Abstract

A new study reports that human blood vessel organoids can be generated through the directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Use of these blood vessel organoids to model diabetic vasculopathy led to the identification of a new potential therapeutic target, suggesting this system could have translational value for studies of diabetes complications.

Advances in 3D culture techniques have led to the development of research tools that have great potential for translational research. Three-dimensional aggregates of cells called organoids, which mimic the structure and function of in vivo organs can provide new insights into human organ development and disease pathology. Organoids can be generated either from tissue stem cells or from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells1. The first organoid culture system was established using intestinal stem cells using culture conditions that mimicked the in vivo environment2. Since then, protocols involving the sequential application of growth factors and signals at specific combinations and concentrations have been developed to enable the directed differentiation of stem cells into organoids representative of various organs including the intestine, liver, lung, brain, pancreas, stomach, and kidneys3,4. Now, Wimmer et al. describe the directed differentiation of human PSCs into blood vessel organoids and show that these organoids can be used to model diabetic vasculopathy5.

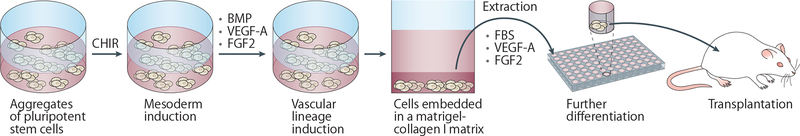

The in vitro differentiation of stem cells into vascular endothelial and mural cells was first reported nearly 20 years ago6. At that time, a stochastic differentiation approach was used to generate Flk1+E-cadherin− vascular progenitor cells from mouse ESCs. Following a purification step using flowcytometry sorting, these cells were differentiated into endothelial and mural cells in a 3D culture system using collagen gels. Wimmer et al. now show that human blood vessel organoids can be generated from human ESCs and induced PSCs through directed differentiation without the need for cell sorting during the differentiation process5. Treatment of stem cell aggregates in suspension culture with the GSK3 inhibitor CHIR99021 to activate Wnt signalling promoted mesoderm lineage differentiation. Vascular lineage induction was then achieved by modulating bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) levels. Cell aggregates were subsequently embedded in a mixed Matrigel–collagenI gel to facilitate the formation of a vascular network. At around day 18 of differentiation, individual cell aggregates were extracted from the gels and further differentiated with fetal bovine serum, VEGF-A and FGF2 in suspension culture (Fig. 1). The resulting organoids comprised networks of CD31+ endothelial cells surrounded by platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta-positive (PDGFR-β+) pericytes as well as small populations of CD90+CD73+CD44+ mesenchymal stem-like cells and CD45+ haematopoietic cells. Transplantation of the organoids into mice led to the formation of perfusable vascular lumens containing human endothelia.

Figure 1.

Protocol for the generation of human blood vessel organoids to model diabetic vasculopathy. The directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into human blood vessel organoids involves the treatment of stem cell aggregates in suspension culture with CHIR99021 (CHIR) to induce mesoderm differentiation. Vascular induction is then promoted through the addition of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), after which cell aggregates are embedded in a Matrigel–collagen I gel to facilitate the formation of a vascular network. Individual cell aggregates are then extracted from the gels and further differentiated with fetal bovine serum (FBS), VEGF-A and FGF2 in suspension culture, and the resulting organoids transplanted into diabetic mice.

The most interesting aspect of this new study is perhaps the use of these vessel organoids to model diabetic vasculopathy5. The researchers show that culturing the vessel organoids in high glucose media for up to 3 weeks induces thickening of vascular basement membranes — a key feature of diabetic microvasculopathy. Addition of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6, to the media further enhanced this thickening. Moreover, human vessel organoids transplanted into mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes exhibited similar features to those of organoids cultured under high-glucose conditions, with thickening of the basement membrane, vessel regression and loss of endothelial cells. Finally, the researchers used a drug screening approach to identify DLL4–NOTCH3 signalling as a driver of this process, and showed that inhibition of NOTCH3 alleviated the microvascular pathologies in transplanted mice.

Microvasculopathy is a major complications of diabetes mellitus, and can eventually lead to blindness, kidney failure, cardiovascular disease and amputation of lower limbs. Organ dysfunction occurs through a variety of mechanisms, including insufficient tissue oxygenation, impaired cell trafficking, and plasma and blood leakage from vessels. The ability to recapitulate microvasculopathy in human vessel organoids will provide valuable opportunities to further understand the underlying pathomechanisms of diabetic complications and to test new therapeutic approaches.

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is one of the most common and devastating complications of diabetes, for which limited treatments exist. The use of organoids to study DKD has been limited by the finding that kidney organoids show limited vascularization in vitro. The formation of vasculature networks in kidney organoids is enhanced following their transplantation into mice, and similar to the findings by Wimmer et al.5 The vasculature of human kidney organoids connects to the mouse vasculature following transplantation7. However, xenogeneic vascularized organoids might not fully recapitulate the pathophysiology of DKD in humans. In addition, protocols that require animal transplantation limit the scalability of these studies. To overcome these issues, an in vitro approach has been developed whereby vascularization of whole kidney organoids can be achieved in vitro by exposing organoids within engineered chips to a fluidic environment8. In addition to inducing vascularization, exposure to flow enhanced the maturation of nephron epithelial cells in these organoids, suggesting that culture systems that better mimic the in vivo environment may provide better platforms for modeling kidney and vascular development, and for the study of diabetic complications in human cells. Multi-organ on a chip approach using vascularized organoids including the kidney and vessel may provide better in vitro systems to study interorgan communications in diabetic conditions.

Although organoids have potential to be highly valuable for the study of development and disease, the reproducibility of protocols is a major challenge. For example, a 2018 study reported poor inter-laboratory reproducibility of gene expression signatures in PSC-derived neurons generated using a well-defined differentiation protocol9. A more recent study used single cell RNA-sequencing to demonstrate interexperimental and interclonal variation in the differentiation of kidney organoids within the same laboratory10. Quality control is necessary for the reproducible generation of organoids; however, markers and methods that enable such reproducibility have not been defined well. In fact, quantitative quality control steps such as progenitor maker expression during directed differentiation were not clearly described by Wimmer et al5. Detailed protocols with appropriate quality control such as marker expression analyses at each step of directed differentiation are needed for researchers to reliably reproduce protocols used for organoid generation.

In summary, Wimmer et al. demonstrate that human blood vessel organoids can be generated from human PSCs by directed differentiation, and show that these organoids can be used to model diabetic vasculopathy and identify potential therapeutic targets. Many challenges remain in using such systems for the study of diabetic vasculopathies, including the limited in vitro vascularization of organoid systems such as kidney organoids, and reproducibility issues, but this study helps move the field forward by providing an additional tool with which to study diabetic complications in human vascular tissues.

Footnotes

Competing interests

R.M. is a co-inventor on patents (PCT/US16/52350) relating to organoid technologies that are assigned to Partners Healthcare.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Fatehullah A, Tan SH & Barker N Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nature cell biology 18, 246–254, doi: 10.1038/ncb3312 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato T et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265, doi: 10.1038/nature07935 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morizane R & Bonventre JV Kidney Organoids: A Translational Journey. Trends in molecular medicine 23, 246–263, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.01.001 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morizane R et al. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nature biotechnology 33, 1193–1200, doi: 10.1038/nbt.3392 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wimmer RA et al. Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature 565, 505–510, doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0858-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita J et al. Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature 408, 92–96, doi: 10.1038/35040568 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Berg CW et al. Renal Subcapsular Transplantation of PSC-Derived Kidney Organoids Induces Neo-vasculogenesis and Significant Glomerular and Tubular Maturation In Vivo. Stem cell reports 10, 751–765, doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.041 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homan K et al. Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro. Nature methods 16, 255–262, doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0325-y (2019) [PubMed: 30742039] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpato V et al. Reproducibility of Molecular Phenotypes after Long-Term Differentiation to Human iPSC-Derived Neurons: A Multi-Site Omics Study. Stem cell reports 11, 897–911, doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.08.013 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phipson B et al. Evaluation of variability in human kidney organoids. Nature methods 16, 79–87, doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0253-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]