varicella vaccination. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016. February 2:1–11. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1135279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Unim B, Saulle R, Boccalini S, Taddei C, Ceccherini V, Boccia A, Bonanni P, La Torre G. Economic evaluation of varicella vaccination: results of a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013. September 19;9(9):1932–1942. doi: 10.4161/hv.25228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gao Z, Gidding HF, Wood JG, MacINTYRE CR. Modelling the impact of one-dose vs. two-dose vaccination regimens on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus in Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2010. April;138(04):457. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Damm O, Ultsch B, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Greiner W, Wichmann O.. Systematic review of models assessing the economic value of routine varicella and herpes zoster vaccination in high-income countries. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2015. December;15(1) [Accessed 2018 Aug 8]. http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-015-1861-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]