ABSTRACT

Background: Hypoxia may affect the therapeutic efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), which is widely used in nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Liposomal curcumin can exert anticancer effect. Our purpose is to explore the antitumor effect of liposomal curcumin on the HCC after TAE.

Methods: The HepG2 cells were cultured under hypoxic condition (1% O2) and then treated with curcumin liposome. Cell viability, apoptosis and cell cycle were respectively measured by CCK-8 and a flow cytometry. The VX2 rabbits were randomly distributed into three groups: control group with saline embolization, TAE group with lipiodol embolization and curcumin liposome group with curcumin liposome and lipiodol embolization. MRI and CT perfusion scanning were performed after embolization. The hepatocyte apoptosis was measured by the terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferse-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL). The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and microvessel density (MVD) were measured by immunohistochemical. RT-PCR and Western blot were performed to examine mRNA and protein levels.

Results: By regulating the apoptosis-related molecules, curcumin liposome obviously inhibited the cell viability and promoted the apoptosis in G1 phase. Curcumin liposome reduced the tumor size and alleviated neoplasia in VX2 rabbits. Curcumin liposome decreased the expressions of MVD and VEGF and increased the apoptosis of liver tissues. The levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and survivin were suppressed by curcumin liposome both in hypoxic cells and liver tissues in the VX2 rabbits.

Conclusion: Curcumin liposome exerted antitumor effect by regulating the proliferation- and apoptosis-related molecules. Curcumin liposome suppressed the HIF-1α and survivin levels and inhibited the angiogenesis in VX2 rabbits after TAE.

Keywords: curcumin liposome, hypoxia, TAE, liver tumor, HIF-1α, angiogenesis, antitumor

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is proved to have clinical, molecular and biologically heterogeneous properties, and is highly resistant to therapy.1,2 HCC is the third leading cause of cancer death in the world.3 Only 30–40 % of patients with HCC could benefit from curative therapies.4 Recently, a research showed that the survival time of nonsurgical patients can be prolonged by transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE). However, these patients after treatment may bear a risk of relapse and metastasis.5 Besides, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) have been applied to assess the efficiency of TAE therapies.6

The hepatic tumor embolization can only inhibit the tumor growth in early stage7 and angiogenesis induced by hypoxia after TAE may limit the therapeutic efficacy.8 Solid tumor tissue cannot provide adequate oxygen to meet cellular demand due to the aberrant and disordered vasculature.9 Transarterial embolization is demonstrated to elevate the tumor hypoxia by decreasing tumor perfusion. Hypoxia could lead to apoptosis or a resistance to chemotherapy and radiation therapies.10 Additionally, researchers reported that arterial supply to tumor can be prevented by TAE, therefore leading to HCC neoplastic tissues necrosis.11 Nevertheless, proliferation and metastasis of residual cancerous cells can be promoted by hypoxia induced in this progress by enhancing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).11 Besides, the VEGF can be activated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which binds to hypoxia-response elements.12 Moreover, HIF-1α is demonstrated to be evidently elevated in the TAE-treated tumors and the HIF-1α expression was positively relevant to both VEGF level and microvessel density (MVD) in the remaining tumor.13,14

Curcumin, a highly polyphenic molecule, is reported to suppress the viability of cancer cells and is commonly used in prevention or therapy of multiple diseases.15 The anticancer role of curcumin in tumor treatment is reported to be associated with its both induction of apoptosis in cancer cells16 and regulation of various molecular pathways.17 Moreover, curcumin could inhibit HIF-1α expression and suppress angiogenesis in HCC cells in hypoxic environment.18 Although curcumin has anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties, the application of curcumin in clinical practice is restricted by its low bioavailability.19 Fortunately, several nanoparticles including liposomes is shown to enhance the bioavailability of curcumin, preventing its degradation and promoting its delivery to tumors.20 Therefore, the purpose of our study was to investigate the anticancer effect of curcumin liposome on the HCC after TAE.

Materials and methods

Preparation of curcumin liposome

The preparation process was performed as previously described.21 Briefly, the curcumin (Sinopharm Chemical, Beijing, China), cholesterol (Nippon Fine Chemical, Chuo-Ku, Japan) and soybean phosphatidylcholine (Nippon Fine Chemical) (2:1:20, w/w/w) were dissolved in dichloromethane (Sinopharm Chemical) and mixed homogeneously. The solvent was then removed by reducing pressure distillation and vacuum drying overnight. The PBS (pH 6.5) was subsequently added for adequate emulsification at 45°C. The emulsion was extruded progressively by pressing and heat to obtain the emulsion-like liposomal (2 mg/mL) with uniformed size through center control of particle size. Finally, liposomal curcumin (8 mL/vial) was degermed by sterilized filters and stored at 2–8°C. The particle size and zeta potential of curcumin liposomes were detected using a nano-series Malvern Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments Nano-ZS, Worcester shire, UK). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained by a transmission electron microscope (JEOL-USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA). The concentration of curcumin in the liposome was measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The encapsulation efficiency of the liposomes was calculated as (W dialysis/W total) × 100%, in which W dialysis represented the curcumin in the liposome suspensions after dialysis in PBS, while W total referred to the curcumin in the initial liposome suspensions.

Cell culture and treatment

The HepG2 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in an incubator at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. The cells were then treated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2, 1 % O2 and 94 % N2 for 15 h in an in vivo hypoxia workstation 500 with Ruskin hypoxic gas mixer (Biotrace International, Bothell, WA, USA). The cells were divided into four groups: control group (HepG2 cells), hypoxia group (HepG2 cells with hypoxia treatment), cur/hypoxia group (hypoxic HepG2 cells treated with 20 μmol/L curcumin for 12, 24 and 48 h) and curcumin liposome group (hypoxic HepG2 cells treated with curcumin liposome for 12, 24 and 48 h).

Cell viability assay

Cells (1 × 104) in each group were cultivated in 96-well plate and respectively maintained for 12, 24 and 48 h. At each time point, CCK-8 was added into the cells and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm by an Emax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA). Finally, the cells were treated with curcumin or curcumin liposome for 24 h for the following experiments.

Analysis of apoptosis, cell cycle and cell proliferation

Apoptosis and cell cycle were measured by the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/PI apoptosis detection kit (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) and cell cycle analysis kit (BD Biosciences, SanJose, CA, USA) following the protocols, respectively. Cell proliferation was detected using CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit (Thermofisher, USA). The results were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

VX2 rabbit model and grouping

New Zealand rabbits (3.1–3.6 kg) were purchased from Shanghai Tissue Engineering Life Science Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and tumour-bearing rabbits were obtained from First Affiliated Hospital of Zhongshan University. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jiangsu Cancer Hospital, Jiangsu Institute of Cancer Research, Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Cancer Hospital. The VX2 rabbit hepatic carcinoma model was established as previously described.22 Briefly, tumors from carrier rabbits were minced into pieces of 1–2 mm3 in physiological saline. The trial rabbits were anesthetized by injection with pentobarbital (1 ml/kg; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and then a sub-xiphoid incision was made to expose left lobe of the liver, where the fresh tumor tissues were finally implanted. These rabbits were then injected with enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg) to prevent infection.

The VX2 rabbits were randomized into three groups. The NS (negative saline) group (n = 15) was embolized with physiological saline, the lipiodol group (n = 15) was embolized with lipiodol (0.1 ml/kg body weight, Laboratoire Guerbet, Roissy, France) and the curcumin liposome group (n = 15) was embolized with liposomal curcumin (20 mg/kg body weight) mixed with lipiodol. After 28 days, all VX2 rabbits were inspected by a MR VivoLVA compact MRI system (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) with 1.5 T permanent magnets. The VX2 rabbits were then sacrificed and the tissues were collected.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The liver tumor tissues of rabbits were fixed in formaldehyde and then blocked in paraffin. Thereafter, sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min followed by staining with eosin for 3 min (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). Images of sections were observed under an inverted microscope (Leica, Germany). IHC was performed as previously described.23 Briefly, the sections were blocked in 3 % H2O2 for 10 min and then incubated with goat serum for 15 min. Subsequently, the sections were first washed and incubated with anti-VEGF (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and anti-CD31 (1:20; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with second antibody (Zhongshan Golden Bridge, Beijing, China) at 37°C for 1 h. Next, the sections were stained with 3, 3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Zhongshan Golden Bridge) for 6 min and rinsed and stained in hematoxylin for 30 s. The sections were then dehydrated in gradient alcohol and sealed in neutral resins. The integral optical density (IOD) was calculated with Image Pro plus 6.0 software (Microsoft Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). Brown staining endothelial cell cluster that clearly separate from adjacent microvessels as well as tumor cells were considered as a countable microvessel.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transfer-mediated dutp nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The sections were incubated at 60 °C for 20 min and were deparaffinized in xylene twice. Then the sections were washed in graded series of alcohol and rinsed with PBS. Apoptotic cells were detected following the protocol of TUNEL kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells were quantified under × 400 magnification.

RNA extraction, cdna synthesis and real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA of cells and tissues was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, samples were homogenized in Trizol reagent followed by using chloroform. Next, the samples were mixed for 5 min. After centrifugation (12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C), the supernatant was carefully drew into a new tube. An equal volume of isopropyl alcohol was added and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Following the centrifugation (12,000 g at 4°C for 10 min), the supernatants were removed completely and the precipitate was washed twice by 75% ethanol. Finally, nuclease-free DEPC water was added to elute the RNA. The concentration and purity were detected by NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Willmington, DE, USA). The cDNA was obtained by 1 µg RNA, according to the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). In brief, the RNA was incubated with 2X RT master mix containing 10 × RT Buffer, 25 × dNTP Mix, 10 × RT Random Primers and MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase at 25 °C for 10 min, then at 37 °C for 2 h and at 85°C for 5 min. The expressions were determined in ABI 7500 real-time quantitative PCR system (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) under following conditions: at 94 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, at 53°C for 45 s and at 72°C for 3 min. The specific primers used were listed in Table 1. Next, the PCR products were separated on a 1 % agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Densitometry was analyzed with the 200TM-Image software (Bio-Rad, USA) and GAPDH served as an internal reference gene.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for quantitative real-time PCR assays.

| Genename | Forward (5ʹ-3ʹ) | Reverse (5ʹ-3ʹ) |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | CTTCTGGATGCTGGTGATTTG | TATACGTGAATGTGGCCTGTG |

| survivin | CGAGGCTGGCTTCATCCA | CAACCGGACGAATGCTTTTT |

| VEGF | AGGAGGGCAGAATCATCACG | TATGTGCTGGCCTTGGTGAG |

| Bcl-2 | CAAATGCTGGACTGAAAAATTGTA | TATTTTCTAAGGACGGCATGATCT |

| Bax | GACACCTGAGCTGACCTTGG | GAGGAAGTCCAGTGTCCAGC |

| Caspase-3 | GCTACGAGTGGGATACTGGAGA | AGTCATCCACAGAGCGATGTT |

| p21 | GCGGCAGACCAGCATGA | ATTAGGGCTTCCTCTTGGAGAAG |

| cyclin D1 | AGCTCCTGTGCTGCGAAGTGGAAAC | AGTGTTCAATGAAATCGTGCGGGGT |

| GAPDH | TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGGC | CATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC |

| Rabbit HIF-1α | TCCATTACCTGCCTCTGAAACTCC | TTGAATCTGGGGGCATGGTAAAAG |

| Rabbit survivin | GACCACCGCATCTCTACATTCAAGA | TGAAGCAGAAGAAACACTGGGC |

| Rabbit GAPDH | TTAGCACCCCTGGCCAAGG | CTTACTCCTTGGAGGCCATG |

Western blot

Renal tissues were washed by PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The lysates were then incubated on ice for 30 min and oscillated for 30 s. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected to measure the protein concentrations by BCA kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The proteins separated by the SDS-PAGE were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). After being blocked for 1 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies as follows: Bcl-2 (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Bax (1:500, Abcam), caspase-3 (1:500, Abcam), HIF-1α (1:1000, Abcam), VEGF (1:1000, Abcam), survivin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), p21 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin D1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) and GADPH (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology). Thereafter, the membranes were probed with secondary antibodies (1:1000, Beyotime). The bands were determined by a Molecular Imager VersaDoc MP 5000 System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The densitometry was determined with a Quantity One (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The statistical significance was set as (P < 0.05). The differences was analyzed by Student’s t test (for two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following Turkey’s multiple comparison (for multiple groups).

Result

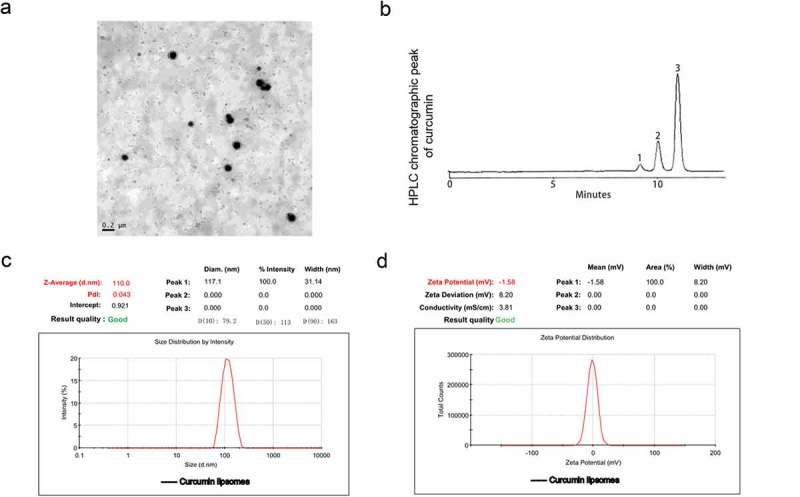

Characterization of curcumin liposome

The characterization of curcumin liposome was identified by liposomal morphology, EE, particle size and zeta potential. The morphology of the curcumin liposomes exhibited a spherical shape in standard electronic modules (Figure 1A). The curcumin liposome was eluted at 11.49 min, while the bis-demethoxycurcumin and demethoxycurcumin was eluted at 9.02 and 10.19 min, respectively (Figure 1B). The mean particle size of the curcumin liposome was 117.1 nm (Figure 1C) and the zeta potential on the surface of the curcumin liposome was −1.58 mV (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

The physicochemical parameters of curcumin liposome. (A) The morphology of curcumin liposome detected by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). (B) HPLC chromatographic peak of curcumin. 1: bisdemethyoxy cuecumin; 2: demethoxy cuecumin; 3: cuecumin. (C) Particle size distribution of liposomal curcumin. (D) Zeta potential of liposomal curcumin.

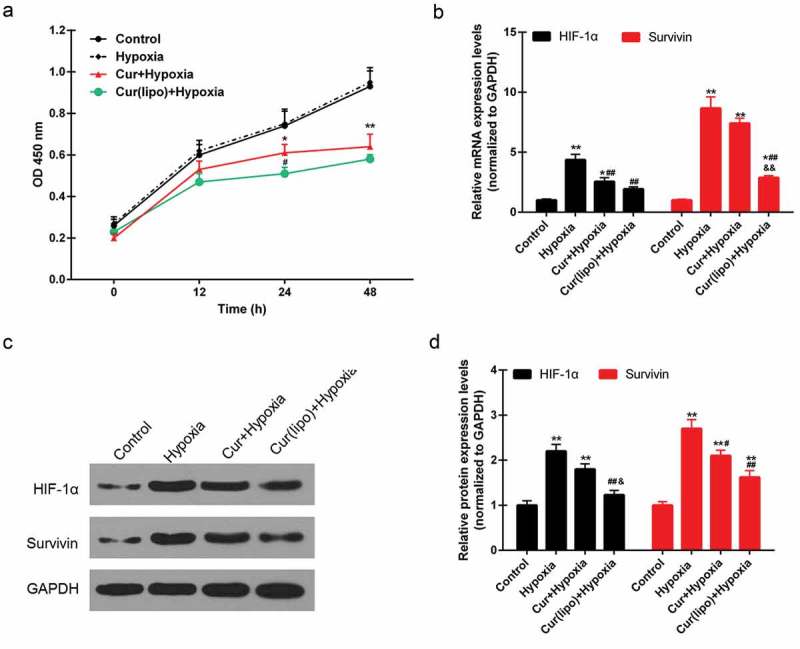

Curcumin liposome inhibited the expression of HIF-1α and survivin in hypoxic cells

We first investigated the effect of curcumin liposome on the cell viability. We found that the cell viability was obviously suppressed after the curcumin or curcumin liposome treatment, and that the inhibition effect of curcumin liposome was stronger than that of curcumin at 24 h (P < 0.05; Figure 2A). Thus, the cells were treated with curcumin or curcumin liposome for 24 h for the following experiments. Moreover, the mRNA levels of HIF-1α and survivin were enhanced by hypoxia; by contrast, the HIF-1α and survivin expressions were significantly inhibited by curcumin liposome (P < 0.01; Figure 2B). Similarly, the protein expressions of HIF-1α and survivin were also decreased by curcumin liposome in hypoxic cells (P < 0.01; Figure 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Curcumin liposome inhibited the expression of HIF-1α and survivin in hypoxic cells. (A) The cell viabilities in each group. (B) Curcumin liposome inhibited the mRNA expression of HIF-1α and survivin. (C) The protein levels of HIF-1α and survivin by Western blot. (D) Curcumin liposome inhibited the protein levels of HIF-1α and survivin. *P < 0.05,**P < 0.01 versus control group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus hypoxia group, &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 versus cur+ hypoxia group.

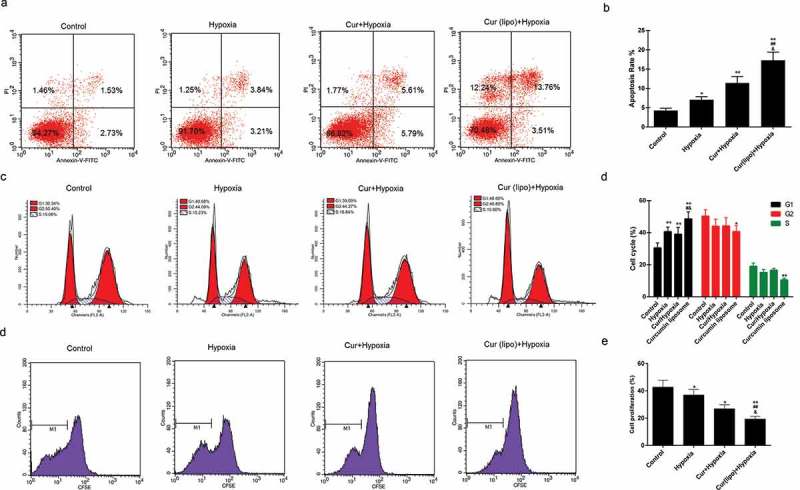

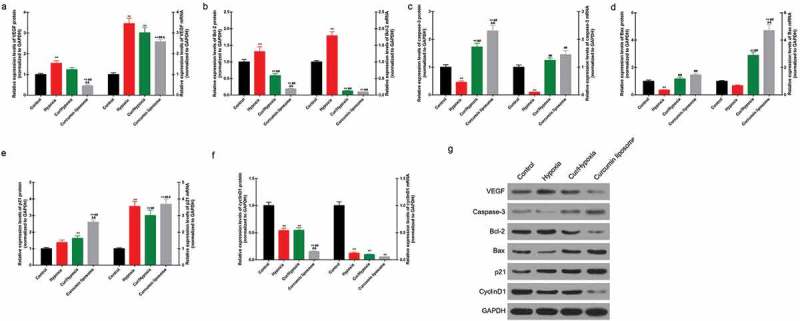

Effect of curcumin liposome on the apoptosi, cell cycle and cell proliferation of hypoxic hepG2 cells

Apoptosis was found to be induced by hypoxia, while curcumin markedly promoted the apoptosis of hypoxic cells. Moreover, curcumin liposome increased apoptosis compared to curcumin (Figure 3A–B). Furthermore, curcumin liposome promoted the G1 phase cell cycle arrest compared to curcumin. While the cells inS and G2 phase was reduced by curcumin liposome (Figure 3C–D). To further explore the antitumor property of curcumin liposome, the mRNA and protein expressions of proliferation- and apoptosis-associated molecules were detected. We found that the expression levels of VEGF (Figure 4A and 4G) and Bcl-2 (Figure 4B and 4G) were suppressed, while the expressions of caspase-3 (Figure 4C and 4G) and Bax (Figure 4D and 4G) were increased in hypoxic cells treated with curcumin liposome. Additionally, the mRNA and protein expressions of p21 and cyclin D1 were also determined (Figure 4E–G). The p21 expression was found to be enhanced by curcumin liposome in the hypoxic cells (Figure 4E and 4G). By contrast, the cyclin D1 level was inhibited by curcumin liposome (Figure 4F and 4G).

Figure 3.

Effect of cuecumin liposome on the apoptosis and cell cycle in HepG2 cells. (A) The apoptosis rate of HepG2 cells in the four groups. (B) The histogram showed the apoptosis percentage of HepG2 cells. (C) Cell cycle analysis by a flow cytometry. (D) The increased cells accumulated in G1 phase. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus hypoxia group, &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 versus cur+ hypoxia group.

Figure 4.

Effect of curcumin liposome on the expression of proliferation- and apoptosis-related molecules. (A-D) The mRNA and protein levels of VEGF, Bcl-2, caspase-3 and Bax. (E-F) The mRNA and protein levels of p21 and cyclin D1. (G) The protein expressions of VEGF, Bcl-2, caspase-3, Bax, p21 and cyclin D1 was detected by Western blot. **P < 0.01 versus control group, ##P < 0.01 versus hypoxia group, &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 versus cur+ hypoxia group.

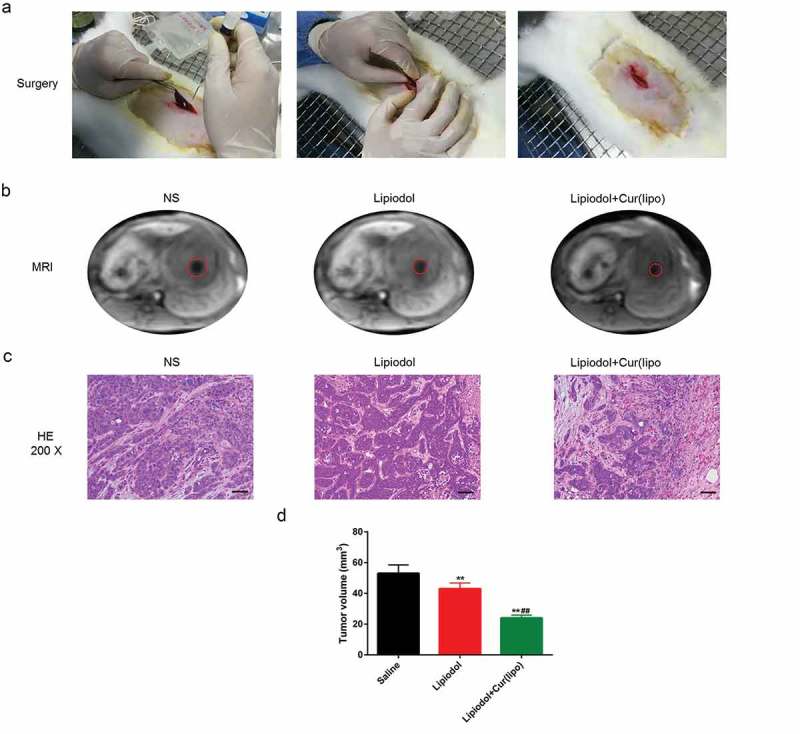

Curcumin liposome suppressed the tumor growth

The VX2 rabbit hepatoma model was successfully established (Figure 5A).The results from MRI showed that the tumor size was reduced by the curcumin liposome (Figure 5B). Moreover, coagulative necrosis was observed in a majority of the tumor lesions and a small amount of residual tumor nests was found around the lesion. Besides, thick fibrous septum was seen around the tumor tissue with seldom inflammatory cells and few blood vessels (Figure 5C). After 28 days, the tumor volume in curcumin liposome group was identified to be the smallest among the three groups (P < 0.01; Figure 5D)

Figure 5.

Curcumin liposome suppressed the tumor growth. (A) Establishment of VX2 rabbit hepatic cancer models. (B) The MRI images of the tumor size. (C) H&E staining of liver tumor tissues in VX2 rabbits. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) The tumor volume was calculated by MRI imaging. **P < 0.01 versus Saline group, ##P < 0.01 versus lipiodol group.

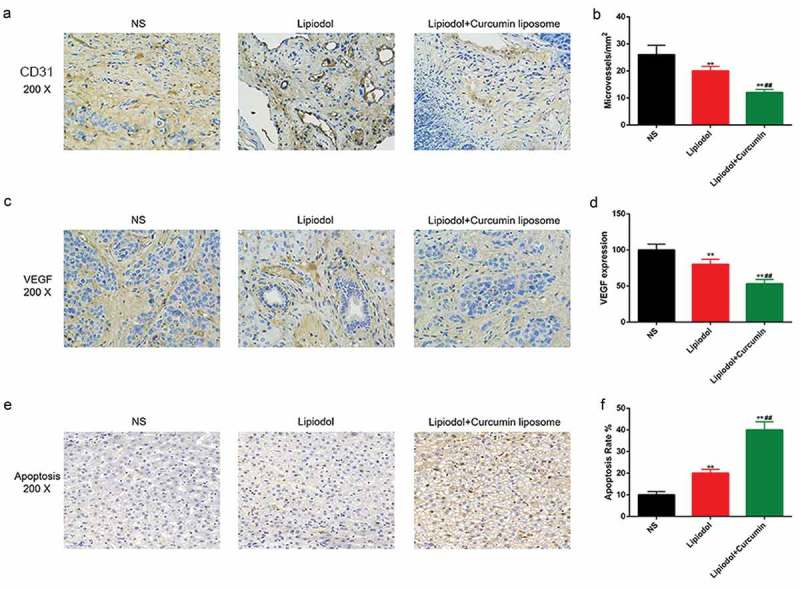

Curcumin liposome alleviated the angiogenesis and promoted the tumor apoptosis

An inhomogeneous distribution of microvessels was observed, and the blood vessel was formed at the margins of tumor in the NS group (Figure 6A). The mean MVD was remarkably reduced by the TAE with curcumin liposome and lipiodol, compared with the TAE with physiological saline or exclusive lipiodol (P < 0.01; Figure 6B). Meanwhile, the VEGF was highly expressed in the necrosis zone of residual tumors (Figure 6C). The VEGF expression was obviously inhibited in the curcumin liposome group tumors compared with the control and lipiodol group (P < 0.01; Figure 6D). Moreover, apoptotic cells were increased in both the lipiodol group and curcumin liposome group. The apoptosis rate was higher in curcumin liposome compared to lipiodol group (P < 0.01; Figure 6E–F).

Figure 6.

Curcumin liposome alleviated the angiogenesis and promoted the tumor apoptosis. (A) IHC staining of the CD31. Scale bar, 20 μm. Arrows point to microvessels. (B) The MVDs in each group. (C) IHC staining of the VEGF. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Changes in VEGF expression. (E) TUNEL was performed to detect the apoptosis of xenografts tissues. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) The apoptosis percentage of xenografts tissues. **P < 0.01 versus saline group, ##P < 0.01 versus lipiodol group.

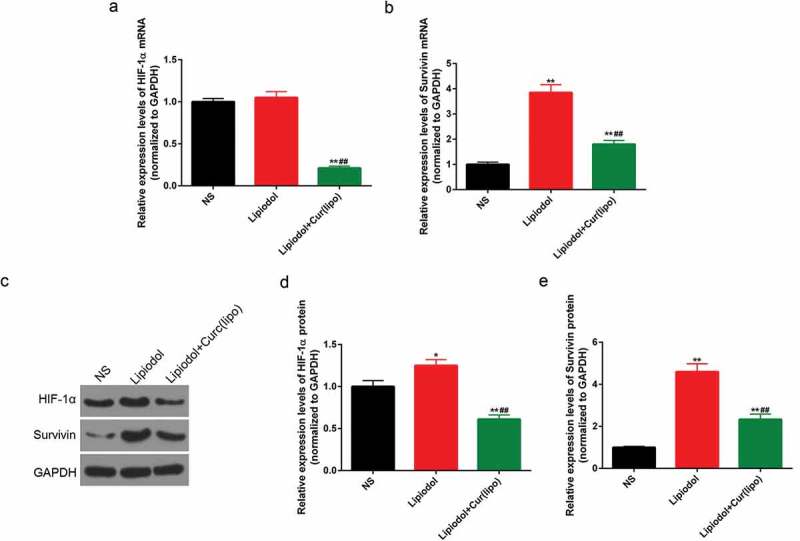

Curcumin liposome reduced the levels of HIF-1α and survivin in vivo

The expressions of HIF-1α and survivin were determined in order to further explore the effect of curcumin liposome on the apoptosis. The mRNA levels of HIF-1α and survivin were found to be significantly suppressed in the curcumin liposome group, compared with those in control and lipiodol group (P < 0.01; Figure 7A–B). Similarly, the protein expressions of HIF-1α and survivin were also largely reduced by the curcumin liposome (P < 0.01; Figure 7C–E).

Figure 7.

Curcumin liposome reduced the levels of HIF-1α and survivin in vivo. (A-B) The mRNA levels of HIF-1α and surviving. (C) The protein levels of HIF-1α and survivin by Western blot. (D-E) The protein levels of HIF-1α and survivin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus saline group, ##P < 0.01 versus lipiodol group.

Discussion

The embolization can prevent blood flow to the tumors, therefore leading to the tumor hypoxia and ischemic necrosis.8 Curcuminoids have been reported to exhibit antitumor, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect and to have antimicrobial properties.24 In addition, curcumin is revealed to be involved in the inhibition of angiogenesis, migration and invasion.25 We found that curcumin liposome could promote the apoptosis and inhibit cell proliferation of hypoxic HCC cells by regulating the proliferation- and apoptosis-related molecules. Moreover, curcumin liposome was also found to exert an anti-angiogenesis and pro-apoptotic effects on the tumors. Furthermore, the inhibition of HIF-1α and surviving expression was also found in curcumin liposome group.

Curcumin liposome is rapidly developed to improve the utilized coefficient of curcumin. Curcumin liposome is reported to possess a more effective anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenesis properties than free curcumin against tumor in human bodies.26 Moreover, the physicochemical parameters, including average particle size, size distribution and zeta potential are adjusted to be appropriate for the liposomal system.27 In our study, the bilayer characteristic of the vesicles was legible in TEM images. Besides, the mean particle size of liposomal curcumin was 117.1 nm and the zeta potential of liposomal curcumin was −1.58 mV, indicating that the curcumin liposome possessed a favorable physical nature. Moreover, the HPLC assay revealed that liposomal excipients produced no effect on the curcumin.

The antitumor effect of curcumin is demonstrated to originated from its capacity to trigger apoptosis in various cancer cells including HCC cells.28 Hypoxic signaling is seen as a central modulator that participates in the physiological processes in tumorous cells.29,30 Besides, researchers found that hypoxia was relevant to a poor prognosis of malignant tumors. Moreover, hypoxia could regulate proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis and the resistance to chemotherapy/radiotherapy of tumor cells.31–33 A recent study showed that curcumin could suppress the accumulation of HIF-1α induced by hypoxia and inhibit the viability, migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of HepG2 cells.34 In our study, the curcumin liposome could inhibit the viability and cell proliferation of hypoxic HepG2 cells. HIF-1α is a crucial transcription factor and is specifically expressed under hypoxia condition.34 The inhibition of HIF-1α can prevent the migration of HepG2 cells.35 Survivin, an inhibitor of apoptotic protein, is found to be expressed in the various tumors, however, it is non-detectable in healthy human tissues.36 In this study, the levels of HIF-1α and survivin were obviously reduced by the curcumin liposome in the hypoxic cells, suggesting that curcumin liposome might exert antitumor effect by inducing the apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation of cancer cells.

The hypoxia can be induced by TAE in HCC, and rudimental cancer cells can grow in such a hypoxic environment. Once stimulated by the hypoxia, HIF-1α can accumulates in the cell and transfer into the nucleus to activate the metastasis-related genes.37 Besides, the protein level of HIF-1α is demonstrated to increase in liver tumor after TAE.38 In our in vivo study, the expressions of HIF-1α and survivin were markedly increased after TAE with lipiodol, however, they were inhibited by the curcumin liposome at the transcriptional and translational levels. HIF-1α can positively regulate the tumor growth and metastasis of tumor in mice model.32 Silencing HIF-1α could not only alleviate increased VEGF and intense MVD induced by hypoxia after TAE, but also improve the curative effect of TAE by preventing angiogenesis.39 Additionally, TAE can lead to HCC necrosis, and it may also induce tumor hypoxia, which can enhance HIF-1α and VEGF levels.39 We found that curcumin could inhibit the VEGF expression in addition to HIF-1α in HepG2 cells, and such a result was consistent with a previous study.18 VEGF, a crucial angiogenic factor, can be regulated by HIF-1 to trigger angiogenesis. The poor prognosis is reported to be relevant to increased VEGF expression or MVD.40 We found that a notable decrease in VEGF level in livers of VX2 rabbits after TAE with curcumin liposome, suggesting that curcumin liposome could prevent the angiogenesis of tumor tissues. Furthermore, the MVD was obviously reduced at the invasive edge of tumors after TAE with curcumin liposome, indicating that curcumin liposome may block the angiogenesis in hepatic tumors after embolization.

The apoptosis of tumor endothelial cells is demonstrated to be able to suppress blood supply to tumors, therefore ultimately resulting in tumor cell death.41 Curcumin could inhibit cell proliferation and promote apoptosis of human HCC cells.42 For instance, curcumin could lead to a significant reduce of Bcl-2 expression and an obvious up-regulation of in Bax level in human hepatoma cells.43 Caspase-3 is an effector caspase that can be activated to induce apoptosis. In this study, an evident increase of apoptosis rate of hypoxic cells with curcumin liposome was observed. Curcumin liposome decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased Bax and caspase-3 expressionas. The p21 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that could regulate cell cycle.44–46 p21 can prevent the conversion from G1 phase to S phase in the nucleus.47 Cyclin D1 is reported to be involved in the G1/S transition in normal cell, however, its expression are aberrant in cancers.48 Therefore, cells accumulation in the G1 phase may be explained by the increased p21 and reduced cyclin D1 expression. In this study, the tumor size and tumor volume were evidently decreased after the TAE with curcumin liposome. In addition, data from TUNEL showed that cell apoptosis was increased by curcumin liposome. These results suggested that curcumin liposome could inhibit the tumor growth. HIF-1α and survivin plays an important role in accelerating tumor progression and promoting tumor growth. In this study, the expression of HIF-1α and survivin was found to be induced by hypoxia condition that may facilitate the recurrence of HCC after TAE.49 The expression of HIF-1α and survivin was reduced by curcumin liposome. These findings indicated that curcumin liposome treatment produced anti-tumor effect on HCC after TAE.

In summary, our study indicated that curcumin liposome could suppress the cell viability by regulating the proliferation- and apoptosis-related molecules in HepG2 cells induced by hypoxia. Moreover, curcumin liposome could inhibit the tumor growth, block the angiogenesis and promote the tumor apoptosis in vivo. These results suggest that curcumin liposome may play an anticancer role in treating HCC.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Cancer Hospital Young Tablents Plan; Jiangsu Cancer Hospital College Project [ZM201504].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, Cronin KA, Ma J, Ryerson B, Mariotto A, Lake AJ, Wilson R, Sherman RL, et al. 2017. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst.109:djx030. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wörns MA, Galle PR.. 2014. HCC therapies—lessons learned. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lencioni R, De BT, Soulen MC, Rilling WS, Geschwind JF.. 2016. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology. 64:106–116. doi: 10.1002/hep.28453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. 2011. Current concepts hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bo Z, Wang J, Yan Z. Ginsenoside Rg3 attenuates hepatoma VEGF overexpression after hepatic artery embolization in an orthotopic transplantation hepatocellular carcinoma rat model. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European association for the study of the liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R, et al. 2002. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng D, Zhang X, Shen W, Chen J, Liu L, Gao G. Liposomal curcumin inhibits hypoxia-induced angiogenesis after transcatheter arterial embolization in VX2 rabbit liver tumors. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2601–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davda S, Bezabeh T. 2006. Advances in methods for assessing tumor hypoxia in vivo: implications for treatment planning. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25:469. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaupel P, Mayer A. 2007. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strebel BM, Dufour JF. 2008. Combined approach to hepatocellular carcinoma: a new treatment concept for nonresectable disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 8:1743–1749. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.11.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semenza GL. HIF-1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S62–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virmani S, Rhee TK, Ryu RK, Sato KT, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Kulik LM, Szolc-Kowalska B, Woloschak GE, Yang G-Y, et al. 2008. Comparison of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha expression before and after transcatheter arterial embolization in rabbit VX2 liver tumors. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 19:1483–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang B, Zheng CS, Feng GS, Wu HP, Wang Y, Zhao H, Qian J, Liang H-M. 2010. Correlation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha with angiogenesis in liver tumors after transcatheter arterial embolization in an animal model. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 33:806–812. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devassy JG, Nwachukwu ID, Jones PJ. 2015. Curcumin and cancer: barriers to obtaining a health claim. Nutr Rev. 73:155–165. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuu064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shehzad A, Lee J, Huh TL, Lee YS. 2013. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human colorectal carcinoma (HCT-15) cells by regulating expression of Prp4 and p53. Mol Cells. 35:526. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranjan AP, Mukerjee A, Helson L, Gupta R, Vishwanatha JK. Efficacy of liposomal curcumin in a human pancreatic tumor xenograft model: inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3603–3609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae MK, Kim SH, Jeong JW, Lee YM, Kim HS, Kim SR, Yun I, Bae SK, Kim KW. 2006. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia-induced angiogenesis via down-regulation of HIF-1. Oncol Rep. 15:1557–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shehzad A, Lee J, Lee YS. 2013. Curcumin in various cancers. Biofactors. 39:56–68. doi: 10.1002/biof.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalili S, Saeedi M. 2016. Study of curcumin behavior in two different lipid bilayer models of liposomal curcumin using molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 34:327. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2015.1030692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S, Li J, Xu H, Zhang S, Chen X, Chen W, Yang S, Zhong S, Zhao J, Tang J. 2017. Liposomal curcumin alters chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells to adriamycin via regulating microRNA expression. Gene. 622:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q, Du J, Yu M, He G, Luo W, Li H, Zhou X. 2009. Transmission electron microscopy of VX2 liver tumors after high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation enhanced with SonoVue. Adv Ther. 26:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Town JR, Li F, Zhang X, Cockcroft DW, Gordon JR. 2009. ELR-CXC chemokine receptor antagonism targets inflammatory responses at multiple levels. J Immunol. 182:3213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasan M, Belhaj N, Benachour H, Barberi-Heyob M, Kahn CJF, Jabbari E, Linder M, Arab-Tehrany E. 2014. Liposome encapsulation of curcumin: physico-chemical characterizations and effects on MCF7 cancer cell proliferation. Int J Pharm. 461:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valapala M, Thamake SI, Vishwanatha JK. 2011. A competitive hexapeptide inhibitor of annexin A2 prevents hypoxia-induced angiogenic events. J Cell Sci. 124:1453. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Ahmed B, Mehta K, Kurzrock R. 2007. Liposomal curcumin with and without oxaliplatin: effects on cell growth, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 6:1276–1282. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvagno MG, Celia C, Paolino D, Cosco D, Iannone M, Castelli F, Doldo P, Frest M. 2007. Effects of lipid composition and preparation conditions on physical-chemical properties, technological parameters and in vitro biological activity of gemcitabine-loaded liposomes. Curr Drug Deliv. 4: 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang WZ, Li L, Liu MY, Jin XB, Mao JW, Pu QH, Meng M-J, Chen X-G, Zhu J-Y. 2013. Curcumin induces FasL-related apoptosis through p38 activation in human hepatocellular carcinoma Huh7 cells. Life Sci. 92:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anastasiadis AG, Bemis DL, Stisser BC, Salomon L, Ghafar MA, Buttyan R. Tumor cell hypoxia and the hypoxia-response signaling system as a target for prostate cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2003;4. doi: 10.2174/1389450033491136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kizakakondoh S, Inoue M, Harada H, Hiraoka M. 2003. Tumor hypoxia: a target for selective cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 94:1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghattass K, Assah R, Elsabban M, Galimuhtasib H. Targeting hypoxia for sensitization of tumors to radio- and chemotherapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13. doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao D, Johnson RS. 2007. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagaraju GP, Bramhachari PV, Raghu G, El-Rayes BF. 2015. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α: its role in colorectal carcinogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 366:11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan W, Chang Y, Li R, Xu Q, Lei J, Yin C, Li T, Wu Y, Ma Q, Li X. 2014. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia inducible factor‑1α‑induced epithelial‑mesenchymal transition in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 10:2505–2510. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno T, Nagao M, Yamada Y, Narikiyo M, Ueno M, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Nakajima Y. 2006. Small interfering RNA expression vector targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha inhibits tumor growth in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers. Cancer Gene Ther. 13:131–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waligã3Rska-Stachura J, Jankowska A, Waśko R, Liebert W, Biczysko M, Czarnywojtek A, Baszko-Błaszyk D, Shimek V, Ruchała M. Survivin–prognostic tumor biomarker in human neoplasms–review. Ginekol Pol. 2012;83:537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dit Ruys SP, Delaive E, Demazy C, Dieu M, Raes M, Michiels C. 2009. Identification of DH IC-2 as a HIF-1 independent protein involved in the adaptive response to hypoxia in tumor cells: A putative role in metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1793:1676–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee TK, Young JY, Larson AC. 2007. Effect of transcatheter arterial embolization on levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in rabbit VX2 liver tumors. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 18:639. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Wang J, Liu R, Qian S. 2012. RNA interference of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha improves the effects of transcatheter arterial embolization in rat liver tumors. Tumour Biol. 33:1095–1103. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pang R, Poon RTP. 2006. Angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 242:151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mondal G, Barui S, Saha S, Chaudhuri A. 2013. Tumor growth inhibition through targeting liposomally bound curcumin to tumor vasculature. J Control Release. 172:832–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.08.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu MX, Zhao L, Deng C, Yang L, Wang Y, Guo T, Li L, Lin J, Zhang L. 2013. Curcumin suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the wnt signaling pathway. Int J Oncol. 43:1951–1959. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J, Zhou X, He X, Dai M, Zhang Q. Curcumin induces apoptosis involving bax/bcl-2 in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1925–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cmielová J, Rezáčová M. 2011. p21Cip1/Waf1 protein and its function based on a subcellular localization [corrected]. J Cell Biochem. 112:3502–3506. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ju Z, Choudhury AR, Rudolph KL. 2007. A dual role of p21 in stem cell aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1100:333. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savio M. 2010. Multiple roles of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(CDKN1A) in the DNA damage response. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 704:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warfel NA, Eldeiry WS. 2013. p21WAF1 and tumourigenesis: 20 years after. Curr Opin Oncol. 25:52–58. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835b639e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elham M, Shaahin H. 2014. Sohlh2 inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation by the upregulation of p21 and downregulation of cyclin D1. Carcinogenesis. 35:1863–1871. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cardin R. 2008. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the role of angiogenesis and invasiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 103:914–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]