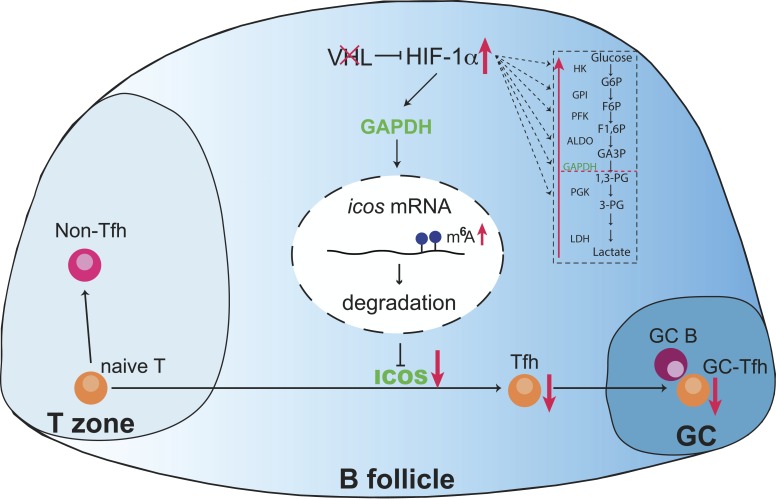

Zhu et al. demonstrate that the VHL–HIF-1α axis plays an important role during the initiation of Tfh cells through glycolytic-epigenetic reprogramming. The downstream player, GAPDH, impairs Tfh cell development by decreasing icos expression through regulation of m6A modification.

Abstract

Follicular helper T (Tfh) cells are essential for germinal center formation and effective humoral immunity, which undergo different stages of development to become fully polarized. However, the detailed mechanisms of their regulation remain unsolved. Here we found that the E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL was required for Tfh cell development and function upon acute virus infection or antigen immunization. VHL acted through the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α)−dependent glycolysis pathway to positively regulate early Tfh cell initiation. The enhanced glycolytic activity due to VHL deficiency was involved in the epigenetic regulation of ICOS expression, a critical molecule for Tfh development. By using an RNA interference screen, we identified the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH as the key target for the reduced ICOS expression via m6A modification. Our results thus demonstrated that the VHL–HIF-1α axis played an important role during the initiation of Tfh cell development through glycolytic-epigenetic reprogramming.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Follicular helper T (Tfh) cells are a unique CD4+ T cell subset to initiate germinal center (GC) formation and promote B cell responses, which are essential for the production of high-affinity antibodies to eliminate invading pathogens (Crotty, 2011; Vinuesa et al., 2016). Tfh cells are localized in B cell follicles and provide multiple signals to B cells to form GCs where GC B cells undergo somatic hypermutation, affinity maturation, antibody class switching, and differentiation into high-affinity plasma cells and long-lived memory cells (Crotty, 2011; Vinuesa et al., 2016). A combination of signals and transcription factors is required for the initiation, commitment, and maintenance of Tfh cells (Crotty, 2011). Chemokine receptor CXCR5, as the first marker identified on Tfh cells, is important for Tfh cell migration toward B cell follicles and GCs (Breitfeld et al., 2000; Schaerli et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001). B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl-6) is the master transcriptional factor, which can repress key molecules of other T cell subsets to promote Tfh cell development (Johnston et al., 2009; Nurieva et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2009). Inducible costimulator (ICOS) is indispensable for both initiation and commitment stages of Tfh cell development to instruct cognate T cell–B cell interaction (Akiba et al., 2005; Nurieva et al., 2008), or via bystander B cell entanglement with CD4+ T cells (Xu et al., 2013). However, the detailed mechanisms by which Tfh cell development is regulated remain largely unclear.

Recent studies have documented that dynamic regulation of metabolism is crucial for T cell proliferation and differentiation, including that of Tfh cells (Ganeshan and Chawla, 2014). It is reported that Bcl-6 represses the gene expression of glycolytic enzymes, which antagonizes the effect of T-bet, a T helper type 1 (Th1) cell transcription factor, thus balancing the outcomes of Th1/Tfh cell differentiation (Oestreich et al., 2014). Consistent with the Bcl-6/T-bet balance model, IL-2–induced activation of the Akt and mTORC1 causes the shift of glucose metabolism from less glycolytic Tfh cells to higher glycolytic Th1 cells after acute viral infection (Ray et al., 2015). However, ICOS-driven mTORC1 and mTORC2 activation also leads to increased anabolic metabolism and enhanced Tfh cell development, and overexpression of glucose transporter Glut1 in Glut1 transgenic mice causes augmented Tfh cell responses (Zeng et al., 2016), suggesting that glucose metabolism favors Tfh cell development. Thus, it remains enigmatic how exactly the glucose metabolism affects the development and function of Tfh cells.

The Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) gene is identified as a tumor suppressor gene whose inherited mutation in human can lead to different cancers, and an essential component of the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase complex with elongin B/C, cullin 2, and Ring box protein 1 (Rbx1; Gossage et al., 2015). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α subunit (HIF-1α) is the well-characterized substrate of VHL and undergoes proteasome-mediated degradation under normoxic conditions. On the other hand, hypoxic conditions result in the accumulation and subsequent translocation of HIF-1α into the nucleus, and dimerization with HIF-1β for transcription of target genes, which in turn lead to functional and metabolic adaptations to hypoxic microenvironments (Schofield and Ratcliffe, 2004; Semenza, 2007). The role of the VHL–HIF axis has been implicated in the regulation of different immune cells. For example, the VHL–HIF axis plays an important role in CD8+ T cell effector function and memory formation to persistent antigen stimulation (Doedens et al., 2013; Phan et al., 2016). HIF-1α is involved in the balance of Th17/regulatory T cell differentiation(Dang et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011). Our recent work also demonstrated that VHL–HIF1α axis is a key regulator for maintaining stability and suppressive function of regulatory T cells (Lee et al., 2015). More recently, we demonstrated that the development of innate lymphoid type 2 cells is regulated by the VHL–HIF pathway via the control of glycolysis at the PKM2-pyruvate checkpoint (Li et al., 2018). It is known that lymphoid tissues are exposed to different oxygen gradients under physiological and inflamed conditions (Sitkovsky and Lukashev, 2005). Particularly, the GCs have been shown to be an extremely anoxic site that is involved in the regulation of GC formation and antibody production (Abbott et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2016). However, it is still unknown whether the VHL–HIF axis controls the development and function of Tfh cells in the lymphoid microenvironments.

We speculated that the VHL–HIF axis and different metabolic states are required in Tfh cells for their proper differentiation and function. To this end, we generated VHL conditional knockout mice driven by CD4Cre, and we found that the VHL–HIF-1α axis plays a key role in the initiation stage of Tfh cell development and regulates GC responses through glycolytic-epigenetic reprogramming.

Results

Vhl is indispensable for the development and function of Tfh cells

To investigate whether the E3 ligase VHL affects the development of Tfh cells, we generated Vhlfl/flCD4Cre mice (VHL cKO mice) in which loxP-flanked Vhl alleles are deleted by Cre recombinase driven by the T cell–specific CD4 promoter. We confirmed the loss of Vhl mRNA and protein in CD4+ T cells from VHL cKO mice by quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting (Fig. S1, A and B). VHL cKO cells showed much higher expression level of HIF-1α compared with WT cells (Fig. S1 C). We then examined whether T cell–specific deletion of VHL affects T cell development in the thymus and spleen. VHL cKO mice exhibited normal frequencies and cell numbers within each developmental compartment of the thymus (Fig. S1, D and E). Although splenic CD8+ T cells showed decreased frequency and cell number in VHL cKO mice, the frequencies and cell numbers of total, naive, and effector CD4+ T cells were comparable between WT C57BL/6J (B6) and VHL cKO mice (Fig. S1, F and G).

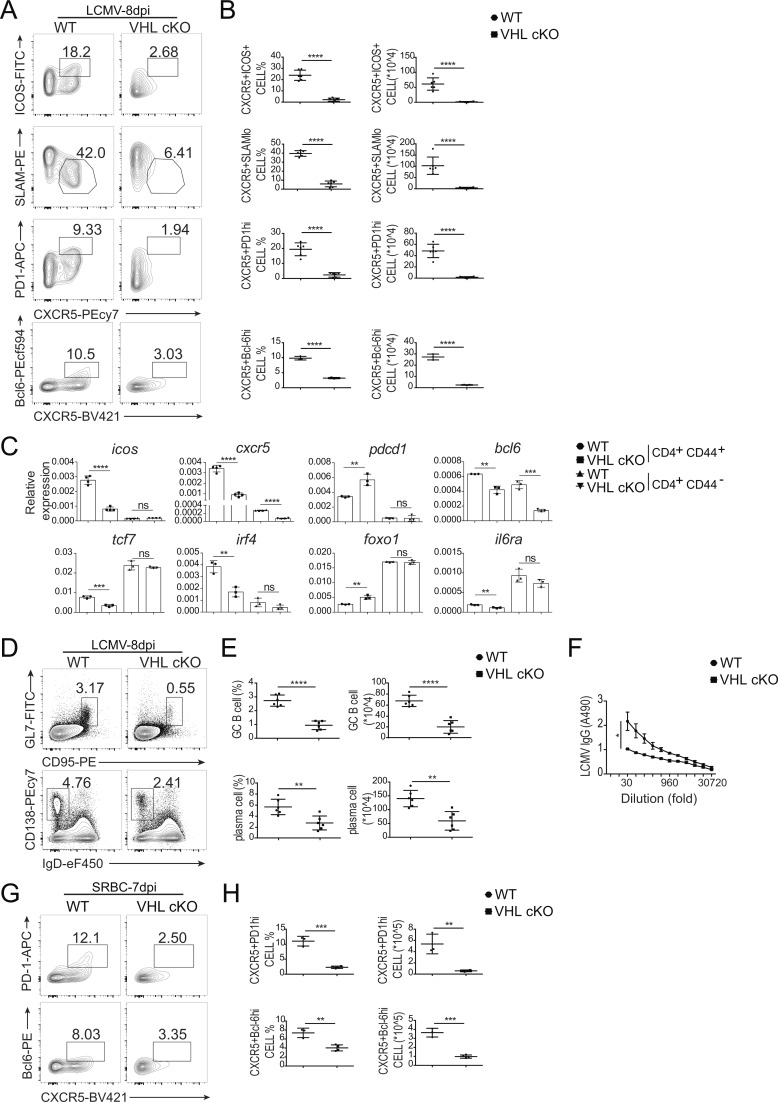

To examine the role of VHL in the development and function of Tfh cells, we analyzed the induction of splenic Tfh and GC–Tfh cells in a mouse model of acute infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). At day 8 after infection, we found that both percentage and absolute number of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) and GC-Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) in VHL cKO mice were significantly decreased compared with those in WT mice (Fig. 1, A and B). Defective Tfh cell development was also observed in the mesenteric LN (mLN) and Peyer’s patch (PP) of VHL cKO mice (Fig. S1, H–K). In addition, the percentages of Annexin V+ dead cells, Ki67+ proliferating cells, and IL-2–producing cells were comparable between WT and VHL cKO mice (Fig. S1, L and M). IFN-γ–producing cells showed slightly decreased frequency in VHL cKO mice (Fig. S1 N). Then we sorted splenic CD4+CD44+ T cells and CD4+CD44− T cells from LCMV-infected WT and VHL cKO mice and examined expression of several genes related to Tfh cell development. Consistent with the above data, we found that the expression levels of icos, cxcr5, bcl6, tcf7, irf4, and il6ra were down-regulated in CD4+CD44+ T cells from VHL cKO mice, while VHL deficiency led to increased gene expression of pdcd1 and foxo1 (Fig. 1 C). Reduced gene expression of cxcr5 and bcl6 was also observed in CD4+CD44− T cells of VHL cKO cells.

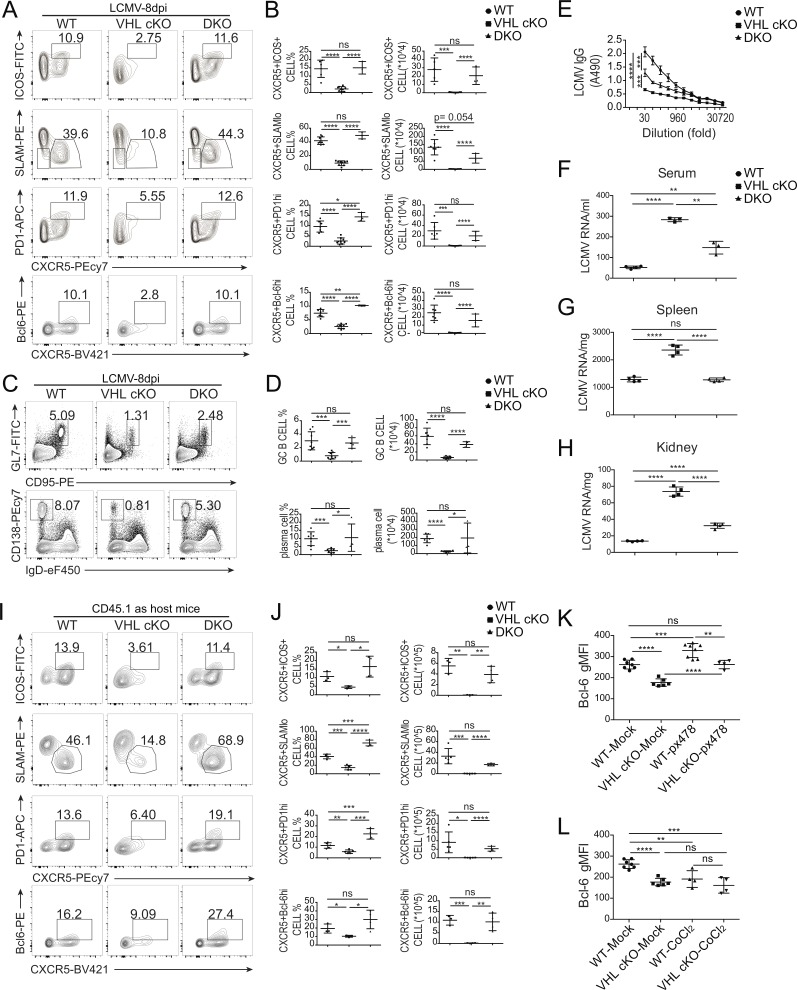

Figure 1.

VHL deficiency results in defective Tfh cell development and function. (A) Representative flow-cytometric plots of activated CD44+CD4+ T cells from WT and CD4CreVhlfl/fl (VHL cKO) mice 8 d after infection with LCMV. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (B) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) and number of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells of mice as in A (n = 6 per group). (C) RT-PCR analysis of mRNA of Tfh cell–related genes in CD44+CD4+ and CD44−CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO mice 8 d after LCMV infection; results were normalized to those of Actb mRNA (encoding β-actin). (D) Representative flow-cytometric plots of total B220+ B cells from WT and VHL cKO mice 8 d after LCMV infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC B (GL7+CD95+; top row) or plasma (CD138+IgDlo; bottom row) cells in the spleen. (E) Quantification of frequency (among B220+ B cells) and number of GC B and plasma cells in the spleen of mice as in D (n = 6 per group). (F) ELISA of LCMV-specific IgG in the sera from infected mice as in D (n = 6 per group), presented as absorbance at 490 nm (A490). (G) Representative flow-cytometric plots of CD44+CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO mice 7 d after immunization with SRBC. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (H) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) and number of GC-Tfh cells of mice as in G (n = 3–4 per group). Each symbol (B, E, and H) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Moreover, we analyzed splenic B cell response by assessing the abundance of GC B cells and plasma cells, and LCMV-specific antibody production in the sera of WT and VHL cKO mice. Both GC B cells (GL7+CD95+) and plasma B cells (CD138+IgDlo) showed reduced cell percentages and absolute numbers in VHL cKO mice (Fig. 1, D and E). Consistent with the impaired Tfh and B cell response in VHL cKO mice, LCMV-specific IgG concentration in the sera from VHL cKO mice was much lower than that from WT mice (Fig. 1 F). These data suggested that VHL could positively regulate Tfh cell development and function upon virus infection without affecting CD4+ T cell death or proliferation at the periphery.

To further confirm these findings, we immunized the mice by intraperitoneal injection of sheep red blood cells (SRBCs). Consistently, at day 7 after immunization, loss of VHL resulted in significant reduction of the development of Tfh cells (Fig. 1, G and H). These data demonstrated that VHL positively regulated Tfh cell development upon different antigen stimulation.

Intrinsic effect of VHL on Tfh cell development and function

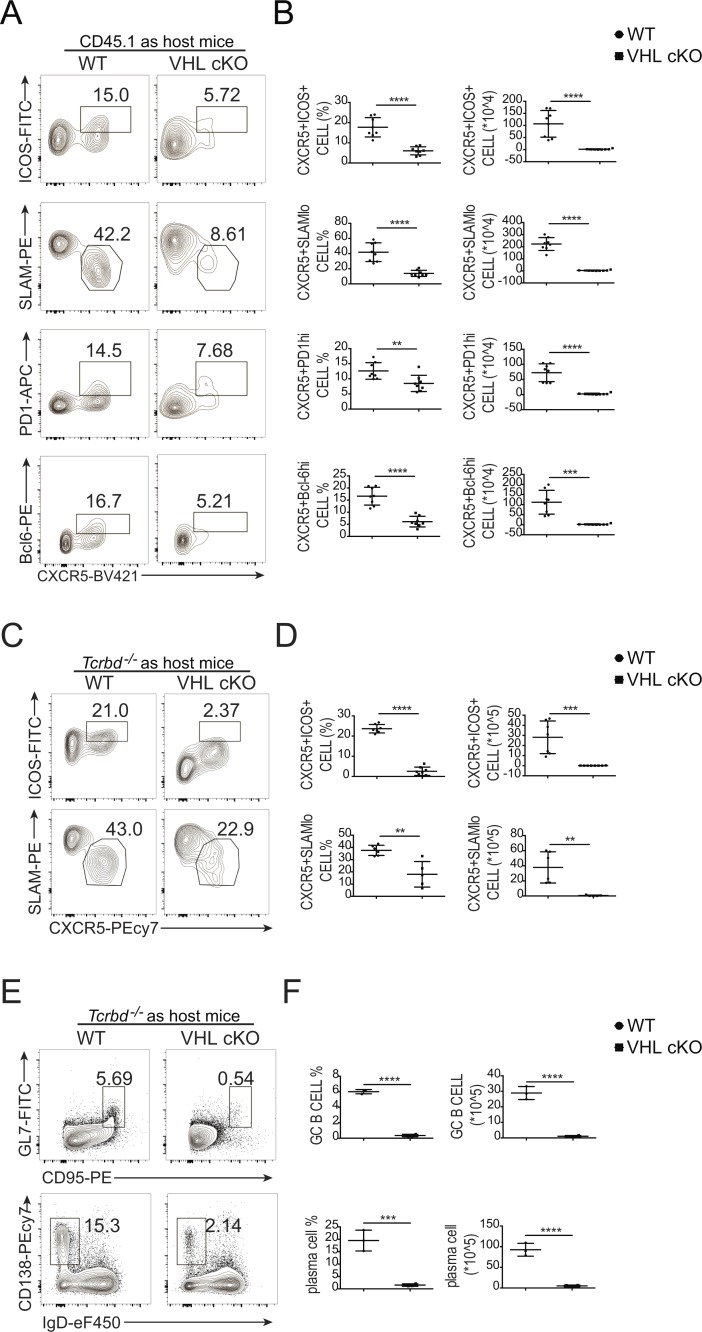

Next, we investigated whether VHL regulates Tfh cell development in a T cell–intrinsic manner. First, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeric mice by transplanting bone marrow cells from WT or VHL cKO mice (CD45.2+) mixed in a ratio of 4:1 with bone marrow cells from WT mice (CD45.1+) into lethally irradiated T cell–deficient Tcrbd−/− host mice. We infected the chimeras with LCMV at 6–8 wk after transplantation, and observed impaired Tfh cell and GC-Tfh cell development of VHL cKO cells in the chimeric mice, while those of WT control cells (CD45.1) in WT or VHL cKO chimeric mice were comparable (Fig. S2, A–D).

We then crossed VHL cKO mice with SMARTA transgenic mice, which have transgenic expression of a T cell antigen receptor specific for the epitope of LCMV glycoprotein amino acids 66–77 (Oxenius et al., 1998) to generate VHL cKO SMARTA mice. We purified naive CD4+ T cells from WT SMARTA and VHL cKO SMARTA mice (CD45.2+), and then adoptively transferred them into WT CD45.1 host mice, followed by LCMV infection. At day 8 after LCMV infection, we observed impaired Tfh cell (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) and GC–Tfh cell (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) development of donor cells (CD45.2+) in the host mice receiving transfer of VHL cKO SMARTA CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2, A and B). To further confirm these findings, we adoptively transferred naive CD4+ T cells from WT SMARTA and VHL cKO SMARTA mice into Tcrbd−/− host mice. Strikingly, CXCR5+ICOS+ Tfh cells were significantly reduced in VHL cKO cells, as well as the CXCR5+SLAMlo Tfh cells (Fig. 2, C and D). Moreover, we investigated the role of VHL on Tfh cell function, indicated by splenic B cell responses in Tcrbd−/− host mice. Consistently, we found that the percentages and absolute numbers of both GC B cells and plasma B cells in the Tcrbd−/− host mice receiving VHL cKO-SMARTA CD4+ T cells were decreased significantly (Fig. 2, E and F). Altogether, these findings suggested that VHL positively regulated Tfh cell development and function in a CD4+ T cell–intrinsic manner.

Figure 2.

Intrinsic role of VHL in the development and function of Tfh cells. (A) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from WT CD45.1+ host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO SMARTA mice, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (B) Quantification of frequency (among CD45.2+CD4+ T cells) and number (CD45.2+CD4+) of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells of WT CD45.1+ host mice as in A (n = 8 per group). (C) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from Tcrbd−/− host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO SMARTA donor mice, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells. (D) Quantification of frequency (among CD45.2+CD4+ T cells) and number (CD45.2+CD4+) of Tfh cells of Tcrbd−/− host mice as in C (n = 7–8 per group). (E) Representative flow-cytometric plots of total B220+ B cells obtained from Tcrbd−/− host mice as described in C. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC B (GL7+CD95+) cells (top row) or plasma CD138+IgDlo cells (bottom row) in the spleen. (F) Quantification of frequency (among B220+ B cells) and number of GC B and plasma cells in the spleen of mice as in C (n = 3–4 per group). Each symbol (B, D, and F) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

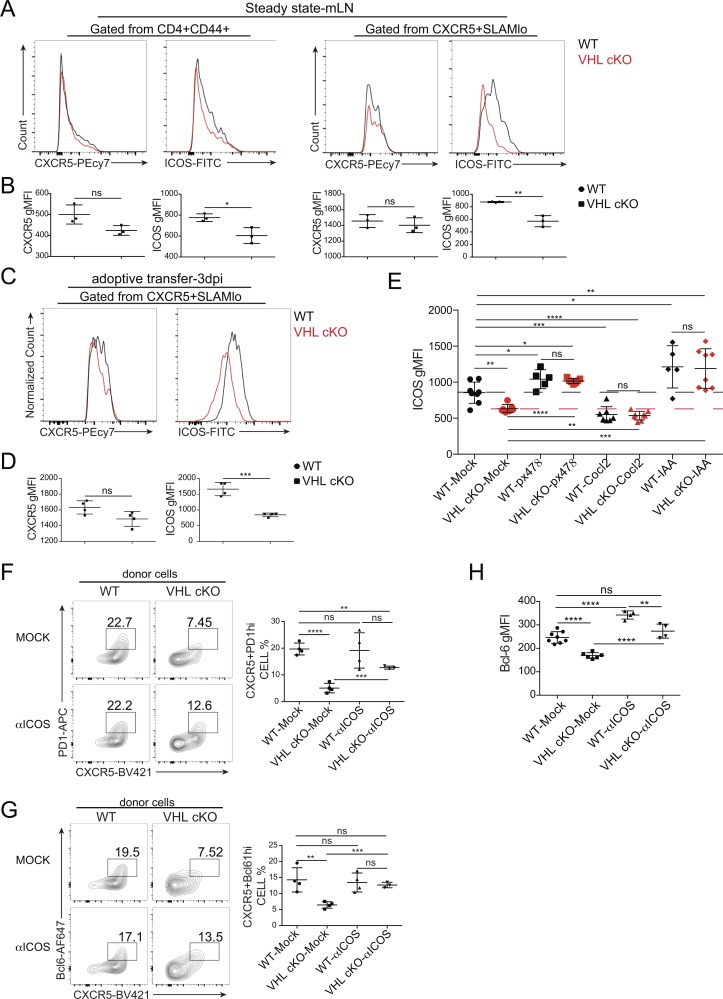

VHL is required for the early initiation of Tfh cells

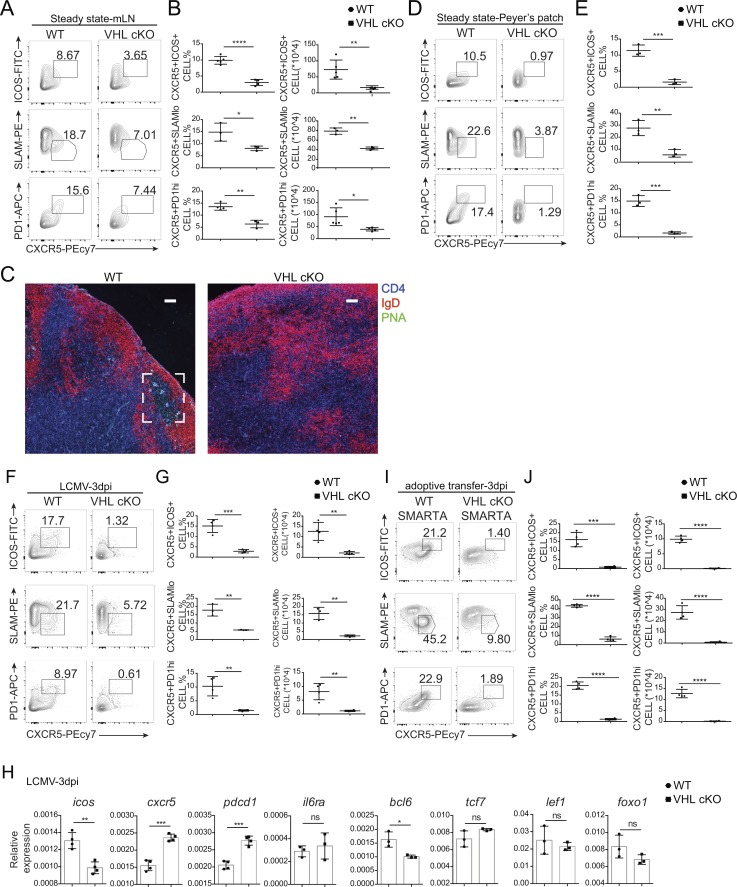

Tfh cell development is a multi-stage process (Crotty, 2011). To figure out at which stage VHL has an impact on Tfh cells, we first analyzed the development of Tfh cells in the mLN and PP of WT and VHL cKO mice under steady state. We found that both percentage and absolute number of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) and GC-Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD-1hi) in VHL cKO mice were significantly decreased compared with those in WT mice (Fig. 3, A, B, D, and E), while the percentages of Annexin V+ dead cells, Ki67+ proliferating cells, and CD44+ activated cells were comparable in the mLN of WT and VHL cKO mice (Fig. S2 E). Immunofluorescence analysis of mLNs from VHL cKO mice showed defective GC formation, indicated by peanut agglutinin (PNA) staining (Fig. 3 C). These data suggested that VHL plays an important role in the early initiation of Tfh cells under steady state.

Figure 3.

VHL is indispensable for the initiation of Tfh cell development. (A) Representative flow-cytometric plots of CD44+CD4+ T cells in the mLN from WT and VHL cKO mice under steady state. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (B) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) and number of Tfh or GC-Tfh cells of mice as in A (n = 3–5 per group). (C) Immunofluorescence of GCs in the mLNs as in A. Sections of mLNs were stained with IgD (red), CD4 (blue), and PNA (green). Bars, 50 µm. (D) Representative flow-cytometric plots of CD44+CD4+ T cells in the PP from WT and VHL cKO mice under steady state. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (E) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) of Tfh or GC-Tfh cells of mice as in D (n = 3 per group). (F) Representative flow-cytometric plots of CD44+CD4+ T cells in the spleen from WT and VHL cKO mice 3 d after infection with LCMV. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (G) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) and number of Tfh or GC-Tfh cells of mice as in F (n = 3–4 per group). (H) RT-PCR analysis of mRNA of Tfh cell–related genes in CD44+CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO mice 3 d after LCMV infection; results were normalized to those of Actb mRNA (encoding β-actin). (I) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from WT CD45.1+ host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO SMARTA mice, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 3 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (J) Quantification of frequency (among CD45.2+CD4+ T cells) and number (CD45.2+CD4+) of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells of WT CD45.1+ host mice as in I (n = 4 per group). Each symbol (B, E, G, and J) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Next, we investigated whether VHL affects the early development of Tfh cells in the context of LCMV infection. Defective Tfh cell development was observed in VHL cKO mice at day 3 after LCMV infection, the beginning of the initiation of Tfh cell development (Fig. 3, F and G). However, loss of VHL did not affect cell viability, proliferation, or activation at this stage (3 d after infection) as the percentages of Annexin V+ dead cells, Ki67+ proliferating cells, or CD44+ activated cells did not show much difference (Fig. S2 F). In addition, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression level of icos and bcl6 was reduced in the CD44+CD4+ T cells from VHL cKO mice 3 d after LCMV infection, while the expression of pdcd1 was increased. Loss of VHL also led to increased cxcr5 expression, which may result from the feedback of defective Tfh cells. The expression of tcf7, lef1, and foxo1 did not show much difference as they are more important during the late stage of Tfh cell development (Fig. 3 H). Consistently, Tfh cell development was impaired in VHL cKO mice at day 6 after LCMV infection, while cell viability and proliferation were not affected (Fig. S2, G–I). The expression levels of icos, cxcr5, il6ra, bcl6, and tcf7 were reduced in VHL cKO cells, and that of foxo1 was increased (Fig. S2 J). Adoptive transfer experiments of CD4+ T cells from WT or VHL cKO–SMARTA showed that Tfh cell development was attenuated in VHL cKO cells at day 3 after LCMV infection (Fig. 3, I and J), which indicated the CD4+ T cell intrinsic role of VHL in the early initiation of Tfh cells. Altogether, these data demonstrated that VHL is indispensable at the initiation stage of Tfh cell development.

HIF-1α mediates VHL regulation of Tfh cells

VHL ubiquitinates and degrades HIF-1α, which serves as a well-established and conserved target (Schofield and Ratcliffe, 2004; Semenza, 2007). In addition, HIF-1α is highly expressed in GCs, and plays an important role in GC B cell responses (Cho et al., 2016). To investigate whether the effect of VHL on Tfh development is dependent of HIF-1α, we generated VHL cKO–HIF-1αfl/fl mice (DKO) and analyzed Tfh cell development after LCMV infection. We confirmed the loss of HIF-1α protein in CD4+ T cells from DKO mice by flow-cytometric analysis (Fig. S3 A). At day 8 after LCMV infection, the development of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) and GC–Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) in DKO mice was restored to the level of WT mice in both frequency and cell number (Fig. 4, A and B). In addition, impaired GC responses in VHL cKO mice indicated by reduced percentage and absolute number of GC B cells and plasma cells in spleen as well as decreased LCMV-specific IgG concentration in the sera were partially, but significantly rescued in DKO mice (Fig. 4, C–E). Furthermore, we found that the LCMV RNA copies in the serum, spleen, and kidney from VHL cKO mice were much higher, which was reduced to the levels of WT mice in DKO mice (Fig. 4, F–H).

Figure 4.

HIF-1α mediates VHL regulation of Tfh cell development. (A) Representative flow-cytometric analysis of CD44+CD4+ T cells from WT, VHL cKO, and Vhlfl/fl Hif1afl/flCD4Cre (DKO) mice 8 d after LCMV infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (B) Quantification of frequency (among CD44+CD4+ T cells) and number of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells of mice as in A (n = 7, WT group; n = 8, VHL cKO group; n = 3, DKO group). (C) Representative flow-cytometric plots of total B220+ B cells from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice as in A. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC B (GL7+CD95+; top row) or plasma (CD138+IgDlo) cells (bottom row) in the spleen. (D) Quantification of frequency (among B220+ B cells) and number of GC B and plasma cells in the spleen of mice as in A (n = 7, WT group; n = 8, VHL cKO group; n = 4, DKO group). (E) ELISA of LCMV-specific IgG in the sera from infected mice as in A (n = 4 per group), presented as absorbance at 490 nm (A490). (F–H) RT-PCR analysis of quantification of LCMV copies in serum (F), spleen (G), and kidney (H) from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice 8 d after LCMV infection (n = 3 or 4 per group). (I) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from WT CD45.1+ host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO SMARTA mice, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (J) Quantification of frequency (among CD45.2+CD4+ T cells) and number (CD45.2+CD4+) of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells of WT CD45.1 host mice as in I (n = 3–5 per group). (K and L) Quantification of Bcl-6 geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) in WT or VHL cKO Tfh-like cells cultured in the absence or presence of px478 (K) or CoCl2 (L). Each symbol (B, D, F–H, and J) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We also crossed DKO mice with SMARTA mice to generate DKO SMARTA mice and adoptively transferred naive CD4+ T cells from WT SMARTA, VHL cKO SMARTA, and DKO SMARTA mice into WT CD45.1 or Tcrbd−/− host mice. Impaired Tfh and GC–Tfh cell development of VHL cKO cells was fully rescued by the combination of VHL and HIF-1α double deficiency, in that WT CD45.1 host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from DKO SMARTA mice showed similar Tfh cell frequency and number as those receiving from WT SMARTA mice (Fig. 4, I and J). Within Tcrbd−/− host mice, the development of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) of DKO SMARTA CD4+ T cells was comparable with that of WT SMARTA CD4+ T cells (Fig. S3, B and C). Attenuated GC responses in the Tcrbd−/− host mice receiving VHL cKO SMARTA cells were also restored in mice transferred with DKO SMARTA cells (Fig. S3, D and E).

Next, to further confirm the in vivo findings, we set up an in vitro Tfh-like cell culture system. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 supplemented with anti–IFN-γ, anti–IL-4, anti-TGFβ, IL-6, and IL-12. Cultured Tfh-like cells were harvested at day 6 for flow-cytometric analysis. Indeed, up-regulated expression level of Bcl-6 was observed in the Tfh-like cells compared with Th0 cells (Fig. S3 F). Purified naive CD4+ T cells from WT or VHL cKO mice were then cultured to induce Tfh-like cells in the absence or presence of px478, the inhibitor of HIF-1α. Consistently, a decreased expression level of Bcl-6 was observed in VHL cKO cells compared with that of WT cells, which was rescued with px478 treatment (Fig. 4 K). Moreover, Bcl-6 expression was reduced to the level of VHL cKO cells via CoCl2-mediated HIF-1α stabilization (Fig. 4 L). Altogether, these data demonstrated that HIF-1α mediates the effect of VHL in regulating the development and function of Tfh cells.

GAPDH is crucial for Tfh development

Since HIF-1α plays important roles in cell metabolism and preferentially induces the gene expression of glycolytic enzymes (Semenza, 2007), we next investigated whether the glycolytic pathway driven by the VHL–HIF-1α axis regulates Tfh cell development. We first examined the expression of genes related to the glycolytic pathway by qRT-PCR and found that the gene expression of glycolytic enzymes such as gapdh and aldoa was significantly increased in sorted splenic CD4+CD44+ T cells from LCMV-infected VHL cKO mice, whereas that was comparable between the cells from WT and DKO mice (Fig. S4 A). Then we performed a Seahorse extracellular flux assay. Compared with WT cells, VHL cKO cells displayed higher extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) assessed by both basic glycolysis and glycolytic capacity upon blockade of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by oligomycin (Fig. S4, B and C). Consistently, VHL cKO cells showed reduced oxygen consumption rate (OCR) determined by basal OCR and maximal OCR upon trifuoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP) treatment to uncouple the mitochondrial proton gradient (Fig. S4, D and E). Also, the enhanced glycolytic flux and decreased mitochondrial respiration in VHL cKO cells were reverted to the level of WT cells when combined with HIF-1α deficiency (Fig. S4, B–E). Furthermore, we analyzed mitochondrial mass and membrane potential in CD4+CD44+ T cells from WT or VHL cKO mice after LCMV infection. As expected, VHL cKO cells showed decreased mitochondrial mass and membrane potential (Fig. S4, F and G). These findings suggested that VHL cKO cells displayed enhanced glycolysis and attenuated mitochondrial activity, which was dependent on HIF-1α.

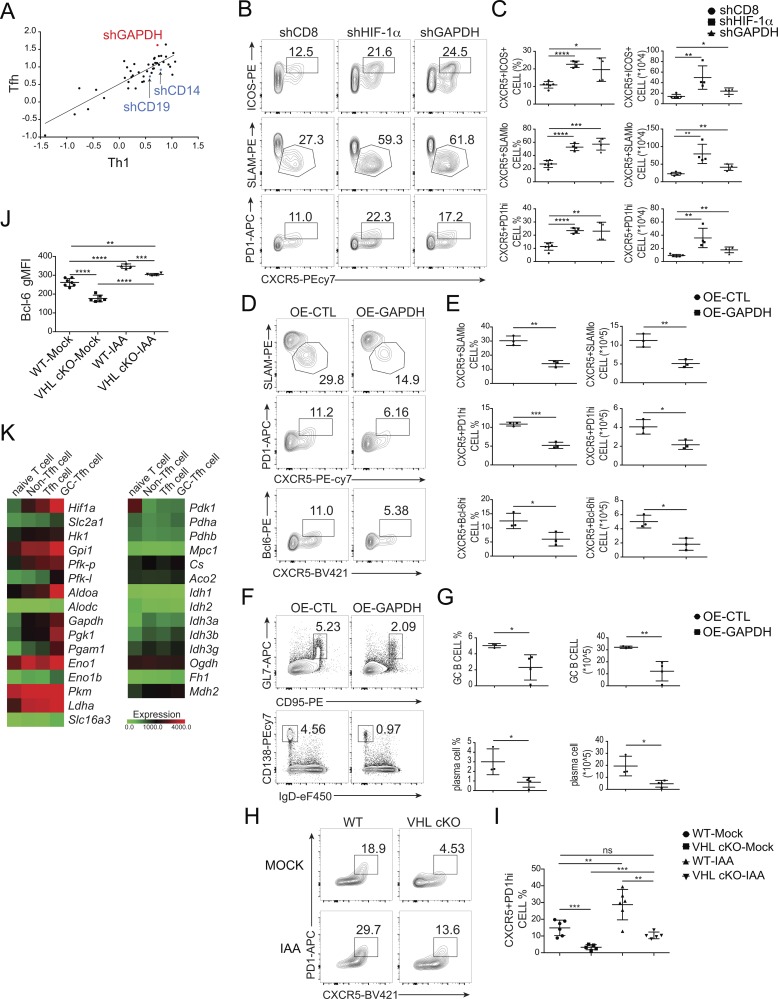

To further investigate whether and how the up-regulated glycolysis could account for the dysregulation of development of Tfh cells and GC–Tfh cells in VHL cKO cells, we performed a pooled RNA interference–based screen in T cells as previously described (Chen et al., 2014). To this end, we constructed a library of 47 short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in a microRNA context (shRNAmirs) targeting 39 genes in glycolytic pathway and TCA cycle for in vivo screening of Tfh cell development. Among tested enzymes, GAPDH knockdown was the most significant candidate promoting Tfh cell development (Fig. 5 A). To further confirm this observation, SMARTA CD4+ T cells (CD45.1) transduced with shGAPDH (Ametrine+) were adoptively transferred into B6 host mice (CD45.2), followed by LCMV infection. At day 8 after infection, the development of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) was enhanced in Ametrine+ cells transduced with vector expressing GAPDH shRNA as well as shHIF-1α–expressing cells compared with shCD8-bearing cells as control (Fig. 5, B and C). In contrast, overexpression of GAPDH in SMARTA CD4+ T cells resulted in defective Tfh cell development compared with mock transduction, while we did not observe any effect of Aldolase A (ALDOA) overexpression on Tfh cells in the host mice (Fig. 5, D and E; and Fig. S4, H and I). In addition, defective splenic B cell responses assessed by the abundance of GC B cells and plasma cells were observed in host mice receiving SMARTA CD4+ T cells with GAPDH overexpression (Fig. 5, F and G).

Figure 5.

GAPDH acts as a downstream mediator of VHL–HIF-1α axis in Tfh cells. (A) Scatter plot showing the log2 ratio of normalized reads of all shRNAs in sorted Tfh (TFH, CXCR5+SLAMlo) and Th1 (TH1, CXCR5−SLAMhi) cell subset versus the input sample. Each dot represented a unique shRNA. (B) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor SMARTA CD45.1+Ametrine+CD4+ T cells obtained from B6 host mice receiving SMARTA CD45.1+CD4+ T cells transduced with shCD8, shHIF-1α, and shGAPDH (Ametrine+), followed by infection of host mice with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (C) Quantification of frequency (among CD4+CD45.1+Ametrine+ T cells) and number (CD4+CD45.1+Ametrine+) of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells in host mice as in B (n = 4–6 per group). (D) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor SMARTA CD45.1+GFP+CD4+ T cells obtained from Tcrbd−/− host mice receiving SMARTA CD45.1+CD4+ T cells transduced with retroviral vector expressing GFP only (OE-CTL), or GAPDH (OE-GAPDH) followed by infection of host mice with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (E) Quantification of frequency (among CD4+CD45.1+GFP+ T cells) and number (CD4+CD45.1+GFP+) of Tfh and GC-Tfh cells in host mice as in D (n = 3 per group). (F) Representative flow-cytometric plots of B220+ B cells from Tcrbd−/− host mice as in D. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC B (GL7+CD95+) cells (top row) or plasma CD138+IgDlo cells (bottom row) in the spleen. (G) Quantification of frequency (among B220+ B cells) and number of GC B cells and plasma cells in the spleen of mice as in D (n = 3–4 per group). (H) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from WT CD45.1+ host mice receiving WT or VHL cKO OT-II CD4+ T cells cultured in the absence or presence of IAA, followed by immunization with OVA protein and analysis 7 d after immunization. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells. (I) Quantification of frequency (among CD45.2+CD4+ T cells) of GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi) cells in WT CD45.1 host mice as in H (n = 5–6 per group). (J) Quantification of Bcl-6 MFI in WT or VHL cKO Tfh-like cells cultured in the absence or presence of 2.5 µM IAA. (K) Heat map of differentially expressed genes encoding hif1a, glycolytic enzymes, and oxidative enzymes in purified naive CD4+ T cells, and sorted non-Tfh, Tfh, and GC-Tfh cells from LCMV-infected mice, presented as log2 reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads values. Each symbol (C, E, G, and I) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We further investigated whether inhibition of GAPDH in VHL cKO CD4+ T cells can reverse the impaired Tfh cell development. We crossed VHL cKO mice with OT-II transgenic mice to generate VHL cKO OT-II mice. Naive CD4+ T cells from WT OT-II and VHL cKO OT-II mice were purified and cultured in the absence or presence of a GAPDH inhibitor, sodium iodoacetate (IAA). These cells were adoptively transferred into CD45.1 host mice followed by immunization with OVA protein. At day 7 after immunization, we found that consistent with the effect of shGAPDH on Tfh cell development (Fig. 5, B and C), IAA-treated WT OT-II cells showed enhanced Tfh cell development (CXCR5+PD-1hi) compared with that of the control group (Fig. 5, H and I). Moreover, the impaired Tfh cell development in VHL cKO cells was restored after IAA treatment (Fig. 5, H and I). Consistently, in vitro Tfh-like cell culture experiments showed that decreased Bcl-6 expression in VHL cKO cells was rescued by IAA treatment (Fig. 5 J). These findings suggested that the increased glycolytic activity induced by HIF-1α, especially the induction of GAPDH, negatively regulated the initiation of Tfh cell development.

Next, we investigated whether oxidative metabolism is required during this process. We performed RNA sequencing in naive CD4+ T cells, non-Tfh cells (CXCR5−SLAMhi), Tfh cells (CXCR5+SLAMlo), and GC-Tfh cells. The genes involved in oxidative metabolism showed relatively lower expression in comparison with that of glycolytic genes (Fig. 5 K). Also, like hif1a, most of the glycolytic genes showed up-regulated expression levels in Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells compared with non-Tfh cells or naive CD4+ T cells. However, this unique pattern of gradually increased gene expression levels from naive T, non-Tfh, to Tfh and GC-Tfh cells was not observed in genes related to oxidative metabolism (Fig. 5 K).

Furthermore, silence of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 (MPC1), the transporter for cytoplasmic pyruvate across the inner membrane of mitochondria, either by shMPC1-mediated knockdown or treatment with UK5099, a MPC1 inhibitor, did not show much difference on Tfh cell development (Fig. S4, J–M). And ex vivo treatment with citrate, a metabolite in the TCA cycle, also failed to affect Tfh cell development (Fig. S4, N and O). Altogether, these results suggested that oxidative metabolism may not be necessary during Tfh cell development. Instead, the VHL–HIF-1α axis regulates Tfh cell development by controlling the cellular glycolytic pathway.

VHL–HIF-1α axis instructs the early initiation of Tfh cells via ICOS

The initiation of Tfh cell development is controlled by multiple signaling, especially ICOS signaling and CXCR5 expression (Crotty, 2011). To clarify the downstream player of the VHL–HIF-1α–GAPDH pathway during this process, we first analyzed the surface expression level of ICOS and CXCR5 in the CD4+CD44+–activated T cell and CXCR5+SLAMlo Tfh cell populations from mLNs of WT and VHL cKO mice under steady state. We found that the expression level of ICOS but not CXCR5 was decreased in both cell populations (Fig. 6, A and B). For further confirmation, naive CD4+ T cells from WT SMARTA and VHL cKO SMARTA mice were purified and adoptively transferred into CD45.1 host mice followed by LCMV infection. At day 3 after LCMV infection, we analyzed the expression level of CXCR5 and ICOS in the CXCR5+SLAMlo Tfh cell population. ICOS showed significantly decreased expression, while CXCR5 did not show much difference (Fig. 6, C and D). In addition, qRT-PCR analysis of CD44+CD4+ T cells from LCMV infected WT and VHL cKO mice at 3 d after infection showed that the expression level of icos was significantly reduced (Fig. 3 H). Furthermore, in vitro Tfh-like cell culture experiments showed that the expression level of ICOS was decreased in VHL cKO cells compared with WT cells within untreated groups, which could be restored through px478-mediated HIF-1α repression or IAA-mediated GAPDH inhibition (Fig. 6 E). Consistently, we observed that enhancement of HIF-1α by CoCl2 treatment resulted in decreased ICOS expression (Fig. 6 E).

Figure 6.

ICOS is the main target of VHL–HIF-1α–GAPDH pathway during Tfh cell differentiation. (A) Representative flow-cytometric analysis of CXCR5 or ICOS expression in the indicated cell populations in the mLN of WT and VHL cKO mice under steady state. (B) Quantification of CXCR5 or ICOS MFI in the cell population as indicated in A. (C) Representative flow-cytometric analysis of CXCR5 or ICOS expression in the indicated cell population of donor CD45.2+CD4+ T cells obtained from WT CD45.1+ host mice receiving naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO SMARTA mice, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 3 d after infection (dpi). (D) Quantification of CXCR5 or ICOS MFI in the cell population as indicated in C. (E) Quantification of ICOS MFI in WT or VHL cKO Tfh-like cells cultured in the absence or presence of px478, CoCl2, or 2.5 µM IAA. (F and G) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor CD45.1+CD4+ T cells (left) and quantification of frequency (among CD45.1+CD4+ T cells) of GC-Tfh cells (right) obtained from B6 host mice receiving WT or VHL cKO OT-II CD4+ T cells cultured in the absence or presence of anti-ICOS (C398.4A), followed by immunization with OVA protein and analysis 7 d after immunization. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of CXCR5+PD-1hi GC-Tfh cells (F) and CXCR5+Bcl6hi GC-Tfh cells (G; n = 3 or 4 per group). (H) Quantification of Bcl-6 MFI in WT or VHL cKO Tfh-like cells cultured in the absence or presence of anti-ICOS. Each symbol (B, D, F, and G) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Next, we investigated whether augmented ICOS signaling through anti-ICOS stimulation in VHL cKO cells can restore the defective Tfh cell development. Purified naive CD4+ T cells from WT or VHL cKO OT-II mice were cultured in the absence or presence of soluble anti-ICOS supplemented with IL-2 for 48 h. Then the cells were adoptively transferred into B6 host mice followed by OVA protein immunization. At day 7 after immunization, we found that defective GC-Tfh cell development observed in VHL cKO cells was partially rescued through ex vivo anti-ICOS treatment as the decreased frequency of GC-Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl6hi) upon VHL deletion was restored after anti-ICOS treatment (Fig. 6, F and G). The development of Tfh cells of host mice was comparable (Fig. S5 A). However, forced ICOS signaling by ex vivo treatment could decrease quickly after cell transferring, as treated WT cells did not show much difference (Fig. 6, F and G). In vitro studies showed that decreased Bcl-6 expression in VHL cKO cells was restored upon anti-ICOS stimulation (Fig. 6 H). Surface ICOS expression of both WT and VHL cKO cells decreased upon anti-ICOS stimulation, which could result from the strong ICOS signaling–mediated ICOS receptor internalization (Fig. S5 B). Altogether, these data demonstrated that ICOS is the major target of the VHL–HIF-1α–GAPDH axis to instruct the early development of Tfh cells.

GAPDH suppresses icos expression via N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification in Tfh cells

It was reported that GAPDH regulates mRNA stability by binding to the 3′ UTR of mRNAs (Chang et al., 2013; Garcin, 2019), and icos mRNA stability can be affected by binding of Roquin to its 3′ UTR (Yu et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that GAPDH binds to 3′ UTR of icos mRNA to regulate its stability. We performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) to examine whether GAPDH could bind to 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of icos mRNA. Purified CD4+ T cells transduced with control or GAPDH overexpression plasmid (Myc-tagged) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and immunoprecipitates were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Although GAPDH could bind to ifng mRNA as previously reported (Chang et al., 2013), we did not observe the binding of GAPDH to icos mRNA (Fig. S5 C).

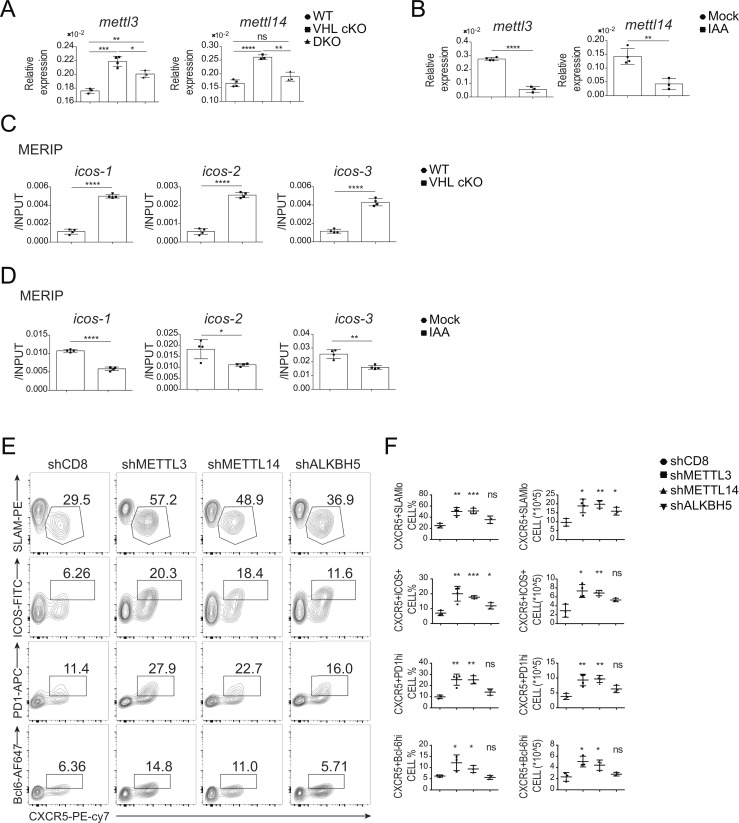

m6A is the most prevalent modification of mRNA in mammalian cells, and is implicated in degradation of mRNA (Fu et al., 2014). Next, we tested whether promoted glycolysis in VHL-deficient CD4+ T cells could affect icos mRNA expression via m6A modification in Tfh cells. We found that the expression levels of methyltransferase genes mettl3 and mettl14 were increased in CD4+CD44+ VHL cKO T cells, while those in DKO cells were the same as those of WT cells (Fig. 7 A). By contrast, the gene expression of mettl3 and mettl14 in IAA-treated cells was markedly reduced (Fig. 7 B).

Figure 7.

GAPDH regulates m6A modification on icos mRNA. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA of mettl3 and mettl14 in CD44+CD4+ T cells from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice 8 d after infection with LCMV (n = 3 or 4 per group). Each gene expression was normalized to that of Actb mRNA (encoding β-actin). (B) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA of mettl3, mettl14, and alkbh5 in WT CD4+ T cells cultured in the absence (Mock) or presence of 5 µM IAA (n = 4 per group). Each gene expression was normalized to that of Actb mRNA (encoding β-actin). (C) MERIP–qRT-PCR analysis of icos mRNA immunoprecipitated with anti-m6A antibody in CD4+ T cells cultured in vitro with IL-2 and IL-7 for 48 h from WT and VHL cKO mice. Results were normalized to input RNA. (D) MERIP–qRT-PCR analysis of icos mRNA immunoprecipitated with anti-m6A antibody in WT CD4+ T cells cultured in the absence (Mock) or presence of 2.5 µM IAA. Results were normalized to input RNA. (E) Representative flow-cytometric plots of donor SMARTA CD45.1+Ametrine+CD4+ T cells obtained from B6 host mice receiving WT SMARTA CD4+ T cells transduced with shCD8 (control), shMETTL3, shMETTL14, and shALKBH5, followed by infection with LCMV and analysis 8 d after infection. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate frequency of Tfh (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) cells or GC-Tfh (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl-6hi) cells. (F) Quantification of frequency (among CD4+CD45.1+Ametrine+ T cells) and number (CD4+CD45.1+Ametrine+) of Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells in host mice as in E (n = 3–4 per group). Each symbol (F) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± SD). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (Student’s t test). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Moreover, we performed methylated RIP (MERIP) to measure the level of m6A modification on icos mRNA. Splenic CD4+ T cells from WT or VHL cKO mice were cultured in vitro with IL-2 and IL-7 for 48 h, and the total RNA was purified followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-m6A antibody. We found that m6A modification on icos mRNA in VHL cKO cells was increased, which could be rescued in DKO cells (Fig. 7 C and Fig. S5 D). The m6A modification on bcl6 and tcf7 mRNAs was also enhanced in VHL cKO cells, which was reverted to the level of that in WT cells when combined with HIF-1α deficiency (Fig. S5 D). However, a significant difference of m6A modification on cxcr5 and pdcd1 mRNA was not observed in VHL cKO cells compared with WT cells. In addition, VHL cKO cells showed reduced m6A modification on foxo1, prdm1, and tbx21 mRNAs, whereas these changes were not restored in DKO cells (Fig. S5 D). We then investigated the effect of GAPDH inhibition by IAA treatment on the level of m6A modification on the above mRNAs. Consistently, decreased m6A modification on icos as well as tcf7 mRNA was observed in IAA-treated cells (Fig. 7 D and Fig. S5 E). Slight reduction was also found in that of bcl6 mRNA after IAA treatment (Fig. S5 E). The m6A modification on foxo1 mRNA was increased in IAA-treated cells. However, m6A modification on cxcr5, ascl2, and pdcd1 mRNAs did not show significant difference after IAA-mediated GAPDH inhibition (Fig. S5 E). Together, these data demonstrated that reduced icos expression in VHL-deficient cells could result from enhanced m6A modification on icos mRNA catalyzed by METTL3/METTL14.

We further investigated whether methyltransferases METTL3 and METTL14 or demethylase ALKBH5 play a role in Tfh cell development. shCD8, shMETTL3, shMETTL14, or shALKBH5-bearing CD4+ T cells from SMARTA mice (CD45.1) were adoptively transferred into B6 host mice followed by LCMV infection. At day 8 after infection, the development of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ICOS+ or CXCR5+SLAMlo) and GC-Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD-1hi or CXCR5+Bcl6hi) was enhanced in the cells bearing shMETTL3 or shMETTL14, but not shALKBH5-expressing cells compared with the control cells bearing shCD8 (Fig. 7, E and F). These findings strongly suggested that induced GAPDH protein by VHL deficiency reduced icos expression through METTL3/METTL14-catalyzed m6A modification on icos mRNA, leading to attenuated Tfh cell differentiation.

Discussion

Although it is well established that the generation of Tfh cells from naive CD4+ T cells is a multi-stage process that is composed of initiation, commitment, and maintenance stages (Crotty, 2011), the molecular mechanism by which Tfh cell development is regulated at each stage is still far from clear. Here we demonstrated that the VHL–HIF-1α axis is an important signaling pathway for Tfh cell initiation through modulating cellular glycolytic metabolism, thereby instructing the expression of surface markers on Tfh cells for proper GC responses. By adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells specifically lacking Vhl, we found that VHL was intrinsically required for Tfh cell development and GC responses. Importantly, we identified one of the glycolytic enzymes, GAPDH, as a key player to regulate Tfh cell development, acting as an epigenetic regulator. Further mechanistic analysis revealed that GAPDH could alter METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A modification on icos mRNA during the initiation of Tfh cells.

Although GCs are thought to be hypoxic, the effects of hypoxia on B cell responses seem to be contradictory (Abbott et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2016). Low oxygen tension or persistent induction of HIF transcription factors in B cells limits cell proliferation, isotype switching, and levels of high-affinity antibodies (Cho et al., 2016), whereas hypoxic culture condition rather enhances class switching recombination and plasmacyte differentiation (Abbott et al., 2016). The differences may reflect the experimental conditions employed in the two studies. In our study, we revealed an important role of VHL–HIF-1α axis at the initiation stage of Tfh cell development: accumulation of HIF proteins resulting from the loss of Vhl in CD4+ T cells negatively regulates the early development of Tfh cells. Moreover, consistent with the observation of oxygen gradients in these previous studies of B cells, we found that the gene expression level of Hif1a was increased from primary Tfh cells toward GC-Tfh cells, indicating the exposure to different oxygen levels in B cell follicles and GCs where Tfh cells and GC-Tfh cells differentiate, respectively. Importantly, we demonstrated that the early initiation stage of Tfh cell development is regulated by VHL–HIF-1α to regulate the subsequent B cell responses.

HIF-1α–mediated glycolysis has emerged as a key regulator for the activation and development of immune cells (Ganeshan and Chawla, 2014); however, it remains unclear how glucose metabolism regulates Tfh cell development. Our RNA sequencing analysis showed that the expression level of glycolysis-related genes in Tfh cells was much higher than that of oxidative metabolism-related genes, which suggested that glycolysis but not oxidative metabolism is indispensable during Tfh cell development. Indeed, we found that silence of MPC1 or citrate treatment did not affect the development of Tfh cells, while the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH negatively regulated Tfh cell development at the initiation phase, which supports a previous report demonstrating less glycolysis in Tfh cells (Ray et al., 2015). Moreover, RNA sequencing analysis revealed that GC-Tfh cells exhibited higher expression levels of glycolytic genes than those of Tfh cells, which was consistent with the observation of up-regulated gene expression of Hif1a in GC-Tfh cells, suggesting that different metabolic states are required for Tfh cell initiation and GC-Tfh cell commitment for fueling and instruction. Indeed, it is shown that mTOR kinase complex drives glycolytic shift, which leads to enhanced Tfh cell development and GC responses (Zeng et al., 2016). Thus, further studies will be needed to clarify how such specific metabolic enzymes or metabolites are balanced and regulate multiple stages of Tfh cell development in a concerted manner.

ICOS is crucial for Tfh cell development at both initiation and commitment (Crotty, 2011), whereas the underlying mechanism by which icos gene expression is regulated is still unclear. It was reported that Roquin can repress icos expression by binding to the 3′ UTR of icos mRNA to promote its degradation (Yu et al., 2007). In addition, GAPDH is involved in the regulation of mRNA stability by binding to the 3′ UTR of mRNAs (Garcin, 2019). Instead, we found that GAPDH negatively controls icos gene expression through the m6A modification on icos mRNA, but not binding to icos mRNA. It was previously reported that hypoxia plays a role in the regulation of m6A modification on nanog mRNA, which further degrades nanog mRNA (Zhang et al., 2016). Thus, it is likely that HIF-1α–induced GAPDH controls icos expression by promoting icos mRNA degradation via m6A modification. Mechanistically, enhanced glycolysis induces the gene expression of the methyltransferase complex including mettl3 and mettl14, which subsequently catalyze m6A modification on icos mRNA, and lead to the suppression of icos expression. Although the precise mechanisms through which GAPDH regulates mettl3/mettl14 expression at transcriptional level are not clarified yet, our data indicated that GAPDH functions as not only a classical glycolytic enzyme, but also an epigenetic regulator of downstream targets of the VHL–HIF-1α axis at the initiation of Tfh cell differentiation, and m6A modification mediates icos gene expression, which was important for Tfh cell development.

In summary, our results indicate that the oxygen level in the local microenvironments in lymphoid tissues is involved in spatial and temporal modulation of developmental processes of Tfh cells through metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic regulation. Since Tfh cells play critical roles not only in humoral immune responses, but also in the development of autoimmune diseases (Zhu et al., 2016), our findings imply that clinical manipulation of Tfh cells could be accomplished by targeting the VHL–HIF-1α axis or glycolysis pathway for rational vaccine design against human infectious diseases and therapeutic intervention of autoimmune diseases.

Materials and methods

Mice

Vhlfl/fl, Hif1afl/fl, CD4Cre, SMARTA, OT-II, Tcrbd−/−, and CD45.1 mice on the C57BL/6J (B6) background were bred and housed under specific pathogen–free conditions at Tsinghua University. CD4Cre, SMARTA mice and Vhlfl/fl mice have been described previously (Xiao et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018). OT-II, Hif1afl/fl, and Tcrbd−/− mice were kindly provided by Y. Shi, W. Zeng, and C. Dong, respectively (Tsinghua University, Beijing, China). To generate Vhlfl/flCD4Cre (VHL cKO) and Vhlfl/fl Hif1afl/flCD4Cre mice (DKO mice), Vhlfl/fl Hif1afl/+ mice were crossed with Vhlfl/fl Hif1afl/+CD4Cre mice. Mice were used at 6–8 wk of age, and all experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tsinghua University.

Antibodies

For flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, ELISA, and cell stimulation, antibodies to mouse CD3ε (145-2C11) and CD28 (37.51) were from BioXCell; antibodies to mouse CD4 (RM4-5), CD4 (GK1.5), CD25 (PC61.5), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), B220 (RA3-6B2), ICOS (7E.17G9), PD-1 (J43), Ki-67 (SolA15), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), IL-2 (JES6-5H4), IgD (11-26c), Annexin V, streptavidin, and Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 450 were from eBioscience; antibodies to mouse CD4 (RM4-5), CXCR5 (2G8), Bcl-6 (K112-91), CD95 (Jo2), the T cell– and B cell–activation antigen (GL7), and streptavidin were from BD PharMingen; and antibodies to CD8 (53–6.7), CD150 (SLAM, TC15-12F12.2), CD138 (281–2), and streptavidin were from BioLegend. Biotin-conjugated goat antibody to rat IgG (112–065-167) was from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Antibody to HIF-1α (241812) was from R&D Systems. Biotinylated PNA (B-1075) was from Vector Laboratories. Goat anti-mouse IgG (1030–08) was from SouthernBiotech. For immunoprecipitation assay and immunoblot analysis, antibodies to Myc (sc-40 [9E10]) and VHL (sc-5575 [FL-181]) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; antibody to actin (A2228 [AC-74]) was from Sigma-Aldrich; antibody to m6A (61496) was from Active Motif; and polyclonal rabbit IgG (isotype control, ab171870) was from Abcam.

Reagents

Recombinant human IL-2 (200–02) and mouse IL-7 (217–17) were from Peprotech. IAA (I2515), CoCl2 (232696), sodium citrate (PHR1416), and UK5099 (PZ0160) were from Sigma-Aldrich. PX-478 2HCl (px478, S7612) was from Selleck.

Mouse infection and immunization

For LCMV Armstrong infection, virus was titrated in plain DMEM. Each mouse was infected with 2 × 105 plaque-forming units of LCMV for experiments at day 8 or day 6, and 5 × 105 plaque-forming units of LCMV for day 3, by intraperitoneal injection. For SRBC immunization, each mouse was immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 0.3 ml SRBC. For OVA protein immunization, OVA protein (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS was emulsified with CFA (Sigma-Aldrich) at the ratio of 1: 1 (volume). Each mouse was immunized with 150 µg of OVA protein by subcutaneous injection.

Bone marrow chimeras

After red blood cell depletion, bone marrow cells from WT or VHL cKO mice (CD45.2) were mixed with the cells from CD45.1 control mice in a ratio of 4:1. 4 × 106 cells were injected into lethally irradiated (500 rads, twice) Tcrbd−/− host mice, by intravenous injection. At 6–8 wk after transplantation, the mice were used for experiments.

Naive T cell purification and cell transfer

CD4+ T cells in splenocytes were preenriched by CD4+ (L3T4) microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Naive CD4+ T cells were then purified by BD FACSAria II based on CD4+CD25−CD62L+CD44− cell surface markers. For cell transfer, 1 × 105 naive CD4+ T cells were transferred into CD45.1 host mice for experiments at day 8, or 5 × 105 cells for experiments at day 3, by intravenous injection. Naive CD4+ T cells (2 × 105 cells) were transferred into Tcrbd−/− host mice for experiments at day 8, by intravenous injection. Retrovirus-transduced SMARTA CD4+ cells (5 × 105 cells) were transferred into B6 or Tcrbd−/− host mice for experiments at day 8, by intravenous injection. Metabolite/inhibitor-treated CD4+ OT-II cells (2 × 105) were transferred into B6 host mice for experiments at day 7 by intravenous injection.

Retroviral transduction

The oligonucleotides incorporating miR-30 microRNA sequence into target sequences (Table S1) were cloned into the plasmid pLMPd-Ametrine. cDNA encoding GAPDH or ALDOA was subcloned into pMIG-myc-GFP vector. Plat-E packaging cells were transfected with 2.5 µg of retroviral vector with 7.5 µl of TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus). The culture supernatant containing retrovirus was collected at 48 h after transfection. Naive SMARTA CD4+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (2C11; BioXCell) and anti-CD28 (37.51; BioXCell) for 24 h, then infected with retrovirus together with 8 µg/ml polybrene and 40 ng/ml IL-2 (Peprotech) by centrifugation at 1,900 rpm for 90 min at 37°C. At 24 h after infection, the cells were rested in fresh medium with 40 ng/ml IL-2 for 48 h followed by culturing in fresh medium in the presence of 2 ng/ml IL-7 for 12–16 h.

Treatment with metabolites/inhibitors

For adoptive transfer experiments, naive CD4+ T cells were purified and seeded in 24-well plates precoated with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28. After 24 h stimulation, the cell culture medium was changed to fresh medium with 15 ng/ml IL-2, 15 ng/ml IL-7, and indicated metabolites or inhibitors. After 24 h treatment, the cells were rested in fresh medium with 15 ng/ml IL-2, 15 ng/ml IL-7, and metabolites or inhibitors for 24 h followed by resting in fresh medium with 2 ng/ml IL-7 and metabolites or inhibitors for 12–16 h. The cells were then transferred into host mice for Tfh cell induction.

In vivo shRNAmir screening

As previously described (Chen et al., 2014), sorted naive SMARTA CD4+ T cells were cultured in 48-well plates precoated with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 for 24 h and were infected with retrovirus containing supernatant (Table S1) individually, followed by culturing in the presence of IL-2 and IL-7. Then the cells were mixed together, and Ametrinehi cells were collected by BD FACSAria II. Cells (1 × 106) were stored and served as "INPUT," while other cells were transferred into B6 host mice at 1 × 105 cells per mouse. The host mice were then sacrificed at day 8 after LCMV infection. Th1 cells (CXCR5−SLAMhi) and Tfh cells (CXCR5+SLAMlo) in the spleen were purified, and genomic DNA from each population was extracted, followed by PCR amplification of shRNAmir fragment and adaptor. The quality and concentration of the libraries generated were determined by an Agilent 2100 Bio analyzer (Agilent Technology). The libraries were sequenced on the BGISEQ-500 platform (BGI). The number of reads of each shRNAmir in the Tfh and Th1 samples was normalized to their respective number of reads in the input sample. The log2 ratios of the normalized Tfh divided by the normalized Th1 are calculated and plotted against each other.

In vitro Tfh-like cell culture

We used a protocol modified from a previous report (Oestreich et al., 2012) in that sorted naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO mice were cultured in 96-well plates precoated with 0.5 µg/ml anti-CD3ε and 1 µg/ml anti-CD28, and supplemented with 5 µg/ml anti–INF-γ, anti–IL-4, anti-TGFβ, 50 ng/ml IL-6, 5 ng/ml IL-12, and indicated chemicals. Cultured Tfh-like cells were harvested at day 6 for flow-cytometric analysis. Dead cells were excluded by fixable viability dye eFluor 450 (eBioscience).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of thymus, spleen, mLN, PP, and popliteal LN were prepared by mashing through a cell strainer. After depletion of red blood cells, the cells were stained with antibodies to surface markers. CXCR5 staining was performed in sequential steps, staining with purified anti-CXCR5 (2G8; BD PharMingen), biotinylated goat antibody to rat IgG (112–065-167; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and fluorochrome-conjugated streptavidin, in CXCR5 staining buffer (2% FBS and 2% normal mouse serum in PBS). For intracellular cytokine staining, the cells were stimulated for 4 h with 50 ng/ml PMA and 500 ng/ml ionomycin, in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences). Then the cells were stained with antibodies to cell surface markers, and fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Buffer (BD Biosciences) followed by staining with antibodies to cytokines. For intracellular transcriptional staining, the cells were stained with antibodies to cell surface markers, and were fixed and permeabilized with Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) followed by staining with antibodies to transcriptional markers in permeabilization buffer according to the manufacturer’s manual. For measurement of intracellular HIF-1α, purified CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 for 24 h. The cells were stained with antibodies to surface markers, fixed, and permeabilized with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set followed by staining with antibody to HIF-1α (R&D Systems). Data were acquired with the BD LSRFortessa and analyzed with FlowJo software. For cell sorting, single-cell suspension was prepared and immunostained with antibodies to indicated markers, followed by purification on a BD FACSAria II.

Immunofluorescence

Fresh frozen mLNs were cryosectioned and air-dried followed by cold acetone treatment for 10 min at −20°C. Slides were blocked with 10% FBS and 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature followed by overnight incubation in blocking buffer containing biotinylated PNA (Vector Laboratories) at 4°C. Slides were washed three times with PBS Tween-20 at room temperature before incubation in blocking buffer containing PE-CF594-labeled streptavidin (BD PharMingen), FITC-labeled anti-CD4 (eBioscience) and APC-labeled anti-IgD (eBioscience) for 2 h at room temperature. Slides were washed three times with PBS Tween-20 and PBS at room temperature followed by mounting. The images were captured by a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope and were processed using ZEN 2012 SP1 software (Carl Zeiss).

ELISA

96-well PolyStyrene Assay plates (Corning) were coated overnight with lysates of cells infected with LCMV and then inactivated by ultraviolet irradiation for safety. After incubation of sample serum, plates were incubated with biotin-conjugated goat antibody to mouse IgG (1030–08; SouthernBiotech), followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin (00–4100-94; eBioscience). The substrate solution containing o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (P8787; Sigma-Aldrich) was added and measured the absorption at 490 nm.

Immunoblot

Purified CD4+ T cells (2 × 106) from spleen of WT and VHL cKO mice were lysed in 100 µl cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, supplemented with proteinase inhibitor) on ice for 1 h followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (CWBIO) at 98°C for 10 min. Samples were loaded to 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were analyzed by immunoblotting with the appropriate antibodies, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody, and development with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (34087; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Seahorse extracellular flux assay

Purified naive CD4+ T cells from spleen of WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice were cultured in 24-well plates precoated with 2 µg/ml anti-CD3ε and 2 µg/ml anti-CD28 for 36 h. Then the cells were washed with PBS and seeded at 80,000 cells per well and analyzed using an XF96 extracellular analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Three consecutive measurements of ECAR (milli-pH unit, mpH/min) and OCR (pMoles O2/min) were obtained in XF base media at 37°C under basal conditions, in response to 1 µM oligomycin, 2 µM FCCP, 100 nM rotenone plus 1 µM antimycin A, 10 mM glucose, and 100 mM 2-DG. All chemicals used for these assays were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Glycolysis and glycolytic capacity were calculated from average of three measurements following addition of glucose and oligomycin, respectively. Basal OCR and maximal OCR were calculated from the average of three measurements before addition of oligomycin and following addition of FCCP, respectively.

RNA sequencing

The quality and concentration of the cDNA libraries generated were determined by Agilent 2100 Bio analyzer (Agilent Technology). The libraries were sequenced on BGISEQ-500 platform (BGI) using 50-bp pair-end reads. For heat map generation, expression values of transcripts were calculated as log2-transformed reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads. RNA sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive database with accession no. PRJNA532485.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from sorted cells or organs by Trizol (Ambion). cDNA was synthesized with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR was done with technical replicates using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad). β-actin was used as the reference for normalization. All the primers are in Table S2.

RIP–qRT-PCR

CD4+ T cells (1 × 107) transduced with empty vector (Myc-tagged) or vector encoding GAPDH were washed twice with PBS. After UV cross-linking, the cells were lysed in 400 µl cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM PMSF, proteinase inhibitor, and RNase inhibitor) at 4°C for 1 h followed by DNase treatment (M610A; Promega) at 37°C for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 10% of the supernatant was kept as input. Each sample was supplemented with 400 µl dilution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, proteinase inhibitor, and RNase inhibitor) and incubated with 10 µg anti-Myc antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with overnight rotation at 4°C. Then each sample was incubated with 150 µg protein A/G dynabeads (Life Technologies) for another 3 h. The beads were washed four times at 4°C with 500 µl wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.3% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, proteinase inhibitor, and RNase inhibitor). After washing, the beads were resuspended with 200 µl elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, proteinase inhibitor, and RNase inhibitor) in the presence of 80 µg proteinase K and incubated at 56°C with shaking for 1 h. The supernatant was collected, and RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent. Enrichment of RNA binding was analyzed by qRT-PCR using validated primers in Table S2. The ratio of precipitated RNA to input RNA was calculated.

MERIP–qRT-PCR

Purified naive CD4+ T cells from WT and VHL cKO mice were cultured in vitro with IL-2 and IL-7 for 48 h. For IAA treatment, purified naive CD4+ T cells were cultured in the media supplemented with 10 ng/ml IL-2 and 20 ng/ml IL-7 in the absence (Mock) or presence of 2.5 µM IAA for 48 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS followed by total RNA extraction with an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). m6A immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Dominissini et al., 2013). Briefly, 5 µg RNA was denatured at 70°C for 10 min. Each sample was supplemented with 20 µl 5 × immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 750 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, RNase inhibitor) and incubated with 1 µg m6A-specific antibody (61496; Active Motif) for 2 h with rotation at 4°C. The samples were incubated with 150 µg BSA-treated protein A/G dynabeads (Life Technologies) for another 2 h. The beads were washed four times at 4°C with 150 µl 1 × IP buffer (dilution of 5 × immunoprecipitation buffer with water), resuspended with 150 µl elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5% SDS, and RNase inhibitor) in the presence of 80 µg proteinase K, and incubated at 56°C with shaking for 1 h. RNA was precipitated by adding 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol with glycogen and overnight incubation at −80°C. The samples were centrifuged and washed with 75% ethanol. The air-dried RNA pellet was resuspended in 15 µl of RNase-free water. cDNA was synthesized from precipitated and input RNA. Enrichment of m6A modifications was analyzed by qRT-PCR using validated primers in Table S2. The ratio of precipitated RNA to input RNA was calculated for comparison of m6A modification levels.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SD except when indicated otherwise. n represents the number of animals per experiment. To assess the statistical significance, the P values were calculated using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0. We considered P values of <0.05 to be significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the development of Tfh cells in mLN and PP, and cell survival, proliferation, and cytokine production of CD4+ T cells upon LCMV infection. Fig. S2 shows the development of Tfh cells in mixed bone marrow chimeras, and cell survival, proliferation, and activation at steady state, day 3, or day 6 after LCMV infection. Fig. S3 shows the development and function of Tfh cells of donor cells transferred to Tcrbd−/− host mice. Fig. S4 shows the glycolysis and mitochondrial activity of CD4+ T cells from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice, and also the effects of ALDOA, MPC1, or citrate on Tfh cell development. Fig. S5 shows the m6A modification in T cells from WT, VHL cKO, and DKO mice or after IAA treatment. Table S1 lists shRNAmir oligonucleotides. Table S2 lists primers for qRT-PCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Shi, W. Zeng, and C. Dong of Tsinghua University for providing mouse strains for this study; Dr. N. Xiao of Xiamen University (Xiamen, China) for sharing glycolytic gene profiling data; and members of the Liu laboratory for support and discussion.

This work is supported by funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (YFA0505802 and YFC0903900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81630041), and the Tsinghua-Peking Center for Life Sciences to Y-C. Liu.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Y. Zhu designed and performed the experiments and analyzed data. Y. Zhao and L. Zou helped with the experiments of knockdown of glycolytic enzymes. D. Zhang helped with immunofluorescence experiments. Y. Zhu, D. Aki, and Y-C. Liu interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Abbott R.K., Thayer M., Labuda J., Silva M., Philbrook P., Cain D.W., Kojima H., Hatfield S., Sethumadhavan S., Ohta A., et al. . 2016. Germinal Center Hypoxia Potentiates Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination. J. Immunol. 197:4014–4020. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiba H., Takeda K., Kojima Y., Usui Y., Harada N., Yamazaki T., Ma J., Tezuka K., Yagita H., and Okumura K.. 2005. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J. Immunol. 175:2340–2348. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitfeld D., Ohl L., Kremmer E., Ellwart J., Sallusto F., Lipp M., and Förster R.. 2000. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J. Exp. Med. 192:1545–1552. 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Curtis J.D., Maggi L.B. Jr., Faubert B., Villarino A.V., O’Sullivan D., Huang S.C., van der Windt G.J., Blagih J., Qiu J., et al. . 2013. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 153:1239–1251. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Bélanger S., Frederick M.A., Li B., Johnston R.J., Xiao N., Liu Y.C., Sharma S., Peters B., Rao A., et al. . 2014. In vivo RNA interference screens identify regulators of antiviral CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Immunity. 41:325–338. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.H., Raybuck A.L., Stengel K., Wei M., Beck T.C., Volanakis E., Thomas J.W., Hiebert S., Haase V.H., and Boothby M.R.. 2016. Germinal centre hypoxia and regulation of antibody qualities by a hypoxia response system. Nature. 537:234–238. 10.1038/nature19334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty S. 2011. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29:621–663. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang E.V., Barbi J., Yang H.Y., Jinasena D., Yu H., Zheng Y., Bordman Z., Fu J., Kim Y., Yen H.R., et al. . 2011. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 146:772–784. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens A.L., Phan A.T., Stradner M.H., Fujimoto J.K., Nguyen J.V., Yang E., Johnson R.S., and Goldrath A.W.. 2013. Hypoxia-inducible factors enhance the effector responses of CD8(+) T cells to persistent antigen. Nat. Immunol. 14:1173–1182. 10.1038/ni.2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Salmon-Divon M., Amariglio N., and Rechavi G.. 2013. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 8:176–189. 10.1038/nprot.2012.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Dominissini D., Rechavi G., and He C.. 2014. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15:293–306. 10.1038/nrg3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshan K., and Chawla A.. 2014. Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32:609–634. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcin E.D. 2019. GAPDH as a model non-canonical AU-rich RNA binding protein. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 86:162–173. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossage L., Eisen T., and Maher E.R.. 2015. VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 15:55–64. 10.1038/nrc3844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R.J., Poholek A.C., DiToro D., Yusuf I., Eto D., Barnett B., Dent A.L., Craft J., and Crotty S.. 2009. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 325:1006–1010. 10.1126/science.1175870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.H., Rott L.S., Clark-Lewis I., Campbell D.J., Wu L., and Butcher E.C.. 2001. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 193:1373–1381. 10.1084/jem.193.12.1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Elly C., Park Y., and Liu Y.C.. 2015. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase VHL Regulates Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α to Maintain Regulatory T Cell Stability and Suppressive Capacity. Immunity. 42:1062–1074. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Li D., Zhang X., Wan Q., Zhang W., Zheng M., Zou L., Elly C., Lee J.H., and Liu Y.C.. 2018. E3 Ligase VHL Promotes Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Maturation and Function via Glycolysis Inhibition and Induction of Interleukin-33 Receptor. Immunity. 48:258–270.e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurieva R.I., Chung Y., Hwang D., Yang X.O., Kang H.S., Ma L., Wang Y.H., Watowich S.S., Jetten A.M., Tian Q., and Dong C.. 2008. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 29:138–149. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurieva R.I., Chung Y., Martinez G.J., Yang X.O., Tanaka S., Matskevitch T.D., Wang Y.H., and Dong C.. 2009. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 325:1001–1005. 10.1126/science.1176676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich K.J., Mohn S.E., and Weinmann A.S.. 2012. Molecular mechanisms that control the expression and activity of Bcl-6 in TH1 cells to regulate flexibility with a TFH-like gene profile. Nat. Immunol. 13:405–411. 10.1038/ni.2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich K.J., Read K.A., Gilbertson S.E., Hough K.P., McDonald P.W., Krishnamoorthy V., and Weinmann A.S.. 2014. Bcl-6 directly represses the gene program of the glycolysis pathway. Nat. Immunol. 15:957–964. 10.1038/ni.2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenius A., Bachmann M.F., Zinkernagel R.M., and Hengartner H.. 1998. Virus-specific MHC-class II-restricted TCR-transgenic mice: effects on humoral and cellular immune responses after viral infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan A.T., Doedens A.L., Palazon A., Tyrakis P.A., Cheung K.P., Johnson R.S., and Goldrath A.W.. 2016. Constitutive Glycolytic Metabolism Supports CD8+ T Cell Effector Memory Differentiation during Viral Infection. Immunity. 45:1024–1037. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray J.P., Staron M.M., Shyer J.A., Ho P.C., Marshall H.D., Gray S.M., Laidlaw B.J., Araki K., Ahmed R., Kaech S.M., and Craft J.. 2015. The Interleukin-2-mTORc1 Kinase Axis Defines the Signaling, Differentiation, and Metabolism of T Helper 1 and Follicular B Helper T Cells. Immunity. 43:690–702. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaerli P., Willimann K., Lang A.B., Lipp M., Loetscher P., and Moser B.. 2000. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J. Exp. Med. 192:1553–1562. 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield C.J., and Ratcliffe P.J.. 2004. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:343–354. 10.1038/nrm1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G.L. 2007. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci. STKE. 2007:cm8 10.1126/stke.4072007cm8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.Z., Wang R., Huang G., Vogel P., Neale G., Green D.R., and Chi H.. 2011. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J. Exp. Med. 208:1367–1376. 10.1084/jem.20110278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitkovsky M., and Lukashev D.. 2005. Regulation of immune cells by local-tissue oxygen tension: HIF1 alpha and adenosine receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:712–721. 10.1038/nri1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa C.G., Linterman M.A., Yu D., and MacLennan I.C.. 2016. Follicular Helper T Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34:335–368. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao N., Eto D., Elly C., Peng G., Crotty S., and Liu Y.C.. 2014. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch is required for the differentiation of follicular helper T cells. Nat. Immunol. 15:657–666. 10.1038/ni.2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Li X., Liu D., Li J., Zhang X., Chen X., Hou S., Peng L., Xu C., Liu W., et al. . 2013. Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystander B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature. 496:523–527. 10.1038/nature12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Tan A.H., Hu X., Athanasopoulos V., Simpson N., Silva D.G., Hutloff A., Giles K.M., Leedman P.J., Lam K.P., et al. . 2007. Roquin represses autoimmunity by limiting inducible T-cell co-stimulator messenger RNA. Nature. 450:299–303. 10.1038/nature06253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]