ABSTRACT

The advent of engineered T cells as a form of immunotherapy marks the beginning of a new era in medicine, providing a transformative way to combat complex diseases such as cancer. Following FDA approval of CAR T cells directed against the CD19 protein for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B cell lymphoma, CAR T cells are poised to enter mainstream oncology. Despite this success, a number of patients are unable to receive this therapy due to inadequate T cell numbers or rapid disease progression. Furthermore, lack of response to CAR T cell treatment is due in some cases to intrinsic autologous T cell defects and/or the inability of these cells to function optimally in a strongly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. We describe recent efforts to overcome these limitations using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, with the goal of enhancing potency and increasing the availability of CAR-based therapies. We further discuss issues related to the efficiency/scalability of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in CAR T cells and safety considerations. By combining the tools of synthetic biology such as CARs and CRISPR/Cas9, we have an unprecedented opportunity to optimally program T cells and improve adoptive immunotherapy for most, if not all future patients.

KEYWORDS: CAR T cell, CRISPR/Cas9, cancer immunotherapy, genome editing

Striking results from multiple centers have demonstrated that adoptive transfer of genetically-engineered T cells can induce durable, complete remissions in patients with a variety of hematologic cancers. In the CAR approach, genes encoding synthetic antigen receptors are introduced into T cells, which endows these lymphocytes with the ability to bind pre-defined surface antigens on tumors1-3. The antibody-derived extracellular domain of a CAR allows T cells to recognize intact proteins independently of antigen processing and presentation. This antigen-binding molecule is tandemly linked to an intracellular signaling moiety that mediates T cell activation and cytolytic activity. Thus, T cells can be programmed with CARs to detect and kill antigen-expressing cells (reviewed in 4). Clinical data since 2010 indicates that CAR T cells have the potential to be curative in advanced leukemia patients5,6, with unprecedented complete response rates of >80–90% in adults and children with relapsed/refractory ALL7-9. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), we have observed durable remissions beyond 5 years, accompanied by complete eradication of minimum residual disease from the bone marrow10. As a result of these clinical findings and concordant results from multicenter trials, a CAR directed against the CD19 protein that was developed at the University of Pennsylvania was recently approved by the FDA11 to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)7-9 and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)12,13. CAR T cells are also beginning to demonstrate robust anti-tumor activity in patients with multiple myeloma14-16.

Despite the clinical efficacy of CAR T cell therapy in liquid tumor indications, there are several barriers that limit successful treatment for many patients. CAR T cells do not expand and persist in some individuals, including the majority of subjects with CLL10,17. A certain degree of CAR T cell proliferation, engraftment and persistence appears essential for clinical benefit7,8,10,17. We have recently demonstrated that lack of response to CAR therapy may be due to intrinsic autologous T cell defects, which often prevent the attainment of therapeutic levels of in vivo CAR T cell expansion17. In some cancers (e.g., ALL), patients have rapidly progressive disease that precludes therapy with genetically-engineered T lymphocytes due to the time required to generate an autologous CAR T cell infusion product. Additionally, it is sometimes not practical to collect sufficient numbers of T cells for CAR T cell manufacturing due to lymphopenia from recent or prior therapy and/or underlying disease18. In other cases, the proliferative capacity of T cells during large-scale culture is poor, leading to a failure in meeting clinical dose at the completion of the CAR T cell production process19,20. Finally, although CAR T cells are revolutionizing therapy of hematologic malignancies, the field awaits a clear demonstration of clinical efficacy for solid tumors. A major barrier to the success of CAR T cell therapy of these much more common non-hematopoietic cancers is determining how to optimally enhance the function and persistence of these cells in toxic tumor microenvironments (reviewed in 21-24). With the emergence of easily multiplexable precision genome editing using CRISPR/Cas925, there is an opportunity to overcome many of these obstacles to CAR T cell therapy and accelerate generalization of this treatment approach to standard medical management of a variety of cancers.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology originates from the type II acquired immune system in bacteria and archaea. This type II system provides protection against invading viruses (i.e., bacteriophages), plasmids and other types of foreign nucleic acids26-28. Upon activation of this system, short fragments are cleaved from invading DNA and incorporated at the CRISPR locus between repeat sequences that are encoded as arrays within the prokaryotic host genome (reviewed in 29). CRISPR arrays consist of “protospacers” that are short pieces of DNA derived from and matching the corresponding parts of invading (e.g., viral) DNA. These elements allow the bacterium or archaeon to form “memory” so that if the same or a similar invader is subsequently encountered, the prokaryotic host can generate RNA segments from the CRISPR arrays to target the foreign DNA for destruction. In this process, transcripts from the CRISPR repeat arrays are processed into CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), which hybridize with a second transactivating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA)30. Following maturation of pre-crRNA, the crRNA/tracrRNA duplex recruits the Cas9 DNA endonuclease, resulting in the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex31. The encoded portion of the crRNA corresponding to the protospacer then guides the nuclease protein to a complementary target DNA and cleaves it, provided that it is adjacent to a short sequence known as a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Although the PAM sequence is recognized by the CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex, it does not become integrated into the host genome with the protospacer sequence32-35. CRISPR/Cas-mediated mutagenesis may result in amino acid deletions, insertions or frameshift alterations that introduce pre-mature stop codons within the open reading frame of the targeted gene. This can lead to translation of functionally impaired proteins that are essential to the foreign invader. Excision of particular target sequences would result in severe damage of the template used for replication of the pathogenic genome.

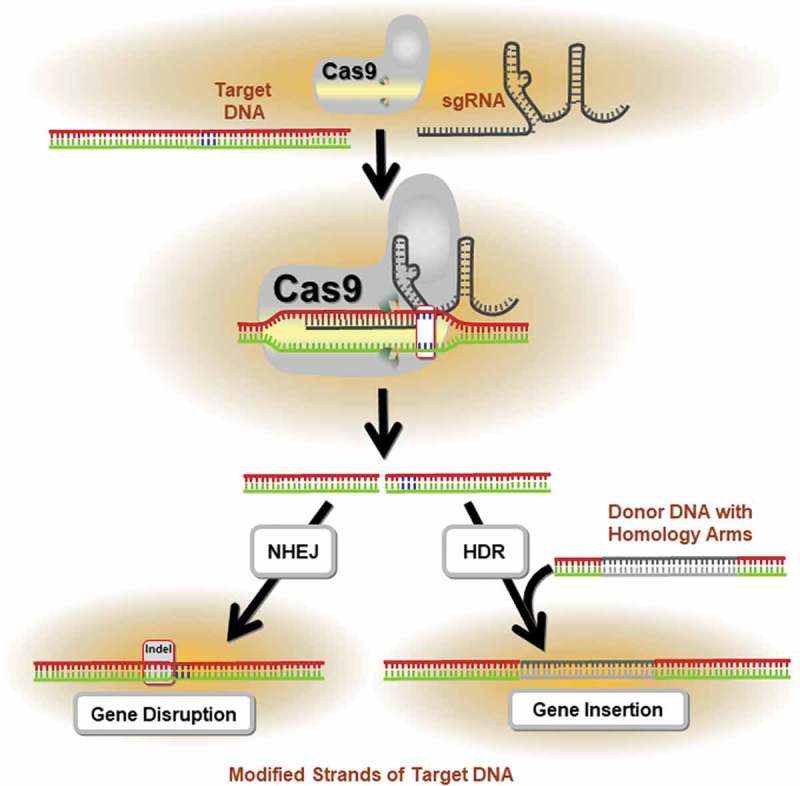

Jinek and colleagues demonstrated that Cas9 protein isolated from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) can associate with a crRNA/tracrRNA duplex to induce double-strand breaks (DSB) at a target DNA sequence31. This binding occurs via Watson-Crick base pairing of crRNA to target DNA. Importantly, it was shown that SpCas9 endonuclease could be programmed to bind and cleave a DNA sequence without RNA complex formation31. Cas9 protein can therefore be directed to a desired genomic locus by a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to create a DSB. These DSBs are typically repaired through an error prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or a homology-directed repair (HDR) mechanism. DSBs are corrected, but the open reading frame of the gene is disrupted by small insertion/deletion (indels) mutations at the break site. Genetic knock-outs can be created through the targeting of Cas9 to create indels within protein-coding exons (Figure 1). If the encoded protein domain is functionally essential, CRISPR/Cas9-induced indels produce a high frequency of null mutations36. Following publication of two seminal reports showing feasibility of site-specific human genome engineering with the CRISPR/Cas9 system37,38, the field of gene editing was revitalized. In comparison to other programmable nucleases such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), the CRISPR/Cas9 system possesses the advantages of ease, flexibility and the potential for multiplex gene editing (reviewed in 39). Thus, in the setting of CAR T cell therapy, it is now possible to simultaneously target multiple genes and accomplish loss of function of virtually any genetic or epigenetic target using CRISPR/Cas9.

Figure 1.

Application of the CRISPR/Cas9 System in precision genome editing. The mechanism of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis is shown. The single guide RNA (sgRNA) forms a ribonucleoprotein complex with the Cas9 endonuclease and directs the enzyme to the target DNA. Following cleavage of the sequence, repair mechanisms (i.e., homology directed repair, HDR; non-homologous end joining, NHEJ) are activated to mend the DNA damage. This often results in the insertion or deletion (indel) of nucleotides, which may alter the reading frame of the gene through the introduction of pre-mature stop codons. If the encoded protein domain is functionally essential, these indels generate a high proportion of null mutations.

Because too many patients are unable to receive engineered autologous T cells due to the aforementioned intrinsic defects or inadequate numbers of lymphocytes available for manufacturing, development of “universal,” healthy donor-derived infusion products using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing would rapidly expand application of CAR T cell-based therapies for cancer (Figure 2). The main concerns with using such “off-the-shelf” CAR T cell products are potential induction of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) by ex vivo activated allogeneic T cells and rapid rejection by the host. To minimize the risks associated with administering universal CAR T cells, CRISPR/Cas9 technology can be used to knock-out endogenous αβ T cell receptors (TCRs) on adoptively-transferred donor lymphocytes that can recognize alloantigens in an unrelated recipient, which would result in GVHD. In addition, elimination of beta-2-microglobulin (β2M), an essential subunit of human leukocyte antigen class I (HLA-I) proteins, would prevent rapid elimination of allogeneic cells expressing foreign HLA-I molecules. Pre-clinical data indicate that multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology can be highly effective at simultaneously knocking-out the endogenous TCR as well as β2M to produce universal CD19-directed CAR T cells. These cells exhibited robust anti-tumor activity and did not induce xenogeneic GVHD in mice engrafted with leukemia40. However, the susceptibility of allogeneic CRISPR/Cas9-modified anti-CD19 CAR T cells to rejection in vivo by natural killer (NK) cells due to the absence of HLA-I or elevated levels of HLA class II following T cell activation was not assessed in the above studies. The issue of NK cell-mediated host-versus-graft rejection may be circumvented in the clinic through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-out of stimulatory NK cell ligands, overexpression of non-classical HLA class I molecules on allogeneic T cells (e.g., HLA-E41) (Figure 2), administration of chemotherapy and/or infusion of NK cell-specific monoclonal antibodies to deplete NK cells42.

Figure 2.

Creation of Universal CAR T cells. A strategy for generating an “off-the-shelf,” allogeneic CAR T cell product is depicted. CRISPR/Cas9 technology is used to knock-out the endogenous TCR as well as HLA class I molecules to prevent graft-versus-host disease and host-versus-graft rejection of adoptively-transferred CAR T cells. Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing can also be applied to simultaneously ablate inhibitory receptors such as PD-1. Overexpression of non-classical HLA class I molecules (e.g., HLA-E) may further prevent rejection of allogeneic CAR T cells and thus potentiate the persistence of these lymphocytes in patients.

Overexpression of negative checkpoint regulators in conjunction with up-regulation of cognate inhibitory ligands in the tumor microenvironment may also limit CAR T cell persistence as well as function, and this will be associated with lack of clinical benefit. We and others have shown that modulation of the programmed death-ligand 1/programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-L1/PD-1) axis may enhance the anti-tumor activity of endogenous or genetically-redirected T cells43-50. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that T cell dysfunction is regulated in part by co-expression of multiple negative checkpoint regulators, including PD-1. High levels of other inhibitory receptors such as T cell membrane protein-3 (TIM-3), lymphocyte-activation protein-3 (LAG-3), T cell Ig and ITIM domain (TIGIT), cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) are also observed following persistent tumor antigen encounter (reviewed in 51,52). The inhibitory functions of these receptors are thought to be non-redundant, but it is now recognized that they may synergize to cause immune cell exhaustion53,54. Although concurrent administration of checkpoint inhibitors with CAR T cells may reinvigorate these lymphocytes in the setting of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironement, systemic delivery of checkpoint-blocking antibodies is associated with severe immune-related adverse events in some patients55. One way to overcome this limitation is by taking advantage of the flexibility of CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing to disrupt single49,50 or multiple genes encoding inhibitory receptors (Figure 2). The feasibility of generating universal, allogeneic T cells with multiple negative regulators (i.e., PD-1 and CD95/Fas death receptor) knocked-out has been demonstrated40. In addition to inhibitory receptors, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ablation of other modulators of CAR T cell signaling such as diacylglycerol kinase may render these cells resistant to soluble immunosuppressive factors like TGFβ and prostaglandin E2 present in the tumor microenvironment40. Finally, the CRISPR/Cas9 system in combination with viral or non-viral transgene delivery methods can be used to direct CARs and/or other potency-enhancing T cell modulators into specific genomic loci (e.g., TRAC encoding the endogenous T cell receptor constant alpha chain and/or inhibitory receptor genes)56,57. This new powerful technology has the potential to revolutionize CAR T cell-based therapies for cancer.

Although CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing can be used to overcome several barriers present in conventional CAR T cell therapy, there are a number of challenges to clinical translation that must be addressed. Successful production of clinical grade cell and RNA products requires detailed process planning prior to execution, compliance with GMP regulations and FDA guidance, and operation in the context of reliable infrastructure guided by a pre-defined quality plan. For human trials, large-scale protocols for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated target ablation in mature T cells must be established. These approaches need to facilitate the transfer of sgRNA, Cas9 as well as a gene encoding the CAR, preserve cell viability, and permit robust in vitro expansion of engineered T cells following genetic manipulation. These methods may include transduction of CRISPR/Cas9 components and CAR transgenes using retroviruses or lentiviruses58,59 or with non-integrating viruses, such as adenoviruses and adenovirus-associated viruses (AAV)60,61. Alternatively, CRISPR/Cas9 delivery may be accomplished by using sgRNA complexed with Cas9 in the form of ribonucleoproteins (RNP)62, which have demonstrated effective gene knock-out when electroporated into human T cells63,64. A major advantage of this approach is the potential to achieve a high degree of transfection/editing efficiency and modification of multiple genes using a single electroporation step, without the toxicity associated with other methods such as DNA nucleofection in T cells49,65. Electrotransfer of RNP complexes also has the potential for generating high frequencies of gene-edited CAR T cells and avoiding constitutive CRISPR/Cas9-sgRNA expression, which may be a regulatory concern related to the use of certain viral delivery protocols. While production of CRISPR/Cas9-edited CAR T cells is feasible using large-scale transfection systems, a potential challenge is reaching target infusion doses at the time of cell harvest due to a decrease in lymphocyte viability following electroporation, and genome manipulation which increases genetic instability. Furthermore, in the context of creating “off-the-shelf” allogeneic CAR T cells, it is no longer possible to stimulate T cells for expansion using pan-TCR activation (e.g., using anti-CD3 agonistic antibodies) following deletion of the endogenous TCR. The addition of exogenous cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-15 to cultures following electroporation with CRISPR reagents and/or adding CAR-specific targets may potentiate the generation of sufficient numbers of gene-edited CAR T cells for therapeutic applications64.

Another obstacle to clinical translation of CRISPR/Cas9-edited CAR T cells is the potential for Cas9-sgRNA binding and cleavage of sequences that are highly similar to the target DNA sequence. This may lead to mutations at undesired sites in the genome66,67, chromosomal rearrangements such as inversions and translocations (i.e., due to re-ligation between breaks on different chromosomes occurs)67-71, or large deletions and complex rearrangements due to repair of CRISPR/Cas9-induced double-strand DNA breaks (Nat Biotechnol. 2018 Sep;36(8):765-771. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4192. Epub 2018 Jul 16.). Off-target editing of critical genes such as those encoding transcription factors would be predicted to have wide-ranging ramifications. Approaches to diminish off-target CRISPR/Cas9 editing include altering the Cas9 endonuclease with novel PAM specificities72, introducing mutations in one of the two nuclease domains of Cas9 so that it nicks one strand of the target DNA31,37,73, use of high-fidelity Cas9 variants74 and employing truncated sgRNAs75 (reviewed in 76,77). Systematic evaluations of off-target editing in CAR-engineered T cells using a combination of cytogenetics, in silico prediction methods, whole-exome sequencing, or other analysis techniques will be critical for cell infusion product release and may minimize the likelihood of genotoxicity following adoptive transfer into patients.

As the first FDA-approved engineered T cell therapy to come to market, CAR T cells have the potential to transform treatment strategies for a multitude of incurable cancers. The central limitations in the current of CAR T cells for hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic tumors include lack of sufficient numbers of a patient’s own T cells for manufacturing in the face of progressive disease or following multiple rounds of chemotherapy, limited in vivo efficacy of these autologous lymphocytes due to intrinsic T cell defects, and the susceptibility of CAR T cells to strongly immunosuppressive microenvironments. The use of CRISPR/Cas9-enhanced immune-gene cell therapy to overcome many of these challenges is now a reality, and our center is currently conducting the first-in-human trial of CRISPR/Cas9 technology using multiplexing with sgRNAs to enhance the efficacy of engineered T cells in cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT0339944). Thus, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing provides the promise of further streamlining immunotherapy, perhaps through the creation of universal, “off-the-shelf” cellular products or engineering these cells to overcome resistance in the setting of hematopoietic as well as non-hematopoietic malignancies. Although several challenges remain regarding the safety, efficiency and scalability of this approach, CRISPR/Cas9 technology will undoubtedly reign in a new era of CAR T cell-based therapies for cancer.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

J.A.F. and M.M.D. hold patents related to CAR T cell therapy and receive research funding from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation as well as Tmunity Therapeutics. The remaining authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kuwana Y, Asakura Y, Utsunomiya N, Nakanishi M, Arata Y, Itoh S, Nagase F, Kurosawa Y.. Expression of chimeric receptor composed of immunoglobulin-derived V regions and T-cell receptor-derived C regions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:960–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:10024–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irving BA, Weiss A. The cytoplasmic domain of the T cell receptor zeta chain is sufficient to couple to receptor-associated signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1991;64:891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359:1361–65. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, June CH. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1507–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, Bader P, Verneris MR, Stefanski HE, Myers GD, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JH, Riviere I, Gonen M, Wang X, Senechal B, Curran KJ, Sauter C, Wang Y, Santomasso B, Mead E, et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:449–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter DL, Hwang WT, Frey NV, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, Loren AW, Bagg A, Marcucci KT, Shen A, Gonzalez V, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Science translational medicine. 2015;7:303ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullard A. FDA approves first CAR T therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2017;16:669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak O, Brogdon JL, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Bhoj V, Landsburg D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2545–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Braunschweig I, Oluwole OO, Siddiqi T, Lin Y, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garfall AL, Maus MV, Hwang WT, Lacey SF, Mahnke YD, Melenhorst JJ, Zheng Z, Vogl DT, Cohen AD, Weiss BM, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells against CD19 for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1040–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garfall AL, Stadtmauer EA, Hwang WT, Lacey SF, Melenhorst JJ, Krevvata M, Carroll MP, Matsui WH, Wang Q, Dhodapkar MV, et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T cells with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation for refractory multiple myeloma. JCI Insight. 2018;3. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos CA, Savoldo B, Torrano V, Ballard B, Zhang H, Dakhova O, Liu E, Carrum G, Kamble RT, Gee AP, et al. Clinical responses with T lymphocytes targeting malignancy-associated kappa light chains. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2588–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI86000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Gohil M, Lundh S, Boesteanu AC, Wang Y, O’Connor RS, Hwang W-T, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med. 2018;24:563–71. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh N, Perazzelli J, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Early memory phenotypes drive T cell proliferation in patients with pediatric malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:320ra3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraietta JA, Beckwith KA, Patel PR, Ruella M, Zheng Z, Barrett DM, Lacey SF, Melenhorst JJ, McGettigan SE, Cook DR, et al. Ibrutinib enhances chimeric antigen receptor T-cell engraftment and efficacy in leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:1117–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, Fraietta JA, Patel PR, Scholler J, Barrett DM, Lundh SM, Davis MM, Bedoya F, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1100–09. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long KB, Young RM, Boesteanu AC, Davis MM, Melenhorst JJ, Lacey SF, DeGaramo DA, Levine BL, Fraietta, JA. CAR T cell therapy of non-hematopoietic malignancies: detours on the road to clinical success. Front Immunol. 2018;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knochelmann HM, Smith AS, Dwyer CJ, Wyatt MM, Mehrotra S, Paulos CM. CAR T cells in solid tumors: blueprints for building effective therapies. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1740. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidts A, Maus MV. Making CAR T cells a solid option for solid tumors. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2593. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Aloia MM, Zizzari IG, Sacchetti B, Pierelli L, Alimandi M, Barbati C, Morello F, Alfè M, Di Blasio G, Gargiulo V, et al. CAR-T cells: the long and winding road to solid tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:282. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods. 2013;10:957–63. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, Romero DA, Horvath P. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvath P, Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science. 2010;327:167–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1179555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482:331–38. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deltcheva E, Chylinski K, Sharma CM, Gonzales K, Chao Y, Pirzada ZA, Eckert MR, Vogel J, Charpentier E. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature. 2011;471:602–07. doi: 10.1038/nature09886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lillestol RK, Shah SA, Brugger K, Redder P, Phan H, Christiansen J, Garrett RA. CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:259–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deveau H, Barrangou R, Garneau JE, Labonte J, Fremaux C, Boyaval P, Romero DA, Horvath P, Moineau S. Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1390–400. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doudna JA, Charpentier E, Duzhko VV, Russell TP, Emrick T Genome editing . The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1255826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang F, Doudna JA. CRISPR-Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:505–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi J, Wang E, Milazzo JP, Wang Z, Kinney JB, Vakoc CR. Discovery of cancer drug targets by CRISPR-Cas9 screening of protein domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:661–67. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–26. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adli M. The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04252-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren J, Zhang X, Liu X, Fang C, Jiang S, June CH, Zhao Y. A versatile system for rapid multiplex genome-edited CAR T cell generation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17002–11. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torikai H, Reik A, Soldner F, Warren EH, Yuen C, Zhou Y, Crossland DL, Huls H, Littman N, Zhang Z, et al. Toward eliminating HLA class I expression to generate universal cells from allogeneic donors. Blood. 2013;122:1341–49. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-478255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi EI, Reimann KA, Letvin NL. In vivo natural killer cell depletion during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2008;82:6758–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02277-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chong EA, Melenhorst JJ, Lacey SF, Ambrose DE, Gonzalez V, Levine BL, June CH, Schuster SJ. PD-1 blockade modulates chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells: refueling the CAR. Blood. 2017;129:1039–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-738245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rafiq S, Yeku OO, Jackson HJ, Purdon TJ, van Leeuwen DG, Drakes DJ, Song M, Miele MM, Li Z, Wang P, et al. Targeted delivery of a PD-1-blocking scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:847–56. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, Anagnostou V, Cottrell TR, Hellmann MD, Zahurak M, Yang SC, Jones DR, Broderick S, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1976–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rs H, Jc S, Kowanetz M, Gd F, Hamid O, Ms G, Sosman JA, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Gettinger SN, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–67. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su S, Hu B, Shao J, Shen B, Du J, Du Y, Zhou J, Yu L, Zhang L, Chen F, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated efficient PD-1 disruption on human primary T cells from cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20070. doi: 10.1038/srep20070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rupp LJ, Schumann K, Roybal KT, Gate RE, Ye CJ, Lim WA, Marson A. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PD-1 disruption enhances anti-tumor efficacy of human chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:737. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mirzaei HR, Rodriguez A, Shepphird J, Brown CE, Badie B. Chimeric antigen receptors t cell therapy in solid tumor: challenges and clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1850. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turnis ME, Andrews LP, Vignali DA. Inhibitory receptors as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:1892–905. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2187–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Odorizzi PM, Wherry EJ. Inhibitory receptors on lymphocytes: insights from infections. J Immunol. 2012;188:2957–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eyquem J, Mansilla-Soto J, Giavridis T, van der Stegen SJ, Hamieh M, Cunanan KM, Odak A, Gönen M, Sadelain M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–17. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth TL, Puig-Saus C, Yu R, Shifrut E, Carnevale J, Li PJ, Hiatt J, Saco J, Krystofinski P, Li H, et al. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature. 2018;559:405–09. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams MR, Fricano-Kugler CJ, Getz SA, Skelton PD, Lee J, Rizzuto CP, Geller JS, Li M, Luikart BW. A retroviral CRISPR-Cas9 system for cellular autism-associated phenotype discovery in developing neurons. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25611. doi: 10.1038/srep25611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, Zetsche B, Shalem O, Wu X, Makarova KS, et al. In vivo genome editing using staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–91. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A, Habib N, Li Y, Trombetta J, Sur M, Zhang F. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:102–06. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, Kim J, Kim JS. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 2014;24:1012–19. doi: 10.1101/gr.171322.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schumann K, Lin S, Boyer E, Simeonov DR, Subramaniam M, Gate RE, Haliburton GE, Ye CJ, Bluestone JA, Doudna JA, et al. Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:10437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512503112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seki A, Rutz S. Optimized RNP transfection for highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in primary T cells. J Exp Med. 2018;215:985–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mandal PK, Ferreira LM, Collins R, Meissner TB, Boutwell CL, Friesen M, Vrbanac V, Garrison BS, Stortchevoi A, Bryder D, et al. Efficient ablation of genes in human hematopoietic stem and effector cells using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:643–52. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–32. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim Y, Kweon J, Kim HS, Bae S, Kim J-S. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014;24:132–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.162339.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee HJ, Kim E, Kim JS. Targeted chromosomal deletions in human cells using zinc finger nucleases. Genome Res. 2010;20:81–89. doi: 10.1101/gr.099747.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee HJ, Kweon J, Kim E, Kim S, Kim JS. Targeted chromosomal duplications and inversions in the human genome using zinc finger nucleases. Genome Res. 2012;22:539–48. doi: 10.1101/gr.129635.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:765–71. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shin HY, Wang C, Lee HK, Yoo KH, Zeng X, Kuhns T, Yang CM, Mohr T, Liu C, Hennighausen L. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting events cause complex deletions and insertions at 17 sites in the mouse genome. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15464. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kleinstiver BP, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Topkar VV, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Gonzales APW, Li Z, Peterson RT, Yeh J-RJ, et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2015;523:481–85. doi: 10.1038/nature14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2579–E2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Joung JK. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529:490–95. doi: 10.1038/nature16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:279–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mollanoori H, Shahraki H, Rahmati Y, Teimourian S. CRISPR/Cas9 and CAR-T cell, collaboration of two revolutionary technologies in cancer immunotherapy, an instruction for successful cancer treatment. Hum Immunol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kimberland ML, Hou W, Alfonso-Pecchio A, Wilson S, Rao Y, Zhang S, Lu Q. Strategies for controlling CRISPR/Cas9 off-target effects and biological variations in mammalian genome editing experiments. J Biotechnol. 2018;284:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]