Abstract

Compared with the general population, rates of pheochromocytoma are higher in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients. However, pheochromocytoma testing is often plagued by false positive results. Here we present a patient with NF1, elevated urinary metanephrine levels, and an indeterminate adrenal nodule. Clonidine suppression testing aided diagnosis and led to definitive surgical treatment that confirmed a pheochromocytoma. Pheochromocytoma screening and clonidine suppression testing can both aid in the evaluation for catecholamine-secreting tumours.

Keywords: adrenal disorders, neuro genetics

Background

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disorder with an increased risk of pheochromocytoma, which is an adrenal gland tumour that releases catecholamines. Diagnosis of this tumour may be challenging due to its variable presentation and testing limitations. Biochemical false positives frequently occur secondary to certain medications, metabolic abnormalities and systemic illness. Most pheochromocytomas are sporadic but 10%–15% are hereditary in diseases such as NF1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, von Hippel-Lindau disease and familial carotid body tumours.1–6

The incidence of pheochromocytoma in normotensive patients with NF1 is 1%–5.7%.6 In hypertensive NF1 patients, the rate increases to 20%–50%.7 8 Though our NF1 patient was initially normotensive, the higher incidence of pheochromocytoma in this population led to further testing for pheochromocytoma. To assess for false positive testing, the clonidine suppression test was performed. The ultimate result of testing led to appropriate adrenalectomy.

Case presentation

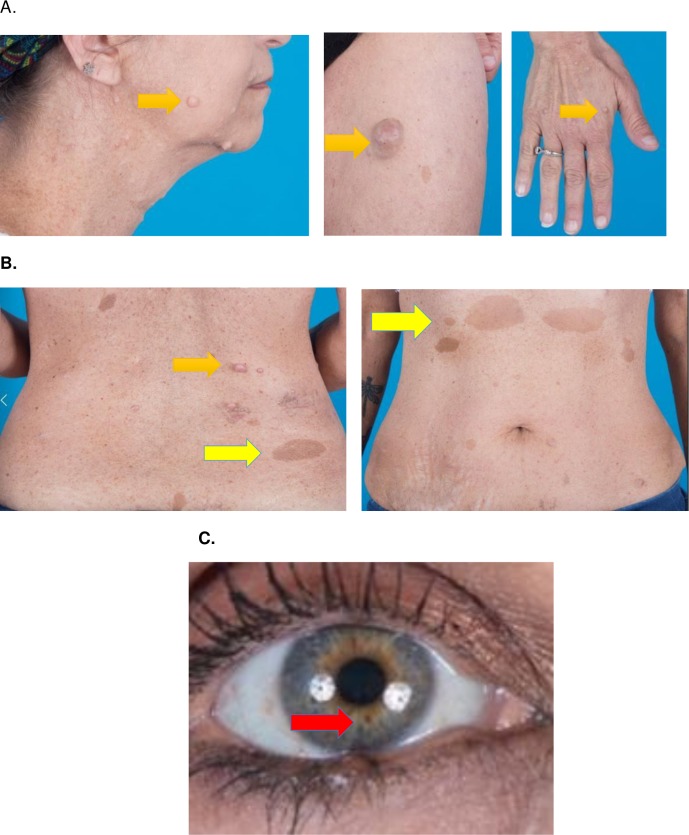

A 48-year-old woman without a personal history of hypertension or NF1 presented in 2015 with panic attacks and occasional tachycardia for several years. Her family history was significant for NF1 in her father and two sons. On physical examination, she had multiple neurofibromas, café au-lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling and iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) (figure 1). Given her family history and physical examination findings, she met the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference criteria for NF1. Upon review of her previous imaging, a non-contrast chest CT from February 2012 noted an incidental right adrenal mass, measuring 1.24 cm (figure 2A). Her urinary metanephrine levels, by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), were above the upper limit of normal in May 2015 (table 1).

Figure 1.

Physical examination findings of our patient, a 48-year-old woman with several years of episodic anxiety and tachycardia and family history positive for NF1. (A) Neurofibromas (purple arrow) on the face, neck, trunk and extremities. (B) Café au lait macules (yellow arrow) on trunk. (C) Lisch nodules (red arrow) within the iris. NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1.

Figure 2.

(A) In February 2012, a non-contrast chest CT incidentally noted a 1.24 cm right adrenal mass (red arrow). (B) In March 2017, an adrenal CT demonstrated a 2.4×2.4×2.6 cm right adrenal mass (blue arrow). The mass has an unenhanced Hounsfield unit attenuation of 44 units, with an absolute washout of 29.5%.

Table 1.

Urine metanephrines over time

| Metanephrine (74–297 mcg/24 hours) |

Normetanephrine (105–354 mcg/24 hours) |

Total metanephrine (179–651 mcg/24 hours) |

|

| May 2015 On cyclobenzaprine |

414 | 449 | 863 |

| February 2017 On cyclobenzaprine |

507 | 753 | 1260 |

| August 2017 Off cyclobenzaprine |

610 | 821 | 1431 |

She had persistent palpitations and anxiety, as well as increasing urinary metanephrine levels in February 2017 (table 1). She had a dedicated adrenal CT in March 2017 that revealed growth of the right adrenal mass, now measuring 2.6 cm (figure 2B). The mass had an unenhanced Hounsfield unit attenuation of 44 units, with an absolute washout of 29.5% (<60% is indeterminate). It was unclear at this time if her medications were contributing to her positive metanephrine testing. Common culprit medications include acetaminophen, labetalol and centrally acting norepinephrine potentiators such as cyclobenzaprine, which the patient was taking. She discontinued cyclobenzaprine, but her urinary metanephrines remained elevated upon repeat testing in August 2017. Additionally, she had increasing episodes of panic attacks, pallor, tachycardia and hypertension. She then had a clonidine suppression test to assess for false positive testing—her plasma normetanephrines levels, by HPLC and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, did not suppress (table 2).

Table 2.

Clonidine suppression test

| September 2017 | Plasma-free normetanephrine (0–145 pg/mL) |

| Baseline | 578 |

| 1 hour post-clonidine | 695 |

| 2 hours post-clonidine | 606 |

| 3 hours post-clonidine | 674 |

Differential diagnosis

Pheochromocytoma.

Medication effect.

Normal variant.

Panic disorder.

Pseudopheochromocytoma.

Treatment

The patient was able to tolerate low dose doxazosin prior to successful right adrenalectomy.

Outcome and follow-up

A 2.3×1.9×1.2 cm haemorrhagic, partially cystic mass, measuring 12.8 g, was excised. Pathology revealed a pheochromocytoma with negative margins. A month after her procedure, she reported resolution of her symptoms. Plasma-free normetanephrine became normal at 59 pg/mL (0–145 pg/mL) and metanephrines became normal at<10 pg/mL (0–62 pg/mL); this was significantly lower than her preoperative plasma-free normetanephrine level of 578 pg/mL and metanephrine level of 251 pg/mL. Genetic testing revealed a heterozygous c.2325+1G>A splice site variant in the NF1 gene, which is pathogenic for NF1.

Discussion

The incidence of pheochromocytoma is 20%–50% in NF1 patients with hypertension, and missing its diagnosis can be fatal.7 In a study of 17 NF1 patients with pheochromocytoma, 6 of them experienced a cardiovascular crisis with elective surgery or childbirth.9 Initial screening for pheochromocytoma starts with plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines.10 However, metanephrine levels may appear normal if tumours are small.11 Interestingly, one study screened 156 asymptomatic NF1 patients for pheochromocytomas with urinary fractionated metanephrines and abdominal imaging; there were 12 pheochromocytomas diagnosed and their urinary metanephrines ranged from 0.4 to 7.6 times the upper limit of normal.12 Therefore, though our patient presented in 2015 with metanephrine values only 1.3 times the upper limit of normal, we could not rule out a pheochromocytoma as she had concerning symptoms (panic attacks, tachycardia) and an indeterminate 1.24 cm adrenal nodule.

Of note, patients with pseudopheochromocytoma, or catecholamine excess without evidence of pheochromocytoma, can also present with paroxysmal hypertension and tachycardia. The phenomenon appears to be secondary to increased cardiovascular sensitivity to catecholamines, and is distinct from panic disorder. Emotional distress is central to panic disorder but fear related to pseudopheochromocytoma arises from its physical manifestations, such as chest pain, palpitations and headache.13

There can be a considerable overlap of urine catecholamine levels between patients with and without a pheochromocytoma. The majority of patients without a pheochromocytoma have the following 24 hours urine levels: metanephrines <400 mcg, normetanephrines <900 mcg, total metanephrines <1000 mcg, norepinephrines <170 mcg, epinephrine levels <35 mcg and dopamine levels <700 mcg.14 15 However, false positive results remain a common and potentially expensive problem. One out of five tests for plasma-free or urine fractionated metanephrines is above the upper limit of normal but most of those tests do not ultimately prove to be pheochromocytoma; factors that contribute to this include low disease prevalence, essential hypertension, obtaining samples while in a seated position, stress associated with extreme illness, lab error and medications such as acetaminophen, labetalol, tricyclic antidepressants and cocaine.10 16 In our patient, there was concern initially that cyclobenzaprine, a centrally acting norepinephrine potentiator, had contributed to her elevated urinary fractionated metanephrines. However, her urinary metanephrines continued to increase despite stopping cyclobenzaprine.

Clonidine suppression testing can help distinguish true from false positives. The test has a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 100%.17 Clonidine is a centrally acting alpha-2 agonist, which suppresses neuronal norepinephrine release. The chromaffin cells of pheochromocytomas are not subject to this downregulation and thus continue inappropriate catecholamine secretion. Testing begins with discontinuing sympatholytic drugs at least 48 hours before testing. Plasma catecholamines and normetanephrines are measured before and 3 hours after clonidine administration (0.3 mg/70 kg body weight). Side effects of clonidine (bradycardia, hypotension) are monitored periodically while patients remain supine.11 This patient’s plasma normetanephrine and metanephrine levels increased after 3 hours, which helped rule out a false-positive result.

Clonidine suppression testing is most accurate with plasma normetanephrine testing. In a study that performed clonidine suppression testing on 48 patients with pheochromocytoma and 49 control patients, clonidine did not suppress plasma normetanephrines in 46 of 48 patients with pheochromocytoma. In contrast, clonidine suppressed normetanephrine levels in all of the controls.13 Pheochromocytoma is more likely if plasma normetanephrine remain above the upper limit of normal and do not suppress by more than 40% from baseline after clonidine suppression testing.17

Limitations of the clonidine suppression test include reduced reliability for plasma epinephrine, norepinephrine, and metanephrine levels. In particular, patients with rare dopamine-secreting tumours, which are often malignant, would not be diagnosed via this test.16 Low baseline catecholamine levels can also diminish its accuracy. Medications such as diuretics, beta-blockers, and tricyclic antidepressants interfere with clonidine suppression results.11 Other options for testing include 123-I metaiodobenzylguanidine scanning, though up to half of normal adrenal glands have increased symmetric or asymmetric physiologic uptake.18 Combination measurements of chromogranin and urinary fractionated metanephrines are also used. In patients with metanephrine levels barely above the normal reference range and with low baseline probability, a wait-and-retest approach is also reasonable.10

Learning points.

There is a much higher rate of pheochromocytoma in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) compared with the general population, especially in NF1 patients with concomitant hypertension.

NF1 patients with pheochromocytoma have an increased risk of cardiovascular crisis.

False positive testing for pheochromocytoma can occur due to low disease prevalence, hypertension, obtaining samples in a seated position, stress, lab error, and medications.

Clonidine suppression helps assess false positive testing for pheochromocytoma.

Footnotes

Contributors: BN wrote the initial draft manuscript, JK provided guidance regarding content, WW revised the manuscript and rewrote multiple drafts for final publication, and SG was the attending supervisor who oversaw the process in entirety.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Zafar W, Chaucer B, Davalos F, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 with a pheochromocytoma: A rare presentation of von recklinghausen disease. J Endocrinol Metab 2015;5:309–11. 10.14740/jem308w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petrovska J, Gerasimovska Kitanovska B, Bogdanovska S, et al. Pheochromocytoma and Neurofibromatosis Type 1 in a Patient with Hypertension. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2015;3:713–6. 10.3889/oamjms.2015.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan D, Liang P, Xiao H. Neurofibromatosis type 1 associated with pheochromocytoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 2016;12:637–43. 10.3892/ol.2016.4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behera KK, Nanaiah A, Gupta A, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1, pheochromocytoma with primary hyperparathyroidism: A rare association. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2013;17:349–51. 10.4103/2230-8210.109670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hari Kumar KVS, Sandhu AS, Shaikh A, et al. Neurofibromatosis 1 with pheochromocytoma. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2011;15:406–8. 10.4103/2230-8210.86988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zografos GN, Vasiliadis GK, Zagouri F, et al. Pheochromocytoma associated with neurofibromatosis type 1: concepts and current trends. World J Surg Oncol 2010;8:14 10.1186/1477-7819-8-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rocchietti March M. Type 1 neurofibromatosis and pheochromocytoma: Focus on hypertension. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2012;3:107–8. 10.4103/0976-3147.91987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tate JM, Gyorffy JB, Colburn JA. The importance of pheochromocytoma case detection in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: A case report and review of literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2017;5:2050313X1774101–4. 10.1177/2050313X17741016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petr EJ, Else T. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma in Neurofibromatosis type 1: frequent surgeries and cardiovascular crises indicate the need for screening. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;4:15 10.1186/s40842-018-0065-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:1915–42. 10.1210/jc.2014-1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: how to distinguish true- from false-positive test results. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2656–66. 10.1210/jc.2002-030005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Képénékian L, Mognetti T, Lifante JC, et al. Interest of systematic screening of pheochromocytoma in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Eur J Endocrinol 2016;175:335–44. 10.1530/EJE-16-0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garcha AS, Cohen DL. Catecholamine excess: pseudopheochromocytoma and beyond. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2015;22:218–23. 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perry CG, Sawka AM, Singh R, et al. The diagnostic efficacy of urinary fractionated metanephrines measured by tandem mass spectrometry in detection of pheochromocytoma. Clin Endocrinol 2007;66:703–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kudva YC, Sawka AM, Young WF. Clinical review 164: The laboratory diagnosis of adrenal pheochromocytoma: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:4533–9. 10.1210/jc.2003-030720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McHenry CM, Hunter SJ, McCormick MT, et al. Evaluation of the clonidine suppression test in the diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma. J Hum Hypertens 2011;25:451–6. 10.1038/jhh.2010.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ergin A, Kennedy A, Gupta M, et al. The cleveland clinic manual of dynamic endocrine testing. Springer International Publishing 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mozley PD, Kim CK, Mohsin J, et al. The efficacy of iodine-123-MIBG as a screening test for pheochromocytoma. J Nucl Med 1994;35:1138–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]